European Solidarity Tracker: The solidarity that always was there

ECFR’s new tracker reveals the breadth and depth of solidarity expressed throughout Europe during the coronavirus crisis – with findings that will surprise critics.

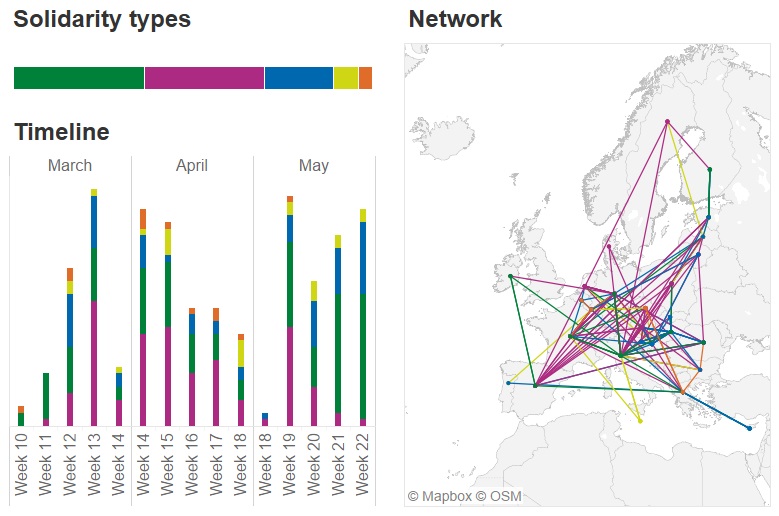

Solidarity has come in different forms as Europeans confront the coronavirus pandemic – this is one of the key insights from ECFR’s European Solidarity Tracker. This new interactive tool allows everybody to visualise the ways in which Europeans supported each other during this period. It shares instances from across the continent of pan-European solidarity among the member states of the European Union, the EU institutions, and European civil society. The tracker breaks “solidarity” down into its different manifestations. In doing so, it sheds light on which actors pursued which actions at which moments as the coronavirus spread throughout Europe.

27 March 2020 was Italy’s darkest day in the coronavirus crisis – 919 Italians died of covid-19. Most of the victims likely contracted the virus about two weeks before, around the same time as Italy’s ambassador to the EU, Maurizio Massari, publicly expressed his frustration at the cacophony of export restrictions and border closures that had met the Italian government’s earlier calls for European solidarity amid the explosion of infections in the northern regions of Lombardy and Veneto. “It’s time now for the EU to go beyond engagement and consultations, with emergency actions that are quick, concrete and effective,” he pleaded on 10 March.

