Moving closer: European views of the Indo-Pacific

Summary

- The launch of the EU’s strategy for the Indo-Pacific should mark the beginning of a new approach to the region.

- But ECFR research shows that, despite the Indo-Pacific’s growing economic and political importance, many member states are still largely uninterested in events there.

- It will take more than just strong support from France, Germany, and the Netherlands to ensure that the new EU strategy for the Indo-Pacific is effective in the long term.

- The three countries have an opportunity to convince other member states that the region is vital to European sovereignty and prosperity.

- They can do so by creating visible projects that demonstrate their presence and intent in the Indo-Pacific, and by establishing coalitions for greater European engagement in areas such as technology and maritime security.

Introduction

The world’s economic and political centre of gravity has been shifting towards the Indo-Pacific for years. With China playing an increasingly dominant role in everything from trade to military power and technology, the relative decline of American supremacy is palpable. This poses a new challenge for Europe, whose economic future and geopolitical relevance is inextricably linked to developments in Asia.

It has been decades since policymakers across Europe focused intensively on any strategic development in the Indo-Pacific that did not involve trade. Since the early 2000s, the European Union has been busy dealing with issues at home or in its immediate neighbourhood.

The concept of the “Indo-Pacific” first emerged within the region – particularly in Japan and Australia – and reshaped the previously dominant “Asia-Pacific” narrative, mainly as a way to articulate these countries’ requirements for prosperity vis-à-vis China and their reliance on the US security guarantee. The Trump administration appropriated the concept and gave it a distinctly anti-China connotation. Until last year, the EU had not engaged with the idea of the Indo-Pacific on a broad conceptual basis, let alone defined its policy priorities for the region. The union feared that doing so would indicate alignment with the US and would alienate China. Therefore, the notion that there was an Indo-Pacific to deal with had gained little traction in Europe. But several EU member states have now begun to push Brussels to embrace the Indo-Pacific as a strategic concept.

France, Germany, and the Netherlands have, in different ways, drawn up national Indo-Pacific strategies in recent years. They have been the driving force behind the EU’s effort to find a more decisive approach to the region. This effort led to the release in April 2021 of the European Council’s conclusions on the “EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific”, which paved the way for the union to adopt an official strategy that can now initiate a new approach. To move from the drawing board to implementation, Europeans will need to answer several tough questions that are in tension with the consensual language of EU documents.

Can the EU really ‘get strategic’ about its interests and its member states’ priorities in the Indo-Pacific? Beyond countries that have a clear preference for a more active approach, are any member states strongly opposed to greater European engagement in the region? Will indifference prevail, or has the EU undergone a strategic awakening that will recentre its policymaking on the region’s enormous potential for European interests? (A question that applies to areas ranging from trade to the defence of the rules-based order, to the European Green Deal, to infrastructure finance and development assistance.) And what role does the China factor play?

It will likely take more than a strong push from France, Germany, and the Netherlands to ensure that the EU implements a long-term strategy in the Indo-Pacific. So, where do member states stand on these issues?

This paper draws on a survey that the European Council on Foreign Relations carried out to understand how key policy stakeholders in each member state view the prospect of a new form of European engagement with, and conceptual framing of, the Indo-Pacific. The results of this expert survey show that, despite the region’s growing economic and political importance, indifference to it prevails in many EU member states. This suggests that those leading the debate should make a greater effort to present a convincing story about why Europe should be active in the Indo-Pacific and how it can engage more effectively with its partners in the region – aiming to make use of its own strengths in a world of increasing great power rivalry.

The results of the survey highlight the intensity – or lack thereof – of the debate about the Indo-Pacific in each member state. These differences could eventually limit the impact of any strategic reorientation. There is a risk that the EU’s approach to the Indo-Pacific will be no more than the sum of disparate policies that are only weakly linked and that have no capacity to generate new partnerships between Europe and Indo-Pacific countries and organisations. To prevent this from happening, key players will have to turn the strategy into reality.

The data indicate that they can do so: given that indifference is a bigger issue than real opposition among member states, it should be possible to establish more decisive and visible European positions on Indo-Pacific matters. If select groups of member states create visible projects that signify their presence and seriousness in the region, they can generate momentum for greater European engagement – and thereby strengthen European sovereignty and prosperity. In this context, the Indo-Pacific strategy can be important to how Europe reshapes its role in the world.

An emerging strategy

In April, the Council of the EU released its conclusions on the “EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific” and the 27 EU foreign ministers formally invited Josep Borrell to present a new, fully fledged strategy for the region by September 2021. By EU standards, this was an achievement – 20 months earlier, the term “Indo-Pacific region” was not even used in official documents in either the EU or its member states. One exception was France, which had developed its own strategy in 2018 (before revising it in 2021) and had been pushing ever since for the adoption of an EU-level equivalent. With regard to its overseas territories in the region, France is the only European country that sees itself as a “resident power” in the Indo-Pacific. Without such a role, other member states seemed wary of formally adopting the concept. This is due to its geopolitical connotations. Germany’s release of its “Policy guidelines for the Indo-Pacific region” in September 2020, soon followed by the Netherlands’ own guidelines, marked the beginning of a demonstration on the part of countries beyond France that one does not need to be a resident power to have, and clearly formulate, one’s interests in the Indo-Pacific.

The debate on the region has, therefore, now begun to gain traction. It has ultimately led to the release of the Council’s conclusions – which will, in turn, result in an actual EU strategy. The publication of the conclusions needed to be approved by all 27 EU foreign ministers, meaning that every member state was forced to deal with the issue of the Indo-Pacific at this level.

The speed of the shift, though, is symptomatic of a change in perceptions of international power relations and their potential impact on Europe. Europeans have been forced into a rethink by their fears about the consequences of China’s rise – and by their uncertainty about the United States’ commitment to European security and its willingness to protect European interests from the potentially negative consequences of the Sino-American rivalry. Together, these factors point to the centrality of the China question – leading to increasingly difficult questions about the posture the EU should adopt vis-à-vis Beijing. And, while the transatlantic relationship cooled significantly during the Trump era, Beijing’s geopolitical activities – from its “mask diplomacy” during the covid-19 pandemic to its actions in Hong Kong and Xinjiang – have dispelled Europeans’ relative optimism about the future trajectory of EU-China relations. There has been a significant rise in pressure on Europe to adjust to the increasingly polarised and tense relationship between China and the US.

So far, Europeans have fallen short in their efforts to articulate a response to these developments. The US strategy for the Indo-Pacific explicitly names China as a “strategic rival”. In contrast, the national strategies of France, Germany, and the Netherlands seek to avoid difficult positioning on the China question by insisting on “inclusivity” – suggesting that Beijing should be more of a partner than a rival. The real division within Europe, though, does not seem to concern whether China is part of the Indo-Pacific concept. Rather, it involves two opposing approaches to inclusivity. The first approach reflects nothing more than a desire to avoid the China question by insisting on the need for cooperation with all, and by glossing over the potentially problematic aspects of the relationship. The second approach acknowledges conflicts of interest and differences in values with Beijing, but nevertheless calls for continued cooperation with China, as a way to push Beijing to adhere to internationally accepted standards and forms of behaviour.

The division that runs through Europe’s ambivalent approach to Beijing comes from fundamental differences in the ways that member states address the China challenge. This becomes particularly obvious when one compares the French strategy with the German guidelines. The French insisted from the beginning on the need to prevent the emergence of a new hegemon and to re-establish a “level playing field” in Europe’s relations with China. However, the German text only carefully alludes to the notion of countering China and devotes significantly more attention to the economic opportunities offered by the Indo-Pacific “region” rather than to the underlying security questions.

The survey

ECFR’s pan-European network of national researchers conducted qualitative interviews with stakeholders in their respective EU member states. The stakeholders included policymakers, members of parliament, relevant ministries, and leading experts from academia and the not-for-profit sector. A questionnaire was designed to help facilitate the interviews and produce comparable results. The answers selected were predefined in a survey but were chosen on the basis of researchers’ overall assessment of views in their member states. Participants’ responses only relate to the EU’s emerging strategy, and may differ from national preferences.

