Measured response: How to design a European instrument against economic coercion

Summary

- Europe is at ever greater risk of economic coercion from other powers.

- To protect itself, the EU could adopt a new anti-coercion instrument (ACI) to allow it to impose economic countermeasures.

- The ACI needs to enable countermeasures that are both effective and credible; if it does not, this could carry more risks than benefits.

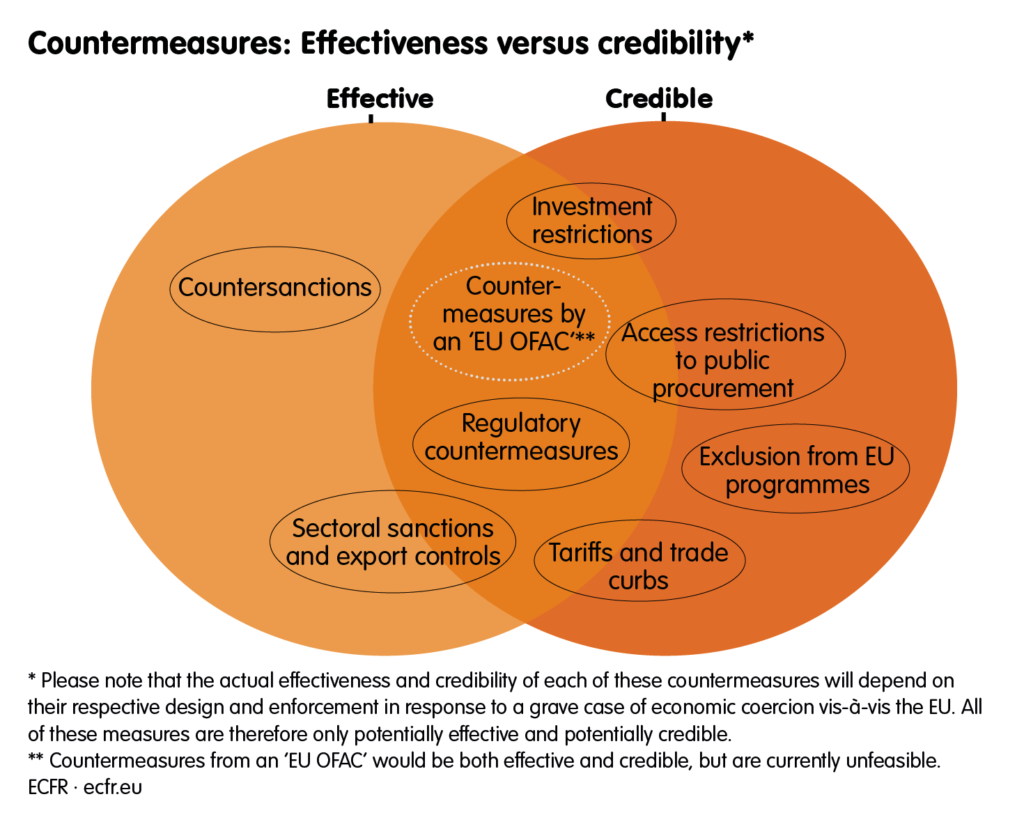

- These countermeasures could include: trade and investment restrictions; export controls and divestment in certain sectors; and restrictions on access to EU public procurement markets.

- The EU should also include a flexibility mechanism for countermeasures against those forms of economic coercion the ACI cannot cover explicitly.

- The ACI should be a de-politicisation tool. It must be used only as last resort and should include an effective de-escalation mechanism to trigger dialogue and negotiations.

Promising option: An EU anti-coercion instrument

It used to be the case that the European Union had no options available to it when confronted with other global players’ use of economic coercion against it. This coercion would gravely violate either European or national sovereignty. But, now, Europe has an option available to it strengthen itself against economic coercion. The European Commission is currently in the process of designing an anti-coercion instrument (ACI), which would allow Europe to take countermeasures against third-country coercion and act as a deterrent against coercive practices (similar to the option of a collective defence instrument that the European Council on Foreign Relations analysed last year). The Commission is set to propose the ACI this autumn as part of its Open Strategic Autonomy trade strategy. Member states will then decide whether they would like to establish the deterrent.

But what should the ACI look like? What is the specific gap in the EU’s defences that it would fill? What forms of economic coercion could trigger EU countermeasures? And what sort of countermeasures should it use? How would the EU decide whether to impose them? Critically, could the EU really ensure that the ACI would strengthen its position, given the significant risks involved?

There appears to be an avenue for designing an ACI that would answer these questions, and would ensure the EU became less vulnerable to economic coercion. But it is a daunting task. This report proposes several ideas for how the EU can approach this challenge. It indicates which ideas might be most feasible and effective. It is based on the work of ECFR’s Task Force for Strengthening Europe against Economic Coercion, which brings together high-level representatives from six EU member state governments and the private sector.

This report is a product of the European Council Foreign Relations’ work and the opinions expressed in it those of the individual authors. The report presents ideas for the European debate. It is based on a systematic consultation exercise that engaged with high-level public and private actors from the Czech Republic, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden. ECFR’s Task Force for Strengthening Europe against Economic Coercion worked on these proposals during the first half of 2021. Members of the task force discussed several possible responses to economic coercion, and several options for an anti-coercion instrument. The paper does not reflect a consensus of the task force. The authors of the paper took into account how participants from diverse backgrounds in the public and private sectors, and academia, collectively viewed the opportunities and challenges of an anti-coercion instrument.

The threats

Today, Europe may be more at risk than ever of suffering from a wide range of economically coercive measures from China and other powerful third countries.

China is willing to use economic punishment to change EU policies: In March 2021, Beijing imposed de facto economic sanctions on European companies to send a message to the EU. After the EU imposed human rights sanctions on four local Chinese officials in coordination with the US, Beijing responded in a wildly asymmetric fashion. It directed its action against European ambassadors, parliamentarians, and think-tankers, but also against European companies such as H&M and Adidas, which disappeared from Chinese e-commerce apps in the face of so-called “popular boycotts”. The latter are an increasingly common Chinese sanctions tactic. Even if the economic damage was limited, Beijing mainly seemed to want to send a message to Europeans to say: China is now ready to use economic coercion in direct response to European policy choices – to even moderate EU attempts to adopt stronger policies and close ranks with the US. President Xi Jinping told Chancellor Angela Merkel as much. According to Xinhua, Europe was “to make [a] correct judgment independently.”

Beijing generally refrains from using many of the tools available to it, particularly those overseen by its Ministry of Commerce and especially vis-à-vis the EU. Tying Europe further into its value chains and making it more dependent on China remains an appealing prospect for Beijing. But, as the US and Europe are closely aligned once again, and given that tensions with China are likely to persist, there is a great risk that Beijing will have fewer inhibitions about using such measures. The stronger China gets, the more likely and more consequential Chinese economic coercion will become. Some Europeans, such as the members of a possible new German government containing the Green party, may want to take tougher stances on Chinese human rights violations. China has shown that this comes with a great risk of economic punishment, especially if the EU is not more resilient. In recent years, China has demonstrated the coercion it is willing and able to use on – for instance –Australia, Germany, the Netherlands, and Canada (see overview).

- It is not about any one actor: Globalisation is changing. A wide array of countries willingly and actively combine state action, geopolitics, and economics; they use economic tools for geopolitical power and geopolitics for economic gain. Their economic weight is increasing relative to that of the G7, which by 2050 will probably only account for around 20 per cent of world GDP. The EU’s partners, from the United States to the United Kingdom and others, have started to adapt to these developments, enhancing their geo-economic toolbox for their own defences and responding to unfair practices by China and others that they could not previously address. Their adaptation – and the irresponsible and dangerous use of economic coercion by former US president Donald Trump – contributed to the emergence of a much more geo-economic era. But the change is structural, and the EU needs to deal with it using its own tools. Russia and even Turkey have used similar blackmail against the EU, such as when Russia threatened to impose economic sanctions on the Czech Republic this spring (see overview).

