Winning the normative war with Russia: An EU-Russia Power Audit

Summary

- The EU and Russia have become locked in an open battle over the norms of international conduct. This is a clash between liberal universalism and authoritarian statism; the liberal international order and realpolitik.

- Russia’s interference in European internal affairs is one front line in this normative battle – Moscow’s attempt to erode the Western liberal consensus from within.

- Russia supports anti-establishment forces in Europe because it lacks friends among establishments. Its use of unconventional methods is not a demonstration of creative strategy but an attempt to compensate for deficiencies.

- EU member states are remarkably united in their assessment of Russia, but they still need to translate this unity into a political strategy that reflects not just European values, but also Russian realities.

- The path to winning the overall normative war will not go so much through countering Russia as through improving Europe’s resilience and reinvigorating the Western model.

Introduction

Two recent images from the 2017 French election capture the current EU-Russia relationship. The first, from 24 March, shows Russian President Vladimir Putin receiving French presidential candidate Marine Le Pen in the Kremlin. With a smile, Putin approvingly declared that the far-right Le Pen represented a range of political forces gaining momentum across Europe. This meeting epitomised Europe’s darkest fears: the European project drowning in a nationalist-populist tsunami cheered on by the Kremlin.

The second image, however, shows Europe’s resilience despite these fears. Just two months later, Putin stood uncomfortably in the Palace of Versailles next to Emmanuel Macron, the new pro-European French president who had just defeated Le Pen. Macron stated bluntly that Russian propaganda channels had spread false information during the election, but he did so in a matter-of-fact manner, without succumbing to the hysteria that so often characterises Western discussions on Russia in general and its meddling in particular. The French government had elegantly ignored a hacking attack on the eve of the election and Macron prevailed anyway. Looking at Putin’s impenetrable expression, one could almost hear his unspoken message: “Chapeau! You have won this round. But there will be more.”

These two meetings show both the highs and the lows of Europe’s current struggle with Russia. Since Russia’s annexation of Crimea and invasion of eastern Ukraine in 2014, the EU and Russia have become locked in an open battle over the norms of international conduct. They disagree on some of the most fundamental normative elements of the post-cold war international order – its Western-led “unipolar” nature; its emphasis on human rights and democracy; and the idea that countries have the right to choose their own alliances and join once they qualify. It is normative war, and neither side is ready to retreat.

Domestic politics in Europe has become one of the front lines in this struggle. Moscow makes use of forces inside Europe that might erode the EU’s confidence and position. But these efforts, while state-approved in the broadest sense, do not necessarily amount to well-coordinated and meticulously planned operations with concrete political aims. Insiders confess that such operations often come from disparate agents of Moscow doing their routine work, and soldiers of fortune trying their luck in an improvised, ad hoc manner. Europeans need to be aware of such attempts, but obsessive attention to Russian efforts might prove counterproductive: it could lead to fighting raindrops instead of fixing the roof.

The French experience shows the path. Thanks to Russia’s earlier interference in Germany and the United States, the French government knew what to expect. It kept an eye on Russia and its agents. At least once, the Quai d’Orsay contacted the Russian ambassador to remind him of the rules of the game.[1] But Macron wisely avoided making Russian interference a central topic in the campaign. Instead, he focused on France’s problems and how to reinvigorate Europe. This combination – keep an eye on Russia but focus on home – proved an effective way to both win French voters and handle Russian meddling.

To be safe from Russian interference, Europe needs to concentrate on fixing the roof – but, to do so, it will need to keep the roof at least reasonably dry. This Power Audit of EU-Russia relations seeks to describe a path towards finding the appropriate balance between these two goals. It examines how Russia understands its normative struggle with Europe and West, and how Russia’s meddling in European domestic politics fits into that struggle. It then seeks to understand the European side, and how effective Europeans have been at countering Russia’s normative offensive. With the help of ECFR’s network of national researchers in every EU country, we examine how European countries view their – and Europe’s – relations with Russia, and how they perceive Russia’s interference in their domestic affairs. Finally, the paper describes a long-term strategy for both dealing with Russian meddling and winning the broader normative struggle.

A normative war

Russia poses a multifaceted problem to Europe. Its policies clash with Europe’s goals, visions, and values in multiple areas: from Europe’s eastern neighbourhood to the Middle East; from global great-power relationships to domestic arrangements. However, all these clashes share a common thread – they are all rooted in a normative disagreement over the rules and taboos of the international order. Russia’s view of what constitutes appropriate domestic and international conduct for states diverges drastically from that of Europe. “We have completely different visions of what is legitimate, what is desirable, what drives and what should drive policies and politicians,” notes one Russian expert.[2] This is a clash between liberal universalism and authoritarian statism; the liberal international order and realpolitik.

This disagreement has been a long time in the making. In the early 1990s, Moscow briefly tried to join the Western system as a rule-taker. After Western rules collided with domestic political expediency and rulers’ wish to remain in power, Russia became a rule-faker – an imitation democracy – and remained so for a long time. The way Western norms blended with global power in the 1990s left Russia with little choice – if it wanted a share of power, it had to be part of the West. But, underneath, Russia kept moving away from the West.

Russia’s much-ridiculed concepts of “managed democracy” and “sovereign democracy” are important milestones on this journey. Having emerged in the mid-1990s, managed democracy is rooted in the idea that elites need to control the electoral choices of the masses – lest elections have dangerous outcomes. Sovereign democracy is a twenty-first century concept largely authored by Kremlin aide Vladislav Surkov, and it goes a step further by limiting the list of elites who are eligible to steer the masses.[3] If during the 1996 presidential election Western political, economic, and media elites were invited to weigh in and help Boris Yeltsin, then by 2008 only the Kremlin was entitled to decide the future of Russia; all foreign elites and alternative domestic ones had to be kept at bay.

This Russian definition of “sovereignty” – implying top-down government from a single centre, insulated from influence from outside as well as from below – is the root cause of many of the clashes between Russia and the West. Moscow’s desire to be a great power – to shape global norms, exercise veto rights, and dictate terms to others – further aggravates the clash.

Russia aspires to a position in which Moscow could dictate terms domestically, in the neighbourhood, and on a range of global issues, but where no one could dictate terms to Moscow. “There are not so many countries in the world that enjoy the privilege of sovereignty,” noted Putin in 2017. “Russia treasures its sovereignty.” This vision of state sovereignty is bound to clash with Europe’s vision of shared sovereignty, human rights, and the freedom to choose – and it does so in multiple areas.

Russia’s policy in its neighbourhood turns on its desire to have a great-power style “sphere of special interests” in which no outsider can intervene without its consent, implying limited sovereignty for countries in the region. In creating this sphere, Moscow often relies on the elite-centric model it has at home. It props up elites it sees as friendly and assists them in their claim to power. The approach clashes with Europe’s standards of democracy, as well as with its view of the European order, based on the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), as one in which countries can choose their own alliances.

Russia’s intervention in Syria should be viewed in the context of its state-centric worldview: an effort to save a strongman from a popular rebellion. For Moscow, state stability is more important than the Western notion that the murder of civilians must be punished. And Putin entered Syria with a clear intention of creating a normative precedent for similar occasions in future. “I’ll show them [the West] how this is done,” he reportedly said.[4]

Defensive insularism can also be seen behind many of Russia’s economic policies. Western investments are welcome in Russia, but the state is determined to keep control over what it considers to be strategically important industries. At the same time, Russia would not be against establishing monopolistic positions abroad – for example, as a gas supplier to Europe.

Finally, Russia’s meddling in European domestic affairs should be understood as another aspect of its struggle against liberal universalism. Moscow fears Western influence in Russia, so it meddles in the West to send a signal: “stay away from Russia, as we can hurt you too”. Russia clearly views influence as a weapon – as demonstrated by its proposal to the Trump administration to regulate the field in a way reminiscent of, say, arms control. In addition, Moscow lends its support to forces in the West that share its state-centric worldview, or are for other reasons keen to erode the Western liberal order. Russia’s meddling in Europe may occupy the headlines, but it is just one front in the normative war.

Although it has largely waged this war from defensive positions, Russia increasingly views Western rules as not just harmful to its interests but simply unworkable: a dangerous pursuit of utopia. This view was clearly expressed for the first time by Putin in a 2007 speech in Munich: “The unipolar model is not only unacceptable but also impossible in today’s world”. He explained that the model was “pernicious not only for all those within this system, but also for the sovereign itself because it destroys itself from within.”

Major events in the last ten years – the financial crisis, the chaotic aftermath of the Arab uprisings, the refugee crisis, Brexit, and the election of Donald Trump – have only reinforced the Kremlin’s conviction that Western solutions to international crises only foster instability, and that the liberal order is doomed because of the West’s international practices and internal tensions.

Europe, however, is deeply invested in the liberal order – in many ways, even more so than the US. The US may provide the military might to uphold the order, but Europe has made the principles of the liberal order a core part of its identity: the European Union was born out of the idea that cooperation, shared sovereignty, representative democracy, and respect for human rights form the path to peace and prosperity. So, even if the US could agree with Russia – “make a deal”, as Trump has repeatedly suggested – such an option would hardly be available to Europe.

