In sickness and in health: European cooperation during the coronavirus crisis

Summary

- ECFR research into how EU member states and institutions worked together – or failed to – at the height of covid-19 confirms Germany was the bloc’s undisputed crisis leader.

- Germany made a shaky start in showing solidarity on the pandemic, but regained other member states’ trust on the health and economy fronts. The Netherlands, however, paid a reputational price as the leading ‘frugal’ state opposing greater financial burden-sharing.

- EU institutions won few plaudits but policymakers still look to it for post-crisis economic leadership.

- France emerged at the head of a strengthened ‘southern’ grouping of member states, while the Visegrad platform was invisible during this crisis.

- It will fall to Germany and France to close the north-south divide, building coalitions on major policies. But they should not forget that closing the east-west divide remains an important goal.

Introduction

This strange summer will start late. Europe’s policymakers cannot yet hit ‘out of office’ and close their laptops – they still need to attend at least one more European Union summit on the post-covid-19 recovery fund. As they prepare, they should take a long breath and reflect on what has worked well, and what has not, over the past couple of months. This will help them understand what they are in for.

They already know that the coronavirus crisis has been a moment of profound trauma for European citizens, as the European Council on Foreign Relations documents in a recent report drawing on a specially commissioned public opinion survey in nine EU countries. However, as argued in another ECFR report, the crisis has not led to either a populist revival or a re-evaluation of European federalism. As the pandemic spread, European solidarity was sometimes late in arriving, or turned out to be mere self-interest in disguise. But, usually, European solidarity was a reality, and often strongly so: by early July, ECFR’s European Solidarity Tracker had recorded over 400 instances of solidarity between EU member states. Still, are policy professionals satisfied with the role they have played – on either the national or European level?

This paper analyses the impact of the coronavirus crisis on cooperation patterns among governments of the 27 EU member states, and on the roles that policy professionals across the continent expect EU institutions and national capitals to play in such a situation.

Beginning in March 2020, European cooperation – as well as the relevance of EU institutions – underwent a series of crash tests: firstly, on coordinating the immediate response to the pandemic; later, on providing immediate relief to member states disproportionately hit by the virus; and, finally, on financial burden-sharing to tackle the economic consequences of covid-19. But was this just an interlude, or – at least in some respects – a turning point for the way the EU works?

ECFR’s Coalition Explorer would normally provide the answers to such questions. ECFR has published the explorer every two years since 2016, basing it on a survey of several hundred European policy professionals. But ECFR conducted this year’s survey in March and April 2020, when no one was yet able to predict the full scale of the covid-19 crisis. The data collected at that time show what has changed since 2018, and this is covered in a forthcoming ECFR paper. But that data did not provide a glimpse into what happened as the pandemic reached its height. Therefore, in order to better understand the effects of the crisis on cooperation patterns in the EU, ECFR carried out an additional study in May 2020. This survey comprised a short set of questions related specifically to the pandemic and focusing exclusively on the way European governments worked with one another during the crisis. Altogether, almost 750 policy professionals participated in this supplemental survey.

In time, the full story will be told of how well Europeans cooperated during the coronavirus crisis. What has emerged so far is a collection of micro-stories. A sense of what more general patterns may yet emerge remains only tentative.

Covid-19 was not a moment when either the EU’s institutional leadership proved superior to intergovernmental cooperation, or the other way round. Instead, the pandemic exposed just how dependent EU member states and institutions are on each other’s effectiveness. These institutions’ image suffers when member states do not cooperate with one another; in this sense, the crisis serves as a reminder that fostering such cooperation is what both policy professionals and citizens value the most about EU institutions.

Another finding is that Germany’s leadership has been strengthened throughout the crisis, but that this has created an uncomfortable situation in which Berlin is burdened with excessive expectations from other capitals – hopes and demands that no country could ever fulfil alone. France is a necessary partner for Germany to move things in the EU forward. And, during this crisis, it has played a constructive role as a leader of, and link to, the EU’s south. Meanwhile, the Netherlands has lost much of its charm due to its staunch opposition to increased financial burden-sharing, while aspirational ‘Big Five’ player Poland has effectively been missing in action. The south has been hit hardest by the crisis; the north came under the greatest pressure to help others; and much of the east was surprisingly invisible. Living through, and governing during, the pandemic has been both a collective and a highly individualised experience. The crisis has reshaped pre-existing disagreements within the EU, which will take on heightened importance in negotiations over the bloc’s next long-term budget and its extraordinary recovery fund.

Disappointment revisited

Disappointment with the EU is high among European citizens. ECFR’s nine-country survey carried out in the last week of April revealed that few voters believed the EU had been their country’s most important ally in dealing with the crisis. Out of the seven member states in which ECFR asked a question on this topic, Poland was the only one where more than one in ten respondents said the EU was the most important in the crisis. But even in Poland, as in other surveyed member states, the prevailing view was that countries had had to manage the situation on their own. In every surveyed country, at least one-third of respondents said that the EU had not lived up to its responsibilities; and in no country were there more people who disagreed with this view than agreed with it. Across the nine countries, one-third said that their opinion of the EU institutions has worsened, while one in ten said that they viewed EU institutions in a more positive light. Most damningly of all, at least four in ten people everywhere – and six in ten in France – said that the EU had been irrelevant during the pandemic.

If the public’s view is clear, what do policy professionals, working more or less full time on the detail of such questions, make of the same issues? The nearly 750 individuals interviewed among this group for the Coalition Explorer coronavirus special hold a more nuanced view on the question of how well EU institutions performed at the height of the crisis. They acknowledge both the strengths and weaknesses apparent in recent European cooperation, as well as the point that EU institutions have often been constrained by the fact that member states have often chosen not to bestow certain competences on them.

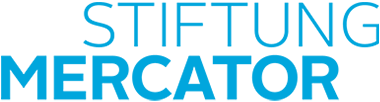

First of all, policy professionals signal their strong disappointment in the strength of cooperation between member states during the pandemic. Sixty per cent of the total say there was less cooperation than they would have expected; and these numbers are even higher in Spain and Italy, perhaps because these were the two member states hit hardest in health and economic terms. The numbers of those disappointed in the strength of cooperation displayed are also above average in the members of the Visegrad group (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia), and in Croatia, Estonia, Malta, Romania, and Denmark. In only five countries – Germany, Portugal, Ireland, Latvia, and Cyprus – do at least half of respondents say there has been about as much cooperation as expected; there, just one-third of respondents believe that there was too little cooperation.

