China’s investment in influence: the future of 16+1 cooperation

Uneven progress towards “16+1” cooperation frustrates Chinese ambitions

Introduction

by Angela Stanzel

China faced hard times in 2016 – at least when it comes to promoting its investment in Europe. The European Union is one of its most important economic and trading partners and the final destination of China’s flagship initiative, the New Silk Road. However, some EU member states have recently become increasingly critical of China’s push for more investment in Europe. Beijing has invested significant effort in building a new entry point into Europe through the central and eastern European (CEE) countries – in particular, through the 16+1 framework. As reflected in Agatha Kratz’s article in this edition of China Analysis, the CEE region is attractive to China thanks to its strategic geographical position for the New Silk Road project, its high-skilled yet cheap labour, and its open trade and investment environment.

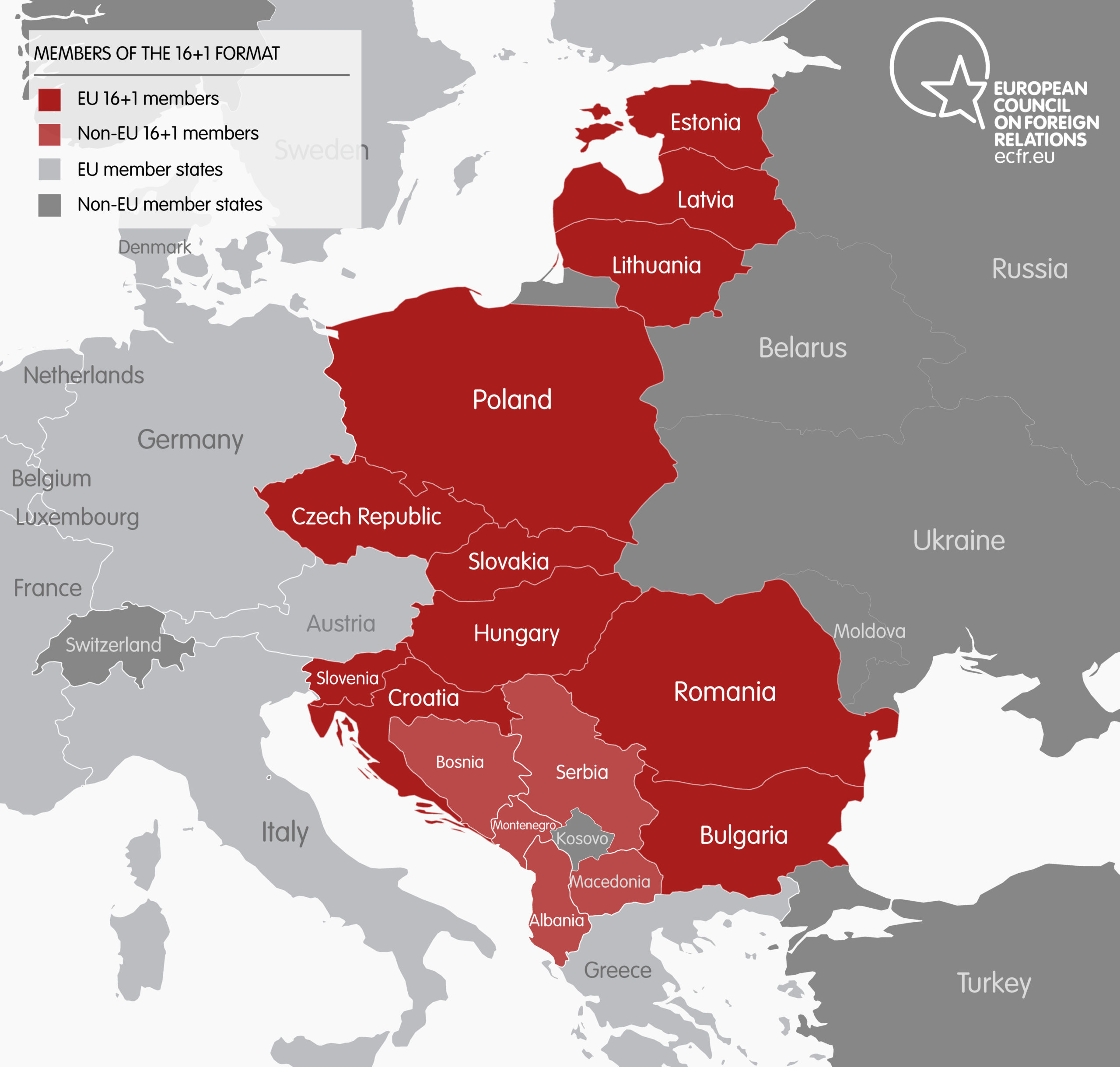

The 16+1 framework is a relatively new cooperation format initiated by China with 16 CEE countries in 2012. Since its formation the 16+1 has made some progress in strengthening dialogue and cooperation between China and CEE countries. The heads of state of the member countries meet annually and each meeting results in a list of agreements. During the fifth and most recent summit, held in Riga, Chinese premier Li Keqiang formally launched a €10 billion investment fund to finance infrastructure and production capacity projects. The 16 member countries are asked to contribute on a voluntary basis in order to raise more funds – though it remains to be seen how many are willing to support a funding structure controlled by China.

What this new collection reflects is that the tone of debate in China around the 16+1 is generally fairly critical, highlighting the problems and challenges that the Chinese government is meeting in its efforts to take the format forward. Three main points emerge.

Firstly, the level of cooperation between China and CEE participants is not consistent from country to country. Only a few, such as Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary, have so far benefited from Chinese investment. Other member countries, which hoped to receive investment, particularly for infrastructure projects, have been left disappointed. On the one hand, this has resulted in competition among the 16 for influence with China. On the other hand, as Chinese authors represented in this edition have observed, some CEE countries have become more cautious in cooperating with China. Justyna Szczudlik examines the situation in Poland, a country which is keen to expand cooperation with China but at the same time remains cautious – Poland and China failed once before to implement a joint infrastructure project.

Secondly, the format includes 11 EU member states among the 16, something which has created unease among the EU institutions and other member states. They are concerned that the format could be used by Beijing to ‘divide and rule’ the EU, and that the cooperation of some CEE countries with China could undermine their relations with the EU institutions.[1] Clearly, there is an economic aspect to this: for instance, that investment deals concluded with China might not be conform to EU guidelines or could undermine EU policies. But there is a political aspect too: this year, for instance, thanks to the objections of some member states, the EU’s statement on China’s legal defeat over the South China Sea avoided direct reference to China.[2] Of the 16, at least in the case of Hungary and Greece it appears that the government has become much more unwilling to criticise Beijing in light of the large amount of Chinese investment it has received in recent years (Slovenia and Croatia objected mainly in view of their own maritime disputes).

Thirdly, the ‘divide and rule’ perception also exists to some degree within the 16+1 itself, where China is strengthening bilateral relations with only some of the 16 and bestowing more attention on them than others. This year, the Czech Republic not only received the first Chinese president to visit the country, but this was also Xi Jinping’s first presidential visit to any of the CEE countries. Romania and Serbia also welcomed high-level business delegations from China this year, with €6 billion committed to Romania. Dragan Pavlićević takes a close look at Serbia and the efforts China is undertaking to signal willingness for more cooperation. China’s efforts have given some in Serbia reason to believe their country has secured a special place within the 16+1 and therefore have referred to the format – only, as we shall see, semi-jokingly –as the 15+1+1. Indeed, from the viewpoint of the countries who have benefited the least, the format might as well be called the 1+1+1+1 (and so forth), something which calls into question the nature of the format as a whole.

