Free to choose: A new plan for peace in Western Sahara

Summary

- The recent violent end of the ceasefire in Western Sahara means the EU and the UN should pay renewed attention to resolving the longstanding conflict between the native Sahrawis and Morocco.

- Various peace-making efforts over the years have led the Sahrawis’ representative organisation, Polisario, to make concessions to Morocco. However, Morocco remains insistent on an autonomy option for the Sahrawis – not independence.

- The UN should pursue a “free association” option for Western Sahara – a third way that offers a realistic means of fulfilling Sahrawi self-determination.

- France, along with the US, should encourage this by removing their diplomatic protection for Morocco both within the EU and at the UN.

- Correctly aligning the EU’s political and trade relations will be vital to bringing this conflict to a close. It is in EU member states’ interest to ensure a stable southern neighbourhood.

Introduction

This year marks the thirtieth anniversary of the creation of the UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO). The mission was originally tasked with laying the groundwork for Sahrawi self-determination while monitoring a ceasefire between Morocco and Polisario – the Western Sahara national liberation movement. In setting up the mission, the United Nations promised to end the long-running conflict in what remains Africa’s only territory still awaiting decolonisation. Yet, three decades later, the UN has little to show.

Self-determination for the Sahrawi people appears more remote than when MINURSO was first launched in 1991. Meanwhile, the ceasefire is unravelling after the resumption of armed attacks by Polisario against Moroccan forces, stemming in large part from the absence of a viable peace process and the strengthening of Morocco’s hold over the territory. Diplomatic inaction has been compounded by the lack of a UN personal envoy, two years since the most recent appointee resigned in May 2019.

The UN Security Council and its permanent members, which have shepherded peace talks since the 1990s, hold much responsibility for this state of affairs. Under their watch, self-determination and decolonisation were replaced with a peace process that has given Morocco veto power over how the Sahrawi people fulfil their internationally recognised rights.

Stuck on the sidelines has been the European Union. The actions of two of its members, France and Spain, have helped keep the conflict rumbling on. Yet, as a bloc, the EU has maintained its distance from peace talks despite the implications that Western Sahara’s future will have for north-west Africa, whose stability and prosperity is a key European interest. To the extent that it has been involved in Western Sahara – through its trade relations with Morocco – the EU has actually harmed prospects for resolving the conflict. Europe is far from an uninvolved observer; indeed, it is directly implicated in the conflict. Bearing testament to this is Morocco’s recent decision to allow thousands of migrants to make for the Spanish North African town of Ceuta in response to Spain’s hosting of Polisario leader, Brahim Ghali, for medical treatment and (in Rabat’s eyes) because of Spain’s insufficient support for Moroccan positions on Western Sahara. This summer’s anticipated decision by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) to invalidate the EU’s inclusion of Western Sahara in its trade and fishery agreements with Morocco is yet another sign of how implicated the bloc is in the unfolding conflict.

International neglect is having an adverse impact on the calculations of both main parties, demonstrating to Morocco that the UN Security Council has acquiesced to its continued control over Western Sahara. Moreover, in his final weeks as US president, Donald Trump recognised Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara – in contravention of international law. Receding prospects for a negotiated solution will convince the Western Sahara national liberation movement that diplomacy and international law have failed it, and that an intensification of armed confrontation with Morocco is the only way forward.

Drawing on interviews with serving and former officials, and with leading experts and academics, this paper argues that, at this critical juncture, European governments – including those with a seat on the UN Security Council – must urgently relaunch a viable UN-led peace process. In doing so, they should avoid repeating the mistakes of old. They must put their full weight behind the appointment of a UN personal envoy tasked with formulating a new plan for Sahrawi self-determination. This plan should set out a third way for Western Sahara – between full independence and formal integration into the territory of the Kingdom of Morocco – based on the concept of “free association” in which Polisario, as the representative of the Sahrawi people, delegates powers both to Morocco and to a newly created state of Western Sahara. A UN-backed process cannot succeed without the active political support of European governments. How they align their political and trade policies will greatly influence the prospects for resolving the Western Sahara conflict and the future of the region.

Decolonisation interrupted

During European powers’ “scramble for Africa” in the 1880s, Spain established what would become its colony of Spanish Sahara. By the mid-1960s this was known as Western Sahara, and the UN recognised it as a “non-self-governing territory” under Spanish administration – with its people yet to attain a full measure of self-government. Both Mauritania and Morocco, recently independent, were also pursuing irredentist claims on the territory.

The indigenous Sahrawi nationalist movement began to emerge at this time, eventually adopting its most coherent and durable political form as Polisario, which took up arms against the Spanish administration in Western Sahara in 1973. Under pressure from Polisario military actions and international calls to fulfil Sahrawi self-determination, in 1974 Spain finally announced its intention to organise a referendum on Western Saharan independence, and soon began to conduct a census. Though Madrid had worked hard to cultivate a following of loyal Sahrawi elites to govern an independent Western Sahara aligned with Spanish interests following the proposed referendum, a UN General Assembly visiting mission later confirmed in the summer of 1975 that there was “considerable support” for Polisario and an “overwhelming consensus” in favour of independence.

Spain’s announcement of a referendum on decolonisation precipitated a year-long crisis with Morocco, which continued to advance its claims to the territory – which it had been making since achieving independence from France in 1956 – by supporting proxy forces on the ground and taking its case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). In October 1975, the court resoundingly dismissed “any tie of territorial sovereignty” between Western Sahara and either Morocco or Mauritania, while categorically affirming the Western Saharans’ right to choose how to fulfil their self-determination.

Hours after the ICJ opinion was released, Morocco’s King Hassan II declared his intention to seize Western Sahara by force. This became known as the “Green March” and eventually led to Morocco’s annexation of the territory. Wanting to avoid a direct confrontation with Rabat, Madrid reneged on its promise of a referendum. Instead, it brokered an agreement in November 1975 to cede control to Morocco and Mauritania in return for economic concessions relating to the territory’s phosphate reserves and fishing rights. In early 1976, Spain claimed to have transferred its status as the administering power to Morocco and Mauritania, a move that was never recognised by the UN. Moroccan and Mauritanian forces had already begun occupying the territory and they clashed with Polisario fighters in late 1975. This precipitated a refugee crisis that saw around 40 per cent of the native Sahrawi population flee to southern Algeria, where they remain to this day in camps near the town of Tindouf. Since then, Morocco has provided economic incentives to its citizens to settle in occupied Western Sahara.[1]

Though Algeria was disinclined to support Polisario during the movement’s initial years of armed activity against Spain, from 1975 onward Algiers threw its full weight behind the Sahrawi liberation movement due to the strategic threat that it increasingly saw from an emboldened and expansionist Morocco. The two countries had engaged in a border war in 1963 and then moved further apart due to ideological differences between Morocco’s conservative monarchy and Algeria’s socialist republic. Cold war geopolitics further exacerbated these tensions. While Algeria was well disposed to Sahrawi calls for self-determination and resistance to foreign domination, which echoed its own founding principles, it also saw a means to pressure its main adversary.

