When the weapons fall silent: Reconciliation in Sinjar after ISIS

Summary

The war against ISIS displaced almost 15 percent of Iraq’s population. By September 2018, 4 million Iraqis had returned home – but not the people of Sinjar, including many of the country’s Yazidi religious minority. Their return and reconciliation with one another – through justice, accountability, and the protection of land rights – are vital to maintaining the distinct nature of this multi-ethnic, multi-sectarian district.

Introduction

The multinational war to oust the Islamic State group (ISIS) from its self-proclaimed “caliphate” in Syria and Iraq once dominated headlines around the world. The direct international intervention there in summer 2014 came in response to the extremists’ violent campaign against the Yazidi minority in Sinjar district, in northern Iraq (which the United Nations later deemed genocide). Four years later, ISIS has lost almost all the territory it once openly controlled, reverting to its origins as an underground insurgent force engaged in guerrilla-style attacks. The group is much diminished but not defeated; the destructive legacy of its rule still potent. This legacy is manifest in the hundreds of thousands of displaced Iraqis who have yet to return home. It lives on in the still-growing tallies of the dead and missing, and in the massive destruction – of concrete and communities – yet to be cleared and repaired. History reminds us that the ISIS ideology can and will be resurrected unless it is actively and effectively countered – and that it flourishes in a weak, divided state.

While military campaigns are inherently dramatic, terrifying, and newsworthy, what happens after the weapons fall silent and global attention turns elsewhere is also critical to avoiding cyclical violence and instability. The war against ISIS displaced almost 6m Iraqis, or 15 percent of the population. By September 2018, the number of displaced persons had dropped to 1.9m, the lowest level since November 2014. Four million Iraqis have returned home – but not the people of Sinjar.

Iraq and the international community poured much blood, money, and effort into the campaign against ISIS. Now, they must invest in peace – or, more accurately, a sustainable end to the violence. Key challenges for post-conflict stabilisation in Sinjar’s towns and villages persist in rebuilding communities (and the idea of community); providing security and basic services; addressing public grievances; seeking accountability and justice; fostering local reconciliation; and helping people return home, to live in peace, dignity, and safety with their neighbours (as well as with their emotional and physical scars).