The authors represented here broadly share the conviction that improving EU-China relations, and economic relations in particular, would improve China’s cooperation with the CEE countries. However, what is largely missing from their analysis are some of the current key issues of the EU-China trade and investment cooperation. From the point of view of European business, reciprocity and market access are the key issues, yet substantive discussion of this remains thin on the ground in the Chinese debate. A real expansion of the debate in this way would also give renewed impetus to the 16+1 format, both for the EU 11 and the CEE participants as a whole.

Dividing without antagonising: China’s 16+1 image problem

by Angela Stanzel

The aim of the 16+1 initiative, which was set up in 2012, is to intensify China’s cooperation with 11 European Union member states and five Balkan countries.[3] Among the EU institutions there have been concerns about China institutionalising the 16+1 cooperation format, which already consists in a permanent secretariat (at the Chinese foreign ministry) and several associations and organisations. The emerging cooperation with the 11 member states in the format has also been seen by the EU as a sign of China’s ability to ‘divide and rule’ Europe. However, China’s cooperation has not been smooth across all 16 countries so far. Not all have benefited from Chinese investment as much as they might have hoped. This has resulted in a lack of willingness to pursue further cooperation. China’s One Belt, One Road initiative (OBOR), also called the New Silk Road initiative, and a newly created fund, might give new momentum to the relationship.

The authors discussed in this chapter have examined the challenges to China’s cooperation with the 16 central and eastern European (CEE) countries, and they present recommendations to tackle them. They agree that the 16+1 cooperation has moved from framing overall mechanisms and operations to specifying further development, as outlined, in particular, in the 2013 and 2014 Bucharest and Belgrade Guidelines for Cooperation between China and CEE countries.[4] Most see a distinct link between the construction of China’s OBOR and the development of the 16+1 format. They believe the CEE region is attractive for China as it seeks to establish its OBOR network. It is a strategic territory for OBOR, and such infrastructure cooperation can improve China's relations with CEE countries.

Divided perceptions

According to Long Jing, of the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, there are three ways in which CEE countries have responded to OBOR: high-level bilateral and multilateral meetings in which support towards the strategy is expressed; research and strategic planning to develop OBOR; and supporting documents outlining specific policies, such as memoranda of understanding.[5] However, she notes that there are still many CEE countries that have not responded to China’s OBOR initiative with any specific commitments. In her view this illustrates the challenges that are emerging from the 16+1 format. There is an urgent need to respond to challenges and fine-tune the existing cooperation mechanism. Three main points emerge.

Firstly, enthusiasm for participating in the 16+1, as well as the OBOR initiative, has varied due to differences among the economies, populations and market potential of the 16 CEE countries. Liu differentiates groups of countries based on the size of their economies. What he describes as large economies (such as Serbia) have been more able to take on China’s large-scale investment projects. Meanwhile, small- and medium-sized economies (such as Croatia and Slovenia) had welcomed the establishment of the 16+1 cooperation framework initially, but found it difficult to implement specific projects, according to Long. She sees a “cooperation vacuum” (合作真空, hezuo zhenkong) in countries where enthusiasm for and expectations of the existing cooperation with China are gradually declining. This difference in the degree of participation and enthusiasm for the existing cooperation mechanisms has also resulted in differing perception of the OBOR initiative among the CEE countries.

Secondly, the willingness of the CEE countries to cooperate also depends on their different “political identity” (政治身份, zhengzhi shenfen). These differences, such as whether they are an EU member state and member of the eurozone, have a profound effect on these countries’ strategies and willingness to cooperate with China. For instance, Serbia, which is not an EU member, is still more dependent on support for its economic development from outside the EU and therefore more willing to cooperate with China than the EU member states are, Long explains.[6]

Thirdly, the EU is concerned about China trying to use its economic relations for its ‘divide and rule’ policy. In Long’s view a geopolitical doctrine and cold war mentality has emerged, which is also triggering suspicion of China’s possible geopolitical intentions in establishing OBOR. This suspicion further hinders cooperation between China and the CEE countries; China should proactively respond to thia, Long urges.

According to Long, the current progress within the 16+1 mechanism has exposed the challenges China is facing in its attempt to shape a concrete framework for cooperation on OBOR. For OBOR to enter the next phase of implementation in the CEE region, she sees the need to move from government declarations to concrete cooperation. China’s cooperation with the CEE countries on OBOR should prioritise stronger relations with the EU in order to dispel existing concerns and improve China’s relations with the CEE countries, Long says.

16+1 as part of the ‘Silk Road’

Feng Min and Song Caiping, both affiliated to the Shanghai University of International Business and Economics,[7] suggest that China and the CEE countries should cooperate with each other on OBOR, taking into consideration the context of China-Europe relations, China-United States relations, China-Russia relations, and China's relations with its neighbouring countries. In their view, these external forces also influence China’s relations and cooperation with the CEE countries. The authors believe that strengthening cooperation with both Russia and the US is necessary because both countries’ concerns would increase the more China expands its relations with other countries in the framework of OBOR. Although Russia and China have agreed to cooperate on both their respective initiatives, OBOR and the Eurasian Economic Union, the authors expect difficulties to resurface once OBOR becomes operational. Meanwhile, they believe the US is concerned that China’s energy and transportation network could oppose US interests.

Similar to Long, Feng and Song highlight the need to integrate the EU’s concerns into cooperation with the CEE countries. In particular, China should focus on implementing the EU-China 2020 Strategic Agenda for cooperation in order to assuage the EU’s concerns.[8] They note that China and the CEE countries are currently formulating a medium-term cooperation plan, which is believed to make China-CEE cooperation much deeper and strategically significant. This could trigger more concerns on the EU’s part and requires China to make further efforts to allay these concerns.

The authors also identify differences between the CEE countries as one of the major challenges to further deepening China’s cooperation in the region. Due to the different conditions across the CEE, it is difficult for China to carry out the same type of activity in each country. They call on China to respect the differences and to consider relevant policies formulated by the CEE countries in order to better inform the intended cooperation. In particular, with regard to its OBOR initiative, China should pay attention to the economic and trade differences in the CEE countries as well as their strengths and weaknesses in order to avoid investment risks.

Building China’s image in Europe

Furthermore, Long suggests that China should establish cooperation on OBOR with the 16 CEE countries in non-economic areas to balance the lack of economic cooperation. For instance, cooperation with the small- and medium-sized CEE countries in the areas of law, culture, education and science might not only win over these countries for further cooperation with China but also increase the visibility of OBOR. Long suggests that China should consider establishing a special financing fund for cultural and educational exchanges. She also suggests strengthening think-tank exchanges, joint conferences and research projects to improve understanding of OBOR in the CEE countries. In addition, there is a need for China to promote its foreign policy rationale and practices, she believes, as well as China’s stance towards global issues. This would help to create an objective public opinion in the CEE countries on China, he argues.

On the official level, the Communist Party of China, which has maintained relations with almost all political parties in the CEE countries, should strengthen inter-party exchanges. But Feng and Song also highlight the importance of the civil and cultural level. They criticise the lack of understanding of China in the CEE countries, which is mainly formed through the Western media, and is therefore often one-sided. In the future, the focus should be on enhancing public understanding of Chinese culture and values, eliminating prejudices among the public, and enhancing China's cultural soft power in the CEE countries. They emphasise that, only by engaging in such efforts, can China gradually eliminate the negative perception many have of it.

Much more than Long, they stress the importance of think-tank exchanges, or what they call “intellectual navigation” (智力导航, zhili daohang). The authors view think-tanks as a combination of power and knowledge that play an important role in informal exchanges between China and the EU, which official channels cannot replace. They note that China and the CEE countries have increased think-tank exchanges in recent years, and held a think-tank roundtable in Beijing September 2012 and in Warsaw in May 2013. Since 2012, the Chinese government has provided around two million yuan each year for a ‘China-Central and Eastern European Relations Research Fund’ to support academic exchanges and cooperation on both sides. However, it is undeniable in their view that those academic exchanges between China and the CEE countries started late, and that quantity, quality, scale and influence are still weak. China’s OBOR initiative could further improve these exchanges, they believe, and thereby also overall relations between China and the CEE countries.

