The crisis of American power: How Europeans see Biden’s America

Summary

- Most Europeans rejoiced at Joe Biden’s victory in the November US presidential election, but they do not think he can help America make a comeback as the pre-eminent global leader.

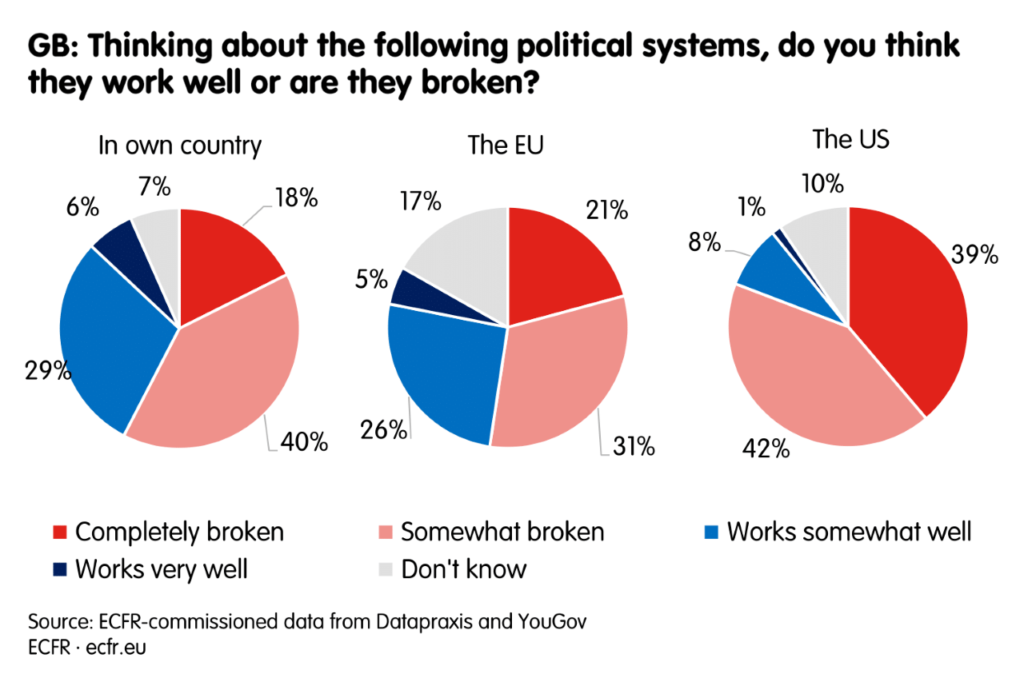

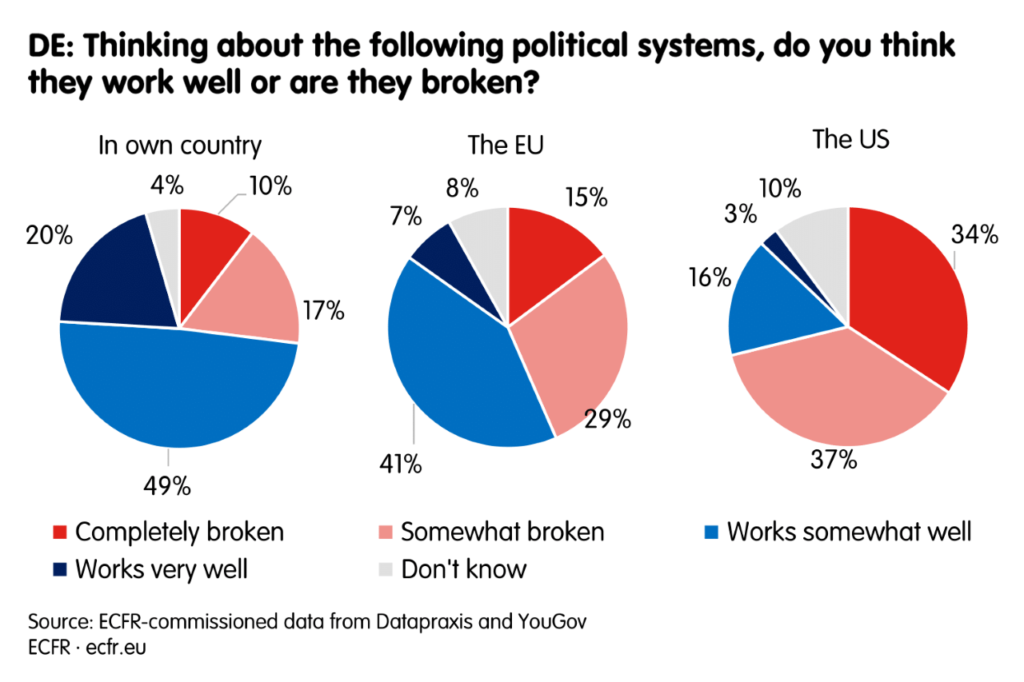

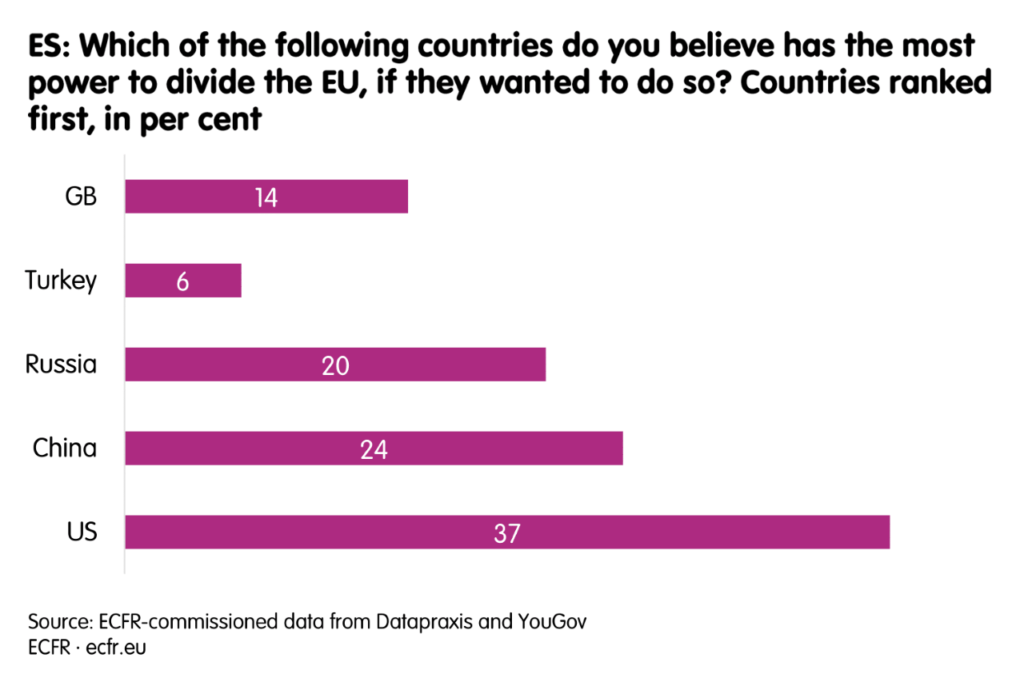

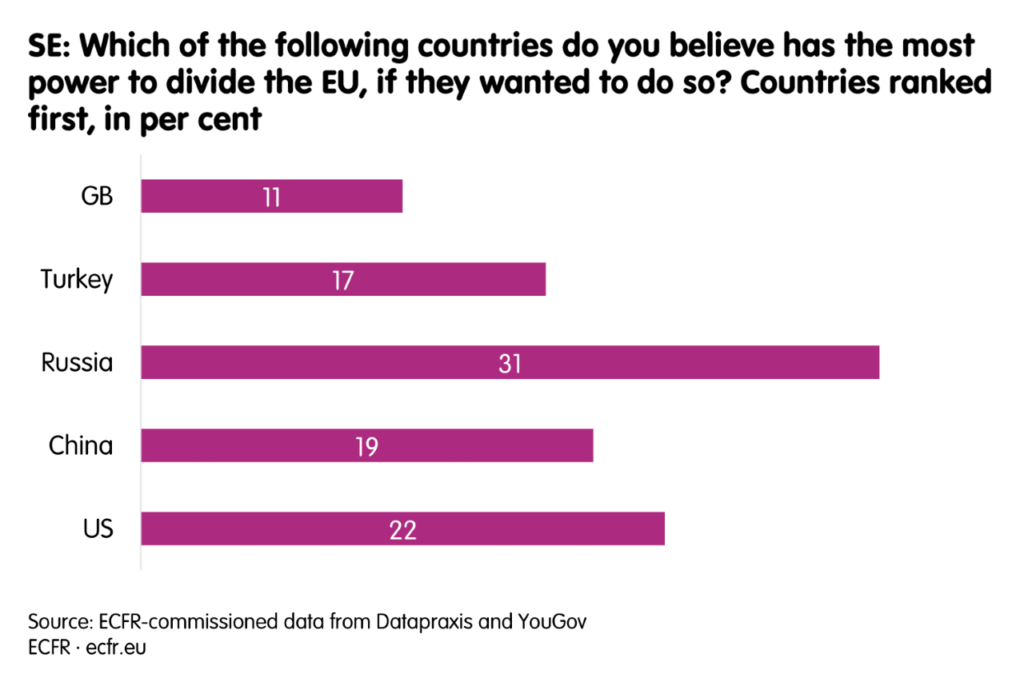

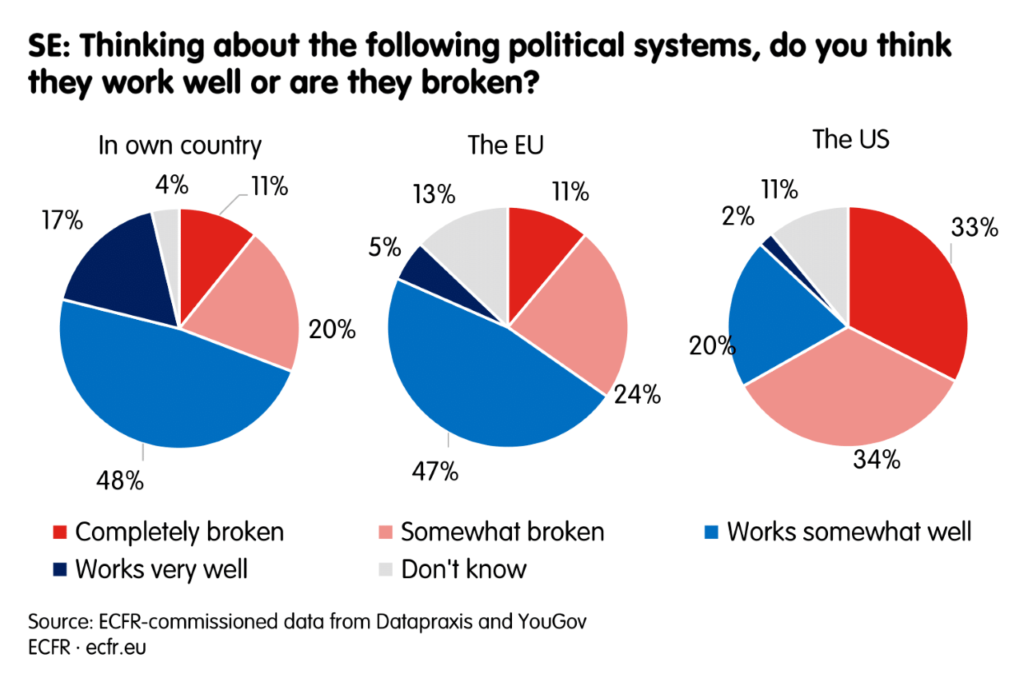

- Europeans’ attitudes towards the United States have undergone a massive change. Majorities in key member states now think the US political system is broken, and that Europe cannot just rely on the US to defend it.

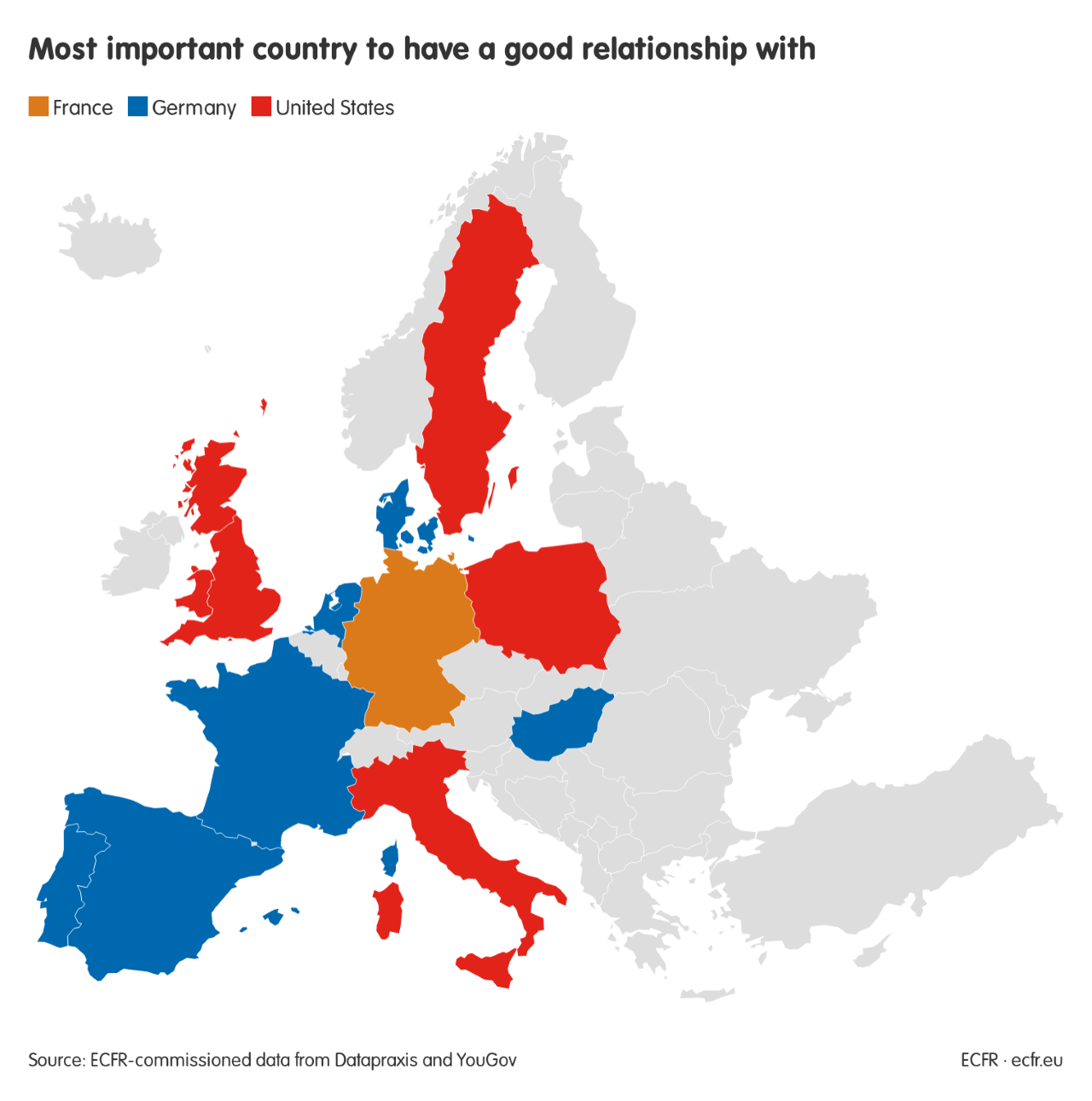

- They evaluate the EU and/or their own countries’ systems much more positively than that of the US – and look to Berlin rather than Washington as the most important partner.