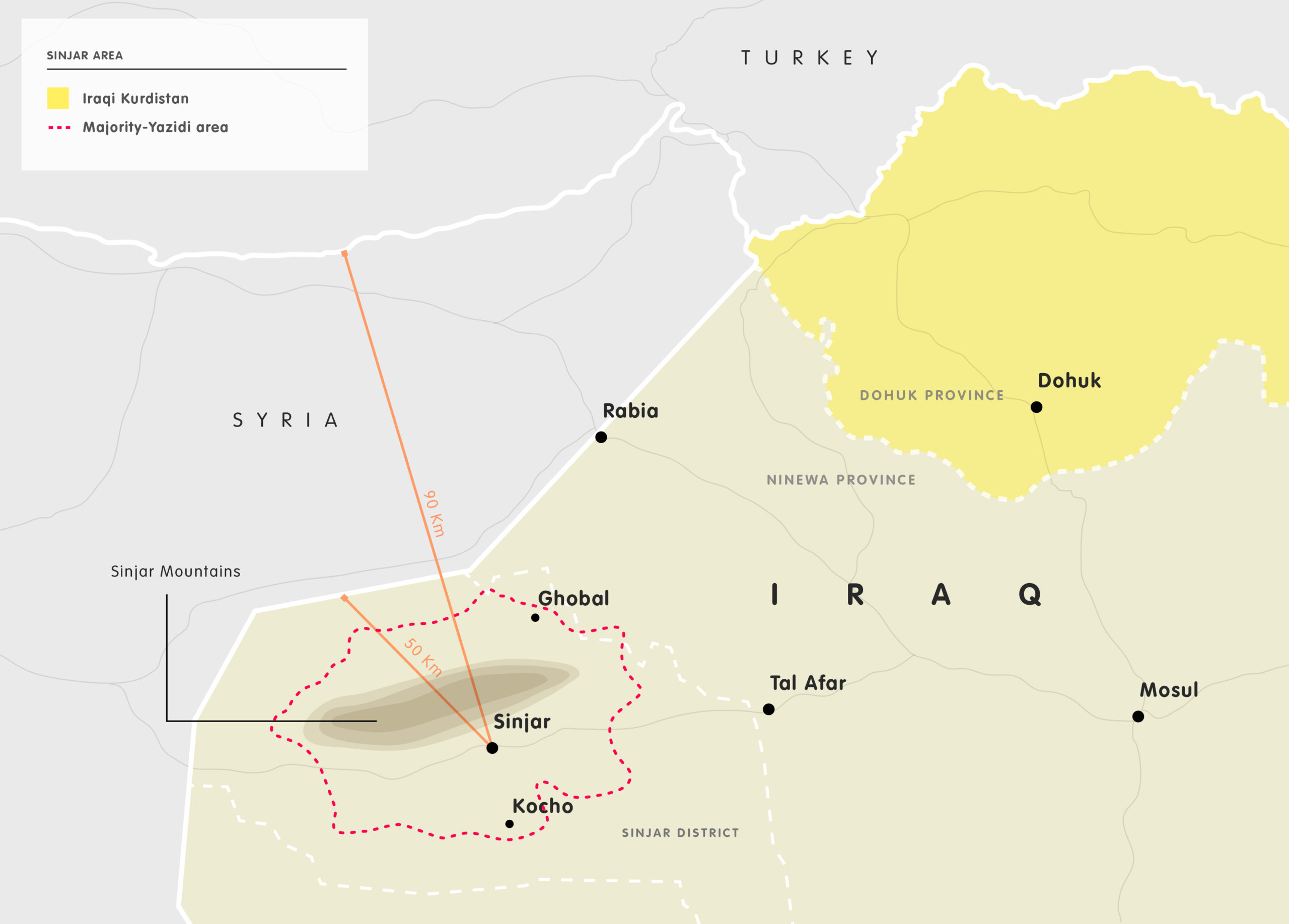

Sinjar – which Kurds call Shingal – is a strategically important district in Iraq’s north-western province of Ninewa. Sinjar borders Syria and is not far from Turkey. The district’s main city, also called Sinjar, and surrounding areas were once home to around 420,000 people, including the majority of Iraq’s Yazidi religious minority – which is largely Kurdish, although some Yazidis do not identify as such – as well as Sunni Arabs, Sunni and Shia Turkomans and Shabaks, Christians, and other, smaller communities. It is a microcosm of Ninewa, where many of Iraq’s ethnic and religious communities have co-existed, sometimes uneasily, for millennia.

Huddled around a 100km-long mountain range that demarcates its northern and southern sectors, Sinjar falls within territory that the Iraqi Constitution classifies as disputed – or subject to claims from both the authorities in Baghdad and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). Although Sinjar is administered as part of Ninewa province (which has Mosul as its capital), the KRG de facto controlled the district from 2003 until summer 2014, when ISIS took over.

Sinjar stretches across myriad political and security fault lines, caught between the competing interests of Baghdad and Erbil; the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK); the Kurdish Peshmerga; the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and its affiliates; Shia-majority Hashd al-Shaabi militias and other paramilitary forces; and local players who powers such as Turkey, Syria, the United States, and Iran actively support or oppose. In Sinjar, there is deep distrust between many Arabs, Yazidis, and Kurds; Yazidis of different political affiliations; Arab tribes; some of these tribes and the state; and various armed groups.

This paper examines some of the significant challenges in Sinjar and surrounding areas; initiatives for helping displaced Iraqis return home safely; the views and aims of stakeholders in the district; current and planned initiatives for tackling problems there; and locals’ perspectives on the foreign and domestic assistance they receive. As Sinjar is one of the most complex and disputed areas in Iraq, helping displaced persons return home safely means resolving – or, at least, attempting to resolve – some of the larger political issues in Iraq. This is a matter of justice and accountability, of land rights, and of maintaining the distinct nature of this multi-ethnic, multi-sectarian district. Failure to address the challenges will likely result in continued instability, social unease, villages that remain empty and derelict, permanent camps for the displaced, and rising migration – with Europe a favoured destination. Sinjar’s local issues require national and regional input and solutions. Those who had a hand in Sinjar’s destruction, including many Western states, are not just morally bound to aid in its social and physical reconstruction – they have a vital interest in doing so.

Downfall

Sinjar’s Yazidis and their Arab and Kurdish Sunni neighbours lived in peace until 3 August 2014. The date is scrawled on the city’s ruins. It is seared in memory. On that day, ISIS militants and their local Sunni supporters overran the district and surrounding areas, prompting Yazidis to flee en masse into the imposing but largely barren Sinjar Mountains they have long considered to be a holy sanctuary. Then ISIS began its siege.

Massacres, forced conversions to Islam, and kidnappings ensued. Militants took women and girls as sex slaves in a campaign of terror that Yazidis describe as either the 73rd or 74th attempt to annihilate them because of their faith (depending on who you ask). Like others before them, ISIS followers regard Yazidis as devil- and sun-worshipping apostates. Yazidism is a closed religion that forbids converts, enforces a strict caste system, brands followers who abandon it infidels, and prohibits intermarriage with non-Yazidis (and even between castes), reinforcing its insularity.

Yazidis were not the only ISIS target in the area. Sinjar’s Christians also fled, as did Shi’ites in nearby Tal Afar and other areas – where some Sunnis turned against their neighbours to aid the extremists. Iraqi Kurdistan’s Peshmerga forces withdrew from Sinjar without a fight, leaving the minorities defenceless until the PKK – stationed in the Qandil Mountains – and its Syrian affiliates, the People’s Protection Units (YPG/YPJ), rushed to their aid. After reaching Sinjar, they quickly trained and deployed a small Yazidi force called the Sinjar Resistance Units (YBS).

Some Yazidis stayed in their homes, unable or unwilling to escape. Others say they were coaxed down from the Sinjar Mountains by their Arab and Kurdish Muslim neighbours. Many never made it home. “They tricked us into returning,” says Ayshan, a Yazidi woman in her forties, who ISIS kidnapped along with 30 members of her extended family after stopping their cars at gunpoint. The militants had set up checkpoints and sent patrols to search for fleeing Yazidi families. “We thought we’d saved ourselves; we fled to the mountain; then they [called and] said there’s nothing to fear – we won’t fight you; we’re fighting the state.”

