The frugal blues: An underappreciated threat to the European project

It would be premature to conclude that the frugal four are, or will remain, happy about the EU’s budgetary deal.

The European Union’s new budgetary package – whose details it needs to finalise by the end of this year – may well be remembered as a giant leap in the history of European solidarity. If shaped badly, however, it could push EU societies further apart.

The European Parliament, the European Council, and the European Commission are currently negotiating the four main elements of the package – a €1.07 trillion financial framework covering the next seven years; a temporary recovery instrument worth €750bn and known as “Next Generation EU”; a decision on the EU’s new resources; and a regulation on the rule of law – in “trilogues” (tripartite meetings). Various members of the European Parliament are pressing hard to condition access to EU funding on respect for the rule of law. Other forms of conditionality (such as measures to ensure that spending aligns with Europe’s green and digital transition) are also part of the discussion – particularly with respect to national resilience plans, in which member states are supposed to show how they intend to spend the recovery funds.

But the parties to the negotiations have little room for manoeuvre, especially on the rule of law. The Council is restricted by the mandate that member states gave it in July. Hungary and Poland could easily veto any attempt to change that mandate. And MEPs are under pressure to swiftly finalise the overall agreement, so that the money can flow without delay to Europe’s most troubled economies – those in the south. For all these reasons, there is a significant chance that the EU will end up with very weak conditionality on, and control over, spending under the new budget and the temporary recovery instrument.

If it does, the bloc will have missed an opportunity to reaffirm European values more broadly, and to pressure member states into implementing structural reforms. And it could also create a backlash among many of the net contributors to the EU budget. This is particularly true of the “frugal four” – an informal grouping of fiscally conservative member states that includes the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, and Austria (occasionally joined by Finland).

Just consider how citizens in Sweden or the Netherlands might look at the situation. Their fellow Europeans from Italy and Spain have just secured what they were calling for: a large recovery instrument, more than half of it financed through direct grants. The governments of Poland and Hungary, for their part, can realistically expect to receive another generous round of EU structural funding – despite serious rule of law problems in their countries, and the fact that they demonstrated little European solidarity during the 2015 migration crisis.

The cost-benefit analysis of EU membership will likely become a hot topic of the campaign for the next parliamentary election in the Netherlands.