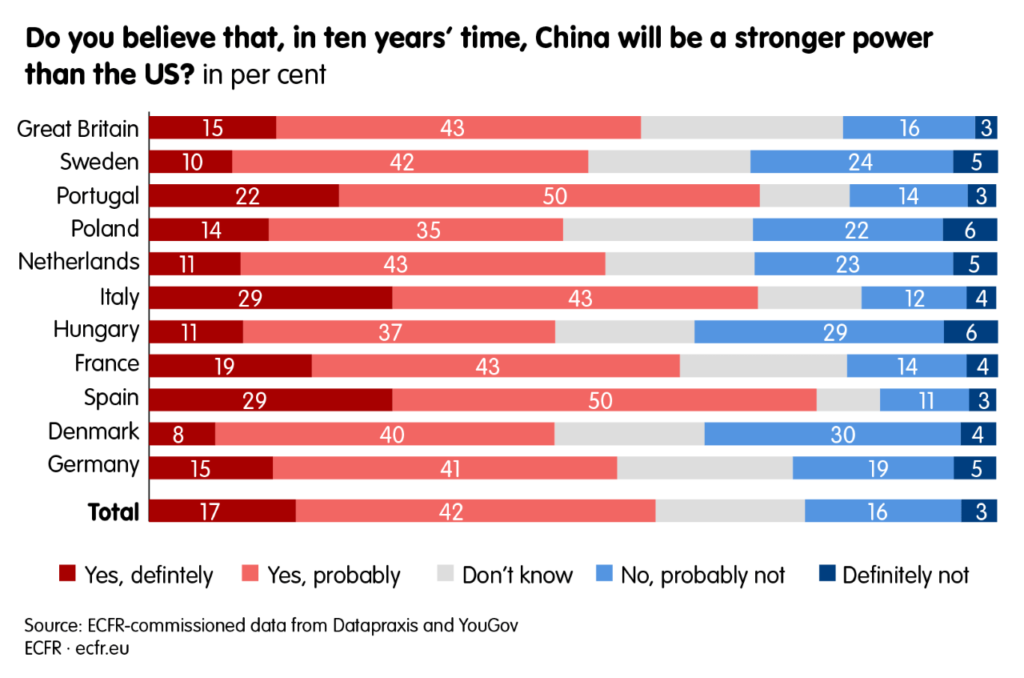

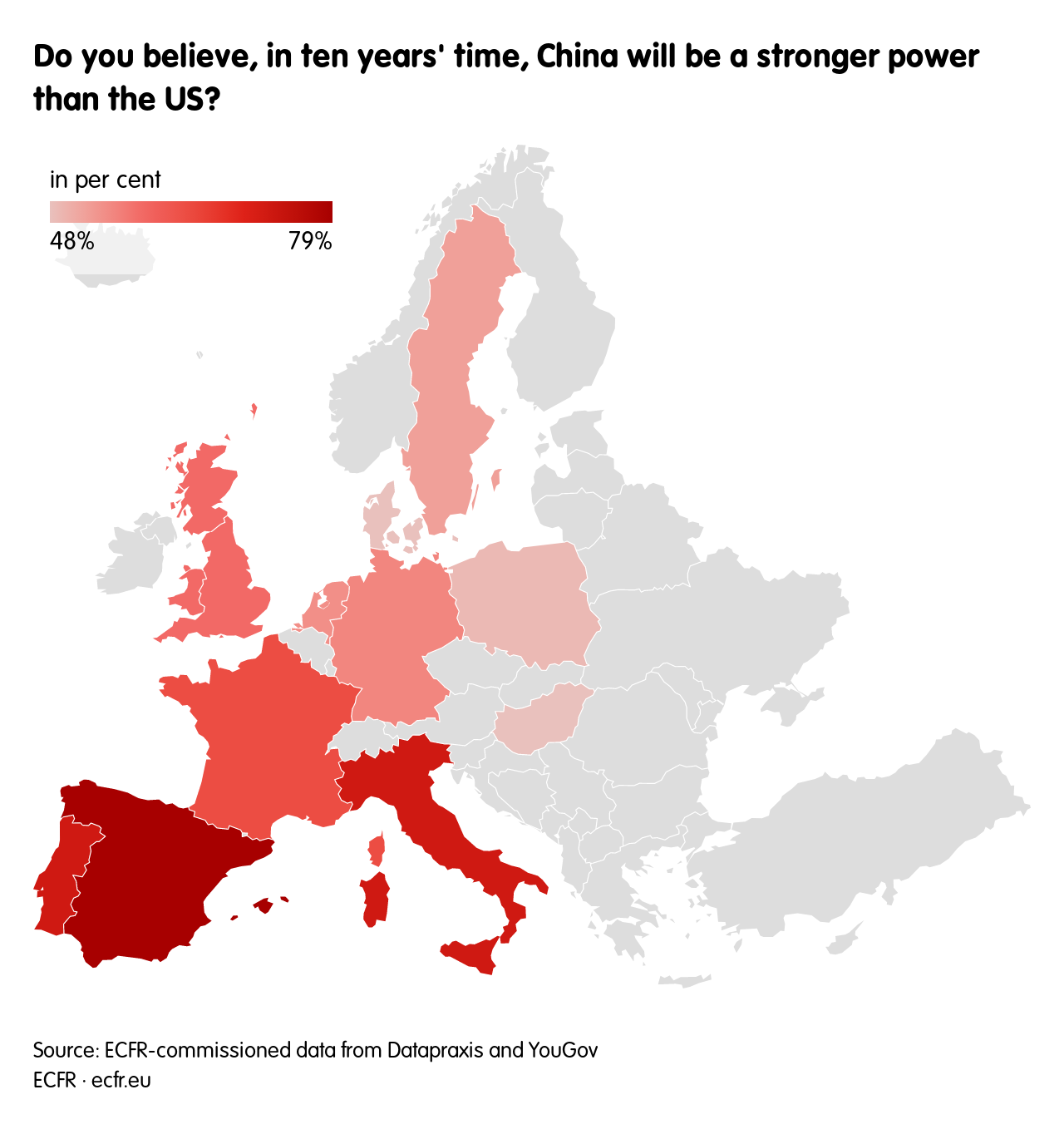

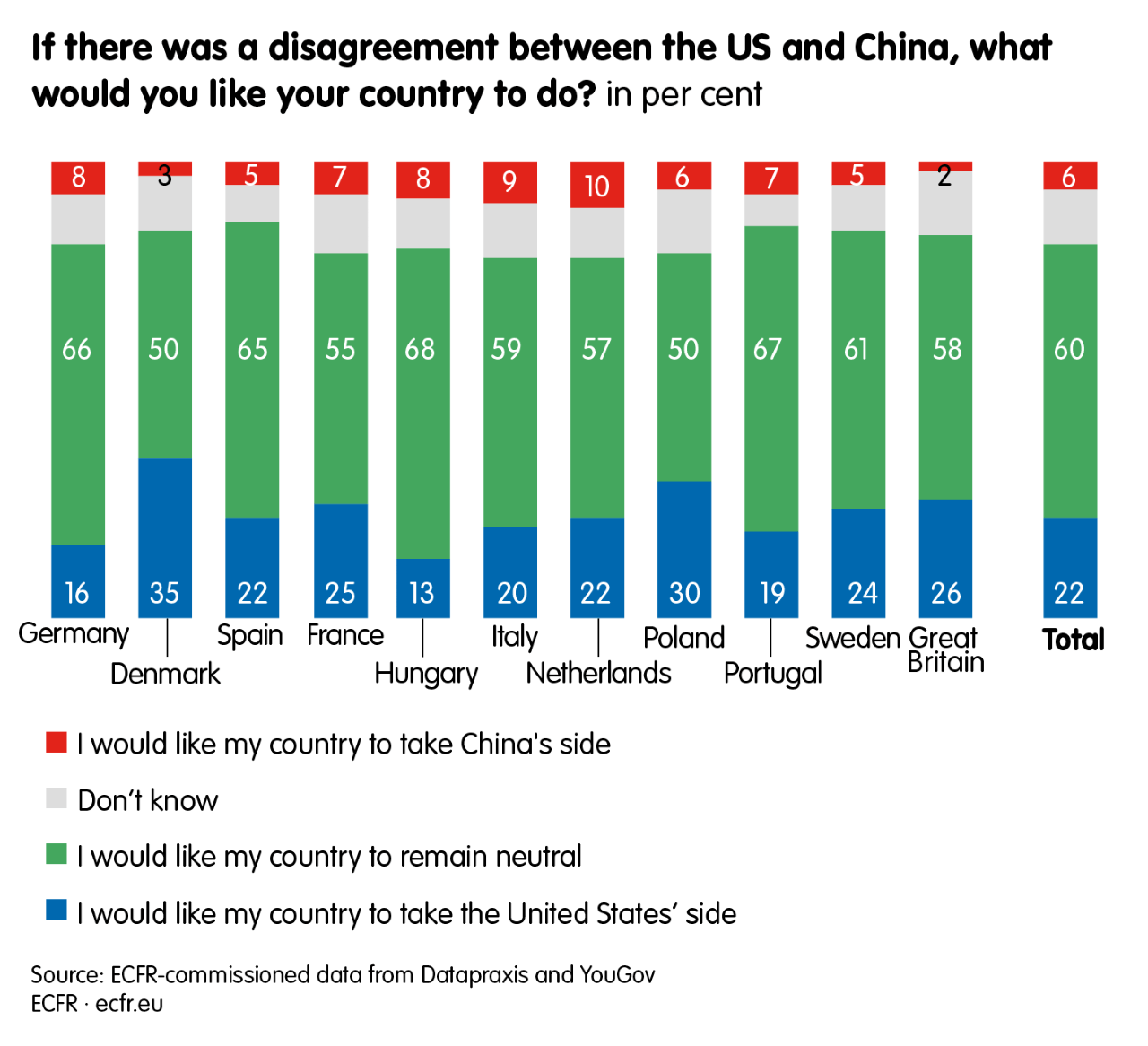

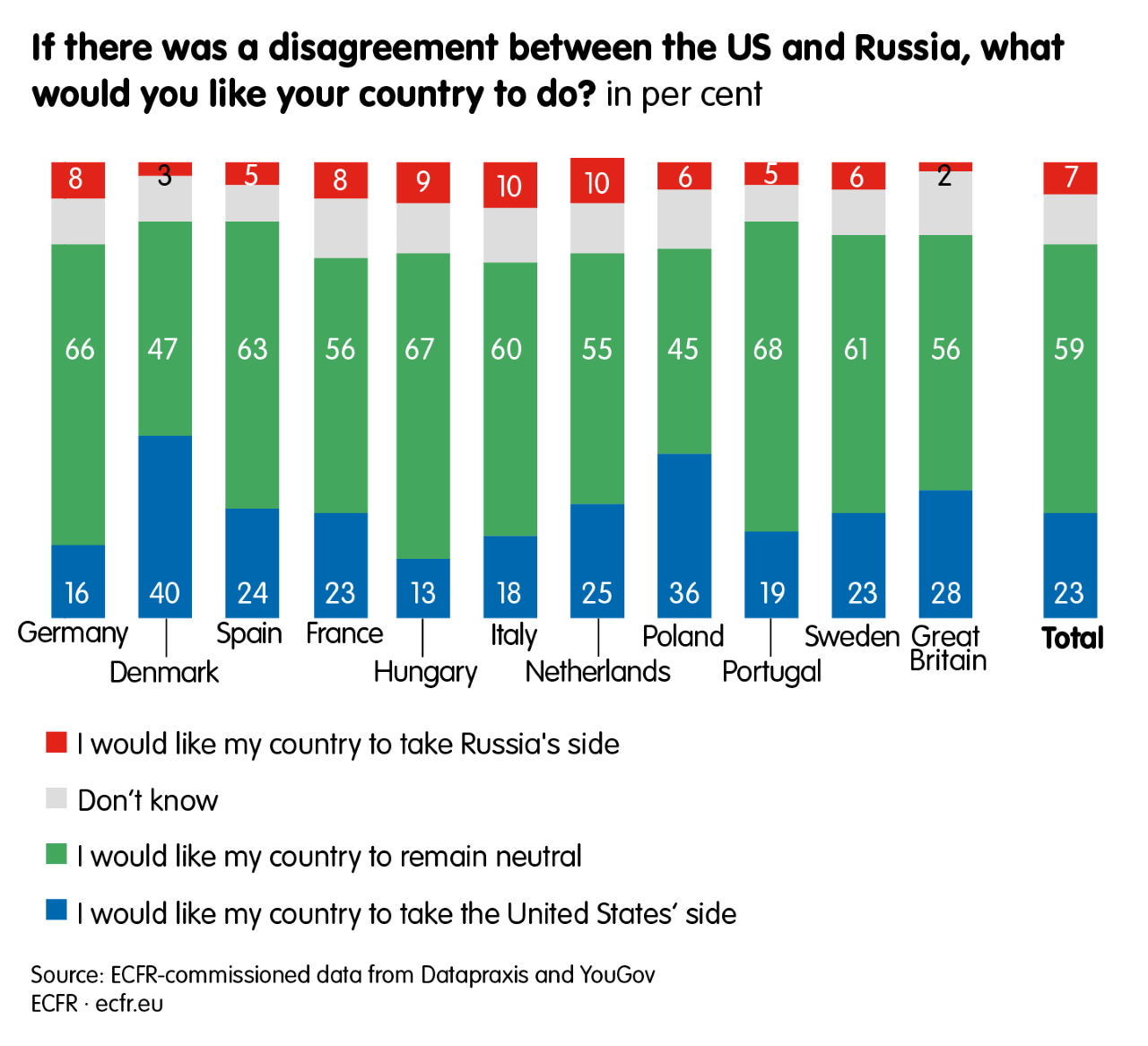

- There are geopolitical consequences to American weakness. A majority believe that China will be more powerful than the US within a decade and would want their country to stay neutral in a conflict between the two superpowers. Two-thirds of respondents thought the EU should develop its defence capacities.

- There is a great chance for a revival of Atlanticism, but Washington cannot take European alignment against China for granted. Public opinion will have a bigger effect on the relationship than it once did, and needs to be taken into account.

Introduction

Americans have a new president but not a new country. While most Europeans rejoiced at Joe Biden’s victory in the November US presidential election, they do not think he can help America make a comeback as the pre-eminent global leader. This is the key finding of a pan-European survey of more than 15,000 people in 11 countries commissioned by the European Council on Foreign Relations, and conducted in November and December by Datapraxis and YouGov.

