Germany votes: European dilemmas in the Federal Election

Summary

The European Union that Germany and its partners have built together since the early 1990s has been an environment highly conducive to German interests.

With the United Kingdom and the Trump administration calling into question the EU model of regional order, Berlin has made a strategic choice to seek to strengthen the EU. It has started to build coalitions of partners around core policies in a more “flexible union”.

In this federal election year, trade and the German export surplus, relations with Turkey, and relations with Russia, constitute three examples that illustrate the complex interaction of domestic, European and international levels.

Keeping the public happy, strengthening the EU, and maintaining an environment conducive to German interests, requires careful policy calibration by the current and future government.

Polls reveal a hidden reservoir of public support in Germany for greater European ambitions. But Germany needs to be open to compromise on core policies, and should be prepared to take greater risks in order to secure the EU’s future.

Introduction

Shortly after the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union, a policy brief by the European Council on Foreign Relations argued that Germany should put more resources into building coalitions inside the EU. It said that Germany should protect itself from the risk of isolation, and prevent the union from disintegrating further.[1] This need to invest in EU cohesion became even more pressing in the light of the American presidential election in November 2016: in a widely read interview with the German daily tabloid Bild just days before his inauguration, Donald Trump called the British decision “smart”, and predicted that other member states would follow suit.[2]

The spectacle of Europe’s strongest ally, the United States, calling into question the value of the EU as a regional order suggested a looming fundamental shift in transatlantic relations. As for Germany itself, such comments shook the foundations of its postwar policy orientation – and not only in foreign policy. After all, the EU that successive German governments have built together with their European partners since the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 has developed into an environment highly conducive to domestic German interests.

Over the past decade there has been a solid majority for investing a great deal of energy in keeping the union together. The political class in Germany continues to be well aware of the benefits of EU membership. Yet, despite the preponderance of German power and strength of belief in the value of the EU, policymakers in Berlin have not yet managed to translate this into a restrengthening of the union at one of its most vulnerable moments ever. These weaknesses stem from the unfinished business of reforming the architecture of the single currency, growing pressure on the migration and asylum system and European security, and tendencies in a number of EU countries to ‘put the nation state first’.

This policy brief explores how Germany responds now that the favourable environment created by the combination of the EU and the transatlantic alliance is jeopardised. Is Berlin seeking to rescue that order? What is Germany’s vision for the future shape of Europe? How much further is Berlin willing to go in its commitment to European integration – and to what extent will the German government risk confrontation with Britain, the US, and other countries along the way? And, finally, what does it take for Berlin to start turning its back on the EU model in its current shape, and look for new ways of organising the European continent?

Can Germany manage to keep its public happy, strengthen the EU, and maintain a favourable international environment – all at the same time?

This analysis is conducted at three interacting levels. First, at the domestic level, because Germans are heading to the polls in September this year to vote for a new federal parliament and government. In 2017, therefore, German public opinion will weigh particularly heavily on the minds of policymakers. While the German public has happily consumed the benefits of membership, it so far appears to have shown less appetite for investing in securing the EU’s future. If Berlin wants to make bolder moves at EU level to save core functions of the union, politicians will need to secure the permission of the German public.

The second, European, level is equally tricky: Germany is in a position to exercise leadership, but it needs others to play ball too. Currently, member states are divided about how to respond to Europe’s challenges – despite the willingness to cooperate declared by 27 EU members as they celebrated 60 years of the Treaty of Rome in March 2017. In particular, the future direction of France is vital to Germany, and to the EU at large. Now that Emmanuel Macron has won the race for the Élysée there is a sense of relief in the German capital. But his vision of restrengthening the EU around a Franco-German core is complicated by the prospect of a divided legislature, as France heads to the polls for its own general election, and by a German public seemingly reluctant about Macron’s vision for eurozone reform.

Third, several pressing international issues pose problems that cut to the heart of Germany’s core national interest, and indeed identity. This paper contains three case studies on some of the thorniest questions currently facing the country: international trade under Trump and the debate around the German export surplus, the future relationship with Turkey, and the relationship with Russia. All three resonate strongly in the German domestic arena, and how these play out in the federal election will also influence Berlin’s action at the international level.

The trilemma, then, for Germany’s current and future leaders is: Can Germany manage to keep its public happy, strengthen the EU, and maintain a favourable international environment – all at the same time? Interestingly, despite the strained context, the atmosphere in Berlin at this crucial time is not one of headless chickens. Indeed, in times less stormier than these, transatlantic affairs, in particular, caused severe headaches and a deep sense of disorientation in Berlin – for example, the previous US administration’s ‘pivot to Asia’. Now, though, there appears to be a confident attitude of ‘taking the bull by the horns’, coupled with a sober assessment of Berlin’s options, and a new ‘risk-taking’ element to Germany’s pursuit of its own interests.

This paper explores the new dynamics in Germany’s relations with its European partners, with the United States, and on contemporary European questions. It draws on ECFR’s own research, using data from the ‘Future Shape of Europe’ research (March 2017), and ECFR’s EU 28 Survey 2016.[3] It identifies the kind of European future that policymakers in Berlin are formulating, and explains the domestic debates surrounding the main foreign policy themes in the federal election campaign.

Hedging against disintegration, pushing for new coalitions

“I believe we Europeans have our destiny in our own hands”, responded Angela Merkel, during a press conference when quizzed about President-elect Donald Trump’s comments to Bild on the further disintegration of the EU. “I will continue to invest in the 27 EU members to closely cooperate”, she added.[4] In all its simplicity, this phrase reflected a clear strategic choice. Berlin knows from its latest interactions with London and Washington that in both capitals there is both a high degree of unpredictability, and fundamental differences with Germany in terms of outlook on European and global affairs. The federal government also knows that it has limited resources to directly influence behaviour in the UK and the US as both capitals undergo periods of transition. Instead, Berlin believes that improving the cohesion and performance of the EU and its member states would improve its leverage the most. Berlin does not shy away from interacting with the UK and the US on core issues, at times even confronting both. But the German federal government has invested by far the most energy in re-engaging its EU partners, and strengthening the cohesion of the EU 27.