How to explain these variations? Much is contingent on how different countries experienced the pandemic. For instance, Portugal felt the worst effects of covid-19 somewhat later than other countries did, by which time member states had already begun to cooperate with each other more proactively – in contrast to, say, early moves to close borders and requisition medical equipment. The European Commission too had already become more closely involved in ensuring solidarity across borders by that point. Germany was in a very different situation to Portugal, but its broadly successful domestic management of both health and economic issues likely contributed to the more positive assessments issued by its policy professionals in ECFR’s survey.

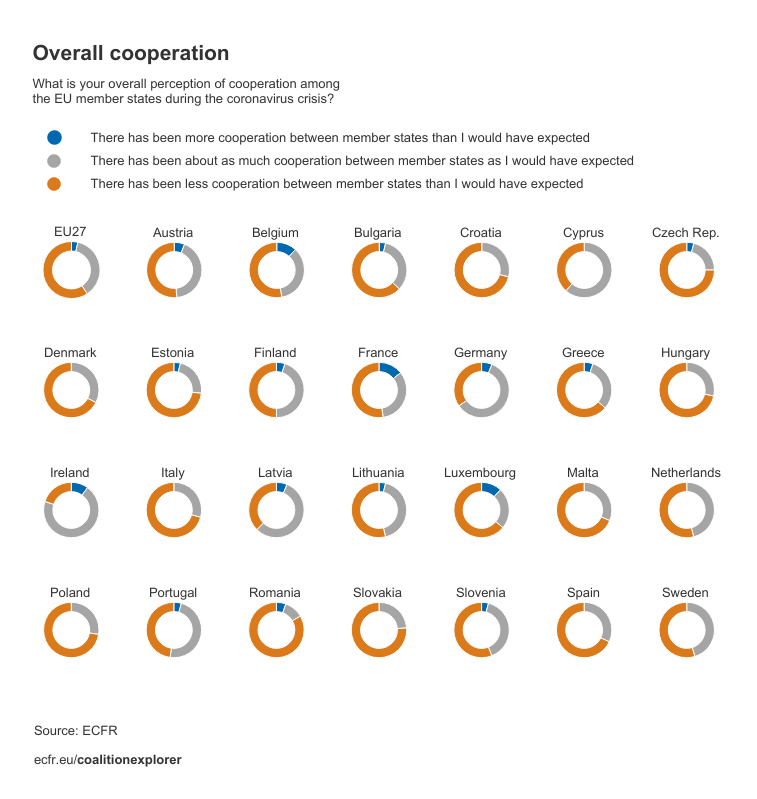

Two-thirds of policy specialists across the EU27 say that the European Commission did what it could on the health front. However, this still leaves one-third who say that it underperformed. Almost no one says that it excelled in this area.

Respondents’ assessment of the Commission’s performance is more positive on the economic recovery front. Here, almost half of respondents across the EU27 agree that the European Commission did what it should – and three in ten believe that it excelled in playing a constructive role. Fully half of respondents in Latvia, Slovakia, and Belgium say they were impressed by the Commission’s performance; and more than one-third in Germany, Estonia, Finland, Netherlands, and Romania agree. In contrast, views are most negative in Greece and Portugal, which is perhaps a hangover from eurozone crisis. Interestingly, three-quarters of responses to the survey were collected before 18 May 2020, which was the date when Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron announced their joint proposal for the €500 billion European recovery fund. As Europeans’ generally approving view of the Commission’s role in the economic arena predates discussions about the recovery fund, they likely have an even more positive perception of it now.

However, where the European Commission clearly fell short of EU27 policy professionals’ expectations is on the coordination of cross-border travel. Almost half of this group believed that the Commission underperformed in managing the issue – an assessment that is particularly prevalent in Estonia, Romania, Luxembourg, and Austria. All these countries suffered from the uncoordinated introduction of border controls by other member states. For example, Estonian citizens found themselves trapped at the Polish-German border in March, unable to transit to their country. Luxembourg took issue with Germany’s unilateral decision to close its borders without consulting its neighbours – although relations have improved since, with the foreign ministers of the two countries, Heiko Maas and Jean Asselborn, jointly celebrating the reopening of the border at the Schengen bridge itself in June.

Last but not least, it was on the much more abstract question of ‘overall leadership’ where the European Commission appears to have generated the most disappointment. More than half of respondents across the EU27 say it underperformed in the face of this challenge. Almost no country’s policymaking community agreed that the Commission had exceeded expectations, with Portugal and Belgium the only exceptions to this. Assessments are particularly severe in France, Spain, Hungary, and Luxembourg, although likely for different reasons in each of these countries, such as the scale of the health crisis in Spain and France, and the general anti-Brussels feeling among Hungarian policy professionals.

Respondents’ views of how successfully member states cooperated with one another are astonishingly similar to their views about how well the European Commission performed. At the level of individual respondents (putting aside which country they are from), two-thirds of those who are sceptical about cooperation between member states also have a negative view of the Commission’s leadership, and vice versa. This could partly reflect a difference in outlook between individuals who always see a glass half full where others see it as half empty. But it could also be down to expectations that the European Commission should provide a framework for facilitating cooperation between member states, and that it failed in this.

In particular, on issues that exist in a grey area between national- and EU-level competences – such as cross-border travel – it is impossible to achieve much without both a coordinating role for Brussels and a cooperative approach from the capitals. This was clearly lacking in the early stages of the crisis, which would explain EU27 policy professionals’ harsh assessments of cooperation between member states and of the European Commission’s leadership. In contrast, it might well be that policymakers are much less critical of the role that Brussels played on public health because they view this as a national matter and not the direct responsibility of the Commission. On the economic front, meanwhile, respondents’ expectations vis-à-vis Brussels are probably higher but, in this case, they also rate the European Commission’s performance much better. And with good reason: according to ECFR’s European Solidarity Tracker, by early July, the EU institutions were responsible for around 250 instances of economic solidarity. These included, among other things, the repurposing of structural funds, a temporary loosening of state-aid rules, monetary policy measures adopted by the European Central Bank, and new funding provided for medical research.