“We know who they are,” she said. “The person who detained us was a Kurd who lived with Yazidis. My brother said, ‘this is so-and-so’s son. Maybe I can ask him for mercy, to let us go.’ My brother told him, ‘we are neighbours, we are family, we lived together, you can’t do this to us. You are from Sinjar; save us.’” His pleas were ignored.

Tens of thousands of Yazidis were trapped on Mount Sinjar’s dry, sunburned plateau, at risk of dehydration, starvation, and ISIS attacks. Temperatures soared above 50°C. The desperate situation prompted the Iraqi and American militaries to conduct airdrops of food and water (with European assistance), and the US Air Force to strike ISIS positions near the mountain. Southern Sinjar bore the brunt of the ISIS assault. The PKK and the YPG/YPJ carved out a corridor through which to shepherd Yazidis from the mountain to northern Sinjar and westward into Syria. From there, some Yazidis crossed into Iraqi Kurdistan. They were assisted on the journey to Syria by some of the Sunni Arab tribes living in the area – notably the Shammar, who have a presence on both sides of the Iraqi-Syrian border, near the Iraqi town of Rabia. Although some Shammars joined ISIS, Yazidis most often accuse other Arab tribes such as the Imteywits, the Jahaysh, and the Khatoonys of fighting with or otherwise helping the extremists.

Within days of the initial ISIS assault, almost all Yazidi villages in and around Sinjar were empty, with the exception of Kocho, in the south of the district. There, ISIS militants gave Yazidis several days to consider an ultimatum: convert or die. The besieged townsfolk refused to convert. “Until 2 August, our neighbours were all our friends. On 3 August, our neighbours became our enemies,” says Sheikh Nayef Jasim Kassim, leader of the 18,000-strong Mandakan – a Yazidi tribe spread across 11 villages, including Kocho, his home town. “My tribe lives in areas of Sinjar that bordered the Arab tribes of the area. So, my tribe and our villages, my village, bore the brunt of what happened.”

On 15 August 2014, the extremists corralled Kocho’s 1,740 residents into a school, separated men from women and children, and transferred all but 67 of the women and 16 children to Tal Afar via Mosul. The men stayed behind. The women and children were “gifted” or sold to ISIS militants spread across Syria and Iraq. The remaining 67 women, all of whom were elderly, were executed and buried in a mass grave. The fate of the 16 children is unknown.

Almost 400 men and teenage boys were taken in batches in pick-up trucks from the schoolhouse to the outskirts of the village, where they were executed by gunfire. Only 19 survived, protected under the falling corpses. They include a 46-year-old father of three who has for the past four years lived in a camp for the displaced in Zakho, in Iraqi Kurdistan. “I survived, until now I don’t know how,” he says. “The bullets were raining around me. It happened during the day, around noon. They brought a bulldozer to bury us. I realised I was alive.” Seventy-five members of his family were either kidnapped or killed; like many Yazidis, he blames his neighbours. “The Arabs of the area – the Imteywits, Khatoonys, Jahaysh, Shammar, Jabbouri – all the Arabs around us were against us, with the terrorists of Daesh [an Arabic acronym for ISIS].”

In Kocho alone, Sheikh Nayef says, there are 14 mass graves. Of the more than 800 women who were kidnapped, around 600 escaped or were later rescued. The fate of the rest is unknown. Not a single resident of Kocho has returned home.

Displacement and anger

The Peshmerga eventually returned to Sinjar in force. By late 2015, fighters affiliated with both the group and the PKK had, with the aid of US and coalition air power, driven ISIS out of Sinjar city and areas north of the mountain. Two years later, the Iraqi security forces and Hashd al-Shaabi militias cleared ISIS – as well as the Peshmerga – out of the rest of Sinjar, marking the first time since the 2003 US-led invasion that Baghdad (rather than Erbil) was the main power in Sinjar.

Today, Sinjar is a ghost town, with entire neighbourhoods reduced to rubble. The names of the heads of households are spray-painted on the ruins of people’s homes, often alongside “for sale” notices. Around 52,000 people, or 12 percent of the district’s pre-ISIS population, have returned to Sinjar city and the villages north of it. “Nobody knows the level of destruction in the south yet,” a UN-Habitat official says. The organisation plans to conduct field research in southern Sinjar in the coming weeks.

Unexploded munitions and booby-trapped buildings, coupled with the cost of rebuilding, discourage the displaced from returning. The Mines Advisory Group, a British de-mining non-governmental organisation (NGO), has been working in Sinjar city and areas north of the mountain for more than three years. It describes the contamination there as “extensive”.[1] While it has yet to assess southern Sinjar, the organisation anticipates that the area will be in a worse state than the north “because [ISIS] was embedded in those areas for much longer. The longer they were [present], the worse the contamination.” The Mines Advisory Group says that Iraq is the most heavily mined country in the world and that, despite its efforts and those of others, the “contamination will never be completely cleared; it’s impossible with the scale of contamination.”