The federal government holds few illusions about the difficulty of this task. Even before the UK referendum and the prospect of disintegration, the union looked weak. Germany too appeared unable to make its influence count, failing to mobilise a joint European response to the refugee crisis. For Berlin, that time was an exceptionally lonely moment. But instead of responding to calls to be the ‘new leader of the free world’, Merkel renewed her government’s commitment to keep strengthening the EU.[5]

Berlin does not shy away from interacting with the UK and the US on core issues.

In the aftermath of the Brexit referendum, the chancellor, along with other key ministers of her coalition government, went into enhanced listening mode, undertaking an extensive tour of European capitals as well as meeting member states in Berlin. The prospect of the European order crumbling generated new political momentum in Berlin and elsewhere. In fact, it has created new space for cooperation.

The renewed discussion around the potential of a more ‘flexible union’ proposed by Berlin and other key European capitals is part of an attempt to breathe life back in to the logic of cooperation in the EU 27. The old concept of a ‘union of different speeds’ as a remedy against centrifugal forces gained some prominence again with the Declaration of Rome adopted in March 2017.[6] There, the leaders referred to “different levels of integration” and said that “some countries will go faster than others.” A hitherto largely academic debate has re-emerged with a vengeance. Talk revolves around ‘enhanced cooperation’, a ‘Europe of different speeds’, of ‘concentric circles’ and the like. But is it anything more than new wine in old skins?

The “union of different speeds”: nothing but a chimera?

“We will act together, at different paces and intensity where necessary, while moving in the same direction, as we have done in the past, in line with the Treaties and keeping the door open to those who want to join later. Our Union is undivided and indivisible.”[7] In this way the March 2017 meeting of the EU 27 made both a commitment to unity and a clear reference to a union of different speeds. The document reflected a carefully balanced compromise between member states as well as the EU institutions. But it also reflected the direction of travel agreed by core EU members Germany, France, Italy, and Spain when they convened in Versailles earlier that month to coordinate their positions ahead of the Rome meeting. They want to lead the union into the future by investing again in more ambitious policies. In their view these might have to be initiated by groups of member states in order to create political momentum for the union at large.

Nevertheless, new ECFR research shows, with very few exceptions, that EU member states still share the fear that moving at different speeds will accelerate disintegration rather than help the union out of its deadlock.[8] Berlin itself has traditionally taken a conservative approach to ‘different speeds’ – one based on the EU treaties, that protects the joint institutional framework and the interests of the union at large, and that is open to other members. Until recently, the German government was therefore very hesitant about even exploring ‘flexible’ modes of cooperation, as it has viewed these as undermining cohesion and leading to an even more complex legal and politically divisive environment in the EU.

However, the EU’s recent frailty has led the German government to reconsider its attitude towards flexible types of cooperation. There is a wide range of views among experts and officials in Berlin about the risks and benefits of different types of flexible cooperation. But, overall, there is now a readiness within the government to explore new ways of working together in order to achieve better collective results. Flexibility is no longer seen as contributing first and foremost to disintegration. Instead, after years of division on the euro, migration, and security, flexibility is viewed anew as something that can be used to show that working together does pay off, and that it can help overcome divisions. ECFR’s research shows that one of the main reasons for member state governments to embrace greater flexibility is that they believe that demonstrating the benefits of collective action can help build trust among citizens.

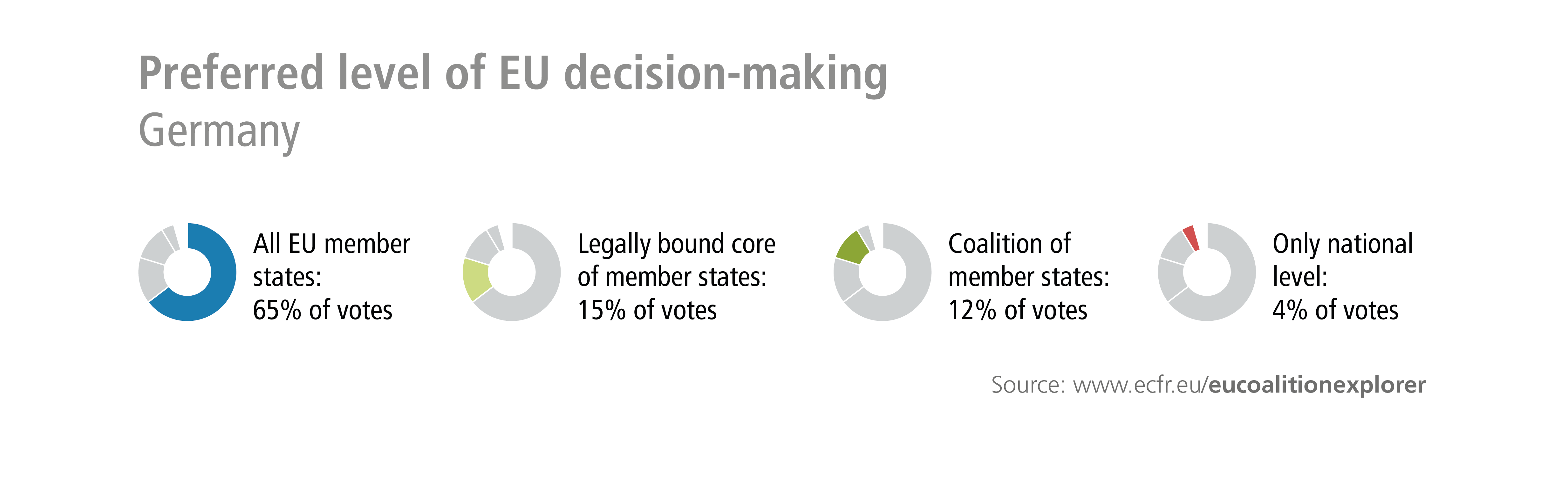

That said, it remains the case that a preference for working on a union-wide basis is stronger in Germany than elsewhere (see chart above). ECFR research from September 2016 shows that opinion among policymakers in Germany remains above the EU average, with 65 percent backing a union-wide approach compared to 52 percent across the EU.[9] Berlin is still more inclined than other big member states to work with ‘all’ member states. This preference shows not only the strong sense of responsibility in Berlin for keeping the union of 27 together. Across the EU it can also help build trust in the argument that Germany still has relatively little appetite for going it alone, or in small groups, as long as Berlin sees that it is possible to mobilise the whole range of member states. Berlin is concerned about the ‘laggards’ in scenarios of groups moving ahead. This is why, in the German view, a successful flexible union needs two things: careful management of the different speeds pursued by member states, and an atmosphere of trust between frontrunners and countries moving at a slower pace. Based on this overall preference for working with all member states, Germany will try to keep flexible Europe inclusive and prevent any exclusionary dynamic from emerging.