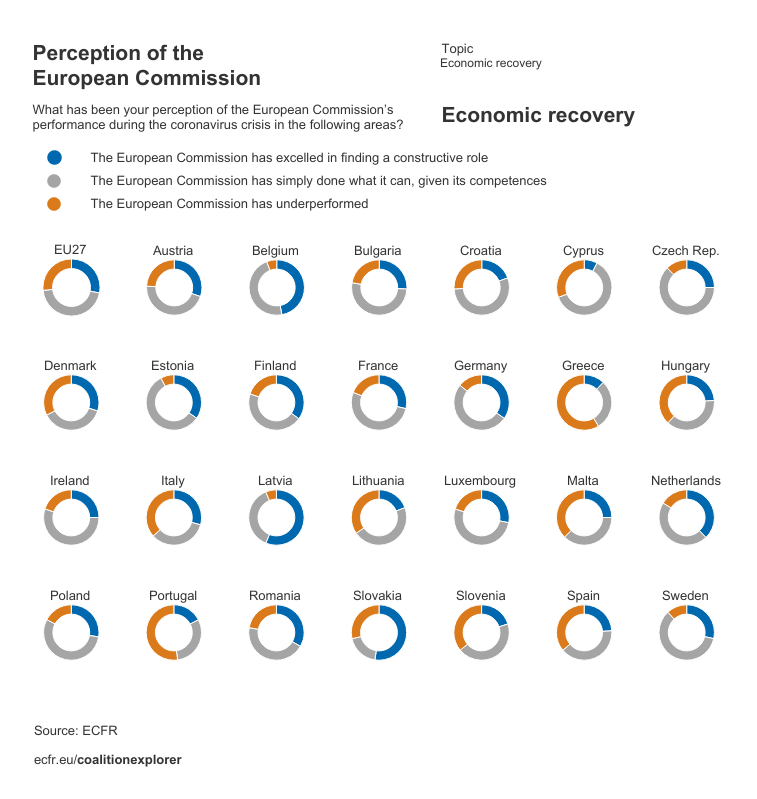

Interestingly, while a strengthened mandate for the EU on health policy is hardly a given, EU27 policy professionals appear to believe that such an initiative would likely win the support of their national governments. Across all countries, 30 per cent say that their governments would support it strongly, and 45 per cent believe they would support it in some form. Three-quarters of German respondents are confident of their government’s support for a stronger mandate for the EU on public health policy. This appears to indicate a major shift: Berlin has long been among the most reluctant capitals on this front.

There are only three exceptions to this last point, all of them members of the Visegrad group: Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic. A majority of respondents in these countries believe that their governments would oppose a stronger mandate for the EU on public health policy. But the devil is in the detail. While these governments are sensitive about the idea of sharing their national competences, the prospect of new EU funds for the modernisation of their health sectors could change their minds. And, interestingly, Czechs aside, policy professionals’ reservations are not reflected in public opinion: two-thirds of Hungarian and Polish voters say that the EU should have more competences to deal with crises such as the coronavirus pandemic, according to Eurobarometer.

Given that the world is probably only halfway through the crisis, perceptions of the European Commission’s role (and of cooperation between member states) could yet change, perhaps dramatically. In particular, the results of ongoing negotiations over the recovery fund may have a strong bearing on where opinion finally settles. And here one may yet need to reverse the logic observed above: Brussels’s image could improve if member states reach an agreement that satisfies all sides; but it could also deteriorate if European countries fail to clinch a deal that demonstrates their unity and solidarity. From the perspective of policy professionals, it is precisely in critical situations such as this where they expect the EU to prove its real value as a facilitator of cooperation between member states.

All eyes on Germany

If any country has taken the initiative at this critical moment, it has been Germany – with hardly any other government coming close in terms of activity, visibility, and followership among other member states.

The findings of ECFR’s Coalition Explorer survey conducted in March and April this year confirmed Germany’s unique position in Europe. Among the other 26 member states, respondents to that survey were near-unanimous in naming Germany as their country’s most influential partner on EU policy. They also collectively confirmed that Germany is the country they contact most if their government wants to pursue a particular issue – and, indeed, that Germany is the most responsive member state when contacted. Respondents tend to view Germany as a country that shares many interests with lots of other EU member states. The only novelty this year, in comparison to previous editions of the Coalition Explorer, is that France came not far behind Germany on overall influence – although still relatively few respondents agree that France shares similar interests with other countries.

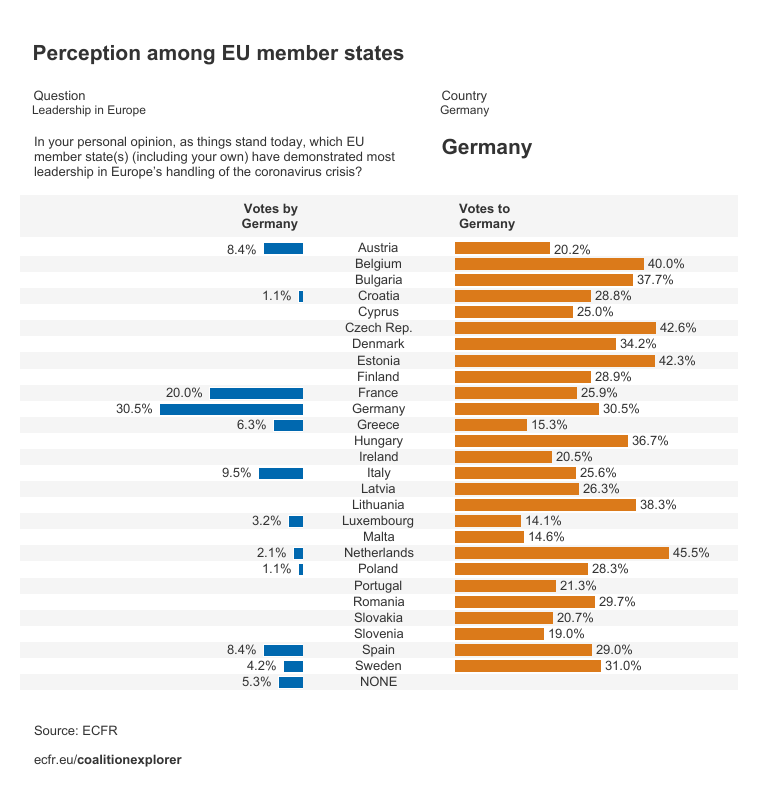

Meanwhile, Germany achieved an even greater lead in ECFR’s special survey on cooperation. Fortuitously for Berlin, this coincides with the start of its EU presidency. On who they consider to have demonstrated the most leadership in the EU’s handling of the crisis, one-quarter of votes from policy professionals across the EU27 went to Germany; France came second, but with half as many votes. No other member state scored well on this question. Greece and Malta aside, at least half of respondents from each country (and almost all of them in the Czech Republic, Estonia, and Hungary) say that Germany demonstrated the most leadership during the crisis. Germany is also the only country whose self-perception is in line with its image in other member states; as a matter of comparison, several others (especially France, Italy, and Austria) tend to overestimate their leadership quite a bit, with fewer people thinking as highly of these countries as they do of themselves.