The streets of Sinjar’s main city are quiet, save for the occasional sound of a power generator in some areas. Basic public services such as water, electricity, and healthcare are insufficient and inconsistent. By September 2018, schools had not reopened. A dizzying array of competing security forces, including US troops operating out of a base on Mount Sinjar, remain in the area.

It is unclear how many Yazidis the ISIS advance and military counteroffensive killed. Unofficial death tolls range from 2,000 to more than 5,000. So far, the authorities have discovered almost 70 mass graves across Sinjar. Of the more than 6,000 Yazidi women and children ISIS kidnapped, around 3,000 are still missing.

Yazidi community leaders say that, since 2003, more than 100,000 Yazidis have emigrated to Europe, Canada, or Australia. Most of those still in Iraq are now in camps for the internally displaced scattered across Iraqi Kurdistan. There are 14 such camps in the province of Dohuk alone. Around 2,500 Yazidi families still live in tents and basic cinderblock rooms on Mount Sinjar, four years after fleeing there. Many remaining Yazidis say they hope to emigrate if given the opportunity. The residents of Arab Sunni towns and villages in Sinjar, some of whom have been accused of siding with ISIS against their Yazidi neighbours, are also displaced, having deserted their villages out of fear of reprisal attacks. Sinjar’s 52 Arab Christian families are also displaced due to insecurity and a lack of services, as well as other factors. “If the Arabs of various Muslim sects don’t return to Sinjar, we as Christians won’t return – and, for the Yazidis, their return is a red line,” a Christian member of Sinjar’s 20-man local council says.

After kidnapping Ayshan and her extended family, ISIS sold her into slavery along with her elderly mother. They escaped ISIS-controlled Aleppo in July 2015. Of the 31 members of Ayshan’s family ISIS captured, all except her four brothers, two of her nephews, and three of her female relatives were eventually ransomed or otherwise rescued. The fate of the others is unknown.

After her escape, Ayshan spent several months in Iraqi Kurdistan, before returning to Sinjar in December 2015. Unlike many other Yazidis, she does not want to emigrate. Her family home destroyed, she now lives in a friend’s house in Sinjar city. “I cannot leave Sinjar,” she says. “My family is from here – their smell lingers; its soil is my homeland.”

Like many Yazidis, she does not want her Arab and Kurdish Sunni neighbours to return to Sinjar or surrounding areas: “they are traitors to us and to the state. If they want to return to their villages, this is a very difficult thing. Let them go live somewhere else far from us; otherwise, the trouble will never end between us if they return … People will seek revenge. Their men and their girls will not be safe. If they return despite our objections, the troubles will not end. Our pain is great. We are wounded. This is very difficult.”

The Kocho survivor’s wife and three daughters now live in Germany, which accepted them within an asylum programme for victims of ISIS brutality. He hopes to join them there. Around 50,000 Yazidis – including the group’s secular hereditary leader, Prince Tahseen Said – have lived in Germany since before ISIS attacked their community in Iraq.

The Kocho survivor says his family will not return to their home town unless the area becomes part of an international protectorate or local Arab tribes move elsewhere. His demands are common. “There is no future for minorities in Iraq,” he says. “There were once Jews here. Where are they now? Our fate is the same: to leave.”

Kocho’s Sheikh Nayef has given the Iraqi security forces the names of around 3,000 local Arabs he suspects of having ties to ISIS, but he has little confidence that the state will investigate and detain them all. Until it does, and until the fate of kidnapped Yazidis becomes clear, he says, reconciliation with his Arab and Kurdish Sunni neighbours is impossible. “Everyone who stayed with Daesh for a long time, they are supporters of Daesh because they did not fear them,” he says.

The Yazidis collectively blame almost all their Arab neighbours (and Kurdish Sunnis) for, at best, failing to resist ISIS or, at worst, joining the group and contributing to its brutality. For their part, Arab tribes such as the Imteywits, the Khatoonys, and the Jahaysh say they are being scapegoated for the actions of some of their members, and that some Arabs died resisting ISIS while trying to help the Yazidis – a sacrifice that they believe has gone unacknowledged.

Will the displaced return?

Iraqi policymakers, as well as local NGOs and peacebuilders, are working to foster reconciliation in small communities torn apart by years of ISIS rule. In some areas, locals manage these efforts on their own, using long-standing tribal mechanisms for conflict resolution. Recent Iraqi history suggests that there is no one-size-fits-all approach, and that community-level solutions must be specifically tailored to each case, taking into account local dynamics and personalities.

The Baghdad neighbourhoods of Sunni-majority Adhamiya and Shia-majority Kadhimiya (home to the holiest Shia shrine in the city) provide a historic example. Located on opposite banks of the Tigris River, the neighbourhoods were once synonymous with the sectarian bloodletting unleashed in February 2006, when al-Qaeda bombed the Shia Al-Askari Shrine in Samarra. A year before that attack, 1,000 Shi’ites participating in a religious festival died in a stampede on Al-Aaimmah Bridge, which links the neighbourhoods, after rumours of Sunni suicide bombers circulated in the crowd. Adhamiya became an al-Qaeda stronghold, while Shia militias established a presence around Kadhamiya and nearby Sadr City. Families were displaced as neighbourhoods became uniformly Sunni or Shia.