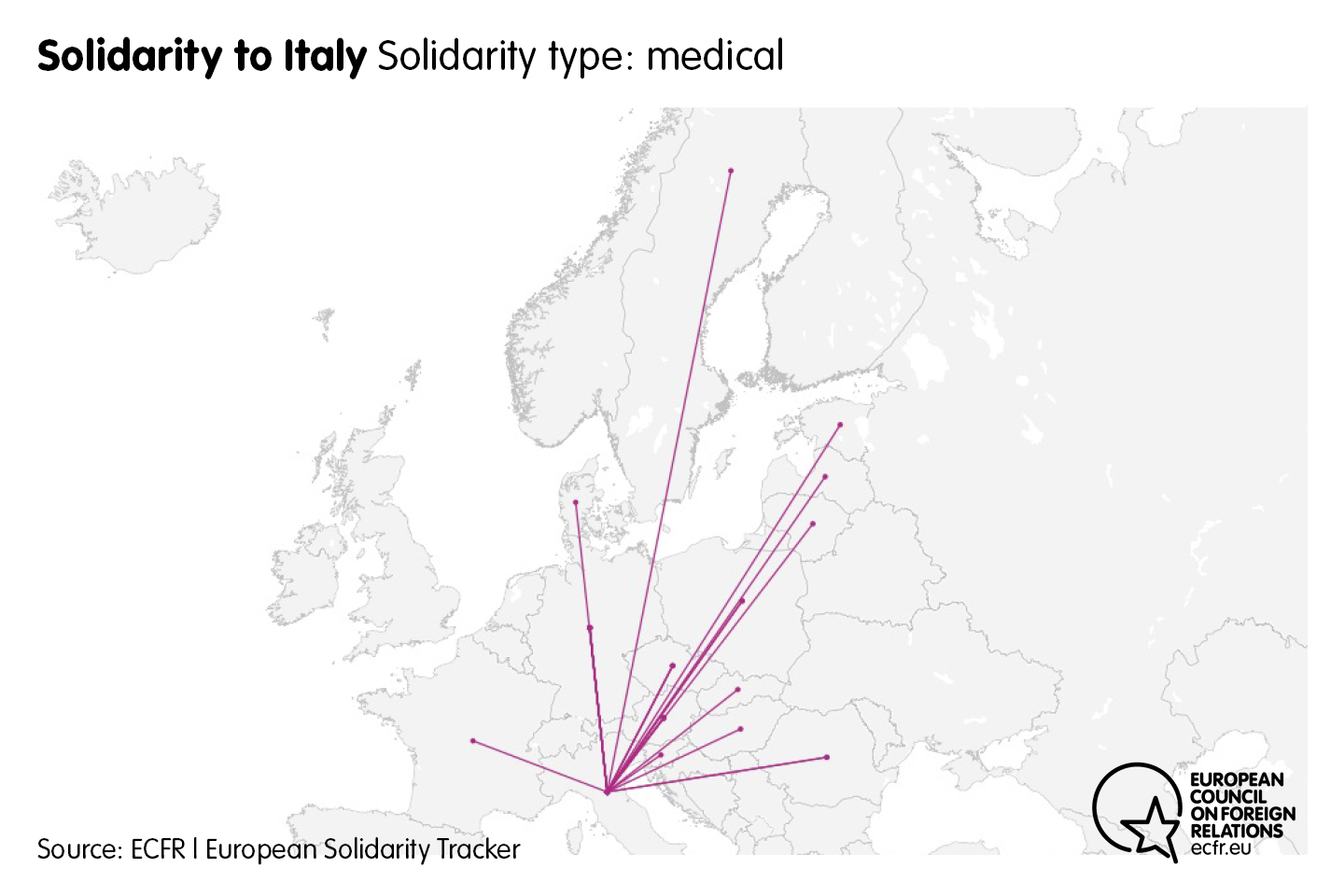

Massari’s call was not without effect. Soon, emergency medical supplies began to arrive and the number of daily new infections began to decline. As ECFR’s tracker shows, by the end of May, Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Sweden had sent hundreds of thousands of protective masks, teams of medical professionals, and other forms of assistance to Italy.

In these early weeks of Europe’s exposure to the virus, “solidarity” was all about health in its most direct sense. As medical professionals across Europe learned more about the pathogen, policymakers were able to apply more effective and targeted measures to contain its spread. At the same time, the economic effects of the health crisis, lockdowns, and travel restrictions on Europe’s economies became painfully obvious. Four months into the crisis, European leaders now invoke solidarity in reference to the economic crisis and in calling for a common recovery plan: the European Commission, France and Germany, and the “frugal four” (Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden) all frame their recovery proposals in terms of solidarity.

The European Solidarity Tracker demonstrates that reports of the EU’s irrelevance have been greatly exaggerated. True, the EU has no real mandate on public health policy; it could not force the member states to mount a joint response to the pandemic. It is also true that a declaration in March by European Central Bank president Christine Lagarde that the ECB would not close the spreads of Italian government bonds sent European stock markets plummeting and Italians into a rage.

On the other hand, the European Commission was quick to remind France, Germany, and other EU countries that their unilateral export restrictions on medical supplies would stymie any collective European response. It also activated the general escape clause of the Stability and Growth Pact, laid the groundwork for the reallocation of structural funds, and adopted the Temporary Framework for state aid measures. These allowed member states to depart from tight budgetary requirements and leverage additional funds to respond to the crisis. Still, a general disappointment with the EU’s early performance persisted.

In a rare occurrence for professional politics, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen offered a “heartfelt apology” to EU citizens. Drawing inspiration from the people of Europe, “standing together – with empathy, humility and humanity,” she pledged to take on a more proactive role in shaping and coordinating Europeans’ response to the coronavirus crisis. Her recent €750 billion economic recovery proposal is a case in point. The EU has ambitious plans: “An agreement on the Recovery Fund and the MFF will pave the way to Europe's economic recovery and bolster the green and digital transitions.”

A further key insight from ECFR’s findings is that European solidarity in the coronavirus crisis was an all-encompassing phenomenon. Attention received often correlates with influence enjoyed – smaller member states and civil society tend only to appear at the margins of most stories on European politics. This time, the tracker shows that things were different.

Estonia and Lithuania sent several tonnes of personal protective equipment and medical disinfectant to Spain and Italy through NATO’s Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre. Luxembourg was the first EU member state to welcome unaccompanied children from the virus hotbeds that are the overcrowded refugee camps in Greece. A Belgian military officer participated in Operation “Résilience” aboard the French helicopter carrier LHD Mistral on its mission to assist local authorities in the Indian Ocean in their fight against the pandemic through to July. Portugal, at the request of Luxembourg’s government, is planning to send 15 language teachers to support their colleagues until the end of the year and facilitate the orderly reopening of primary schools in Luxembourg. Hungary also made headlines: it delivered substantial amounts of personal protective equipment to neighbouring countries, though most of it was directed to ethnic Hungarian communities, receiving condemnation for “ethnic discrimination” from Romanians and revealing the occasional instrumentalisation of solidarity for political gains.

Moreover, for many Europeans, solidarity has been a deeply personal issue. To lift their neighbours’ spirits, Italians took to their balconies to play music and sing songs together. In solidarity, many across Europe, including a group of Germans in Bamberg, chimed in with their renditions of “Bella Ciao”. Czech 3D-printing pioneer Josef Prusa developed an open-source design for a 3D-printed face shield – the shield is now being produced by makers across Europe in support of medical professionals. And a collective of Baltic start-ups, with support from the European Commission, SpaceX, and others, hosted a global virtual hackathon to devise creative and practical solutions to the problems posed by the pandemic.

ECFR will continue to study Europeans’ response to the coronavirus crisis. Through to September, we will update the European Solidarity Tracker, add in new acts and declarations of solidarity, and refine our understanding of the public discourse across Europe. To find out more about how we define and operationalise “solidarity,” and how you can use the tool yourself and contribute to the growing database on European solidarity, visit the project website.

The European Solidarity Tracker is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe data project, which is funded by Stiftung Mercator.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.