The German government has reconsidered its attitude towards flexible types of cooperation.

Focusing in on different policy areas provides a more nuanced insight into Germany’s attitudes towards embracing flexible modes of cooperation. On issues where Germany has a particularly strong national interest (such as better governance for the eurozone, or common defence) it is less ‘idealistic’ and more pragmatic, opting for a ‘flexible Europe’ approach in order ‘to get things done’.[10]

Against this background, the conservative approach of the March 2017 Rome Declaration is not necessarily a mirror of the realities in Berlin. While the Rome Declaration focused heavily on process – listing the well-known criteria for treaty-based flexibility – the debate is in fact focused on results. And the discourse in Germany is no longer first and foremost integrationist, aiming for ‘ever closer union’ – as was traditionally the case in Germany’s flexible union debate.

How have other countries in the EU reacted to this shift in tone and emphasis? EU members’ and institutions’ responses have been almost ritualistic: the small fearing the dominance of the large, the newcomers fearing being left behind, the small advocating for a strong role of the European Commission to protect their interests, the European Commission trying to keep a focus on treaty-based approaches. These reactive patterns look like member states seeking to reassure themselves and others that they are still part of the union that they have known. But something more radical seems to be happening in parallel to this ritual, something which points to a more ambitious vision emerging in Berlin about shaping policies among smaller groups of member states.

Germany’s finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, a member of Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union party (CDU) and a veteran of EU politics, recently published an article in the national daily newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.[11] The piece is remarkable because at first glance it appears uninspiring, and then turns out to be visionary. It is lengthy, but the author flies some interesting kites. On flexible modes of cooperation, Schäuble, who, as early as the 1990s, was venturing ideas about flexibility, thinks beyond treaty-based options:

Everyone who knows how Brussels works knows that changes to the Lisbon Treaty as EU primary law are unrealistic in the short term. […] But today the EU needs to strengthen its capacity to act in areas where even Eurosceptic parts of our populations acknowledge that going it alone as nation states won’t be enough. Insofar as [cooperation] is not possible on the basis of EU primary law because of legal and de facto constraints we need to move forward pragmatically, by means of enhanced cooperation or through intergovernmental cooperation, whatever we call this in respective cases: variable geometry, flexible speed, core Europe, or ‘coalitions of the willing’.[12]

The minister then goes on to suggest areas in which better results are needed in the short term – in particular, external border control and management, European security, and eurozone governance. Speaking about strengthening European defence, he raises the issue of the European Commission proposal for a joint European defence fund, and stresses that paying for it will have to come through national budgets, and that there should be more efficient spending in order to create greater synergies between European countries. So, while some EU observers have started to focus on the next round of EU budget negotiations (the current budget cycle will end in 2020) and predict that the new multiannual budget will become a major battleground between the member states, the real issue here is different. Schäuble, a pillar of Angela Merkel’s government, and a key figure in crafting Berlin’s EU policies, implies that there is a prospect of groups of countries deciding to set up new budgets (for example, for the eurozone, border security, defence). This would be a new logic, and a new phase of integration in which not all member states buy into key policies.

This would mean an important shift in the current EU budget practice. It would raise the question of whether this kind of flexibility could be the route to a new environment conducive to German interests and resilient against further disintegration. Commentator and former ECFR research director Hans Kundnani argued in a recent policy paper that the election of Trump could deal a blow to German power within the EU, as it means a new focus on security and defence, areas in which Germany is weak by comparison to the UK and France. Trump’s attacks on the German economic model could have a similar effect.[13] In such a scenario, the country which would be central to rescuing the EU would no longer be able to punch its weight. But for policymakers in Berlin, this is not what they are working towards – it would be defeatist to do so. For the time being, the government’s mission is to save the parts of the old order that work, and reform those that do not by exploring new ways of cooperating, if only in groups of like-minded member states. Both the CDU of Merkel and the Social Democrats of Martin Schulz, who is set to challenge Merkel in the battle for the chancellorship, are strongly committed to keep Germany engaged in the EU, and to use the union to leverage German power.

Berlin has good reason to be confident that such like-mindedness is slowly returning to core EU capitals. Because of Brexit and Trump, Europe’s choices are suddenly much more starkly defined, and have helped rally support behind EU membership, even among the most fervent EU critics in central and eastern Europe. The energy to drive this new phase of the union, however, remains clearly in the camp of members which share fundamental values and have a similar outlook on the world. To take the example of the ‘Versailles Group’ of France, Germany, Italy, and Spain, these countries have similar views about flexible modes of cooperation, and still agree about a strong role for the EU in issues such as external border management, security, and defence (where France traditionally has a different view, but wants to be part of any initiative of EU members).[14]

However, in order for this shared mode of cooperation to succeed, these capitals will have to agree on the substance of core policies, in particular with regard to eurozone reform and the EU’s future economic and social model. Will the glue formed by the new external pressure on the system be strong enough for leaders to overcome their differences? If core EU countries now drive forward the ‘Rome agenda’, such renewed political commitment could indeed encourage others to join. Flexible modes of working together, then, can also be interpreted as a vehicle to generate and maintain much-needed momentum.

For the time being, Germany has taken up the fight and is seeking to use its significant power and resources in the EU to shape the union for the better, and according to its preferences. The outcome of the French presidential election has been key in this regard. There is no doubt in Berlin that victory for Marine Le Pen would have required a fundamental rethink of Germany’s options. Whether it liked it or not, Germany would have been pushed towards securing its interests through looking more radically beyond the current EU framework. Macron, then, perhaps with a good dose of the benefit of the doubt, is seen as a partner in building a new kind of union by a broad range of parties in Germany, including by the governing Christian Democrats and Social Democrats.