Europe is thus condemned to a normative rivalry with Russia. Both will try to shape the very nature of international relations to reflect their own values. For Europe, the path to winning will not go so much through countering Russia – although this will be necessary, too – as through reinvigorating the Western model by addressing its domestic weaknesses and correcting flawed international practices. If Europe wants to set international norms, it needs to show that these norms are workable – in both its domestic and international practices. Right now, a Russian expert says, “President Putin views Western values and norms as either hypocrisy or utopia.”[5]

Russia’s normative offensive in Europe

The normative struggle between Moscow and Europe is not new. The cold war’s central front might have been the intra-German border, but its outcome was decided in the normative realm, not at the Fulda Gap. The difference today is that Russia’s integration into the Western world, though incomplete, has created more normative fronts. Today, for example, Russia and the West routinely clash over trade rules at the World Trade Organisation – something that would have been impossible during the cold war. Likewise, Russia’s capital has made its way into Western stock exchanges, debt markets, and real estate, often in attempts to stretch established rules.

Russia is now also much more motivated to fight on the normative front than it once was. In this way, it seeks not just to compensate for military weaknesses, but also to respond in the field in which Russia believes it was beaten in the cold war – influence on people’s hearts and minds.

Russia’s interference in Western democracy today is an attempt to erode the Western liberal consensus from within. From the Russian government’s perspective, this meddling is tit for tat. Russia is doing to the West what it thinks the West has been doing to Russia. Many leaders in Moscow believe that the working methods of Western media outlets are no different from those of Russian propaganda channels RT and Sputnik.[6] They see support for Western anti-establishment groups as equivalent to Western support for liberal organisations in Russia and its neighbourhood. “[Americans] are constantly interfering in our political life”, Putin said in a recent interview when asked about Russian meddling in the US. “Would you believe it, they are not even denying it.”

Russia’s interference in Western democracy today is an attempt to erode the Western liberal consensus from within. From the Russian government’s perspective, this meddling is tit for tat. Russia is doing to the West what it thinks the West has been doing to Russia. Many leaders in Moscow believe that the working methods of Western media outlets are no different from those of Russian propaganda channels RT and Sputnik.[6] They see support for Western anti-establishment groups as equivalent to Western support for liberal organisations in Russia and its neighbourhood. “[Americans] are constantly interfering in our political life”, Putin said in a recent interview when asked about Russian meddling in the US. “Would you believe it, they are not even denying it.”

It is hard to know precisely what Russia is doing. Certain things, however, are beyond doubt. Moscow was instrumental in hacking the US Democratic National Committee’s computer system – something that is quietly accepted as fact in policy conversations in Moscow. Yevgeny Prigozhin, a businessman linked with Putin, has – as documented by independent media outlets in Russia –established an industrious “troll factory” on the outskirts of Saint Petersburg. RT is out there for all to see; its editor, Margarita Simonyan, makes no secret of the fact that the channel is an “informational weapon” that plays a role in Russia’s information war with the West.

The history of Russian interference shows how Russia has upgraded its efforts in the West after each major normative clash. The Soviet Union had its own traditions of interference, but for independent Russia everything started after the 2004-2005 Orange Revolution in Ukraine – whose emotional impact on the Kremlin is hard to overestimate. In 2005, the Kremlin launched a major counter-revolutionary offensive at home and, more quietly, also created a new subdivision of the Presidential Administration: the Presidential Directorate for Interregional Relations and Cultural Contacts with Foreign Countries, headed by Modest Kolerov. This was the start of Russian state efforts to influence the discussion outside of its borders – initially in the former Soviet space, including Baltic states.

The effort accelerated after the 2008 war in Georgia. Even though the war achieved its aim – namely, stopping the expansion of NATO – Russia realised that its military was underdeveloped, and that it had lost the information war. That led to an impressive military reform, and equally massive modernisation of propaganda outreach. After the war of 2008, the then three-year-old Russia Today (later RT) found its true calling: questioning Western narratives, as opposed to promoting Russia’s. Russia subsequently created an array of propaganda websites; “public diplomacy” organisations such as Rossotrudnichestvo and the Institute for Democracy and Cooperation; and public relations campaigns that Western companies were hired to run.

After Moscow’s relationship with the West spiralled to new lows following the protests in Russia in the winter of 2011-2012 and the annexation of Crimea in 2014, these activities expanded further. Ironically, it was lack of friends that first inspired Russia to reach out to the part of Europe that shared Moscow’s newly acquired socially conservative rhetoric – such as Le Pen’s National Front and the Freedom Party in Austria. But the refugee crisis that began in 2015 significantly increased the power of these forces and – probably to Moscow’s surprise – turned them into an important tool for eroding the Western liberal consensus from the inside.

Compensating for weakness

Followers of Western media could be excused for thinking that, sometime between 2014 and 2016, Russia invented a completely new destructive weapon – some powerful witchcraft that only Moscow has, and which it is using to subvert the world. Often, this witchcraft is thought to originate in the so-called Gerasimov Doctrine – an article by Russian General Valery Gerasimov that, far from being a Russian doctrine, discusses the perceived features of contemporary Western warfare from a mainly defensive viewpoint.[7] And, indeed, Russian meddling in the West does have some features that are uniquely Russian, but this does not stem from Russia having invented a new, ingenious concept of warfare. Instead, this approach is designed to compensate for Russia’s deficiencies.[8] Russia uses unconventional methods because it is weak, not because it is strong.

For instance, Russia’s use of the hacker community and private companies to carry out its cyber operations often stems from insufficient state capacity. Frequent government use of freelancers – be they criminal networks, activist oligarchs, or shady paramilitary units – also stems from deinstitutionalisation. While decision-making power is increasingly concentrated in the Presidential Administration, policy advice and execution often comes from sources outside established institutions, opening the door to various kinds of people who have unorthodox policy solutions.[9] As Mark Galeotti has documented, law-enforcement agencies frequently mobilise criminals to carry out tasks that are normally in the realm of government. The quintessential example is the case of Viktor Bout, a man whose career spanned the worlds of crime, business, and intelligence work; and whose example illustrates the smooth and often imperceptible transition between official and non-official roles.

At the same time, not all interference operations originate in the Kremlin. Commentators in the West broadly ridiculed Putin’s statement that “patriotic hackers” played an instrumental role in America, but Moscow often acts via proxies to which it has only loose connections. This is ideal for a Kremlin that places such a premium on plausible deniability. And while it is unlikely that something as sensitive as interference in US domestic politics could have happened without some form of approval by Putin, on other occasions he may well have been uninvolved. For example, Moscow insiders suspect that both Prigozhin and Orthodox oligarch Konstantin Malofeev, who has allegedly financed interference in eastern Ukraine and Macedonia, have acted on their own initiative.

This does not make them – or other similar activists – “independent” in the Western sense of the word. In Russia, where most businesses are in some way dependent on the state, hardly anything can be truly independent and everything can be “weaponised”. But these activists most likely acted without receiving specific orders. “They are trying to earn favour”, explained a source in the Kremlin familiar with these matters. “They do something, then turn up at the Kremlin administration, expecting praise and payback. And sometimes they get it. But in their overeagerness, they sometimes also get the Kremlin into trouble, and then they are reprimanded.”[10]

Diplomats working for the Russian Foreign Ministry are ambivalent about the value of subversive measures. Some gain emotional satisfaction from them (“we did not do it, but more should have been done,” was one diplomat’s comment on US election hacking),[11] but others know that meddling has already drastically limited Russia’s ability to carry out normal, legitimate diplomatic work such as promoting the country’s business or even cultural ties. Meanwhile, its policy benefits remain dubious, at best. As one affiliate of the foreign ministry interlocutor described it: “I ask these people [who plot subversion]: do you think that way you will change Germany’s attitude towards sanctions? No, of course not, they say. Do you then think you can change government there? Nooo! So what is the aim of it? At which they look at me with wide eyes, without having an answer.”[12]

The business community – badly hit by a new set of US sanctions – is also displeased. This frustration is unlikely to cause them to lash out at the Kremlin, but they have been trying to send it a message: “If you need to do such things [hacking], please at least do them professionally and do not get caught.”[13]

Most of the time, Russian analysts agree, Russia’s meddling in European domestic politics is neither well-coordinated nor specifically designed to bring down the EU or change its governments.[14] Rather, it is an improvised collection of activities engaged in by various actors who are linked together by an ideology that labels the West as an adversary. In Moscow, experts often characterise meddling in European elections as just trying one’s luck: “You walk into a casino, play at one table, lose, walk to the next one and try again.” Or: “It is like a hunter entering a forest – he does not know what exactly he catches, or if he catches anything at all.”[15]

The impact of Russian meddling in Europe

Regardless of the method used, the most important questions about meddling are: “Does it work?”; and “what are its effects?”. Russian historian Yuri Slezkine has described how, during a recent book tour, he encountered two radically different images of Russia in almost every European country: “There is the daytime Europe: people at university auditoriums, media and governments, who all think that Russia poses a threat. But when evening comes, I call Uber and go out to a pub – and in this world, in the night-time Europe, most people think that Putin is great.”[16]

ECFR’s surveys in the 28 EU member states, however, imply that the impression that Russia has somehow out of the blue managed to charm Europe’s pub-keepers and taxi drivers is misleading. Russian efforts to influence Europe capitalise on what already exists. Russia might resort to media manipulation, or even outright illegal activity such as hacking or bribery. But to convert this into real influence on European domestic politics, it needs to make use of pre-existing cleavages and shortcomings – be they neglected minorities, threatened majorities, biased media outlets, home-grown corruption, insufficient law enforcement, or disillusionment with politics.