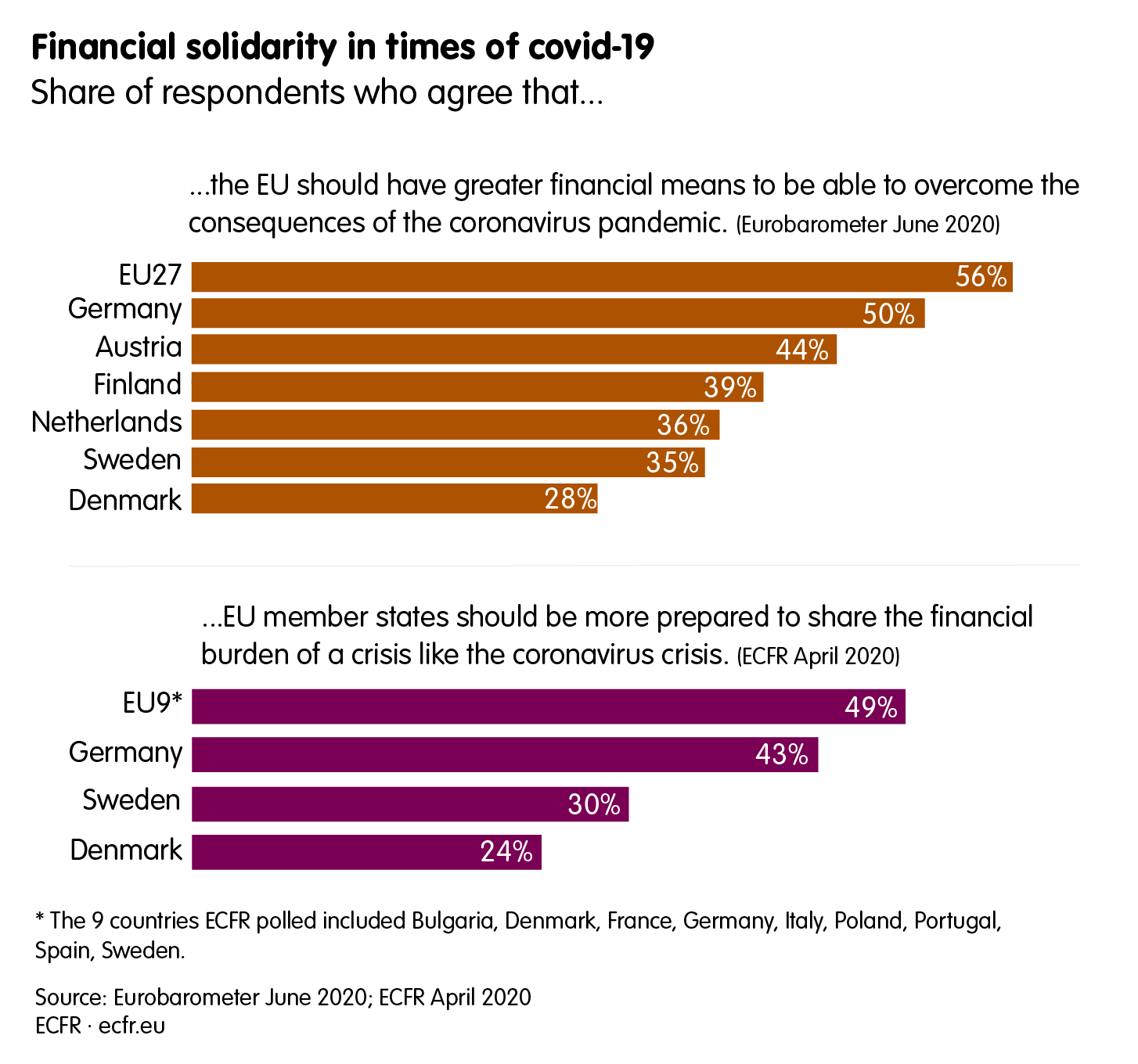

The Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, and Austria have long had reservations about the EU – what one might call the “frugal blues”. This is part of the reason why the populist right was on the rise in these countries for many years, until the covid-19 emergency hit. Still, it has been striking to see that, even in the context of an event as exceptional as the pandemic, they have been so reluctant to support financial solidarity between EU member states. According to polling by the European Council on Foreign Relations in late April, just 24 per cent of Danes and 30 per cent of Swedes agreed that EU member states should be more prepared to share the financial burden of a crisis. This view was common among not just supporters of the populist right but also mainstream voters.

Other surveys confirm this. According to Eurobarometer, in the second half of June, only 28 per cent of Danes approved of a bigger EU budget to tackle the coronavirus crisis (while 49 per cent said that they did not). The approval rating was 35 per cent in Sweden, 36 per cent in the Netherlands, and 39 per cent in Finland. Austrians seemed to be the least frugal in the group: 44 per cent agreed that the EU needed a larger budget (while 42 per cent disagreed). But this still pales in comparison to the neighbouring Germans, half of whom approved of an increased EU budget (while 36 per cent were against it).

So – apart from some new rebates – what do the frugals gain from the EU’s new agreements? True, they benefit from the fact that the EU did not fall apart – but, while this is not a minor achievement, the force of the argument will vanish quickly. If people in these countries are to continue believing that EU membership benefits them, they might need more. The incentives could include, for example, a reassurance that EU funds will help promote their goals (such as the green transition); will not finance non-LGBT zones in Poland or corrupt practices in Hungary; or will be conditioned on serious structural reforms in southern and eastern countries – with whom, after all, the frugals agreed to issue joint debt to pay for the recovery. That third issue could be particularly relevant for the Netherlands and Austria, which (unlike Denmark and Sweden) are part of the eurozone and, therefore, have a greater interest in ensuring that southern economies perform well.

Of course, EU membership is about much more than the EU budget – and there are many other ways to keep the frugals engaged, committed, and happy. As ECFR’s Policy Intentions Mapping shows, Sweden and the Netherlands favour an ambitious push to complete the European single market. Both countries, alongside Austria and Finland, would likely support a revamped EU foreign policy, allowing for qualified majority voting in some areas of the Common Foreign and Security Policy. Together with Denmark, they are in the avant-garde of climate policy. At the same time, digital issues and the rule of law are high on the list of priorities for EU policy of all five countries – as ECFR’s Coalition Explorer demonstrates.

Early evidence might suggest that the frugals have accepted the political agreement EU member states reached at the special European Council meeting on 17-21 July. A survey conducted in Finland in late July showed that only one-quarter of the Finnish population disagreed with the deal, and a similar proportion supported it outright, while 42 per cent of respondents considered it a “necessary evil”. Another poll conducted at roughly the same time showed that twice as many Austrians supported the deal as opposed it. And Danes have some grounds to be content with the deal, given that their country will have to pay less than the government originally predicted – thanks to the increased rebates obtained by the frugals, and given that Denmark’s government expected a the EU to have a bigger overall budget.

But it would be premature to conclude that the frugals are, or will remain, happy about the EU’s budgetary deal. The cost-benefit analysis of EU membership will likely become a hot topic of the campaign for the next parliamentary election in the Netherlands, scheduled for March next year. This perhaps explains Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte’s striking suggestion that the EU could be re-established without Poland and Hungary if the rule of law situation got out of control. The EU could also feature in the public debate in Sweden, where the ruling coalition is already under fire from all opposition parties for its acceptance of the July deal.

In general, the lazy summer period may have given a false impression that there is no longer strong resistance to the EU’s budget among the frugals. But this is partly because the nitty-gritty of the deal, as well as its real-life effects, remain to be seen. Such resistance may, therefore, re-emerge in the next weeks and months, when politicians start discussing the effects of EU commitments on national budgets, and when the yet-to-be-negotiated details of the deal become clear – especially if it turns out that the promise of conditionality was empty. In this scenario, financial solidarity between member states could even decline in the next seven years, or whenever the next calamity hits Europe. The political agreement member states reached in July warrants a sense of relief – but it shouldn’t lead to complacency.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.