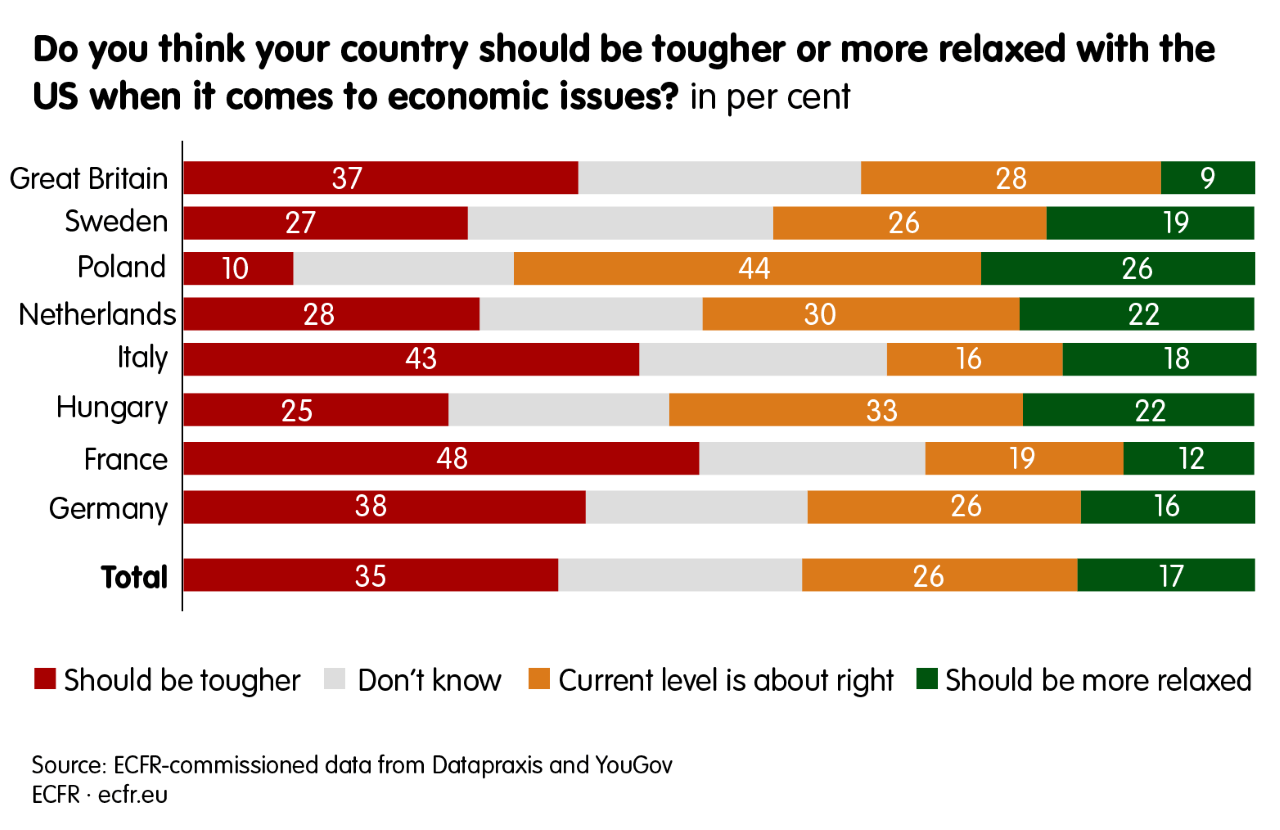

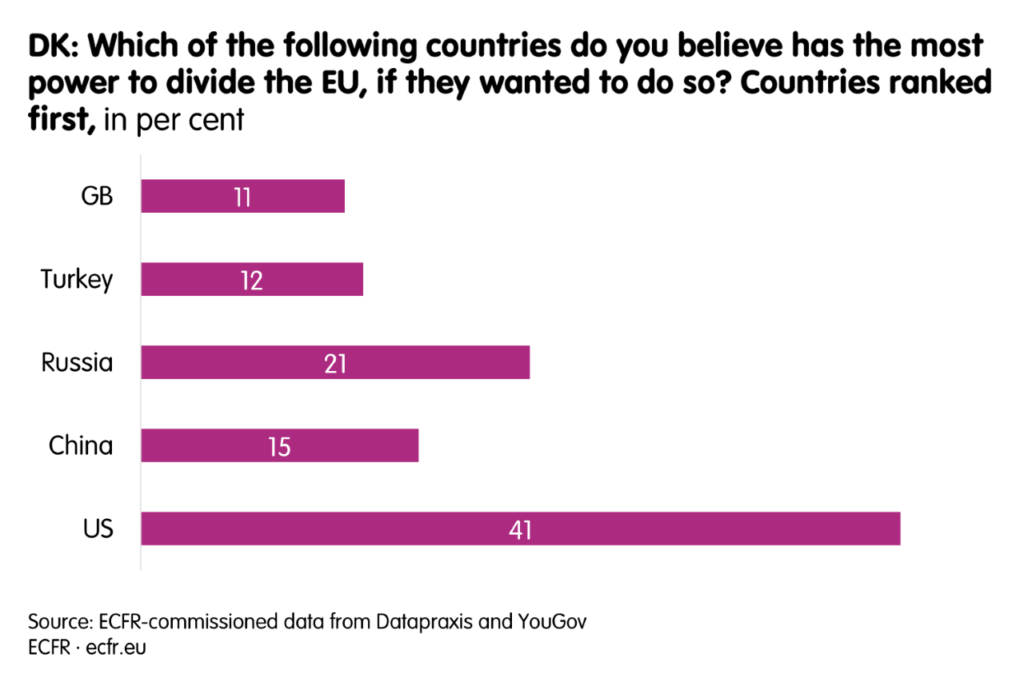

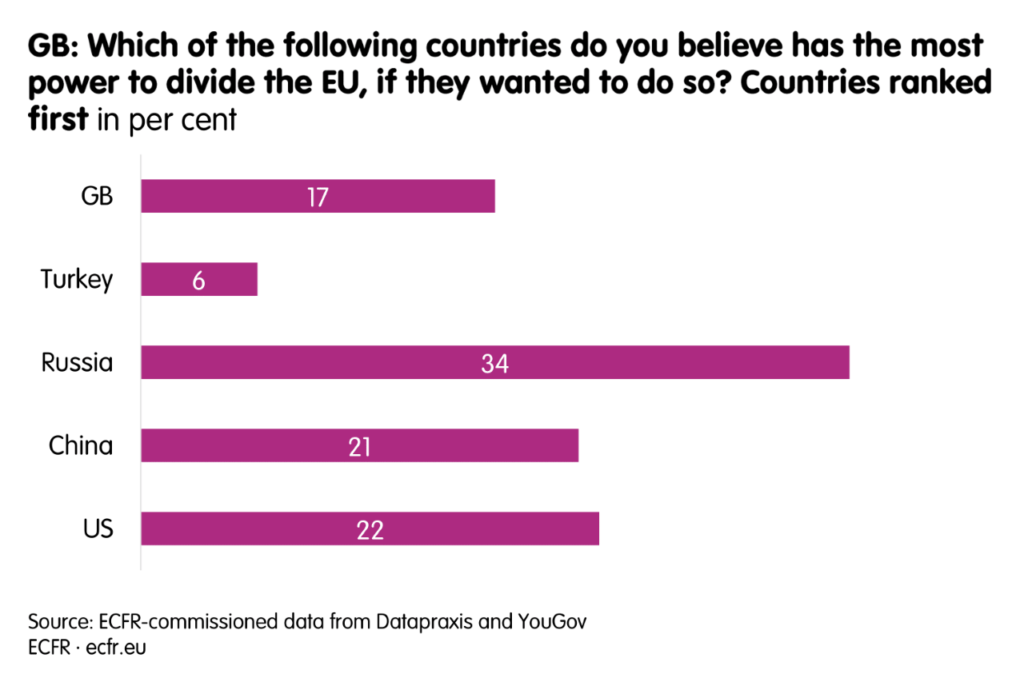

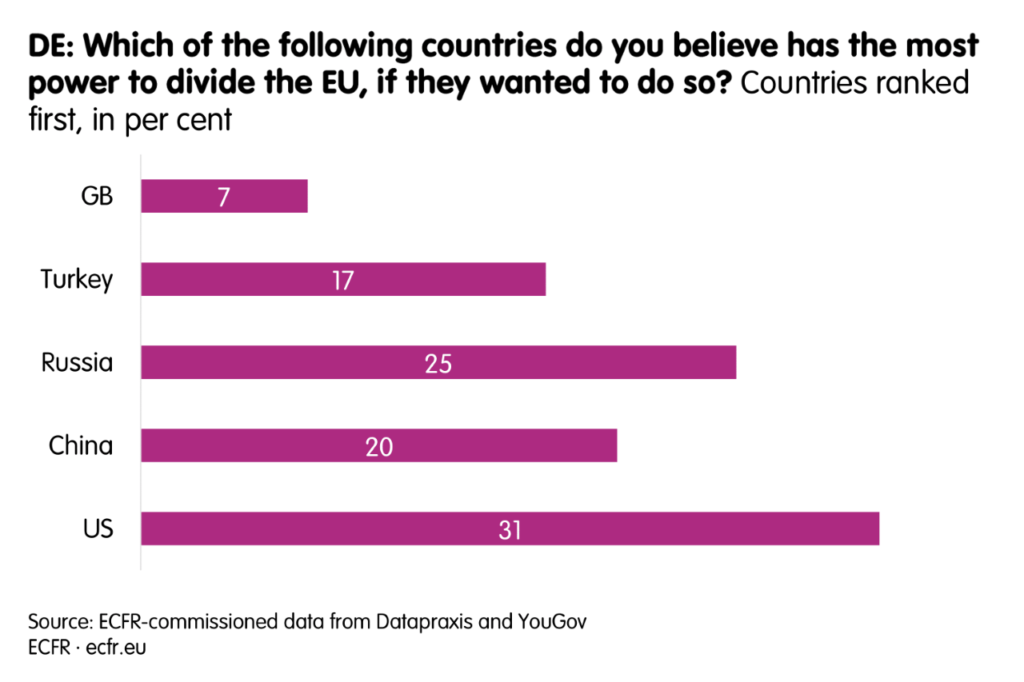

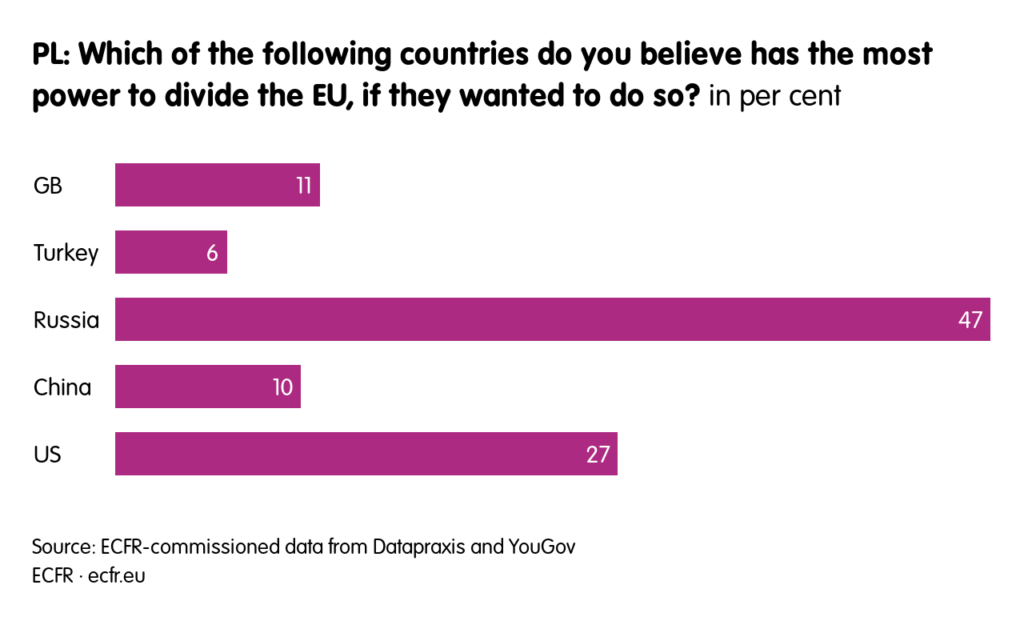

Our survey showed that Europeans’ attitudes towards the United States have undergone a massive change. Majorities in key member states now think the US political system is broken, that China will be more powerful than the US within a decade, and that Europeans cannot rely on the US to defend them. They are drawing radical consequences from these lessons. Large numbers think Europeans should invest in their own defence and look to Berlin rather than Washington as their most important partner. They want to be tougher with the US on economic issues. And, rather than aligning with Washington, they want their countries to stay neutral in a conflict between the US and Russia or China.

In the run-up to the Iraq war in 2003, European countries were divided on whether to align with George Bush’s America over values (in Robert Kagan’s famous formulation, Americans were from Mars, Europeans from Venus) but few doubted his power to shape the world. The opposite is true with Biden. Many Europeans believe in his promise to re-engage internationally but – after witnessing America’s response to covid-19 and domestic polarisation – most doubt Washington’s capacity to shape the world.

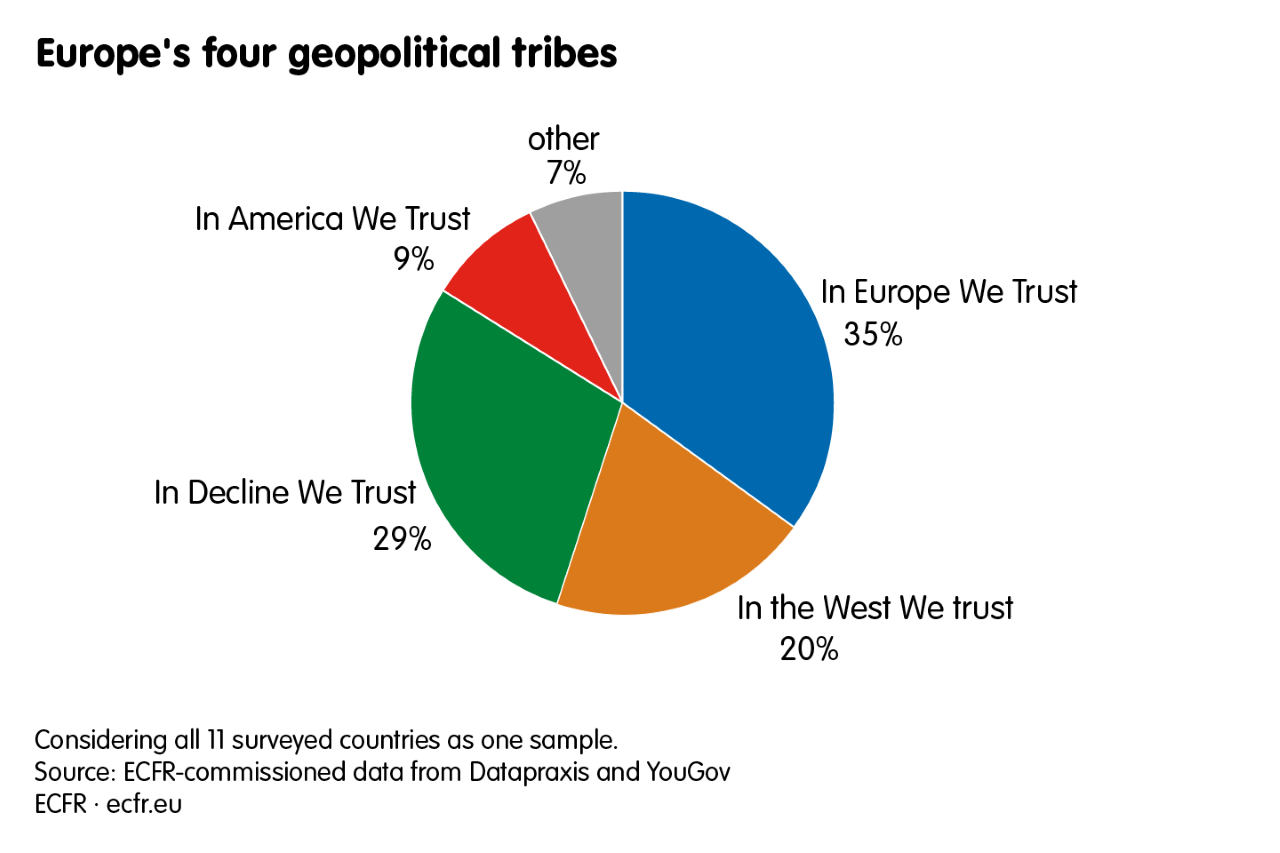

These divisions run through European countries rather than between them. Rather than splitting Europe into its ‘new’ and ‘old’ parts as in 2003, we can identify four new tribes based on their views of power in the twenty-first century.

During the cold war, public opinion only played a secondary role in the transatlantic relationship, which was considered a raison d’état by policy elites. But the transatlantic relationship in the 2020s is seen as much less existential in both Europe and America – and has for that reason been politicised. It is enough to look at the mind-blowing performance of the American stock market in a year when American the economy is in a coma to conclude that, in a time of plague, sentiments are running the world. We can see that public moods have policy consequences.

Happy with Biden, but don’t trust American voters

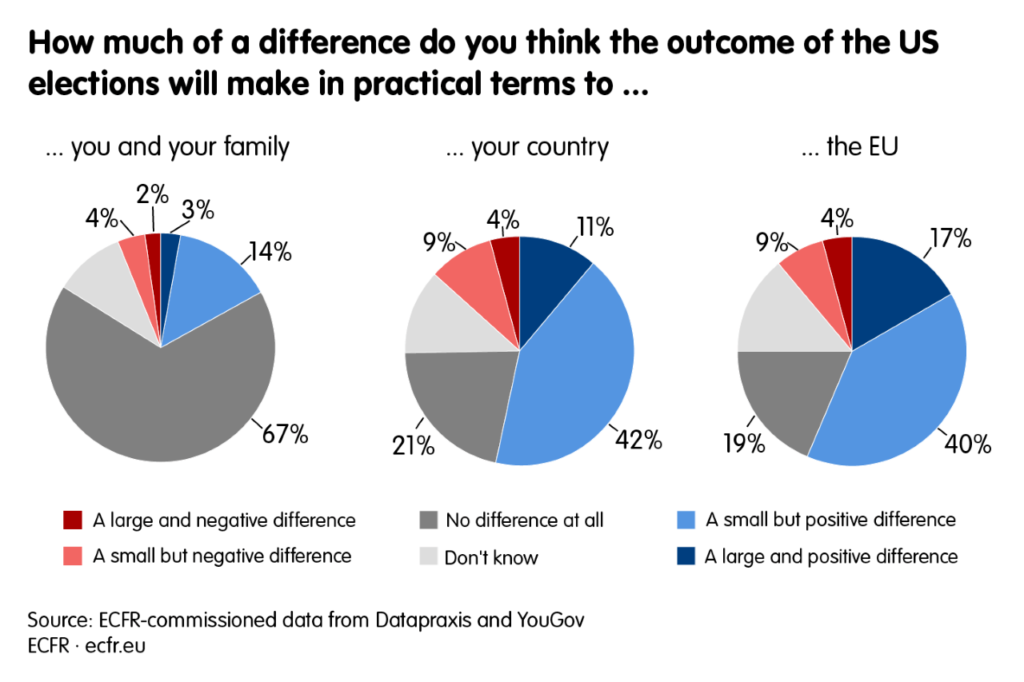

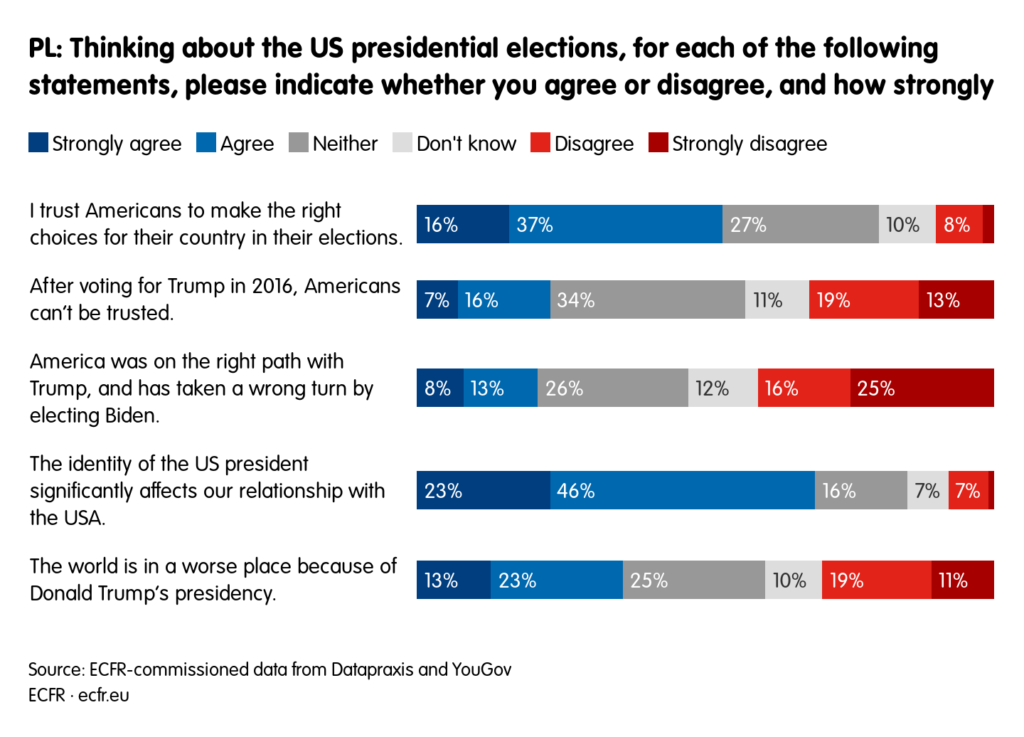

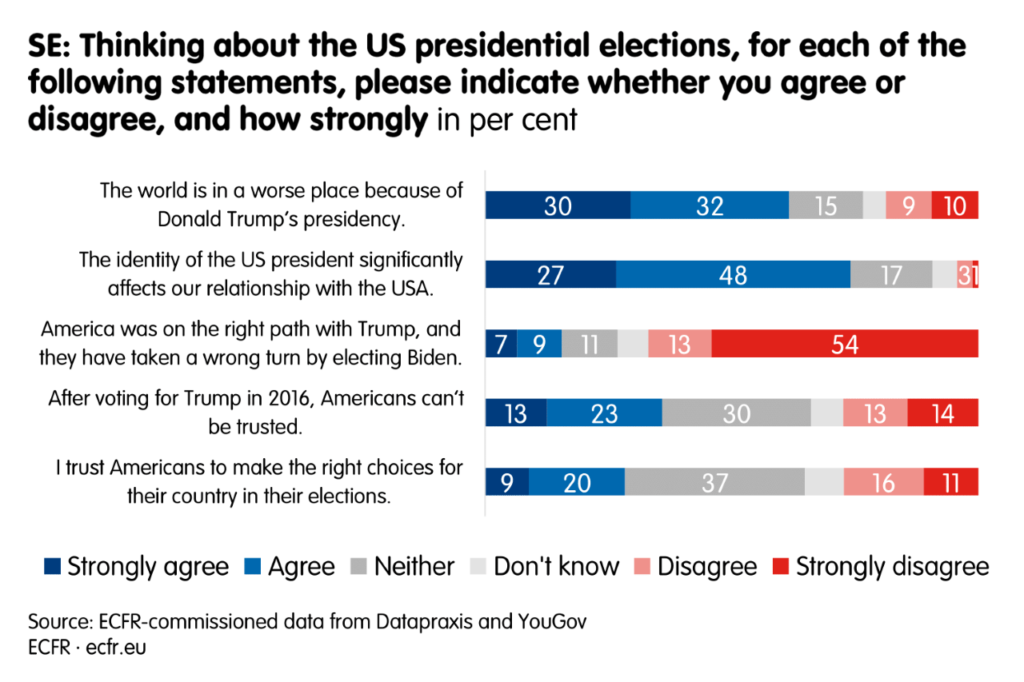

Across the 11 countries covered by ECFR’s poll, 53 per cent of respondents believe that Biden’s victory makes a positive difference to their countries, and 57 per cent that it is beneficial for the EU. Even in Hungary and Poland, whose populations have been among the most pro-Trump in Europe, more people say that his electoral defeat is good for their countries than the opposite.

