The invisible web – from interaction to coalition-building in the EU

Summary

The further development of Europe depends on the building of efficient coalitions – whether legally binding or informally arranged – through which new political initiatives for ‘more Europe’ can be effectively put into practice.

The expert EU28 Survey illustrates the complex network of relationships among EU member states; particularly closely interlinked with other member states are Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, Poland, the Netherlands, and Sweden. This same grouping of eight member states are also ranked high for their ‘influence on EU policy’ and are named most frequently by others as ‘important partners’.

However, the coalition geometry varies depending on the policy field, so that there are several political centres when looking at foreign policy or defence policy, at fiscal policy or economic and social policy.

From these coalition centres, initiatives for building coalitions emerge. Countries in the centre will try to bring in the member states with which they are connected, and build majorities.

Introduction

In early March 2017, three weeks before the celebrations of the 60th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Rome, French President François Hollande invited the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, and the prime ministers of Italy and Spain, Paolo Gentiloni and Mariano Rajoy, to a summit in Versailles. This meeting produced one major message directed at the European Union at large: Europe needs a multi-speed approach if it is to be successful in future. The leaders made a variety of references to “different levels of integration” and said that “some countries will go faster than others.”

These instances demonstrate a renewed desire to bring back to EU policymaking the strength that a political centre can provide. This coalition-building would consist of a coalition of member states willing to shape and drive the EU agenda, to devise political initiatives and bring together the necessary majorities or consensus. Such a centre would also re-establish a strategic understanding among several member states about the importance of deeper cooperation, be it on the level of all member states or in a core group. It would counter the centrifugal tendencies inherent to the large and heterogeneous community of 28 members.

The revival of coalition-building marks the end of a period in which the traditional clusters of EU members had gradually weakened. For example, for years, Italy neglected the close cooperation which used to exist among the Founding Six, the Netherlands seemed less interested in the long-established Benelux partnership, and the Visegrad Group of Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia appeared to have lost its significance after the EU’s eastern enlargement. Even the most essential of the traditional coalitions, the Franco-German tandem, was starting to creak. With the disappearance of these coalitions, the EU lost its political centre, and the EU institutions lacked the enabling support group of governments to back their initiatives. The EU’s policy process was characterised by political fragmentation. And yet, after the Lisbon Treaty, which provided for an upgraded European Council, the significance of the interactions between member states only grew.

Against this background, coalition-building serves three main purposes. Firstly, forming coalitions is a tool of governance in a largely intergovernmental EU. At present, managing the status quo already requires significant member state interaction in advance of or around the formal procedures. With the large number of members, the need for informal consensus-building among governments has grown. With a full-time president of the European Council and the rotating council presidency, the EU now needs groupings and coalitions of governments to shape the agenda, to drive issues forward, and to bridge cleavages between member state interests.

Secondly, coalitions offer the chance to counter the veto power which is now enjoyed by a large number of governments. Consensus, and even the building of qualified majorities, has become more complex because of the increased number of smaller member states. For the same reason, coalitions have become an instrument of majority building, representing clusters of consensus on different issues.

Thirdly, coalitions are a necessary building block of flexibility or differentiation of integration. In coalitions, strategic consensus and an operational strategy will be developed which would then be translated into enhanced cooperation under the treaties or core-building next to the EU’s legal framework. Without their existence and formative impact, greater flexibility would likely result in a ‘Europe à la carte’, in which member states opt out of policies as they please. ‘Differentiation’ and ‘flexibility’ have increasingly become code-words for finding a way forward for an EU whose members appear deeply divided. The classic approach to ‘more Europe’ is no longer an option given the likely rejection of any significant treaty change in the ratification process. Instead, using the treaty clauses of “enhanced cooperation”, first introduced by the Treaty of Amsterdam, or of “permanent structured cooperation”, established for the area of security and defence by the Lisbon Treaty, groups of member states have the option of moving ahead on their own and thus overcome any lack of EU-wide consensus. Another avenue of differentiation could be to follow the example of the Schengen agreement, a treaty concluded between a group of member states outside of the legal framework of the EU.

At this critical juncture of European integration, and more than at any time since the end of cold war, member states’ capacity and willingness to act together will shape the future of Europe. Cooperation among member states, the web of their interactions, the patterns of like-mindedness and of strategic consensus, have become factors key to keeping Europe together. But to continue using coalition-building and coalitions for this purpose requires a deeper understanding of these factors. A simple return to traditional coalitions is not on the cards. New coalitions will need to be developed for the much larger EU of today, built on interests, resources, and transactional power of member states.

About the EU28 Survey

This policy brief draws on the findings of the EU28 Survey 2016, an expert survey conducted by ECFR in the 28 member states of the European Union. The data collected by the survey represents the opinions of 421 professionals who work on European policy in governments, think-tanks and universities, and the media. The results of the EU28 Survey create a visual understanding of the views held by Europe’s professional political class – information that otherwise is not available to policymakers or the public.

The EU28 Survey was conducted as an anonymous online questionnaire. It opened shortly after the British referendum on EU membership in late June 2016 and closed in mid-September 2016. The 2016 series was the second edition of the EU28 Survey. It was first conducted in 2015 and is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe project on European cohesion and the EU’s capacity to act together.

This policy brief is accompanied by the EU Coalition Explorer, an interactive tool that illustrates all survey results, the complete data set, and the methodology behind our analysis. To learn more please visit www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer.

The data and analyses examined here reveal how coalitions currently function. Which are the ‘go to’ countries when it comes to forming a successful coalition? Are neighbours more likely to pick up the phone to each other? How do the biggest member states regard each other? How do the oldest? Based on the experiences and views of the professional class – practitioners in government and experts from all member states of the EU – this policy brief and the underlying compendium of data and findings (see box bottom-left for more details) seeks to identify and to map clusters of interests, preferences, and reputations to show which member states are essential to coalitions seeking to lead, govern, or to advance European integration.

This information is important yet belongs to the ‘known unknowns’ of EU policymaking. Everyone involved has views on how interaction works with other member states, how important or marginal they are to one’s own government and policy, which issues should be driven in the EU as a whole or via smaller groups of member states. But the views of others are mostly unknown because they are largely undisclosed. Political communication is highly intentional, and formats for a frank exchange of perceptions do not exist. This web of perceptions, expectations, and experiences that closely or loosely connects member states is truly invisible. It exists but normally cannot be seen. Here lies the unique contribution of this study in that it aggregates the perceptions of each other and visualises patterns of perception that member states have.

The ‘cooperation community’: Patterns of interaction and preferences within the EU

In order to identify a group of forerunners that might be most likely to take forward the European project in a time of Euroscepticism, one needs to identify cooperation preferences within the EU. A ‘progressive group’ – in the sense that it seeks to advance the level of integration – necessarily consists of a number of like-minded member states that contact each other frequently and cooperate satisfactorily. Which member states share most interests, contact one another first or most often, and find each other most responsive?