- Increasing coercion of the private sector: To achieve their goals, states increasingly use economic coercion against companies rather than governments. This often puts companies between a rock and a hard place, and de facto alters European foreign and trade policy without targeting EU governments directly. In part, this is because coercion increasingly functions through central hubs – a critical technology or centralised point of exchange – in economic networks, where third countries can exploit the fact that European companies need access to them. The EU sometimes calls this “extraterritorial reach”, but it too often thinks of this in terms of US extraterritorial sanctions and not as a structural development in how economic coercion can function – or that China is increasingly in a position to use economic coercion in these ways. To gain influence, isolate a country, or make sure another state does not get access to information or goods, third countries have already imposed a rising number of new regulations on companies. These include obligations, prohibition of compliance with other countries’ laws, and licensing requirements for more and more goods and services. China’s newly adopted extraterritorial export controls, its anti-sanctions law, and its blocking statute are examples of this. If European firms follow obligations they have in the US or the EU, they may have to ask Beijing’s permission to export certain goods or services, face punishment, or even be cut off from doing business in China (see overview).

- Informal economic coercion is a major challenge: Economic coercion in authoritarian countries is often informal and hard to detect. But it is highly consequential. And the EU’s rivals will increasingly regard economic coercion as their preferred option if the EU does not take this into account (see overview).

Overview: Select economic coercion tools by category

Punitive tariffs and trade curbs

- China curbed 10 per cent of Australian exports as punishment for Australia’s call for independent investigations into the origins of covid-19.

- China also used the threat of car tariffs to try to pressure Germany into accepting Huawei’s bid to build the country’s 5G infrastructure.

- Russia used ‘public health concerns’ as a pretext to ban Polish imports of fruits and vegetables in 2014, following EU sanctions over the war in Ukraine.

- The Trump administration used the threat of section 301 tariffs to prevent France and other European countries from levying taxes on digital services. Even the Biden administration renewed the threat, but preferred a multilateral solution with the EU.

Regulatory squeeze

- This approach aims to influence business behaviour and put companies between a rock and a hard place.

- China’s anti-sanctions law allows for punishment if companies make or implement “discriminatory” measures.

- China’s blocking statute prohibits compliance with US or EU measures, at least for subsidiaries in China.

- Russia passed similar legislation in 2018 and 2020.

Informal pressure

- Authoritarian governments often exercise economic coercion informally by pressuring foreign companies with threats of significant disadvantages if they refuse to act in their favour.

- For instance, this can create de facto and ‘individualised’ export controls.

- Chinese measures such as disappearance from e-commerce apps have been called “sanctions with Chinese characteristics”.

“Popular boycotts”

- European companies such as Adidas and H&M faced a “popular boycott” – an increasingly common Chinese sanctions tactic – shortly after the EU listed four local Chinese officials over human rights violations in Xinjiang.

- President Recep Tayyip Erdogan called on Turks to boycott buying French-labelled goods following Macron’s announcement of policies to combat extremism.

Extraterritorial export control laws

- China can prevent European companies from selling their products to other firms, even if not for military use. The product only has to have passed through China.

- The US has expanded extraterritorial export controls, but the EU’s policies are now closely aligned with those of the US.

Sanctions

- China punished European companies such as H&M and Adidas for EU human rights policies. Their products suddenly disappeared from Chinese e-commerce apps.

- US secondary sanctions still cut off nearly all European trade from an entire country, but the Biden administration has put them under review and is trying to find a deal with Iran jointly with Europeans that would allow it to lift them.

- US sanctions on the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline have shown that even Democrats may favour sanctioning allied projects at times (whatever the merits of the pipeline). But Joe Biden stopped further sanctions and emphasises diplomacy.

Transatlantic relations

The US is back as a reliable partner and protector of the EU. Close ties with Washington are essential for many reasons, not least because of the values that Europe and America share. But they are also important for Europe to be able to handle economic coercion: joint policies can increase the EU’s resilience. And solidarity with the US and many other like-minded partners also acts as a deterrent to third-country coercion. At the EU-US summit in June, Europeans and Americans underscored that tackling economic coercion by third countries is a shared transatlantic concern. The summit left no doubt that they are on the same side in this battle. The EU needs to continue to take active steps, to be ready for compromise, to build back better in relations with the US, and to strengthen the rules-based international order.

But, to improve transatlantic relations, this is not sufficient. Both the EU and the US need to keep a number of things in mind. The EU needs to understand that Washington cannot always help, and that the US expects the EU to reduce its vulnerabilities, including by acquiring greater capabilities for itself. The US would choose a resilient Europe over a vulnerable one as its partner. At the same time, the US needs to understand that Europeans worry about “America First” in disguise (Joe Biden’s “Buy American” exhortation suggests this has not entirely disappeared) and about unilateral US measures – not least extraterritorial sanctions, which – to lend US foreign policy greater effect – privilege coercion of allies or allied companies over a strong, jointly agreed transatlantic stance. Such US measures are not a big problem when European and American policy stances are aligned, or when Washington takes into account the EU’s viewpoint – as is the case now under Biden. But, if there is no policy alignment in the future, there is a risk of the EU experiencing new measures from the US. The US will take Europe into account more if the EU makes clear that doing so would be in America’s own interest – and the closest possible transatlantic relationship is in the interests of both.

Key considerations for decision-makers

The EU should consider the following key points as it contemplates how to establish a new anti-coercion instrument.

- Economic strength: The most important tools for countering economic coercion are to build up the EU’s economic strength and set a positive agenda. Completing and strengthening the single market and European competitiveness are key to reducing asymmetries and alleviating Europe’s reliance on chokepoints that third countries can exploit. A positive trade agenda can be critical in diversifying trade relations. An ACI can only complement this.

- Toolbox comprehensiveness: The EU cannot rely on economic strength and a positive agenda alone. It needs both positive and defensive tools. In addition to a positive agenda, an EU Resilience Office and other resilience tools are important. But they risk being ineffective without a deterrent under an ACI. Europe currently disincentivises multilateral solutions in the new geo-economic era: the EU relies on third countries treating it fairly, but they can benefit by treating it unfairly.

- Need for a last-resort option: Europeans need and want to remain committed multilateralists. The ACI can only be a last-resort instrument. But, when the need arises, Europeans will need to be prepared if they are to safely navigate the new geo-economic era.

- With resilience comes responsibility: Greater resilience could tempt some in the EU to disengage from important questions in international politics if acquiring this resilience meant that the EU was less concerned about how third countries behave. Nevertheless, the EU needs to stand up for its values, from human rights to rules-based trade. This means strengthening its own sanctions capability and foreign policy.

- A true opportunity: Europeans could easily squander the critical opportunity that the debate around the ACI presents. They could fail to overcome differences on details, losing sight of the strategic importance of building greater resilience. They could categorically reject the idea of ever using countermeasures because their preference is for open, rules-based trade. But there are reasons for European actors with very different perspectives to consider the establishment of an ACI: the last few years have exposed Europeans’ vulnerabilities. China, a systemic rival, is making clear that it is ready to exploit them. Many in Europe realise a pure focus on open trade does not sufficiently address the threat because their own companies have experienced economic coercion first hand, especially in China. They also know the EU has to prove it is a capable partner for the US – and show itself to be a credible partner that does not constantly trip itself up in its own decision-making. Whatever Europeans decide in the end, these pressures show that it is worth engaging in an open-minded debate about establishing an EU anti-coercion instrument.

A gap in the EU’s defences

If third countries conduct economic coercion successfully against Europeans, it will have four features:

- Trade as a weapon: Coercion can alter domestic or company policies and violate sovereignty.

- Swiftness: Coercion succeeds long before the EU can act.