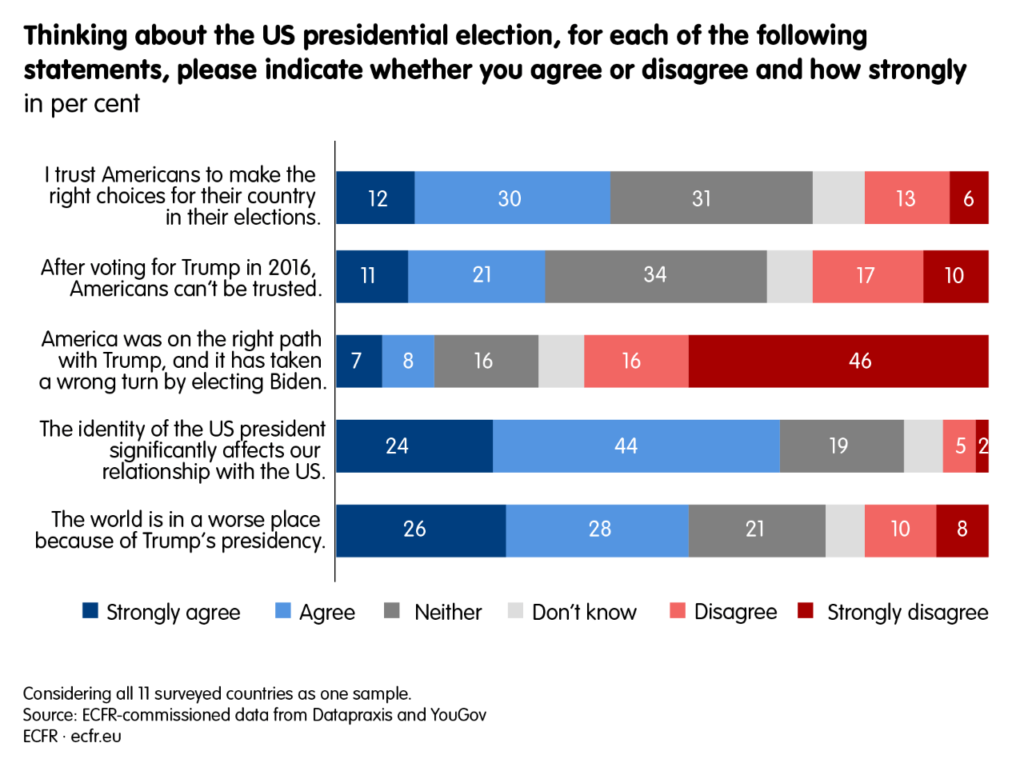

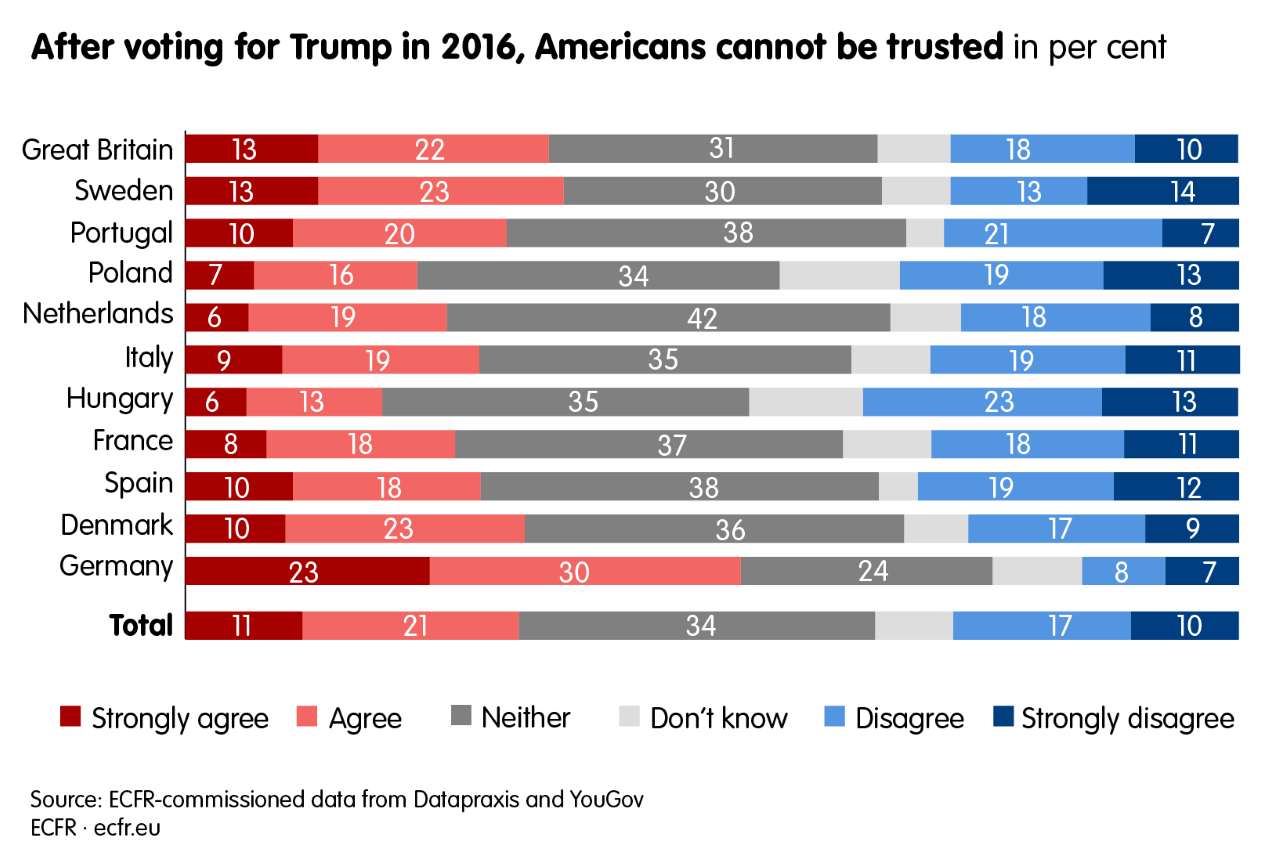

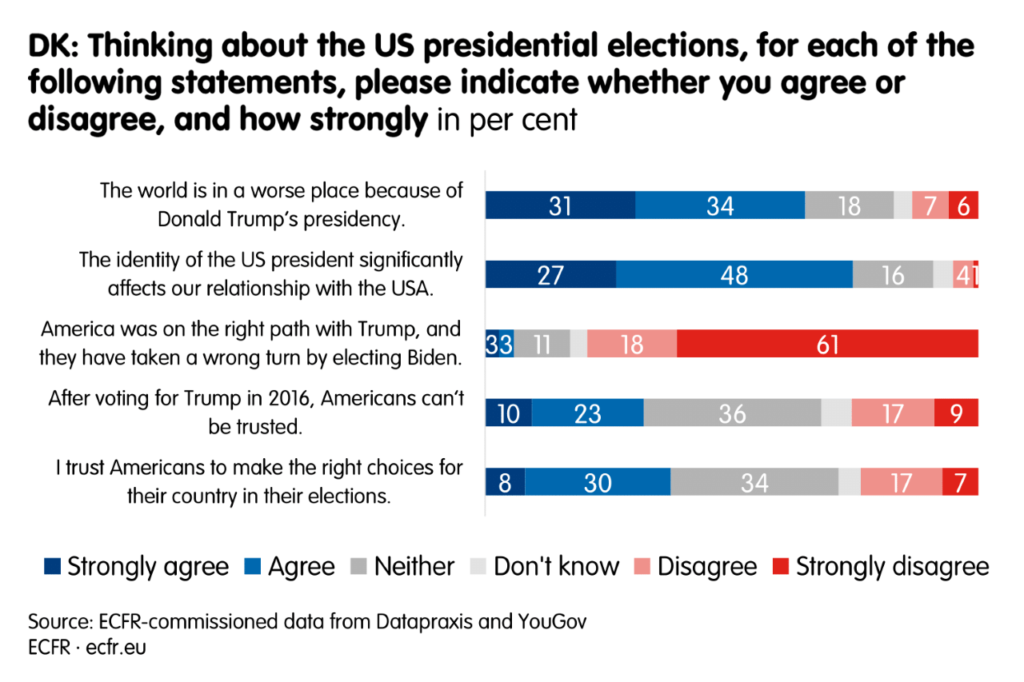

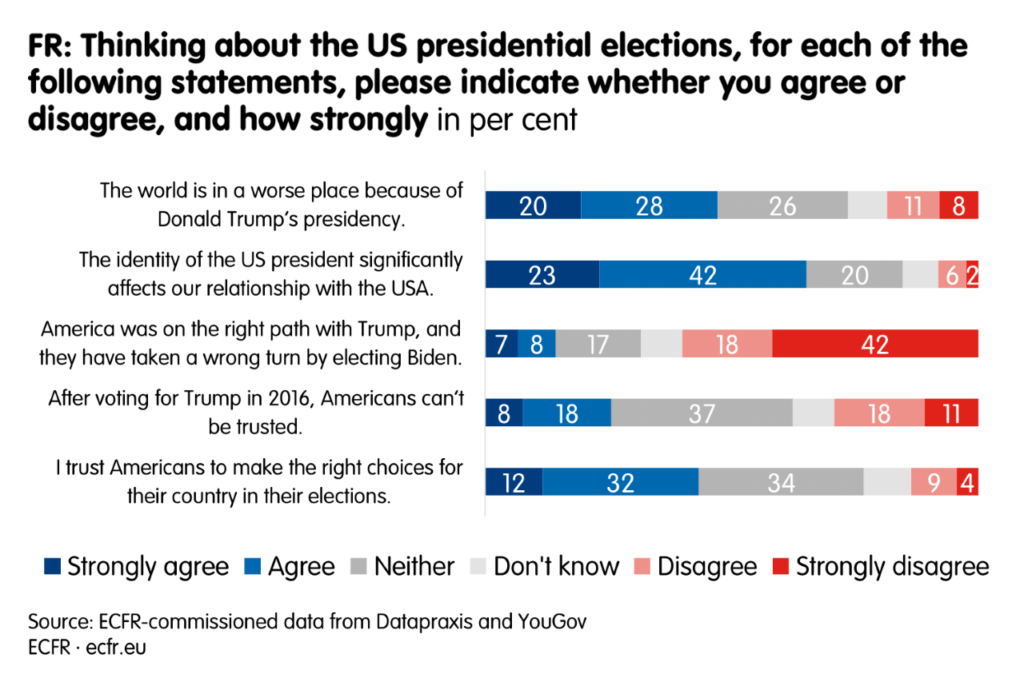

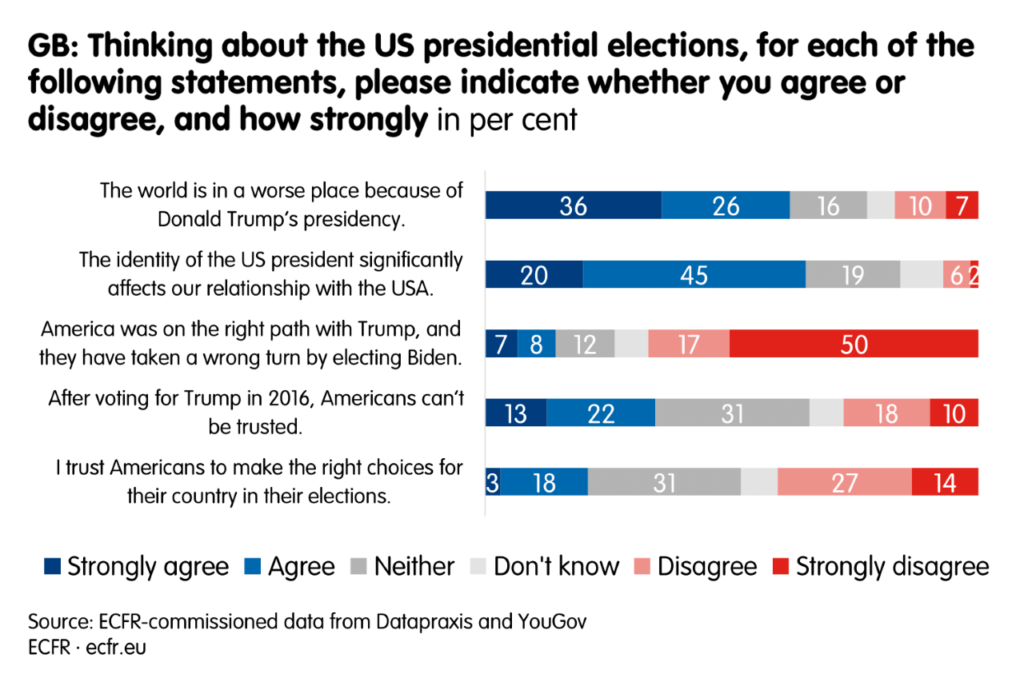

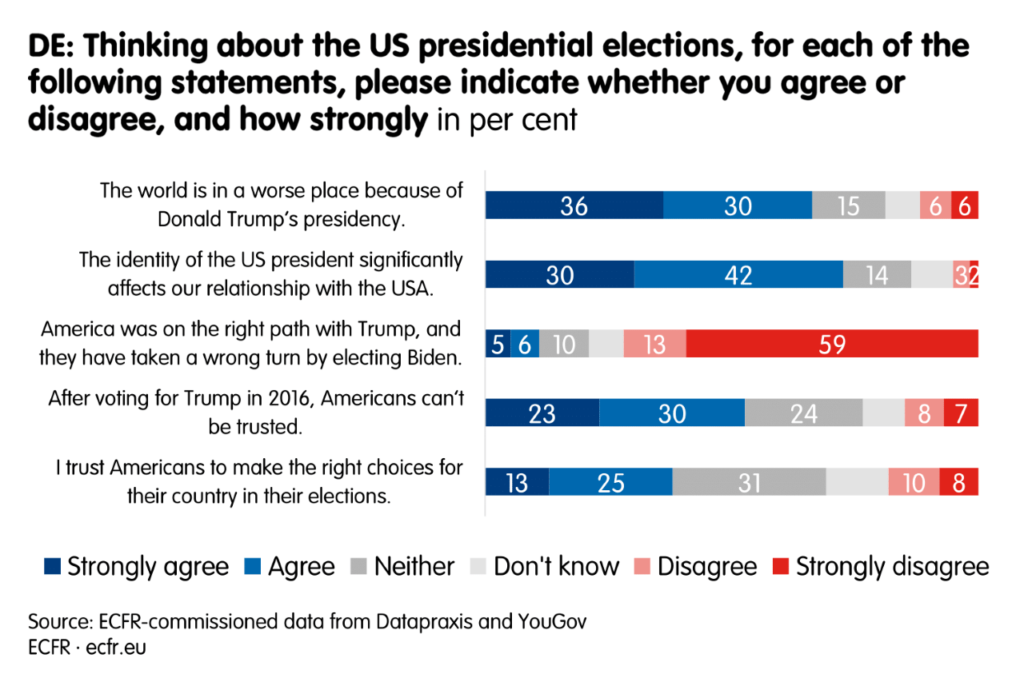

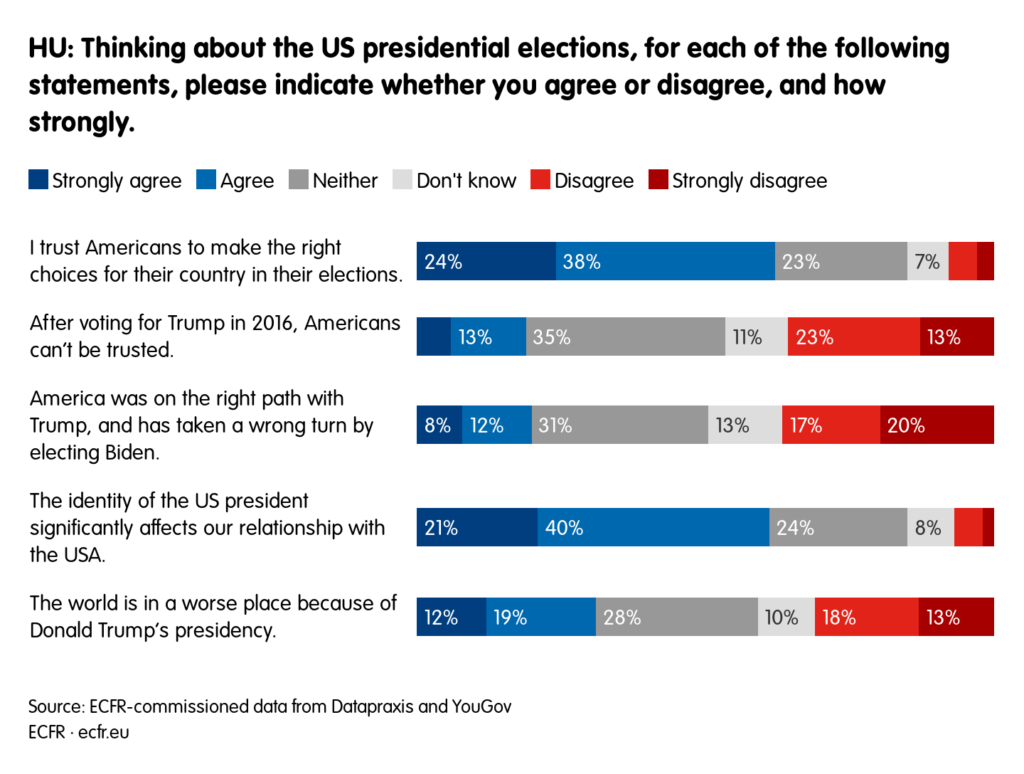

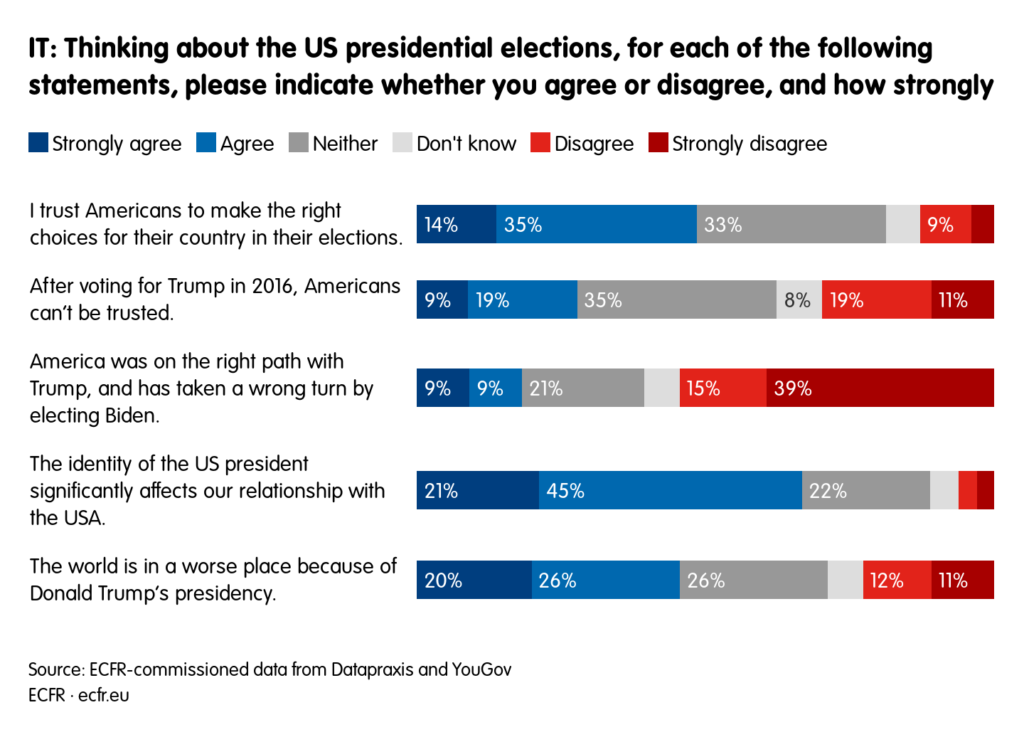

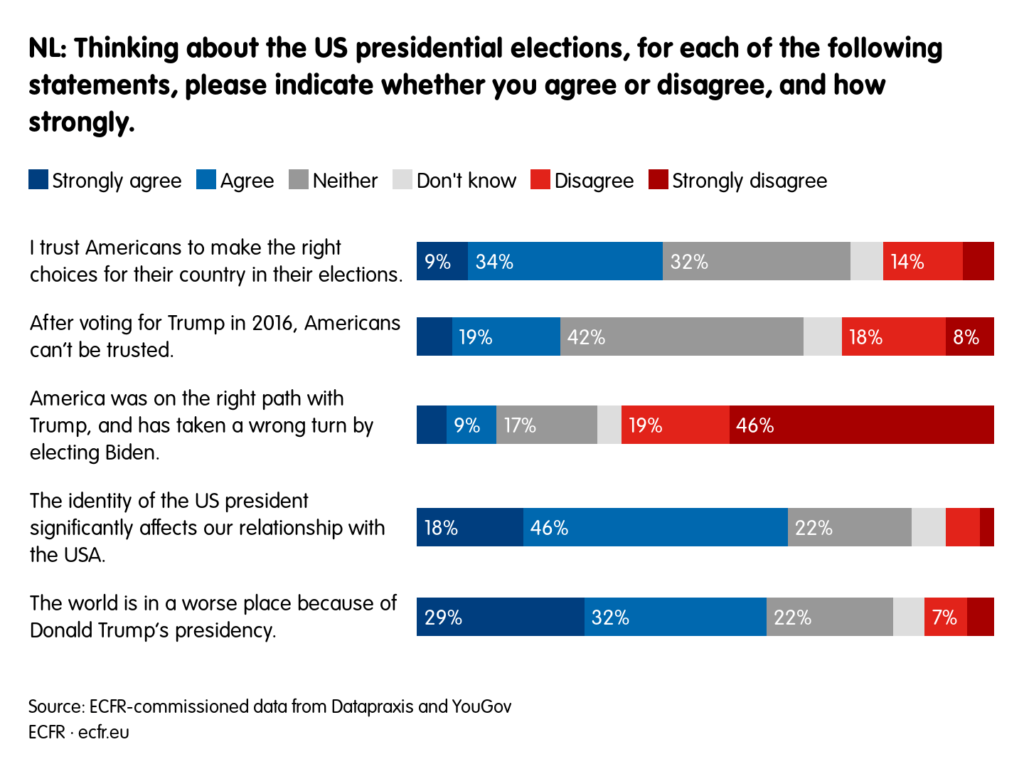

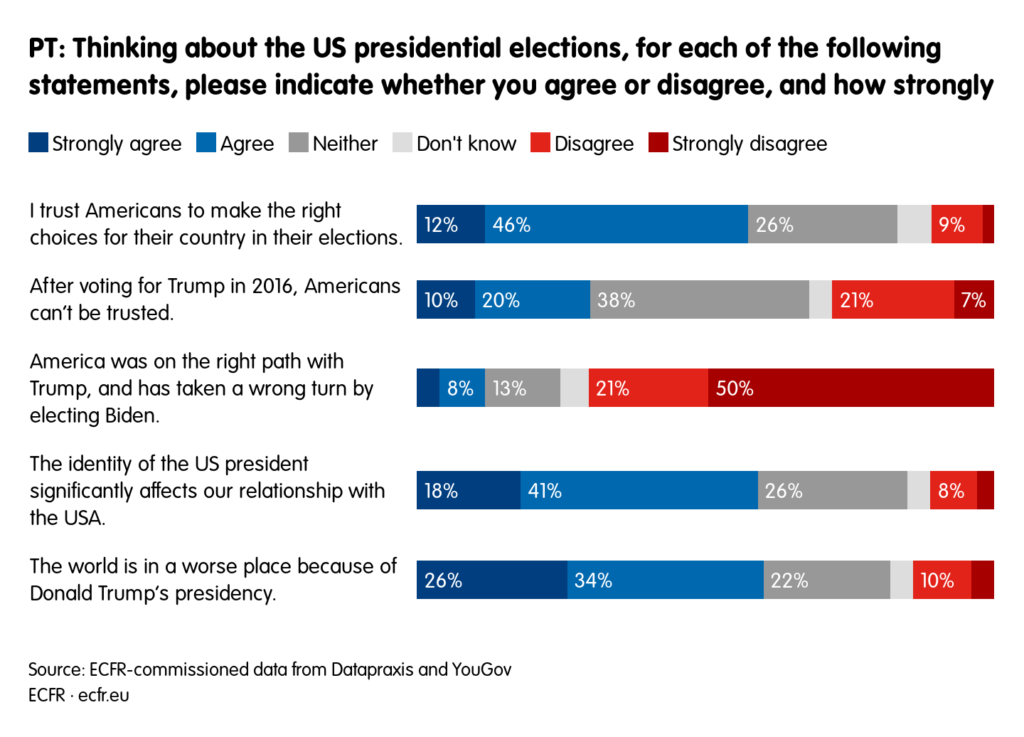

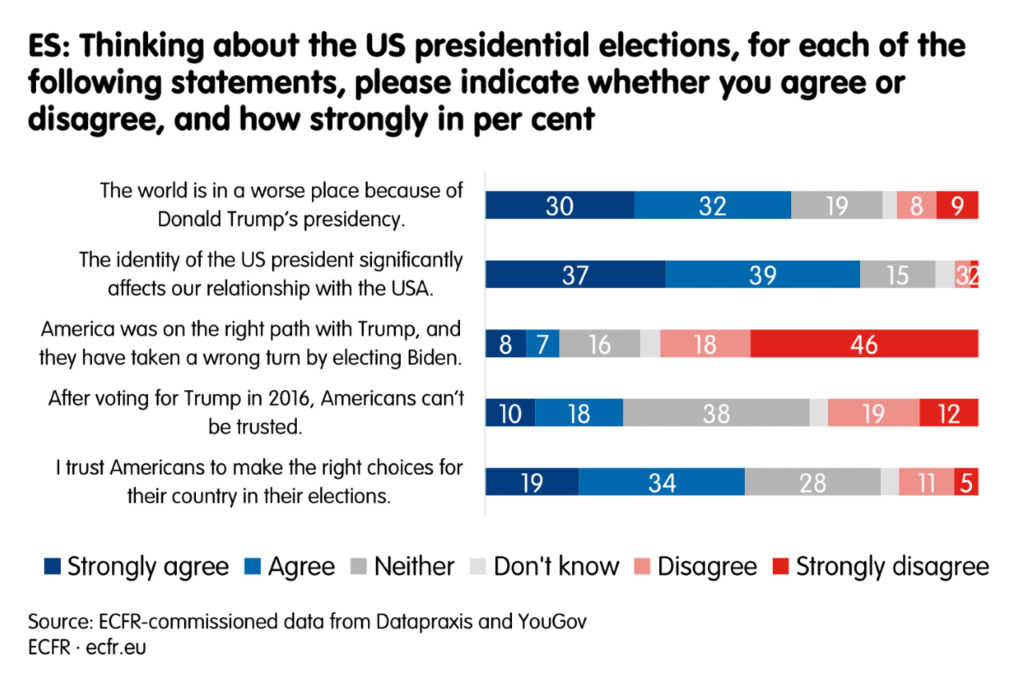

But, although a majority of Europeans are happy with Biden’s election, many do not trust the American electorate not to vote for another Donald Trump in four years. Looking at the results for Europe as a whole, 32 per cent of all respondents to ECFR’s poll agree that, after voting for Trump in 2016, Americans cannot be trusted – and only 27 per cent disagree with this statement (the rest do not have an opinion on the issue). Most strikingly, 53 per cent of German respondents say that, after Trump, Americans can no longer be trusted – making them clear outliers on this point. Only in Hungary and Poland do significantly more people disagree with that statement than agree with it.

Beyond old and new Europe: Europe’s new political tribes

