Life in the grey zones: Reports from Europe’s breakaway regions

Locked in a shadowy life between war and peace, “grey zones” now litter the map of Eastern Europe

Edited by Sophia Pugsley and Fredrik Wesslau

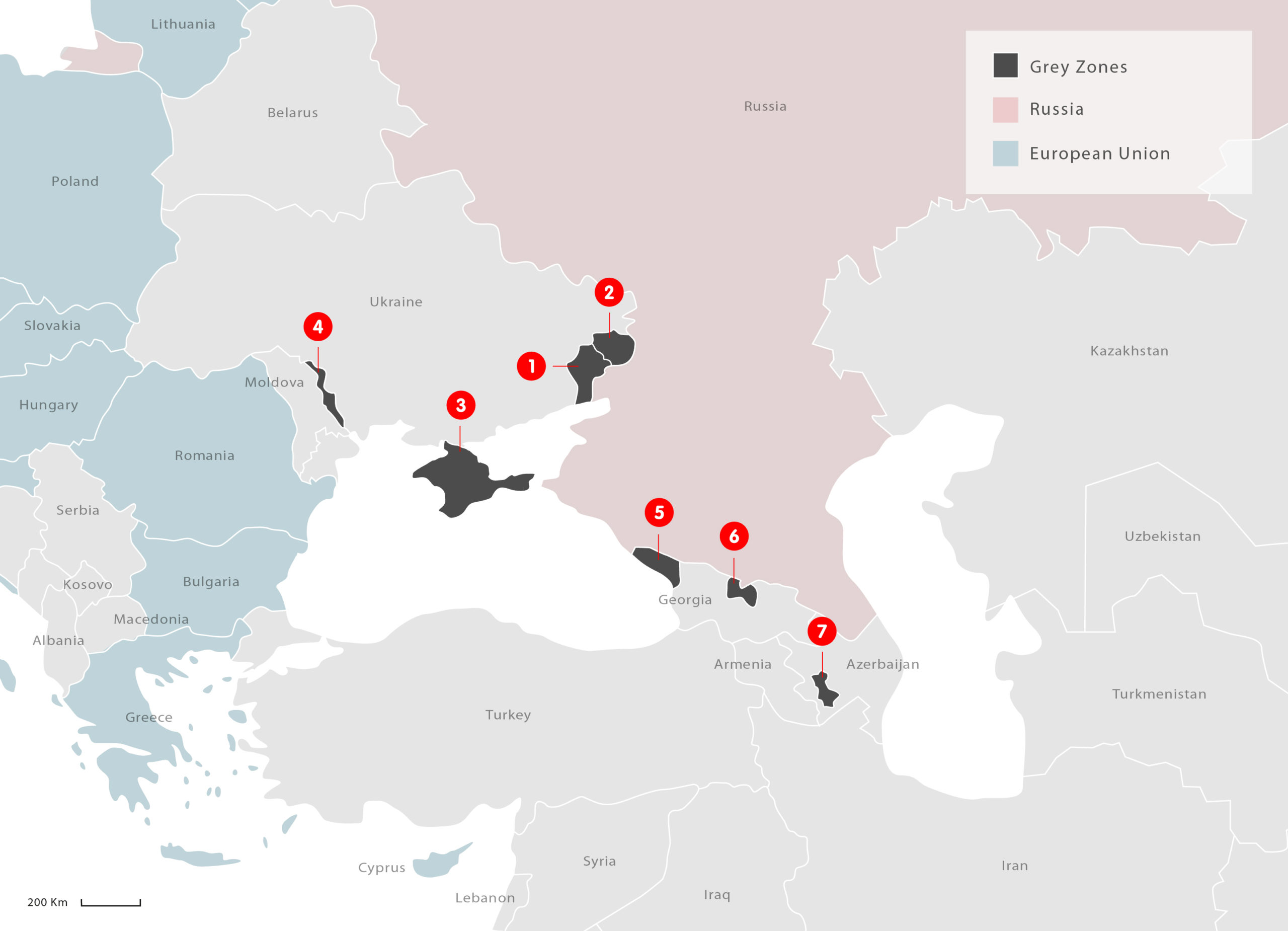

“Grey zones” now litter the map of Eastern Europe. With the Russian annexation of Crimea and military intervention in Donetsk and Luhansk, Europe has added three new unrecognised entities to an already crowded field. With these latest additions, there are today seven unrecognised entities in the eastern neighbourhood, the other four being Transnistria, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Nagorno-Karabakh.