- Grey zone tools: The EU’s and the WTO’s rulebooks do not effectively capture coercion.

- The power of division: Coercion hits asymmetrically and divides the EU rather than uniting it.

There is a gap in the EU’s defences against economic coercion. The EU has a wide range of tools that it can use to defend itself when third countries use economic means in pursuit of a geopolitical goal. These include using dispute settlement mechanism at the World Trade Organization (WTO), relevant provisions contained within bilateral agreements with third countries, and traditional trade defence instruments. The EU has also recently added to its armoury an updated trade enforcement regulation that allows it to act in trade matters even if – due to blockages in the organisation caused by the Trump administration’s refusal to appoint new members to its appellate body – there is no final WTO ruling. Furthermore, the EU put in place an investment screening mechanism to counter strategic takeovers, which became operational in 2020. And the EU has recently revised export controls relating to human rights and dual-use items.

However, when other powers use economic coercion against Europeans, their actions are often characterised by the following features.

Trade as a weapon: Economic coercion has a different goal to unfair trade practices. It seeks to alter government or company policies to the geopolitical or economic advantage of the coercing state or organisation. The WTO struggles with this politicisation of trade and investment: its role is to determine whether a practice is in line with the rules of international trade. But third countries can use economic pressure to achieve a different goal – influencing other countries’ policy choices on, for example, telecommunications, energy, human rights, or tax. In such cases, economic coercion could constitute a violation of international public law. China punished Australia for calling for an international investigation into the covid-19 pandemic outbreak, for instance, but the fact that it aimed to alter Australian policy (and the policy of other countries by implication) is not taken into account in the context of the WTO. Similarly, the Chinese ambassador in Berlin threatened punitive tariffs on German car exports if Germany banned Huawei from building its 5G network. The real issue in such cases is not whether this type of measure would have constituted an unfair trade practice, but whether they alter German policies or the safety of the country’s critical infrastructure.

Swiftness: If third countries use economic coercion, they can prevent Europeans from enacting their own policies and take businesses hostage long before the WTO finds that they have violated trade law (if the organisation does so at all) or before Europeans manage to react. The problem is that economic coercion exploits the slowness of any response; even if the WTO dispute settlement mechanism was functioning properly, decision-makers in governments and the private sector often have a just few days to make a consequential policy decision. By the time a punitive tariff, a sanction, or a popular boycott has been found to be illegal, a government has already been forced to decide how to build a 5G network, whether to impose a certain tax, or whether to pursue a particular human rights issue. For instance, in October 2019, Trump threatened to swiftly cut Europeans off from trade with Turkey by imposing extraterritorial sanctions on European companies, as a means of trying to change Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s position on Syria. The war in Syria, and European commercial dealings with Turkey, would have been in a very different place by the time the dispute settlement mechanism found that such drastic sanctions allowed for countermeasures. And leaders other than Trump are also capable of speedy coercive action: China also moved quickly against Australia. In the short term, European policymakers face a stark choice in the era of economic coercion: stop taking strong positions on human rights or incur economic costs; include Huawei in European 5G networks or accept job losses; stop certain dealings with a third country or face punishment. That time frame matters.

Operating in a grey zone: Not all instances of economic coercion fall into the category of potentially unfair trade practices. China justified its punitive measures against Australia with seemingly ‘legitimate’ anti-dumping and health justifications. Australia already had more anti-dumping measures in place against China than vice versa, and a WTO review of the situation may not favour Australia. There may even be situations in which a third country does indeed have a legitimate concern about dumping – but if that third country imposes anti-dumping measures in retaliation for, or to try to deter, unrelated domestic or foreign policies, the WTO rulebook could not capture it at all. Economic coercion also often acts through informal channels, blackmail, or non-trade tools. Merely the creation of uncertainty, or the threat to use a punitive economic measure, can help achieve a third country’s economic coercion goal. Neither Europe’s defences, nor the EU, sufficiently account for the ‘grey zone’ territory in which coercion operates.

Generation of EU divisions: If a third country employs economic coercion in a smart way, it will limit the number of EU member states or economic sectors it uses it against, aiming to leave other Europeans indifferent to what is going on – or even to make some EU states think the coercion is overlapping with their goals. Turning the entire EU or many economic sectors against the punitive actions would not be in the interest of the coercer. And, indeed, Europe frequently struggles to be resilient when economic coercion divides the EU. Third-country coercers often only need to convince one or two countries that European resilience is not worth pursuing in a particular situation. This is why the EU would benefit from having an instrument that facilitates a collective defence approach and is not dependent on unanimity. This would strengthen the EU’s chance of deterring potential perpetrators from trying to divide Europeans.

Closing the gap: A new instrument

An ACI could fill the gap in the EU’s defences outlined above. Under an ACI (or a collective defence instrument), the EU would be able to collectively adopt swift countermeasures to remedy coercive behaviour. Importantly, its main function would be to deter offensive actions by others – and never to pursue offensive actions of the EU’s own. It would be a reactive tool, and would only be used in response to violations of international law and in line with international law, when all other options had failed to secure Europe’s resilience. The use of the instrument would be assessed against the EU’s broader objectives of strengthening multilateralism and in the context of its bilateral relations with a specific country. It would complement existing tools and aim to make diplomacy and multilateralism more effective and solid.

How it would work

The EU would pass a framework regulation that complemented its existing defences and provided the European Commission with an additional legal instrument that it could use to respond to economic coercion. It could establish such an instrument under the EU’s common commercial policy (Article 207 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union).

The new regulation would define the scope of economic coercion that the ACI could cover, as well as the ways in which the EU could adopt countermeasures that it had previously set out.

Legal basis

The European Commission needs to detail the legality of the instrument under international law in a meticulous way: it should be clear that its approach is in line with international law. The ACI would be explicitly designed to enable the EU to adequately respond to economic coercion. Because economic coercion often employs ‘grey zone’ tools that the EU (like the WTO) struggles to deal with, the ACI would be based on international law as lex generalis to the WTO’s lex specialis. Public international law is complementary to WTO law. Behaviour could be illegal under broader international law and could, therefore, permit countermeasures (for details on the possible legal avenue for this instrument, see ECFR’s previous report).

Evaluation

Facing economic coercion, decision-makers in the Commission and member states would need to evaluate the situation. This evaluation could assess:

- Whether the situation meets the definition of a grave case of coercion and thus allows for countermeasures. Questions to decide this would include: Has there been any interference with the jurisdiction of the EU or its member states? Has there been an intention to coerce the EU or its member states? Have there been economic effects?

- The damage inflicted on the EU through third-country coercion, and whether it is measurable qualitatively or quantitatively. The EU will need to do this quickly.

- Whether the situation requires a swift response.

- Whether other ways of resolving the situation quickly (for example, through diplomatic engagement or multilateral options) would not be more fruitful – a ‘last resort test’. The ACI should not be used lightly, but it should be available when the situation requires it.

- Third-country vulnerability. This concerns the areas in which a certain countermeasure could be effective because a third country would like to work with the EU to lift it quickly.

- Whether EU countermeasures are proportional to the damage caused by the original coercive act.

- Whether to go ahead. Even when a hypothetical situation fulfils all the criteria, the EU should still retain the ability to choose not to use the instrument. This could include cases where, for example, the EU concluded that room for a diplomatic solution might open up in the foreseeable future, exceptionally important EU interests call for a different response, or EU countermeasures would pose too great a risk of potential negative economic or political consequences. But a lengthy test procedure would render the ACI ineffective; the EU would need to decide swiftly.