Respondents also see Germany as the most helpful country during the crisis on issues of public health (20 per cent) and the economic recovery (19 per cent). That said, across the EU27, the most frequently expressed view is that no country has demonstrated sufficient leadership on these fronts (27 per cent and 34 per cent respectively).

Appreciation for Germany’s leading role on public health is strongest among policy professionals from the Netherlands, France, Ireland, and Italy, with at least three-quarters of respondents in each of these four countries naming Germany as the leader. Germany was rarely mentioned as the most disappointing partner on public health; only in Luxembourg and Greece do one-third of respondents express dissatisfaction with German leadership in the area. In Greece’s case, this is nothing new: ECFR’s 2020 Coalition Explorer research (based on a survey from March and April this year) finds that policy professionals from Greece were more likely than any other national group to name Germany as the country that had disappointed them most over the previous two years. This looks like an unhealed wound dating back to the eurozone crisis.

Germany’s reputation for leadership on the coming economic recovery presents a more nuanced picture than that on health. Here, its leadership receives the most praise from the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Finland, France, and Ireland – and even ‘frugal’ Austria and the Netherlands (at least four in ten respondents in each of these eight countries rated Germany positively). At the same time, however, Germany is sometimes seen as a disappointing partner on the economic front, especially in Greece and Malta, but also in Italy and France (at least one-third of respondents in each of these four countries say so).

All in all, it looks as if Berlin’s initial missteps – such as blocking medical assistance to Italy in March 2020 (as France also did) – were quickly forgotten at the policymaker level across the EU27. Subsequent actions by the German government – such as successfully managing the pandemic in Germany and demonstrating a wider sense of responsibility on the EU’s economic response – have earned it widespread recognition as a leader. Polling data suggest that the public perception of European cooperation (and of Germany) was likely set in stone in the early days of the crisis and never really recovered – or, at best, is recovering with a time-lag: the Italian public’s trust in the EU now appears to be recovering.

As most answers to ECFR’s survey of policy professionals were collected before the launch of the European recovery fund by Merkel and Macron, it is likely that assessments of Berlin (and of Paris) would be even more glowing now – although they may also yet become more geographically differentiated. Berlin’s economic initiatives might currently elicit more admiration in France and Italy. But the spending implications of the recovery fund are such that a larger share of policy professionals in the frugal Netherlands, Austria, Sweden, Denmark, or Finland could yet express their disappointment, rather than satisfaction, with the new measures.

No one country could fulfil the many expectations that member states have of Germany. Merkel is under intense pressure to prove that Germany can lead the EU from the centre and reconcile the diverging needs and interests of various member states. As Germany takes over the EU’s presidency, it will find itself under even greater scrutiny than usual. However, ECFR’s recent public opinion survey of nine EU countries revealed that Germany’s position at the heart of the EU project looks precarious. The poll showed that half of the German public believe their country needs no help from anyone in the economic recovery from the coronavirus crisis. This was the highest number polled among the nine member states in the survey. Only 43 per cent of the German public expressed support for greater financial burden-sharing in Europe – more than in Sweden and Denmark, but less than anywhere else (Austria and the Netherlands were not polled).

As a consequence, if she were to push for an ambitious European solidarity package, Merkel would need to challenge prevailing sentiment in her own country. Of course, the chancellor could well prove ready to do so, as she has demonstrated on a number of occasions: from her decision to renounce nuclear energy after the Fukushima disaster; to her “Wir schaffen das” (“We can do this”) response to the refugee crisis; to the current recovery fund, which has already placed her country outside the group of the EU’s ‘frugals’. However, Berlin needs to be able to count on the EU’s institutional leadership to avoid becoming an easy target at home, and to maintain smooth bilateral relations with all Germany’s neighbours. It also needs Paris’s support to manage expectations in southern European countries; and would benefit from pragmatism and goodwill from member states such as Italy and Spain.

German policy professionals in ECFR’s survey already recognise the south’s activism: half of them point to France as the country that has demonstrated the most leadership in Europe’s handling of the crisis; one-quarter point to Italy and a one-fifth to Spain. But one-third also see Italy as the most disappointing country on economic recovery. And, in contrast to the high levels of disapproval directed towards the Netherlands by other member states, just one-tenth of German policy professionals believe the country to be disappointing on the economic front – suggesting that they might tacitly agree with Dutch opposition to financial burden-sharing. German policymakers rate their own government highly, with three-quarters agreeing that their country demonstrated the most leadership in Europe’s handling of the crisis. Some people in Berlin might believe their role ends there; if more is to be done, then other member states would also need to become more engaged.

Highs and lows of the lowlands

If the coronavirus crisis has largely reconfirmed Germany’s pre-eminence within Europe, it has also had an impact on the reputations of other member states.