The French had been pushing for an EU strategy since 2018, but it was only after the publication of the German guidelines that enough momentum was generated for other member states to endorse the Indo-Pacific concept. The fact that the two countries, as well as the Netherlands, jointly pushed for a pan-European strategy eased the process. Yet it did nothing to eliminate the divides between European states in their willingness to stress their differences with China. Nor will the EU’s resulting Indo-Pacific strategy. While it is still unclear how significant the strategy will be, this will be determined by two things: its content and, ultimately, its implementation. Europe will need to set measurable goals and work to achieve them by making a sustainable financial and security commitment to the region.

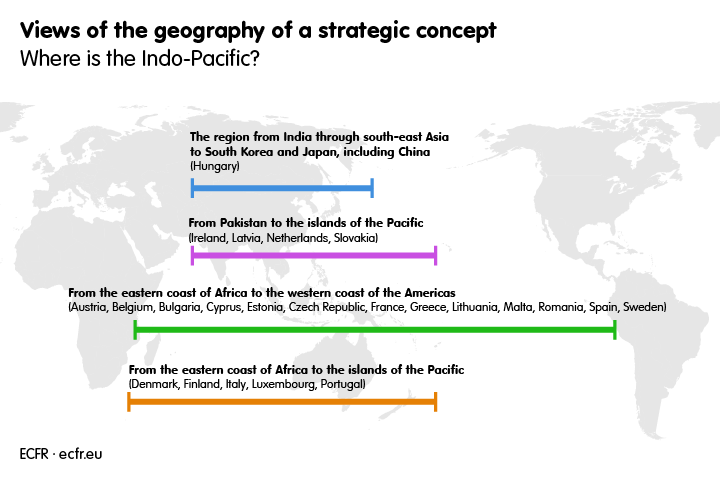

It is remarkable that the EU has got as far as it has. Member states do not yet even agree on a geographical definition of the Indo-Pacific or what the concept means. The Indo-Pacific is not a predetermined space in which one can apply the national strategies of states – let alone a European strategy. Instead, the specific interests of states shape their understanding of what and where the Indo-Pacific is. This is by no means an academic debate. Divergent definitions indicate divergent interests – and, potentially, varying degrees of involvement in the creation of an EU Indo-Pacific strategy. More importantly, these differences in countries’ concepts of the Indo-Pacific as a geographical area could limit their participation in policies.

European countries face many of the same challenges as their partners in the Indo-Pacific. And geography is relatively unimportant on some of these issues, such as the potential risks of emerging technologies, ensuring supply chain resilience, countering disinformation, and managing China’s growing assertiveness. Therefore, Europe’s new outlook on the Indo-Pacific stems from a political recognition of the need to shoulder greater global responsibility. But it also reflects a desire to have an impact on the affairs of a region that is far away but whose fate is intertwined with Europe’s own.

The strategic significance of an EU Indo-Pacific strategy

Europe’s divisions over how to approach the Indo-Pacific clearly emerge in ECFR’s expert survey. Ten EU member states from across the continent view the adoption of an Indo-Pacific strategy as both a way to deal with China and a way for Europe to take advantage of new economic and other opportunities. But, for 13 states, the Indo-Pacific concept is merely a field of opportunity to pursue economic interests, and the China question does not figure prominently. Only Latvian policy elites appear to see an upgrade of Indo-Pacific policy as truly an anti-China tool. This split reflects member states’ differing views about whether to consider the Indo-Pacific in strategic terms or economic terms. As many of them lack major military capabilities, they may assume that the broader geopolitical shift taking place is one that can be dealt with only by larger EU member states or the US. Some may not even have strong economic connections but may assume this would still be the main way to engage with the Indo-Pacific. The lack of consensus is illustrative of the ambivalence in Europe about how or even whether to devise a comprehensive and strategic approach to the region.

You can see the Indo-Pacific strategic scorecard on ECFR’s website.

In terms of how the question relates to the transatlantic partnership, 11 member states regard the adoption of an EU Indo-Pacific strategy as an assertion of “European strategic autonomy” – Europe striking out on its own, without the need for the US to support it. Eight view it as a way of managing the transatlantic alliance – potentially keeping the US engaged as Washington focuses more on the Pacific rather than on Europe. Six countries see the launch of an EU Indo-Pacific strategy as part of an explicit effort to align with the US and support it in the region. These views are not mutually exclusive. And, ultimately, the emerging strategy has not expressed a clear geopolitical position on why the EU is drawing up new plans. While a clearer articulation of its stance could no doubt prove controversial, it would be necessary to ensure the strategic approach has a backbone that holds the whole concept together.

If any pattern is to be discerned, western European countries tend to perceive the coming launch of an Indo-Pacific strategy as an assertion of strategic autonomy, as do the Czech Republic and Slovakia. In contrast, almost all countries that see the creation of an Indo-Pacific strategy as a sign of alignment with the US were once members of the Soviet bloc. The one exception is Portugal. But many states categorise the launch of the Indo-Pacific strategy in more than one way. Western European states tend to view the prospect of an EU Indo-Pacific strategy as both a way to manage the transatlantic alliance and an assertion of strategic autonomy; eastern European states regard it as a way to manage the transatlantic alliance and align with the US.

But this geopolitical positioning goes far beyond the transatlantic dimension. When asked which partners in the region the EU should work with to ensure its strategy succeeds, only five countries name the US – the same number as those that select India. Even after Brexit, the United Kingdom receives seven mentions. This could be because several states – especially those in eastern Europe and the Baltic region – implicitly rely on the US to ensure the security of their interests in the Indo-Pacific. Accordingly, they may take this cooperation as a given. But it might also be the direct consequence of the launch of the UK’s Integrated Review only a few weeks before the survey was conducted; the document had a strong focus on the Indo-Pacific and a consistency of intent that is difficult to achieve in a union of 27 countries. The perception may also have been reinforced by Britain’s past colonial relationship with significant parts of the Indo-Pacific region, creating the impression that it is an important player with which close ties are not only possible but also likely.

Remarkably, 12 EU member states name China among their top three key partners in the Indo-Pacific. This is logical, as a number of European states still see China primarily as a potential market. That said, five countries – Belgium, Bulgaria, Latvia, Portugal, and Romania – also define the Indo-Pacific strategy as being at least partly an anti-China tool.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) emerges as the most popular candidate for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific: 21 countries regard the organisation in this way. Supporting the ASEAN-led regional architecture makes strategic sense from an EU standpoint, because strong relations with several partners in the region may also support EU member states’ posture against China’s political influence. Europe clearly favours a multilateral approach to foreign policy – as opposed to the bilateral one Beijing prefers. Therefore, engaging with individual members of ASEAN such as Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines does not appear to be a priority for most European governments. European countries see other multilateral formats as significantly less potent – each received only one mention: the Asia-Europe Meeting (Cyprus), the Indian Ocean Rim Association (Italy), the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (Portugal), and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation and the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (Sweden).

The EU and security in the Indo-Pacific

For Europe as a trading power, the security dynamics that matter most in the Indo-Pacific region are playing out in the maritime realm. When speaking about maritime security, EU countries often focus on the security of the sea lines of communication. But the concept of maritime security is evolving to cover far more than guarantees of safe passage for commercial vessels. Europe needs to focus on the protection of not only maritime routes but also freedom of navigation, the exclusive economic zones of several actual and potential partner countries, the oceans, data traffic through undersea cables, and marine biodiversity.

You can see the interactive Indo-Pacific security scorecard on ECFR’s website.

As ECFR’s survey shows, 23 EU member states consider security, broadly defined, to be an important component of an EU strategy for the Indo-Pacific. Only four states see security as unimportant to such a strategy. Those that characterise security as “very important” for an EU Indo-Pacific strategy are mainly from eastern Europe and the Baltic region: the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, and Slovakia. Estonia, Latvia, and Romania explicitly link this assessment to their relationship with the US. This relates to the importance they ascribe to the US as a partner in general and the understanding that supporting Washington in a range of policy areas will strengthen the American commitment to providing security in Europe. The survey results suggest that Latvian policy elites think the US should be an explicit part of any European approach to the Indo-Pacific.

