The power of perspective: Why EU membership still matters in the Western Balkans

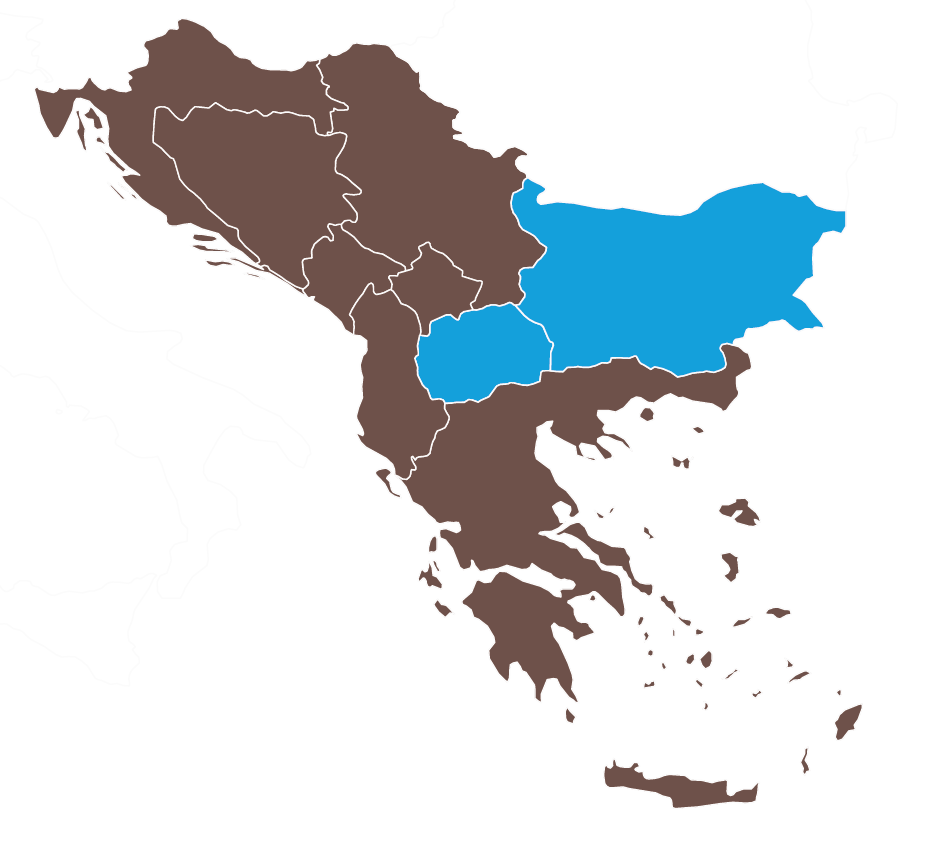

Summary

- Aspiring EU members must resolve outstanding disputes as part of the membership process. This has proved a powerful tool over the years.

- Resolving bilateral problems, including border disputes, is especially crucial in the Western Balkans, where they are numerous.

- France’s October 2019 veto of accession talks for North Macedonia and Albania has already weakened Western Balkans publics’ trust in the EU.

- Should the EU’s influence wane, nationalist leaders will exacerbate tensions with neighbouring countries. The future of North Macedonia’s Prespa Agreement with Greece is under threat, and the Serbian Orthodox Church in Kosovo and Montenegro could also prove a potential flashpoint.

- The EU should demonstrate its commitment to the Western Balkans by encouraging countries there to resolve their outstanding disputes, both to make them better candidates and to strengthen security in the region

Introduction

Good neighbourly relations have been part of the European Union’s conditionality requirements since the beginning of its enlargement to central and eastern Europe. But, lately, settling bilateral disputes in the Western Balkans has become an explicit and much emphasised precondition of further enlargements. For instance, the European Commission recently made unequivocally clear its view that: “the EU cannot and will not import bilateral disputes and the instability they can entail”.[1] And this emphasis has become especially marked since the opening of accession negotiations with Serbia in 2014, in which the EU conditioned progress on “a visible and sustainable improvement in relations with Kosovo”. In addition, the 2015 Berlin Process sought to reinvigorate ties between EU and Western Balkan countries, and it included an explicit commitment to foster regional cooperation among countries of the region. As part of that process, EU candidate and prospective candidate states specifically promised to refrain from using bilateral disputes to obstruct each other’s progress on the EU integration path, while agreeing to monitor the resolution of remaining bilateral challenges.[2]

More recently, international attention has come to rest on the Prespa Agreement between North Macedonia and Greece – the fact that it was concluded at all, and now its potential implosion after France vetoed the opening of membership talks for North Macedonia in the autumn. While the long-running dispute between Greece and North Macedonia remained unresolved for many years, just as many bilateral disputes in the region still do, leaving such problems unaddressed can still pose a real obstacle to the EU integration process for would-be members. Many other disputes lie dormant or are only semi-active.

Bilateral disputes in the Western Balkans often include wrangles over borders, many of which are a legacy of the former Yugoslavia, where delineations between the republics were not always precisely defined. EU member Croatia is, perhaps surprisingly, the country in the region with the highest number of disputed borders. And, while the territories under question are usually small, they can cause real trouble: a dispute between Slovenia and Croatia at Piran Bay held up Croatia’s EU accession process for a time. Further types of issue include property claims between Kosovo and Serbia, and Greece and Albania; and the status of the Serbian Orthodox Church, which has caused tensions in both Montenegro’s and Kosovo’s relations with Serbia. On the agenda of the Belgrade-Pristina dialogue, issues of a technical nature abound.

This policy brief maps Western Balkan countries’ unresolved bilateral problems and offers recommendations for European policymakers. It finds that, in most cases, purely practical solutions to bilateral challenges will be difficult to find without addressing disagreements of high politics. But examining the EU’s enlargement activity of the last few years also reveals that offering the perspective of membership can provide incentives for governments to seek agreements with their neighbours. Many bilateral disputes require greater and more sustained attention than they have received to date, even within the EU enlargement framework. If prospective EU member states are not to fall foul of these outstanding issues at the later stages of accession negotiations, they – and pro-enlargement partners elsewhere in Europe – should start work now to study, understand, and seek to resolve these issues.

EU influence in the Western Balkans: Strong or weak?

Since it first offered Western Balkan states the chance to join at the 2001 Thessaloniki summit, the EU has played a clear catalysing role in resolving ethnic conflicts and bilateral challenges in the region. Some brief case studies illuminate the situation.

The EU’s relationship with North Macedonia is especially instructive about how the integration process can improve stability, and how strongly EU integration can strengthen security in the region. In spring 2001 a low-intensity war broke out between the Albanian National Liberation Army, which enjoyed broad support among the Albanian population, and the security forces of the then Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM). The conflict came to an end with the Ohrid Framework Agreement (OFA), facilitated by NATO and signed in August 2001 by the two largest Macedonian and Albanian parties. In the same year, the EU opened negotiations with the FYROM government on a Stabilisation and Association Agreement. Regardless of the fact that the EU presented many requirements for FYROM to fulfil, it was clear that implementing the OFA was the most important indicator of progress from the EU’s perspective when evaluating the country’s general performance. Thus, the goal of achieving EU candidate status, which the country received in 2005, was an important motivation to implement the OFA. The OFA has generally been hailed as a success, as FYROM escaped large-scale ethnic conflict and also avoided the institutional fragmentation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which was a result of the Dayton Peace Agreement.

Despite FYROM’s relatively good record of carrying out the OFA, its Euro-Atlantic integration process became derailed for almost 10 years due to disagreements with Greece over the country’s name. Again, it was eventually the influence of the EU that got this back on track. Because of Greece, FYROM was denied the much-anticipated membership offer at the 2008 Bucharest NATO summit, which set off a wave of nationalist protests in the country. This represented a turning point for the nationalist prime minister, Nikola Gruevski, who began to pursue more open and provocative nationalist policies. The Greek veto meant that FYROM’s EU integration process and accession to NATO stalled after 2009, which coincided with growing ethnic Macedonian nationalism, gradual internal political destabilisation, and a rapid deterioration of democratic governance. But this negative trajectory came to an end in 2016 when a new government was elected that pursued a pro-EU agenda and more conciliatory policies towards Greece. This reinvigorated the EU integration process and negotiations with Greece, culminating in the signing of the Prespa Agreement between North Macedonia and Greece in 2018. As a result of this, the country received the name “North Macedonia”. Importantly, North Macedonia made not only a compromise on its name, but effectively gave a veto right over its identity to a neighbouring country – for the sake of EU accession.

The EU’s role in helping establish the Belgrade-Pristina dialogue also illustrates how the promise of EU integration can drive conflict settlement. Once Serbia’s relations with Kosovo became the most influential issue defining Serbia’s pace of EU integration, this motivated Belgrade to enter a formal dialogue in 2011. At the time, the European Commission recommended giving candidate status to Serbia, in October 2011. But the Council, under Germany’s influence, postponed the decision until spring 2012 because of violent clashes on Kosovo’s border with Serbia. The EU held Serbia accountable for the incidents and it called on Serbia to remove roadblocks on the border and to allow Kosovo to participate in regional cooperation – and these became conditions for Serbia receiving candidate status. The EU’s incentive worked: the pressure led to the signing of a number of so-called technical agreements, such as the deal reached in December 2011, between the Serbian and the Kosovo governments on Integrated Border Management. Under this the two governments undertook to set up joint border posts to be managed by the two sides with EULEX’s assistance. Moreover, in February 2012, Belgrade and Pristina agreed on Kosovo’s representation in regional forums and institutions. Rewarding its compliant behaviour, the EU assigned candidacy to Serbia in March 2012.

Finally, the EU’s positive influence was visible once more when Montenegro and Kosovo signed a border demarcation agreement in 2018, resolving the two countries’ outstanding bilateral issues. This settlement would have been difficult to conclude without pressure from the EU, which pushed back in the face of fierce resistance from Kosovo opposition parties claiming the deal would wrongly hand over some 8,000 hectares of territory to Montenegro. In such situations, the EU can exert a moderating effect on nationalist sentiments directed against neighbours and help towards the resolution of disputes.