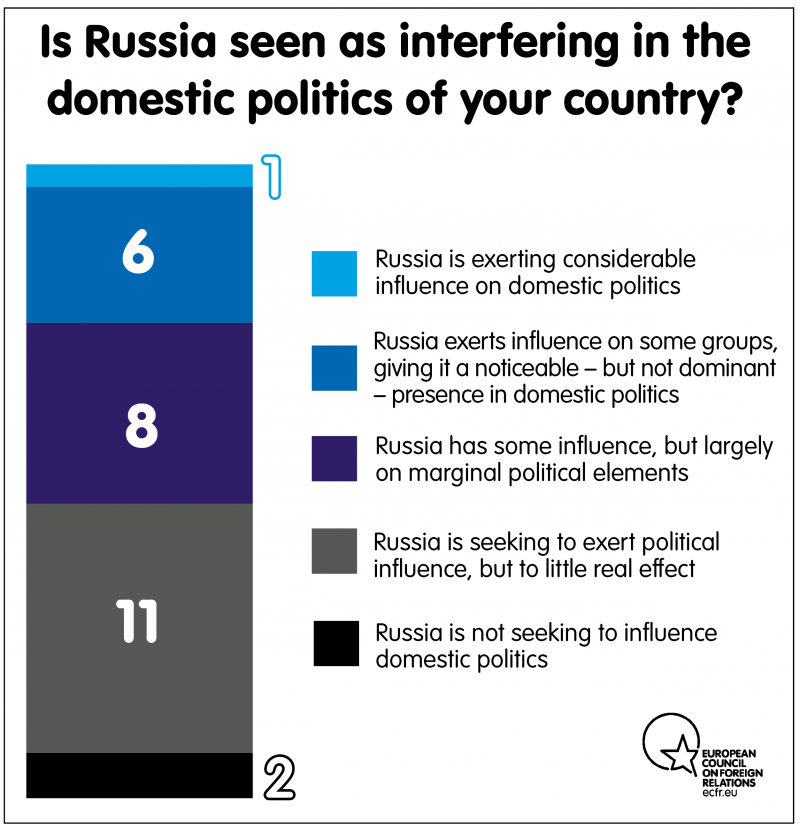

According to ECFR’s surveys, most EU countries see some evidence of Russia’s attempts to influence their domestic debate but view its effects as limited. They regard Russia as having charmed some marginal groups, but not as having established considerable influence over the country as a whole.[17]

However, even the countries that have not experienced much Russian meddling take it seriously as a policy issue. Events in 2016 – including the Lisa case, involving the spread of a fake anti-immigrant story in Germany, and Russian interference in the US election – served as a wake-up call. These high-profile incidents have raised the issue on the EU agenda, inspiring European governments to look at Russian influence in their countries and start – though unevenly and often clumsily – to work on countermeasures.

However, even the countries that have not experienced much Russian meddling take it seriously as a policy issue. Events in 2016 – including the Lisa case, involving the spread of a fake anti-immigrant story in Germany, and Russian interference in the US election – served as a wake-up call. These high-profile incidents have raised the issue on the EU agenda, inspiring European governments to look at Russian influence in their countries and start – though unevenly and often clumsily – to work on countermeasures.

The surveys indicate that even groups that display sympathetic attitudes towards Russia are not usually Moscow’s puppets or unconditional supporters. There is some home-grown logic behind their stance and activities; Russia generally plays the role of an ally of convenience. The Freedom Party, Alternative für Deutschland, and Hungary’s governing Fidesz party are all in this category. While Europe worries about the effects of pro-Russian populism, to observers in Russia it is evident that European fringe parties have only limited pro-Russian influence. As a recent report from two prominent Russian analysts notes, “Eurosceptic and traditionalist movements have an influence on the overall atmosphere in Europe, but they lack the potential, primarily the intellectual one, needed for devising a strategy that would engage not only protest voters but also those who are looking for an alternative political and economic model.”

Still, some narratives promoted by Russia gain significant traction in Europe. The view that Russia is an important global actor with which Europeans need to find agreement is shared by mainstream political forces in several European countries (Austria and Italy, to name just two). But this view stems more from these countries’ indigenous foreign policy thinking than from Russian propaganda. In some states – including Slovenia, and parts of Bulgaria and France – Russia is seen as a counterweight to other powers, usually the US. But this more likely stems from condemnation of the US than praise of Russia.

RT and Sputnik have only a minor impact. They enjoy some niche appeal among people who, for one reason or another, feel neglected by the mainstream media – such as Latin American audiences in Spain and some Scottish audiences in the lead-up to the Scottish referendum on independence, during which parts of the British mainstream media ridiculed and neglected the independence cause.[18] Russian-speakers in Baltic states tend to watch domestic Russian TV channels, which also follow the Kremlin’s propaganda lines.

Moreover, the surveys show that Russia’s influence, where it exists, does not spill over from one issue to another. Countries that have deep cultural and historical links to Russia, such as Italy and Bulgaria, are far from seeing contemporary Russia as a model for state governance. The prolific business links with Russia enjoyed by Austria, Italy, and Germany may have led to dissatisfaction with EU policies, but all these countries have refrained from serious efforts to break ranks on sanctions – so far, at least.

Sympathy with Russia’s geopolitical worldview – in, for example, Hungary or Italy – does not translate into formal acceptance of Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Socially conservative sentiment in Poland hardly extends to approval of Russia’s socially conservative rhetoric; and very few Europeans view Putin as the ideal of a strong leader (the only European political parties to lean towards this view appeared to be Italy’s Northern League and Greece’s Golden Dawn; some sympathy for Putin can also be detected among Russian-speakers in Baltic states).

Fearing fear itself

Given its rather limited effects, Russia’s meddling in Europe seems to pose a fairly minor threat – but it has indirect side-effects. Some European experts now believe that the necessary awareness has crossed over into unhelpful paranoia. “Currently, our panic is more dangerous than Russia’s actions,” argues Stefan Meister, from Germany’s DGAP think-tank; a good number of policymakers and intelligence insiders seem to agree.[19]

Indeed, the most pernicious effect of Russian meddling may be the way it has distorted Europe’s debate both about itself and about Russia. In much of the media discussion, Russia plays a prominent role in almost every bit of ill-fortune that has befallen the West – from the refugee crisis to the rise of populism to the independence referendum in Catalonia. Accusations reached the grotesque when the British Daily Mail – a major and influential source of skewed, pro-Brexit articles about the EU – started publishing stories with headlines such as “Exposed: How Vladimir Putin’s troll factory DID twist the Brexit vote.”

Western media outlets now often interpret Europe’s elections as more a struggle with Russia than a fight between domestic political parties. In December 2016, for instance, elections in Bulgaria and Moldova coincided with a change in government in Estonia – prompting the media to briefly interpret all three as victories for Russia. In fact, Russia was not a defining factor – or even a factor at all – in any of these events.[20] And this is not just the case with small countries whose politics are obscure: foreign media outlets often characterised the 2017 French election as a struggle between three pro-Russian candidates and one pro-Western one.

This tendency of interpreting every election or event through the Russian lens is counterproductive. Russian efforts can only play on pre-existing social cleavages. Arguably, their efforts can amplify existing tensions, but most European societies are proving quite adept at polarising themselves. Reducing everything to Russian meddling leads to dangerous neglect of the real issues behind home-grown polarisation and encourages demagogic politicians to use the threat from Russia opportunistically. Indeed, the highly politicised use of the Russian bogeyman may reduce the establishment’s credibility, and even its ability to discuss the Russian threat seriously. At the same time, genuine domestic grievances can, if overlooked, reduce a society’s resilience and make it more susceptible to outside interference.

If one views Russian meddling as normative shotgun blast aimed not at some specific outcome but rather at undermining the West’s faith in itself, then one can see it has had some impact. For decades, European elites have felt basically safe on the home front, but they can no longer take such domestic immunity for granted. Russia has induced fear and occasionally derailed the European agenda, by making Europeans fear the Russian hand when they should focus on their own shortcomings.

However, in the context of the normative contest, there is also some good news for the West: Russia may have intensified its attempts to erode the EU countries’ internal consensus exactly because it has become much harder to erode the consensus among EU member states.

Europe’s normative unity

The internal cohesion of European countries is important, but in Europe’s normative struggle with Russia, it is just one front line. To be politically effective vis-à-vis Russia, the EU also needs unity among its member states. European Commission Vice-President Frans Timmermans famously said that the EU has two kinds of member state: small member states and member states that have yet to understand they are small. No European country alone can compete effectively in the normative struggle with Russia. But, collectively, European countries can both set international norms and – if they unify behind a common vision and strategy – help shape Russia’s policy choices and behaviour.

A decade ago, a lack of unity was the chief reason that Europe had no effective policy on Russia. ECFR’s previous Russia Power Audit, published in 2007, noted that the EU had failed to translate its strengths into policy due to disunity among its member states, thereby allowing Moscow to divide and rule despite having a much weaker hand. Today, the EU may face various crises and lack self-confidence, but it has overcome many of the issues that once paralysed its Russia policy.

Europe still seems to think of itself as deeply split on Russia. “Very little can be done by the EU, because the member states lack a common vision about Russia”, said one of the EU’s top diplomats when describing his work.[21] But, in the last three years, the EU has actually been remarkably united and firm in following its official policies on Russia.