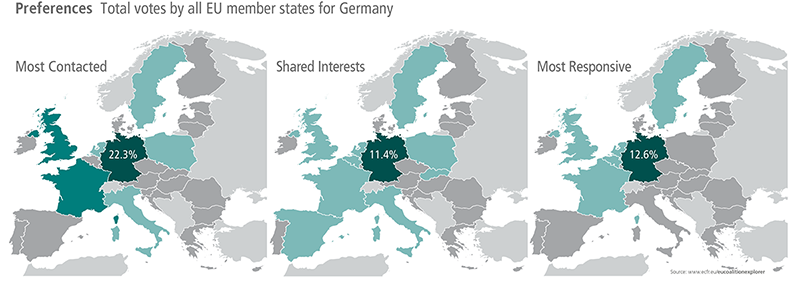

Germany, France, and the United Kingdom – the ‘Big Three’ – lie at the heart of Europe’s cooperation patterns. This is an intuitive assumption which was confirmed by ECFR’s EU28 Survey 2016. The ‘EU28’ – respondents from across all the member states – identify Germany as the member state which is by far the most contacted, the most like-minded, and the most responsive. This is followed either by France and, despite the Brexit vote, the UK. On these three cooperation indicators – shared interests, contacts, and responsiveness – Berlin consistently ranks first across all three, and Paris and London second or third. The same holds true for the Big Three themselves: when respondents from those countries are asked to comment on one other, they reckon themselves the most like-minded and responsive countries within the EU, and contact one other continually. Thus, in the eyes of EU and foreign policy professionals in Berlin, Paris, and London, there is potential for more joint leadership between the largest three member states. This is also acknowledged in capitals around the EU – an unaccounted cost of Brexit.

Glossary of terms

Big Three – France, Germany, United Kingdom

Big Six – France, Germany, United Kingdom, Italy, Poland, Spain

Affluent Seven – Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Sweden

Southern Seven – France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Cyprus, Malta

Founding Six – France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands

Visegrad Four – Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia

Cooperation Community – France, Germany, United Kingdom, Italy, Poland, Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden

Besides Germany, France, and the UK, there are a number of member states that also score highly on each of these three cooperation parameters. These are the other three big member states (Italy, Spain, and Poland) and two smaller affluent members – Sweden and the Netherlands. Respondents from across the EU share approximately as many interests with these countries as they do with France and the UK. Poland, Italy, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Spain are contacted most frequently after the Big Three. Respondents consider Poland, Spain, and Italy to be fairly responsive, and consider the Netherlands and Sweden to be as responsive as France and the UK.

There are, in turn, strong ties among these eight countries that lie at the heart of the EU’s cooperation preferences – which makes for an identifiable ‘cooperation community’. Indeed, in their top ten of most like-minded, contacted, and responsive member states, respondents from the ‘Big Six’ (France, Germany, the UK, Italy, Poland, and Spain) name Sweden and the Netherlands and all the big members, except for Poland. Stockholm and The Hague cooperate frequently and satisfactorily with each other and inter alia with Berlin, London, and Paris. Cooperation patterns within the EU’s ‘cooperation community’ set European integration in motion.

Interestingly, the rather wealthy small member states of the EU, labelled here the ‘Affluent Seven’ (Sweden, Denmark, Finland, the Benelux states, and Austria), show less cohesion as a group than their economic and fiscal interests, or their policy preferences, would suggest. Rather, the group consists of two subgroups with a focus on each other, and Austria, which appears least connected with the group of all seven. The highest ranked countries among the Affluent Seven, the Netherlands and Sweden, show higher levels of connectedness beyond their subgroup. The Netherlands is somewhat more closely connected to Sweden than it is to Belgium; the same applies to Stockholm’s connection to The Hague compared to Copenhagen.

Two further geographically defined groupings within the EU, the ‘Southern Seven’ (France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Malta, and Cyprus) and the Visegrad Four in the east, form their own cooperation communities. Countries in both groups share more interests with the members in their region than the EU28 do. But both are inextricably linked to their cooperation community: the big members in the south (France, Italy, and Spain) and the east (Poland) are not only at the heart of their regions’, but also of Europe’s, cooperation patterns. Moreover, the Mediterranean and southern members extend their network beyond those who are geographically closest and who they cooperate frequently and satisfactorily with, like Germany and the UK.

Ranking influence within the EU

In autumn 2016, after the Brexit vote and the apex of the refugee crisis, policy professionals around the EU were most likely to express disappointment towards – in descending order – the UK, Hungary, Poland, France, Germany, Greece, Austria, Italy, and the Netherlands. A year earlier, Germany did not appear on that list, which was then headed by Greece, the UK, and Hungary. Evidently, the handling of the refugee crisis changed that order, but not as much as to bring Germany near the top of the list. Discontent is directly related to instances where member states have either recently brought about a major European challenge or sought to take a lead in responding to one.