To succeed in all this, the EU probably needs to have better capacities of analysis than it currently has. This raises questions about whether a dedicated entity such as an EU Resilience Office – which had state-of-the-art analysis tools, and was staffed by legal, economic, and geopolitical experts (as discussed in the ECFR paper referenced above) – would be needed to monitor potential coercion. In addition, as things stand, Europe does not provide sufficient possibilities and incentives for private-sector actors to share information about the ways in which companies face coercion – most notably, informal coercion. Companies would sometimes like to do this, but they do not always want to do so directly to decision-makers in Brussels or European capitals, not least because the EU’s laws might require them to behave in ways that the third country is trying, through coercion, to discourage.

Key questions for establishing an effective deterrent

EU decision-makers need options for imposing countermeasures under an ACI. The following sections discuss the key political questions of building this instrument and provide concrete policy options. They include:

- What forms of economic coercion should trigger EU countermeasures?

- What (economic) countermeasures could the EU impose?

- How and when should the EU impose countermeasures?

What forms of economic coercion should trigger EU countermeasures?

Option 1: Violations of state sovereignty only

- This would cover punitive tariffs, trade curbs, and some blackmail of companies.

- The approach would not cover the increasing blackmail of EU companies through economic networks that did not violate state sovereignty.

- Such an option would be less flexible when it comes to reacting to new,informal forms of coercionsuch as popular boycotts.

- This would be legally complex, but less so than an approach with a larger scope.

Option 2: Covering more forms of coercion

- This could allow for countermeasures against types of coercion such as popular boycotts, especially coercion of companies conducted via economic networks (involving, for example, export controls and sanctions).

- This would link the EU Blocking Statute to the ACI and allow countermeasures against extraterritorial sanctions when appropriate.

- EU member states would have to vote to reform the Blocking Statute.

Option 1.5: Violations of state sovereignty with a flexibility mechanism

- This would cover the same scope as option 1, but would also include a flexible resilience mechanism.

- Under such a mechanism, the EU could add particularly grave instances of third-country coercive actions to trigger countermeasures under the ACI in a specific situation – but only if member states agree.

➔ Recommendation: Option 1.5

The choice between these options is not straightforward, but option 1.5 would provide the right balance between the certainty and flexibility the instrument needs, thanks to its flexible resilience mechanism. The EU should be able to respond to economic coercion that causes great damage across companies and sectors, or that is critical to European interests – when member states want to use the ACI. Under option 1, the EU might create a deterrent that is too rigid and that may not be helpful in new situations the EU is unable to anticipate – and that does not allow it to take into account grave forms of economic coercion against businesses. Under option 2, there is a risk of providing powers that are too broad and furthering protectionist risks.

Decision-makers should take on board the ways in which the EU could implement the options set out above. The following subsections consider this in more detail.

Option 1: A tool responding only to predefined coercion that violates a government’s sovereignty

The EU could adopt an ACI that can enact countermeasures to a set of predefined third-country practices that gravely violate the sovereignty of a member state or several member states.

This way, Europe could significantly close the gap in its defences outlined above. It would only cover pressure put on companies with the goal of changing their behaviour when a third country clearly tries to alter the sovereign decisions of EU governments at the same time. Where there is no violation of state sovereignty but there is grave interference with EU companies’ policies, the EU would not be able to use the ACI.

Under this option, the EU would define a set of triggers – third-country measures that, if they violate state sovereignty, could prompt the imposition of countermeasures under the ACI. For instance, it could define the ACI as covering punitive tariffs and trade curbs that violate state sovereignty. But Europeans should then add the coercive use of otherwise non-coercive tools to make sure that the ACI could adequately cover the forms of coercion that authoritarian regimes such as China and Russia have used in the past. This would cover the coercive use of anti-dumping or phytosanitary regulations – which can legitimise the use of economic restrictions in other situations.

There are several advantages to this option. Addressing grave cases of violations of sovereignty already gives wide scope to the ACI and ensures that it can respond to any coercive measure, economic or not, that seeks to alter EU policies. It would probably cover certain extraterritorial measures that gravely violated sovereignty. The instrument would also be easier to deploy – it is more difficult to assess the coercive quality of measures that do not target public authorities than those that are clearly aimed at governments and their policies. Limiting the use of the ACI to predefined triggers would also reassure member states that the EU could only take action under an ACI when such action occurs. Other EU tools – such as a new Blocking Statute that addressed not just US sanctions but also new Chinese practices not covered by the ACI – could provide additional protection and even countermeasures (such as asset seizures) against forms of coercion not covered by the ACI.

However, an ACI designed in this way would not cover one of the defining dimensions of economic coercion in today’s globalised economy, such as third-country targeting of private companies to de facto alter their home government’s policies. The ACI would not cover coercion of European governments that did not violate state sovereignty. And, because they did not represent sufficiently grave or direct interference with public authorities’ actions, the instrument would be unlikely to cover instances of pressure such as many popular boycotts and blocks on companies’ compliance with their home country’s legislation or exports of products to particular markets.

There is a danger that such an ACI could become yet another EU instrument that addresses the problems of the past rather than the challenges of the future. In the years to come, Europe’s adversaries – first and foremost China, but perhaps even Russia – could devise new forms of coercive action that are not covered by triggers the EU defines today. They may design these specifically to not cross the sovereignty threshold that the Commission establishes, or to not fall into the category of predefined triggers. With regard to the coercion of businesses, the ACI might be the most viable way to patch a critical vulnerability. As outlined above, it is only a matter of time before China leverages the centrality of its market much more to influence global trade.

Option 2: A tool covering more forms of economic coercion (rather than a set of predefined triggers)

The EU could make it possible to trigger the ACI in response to various coercive measures that are grave but that do not violate member states’ sovereignty directly (or, at least, not gravely). This means the EU could use the ACI somewhat more flexibly with a vaguer definition of economic coercion, not just a set of predefined practices that EU decision-makers identify today. The Commission and the Council could jointly establish that a certain act is coercive under the definition of the ACI and could, therefore, trigger countermeasures. The EU could combine anti-coercion action under its Blocking Statute – which seeks to block certain extraterritorial sanctions – and under the ACI. This would make it possible to impose countermeasures against, for example, Chinese extraterritorial measures. A reformed Blocking Statute could trigger countermeasures under the ACI against such practices under this second option.

The main advantage of this option is its flexibility and, therefore, credibility. It would be difficult for third countries to design grave coercive measures that the instrument’s definition did not cover. The EU would also be sure that the instrument would remain relevant, even if the nature of economic coercion was to change. European companies might soon be in a position where they had no choice but to comply with Chinese regulations that significantly harmed them, Europe’s trade, or European policy. The instrument could be a response to Beijing’s next generation of instruments – which could leverage China’s increasing centrality in economic networks in ways not possible today – or to significant volumes of forced sensitive data transfers.

Option 2 also comes with challenges. The risks of protectionism and harm to the rules-based order associated with the ACI could become acutely important for the EU under this approach. It may also be hard to prove the coercive intent of measures that do not violate member states’ sovereignty. The EU would have to clarify the basis in public international law it is basing its countermeasures on – meaning that the instrument would be even more legally complex.

Option 1.5: A tool that contains a flexible resilience mechanism

The EU needs to ensure that its deterrent has enough scope to provide both flexibility and certainty. A combination of options 1 and 2 is possible.

The ACI could define triggers and restrict countermeasures to state sovereignty violations as outlined under option 1. But it could also establish a new flexible resilience mechanism that allows for an ad hoc ACI investigation and possibly countermeasures when the EU and member states agreed it was appropriate – thereby going beyond predefined triggers. The ACI framework regulation or a separate regulation under the EU’s common commercial policy could specify the details of such a mechanism. The procedure should not be too lengthy or complicated as, otherwise, the instrument would lose its deterrent effect.

Under this flexible resilience mechanism, the Commission could add particular third-country coercive actions to a regulation’s annexe through, for example, a simple delegated act. The Council or the European Parliament could stop the Commission from doing so. The annexe would specify which third-country coercive actions are not covered by the ACI’s predefined triggers but which could nonetheless trigger the ACI. This could include cases where coercive action has had a great impact on many companies and sectors, or where the third country has caused significant damage to critical European interests. It could also include cases where state-owned enterprises have performed the coercive acts and a third country claims it did not so itself.