Thus the EU integration perspective has had demonstrably clear benefits for security in the Western Balkans. However, the limits of its influence have also become evident. For instance, many of the Belgrade-Pristina agreements remain unimplemented or only partially implemented, while the process itself broke down more than a year ago.

More broadly, the EU’s positive influence can take effect only if countries’ governments are actually interested in EU accession. This may appear self-evident, but its implications can be profound: part of the reason the EU has been unable to address Bosnia-Herzegovina’s longstanding institutional deadlock has been Bosnian political elites’ weak interest in joining the EU. This has made them only rarely willing to comply with EU demands.

In this regard, it is possible to describe the Western Balkan countries according to the extent of the leverage the EU enjoys over them on tackling unresolved issues with neighbouring states. Bosnia and Kosovo are not yet even EU candidates and are distant from EU membership. Kosovo is still more sensitive to EU conditionality than Bosnia, though, as it badly needs international recognition and support, which gives the EU potential leverage.

Albania and North Macedonia are EU candidates that are not yet in the process of negotiating membership. However, there is a difference between these two countries as well, in that Albania has less support among EU member states than North Macedonia. While North Macedonia would have received support from all EU members apart from France at the October European Council, several states would have blocked the opening of accession talks with Albania regardless. Because of this general scepticism towards Albania, the Albanian government has been less inclined to address its outstanding problems with Greece than North Macedonia has.

Finally, Montenegro and Serbia are candidate states currently negotiating their EU membership. Accordingly, these two countries retain strong incentives to comply with EU demands, including the settlement of conflicts with neighbours.

That said, a new development that may have weakened the EU’s leverage in the region – even among countries that would like to join – is the EU’s slackening commitment to further enlargement, as most obviously illustrated by France’s October 2019 veto. The French move increased doubt among Western Balkan countries about their future prospects, and effectively pulled the brake on EU enlargement policy. France is now calling for a fundamental review of enlargement policy, meaning the Balkan integration process is likely to slow. Public expectations in the region are already accordingly low: 66 percent of people in Serbia believe they will not join the EU until 2030, if at all. In terms of resolving bilateral problems throughout the region, the falling away of this framework and the weakening of expectations that once sustained it will have a negative impact.

Bilateral disputes in profile

North Macedonia and Greece

Officially, since the signing of the Prespa Agreement there are no unresolved issues between North Macedonia and Greece.[3] But the agreement’s content leaves many technical details to be settled, the resolution of which depends to a large extent on the continued existence of political good will on both sides. And, of course, the impact of the French veto on North Macedonia’s EU membership prospects could threaten the future of the agreement. The agreement came into force in February 2019, but was always going to involve a long process of implementing its provisions, closely scrutinised by Greece.

Officially, since the signing of the Prespa Agreement there are no unresolved issues between North Macedonia and Greece.[3] But the agreement’s content leaves many technical details to be settled, the resolution of which depends to a large extent on the continued existence of political good will on both sides. And, of course, the impact of the French veto on North Macedonia’s EU membership prospects could threaten the future of the agreement. The agreement came into force in February 2019, but was always going to involve a long process of implementing its provisions, closely scrutinised by Greece.

Greece wants to link the execution of the Prespa Agreement to North Macedonia’s EU accession process explicitly, while the EU refuses to officially make this connection.[4] However, in practice Greece, like any EU member state, has the power to veto the opening and closing of negotiating chapters with North Macedonia.

The implementation of the agreement calls for many practical and costly changes in North Macedonia, such as updating the country’s name in the names of public institutions, businesses, trademarks, brands, official documents including passports, ID cards, driver’s licences; and licence plates from MK to NMK; issuing new money; and modifying school curriculums and textbooks by removing revisionist references (references which might imply a claim on Greek Macedonia). Article 8 of the agreement stipulates that the parties should apply corrective measures if they use symbols that the other regards as “constituting part of its history and cultural patrimony”. Although both sides have the right to protest in such cases, the Greek side has the leverage as an EU member state with veto power to press for its own interpretation.

In order to facilitate the process of seeking agreement on cultural symbols and historical interpretations, the two countries established a Joint Inter-Disciplinary Committee of Experts on historical, archaeological, and the educational issues. It has held four meetings so far. Revising history and geography textbooks will certainly be a long and difficult process, as the presentation of several historical events will have to be modified, such as that of the Greek civil war or the Balkan wars. North Macedonia also has to “review the status of monuments, public buildings and infrastructures” and make corrections so that these do not “refer in any way to ancient Hellenic history and civilisation”.[5]

Another laborious aspect of implementing the agreement will be agreeing on commercial names, labels, trademarks, and brand names, which will probably involve changing ISO codes. Such details will be worked out by a bilateral expert committee over the next three years. This aspect might be especially delicate. However, here the European Commission can involve itself constructively by providing advice, as it will participate in the work of this committee.[6]

Besides giving a veto right to Greece over the definition of the term “Macedonian” and over Macedonian national symbols, another potentially painful part of the agreement (Article 3) is that it practically forbids North Macedonia to support the rights of the Macedonian minority living in Greece, whose existence is not officially recognised by Greece.

North Macedonia’s bilateral relations with Greece have lagged behind in fundamental areas because of the long political stalemate, including normalising relations by concluding basic agreements such as the treaty on avoiding double taxation and the agreement on cross-border cooperation. These could improve relations in practical ways.[7] The two countries are now beginning to address these shortcomings, which is important given that Greece is already, despite the stunted nature of the relationship, the third biggest investor in North Macedonia.

Nor are all the relevant political forces in the two countries equally committed to the Agreement’s implementation. The nationalist VMRO DPMNE party in North Macedonia fiercely attacked the Agreement from opposition before it was signed, while more lately has adopted a more ambiguous stance. Hristijan Mickoski, the party’s president, still does not use the new name of the country, although he has on several occasions communicated to North Macedonia’s international partners that he regards the name issue as closed. The Greek government is now led by the centre-right New Democracy party, which was known for its strong opposition to the Prespa Agreement in 2018. However, it has since toned down its opposition and claims that it is seeking the agreement’s full implementation.

In North Macedonia, the Social Democrat-led government that negotiated the agreement resigned in response to the October European Council meeting where membership talks with North Macedonia and Albania were blocked. New elections will now take place in April 2020, which could lead to the VMRO DPMNE party coming to power. This will probably not bring the agreement to an end, but it could slow its implementation.

However, even if the new government does commit itself to the Prespa Agreement, the October European Council decision means that implementation is likely to suffer regardless, as the content of the agreement is linked to the EU negotiation process. According to the Prespa Agreement, as more chapters are opened, the agreement’s provisions are to be carried out in more areas. Changing North Macedonian official documents and materials should, according to the agreement, start “at the opening of each EU negotiation chapter in the relevant field, and shall be finalised within five years thereof”. Importantly, North Macedonia side agreed to all these concessions in exchange for the opening of accession negotiations, which was the most important promise with which it could ‘sell’ the agreement to its public. Therefore, postponing the start of the negotiations is a dangerous game as it weakens pro-EU political forces in North Macedonia while also delays the implementation of the agreement.[8]

North Macedonia and Bulgaria

Like with Greece, North Macedonia’s relations with Bulgaria contain threats to its EU integration process. Similar to the Greeks, the Bulgarian government and the public at large have questioned Macedonian identity, particularly the existence of a separate nationality and language. On this basis they contest the historical heritage, monuments, and symbols of North Macedonia.[9] For example, the Bulgarian government has stated that it would prefer the name “the Republic of North Macedonia” as opposed to “North Macedonia”, as the latter also refers to a historical region, part of which is in today’s Bulgaria (called Pirin Macedonia). NATO dealt with this problem by adopting a statement at its session on 10 July 2019 clarifying that the term “North Macedonia” featuring in NATO documents refers exclusively to “the Republic of North Macedonia”. However, while this issue was resolved in NATO, it may still cause turmoil in other international organisations.

Like with Greece, North Macedonia’s relations with Bulgaria contain threats to its EU integration process. Similar to the Greeks, the Bulgarian government and the public at large have questioned Macedonian identity, particularly the existence of a separate nationality and language. On this basis they contest the historical heritage, monuments, and symbols of North Macedonia.[9] For example, the Bulgarian government has stated that it would prefer the name “the Republic of North Macedonia” as opposed to “North Macedonia”, as the latter also refers to a historical region, part of which is in today’s Bulgaria (called Pirin Macedonia). NATO dealt with this problem by adopting a statement at its session on 10 July 2019 clarifying that the term “North Macedonia” featuring in NATO documents refers exclusively to “the Republic of North Macedonia”. However, while this issue was resolved in NATO, it may still cause turmoil in other international organisations.

Bulgaria has also asked the European Commission not to call the language “Macedonian”, as envisaged by the Prespa Agreement, but the “official language” of the Republic of North Macedonia.[10] In 2017, North Macedonia signed a friendship treaty with Bulgaria, which also uses the term “official language” rather than “Macedonian”. Currently, the EU uses both “Macedonian language” and “official language”, while the United Nations uses the term “Macedonian language”.

The two countries have set up several intergovernmental working groups on specific bilateral issues, such as on trade, economic cooperation, and the content of history textbooks.[11] Since they signed the friendship treaty, bilateral relations have developed smoothly, and Bulgaria was supportive of North Macedonia’s EU integration during its EU presidency in 2018. More recently, somewhat unexpectedly, the Bulgarian government announced that it will condition supporting accession talks with North Macedonia on reaching an agreement about key historical figures claimed by both sides. For example, both countries commemorate the anniversary of the 1903 Ilinden uprising against the Ottomans, yet both claim its leading figures as their own co-nationals. The two governments have set up a joint commission of history and education whose role is to clarify such historical disagreements. By linking this issue to North Macedonia’s EU negotiations, the Bulgarian government raised the pressure on the North Macedonian side, and on the historical commission to work out a solution.

The Bulgarian government did not block the opening of North Macedonia’s membership negotiations with the EU during the October European Council this year. But, shortly before the summit, Sofia presented 20 demands – related to historical issues and the Macedonian minority in Bulgaria – that it wants Skopje to fulfil before the first intergovernmental conference officially marking the start of EU accession talks. This suggests that, once the negotiation process eventually begins, Bulgaria might well move to obstruct progress in some chapters.