The US dimension is also key for some states that view the security dimension of the EU strategy for the Indo-Pacific as “somewhat important”. Finland, for example, explicitly refers to the importance of cooperating with like-minded countries such as the US. For Belgium and Bulgaria, there is a strong connection between China’s rise and the security dimension of an EU Indo-Pacific strategy. But there are also outliers: Portugal appears to be against linking any security strand to specific interstate territorial or maritime disputes. Surprisingly, France – which is the most militarily engaged EU country in the Indo-Pacific – sees the security dimension of the EU strategy as only “somewhat important”. ECFR’s research suggests that this dimension ought only to complement France’s own security policies, in which cooperation with the US – as well as Australia, India, and Japan – is an important component.

Interestingly, the US factor also influences thinking in countries that see security as unimportant for the EU strategy for the Indo-Pacific. Lithuania has little security interest and capacity in the region, but it agrees that it is important to include security in a future Indo-Pacific strategy – as this may help sustain the United States’ involvement in Europe. Overall, the importance of security to the EU strategy for the Indo-Pacific is, explicitly or implicitly, a function of its value in demonstrating dedication to the alliance with the US, thereby securing the American commitment to Europe. These considerations at least partly explain why states with limited military capacities to dedicate to the Indo-Pacific – the Czech Republic, Estonia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, and Slovakia – support the idea of the EU increasing its investment in maritime security activities in the region. It is questionable whether this will translate into an actual mobilisation of resources from these countries for security in the Indo-Pacific. However, political support from these countries could be useful if the EU wants to build a coalition of individual EU states, one that commits to doing more to defend European interests in the region.

The survey asked what types of security cooperation or support member states would like the EU to invest in, as well as those to which they are ready to contribute. Twenty-one states view cyber security as a priority for the EU – more than see maritime security in this way. Their perceptions could be partially explained by the fact that Indo-Pacific maritime security involves only a limited direct threat to European territorial sovereignty and integrity, while the immediate effects of cyber attacks are already palpable in Europe itself. Equally, cyber security is an area in which there could be a huge opportunity to not only strengthen Europe’s defensive capabilities at home but also enhance European security through information exchange with partners in the region that face similar challenges.

Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovakia, and Sweden say that counter-terrorism should be included as part of the security dimension of any future strategy. This may be because of these countries’ history of terrorist attacks on their territory.

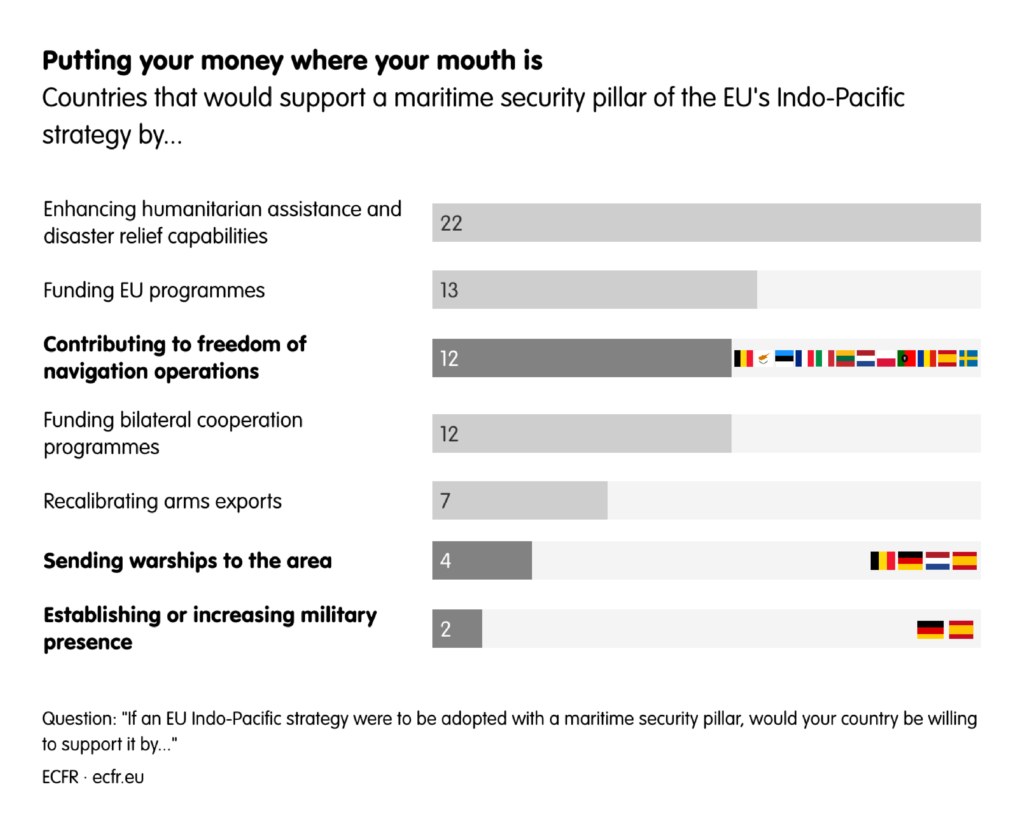

Stating that security is important is one thing, but how many countries are prepared to put their money where their mouth is? Only a limited number of member states are willing to contribute to maritime security activities. Twelve states are prepared to participate in freedom of navigation operations, but only Germany and Spain say they are willing to establish or increase their military presence in the Indo-Pacific. And both are ready to send warships to the region – as are Belgium and the Netherlands. With only these countries happy to contribute, there may be a disconnect between actions that countries recognise as important and the means they are willing to commit to them. This could mean that the EU will make little active contribution to the security of the Indo-Pacific. But it could also serve as an incentive for the EU to become involved in Indo-Pacific security based on its actual capacities – such as by, for example, helping littoral states in the region control their exclusive economic zones.

In this context, policymakers in some member states also highlight the link between maritime security and support for the sustainability of the oceans. Fisheries management is of particular importance, as this activity is an economic, environmental, and – increasingly – geopolitical issue. As demonstrated by long-standing territorial disputes between China and neighbouring countries in the South China Sea, fisheries management contributes to the evolution of the strategic landscape. This landscape is characterised by not just the military balance of power – an area in which Europe has clear deficits that it can hardly address in the short term – but also a mixture of capabilities to deal with various challenges.

By including the issue of fisheries in an Indo-Pacific strategy, the EU would not only do justice to European interests in this realm but would also establish a presence in a contentious area in which it has ample experience. Fisheries management is a highly relevant issue in the region and has enormous security implications. It is one in which Europe can be of value beyond its military capacity and can help contribute to security by supporting multilateral approaches that are non-confrontational, inclusive, and consistent with EU interests and values.

Similarly, most member states are ready to contribute to humanitarian assistance and disaster relief capabilities. Thirteen states are willing to contribute funds to EU operations, and 12 are willing to operate through a bilateral cooperation programme, in these areas. These last two options are not mutually exclusive: eight countries are willing to contribute to both EU and bilateral cooperation programmes. This suggests that Europe has options when it comes to engaging with the region – and that it can support its Indo-Pacific partners through both bilateral and multilateral engagement as appropriate.

The survey data indicate that member states generally support an increased European commitment to maritime security in the Indo-Pacific, but that only a few of them are willing to dedicate military capabilities to protecting European interests. There is a clear preference for limiting involvement to non-military activities. The EU will continue to lack credibility on ‘hard security’ in the region. But, even if its non-military contributions are not decisive, it could still be an important source of support for its partners in the region as they manage a multitude of new security scenarios.

Diversifying economic relations and developing markets

The Indo-Pacific is key to global growth. Currently, it is the second-largest destination for exports from the EU and home to four of the bloc’s top ten trading partners. In 2019 the region accounted for more than 40 per cent of Germany’s non-European trade in goods – a share that will only increase (particularly during the post-coronavirus recovery). India, for instance, is the world’s largest openly accessible data market. And, by 2025, India and Indonesia will collectively account for almost 25 per cent of the world’s data users.[1]

The vast majority of EU member states see the Indo-Pacific as an area of huge economic opportunity. At a time of increasing great power rivalry and enormous localisation pressure in China, there is a growing need for diversification within the region away from the dominant Chinese market. This is particularly true for German industry, which is heavily involved in the Chinese markets and deeply intertwined with China through its supply chains. German companies have woken up to this challenge and are also pushing for a diversification agenda, reinforcing the political dynamic at the EU level.