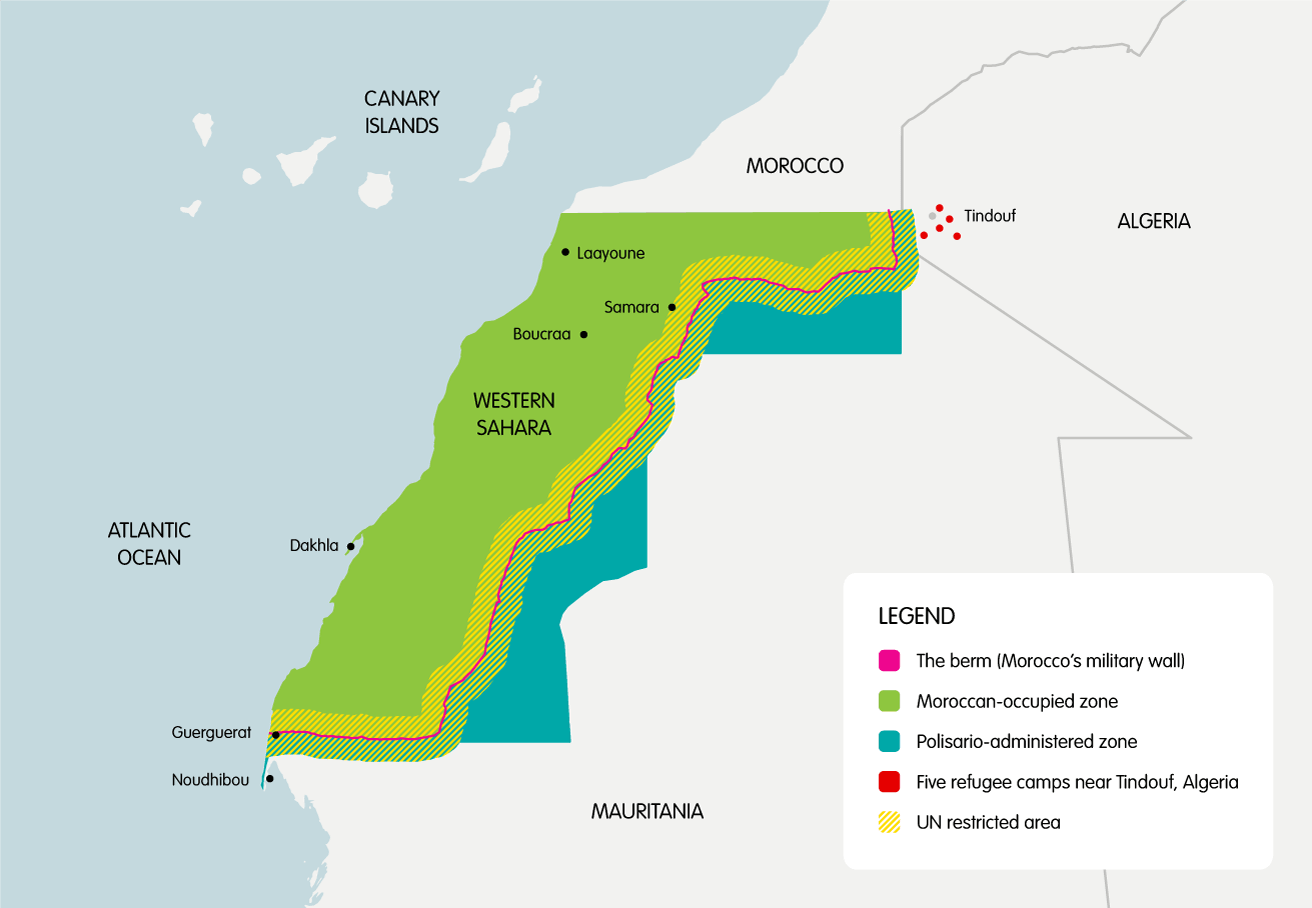

With increased backing from Algiers, Polisario was able to quickly drive Mauritania out of Western Sahara while engaging Morocco in an asymmetric war of attrition. With near-absolute freedom of movement, in the late 1970s and the early 1980s, the highly mobile Sahrawi guerrillas were able to attack and retreat at will in both Western Sahara and southern Morocco. Backed by France and the United States, and financed by Saudi Arabia, Morocco’s armed forces eventually countered Polisario by building a heavily mined and patrolled 2,700-kilometre berm, one of the largest military infrastructure projects in the world. In its final form, the berm bisects Western Sahara from southern Morocco to the Atlantic coast near Mauritania.

By the late 1980s, the berm’s construction had created a situation of stalemate. Morocco could not eliminate Polisario forces unless it invaded northern Mauritania and western Algeria, while Polisario could do little more than harass Moroccan defensive positions along the berm.

Western Sahara’s legal status

The UN continues to list Western Sahara as a non-self-governing territory awaiting decolonisation – an international legal status laid out in the UN General Assembly’s 1960 Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. The Sahrawi people’s right to self-determination (including the option of independence) has been consistently reaffirmed by resolutions passed by the UN General Assembly and UN Security Council. Sahrawi political representation has been exercised through Polisario since its founding in 1973. The UN General Assembly recognises Polisario as the international representative of the Sahrawi people.

More controversial is the status of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), which Polisario declared as a state in 1976. Though SADR is a founding member of the African Union (AU) and has received bilateral recognition from dozens of governments, a significant number of those, including AU member states, have suspended or rescinded their recognition. The Moroccan government has likewise convinced a number of its African and Middle Eastern allies to open consulates in the occupied Western Sahara as an implicit acknowledgment of its claims to the territory. The US appears to be the only country in the world to have officially recognised Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara. However, the Biden administration is currently reviewing that decision – to the chagrin of Morocco, which is lobbying hard against a formal repeal, linking this to its normalisation of relations with Israel, which the Trump administration had orchestrated.

Besides being the last African territory awaiting decolonisation, what makes Western Sahara unique among the 17 remaining non-self-governing territories is the lack of a UN-recognised administering power willing to assume that role. This, in turn, has led to conflicting international determinations relating to Morocco’s status inside the areas of Western Sahara it controls.

The UN does not consider Morocco to be the legal administrator of the non-self-governing territory (a status which Morocco has not sought). Together with most of the international community, the UN rejects Moroccan claims of sovereignty over the territory. From an international law perspective, Morocco’s presence in Western Sahara is that of an occupying power beholden to international humanitarian law, including the Geneva Conventions. This is the conclusion of the UN General Assembly, the AU, and countries such as Sweden and Germany, which have described Morocco’s presence in Western Sahara as an occupation, as have international law experts such as Eyal Benvenisti and Marco Sassoli. This was also the opinion of the CJEU’s advocate general. This legal determination provides international protections for the occupied Sahrawi population and those displaced in Algeria. It also sets clear limits on Morocco’s actions, including prohibiting the transfer of its population into the occupied territory.

Morocco’s status as an occupying power is not unanimously recognised, however. Rabat has, of course, rejected this characterisation. The European Commission and the Council of the European Union have described Morocco as the “de facto administering power” of the non-self-governing territory – a legal concept that, as the CJEU’s advocate general has highlighted, does not exist in international law. The United Kingdom has, meanwhile, described the territory’s status and Morocco’s presence there as “undetermined”.

From referendum on independence to mutually agreed political solution

The impossibility of a military solution to the conflict gradually pushed Morocco and Polisario towards external mediation. By the late 1970s, the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) – the predecessor to the AU – was already mediating between Morocco and Polisario. The OAU succeeded in developing a settlement framework involving a ceasefire, a return of the refugees, and a final status referendum (on integration or independence). But Morocco withdrew from the OAU, scuppering negotiations, when SADR was seated as a full member state in 1984. Unable to move forward, the OAU referred the question of Western Sahara back to the UN.

By September 1988, UN secretary general Javier Pérez de Cuéllar informed the UN Security Council that he had obtained Moroccan and Polisario support for a settlement framework adapted from the OAU proposal. This framework would eventually crystallise into the 1991 Settlement Plan, which offered a UN-monitored ceasefire and transitional period that would allow for the return of Sahrawi refugees and a referendum, to be held within two years, with a choice between independent statehood for Western Sahara or formal integration into Morocco under Moroccan sovereignty.

This represented a hugely important – but widely unrecognised – concession by Polisario: it agreed to suspend its pursuit of unilateral independence pending the holding of a UN-backed referendum to determine the territory’s future status. In doing so, Polisario also accepted the option of integration into Morocco.

The UN Security Council created MINURSO in April 1991 to implement the plan. While the UN secretary general was able to declare a ceasefire in August, the other elements of the plan were delayed due to a lack of agreement between the parties relating to the organisation of the referendum. One of the most contentious issues, which would continually delay the referendum for several years, related to the technical criteria for identifying and registering Sahrawi voters.

During this time, Rabat used resettlement of Moroccans to Western Sahara as a demographic strategy to counter Sahrawi independence. Though accurate figures are hard to come by, one-half or more of Western Sahara’s population today – a total currently estimated by the UN as standing at 567,000 – could be non-indigenous Moroccan settlers. In pushing to enfranchise as many voters as possible for the proposed UN referendum, the Moroccan government hoped to swing the result towards integration. Weary of such efforts by Morocco, Polisario often obstructed the MINURSO voter identification commission’s work, which finally ground to a halt in 1995.