The EU would only consider specific acts it added to the annexe, but would not be obliged to trigger the ACI in response to them. The EU would then launch the ACI decision-making procedure and only adopt countermeasures if EU member states agreed to do so (see section on decision-making below).

Countermeasures the EU could impose under the ACI

There are two basic requirements that countermeasures under the ACI need to fulfil. If they failed to do so, the risks of adopting and using the instrument might be greater than its benefits. The worst course of action would be for Europeans to create an instrument that was inadequate to tackling the challenges it was meant to address. The first requirement is for the EU to ensure it has a broad menu of possible countermeasures that it can deploy under the ACI. When faced with a concrete situation of economic coercion, the EU needs to be able to carry out a careful vulnerability assessment to help it decide which concrete actions to take. It will need a comprehensive list of countermeasures from which to identify the most promising and proportional ones.

The second requirement is for the countermeasures to be both effective and credible. The countermeasures should be effective in the sense that they need to have the potential to affect something that a powerful third country values. Otherwise, that country will not care about the EU’s countermeasures and will follow through with its economic coercion. And the countermeasures need to be credible in this sense that the EU could swiftly impose them. The EU’s current institutional shape is likely to limit the potential speed of action – unanimity requirements or the competencies of member states could damage the credibility of countermeasures.

The instrument should probably include several key countermeasures. The ACI could fail to meet one of the two critical requirements if it excluded any of the following countermeasures.

- Tariffs and trade curbs.

- Investment restrictions.

- Access restrictions to EU public procurement markets.

- Sectoral divestment and export controls.

The ideal scenario for effective and credible countermeasures under the ACI would be for the EU to establish its own version of the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC). This would be a centralised entity in Brussels that could identify and implement countermeasures fairly independently. But, as it would involve a transfer of member state competencies to Brussels via treaty change, it is unfeasible for now.

The EU’s odd institutional shape creates challenges. Europe has to find countermeasures that approximate OFAC measures’ effectiveness and credibility, but without building a European OFAC that would formally centralise sanctions capabilities. Nevertheless, the EU should try to approximate OFAC as much as possible. In any case, imposing tariffs and trade curbs as countermeasures remain strong options for the EU, which would have great credibility thanks to their centralised competencies in Brussels. From a credibility point of view, trade (as part of the common commercial policy) is, therefore, a promising area to look for effective measures. In theory, so is competition policy (where the European Commission has vast competencies).

However, Europe may not impress a country such as China (or even smaller powers) with threats of tariffs or trade curbs. One of the main lessons of Trump’s imposition of tariffs on China was that the US did not succeed in significantly altering China’s behaviour through such measures. As such, it is unclear whether an EU tariff or trade curb would be effective. This is why the EU needs to think about adding countermeasures to the ACI that it does not think of as intuitively as it does trade measures. In identifying these additional countermeasures, the EU should start by assessing its bilateral relations with a third country and that country’s main strategic as well as short-term concrete interests in a given sector. One critical lever for Europeans could lie in withholding certain types of investments (and technology transfers) or critical products that a third country wanted to enter its market (see below).

That being said, the EU lacks credibility in the sense that, currently, other powers would be unlikely to believe that it would actually withhold these things. This is because competencies might sit (partly) with member states, or because Europeans would need to assemble a coalition of the willing to impose countermeasures.

Europeans need to make sure they reflect this tension between efficacy and credibility as they design their ACI. They should give thought to the following elements of the ACI and the process around it.

Investigation

Opening an investigation into third-country coercive behaviour could enhance the instrument’s deterrent effect without causing direct damage. It may be that, when faced with the consequences of its coercive action, a third country will withdraw its coercive measures. But this only works where coercion cannot achieve its goal quickly and if the EU appears likely to impose countermeasures.

The following is a list of possible countermeasures the EU could impose, selected from a much longer list of theoretical options because these are some of the most feasible. All of them have advantages and disadvantages.

Countermeasures

Category A: Countermeasures that have little legal complexity, as they would curtail benefits the EU grants voluntarily

Regulatory countermeasures

The mere threat to withdraw an EU equivalence declaration would have a great deterrent effect. Such measures would make the EU credible, but they could well come with too much risk. Regulatory countermeasures would leverage the power of the EU’s market like few other instruments. The European Commission attests equivalence of regulatory regimes in financial services and thereby facilitates the operation of third-country financial institutions in the EU by reducing overlapping compliance requirements. Equivalence does not automatically entail a waiver to obtain a licence to operate in the EU (except in some cases), but taking equivalence status away from a third country could be very costly to it. However, such action could prompt retaliation, such as the withdrawal of licences for EU-based banks in third countries. It would also erode the EU’s regulatory power by overly politicising technical decisions, and could harm the EU’s credibility as a pioneer of fair and transparent regulatory policy.

Restricting access to the European public procurement market

This could limit access for goods, services, and companies from non-members of the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA) and those countries that do not have relevant free-trade agreements with the EU. The GPA does not cover China, Russia, or Turkey but does cover the EU, as well as the US and 20 other countries. The EU could, therefore, impose restrictions on public procurement markets without violating its international obligations. Rules about public procurement are also included in several of the EU’s free-trade agreements, but this does not concern the EU’s relations with China, Russia, or Turkey. However, all three have benefited from access to the EU public procurement market, which remains one of the most open in the world. For instance, in the last ten years, Chinese companies have won €4.5 billion in EU public procurement projects. The EU has potentially useful leverage here.

Even for countries that are party to the GPA, there should usually be room to apply restrictions, given the EU’s general overcompliance with international commitments in terms of the access it grants foreign goods, services, and companies to enter its public procurement market.

The EU is currently working on an international procurement instrument (IPI), which would allow it to add a price-adjustment mechanism to tenders from countries that discriminate against EU companies in their own markets. But a trigger would be different in the ACI, as the EU would be responding to economic coercion, not to the lack of reciprocity in market opening. Still, for the IPI as for the ACI, public procurement restrictions could be coordinated at the EU level and initiated by Brussels, even if the Commission would have to consult closely with member states in doing so. The main problem with this countermeasure is that the EU has been using its leverage mostly to encourage others to open up their public procurement markets to Europeans; this might be harder to achieve if the EU started restricting access to its own market.

Exclusion from EU programmes

This would not be sufficient for an effective ACI deterrent in many situations: it will likely only be effective with countries that tend to rely strongly on participation in the EU’s research programmes, such as Switzerland, Norway, Israel, and the UK. A dozen countries are currently negotiating association with EU research programmes. But these include mostly the EU’s neighbours and only a small number of non-European countries, such as Canada, Japan, Australia, South Africa, and Brazil. Still, the EU has successfully used such an instrument against Switzerland before.

Category B: Countermeasures that could be more difficult to implement legally because they might only be allowed if a third country has actually violated international law. (The EU would still need to make a legal assessment on each occasion.)

Tariffs and trade curbs

Under this option, the EU would impose a retaliatory trade restriction, just as it does in trade defence. This could include imposing fees on the cross-border provision of services or blocking trade in services.

This option’s advantages include: the extensive experience that the EU already has in this area; the fact that the Commission would be acting in an area of centralised competence at the EU level; and third countries’ tendency to take EU trade restrictions seriously. But this option’s main disadvantages might be that many of these trade measures also impose costs on the EU’s own economies, and that the EU could end up in a stalemate, with higher tariffs and economic coercion still in place. There are also important legal questions that the EU would have to clarify: trade countermeasures could be illegal in principle under WTO law and only legitimate as a reaction to a violation of public international law by the coercing third state. The violation of public international law would have to be clear. The EU would have to choose measures carefully on a case-by-case basis.