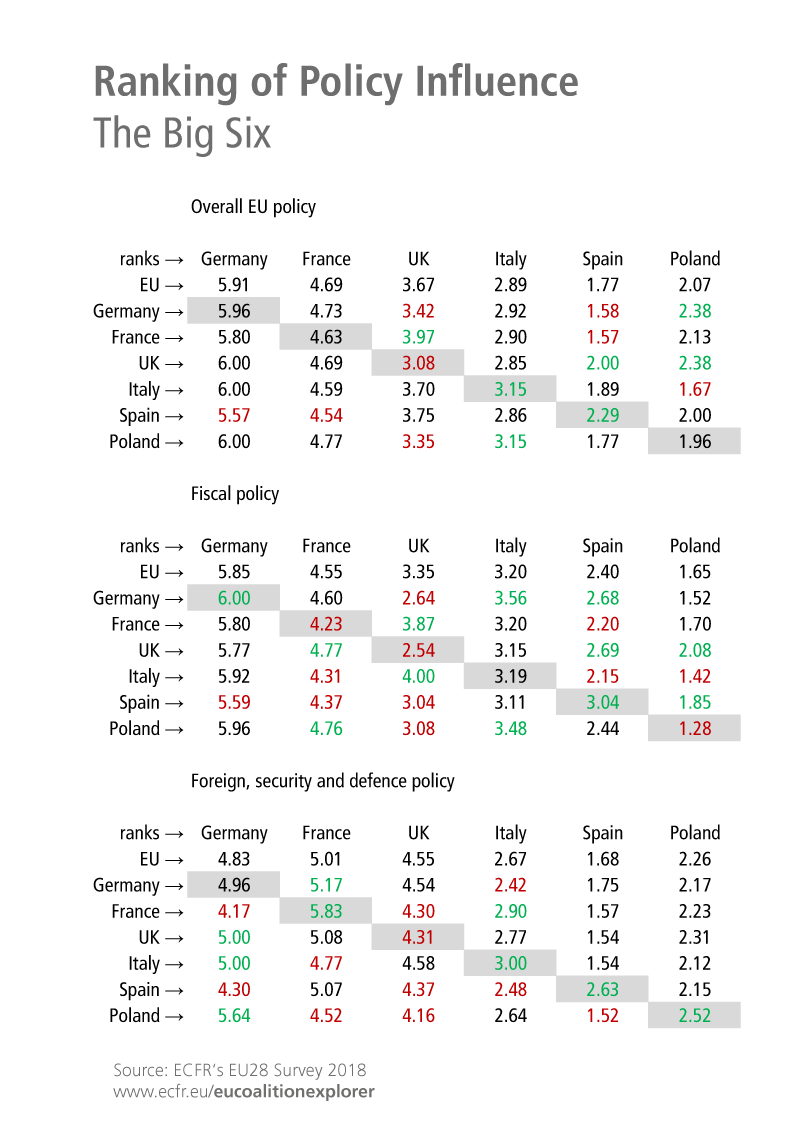

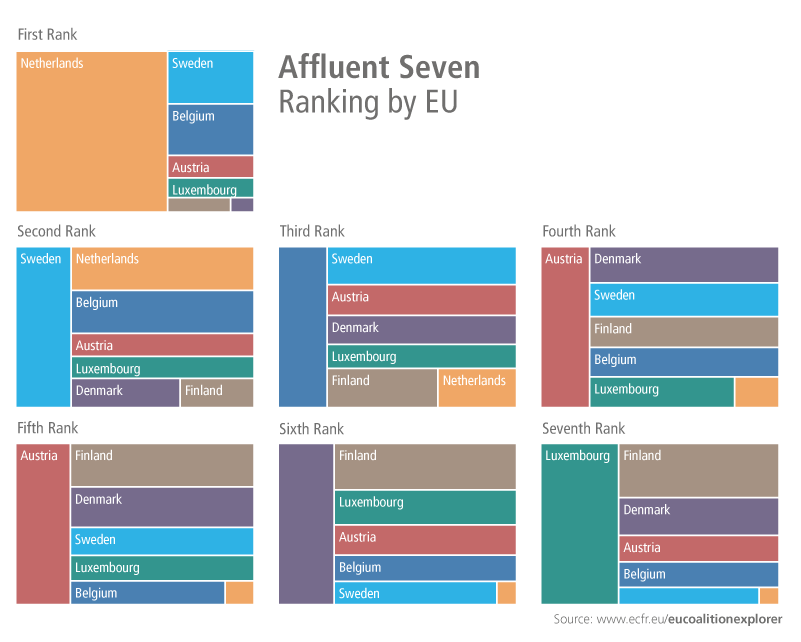

Less volatile over time, however, are judgements around the influence that member states have on EU policymaking. Respondents were asked to rank the six large member states according to their influence on EU policy in general, on foreign, security and defence policies, and on fiscal policies over the past five years. Additional questions asked respondents to rank the general policy influence of the Affluent Seven and the other EU member states.

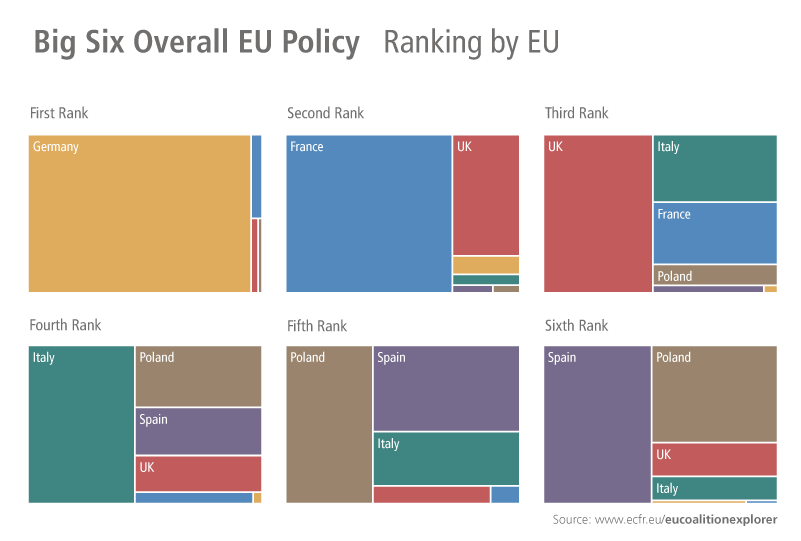

Ranking the influence of the Big Six

Focusing on the largest countries, and their influence on EU policy in the last five years, Germany is unequivocally considered by the EU28 to have been the most influential (see figure bottom-right). There is a lower yet substantial degree of consensus about France ranking second; a small part of the EU’s policymaking and expert community contends it has been the third most influential country. There is less consensus about the influence of the other large members (the colours representing them are to be found across different ‘rank rectangles’). The UK is most often, but not universally, ranked third; and Italy, Poland, and Spain as fourth, fifth, and sixth respectively. Perceived influence does not necessarily follow size or economic weight. The case in point is Poland, which is held by most respondents to rank between positions four to six, with the largest bracket being five. Respondents are equally likely to place Spain between fourth and sixth position, but it is the commonest choice for sixth most influential member – even though the country is larger than Poland and has been an EU member longer, is a member of the eurozone, and boasts a GDP 2.5 times the size of Poland’s. Here, the disruptive power of the financial crisis has diminished Spain’s previously rather active and strong role in European policymaking.

Although the Visegrad Four does perceive France as the second most influential of the Big Six, a higher percentage of policymakers and experts from the Visegrad countries ranks it third. Similarly, the Southern Seven estimate the influence of France on EU policy to have been lower. Moreover, Mediterranean Europe ranks Poland lower: these countries rate it sixth more often than the EU28 as a whole do.

How do the largest member states rate themselves? At first sight, the Big Six’s classification of itself is identical to that of the EU28, with Berlin in the lead and Madrid last. There are, however, some telling deviations from the EU28’s ranking. First is the degree of consensus about those countries believed to be the most influential. German respondents indicate that they are fully aware of the mark their country makes on EU policy; like their European colleagues, 95 percent ranked their home country in first place. French and Spanish policymakers and experts ultimately acknowledge German leadership, but with a lower degree of consensus: a small minority thinks France has been ahead of Germany. The UK ranks third in the eyes of the other big member states, but a fair share of the British respondents feel that their country has had the least influence on EU policy in the last five years.

There are also differences in the degree of consensus among the Big Six about the lower ranks. German and French respondents rate less the influence of Italy and Spain, which they rank five and six respectively more often than the EU28 do. Italian and Spanish respondents, in contrast, believe their countries have influenced European affairs more than the figure below shows. Poland’s policy community seems to consider itself the weakest link in the ‘Weimar Triangle’ of Poland, Germany, and France: among the Polish respondents, the degree of consensus about Germany and France ranking first and second is clearly higher than their agreement on where to place Poland. In the Polish view, it ranks fifth (as is the view of all and of the Big Six) but less clearly so.

Ranking the influence of the Big Six in specific policy areas

The view among the Big Six about which countries are considered the most influential changes significantly when questions move on to two distinct policy areas: fiscal policy, and security and defence policy.On fiscal policy, consensus among policy practitioners and experts in the Big Three countries falls apart. French and German respondents hold the UK’s influence to be significantly less in this area – with the French viewing their own influence as smaller than it is, in fact, seen by the other two. The French thus hold a notably more positive view of British influence than colleagues in Germany do. In the German view, eurozone membership carries more weight, meaning that Italy and Spain are seen to be more influential than the UK.

Even larger differences emerge both among all respondents and among those from the Big Six when looking at the ranking of the Big Six member states in security and defence policy. Regarding all respondents, the level of consensus is visibly lower compared to the other questions involving ranking countries in order. In addition, the differences between self-assessment and judgement by others are higher here. Views of one’s own country correspond rather strongly with those of the respondents overall in the cases of Italy, Spain, and Poland, which all show a somewhat more positive self-perception compared to views by others. But the gaps grow when looking at Germany, France, and the UK.