These three authors pay significant attention to China’s image not only in the 16 CEE countries but also in Europe as a whole. They see an urgent need to improve this image and deepen understanding of China’s policies. In this context a fourth author should be mentioned, Liu Zuokui, of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, who also finds that there is lack of mutual understanding and research within the 16+1.[9] Liu identifies unfavourable public opinion and prejudice in Europe towards China’s cooperation format and the OBOR initiative. He urges that negative reports (for instance, warning of China’s geopolitical intentions) by European intellectuals and think-tanks should not be ignored by China – such as ECFR’s “Connectivity Wars” publication.[10]

The 16 CEE countries might indeed benefit more from the 16+1 format than previously, now that China has set up a €10 billion investment fund to finance projects. Whether increased academic and think-tank exchanges will help to improve China’s image in the EU remains to be seen – but there would no doubt be enough content to discuss.

The best of both worlds? CEE’s place in China-Europe economic relations

by Agatha Kratz

This year, as on previous occasions, the 16+1 summit, held in Riga on 5 November 2016, ended with a long list of announcements on infrastructure, industrial and financial investment projects. These showed, as if any reminder were needed, that economic items still rank high on the forum’s agenda.[11] From a Chinese perspective, the central and eastern Europe (CEE) region represents bright economic potential in an otherwise depressed European market and has strategic significance within China’s wider foreign policy plans. Yet, despite China’s acute interest, implementation of Beijing’s China-CEE policy has at times proved challenging.

A brighter spot in Europe

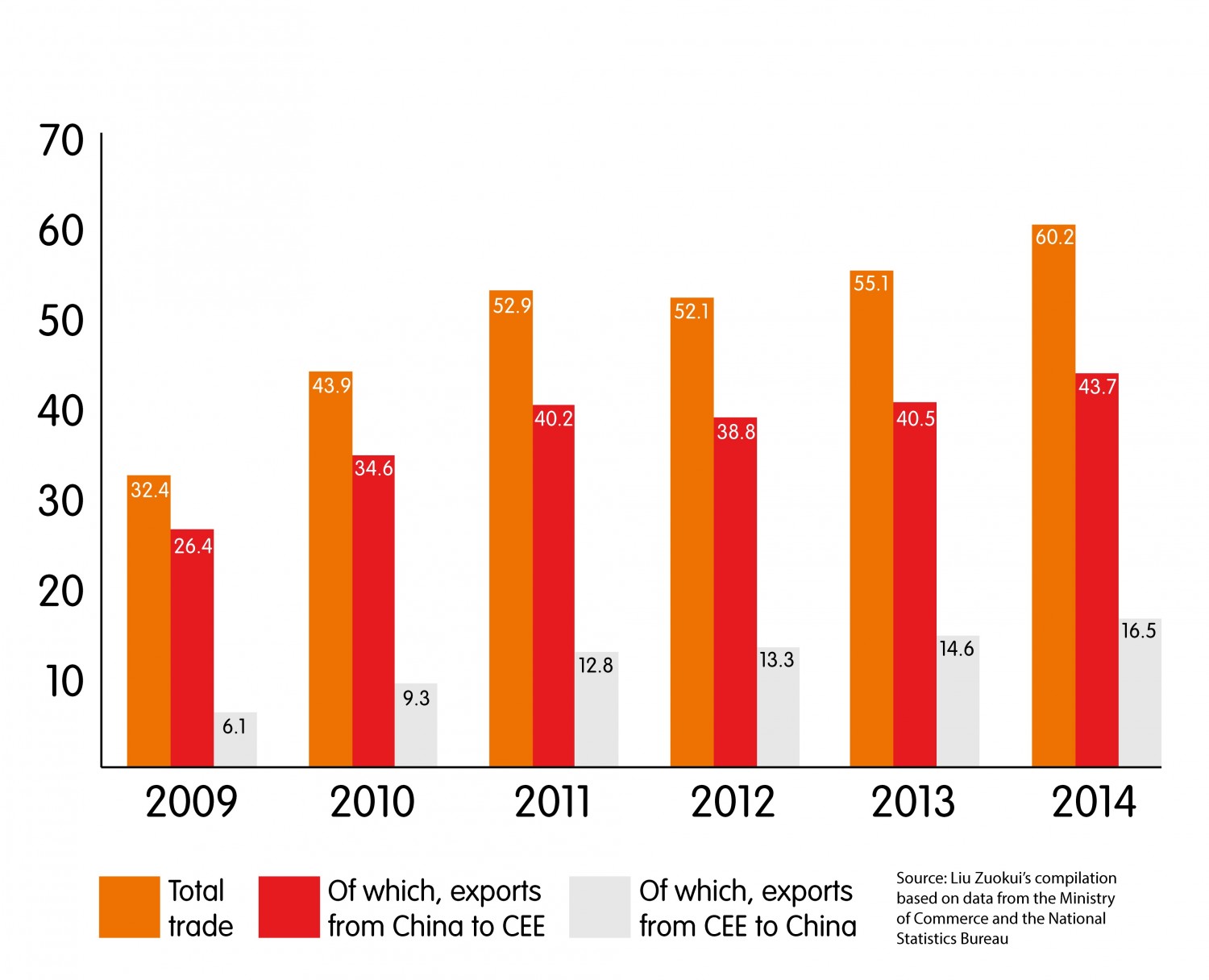

By 2015, the European Union had been China’s main trade partner for 11 years in a row, with CEE countries still representing a relatively small part of this bilateral relationship. Yet CEE countries have become an increasing focus of China’s economic initiatives and overall diplomatic focus towards Europe. Figures provided by Yao Ling,[12] a researcher for the Ministry of Commerce’s research institute on international trade and economic cooperation, show that CEE countries grew to represent 10 percent of China’s trade with Europe in 2014 – up from 9 percent in 2009.

When put in perspective, this one-point growth means more than appearances first suggest. Trade between CEE and China in fact grew much faster than trade between China and the whole of Europe over the period. To illustrate, CEE exports to China grew by a staggering 173 percent over the five years to 2014, almost double the 91 percent increase in exports from the EU to China. Liu Zuokui of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences explains that this increase is, to a large extent, the result of China’s efforts to deal with the fallout for its economy of the 2008 global financial crisis and subsequent European debt crisis.[13] Faced with depressed demand from western Europe, Beijing gradually tilted its attention to CEE.

Starting in 2012 in Warsaw with the first 16+1 meeting, China and CEE countries jointly set up grand plans to reinvigorate and develop bilateral exchanges. This, Liu says, benefited not only Beijing but also CEE countries, by opening up opportunities outside of the troubled EU market on which they had long depended. These efforts quickly paid off. In 2014, CEE-China trade was 86 percent higher than in 2009, says Yao. According to slightly different data cited by Liu, by 2015 bilateral trade between China and CEE countries had reached the target of $100 billion set in Warsaw in 2012.

There is no denying – and Liu and Yao both acknowledge it – that this uptick in trade has been imbalanced (see bar chart). Most of the increase came from a surge in Chinese exports to the region (mostly machinery goods, textiles and raw materials, according to Yao). CEE trade to China, meanwhile, increased, but to a smaller extent in absolute value. As a result, the annual CEE trade deficit with China grew by about 34 percent over the period. The trend was also geographically uneven. According to Yao, just five countries out of the 16 – Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia and Romania – constituted about 80 percent of these exchanges.