While European countries used to be divided about the US between old and new Europe, our poll shows that there has been a lot of convergence on key questions in public opinion. There are still differences in how Europeans see the US, but they have more to do with perceptions of its relative power than concerns about values. While, at the time of the invasion of Iraq, most Europeans thought their continent was weak and America was strong, the truth is that Europeans are now more positive about themselves and more sceptical about America’s power and political system.

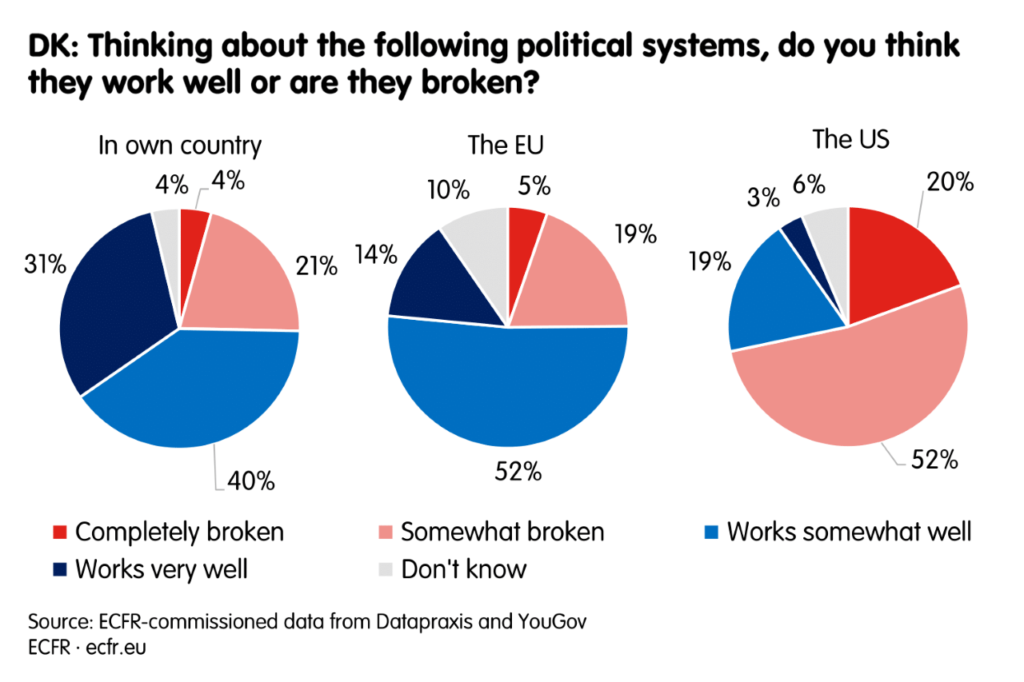

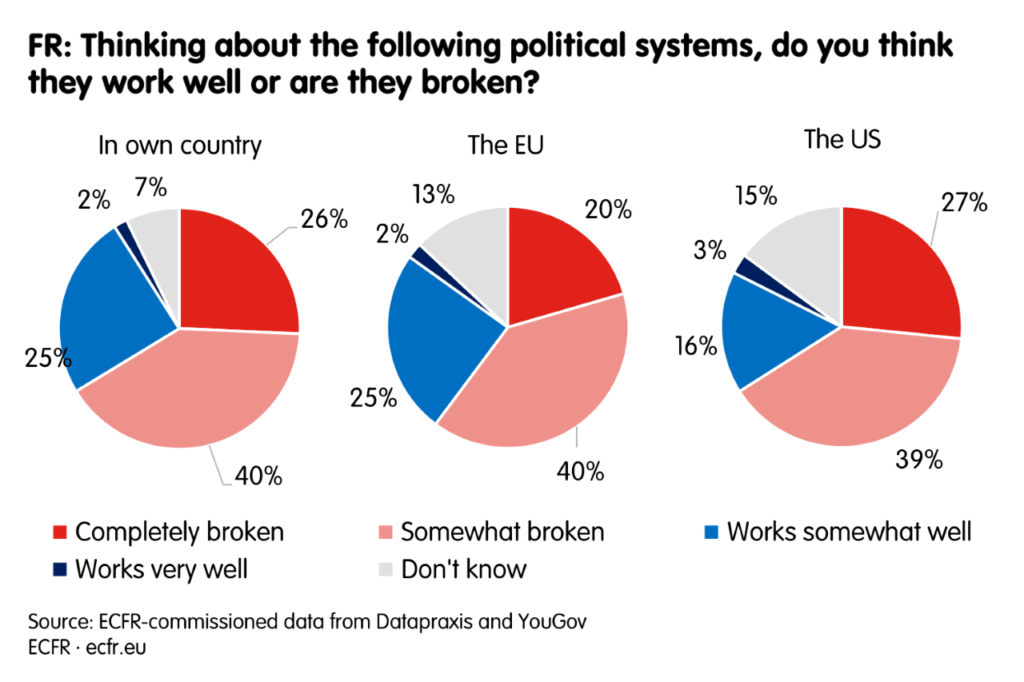

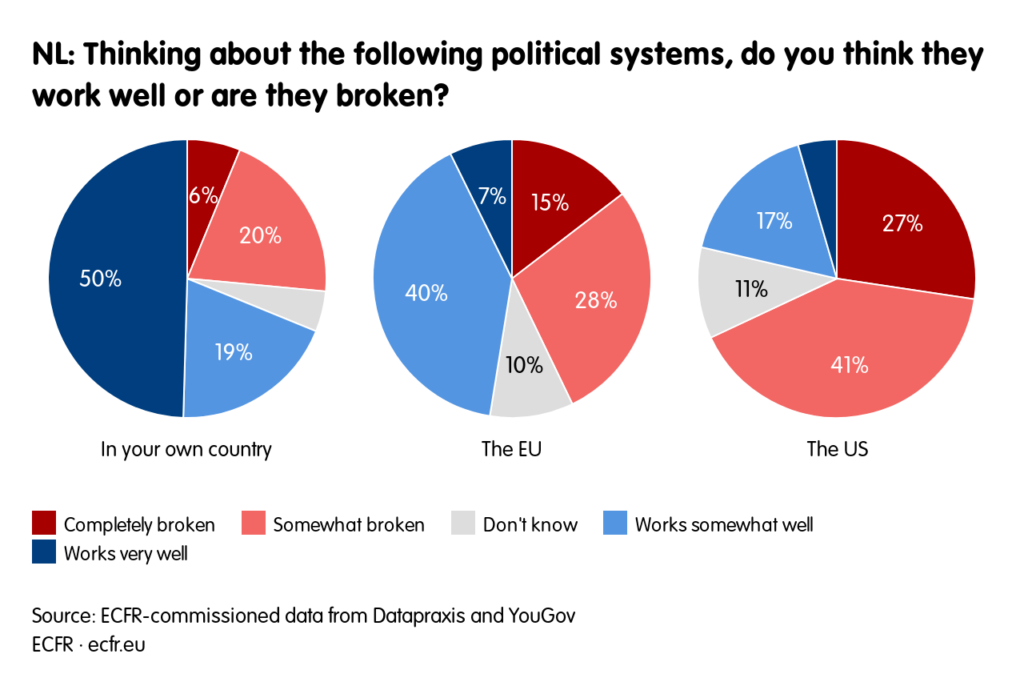

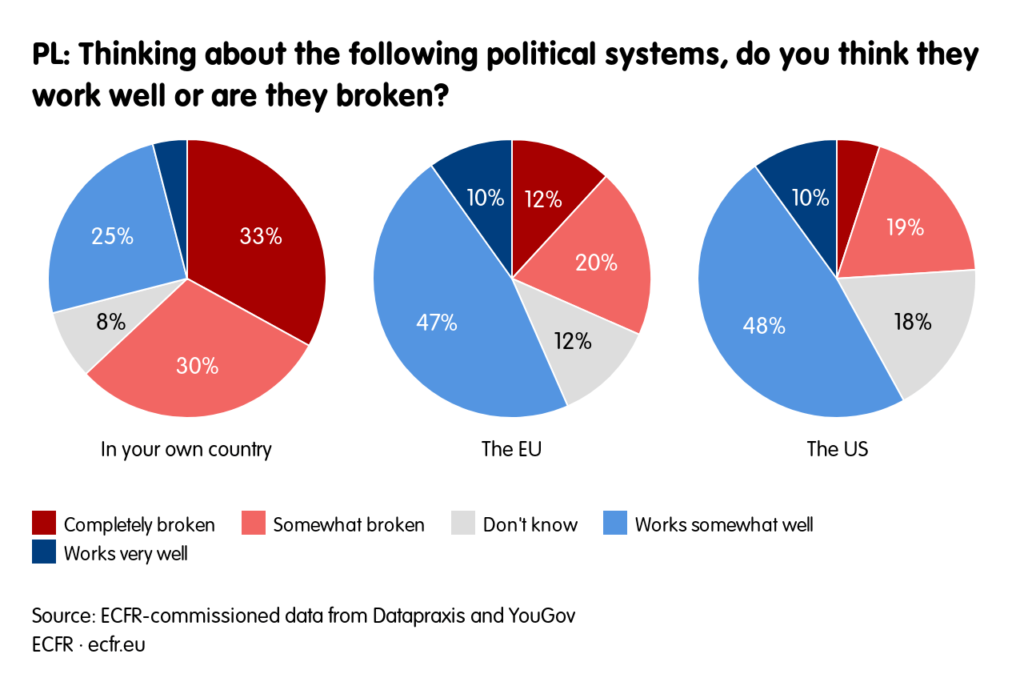

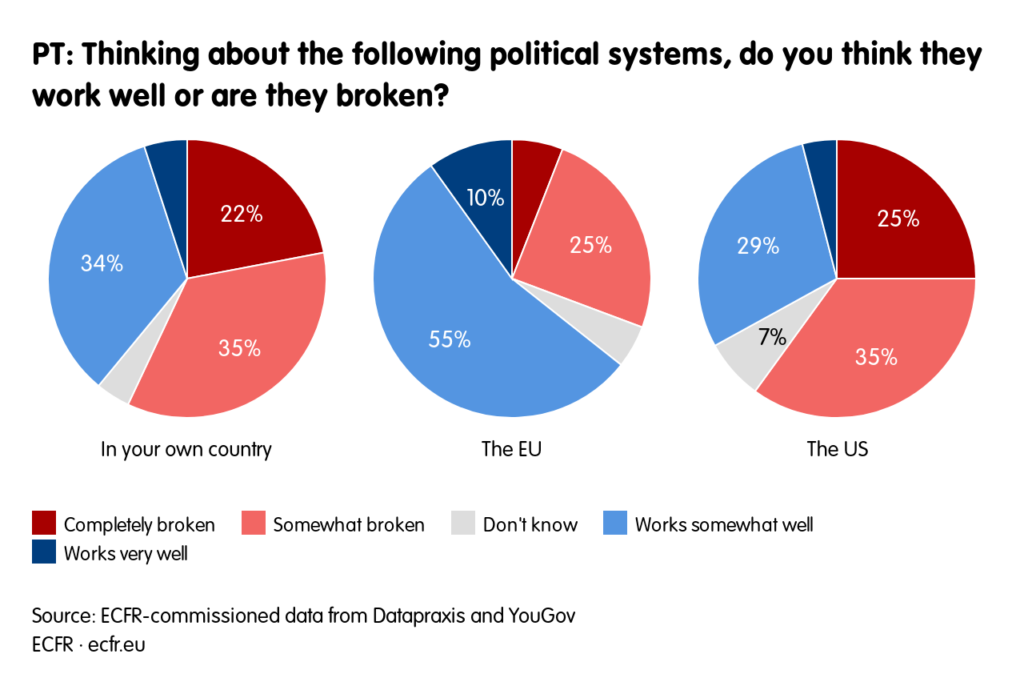

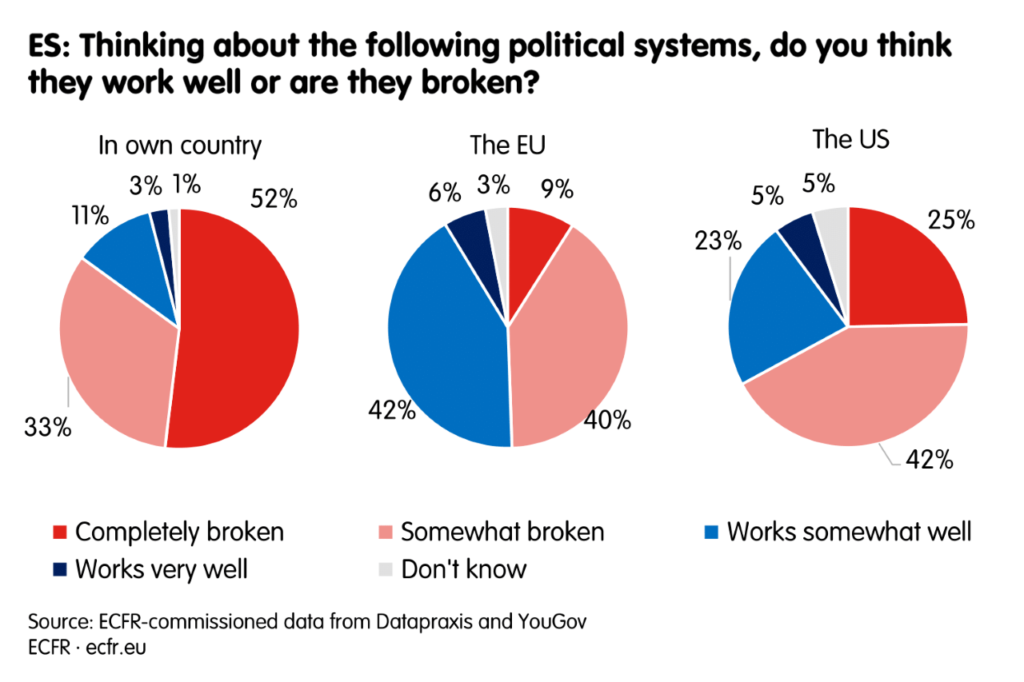

Let’s start with how Europeans see themselves. ECFR’s poll shows that, contrary to expectations, they have become slightly more positive about the EU in the past two years, despite the old continent’s failure to handle the covid-19 crisis. In Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, and Sweden – countries in which ECFR conducted a poll two years ago – the average share of people who say that the EU’s political system works very well or fairly well has increased from 46 per cent to 48 per cent since January 2019. Meanwhile, those who say that the system is somewhat or completely broken has decreased from 45 per cent to 43 per cent during this period. Perceptions of the EU have improved everywhere apart from Hungary, the Netherlands, and Spain.