In contrast to the other subject areas and to the overall EU28 view, the Big Three do not consider Germany to be the lead influencer on security and defence. Respondents from all three countries put France first, in France itself by a big margin, and by rather smaller margins in Germany and Britain. However, British respondents see Germany as more influential than their own country – a view not shared by the French respondents, who put Britain second after their own.[1]

Ranking the influence of the Affluent Seven

How much influence on EU policy do the two smaller countries in the EU’s ‘cooperation community’, Sweden and the Netherlands, possess in comparison to the other members of the Affluent Seven? A clear majority

(nearly two-thirds) of the policymakers and experts across the EU say that the Netherlands has been the most influential member of this group. The influence of the other smaller affluent member states, including Sweden, is contested, with no majority view resulting (the colours representing them feature in all ‘rank rectangles’ – see ‘Affluent Seven’ figure on page 7).

Respondents from the Big Six and the Visegrad Four also rate the Netherlands as most influential over the last five years, but by less of a margin when compared to the EU28 view; these groupings rank Sweden first more often than the EU28 does. The Visegrad countries rate the other Nordic members, Denmark and Finland, respectively higher and lower than that which is displayed on the left.

The Southern Seven deem Denmark and Austria slightly more, and Sweden slightly less, capable when it comes to whether they ‘punch above their weight’.

The intra-group and self-perception of the affluent smaller countries is highly comparable to the EU28’s view of them: only the Netherlands stands out – with 71 percent, even more than among the EU28. Dutch respondents concur: the same percentage of the Dutch respondents to the EU28 Survey 2016 placed their country first. Across the Affluent Seven countries, a larger share of policymakers and experts rank Sweden second and Austria fourth. This is more favourable than the view of the EU28 as a whole. The Finnish policy community considers its own influence to be smaller, and Danes position Copenhagen most often directly behind The Hague and Stockholm. The degree of consensus about Luxembourg having had the least influence on EU policy is higher among the Affluent Seven than it is in the EU28.

Looking at other countries beyond the large member states and the Affluent Seven, a different pattern emerges. Here, EU and foreign policy professionals around the EU attribute the strongest influence to ‘spoiler’ governments in EU policymaking, clearly putting Greece and Hungary at the top of the list, followed by Ireland, the Czech Republic, and Portugal – two programme countries in the eurozone and a traditionally more sceptical EU member state.

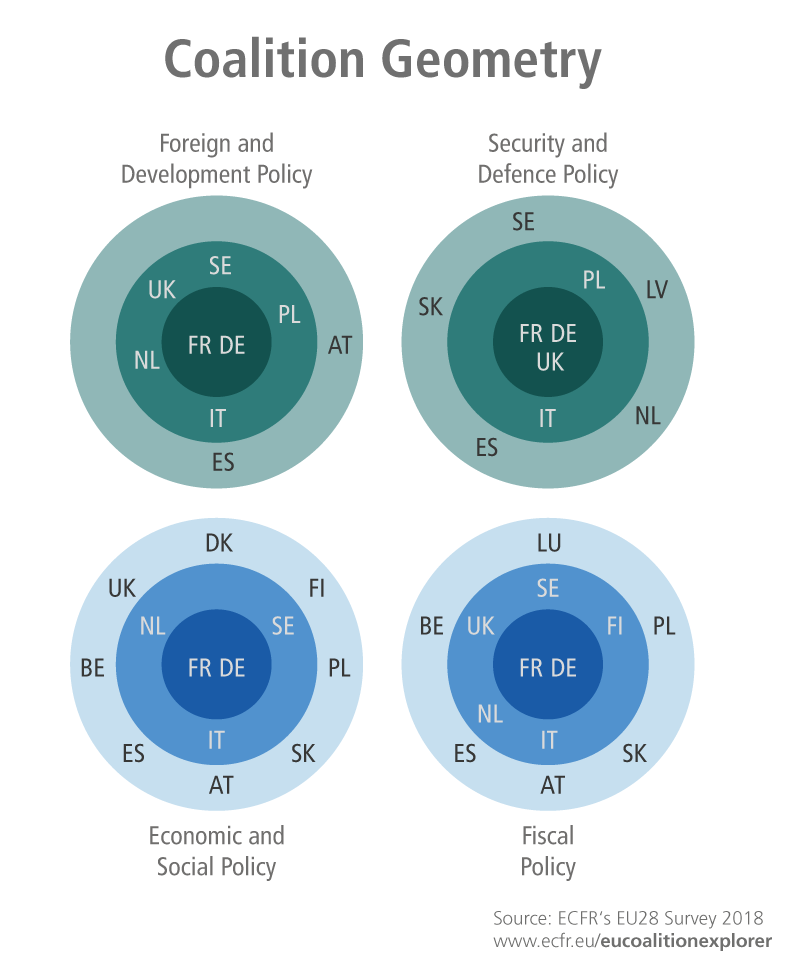

The inner circles of EU member states

Another way of assessing relationships between member states is to understand which member states are deemed to be relevant in which policy areas. Governments will consider others to be ‘essential partners’ when their interests converge and when a counterpart country is viewed as responsive and relevant to the issues at hand. The views of EU and foreign policy professionals among the EU28 confirm that assumption. To dig deeper into this, experts were asked to list which countries they consider to be essential partners in driving forward: foreign and development policy; security and defence policy; economic and social policy; and fiscal policy.

The EU28 results reveal 16 member states which are listed most often as essential partners, of which only eight countries come out strongly in all four policy areas. These were the six large member states along with the Netherlands and Sweden – the same group of countries which stood out in the analysis of how interaction preferences influence policymaking.