These entities exist in limbo. They are de jure part of one country but de facto controlled by another. With the exception of Donetsk and Luhansk, they are not in a state of war exactly but neither are they in a state of peace. These places are largely cut off from the rest of the world. Their development has been effectively frozen, rule of law is weak, and militarisation is heavy. They are the grey zones on the map of Europe.

These grey zones threaten peace and stability and impede development throughout the region. Their unresolved status means that they create a continuous risk of conflict. Their uncertain status and problematic borders mean they are hotbeds of smuggling and corruption. With the possible exception of Nagorno-Karabakh, they also constitute major points of disagreement in our relations with Russia.

But what is it like to live in these places? What sort of life can you create for yourself when your “country” is born out of war, unrecognised by practically all other states, and heavily dependent on a neighbour? Most of these “countries” have demarcated their own “borders”, set up their own “governments”, and attempted to establish themselves as functioning international entities.

We asked resident journalists to write about life in their region, recounting how people have coped with war, isolation, and often corruption. Authors share personal stories from their communities about how people live and work and what their hopes and fears are for the future. In this way, we hope to give an idea of what life is like in these isolated places and at the same time provide an insight into the likely future of the three newest unrecognised entities in Ukraine.

This is the first collection of a series dealing with unrecognised entities in the eastern neighbourhood. The next installment looks at Russia’s presence and control over the entities

Donetsk

Vladimir Rafeyenko

Donetsk is not going through the best of times. It seems that these grey times – without war but without peace, not part of Russia but not part of Ukraine – will drag on for some time. Donetsk cannot be part of the Russian Federation, but Russia was able to rip it away from Ukraine, and it did so by spilling so much blood that it will take a long time for it to dry on the streets and squares of this place.

People’s lives were torn apart. For those who fled the city, leaving behind their homes, nearest and dearest, everything that made up their lives, and for those who, for various reasons, stayed here. The old way of life was destroyed. It is clear that nothing will grow on these ruins for years to come. Even those who believe in the future of unrecognised republics have less and less energy. It turns out that it is a lot easier to destroy than to create.

Luhansk

Valentin Torba

The Donbas is not only frozen, it has gone back in time. Even the misery of the 1980s or the 1990s does not compare with the depression that prevails now. Luhansk looks dark and doom-laden despite the traditional Christmas tree in the city centre and the donkey rides put on for the kids. At school, these same kids now learn that they live in the “LNR”, and not in Ukraine.

People expect the military situation to get worse. With the earth now frozen, it is easier for heavy armour to move around and there has been an increase in rebel activity since early November. All signs seem to suggest that the pressure on Kyiv won’t be ending any time soon. Every day the rebels shoot on Ukrainian military units and civilians. Every day people die.

Crimea

Lev Abalkin

It has been nearly two years since Russia annexed Crimea, and the period of transition is formally over. There has even been a nominal reshuffle of power through local elections and a law on the establishing of a free economic zone. Most Crimeans have received Russian passports and have re-registered their properties in accordance with Russian legislation. Crimea’s integration into Russia took place with unprecedented speed. The currency, the laws, school curricula, and even trade changed dramatically in the space of a few months.

However, Crimea has gone through a period of ideological prejudice and economic blockade, and a rupture in family, friendship, and business ties with the rest of Ukraine. A rupture that will take decades to mend.

R & A Bari Urcosta

For a long time it felt as though this was just a game – that the government would put a stop to all this in a week, ten days. The Russian flags and incessant patriotism, the infamous “little green men”, the prohibition of all things Ukrainian, the ban on Crimean Tatar media, the cancellation of all flights, and everything else – all this happened later. The sunny, early spring days of 2014 did not bode ill. Flowers started to bloom, just as they had done for hundreds of thousands of years, along with a course of events which over time has not only worsened the situation of the Tatar people, but also barred the way to a sustainable future.

The Tatars had no part in the so-called Crimean Spring. We supported the Ukrainian soldiers who remained blocked by Russian troops to the bitter end. We took no part in the “reunification” celebrations. Locals are well aware of this and hold it against us.