In 2008, two sheikhs, a Sunni from Adhamiya and a Shi’ite from Kadhamiya, spearheaded reconciliation efforts. They helped reopen the bridge in November that year and restore ties between the areas thereafter. The sway of these local leaders was critical to drawing a line under the past with little restitution, even though – in Adhamiya, at least – there were grumblings of discontent that alleged criminals on both sides had gone unpunished. Ending violence does not necessarily mean peace, especially if grievances remain and local elites reach an agreement with limited popular participation. (Since he negotiated the reconciliation deal, the Sunni sheikh has survived six assassination attempts – the most recent of them in May 2017.)

The mixed Sunni-Shia city of Salman Pak, south of Baghdad, provides another example. After 2004, al-Qaeda and Shia militias in the area killed Sunnis and Shi’ites while displacing families, until a local Sunni sheikh called a Shia counterpart to ask for a meeting on ending the bloodshed (in the presence of independent Iraqi civil society mediators).

As is common tribal practice, they negotiated compensation, or blood money, for every victim on both sides. But the sheikhs then hammered out another deal: that anyone, be they Sunni or Shia, would have to pay a multimillion-dollar fine if they harmed a member of the other sect, or even uttered a sectarian slur. Yasir Ali, programme manager of the Iraqi Center for Negotiation Skills and Conflict Management’s Mosul branch, was involved in the Salman Pak reconciliation negotiations. Once the deal was worked out, he said, the key issue was securing local buy-in. The two sheikhs “pre-emptively collected money from everybody from all the tribes and put it into a fund. They didn’t wait until somebody said something to collect the money. In this way, everybody would lose money if somebody from their side broke the agreement. The agreement is still holding, and the people live together – and [ISIS] couldn’t get into Salman Pak.” The lesson, Ali says, is to focus on dialogue and close listening, as well as active community participation and investment in the process. Ali’s centre is working to apply the same approach in Sinjar.

In the town of al-Shura, north of Mosul, the Jabbouris are leading an intra-tribal initiative to reconcile the families of suspected ISIS militants with their broader kin, allowing these families to return to their homes. The Iraqi government more often pens these families in camps while it decides what to do with them. According to Baghdad, women and children in the camps face the threat of revenge attacks from relatives angered by their association with the group, and from victims of ISIS. However, Human Rights Watch has described the practice as a form of collective punishment prohibited under international law. Following reports that security personnel and others have sexually abused women and children in the camps, there are fears that the families’ isolation will deepen mutual resentment and further ostracise them – when they should be reintegrated into communities, and psychologically and socially rehabilitated.

Sinjar presents a very different set of challenges. There, complications arise from many local, regional, and international factors; ethnic and sectarian tensions; and, more than anything else, the systematic kidnapping and sexual enslavement of Yazidi women and girls – a crime Yazidis say is much harder to address.

Iraq’s National Reconciliation Committee intends to open an office in Sinjar to establish a direct link with the few residents who have returned. It has formed a 30-member local “council of elders”, which held its first two-day conference in late September 2018. Only 18 of the 30 invitees turned up to the meeting. Nonetheless, the committee has formulated a 13-point road map for Sinjar focused on restoring security and reopening schools, medical clinics, and other public facilities critical to locals’ livelihoods, such as an agriculture office and a grain silo. The road map includes a measure for turning Kocho’s school into a monument to the brutal acts that occurred within its walls, and for establishing a criminal court to register complaints and try cases related to the reign of ISIS in Sinjar.

The idea is to rebuild physical infrastructure first, to encourage people to return home, and only then to tackle the question of social reconciliation between Yazidis and their Sunni neighbours. According to Walid Alomere – head of the National Reconciliation Committee’s Office of Minorities and the government’s point person on Sinjar – to do otherwise would be to risk inflaming Yazidi sensitivities: “it’s very delicate, even the titles we use for conferences and projects is delicate. If I use the word ‘peace’ or something, I’m accused, the government is accused [by Yazidis], of trying to impose a reconciliation with the Arab Sunnis in the area.” The main problem with the government’s plan, he says, “is that the resources spent on the war make rebuilding difficult.”

Iraq has said it needs $88 billion to rebuild after the war on ISIS. An international donor conference in February in Kuwait only managed to secure $30 billion in pledges. Germany promised €500m and the European Union €400m.

Alomere hopes Europe will step up its assistance. It is in Europe’s interest, he says, to help Iraq persuade minorities such as the Yazidis to return home and to maintain the ethno-sectarian diversity of the country – because the alternative for these communities may be exile in Europe. “Many Yazidis migrated to Germany. We need their areas to be in a state that makes them want to return,” he says. “This is an issue of shared interests between Iraq and Germany.”

Other reconciliation initiatives also focus on Sinjar. Local NGOs such as Ali’s work on post-conflict issues stemming from the appropriation of houses; looting; revenge attacks; and the displacement of ISIS families, as well as the victims of the extremists, in Ninewa, Diyala, Kirkuk, and Salaheddine provinces. Working in coordination with Alomere’s National Reconciliation Committee on Sinjar, the organisation has brought Arab and Yazidi stakeholders including women and young people together in workshops (as per donor requirements) on two occasions. The NGO also works in Mosul City and surrounding areas, where it focuses on reconciliation between Tal Afar’s Sunnis and Shi’ites, as well as on reducing tension between returning Christians in Qaraqosh and their Arab and Shabak neighbours. But Sinjar, Ali says, is a particularly complicated problem because “it’s a political issue; a security issue; a central government issue; a conflict management issue – it’s a big crisis.”