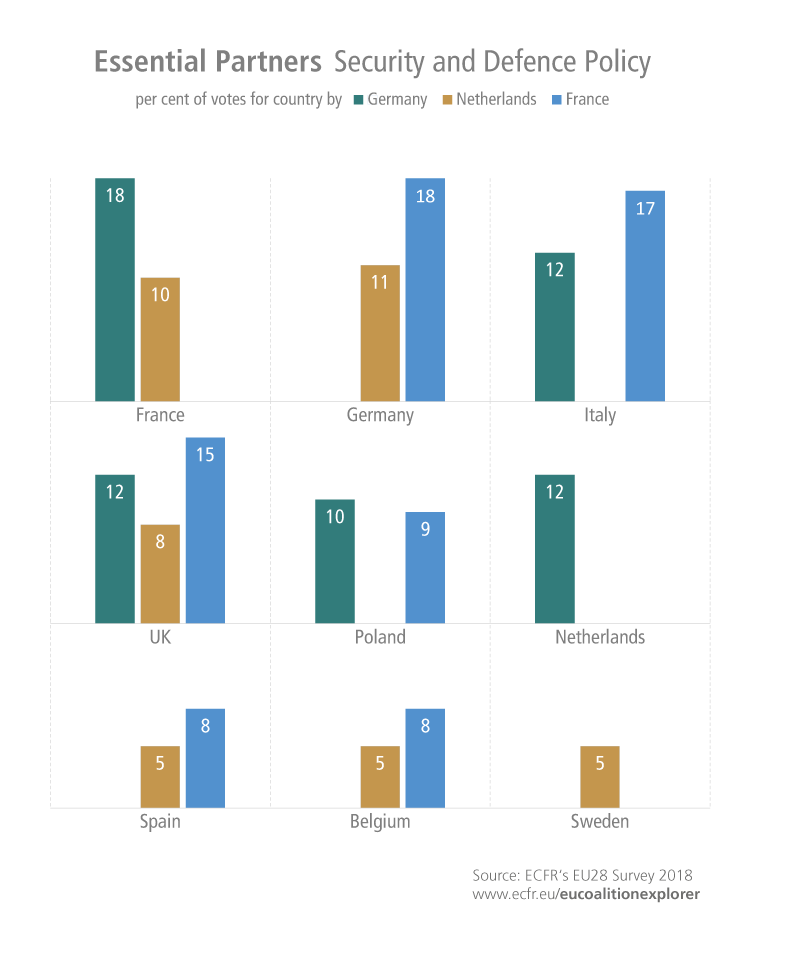

The graphs for each of the four policy areas show which member states were nominated by most respondents as ‘essential’, grouped by the strength of consensus and controlled by the peer view (see page 8).[2] The Big Six are deemed to be essential in all four areas, though to different degrees depending on the issue in question. Germany and France lead the tables, as the consensus on their crucial role in all four areas is strongest. This is reinforced by the respective assessments of the French and German panels; indeed, each sees the other as more essential than they are seen in the overall results. No other member state receives comparable nominations, except for the UK in security and defence policy. High readings are found for Italy, which consistently holds a place in the second tier. Poland is found in the second tier as well, but only on the two external policy dimensions. The nominations for Spain put the country in the third tier in all four areas. The Netherlands and Sweden are seen as essential on the second-tier level in all areas except for security and defence.

The graphs for each of the four policy areas show which member states were nominated by most respondents as ‘essential’, grouped by the strength of consensus and controlled by the peer view (see page 8).[2] The Big Six are deemed to be essential in all four areas, though to different degrees depending on the issue in question. Germany and France lead the tables, as the consensus on their crucial role in all four areas is strongest. This is reinforced by the respective assessments of the French and German panels; indeed, each sees the other as more essential than they are seen in the overall results. No other member state receives comparable nominations, except for the UK in security and defence policy. High readings are found for Italy, which consistently holds a place in the second tier. Poland is found in the second tier as well, but only on the two external policy dimensions. The nominations for Spain put the country in the third tier in all four areas. The Netherlands and Sweden are seen as essential on the second-tier level in all areas except for security and defence.

Of the other countries, Slovakia stands out – it is listed in the third tier in all four areas except for foreign and development policy. The same result is shown for Austria, which is listed everywhere except on security and defence. The figures for both countries contrast with their results in the previous sections. There, Austria appeared as the least connected among the Affluent Seven, and Slovakia did not receive high marks, even from its Visegrad neighbours.

Though partnership patterns can be found throughout the EU, the degree of variation is significant. In many cases, neighbouring countries consider one another essential partners. For example, the Visegrad Four overall rate each other rather highly as essential partners in security and defence, except for the Polish sample, which rates the Czech Republic and Slovakia much lower than vice-versa. All Visegrad countries name outside partners as more essential than other Visegrad countries, mostly Germany, followed by France and the UK. Hungary, however, assigns the highest marks to other Visegrad countries. The other clusters studied in this analysis, such as the Southern Seven, do not show any significant differences from the overall view.

Thus, specific results for individual countries show quite some variation, even when bilateral relations are very strong. A comparison of French and German assessments illustrates this observation well (see bottom-left). The graph contains only those countries listed as “essential partners” in security and defence by the German, Dutch, and French respondents.

The listing by German and French policy professionals reveals overlap between them, with both sets of respondents ranking the other top. Both also name the UK, Italy, and Poland. However, the judgements also show significant difference: three of the seven countries named most by both respondent samples are listed by only one side. The Germans list the Netherlands, and the French name Belgium and Spain. Adding the Dutch view to comparison makes the difference even greater. Professionals from the Netherlands list France and Germany as their top essential partners. The French view of the Netherlands, however, is non-reciprocal while the German view is. On the other hand, the Dutch sample shows more overlap with the French than with the German view.

The listing by German and French policy professionals reveals overlap between them, with both sets of respondents ranking the other top. Both also name the UK, Italy, and Poland. However, the judgements also show significant difference: three of the seven countries named most by both respondent samples are listed by only one side. The Germans list the Netherlands, and the French name Belgium and Spain. Adding the Dutch view to comparison makes the difference even greater. Professionals from the Netherlands list France and Germany as their top essential partners. The French view of the Netherlands, however, is non-reciprocal while the German view is. On the other hand, the Dutch sample shows more overlap with the French than with the German view.

Coalition-building: issue areas

Previous sections have provided insight into the perceptions of practitioners and experts on the connectedness of EU member states and the respective standing of governments among their peers. The centrality of Germany and France, as well as the critical role of the other ‘Big Six’ member states, are apparent. Smaller member states such as the Netherlands or Sweden emerged as well-connected and highly respected actors. Clearly, coalition-building in the EU needs to involve large member states, but must also attract smaller ones in order to develop critical mass. This section seeks to take these findings one step further by looking at these eight countries through the prism of particular coalitions and policy issues.

Nearly everyone in the professional class (97 percent) believes coalition-building to be fairly or very important at present. Coalitions are a means of managing a large and heterogeneous EU. In doing so they could be used in three different ways: they could act as pressure groups to drive consensus among all member states; they could act as forerunner groups to build deeper integration among a smaller circle of member states; or they could aim to block or veto action at the EU level.

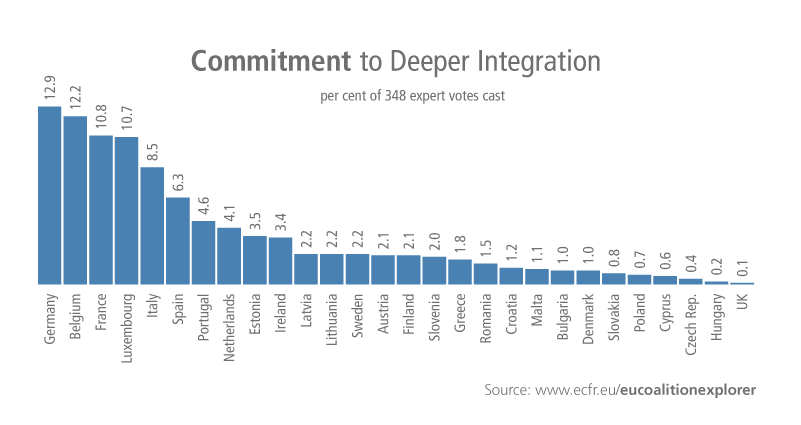

The classic case of such an integrative coalition would be the six founding members of the EU. The Founding Six do not necessarily set themselves apart as a group by a high level of interaction. In the different parts of the survey the results do not suggest that they are an especially close circle. However, the survey does show that these states are strongly associated with supporting “more Europe”. All six founding member states are at the top of the country list that the EU28 respondents consider to be most “committed to deeper integration”. The Netherlands is generally seen as the least integrationist of the six, a view that is fully shared by the Dutch respondents to the survey. Italian respondents perceive their country as slightly more integration-minded and French respondents perceive their country as slightly less so.

Preferred actor level

At the present time in the EU, the traditional route towards deeper integration appears closed. It is conceivable that agreement could be reached among governments on a mandate to seek treaty reform. However, some member state governments are simply opposed to “more Europe”, and so any intergovernmental conference to consider the proposals of a reform convention would unlikely come to agreement. Some countries would seek to allow agreement at such a summit only for the highest price. Even if a treaty change were somehow agreed, ratification in all member states would be needed.