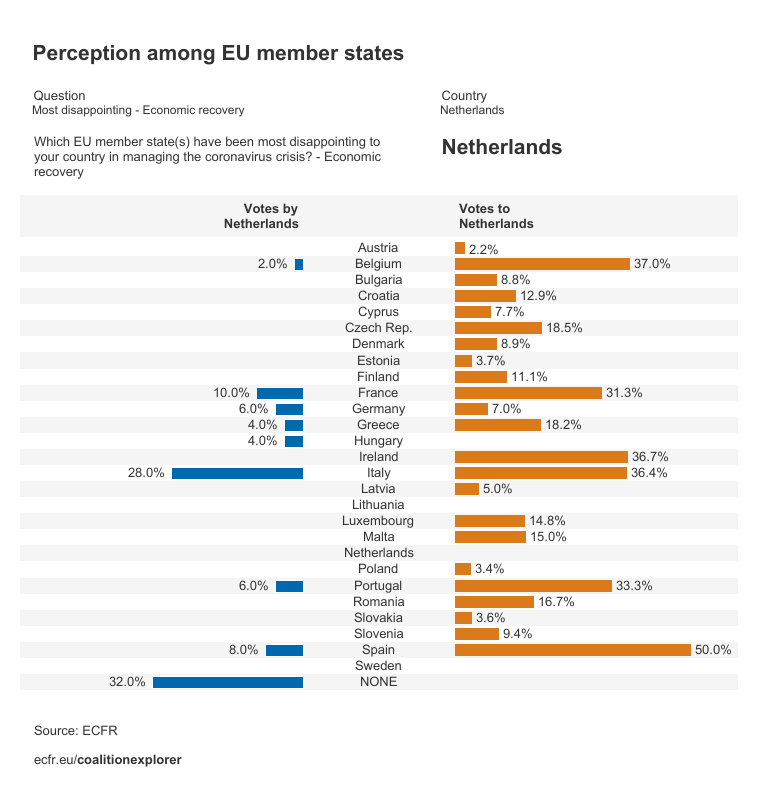

The Netherlands is a case in point. This year’s Coalition Explorer shows that, before the coronavirus crisis, member states considered the Netherlands to be the third-most-important player in the EU27, behind only Germany and France. In March and April 2020, more than half of policy professionals participating in the survey named the Netherlands as one of the countries that exerts the most influence on EU policy. Italy and Spain – two other member states with a GDP larger than that of the Netherlands – ranked lower, as did Poland and Romania, which have larger populations than the Netherlands. While it was already influential, as earlier editions of the Coalition Explorer show, the Netherlands has grown in prominence since Brexit, partly filling the gap left by the United Kingdom. However, covid-19 may come to be a moment when the Netherlands lost much of its charm, with potentially negative effects on its coalition potential in the EU.

Details of the EU agreement on the next Multiannual Financial Framework, and of the recovery fund, are still under negotiation. But, as things stand today, the Netherlands is paying a disproportionately high price for the position adopted by the ‘frugals’ (which also includes Austria, Denmark, and Sweden). This group is reluctant to support greater financial burden-sharing in the EU in response to covid-19; or, at least, it either does not feel the urge to agree on the package, or has reservations about the use of grants (as opposed to loans) to support the struggling economies of the EU. When ECFR asked EU27 policy professionals who had disappointed their country the most in managing the economic recovery aspect of the crisis, the Netherlands came top, with 16 per cent of all answers, followed by Germany at 11 per cent. This poor result for the Dutch is mostly driven by strong criticism from southern countries such as Spain, Portugal, Italy, and France. Interestingly, the results suggest that these countries do not necessarily blame Germany – unlike Greece, Cyprus, and Malta, which perhaps do so partly as a reflex from the eurozone and refugee crises.

There is a particularly strong sense of mutual economic disappointment and blame between the Netherlands and Italy. No fewer than four in five Italian policy professionals participating in the survey pointed to the Netherlands as having let them down on the economic front, while just one in three said the same of Germany. In turn, four in ten Dutch respondents expressed their disappointment with Italy on the economic front, a higher share than that of any other national group. A qualitative analysis that formed part of ECFR’s public opinion polling this year revealed that disappointment with the Netherlands, as well as with Germany, was also very strong among Italian citizens, with people often describing these two countries as “selfish”.

The extent to which the Netherlands is perceived as the villain of the piece becomes even clearer when ECFR asks respondents what they think of the Dutch and German contributions to managing the economic recovery. As noted earlier, 19 per cent of votes from respondents across the EU27 went to Germany as the most helpful partner on this front; just 3 per cent of votes went to the Netherlands – and most of them from German and Swedish respondents. On balance, the EU27 are more grateful to Germany than they are disappointed by its position on the economic recovery. They think the opposite of the Netherlands.

Certainly, the Netherlands’ reputation was not improved by the words of Dutch finance minister Wopke Hoekstra at a video-conference with his peers at the end of March, even if he later apologised for them. He reportedly suggested that Brussels should investigate why some countries did not have enough fiscal space to weather the economic impact of the crisis. This raised immediate indignation among his southern colleagues, with the Portuguese prime minister, António Costa, describing Hoekstra’s comments as “repugnant”. But it is likely that the Netherlands receives so much criticism, and more so than other ‘frugals’, because member states expect much more leadership from it. From this perspective, covid-19 may be a reality check for the Netherlands’ position in Europe. The Dutch may have discovered how difficult it is to co-lead the EU without compromising on its frugal instincts and previous policy positions. At the same time, others may have realised that they cannot expect too much from the Dutch, at least not yet.

Close friends – and just neighbours

The covid-19 crisis has been an important moment for some regional groupings in the EU27 – but a non-event for others.

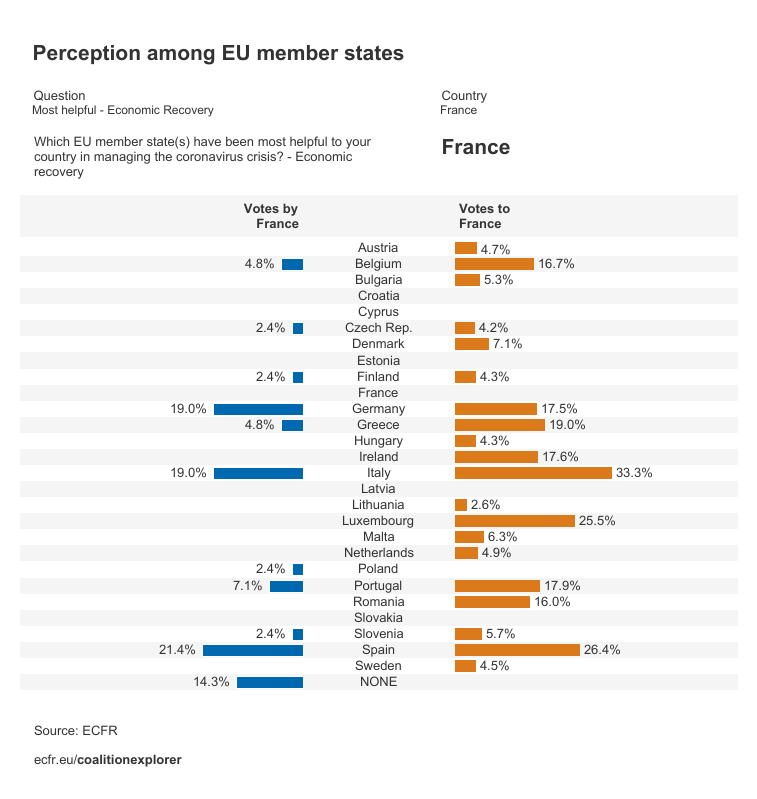

On the one hand, a number of southern countries – particularly Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal – have come together as allies in the face of a novel challenge. This is all the more noteworthy because not all the governments in question are from the same side of the political spectrum. Socialists are in power in Spain and Portugal, and the Democratic Party is a coalition partner in Italy; but, in France, Macron’s liberal party is in charge, while the anti-system Five Star Movement is in the driving seat in Italy. In general, the survey shows that policy professionals from each of these countries see the other three in this grouping as among the most helpful in managing the economic recovery. Respondents from Italy, Spain, and Portugal recognise that France has been a leader during the crisis. And respondents from these four countries rarely express disappointment with one another on either the economic recovery or health policy fronts, apart from criticism from one-quarter of Portuguese respondents directed at Italy’s and Spain’s performance in the health area.