Interestingly, with his views on the reform of the eurozone – a eurozone budget, finance minister, and parliament, as well as a legal framework for sovereign debt restructuring – Macron pushed the German government to take a position. For now, most of Germany’s leading politicians have been reluctant to map out in greater detail, and for a wider public, their vision for eurozone reform. These are potentially divisive issues in Germany, and are certainly sensitive subjects to address in an election year. Macron’s election has driven the debate in Germany, and senior politicians, including members of the federal government, and Merkel herself, have been prompted to respond to the calls for reform from Paris.

The question now is how open Berlin is to a Franco-German compromise on the eurozone.[15] In the immediate aftermath of the French presidential election, media coverage in Germany highlighted a potentially antagonistic scenario over the future of the euro between the new leader in Paris and his German counterparts, suggesting that Macron was crossing Berlin’s red lines, asking the Germans to pay for his vision to save Europe.[16] This was also the line taken by the Alternative für Deutschland party, which argues for Germany to abandon the euro.[17] By contrast, the federal government in Berlin chose to be openly responsive to Macron’s plans, referring to previous engagement with him on the subject.[18]

What, then, is the domestic context against which the federal government will have to take European cooperation forward? Is the German public willing to go along with deeper integration and new forms of cooperation?

European and foreign policy: What does the public think?

At first sight, the traditionally pro-European German public seems to be more Eurosceptic than ever before. A poll conducted by the Körber Stiftung in the autumn of 2016 shows that 25 percent of German citizens welcome the growing role of Eurosceptic parties, 42 percent want a referendum on EU membership, and 62 percent think the EU is going down the wrong path.[19] A poll by Infratest in March 2017 concludes that, since the Brexit vote, Germans seem to be even more sceptical of the advantages of EU membership.[20]

There is a hidden reservoir of public support for strengthening European cooperation, and even integration.

If one digs deeper into the underlying reasons for growing dissatisfaction with the EU, however, it becomes clear that there is no ‘EU fatigue’ among the majority of the German public. In November 2016, Eurobarometer showed that 77 percent of Germans generally identify themselves as EU citizens (the EU average is 67 percent).[21] Polls suggest that Germans’ critique of the EU boils down to the failure of EU countries to integrate further. According to a poll conducted by Ipsos in March 2017, only 32 percent of Germans feel the EU is currently going in the right direction. The Infratest poll from the same period shows that 78 percent believe ‘the right direction’ to mean ‘deeper integration’.[22] There is also a perceived lack of commitment on the part of other member states which leads to dissatisfaction among the German public: many Germans (73 percent) feel that Germany is being abandoned by other member states (particularly when it comes to refugee policy).[23]

When it comes to the EU, Germans believe their country has become a lonely leader. For many, a ‘protection reflex’ has kicked in because the EU is threatened: when Germans feel the EU is under attack they rally behind it. But there is a clear demand for reform as well. The picture that emerges suggests there is criticism of Europe among the German public, yet no ‘Europe-fatigue’. There appears to be a hidden reservoir of public support for strengthening European cooperation, and even integration.

Against this background, foreign minister Sigmar Gabriel recently tested an interesting message. Gabriel explored what polls tell him about the German mindset: That there is scope for bringing in citizens around the idea of greater investment in keeping the EU together. In an op-ed for Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung he argued that Germans need to stop obsessing over their high net contributions to the EU budget.[24] “The truth is that Germany is not a European net payer, but a net winner… Each euro that we pay into the EU budget multiplies and flows back to us.” He went on to suggest that Germany do something “outrageous” in the next debate about Europe’s budget: “Instead of fighting for a reduction of our financial contribution to the EU, we should signal our willingness to pay even more.” An EU disintegrating with Brexit, and under fire from Washington, clearly needs more commitment, and not just in words.

This is a foreign minister on the campaign trail, endeavouring to position his party as the progressive European force in the country, with Schulz as a credible messenger. But Gabriel’s message goes beyond campaign manoeuvring and his own party. In fact, it is a matter of national interest. The German economic and political model benefits greatly from the EU, and Berlin continues to believe that with the EU it can best contribute to shaping a world order that serves German and European interests at large.

The idea of a ‘flexible union’ floated in government circles, then, ties in with citizens’ expectations about delivering results, and the wish for greater cooperation. One thing is certain: While in the diplomatic environment of the EU members and its institutions, process is currently a major point of concern (see the debate at official EU level about the preferred types of flexibility as shown by ECFR’s Flash Scorecard), citizens are unlikely to care about any such detail, but rather focus on policy results.[25]

But things are not that simple. Beyond the overall solid backing that Germans give their government to ‘fight for Europe’, there are a number of concrete policy challenges creating headaches for the federal government. These are playing out in the federal election campaign itself and are creating a complex interaction between the national, European, and international levels. This is illustrated in three short case studies on: trade policy and the ‘surplus debate’; Turkish-German relations; and dynamics between Moscow and Berlin. These show how the mission to preserve a European and international environment conducive to the German interest touches upon Germany’s economic, political, and social identity.

Trade policy and the ‘surplus debate’

Sebastian Dullien

In the arena of international economics and trade, two issues are foremost for Germany: keeping its export markets open, and defusing international criticism of its large current account surplus – more than 8 percent of GDP in 2016.

Globally, there are two main challenges for Germany’s export markets. On a smaller scale, there is the question of Brexit, which endangers exports to Britain. On a larger scale, there are potential protectionist measures by the Trump administration, which might endanger not only the north American export market but threaten the global trading system too.

Germany's approach both to Brexit and a protectionist US are compatible with the interests of the other EU member states.

On Brexit, Germany in principle has an interest in keeping Britain open as an export destination (which is, with 7 percent of German exports, Germany’s third largest export market). Yet the rest of the EU single market is more important for the German economy than Britain, and the German government therefore has a strong interest in discouraging other countries from following Britain’s example. The government can thus be expected to maintain a tough negotiating stance towards London. The corporate sector has grudgingly accepted this argument and, no matter what the election outcome in Germany in September, this position will not change.

The bigger problem is the current US administration. During his election campaign, Donald Trump threatened to slap a tariff of 35 percent on imports from Mexico. Peter Navarro, one of Trump’s top trade advisers, has also singled out Germany for its large current account surplus. The German car industry in particular would be heavily hit by tariffs, both on car imports in general and on car imports from Mexico, as some of German ‘original equipment manufacturers’ produce in Mexico and deliver cars into the US.

