The transformative five: A new role for the frugal states after the EU recovery deal

Summary

- The reputation of Austria, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, and Sweden as ‘frugal states’ does not reflect public sentiment in these countries.

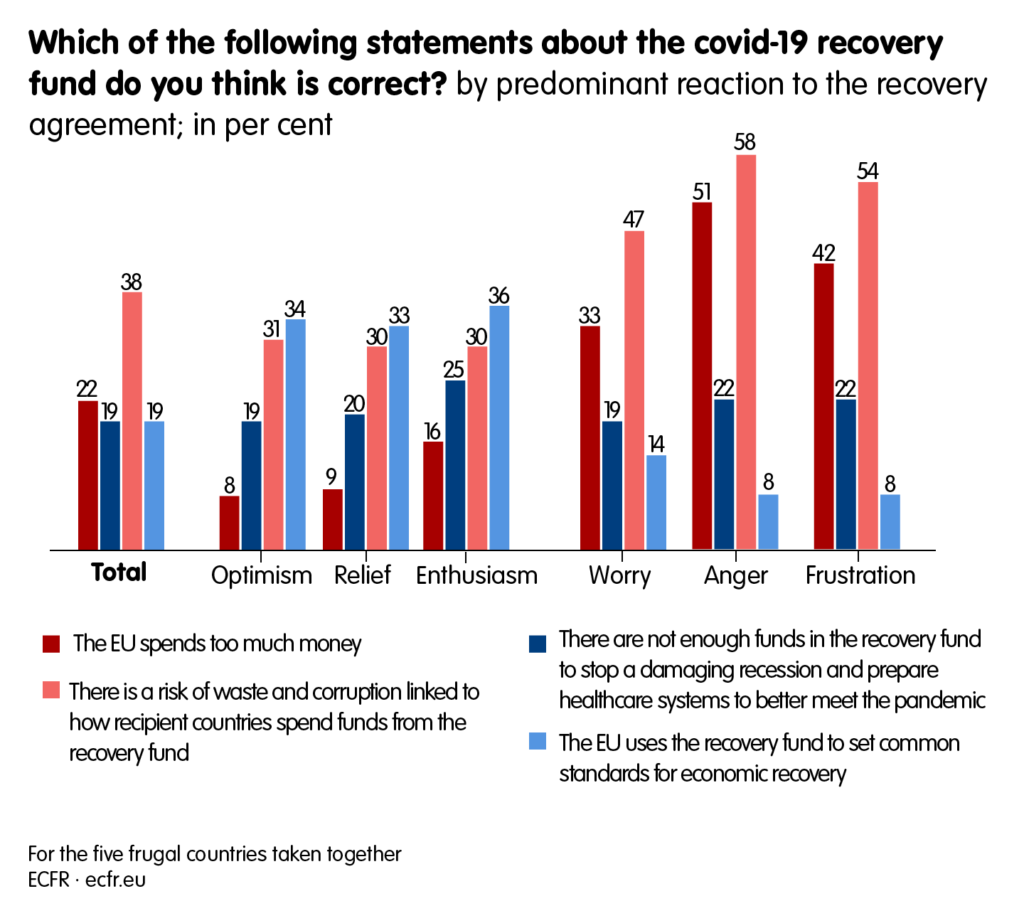

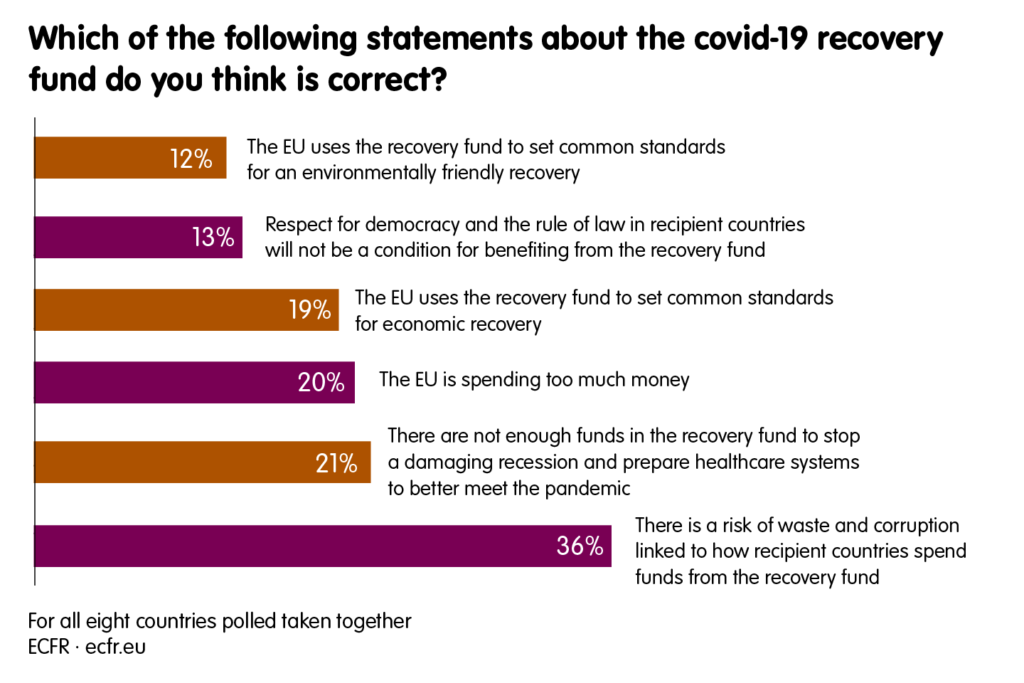

- Almost eight in ten voters in the frugal states do not believe that the European Union is spending too much money on its covid-19 recovery fund.

- Their bigger concern appears to be about waste and corruption linked to member states’ use of the fund.

- Voters in the frugal states have mixed feelings about the recovery fund.