It is this scenario that looms large over member state governments’ calculations about a differentiation of integration. It shaped the debate of the leaders of France, Germany, Italy, and Spain in their separate summit at Versailles to prepare for the Declaration of Rome. There could therefore be up to three practical ways of taking integration forward. Instead of all member states advancing together, one could see the following:

- a group of member states goes ahead as a core on a binding legal base under the treaties (using the clauses on enhanced cooperation) or outside the EU’s legal framework based on its own treaty;

- a ‘coalition of the willing’ gets together and informally cooperates more closely;

- policy issues kept at or returned to the national level.

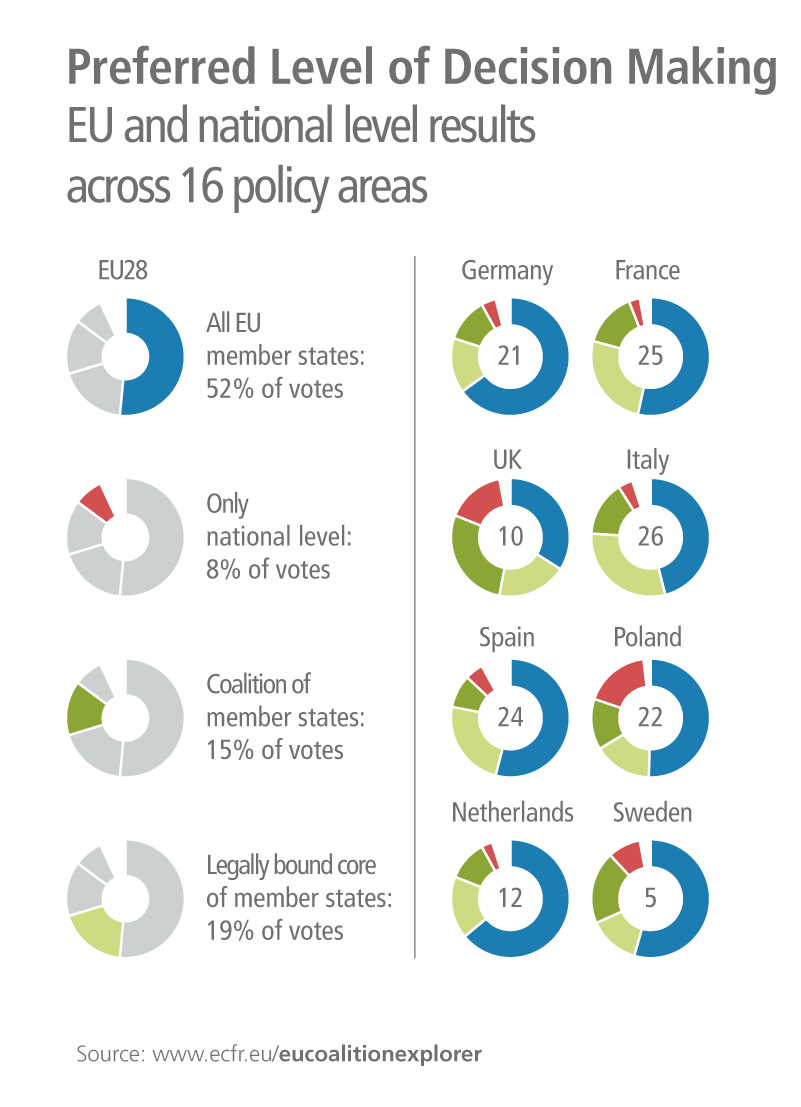

The EU28 Survey reveals that policy professionals around the EU are seriously considering differentiation along these lines. Respondents were asked to indicate on which level of governance they preferred policy action to take place (on 16 listed issues – see next section for more detail on policy-specific results). How would they want to see a policy conducted? Respondents were asked to choose from four scenarios: all member states together; by a legally bound group; by an informal coalition; or by acting nationally.

The overall figures signal a significant potential for change: just 52 percent of all respondents would prefer issues to be dealt with at the level of all member states – a rather low number given the goals and commitments of member states under the EU treaties. The overall figure suggests that the professional class sees little chance of moving ahead collectively, even if many view this as the ideal, as suggested by the much greater optimism around EU-wide action on issues such as the single market, climate policy, or foreign and security policy. One-third of respondents would like to see either formal coalition, through a legally bound group (19 percent), or informal coalitions (15 percent). Given that these answers represent a clear departure from previous integration patterns, this approval rate for coalition working is quite high. The highest scores for this appear for the issue of achieving ‘better governance for the eurozone’, an area which according to the treaties allows only for temporary derogation (except for countries like the UK and Denmark which have an explicit opt-out). Eight percent were in favour of either keeping or returning policies to the national level. Again, numbers vary significantly. The highest scores are found on the question of a common social policy, particularly in Hungary and among the Affluent Seven, whereas almost 40 percent among the Founding Six, and even more among the Southern Seven, would like to see a common social policy dealt with collectively.

The overall figures signal a significant potential for change: just 52 percent of all respondents would prefer issues to be dealt with at the level of all member states – a rather low number given the goals and commitments of member states under the EU treaties. The overall figure suggests that the professional class sees little chance of moving ahead collectively, even if many view this as the ideal, as suggested by the much greater optimism around EU-wide action on issues such as the single market, climate policy, or foreign and security policy. One-third of respondents would like to see either formal coalition, through a legally bound group (19 percent), or informal coalitions (15 percent). Given that these answers represent a clear departure from previous integration patterns, this approval rate for coalition working is quite high. The highest scores for this appear for the issue of achieving ‘better governance for the eurozone’, an area which according to the treaties allows only for temporary derogation (except for countries like the UK and Denmark which have an explicit opt-out). Eight percent were in favour of either keeping or returning policies to the national level. Again, numbers vary significantly. The highest scores are found on the question of a common social policy, particularly in Hungary and among the Affluent Seven, whereas almost 40 percent among the Founding Six, and even more among the Southern Seven, would like to see a common social policy dealt with collectively.

Different types of member state emerge from the data. First, there are the ‘integrationists’, which show a preference for dealing with policy issues collectively. Luxembourg, highly interdependent and strongly pro-EU, is the obvious case, but Germany and the Netherlands also articulate a strong preference for collective action on a number of policy issues. Then there are those with an above-average preference for legally bound groups of deeper integration, the ‘core Europeans’. France and Italy would fall into this category. A third type is ‘ad hoc coalitionists’, which receive higher marks for informal group-building across various policy issues. Britain is the obvious case in this regard, though it also shows higher readings than France and Germany on the core option as well as for the option of acting at national level. Furthermore, Britain is the member state with the lowest approval of a collective policy response. Finally, there are the ‘isolationists’, which show a strong preference for not acting on the level of all member states and also do not show much support for the coalition options. Hungary comes out first in this regard.

While the actor level preferences of the Big Six as well as of the Affluent Seven are similar to each other, the Mediterranean countries are slightly more inclined to form coalitions and are less focused on the national level than the EU28 as a whole are. Although the Visegrad group is generally portrayed as being less integrationist, the data shows that it is mostly Hungary alone that fits this image.