You can see the interactive Indo-Pacific economic development scorecard on ECFR’s website.

As shown by ECFR’s survey, nine member states – Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, and Romania – regard enhanced economic engagement with the region as not only part of a diversification strategy but also a tool to counter China.

In EU member states’ bilateral relations with countries in the region, differing assessments of China – of how to constrain or accommodate the country – are currently less relevant. However, as soon as the EU wants to act jointly and use its collective leverage and resources, these differences could create significant tensions. This holds true for inclusive multilateral trade agreements and the EU’s oft-mentioned connectivity strategy.

Connectivity

Connectivity – as defined by Brussels in the EU-Asia connectivity strategy – is intended to bring countries, people, and societies closer together. It is supposed to facilitate closer economic and personal relationships. ‘Hard’ connectivity includes the construction of physical infrastructure, electricity transmission systems, and the bases for data transfers; ‘soft’ connectivity includes people-to-people exchanges and the harmonisation of regulatory standards to enhance cross-border trade. Connectivity is one of the key areas in which the EU can enhance cooperation and deepen its relationship with the Indo-Pacific.

The adoption of the EU-Asia connectivity strategy by the European Commission in September 2018 came to feature prominently on the evolving EU agenda on the Indo-Pacific. This was widely interpreted as an attempt to provide countries in the region with an alternative to Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative. European officials view connectivity as a geopolitical tool that can help promote the strategy, interests, and values of the EU in the Indo-Pacific by enhancing the EU’s strategic autonomy and its ability to act. But the wide range of topics that fall under the broad definition of “connectivity” also means that individual member states are often driven by very different priorities.

When asked to describe the nature of the debate on connectivity, 12 EU member states reported that the domestic discussion on the issue was rudimentary or non-existent. Among those reporting that debates on connectivity were taking place within their country, 11 stated that they focused on digital and transport issues, while seven said that energy was the main concern – underlining a focus on hard connectivity that produces tangible structures such as roads, bridges, and energy grids. Six countries see trade as the key feature of connectivity.

When asked how to choose connectivity infrastructure projects in the region, 19 states said that European economic interests should be the main priority. This rests on the prevailing logic in Europe that projects should only be funded if they are economically viable and sustainable. It also is indicative of the commercial opportunities for European companies in this context. European companies have not played a massive role in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, meaning that they have been missing out on market share and massive public spending. Only four countries directly said that countering China should be a priority of Europe’s connectivity push in the region. But the interviews ECFR conducted in ten countries – Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Slovakia – indicated that China or the Belt and Road Initiative serve at least as a backdrop for the strategic thinking on connectivity in the Indo-Pacific region.

From trade as strategy to trade versus strategy?

For decades, trade and investment have been at the heart of Europe’s approach to the Indo-Pacific, and have dominated its relationship with countries in the region. Does Europe, following its Indo-Pacific awakening, want to become a strategic partner for these states? And how important will trade be in their relationships?

The results of the survey indicate that most EU member states still mainly view the Indo-Pacific as a region of economic opportunity. But as the covid-19 pandemic has laid bare the risks of globalised supply chains and markets, deglobalisation trends are becoming more apparent around the world. Some countries in Europe have remained relatively immune to this: ECFR’s survey indicates that Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Greece, Italy, Malta, the Netherlands, and Slovakia believe that the benefits of globalisation outweigh its costs.

However, as this paper’s country reports show, there has only been a debate on deglobalisation in 19 member states (in differing forms and intensities), correlating with their exposure to international trade. In most countries, the debate has revolved around how to balance the risk of overdependency, notably on China, and the vulnerability of supply chains with the risk that deglobalisation will have a negative impact on their economies, resulting in a loss of global market share, international business, and jobs at home.

As such, the survey shows that European countries largely see the globalisation debate as a search for ways to manage risk and better balance national and international interests – leading to considerations about opportunities to modernise national industries and, often, about reshoring or nearshoring, as well as the ‘reindustrialisation’ of Europe. This debate is sometimes opportunistic: some countries hope to benefit from nearshoring by major European producers such as Germany, which might decide to relocate their production facilities from China and other Asian countries to states closer to home. Overall, though, the survey suggests that debate in Europe focuses more on trade diversification than on reshoring production capacities. This is partly due to the difficulty of moving production away from China. It is also due to the fact that growing demand in south and south-east Asia means that there will be an increasing number of customers close to the site of production.

These considerations are also reflected in the preferences EU member states express about potential trade agreements between the EU and Indo-Pacific countries. Their views on the matter are particularly important in the context of an EU strategy for the Indo-Pacific, as the union’s competencies in trade allow it to act in a more unified fashion than it can in most other areas. Additionally, trade agreements involve not only economic but also geopolitical interests, as they encompass a broad set of values, norms, and standards. The EU has engaged in a broad push to sign additional free-trade agreements (FTAs) in the Indo-Pacific region since the effective failure of the Doha round negotiations at the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2008. This has already led the EU to conclude FTAs with countries such as Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Vietnam, and to negotiate with a number of others, including Australia and Indonesia. Within the scope of its latest Indo-Pacific push, the EU restarted negotiations with India in 2021. A multitude of bilateral FTAs, however, is only the second- or third-best option. In the absence of a reformed WTO structure, these FTAs serve European interests in supporting free and equal trade, while adding important new areas such as data and digital trade to the regulatory framework. A broader FTA that encompassed many states in the Indo-Pacific – and that harmonised the trade environment for European businesses active in the region – would be preferential to a series of bilateral arrangements. Such a deal would make it easier to do business across a larger geographical space and different legal environments. But, so far, this has not been possible.