The fact that Italy, Spain, and France have been among the hardest hit by covid-19, in terms of the number of cases and deaths related to the virus, may have eased the path to greater cooperation, as their experiences, perspectives, and priorities were closely aligned. This makes it even more remarkable that, together with Portugal, they have expanded an informal coalition of southern countries (which, in the past, used to take the form of the EU Med Group) to include several other member states, such as Belgium and Ireland. At the end of March, all these countries were among the nine co-signatories of the letter to the president of the European Council, Charles Michel, calling for the issuance of joint European debt to finance the fight against the coronavirus.

One legacy of the crisis could be a consolidation of the south. The crisis has also reaffirmed the position of France as the main advocate of the group. And it has allowed France to strengthen its bonds with other neighbours, such as Luxembourg, whose policy professionals profess an appreciation for France far beyond that which they have for any other country – including even Germany – on all accounts, from help on health and the economy, to overall leadership. Most importantly, Paris might have discovered the usefulness of reversing the sequence of its usual diplomatic method: it discussed the joint European debt idea with its southern partners first, and only later approached Berlin, which provided it with much greater leverage than it would have otherwise had. In this sense, the French policymaking community might feel vindicated in having drawn practical lessons from earlier disappointments with Germany (more than half of French respondents in the 2020 Coalition Explorer survey confirmed that they were disappointed in Germany as a coalition partner).

In a different corner of Europe, it also appears that the coronavirus crisis has strengthened the bonds among the three Baltic states, whose respondents cite each other as among the most helpful on both the health and the economic fronts. In fact, they hardly ever express any disappointment with one another on these two accounts. Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia have closely coordinated their policies in response to the coronavirus crisis, culminating in the opening of a ‘Baltic Bubble’ Schengen zone in mid-May.

On the other hand, covid-19 seems to have been a non-event for cooperation between members of the Visegrad group. The data show that Slovakian and Czech respondents acknowledge the assistance offered between the two countries in managing the public health aspect of the coronavirus crisis. But, this aside, the four central European countries rarely identify one another as being most helpful on either the economic or the health fronts, or on overall leadership in Europe’s handling of the coronavirus crisis. Even the link between Warsaw and Budapest is absent on covid-19, despite otherwise close political relations between the two capitals. In fact, there is some disappointment among this group about the handling of the health aspects of the crisis by their neighbours. One in seven Czech respondents criticise Poland, and one in six Slovakians are critical of Hungary.

This does not mean that that Visegrad group as an informal coalition of EU27 members has become obsolete. But covid-19 gives reason to reflect on the purpose and limits of this cooperation framework. The 2020 Coalition Explorer had already begun to show that Slovakia (the only eurozone member among the four) was increasingly detached from the others in terms of its priorities and partners. At the same time, half of Slovakian respondents – and one-third of those from the Czech Republic – identified Hungary as the country that had disappointed them most over the previous two years; and some held a similar view of Poland. The Visegrad group might still prove to be a useful platform for them to work together on certain EU27 initiatives, as happened with the countries’ collective opposition to the refugee relocation scheme after the 2015 migration crisis. But, other than that, there is currently more disappointment than kinship within the group. Covid-19 has not consolidated cooperation between the four members of the Visegrad group. And, if the EU27 focuses on economic issues in the years to come, this may make it even more difficult for Slovakia to be on the same wavelength with the rest of the group.

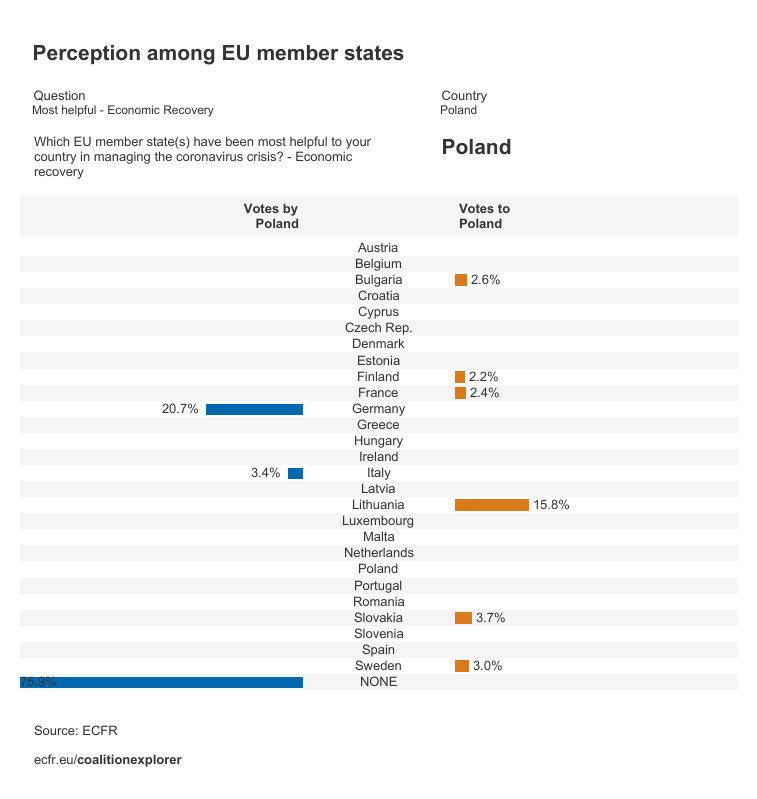

The coronavirus crisis may have been a non-event for cooperation within the Visegrad group, but it was also a national rather than European experience for Poland. The country’s low profile in the EU’s handling of covid-19 is disappointing enough – given that it aspires to form the EU’s post-Brexit ‘Big Five’ alongside Germany, France, Italy, and Spain. But Warsaw rarely made its way onto the mental map of other capital cities on any coronavirus issue, and thus became something of a bystander despite some efforts at cross-border solidarity. It receives some praise from Slovenian policy professionals for its support on the public health front. But it is strongly criticised by Lithuanian and Estonian respondents for its role on both health policy and the economic recovery, perhaps due to the Polish government’s reluctance to let Baltic expats return home through its territory. There is little other evidence of Poland’s role in Europe during the crisis. It appears that prime minister Mateusz Morawiecki’s efforts to present Poland as a partner to southern member states – as evidenced, among other things, by his call for greater financial solidarity published in La Repubblica) – did not have much effect. Nor did Poland’s decision to send medical personnel and material to Italy and Spain, which ECFR’s European Solidarity Tracker documents.