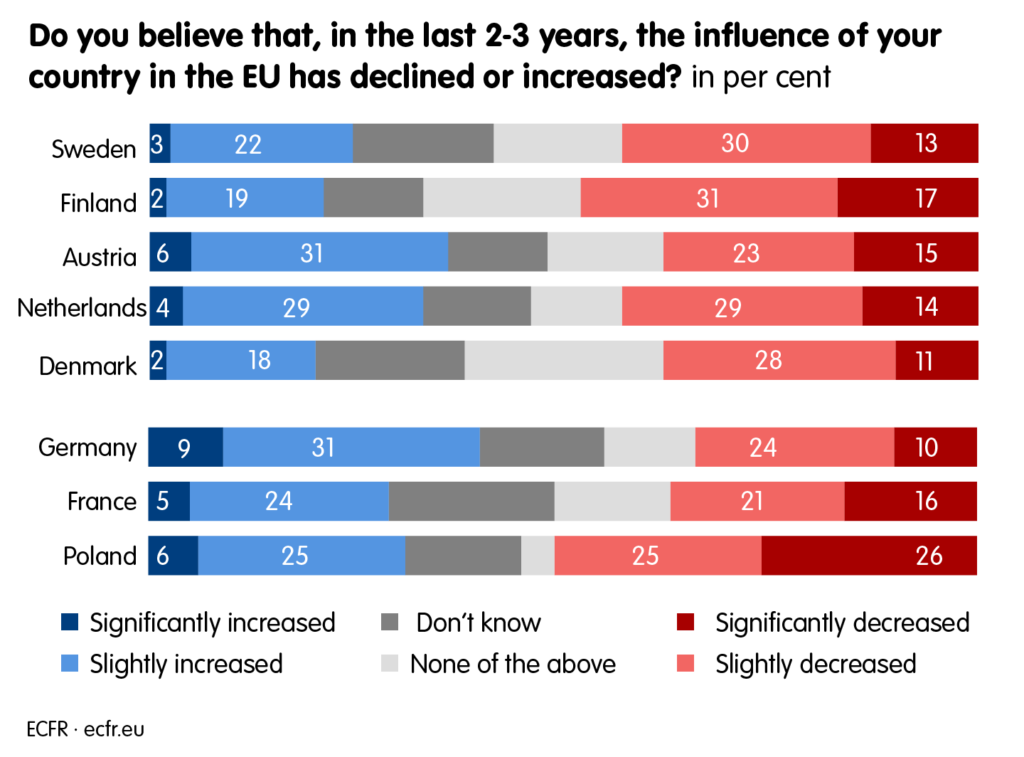

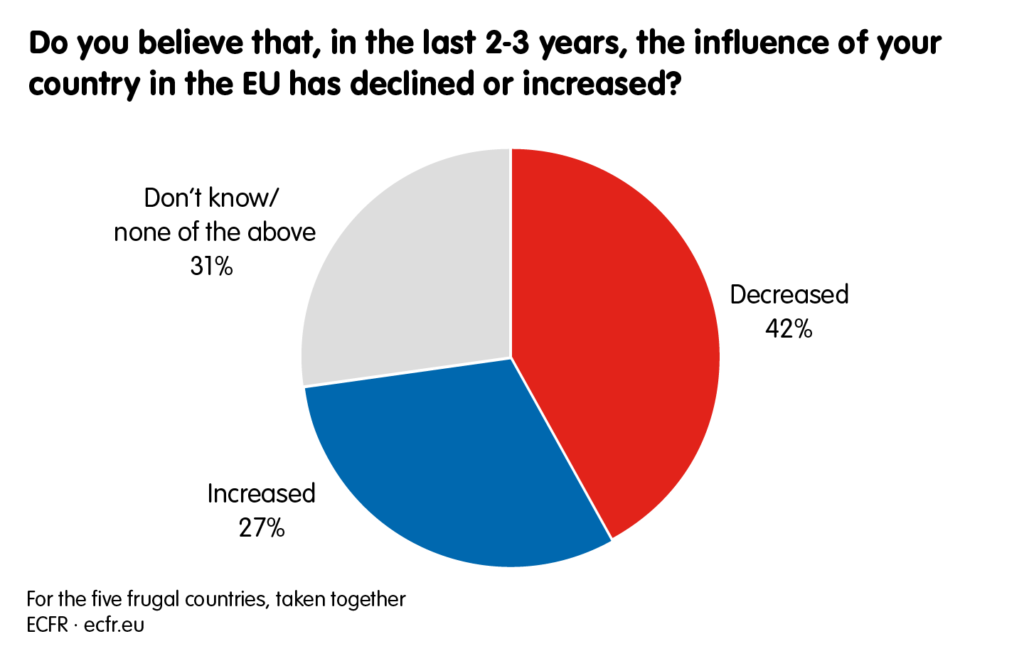

- More than four in ten of them believe that their country’s influence in the EU has declined in recent years.

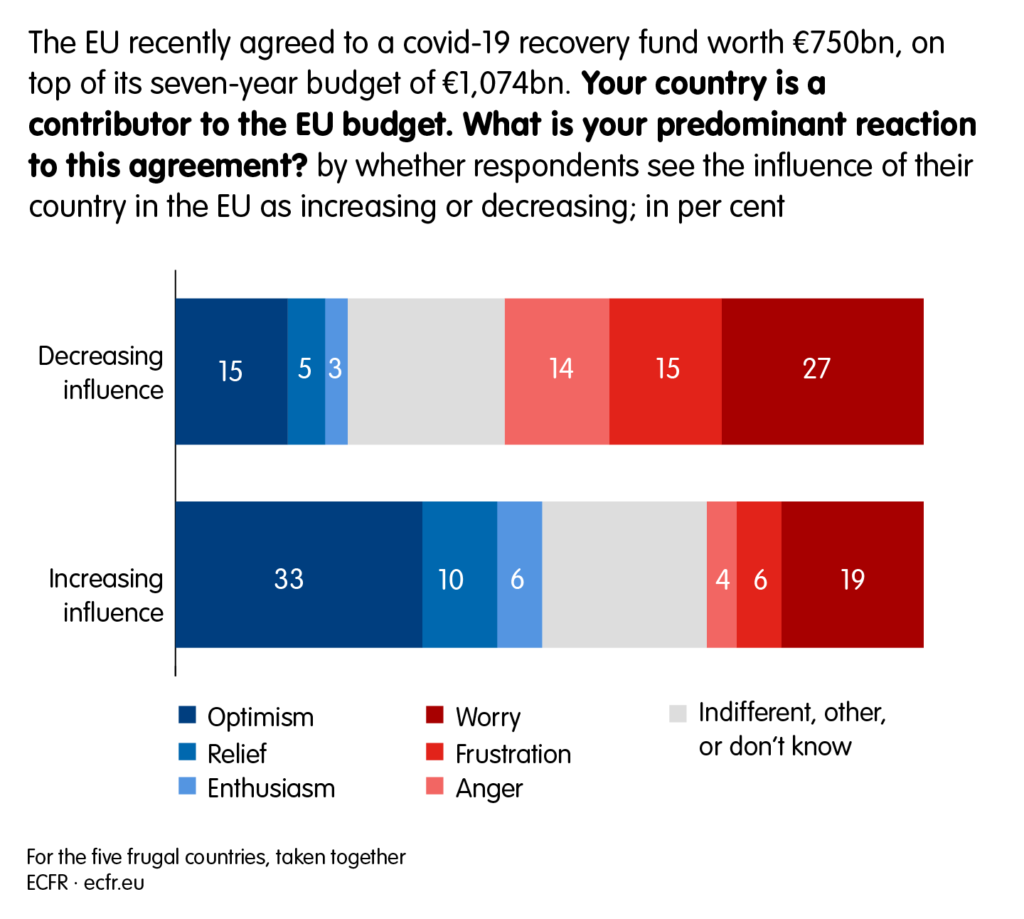

- This perception correlates with their feelings about the recovery deal and the state of the European project more broadly.