Another potential problem might be corporate tax reform. Proposals by leading Republicans in Congress originally included the aim of changing the tax system to a cash flow tax with border adjustment. Under these plans, expenses for imports could no longer be deducted, while revenues from exports would be tax-free. Economically, this would be the equivalent of an import tariff and an export subsidy. While the initial proposals presented this spring by the White House do not include such a border tax adjustment, it is not entirely certain that the idea is dead for good. As lawmakers will have to look for revenue if they want to succeed in cutting tax rates, it is conceivable that a border tax adjustment will come up again in discussions.

Trump’s proposed tariffs would violate the rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO), as most likely would any tax proposal including border tax adjustment. The German finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, has already warned publicly that Germany would perceive such a tax reform as a violation of international standards. Should the US administration push ahead with any of these proposals, a trade conflict could be on the cards. In the case of a dispute over US corporate taxes, this could easily be the biggest case ever brought before the WTO. To protect its own industry, Germany would almost certainly press the European Commission to bring a case to the WTO.

In principle, the German approach both to Brexit and a protectionist US are compatible with the interests of the other EU member states. None of the member states has an interest in creating incentives for others to leave. None of the EU members has an interest in the US administration closing its market and ripping apart global trading rules.

Nevertheless, the risk of division between Germany and some of the other EU members remains. For example, in a trade dispute with the US, the Trump administration could throw other issues, not related to trade, onto the table. The Baltic countries might be vulnerable to blackmail if the US threatens to withdraw its promise to protect them against Russian aggression should they go along with Germany’s more aggressive stance against US trade measures.

When it comes to the question of the large German current account, there is more potential for conflict between Berlin and European partners. After all, some of Trump's advisers, but also the European Commission and some other member states, have voiced criticism of Germany’s surplus. Whatever the election outcome in September, Germany will continue to argue that its current account surplus is benign. It will push back against critics, not least to prevent foreigners from dictating domestic policy measures.

However, there might be differences between a government led by the Social Democrats and one led by the Christian Democrats. While the Christian Democrats may be expected to reject criticism and keep macroeconomic policy largely unchanged (the present position of the finance ministry under Schäuble), the Social Democrats would be expected to enact policy which might lead to a reduction of the current account surplus. Specifically, one could expect a centre-left government to increase public investment spending, which would likely bring the current account surplus down.

Germany and Turkey: A love-hate relationship

Asli Aydintasbas

In parallel with its steady move away from Europe, Turkey’s recent ties with Germany have transformed from a special partnership made up of multiple layers of social and economic connectivity to a love-hate relationship. Still, Germany remains one of Turkey’s most significant Western partners. This is not simply a foreign policy topic: Germany is one of Turkey’s main economic partners. Turkey is simultaneously an aspiring European nation, a worrisome illiberal neighbour on the fringes of the European Union, a NATO ally – and a domestic issue for Germany, where over three million people of Turkish origin live, about half with German citizenship.

Berlin has dealt with all four of these topics through policies that are separate but underpinned by an overarching realpolitik that has been the hallmark of Angela Merkel’s time in office. On Turkey’s EU accession process, Merkel has taken unenthusiastic but predictable positions, suggesting early on that she was not sold on the idea of ‘full membership’, but would nonetheless honour Turkey’s agreements with the EU. The real challenges in the relationship have come on other fronts – how to deal with Turkey’s democratic backsliding, and competition over Germany’s Turkish immigrant community. The 2016 refugee deal was a direct result of the Erdogan-Merkel handshake and effectively redefined Turkey’s new and transactional role for Europe.

Merkel was criticised in both Turkey and Germany for her reticence on Turkey’s human rights violations following the deal. However, Germany did offer safe haven to many citizens who fled Turkey because of the crackdown after the July 2016 coup attempt. Thanks to this, critical voices, like journalist Can Dündar, were able to continue to operate.

The Turkish community will emerge as a key topic between Ankara and Berlin over the next few years.

The bilateral relationship goes beyond official policies. For example, German public opinion is often a factor in relations – and it is far less tolerant of Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s illiberal policies than officialdom is. The Turkish government follows closely what German media says and how Erdogan is portrayed. Issues that have caused diplomatic tension between the two capitals include a headline in Bild calling Erdogan ‘Diktator’, or a parody of him broadcast by a German comedian.[26] In Turkey, the pro-government media is used in order to reinforce the notion that ‘the West’ is essentially against Erdogan and therefore against a ‘strong Turkey’.

This was also the key theme in propaganda efforts to persuade the Turkish population living in Germany to back Erdogan and the ruling Justice and Development Party. The Turkish government’s pre-referendum spat with Germany and the Netherlands, and its attempts to instrumentalise communities in bilateral disputes, will probably end up hurting the image of Turkish immigrants. But the Turkish government got what it wanted: in Germany, 63 percent of registered voters backed Erdogan’s proposed constitutional amendments. The fact that this figure is significantly higher than the ‘Yes’ vote in Turkey (around 51 percent) requires further scrutiny. At first glance, it appears that the Sunni Turkish vote in Germany, the Netherlands, and France gravitated towards the ruling party and the secularist, Kurdish, Alawite, and leftist voters towards ‘No’, reflecting the polarisation inside Turkey. Another possible explanation for the unusually high ‘Yes’ figure might be the fact that better-integrated second- or third-generation German Turks lack Turkish citizenship and so cannot vote, or they do not care to vote – so the proportion voting ‘Yes’ grew.

In any case, the Turkish community will likely emerge as a key topic – and, at times, a point of political negotiation – between Ankara and Berlin over the next few years. In the German political class and society at large the outcome of the referendum has already sparked heated debate about the integration of significant parts of the largest immigrant group. How can those benefiting from liberal democracy and an open society wish an autocratic state on their fellow Turks? With the arrival of about one million refugees, many Muslim, this subject has the potential to be explosive in the federal election.