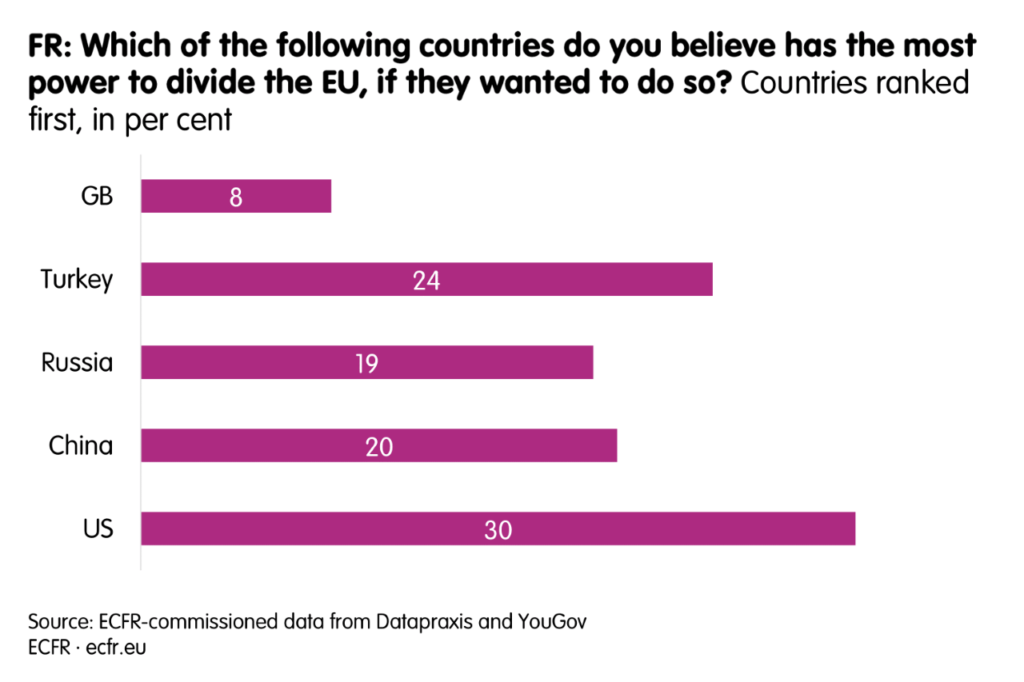

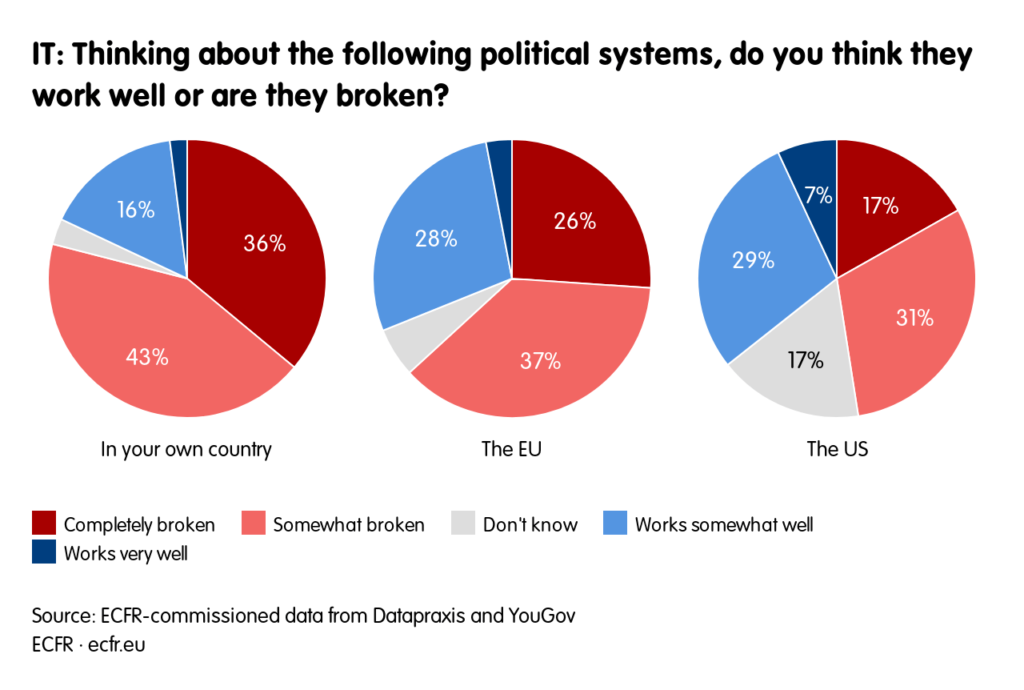

There is a contrast between the moods of Europe’s regions. In southern Europe, a majority say that the EU’s political system is broken. By contrast, a majority of respondents in northern Europe (Denmark, Sweden, Germany, and the Netherlands) and in central Europe (Poland and Hungary) say that the EU system is working. People’s attitudes towards the EU political system often seem to correlate with their views of their own country’s system. In northern Europe, most people are convinced that their national political system is working – and, for many respondents, this correlates with a belief in the success of the EU. In contrast, majorities in Spain, Italy, and France regard both their own political system and the EU’s as broken. Poland, Portugal, and Hungary are exceptions to the rule: majorities in these countries think that their national political system is broken, but they seem to see Brussels as their salvation.

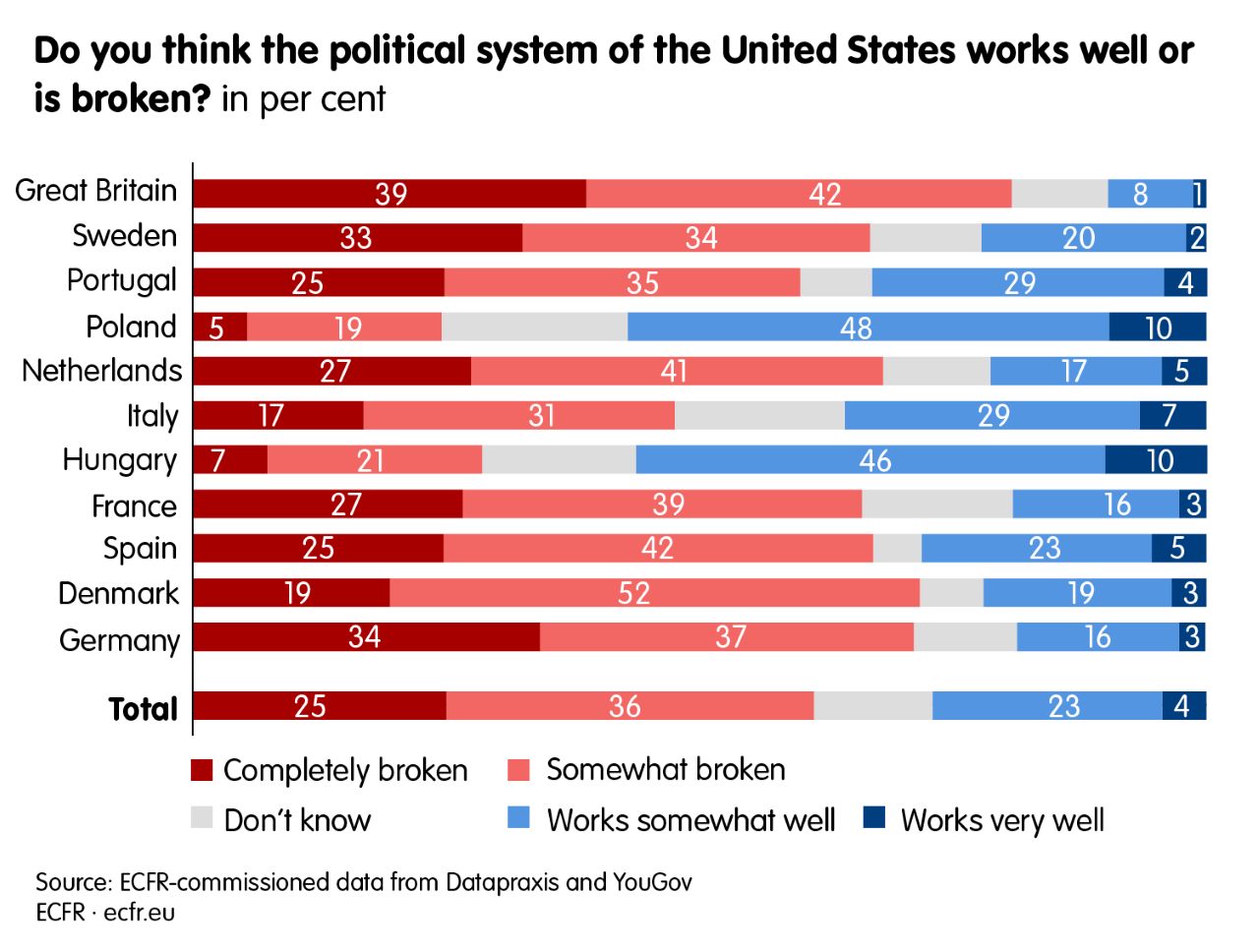

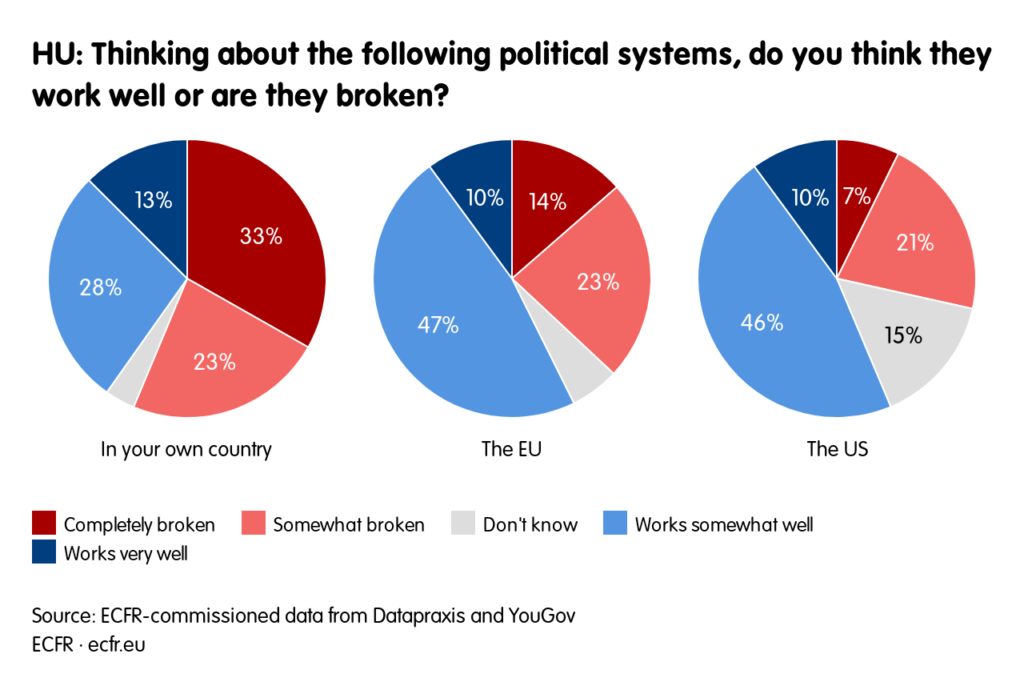

But while Europeans are more positive about the EU, they are very pessimistic about the US. Over six in ten respondents across the 11 surveyed countries believe that the US political system is completely or somewhat broken, and this is also the view of majorities in every country aside from Hungary and Poland (where 56 per cent of Hungarians and 58 per cent of Poles believe that the US political system works well or, at least, somewhat well).

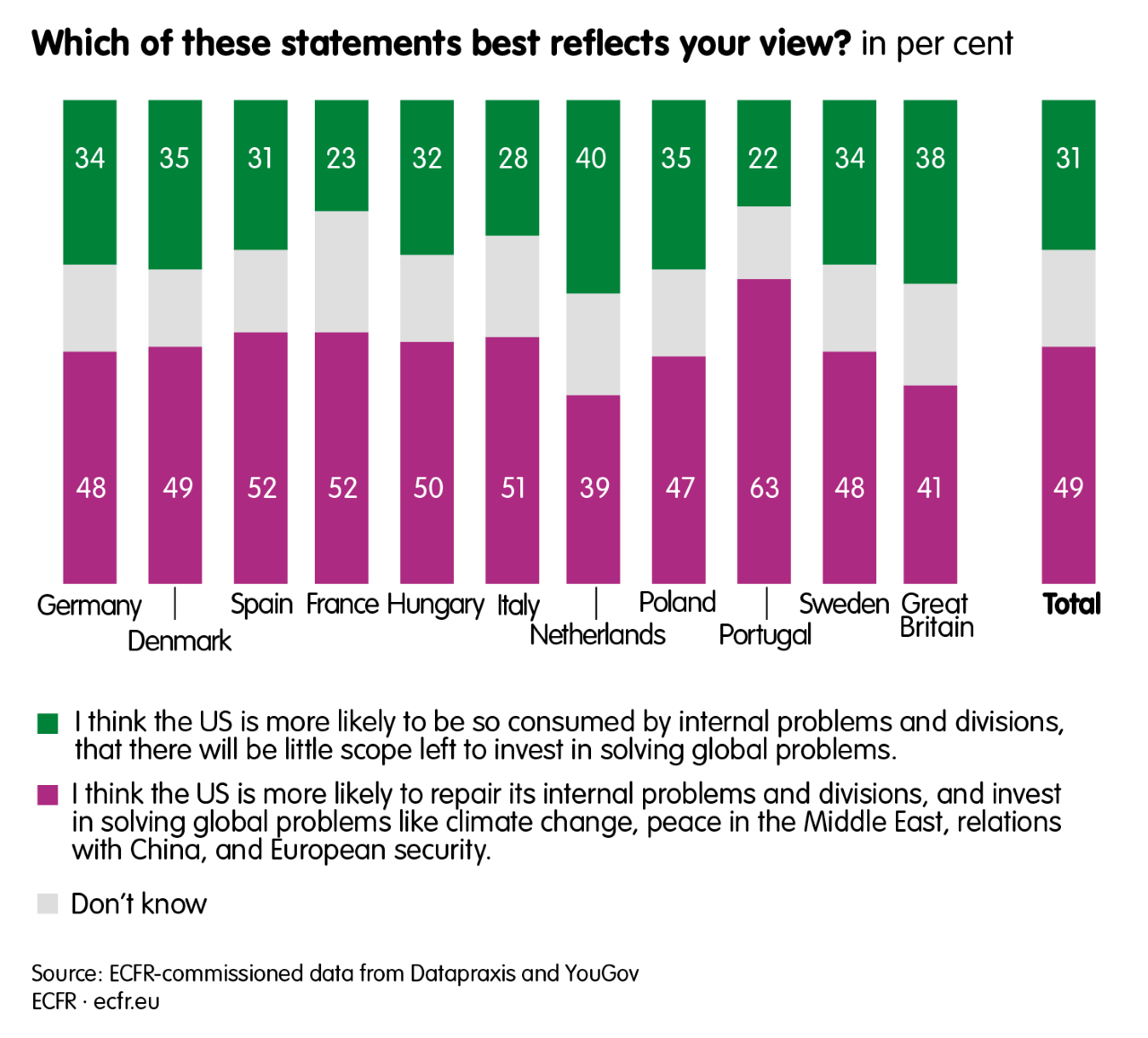

Many Europeans’ perception of the US political system as broken seems to make them doubt whether America will be able to return to global leadership in the manner that Biden promised when he said “America is back”. Across the 11 surveyed countries, 51 per cent of respondents do not subscribe to the view that, under Biden, the US is likely to repair its internal divisions and invest in solving international issues such as climate change, peace in the Middle East, relations with China, and European security.

Across the 11 surveyed countries, six out of ten respondents think that China will become more powerful than the US within the next ten years. The view that China will overtake the US is shared by 79 per cent of the public in Spain, and by 72 per cent in Portugal and Italy. Citizens of Hungary and Denmark are the most optimistic about the future of American power but, even in these two states, 48 per cent of respondents are convinced that China will overtake America in the next decade.