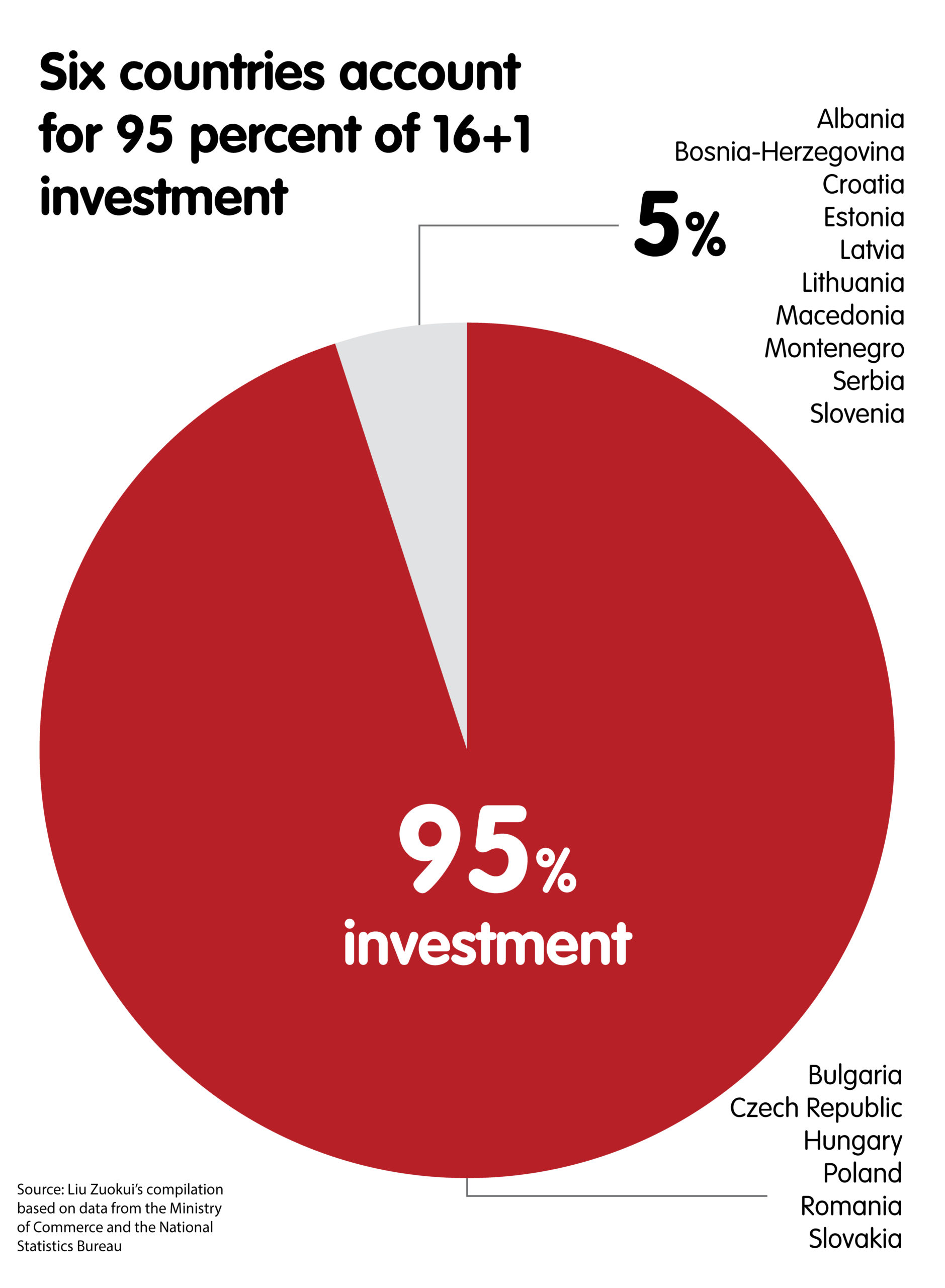

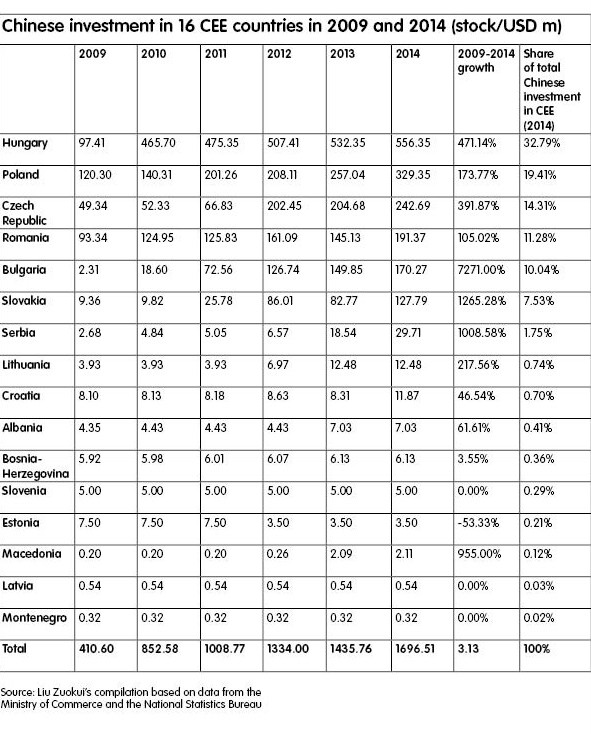

Chinese investment into the region has also increased significantly since the global financial crisis. According to data presented by Liu, China’s outward foreign direct investments into the 16 CEE countries rose from about $400 million in 2009 to about $1.7 billion in 2014 (see Annex). Here again, flows were geographically concentrated, with Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia taking 95 percent of the total in 2014 (see pie chart).

Chinese investment into the region has also increased significantly since the global financial crisis. According to data presented by Liu, China’s outward foreign direct investments into the 16 CEE countries rose from about $400 million in 2009 to about $1.7 billion in 2014 (see Annex). Here again, flows were geographically concentrated, with Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia taking 95 percent of the total in 2014 (see pie chart).

While greenfield investment – a form of foreign direct investment in which a parent company builds its operations in a foreign country from the ground up – still represent a large part of China’s investments in the region, Liu notes that the number of mergers and acquisitions, IPOs and construction projects have also multiplied, marking a diversification of China’s presence. As a result of China’s support to its One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative, projects involving the construction or upgrade of railway lines, highways, ports, or other infrastructure have grown quickly, especially in the Balkan peninsula. But Liu notes that China’s investment is also concerned with a wide range of industrial and service sectors, including manufacturing, clean energy, and tourism.

Of late, China’s economic engagement has also gone beyond classic trade and investment patterns. For example, China worked closely with Hungary to promote renminbi internationalisation. In September 2013, the People’s Bank of China signed a 10 billion yuan currency swap with the country. In 2014, the Bank of China opened its first branch in Hungary, tasked with lending to local companies hoping to trade with and invest in China (potentially directly in renminbi). And, in 2015, Hungary purchased Chinese sovereign debt. These types of agreement have pushed cooperation with China one step further, and onto an institutional level.[14]

A natural hub in China’s European policy

On the whole, Liu notes that the CEE region has become more important and more strategic within the EU-China relationship, and will likely continue to grow as such. Both Yao and Liu explain that China’s CEE investment and trade rationale is clear: the region displays a perfect mix of strategic geographical positioning, high-skilled yet cheap labour, open trade and investment attitudes, good logistics platforms, and positive capital and industrial investment opportunities. Besides, it is just one step away from the high-tech and lucrative western EU market. As such, it presents an attractive prospect for Chinese companies.

Describing the increase in China-CEE exchanges, Liu concludes that it cannot be disconnected from China’s flagship foreign policy endeavour, OBOR. Indeed, CEE fits nicely into China’s grand plan for enhanced Eurasian connectivity. For Liu, it represents a hub, and a pathway between Asia’s dynamism and Europe’s high level of development. CEE sits right between the Mediterranean end of the ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ (practically, the 51 percent Chinese-owned port of Piraeus in Greece) and Europe’s highly attractive inland market.