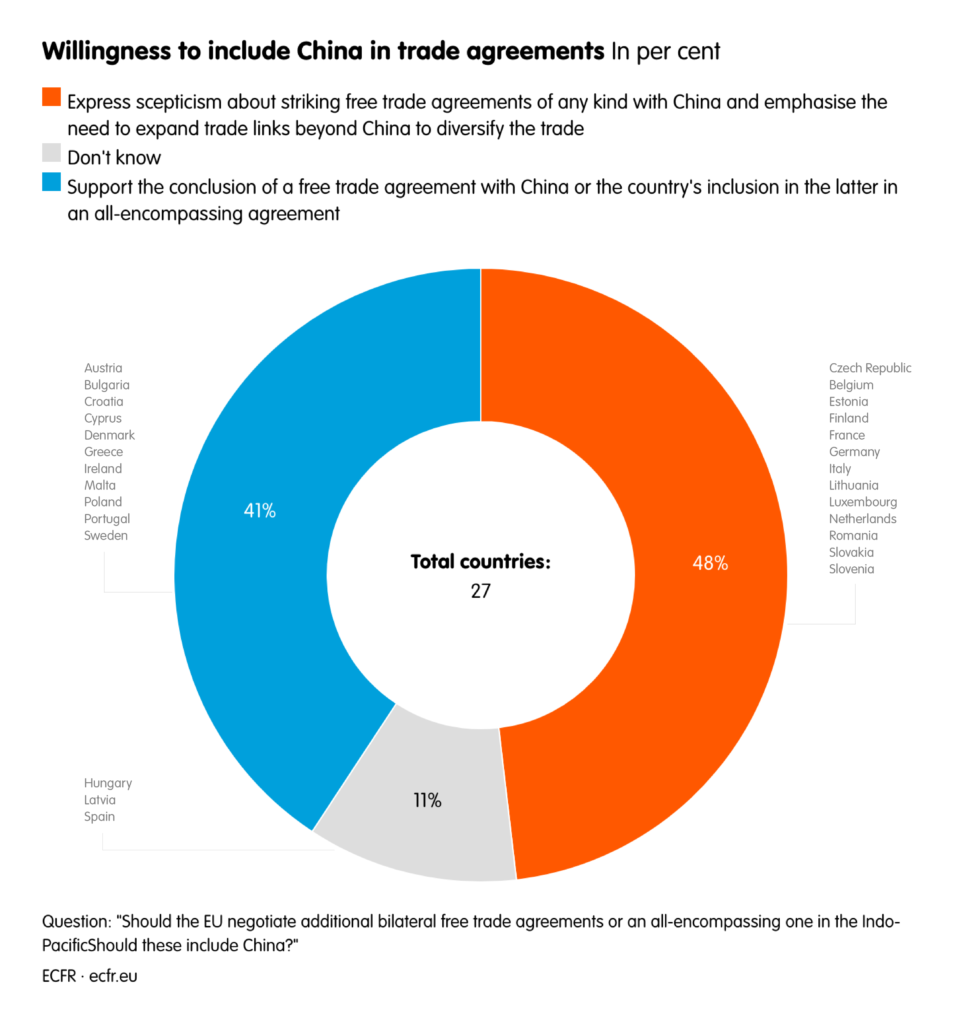

In this sense, Europeans’ attitudes towards the possibility of an FTA with China, and China’s inclusion in larger trade agreements that the EU may conclude in the Indo-Pacific, are significant. EU member states are divided on these issues. Ten of them support the conclusion of an FTA with China or the inclusion of the country in an all-encompassing agreement. Policy elites in Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Malta, Poland, and Sweden believe that China cannot or should not be excluded from potential trade agreements with the EU. However, they express some ambivalence on the issue. Senior officials in Bulgaria, for example, fear that China could sabotage an all-encompassing trade agreement by putting pressure on other Indo-Pacific actors.

Unsurprisingly, however, 14 member states’ scepticism about China’s potential participation in EU trade agreements reflects ambivalence more than principled and blunt opposition. In Belgium, for instance, key stakeholders suggest that the country would support the conclusion of a trade agreement with China conditioned on Beijing’s respect for international law. Stakeholders in Finland and Portugal express similar views, declaring that China should not be excluded but ought to be held to the same standards as others. It appears that the Netherlands would make a deal with China conditional on the latter adopting the standards and norms that Europe incorporates in all its free-trade arrangements – ranging from environmental protection to labour rights and data privacy. German policymakers do not openly question a comprehensive trade relationship with China but do emphasise the need to extend its trade links beyond the country, aiming to strike the right balance between rivalry and partnership. Their French counterparts express political concerns about including China in a future trade agreement.

There is a broad consensus in attitudes towards the overall approach the EU should adopt. All member states support the conclusion of bilateral FTAs with countries such as Australia, Indonesia, Japan, and India rather than all-encompassing agreements – which are more complex, lengthier, and sometimes unrealistic. Eleven countries see ASEAN as one of the top three entities with which the EU should aim to create an FTA. Eight would rank members of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership as key partners. But, even for a country such as Germany, which has made the conclusion of an FTA with ASEAN one of the objectives of its own policy guidelines on the Indo-Pacific, such an agreement should only be the outcome of a gradual process in which the creation of a network of FTAs will be the basis of a future interregional agreement between the EU and ASEAN.

The quasi-consensus among the 27 EU member states on a high-standards agreements may make it difficult for the EU to conclude FTAs with groupings of any kind. At least 25 member states agree that there is a need for strong environmental standards, intellectual property protections, competition regulations, and measures on subsidies or state-owned companies. These preferences are already reflected in the way in which the EU concludes FTAs in the region, generally by negotiating with a number of smaller, less developed countries. The union’s FTA with Vietnam stands in contrast to this. The fact that the EU has been able to conclude this agreement suggests that it is the gold standard for FTAs with a developing economy in the region.

Technology

Against the backdrop of the strategic rivalry between the US and China, competition over technology is set to become a major area of friction between states. More than any other domain, technology presents EU member states with a dilemma in which their relative weakness is difficult to address. To foster digital governance based on international norms and standards, Brussels will need to work closely with its like-minded partners in the Indo-Pacific. The EU has already acknowledged the region as critical to Europe’s digital interests – and is, therefore, widely expected to include technology in a comprehensive Indo-Pacific strategy.

There is no discernible pattern in member states’ priorities on technology. Fifteen countries regard the issue of 5G as important within Europe, but only Sweden and Latvia view 5G partnerships – which, in the past few years, have been at the centre of EU discussions on the connectivity strategy – as the top priority. Research and development cooperation is the top priority for nine countries and the lowest priority for seven others. Concern about cyber security is not concentrated in any geographical area, with Croatia, the Czech Republic, Finland, and Slovenia regarding it as their top priority. Seven countries – among them Denmark, France, the Netherlands, and Slovakia – list cyber security among their two lowest priorities for the technological dimension of the EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy.

Conclusion

ECFR’s survey confirms the centrality of the China question to Europe’s relationship with countries in the Indo-Pacific and its foreign and economic policymaking more broadly. The EU’s Indo-Pacific awakening has been largely prompted by shifting geopolitical realities and changes in its relationship with China – as well as developments within the country.

The EU’s long-term strategic approach to the Indo-Pacific will need to account for these drivers. Concerns about China appear to shape all the views that member states expressed on the potential components of Europe’s future engagement with the region. Most member states are not significantly dependent on trade with China. Yet the Chinese market’s potential as a future source of growth and prosperity looms large across Europe, often affecting member states’ willingness to clearly position themselves on contentious policy issues.

As China’s growing assertiveness and rivalry with the US increase tensions in the Indo-Pacific, it will be increasingly hard for Europeans to remain neutral. However, the results of the survey suggest that European capitals have not yet fully understood the significance of the strategic shifts that have taken place in the region and the effects they will have on Europe’s capacity to act. Instead, a sense of economic opportunity and the notion of strategic neutrality often prevail among member states – as seen in their overwhelming support for partnering with multilateral organisations such as ASEAN.

Only France, the Netherlands, and Germany have the security capabilities and the willingness to protect Europe’s interests related to the rule of law and stability in the region, as well as to provide military support to countries there that face increasing challenges to their territorial and economic sovereignty. Some other European countries (particularly the Baltic states) recognise the security challenges in the Indo-Pacific but are likely unable to help address them in a significant way.

Leaders in member states and the upper echelons of the EU are increasingly aware that greater strategic engagement with the Indo-Pacific is crucial to defining Europe’s role in the world, but most of them currently intend to do so at a minimal cost. Few are willing to push this logic to its conclusion. In this context, many European capitals conceive of strategic autonomy as an assertion of neutrality – the ability to not have to choose between the US or China – rather than as a way of leveraging the collective power of Europe’s strategic partners and actively shaping decisions and the political environment.

This is evident on issues such as connectivity, for which there is no clear set of criteria for the initiation, administration, and financing of projects identified by EU member states. Most member states favour a purely economic approach rather than a strategic one. This approach, which is in line with the business interests of some European companies, could create a policy to foster green and sustainable growth, as well as labour rights and other forms of European standards-setting. The same factors that have hindered the EU-Asia connectivity strategy could ensure that this issue is irrelevant to Europe’s overall approach to the Indo-Pacific – if a lack of measurable outcomes, such as visible connectivity projects, convinces third parties that there is no reason to adopt European norms and standards.

Similar strategic confusion prevails on almost all matters, including technology and trade. In both cases, the challenge created by China’s rise is becoming clearer, but the EU is yet to take a more assertive approach to the Indo-Pacific or clearly prioritise its partners in the region.

Ultimately, there is a real risk that Europe’s strategic approach to the Indo-Pacific may be no more than a set of principles without any real substance to back them up. This would convey no real political message to either friend or foe.

In the near future, the EU may still need to take a cautious approach to the region, to ensure that its engagement remains commensurate with its evolving capabilities. But the new strategic landscape makes it increasingly clear that neutrality is no longer an option. The EU and its member states will have to acknowledge their differences with China even more directly than they already do.

In the current context, it is unlikely that all member states will agree on a single concept of the Indo-Pacific and, accordingly, develop common and consistent policies on all its components. Instead, EU member states should adopt an approach that uses the forthcoming EU Indo-Pacific strategy as a framework in which to develop policies that will be implemented by various European coalitions. This could enhance Europeans’ capacity to act, increase Europe’s visibility in the region, and underscore the EU’s willingness to play an active role in shaping the emerging geopolitical dynamics.