The biggest obstacle, he says, is the lack of trust between Arabs and Yazidis, and misperceptions on both sides: “we need a lot of work to change the way that people judge the other side, to remove the generalisations. The Yazidis speak of the Arabs as one bloc; they don’t say ‘the bad people’ within those tribes. It’s wrong thinking. It’s somebody else who raped you, not this sheikh or this Arab man.”

The Shammar tribe, one of the largest in the area, is also involved in independent mediation between Yazidis and other Arabs. Although some Shammars joined ISIS, many Yazidis speak highly of the tribe because it helped them cross into Syria at Rabia. Sheikh Abdel-Karim al-Shammar, a fluent Kurdish speaker from Sinjar, is one of two sheikhs from his tribe who approached the Yazidis this summer offering to help. “Yazidis reject reconciliation at this point, completely reject it,” Sheikh Abdel-Karim says, “so I am moving very slowly on this. It isn’t helpful to rush such a thing.” He asked the Yazidis for a list of demands, which he then forwarded to Baghdad. Top of the list is the demand that local Arab sheikhs disclose the names of alleged ISIS members within their tribe and help retrieve missing Yazidis. “The Yazidis know who harmed them, they have names too, but they want the Arabs to present the names,” Sheikh Abdel-Karim says. “The other thing is that the tribes should work on these kidnapped women and girls, find out who took them, who has them – every tribe can do this.” The Yazidis have also demanded that the government reopen schools, restore electricity and services, and create a court in Sinjar to hear ISIS-related cases and allow people to apply for compensation (among other things).

Deep roots of the crisis

In many ways, Sinjar’s current crisis and the challenge of reassembling its social mosaic are deeply rooted in the pre-ISIS era – not least the former Iraqi Ba’athist regime’s Arabisation policies. Following the 1975 Algiers Agreement, designed to settle Iraq’s and Iran’s competing territorial claims, Baghdad engaged in a campaign of forced demographic change in its ethnically and religiously diverse northern provinces. In doing so, the Iraqi leadership aimed to address the perceived threat that minority groups there might ally with a foreign power (particularly Tehran) against Baghdad.

In 1977, the Iraqi government forced ethnically Kurdish Yazidis to register as Arabs in a national census. The authorities emptied more than 100 Yazidi villages and hamlets, moving some of their inhabitants to new townships on the plains and resettling others with Arabs. The government denied these Yazidis the right to register plots of land in their name, meaning they lacked paperwork that proved they owned their homes (known as TAPU). “It’s like they built on ice; there is paperwork in the local council, people are registered, but no registration in the TAPU,” says Khadida Daoud, a Yazidi lawyer who advises Ninewa’s governor on Yazidi affairs. In practice, he says, it means that “the state can at any time claim [property], and you cannot even demand compensation, because it’s not legally under your ownership.” Daoud fears that this lack of paperwork will complicate post-ISIS compensation claims.

After Saddam Hussein’s fall in 2003, Kurdish forces reclaimed some of this historically Yazidi territory with, Baghdad feared, a view to annexing it to Iraqi Kurdistan – along with other disputed areas such as Sinjar and the oil-rich city of Kirkuk. This outcome now seems unlikely, given that Hashd al-Shaabi groups and the Iraqi security forces recaptured much of the territory in the aftermath of the Kurds’ September 2017 independence referendum. Article 140 and other parts of the Iraqi Constitution include a mechanism for resolving the status of disputed territories, calling for a process of “normalisation” that reverses the Ba’ath Party’s Arabisation policy in the areas, along with a census and a referendum on the future of Kirkuk. Although the initial deadline for implementing the article was December 2007, the government in Baghdad has yet to take any of these steps. The resulting uncertainty about who will rule Sinjar in the long term only heightens all communities’ anxiety about their future.

Other historical factors have also contributed to the current crisis. After it toppled Saddam Hussein, the US replaced his nominally secular Ba’athist regime with a sectarian quota system that made religious and ethnic identity the major organising principle of Iraqi politics. This identity-based system simultaneously guaranteed political representation to small minorities such as the Yazidis and limited the nationwide role they could play. The system ensured that their numbers alone, and their resulting political influence, were unlikely to effect change without the support of stronger patrons from other ethnic and sectarian groups. In this way, the post-2003 Iraqi political system enabled power centres such as Erbil, Baghdad, the KDP, and the PUK to co-opt Yazidis, thereby widening divisions within the minority group. Put another way, disputes between Iraq’s big players have disrupted and fragmented their smaller counterparts, who need to fit within their patron’s political apparatus to amplify their voices.

To be sure, the Yazidis – like most communities – hold a variety of conflicting political views. Some have allied with the KDP or the PUK and cleave to the politics of Iraqi Kurdistan, while others look to Baghdad. Therefore, no one leader speaks for all Yazidis or has the power to make decisions on behalf of the entire community. In addressing Yazidis’ concerns as part of post-conflict stabilisation, it is difficult to identify stakeholders who have significant legitimacy and influence among them.