Other countries have not been on Poles’ minds either. Asked about the most helpful partners in managing the economic recovery from the coronavirus crisis, three-quarters of Polish respondents say “no one” (the third-highest result for this option in the EU27, after Malta and Denmark). Even more respond “no one” when asked who the most disappointing partner on the economic front has been – which suggests a belief that this aspect of the crisis should be managed by each member state on its own. Last but not least, when asked which country has demonstrated most leadership in the EU’s handling of the crisis, one-third of respondents in Poland say “no one” – a higher share than that in any other member state.

Covid-19 has not only had a disproportionate effect on different EU groupings, it has also very often been just a local event. On who caused the most disappointment on the health front, the leading answer across all EU27 countries is “no one” (31 per cent), and only then Italy (11 per cent), and Sweden (8 per cent). The high numbers for these two countries are mostly driven by assessments from their neighbours: Slovenia, Austria, and Croatia in Italy’s case; Finland and Denmark in Sweden’s. This may reflect a feeling that the governments in Rome and Stockholm did not control the pandemic in a way that made their neighbours feel safe.

While criticism is limited to geographically close partners, it also serves as a reminder that member states need to think about how their actions produce externalities for others. Italy’s neighbours had good reason to feel anxious about the country’s initial reaction to the pandemic, just as Sweden’s neighbours felt uneasy about the lack of serious restrictions in the country. In those localised areas, the perception of interconnectedness in the face of new challenges and threats may well stay with Europeans after the crisis. It remains to be seen whether this also encourages them to cooperate more in the future. According to ECFR’s public opinion poll, across the nine surveyed countries, 52 per cent of people said that the EU should develop a more common response to global threats and challenges – and this also emerged as the main thing that people agreed should change in Europe once the coronavirus crisis was over.

Conclusion: A house divided

A friend in need is a friend indeed, goes the saying. The covid-19 crisis might have strengthened some bonds, such as those among Europe’s southern member states, and challenged others, such as the Visegrad group’s. It has also consolidated or harmed the image of some leaders – Germany and the Netherlands respectively. But European cooperation is, ultimately, a matter of partners rather than necessarily friends. The Visegrad platform will remain a cooperation option that may prove useful, on occasion, to its members, just as the Netherlands will remain a key EU27 player on many issues.

Moreover, things have already moved on since May, when ECFR conducted the survey. The pandemic has subsided in most member states – although not everywhere. At the same time, negotiations over the EU’s recovery fund, and the bloc’s next multiannual budget, have gained momentum. As a result, attitudes towards EU institutions and national governments may have already changed. However, this snapshot deserves to be taken seriously.

What might have changed because of this crisis is the level of trust between partners, and the illusions that they hold about one another. But EU politics is an iterative game. This has been one crisis; others will come along. So, rather than asking who is up and who is down, this moment should instead prompt each of the EU27 capitals to reflect on their own performance. What does it mean for Germany, and for others, if everyone sees Berlin – and nobody else – as a leader? What conclusions should the Netherlands draw from the high levels of disappointment about the economic positions it has taken – and will this disappointment prevent it from deploying its coalition potential in other areas? What are the implication of the divergent experiences of the south and the Visegrad countries for how they cooperate within their respective groups in the EU – starting with the ongoing negotiations on the Multiannual Financial Framework and the shape of the recovery fund?

European policy professionals’ views on these matters will have a bearing on how member states work together in the years to come. If there is one Europe-wide trend that emerges from the evidence, it relates to the renewed divide between north and south. This is set to define the way that the EU27 get along in the near future – and how they shape their own expectations vis-à-vis the EU.

ECFR’s public opinion poll shows that it is not only the usual suspects, such as the Italians and French, but also Spanish citizens who have seemed disillusioned with the performance of EU institutions, and the EU in general, during the course of the coronavirus crisis. At the same time, voters in the south – especially those in Portugal, Spain, and Italy – appear to be the biggest supporters of greater financial burden-sharing among member states. But voters in the north have a fundamentally different perspective. Danes and Germans have had a much less dramatic experience with covid-19, and – given their generally strong economic situation – are much more confident in their ability to cope, even with a pandemic, on their own. They are also much less willing to support financial solidarity in the EU, perhaps because they are on a different wavelength in their experiences, feelings, and memories related to the crisis. This is apparent in another survey – the latest Eurobarometer – which shows that “confidence” is the way that one-third of Dutch and Danish citizens describe their emotional state at the height of the pandemic. This sentiment was rarely expressed in Spain and Greece, where “uncertainty” was the most widespread feeling.

Cooperation between southern member states has increased, but there is a risk that their perspectives will become too intransigent. This would not encourage countries of the north to acknowledge that financial burden-sharing would be beneficial to them too, as the stability of the single market, the eurozone, and other EU frameworks is in their national interest. Moralising arguments from both sides only make it harder for them to reach an agreement.

This puts the onus on Germany and France, as they will have to work together especially closely to mitigate the effects of the north-south divide. Germans may be obliged to show even more understanding for the south’s position, even if, among the political establishment in Berlin, many still see themselves as members of the north rather than as the EU’s indispensable leaders. According to this year’s Coalition Explorer, German policymakers see not just France but also the more ‘frugal’ Netherlands, Austria, and Finland as Germany’s essential partners on fiscal policy.

And France, while closely linked to the south, would have to serve as a bridge-builder when working with Germany to bring greater cohesion to the EU. This is not something that Macron was always willing or able to do in the past. But it will nevertheless fall to the French and German governments to construct coalitions on different issues – from the climate to energy, to foreign policy, to digital policy – that strengthen the EU. Other member states already recognise Germany as the informal leader of the EU27, but recent efforts by Macron to reach out to partners in the east and the north are yet to bear fruit.

What is striking is the extent to which the other fundamental divide in the EU – between east and west – could, as a side-effect, be relegated to a second-order issue. Structural differences between east and west may well remain as significant as they are today, but the EU’s political attention could increasingly shift towards the recovery in the south. Surveys of both policy professionals and the general public suggest that many central and eastern European countries have been mostly onlookers in a continent-wide crisis. Few of them are members of the eurozone, and therefore they have rarely been at the forefront of the discussions about the Eurobonds, which later paved the way for the ongoing negotiations on the recovery fund. Besides, central and eastern European member states – fortunately for them – largely escaped the worst consequences of covid-19 in both health and economic terms.