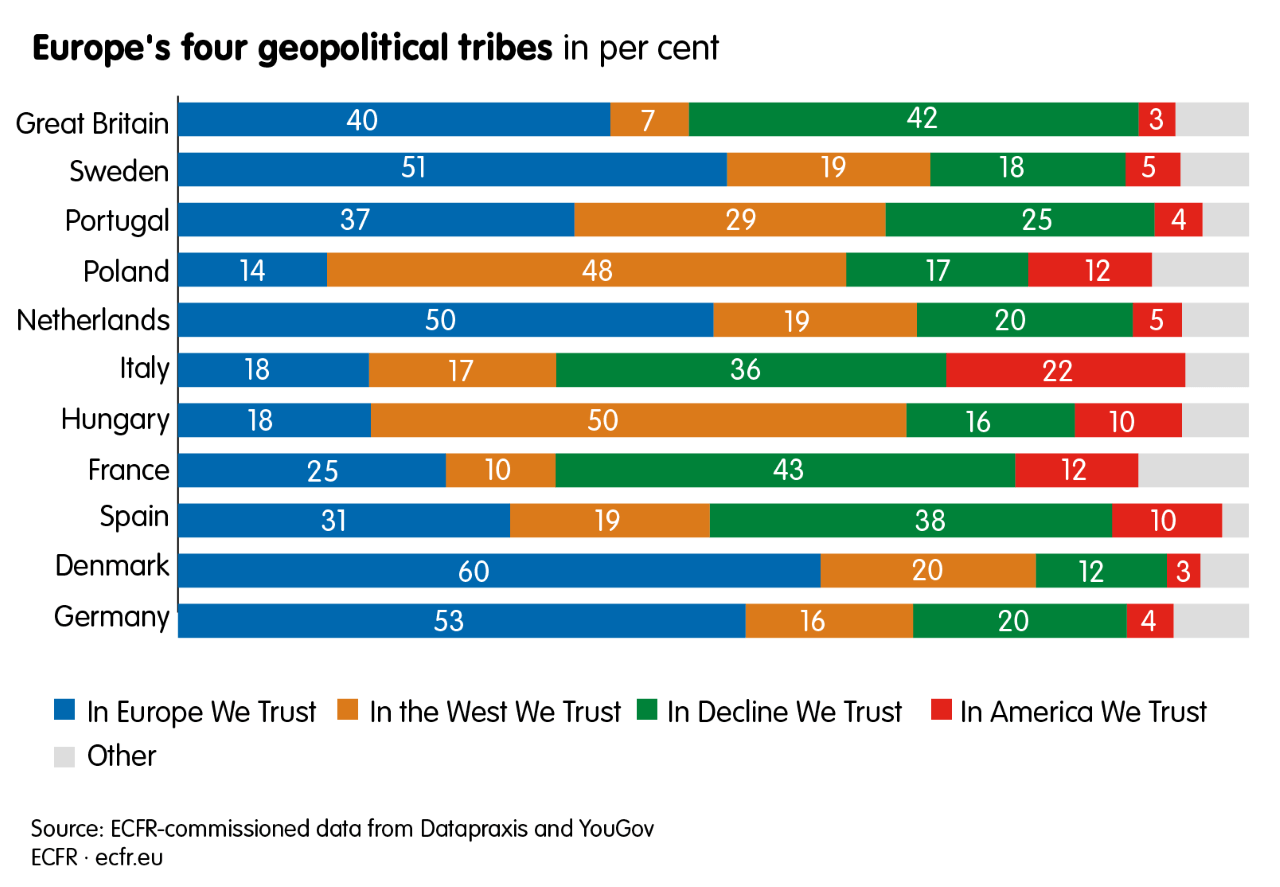

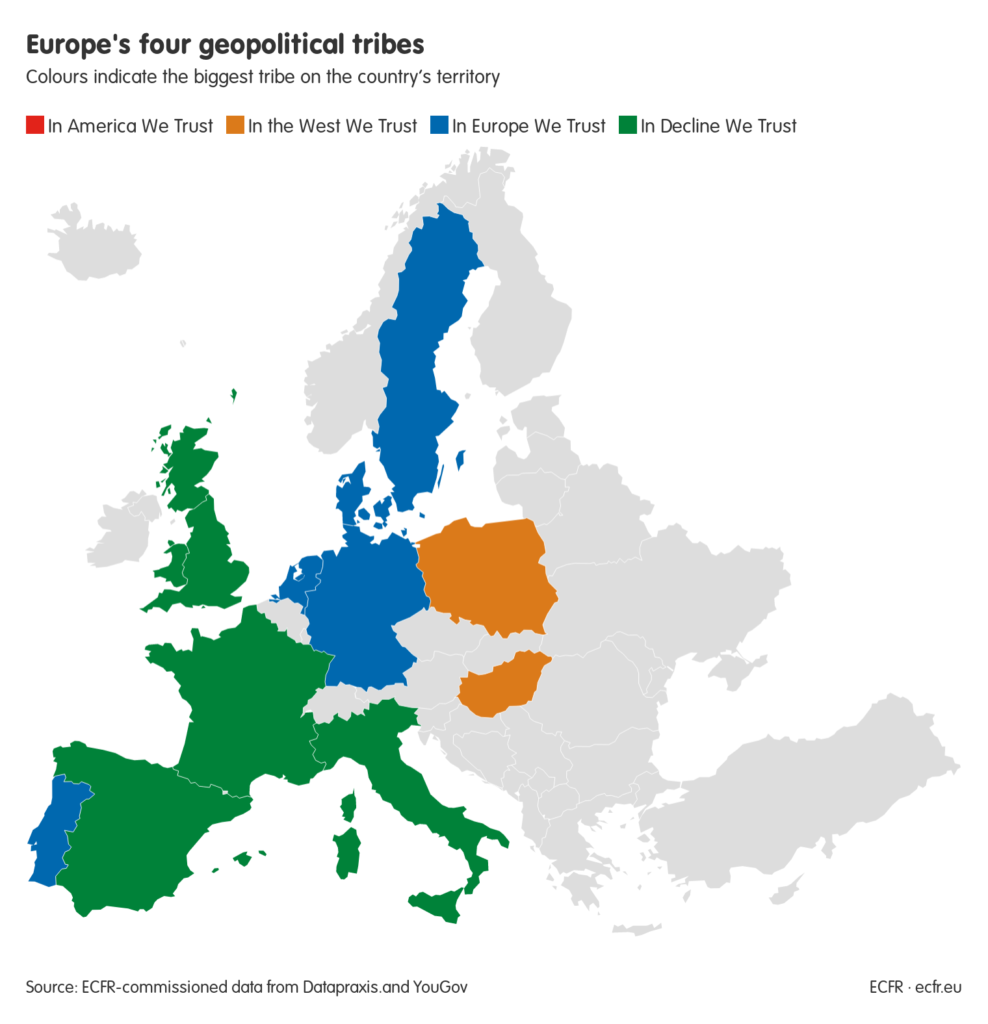

Whereas, at the beginning of the century, European public opinion on the US used to be divided along the lines of Donald Rumsfeld’s ‘old’ and ‘new’ Europe, the current poll shows a great deal of convergence. Many differences between European societies remain, but the clear dividing lines have been blurred. Today’s Europe is populated by four new geopolitical tribes that feel very differently about the functionality of their national political models, the effectiveness of the American political model, and the constellations of political, economic, and military power in the world. Each tribe has representatives in all the countries covered by ECFR’s survey.

‘In America We Trust’ is the smallest tribe, comprising 9 per cent of all respondents. Its members believe that America is strong and working, whereas the EU is broken and declining. One is most likely to run into members of this tribe in Italy, Poland, and France, where 22 per cent, 12 per cent, and 12 per cent of respondents hold this view respectively. Members of this tribe are likely aware of the problems America is experiencing but know that, historically, the US has always bounced back after a crisis. They may have taken to heart Otto von Bismarck’s remark that “God has a special providence for fools, drunks, and the United States of America”; in any case, they believe that America is better positioned than Europe to preserve its influence in the world. Members of this tribe tend to vote for right-wing populist parties. In Italy, they tend to vote for the League, the Brothers of Italy, or Forza Italia; in France, they tend to vote for Marine Le Pen’s National Rally or other right-wing parties and candidates. In the Netherlands, the majority of this tribe is formed of those who vote for the Party for Freedom (PVV) of Geert Wilders or the populist, right-wing Forum for Democracy. In Sweden, most of them vote for the Sweden Democrats. In Denmark, they mostly choose the New Right or the Danish People’s Party.

The second-smallest tribe is ‘In the West We Trust’, comprising 20 per cent of respondents. This tribe is composed of people who say that both the US and the EU are thriving. They are most likely to be convinced of the superiority of the Western political and economic system, and somewhat less likely than other tribes to fear that China will be in the geopolitical driving seat in the future (although, even among this group, 53 per cent think it is likely that China will surpass the US in the next ten years). If one wants to meet these people, the best place to go is central Europe: they constitute almost half of all voters in Poland and Hungary. This tribe is most likely to vote for La République En Marche! or Les Républicains in France; the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) in Germany; the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) or the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) in the Netherlands; the Social Democrats or the conservative-liberal Venstre in Denmark; the Socialists (PSOE), Vox, or the People’s Party in Spain; the Social Democratic Party, the Centre Party, or the Moderates in Sweden; Fidesz in Hungary; Law and Justice in Poland; and the Socialist Party or the Social Democratic Party in Portugal. These believers in the current power of the West make up the youngest tribe across all surveyed countries (58 per cent of them are under 50). However, their distribution across age groups varies between countries. For example, in Hungary, one is as likely to find members of this tribe among those aged 70 or above as among those aged 18-29.

‘In Decline We Trust’ comprises 29 per cent of respondents, making them the second-largest group. Members of this tribe believe that both Europe and America are broken and declining. They are most likely to believe that China will overtake the West as a shaper of international politics (68 per cent believe that China is likely to be more powerful than the US within ten years, and 32 per cent say the same about Russia). These geopolitical fatalists make up the largest tribe in four countries: France (43 per cent of respondents), Great Britain (42 per cent), Spain (38 per cent), and Italy (36 per cent). They tend to be older, with 53 per cent of them over the age of 50. Members of this group are quite widely spread in their voting behaviour, but are more likely to support National Rally or Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise in France; Alternative for Germany or the Left in Germany; the New Right, the Conservative People’s Party, or the Social Democrats in Denmark; Fidesz in Hungary; the PVV, the VVD, or the Socialist Party in the Netherlands; and the Sweden Democrats or the Moderates in Sweden. This tribe also counts among its members many more disengaged or disillusioned citizens, such as those who do not know who they will vote for (particularly in France, Italy, and Portugal) or who say that they will abstain from voting (especially in Spain and Poland). Across all surveyed countries, this tribe accounts for 36 per cent of voters who are undecided or plan not to vote in the next election, and for 36 per cent of those who intend to vote for a populist party – a larger share than that of any other tribe in both cases.

The biggest tribe is ‘In Europe We Trust’, comprising 35 per cent of all respondents. It is made up of people who think that, politically, Europe is healthy while the US is broken. Its members mostly come from more prosperous countries, and it is the largest tribe in Denmark (where it makes up 60 per cent of respondents), Germany (53 per cent), Sweden (51 per cent), the Netherlands (50 per cent), and Portugal (37 per cent). This tribe tends to be better educated than average, and its members are most likely to vote for the CDU/CSU, the Greens, or the Social Democrats in Germany; La République En Marche!, Les Républicains, or the Greens in France; the Democratic Party, the Five Star Movement, or one of the small pro-European centrist lists in Italy; opposition parties such as Civic Coalition, Poland 2050, and the Left in Poland; the Social Democrats or Venstre in Denmark; and governing coalition parties such as the VVD, CDA, and D66, or the centre-left Labour and Green Left parties, in the Netherlands. Across all surveyed countries, 47 per cent of respondents who intend to vote for non-populist parties are in the ‘In Europe We Trust’ grouping.

The policy consequences of American weakness

Most Europeans’ view of America as politically broken and likely to soon be overtaken by China as a global power appears to affect public perceptions of the value of the transatlantic alliance in ways that could have a significant impact on the Biden team. We noticed four profound changes.

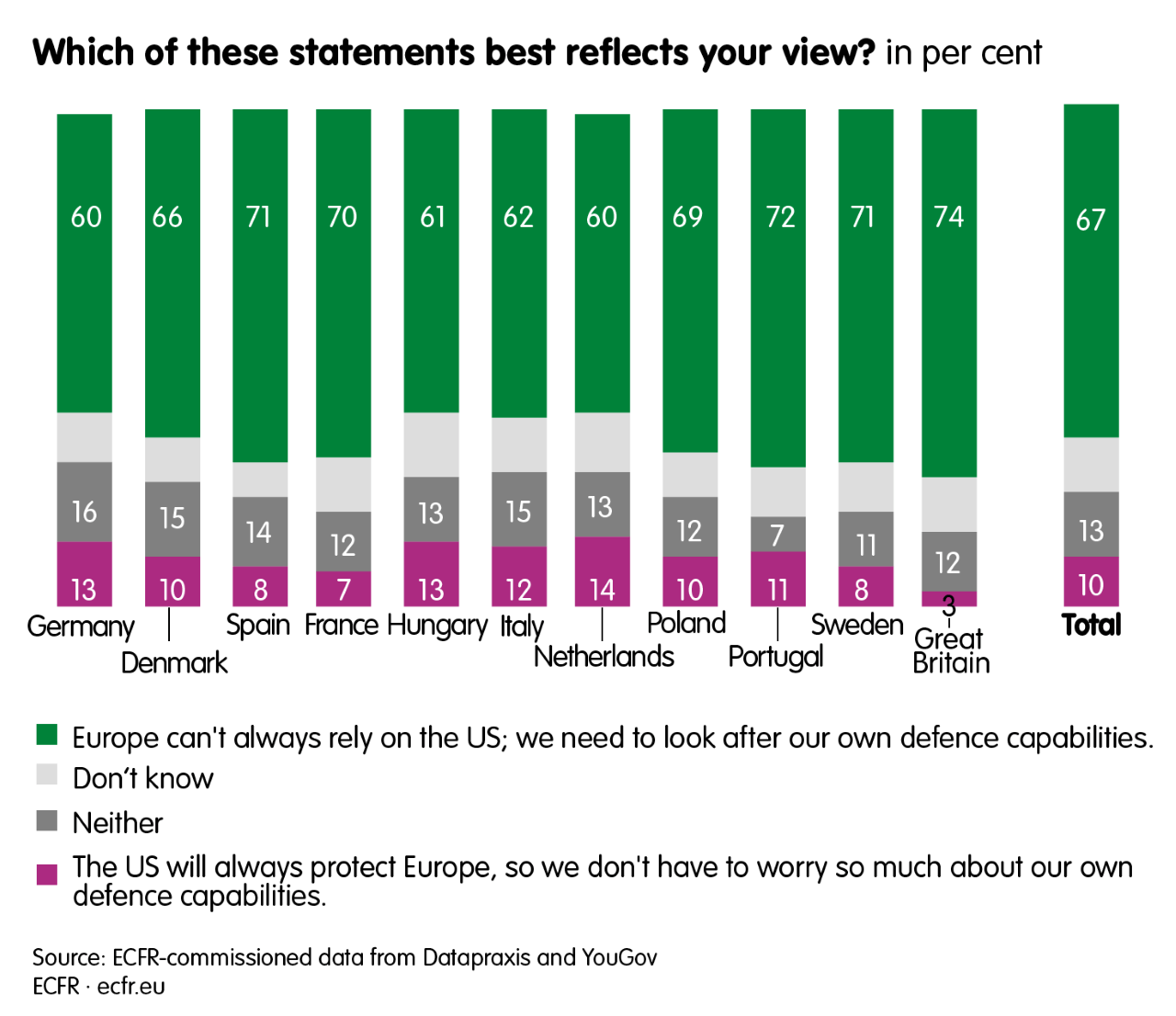

Firstly, the move towards greater self-reliance. One of the most striking findings of ECFR’s survey is that at least 60 per cent of respondents in every surveyed country – and an average of 67 per across all these countries – believe that they cannot always rely on the US to defend them and, therefore, need to invest in European defence. Interestingly, 74 per cent of British respondents hold this view – a higher share than in any other national group.

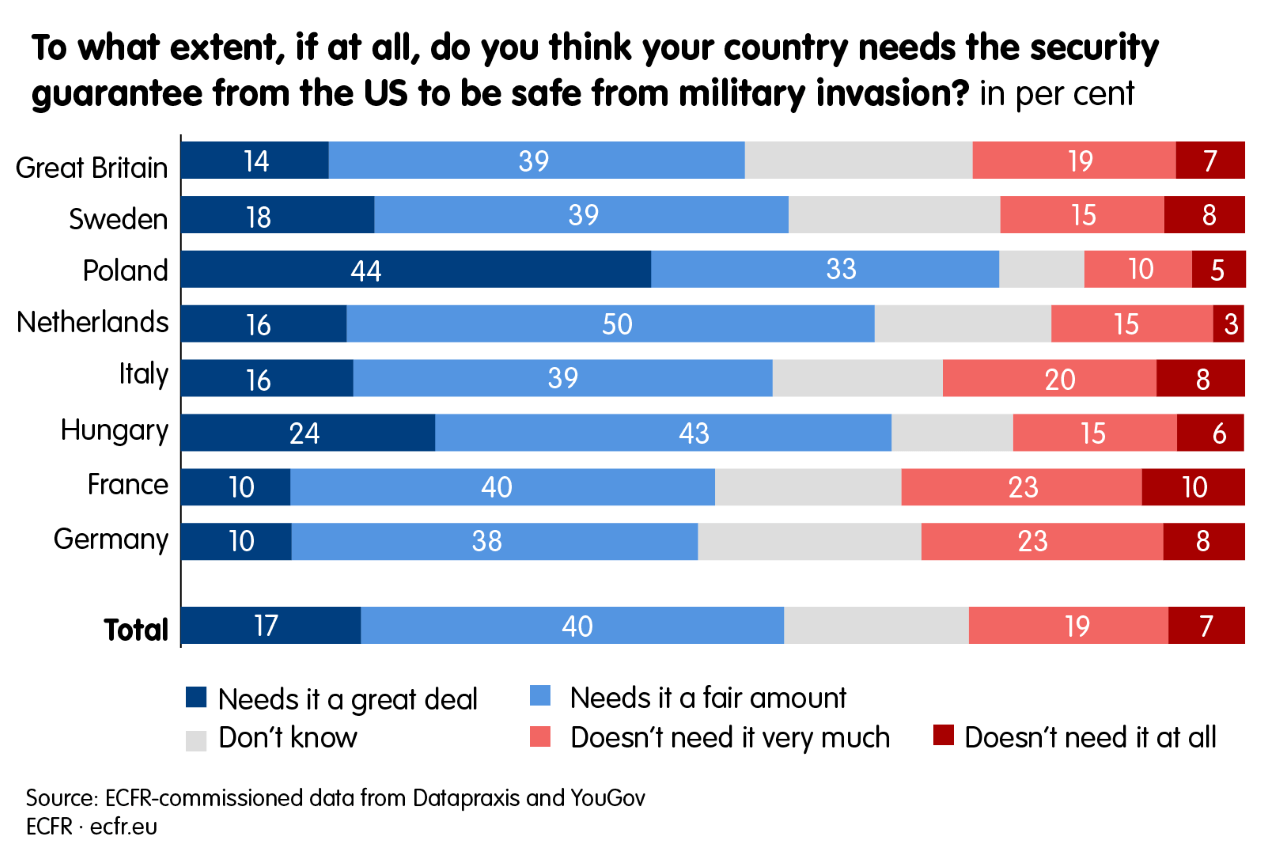

ECFR’s opinion poll also reveals a change in threat perceptions across Europe, most dramatically in Germany. During the cold war, Germany felt threatened by invasion and was, therefore, wedded to the Atlantic alliance. But, nowadays, Germans seem to have caught up with the French (whose country has the strongest military in the EU and is a long-time proponent of European defence integration) in feeling less of a need than other Europeans for the US security guarantee. Currently, only 10 per cent of respondents in France and Germany say that their country needs the American security guarantee “a great deal” to be safe from military invasion. Only in Poland do a substantial number of respondents (44 per cent) believe that they need this guarantee “a great deal”. Therefore, it seems that Germany’s – and Europe’s – transatlantic policy in the years to come could be influenced not only by the country’s increasing economic ties with China but also by the fact that over half of the German public does not now see US military power as an existential guarantee of its security.

The second big surprise is around the question of geopolitical alignment. Biden has called for the US and Europe to form a united front against China and thereby shape its rise. But ECFR’s poll shows that, in today’s Europe, there is no dream of a return to a bipolar world in which the West would face off against China and its allies as it once did against the Soviet Union.

Troubled by doubts about America and influenced by Trump’s focus on narrowly defined national interests, European voters have started to think differently about the nature of the transatlantic alliance. In 2019 ECFR conducted a pan-European poll that indicated that a large majority of respondents in all surveyed countries wanted to remain neutral (rather than align with Washington) in a conflict between the US and China or Russia. Many people around Biden may have hoped that his victory in the November election would have changed that dynamic. They may have assumed that Europeans’ shift towards neutrality could be explained by their mistrust of, and disgust with, Trump.

However, ECFR’s latest poll shows that political change in Washington does not appear to have fundamentally altered respondents’ calculus about geopolitical alignment. At least half of the electorate in every surveyed country would like their government to remain neutral in a conflict between the US and China. This even applies in Denmark and Poland, the two countries with the highest proportions of people who would like to take the United States’ side – 35 per cent and 30 per cent respectively. This may reflect the fact that, although both Europeans and Americans are toughening up their approaches to China, their long-term goals are somewhat different. While Americans want to do so to decouple from and contain China, Europeans (above all Germans) still hope to bring China back into the rules-based system.