This is not an issue in Sinjar’s Arab community, because the sheikh at the apex of each tribal hierarchy speaks for his people. As local NGOs and stakeholders have observed, Yazidi tribal leaders cannot reconcile the beliefs of their politically diverse community – beyond common themes such as a desire to know the fate of their missing kin and to seek justice for crimes against them – within a consensus view.

Yasir Ali’s NGO has sought to address the issue by selecting participants for its workshops from across the spectrum of Yazidi society. But even these participants say that, while they are prepared to sit with Arab sheikhs and listen to their views, “it’s not about us; it’s about the people we represent – and they are harder to convince.”

Sheikh Abdel-Karim says he hopes to include many Yazidis in his initiative but, for now, he has chosen Qassem Shesho – a Yazidi commander who refused to withdraw from Sinjar with the rest of the Peshmerga in 2014 and 2017 – as his main interlocutor. “The Yazidis themselves are not in agreement about the way forward – that’s the problem,” he says. “Every side has its own views, and is acting alone. I’m only talking to Qassem Shesho because he’s one of the stronger forces, so I went to somebody who could influence the majority.”

The question of effective and legitimate local representation, as well as the Baghdad-Erbil power struggle – affects every facet of the Sinjar issue, from who heads the local administration to the make-up of security forces in the area. For instance, there are two rival qaimaqams (a position roughly equivalent to mayor) who claim to represent Sinjar. Both men are Yazidis from the area – one is allied to Hashd al-Shaabi forces; the other to Erbil’s ruling KDP.

Qaimaqam Fahad Hamid is located in Sinjar, having been appointed in a temporary capacity by the Hashd al-Shaabi after the recapture of Sinjar and other disputed territories following the Kurdish independence referendum. The Ninewa government in Mosul does not recognise Hamid’s appointment, meaning that he has no legal authority to issue official paperwork, reflecting a split between Baghdad and the Hashd al-Shaabi over Sinjar.

Qaimaqam Mahama Khalil has lived in exile in Dohuk since October 2017, when he followed retreating Peshmerga forces into Iraqi Kurdistan. He says his KDP affiliation cost him his job (although he continues to perform some of his duties), and that he is the legal qaimaqam because Sinjar’s 20-man local council elected him. Predictably, he wants Peshmerga forces to return to Sinjar, and sees Baghdad’s National Reconciliation Committee as “a failed office” that he will not deal with. This local competition over Sinjar impairs federal and international relief and reconstruction efforts, which are caught between more than one administration and centre of power. For instance, the Iraqi Ministry of Justice authorised in May 2018 the opening of a criminal court in Sinjar to register and hear ISIS-related crimes (as many Yazidis demanded). Qaimaqam Khalil has opposed the move, claiming there is no undamaged building to house the court, and that such issues should be addressed in Kurdistan, where “80 percent of Sinjar’s residents” are located. As a consequence, the court exists only on paper.

Schools have also been caught in the political, cultural, and linguistic tussle between Baghdad and Erbil. Since 2003, some schools affiliated with the KRG have offered Kurdish-language instruction, while others have taught the Iraqi national curriculum in Arabic. Both educational directorates are now absent from Sinjar. There are almost no undamaged, fully functioning schools in the area. Due to the uncertainty about whether Baghdad or Erbil will control Sinjar and surrounding areas, neither side appears willing to commit significant resources to repairing and otherwise investing in schools and other basic communal necessities. This gridlock discourages people from returning home.

Chronic insecurity

The KDP-dominated KRG and the government in Baghdad are also engaged in a pronounced security dispute. Iraq’s army and the federal police monitor checkpoints leading into Sinjar. Less conspicuously, Shia-majority Hashd al-Shaabi units have turned abandoned homes in and around Sinjar city into makeshift bases, ignoring orders from Baghdad to withdraw from major towns and cities – especially those ISIS once held. Meanwhile, there are three local Yazidi Hashd al-Shaabi units in the area, each of which answers to a different pro-Iranian commander based in Baghdad. Peshmerga forces under Qassem Shesho are headquartered at the Yazidi shrine of Sharaffadin, at the base of Mount Sinjar; PKK affiliates, including the Yazidi YBS, are deployed on the mountain.

Shesho’s 5,500 fighters (down from 8,000 at their peak) have a tense relationship with the Hashd al-Shaabi, and have engaged in clashes with PKK affiliates. He claims that both rivals “came as occupiers”, and that the “illegitimate forces” affiliated with the PKK must be dislodged from the area. “In the beginning, we loved the Hashd al-Shaabi; we had a common enemy: Daesh,” Qassem Shesho says, “but they looted [Sinjar]. That’s the truth. We didn’t see anything except respect from the Iraqi army. They came to protect us.”

The role of the regional and international backers of various fighting forces in Sinjar further complicates the situation. For instance, Qassem Shesho is a proud member of the KDP. The group briefly detained one of his relatives, Haider Shesho, an affiliate of the PUK, in April 2015 for attempting to form an independent armed Peshmerga unit early in the Sinjar crisis.