This, Liu says, explains why Chinese premier Li Keqiang, visiting Europe in December 2014, pushed for a multi-party agreement with Macedonia, Serbia and Hungary to set up a ‘China-Europe Land-Sea Express’ (中欧陆海快线, Zhong’ou luhai kuaixian), the objective of which would be to facilitate the shipping of goods from Greece to Hungary (and further on to western Europe) through infrastructure development. Since then, many other large infrastructure projects have been championed, such as the ‘three-sea harbour district cooperation initiative’ proposed by the premier in Suzhou, aimed at fostering Sino-CEE cooperation in the construction of ports and logistics parks throughout the whole region.

A hard-won piece of the European cake

China’s interest in the region is genuine, Liu says, and OBOR in particular is a “jointly discussed, jointly established and jointly shared” (共商,共建,共享, gongshang, gongjian, gongxiang) initiative. But he acknowledges a number of remaining barriers to China’s plans for the CEE region.

One barrier is that the interests of China and CEE countries can at times prove somewhat misaligned. Liu notes, for example, that beyond mutual development and connectivity, China’s charm offensive towards CEE countries responds to clear domestic imperatives on the part of China, such as reducing excess capacity and increasing trade with Europe as a whole. Pursuing these objectives can create imbalances in the relationship, particularly in the area of trade. Yao nevertheless believes the relationship can be mutually beneficial, given the promising nature of CEE export potential to China. For example, he notes, quality regional agricultural and food products such as beef and lamb, dairy products, or wine are in great demand in China. Yet he believes more could be done to balance the bilateral trade relation, and boost CEE-China exchanges, through, for example, a simplification and easing of customs procedures, or the creation of a region-wide appellation that would help build a CEE brand within the Chinese market.

Another barrier cited by Liu pertains to Chinese investments in the region. While Chinese companies are usually interested in buying out companies in order to penetrate the European market, acquire technologies, and assimilate advanced management skills (all working towards the upgrade of China’s economy), CEE countries are more concerned with boosting local employment and economies, and might thus favour greenfield projects. Besides, in their own development path, these countries’ emphasis is on sustainable employment, social safeguards and democratic governance. On the other hand, China’s view of development is rather a matter of economic cooperation and integration of global economic resources. These divergences, of course, vary depending on the target country. While Liu points to the highly defensive attitude on the part of Poland towards China’s endeavours in the region, Gao Chao explains that Hungary has shown continuous eagerness to integrate China’s initiatives.

A further set of difficulties relates to incompatibilities between China’s initiatives and EU regulations. Quite controversially, Liu calls the ongoing ‘Berlin process’, a German-led intergovernmental initiative to support the EU integration process, a way of using EU regulation to restrict Chinese presence and actions – and preserve the EU’s influence – in the Balkan region. But more generally, Chinese financing for large projects in the CEE region often runs up against EU rules. For example, a proposed $10 billion financing scheme by China remains restricted by parts of the EU’s stability and growth pact. Indeed, Chinese demands for sovereign guarantees for preferential credit often run counter to (what Liu considers exaggeratedly low) limits on member states’ overall level of public indebtedness. As a result, a number of EU countries cannot subscribe to such China-dedicated financing schemes.

A final obstacle to increased economic cooperation comes from the negative perception that often surrounds Chinese engagement with CEE countries. Often, Liu explains, China is depicted as trying to divide and rule a region where countless powers are fighting for their own interest (Russia, the EU, Germany). He also acknowledges the security unease that some Chinese investment can provoke in host countries. He thus recognises China’s need to build a stronger and more positive brand image in the region.[15]

Forging ahead with the 16+1, and with Brussels

Nevertheless, all authors call for even more economic cooperation between the two parties than there is currently. Interests on both sides, they say, can certainly be reconciled – and further rapprochement would benefit both China and CEE countries. In this process, the 16+1 forum has a particular role to play. As Liu explains, it institutionalises a new form of Chinese cooperation with the world, namely “a regional model of cooperation” (区域合作模式, quyu hezuo moshi). It complements and reinforces China-EU cooperation and relations, while providing a consultation mechanism for China’s economic projects for the region. To be successful, says Liu, the 16+1 should thus be an open platform on the same model as OBOR, and as diverse a mechanism as possible, including initiatives at the national and local, official and business-oriented level.

Interestingly, in both Yao’s and Liu’s view, the EU has an important role to play in the CEE-China relationship. Thanks to its own competitive advantage, China can respond to the European Commission’s Investment Plan, and the EU’s wider objective of boosting economic growth and employment, by providing its operational experience in building and financing infrastructure, or by investing in equipment manufacturing or distribution channels in the CEE region.

When the Silk Road meets the EU: towards a new era of Poland-China Relations?

by Justyna Szczudlik

In 2015, China certainly noticed the changing of the guard that took place through Poland's presidential and general elections. The winner, the conservative opposition party, Law and Justice, secured an absolute majority and established a non-coalition government. Under the previous government led by the liberal and centrist Civic Platform, relations with China improved remarkably. As Liu Zuokui of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences argues, this was especially noticeable during Donald Tusk’s second term as prime minister,[16] while in 2011 bilateral ties were upgraded to the ‘strategic partnership’.

For China, the elections supposedly introduced an element of uncertainty about the future of Sino-Polish relations. An indirect question appeared around whether the previous strategic partnership policy would continue. Mao Yinhui of the Guangdong University of Foreign Studies describes Law and Justice as a right-wing, populist, pro-Catholic, nationalistic and Eurosceptic party, and says that the idea of the ‘China threat’ is still periodically evident in Poland.[17] Liu emphasises the point that the party advocates an anti-communist approach.

These concerns were assuaged by the new Polish government’s first year in office, which saw intensive political dialogue in the form of President Andrzej Duda’s visit to China in November 2015, President Xi Jinping’s visit to Poland the following June, and the elevation of ties to the level of ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’. Both Liu and Mao argue that the Polish government has pursued a more active policy towards China (对中国的态度显得更为积极, dui zhongguo de taidu xiande geng wei jiji) and that Sino-Polish relations have entered into a new era (中波关系步入了新的时代, zhongbo guanxi rujinle xinde shidai) or level of cooperation (中波合作迈向新的台阶, zhongbo hezuo maixiang xinde taijie). This positive assessment relates not only to Poland’s China policy as such. Experts argue that ongoing changes in Poland’s diplomatic agenda as well as crises in the European Union and the neighbourhood mean there is potential for China to take a bigger role in its bilateral relations with Poland.

Poland as a new European ‘star’

In China, Poland’s development is viewed as a success story. Liu argues that Poland is a new European political and economic ‘star’ (明星, mingxing). He cites the economic growth that Poland has enjoyed in spite of the global financial crisis (and he compares Poland with Ukraine, highlighting the huge development discrepancies between two countries) that encouraged Poland to try to become a G20 member. Liu also cites Tusk’s appointment as president of the European Council, a development seen as confirmation of Poland’s decisive role (举足轻重的力量, juzu qingzhong de liliang) in Europe. China has acknowledged Poland’s success by strengthening bilateral relations but also setting up a new regional cooperation format. During Chinese premier Wen Jiabao’s visit to Poland in April 2012, the 16+1 grouping of China and 16 central and eastern European countries was established. The first summit was held in Warsaw.

Polish foreign policy adjustment – an opportunity for China

Liu argues that Poland's foreign policy priorities have not changed under the new Law and Justice government.[18] These priorities are: a strong Poland within Europe; a focus on transatlantic relations and the role of NATO as a security guarantor; amicable relations with neighbours; and upgrading Poland’s status internationally. Liu also points out that, despite the fact that Poland-China relations are blossoming, China is not considered to be a top priority in the Polish diplomatic agenda. But this approach is likely to change as Polish foreign policy is progressively adjusting (调整, tiaozheng). Mao Yinhui shares Liu’s opinion, saying that, since 2015, a change in Polish foreign policy has been clear (明显, mingxian). Both experts believe that this approach creates more space for China and closer Sino-Polish relations.