Europe’s unwillingness to side with the US also comes out in respondents’ views on a conflict between the US and Russia: in no surveyed country would a majority want to take Washington’s side. Amazingly, only 36 per cent of respondents in Poland and 40 per cent in Denmark say that their country should side with the US in such a scenario. Across the 11 surveyed countries, just 23 per cent of respondents hold this view – while 59 per cent want their country to remain neutral. In Denmark and Poland, neutrality is the preferred option of 47 per cent and 45 per cent of voters respectively.

This shift in perceptions might have as much to do with power as anything else. What Europeans love about the memory of cold war 1.0 is that they were on the winning side; the fear in many European countries is that cold war 2.0 might have a different outcome. The growing mistrust about Washington’s reliability and power is changing the nature of the transatlantic alliance. America’s cold war coalitions took the form of a Catholic marriage. They were meant to be monogamous, with no possibility of divorce. After four years of Trump, the alliance looks like a more casual arrangement – an open marriage in which bringing in other players is the key to not being exploited. Europeans no longer trust America to defend Europe and would express little solidarity with the US if it became involved in a conflict with other great powers. Reading ECFR’s survey, Washington will also have no reasons to trust European publics’ readiness to conduct a joint transatlantic foreign policy.

The third consequence of changing perceptions of power is a desire to be less sentimental in dealings with the US. A perverse effect of Trump’s term in power is that, by ruthlessly focusing on the national interest, he has encouraged other players – including Europeans – to concentrate more on protecting their own interests at the expense of focusing on the broader common interests of the democratic West. This is reflected in many Europeans’ desire to invest in defending themselves. There has also been a marked change in how people regard the transatlantic economic relationship. Among the eight countries in which ECFR asked voters about this issue, pluralities in Germany (37 per cent), France (48 per cent), Great Britain (37 per cent), and Italy (42 per cent) think that their country should be tougher with the US on economic issues such as international trade, the taxation of multinational companies, and the regulation of digital platforms. Poland is the predictable outlier on this point, with just one in ten voters saying that their country should become tougher with the US on economic issues.

This prevailing mistrust is also changing the ways that Europeans relate to one another – the fourth big policy consequence that comes out of our poll. As they no longer see Washington as a reliable partner, Europeans are looking to one another more than they once did. This raises the issue of whether Berlin will replace Washington as the ‘go-to’ capital. Given the size and importance of the ‘In Europe We Trust’ group, it is not surprising that respondents in France, Spain, Denmark, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Hungary were most likely to choose Germany as the most important country to build a good relationship with, above the US (while, for their part, 38 per cent of Germans chose France as their most important ally, and only 35 per cent preferred the US). Only respondents in Great Britain (55 per cent), Poland (45 per cent), Italy (36 per cent), and Sweden (36 per cent) are more likely to rank the US first over Germany on this measure; but, in Sweden, an almost equal share, 35 per cent, rank Germany above the US.

Conclusion: Towards a new Atlanticism

As he left office early in the twenty-first century, Bill Clinton declared that the key task for Americans would be “to create a world we would like to live in when we are no longer the world’s only superpower”. It is fair to say that the US and Europe have failed to do this. As Biden enters the White House, the US is no longer the only superpower. And the world he governs in – marked by the rise of authoritarian powers and the spread of nationalism and inequality – is not the one that either Americans or Europeans would prefer to live in.

Since the disastrous 2003 war in Iraq and the 2008 global financial crisis, Washington has been facing up to the end of the unipolar moment. Trump and his predecessor, Barack Obama, are probably the most different American presidents one can imagine. But their analyses of America’s position in the world had much more in common than most people recognise. Both of them understood that America’s ambition to remain the world’s only superpower was unsustainable. Both acknowledged the centrality of geo-economics in the twenty-first century. And both recognised that they would need to work with political regimes that did not share America’s values and norms.

But their responses to this situation were strikingly different. Obama was convinced that the best way to preserve America’s leadership was to embed Washington in a diverse and well-developed network of military and trade alliances. This is why the Obama administration’s negotiations on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership went hand in hand with its quest to seal a Trans-Pacific Partnership. Obama hoped that, by using these tools, America would gain the upper hand over China and reinvent its role for the future.

Trump’s bet was that, if the international order had stopped working for America, it was in Washington’s interest to act as the disrupter-in-chief and to organise the world around asymmetrical bilateral relations with other powers. While the US remains the most powerful country in the world, it can still dictate terms to any other player – providing them with deals one at a time. While Obama believed that America’s strength lay in its networked alliances, Trump believed that they were chains that kept America down.

The Biden administration is coming to power at a moment when Trump’s “America’s First” policy has failed to provide Washington with greater global influence, while a return to Obama’s strategy is not viewed as realistic because of America’s unreliability and waning power. A majority of Europeans doubt that Biden can put Humpty Dumpty back together again.

Alliances are born of interests and values but, like any other human relationship, they are sustained or broken by the prevailing moods of the partners. So, what does ECFR’s new opinion poll reveal about the future of the transatlantic relationship in the post-Trump world?

The good news is that there is widespread optimism among Europeans after the 2020 US election that the transatlantic partnership has a future. The bad news is that Europeans are sceptical about America’s efforts to regain its influence and contain the rise of China. “Without the Cold War, what’s the point of being an American?”, Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, the novelist John Updike’s late-twentieth-century everyman, asked as the “long twilight struggle” was winding down. Many people in America now see the prospect of a new cold war as giving their foreign policy a new focus. But Europeans are asking themselves exactly the opposite question: “what is the point of being a European if the cold war has returned?”. The perspective of a new cold war with China is deeply unattractive to the Europeans we surveyed. It is not that Europeans are pro-China. A previous ECFR poll has shown that Europeans are not attracted by the Chinese model, and the pandemic has made clear China’s hegemonic ambitions.

But Europeans appear keen to forge their own path rather than fall into line behind America’s China policy. The largest number of those surveyed in this and previous polls seem to support the idea of a more sovereign and autonomous Europe. However, while European leaders tend to view European sovereignty as reflecting a desire to play a more important role in global politics – regardless of whether they support the idea – that is not the case for a large number of European citizens. There is a substantial group for whom ‘European sovereignty’ is code for a drive towards neutrality in the escalating competition between the US and China. For these citizens, European sovereignty is not a grand entry into international politics but an emergency exit from the bipolar world of tomorrow. It is an application for early retirement from great power competition.

This is where public opinion will have an impact on elite politics. During the cold war, European governments were willing to face down public opposition to align with a US that defended them from the Soviet Union. But each president since the end of the cold war has found it harder to persuade European leaders to spend political capital on their alliance with Washington. Europeans were certainly more willing to patch over their differences with Obama than those with George W Bush, but this did not extend to real concessions on the management of the 2008 financial crisis or increases in defence spending. While all European governments will try to build a close relationship with the Biden administration, they will not feel that they have public support to make major concessions on high-profile issues of national importance.

The main lesson of ECFR’s poll is for the Biden team. The new American administration has a clear idea of how Trump’s four years have changed America, but they should be aware of the Trump effect on Europe’s geopolitics of emotions. Although Europeans will not mourn Trump’s electoral defeat, his legacy will persist long after he has left the White House. Even as Biden seeks to overturn the isolationism and unpredictability of the Trump administration, he will be hampered by policies that made America seem volatile, selfish, and weak. There is now a unique opportunity to revive and transform the transatlantic alliance – but one cannot seize this with unconvincing promises of restoration and bipolarity. A new transatlanticism is needed – one based on a common understanding that the US-Europe alliance is not enough to reshape the world. Leonard Cohen once sang “The mist leaves no scar / On the dark green hill”. But our poll shows that Trump was no fog; he has left scars. And Biden’s presidency will be marked by them.

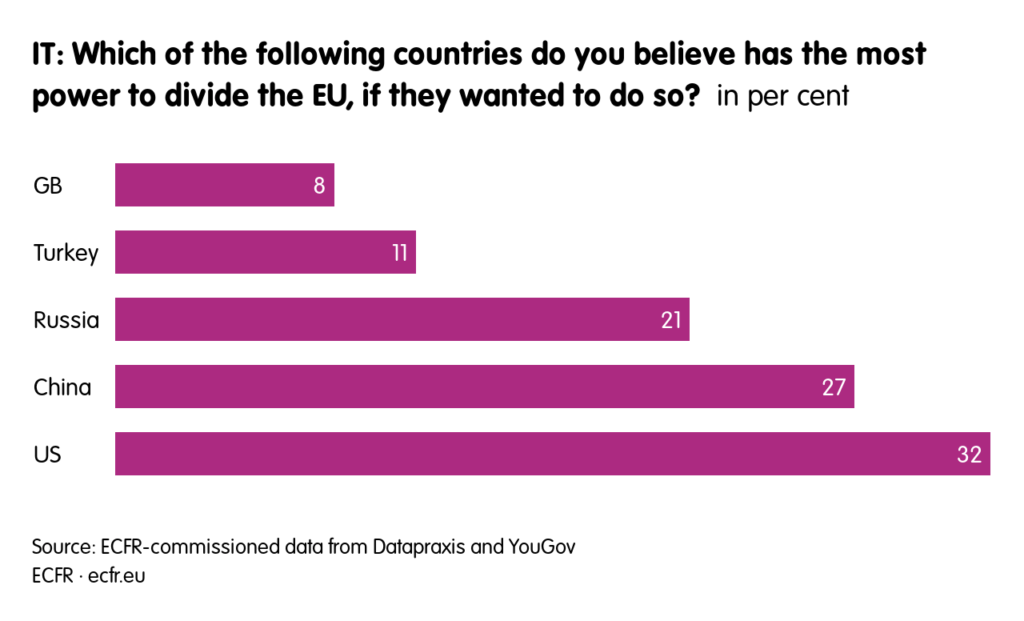

Charts by country

Denmark

France

Great Britain

Germany

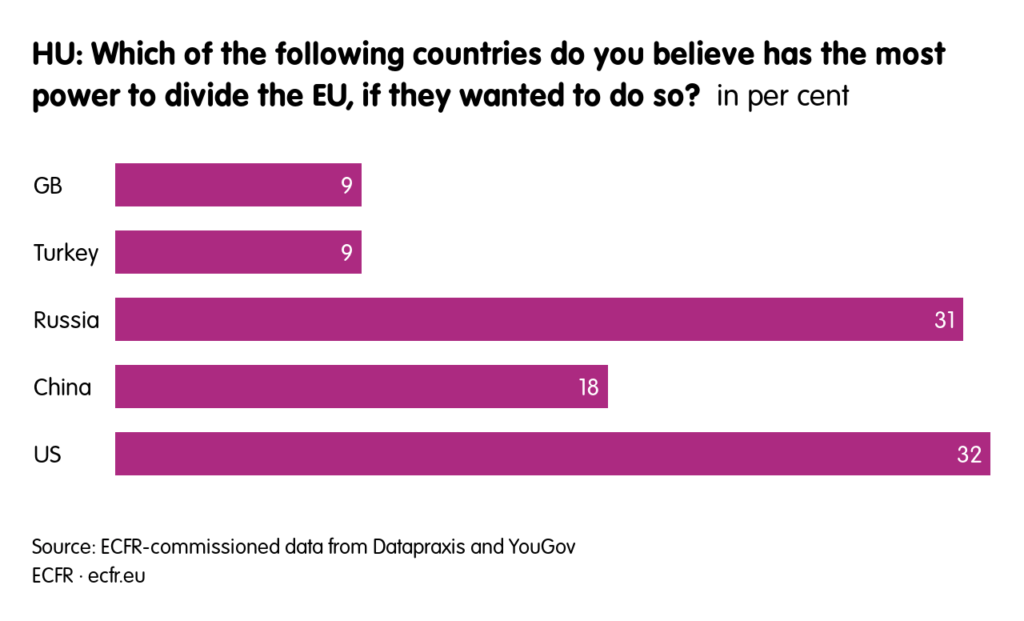

Hungary

Italy

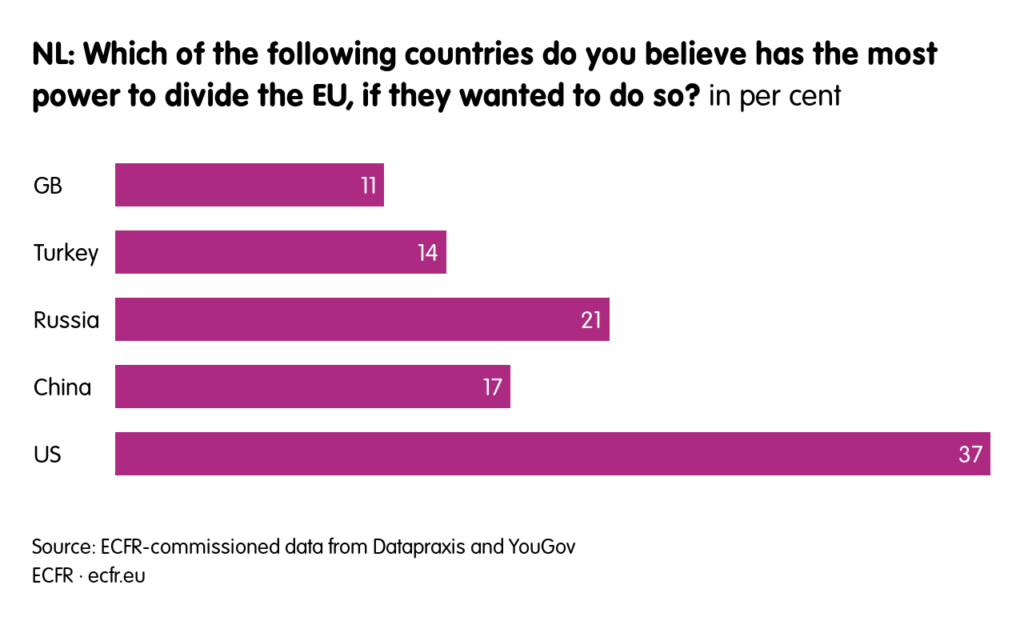

The Netherlands

Poland

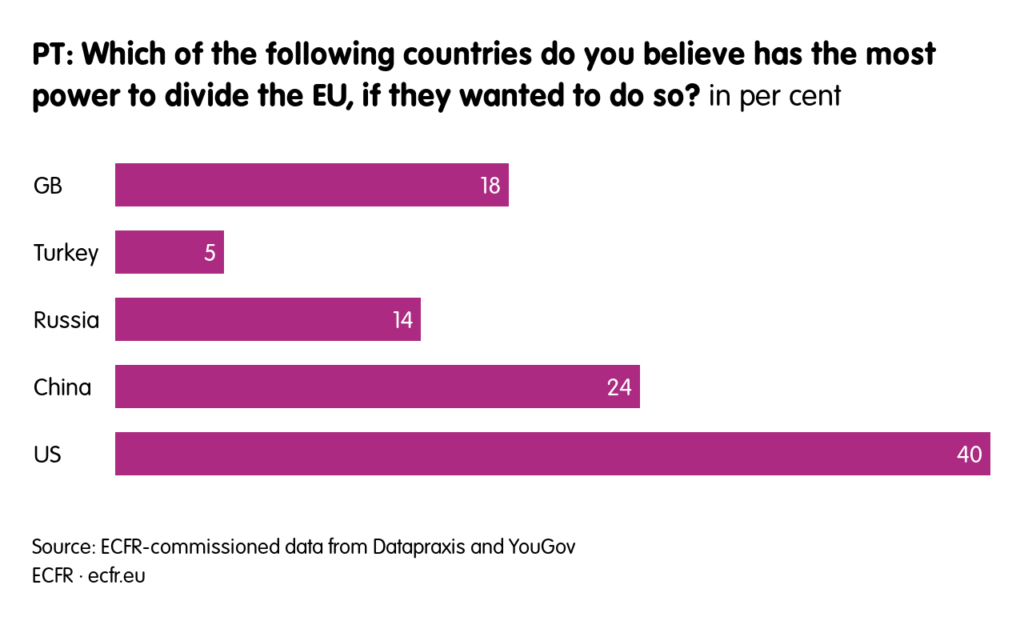

Portugal

Spain

Sweden

Methodology

This paper is based on a public opinion poll in eleven EU countries carried out for ECFR by Datapraxis and YouGov in late November and early December 2020.

This was an online survey conducted in Denmark (n = 1,037), France (n = 2,013), Germany (n = 2,060), Hungary (n=1,001), Italy (n=2,017), Netherlands (n = 1,005), Poland (n = 1,002), Portugal (n=1,004), Spain (n=1,017), Sweden (n = 1,010), and the GB (n=2,031). The results are politically and nationally representative samples.

The general margin of error is ±3% for 1,000 sample, and ±2% for 2,000. YouGov used purposive active sampling for this poll.

The exact dates of polling were: Denmark (20-25 November), France (25-26 November), Germany (25-27 November), Hungary (24 November – 2 December), Italy (24 November – 3 December), Netherlands (24 November – 2 December), Poland (24 November – 7 December), Portugal (24 November – 7 December), Spain (20-25 November), Sweden (24-27 November), and the GB (24-25 November).

The segmentation presented in this paper is based on respondents’ views on whether the political system of the United States, and the one of the EU, are broken or working well. The table below presents the segmentation’s grid.

| US working | US broken | |

|---|---|---|

| EU working | In the West We Trust | In Europe We Trust |

| EU broken | In the US We Trust | In Decline We Trust |

For those who responded ‘don’t know’ to the question about the US political system, responses to two other questions (on the US’s capacity to repair its internal problems and divisions; and on whether China, Russia, or the EU are capable of overcoming the US power in the next decade) were used to allocate some of these respondents to either the ‘US broken’ or the ‘US working’ group. For those who responded ‘don’t know’ to the question about the EU political system – or who saw the EU political system as only ‘somewhat’ broken – responses to one more question (on whether the political system of their own country is working well or broken) were used to allocate some of them to either the ‘EU broken’ or the ‘EU working’ group.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this report are hugely grateful to colleagues across the ECFR network for all their input into the research and production of this report. In particular, we would like to thank Susanne Baumann and Susi Dennison for leading the Unlock project so brilliantly. Vessela Tcherneva and Jeremy Shapiro oversaw the entire programme and research management with their customary brilliance, while Piotr Buras, Jana Puglierin, José Ignacio Torreblanca, Tara Varma, and Arturo Varvelli gave us vital advice and insights from their national capitals. Pawel Zerka and Philipp Dreyer were responsible for the data analysis and allowed us to learn many things from it. Lucie Haupenthal was the perfect partner throughout the writing process, helping steer our progress, trying to pin down our emerging insights in successive drafts, and being an amazing research assistant and intellectual sparring partner. Swantje Green and Andreas Bock provided inspiring and tireless work on Unlock that helped this project make an impact in the world. Chris Raggett has been an exemplary editor. We would also like to thank Paul Hilder and his team at Datapraxis for their patient collaboration with us in developing and analysing the dataset and to YouGov for conducting the fieldwork. We are grateful to Think Tank Europa, and particularly Catharina Sorensen for their collaboration and support on the research for this report, and to the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation for their generous funding. Despite all these many and varied inputs, any errors in the report remain the authors’ own.

About the authors

Ivan Krastev is chair of the Centre for Liberal Strategies, Sofia, and a permanent fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna. He is co-author of The Light That Failed: A Reckoning, among many other publications.

Mark Leonard is co-founder and director of the European Council on Foreign Relations. He is the author of Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century and What Does China Think?, and the editor of Connectivity Wars. He presents ECFR’s weekly World in 30 Minutes podcast.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.