Transnistria

Karina Lungu

It’s a warm, foggy November morning in Tiraspol. The tops of the trees are scattered with autumnal leaves of reddish-yellow hue as if they have been painted by an artist with vast natural brushstrokes. These are the last few remaining trees in the city centre. Most of the old acacias and poplars planted back in Soviet times to improve Tiraspol’s notoriously bad air quality have been culled. The city’s main street has kept its Communist-era name, leaving its inhabitants with no doubt as to which way we are headed.

People in Transnistria don’t know who to blame: either themselves for being naïve enough to believe that people power alone can build a welfare state, or those in power who, besides making themselves wealthy through corrupt schemes, have not been able to deliver the promised “little Switzerland” in the past 25 years of self-declared independence. People are also confused about whether to blame Russia, which refuses to recognise the independence of this narrow strip of land along the Dniester River (as it has done for Abkhazia and South Ossetia) while the population of half a million is subjected to a smooth local propaganda machine as a panacea for all ills. The people could blame their neighbours – Moldova and Ukraine – who are constantly dreaming up new ways to make our lives even more difficult. Frankly, we are spoilt for choice when it comes to blaming others.

Abkhazia

Nadezhda Venediktova

Abkhazia is a tiny strip of land on the Black Sea coast. In Soviet times, it was an autonomous republic of Georgia and had one of the highest living standards in the union, mostly due to it being a popular tourist area. The sub-tropical climate meant that fruit could be exported at market prices, while imports from other Soviet republics were subsidised. Unlike in other Soviet territories, land in Abkhazia was never nationalised. People were allowed to live in rural areas on their farms and work in the city on government salaries. All this made us uniquely well-off in the USSR, especially those living in the major tea-growing areas.

After the fall of the Soviet Union and the Georgian-Abkhaz war in 1992-1993, Abkhazia became de facto independent from Georgia but its economy collapsed. Half the houses were destroyed, the population fell significantly, and the railway fell into disuse. The general post-Soviet malaise after the collapse of the USSR was made worse in our case by the devastation caused by the war. Any economic recovery was stalled in January 1996 when the Council of Heads of State of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) banned any official economic ties with Abkhazia. This was done to “encourage Abkhazia to take a more flexible position on the return of refugees”. Officially, these sanctions were only lifted in October 2008. So we effectively spent 12 years in isolation, even though Russia gradually softened its position in 2000. That same year, Russia began issuing passports to Abkhaz residents. Until then, we had been using the old Soviet passports, which meant that we could not travel anywhere outside Abkhazia.

South Ossetia

Maria Kachmazova

Generally speaking, economic ties with Georgia are non-existent now. So all our imports (like food and clothing) come from Russia, especially from cities like Vladikavkaz and Pyatigorsk. This is expensive, because it all has to come over a mountain road 200 kilometres long. Nevertheless, there are many shops here, mostly selling groceries; it is difficult to understand how they can all compete with each other. There are new shops opening all the time, in every suburb. The main street of Tskhinvali is lined with busy shops, pharmacies, and boutiques.

We used to have big factories here: Emalprovod, the Vibromashina textile mill, and a clothes factory. All of them, apart from the clothes factory, stopped working back in the 1990s. The buildings that haven’t crumbled are rented out to locals for use as warehouses, garages, workshops and so on. These are people who honestly pay their taxes to the state, but these taxes make up a tiny fraction of the state budget, which is almost covered 100 percent by Russian subsidies. The lucky ones get their project funded by this Russian “investment programme”; the less fortunate cannot get investment from anywhere else. Loans to small businesses are a rare and pretty murky affair.

Nagorno-Karabakh

Knar Babayan

The unrecognised Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (NKR) has been living in a state of neither peace, nor war for the past 20 years. In 1988, the Armenians of Karabakh took to the streets to demand that Karabakh be reunited with Armenia. After the declaration of independence in 1991, the Azerbaijani-Karabakh war began, and only ended in 1994. However, Karabakh’s independence has not yet been recognised by any state, not even Armenia.

A sign on the road from Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh reads: “A free and independent Artsakh welcomes you”. Artsakh is Karabakh’s historical name. The next stop on the road is the checkpoint on the border of Karabakh and Armenia where passports are checked. Foreign nationals (including ethnic Armenians who are citizens of other countries) are required to register, and then, before reaching the capital Stepanakert, are obliged to apply to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for a visa.

Some names have been changed to protect authors’ anonymity.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.