- The governments of the frugal states should reinvent themselves as the ‘transformative five’.

- This coalition would focus on reducing inefficiency and corruption in the use of recovery funds, harnessing it to shape Europe’s green transition and the future of the European project.

Introduction

When the history of the European Union in 2020 is written, one of the key developments it will reflect upon is the rise to prominence of the ‘frugal states’. The ‘frugal four’ of Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden are under the spotlight for their staunch opposition to increases in the EU budget. Their leaders – Sebastian Kurz, Mark Rutte, Mette Frederiksen, and Stefan Lofven respectively – even published a manifesto of sorts in an op-ed in the Financial Times in February this year. They argued that, though their commitment to the EU was as strong as that of their peers around the European Council table, they would not allow the bloc’s budget to exceed 1 per cent of its gross national income. And they called for “a system of permanent corrections to protect individual states from having to shoulder excessive budgetary burdens”.

In the following months, as the coronavirus hit, states across the EU felt a growing need for support from the shared budget. The frugal states maintained a firm position and even began to shape the discussion. In summer, Finland took up their cause – even if the country’s prime minister, Sanna Marin, denied having joined the frugals. But, though the frugal states secured national rebates for themselves, the deal on the EU recovery package they helped finalise on 21 July did not adhere to all their principles of financial prudence. In particular, the European Council agreed to large-scale EU borrowing on the markets to finance the fund, and to new EU money, more than 40 per cent of it in the form of grants. Back home, Rutte struggled to find positive words to describe the agreement, refusing to call it ‘historic’ as its supporters elsewhere had.

With such an underwhelming response from their countries’ leaders, citizens of the frugal states could have felt that the recovery deal was not in their interests. Even though the architects of the agreement wanted to bring member states together to ward off the worst effects of covid-19 and spur a green recovery, these voters may have believed that the arrangement did not reflect their vision of the EU’s future.

Such drift would have a profound effect on the nature of the European project. The governments of the frugal states are not only characterised by their risk-aversion in the expenditure of EU resources. They are also key to keeping Europe’s liberal instincts alive. As the European Council on Foreign Relations’ EU Coalition Explorer demonstrates, these states are champions of the EU’s agenda on multilateralism, foreign policy, digital issues, and the rule of law. They have taken on even greater responsibility in these areas since the 2016 Brexit referendum. (Before then, the United Kingdom was traditionally one of the EU’s strongest advocates of much of this agenda, and a more powerful force in the bloc than any of the frugal states individually.)

In October 2020, ECFR commissioned Datapraxis and Dynata to carry out a survey exploring whether voters in the five frugal states feel that, after the deal on the recovery fund, they could still buy into and identify with the European project. The survey also covered France, Germany, and Poland, for the sake of comparison.

Its results show that the frugal states’ adoption of the label of frugality does not reflect public sentiment. Though forming this coalition may have paid off tactically in the negotiations over the recovery fund, their future positioning in the EU should be informed by a more sophisticated understanding of citizens’ opinions on, and feelings about, Europe.

Citizens of the frugal states are not, in fact, frugal in the purest sense of the word. Almost eight in ten respondents in the frugal states did not agree with the statement that, with the recovery fund, the EU is spending too much money. Their bigger concern appears to be about how other member states spend their share of the EU budget, with almost 40 per cent reporting concerns about financial waste and corruption in this.

They have mixed feelings about the recovery deal – with Finland the only frugal state in which as much as 50 per cent of voters express negative emotions about it (anger, frustration, and worry). Nonetheless, at least 29 per cent of the population express positive feelings about the agreement (optimism, relief, and enthusiasm) in all the frugal states. Overall, their perception of changes in their country’s influence in the EU correlates with their views and feelings about the recovery deal – and appears to be crucial to their thinking about where the EU contributes the most to promoting their country’s interests.

This paper analyses the findings of ECFR’s October survey. It argues that, far from the frugal states being lost to the European project after the recovery deal, all is still to play for in making their voters feel that the EU is developing in line with their interests. The right policies and the right messaging can keep them on board. And the ‘frugal five’ can become the ‘transformative five’ – by shaping the EU’s foreign policy, supporting the European Green Deal, strengthening the single market and the rule of law, and contributing to other key areas.

National and European interests

Many EU watchers have debated whether the covid-19 recovery package is an institutional step towards a federal union. But, just beneath the surface, there is another strand of public discourse on the EU that may have greater long-term significance for the European project.

The 2008 financial crisis and the 2015 refugee crisis both triggered a strong nationalist backlash in Europe, with populist parties winning votes by arguing that EU institutions had failed voters. Covid-19 might still lead to gains for populists in the long term. In the Netherlands, Finland, and Sweden, populist parties lost some of their appeal during the first wave of the pandemic – but they have recovered since then and are currently on the rise. As things stand, Dutch politician Geert Wilders’s Party for Freedom (PVV) is polling at around 25 per cent of the vote. The Finns Party and the Sweden Democrats can rely on a stable 20 per cent. The radical right is doing less well in Austria and Denmark, but this may be partly because it is regrouping, with rival Eurosceptic initiatives trying to attract voters from more established parties.

But, as ECFR’s survey earlier this year showed, there are good reasons to believe that the crisis of 2020 will not lend as much weight to nationalists’ arguments as did the crises of 2008 and 2015. Populists – and the far right in particular – have tried to pin the blame for the spread of the pandemic on uncontrolled globalisation, and have called for a nation-first response. So far, the power of these arguments has been limited by Europeans’ recognition of the need to pool sovereignty on some issues at the EU level.

Many EU citizens felt vulnerable in the early stages of the covid-19 crisis as their countries turned inwards, with national healthcare systems struggling to find the resources they needed to fight the disease, and lockdowns leading to shortages of essential goods. As ECFR’s polling in April and May this year showed, EU citizens believed that the first step towards dealing with the uncertain international environment was for Europe to rely on itself in securing essential supplies. This sentiment was particularly evident in Germany and France, but extended across all surveyed EU states (which also included Italy, Spain, Poland, Portugal, Sweden, Denmark, and Bulgaria). In a world in which the United States is engaged in a fierce competition with China and has stepped back from global leadership, European voters have shown they want the EU to throw its weight behind international institutions – to help ensure that there will be a level playing field on which to mitigate the global economic and health crisis, to shape the digital future, and to address the climate challenge.