The relationship is so deep that Turkey-related matters often figure in the German national debate, such as the recent flare-up over the Incirlik air base in Turkey. Traditionally, the two countries have cooperated well on defence through NATO, with Germany deploying Patriot air and anti-missile systems from Turkish soil between 2012 and 2015 against threats from Syria. But Turkey’s domestic struggles have overshadowed that larger framework of cooperation. This was the case in the 1990s too, when Germany refused the sale of military hardware due to Turkey’s human rights record in Kurdish areas. Recently, Berlin’s decision to grant asylum to Turkish military officers accused of participating in last year’s coup attempt heightened tensions, leading Turkey to bar German parliamentarians from visiting German troops stationed at Incirlik as part of the anti-Islamic State force. When the German government talked about moving its anti-ISIS surveillance team elsewhere, Turkish foreign minister Mevlut Cavusoglu responded: “If they want to leave, let’s just say goodbye.”[27]

Merkel has a tightrope to walk, between allegations that she is too soft on Erdogan and a desire to keep the refugee deal and German Turks on board. In the run-up to the federal election, Ankara might end up deciding that Merkel is a better bet than the alternatives – such as the anti-immigrant Alternative für Deutschland party, or the Social Democrats and Greens with the greater emphasis they might place on human rights.

Berlin will also play a key role in what new agreement, if any, replaces Turkey’s moribund EU accession negotiation. All of these things, and the sheer scale of the economic relationship, mean that, despite the difficulties, Turkey and Germany have no option but to keep the love-hate relationship going.

What Moscow wants from Berlin

Kadri Liik

The question of policy towards Russia was long one of the most divisive in the European Union. Some countries wanted more engagement with Moscow, in the hope that this would lead to Moscow’s full acceptance of Western rules and norms. But others were troubled by what they saw as growing authoritarianism, and feared that this would also lead to aggressive behaviour abroad. Their aspiration was rather to contain Russia, and insulate Europe from its influence.

Germany has been a dedicated member of both camps. It was long an earnest believer in engagement. Unlike some other countries, for which engagement was a pretext for profitable business deals, the German establishment really believed in transforming Russia through socialising it. For Berlin, engagement was an overwhelmingly idealistic policy – not pragmatic or opportunistic. However, at the same time Germany is also a serious adherent of the post-cold war European order with its principles, rules, and taboos. That is why, for Germany, the annexation of Crimea was a grave crime – and something that turned it into one of the firmest proponents of EU sanctions against Russia.

The engagement approach always had its dissidents whose view was different, or who simply thought that former chancellor Gerhard Schröder went too far in apologising for Russia. Likewise, the wisdom of the current sanctions policy is often questioned by influential businesspeople and politicians, not least from the Social Democrats. Differences between Angela Merkel and her former foreign minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier were not lost on Germany’s partners in the EU.

Even so, for three years, Germany has served as a pillar – or even the pillar – of the EU’s sanctions policy. This was something that Moscow had not expected, and was one of its major miscalculations in the spring of 2014. It assumed that business links, not principles, would define Europe’s and Germany’s attitude towards the annexation of Crimea. Berlin’s refusal to understand Russia on this dismayed Moscow. It remains unclear how Moscow will address its ‘Germany problem’.

It is not certain that Russia wants to intervene in the German election.

Many fear Russia might try to influence the German federal election: it is suspected of being behind serious hacking attacks on the German Bundestag; and the so-called ‘Lisa case’ – a fabricated story aiming to inflame anti-immigrant sentiment – is now famous all over Europe. But there are also factors that make interference hard, and therefore less likely. As demonstrated already by the French presidential election, countries now know to expect outside interference. Also, compared to many other countries, Germany is not easy to influence: the country’s political class enjoys high credibility ratings, political debate is relatively serious, fact-based and measured, and the sensationalist press is small.

Furthermore, it is not certain that Russia even wants to intervene. Vladimir Putin has a highly personalised approach to foreign policy. Hillary Clinton, for example, was seen as having acted against Putin on his home soil when she supported anti-government protests in 2011-12 – something the Kremlin finds unforgiveable. By comparison, Putin sees Merkel as an honest and dignified adversary.

Nor would the Kremlin necessarily prefer Martin Schulz, the Social Democratic candidate for chancellor. Despite his party, Schulz may turn out not to be much friendlier. When presiding over the European Parliament, Schulz warned that developments in Poland under the Law and Justice Party were signs of a “dangerous Putinisation of European politics”.[28] One of his major election campaign themes is to strengthen democracy in Germany and Europe.

In this context, Moscow may well prefer a known partner to an unknown one, especially as Merkel is one of the few Western politicians who can actually communicate with Putin. Her message, though tough, is clear. As put by one Moscow insider, “But surely Merkel will have to stay in office for at least as long as Putin? Because, otherwise, who could he talk to?”[29]

Even if Russia refrains from trying to sway the German election, it is clear that it will seek to use political developments to weaken Germany’s principled position on sanctions. In this context, Moscow had high hopes for Donald Trump, and these have still not faded. In another theatre, Moscow is also courting European capitals with the unspoken aim of crushing the European consensus on sanctions.

Amazingly, Germany’s Russia policy has managed to gain the trust of the most vulnerable and sensitive EU members: in the Baltic states, few complain about Berlin these days. This is a big change, and a result of conscious policy. Germany makes a point of consulting with and informing them, and has gained credit by actively engaging in Baltic air policing. But there are also slightly bigger, and slightly less vulnerable countries, which feel left out of policy processes dominated by Germany and France, such as the Normandy process on the Minsk agreement. They want ‘more Europe’ in Europe’s Russia policy.

If Germany wants to continue shaping a European consensus, it needs to take care not to appear selfish. The Nordstream II gas pipeline is the case in point: fairly or not, some countries view this as infringing on their security interests, others as preferential treatment of German energy needs while the rest of the EU suffers from the effects of sanctions. If sanctions are to remain viable, ‘suffering’ needs to be divided proportionately.

The EU will need to return to a deeper discussion of what constitutes the right policy on Russia: what works, and what the right balance of carrots and sticks is. This debate could reopen the old divisions. Or it could rise to a new level and foster a more sophisticated European consensus than seen now. Much depends on Germany: the quality of its leadership, intellectual horizons, even-handedness, and consensus-building.

Conclusion: Berlin, the risk-taker?

2016 marked a watershed moment for Germany, and for the European Union as a whole. A disintegrating union in light of the ‘Brexit’ vote, and the election of an unpredictable president on the other side of the Atlantic put almost a decade of EU crises over prosperity, security and migration in a completely different light. Suddenly the EU 27 find themselves out in the open, with vulnerabilities laid ever more bare.