In 1997, James Baker – a former US secretary of state appointed by UN secretary general Kofi Annan as his personal envoy to Western Sahara – succeeded in resolving all of the outstanding technical issues impeding the implementation of the Settlement Plan, notably the voter identification process, in a set of accords known as the Houston Agreements. To date, these are the only agreements ever signed by both Morocco and Polisario. Within two years, MINURSO was able to finalise a provisional list of 86,386 voters for the referendum. The voter list was largely assumed to favour independence, as it was composed almost entirely of Sahrawis counted by Spain in 1974 and their direct descendants, who were predisposed towards independence. Rabat’s effort to include ‘Sahrawi’ voters favourable to Moroccan positions – that Spain had not counted in its original census – failed to bear fruit: less than half of Moroccan-sponsored candidates from occupied Western Sahara and less than 15 per cent of its candidates from Morocco proper were included in MINURSO’s provisional voter list.

As Western Sahara took a step closer to a referendum, the UN Security Council started to get cold feet. During the summer of 1999, Hassan II passed away, leaving his kingdom to a young and untested Mohammed VI. Driven by concerns over the stability of the Moroccan regime’s transition under the new monarch and the domestic political upheaval that the ‘loss’ of Western Sahara could provoke, Morocco’s main allies on the UN Security Council, France and the US, encouraged the new king to move away from the Houston Agreements.

In addition, the UN Security Council was spooked by the fallout from the UN-organised referendum in East Timor (occupied and annexed by Indonesia in 1975-76), which bore many similarities to the referendum that MINURSO aimed to hold in Western Sahara. When in 1999 the East Timorese rejected a UN-backed autonomy plan in favour of independence, violent reprisals by Indonesian-backed militias required the deployment of a robust UN peace-enforcement mission. Shortly afterwards, Annan warned that the Settlement Plan and Houston Agreements contained no provisions to enforce the outcome of the referendum. Annan also decried the fact – somewhat ironically, in hindsight – that a referendum was likely two years away given the number of Moroccan-sponsored persons (over 135,000) appealing their exclusion from MINURSO’s initial voter list.

With the UN Security Council considering the Settlement Plan to no longer provide for an “early, durable and agreed resolution,” it began calling on Morocco and Polisario to discuss “a mutually acceptable political solution to their dispute over Western Sahara.” This represented a reversal of the logic underpinning its past efforts. Before Hassan II’s passing, those inside the UN negotiations had assumed that the likely outcome of the referendum – independence – would induce credible concessions from Morocco to make a durable political solution possible. Instead, the UN Security Council was now calling on the parties to negotiate a political solution prior to the holding of any referendum. It framed this new approach as a more realistic way of achieving a lasting and timely solution given the prospect of having to delay MINURSO’s referendum until at least 2002 while Moroccan-sponsored voters’ appeals were being processed.

The new mantra of “a mutually acceptable political solution” gave both main parties more veto power over the peace process and formalised the need for Moroccan consent before Sahrawi self-determination could be fulfilled. By abandoning the Houston Agreements and the original referendum process prematurely, the UN Security Council thus deprived itself and Baker of a powerful mechanism – a likely vote for independence – to steer the parties into an agreement.

The Baker plans

With a new mandate in hand, Baker developed a draft framework agreement in 2001 (known as Baker I). This one-page proposal formally put Sahrawi autonomy (as opposed to full independence) on the table for the first time, though the degree of self-rule was limited and the options for the proposed final status referendum, as well as the voter list, were undefined. While the plan was eagerly accepted by Morocco, Polisario refused to even consider it, instead seeking to revive the Houston Agreements. Marking the anniversary of the Green March in November 2001, Mohammed VI announced that the Settlement Plan’s proposed referendum on Western Saharan independence was now “null” and “inapplicable.” Since then, Morocco’s formal position has been to reject any proposal – and increasingly, any process – that could conceivably lead to an independent Western Sahara.

Baker’s revised proposal, the 2003 peace plan for the self-determination of the people of Western Sahara (Baker II), offered Sahrawis a more enhanced interim autonomy under a locally elected Western Sahara Authority to be followed four years later by a referendum on whether to continue the autonomous arrangement, join with Morocco, or become independent. Unlike the original 1991 Settlement Plan, however, this referendum would allow Moroccan settlers who had arrived prior to 1999 to vote alongside native Sahrawis listed on MINURSO’s provisional voter list or otherwise included in a recent registration of the refugee camps’ inhabitants carried out by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees agency.

Despite the mixed electorate proposed, Polisario surprisingly endorsed Baker II (with Algerian encouragement), while Morocco strongly objected to the reinsertion of an independence option. That summer, the UN Security Council empowered Baker to work on securing an agreement on the proposal in order to implement it. Polisario had now made two historic concessions regarding Western Sahara’s right to self-determination: in 1991, when it agreed to include integration with Morocco as an option alongside independence; and in 2003, when it agreed to allow non-Sahrawis to vote in a referendum with autonomy as a third option. Though the ball was clearly in Rabat’s court, it refused to recognise Polisario’s compromise and proved increasingly reluctant to continue working with Baker.

The UN Security Council considered whether to grant a stronger mandate in April 2004, but it merely reaffirmed its willingness to implement a proposal “on the basis of agreement between the two parties.” Having already insisted that mutual agreement was an impossible standard in the absence of substantial compromise, Baker soon resigned in clear frustration with the UN Security Council, which dropped any mention of the Baker proposal in its next resolution.

A peace process adrift

For nearly 20 years, international engagement in Western Sahara had been based on developing and implementing a UN plan in consultation with the parties, one that would finally decolonise Western Sahara through a referendum on independence. Following Baker’s departure in 2004, the UN Security Council pivoted to an approach based on UN-facilitated dialogue to encourage the parties to develop a mutually agreed plan. In so doing, the UN Security Council further relinquished its control over the process by handing it over to Morocco and Polisario. The original mandate of MINURSO – to organise a self-determination referendum on independence – faded into the background as ceasefire monitoring and the increasingly fruitless search for “a negotiated political solution” took centre-stage.

Three successive personal envoys – Peter van Walsum (2005-2008), Christopher Ross (2009-2017), and Horst Köhler (2018-2019) – laboured unsuccessfully to facilitate constructive dialogue between the parties. The most significant development occurred early on, when Morocco and Polisario put forward competing proposals in 2007 to end the dispute. But, rather than help to define a potential zone of agreement between the sides, the plans highlighted just how far apart they had drifted.

Morocco’s autonomy initiative

Morocco’s autonomy initiative cherrypicked elements from Baker’s plans. It envisaged the establishment of a local regional administration – the Saharan Autonomous Region (SAR) – under Moroccan sovereignty. However, the powers that Morocco proposed to devolve to the territory were much narrower in scope than those proposed by Baker. Rabat argued that its plan represented the maximum parameters of any agreement with Polisario.

According to the autonomy plan, the SAR would have a degree of internal governance with its own executive and legislative bodies. It would have the powers to create its own laws and regulate domestic issues such as infrastructure and social policy. Residents of the SAR could elect their own representatives. However, all local laws would need to be consistent with the Moroccan constitution and would be subject to review by the Moroccan supreme court, while SAR’s head of government would be invested by the Moroccan king. In addition, Rabat would retain control over Western Sahara’s natural resources, foreign relations, currency, and external and internal security.

Since it first tabled the plan in 2007, Morocco has lobbied successfully to gain international endorsement; Washington and Paris early on described Morocco’s proposal as “serious and credible” and successfully pushed for similar language to be included in subsequent UN Security Council resolutions. Under Trump, the US took another step in Morocco’s direction by suggesting that its autonomy proposal should be “the only basis” for resolving the conflict; the US then co-hosted an international conference with Morocco in support of the plan.