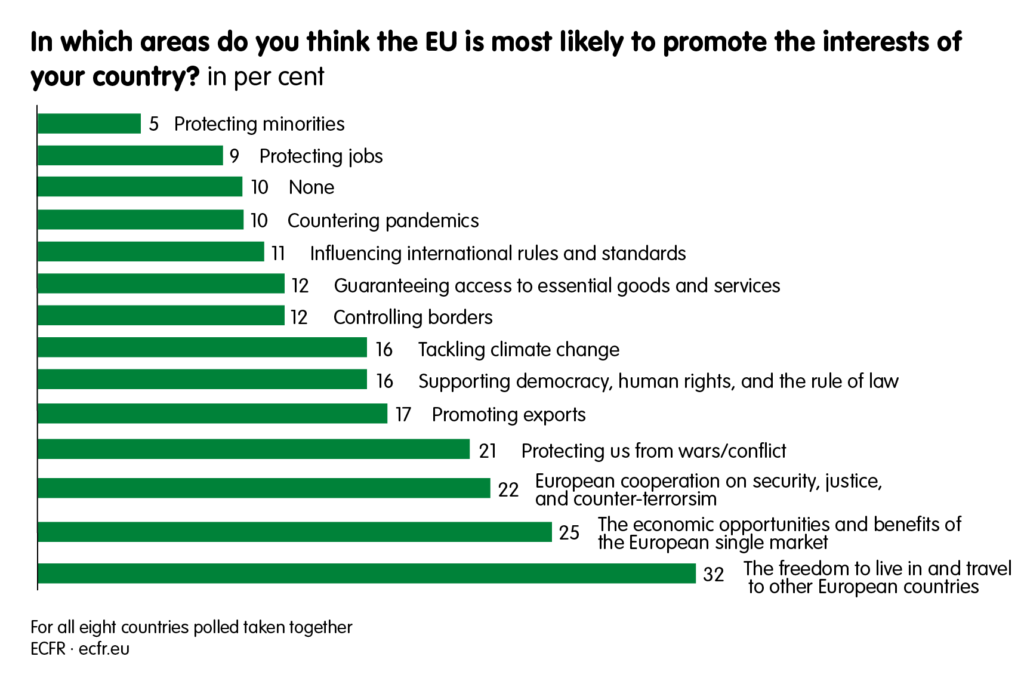

The new survey ECFR conducted in October 2020 suggests that the citizens of the frugal countries are not immune to this trend. Like their counterparts in other member states, they no longer see national sovereignty and European sovereignty as an either/or choice. They recognise the value of the role the EU plays in promoting their country’s interests. And, contrary to stereotypes, this goes well beyond economics. When asked about the areas in which the EU makes the greatest contribution to promoting their country’s interests, respondents to the October survey most often name the freedom to live and work in other countries; the single market; cooperation on security, justice, and counter-terrorism; protection from conflict; and exports. In most frugal states, less than ten per cent of respondents say that the EU does not promote their country’s interests in any area. The exception is Austria, where 14 per cent of respondents hold this view – compared to 16 per cent in France.

Given Scandinavian countries’ international reputation for tackling climate change, it is slightly surprising that so few people in these states recognise the EU’s contribution in this area: just 13 per cent in Sweden, and 15 per cent in Denmark and Finland. These numbers are similar to those in Austria (13 per cent) and the Netherlands (17 per cent), as well as in Germany (17 per cent) and France (16 per cent), with Poland an outlier on this issue (20 per cent). The frugal states’ limited appreciation of the EU’s climate role may stem from a lack of public discussion on the issue – as well as from the EU’s modest material achievements on this front so far.

Strikingly, in the frugal states, supporters of nationalist parties are relatively aligned with other voters in their perception of the top five issues on which the EU promotes their country’s interests. The main difference between nationalists and the rest is that the former – such as supporters of the New Right in Denmark, the Sweden Democrats, and the PVV – have much greater enthusiasm for the EU’s role in controlling borders than other voters in their countries.

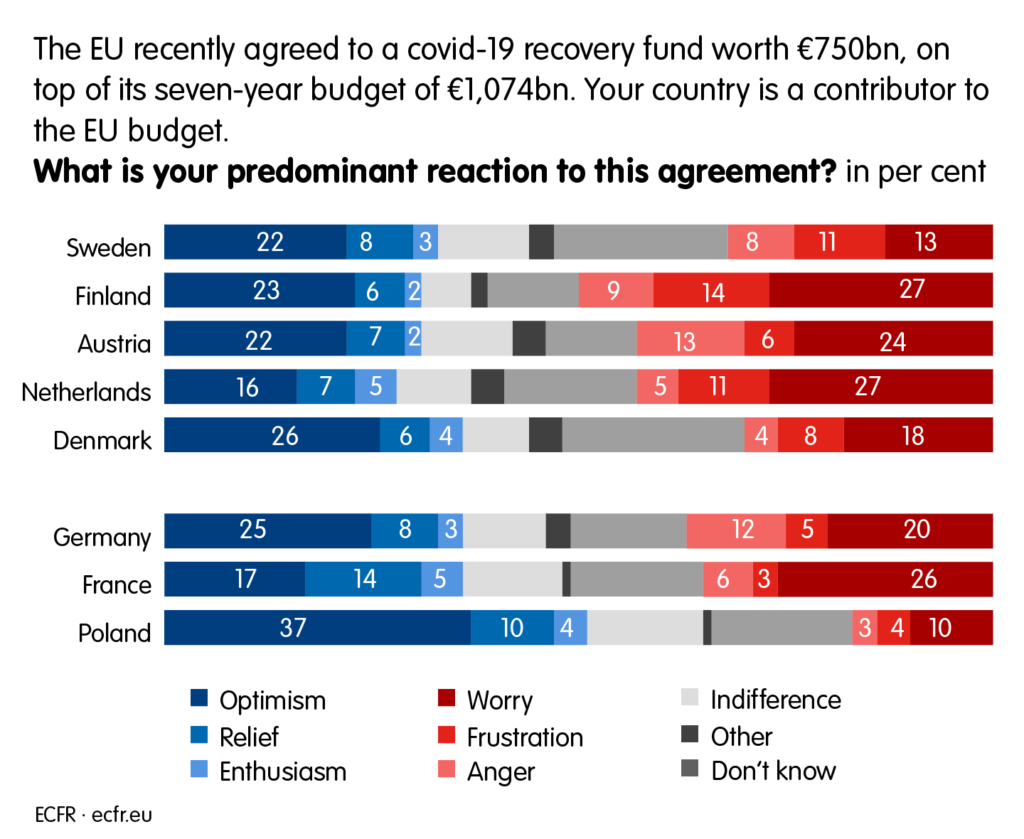

This recognition of the EU’s contribution in the frugal states may go some way to explaining their citizens’ mixed feelings about the EU recovery deal. In these countries, the overall balance of positive and negative feelings about the deal is similar to that in France and Germany – despite the fact that some aspects of the agreement do not align with the supposed priorities of voters in the frugal states.