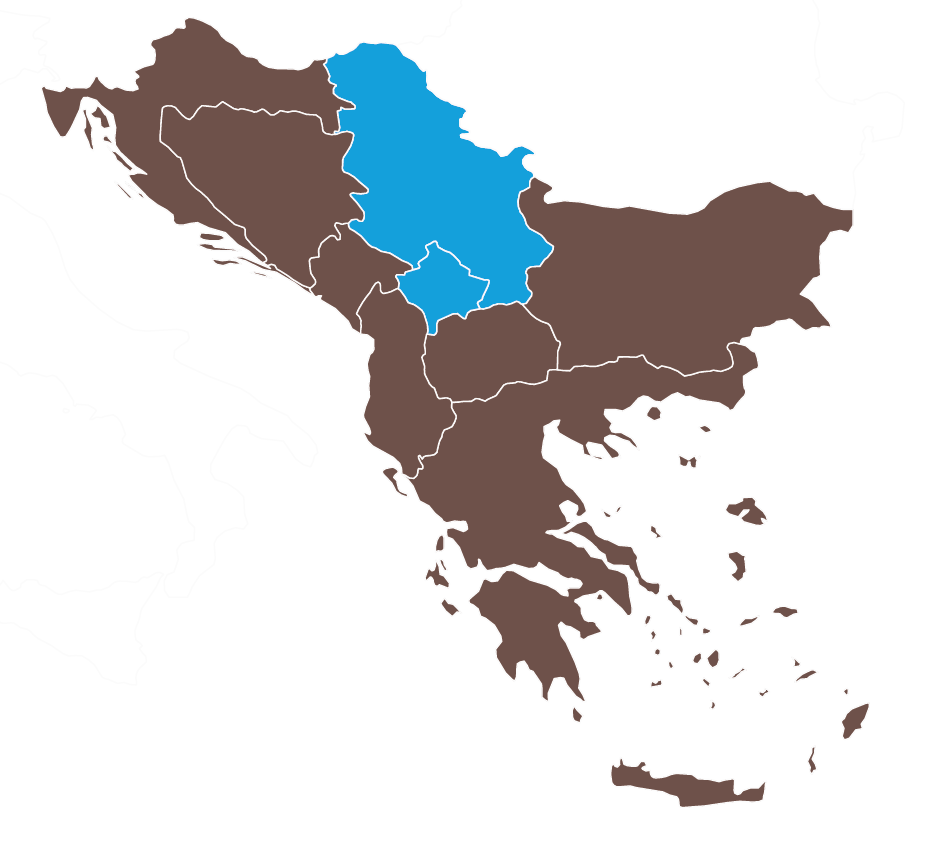

Serbia and Kosovo

Of all the problematic bilateral relationships in the Balkans, the Serbia-Kosovo relationship is probably the hardest to solve. While there are many technical problems that need to be addressed by the two sides, the resolution of these seemingly practical issues hinges on the ability of the parties to come to some consensus about high politics. Belgrade’s obstruction of the implementation of many of the technical agreements comes down to its non-recognition of Kosovo’s state sovereignty, while Pristina’s reluctance to fulfil some of its pledges is motivated by the fear that Serbia wants to undermine its functioning as an independent state.

Of all the problematic bilateral relationships in the Balkans, the Serbia-Kosovo relationship is probably the hardest to solve. While there are many technical problems that need to be addressed by the two sides, the resolution of these seemingly practical issues hinges on the ability of the parties to come to some consensus about high politics. Belgrade’s obstruction of the implementation of many of the technical agreements comes down to its non-recognition of Kosovo’s state sovereignty, while Pristina’s reluctance to fulfil some of its pledges is motivated by the fear that Serbia wants to undermine its functioning as an independent state.

In 2011, Serbia and Kosovo began an EU-facilitated dialogue, which ran for seven years until 2018. The dialogue covered a wide range of issues, including Kosovo’s representation in regional forums and institutions, freedom of movement, border management, the judiciary, the police, telecommunications, air traffic, customs, land registries, civil records, harmonisation of diplomas, registration plates and electricity. It led to the two sides concluding a number of technical agreements. In addition, they signed two high-level political agreements in 2013 and 2015, which, besides enabling some of these technical issues to move forward, also sought to address the status of the North Kosovo region and provided for the creation of the Association of Serb Municipalities. These advances demonstrated the link between ‘high politics’ and on-the-ground progress that is so vital in this relationship.

Since then, many of these agreements have remained unimplemented or only partially implemented. In addition, the Kosovo government became increasing frustrated by Serbia obstructing many of the agreements (covered in more detail below), and also by Serbia’s campaign to obstruct the international recognition of Kosovo. As a result, the whole process came to halt in November 2018 when the Kosovo government introduced a 100 percent import tax on Serbian and Bosnian goods, which also undermined Kosovo’s Central European Free Trade Agreement obligations. Ever since, it has been reluctant to lift the tax despite pressure from Western powers, including the EU and the United States. An EU-backed Western Balkans summit held in Berlin in April 2019 reached no specific conclusions about continuing the dialogue in the context of the Berlin Process. A meeting that was planned for July in Paris was cancelled, and many regard the dialogue as practically dead. Certainly, it is in a difficult deadlock, with no easy way out seems to be in sight.

Each side maintains that it needs to receive something in exchange for a compromise, and each is dissatisfied with the process as a whole. Kosovo demands full recognition from Serbia in exchange for the continuation of the dialogue: after the breakdown of the dialogue, the Kosovo government adopted the policy of “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed”, meaning that recognition has now become a precondition of everything else.[12] But recognition remains unacceptable to the Serbian government.

The EU appears to lack ideas for putting pressure on Kosovo. Despite a recommendation to proceed with visa liberalisation issued by the European Commission, which concluded that Kosovo had met the required benchmarks, member states remain reluctant to open their borders. They are divided over whether Kosovo indeed fulfilled the visa liberalisation conditionality. But all this has undermined the credibility of the EU’s conditionality towards Kosovo and sends a message to the Kosovo public that the EU has little to offer, especially given that EU membership is already a very distant and uncertain prospect. The EU now has very little ability to persuade the Kosovo government to take steps to resolve bilateral disputes with Serbia.

The 100 percent import duty placed on Serbian goods is a clear example of a technical instrument being used to apply political pressure. Pristina appears to have chosen such a brutal tool for the damage it can do to Serbian interests: Serbia is among the biggest exporters of consumer goods to Kosovo. In contrast to Serbia, Kosovo does not have many tools at its disposal. On the tariffs specifically, it is worth mentioning that the Kosovo government adopted two decisions in October 2018: a decision according to which products exported to Kosovo must show on their label “the Republic of Kosovo” as the destination, as well as the 100 percent tax. For Serbia, the label is as serious a problem as the tax, but the latter gives it a good excuse for not selling goods to Kosovo. Once the tariff is eventually removed, this latent problem will become more immediately apparent, as the Serbian authorities will not approve the use of the label “Republic of Kosovo”. That said, it could find ways to deal with this, such as through ‘smart’ solutions like relabelling products at the border. [13]

For Serbia, the most important gain from the bilateral dialogue while it was in place was the agreement on setting up the Association of Serbian Municipalities (ASM), secured in the 2013 Brussels Agreement. The ASM was to be formed as the community of municipalities in Kosovo that have an ethnic Serb majority, and it was to receive autonomous prerogatives in many areas, especially in the domains of education, healthcare, urban and rural planning, and the economy. Since the Brussels Agreement left many issues open, in 2015 the two parties signed another package of agreements, which provided more detail. But the creation of the ASM has been delayed, as it lacks support in the Kosovo assembly, and has caused much controversy among Kosovar political parties. At the moment it is very unlikely that it will ever be created.

Moreover, in 2016 Kosovo’s constitutional court found some parts of the 2013 agreement to violate Kosovo’s constitution. It deemed unconstitutional the proposal that competencies of the participating municipalities in the areas named be taken over by the ASM, and it concluded that that municipalities should retain responsibility for carrying out municipal competencies. The court also called for clarification of the term “full overview”, which was the term used in the agreement to describe the competencies of the ASM. Whether the ASM should have executive competencies was left unclear in the 2013 and 2015 agreements, which helped generate heated disputes between Kosovo and Serbia. Opposition parties and the majority of the Kosovo public have made their opposition to the ASM clear, fearing it would create a ‘Republika Srpska’ in Kosovo, destroying Kosovo’s integrity: the radical Vetëvendosje staged violent street protests against the agreement and for a time it periodically released teargas in parliament.

It is already a widespread view in Kosovo that the 2007 Ahtisaari Plan was too much of a compromise in the way it granted enhanced autonomy for municipalities inhabited by minorities. The Ahtisaari Plan is the basis of the Kosovo constitution and it accorded de facto veto powers to Serbian members of the Kosovo parliament over so-called “essential issues” for minorities; constitutional changes; and Kosovo’s membership of international organisations. These veto rights exist in the form of requiring double-majority support in these three areas, and in practice this means at least two-thirds of the 100 Kosovar MPs and the 20 minority representatives. According to some Kosovo Albanian politicians, the ASM cannot be created as long as Kosovo Serbs have these veto powers.[14] A solution to this deadlock could be to retain the veto power of the Serbian minority over legislation concerning essential issues for minorities, such as language and municipalities, but not over constitutional matters. The ASM could therefore go back on the agenda if the whole constitutional framework regulating minority rights was changed and renegotiated.[15]

The linking of issues is common practice by both sides, which ensures that problems of “high politics” and so-called technical issues are not easy to separate. The second agreement on the ASM, signed in August 2015, was part of a package deal that included other topics, such as energy, telecommunications, and the Mitrovica Bridge. Because of this, the Kosovo government has been able to make implementation of the ASM conditional on implementing the energy agreement. By contrast, Serbia is obstructing the implementation of the energy agreement, preventing Kosovo from connecting to European energy networks. It is also blocking the deal on the bridge in response to Pristina’s failure to create the ASM. Serbia does not want to compromise on the ASM, as it was the reason why it agreed to dismantle parallel structures that previously existed in majority-Serb North Kosovo as part of the Brussels Agreement: after 1999 Serbia sustained the operation of its institutions in Serb-majority areas in Kosovo, including local government, health and educational institutions, and security apparatuses. These functioned alongside the UN’s and Kosovo’s institutions.