A comparison (see left) of the general actor level preferences of the eight most pro-coalition member states (the six large members, the Netherlands and Sweden) shows that Germany and the Netherlands are most willing to work with all EU member states, followed by France, Spain and Sweden. Italy traditionally favours ‘all-inclusive’ cooperation, but now leans towards selective partnerships. Member states like these, whose first preference is for

EU-wide working and which back binding contractual coalitions as a second preference, are (other than countries like the UK which have a significant preference for building loose coalitions) most likely to initiate or participate in a coalition that serves as a pressure group.

Preferred actor level on specific policy issues

The preferred actor level generally differs depending on the nature of the policy issue. On matters belonging to internal EU politics, member states are more inclined to form a ‘legally bound core’ and to work on the national level than they are when it comes to EU external policies. This also holds true for the eight-member ‘cooperation community’, although Spain is an exception to this, preferring instead to include all members on internal affairs in general.

A higher percentage of the survey respondents from across the EU indicated that their country would prefer to take part in a legally bound core in policy areas such as ‘justice and home affairs’ (30 percent) and ‘better governance for the eurozone’ (51 percent) than on EU affairs in general (19 percent). On ‘justice and home affairs’, Austria (57 percent), France, Portugal, Slovenia, Slovakia, Latvia, Estonia, and the UK favour this actor level substantially more often than the average. Less willing to bind themselves legally are the Visegrad Four, Bulgaria, and Lithuania; the Visegrad Four because they prefer national-level action, the last two because they prefer an all-inclusive approach. In the eyes of respondents from France, Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, and Finland (more than 60 percent), better governance for the eurozone is certainly something that should be sought.

On ‘common social policy’ (28 percent) more European policy professionals and experts prefer to work nationally than in other areas (the average overall being eight percent). The Visegrad countries (58 percent), but also Denmark and the UK show an even stronger preference to do so. However, Italy (lowest, at 0 percent), Spain, France, Austria, Portugal, and the Netherlands (highest, at 17 percent) are much more community-minded on social policy.

On EU foreign policy matters, the EU28 are more predisposed to seek to include all members and to form ad hoc coalitions than they are on internal policy issues. This finding is also valid for the Big Six, Sweden and the Netherlands.

Answers about ‘Russia and Ukraine’, ‘Border police and coast guard’ and especially ‘Climate policy’ (which stood at 71 percent) illustrate the strong preference for an EU-wide approach on policies which have a predominantly external dimension. While the Netherlands (92 percent), Finland, France, Germany, and Portugal are still more determined that the climate can only be protected if all countries work together, the preference for common action on climate policy in the UK, Poland, and Hungary falls below 50 percent.

A significant minority (27 percent) is inclined to favour a ‘Common defence structure’ as a loose coalition – a contentious issue in the contemporary debate indeed.

The UK in particular (80 percent) prefers a European ad hoc coalition alongside NATO. Finland (10 percent), Spain, Poland and Italy are less persuaded that European security can be guaranteed in such a way. A common defence for all member states has much higher support among otherwise rather diverse countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and Romania.

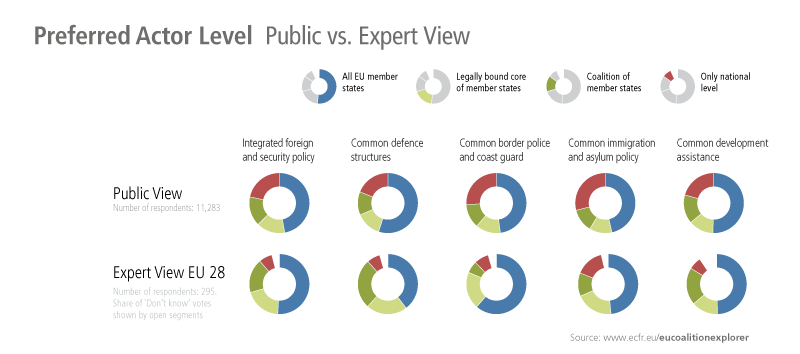

What does the European public think?

Many current European debates lament a growing distance between elites and the public. On the one hand, observers see a widening gap between international and pro-European elites and a more national and EU-sceptic public. On the other hand, the Eurobarometer poll reveals high levels of approval for ‘more Europe’ in foreign and security policy.[3] These results are sometimes used to argue that citizens are, in some areas, clearly more integration-friendly than the political elite. To compare the view of the professional class in the EU28 Survey with public opinion, the authors of this study ran a representative poll in the 28 member states in collaboration with Dalia Research Berlin to double-check preferences for the level of cooperation in different policy fields among the European public. The list of topics was broadly similar to that of the EU28 Survey and the poll was conducted just two months after the expert survey, in December 2016.

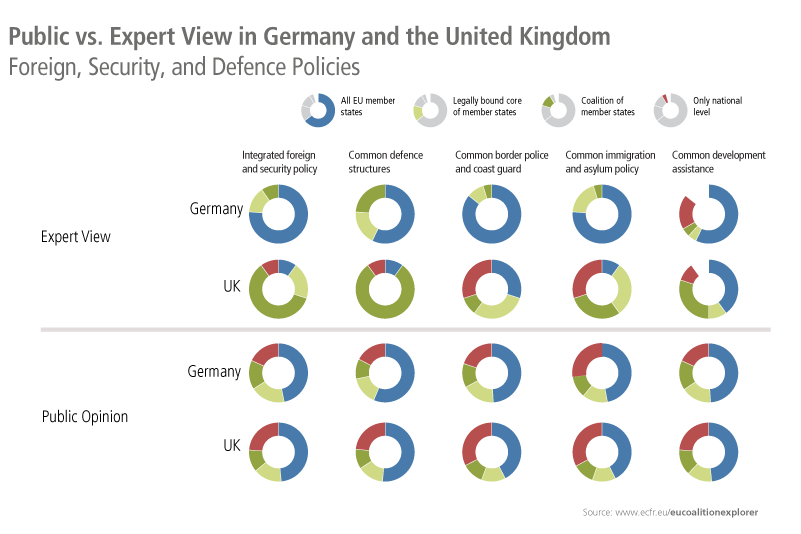

In comparison, EU citizens show a significantly stronger preference for the national level. Having to choose between European policymaking on the level of all member states on the one hand, or within a smaller circle on the other, public opinion is more critical of the idea of coalitions then the political class is. Multi-speed Europe or loose coalitions generally win less approval than acting together with all EU members. The chart above shows the core areas of policy fields in the foreign and security domain – the areas which always achieve high approval values in the Eurobarometer poll. Compared to the public opinion from our survey, approval rates for the national level are much lower among the professional class and their openness to coalition options is greater.

Public opinion often does not diverge between member states as much as it does in the expert study discussed in this policy brief. In the areas of foreign, security and defence policy, for example, the preferences of German and British practitioners and experts are almost the opposite. The attitude of the public in both countries, however, differs less strongly.

Conclusion

In a whole variety of forms, coalitions will shape the further development of European integration. Given the large size of the EU and the increasingly intergovernmental nature of its institutions and processes, coalitions of member states are indispensable to the governance of European integration. While the traditional role of the forerunner scenario – to frighten integration-sceptic governments and to enforce consensus – may still play its part in future, heterogeneity and divergence of interests in the EU has grown to a degree that scare-mongering will not be an effective counter to it. If coalitions are to move integration forward, they will have to become real in the sense of achieving results through joint action – and being seen to have achieved results. More so than in the past, European action will take place less on an EU-wide footing and more by either formal core groups or informal coalitions.