The creation of an Indo-Pacific strategy is a remarkable step forward for the EU and most member states – but it remains a self-centred effort. Europe should work more closely with Indo-Pacific countries to shape its longer-term approach. It will be key for Europe to understand its Indo-Pacific partners’ differing expectations. Making these expectations known and understood is the responsibility of the partners themselves. An institutionalised consultation process could help the EU move from strategy – which serves as a starting point for a new approach – to effective and mutually beneficial implementation. The EU’s connectivity partnerships with India and Japan show how an institutional dialogue, if done right, can lead to real change and can lend Europe greater visibility and political weight in the Indo-Pacific.

It would be unrealistic to expect all 27 member states to suddenly engage with issues such as maritime security, for example, when they lack the basic assets to do so (and acquiring these assets would take years of sustained development and investment). But European countries can focus on high-demand, if slightly more niche, contributions in line with their capacity – fisheries management being a case in point.

Limited capabilities can no longer serve as an excuse for inaction. The development of an effective strategy on the Indo-Pacific will take years; Europe will not address all issues at the same pace. But Europeans no longer have the luxury of ignoring these challenges. The adoption of an Indo-Pacific strategy is dictated by necessity. It is not a choice between confrontation or accommodation vis-à-vis China. It is a choice between carefully balancing the relationship with China or capitulation – between asserting oneself on the international scene or becoming irrelevant.

Europeans would be well advised to look at the strategic constraints of some of their main economic and strategic partners in the Indo-Pacific, including Australia, India, and Japan. All these countries are much more economically dependent on China, and are at much greater security risk due to geographical proximity. None of them can afford to provoke Beijing, but they all know that complacency is no solution. Each of them has developed an Indo-Pacific strategy to balance economic necessity with security imperatives. None of them has better capabilities than Europe. But, equally, none regards Chinese hegemony as inevitable. All of them maintain some level of economic and political engagement with China while looking for security guarantees in their respective partnership with the US and, increasingly, building coalitions with one another. Therefore, it would make sense to discuss the implementation of the forthcoming EU strategy with each of them.

Ultimately, the process of developing an EU Indo-Pacific strategy has been inherently valuable. It has triggered a debate in Europe beyond France, Germany, and the Netherlands and thereby moved the Indo-Pacific up the European agenda. It is reasonable to expect that the process of bringing forward this strategy will contribute to a more accurate awareness of both Indo-Pacific dynamics and their importance for Europe – as well as a new mindset that could lead to more coherent and significant policies. As Europe gradually abandons a naive China policy, this could be a historic opportunity to fulfil the potential of a pan-European approach to the Indo-Pacific.

Analysis by country

Austria

View of the Indo-Pacific

Austria’s Indo-Pacific policy is led by its federal chancellery, which regards the goal of a joint EU strategy on the region as somewhat important to its defence and foreign policy goals. The chancellery views the strategy as both an opportunity to pursue European interests in the region and as an anti-China tool. For Vienna, the European Union’s strategy on the Indo-Pacific should be driven by an assertion of European strategic autonomy that aims to protect EU economic interests, address coercion by systemic rivals, and promote environmental sustainability. As such, Vienna’s vision for the Indo-Pacific encompasses the entire region, stretching to the west coast of the Americas.

EU Indo-Pacific strategy

Vienna supports the EU’s adoption of an Indo-Pacific strategy as a means to not only protect European interests in the region but also contain Beijing. Austria generally emphasises cooperation with democratic nations, prioritising partnerships with South Korea, the United States, and Japan rather than China. The exceptions are Australia, which it does not prioritise, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) – which it does prioritise, but which includes a mixture of democratic and authoritarian countries.

European security

Security plays a crucial role in Austria’s engagement with the Indo-Pacific, particularly with regard to the security of supply chains – which have been dramatically affected by the covid-19 pandemic – and freedom of navigation. Against this backdrop, Vienna supports security investment in cyber, counterterrorism, crisis management, and conflict mediation. As a landlocked country, Austria attributes limited importance to the sustainability of fisheries management and maritime sustainability. Nevertheless, should the EU Indo-Pacific strategy include a maritime security pillar, Austria would welcome an approach focused on humanitarian assistance and disaster-relief capabilities, as well as funding for cooperation programmes, which it would implement both bilaterally and through the EU.

Economic development

Austria sees connectivity as primarily an instrument of influence and coercion, as well as part of development. Moreover, the Austrian public debate on connectivity prioritises the creation of digital and transport infrastructure, and is particularly concerned with energy and transport, digital connectivity, supply chains, human capital, and efforts to offset China’s influence. From this perspective, the implementation of multilateral standards for quality infrastructure investment should be regulated by the G20 Principles on Quality Infrastructure Investment and managed through international organisations in Vienna. Funding for connectivity projects should mainly come from countries in the region and the EU. On technology, Austria regards data governance and cyber security as the main priority, and is relatively unconcerned about the future of labour and research and development.

Although Vienna remains wary of free trade agreements (FTAs) in general, it would prefer to pursue a bilateral FTA between Brussels and Beijing rather than an all-encompassing one in the Indo-Pacific. Domestically, discussions about the need to establish a legal framework for the diversification of supply chains are driven by citizens – particularly in relation to environmental standards, which Austrians rank as “very important” alongside climate protection, social standards, fair competition, and regulations on subsidies and state-owned enterprises.

Belgium

View of the Indo-Pacific

In Belgium, discussion of Indo-Pacific is led by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which sees the goal of achieving a joint European approach to the region as moderately relevant to the pursuit of its defence and foreign policy. The Belgian government views the Indo-Pacific as stretching from the east coast of Africa to the west coast of the Americas, believing that the EU should protect its economic interests across the region.

EU Indo-Pacific strategy

Belgium sees the adoption of an EU Indo-Pacific strategy as an opportunity to manage the transatlantic alliance and develop an anti-China strategic tool. The Belgian government reasons that it is best to keep its friends close and its enemies closer – in the sense that active engagement with China should help it monitor the country’s rise up close. Belgium wants to form key partnerships with democracies in the Indo-Pacific, including the United States, India, Japan, South Korea, and Australia.

European security

Belgium perceives security operations in the Indo-Pacific as only mildly important, especially in relation to China. The Belgian government’s multifaceted approach to Beijing is shaped by a wariness of China’s rise (which has been heightened by the pandemic); an awareness of issues such as Chinese espionage and threats to freedom of navigation; and a desire not to alienate China, whose support is vital to policy in a range of areas, from diplomacy with North Korea to climate change and trade. In the Indo-Pacific more broadly, Belgium supports greater European investment in maritime, cyber, and environmental security; crisis management and conflict mediation; freedom of navigation operations; humanitarian assistance and disaster-relief capabilities; the deployment of warships; and marine sustainability under the framework of climate protection. The country would also like to recalibrate European arms exports.

Economic development

Belgium’s public debate rarely touches on the EU’s connectivity strategy but, when it does, it frames this in terms of measures to contain an increasingly threatening Beijing. The Belgian government wants the strategy to act as a counterweight to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, promote national and EU exports, and support sustainable development. Belgium would like Europeans to pursue these goals with funding from a combination of sources but with an emphasis on the EU. It believes that Europe’s approach to the Indo-Pacific should focus on key digital technologies, followed by transport infrastructure – focusing on projects suited to European economic interests – and climate change. Seeing the Indo-Pacific as the most dynamic region in the world, Belgium believes Europe should pay particular attention to research and development, as well as cyber security and data governance. The country is open to competition on 5G equipment but will be cautious in equipping sensitive sectors with this technology.

Recent events such as the pandemic and the accident that blocked the Suez Canal have ignited a debate in Belgium about the need for reshoring and the reindustrialisation of Europe. Given the Belgian economy’s reliance on exports, these debates will likely die down. Against this backdrop, Belgium would accept bilateral free-trade agreements with democratic states in the region, but would have serious reservations about one with China.