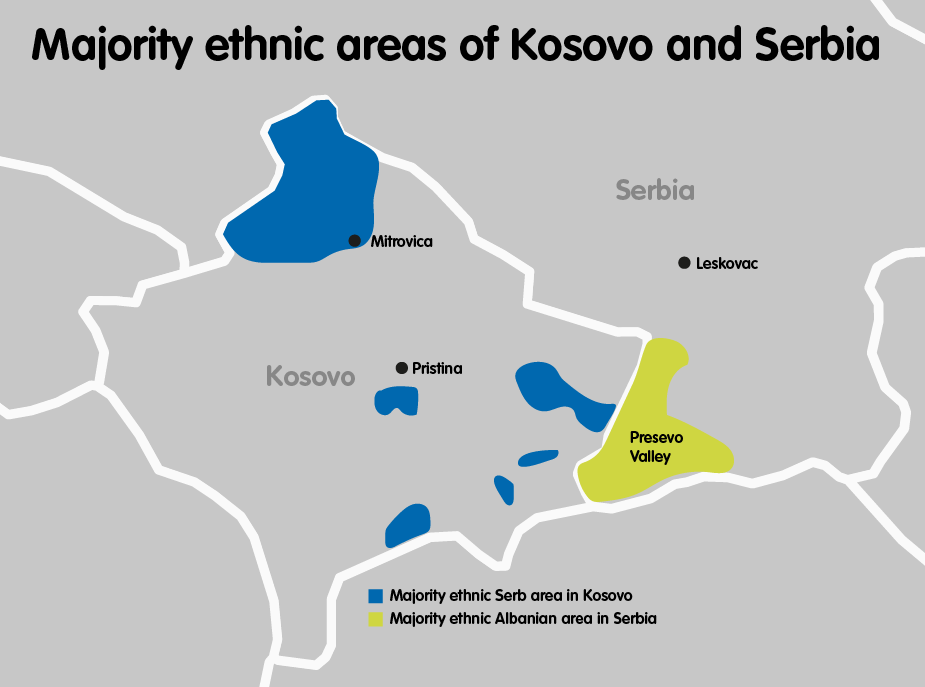

Land swap proposals between Serbia and Kosovo have been more seriously considered since the unfeasibility of creating the ASM became obvious. Certainly, Serbia’s president, Aleksandar Vučić, makes regular reference to this plan in Belgrade.[16] Although the idea is not wholly new, since the ending of the dialogue Vučić has made it clear to the Kosovo government that he wants some territorial concessions in exchange for recognition.[17] Sources suggest that draft plans exist for territorial exchange, according to which Kosovo would receive some Albanian-majority villages in southern Serbia while Serbia would get the majority of North Kosovo, with the exception of North Mitrovica, which would be granted some kind of internationally secured special status. Free movement of people would be guaranteed across the borders, and Gazivoda Lake, the main source of drinking water in the area, would be administered jointly by the two states. In exchange for such an agreement, Serbia would recognise Kosovo.[18] While Vučić has the power to have such an agreement ratified in Serbia, ratification in Kosovo would be much more doubtful, given that territorial exchange is unpopular among the Kosovo public and political parties.

Some opposition politicians in Kosovo think that including local Serbs in the dialogue would also be part of the solution.[19] While it is not entirely clear how this would move the process out of the deadlock (especially since political representatives supported by Belgrade through Srpska Lista monopolise the representation of Serbs in Kosovo), giving local Serbs a voice in the talks would certainly improve the legitimacy of the process. It could also lead to some practical solutions owing to their local contacts and knowledge, while also responding to the Serbian government’s much-repeated claim that its main aspiration is to secure the situation of local Serbs.[20]

Technical agreements

The highly political issue of the ASM has run into many obstacles, but it is also the case that most of the so-called technical agreements signed since 2011 have been only partially implemented, or not implemented at all. Many have fallen victim to high politics, with one side blocking the execution of technical deals in order to put pressure on the other. The technical agreements were well designed, but they lost credibility because of the constant renegotiations. Issues such as freedom of movement were renegotiated in more than 50 meetings, and customs in more than in a 100 meetings. But, ultimately, the problem comes down to a question of jurisdiction: if Serbia recognised Kosovo’s sovereignty, many of the existing problems would simply disappear or would be much easier to solve. For instance, technical agreements not fully enforced because Serbia disputes Kosovo’s sovereignty include the International Border Management (IBM) agreement, where Serbia is reluctant to install permanent border posts on the Kosovo-Serbia border, as it opposes the establishment of an international border with Kosovo.[21] Similarly, there is a bilateral deal on freedom of movement that has been only partially implemented because Serbia recognises Kosovo ID cards but not Kosovo documents and certificates, again for the same reason.

At the same time, some of the technical agreements would bring the most benefit to Kosovo Serbs in North Kosovo. The following section examines some of these issues in more depth, including looking at cases where agreements have been concluded but implementation has been incomplete, and where, despite the tendency of high politics scuppering everything, it could still be possible to make some progress.

The courts: The Brussels Agreement in 2013 provided for the integration into Kosovo’s system of the courts operating in Serbian parallel structures. As both sides had to adopt a number of legal changes, the process lasted for years. Serbian judges were finally integrated into Kosovo’s judiciary in October 2017. Overall, this has been a success.[22]

While the new courts have been operational in the sense that they can receive new cases, clarification over what should happen with the cases litigated and the rulings adopted in the parallel system is still lacking. After 1999, Serbs living in North Kosovo mostly relied on the parallel courts operated by Serbia, which were illegal in Kosovo. These courts received new criminal cases up until July 2013, and civil cases up until October 2017. Final rulings and administrative decisions adopted during this period by the parallel institutions cannot be enforced as Kosovo authorities, including the notaries and land registry offices, do not yet recognise them as valid. According to the Brussels Agreement’s provisions on the judiciary, the rulings of the parallel courts should be recognised in Kosovo, but Kosovo has yet to define the procedure of recognition and enforcement of the rulings of these courts and other administrative organs.[23] Several options have emerged for the enforcement of final rulings: they could be directly accepted as part of Kosovo’s case law; the Mitrovica district court could decide on them; or some other solution could be found. Belgrade wants both the rulings of the courts and administrative organs to be included in this process, while Pristina is currently stating that it will accept only court rulings.[24]

A further problem is that judicial archives have not yet been officially delivered to the Kosovo authorities. Many of these were transferred to Leskovac in Serbia before the integration of the judiciary, which placed an extreme workload on the courts in Leskovac. To fulfil interim benchmarks of the EU Common Position Chapter 35 on the judiciary, Serbia will need to adopt a special regulation on integrating Serbian judicial institutions located in Kosovo into the Kosovo system.[25] Sorting out these issues would fulfil a crucial interest of Kosovo Serbs, whose right of access to justice has suffered as a result. Both Pristina and Belgrade share the responsibility for leaving this process uncompleted.[26]

Another outstanding issue is that Serbia has failed to provide quarterly reports on the payment of pension benefits for integrated judicial personnel. This obligation is again based on one of the interim benchmarks of Chapter 35, which Serbia has not fulfilled.[27] But submitting these reports would help increase transparency and reduce the fear in Kosovo that Serbia exerts undue influence over the integrated personnel. Serbian judges and police working in the Kosovo system receive pensions from Serbia on top of their salaries, as everyone integrated into the Kosovo system was first retired from the Serbian system. The fear in Kosovo is that, once the ASM is created, these remittances will allow Belgrade to exercise effective control over Serbian judges, police, courts, and municipal assemblies.[28]

Police integration also formed part of the 2013 Brussels Agreement. Accordingly, Serbian police forces were officially disbanded and integrated into the Kosovo police. This agreement has been generally regarded as a success. Lately, however, some tensions have emerged between North Kosovo police officers and the Pristina authorities. According to Pristina, Serbian police chiefs maintain formal channels with the Kosovo authorities but in reality have begun responding more to Belgrade than to Pristina.[29] In May 2019, the Kosovo authorities ordered a major raid in the north carried out by the ROSU Kosovo special police forces, and they arrested several members of the local police, mainly Serbs. The incident provoked hostile rhetoric from Belgrade.

Altogether, there is a lack of trust between the legal and security apparatuses of the two countries, which is exacerbated by the absence of formal cooperation. This lack of trust prevents the relevant authorities in both countries from adopting the necessary legal decisions. This is despite the fact that judicial cooperation in civil and criminal matters and police cooperation with Kosovo (such as simplification of the exchange of information between law enforcement agencies) is part of the EU’s accession conditionality for Serbia, with Chapter 24 stating “with strict adherence to the requirements of status neutrality”. However, currently formal and direct police cooperation exists only between the border police, which was provided for by the Integrated Border Management agreement implemented in 2013.[30]

Apart from this, there is no formal cooperation between the two judiciaries and police, even if indirect and informal channels of communication exist. Judicial and police cooperation has not been on the agenda of the dialogue. Serbia’s status as an EU candidate nevertheless means that cooperation with Kosovo’s judicial and police structures remains an obligation based on the conditionality requirements of Chapter 24.

Land registry records of Kosovo are still yet to be transferred from Serbia to Kosovo. The Serbian authorities took land registry (cadastral) documents registered between 1983 and 1999 to Belgrade in 1999. Kosovo is therefore still missing all these records. In 2011, as part of the Belgrade-Pristina dialogue, Kosovo and Serbia agreed that the missing records should be transferred to Kosovo. Belgrade has digitalised the records, making them easily transferrable to Kosovo. After much procrastination, in 2016 Kosovo set up an agency to verify and compare the old land registry books of Serbia with the new ones of Kosovo.[31] However, all records still need to be reviewed and compared, which means approximately 300,000 items, including private and public property.