There are subtle differences within the frugal group on the emotional front. The recovery deal appears to have gone down relatively poorly in Finland, Austria, and the Netherlands. In these countries, between 42 per cent and 50 per cent of voters say that the recovery deal primarily inspires anger, frustration, or worry in them, while less than one-third emphasise optimism, relief, or enthusiasm.

Voters in Sweden and Denmark, by contrast, express positive and negative feelings about the agreement in roughly equal measure. This may be partly because, as non-members of the eurozone, the two countries are less concerned about the systemic effects of the crisis on the common currency. Far fewer voters in Sweden and Denmark feel ‘worried’ about the recovery deal than do those in Finland, the Netherlands, and Austria – where this is the most common sentiment.

Moreover, Sweden and Denmark are traditionally among the most optimistic societies in the EU – and, in the former country, many people tend to respond ‘don’t know’ in polls about Europe. These factors may also help explain their less negative reaction. However, Sweden and Denmark share the rest of the frugal states’ high level of frustration with the recovery deal relative to France, Germany, and Poland.

And, overall, there is a stark contrast between emotional reactions in the frugal states and those in Poland. While the former are net creditors to the EU budget, the latter has historically been among the greatest beneficiaries of European funds and is set to become the fourth-biggest recipient of the recovery grants (after Italy, Spain, and France). In Poland, more than half of respondents express positive feelings – mostly optimism – about the fund, while only 17 per cent express worry, frustration, or anger.

In the frugal states, there is a strong correlation between voters’ emotional reactions to the recovery deal and their political views – such as those on voting intention. Unsurprisingly, negative feelings about the deal predominate among supporters of the populist right (the Sweden Democrats, the Austrian Freedom Party, the Finns Party, the New Right, and the PVV). Anger is one of their main feelings about the deal, and the leading one among supporters of the Finns Party and the Sweden Democrats. But anger is far rarer among supporters of other parties in their countries.

Supporters of ruling parties tend to display the most positive feelings about the recovery deal – which is understandable, given that these parties played a role in negotiating the agreement. In this sense, however, it is all the more surprising that supporters of Rutte’s People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) and Kurz’s People’s Party (OVP) express more negative feelings about the deal than do their compatriots who favour other mainstream parties (such as the Greens and the left). Supporters of the VVD and the OVP express worry more than any other emotion in response to the agreement.

In comparison to angry and frustrated voters, worried voters are less concerned that the EU is spending too much on the recovery deal, and more appreciative of the deal’s positive effect on economic recovery in the EU. However, voters in all three categories have significant concerns about wasted expenditure.

The frugal states have not been swept up in negative feelings about the recovery package (even if media coverage across Europe in late summer 2020 might have suggested otherwise). This indicates that their citizens – like those of other member states – understand that the EU matters in dealing with global issues that affect their lives, such as trade, conflict, and counter-terrorism. So, although voters in frugal states wanted their national leaders to protect their country’s interests in the recovery fund negotiations, they would not have supported brinkmanship from them that risked collapse of the EU. One of the key challenges governments of the frugal states face is in continuing to protect European and national interests simultaneously.

Regrets, they have a few

This is not to say that voters in the frugal states have no regrets about the EU recovery deal. The 2020 budgetary negotiations were an ambiguous experience for them. The frugal states were largely successful in defending their rebates and pushing down the proportion of grants to loans in the recovery fund. However, their leaders were not hailed as heroes in the domestic press. Though the outcome of the negotiations addressed some of voters’ main concerns, the recovery deal was reported across the EU as a step forward in the integration process – a ‘Hamiltonian moment’. And the inclusion of a borrowing facility in the deal was in direct opposition to some of the frugal states’ objectives, as well as to their interpretation of EU treaties. In addition, the frugal states must recognise that they are unlikely to be as influential in EU negotiations over other matters as they were over the budget.

In light of this, one might expect voters in all the frugal countries to express a powerful sense of lost influence in the EU. This is clearly the case in Finland, Sweden, and Denmark. But, in the Netherlands and Austria, voters are split on whether the influence of their country in the EU has increased or decreased during the pandemic. As much as 37 per cent of respondents in Austria believe that their country’s influence grew. This is only just short of the proportion of Germans who hold this view (40 per cent). And it is markedly higher than the corresponding number in France (29 per cent), despite President Emmanuel Macron’s best efforts to challenge traditional French scepticism in the area.

If one assumes that Brexit played a vital role in making the frugal states feel less influential in the EU, then the Scandinavians appear to have coped less well with the situation than their Dutch and Austrian peers have. This may be because their geographic position provides them with fewer opportunities for coalition-building.

Usually, the prevailing view among supporters of ruling parties is that their country’s influence has risen. But – surprisingly – this is not the case in Denmark, where those who voted for the Social Democrats recognise the waning power of the country (perhaps due to a recent change of government). Nor is it the case in the Netherlands and Finland, where supporters of the VVP and the Social Democrats respectively are split on the issue.

In ECFR’s surveys, overall perceptions of national influence are usually skewed by the strongly negative attitudes of far-right voters. Yet no ruling party can feel comfortable if only its supporters see their country’s influence as having increased. In this sense, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Macron have good reason to be pleased with the result of the October survey. A generally positive view of national influence in the EU is evident among not just supporters of the ruling Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) and La République En Marche! respectively but also the other main pro-European forces in these countries: the Social Democratic Party and the Greens in Germany, and Les Républicains and the Greens in France. There is no similar dynamic in the frugal countries.

National influence and the recovery deal: Citizens’ feelings

Voters’ perceptions of changes in their country’s influence in the EU correlate with their feelings about the recovery deal. In all surveyed countries aside from Poland, differences in voters’ emotional reactions to the recovery deal correlate with differences in their sense of how their country’s influence in the EU is changing. Most of those who see their country’s influence as increasing express positive feelings about the agreement, especially optimism. And most of those who see their country’s influence as declining express negative feelings, particularly worry. Voters in frugal states who perceive a decline in their country’s influence tend to have negative feelings about the recovery deal. This is true of two-thirds of that group in Finland and 60 per cent in Austria. There is a marked sense of anger with the deal among citizens of Germany, Austria, and Finland who see their country’s influence as declining.

France stands slightly apart from the frugal states and Germany – as well as Poland – in being the only country in which voters’ strong sense of relief does not correlate with perceptions of an increase in national influence in the EU. This may be because the pandemic has hit France harder than the other countries in the survey, in both health and economic terms.