This looks, first and foremost, like a story about the south and the north, with southern countries not only calling for financial support in the recovery, but also being most vocal about the need to preserve a level playing field in the EU’s single market. In this, they refer to the fact that the relaxation of state-aid rules by the European Commission in response to covid-19 could further complicate the economic situation in the south. They lack the same fiscal capacity as their northern counterparts and, therefore, cannot afford the same amount of support for their national companies during the crisis. But, on that last point, most countries in the east would have good reason to be vocal too – and yet their voice has not been heard.

The revival of the north-south divide may be considered good news by some people in Warsaw or Budapest. They might hope that, focused on the economic recovery, the EU will have less time and resources to cope with other issues, such as the rule of law – even if the commissioner for values and transparency, Vera Jourova, is doing much to make this seem wishful thinking. There may even be something resembling a multi-level game of chess in which decisions on the climate, the rule of law, and the recovery fund are interlinked. It would be good news if, by tying funding to green goals and to the rule of law criteria, the EU encouraged its wealthier members to provide more funds for the EU’s recovery and its long-term budget. But it could also be bad news if eastern countries’ support for a south-orientated recovery package were secured in exchange for the EU and its member states paying less attention to rule of law issues. Other intermediate scenarios are also possible: states such as Hungary could head off rule of law conditionality by playing ball, or at least lip service, on green projects. It may be hard to avoid such trade-offs.

However, there is another, equally serious, danger. With the EU’s political focus on stabilising the economic situation in the south, and perhaps further eurozone integration ahead, there is a risk that some countries in the east could feel that they are not getting enough attention – and that, in effect, they are drifting away from other member states economically and politically. This would put the pro-Europeanism of these societies to a serious test. Perhaps the fact that, according to the European Commission’s initial proposal, Poland was set to become, in nominal terms, the third-largest beneficiary of the recovery fund – behind Italy and Spain, but ahead of France – reflected an intention to keep the Poles (and, by extension, other central Europeans) on board. Hungary was also expected to benefit significantly from the fund, relative to the size of its economy. But this was just the beginning of a long and complex negotiation, at the end of which – as signalled above – the same countries could receive less than the Commission’s initial proposal suggested, in exchange for other promises.

That would send a very bad message about where the EU sees its priorities, because a decreased focus on the rule of law should not be the price to pay for failure to agree on an ambitious recovery plan. However, while governments in the north may eventually agree to generous support for the most distressed economies of the south, through both loans and grants, they might find it hard to explain to their voters why they are also sending new funds to the member states with the weakest records on the rule of law. In this sense, countries that joined the EU in 2004 or later now need to convince their fellow EU members that they still deserve the latter’s trust, support, and attention. It remains to be seen how countries in the east – from Slovakia, to Romania, to the Baltic states – position themselves in these discussions. ECFR’s Policy Intentions mapping shows that the EU’s eastern members are actually deeply divided on the rule of law, with several of them feeling as uneasy about Budapest’s and Warsaw’s misconduct as most of their Western partners.

If negotiations conclude with a compromise based on the lowest common denominator, the EU could find itself trapped in a more systemic dynamic of divergence: between the EU’s more and less innovative economies; between eurozone and non-eurozone members; between countries that have a large fiscal capacity and those that do not; and between democracies with well-functioning checks and balances, and others where these systems have come under attack. In a sense, this is indeed Europe’s “defining moment”, as Ursula von der Leyen put it when presenting the recovery plan to the European Parliament in May. The current negotiations create a big opportunity to improve how European integration works, by sending a strong signal about European solidarity and sovereignty, but also by equipping the EU with the necessary funding for the green transition, research, and digital policy. However, passing up this opportunity would not be equivalent to maintaining the status quo – it would instead amount to a significant step backwards.

Ensuring that west and east do not drift too far apart while the EU’s focus is on keeping the south afloat is a real headache for Germany as it takes over the EU presidency. Merkel says she does not like discussion that divides Europeans into north, south, and east; and she is right that, ideally, one should try to see things from the perspective of fellow Europeans. Nevertheless, in practice, it will be up to national governments from different geographical corners of the EU to agree, by unanimity, on the bloc’s multiannual budget – and, very likely, also on the recovery fund as part of the same package. Of course, north, south, and east are not monoliths – but there are cross-cutting patterns that make the challenge of closing the EU’s divides tangible and real. It is encouraging to see leaders such as Macron and Michel take the initiative in the run-up to the decisive meetings. As a country that is “doomed to lead” Europe, Germany badly needs such support. And the same goes for the EU – which, to move things forward, needs coalitions that work, engagement from all its members, and institutions that create the conditions for countries to work together. On this account, at least, covid-19 changed little.

Bar charts presented in the Coronavirus Special display information by percentage of votes, not percentage of respondents. In order to also see the percentage of respondents who chose a particular response, one needs to hover over an interactive version of the graphics which can be found on EU Coalition Explorer's Coronavirus Special. The difference between the two (votes and respondents) stems from the fact that those participating in the survey could choose up to five responses on which country has been most helpful, most disappointing, or showed most leadership. Therefore, a percentage of votes for one country does not necessarily correspond to the percentage of respondents that chose a particular answer.

About the author

Pawel Zerka is policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He contributes to ECFR’s Rethink: Europe initiative, which explores and illustrates European cooperation in innovative ways. Zerka is also engaged in the analysis of the European public opinion as part of ECFR’s Unlock initiative. Based in ECFR’s Paris office, he ha been part of the team since August 2017. He holds a PhD in economics and an MA in international relations from the Warsaw School of Economics, having also studied at Sciences Po Bordeaux and Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Acknowledgements

This paper is the result of a truly collaborative process. Within ECFR’s Rethink: Europe team – which includes Claire Busse, Ulrike Esther Franke, Rafael Loss, Jana Puglierin, and Marlene Riedel – we together went through the successive stages of research: from the conception of the coronavirus survey, to fieldwork, visualisation, and analysis. Conversations with Susi Dennison were crucial throughout that process. Christoph Klavehn designed the visualisations, while Juan Ruitiña ensured these all looked pretty on our website. I feel deeply indebted to Adam Harrison for his great editing. And to Josef Janning who led ECFR’s Rethink: Europe team until the end of 2019; it is thanks to him and his colleagues that the Coalition Explorer became ECFR’s flagship project. Finally, on behalf of ECFR, I would like to thank Sophie Rau and Stiftung Mercator for their enduring support of ECFR and Rethink: Europe. Despite all these many and varied forms of input, any errors in the report remain the author’s own.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.