This new agency, the Kosovo Property Comparison and Verification Agency (KPCVA), has the task of settling claims and resolve discrepancies between land registry documents taken to Serbia in 1999 and Kosovo’s current land registry records. Cleaning up the land registry is especially important for Kosovo Serbs, many of whom lost their property 20 years ago. In 1999, the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) registered 42,749 seized properties, 95 per cent of which belonged to Serbs. Multiple claims to the same property, illegal occupations, and a confusing mix of laws also hamper the process. The KPCVA has already adjudicated most of the registered claims, while around 1,000 are outstanding. At the same time, the enforcement of decisions has been weak. The KPCVA struggles to evict illegal occupants and does not have enough funds to pay the $3.2m compensation to those claimants who won their case with the agency, or to demolish illegal buildings. Serbs displaced from Kosovo have therefore had great difficulty claiming their property in Kosovo.

Kosovo is not keen on receiving these old land registry records, as it created a new land registry system, and many publicly owned properties have been transferred into private ownership through deals benefitting oligarchs and political actors. Most land around Pristina was formerly municipal or socially owned property that was transformed into private businesses. Some in the political and the business elite do not want to bring in evidence that would challenge the existing property relations.[32]

The lack of trust between the two sides is also a significant factor delaying the process. The Kosovo authorities do not trust that Serbia has not tampered with the registries it has kept since 1999. Serbia does not trust that the KPCVA will do a fair job while comparing and verifying the registries. For this reason, an international body such as the European Land Registry Association could play a role in helping clean up the land registry records.[33]

Public property issues: By the end of Serbia’s rule in Kosovo, Serbia had taken an estimated $1.5 billion from Kosovo’s pension funds, and seized the privatisation fund of Kosovo, worth around $600m.[34] Serbia also took the private savings of citizens. In this context, losing the pensions and private savings has especially painful for Kosovo citizens.[35] Kosovo Albanians are currently collecting data and developing a file on repatriation and war damages, producing a significant bill that will eventually emerge on the agenda. Serbia has financial claims on Kosovo too, as it wants to recover the value of its investments in companies such as the Trepca mine, the Gazivoda water company, and the Brezovica ski resort.[36] But, if the same method is used as that followed in the post-Yugoslavia succession agreements, Serbia would likely lose out. This issue will almost certainly remain unresolved until such time as Serbia recognises Kosovo.

The issue of missing persons was not addressed as part of the Belgrade-Pristina dialogue. The regional commission for the establishment of facts about war crimes and gross human rights violations in the territory of former Yugoslavia (RECOM) is a wide coalition of NGOs, individuals, and governments set up to deal with this problem at the regional level. It is due to start its work in 2022 and complete it by 2025. Finding missing persons from the conflicts is also part of the EU’s conditionality towards the various countries, where cooperation has been ongoing at the bilateral level. In Kosovo, around 1,200 Albanians and 400 Serbs disappeared who are not accounted for. In Croatia, 2,016 cases were still open last year, and 7,200 in Bosnia.

Under the leadership of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), in 2018 three meetings of the Belgrade-Pristina Working Group on Missing Persons took place. Serbia responded to requests from Pristina and searched alleged grave sites in the Raska region in 2018, but no remains were found. During 2018, only seven cases were resolved regarding cases between Serbia and Kosovo. Several meetings took place with Croatia in 2018, but only 39 cases were resolved between Serbia and Croatia. Serbia appointed a special envoy for missing persons in Croatia, which was welcomed by the European Commission.[37] Bosnia signed agreements with Serbia and Croatia on bilateral cooperation on the search of missing persons in July 2019.[38]

The large number of unresolved cases indicates that more should be done for discovering the fate of missing persons. Despite this forming part of EU conditionality, Serbia had been reluctant to open its military archives for further research, hampering the process in Croatia, Bosnia, and Kosovo. However, the ICRC has recently received positive signals from Belgrade about access to these documents.[39] The Kosovo authorities have also claimed to have no information on the Kosovo Liberation Army’s activities related to missing persons. Because of the potential involvement of the political elite in war crimes, governments in the former Yugoslavia are often not keen on revealing the information necessary for finding people who went missing. At the same time, the ICRC wants to keep this issue depoliticised as much as possible, and to make the most of its own neutrality to help resolve the remaining cases.[40]

Freedom of movement: An agreement on the freedom of movement signed in 2011 provided for the mutual recognition of ID cards and documents. This has been partially implemented. While citizens can cross the Serbia-Kosovo border with ID cards, Kosovo cars need to change their licence plates when entering Serbia. Kosovo does not recognise driving licences issued by Serbia to Serbs living in Kosovo. The two countries do not accept passports issued by the other side. Official Kosovo documents, such as marriage certificates, are not recognised in Serbia, even those that were issued by UNMIK.[41] This issue is not likely to be resolved without Serbia’s recognition of Kosovo’s statehood.

Mutual recognition of diplomas: An agreement on the mutual recognition of diplomas was first signed in 2011, followed by another deal in 2016 that referred to certificates at all levels of schooling. According to these agreements, the mutual recognition of diplomas should take place gradually by the European Association of Universities through an international certification process. In addition, according to a unilateral decision by the Kosovo authorities, since 2016 Serbian diplomas from Kosovska Mitrovica have been recognised in Kosovo through a verification process. This process is much easier and simpler than the recognition of diplomas from Serbia, which must be validated before they can be recognised in Kosovo. In the same way, Kosovo diplomas must be validated in Serbia.[42] The validation of Kosovo diplomas in Serbia has hardly functioned in practice, which especially harms Albanians from southern Serbia, many of whom study at universities in Pristina.

Professional recognition between the two countries is also absent, including the recognition of vocational degrees: for example, Serbian judges taking up their post in the Kosovo system having to take the Kosovo bar exam. The other problem is that the 2011 and 2016 agreements did not cover Serbian institutions operating within Kosovo, but only Serbian schools and universities functioning in Serbia and those operating under the Kosovo education ministry. The Serbian language education system in Kosovo is a completely separate system from Kosovo’s education system, and is organised and led by the Serbian education ministry, which was omitted from the agreements. Serbian schools operate all over Kosovo, in places where the Serbian minority lives. But degrees and certificates issued in these Serbian schools in Kosovo are not recognised in Kosovo. The mutual recognition of school certificates and diplomas would serve the interests of both Kosovo Serbs and the Albanian minority in Serbia. The EU could play a more visible role on this file, placing pressure on the two countries to address the obstacles that hamper the process of validating diplomas.

The Serbian Orthodox Church: The situation of the SOC in Kosovo is an especially sensitive issue. Kosovo is home to many medieval Serbian Orthodox monasteries, four of which are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Serbia wants the Kosovo constitution’s preamble to recognise that the SOC is part of Serbian cultural heritage. Disagreements about this issue led to Serbia obstructing Kosovo’s accession to UNESCO, which currently recognises Serbia as the home and protector of these monasteries. Many of these monasteries were attacked during a wave of ethnic incidents in 2004, and so it is understandable that Serbia expects a more reassuring guarantee for the preservation of these churches. Part of the solution would be better enforcement of existing guarantees that were included in the Ahtisaari Plan, such as giving stronger legal safeguards for the SOC as the owner of these religious sites. Furthermore, the Kosovo law on special protective zones is not properly respected and implemented.[43] The example of the Decani monastery and some other similar cases raises doubts concerning Kosovo’s role as a good guardian of Serbian cultural heritage. This monastery had a property dispute with the municipality of Decani, which the monastery won in 2012 before Kosovo’s Supreme Court. The ruling was confirmed by the Constitutional Court of Kosovo in 2016. But the judgment prompted protests by Kosovo Albanians, and the authorities have refused to carry out the court’s decision. The EU has called for its enforcement, but without success. It could still play a role, though, by holding the Kosovo authorities to account over their obligation to grant protection to the SOC monasteries, as also provided for in the current framework of Serbia-Kosovo relations.