Polisario’s post-referendum guarantees

In a direct counter to Rabat’s autonomy proposal, Polisario put forward a series of post-referendum guarantees. These offered Morocco a ten-year cooperation agreement to facilitate economic, social, and political interdependence should the referendum lead to Western Sahara’s statehood. It also offered the right to Sahrawi nationality for Moroccan settlers. The UN Security Council nominally welcomed Polisario’s proposal, while Morocco refused to acknowledge it. Whether or not Polisario remains committed to its 2007 offer or even elements of the 2003 Baker II plan is an open question, as the liberation movement’s public discourse has more recently tended to invoke its consent to the 1991 Settlement Plan rather than its subsequent concessions.

Understanding Morocco’s calculations

Morocco’s apparent high tolerance for the status quo suggests that the current reality is far more acceptable to it than the kinds of compromises called for in the 1997 Houston Agreements or the 2003 Baker II plan. Until now, Rabat has faced few challenges to its continued control over the territory and its exploitation of Sahrawi natural resources – which have become an important part of the general Moroccan economy and which subsidise its settlement activities. Companies owned by the ruling regime have also benefited. As the country’s former agriculture minister, Mohand Laenser, has admitted, ensuring that Western Sahara is included in external accords concluded by Morocco, such as fishery agreements with the EU, is as politically important as it is financially beneficial.

Moroccan claims to Western Sahara are a core part of the national ideology promoted by the ruling monarchy and are an important source of its domestic legitimacy. Over the course of the previous four decades, the idea that Western Sahara is a part of Morocco – the only part of “Greater Morocco” to be successfully recovered since independence – has become an unquestioned aspect of the country’s postcolonial national identity. For the Moroccan monarchy, the 1975 seizure and ongoing integration of Western Sahara – in the face of what it sees as fierce opposition from Sahrawi nationalists, Algeria, and the international community – has helped to secure and reaffirm its domestic hegemony.

Morocco has become ever more explicit in its rejection of Sahrawi independence. Under Hassan II, Morocco showed some openness to the possibility. However, with the benefit of hindsight, this seems to have been largely tactical, enabling Morocco to buy time to settle the territory and slow down international diplomacy at the OAU and later the UN. Under Mohammed VI, Morocco has explicitly ruled out independence since 2001.

Historically, France and the US have been the most important supporters of Morocco’s quest to control Western Sahara. During the cold war, both countries privately opposed Sahrawi statehood, fearing that it would become a proxy for Algeria and the Soviet Union. They also recognised the extent to which the domestic legitimacy of the Moroccan monarchy – and therefore the stability of Morocco – had become tied to its control of the territory. In exchange for their external support, Morocco has supported French and US security and political interests, from the cold war, through the “war on terror,” until the present day. For France, Morocco has added importance given its role as a key trade partner and linchpin in its wider network of postcolonial African states allied to its political, economic, and cultural interests. As a consequence of this, the French government has quietly but consistently advocated what it sees as the less strategically threatening outcome: autonomy for the territory under continued Moroccan control – as research in the French state archives reveals.[2]

Under its French and US umbrella, Morocco has had little incentive to compromise. Its attitude to the most recent UN envoys, Ross and Köhler, turned negative precisely when they began to suggest, albeit implicitly, that the autonomy proposal was an insufficient basis for resolving the conflict.[3] Since 2007, the diplomatic support that France and the US have given to its autonomy plan have convinced Morocco that Sahrawi independence was effectively off the table. Their stance has encouraged Morocco to approach UN-facilitated talks on the basis that autonomy represents the sole basis for discussion. As the king stated in 2015 while marking the fortieth anniversary of the Green March, this was “the most Morocco can offer.”

Following Trump’s recognition of Western Sahara as part of Morocco, Rabat believes that the international and regional environment is further swinging behind its claims. This gives it even less reason to make significant concessions.

At the same time, though, there are reasons to believe that Morocco has never been deeply invested in its own autonomy proposal, which itself drew on ideas proposed decades earlier by the US and France.[4] The proposal’s timing in 2007 was primarily motivated by a promise the George W Bush administration made to recognise Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara – which pressure from the State Department ultimately prevented. In the 14 years since, Morocco has yet to take any concrete steps towards implementing its vision. There is reason to believe that Rabat may be cautious about Western Saharan autonomy given the example this could set for Moroccan regions such as the Rif in northern Morocco, whose small but active ethno-nationalist movement has historically chafed at central state authority.

Polisario’s return to war

Last year closed with ominous developments. In November 2020, Polisario declared an end to the 1991 UN-brokered ceasefire and resumed armed attacks against Moroccan forces in Western Sahara and southern Morocco. This came after Moroccan armed forces crossed the armistice line on 13 November and entered the Guerguerat demilitarised UN buffer zone, which is inside de facto SADR territory. Rabat sought to disperse Sahrawi protesters blockading traffic on the only road connecting Western Sahara (and Morocco) to Mauritania. Morocco has since extended its berm through the UN buffer zone into Mauritanian territory.

The flare-up of violence in Guerguerat was a casus belli for Polisario. But the 173,600 refugees in Algeria, from which Polisario draws its armed forces, had already grown deeply frustrated by the lack of diplomatic progress and the impunity with which Morocco has been able to exploit the territory’s natural resources, repress Sahrawi rights activists, and prevent a referendum. Trump’s endorsement of Moroccan claims further fuelled national anger among the Sahrawi exiles in Algeria.[5]

Polisario’s return to armed struggle after a nearly three-decade hiatus reflects the uncertain future facing the Western Saharan nationalist movement. Its fortunes in both war (1975-1991) and peace (1991-2020) began with initial success but ended in stalemate. Sahrawi nationalism and the desire for independence have remained strong throughout, including in the areas occupied by Morocco – as evidenced by the eruption of two Sahrawi intifadas (civil uprisings) against Moroccan rule, in 1999 and 2005; the Gdaym Izik demonstrations in 2010; and recurring smaller-scale protests, despite the threat of detention by Moroccan security forces. Throughout this time, most Sahrawi nationalists have continued to view Polisario as their only source of political representation given the movement’s surprising lack of fragmentation after nearly five decades of struggle.

Publicly, Polisario frames its return to armed conflict as an effort to achieve independence. But, after six months of attacks, there is little indication that Polisario’s forces – the Sahrawi People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) – will be able to overcome the same strategic obstacles that blunted its military campaign in the 1980s. More privately, Sahrawi leaders appear to understand the limitations of a purely military approach and the need to use diplomatic means.[6] Polisario’s escalation therefore seems tactical – to respond to growing popular frustration, strengthen Sahrawi negotiating positions, and generate renewed international attention.

That said, Polisario officials have warned that continued inaction by the UN could further convince their constituents, particularly among the refugees in Algeria, that seeking a political solution is a dead-end strategy and that all efforts should instead focus on armed conflict.[7] To be sure, there are questions about how sustainable Polisario’s escalation is given its outmoded arsenal, the advanced age of its most experienced fighters, and its military dependency on Algeria to resupply its units, mainly with light weapons, artillery, rockets, and missiles. Morocco also brings formidable armed force to bear.

Spurred by a regional arms race with Algeria, Morocco has recently ranked among the world’s top 30 arms importers, with its main suppliers being the US, France, and the UK. Recent and pending Moroccan purchases of Turkish, Israeli, and American drones likewise represent a capacity Rabat did not have against Polisario in the 1980s. At the same time, recent SPLA attacks inside southern Morocco hint at a willingness to take the fight beyond the berm and deeper into Moroccan-controlled areas.

The EU’s ‘trade first’ policy

Despite its geographic proximity, the Western Sahara conflict has received little attention from the EU. The bloc has been absent from peace-making efforts, besides providing some €9m a year in humanitarian support to Sahrawi refugees in Tindouf. This lack of attention reflects the way in which the issue has been subsumed by the EU’s desire to develop and maintain close bilateral relations with Morocco.

The EU has preferred to look to the UN Security Council and key member states, in particular France and Spain, for its policy direction (or lack thereof).[8] Reflecting these countries’ positions, which have tended to emphasise a political compromise acceptable to Morocco, high representative Josep Borrell has summed up the EU’s position as supporting “a realistic, practicable and enduring political solution to the question, based on compromise.” In contrast, member states such as Sweden have emphasised international law, adding that such an outcome must also “provide for the self-determination of the people of Western Sahara, in line with international law”.