Against the preferences of the European institutions, initiatives of “more Europe” pursued by a coalition of member states could establish their own legal base, as participating countries may find the conditionality of “enhanced cooperation” or “permanent structured cooperation” too restrictive. Also, they likely would not want a situation to arise whereby those member states already blocking progress at the EU level would have a veto over these new areas of cooperation. Groups would claim legitimacy for their action by referring to goals which are laid out in the European treaties and accepted by all member states but which have not been achieved because of a persistent lack of political consensus.

The focus of such initiatives would necessarily be on those issues where the EU’s capacity to act seems to fall short of a demand articulated by many citizens. That has been the message of the European Council conclusions since the Brexit referendum. Should delivery fail, many leaders believe that initiatives should be taken by a smaller group of member states. At the top of the agenda of such a differentiation of integration are three clusters of policy challenges:

The effective control and policing of the EU’s external borders. This is a key issue for all members of Schengen. A core group could create a single border police and coast guard, deal with migration flows on the basis of common immigration and asylum laws, and establish a common fund to compensate participating countries for asymmetric shares of the burden. This would be funded through a joint budget by and for participating countries only. An initiative related to this field could also be launched around the issues of law enforcement, intelligence-sharing, and the prevention of crime.

The integration of defence capabilities to provide Europe with a credible common defence. Coalitions or cores could seek to merge key aspects of defence such as research, development, and procurement; command, control, and intelligence; logistics and support, from airlift and transport to medical services; or integration of forces under one command. As in the case of border security, the immediate benefits would apply to participating countries only, but the wider impact of successful initiatives would benefit the EU and its members at large.

Economic prosperity, social equality and fiscal sustainability as interdependent variables of economic governance. These would likely apply most to members of the eurozone. Here, a group of countries in the European monetary union could amend the rules on national budgets and make use of common financing instruments based on these rules. Tax harmonisation would make sense to participating countries as would the establishment of a common budget to act as a transfer scheme to balance budget asymmetries between members.

Alongside major projects like those sketched out above, different types of coalition could seek to address more immediate, narrower issues using the modalities of enhanced cooperation, as has been done on the European patent initiative. Here, practical issues which have lacked agreement among all member states could be addressed without much delay.

Initiatives in the three areas outlined above could hardly be done by ‘coalitions of the willing’. Most would require legal if not constitutional adaptation among participating countries and cooperation would thus be based on legally binding commitments. Participation could be based on material, legal, and procedural criteria derived from the requirements of the respective policy area targeted by deeper integration. It follows that the membership of different core coalitions would not be identical. However, there will likely be a significant overlap, and it would fall to the political lead role of member states engaged in all areas of differentiated integration to facilitate the cohesion of initiatives with the EU at large.

Informal coalitions would not suffice to take on the issues laid out in the above, as they do not pursue binding commitments among member states. Their role in EU policymaking could better play out in sensitive areas of foreign policy, such as crisis management on Ukraine by Germany and France, or the continuous engagement on Iran by France, the UK, and Germany. Here, member states’ clout as well as the informal nature of their cooperation appeared helpful to the cause. In a more general sense, informal coalition-building could become a strong tool in the agenda-setting and the political management of a diverse and otherwise fragmented EU.

Political centres

The findings of ECFR’s EU28 Survey illustrate the complexity of coalition-building in the current EU. While some obvious patterns and clusters of countries exist, the analysis shows that consensus or joint action depend to a large degree on the issue at stake. The eight member states most often listed – the Big Six, the Netherlands, and Sweden – are part of a political centre if they choose to engage, but do not constitute ‘the political centre’. The EU28 Survey has not found a centre in the modern-day EU, but has instead pointed to several central configurations, each of which could become the nucleus of coalition initiatives.

Analysis of preferences and positions of the political class in EU capitals has shown that any coalition initiative needs to resonate with the large member states if it is to succeed. With the UK exiting the EU, coalition-building should become somewhat easier, as the UK has generally been opposed to deeper integration. On the other hand, though, the research shows how essential a partner it is considered to be and that it is quite ready to engage in informal coalition-building.

France and Germany are very likely to emerge at the core of any future initiative. Both are not only intensely connected and highly recognised, they are also most valued by other governments as essential partners. Without one or the other, a coalition would not be viable. Because of linkages and joint interests, France would likely seek to add Italy or another southern member to a grouping, while Germany would seek to bring in Poland if possible. Using its coalition-building assets, Germany would also seek to strengthen its position by attracting countries such as the Netherlands and Sweden, as both could reach out to peers among the smaller member states, and both would be interested in bringing in countries close to their preferences from the Affluent Seven or eastern member states. From Berlin’s perspective, the involvement of a Visegrad country, such as the Czech Republic or Slovakia, would be welcome, to stabilise outreach to the east.

From the insight that future coalitions are to be built from such a patchwork, the demand may emerge for a political space or environment in which coalitions of whatever form could be conceived, planned, and advertised. It may need to be a virtual place, as the sessions of the European Council do not provide a conducive environment, and formal meetings in smaller settings provoke resistance and critique whenever they happen more regularly.

The building of coalitions, be they informal or legally bound, therefore requires the development and nourishment of a coalition milieu. The EU is in need of a renewed political sphere, which could become fertile ground for policy initiatives and a meeting place of potential stakeholders. This milieu would be an informal agreement to deal with policy challenges together, a space to cooperate in the conception and launching of policy initiatives, to politically mandate and support the EU’s institutions – and a context to assume a lead role in the management of a large EU.

[1] Experts ranked the Big Six according to their perceived level of influence on EU policymaking. Each country's total rankings were translated into a score between 1 and 6 points. Higher scores represent more frequent rankings in the top ranks, while lower scores correspond with lower ranks. For example, a country score of 6 points means that all experts placed that country first in their ranking of influence. The country in the vertical column ranks the country in the horizontal column; ‘high value = ranked very influential’. So, for fiscal policy, you would read: Overall EU ranks Germany high at 5.85. Germany ranks itself as most influential, with a perfect 6, which means that all respondents ranked Germany as the most influential country. France ranks Germany at a high 5.80 and the UK only 3.87. Spain is least convinced about German influence in fiscal policy in the group. The Spanish ranking gives Germany 5.59.

[2] A filtering of data in three stages was used to build a 'hierarchy of essentiality': For each national sample the numbers of nominations of other countries were expressed in percent, e.g. 11 percent of all French nominations of countries as essential partners for France named Belgium (14 percent named Italy). Ratings below 5 percent were discarded. Ratings higher than 5 percent were clustered in four brackets (5-9, 10-14, 15-19, 20 and over). The score for each country was calculated by adding up the nominations from other countries, using the brackets as multipliers (bracket 5-9 equalling 1, bracket 10-14 equalling 2 and so forth). Countries with a total score of 20 or higher were allocated to the inner ring, those with 10-19 points went to the middle ring, those ranging between 5 and 9 points were assigned to the outer ring. Countries scoring below 5 were discarded. Also, to be listed in the inner or middle ring, countries had to receive respective ratings from other countries also listed in either one of the two rings.

[3] : “#Eurobarometer: Europeans reveal what they want the EU to do more on”, EU Reporter, 5 May 2017, available at https://www.eureporter.co/frontpage/2017/05/05/survey-europeans-reveal-what-they-want-the-eu-to-do-more-on/.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.