In this moment of unprecedented uncertainty, Germany is not the only EU country that has opted for ‘taking the bull by the horns’, wanting to move more decisively to contain the threat of disintegration, and to continue investing in the EU as the preferred model of regional order. Since the summer of 2016 Berlin has invested in building a new consensus in the EU 27, and has found like-minded EU countries willing to re-energise their choice for Europe. But the real challenge lies ahead: namely, to forge a new deal around core policies to preserve economic prosperity and social cohesion, and strengthen European security.

Emmanuel Macron’s articulate pro-EU stance as well as his strong orientation towards Berlin suggests there is a will for stronger Franco-German relations at EU level. However, the outcome of the legislative election in France will determine Macron’s room for manoeuvre, and in the end this might turn out to be more limited – but the same is true for the German federal election. Macron has pushed the issue of eurozone reform into the heart of the public debate in Germany. And, while leading members of the current coalition government have embraced even the more controversial proposals by signalling an openness to discuss them, the question remains the extent to which the German public will be willing to go along with them.

The upcoming federal election is likely to bring about another coalition government, and one with a solid pro-EU orientation.[30] However, shaping majorities for much-needed EU reforms will not be a walk in the park in Germany either. The Alternative für Deutschland, which is likely to surpass the 5 percent threshold to make it into the Bundestag, will use its presence in parliament to mobilise anti-EU sentiment. And Germany will have to open up to change and compromise, in particular over eurozone governance matters, and Germany’s contributions to European security – both of which have the potential to become controversial issues among the electorate. That said, polls referred to in this report suggest that there is still a hidden reservoir of support among the German public for strengthening European cooperation, and even integration, that election campaigners can tap into.

Greater flexibility has come to be seen as a vehicle for maintaining political momentum for a more ambitious EU agenda following almost a decade of crises. Berlin’s shift towards accepting flexibility is notable, as is its apparent move towards becoming more of a risk-taker. It has overcome its aversion to the fear that flexible modes of cooperation might accelerate disintegration, and the government is now placing its expectations in much-needed deliverables. But the risk remains that other EU members get left behind in a scenario in which groups of countries, including Germany, move ahead. And there is also the risk of alienating the EU’s institutions, in particular the European Commission, if a reactivated Franco-German engine, supported by others, chooses an intergovernmentalist approach as the preferred form of cooperation, if only for a transition period.

Focusing on results is the mantra of the day, but the German case also illustrates what holds true for perhaps all EU members: securing one’s interests is a complicated game when domestic, European and international arenas interact with each other, and long-standing certainties no longer hold.

The case studies on international trade and the German surplus and relations with Turkey, and with Russia, are cases in point. Will the current and future federal government manage to keep its public happy, strengthen the EU, and maintain an international environment favourable to German interests – all at the same time? This analysis has shown that this requires a careful calibration by policymakers at all levels, an exceptionally difficult exercise when long-standing certainties about European unity and transatlantic consensus can no longer be taken for granted.

As things stand, in 2017 Germany will continue to place its ambitions in the EU as the best way of securing German interests. Years of crises and quarrels between member states, combined with the mounting challenges encircling the EU, including from the UK and the US, have led the German political class to believe that the time has come to take greater risks to secure the EU’s future.

[1] Josef Janning and Almut Möller: “Leading from the centre: Germany’s role in Europe”, ECFR, July 2016, available at https://ecfr.eu/publications/summary/leading_from_the_centre_germanys_role_in_europe_7073.

The author of the opening essay and the conclusion in this policy brief is Almut Möller.

[2] “Was an mir Deutsch ist?”, interview with Donald Trump, Bild, 16 January 2017.

[3] Almut Möller and Dina Pardijs, “The Future Shape of Europe. How the EU can bend without breaking”, ECFR Flash Scorecard, March 2017, available at https://ecfr.eu/specials/scorecard/the_future_shape_of_europe; EU28 Survey 2016, part of Rethink: Europe, an initiative of ECFR and Stiftung Mercator. The Coalition Explorer is available at www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer. See also: Josef Janning and Christel Zunneberg, “The Invisible Web: From interaction to coalition-building in the European Union”, ECFR, May 2017, available at www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer.

[4] “Ich denke, wir Europäer haben unser Schicksal selber in der Hand. Ich werde mich weiter dafür einsetzen, dass die 27 Mitgliedstaaten intensiv und vor allen Dingen auch zukunftsgerichtet zusammenarbeiten.”, press conference by Angela Merkel and the prime minister of New Zealand, Berlin, 16 January 2017, available at https://www.bundeskanzlerin.de/Content/DE/Mitschrift/Pressekonferenzen/2017/01/2017-01-16-bkin-pm-neuseeland.html.

[5] Timothy Garton Ash, “Populists are out to divide us. They must be stopped”, the Guardian, 11 November 2016, available at

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/11/ populists-us.

[6] Almut Möller and Dina Pardijs, “The Future Shape of Europe. How the EU can bend without breaking”, ECFR Flash Scorecard, March 2017, available at

https://ecfr.eu/specials/scorecard/the_future_shape_of_europe.

[7] Declaration of the leaders of 27 member states and of the European Council, the European Parliament and the European Commission, Rome, 25 March 2017,

available at http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/03/25-rome-declaration/.

[8] Almut Möller and Dina Pardijs, “The Future Shape of Europe. How the EU can bend without breaking”, ECFR Flash Scorecard, March 2017, available at https://ecfr.eu/specials/scorecard/the_future_shape_of_europe

[9] EU28 Survey 2016, part of Rethink: Europe, an initiative of ECFR and Stiftung Mercator, available at https://ecfr.eu/europeanpower/rethink.

[10] EU28 Survey 2016, part of Rethink: Europe, an initiative of ECFR and Stiftung Mercator, available at https://ecfr.eu/europeanpower/rethink.

[11] Wolfgang Schäuble, “Beste Vorsorge für das 21. Jahrhundert”, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 20 March 2017, available at http://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Interviews/2017/2017-03-20-FAZ.html.