Investment restrictions

With this option, the EU could also toughen investment provisions or even limit profit reallocation to the home country. The latter act could be an especially powerful and credible measure. But Europeans will need to be careful to comply with the different obligations towards specific partners, such as those contained within bilateral agreements on investment. For example, investor-state dispute settlement provisions grant foreign investors the right to access an international tribunal to resolve investment disputes. The EU also relies more on global openness for foreign direct investment than other major economies. It might lose more in a tit-for-tat escalation.

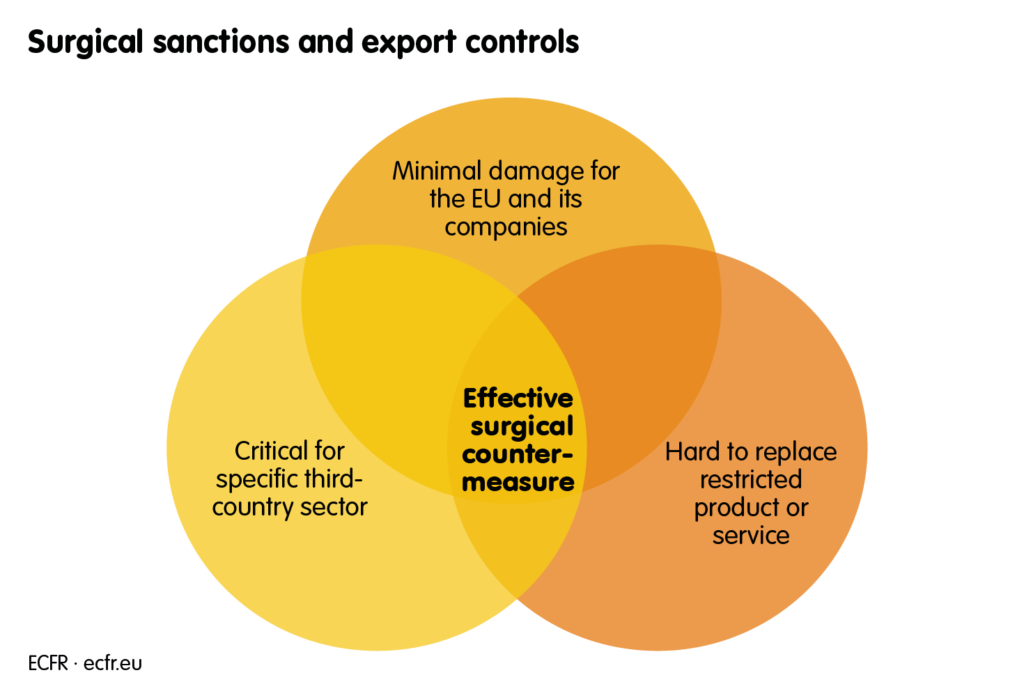

Sectoral divestment and export controls

Export controls could be one of the most strategic and effective ways for the EU to protect itself from economic coercion. The EU could restrict investments in certain sectors (such as tech transfers to China) or cut a third country off from a highly specialised product that it cannot easily replace. Even here, the room for effective action is limited, but there are some sectors in which the EU might have an important technological advantage or benefit from a trade asymmetry vis-à-vis a third country. In these areas, the EU could threaten a surgical countermeasure that blocked or curbed exports of a certain product where this would not cause great damage to the EU or its companies, where the relevant third country could not quickly replace the product, and where the product was a key component for (a range of) critical economic undertakings.

But the EU decision-making process needed to impose this countermeasure would be complex and would weaken the EU’s credibility. The Commission (and its potential EU Resilience Office) would first have to launch an investigation into the alleged coercion and conduct a vulnerability assessment. During the assessment, the EU should consult closely with member state governments to determine whether withholding a specific good or service from the coercive third country would be the most effective reaction, or at least part of it. The Commission could recommend (in a non-binding statement) the imposition of export controls. Even the Commission’s recommendation to pursue this option would have an initial deterrent effect. This would then be taken up under the procedure for amending the list of dual-use items already subject to EU export controls where the Council (by qualified majority vote) or the European Parliament could stop it from doing so. But, if they did not, the EU would add a very specific product as a surgical countermeasure.

This procedure does not come without legal complexities and potential political obstacles but, with sufficient coordination, it could be a highly effective tool for countering coercive measures. And, even if the procedure at the EU level fails for some reason, the close consultation with, and specific recommendation to, member states might, after all, still incentivise a smaller group of member states to impose export controls on a national level, as part of a coalition of the willing. This could still be a credible and highly effective countermeasure.

Likewise, the same procedure could be envisaged for proposing sectoral sanctions for divestment. After an initial investigation under the ACI, the EU could propose such sanctions to the foreign affairs council, which could adopt them by unanimity or where member states form a coalition of the willing. That said, the latter option would break with a key EU tradition of adopting sanctions jointly.

Counter-sanctions

In theory, the EU already has the power to adopt counter-sanctions on third-country entities in response to economic coercion. But doing so would require a significant break with the EU’s sanctions policy tradition – namely, that the EU only sanctions those responsible for an activity it regards as illicit. Importantly, while this would be an effective countermeasure, few would believe that the EU would really adopt it. Doing so would require a unanimous decision of the EU’s foreign affairs council. Therefore, adding countersanctions to the ACI would change little.

Cost and compensation

Such EU countermeasures will likely impose costs on European entities, even if the options are well designed. But the whole point of an ACI is to make it less costly overall for the EU to impose them. Still, countermeasures, including those that are cross-sector, could have collateral effects on businesses in sectors or member states that are not concerned by the original third-country coercion, or where the political mood does not accord with the anti-coercion action taken by the Commission. The EU could consider offering compensation (financial or non-financial) to European economic sectors asymmetrically hit by its countermeasures. Because the EU would not be able to provide anywhere near full compensation for losses, it should focus on those cases that are particularly grave. But just the symbolism of such possibilities would go a long way towards fostering the kind of EU solidarity that is needed for collective action in the face of economic coercion by other players.

The decision-making process for imposing countermeasures

The right amount of flexibility for Brussels

The ACI needs to give the Commission sufficient flexibility and authority to issue trade and investment countermeasures. EU member states need to have a say in the imposition of countermeasures under the ACI. This is not least because the Commission would be using the ACI to impose countermeasures based on international law, not trade law. This means that it would be member states, not the Commission, that would be obliged to defend the EU’s measures before the International Court of Justice if they were challenged by a third country.

But if policymakers design a framework that is too tight – with the aim of reducing uncertainty – or if they attempt to specify what the Commission can and cannot do in detail, the instrument would lose its deterrent effect. The EU would not be able to employ it in a swift manner, or would only be able to do so in certain cases, or only in a way that is unhelpful in a certain situation of coercion that legislators did not foresee when they constructed the tight framework. To counter third-country measures, Europeans need to gain sufficient flexibility and be mindful of their commitment to rules, EU unity, and the certainty of market access that other countries seek.

The ACI will generally be a tool under the EU’s common commercial policy. Some countermeasures would need a somewhat different decision-making procedure. But, for most cases, the EU can consider the following options for imposing the countermeasures:

Trigger mechanisms: Four options

- Giving member states a vote: the Commission proposes an implementing act to impose a countermeasure. Member states can stop the measure with a qualified majority vote (QMV), and another QMV in an appeal committee.

- The tougher the countermeasure, the greater member states’ involvement.

- No automaticity: the Council would implement through a QMV, so should take a decision itself. The Commission could still propose concrete measures.

- A Commission trigger that member states could stop: the Commission moves to impose a countermeasure, but just one-third of member states could require a Council vote within ten days. If they did so, approval by QMV would be needed.