Liu describes Poland’s foreign policy as “leaning towards the east” (“东向”倾斜, “dong xiang” qingxie). Reasons for this eastward turn include new and existing problems facing Poland. Liu points to tensions with the EU after its official warning over changes to Poland’s constitutional court, the Polish government’s views on the migration crisis which diverge from thsoe of other member states, the weaker role of the ‘Weimar triangle’ (Poland, Germany and France), and the ongoing Ukrainian crisis. What is more, Poland would like to gain a stronger position in the EU, and in that sense Warsaw is seeking closer ties beyond Europe and transatlantic relations. This approach may help Poland overcome the influence exerted by the bigger and older EU members which set the tone in the EU. In the case of the economy, Mao argues that 60 percent of Polish trade is conducted within Europe. But due to the EU's recent economic travails, Poland is concerned about economic overdependence on Europe. For this reason the Polish government is looking for new markets and sources of capital, such as in Asia. In this context, Liu highlights the sanctions that Russia has imposed on Poland, which have seriously limited Polish exports.

Mao Yinhui presents similar arguments to Liu’s. She emphasises the domestic and foreign rationales behind changes to Polish foreign policy. Domestic ones include Law and Justice’s Eurosceptic mindset (疑欧主义, yi’ou zhuyi), which, she says, manifests itself in advocacy for EU reforms which would decrease role of Germany and France as the main forces in the EU. She also argues that Polish foreign policy changes have been driven by three crises: debt in the EU, the situation in Ukraine, and the migration crisis. She indicates that the EU crises raised doubts in Poland about the EU project, resulted in weaker relations with Brussels, and specifically with Germany and France, and reinvigorated Visegrád Group cooperation. While the situation in Ukraine has enhanced Poland’s concerns about security, namely the threat from Russia, aforementioned circumstances have seen the Polish government focus on security and strengthening relations with the United States and NATO. Both Liu and Mao believe these factors may lead Poland to forge closer relations with China.

Challenges for Sino-Polish ties

Both experts outline the motivations behind Poland’s active policy towards China. They argue that Poland as a big country seeks closer cooperation with another big country – China. Better relations with China may upgrade Poland’s position in the EU and globally. But economic reasons are at the core. Mao presents three main Polish interests in strengthening relations with China: expanding exports, narrowing a huge trade deficit, and attracting investment. These rationales lie behind Poland’s active participation in the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (Mao underscores that Poland is the only founding AIIB member from central and eastern Europe), and cooperation in the 16+1 framework.

Liu underlines the Polish government’s very positive mindset about relations with China. Apart from the visits of the two presidents in 2015-16, Liu quotes Polish minister of foreign affairs, Witold Waszczykowski’s speech, delivered in January, in which he explicitly mentioned the OBOR initiative and the AIIB as opportunities for Poland. While visiting China in April 2016, Waszczykowski – as Mao quotes – stressed that Poland seeks good relations with the world’s second biggest economy and that it is conscious of the shift to Asia of the global economic activity which will requires Polish foreign policy to adjust. Liu also presents cooperation platforms and mechanisms in bilateral relations as a vindication of the multidimensional character of Poland-China relations (多种合作平台和机制, duozhong hezuo pingtai he jizhi). He mentions bilateral levels of cooperation, including at the local tier such as cooperation between local government, at subregional level through the 16+1, and the EU level.

Although relations are flourishing, Chinese experts raise several challenges. Liu Zuokui lists three of them. The first includes barriers erected by the US and the domestic opposition. He calls this approach Poland’s “twofold policy towards China” (波兰对华政策存在两面性, bolan duihua zhengce cunzai liangmianxing). This means that the Polish government on the one hand strives for close relations with China but at the same time needs to deal with constraints from the US and domestic opposition to closer ties with China. Second, a serious limit also comes from ideology or differences in values. As a result of Poland trying to maintain this sort of balance, its policy is sometimes inconsistent. The second negative factor is a huge negative trade balance on Polish side. He says that in 2015 China was Poland’s biggest source of a trade deficit (2015年波兰第一大逆差来源地是中国, 2015 nian bolan diyi da niche laiyuandi shi zhongguo). He also mentions the biggest problems with Polish exports to China, such as a Chinese ban on Polish pork, problems with obtaining export certificates for food or agricultural projects (eg. apples), and an export structure which is not beneficial for Poland. The third negative factor indicates strategic differences (战略对接, zhanlüe duijie) between the two sides. China is not the focus of Polish foreign policy. Instead, Poland pays more attention to the situation in the region such as the migration crisis, cooperation with eastern partners and Visegrád countries. Under these circumstances it is difficult to find commonalities (难有交集, nanyou jiaoji) between the two countries.

A slightly different set of challenges is raised by Mao. She points to the concerns in Poland about the real reasons for OBOR. She says that some hold the view that the Silk Road is just a beautiful or gorgeous “package” (华丽的“包装”, huali de “baozhuang”) while its real goal is political – to raise China to superpower status (超级大国, chaoji daguo), and build a new China-led international order. Mao also indicates that Poland is concerned about the lack of benefit coming from OBOR due to rivalry between states for Chinese attention. The second challenge includes contradictions between Poland’s relations with China, the US and Russia (波兰对中, 美, 俄大国关系存在矛盾心理, bolan dui zhong, mei, e daguo guanxi cunzai maodun xinli) taking into account the context of China’s ties with those great powers. China has good relations with Russia and there are many existing and emerging tensions with the US. But Poland's attitude to the US and Russia is quite different from that of China. This creates uncertainty for Sino-Polish relations (中波关系未来发展带来不确定性, zhongbo guanxi weilai fazhan dailai buquedingxing).

On the South China Sea disputes, Mao wrongfully relates that Waszczykowski declared Poland’s support for China’s stance on the South China Sea during his visit in April 2016. In reality, he only said that “Poland calls for peaceful solutions of the dispute through dialogue and consultations” (波方支持中方通过对话协商和平解决有关南沙岛礁争议的政策, bolan zhichi zhongfang tongguo duihua xieshang heping jiejue youguan Nansha daojiao zhengyi de zhengce).[19] However, Mao notes that there is a range of opinions in Poland over this issue, in part to do with concerns about undermining relations with the US. There are also concerns in Poland that close China-Russia relations will be harmful for Polish interests. Finally, Mao says that, despite the fact that China’s image in Poland has improved and Poland envies China’s rapid development (波兰对中国的快速发展心存羡慕, bolan dui zhongguo de kuaisu fazhan xincun xianmu), Warsaw remains cautious (不无警惕, buwu jingti) about China. Mao recommends more people-to-people contact, diversification of information exchange channels and better use of Chinese soft power. She believes that those means may help to enhance mutual trust and understanding.

The geoeconomics of Sino-Serbian relations: The view from China

by Dragan Pavlićević

Serbia has long been one of China’s leading partners in Europe, playing a particularly prominent role within the so-called 16+1, China’s multilateral mechanism with 16 countries of central and eastern Europe (CEE). According to Li Manchang, the Chinese ambassador to Serbia, the 16+1 platform has been occasionally, and only semi-jokingly, referred to as 15+1+1, due to the high number of agreements and projects agreed upon and implemented by China and Serbia over recent years.[20] During President Xi Jinping’s visit to Serbia in June 2016, the two countries elevated their relationship to the status of comprehensive strategic partnership. The recent introduction of a bilateral visa-free entry regime for visits lasting up to one month, signed among a raft of other bilateral agreements during the fifth China-Central and Eastern Europe Summit in Riga in November 2016, also illustrated the strong ties between the two. The visa regime with China is the first of its kind for any European country.