To the extent that the EU does have a policy, it largely comprises its trade and fisheries relations with the territory. EU trade with Western Sahara is limited, made up mostly of Western Saharan exports of fishery stocks, agricultural products, and phosphates, and European investment in green energy projects. Access to Western Sahara’s waters is, however, important to EU (particularly Spanish) fishermen.

The EU has touted the benefits of its arrangements for the local population, claiming these have boosted employment rates and socio-economic development. Such assertions are misleading given that trade and fishing related to Western Sahara have both occurred within the scope of the EU’s agreements with Morocco. From 2014 to 2018, Western Saharan waters provided 94 per cent of catches by the EU’s fishing fleet operating under Moroccan permits as part of the EU’s fishery agreement with Morocco. In 2019, the total value of Moroccan exports to the EU from Western Sahara was over €504m. In creating this situation, the EU failed to obtain the consent of the Sahrawi people via its international representative, Polisario.

The primary beneficiaries of these relationships with the EU have not been Sahrawis themselves, but Morocco’s own economy and its settler population. EU fishing activities support 10 per cent of the jobs in Morocco’s fishing sector, which is dominated by Moroccan operators and settlers. In exchange for Moroccan fishing permits, the EU and its fishing companies have provided Rabat with €40m in financial compensation a year. The Moroccan government has used this to subsidise infrastructure projects for the benefit of its settler population. Agriculture in Western Sahara is likewise dominated by Moroccan companies and settlers.

The European Commission has admitted that a key motivation for supporting EU trade with Western Sahara is to maintain close ties with Morocco. In a 2020 report, it noted that “the smooth functioning of the Agreement [on preferential trade tariffs] has also facilitated the resumption of a fruitful dialogue with Morocco, which is expected to lay the foundations for the development of closer relations with this important neighbour, to the mutual benefit of the EU and Morocco.”

This “benefit” relates not just to trade and investment with Morocco, but also its role as an important partner in counter-terrorism cooperation and migration control. Stopping the flow of illegal migrants – most of whom are Moroccans – is particularly important to Spain given the position of the Canary Islands and its two North African towns of Ceuta and Melilla as the main destinations for migrants on their way to Europe. This includes weekly deportation flights from Gran Canaria to the Western Sahara town of Laayoune – possibly as part of an effort by Morocco to force European recognition of its claims to the territory.

Morocco has not been shy in leveraging European interests. This has led to repeated diplomatic flare-ups. In 2015 the Moroccan government blocked the opening of the country’s first IKEA store over rumours that Sweden was considering recognising SADR (which the Swedish government denied). The following year, Morocco suspended all contacts with the EU following a ruling by the CJEU to annul the extension of agricultural and fishery agreements with Morocco to Western Sahara. In response, EU officials worked with their Moroccan counterparts to oppose the ruling.[9]

In addition, Morocco appears to be exploiting the flow of migrants – relaxing controls to signal its political displeasure with Europe and force European policy changes. As its agriculture minister, Aziz Akhannouch, has warned, any obstacles to the inclusion of agriculture and fishing exports to Europe “could renew the ‘migration flows’ that Rabat has ‘managed and maintained’ with ‘sustained effort.’” As well as the recent arrivals into Ceuta allowed as a message to Madrid, in March 2021 Rabat suddenly cut all relations with Berlin and withdrew its ambassador. While the motive remains unclear, Moroccan media has attributed the move to Germany’s “unfriendly attitudes”, including an effort by Berlin in December 2020 to bring the issues of Trump’s proclamation and renewed fighting in Western Sahara to the attention of the UN Security Council. The brewing diplomatic crises with Spain and Germany demonstrate that Western Sahara will continue to disrupt European bilateral relations with Morocco.

The EU’s impact on the peace process

The EU’s trade and fishing practices, and distortion of international law, have detrimentally impacted on the prospects for resolving the Western Sahara conflict. They have amplified the negative power dynamics that led to the failure of past peace-making attempts. Firstly, the EU has weakened Polisario’s negotiation position in the UN peace process by undermining the distinct and separate territorial status of Western Sahara, and ignoring the need to obtain its consent to the exploitation of Sahrawi natural resources. Secondly, it has helped strengthen Morocco’s bargaining positions at the UN by lending European political, economic, and financial support to Morocco’s territorial claims. According to two sources familiar with the exchange, Köhler, while he was in post as UN envoy, made this point during a briefing with the European Parliament’s foreign affairs and human rights committees in May 2018. He warned that the EU’s trade policy was hurting his efforts in pursuit of peace.

Through their actions, the European Commission and Council of the European Union have wrongly recognised the internationally unlawful administrative regime that Morocco has extended to Western Sahara, giving a false veneer of legitimacy to its presence in the territory. This comes despite their formal non-recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over the territory and obligation under international law to ensure that the EU does not assist in maintaining the illegal situation that Morocco has created. According to the UN’s International Law Commission, this obligation applies to acts that could imply recognition of any unlawful “acquisition of sovereignty over territory through the denial of the right of self-determination of peoples.”

A brewing summer crisis with Morocco?

Since 2012, Polisario has been successfully challenging EU practices at the CJEU. Successive rulings have developed (and sometimes corrected) EU positions. In December 2016, the CJEU ruled that Western Sahara fell outside the scope of Morocco’s Association Agreement, thereby reaffirming the territory’s separate and distinct status from Morocco. The court had previously admonished the European Commission for not having secured the consent of the Sahrawi people. It also accepted Polisario as their international representative.

The impact of these rulings is that the EU has begun to more strictly implement its requirement of differentiating between Morocco and Western Sahara, based on its obligation under EU and international law to ensure effective non-recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over the territory and preserve its separate and distinct legal status. This is in line with the legal rationale underpinning EU trade practices and non-recognition policies in relation to other situations of foreign occupation and annexation, such as the Israeli-occupied Palestinian territory and Syrian Golan Heights, Turkish-occupied northern Cyprus, and Russian-occupied Crimea. In each of these situations, the EU has a legal duty of ‘non-recognition’ – to ensure that its bilateral relations do not recognise the occupying power’s sovereignty over the occupied territory. It must also ensure that its actions do not facilitate internationally unlawful actions, such as annexation, settlement activities, and international human rights abuses. To do this, the EU must ensure the full and effective exclusion of the occupied territory from the scope of its agreements with the occupying power.

There are early signs of the CJEU’s case law being translated into new proposals. For example, in November 2020, the European Commission proposed to extend the EU’s Interbus agreement (regulating coach traffic) to Morocco, but excluded Western Sahara from its scope of application. Yet, the European Commission is still searching for a legal basis to include Western Sahara within its trade and fishery agreements with Morocco. It now claims to have obtained the consent of the local population for this. But it has done so not by seeking approval from Polisario – the international representative of the Sahrawi people – but rather by gaining the approval of local bodies established by Morocco under its internationally unlawful administrative regime.

The latest effort by the European Commission and Council of the European Union to include Western Sahara within trade and fishery agreements with Morocco is likely to be rejected by the CJEU this summer – which would once again remove any basis for such arrangements. A ruling in favour of Polisario would have economic consequences. EU fishermen would no longer be allowed to operate within Western Sahara’s waters under Moroccan permits, while Moroccan exports originating in the territory would be excluded from preferential EU tariffs. Based on past precedent, such a ruling would almost inevitably trigger a Moroccan display of anger against the EU, and encourage Polisario to launch further legal challenges. The court’s decision may also influence the outcome of a separate civil society challenge lodged in the UK against the inclusion of Western Sahara within the country’s new post-Brexit association agreement with Morocco.

The CJEU ruling will have implications for the peace process. A win could renew Polisario’s appetite for peace talks given what it would see as its strengthened negotiating position, potentially hardening its resolve to seek outright independence. A loss would further weaken Polisario, convincing it of the need to escalate its armed conflict against Morocco as the best and only means of advancing Sahrawi independence.

Despite the high-stakes ruling, there has been little contingency planning in European capitals beyond the intention to once again appeal the CJEU’s decision.[10] This will do little more than delay implementation of the court’s ruling, and ensuing crisis, by a few months.