➔ Recommendation: Option 2 or option 3

Option 1 provides for a qualified majority vote. But, ultimately, imposing countermeasures under an ACI is a highly political act: member states should probably have more ownership and control over the process – which option 3 provides. The downside of option 3 is a possible loss of deterrence if it is unclear whether the EU would act swiftly if the Council implemented countermeasures. This could be addressed by option 2, which still provides for member state ownership and control but gives the Commission more flexibility in imposing lighter countermeasures.

Option 1: Give member states a vote in an examination procedure

In this arrangement, the Commission would propose an implementing act to impose a countermeasure on a coercive country. This would give member states the opportunity to stop the Commission with a qualified majority vote if they disagreed with the proposed countermeasures or with imposing countermeasures at all (because, for example, they did not think it was in the EU’s interests to act in a particular way in a specific situation). The Commission could then engage with member states and take the implementing act to an appeal committee of higher-level member state representatives. If this committee voted against the implementing act by a qualified majority again, the Commission could not act. Otherwise, it could.

Option 2: The tougher the countermeasure, the greater member states’ involvement

With this option, the ACI framework regulation would give the Commission the opportunity to impose lighter countermeasures, such as exclusion from EU programmes or restrictions on EU procurement markets, with little involvement of member states. But, for the Commission to impose heavier countermeasures, such as trade and investment measures below a certain trade volume, it would have to secure greater agreement from member states. Where the countermeasures proposed are more extensive, the Council would have to trigger them.

Option 3: Introduce a Council trigger

Under this arrangement for the ACI, it would be down to the Council to trigger the imposition of any countermeasure. The Council would do so based on information from an investigation into the coercive measures imposed on Europeans. This information could come from, for example, an EU Resilience Office. The Commission would be the enforcer of the countermeasures, but it would probably propose the countermeasures to the Council – based, for example, on the information from the EU Resilience Office. The Council would decide to impose countermeasures by qualified majority and, in exceptional cases, would gain implementing powers. This could be justified, given the importance of the instrument and countermeasures. However, this option means the application of measures would be less automatic, and could be slower and have less effect as a deterrent.

Option 4: Introduce a Commission trigger that member states could stop

This arrangement would see the Commission move to impose countermeasures against economic coercion through an implementing act. The Council would then have ten days to act should it wish to stop the measure. If it chose not to respond, the framework regulation would allow for swift implementation by the Commission. But the Council could force a vote on what the Commission intended to do if requested by just one-third of member states, representing one-third of the EU’s population. In such a case, the Council would have to vote by qualified majority in favour of the Commission’s proposed countermeasures. If it did not, the Commission could not implement the countermeasures. If Europeans choose this option, they would have to define a type of procedure for implementing acts that is different from the one currently in the EU’s comitology regulation.

The context of foreign policy

Imposing or threatening countermeasures under an ACI would have foreign policy implications. These considerations should play a role in the imposition of countermeasures (or any threat to do so).

The Commission is already obliged to conduct the common commercial policy in this way under the EU’s trade policy, which the ACI would fall under. As a Commission vice-president, the EU’s high representative would be in the loop on the EU’s economic coercion policy. But, this aside, as the institutional actor entrusted to link the Commission with member states, the high representative could play an important role in building the necessary political ownership of the EU’s economic coercion policy. Were the EU to consider activating the ACI, it would lead to exchanges in the Council in which the high representative’s role as vice-president could prove useful.

Risks

The ACI comes with significant risks. These are real, and there is a danger that the EU could adopt a new instrument that ends up doing more harm than good.

Would the ACI harm the multilateral rules-based order?

Firstly, the instrument could undermine the multilateral rules-based order if Europeans lacked a detailed justification and explanation of the legality of the instrument under international law. Without a convincing legal basis, the ACI could easily violate international law. Moreover, third countries could try to establish a narrative that the EU was acting unlawfully even though the bloc remained fully committed to the WTO system, international law, and the rules-based order.

A hasty reaction from the EU, enacted without sufficient evidence, could harm the credibility of EU policy both outside and within the EU should its actions be perceived as unfair or disproportionate. This would be an own goal for the EU at exactly the moment when there is new hope for stabilising the global trading system with the new US administration and the new head of the WTO.

Would the ACI be too economically costly?

Secondly, the instrument could be counterproductive if it was poorly designed, either because it would inflict an undesired cost on EU companies and economies without necessarily achieving its objective, or because it would lead to a dangerous escalation of measures and countermeasures, thereby leaving the EU in an even worse position than it began in.

If the EU imposed certain countermeasures under the ACI, this could have a significant economic impact on European trade and businesses, and there would inevitably be side-effects due to the complexity of global value chains. Other trade-defence tools may serve as a warning: some empirical studies have shown that, when the EU protects companies through anti-dumping measures, the overall cost for society is more than four times higher than the gain for the sector in question. Moreover, the instrument might affect relations between the EU and other countries more broadly. A third country might respond to the EU’s countermeasures with further coercive measures: China could further weaponise access to its market for key European exports; the US could threaten to withdraw intelligence support in areas where Europeans lacked capacity, such as those where European privacy laws make intelligence work more difficult.

Would the ACI create a moral hazard?

Thirdly, there is a risk that the instrument could create a moral hazard in some situations. For example, the existence of the instrument could encourage certain companies to take bigger risks, as they could assume that, if they ever got into difficulties, they could draw the entire EU and its market into the confrontation. They might be tempted to choose a more hazardous path and adopt strategies that count on such an outcome, dragging European public authorities into disputes and conflicts that could have been avoided in the first place. There is no guarantee that this would happen, but it cannot be ruled out. Small and medium-sized enterprises might be particularly concerned that they would pay a disproportionate economic price for confrontations initiated by bigger companies, which tend to have greater access to decision-makers.

The issue of moral hazard also relates to a hypothetical compensation mechanism for EU companies, which could be introduced alongside an ACI. It would probably not affect their investment decisions more broadly but, in some cases, it could encourage risky bets.

Would the ACI encourage protectionism?

Finally, there are concerns that the instrument could be hijacked for protectionist purposes – or, at least, that it could dangerously shift the EU’s focus from trade openness to trade defence. This could be especially true if the instrument was triggered by something that happens to a private company, and not just when public authorities in the EU or its member states are targets of economic coercion. This could then give rise to concerns about equal treatment and non-discrimination.

Mitigation strategies

The risks of adopting an ACI are real, but the EU needs to judge them against the instrument’s benefits and the costs of not having such a tool.

Should the EU choose the course of inaction, this would be not just dangerous but would also invite further trouble. The path not taken could encourage Moscow and Beijing to step up their use of economic coercion vis-à-vis the EU. They might continue to see such activity as low-hanging fruit: an opportunity that involves little risk but could have great rewards.

Similarly, while there are justified concerns about the compatibility of the ACI with the EU’s WTO commitments and goals, it would be wrong to believe that the lack of a deterrent would have no negative consequences for the WTO. On the contrary, one can already see how the multilateral framework is being undermined – with the trivialisation of the national security exception, which is used to justify trade restrictions or sanctions, and with controversies concerning recent case law (such as the 2019 ruling on Russia and Ukraine) confirming the WTO’s right to review national security claims. The ACI could complement and reinforce the multilateral framework, as it could be used in areas where WTO rules are irrelevant or ineffective – or where the EU might prefer to stay outside the WTO’s remit. All in all, the question here is not what is harmful and what is not, but what is less damaging for the WTO: developing a new tool or pretending that the status quo is fine.

To be sure, the EU needs to put mitigation strategies in place to limit the risks of the ACI. These would allow Europeans to minimise the danger that the tool will backfire. Still, Europeans would need to decide which of these mitigating strategies are necessary: the more Europeans try to mitigate various risks, the more the instrument could become toothless or complex.

How to avoid harming multilateralism

The international rules-based order remains a cornerstone of public policy across the EU. However, Europeans are divided on whether the bloc’s status as a chief proponent of multilateralism should prevent it from developing an anti-coercion tool. If this is a difference between idealists and realists, the latter might respond by paraphrasing a Latin proverb: if you want trade, prepare for trade war.