As will become clear, several considerations shape Chinese thinking towards Serbia. First, is the positive perception of China in Serbia, which rests on a solid historical relationship. Second, Serbia is supportive of China’s stance on several foreign policy issues which Beijing perceives as its “core interests”. Third, there is a perceived match between Serbia’s development needs on the one hand and China’s resources and its objectives in its economic diplomacy on the other. And, finally, Serbia is seen as an important and willing partner for China’s key foreign policy schemes: the 16+1, ‘One Belt, One Road’, and ‘Going out’ initiatives.

Serbia has China’s back

According to Chinese officials and commentators, the basis of the relationship is a traditional friendship between the two governments and peoples. One editorial in the Southern Weekly this year argued that the Sino-Serbian relationship is based on the mutual affection of two peoples towards each other.[21] Marking the occasion of his visit to Serbia with an op-ed for Serbian newspaper Politika, President Xi argued that: “Over the last 60 years, the two peoples have always been united (心手相连, xinshouxianglian) in each other’s special feelings for each other and true friendship across time and space”[22] – words highlighted by journalist Wan Peng, writing in International Development Cooperation (国际援助, Guoji yuanzhu). The traumatic experience of the United States’ bombardment of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade during the NATO campaign against Serbia in 1999 further strengthened the relationship.[23]

Liu Zuokui, of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, adds that Serbia admires China's development achievements, development ideas and development path, and intends to draw on the successful experience of China's reform and development. An important facet of this friendship is also the two countries’ sustained respect for what the other regards as its core interests. Liu argues that on issues such as human rights, the South China Sea, capacity cooperation and market economy status, Serbia’s position is to support China's stance and interests.[24] He adds that in the light of some EU member states’ differences with China on these issues, Serbia's position is particularly valuable to Beijing. Liu also notes that on the issues related to Taiwan, Xinjiang and Tibet, Serbia “also resolutely safeguards China’s position”.[25] This is mirrored by China’s support to Serbia in relation to its own “core interests” and objectives, including the diplomatic battle to protect its sovereignty over Kosovo.

Both Liu and Wan stress the importance of the 16+1 framework for the Sino-Serbian relationship, and as an important platform for further deepening of bilateral ties. Wan states that China and the CEE region are both similar and complementary, the former being the biggest developing country in the world and the latter amounting to an important and growing emerging market. He also notes that the developing China-CEE relations have the potential to advance the state of the Sino-EU relations, of which they, of course, form an important part.

Liu – one of the most authoritative sources on what China thinks about Serbia – places the Sino-Serbian relationship firmly in the context of the global shift of power. In 2009, reacting to the changes taking place in the 21st century and the rise of China as the future economic leader in the world, Serbia established the development of a strategic relationship with China as one of the main goals of its diplomacy. According to Liu, the global financial crisis laid the ground for further deepening of the Sino-Serbian ties, as it impelled Serbia to look for alternative ways to assist its economy. While in 2014 trade and investment inflows from the EU still accounted for 63.8 percent and 90 percent respectively of Serbia’s total, the EU’s own economic resources have been strained in the aftermath of the crisis. Hence, Serbia views China as a responsible daguo (大国) – a responsible big country – which at a time of difficulty for the Serbian economy gives hope of recovery.

Opportunities and challenges for Chinese investment in Serbia

Gao Chao, a journalist at China Foreign Trade (中国对外贸易, Zhongguo duiwai maoyi), identifies the economic opportunities on the Chinese side. According to Gao, Serbia occupies a geographically important position, at the crossroads of the EU, south-east Europe and Asia, making it a key logistics node for air, rail, road, and water transportation. This also makes Serbia a potentially valuable component of China’s One Belt, One Road initiative (OBOR).[26] Liu echoes this assessment, noting Serbia’s enthusiasm to participate actively in the scheme.[27] China can further capitalise on this advantageous geographical position by taking part in the delivery of a number of planned projects. These include developing the network of transport links that will not only connect Serbia to various logistic and commercial centres in central and south-east Europe but which will also facilitate transport and trade flows from and to western Asia and North Africa.

Excellent opportunities await Chinese investors in infrastructure, energy, agriculture, communication technologies, and tourism, suggests Gao. The opening for Chinese enterprises lies particularly in the perceived lack of finance and expertise within Serbia to develop these sectors all while the country “energetically pushes forward developmental projects”. Zhu Lianqi, counsellor for economic affairs at the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, notes that the combined value of four joint infrastructure projects in Serbia is already higher than with any other CEE country. He sees the development of the high-speed railway line between Serbia and Hungary as an important step forward in the relationship. Zhu makes the same assessment of the recent acquisition of Smederevo steel mill, one of Serbia’s most important industrial assets, by Hesteel – a major state-owned Chinese iron and steel manufacturing conglomerate. In the same context, Gao particularly emphasises that Serbia is in need of an estimated €9-10 billion over the next 10 years to improve its basic infrastructure.

Further incentives to Chinese investors include the high supply of skilled labour, whose costs are comparatively low, and government subsidies and other sorts of preferential policies which encourage foreign investors to set up their manufacturing and commercial operations in Serbia. And, thanks to Serbia enjoying preferential trade agreements with the neighbouring countries, the EU, Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Turkey, Zhu further identifies this tax-free access to a market of approximately 800 million people as an excellent opportunity for Chinese enterprises.

However, Chinese observers also pay attention to the risks. Liu points out that Serbia’s domestic laws and regulations are still “not perfect” (健全, jianquan), and that many standards are not “as strict and clear as the EU standards”. He urges China to strengthen market research and pay attention to investment risks in order to prevent investment failures. Liu further notes that there are segments of Serbian society which do not look favourably on China’s development model and its basis on cheap labour, and are under the impression that China engages Serbia not to “help” but to “make money”. He also expresses dissatisfaction with the volume and structure of bilateral trade, which is still moderate, at $550 million in 2015, and heavily unbalanced, with Chinese exports to Serbia accounting for $420 million.[28]

Zhu states that Chinese investors in Serbia currently face a range of issues, including an unstable market, low investment returns, and no corresponding guarantees, all of which hinder Chinese enterprises’ activity in the Serbian economy. The key challenge for Chinese enterprises for business development, according to Zhu, is how to find the best model of cooperation to pool together the existing technology, equipment, construction and financial resources, and achieve win-win cooperation for both parties, and even third parties. This reflects China’s interest in capacity cooperation[29] where China and the EU would pool together resources such as finances and expertise and jointly deliver projects in Serbia.[30] In terms of infrastructure projects, Zhu notes that that the Serbian government is subject to financial constraints due to high fiscal deficits, foreign debt and public debt levels, as well as conditions associated with the EU membership accession process. The government will strictly control new sovereign lending and financial guarantees over the next few years, something which will require Chinese companies to adapt. According to Zhu, this adaptation will need to come from a move away from a reliance on Chinese state loans to Chinese enterprises actively exploring new ways of approaching potential projects in Serbia. Alternative models, such as franchising, leasing, and direct investment should be explored if further projects in Serbia are to be secured.

Taken together, Liu and Zhu urge the Chinese government and Chinese enterprises to base their activity on: the foundations of the existing strategic partnership (namely, the 16+1 and OBOR platforms); entrepreneurialism combined with sound risk management practices; and a deepening of people-to-people exchange to maintain momentum and further extend cooperation. If followed through, this approach is likely to be enthusiastically received by Serbia which, for its part, appreciates China’s support on the issue of the secession of Kosovo – and wants to pursue its own domestic and international objectives though closer cooperation with China.[31]

FOOTNOTES

[1] For instance, mentioned in the European Parliament Briefing on ‘One Belt, One Road (OBOR)’, July 2016, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2016/586608/EPRS_BRI(2016)586608_EN.pdf.