The state of play today

The UN Security Council has been unable or unwilling to provide any meaningful response to slow the unravelling of the Western Sahara peace process. In the absence of any realistic horizon for reaching a peace agreement, annual UN Security Council resolutions speak to the prioritisation of the parties’ commitment to a ceasefire and dialogue – even if there has been little prospect of a breakthrough and no substantive face-to-face talks since the Houston Agreements. Following Polisario’s resumption of armed attacks, the UN Security Council now has neither a process nor a ceasefire. And the veto power exercised by Morocco and Polisario over any prospective candidate means the secretary general has been unable to find a new envoy since Köhler’s surprise resignation in May 2019. The two-year absence of this way of engaging the parties has exacerbated underlying negative dynamics, creating real long-term consequences for Europe.

Some European officials interviewed for this paper argue that the conflict needs a diplomatic time-out. But such a response risks further worsening these dynamics. Continued neglect will convince the Western Sahara national liberation movement that it has been effectively abandoned by the UN.[11] Polisario is already expanding the scope of its military activities, raising the possibility that Rabat will step up its military response. A recent reported Moroccan air strike against a senior Sahrawi security official may be a sign of things to come.

In a worst-case scenario, spiralling clashes between Morocco and the SPLA could spill over into neighbouring countries and contribute to the further destabilisation of the Sahara-Sahel region. In today’s regional environment, it is not difficult to imagine a wider, more intense conflict drawing in Islamist groups currently fighting in the Sahel and spurring external military intervention, including by Algeria. Even a moderate increase in local insecurity and conflict would further heighten tensions between Morocco and Algeria. A recent dispute over date farms in a Moroccan-Algerian border region shows how small tensions can easily escalate.

The European interest

Needless to say, escalating conflict in Western Sahara, especially if a Libya- or Mali-like scenario begins to play out, would negatively impact on European interests and could destabilise Algeria and Morocco – two key partners for the EU. Besides having to respond to increased migration flows, the EU and its member states could face the unappealing prospect of having to deploy additional resources – including potentially military forces – to pursue their regional counter-terrorism and stabilisation goals, as they have had to do, for example, in the Sahel.

By contrast, there is an equally possible, yet considerably more optimistic, outcome that has the potential to benefit both Sahrawis and Moroccans as well as the EU and broader region. Under a peace agreement, Western Sahara could serve as a catalyst for regional economic development and stabilisation. A peaceful and democratic Western Sahara that maintains close relations with Morocco, Algeria, and the EU would also be an important partner that can help advance European interests, including in the fight against terrorism, stabilising the Sahel region, and helping manage migration flows. A political and economic partnership between the EU and Western Sahara would provide other direct benefits to the EU, including a sound legal basis for fishing in Western Sahara’s waters.

An additional benefit would be the detente that a negotiated agreement would encourage between Morocco and Algeria, whose land borders have been closed since 1994. Such a diplomatic thaw would help tackle cross-border smuggling (which has been an added source of tensions in recent decades), while also boosting inter-regional trade and the free circulation of people between Western Sahara, Algeria, Morocco, and Mauritania. This could finally unlock the promise of the Arab Maghreb Union regional trade bloc, a stalled economic integration process that remains hamstrung by regional differences, particularly over Western Sahara. This project has been championed by the EU and, should it be fulfilled, would provide significant benefits for Europe, expanding trade with the continent and helping to stabilise its southern neighbourhood.

Finding a third way

If they are given the opportunity, there is little doubt that Sahrawis would opt for full independence, as most colonised peoples have done when allowed to choose. Polisario must, however, reckon with the current power asymmetry, in which Morocco has no intention of allowing such an outcome. It must also contend with the lack of international willingness to push Sahrawi independence through in the face of Moroccan objections. While European officials interviewed for this paper expressed different views regarding the acceptability of Morocco’s autonomy initiative, none considered Sahrawi independence to be either realistic or desirable.[12]

At the same time, Morocco and its foreign backers must recognise that forcing Sahrawis and their territory to integrate into Morocco will not lead to a sustainable resolution given the highly centralised and authoritarian nature of the Moroccan regime, and the strong opposition that such a move would elicit from Sahrawis inside and outside of the occupied territory. Moreover, though life in the Sahrawi refugee camps is not easy, few if any would willingly return to Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara, autonomous or not.[13]

For over two decades, the UN Security Council has explicitly called on Morocco and Polisario to reach a political solution that respects UN norms of decolonising non-self-governing territories such as Western Sahara. Implicitly, this mandate assumes that a solution to the Western Sahara dispute will be found somewhere between the options of independent statehood or integration into Morocco – the two options offered by the 1991 Settlement Plan. While this search for an alternative – a ‘third way’ – could take different forms, the peace process has been dominated by the idea of autonomy. This has proved ill-conceived.

The false promise of autonomy

Autonomy can exist along a spectrum of integrationist approaches including forms of federalism and devolution. Though Morocco’s 2007 autonomy proposal has frequently been described as a realistic compromise, notably by France and the US, the most durable autonomy models have occurred in highly democratic states. Yet even these arrangements can give rise to deep political contestation between local and central governments, as Catalonia’s relationship with Spain demonstrates.

Autonomy arrangements have a poor track record of permanently resolving ethnic conflicts in postcolonial and developing regions. This year’s conflict between the Ethiopian central government and the regional government of Tigray, and the implosion in the 1990s of the federal republic of Yugoslavia into a series of ethnic conflicts, are testament to this. Beijing’s gradual reassertion of direct control over Hong Kong – overriding its international commitment to “one country, two systems” – is also a stark reminder of how easily reversible autonomy arrangements can be in authoritarian systems.

The UN’s plan for decolonising Eritrea, from the 1950s, bears parallels to that of Western Sahara and offers another important warning. In this case, the UN decided to forgo holding a referendum and instead forged a political compromise creating an autonomous Eritrea federated under Ethiopian sovereignty. The arrangement stoked ethnic tensions and was gradually undermined by Addis Ababa’s creeping central state authority, triggering a 30-year war. This conflict was only ended by a UN-supervised referendum that granted Eritrean independence in 1993.

Morocco’s autonomy plan for Western Sahara risks similar outcomes given its lack of robust safeguards to ensure respect for Sahrawi rights and self-governance. This is a critical issue since the plan would formally integrate Sahrawis into an autocratic system that has a proven track record of suppressing their nationalism, human rights, and political agency. The plan also lacks a third-party mechanism that would resolve disputes over the plan’s implementation and mitigate the prospect of either side seeking recourse through force of arms.

Another fundamental problem with the autonomy model is that it runs contrary to Western Sahara’s international legal status as an independent territory that is separate from Morocco. While the Moroccan government and some foreign diplomats present the autonomy initiative as a middle ground between integration and independence, it is in fact merely a kind of integration, not an alternative to it, even if it devolves some powers to local government. This is problematic since the Western Sahara conflict is not an “internal” question that can be solved through autonomy, as claimed by Morocco. The 1975 ICJ opinion determined that the people of Western Sahara already constituted the territory’s sovereign authority when it came under Spanish rule. Fulfilling their right to self-determination is a question of whether or not the Sahrawi people would choose to delegate that sovereignty (either in full or in part) to another state.

While autonomy or any other approach based on integration may not be the correct basis for resolving the conflict, this does not mean that the UN Security Council should stop searching for middle ground. But any proposal must conform to Western Sahara’s internationally recognised status as a territorial unit that is separate and distinct from Morocco, with its own sovereign, the Sahrawi people, officially represented by Polisario. To this end, the UN Security Council, together with the parties themselves, should explore the lesser-known concept of free association.

Free association

Free association is grounded in the UN General Assembly’s resolution 1541 from 1960, which stipulates that the people of a non-self-governing territory can achieve self-determination through independence, integration, or free association. One of the judges who issued the 1975 ICJ ruling on Morocco’s claim to Western Sahara, Nagendra Singh, also cited free association as one means of decolonising the territory.