National influence and the recovery deal: Citizens’ opinions

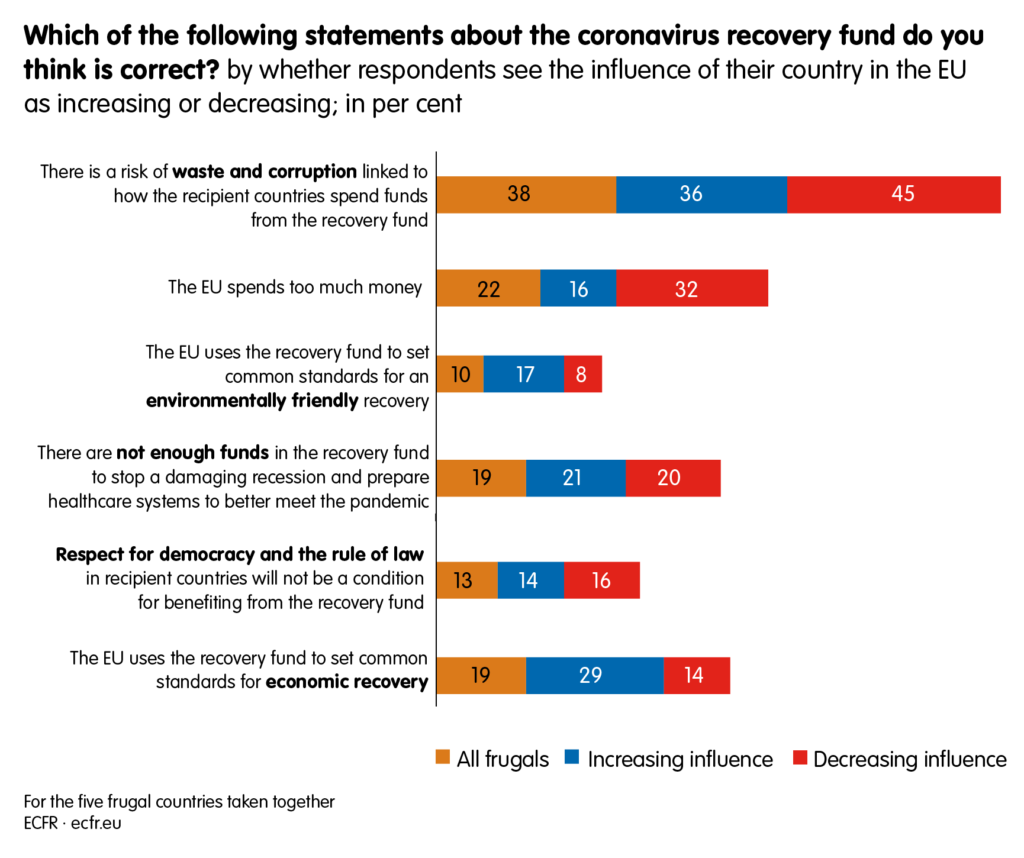

In all surveyed countries, voters’ perceptions of changes in their country’s influence correlate with their views about the recovery package. As discussed above, many of them are concerned about waste and corruption linked to recipient states’ use of the fund. The share of respondents who express this concern ranges from 30 per cent in Poland to 48 per cent in Austria.

There are significant differences between surveyed countries in the other concerns that voters express most often. In the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, and Germany, the second most common concern is that, with the recovery fund, the EU is spending too much money. This perception is also common in Austria, Finland, France, and Poland. But it is not as common as the view that there may be insufficient money in the recovery fund to stop a damaging recession and prepare healthcare systems to combat the pandemic.

This may point to a heightened sense of economic vulnerability in Austria, Finland, France, and Poland – with people in other surveyed countries believing that their economies are relatively resilient. However, the most striking finding of ECFR’s October survey is that, in the frugal states and Germany, the perception that the EU spends too much money is far less common than their reputations would suggest. Between 70 per cent and 80 per cent of voters in these countries do not express this view (these numbers are even higher for Poland and France). Despite their worries about waste and corruption linked to the recovery fund, most Europeans do not say that the EU should spend less.

To be sure, this does not apply to every voter. In all surveyed countries, respondents who perceive a decline in their country’s influence in the EU tend to be more concerned than others about waste and corruption – and about the EU spending too much. And this tendency is particularly marked in the frugal countries. In all five frugal states, the belief that the EU is spending too much is twice as common among voters who perceive a decline in their country’s influence as among those who perceive an increase in it (32 per cent to 16 per cent). The difference between the two groups is considerably smaller in France, Germany, and Poland.

The perception that the EU is spending too much is relatively common among supporters of far-right parties such as the New Right, the PVV, the Finns Party, the Austrian Freedom Party, and the Sweden Democrats. The share of voters who hold this view ranges from 30 per cent to more than 50 per cent across these parties. The perception is also common among supporters of Alternative for Germany, Poland’s Konfederacja, and France’s Rassemblement National. And it is shared by around one-quarter of supporters of centre-right parties such as the Moderate Party in Sweden, the CDU/CSU, the VVD, the National Coalition in Finland, and the OVP. On this, voters’ perceptions of EU spending correlate more with whether the party they support is on the right or left than whether it is in government. Overall, surprisingly few voters say that the EU is spending too much.

At the same time, those who see their country’s influence in the EU as increasing are more likely to believe that, through the recovery deal, the bloc will spark an economic recovery and a green transition. Again, this trend is stronger in the frugal countries than in France, Germany, or Poland. In the five frugal states collectively, the belief that the fund sets EU-wide standards for the economic recovery is twice as common among those who see their country’s influence increasing (29 per cent) as among those who think it is declining (14 per cent). The corresponding numbers for the environmental transition are 17 per cent and 8 per cent respectively. These perceptions are common among supporters of all ruling parties in the frugal countries, aside from the OVP.

Interestingly, in most surveyed countries, at least one-fifth of voters say that the recovery fund could be insufficient to address the crisis. Sweden and Denmark are the only outliers, at 12 per cent each. In the Netherlands and Poland, this perception is relatively common among voters who say that their country’s influence is increasing. Meanwhile, the reverse is true in Finland, where the view that the EU is spending too little money is among the most common answers among those who see the influence of their country as waning. In Germany, France, and Austria, between 21 per cent and 25 per cent of voters say that the EU does not have enough money to address the coronavirus crisis – but this view is equally common among those who believe their country’s influence is increasing and those who see it as declining.

All this may point to a link between people’s perception of their country’s position in the EU and whether they think that, with the recovery deal, the EU is either spending too much money or doing the right thing to spur an economic recovery and a green transition. In general, the recovery package receives a more positive reception from those who believe that the influence of their country is increasing (perhaps because this belief boosts their confidence in the deal). In contrast, those who believe that the influence of their country is waning are most likely to believe that the EU is spending too much.

Concerns about waste and corruption, and about a lack of recovery funds, are common among voters irrespective of the changes they perceive in their country’s influence in the EU. As the most widespread concerns across all eight surveyed countries, these areas constitute a promising basis for policy that could win support from not just different parts of the electorate but also different EU member states.