And Moscow has noticed. Ironically, Europe’s position on Russia is sometimes more quickly and clearly summed up in Moscow than in Brussels. Moscow spotted Europe’s change of heart early on, at the beginning of 2012, when Putin reportedly noted that “they have all ganged up against me”.[22]

And Moscow has noticed. Ironically, Europe’s position on Russia is sometimes more quickly and clearly summed up in Moscow than in Brussels. Moscow spotted Europe’s change of heart early on, at the beginning of 2012, when Putin reportedly noted that “they have all ganged up against me”.[22]

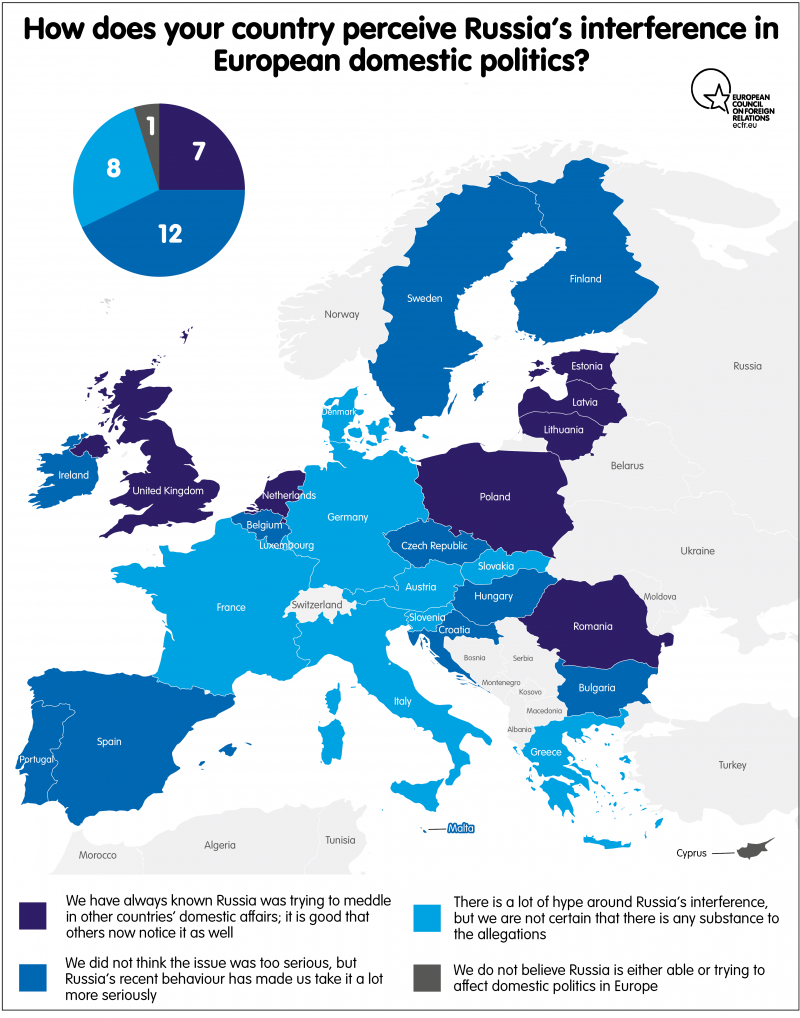

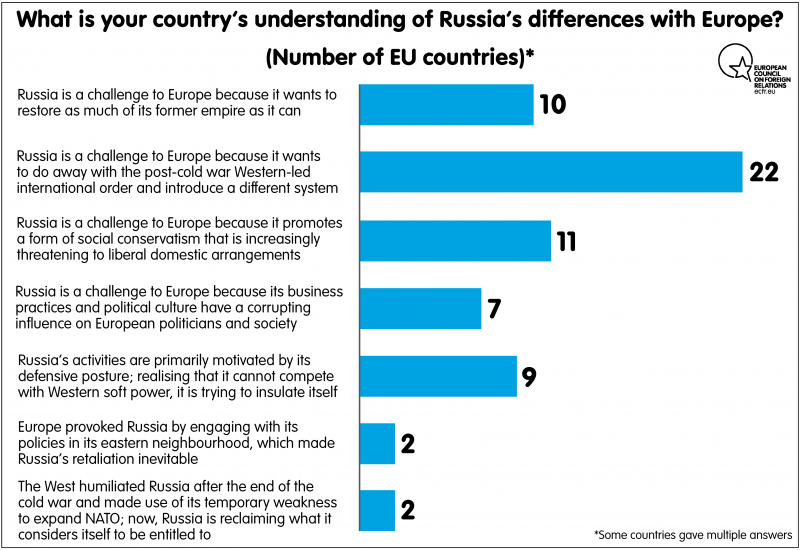

ECFR’s surveys of EU policymakers show that Putin was right. Europe is now united in its assessment of Russia. This sharply contrasts with the situation ten years ago, when Baltic states and Poland viewed Russia as a consolidating authoritarian state with dangerous ambitions abroad, while Germany still saw it as a country that was democratising – even if slowly, with multiple detours and setbacks. Now, European policymakers overwhelmingly perceive Russia as posing a normative challenge. They view Moscow as seeking to dismantle the post-cold war European order. At the same time, the narratives Moscow promotes – which paint Russia as the victim of Western policies and its actions as forced responses to Western assertiveness – have only very limited traction in a few EU member states (such as Austria, Cyprus, and Greece).

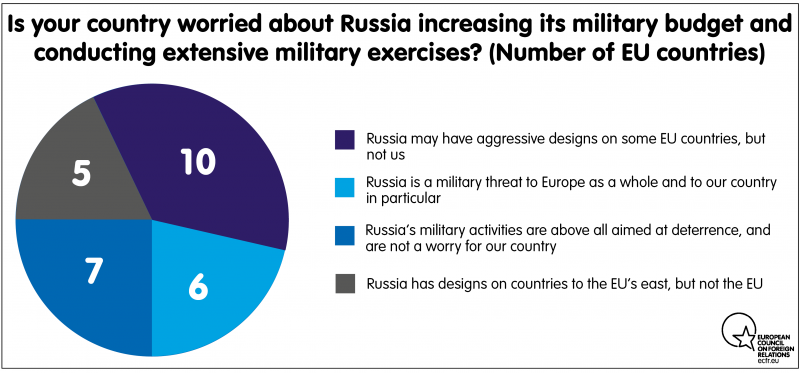

European views are also significantly aligned in assessments of the military threat from Russia. Six EU countries think that Russia poses a direct military threat to them, and to Europe as a whole; ten believe that Russia might threaten the fringe states of the EU; and five others see Russia as a military threat not to the EU, but to non-member states in eastern Europe. Only seven countries believe that Russia’s military activities are primarily aimed at deterrence and therefore not a cause for concern.

European views are also significantly aligned in assessments of the military threat from Russia. Six EU countries think that Russia poses a direct military threat to them, and to Europe as a whole; ten believe that Russia might threaten the fringe states of the EU; and five others see Russia as a military threat not to the EU, but to non-member states in eastern Europe. Only seven countries believe that Russia’s military activities are primarily aimed at deterrence and therefore not a cause for concern.

EU countries now view Russia’s actions as actually or potentially destabilising in almost all regions: from Europe’s eastern neighbourhood and the Baltic Sea to the Western Balkans, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean (including on the question of Cyprus). These negative expectations even affect the Arctic, where the relationship between Russia and EU countries has in fact been mostly constructive.

EU countries now view Russia’s actions as actually or potentially destabilising in almost all regions: from Europe’s eastern neighbourhood and the Baltic Sea to the Western Balkans, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean (including on the question of Cyprus). These negative expectations even affect the Arctic, where the relationship between Russia and EU countries has in fact been mostly constructive.

Moscow’s ambition to have a sphere of influence no longer disturbs only – or even primarily – eastern EU member states. Croatia and Slovenia, for example, are both concerned about Moscow’s attempts to create obstacles to the Euro-Atlantic integration of the Western Balkans. Overall, a diverse array of countries including Ireland, Portugal, Finland, and the United Kingdom finds Russia’s activities in Europe’s neighbourhood deeply disturbing. Also, European countries are almost unanimous in their view of Russia’s relationship with the US as dangerous and destabilising because of the potential for Washington and Moscow to collude – or, alternately, collide – with each other.

Overall, bad experiences with Russia on issues such as Ukraine, Syria, and interference in European domestic politics have now spilled over into low expectations from nearly everyone in nearly all areas.

Overall, bad experiences with Russia on issues such as Ukraine, Syria, and interference in European domestic politics have now spilled over into low expectations from nearly everyone in nearly all areas.

A united policy

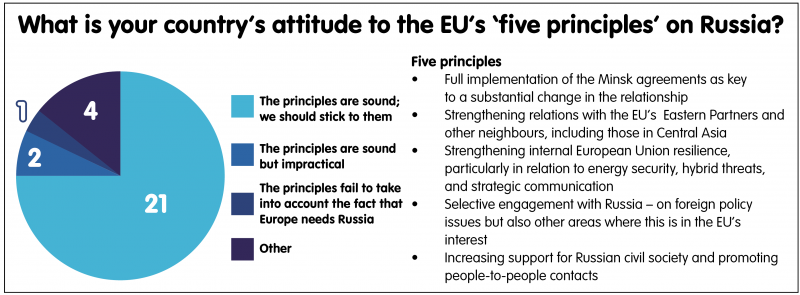

Europe’s unity of assessment on Russia has already translated into a fair amount of unity on policy. The EU’s five principles on future relations with Russia are very popular, receiving the full support of 21 countries.