Though less common as a means of decolonisation for non-self-governing territories, free association is not unheard of in practice. Present-day examples include Palau, Micronesia, and the Marshall Islands, which entered into free associations with the US. The Cook Islands and Niue, which are self-governing states in free association with New Zealand, also provide useful case studies. While the Cook Islands enjoy self-rule, including legislative autonomy, New Zealand retains primary responsibility for external affairs and defence. In each of the above cases, the UN General Assembly approved their free association agreement and removed the territory from the UN’s list of non-self-governing territories.

Despite the concept of free association having clear relevance to Western Sahara, it has never been seriously discussed by international negotiators or the parties themselves. Yet it can provide a useful framework for fulfilling Sahrawi self-determination and reaching a final peace agreement with Morocco. As existing practices show, there is a degree of variance in how free association can be applied. This provides some latitude in devising an arrangement that can best respond to the unique challenges that exist in Western Sahara, drawing on ideas previously put forward by the UN and the parties themselves.

Similarly to autonomy, free association would provide for a power-sharing arrangement over the Western Sahara territory. However, this would take as a starting point the Sahrawi people’s inherent sovereignty over Western Sahara and provide greater protections for their rights. Under this arrangement, the Sahrawis (through Polisario) would delegate some aspects of their sovereignty to Morocco and a newly created state of Western Sahara. This should be based on the following principles.

Delegated authority

Polisario would (on behalf of the Sahrawi people) delegate sovereign authority over the Western Sahara territory to Morocco and the newly created state of Western Sahara. Western Sahara would be the ‘continuator state’ to SADR – inheriting its legal personality, including rights and responsibilities under existing international treaties to which it is a party.

Free association with Morocco would not require Sahrawis to renounce their right to independence. Similarly to the Cook Islands’ people, Polisario could instead declare that it has decided to exercise the Sahrawi people’s right of self-determination within a free association with Morocco, for now forgoing their quest for a fully independent state.

Western Sahara would have its own democratic system of self-governance, with executive, legislative, and judicial institutions independent from Morocco. Members of the legislative and executive would be elected by the citizens of Western Sahara. Western Sahara would have full control over the territory’s internal policies, such as taxation and use of resources. It would also have its own police force with primary responsibility for the territory’s internal security.

Morocco would assume primary responsibility for Western Sahara’s external affairs and defence. All decisions and actions by Morocco pertaining to Western Sahara would need to be taken with the consent of the Western Sahara government. As part of this, Morocco could be entrusted with representing Western Sahara in international bodies such as the UN. Although the status of Western Sahara’s membership of the AU (as the continuator state to SADR) would need to be addressed in consultations with the parties, one option could be for it to become politically ‘dormant’ – with Polisario committing to abstain in proceedings or votes for the duration of the free association agreement.

Popular consent

Any future arrangement with Morocco must reflect the consent of the Sahrawi people through an informed and democratic process. As Singh noted, this is “the very sine qua non of all decolonization.” A free association agreement would therefore need to be accepted by the people of Western Sahara – the Sahrawis – in a referendum. While this would require MINURSO to update and finalise the voter registry for indigenous Sahrawis, the criteria for doing so have already been established through the Houston Agreements.

Moroccan settlers resident in the territory could also be given the right to vote in a referendum, although precise eligibility criteria will have to be hammered out with the parties. This should come with guarantees and protections for settlers within the new state of Western Sahara, including a pathway to citizenship. This is an obvious concession to Morocco, but there is also reason to believe that many Moroccan settlers – whose primary motivation is economics rather than ideology – could be swayed by the concept of free association and its promise of greater rights at the local level.[14]

To be valid, any proposal would need to be approved by a majority of the electorate. As an added guarantee that a future referendum truly reflects Sahrawi will (and to avoid Morocco using its settler population to force through an outcome against Sahrawi opposition), a free association proposal would need to be backed by a majority of Sahrawi voters (known as a ‘double lock’).

Should the proposal fail to secure the required support, the UN could resubmit it to a second referendum after another round of consultations to amend the agreement in such a way as to address the concerns that resulted in its initial rejection.

Polisario and Morocco should have no veto power over the development of the UN plan by the secretary general’s personal envoy, nor over the referendum itself. Instead, they should leave it to the voters and agree to respect the result. Including both native Sahrawis and settlers in the referendum could, however, provide them with political cover to make what each side would consider difficult compromises and help avoid the sort of post-referendum violence seen in East Timor. To be successful, such a process will need strong political backing from the UN Security Council.

International oversight

The success of any free association arrangement will depend on the strength of international guarantees and supervisory mechanisms. Any disputes arising from the interpretation or application of the agreement should first be resolved by consultations through a joint committee. If unsuccessful after three months, either party could bring the matter to an independent third-party arbitration tribunal, under the Permanent Court of Arbitration, for instance. The tribunal’s rulings would be binding on the parties. It would have the power to impose financial penalties and refer more complex issues to other competent courts, such as the ICJ. But the UN Security Council and guarantor states would need to provide the relevant court with the political muscle to enforce its decision. In extremis, the court could grant Polisario and Morocco the right to dissolve the agreement in the case that one party seriously and irreparably breaches the terms of their commitments. Should Morocco be at fault, Western Sahara would be guaranteed UN Security Council support for full independence and UN membership.

In addition, free association could be strengthened by conditioning Morocco’s ratification of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the AU’s African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and its related protocol establishing the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights. As the continuator state to SADR, Western Sahara would be bound by SADR’s previous ratification of the African Charter and Protocol. With backing from the UN Security Council, Western Sahara could also request membership of the ICC.

Back to the future: The need for European leadership

Though there are plenty of reasons to be pessimistic about the prospects for a negotiated agreement that finally fulfils Sahrawi self-determination, there are also reasons to be optimistic. A timely, durable, and just resolution to the Western Sahara conflict is possible. For this to happen, international stakeholders must learn the right lessons from past failures.

By virtue of their geographic proximity to Western Sahara, trade ties, close partnership with Morocco, and influence on the UN Security Council, the EU and its member states have an important leadership role to play. This will likely require them to improve their own institutional capacities, starting with the creation of a dedicated Western Sahara desk in the European External Action Service. The EU could also appoint a special representative to spearhead its diplomatic efforts. It should consider the following approaches.

De-escalate

With ongoing armed operations by Polisario and increasing indications of a more forceful Moroccan response, the EU must provide its political backing for UN-led efforts to de-escalate tensions as an urgent first step. As part of this, it should increase its support for the appointment of a suitable personal envoy by the UN secretary general. It should also call on Polisario to suspend all armed activities in exchange for Morocco withdrawing its forces to positions held prior to 13 November 2020 – the date of its incursion into the Guerguerat buffer zone. This should include Morocco’s withdrawal from its newly created berm in the UN buffer zone. To be sustainable, these de-escalation measures must be paired with the resumption of a credible peace process.

Empower the UN

The UN must redouble its efforts to appoint a new envoy who has extensive experience with international negotiations and peace-making. A reputation as a tough but principled negotiator is a prerequisite. While gaining the consent of the parties is obviously preferable, the UN Security Council should remove the veto power they currently enjoy over the selection process. That said, finding a strong envoy is not enough. UN Security Council members and European governments must also give the personal envoy their full support, particularly when difficult decisions need to be made.

Instead of merely facilitating dialogue, the next envoy must have the political strength to drive forward a UN-developed plan to achieve Sahrawi self-determination. The UN envoy should use initial consultations with the parties to begin developing a final status agreement based on free association. Subsequent consultations could refine the proposal and maximise each side’s buy-in.

The envoy must have the power and discretion to put a future free association proposal to a confirmatory referendum. To do this, the UN Security Council will also need to put its political weight behind a strengthened MINURSO to enable it to fulfil its mission and organise the long-delayed referendum. The mission should also receive a mandate to report on human rights violations – like every other modern UN peace-keeping mission.

Securing a post-referendum peace agreement will require a robust UN assistance and monitoring mission during a transitional phase of at least five years, beginning after a referendum in favour of a free association treaty. This mission would succeed MINURSO (whose mandate will have been fulfilled in such a case) and be tasked with monitoring the compliance of both sides with their treaty commitments and respect for international human rights norms.