Bulgaria

View of the Indo-Pacific

Bulgaria’s public debate on the Indo-Pacific is limited to the work of non-governmental entities and independent scholars, often within the broader context of the EU’s approach to US-China tensions. As a result, Sofia would welcome a strategy for joint European engagement with the region – which it regards as stretching from the east coast of Africa to the west coast of the Americas – based on economic interests, regional threats to the EU’s strategic interests, and environmental considerations.

EU Indo-Pacific strategy

Bulgaria regards the EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy as providing both opportunities for Europe, as an anti-China strategic tool, and as a means to manage the transatlantic alliance. Sofia believes that it is relatively important to strengthen ties with democratic countries in the region, and would welcome greater engagement with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and its member states – especially against the backdrop of EU-ASEAN negotiations on a free-trade agreement. Bulgaria sees the United Kingdom, China, and Japan as the EU’s key partners in the region.

European security

Bulgaria would welcome an EU security role in the Indo-Pacific only if it was counterbalanced by an equal effort at a cooperation dimension. Sofia wants to avoid criticism for the potentially antagonistic nature of the strategy, particularly in relation to Chinese interests in the region. That said, Sofia would welcome an all-encompassing approach to security, including humanitarian assistance and disaster-support capabilities if the strategy covered maritime security. Should this be the case, marine sustainability in areas such as the management of fisheries would be of marginal importance to Bulgaria – which would be unlikely to initiate its own plans on the issue but might support those of the EU.

Economic development

Bulgarians are actively discussing ways to improve domestic connectivity infrastructure, not in relation to the Indo-Pacific, but in an effort to boost economic activity in the Balkans. They have a significant interest in energy infrastructure diversification, as well as the digital connectivity agenda in light of Bulgaria’s membership of the Clean Network Initiative and 5G rollout. Sofia views connectivity primarily in terms of commerce and, accordingly, the EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy as a key element of market access and development policy. Bulgaria still lacks a discussion of the implementation of multilateral standards for quality infrastructure investments which would need to be based on the mobilisation of a combination of sources, including bilateral funding with relevant countries in the region, involvement of the European Investment Bank, and multilateral donors. Bulgaria’s priorities for the EU include transport, digital infrastructure, data governance, cyber security, and 5G partnerships. The country hopes to boost the EU’s economic and security interests in the Indo-Pacific while offering needs-based development opportunities to countries in region – in line with the bloc’s traditional emphasis on economic rather than military power. Sofia has closely followed the European debate on the need for diversification and reshoring, hoping to attract foreign direct investment. In this, Bulgaria would not be keen on a regional free-trade agreement – especially one that adopted a broad definition of the Indo-Pacific.

Croatia

View of the Indo-Pacific

In Croatia, the domestic conversation about the Indo-Pacific is led by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but the agenda for a joint European approach to the region is not currently regarded as particularly important. On the question of a geographic definition of Indo-Pacific, Croatia aligns with the Council’s formulation, which sees the Indo-Pacific as stretching from the east coast of Africa to the Pacific islands. Zagreb maintains that the criteria that the EU should use to construct an operational definition of the Indo-Pacific should be EU economic interests as well as economic coercion by systemic rivals.

EU Indo-Pacific strategy

Zagreb understands the Indo-Pacific strategy as both an opportunity for Europe and an anti-China strategic tool; and it sees in the strategy an alignment with the United States. As a result, in establishing regional partnerships, Croatia would give priority to pursuing relations with traditional partners such as the US, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Japan. As one of the largest, and most populous and influential, countries in the world, as well as Beijing’s rival in the region, cooperation with India would also be welcome. Further partners to be considered would be the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Indonesia, the Pacific islands, and Vietnam.

European security

Croatia supports the strengthening of the EU’s defence and security cooperation, including in the Indo-Pacific, where it believes the EU should invest in the domains of cyber security, counterterrorism, crisis management and conflict mediation. Should the strategy entail a maritime security component, then Zagreb would be willing to support it through the enhancement of humanitarian assistance and disaster-relief capabilities. Croatia maintains that all future strategic planning should include a sustainability component, but, as of yet, it lacks a discussion about how to achieve it, as well as with regards to the management of fisheries, which Zagreb would be happy to support by advocating for the adoption and maintenance of rules and norms via diplomatic channels.

Economic development

Conversation about connectivity remains relevant domestically, as Croatia is currently working to address its own internal issues on connectivity infrastructure, but no major discussion is taking place regarding the Indo-Pacific region per se. Moreover, while limited, discussion about the implementation of multilateral standards is concerned with the Three Seas Initiative, with the strategy being largely understood as a key to market access and part of a development policy. In 2019, Croatia’s prime minister, Andrej Plenkovic, said: “Better connectivity implies a more secure and high-quality data infrastructure, through the establishment of a functional digital single market and the reduction of the digital divide between better and less developed regions, and the creation of conditions for a secure transition to 5G networks.” As concerns where funding should come from, Croatia is yet to define a position. However, it maintains that the criterion for prioritising should be based on the EU’s economic interests. The covid-19 pandemic and the Suez Canal Ever Given incident have sparked a discussion about the reshoring and diversification of supply chains, which are yet to be given final direction in policymaking terms. That being said, Croatia would support the establishment of new bilateral free-trade agreements in the region and would likely also support the ratification of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China. In this effort, Croatia would consider Australia and New Zealand as key partners in the region on the grounds of existing diaspora links.

Cyprus

View of the Indo-Pacific

In Cyprus, discussions about the Indo-Pacific are led by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which sees the possibility of an EU approach to the region as moderately relevant for its defence and foreign policy goals. The country understands the Indo-Pacific as a geographic entity ranging from the east coast of Africa to the west coast of the Americas. In terms of operationalising the strategy, EU economic interests, regional threats to EU strategic interests, and environmental considerations are all variables that Nicosia would like to see considered.

EU Indo-Pacific strategy

Cyprus sees the Indo-Pacific as a field of opportunity for Europe. As such, the adoption of a joint EU strategy would be understood as an assertion of European strategic autonomy. Because Cyprus views the democratic character of potential partners as very important, it maintains that Europe’s main partners in the region should be Japan, South Korea, and Australia. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Asia Europe Meeting (ASEM) should also be involved.

European security

As a country in the eastern Mediterranean with close proximity to conflict areas, Cyprus pays close attention to the security dimension of EU foreign policy. As an extension of this position, Nicosia would embrace a security-orientated EU strategy in the domains of maritime and cyber, counterterrorism, crisis management and conflict mediation. It would support these by contributing to freedom of navigation operations, enhancing humanitarian assistance and disaster-relief capabilities, and funding EU programmes. Being so closely reliant on maritime activities for its economic resilience, Cyprus regards marine sustainability as a priority, and attributes some importance to the management of fisheries: it is already a member of the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean and would gladly support similar formats in the Indo-Pacific.

Economic development

Discussion about connectivity is currently at rudimentary level, and it has looked mainly inward as Cyprus hopes to be able to benefit from the forthcoming EU strategy in terms of creating and improving connectivity infrastructure for 5G that would attract more investment. Moreover, there is discussion about implementing multilateral standards for quality infrastructure investment, not limited only to the G20 Principles on Quality Infrastructure Investment, but willing to explore different opportunities to attract quality infrastructure investment. Cyprus sees improved connectivity as an opportunity to attract further investment to the country; in this sense, it regards this as crucial part of development policy. As concerns the financing of infrastructure under the rubric of a future EU Indo-Pacific strategy, Cyprus would encourage the mobilisation of capital from international donors rather than rely on EU funding alone. In this sense, Cyprus maintains that the driving force behind an EU connectivity agenda should be economic interest, with the establishment of digital infrastructure as the main priority. Discussion of deglobalisation has largely been fomented by ELAM, a Eurosceptic party critical of EU immigration policies, but the debate does not touch on the issue of economic interdependencies with other countries. The debate about the need for diversification and reshoring of supply is still at an embryonic stage, and is mainly concerned with meeting the Sustainable Development Goals to provide more opportunities to developing nations. Cyprus would support the establishment of individual bilateral free-trade agreements, including one with China. The partners that Cyprus would wish to see include are primarily the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the United States, and China. Lastly, in the digital domain, Cyprus would primarily prioritise research and development cooperation, considerations on the future of work and labour, and cyber security.