National influence and the recovery deal: The EU’s contributions

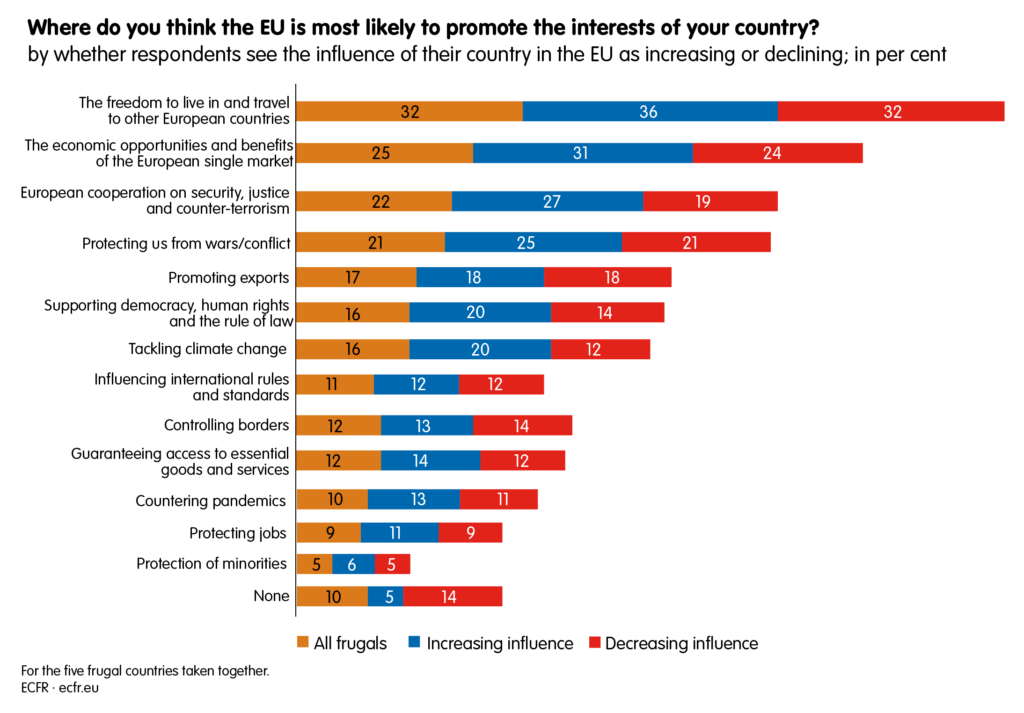

In frugal states, voters’ perceptions of changes in their country’s influence also correlate with their views on where the EU makes the greatest contribution to promoting their national interests. However, the correlation is not as strong as that with feelings and opinions about the recovery deal.

Overall, there is a greater appreciation of the EU’s role among those who believe their country’s influence is rising than among other voters. This is true in most policy areas covered by ECFR’s October survey. Collectively, citizens of Austria, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, and Sweden who think their country’s influence is growing tend to be more appreciative than others of the economic opportunities and benefits of the single market (34 per cent), as well as of European cooperation on security, justice, and counter-terrorism (29 per cent). They are, in comparison to those who see their country’s influence in the EU as waning, almost twice as likely to see the fight against climate change – along with support for democracy, human rights, and the rule of law – as an area in which the EU makes an important contribution. In contrast, in frugal states, just 4 per cent of voters who perceive an increase in their country’s influence in the EU say that the bloc does not promote their national interests in any area. Among those who believe their country’s influence is declining, this figure is 14 per cent.

More importantly, however, voters who believe their country’s influence is declining are still broadly enthusiastic about the EU – for a variety of reasons. In the five frugal countries, 30 per cent of these voters appreciate the freedom to live in and travel to other member states. One in four recognises the economic opportunities and benefits of the single market. And at least 20 per cent believe that the EU makes a valuable contribution to European cooperation on justice, security, and counter-terrorism; the promotion of exports; and protecting them from war and conflict.

In the Netherlands, Sweden, and Austria, there is a greater appreciation for the EU’s role in promoting exports among voters who believe their country’s influence in the EU is declining than among those who believe it is increasing. And, as discussed above, even supporters of right-wing populist parties appreciate the EU’s role in protecting their country’s interests in several policy areas.

This suggests that there is a strong attachment to the EU even among these voters in the frugal states who either perceive a decline in their country’s influence, are voting for Eurosceptic parties, or both. Leaders in these countries should not misread such behaviour as a sign that they would prefer to leave the EU altogether, as the British chose to do. But the fact that so many voters in frugal states feel bad about the recovery deal – and that, in all the frugal countries, more than one-third of voters think their country is losing influence in the bloc – points to another danger for these countries’ sense of ownership of the European project. It will be hard to convince voters in frugal states that their countries are still influential – and that EU membership is worth the price – if national narratives about the bloc continue to focus on narrowly defined economic interests.

Conclusion

There is little doubt that voters in the frugal states regard the recovery package as far from ideal. But ECFR’s survey data indicate that they understand the need for compromise in an organisation of 27 states, and that the benefits of EU membership outweigh its costs. Indeed, their appreciation of the EU’s contribution in some policy areas – from strengthening the single market and the rule of law, to cooperation on security and terrorism, to protecting their countries from war and conflict – suggests that they have an appetite for more Europe. EU institutions would do well to include these areas on their policy agenda and in their communication in the coming years. This could prove especially necessary in the event of longer-term restrictions on free movement across the EU designed to handle the pandemic, which would effectively take away one of the benefits of EU membership that – as ECFR’s data show – voters in the frugal countries (and other member states) prize most highly.

For political leaders in Austria, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, and Sweden, the ‘frugal’ label is no longer tactically useful now that the recovery fund has been finalised. Public sentiment presents them with an opportunity to reposition themselves as an engine of EU transformation. They can do so by focusing on how member states spend EU funds, and by building the kind of EU that their voters want to see.

To become the transformative five, the frugal states first need to convince voters at home that they are influential in EU decision-making and that this process produces outcomes that are in the national interest. One area in which these voters have a strong appetite for progress at the European level is in tackling financial waste and corruption, particularly in the use of EU funds. Most governments in frugal states are already part of the ‘friends of the rule of law’ grouping within the European Council. They should publicise this form of engagement in the national media; be vocal about the EU’s use of its mechanisms to address violations of the rule of law (such as those in Hungary, Poland, and Bulgaria); emphasise the importance of judicial independence in relation to systemic threats to democracy; and be particularly vigilant on the disbursement of EU funds in countries where there are breaches of the rule of law.

All these approaches would help them reassert their influence in the EU. They could also be politically beneficial in their national contexts, given that corruption and the rule of law are issues on which the EU can actually make a difference and, in doing so, take the power out of the arguments of European populists. These approaches could provide a ‘win’ in EU politics for the leaders of the frugal states, who could tell their voters that their main concern had been addressed.