A strong third-party force will be important in reassuring Sahrawi refugees that they will be able to return safely to their homeland while providing security guarantees to the settler population as Morocco transfers governance to the Western Sahara government and draws down its security presence. The EU could provide additional technical capacities through a new Common Security and Defence Policy mission. As a final act, the UN envoy would be charged with sending a report to the UN General Assembly recommending Western Sahara’s removal from the UN’s list of non-self-governing territories.

Incentivise a deal

There can be no resolution to the conflict without the EU investing political and financial capital. This must include a European willingness to exert sufficient leverage on Morocco to move towards a middle-ground solution. Of course, this should not give Polisario a free pass concerning its own counterproductive or obstructionist actions and allow it to return to armed violence.

But, as things stand, it is Rabat that is most unlikely to willingly endorse the concept of free association; just as it is unlikely to agree to anything that falls short of its autonomy proposal. This reflects Morocco’s problematic pattern of obstructionism to date, which has been at the heart of the peace process’s failure. By virtue of its status as the occupying power, the overwhelming control it exerts on the ground, and its obligations under previous UN resolutions and international law, it is Rabat that will have to move the most to make a future negotiated outcome possible.

As a start, France (along with other EU members) should remove its diplomatic protection for Morocco at the UN Security Council. In addition, it should abandon its current support for Morocco’s autonomy proposal in favour of free association. As the penholder for the Western Sahara file in the UN Security Council, the US should do likewise. Alongside this, the Biden administration should freeze implementation of Trump’s proclamation to avoid giving it legal or policy effect. It could also threaten a formal repeal should Morocco continue to obstruct Sahrawi self-determination. Such gestures would send a powerful signal and indicate serious international intent to bring the conflict to a swift and just end.

There should also be positive incentives. Within the context of a final agreement, the EU should offer Morocco and Western Sahara a significant incentive package that would combine financial support with closer political and economic relations with the EU. The package should support the development of the institutions and infrastructure of the Western Sahara state during the transitional phase and position it as a key European partner and conduit for regional economic integration. The EU could also propose an upgrade of relations with Morocco, giving it a status comparable to what members of the European Economic Area enjoy – including full participation in EU programmes and agencies, an enhanced trade deal, and visa free-travel. As a privileged southern partner, Morocco could access EU funding for large-scale infrastructure integration with Europe. In exchange, the EU would benefit from an improved gateway into sub-Saharan Africa, drawing on Morocco’s own economic ambitions for the region.

Harden the EU’s differentiation policy

The EU and its member states should more effectively leverage their economic relations with Morocco, ensuring that these comply with the EU’s guidelines on promoting compliance with international humanitarian law. This summer’s CJEU ruling will force Western Sahara onto Europe’s policy radar. Given the importance that Morocco attaches to Western Sahara’s inclusion in its trade relations, the EU should understand the political benefits of the invalidation of these arrangements. Rather than appealing a future CJEU decision and closing ranks with Morocco as it has done in the past, the response of the Council of the European Union and EU member states should be to completely exclude Western Sahara from the full scope of their relations with Morocco. In addition, the European Commission should publish clear guidelines prohibiting the use of EU funds for Moroccan entities and activities in the territory of Western Sahara. This can provide a ‘best practice’ guide for other economic partners of Morocco – including the US, and Russia whose fleet fishes extensively in Western Sahara’s waters under Moroccan permits – and multilateral organisations of which Morocco is a member.

Either way, Morocco’s insistence on including Western Sahara in the scope of its bilateral agreements will increasingly conflict with EU legal positions enforced by the CJEU. While the EU’s differentiation policy may not be the immediate game-changer that Polisario hopes for, it represents one of the few direct challenges to Morocco’s continued hold over the territory and business interests.

Rabat may reason that it has little to lose from rejecting the EU’s Interbus agreement because of its exclusion of the territory. But the likely expansion of EU differentiation requirements to other areas of its bilateral relations could create real political dilemmas given the risk that Morocco could lose access to existing agreements, such as those relating to scientific and technological cooperation, aviation, taxation, and investment. This could create another incentive for it to accept a face-saving agreement such as free association that could allow for the continued smooth development of ties with Europe and potentially preserve Moroccan business interests in the territory within a future EU-Western Sahara trade deal. A more rigid enforcement of EU law also offers a means of re-establishing a more balanced EU relationship with Morocco.

In recent years, relations have tilted heavily in Rabat’s favour, entrenching a sense of European dependency and deference.[15] This has been to the detriment of the EU’s ability to secure its longer-term strategic interests when these conflict with Moroccan preferences. Morocco’s response to this summer’s CJEU ruling (should it side with Polisario as expected), and a European pivot away from autonomy towards free association for Western Sahara, will provoke an aggressive Moroccan pushback, including the potential disruption of bilateral relations. This will undoubtedly pose short-term challenges for the EU, particularly with regard to migration flows. The EU must do more to defend against Moroccan “blackmail” – as Spain’s defence minister Margarita Robles has described. An effective answer to this, which can minimise Morocco’s ability to leverage this issue, will require greater EU (particularly French) support for Spain’s effort to counter this alongside a comprehensive reform of EU migration policy. A future Western Saharan state could be an important partner in this regard. Europeans must also show more willingness to leverage their political and economic ties to defend their interests and credibility. Ultimately, as the stronger party, the EU stands to lose far less from any disruption of relations over the longer term in comparison to the value that Morocco derives from its relations with Europe.

Conclusion

A diplomatic solution to the Western Sahara conflict is possible – one that can preserve each side’s core interests and fulfil the Sahrawi people’s right to self-determination in a manner consistent with international law and political realism. But this will still require both sides to make concessions to get what they want.

For Polisario, this means delegating some authority to Morocco in exchange for an end to Moroccan occupation and achieving Sahrawi self-governance. For Morocco, this means accepting Western Sahara as a separate self-governing territory in exchange for an internationally recognised stake in its future. These trade-offs would allow Sahrawis and Moroccans to benefit from increased economic prosperity, regional integration, and closer ties to the EU.

None of this can happen in an international vacuum. The UN Security Council, the EU, and their respective members all have the capacity to shape this future by deploying the right combination of incentives and disincentives. Few European capitals consider Western Sahara to be a pressing foreign policy issue. Yet, at a moment in which the conflict may get suddenly worse with potential wider implications for north-west Africa and Europe, the time is ripe for renewed international attention.

About the authors

Hugh Lovatt is a policy fellow with the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations. Since joining ECFR, he has advised European governments on the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process. Lovatt co-led a 2016 track II initiative to draft an updated set of final status parameters for ending the conflict, and pioneered the concept of ‘EU differentiation’, which was enshrined in UN Security Council Resolution 2334.

Jacob Mundy is a professor at Colgate University and is the co-author (with Stephen Zunes) of Western Sahara: War, Nationalism, and Conflict Irresolution, a second edition of which will be published this year by Syracuse University Press. He has conducted field and archival work in Algeria, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia, including the original research for the International Crisis Group’s reports on Western Sahara in 2005. He was a Fulbright Scholar at the Université de Tunis in 2018–2019.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the numerous officials, both retired and serving, and experts who generously provided their time and insight. We are particularly indebted to those kind enough to have reviewed working drafts and offered such thoughtful responses to our analysis and ideas. As ever, any mistakes or omissions are purely our own. We would also like to thank ECFR’s publications team for their constant support and diligence.

[1] Jacob Mundy. “Moroccan Settlers in Western Sahara: Colonists or Fifth Column.” Arab world geographer 15, no. 2, 2012, pp 95–216.

[2] Davide Contini, “La Decolonizzazione Mancata: Il Caso Saharawi”, Bologna University (unpublished), 2016, pp 60-61.

[3] Interviews with former UN officials, February-May 2021, via Zoom. See also: Stephen Zunes and Jacob Mundy, Western Sahara: War, Nationalism and Conflict Irresolution, Syracuse, Second Edition, 2021.

[4] Davide Contini, “La Decolonizzazione Mancata: Il Caso Saharawi”, Bologna University (unpublished), 2016, pp 60-61.

[5] Interviews with Sahrawi activist and Polisario official, February-April 2021, via Zoom.

[6] Interviews with Sahrawi activist and Polisario official, February-April 2021, via Zoom.