Czech Republic

View of the Indo-Pacific

In the Czech Republic, discussion of the Indo-Pacific is led by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which regards an EU approach to the region as imperative for its foreign policy and defence goals. For Prague, the geographic delimitation of the Indo-Pacific ranges from the east coast of Africa to the west coast of the Americas while the strategy itself should be operationalised through an all-encompassing package. The criteria for deciding how to assemble this package should include EU economic interests and regional threats to EU strategic interests, economic coercion from systemic rivals, and climate change and environmental considerations, but also sustainable development, human rights, ‘soft’ security (non-military security threats), and connectivity.

EU Indo-Pacific strategy

Prague understands the Indo-Pacific as both a field of opportunity for Europe and a vehicle for dealing with China. As such, the EU Indo-Pacific strategy would represent an assertion of strategic autonomy. Key partners in the region would be the following (in order of importance): India, the United States, South Korea, and Japan. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Canada, and New Zealand are other actors that could be key partners in the region. China, on the other hand, is not seen as a like-minded partner, but rather a player that – in certain domains – should be monitored further.

European security

Prague would be pleased to have a security component adopted as part of the strategy, and it would see this as complementary to more traditional EU priorities such as trade and sustainability. Aside from maritime security, counterterrorism, and crisis management and conflict mediation, the Czech Republic would encourage investment in cyber and 5G network security, and tackling hybrid threats including disinformation, to work in cooperation with like-minded organisations such as NATO. As concerns the maritime security pillar of the strategy, Prague would be ready to provide its support through the recalibration of arms exports, the enhancement of humanitarian assistance, and disaster-relief capabilities. In the maritime domain, the Czech Republic would prioritise activities focused on maritime sustainability, particularly in the framework of compliance with international law, the ensuring of security and trade routes including the suppression of piracy, and the monitoring of China’s activities. In this sense, fisheries management would not play a central role in Prague’s priorities for the region.

Economic development

There is no real discussion about connectivity infrastructure for the moment, although the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is planning on starting up this discussion within the year. So far, connectivity has featured in discourse only through ad-hoc consultations with both the ministries of trade and transport, in the framework of connectivity partnerships with Japan and India. Consequently, there is no real discussion about the implementation of multilateral standards for quality infrastructure investment, but is likely that Prague would follow the G20 Principles on Quality Infrastructure Investment. Connectivity is understood primarily by Prague not much as a tool for coercion, but rather as an instrument of influence. Other aspects of connectivity, in order of ranking, are connectivity as part of a development policy and a key to market access. Other potential areas of cooperation through the framework of connectivity would be concerned with aspects such as energy, transport, digital, and research and development; moreover, Prague would also seek cooperation in space-related activities, which is particularly relevant as the EU Agency for the Space Programme is based in Prague. On how to source capital to fund parts of the strategy’s activities, Prague would regard the mobilisation of a combination of sources of capital as the best option, including the use of private funds. All in all, the ultimate aim of connectivity projects should be driven by economic interest. Prague supports a liberal approach towards trade policy, which encompasses increased efforts for a further diversification of trade flows, which the government sees as a valuable tool to secure opportunities for Czech companies, jobs, and the economic growth. The government has mixed feelings towards the reshoring of supply chains: on the one hand, it fears that it might move low added value production to cheaper countries; on the other, in light of the covid-19 crisis, it is aware of the liability of supply chains.

Prague would be in favour of negotiating bilateral free-trade agreements (FTAs) in the region rather than an all-encompassing one, which would be difficult to conclude. On China, the government would first want to see the implementation of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, which is equipped with a component on the protection of investment. Viable partners for FTAs consideration could be South Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam, while in general key partners in the region would be Japan, Australia, and New Zealand.

In the technological sphere, the Czech Republic would prioritise cyber security, data governance, and 5G partnerships. Moreover, it would like to see the implementation of human rights included in the context of technology (such as personal data protection), cross-border data flows, and open trade.

Denmark

View of the Indo-Pacific

Discussion of the Indo-Pacific is led by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which regards the region as crucial for its defence and foreign policy goals. Denmark’s geographic understanding of the Indo-Pacific defines the region as stretching from the east coast of Africa to the islands of the Pacific. The government maintains that the future strategy should be driven by EU economic interests and EU strategic interests.

EU Indo-Pacific strategy

Denmark understands the Indo-Pacific as a field of opportunity in which the implementation of an EU strategy would create an opportunity for assertiveness as well as a way to support the transatlantic alliance. In this endeavour, Denmark would like to see the establishment of partnerships with relevant players in the field, such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), India, Japan, Indonesia, and Singapore.

European security

The security dimension of the Indo-Pacific strategy would be important for Denmark – particularly in the domain of maritime security, cyber security, and counterterrorism; but it is not a priority. It is too soon for Copenhagen to establish how it could contribute to the maritime security aspect of the strategy, because of the existence of the Danish national opt-out, which prevents Copenhagen from participating in all EU Common Security and Defence Policy activities that have defence implications. Neither marine sustainability activities nor fishery management in the Indo-Pacific are particularly important for Denmark.

Economic development

While there is no wider discussion about connectivity in the Danish public debate, the issue has become increasingly important for the Danish government, especially in international-focused ministries. Moreover, a discussion is taking place about the need to implement multilateral standards to ensure the quality of infrastructure investments. The government believes this should be driven by the G20 Principles on Quality Infrastructure Investment, especially in the context of ensuring that relevant players, such as China, uphold them. Some degree of government funding has already been allocated specifically to deal with connectivity, but Denmark maintains that connectivity projects in the Indo-Pacific region can only be successful if they are based on a broad range of financing. As concerns the connectivity priorities that the EU should pursue in the region, Denmark would prioritise digital infrastructure as the most pressing deliverable, followed by energy and climate change, and transport infrastructure. Ultimately, the main drivers for determining the priority of connectivity projects should be strategic interests and geopolitical considerations. Discussions about the diversification and reshoring of supply chains are taking place in Denmark, and are concerned mainly with digital infrastructure. More broadly, questions about deglobalisation in the country are driven by regionalisation as a potential solution to address some of the weaknesses of globalisation. Denmark is very supportive of bilateral free-trade agreements, and would be happy for the EU to conclude one even with China. Although unrealistic, Denmark would support the extension of such an agreement to the broader region. In establishing cooperation with regional players, Denmark would prioritise partnerships with Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) countries India and Indonesia, and would consider Singapore to be particularly important. Concerning the tech dimension, Copenhagen would prioritise the establishment of projects concerning research and development, the responsible use of AI, and cyber security.

Estonia

View of the Indo-Pacific

Formally, the Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs is responsible for the development of ties in the Indo-Pacific, but the role of the ministry has been modest in the promotion of discussion concerning the region in public debate. Estonia maintains that the criterion on which to base the activities of the new Indo-Pacific strategy – understood as spanning from the east coast of Africa to the west coast of the Americas – should be the European Union’s economic interest.

EU Indo-Pacific strategy

Estonia understands the Indo-Pacific as geographic region that could translate into a field of opportunity for Europe, while it sees the strategy itself as a way of managing the transatlantic alliance. For Tallinn, the democratic character of potential partners is highly relevant, and is reflected by its choice of preferred partners in the region: the United States and India.

European security

Estonia considers the security component of the Indo-Pacific strategy to be of primary importance, and it maintains that there should be more unity among allies, both within the EU and across the Atlantic. In particular, Estonia would regard it as imperative for the EU and US Indo-Pacific strategies to be complementary, to ensure the two do not work against each other in the region. The domains in which Tallinn would like to see more EU investment are maritime, cyber, and environmental security. Against this backdrop, should the forthcoming Indo-Pacific strategy encompass a maritime security component, Estonia would be willing to support it through contributing to freedom of navigation operations, the enhancement of humanitarian assistance and disaster-relief capabilities, and funding EU programmes. As a coastal country, it would regard the sustainability of maritime activities as relatively important. It would not be particularly concerned with the question of the sustainable management of fisheries in the Indo-Pacific.

Economic development