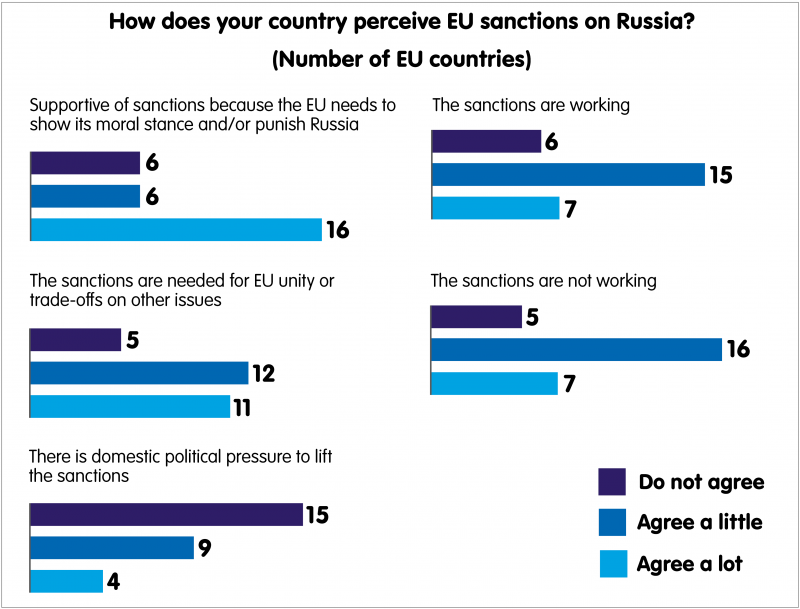

This solidarity translates into strong support for sanctions, even though member states are broadly ambivalent about how well the measures work. Most countries think that sanctions against Russia are necessary. For many, they are needed to signal the EU’s moral position – but some admit that they accept sanctions as the price of solidarity. Southern Europeans lend their support to the EU on Russia as a down payment on support for other, priority issues from states in the east and the north that view the country as an existential threat. Most governments are under some domestic pressure to lift sanctions – stemming from political parties or business lobbies – but this pressure is strong and meaningful only in Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, and likely also – after its latest elections – Italy.

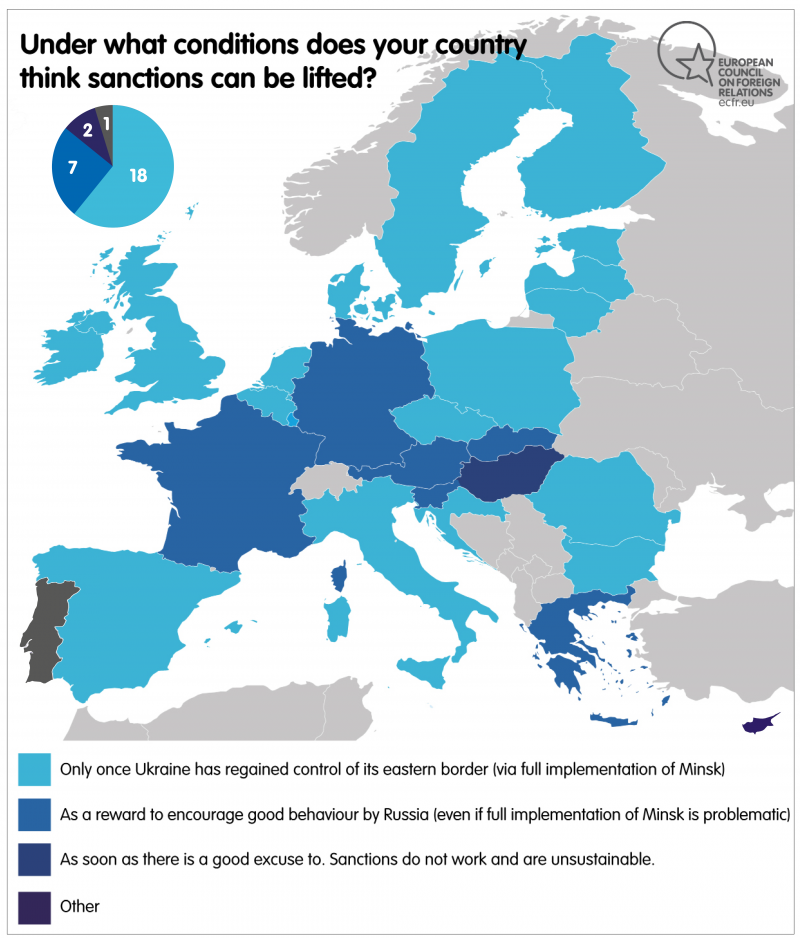

There is also considerable unanimity on when to end sanctions on Russia. The overwhelming majority of member states believe that the EU can only lift sanctions once Ukraine has regained control of its eastern border, while seven countries are ready to consider gradually easing sanctions if Russia starts making steps towards withdrawing from eastern Ukraine. There is some disagreement about whether the sanctions influence Russia’s behaviour – the consensus seems to be that, in limited ways, they may do. Only Hungary says that sanctions definitely do not work and should be dropped as soon as possible – but even Budapest has not come close to breaking ranks on their renewal.

There is also considerable unanimity on when to end sanctions on Russia. The overwhelming majority of member states believe that the EU can only lift sanctions once Ukraine has regained control of its eastern border, while seven countries are ready to consider gradually easing sanctions if Russia starts making steps towards withdrawing from eastern Ukraine. There is some disagreement about whether the sanctions influence Russia’s behaviour – the consensus seems to be that, in limited ways, they may do. Only Hungary says that sanctions definitely do not work and should be dropped as soon as possible – but even Budapest has not come close to breaking ranks on their renewal.

Indeed, ECFR’s surveys also show that the EU has come to view unity in its Russia policy as a value in and of itself. Member states want normative questions to be handled by the EU as a whole; only Hungary, Greece, Austria, and Bulgaria have any faith in the bilateral track.[23] Many member states that are keen to maintain bilateral contact with Moscow – from Italy and Austria to Germany and Finland – all emphasise the fact that they view such contact as consistent with, and complementary to, EU policy (even if, as in the case of Austria, they disagree with the policy). More importantly, there has been no serious effort to challenge consensus European policies. Brussels insiders say that the rollover of sanctions twice per year has, if anything, become easier – despite some sotto voce grumbling.

Countries that do not like sanctions, however, tend to emphasise the need for universal compliance – and rightly so. Italy has demonstrated particular vigilance, by criticising Germany’s wish to support the construction of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline (after Italy lost South Stream) and by pointing out that “some countries that pose as principled Russia critics” are in fact the greatest enablers of Russian money-laundering – a transparent allusion to the UK, which only began to make a serious attempt to tackle the issue of dirty Russian money after the attempted assassination of double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter, Yulia, in spring 2018.[24]

Paradoxically, the recent pile-up of economic and security crises seems to have helped Europeans become more united. Member states need to pick their fights with Brussels. Russia is a priority for those who feel threatened by it, but it is less important to those who do not.[25] Member states with varying priorities understand that to benefit from solidarity, one must contribute to solidarity.

It is not all togetherness. Hungary and perhaps Greece are examples of countries in which disagreements with the EU mainstream (on asylum policy and the protection of civil society, and the euro respectively) correlate with a divergent stance on Russia. Indeed, Hungary stands out as the one EU country that, in the context of normative war, often takes a stance closer to the Russian side of the argument. Hungary’s pro-Russian sentiment stems from the elite and encompasses a wide range of policy issues – from acceptance of Russia’s great-power ambitions (a view also found elsewhere in the EU) to criticism of liberal values and the liberal international order (a view not found in other EU capitals). But even Hungary avoids challenging the EU’s common position on its own, while Greece’s ardour for Russia cooled after Moscow failed to offer it meaningful economic aid during the peak of its economic crisis.

Overall, Russia may still try to sow discord within the EU, but it is far less able to play member states off against each other than it was ten years ago.

Beyond unity: Translating values into policy

This new-found unity is a critical asset in the EU’s struggle with Russia. But it is clearly not enough to manage the normative challenge that Russia poses. For that, one also needs policy.

Every Russia watcher is aware of the famous “cursed questions”: “Who is to blame?”; and “what is to be done?”. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov once jokingly added a third: “What is to be done with the one who is to blame?”.[26] This is the question that Europe lacks a good answer to.

EU member states generally agree that Russia is to blame. Sanctions on Russia and troop reinforcements in eastern EU states have provided some answers to the question of what is to be done. But, when asked “what is to be done with the one who is to blame?” – in other words, “what should Europe’s long-term Russia strategy be?” – Europe is lost. Nonetheless, the EU cannot prevail in a normative war if it does not know how to tackle the challenger.

The closest thing that the EU has to a Russia strategy – the five principles – say a lot about Europe’s declared values but little about Russia. To be effective, the EU also needs a common Russia strategy that reflects not just Europe, but also Russia. The current approach is laudably true to Europe’s principles, but it fails to address the more complicated questions at the core of a true Russia strategy: what does the EU want to achieve with Russia? What can it achieve? How can Russia fit into the liberal world order that the EU seeks to promote? How can the EU influence Moscow?

Answering these questions is difficult and risks dividing Europe on Russia once again. But an effective Russia strategy for a normative war needs to accommodate an agreement on concrete policies. The EU will need to strategise, not just sermonise.

The – clearly non-exhaustive – list of issues below highlights some areas in which a lack of both clarity and a joint approach hampers EU policymaking. For instance, the EU does not have a common strategy on sanctions, its eastern neighbourhood, or energy security. In addition, there is also confusion about methods – such as dialogue with Russia – and the division of work between member states and EU institutions.