[12] “Die Handlungsfähigkeit der EU muss heute in Problemfeldern verbessert werden, in denen auch in den Augen europaskeptischer Bevölkerungsteile keine allein nationalstaatlichen Lösungen möglich sind. Jeder, der in Brüsseler Abläufen kundig ist, weiß heute, dass Änderungen des Lissabon-Vertrages als europäischem Primärrecht kurzfristig unrealistisch sind. (…) Soweit dies durch die rechtlichen und tatsächlichen Begrenzungen im Rahmen des Primärrechts nicht machbar ist, muss es zunächst pragmatisch, im Wege der Verstärkten Zusammenarbeit oder auch intergouvernemental vorangebracht werden – wie immer man dies im Einzelfall nennen mag: variable Geometrie oder flexible Geschwindigkeit, Kerneuropa oder ‘coalition of the willing’.”

[13] Hans Kundnani, “The New Parameters of German Foreign Policy”, GMF Policy Paper, The German Marshall Fund of the United States, February 2017, available at http://www.gmfus.org/publications/new-parameters-german-foreign-policy

[14] Almut Möller and Dina Pardijs, “The Future Shape of Europe. How the EU can bend without breaking”, ECFR Flash Scorecard, March 2017, available at

https://ecfr.eu/specials/scorecard/the_future_shape_of_europe.

[15] See Thorsten Benner and Thomas Gomart, “Meeting Macron in the Middle. How France and Germany can revive the EU”, Foreign Affairs, 8 May 2017, available at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/europe/2017-05-08/meeting-macron-middle.

[16] See, for example, the headlines of Bild Zeitung: “Neue Zeiten in Frankreich: Wie teuer wird Macron für uns?”, 8 May 2017, available at http://www.bild.de/politik/ausland/emmanuel-macron/wie-teuer-wird-macron-51652556.bild.html; and the title of weekly magazine Der Spiegel: “Teurer Freund: Emmanuel Macron rettet Europa… und Deutschland soll zahlen.”, issue 20/2017, 13 May 2017.

[17] Paul Hampel, “Macrons Sieg bedeutet vor allem eines: Es wird sehr teuer”, press release by Alternative für Deutschland, 8 May 2017, available at https://www.afd.de/paul-hampel-macrons-sieg-bedeutet-vor-allem-eines-es-wird-sehr-teuer/.

[18] Foreign minister Sigmar Gabriel referred to a joint op-ed with Macron during their time as economy ministers in 2015: “Europe cannot wait any longer: France and Germany must drive ahead”, The Guardian, 3 June 2015, available at https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jun/03/europe-france-germany-eu-eurozone-future-integrate; finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble highlighted points of convergence in an interview with the Italian newspaper La Repubblica: “Schäuble: ‘Così Francia e Germania cambieranno la Ue’”, available at http://www.repubblica.it/economia/2017/05/11/news/scha_uble_cosi_francia_e_germania_cambieranno_la_ue-165144892/.

[19] Die Sicht der Deutschen auf Europa und die Außenpolitik: Eine Studie der TNS Infratest Politikforschung im Auftrag der Körber-Stiftung, October 2016, available at http://www.zeit.de/politik/ausland/2016-11/eu-skepsis-deutschland-umfrage-brexit-usa.

[20] Wahlkampfauftritte Türkischer Politiker in Deutschland, ARD-DeutschlandTREND März 2017, available at http://www.infratest-dimap.de/umfragen-analysen/bundesweit/ard-deutschlandtrend/2017/maerz/.

[21] Standard Eurobarometer 86: Die öffentliche Meinung in der Europäischen Union. Nationaler Bericht Deutschland, Autumn 2016, available at http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/STANDARD/surveyKy/2137.

[22] Eine europäische Erfolgsgeschichte? Die Hälfte der Deutschen sieht die EU auf Abwegen, Ipsos, 24 March 2017, available at https://www.ipsos.com/de-de/eine-europaische-erfolgsgeschichte-die-halfte-der-deutschen-sieht-die-eu-auf-abwegen.

[23] Die Sicht der Deutschen auf Europa und die Außenpolitik: Eine Studie der TNS Infratest Politikforschung im Auftrag der Körber-Stiftung, October 2016, available at http://www.zeit.de/politik/ausland/2016-11/eu-skepsis-deutschland-umfrage-brexit-usa.

[24] Sigmar Gabriel, “Deutschland: kein europäisches Nettozahler-, sondern ein Nettogewinner-Land”, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 22 March 2017. “Die Wahrheit ist, dass Deutschland kein europäisches Nettozahler-, sondern ein Netto-Gewinner Land ist. (…) Jeder Euro, den wir also für den EU-Haushalt zur Verfügung stellen, kommt – direkt oder indirekt – mehrfach zu uns zurück. (…) Statt für eine Verringerung unserer Zahlungen an die Europäische Union zu kämpfen, die Bereitschaft zu signalisieren, sogar mehr zu zahlen”. Available at http://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/DE/Infoservice/Presse/Interviews/2017/170322-BM_FAZ.html.

[25] Almut Möller and Dina Pardijs, “The Future Shape of Europe. How the EU can bend without breaking”, ECFR Flash Scorecard, March 2017, available at

https://ecfr.eu/specials/scorecard/the_future_shape_of_europe.

[26] “Diktator Erdogan: Wo soll das noch alles enden?”, Bild, 26 May 2017, available at http://www.bild.de/politik/ausland/recep-tayyip-erdogan/wo-soll-das-noch-alles-enden-48612596.bild.html; “Turkey asks Germany to prosecut comedian over Erdoğan poem”, the Guardian, 11 April 2016, available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/11/turkey-germany-prosecute-comedian-jan-bohmermann-erdogan-poem.

[27] “Turkey will ‘not beg’ for German troops to stay at Incirlik base”, DW, available at http://www.dw.com/en/turkey-will-not-beg-for-german-troops-to-stay-at-incirlik-base/a-38887076.

[28] Leo Cendrowicz, “Polish leaders defend reforms as EU warns of ‘dangerous Putinisation of European politics’”, the Independent, 17 January 2016, available at http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/polish-leaders-defend-reforms-as-eu-warns-of-dangerous-putinisation-of-european-politics-a6818346.html.

[29] Interview conducted by the author, Moscow, 10 May 2017.

[30] The latest poll by Infratest dimap from 11 May 2017 sees the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) on 37 percent, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) on 27 per cent, Die Linke (The Left) on 7 percent, both the Green Party and the Free Democratic Party (FDP) on 8 percent, and the AFD on 10 percent. Numbers available at https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/deutschlandtrend-779.pdf.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.