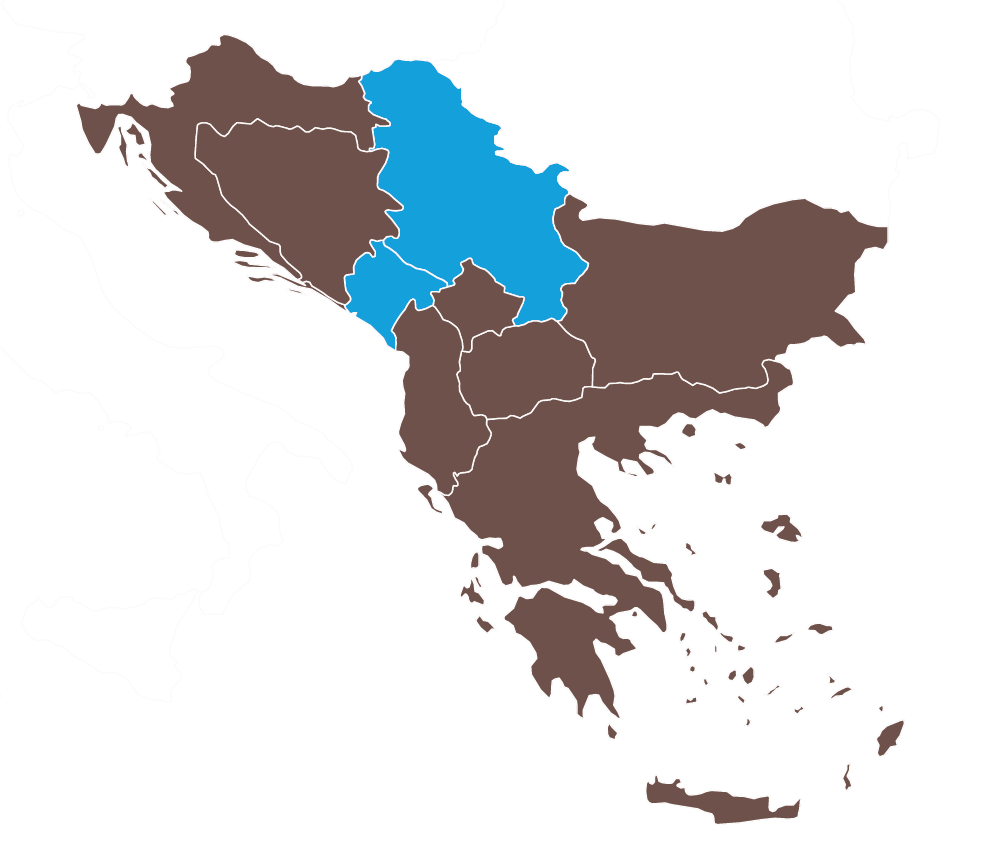

Serbia and Croatia

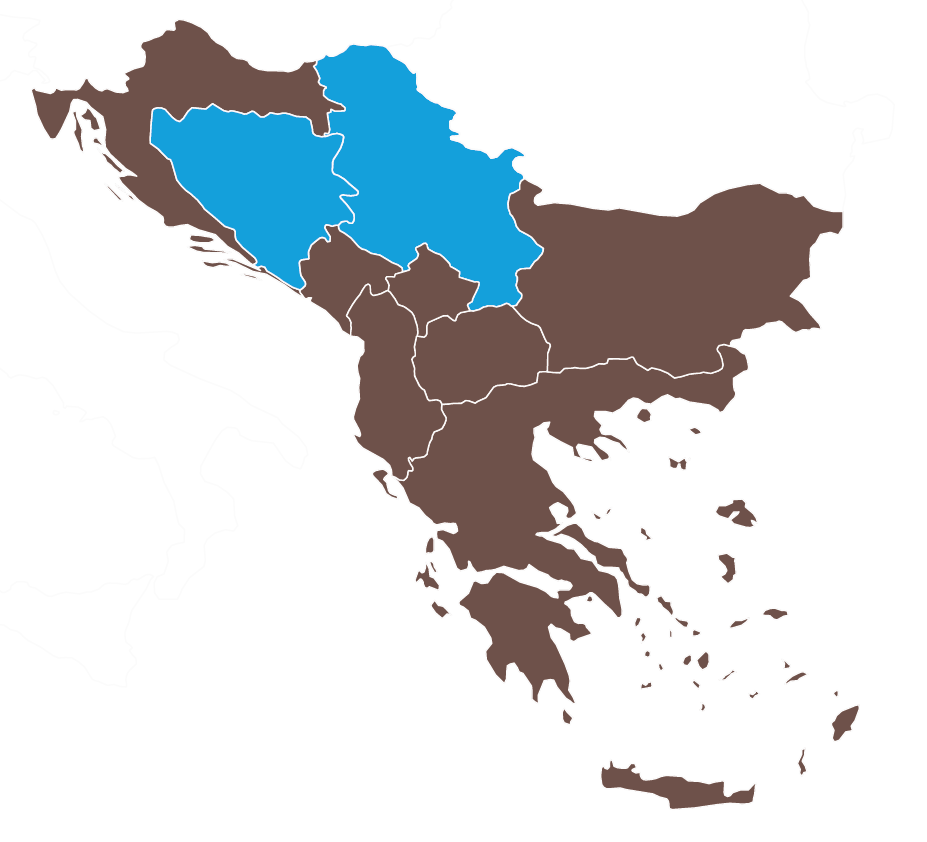

Good neighbourly relations are part of the EU’s conditionality towards the Balkan candidate states and would-be candidates, closely monitored by the European Commission in its annual progress reports. In this context, these reports include reviews of Serbia’s relations with its neighbours, including with Croatia. The latest report, from 2019, concluded that Serbia’s relations with Croatia “continued to be mixed”. There are several disputes causing discord between these two states, among these their undefined border. Sources indicate that the territory at dispute between Serbia and Croatia covers between 100-140 square kilometres along a 138 km section of the Danube River. Ninety percent of this area is currently under Serbian control. The Croatian position is that the old municipal boundaries located along the river, based on the land registry of the Austrian-Hungarian monarchy, should be the borderline (see map).[44] These municipal borders originally followed the Danube, but were in place before the river’s present course was set in the nineteenth century, and as a result there is a ‘mismatch’ between the river and the border. Croatia claims that the constitution of Yugoslavia recognised these old municipal borders, but this is disputed by Serbia. The Serbian stance is that the middle of the Danube should be the borderline, although the river’s course itself is not entirely fixed and its position still changes. In the early 1990s the Badinter Commission was established to provide advice about the status of the Yugoslav republics. Its recommendation to follow Yugoslav republican borders has become the internationally adopted way of settling the borders between post-Yugoslav states, and applying this method to this case would support the Croatian position. However, if the border was adjusted according to Croatia’s claim, both countries would control some enclaves surrounded by the other state along the border. This could be avoided by exchanging some territories.

Good neighbourly relations are part of the EU’s conditionality towards the Balkan candidate states and would-be candidates, closely monitored by the European Commission in its annual progress reports. In this context, these reports include reviews of Serbia’s relations with its neighbours, including with Croatia. The latest report, from 2019, concluded that Serbia’s relations with Croatia “continued to be mixed”. There are several disputes causing discord between these two states, among these their undefined border. Sources indicate that the territory at dispute between Serbia and Croatia covers between 100-140 square kilometres along a 138 km section of the Danube River. Ninety percent of this area is currently under Serbian control. The Croatian position is that the old municipal boundaries located along the river, based on the land registry of the Austrian-Hungarian monarchy, should be the borderline (see map).[44] These municipal borders originally followed the Danube, but were in place before the river’s present course was set in the nineteenth century, and as a result there is a ‘mismatch’ between the river and the border. Croatia claims that the constitution of Yugoslavia recognised these old municipal borders, but this is disputed by Serbia. The Serbian stance is that the middle of the Danube should be the borderline, although the river’s course itself is not entirely fixed and its position still changes. In the early 1990s the Badinter Commission was established to provide advice about the status of the Yugoslav republics. Its recommendation to follow Yugoslav republican borders has become the internationally adopted way of settling the borders between post-Yugoslav states, and applying this method to this case would support the Croatian position. However, if the border was adjusted according to Croatia’s claim, both countries would control some enclaves surrounded by the other state along the border. This could be avoided by exchanging some territories.

In the early 2000s a bilateral committee was set up to address this issue, but it has not been active in recent years. As a unilateral veto from Croatia could threaten Serbia’s accession process, the EU has some influence – and interest – here to set about resolving this sooner rather than later.[45]

Toxic high-level political relations between Serbia and Croatia do not foster the resolution of this problem. Croatia regularly complains about war crimes prosecutions in Serbia and how convicted war criminals are handled domestically. For example, in 2018 the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) found Vojislav Šešelj guilty of inciting deportations, persecution, and other inhumane acts against Croats. He is now a member of the Serbian parliament and regularly holds nationalist rallies. The Serbian authorities regularly celebrate many other convicted war criminals and appoint them to senior positions. However, improvements in bilateral relations can hardly be expected given Croatia’s similar approach to its own war criminals.[46] For example, in 2018 it questioned an ICTY verdict that stated that Croatia participated in a joint criminal enterprise together with Bosnian Croat leaders to ethnically cleanse Bosnian Muslims during the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Although Croatia has never blocked Serbia’s accession negotiations, its diplomats tend to be vocal about their concerns in the associated EU working groups. All this reinforces negative voices in the EU bodies, and contributes to the weakening of overall support for Serbia’s EU integration.

When it comes to Serbia, Croats care most about war crimes issues, but they are also ready to join the Poles and others in criticising Serbian foreign policy’s favouring of Russia over the EU. Bulgaria has also started to raise concerns over the Bulgarian minority in Serbia, and, similarly to the Croats, is ready to support Western governments’ regular criticism of the lack of media freedom and weaknesses in the rule of law in Serbia. Thus, indirectly, Croat complaints could slow down Serbia’s EU accession process.[47]

Serbia and Montenegro

Serbia and Montenegro traditionally had very close links with each other, given that the two were joined together in the same state until 2006, when Montenegro proclaimed its independence from the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro through a public referendum. Overlapping ethnic and religious identities characterise the Orthodox Slav populations of the two countries, creating strong social and political ties. However, bilateral relations are not without fractions: several issues trigger occasional arguments between them: Montenegro’s recognition of Kosovo’s statehood; Montenegro’s prohibition of its citizens also having Serbian citizenship; and the operation of the Serbian Orthodox Church (SOC) in Montenegro. Among these three, the last has caused the most turmoil recently. The EU closely monitors developments related to Serbia-Montenegro relations in its progress reports, with particular attention to the issue of citizenship rights and the process of border demarcation.[48]

Serbia and Montenegro traditionally had very close links with each other, given that the two were joined together in the same state until 2006, when Montenegro proclaimed its independence from the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro through a public referendum. Overlapping ethnic and religious identities characterise the Orthodox Slav populations of the two countries, creating strong social and political ties. However, bilateral relations are not without fractions: several issues trigger occasional arguments between them: Montenegro’s recognition of Kosovo’s statehood; Montenegro’s prohibition of its citizens also having Serbian citizenship; and the operation of the Serbian Orthodox Church (SOC) in Montenegro. Among these three, the last has caused the most turmoil recently. The EU closely monitors developments related to Serbia-Montenegro relations in its progress reports, with particular attention to the issue of citizenship rights and the process of border demarcation.[48]

Serbia views every policy through the lens of the Kosovo question, and this spills over into relations with other countries. For example, Serbia resents and does not recognise a border demarcation deal that Montenegro has with Kosovo, regarding it as a violation of its own territorial integrity. The process of border demarcation between Serbia and Montenegro is still pending because of the Kosovo issue, despite the fact that there are actually no disputes between the two states about where the border should be. But, after Montenegro recognised Kosovo’s independence, Serbia refused to continue negotiations if Kosovo was not part of this process as a part of Serbia.

Serbia also has complaints about Montenegro’s citizenship policy, which restricts dual citizenship. This primarily concerns Montenegrins who live in Serbia and would like to be citizens of both countries. Montenegrin citizens who possessed dual citizenship before 2006, when Montenegro gained independence, were able to retain it. Yet, since 2006 Montenegrin citizens have not been able to become citizens of another state without losing their Montenegrin citizenship, and citizens of other countries are now no longer able to gain Montenegrin citizenship without giving up their original citizenship. According to Montenegro’s citizenship law of 2008, exceptions can be made for citizens of countries with which Montenegro has signed bilateral treaties of citizenship. Around 270,000 people of Montenegrin origin live in Serbia. Many of them oppose both Montenegro’s independence and Montenegro’s ruling Democratic Party of Socialists, which was the main architect of Montenegrin statehood. If members of this group of 270,000 were to become Montenegrin citizens and thus gained the right to vote in Montenegro, it could have far-reaching political consequences in a country of just 620,000 inhabitants. For this reason, the Montenegrin government is unlikely to compromise on this matter.