Eastern neighbourhood

Europe’s normative war with Russia manifests most fiercely and dangerously in the joint neighbourhood. Russia wants to keep the neighbourhood as its “sphere of privileged interest” and deny countries there the opportunity to join Western institutions without Russia’s permission. For EU countries, such an approach is simply unacceptable – made taboo by their twentieth-century experiences with spheres of influence. As German Chancellor Angela Merkel put it, “old thinking about spheres of influence, trampling international law, must not succeed.”

Russia’s thinking is also unrealistic. Moscow’s aim of holding on to a sphere of influence without the consent of the countries involved – but also without outright (military) control over them – is bound to lead to tension and instability. Ukraine is a prime example here: Russia had extensive leverage over its economy and leadership, only to see it swept away in a popular revolution. Or one could look at Belarus and Armenia: on paper, both are dedicated members of the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union but, in practice, both are working to limit Russian influence, as elites in the countries see Russia as a threat.

Europe cannot possibly endow Moscow with the sphere of influence it craves: this would go against all its normative principles and lessons learned from history. But, similarly, the EU lacks a viable policy for addressing this conceptual clash. The EU’s most successful neighbourhood policy has long been institutional enlargement, but it is split on whether to offer countries to its east a membership perspective. Russia is determined to resist any such development, while the countries themselves are going through a long and bumpy political transformation, characterised by ongoing tension between corrupt elites and maturing societies that demand a greater say. There is not a desire for EU membership everywhere and, even where there is, the reforms required by the accession process would infringe on the vested interests of powerful domestic constituencies.

Furthermore, even if Europe’s whole eastern neighbourhood managed to reform and to join Western institutions, this would amount to Europe beating Russia at Russia’s own game – that of spheres of influence. It would not mean that West had brought Russia around to the ideas of cooperative, mutually beneficial arrangements that Europe sees as the goal for the continent. And, conversely, if these countries fail to reform, they still retain their rights to sovereignty and territorial integrity. Europe cannot make the whole continent’s normative geopolitical order dependent on certain countries’ ability to reform (or lack thereof).[27]

For the time being, the EU and Russia are stuck in a normative struggle in the eastern neighbourhood that neither has the capacity to win any time soon. To prevail, the EU needs to focus not just on promoting democracy, but also on upholding the principles of the OSCE-based post-cold war European order. It needs to find ways to boost the sovereignty of these countries without an immediate membership perspective. The demand is there; Belarus, for example, has clearly asked: “please help us protect our sovereignty, even though we will not become a democracy any time soon.”[28] The EU not only lacks a comprehensive and thought-through set of measures for fulfilling this request, but even finds it hard to talk about sovereignty and democracy without conflating the two concepts.

The goal and future of sanctions

The EU has maintained unity on sanctions for four years. In that time, the measures have become both the essential test of EU unity and an irreplaceable tool for signalling the seriousness of its normative condemnation of Russia’s actions. But, as ECFR’s surveys show, there is still no joint vision of how the sanctions will accomplish their goals and how much time they should take to do so. The absence of immediate results has led some policymakers – most notably in Italy, but also in Austria and Hungary – to declare that sanctions do not work. “You see that neither the political nor the economy goals that have been attached to the sanctions by the European Union have been successful,” lamented Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijarto during his visit to Moscow in autumn 2017.

There is no doubt, though, that sanctions have had economic effects. A 2015 IMF report on the Russian economy indicates that Western sanctions and Moscow’s retaliatory sanctions would cause accumulated losses of up to 9 percent of GDP over the following 10-15 years. The political effects are less clear, but still detectable. In 2014, the sanctions did not succeed at convincing political and business elites to put pressure on the Kremlin. By 2017, however, a prominent group of technocrats started speaking up in favour of improving relations with the West. “If we want our economy to grow, and grow smartly, then we need to improve relations with the West, and for that, also Russia has to take steps,” proclaimed former finance minister Alexei Kudrin.[29]

The evidence on the ground in Donbas is similarly mixed. Some studies suggest that specific sanctions have constrained Russian political and military actions in Ukraine, but it is at least as likely that Russia’s invasion of eastern Ukraine in 2014 slowed due to a change of strategy and a revision of war aims. Yet Putin’s September 2017 proposal to send UN peacekeepers to Donbas is viewed in Moscow as the first probing step towards an exit strategy – albeit a hesitant one.

The lesson here is that sanctions are inherently a long-term instrument. They do not work in isolation, but in combination with other policies and developments. Therefore, achieving their stated aims – the fulfilment of the Minsk II agreement and Russia’s exit from Donbas – will take time.

Furthermore, in a normative war, the stated aim may not even be the most important one. These immediate goals hide a broader effort to demonstrate that Europe has the capacity and unity to hold Russia to the most fundamental tenets of the liberal order, and to influence Russia’s thinking. If the West’s lukewarm reaction to Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 made the Ukraine invasion possible, then the experience of life under sanctions will affect Russia’s calculations at similar junctures in the future. “Russia will start taking Europe seriously when it sees that Europe is ready to suffer some hardship to defend its principles,” said Sergei Guriev, an exiled Russian economist currently working for the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.[30] Europe has now demonstrated such readiness: it has shown that it has a powerful normative weapon that it is ready to use.

Energy security

The Russians have often tried to use their energy relationship with various European states to corrupt and divide the EU. In the process, they seek not only influence but also, implicitly, to demonstrate that the EU’s normative commitment to the rule of law cannot defeat the profit motive. The message is that European society is, in essence, no different from Russia’s when money is on the line.

In the last ten years or so, however, Moscow has had little success in this effort. The EU’s energy relationship with Russia is no longer a very effective tool in Moscow’s divide-and-conquer approach. The EU’s third energy package – which entered into force in autumn 2009 and aimed to open European energy markets – has made the internal energy market a lot more transparent, flexible, and therefore less susceptible to sweetheart deals from Russia. Ownership unbundling – designed to break down gas-export monopolies – separated gas production from transportation and thereby increased competition, making Gazprom’s attempts to monopolise the European market untenable.

The EU has done many other things to diversify its energy supply away from Russia: new interconnectors and reverse flows within the EU now provide the necessary security for the member states that are most vulnerable to Russia cutting off their gas supply; intergovernmental agreements provide greater price transparency and equality; and improved energy efficiency and alternative fuels have reduced the overall share of gas in Europe’s energy balance. Today, Russia remains the largest supplier of gas to the EU, but it cannot use gas as a weapon in the normative struggle in the way that it did ten years ago.

However, disputes around the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline – which would run from Russia to Germany via the Baltic Sea – show that there continue to be important disagreements. Unlike the debate over Nord Stream 1, that over Nord Stream 2 is not about how to deal with Russia but rather about competing business interests and differing views of energy security and diversification. Nor does Nord Stream 2 divide member states the way Nord Stream 1 did: it is easy to find people in northern or eastern Europe who are unconcerned about the potential impact of Nord Stream 2, as well as Germans who oppose the pipeline.

Even so, the views of EU states do not provide a basis for sound policy. Some countries in northern Europe – such as Denmark and, to a lesser extent, Sweden – consider the pipeline to be a security concern, fearing that Russia will use maintenance as a cover for covert operations. Others, such as Finland, see it as a purely commercial endeavour. Some countries view Nord Stream 2 as contrary to the letter or the spirit of the Energy Union, while others believe that the pipeline should be allowed because it predates the concept of the Energy Union. Finally, Germany considers the supply of Russian gas via multiple pipelines to be sufficient energy diversification if the product can later be freely sold in an interconnected European market, while Poland believes that true diversification and energy security are unachievable without greater involvement of suppliers other than Russia.

Ultimately, who is right matters less than resolving the disagreement. European unity on Russia is far more important than the energy market effects of Nord Stream 2. The latter can always be mitigated, but the Russians are already seeking to use disagreements over Nord Stream 2 to undermine broader European unity on Russia policy. To avoid this outcome, all sides need to seek a compromise on the approach, agree on a European-level process, and commit to accepting the result. Meanwhile, Merkel’s recent statement that Nord Stream 2 should be viewed as related to the future of gas transit through Ukraine is a welcome step – a sign that the EU realises the complexity of the normative challenge.

The role of the EU

To prevail in the normative struggle, member states also need to think harder about how to integrate the EU – its member states and EU institutions – into diplomacy with Russia.

For the last four years, for example, the EU’s policy on Russia has taken its lead from France and Germany – the European powers represented in the Normandy format – with EU institutions and other European countries having little or no role. This non-EU arrangement has worked relatively well until now but, even so, it is probably unsustainable. France and Germany have done a good job of building support for their efforts; Germany has taken particular care of the concerns of the countries that are most vulnerable and sensitive to all things related to Russia – such as Baltic states – by keeping them informed. But some dissatisfaction is building up among medium-sized EU countries such as Sweden and Holland, which – while they do not dispute the essence of the policy – would like to play a larger role. “Germany and France have done the right thing – and deserve all credit”, says a Swedish diplomat. “But this format cannot become the model for the future. We created European institutions to represent us all.”[31]

An increasing number of European leaders are making bilateral visits to Moscow – both Swedish and Austrian representatives have shown up there, while Finland regularly stays in touch. They go for various reasons. Finland wants to maintain contact with a complicated neighbour, while Austria wants to enhance its business contacts with Russia. But many ministers, such as the Swedes or the British, just want to be part of the game, to feel relevant. These visits are not bad in and of themselves. For now, they are mostly harmless, if largely useless. Yet, in theory, Moscow might seek to make use of such contact to split Europe and erode the consensus behind sanctions or other policies. This is not to imply that European leaders should avoid visiting Moscow but to suggest that, when they do visit, they should take with them a strong conception of Europe’s Russia policy.