Basing the ACI on international public law should ensure its legality, thereby empowering the EU to use a wide array of measures, including those related to trade. The danger that others will challenge the EU at the WTO is limited, as they would risk setting a precedent for what counts as economic coercion in the first place, which is not in their interest. Besides, with an ACI, the EU could defend and strengthen the multilateral framework – just as it would find itself in a stronger position to engage others on unblocking and reforming the WTO. In this sense, the ACI would have both a strategic and tactical function.

Still, to mitigate any concerns about legality, the EU should consider the following points.

- The EU could limit use of the ACI to instances where public authorities – not businesses or NGOs – are targets of economic coercion. A mechanism to include new forms of economic coercion could ensure both flexibility and legality (see earlier section on scope).

- The EU needs to ensure that the ACI is compliant with international law – and that countermeasures considered by the EU comply with bilateral commitments vis-à-vis different partners.

- The EU should design the decision-making process in a way that the instrument is not used in a hasty and unprepared way, thereby mitigating the risks for the EU’s credibility.

- To avoid any risk of a WTO challenge, the EU could favour, whenever possible, measures outside the WTO’s core realm (non-trade measures, as well as those that are not fully regulated by the organisation, such as those concerning trade in services, public procurement, or intellectual property rights). Nonetheless, this approach would significantly limit the EU’s options.

How to address the risk of economic costs

The right kind of deterrent would focus on implementing a reciprocal countermeasure where the other side has an even greater interest that it does not want to lose – such as, for example, by exploiting China’s reliance on some knowledge transfers from the West. Still, the EU cannot rule out the possibility that its measures would impose some costs for Europeans. Europeans would need to be ready to accept at least some pain. The EU cannot rule out escalation either, but a credible ACI could also deter third-country economic coercion altogether and have a significant de-escalation effect.

Still, to mitigate concerns about economic costs of the tool (and its distributional effects, as the damage would rarely be spread evenly across the EU and its member states), the EU should consider the following points.

- Favour, whenever possible, measures that are costly for a third country while keeping costs for Europeans at a minimum (see section on countermeasures).

- Consider obliging decision-makers to consult with businesses likely to be concerned by its countermeasures.

- Consider giving some compensation to EU companies to redress asymmetric effects – although this idea would likely generate other concerns, such as those about moral hazard.

How to limit moral hazard

To mitigate concerns about moral hazard, the EU should consider the following points.

- The ACI decision-making process would need to ensure that the tool is activated in cases of grave economic coercion only.

- Compensation, if envisaged, could be limited to specific instances. It is important not to allow businesses to gain any feeling of entitlement, while recognising that the consequences of the EU’s countermeasures may be uneven across EU member states, sectors, and companies. And compensation should not be automatic but rather be granted in light of the overall context the relevant companies operate in.

- At the same time, the EU could choose to be restrictive in including private sector coercion within the scope of ACI – to avoid the risk of the EU or its member states being dragged into purely commercial conflicts. This does not preclude addressing such cases under the ACI through a new blocking mechanism (see section on scope).

How to limit protectionist temptations

The purpose of the ACI is to fill an important gap in the EU’s defences, not to become its chief trade policy tool. It is no silver bullet even for responding to economic coercion, but is needed as part of a broader toolbox. Besides, a credible deterrent would help the EU pursue a trade policy focused on promoting openness and the rules-based order and de-escalation. Blindly relying on free trade in the face of economic coercion would be little different from letting the policy be hijacked for protectionist purposes. In either case, the EU would privilege particular economic interests over its broader concerns, such as its long-term security.

Still, the EU should only establish an ACI if it can put in place an ambitious strategy to mitigate the risk of protectionism. For this, the EU should consider the following points.

- Last resort. As a safeguard against the overuse of the ACI, the decision-making process might need to ensure that the instrument is activated only in grave cases and where there is a clear breach of international law.

- The EU could impose a time limit, as well as a review requirement, on countermeasures.

- The Commission might need to report to the European Parliament, especially for review. The Commission would have to show that its measures were not protectionist, assess the success or otherwise of the measures, and outline why it believes that it is still justified to take or uphold the measures rather than an alternative course of action.

- At the same time, the EU could make a political commitment to ensuring the ACI was accompanied by a positive agenda (see the introduction). The EU’s open economy is crucial for its economic power, global reputation, and security – but, on its own, this economy is currently not enough to defend the bloc against economic coercion by other great powers.

Conclusion: A depoliticisation instrument

The EU should ensure that, unlike some third countries, it does not contribute to the politicisation of trade through the creation of more geo-economic tools. Europeans are facing a dilemma: should they aim to become as skilled in the art of weaponised interdependence as other great powers? Or should they stick to their commitments to free trade and the rules-based order, trying to establish an international framework instead? Pursuing the latter option would allow the EU to contain and neutralise economic coercion – preserving global economic integration.

The EU could, of course, try to patch its critical vulnerabilities without adopting an ACI. For instance, Europeans could set up a sizeable compensation fund to incentivise companies to engage in trade they would otherwise shy away from (out of concern that the EU would be unable to defend their dealings against third-country coercion). State help was critical in redirecting Australian companies’ sales when Chinese coercion hit them. Europeans could also decide not to fill the gap in their defences if they believed that the cost of submitting to economic coercion is lower than the cost of being able to impose countermeasures, of possible retaliation, and of damage to the international trade system through coercion. And it is true that the most important and potent responses to economic coercion are to build Europe’s own economic strength and innovative capacity, and to promote a positive trade agenda that removes obstacles and diversifies relations.

As the ACI comes with real risks, the decision about whether to establish it is not straightforward. But, if the EU decides not to do so, it should know that this could risk damaging international rules-based trade in this new era of geo-economic competition. Inaction can be provocative and politicising, too. This course of action would come with great cost, as other world powers would have stronger means of shielding themselves from economic coercion.

Europe needs to attempt to both become more skilled in geo-economic competition and to stick to its commitment to the rules-based order. This is possible if Europeans construct not an anti-coercion instrument, but a depoliticisation instrument. This could function in just the same way as this paper has outlined for the ACI. The goal of the ACI should not be to punish third countries; it needs to be purely reactive. The EU should aim to reverse the widespread politicisation of economic interdependence. The instrument would aim to trigger negotiations and dialogue instead of blackmail – and, for this purpose, it would include a clear and swift mechanism for lifting countermeasures once a third country ceased its coercive actions and entered into dialogue with the EU. The ACI could be a mechanism for de-escalation and change.

A mechanism for the swift removal of countermeasures

As the EU has experienced in previous trade disputes, countermeasures do not easily lead to the resolution of a conflict. Indeed, they can often remain in place for some time – even if both sides would like to lift them, as is currently the case in transatlantic relations.

The EU could avoid this with a mechanism that guaranteed the swift removal of countermeasures. The bloc could do so in the following ways.

- Rapidly impose EU countermeasures, which a high-level European representative would immediately follow by engaging in consultations with the third country – with a clear offer to swiftly withdraw them upon the cessation of coercive activities.

- Impose light EU countermeasures, which a high-level European representative would immediately follow by engaging in consultations with the third country – with a clear offer to swiftly withdraw them upon the cessation of coercive activities, or to impose full EU countermeasures if the talks fail.

- Swiftly remove countermeasures. To make this technically possible, the EU would need a simplified decision-making procedure. For instance, if the Council implemented countermeasures, the Commission could lift them unless the Council forced a vote.

Combined with effective and credible countermeasures, but also with a clear depoliticisation mechanism, the new instrument would be a powerful deterrent at the EU’s disposal.

If Europeans chose to adopt it, their decision would send a powerful signal to the world that the EU was determined to defend international rules – not just in rhetoric but also by countering coercive practices. Are Europeans ready? We will soon learn.

About the authors