Besides these issues, which concern Serbia, the Montenegrin authorities worry about the role of the SOC in Montenegro.[49] Most recently, tensions arose following the government’s introduction of a new bill on religious freedom that would effectively transfer the ownership of most church property in the country to the Montenegrin state. In 2015 the government tried to introduce a similar bill, but withdrew it after protests from the SOC.[50] According to this new legislation, passed at the end of 2019, every church, including the SOC, would be able to retain its property only if it can demonstrate evidence of its ownership from before 1918 (after which the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes took over the control of religious property in Montenegro).[51] Serbian media accuse the Montenegrin government of trying to rob the SOC, while Patriarch Irinej of the SOC has threatened Montenegro’s president, Milo Đukanović, with an anathema (a formal curse). The Serbian government has also warned Montenegro of worsening diplomatic relations[52] By contrast, the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission welcomed the draft law as “it brings important positive changes to the existing, out-dated legislation”. The government, after having consulted with the Venice Commission, submitted the legislation to parliament in December 2019, and it was subsequently adopted in the same month[53] amid fierce protests in Montenegro and Serbia.

Although a separate Montenegrin Orthodox Church was founded in 1993, the majority of Montenegro’s Orthodox believers attend the SOC, which has a big influence on public opinion.[54] Many priests belonging to the SOC, among them the metropolitan of Montenegro, hold strongly nationalistic and socially conservative views, including denying Serbian war crimes in the Yugoslav conflicts. They are vocally against LGBT rights and gender equality; deny the existence of Montenegrin national identity; call NATO the Fourth Reich; and spread hate speech against Muslims, who form a sizeable minority group in Montenegro.[55] The SOC is also closely affiliated with Russia, and so it is often viewed as a Russian proxy.[56] According to the court verdict on those behind the 2016 coup attempt in Montenegro, a Serbian Orthodox monastery was among the sites where the plot had been prepared. Altogether, the SOC is politically hostile to the Montenegrin state and its Western orientation, which is why the Montenegrin government sees it as a security threat.

So far the SOC has not been officially registered in Montenegro, it does not pay taxes, and the authorities do not know how many of its priests are actively serving in the country. The new law will not force it out of Montenegro, even if it cannot provide evidence about ownership of properties where it operates. The church will not lose its properties in the functional sense. But the authorities will gain greater oversight and control over it.

Montenegro and Croatia

Although Montenegro in general has good relations with its neighbours, one of the few outstanding issues concerns the border demarcation with Croatia at the Prevlaka peninsula. The EU in its regular progress reports on Montenegro closely follows this issue and expects the two sides to come to an agreement. This disputed territory was formerly under the control of the army of Yugoslavia, which is why the border was not clearly delineated between the two republics before that country’s dissolution. Montenegro and Croatia signed a provisional agreement in 2002 on the border regime, which regulates maritime traffic in the bay of Kotor. This has functioned well in practice, and the land border is clear. However, the sea border remains under dispute, and this impacts on potential control over oil and gas exploration. The two countries agreed that if they cannot settle the dispute bilaterally the issue will be brought to an international body, such as the International Court of Justice or an international arbitration committee. Accepting the ruling of an international body would be politically easier for both governments than giving up territory unilaterally.[57] However, settling this problem at the moment is not high on their bilateral agenda. Reaching a solution would first and foremost require the parties to come together and reach a consensus, which the EU could make efforts to encourage more firmly.

Although Montenegro in general has good relations with its neighbours, one of the few outstanding issues concerns the border demarcation with Croatia at the Prevlaka peninsula. The EU in its regular progress reports on Montenegro closely follows this issue and expects the two sides to come to an agreement. This disputed territory was formerly under the control of the army of Yugoslavia, which is why the border was not clearly delineated between the two republics before that country’s dissolution. Montenegro and Croatia signed a provisional agreement in 2002 on the border regime, which regulates maritime traffic in the bay of Kotor. This has functioned well in practice, and the land border is clear. However, the sea border remains under dispute, and this impacts on potential control over oil and gas exploration. The two countries agreed that if they cannot settle the dispute bilaterally the issue will be brought to an international body, such as the International Court of Justice or an international arbitration committee. Accepting the ruling of an international body would be politically easier for both governments than giving up territory unilaterally.[57] However, settling this problem at the moment is not high on their bilateral agenda. Reaching a solution would first and foremost require the parties to come together and reach a consensus, which the EU could make efforts to encourage more firmly.

Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina

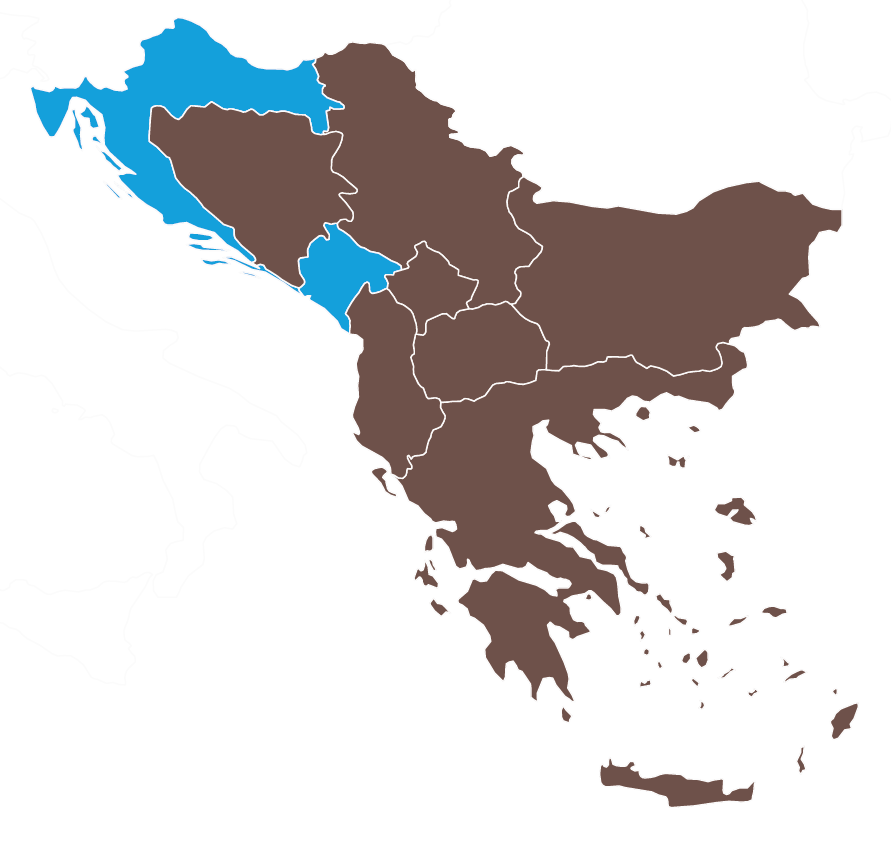

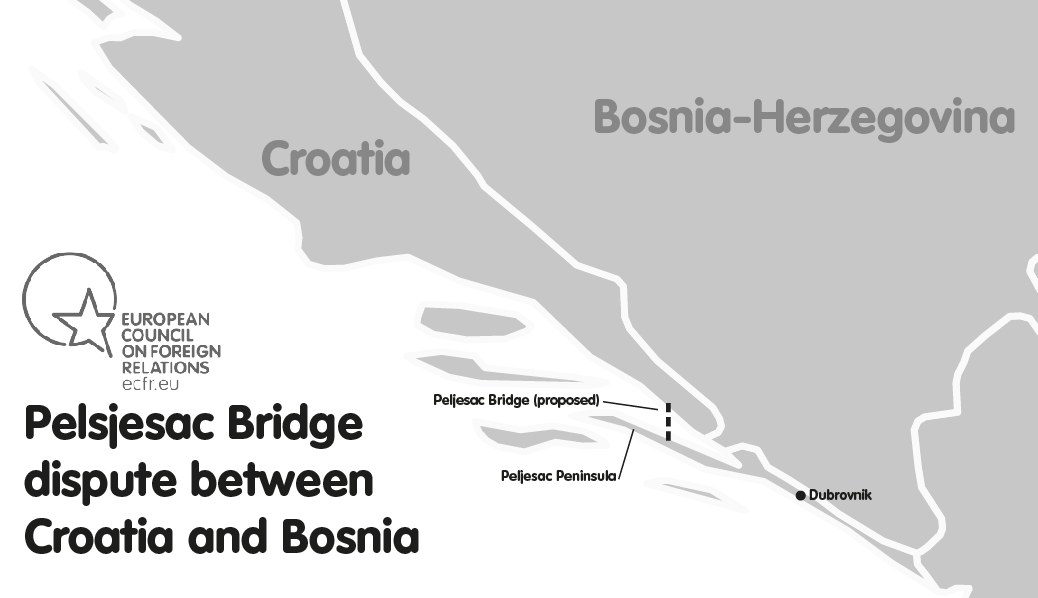

In its last analytical report on Bosnia and Herzegovina the EU judged bilateral relations between Bosnia and Croatia to be generally good, but it also noted the existence of “open issues concerning the borderline at land and sea”.[58] Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina contest their maritime border, which runs between the Pelješac peninsula on the Croatian side and the Klek peninsula on the Bosnian side. In 1999 the two countries signed a border agreement which was immediately questioned by both and thus failed to resolve the issue.

In its last analytical report on Bosnia and Herzegovina the EU judged bilateral relations between Bosnia and Croatia to be generally good, but it also noted the existence of “open issues concerning the borderline at land and sea”.[58] Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina contest their maritime border, which runs between the Pelješac peninsula on the Croatian side and the Klek peninsula on the Bosnian side. In 1999 the two countries signed a border agreement which was immediately questioned by both and thus failed to resolve the issue.