This conception should also guide and empower EU institutions. These institutions are supposed to be the place where member states’ positions are reconciled and synthesised – with everyone having the ability to feed in. For Moscow, it is exactly these institutions that embody the strict normative face of the EU. “We do not need a policy towards the EU; we are going to talk with the member states,” snapped one highly placed Russian when asked about changes in Russia’s policy towards the EU.[32]

And indeed, for now, Moscow has decided that the institutional EU hardly matters. According to Moscow insiders, the EU was written off as a policymaker after Jean-Claude Juncker’s visit to St Petersburg in summer 2016. Around that time, Russia contacted Juncker with some policy proposals, but it never heard back from him – while bilateral tracks hummed along as before.[33]

For all these reasons, member states should try to bring more of the concerted power of EU institutions to bear in the EU’s Russia policy; they should aim to coordinate among themselves in ways that give smaller countries a role in policy and empower EU institutions to be meaningful interlocutors with Moscow.

Dialogue with Russia

Finally, the EU needs to devise a new model for dialogue with Moscow – one that can support the policy that needs to emerge from member states’ now-united assessment of Russia.

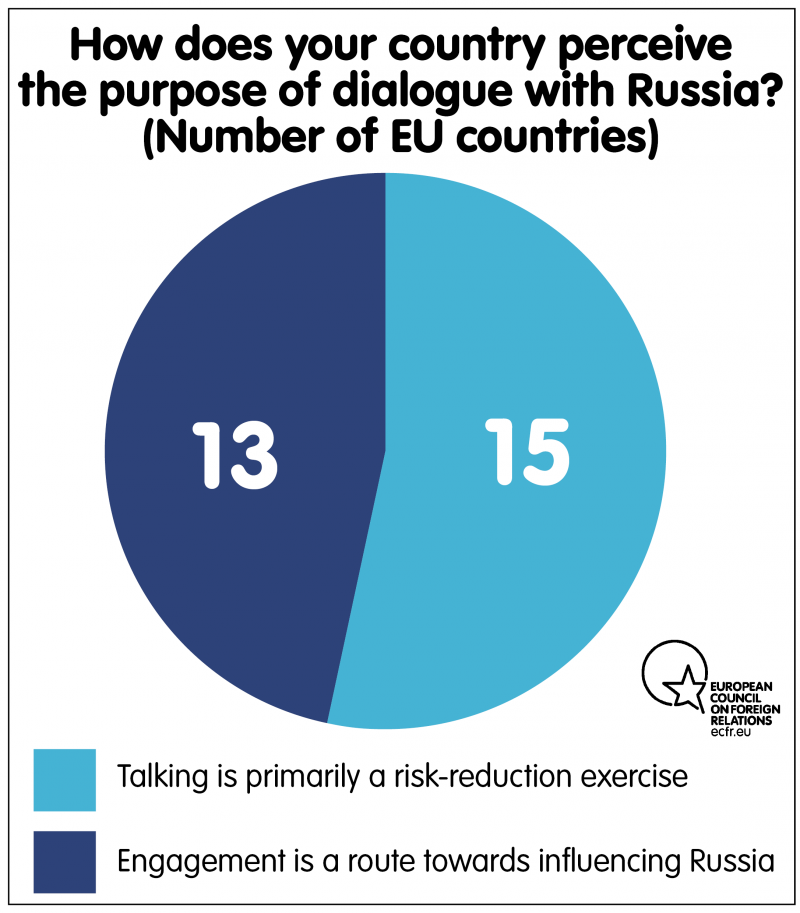

The divisions of the past – when countries such as Germany hoped to socialise Russia in the Western model by engaging with it, but eastern Europeans saw engagement as legitimising Russia’s predatory behaviour – still influence the whole concept of dialogue with Russia. This legacy makes the idea of dialogue contentious and gives birth to fruitless arguments that treat it as an end in itself. “We had a long debate at NATO on whether to talk with Russia or not, without having the slightest idea of what we want to be talking about,” confessed one former NATO ambassador.[34]

The divisions of the past – when countries such as Germany hoped to socialise Russia in the Western model by engaging with it, but eastern Europeans saw engagement as legitimising Russia’s predatory behaviour – still influence the whole concept of dialogue with Russia. This legacy makes the idea of dialogue contentious and gives birth to fruitless arguments that treat it as an end in itself. “We had a long debate at NATO on whether to talk with Russia or not, without having the slightest idea of what we want to be talking about,” confessed one former NATO ambassador.[34]

The situation in the EU is not much better. Member states are unsure what they want to talk to Russia about, or what talking can achieve in principle. ECFR’s surveys show that around half of EU members still hope that engagement can influence Russia’s political trajectory, while the rest view it as a risk-reduction measure.

With such divisions, the EU cannot meaningfully defend its interests vis-à-vis Russia. It needs to do better; and the way is obvious: when the EU devises a joint policy on Russia that goes beyond declarations of values, dialogue will stop being a surrogate for policy and find its natural place as a tool of policy.

Beyond Russia: How Europe can invest in resilience

The measures above would help make Europe more effective vis-à-vis Russia. However, they are not enough to counter the Russian normative challenge. European governments need to complement policy on Russia with investment in Europe’s resilience.

Resilience is important for practical as well as normative reasons. Europe needs to show Moscow that its norms are viable and shared by its societies, and that the collapse of the European order is not on the cards. Similarly, European policies can only work if they have reasonable support at home.

It is clear that Russia’s interference activities in Europe that are outright illegal and aggressive – such as cyber attacks or intrusive intelligence activities – need to be met with appropriate and direct countermeasures. But things are more complicated in the areas where Russia’s activity is hostile but legal.

Today, there are widespread calls to start countering Russian influence in Europe by exposing its trolls, fake news outlets, paid agents, and “useful idiots”, and by banning its TV channels and confiscating its money. While many of these measures make sense, it is counterproductive to view them primarily as efforts to fight Russia. Firstly, this is because Europeans cannot effectively counter this part of the Russian normative offensive head on. It is simply too diffuse. As Galeotti notes, “this is not a great white shark of the infosphere, directed by Moscow Centre, but a shoal of piranhas; while you fight one off, the rest are rending the flesh off your bones.” Here, the uncoordinated and improvisational nature of Russia’s activities is a strength. When Europeans mobilise against them with the resources of the state, it can often seem like an overreaction: shooting a cannon at a sparrow.

Secondly, and more importantly, the best advice focuses not on stopping Russia but on improving Europe’s resilience. Instead of fighting raindrops, one should fix the roof. Some Europeans have already learned this lesson: “When we started complaining about Russian interference ten years ago, the West told us to calm down and put our own house in order,” said a Baltic ambassador at a recent discussion about Russian interference in the West. “That was good advice. We would now like to give it back to you!”[35]

There are many concrete things that EU governments can do to improve their countries’ resilience:

- Invest in horizontal links between state agencies: By definition, hybrid threats emerge in multiple fields. A military threat or an attempt at political destabilisation is likely to coincide with information warfare, efforts to inflame social tensions, and/or threats to infrastructure. This often complicates early warning processes, as information on what is happening remains scattered across different agencies. Governments should therefore ensure that state agencies talk to one another. The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats – a voluntary multilateral platform that both EU and NATO countries can join – is a good focal point for such work, and can share its know-how and provide technical assistance.

- Ensure that national domestic and foreign intelligence services (or their equivalents) are legally allowed to exchange information with one another, and that they do so in practice: external threats can metastasise at home, so it is important to keep an eye on the full picture.

- Review legislation on political party financing: Ask if parties should be allowed to accept foreign financing; or at least ensure that the origin of any foreign financing is clear and the financing process transparent.

- Ensure that national and European legislation on money-laundering and related issues is in place and obeyed.

- Ensure that law-enforcement officials are aware of the potentially political agenda of Russian organised crime, and are capable of addressing it as such: Law-enforcement personnel should know that Russian criminals are not only stealing, but also potentially working for Russian intelligence agencies. Thus, rank and file police officers should have instructions on when to refer such cases to counter-intelligence units.

Preparedness to fight cyber threats is a separate sub-field. ECFR’s surveys suggest that EU countries have started work on countering foreign cyber threats, but their achievements are so far uneven in quality. To boost their preparedness, EU member states should ensure that they have implemented, at minimum, all the measures below:[36]

- A national Cyber Security Strategy, providing a long-term plan to develop cyber resilience.

- A national CSIRT (cyber security incident response team) to handle cyber incidents.

- A robust cyber security framework – including good standards, advisory services, and regulatory supervision of implementation – that covers the government sector and vital services.

- A plan to educate those who work for the state or are affiliated with political parties in elementary “cyber hygiene”.

- Sound cooperation between the public and private sectors, with a focus on effective information sharing.

- National cyber exercises.

Countering fake news is another important area of resilience – and the debate on how best to do this is only starting. One approach is to address the supply side of fake news, by making Facebook and Twitter limit what they circulate and promote, and preventing people from profiting from the production and dissemination of fake news. Another approach focuses on the demand side, by placing the onus on society and investing in media literacy – so that citizens become more discerning consumers of news. This conceptual debate extends far beyond the question of Russia, but it is already clear that the EU and its member states need to adopt a few preliminary recommendations. They should:

- “Weaponise” information in reverse – that is, explain calmly and truthfully what Russia is doing without minimising or exaggerating the threat. This may help serve as an antidote to both ignorance and paranoia.