For the frugal states, the springboard for such efforts could be the November agreement between the European Council and the European Parliament to link payments from the recovery fund and the multiannual budget to the rule of law. But they should also build on this compromise. For example, they could try to reinforce the authority of the European Court of Justice as the ultimate arbiter of EU law. One possible way to protect the rule of law in the EU would be to condition any payment from the bloc’s budget on judicial independence in member states. Including such a provision – with clear reference to the breach of Article 19 of the Treaty on European Union – could, in the future, become a cornerstone of a possible amendment of the rule of law mechanism. Some of the frugal countries could also exert pressure on Poland and Hungary to join the European Public Prosecutor’s Office – although their efforts might be more fruitful if Denmark and Sweden also joined it, as they are currently the only other EU27 members (apart from Ireland) that have not done so yet.

Secondly, the governments of the frugal states should continue to assert themselves in the Council – and, once the Council has made a decision, they should take collective responsibility for it. Given the fine balance in domestic public opinion on the relationship with the EU, they cannot afford to fall into the British trap of blaming Brussels for everything that is hard to swallow at home. This will simply reinforce domestic concerns about their country’s declining influence and scepticism about whether there is a place for it in today’s EU. That said, they should also be careful not to give voters the impression that they can profoundly change the EU – because they cannot. Change is painfully slow in the EU, and leaders of the frugal countries should carefully explain to their domestic audience that this is the nature of the beast.

This leads to the third recommendation for the political leaders of what could become the transformative states. They need to tell a compelling story about how national and European interests align. As ECFR’s data indicate, in these countries, there seems to be a gap between governments and citizens on the appropriate level of frugality. This suggests that some political leaders may have reasons other than democratic pressure for pursuing a hard line on budgetary issues.

Some of the frugal states are already relaxing their long-held positions in response to geopolitical shifts. For example, the Netherlands has revisited its laissez-faire stance on Chinese investment in Europe, and Sweden is pushing forward with ambitious investments in defence. However, frugal states’ narratives about Europe have remained staunchly market-focused, in keeping with stereotypes about voters’ preferences.

Yet these voters seem to want their governments to move away from the fight over higher spending, and to focus on financial waste and corruption. Leaders of frugal governments could, at the very least, discuss this issue with their voters in a more sophisticated way: specifying how much corruption there really is in the EU, which countries suffer from it, who is responsible for it, and what can be done about the problem. The yearly reports of the European Court of Auditors rarely receive public attention in the frugal countries. As a result, some voters might get the impression that the EU maintains a giant scheme of waste and corruption – for which one can blame the ‘Eurocrats’ in Brussels but do little else about.

Given that voters in the frugal states have a strong attachment to the economic aspects of the EU, leaders in these countries should also engage citizens in a narrative about the close relationship between the rule of law, corruption, and the vitality of the single market. The unprecedented problems with the rule of law and corruption in some member states have a bearing on the economic prospects of the frugal states, as they concern the functioning of the single market more broadly. At the same time, problems with the rule of law in some member states may erode the EU’s credibility in markets – which is a crucial issue now that the EU is starting to borrow on a significant scale to pay for the recovery.

The climate agenda also forms part of this picture. Few governments in frugal countries have made a sufficiently strong case to their domestic audience on the need for climate action on the EU level. Voters in these states generally associate international cooperation on climate policy with the United Nations. And governments in frugal states have willingly presented themselves as global – rather than European – leaders in the area. But Brussels has rising ambitions on carbon neutrality and emphasises green investment in the context of both the recovery fund and the upcoming long-term EU budget: taken together, 30 per cent of the fund and the budget have been ring-fenced for climate-related spending. This should help governments in the frugal states make the case at the European Council that climate action should be a key part of the EU’s agenda. These governments have plenty of scope to rebrand the new budget and the recovery fund around efforts to tackle climate change – and their high standards in this area could prove essential to avoiding the risks of ‘greenwashing’ (funding projects that seem valuable to the green transition but that do not measure up on closer inspection).

As the data from ECFR’s October survey show, the frugal states’ partners in the EU need to understand the extent of the compromise on the recovery fund that these countries feel they have made. They also need to recognise that the frugal states may believe that the balance of power in the EU has tipped against them, which could cause them to disengage from EU decision-making. As the EU approaches the final decisions on its next long-term budget, its own resources to pay for the recovery fund, and the workings of rule of law conditionality, proponents of greater EU spending and opponents of rule of law mechanisms alike would do well to remember the concessions the other side has made.

Methodology

This paper is based on a public opinion poll in eight EU countries carried out for ECFR by Datapraxis and Dynata in late October 2020.

This was an online survey conducted in Austria (n = 1,004), Denmark (n = 997), Finland (n = 1,000), France (n = 1,000), Germany (n = 1,023), Netherlands (n = 1,000), Poland (n = 1,000), and Sweden (n = 1,000). The results are politically and nationally representative samples.

The exact dates of polling were: Austria (16-26 October), Denmark (16-30 October), Finland (16-25 October), France (16-21 October), Germany (16-21 October), Poland (16-25 October), the Netherlands (16-30 October), and Sweden (16-23 October).

Acknowledgments

This report draws extensively on conversations with, and insights from, many individuals across the wider ECFR family.

In particular, the authors would like to thank Ivan Krastev for his concept of the ‘transformative five’, and Caroline de Gruyter, Ismaël Emelien, Catharina Sorensen, and Daniel Sachs for their valuable comments on earlier drafts. ECFR’s Unlock team – including Mark Leonard, Susanne Baumann, Swantje Green, Andreas Bock, and Jenny Soderstrom – helped us shape the argument, while Piotr Buras had some very useful ideas on what else could be done on the EU’s rule of law issues. Chris Raggett’s editing made the narrative much clearer and livelier compared to the original draft. Philipp Dreyer was, as always, a huge support on data analysis. We would also like to thank the team at Datapraxis for their ongoing collaboration with us in developing and analysing the pan-European surveys, and for carrying out the fieldwork for this survey with Dynata. We are grateful to Think Tank EUROPA for funding the research on Denmark.

Despite all these many and varied forms of input, any errors in the report remain the authors’ own.

About the authors

Susi Dennison is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations and director of ECFR’s European Power programme. In this role, she explores issues relating to strategy, cohesion, and politics to achieve a collective EU foreign and security policy. She led ECFR’s European Foreign Policy Scorecard project for five years and, since the beginning of 2019, she has overseen research for ECFR’s Unlock project. Her most recent publications include “Together in trauma: Europeans and the world after covid-19” (June 2020) and “Crisis presidency: How Portuguese leadership can guide the EU into the post-covid era” (October 2020).

Pawel Zerka is a policy fellow with the European Power programme, based in the European Council on Foreign Relations’ Paris office. He is an economist and political scientist with expertise in EU affairs and European public opinion. He is also a member of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe project, supported by Stiftung Mercator, which crafts policy strategies based on data and dialogue. His most recent papers include “Together in trauma: Europeans and the world after covid-19” (June 2020) and “In sickness and in health: European cooperation during the coronavirus crisis” (July 2020).

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.