In recent years, Croatia has been planning to build a bridge to connect the Pelješac peninsula with Dubrovnik. The idea of the bridge was publicly proposed in 1997, and construction works were officially launched in 2005 by then prime minister Ivo Sanader.[59] However, in reality construction commenced only in 2018, and it is planned to be finished by 2022. The bridge would block Bosnia’s access to international waters, and so Bosnia opposes the project (see map). However, so far Bosnia has not been able to politically act on this issue. While its lower house of parliament issued a declaration against building the bridge in September 2017, the upper house voted down the declaration as unconstitutional. Although it would be in Bosnia’s interest to bring the Pelješac question to the International Court of Justice or an arbitration body, de facto Bosnia cannot raise issues formally as it has been unable to adopt a unified state position because of internal disagreements, especially with Republika Srpska, one of the country’s confederal entities. Bosnia also has other border disputes with Croatia near Bihac, along the Una River near Kostajnica, and near Martin Brod.[60]

Further issues between Croatia and Bosnia include Croatian grievances related to the lack of representation of Croats in the Bosnian state presidency and to the general status of Croats in Bosnia. Croats’ representation in state institutions has been problematic due to their minority position in the federation entity. In the state presidency, Croats are officially represented by Željko Komšić, who is an ethnic Croat, but whose election owes much to support from Bosniaks. A recurring demand has been for Croats to have their own federal entity in Bosnia, which could provide a better guarantee for their survival as a community in Bosnia in light of their dwindling population. The number of Croats has decreased over the years: in the early 1990s they represented 17 per cent of the population of Bosnia; these days they are around 15 per cent. They constitute a minority in the federation as well, and can be outvoted by Bosniaks, as the election of Komšić illustrates. This is an issue that Croatia could potentially raise at a later stage of Bosnia’s EU accession process, should it ever get that far.[61]

Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia

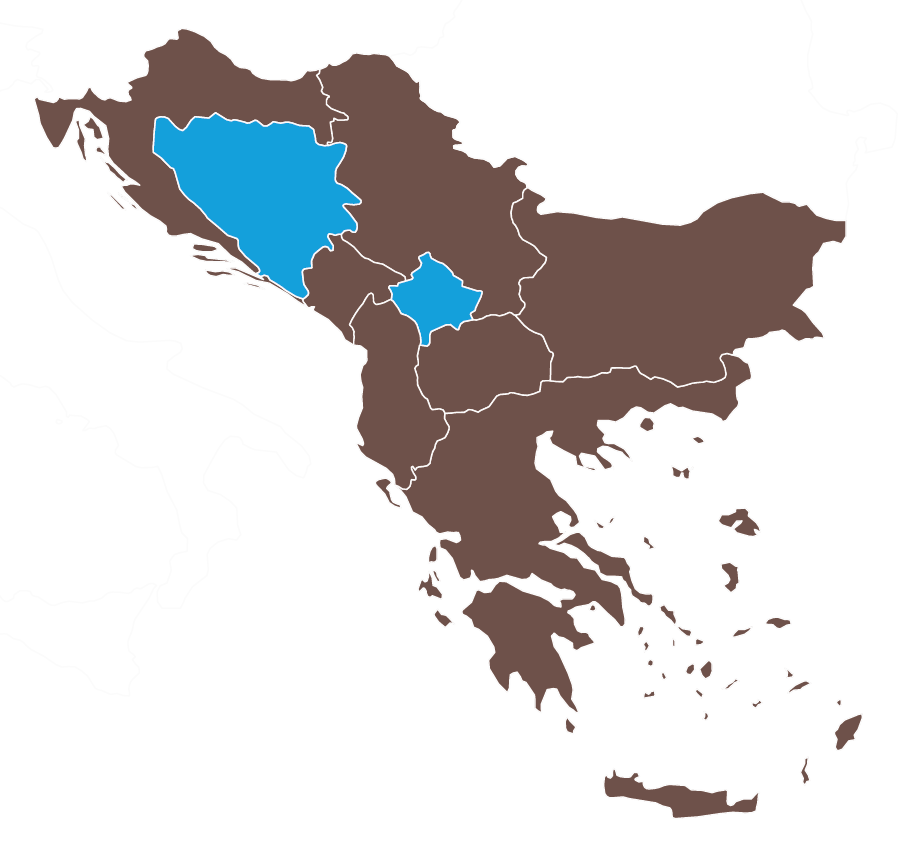

The EU believes bilateral relations between Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia to be good, but its progress reports cite the need to conclude negotiations over the border demarcation.[62] Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia dispute territory of around 40 square kilometres along the Lim River, situated at the lower course of the Drina River. The Lim flows from Montenegro through the Sandžak region, criss-crossing the Serbia-Bosnia border and leaving several Serbian and Bosnian villages practically in the other country. For instance, the village of Sastavci belongs to Bosnia, yet is a Bosnian enclave surrounded by the Serbian municipality of Priboj. The border also divides two hydroelectric plants, “Zvornik” and “Bajina Bašta”, and the area located along the Belgrade-Bar railway line. The power plants officially belong to Serbia, but the border, which is situated in the middle of the river, crosses dams and accumulative lakes, which serve the plant. Concluding a land exchange would be a solution to this, and Serbia proposed such a measure several years ago, but the two countries have reached no agreement so far.[63] Here, again, internal disagreement within the Bosnian institutions is hampering the resolution of this issue.

The EU believes bilateral relations between Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia to be good, but its progress reports cite the need to conclude negotiations over the border demarcation.[62] Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia dispute territory of around 40 square kilometres along the Lim River, situated at the lower course of the Drina River. The Lim flows from Montenegro through the Sandžak region, criss-crossing the Serbia-Bosnia border and leaving several Serbian and Bosnian villages practically in the other country. For instance, the village of Sastavci belongs to Bosnia, yet is a Bosnian enclave surrounded by the Serbian municipality of Priboj. The border also divides two hydroelectric plants, “Zvornik” and “Bajina Bašta”, and the area located along the Belgrade-Bar railway line. The power plants officially belong to Serbia, but the border, which is situated in the middle of the river, crosses dams and accumulative lakes, which serve the plant. Concluding a land exchange would be a solution to this, and Serbia proposed such a measure several years ago, but the two countries have reached no agreement so far.[63] Here, again, internal disagreement within the Bosnian institutions is hampering the resolution of this issue.

Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo

The EU regularly assesses the relationship between Kosovo and Bosnia-Herzegovina, and notes that there are no official relations between the two, as Bosnia and Herzegovina does not recognise Kosovo’s independence and maintains a strict visa regime.[64] Conducting good neighbourly relations is an obligation for both countries according to the EU’s conditionality policy, so the present deadlock has to be resolved should the two states want to move closer to EU membership. Bosnia-Herzegovina does not recognise Kosovo’s statehood and so also does not recognise its official documents. Kosovo does not have any agreements with Bosnia similar to those with Serbia, so bilateral relations are even worse than with Serbia. Under the influence of the Republika Srpska, one of Bosnia’s confederal entities, Bosnia regularly lobbies against Kosovo at regional forums. Most recently, Kosovo and Albania cancelled their participation at the Sarajevo summit of the Southeast European Cooperation Process in protest at Kosovo’s invitation as an “undefined subject” rather than as a state. Since 2008, citizens of Kosovo have needed visas to enter Bosnia, and so in 2014 Kosovo also introduced a visa regime for Bosnian citizens. And, as Bosnia does not even have an embassy in Pristina, Kosovo citizens must travel to Tirana to apply for Bosnian visas. Paradoxically, Bosnia does not recognise Kosovo identity cards and passports but it does accept Kosovo customs documents. Importantly, Kosovo imposed the 100 percent customs tax it recently introduced not only on Serbian goods, but also on products imported from Bosnia. These frozen relations pose a problem for Kosovo in particular, because many Kosovars have studied in Sarajevo, while important products, such as medicines, are imported from Bosnia.[65]

The EU regularly assesses the relationship between Kosovo and Bosnia-Herzegovina, and notes that there are no official relations between the two, as Bosnia and Herzegovina does not recognise Kosovo’s independence and maintains a strict visa regime.[64] Conducting good neighbourly relations is an obligation for both countries according to the EU’s conditionality policy, so the present deadlock has to be resolved should the two states want to move closer to EU membership. Bosnia-Herzegovina does not recognise Kosovo’s statehood and so also does not recognise its official documents. Kosovo does not have any agreements with Bosnia similar to those with Serbia, so bilateral relations are even worse than with Serbia. Under the influence of the Republika Srpska, one of Bosnia’s confederal entities, Bosnia regularly lobbies against Kosovo at regional forums. Most recently, Kosovo and Albania cancelled their participation at the Sarajevo summit of the Southeast European Cooperation Process in protest at Kosovo’s invitation as an “undefined subject” rather than as a state. Since 2008, citizens of Kosovo have needed visas to enter Bosnia, and so in 2014 Kosovo also introduced a visa regime for Bosnian citizens. And, as Bosnia does not even have an embassy in Pristina, Kosovo citizens must travel to Tirana to apply for Bosnian visas. Paradoxically, Bosnia does not recognise Kosovo identity cards and passports but it does accept Kosovo customs documents. Importantly, Kosovo imposed the 100 percent customs tax it recently introduced not only on Serbian goods, but also on products imported from Bosnia. These frozen relations pose a problem for Kosovo in particular, because many Kosovars have studied in Sarajevo, while important products, such as medicines, are imported from Bosnia.[65]

Albania and Greece

Albania and Greece have traditionally maintained close relations owing to their strong historical and cultural ties, the presence of the Greek minority in Albania, and Albanian immigration to Greece. More recently, bilateral relations have begun to develop more in earnest, especially since the end of communism in Albania, when the two countries signed a series of basic agreements. Greece is the largest investor in Albania, and an important trading partner and aid donor to the country. The relationship between the two has long been intense and not without its complications. The EU closely monitors developments in Albania-Greece bilateral relations in its progress reports on Albania, and it pays particular attention to: the construction of cemeteries for fallen Greek soldiers in Albania; the delimitation of the maritime border between the two countries; and the situation of the Greek minority in Albania. If it wants to join the EU, Albania must resolve any outstanding issues with Greece.