- Organise courses that help journalists and editors develop a critical attitude towards Russian media outlets, so that they can distinguish between biased and reputable sources of information. The latter exist and are doing a good job of exposing Russian meddling in the West, among other things.

- Agree on common European positions and policies in areas in which member states would otherwise be vulnerable to Russia. For example, many countries wonder whether they should allow RT and Sputnik to operate in their territory. The UK has contemplated banning RT, while both France and Estonia have on occasion restricted its access to media events. But it can be hard to strip them of their broadcast licences, because national legislation – which handles media issues – may not include suitable provisions for doing so. Even more importantly, such a step would expose a country to Russia’s countermeasures. Here, a common European discussion and common rules of engagement would help a great deal. It is a separate question what these should be. RT and Sputnik are not independent media outlets, and they work in bad faith, but penalising them might start an exchange of media expulsions between Russia and the West. Ignoring and marginalising them is probably more effective.

The measures listed above can improve a country’s resilience a great deal. Yet, from a broader perspective, they are all merely technical issues. Ultimately, the fundamental dimension of resilience is a society’s capacity to have a rational discussion that cannot be easily derailed by conspiracy theories, opportunist spin, or a lack of basic trust. This presupposes political elites that enjoy relatively high levels of trust, political institutions that are independent and credible, state finances that are transparent, media outlets that are not entirely sensationalist, minorities that are reasonably well-integrated, and historical traumas (if any) that have been thoughtfully addressed. Securing all this is a tall order, but it is these sources of resilience that will matter most in the normative war with Russia.

Conclusion: Offence and defence in the normative war

As this Power Audit has demonstrated, the disagreement between the EU and Russia keeps coming back to normative issues – the EU’s world of mutual dependence versus Russia’s defensive insularism; the EU’s horizontal practices versus Russia’s leader-centric power vertical; the EU’s liberal international order versus Russia’s realpolitik. This core normative struggle has entrenched the positions of both powers. Russia has no incentive to accept Europe’s version of world order because it believes that this order will eventually collapse. Yet Europe cannot accept Russia’s version of a world governed by realpolitik and spheres of influence – which would negate the EU’s entire identity, history, and experience – because the EU does not consider it viable either.

Both actors feel vulnerable to the other side’s meddling in domestic affairs. Both are trying to build up their resilience. Both have learned lessons from their interactions with each other between 1991 and 2014, but they still lack an effective strategy for their future relationship.

The EU and its member states need an approach to Russia that translates normative principles into real policy. They need a Russia strategy that extends their current unity into more difficult and long-term issues – not least those involving the eastern neighbourhood, where the normative clash is most acute and dangerous. The EU should try to foster a deeper and more nuanced common understanding of Russia’s trajectory, political processes, policymaking habits, ambitions, and constraints. This understanding should then form the basis of a joint Russia policy that involves member states large and small, north and south, and that is represented in EU institutions. This would present Russia with a solid normative front that both sticks to the moral high ground and is politically viable.

As noted above, EU member states should also invest in their resilience. Part of this will involve relatively simple administrative measures. But the more fundamental components of resilience – such as the credibility of state institutions, political parties, politicians, and the mainstream media – will require a broader effort. If these components are missing, they cannot usually be created in a top-down manner. Still, there are some aspects of resilience that the authorities can strengthen, including by: tackling social inequality and deprivation; engaging with marginalised minorities or fearful majorities; addressing relevant historical myths or conspiracies; countering corruption; and investing in transparency. In general, the authorities need to engage in a frank conversation with society. Some current European leaders, particularly those in France and Germany, are doing remarkably well at this. Others – such as those in the UK (in their profoundly mismanaged approach to Brexit), Poland, and Hungary – remarkably badly.

Offensive measures are important in the normative war with Russia. But, ultimately, the best normative offence is a good defence, which requires the renewal and reinvigoration of the European model. If the West can address its fundamental shortcomings, the threat from Russia will be swept away – just as the success of the Marshall Plan swept away western European communism as a serious force.

This does not mean an effort to return to the 1990s and early 2000s – the supposed heyday for the expansion of European norms. Instead, the Western model needs to adapt to remain viable in a world where power relationships are changing, geopolitical competition is increasing, and global connectedness is growing, but large parts of the population – in the West and elsewhere – feel left out and defensive. In short, Europe needs to restore the credibility of the liberal international order by rebuilding it from the ground up in today’s reality.

In this respect, Russia’s challenge to Europe’s domestic consensus may have come at a good time. By trying to exploit Europe’s domestic divides and weaknesses, Russia has created urgent incentives to address them. Europe has woken up from its complacency. It is time to get to work.

[1] Conversation at Quai d’Orsay, July 2017.

[2] Author’s conversation in May 2018.

[3] For more on this issue, see Vladislav Surkov, “Teksty 97-07”, Evropa, Moscow, 2008.

[4] Confirmed in author’s conversation with Western diplomats and Russian experts, autumn 2015.

[5] Conversation in May 2018.

[6] See “Meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club”, Kremlin, 19 October 2017, available at http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/55882.

[7] For criticism of the “Gerasimov Doctrine”, see Roger McDermott, “Does Russia Have a Gerasimov Doctrine?”, 2016, available at http://strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/parameters/issues/Spring_2016/12_McDermott.pdf; and Mark Galeotti, “I am Sorry for Creating the Gerasimov Doctrine”, Politico, 5 March 2018, available at http://foreignpolicy.com/2018/03/05/im-sorry-for-creating-the-gerasimov-doctrine/.

[8] See Mark Galeotti, “Hybrid war or Gibridnaya Voina? Getting Russia’s non-linear military challenge right”, Mayak Intelligence, 2016.

[9] Interview with Andrei Soldatov, 14 May 2017.

[10] Interview with a Kremlin insider, Moscow, May 2017.

[11] Conversation on 29 June 2017.

[12] Conversation with a Russian expert in Moscow, May 2017.

[13] Conversation with a Russian business insider, December 2017

[14] Interviews with 12 insiders, experts, and journalists in Moscow in May 2017.

[15] Interviews with experts in Moscow, May 2017.

[16] Conversation on 18 October 2017.

[17] A more in-depth exploration of these groups can be found in Susi Dennison and Dina Pardijs, “The world according to Europe’s insurgent parties: Putin, migration and people power”, European Council on Foreign Relations, 27 June 2016, available at https://ecfr.eu/publications/summary/the_world_according_to_europes_insurgent_parties7055

[18] Comments by Mark Galeotti at a discussion in Tallinn in May 2016.

[19] Statement at the Lennart Meri Conference in Tallinn, Estonia, on 13 May 2017. Interviews with civil servants and intelligence insiders in several EU member states, March 2017

[20] For more on this issue, see Ivan Krastev, “The Cold War Isn’t Back. So Don’t Think Like It Is.”, New York Times, 21 December 2016, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/21/opinion/the-cold-war-isnt-back-so-dont-think-like-it-is.html?_r=0.

[21] Author conversation with official at the European External Action Service, September 2017.

[22] Conversations with Western diplomats and Russian experts.

[23] See European Council on Foreign Relations, “EU Coalition Explorer”, available at https://ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer.

[24] Conversations with Italian diplomats and business circles in London in spring 2017, Rome in October 2017, and Turin in December 2017.

[25] Interview with Nicu Popescu, 8 June 2017.

[26] Sergei Lavrov at the Primakov Readings Conference in Moscow, 30 June 2017.

[27] For a deeper elaboration of these dilemmas, see Kadri Liik, “How the EU Needs to Manage Relations With Its Eastern Neighborhood”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, available at http://carnegieendowment.org/2017/08/23/how-eu-needs-to-manage-relations-with-its-eastern-neighborhood-pub-72883.

[28] Conversations with power-holders during ECFR study trip, March 2015.

[29] Remarks at the Primakov readings conference in Moscow, 29 June 2017.

[30] Remarks at an EUISS seminar in Paris, December 2015.

[31] Conversation in April 2018.

[34] Seminar under the Chatham House rule, 3 May 2017.

[35] Remarks at a seminar in London, December 2017.

[36] Interview at Estonia’s Information System Authority. For more information about the institution and its activities, see https://www.ria.ee/en/.

Austria

Russia is feared to be interfering in our domestic politics through: Hacking, propaganda, financing, business ties

Austria generally regards Russia as a partner. Having reluctantly imposed sectoral sanctions on Russia, Austria was the first EU state to host President Vladimir Putin as an official guest following Moscow’s annexation of Crimea. However, Austria has no intention of breaking the European Union’s consensus on sanctions. The country’s reluctance to engage in an assertive EU policy on Moscow stems mainly from economic and energy concerns, given that it imports around 70 percent of its gas from Russia. The small town of Haidach, near Salzburg, hosts the second-largest gas storage facility in central Europe, a successful project jointly operated by Austrian company RAG, German firm Wingas, and Russia’s Gazprom Export.

Austria sees dialogue and engagement with Moscow as the best means to resolve EU-Russia disputes. As such, it is somewhat sympathetic to Moscow’s grievances about western policy in former Soviet states. In 2017, Austria and Russia strengthened their cultural ties – an important part of their relationship – through the “cross-cultural year” initiative, in which each country hosted cultural events relating to, and encouraged tourism involving, the other.

Quotes from the survey:

“Russia’s military activities are above all aimed at deterrence, and are not a worry for our country”