[2] Robin Emmott, ‘EU’s statement on South China Sea reflects divisions’, Reuters, 15 July 2016, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-southchinasea-ruling-eu-idUSKCN0ZV1TS.

[3] EU member states: Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia. Non-EU member states: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia.

[4] For more details on these guidelines, see: http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1224905.shtml and http://gov.ro/en/news/the-bucharest-guidelines-for-cooperation-between-china-and-central-and-eastern-european-countries.

[5] Long Jing, “Opportunities and Challenges of the Belt and Road Initiative in Central and Eastern Europe”, (‘一带一路’倡议在中东欧地区的机遇和挑战, Yidai yilu changyi zai zhongdongou diqu de jiyu he tiaozhan), Guoji guancha, N°3, 2016, 118-130. Long Jing is assistant research fellow at Shanghai Institutes for International Studies.

[6] For more details on the Sino-Serbian relations, see Dragan Pavlicevic’s article in this issue.

[7] Feng Min and Song Caiping, “Developing the relationship between China and Central and Eastern European countries by using OBOR” (运用’一带一路’发展中国与中东欧关系对策, yunyong ‘Yidai yilu’ fazhan Zhongguo yu zhongdongou guanxi duice), Jingji wenti, N°1, 2016, pp.26-29.

[8] See http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/china/docs/eu-china_2020_strategic_agenda_en.pdf.

[9] Liu Zuokui, “The One Belt One Road initiative in the context of the 16+1 Cooperation”, (一带一路倡议背景下的”16+1合作”, Yidai yilu changyi beijing xia de 16+1 hezuo), Dangdai Shijie Yu Shihui Zhuyi, n°3, 2016. Liu Zuokui is director of the Department of Central and Eastern European Studies in the Institute of European Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) and director of the Secretariat Office of the “16+1 Think-Tank Network” in CASS.

[10] Mark Leonard (ed), “Connectivity Wars: Why migration, finance and trade are the geo-economic battlegrounds of the future”, ECFR, 2016

[11] For more information on the Summit and subsequent declarations/announcement, see: http://www.mfa.gov.lv/en/policy/multilateral-relations/cooperation-between-central-and-eastern-european-countries-and-china.

[12] Yao Ling, “Background research on the current state of trade cooperation and development prospects between China and CEE countries”, (中国与中东欧国家经贸合作现状及发展前景研究, Zhongguo yu zhongdongou guojia jingmao hezuo xianzhuang ji fazhan qianjing yanjiu), Guoji Maoyi, n°3, 2016.

[13] Liu Zuokui, “The One Belt One Road initiative in the context of the 16+1 Cooperation” (一带一路倡议背景下的”16+1合作”, Yidai yilu changyi beijing xia de 16+1 hezuo), Dangdai Shijie Yu Shihui Zhuyi, n°3, 2016. Liu Zuokui is director of the Department of Central and Eastern European Studies in the Institute of European Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) and director of the Secretariat Office of the “16+1 Think-Tank Network” in CASS.

[14] Gao Chao, “The Hungarian investment opportunity within ‘One Belt, One Road’s establishment” (“一带一路” 建设中匈牙利的投资机遇, “Yidai yilu” jianshe zhong Xiongyali de touzi jiyu), Zhongguo Duiwai Maoyi, January 2016.

[15] On the question of China’s image branding in the region, see Angela Stanzel’s article in this issue.

[16] Liu Zuokui, “Directions of Polish Foreign Policy and Poland-China Relations” (波兰的外交政策走向与中波关系, Bolan de waijiao zhengce zouxiang yu zhongbo guanxi), Zhongguo yu shijie, 2016. Liu Zuokui is director of the Department of Central and Eastern European Studies in the Institute of European Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) and director of the Secretariat Office of the “16+1 Think-Tank Network” in CASS.

[17] Mao Yinhui, “Changes in Poland’s Foreign Relations and Opportunities and Challenges in Poland-China Ties” (波兰对外关系的变化及中波关系的机遇与挑战, Bolan duiwai guanxi de bianhua ji zhongbo de juyu yu tiaozhan), Xiandai Guoji Guanxi, 2016. Mao Yinhui is director of the Polish Language Department, Faculty of European Language and Culture, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies.

[18] Liu Zuokui, “Directions of Polish Foreign Policy and Poland-China Relations”

[19] The incorrect popular conviction in China about Poland’s opinion stems from the title given by Xinhua agency to the article about the meeting between Waszczykowski and Wang Yi. The title was “Poland supports China’s stance on the South China Sea” (波兰支持中国南海立场, bolan zhichi Zhongguo Nanhai lichang).

[20] Li Manchang “[Serbia has reached] Highest number of agreements with China, other countries [within 16+1] are jealous” (Li Mančang: Najviše Sporazuma sa Srbijom, Drugi Ljubomorni), Politika, 5 November 2016. Available at: http://www.politika.rs/scc/clanak/367192/Li-Mancang-Najvise-sporazuma-sa-Srbijom-drugi-ljubomorni.

[21] “Pushing the Sino-Serbian Sino-Serbian Strategic Partnership to new heights” (把中塞战略伙伴关系推向新高度, ba zhongsai zhanlue huoban guanxi tuixiang xin gaodu), Southern Weekly, 20 June 2016.

[22] Wan Peng, “Looking at how to draw the blueprint for the ‘16+1’ on the basis of Xi Jinping’s op-ed articles in Serbia and Poland” (从习近平在塞波两国署名文章看 “16+1 合作”蓝图如何绘就, cong Xi Jinping zai sai bo liang guo zhuming wenzhang kan “16+1 hezuo” lantu ruhe huijiu), Guoji Yuanzhu, July 2016, pp. 22-23. Wan Peng is a journalist for the People’s Daily website.

[23] Liu Zuokui, “Serbia’s domestic trends, foreign policy direction and Sino-Serbian relations” (塞尔维亚国内形势、外交政策走向与中塞关系, Saierweiya guonei xingshi, waijiao zhengce zouxiang yu zhongsai guanxi), Dangdai Shijie, September 2016, pp. 32-35. Hereafter, Liu, “Serbia’s domestic trends, foreign policy direction and Sino-Serbian relations.”

[24] For capacity cooperation, please see: Qiu Zhibo, “The ‘Triple Win’: Beijing’s Blueprint for International Industrial Capacity Cooperation”, China Brief, Volume 15, Issue 18 (September 2015). Available at: https://jamestown.org/program/the-triple-win-beijings-blueprint-for-international-industrial-capacity-cooperation/#sthash.6PsUzf15.dpuf.

[25] Liu, “Serbia’s domestic trends, foreign policy direction and Sino-Serbian relations.”

[26] Gao Chao, “Constructing “One Belt, One Road” bring about investment opportunities in Serbia” (‘一带一路‘建设中塞尔维亚投资机遇,“Yi dai, yi lu” jianshe zhong saierweiya touzi jiyu), Zhongguo duiwai maoyi, February 2016, pp. 78-79.

[27] Liu, “Serbia’s domestic trends, foreign policy direction and Sino-Serbian relations.”

[28] Liu, “Serbia’s domestic trends, foreign policy direction and Sino-Serbian relations.”

[29] Please see footnote 5 on page 13 for more on capacity cooperation.

[30] Zhu Lianqi, “Timely innovative thinking writes new chapter in the cooperation in the Sino-Serbian economic and trade cooperation” (创新思维与时俱进再谱中塞经贸合作新篇章, chuangxin siwei yu shi jujin zai puzhong zhongsai jingmao hezuo xin bianzhang), Guoji Yuanzhu, July 2016, pp. 90-91.

[31] For more details, see: Agatha Kratz and Dragan Pavlićević, “Belgrade-Budapest via Beijing: A case study of Chinese investment in Europe” (ECFR). It can be accessed here: https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_belgrade_budapest_via_beijing_a_case_study_of_chinese_7188.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.