Qassem Shesho’s Peshmerga forces vehemently oppose PKK affiliates, including the YBS. The US supported both the Peshmerga and the YBS (as well as the YPG/YPJ) in the fight against ISIS, despite the fact that it regards the PKK as a terrorist organisation.

NATO member Turkey, meanwhile, is allied with the (US-backed) Peshmerga against (US-backed) PKK affiliates in Iraq. Since November 2015, the YBS has received funds through the same Iraqi central government agency that pays the salaries of Hashd al-Shaabi fighters. Earlier this year, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan warned that his country would conduct an all-out offensive in Sinjar to combat PKK affiliates there, a threat Baghdad saw off with a rapid deployment of troops to the area.

The Turkish air force has struck pro-PKK fighters in Sinjar – most recently, Zaki Shengali, a prominent Yazidi commander who it killed in mid-August. The hundreds of YBS fighters, both men and women, who stood in formation during Shengali’s funeral on 18 August in the beige dust of Mount Sinjar were all in their teens or early twenties. They mourned alongside a few carloads of PKK members from Syria who the authorities had permitted to enter Iraq. Stationed at a border post various Kurdish forces once controlled, Iraqi army troops denied entry to most of the Syria-based, pro-PKK group that travelled to attend the funeral – a move Qassem Shesho applauded. The Peshmerga commander wants Baghdad to stamp its authority on the border.

For Qassem Shesho, negotiating a security agreement between Baghdad and Erbil is the first step to securing the kind of calm in the area that will encourage displaced families to return home. “They will find an agreement – they must, because if they don’t they will both lose,” he said. “We are Peshmerga, soldiers, and politics is not our business, but neither [Kurdistan] nor the central government will succeed here if they don’t reach an agreement. We are all Iraqis.”

However, many Yazidis have little faith in either Baghdad or Erbil to ensure their safety, given that both the Peshmerga and the Iraqi military initially crumbled as ISIS stormed across Ninewa province in summer 2014. Instead, they want international protection – or the capacity to protect themselves with minimal interference from stronger patrons. Among some Yazidis, there is deep enmity towards the KDP for abandoning Sinjar in 2014, and for its one-party governance of the area since 2003 – factors that drove some of them to join the YBS or the Hashd al-Shaabi.

Ali Serhan Eissa, also known as Khan Ali, commands the Lalish Brigade of the Yazidi Hashd al-Shaabi. He wants Yazidis to protect Yazidis: “after 2003, the Americans handed us over to the KDP. The Iraqi state hasn’t considered us first-class citizens since 2003, and Kurdistan sells us every few years for [KDP] interests based on what’s happening between it and Baghdad. We are a political football caught between them,” he says. “We want to protect ourselves because the central government and the Kurds failed in the past to protect us, and we paid the price.” He fears that the plethora of competing forces in Sinjar threatens its stability. But if every group feels it must protect its own people – its co-religionists or ethnic kin – then what of Iraqi nationalism and the sense of broader statehood?

Arabs’ demands

The various Arab tribes from Sinjar and surrounding areas have their own security concerns. Displaced across Ninewa province and areas further south, they left behind many towns and villages that remain empty to this day.

The Imteywits have lived in Sinjar for centuries, mainly in 28 villages clustered within a 1,000-sq-km area. Today, most Imteywits live in camps for the displaced across Ninewa province, or in rented apartments in Mosul and other Iraqi cities.

Tribal leaders have compiled a list of 653 kinsmen who either joined or supported ISIS, declaring them outcasts whose death or injury the tribe would not avenge. They have also expelled the families of ISIS members and forbidden them from living with other Imteywits. They have submitted the wanted list to the relevant Iraqi security forces.

Sheikh Salah Imteywit, deputy leader of the 43,000-strong tribe, says that it is not “fair that our tribe is branded ‘Daesh’ because of these 600 people. They are less than one percent of us. It’s insulting.” He says that Imteywits and other Arabs stayed in their homes in areas ISIS controlled not because they were complicit in the group’s crimes but because it restricted movement and forbade Muslims from leaving for what it called “the lands of the infidels”. The Imteywits say they have proof – names and dates – that their fellow tribespeople risked their lives to help Yazidis escape ISIS territory to safety, and that they share the Yazidis’ demand for justice against those who harmed them. “We understand they are in pain, but why are we paying for the crimes of others?,” Sheikh Salah says. “They want and deserve justice from Daesh, but we are not Daesh.”

Yazidis have conducted several revenge attacks on Imteywits – the most grave of which involved the abduction and killing of 52 men, women, and children in June 2017 as a Yazidi Hashd al-Shaabi unit transferred them out of Sinjar. Human Rights Watch claims that the Yazidi Ezidkhan Brigades were responsible for the crime. Yazidis have reportedly abducted and killed at least another 30 Imteywits.

The Imteywits, Sheikh Salah said, have not returned home “because of the armed Yazidi presence and dominance in the area. The state must resolve this so that the displaced can return. There must be security.” He expects his tribe’s displacement to be temporary, saying that it will not forsake its land even if some Yazidis want the Imteywits to relocate elsewhere: “It’s not up to them. Who are they to deny the Imteywits and other Arabs from living in Sinjar? They are a minority. Yes, they are victims of Daesh but so are others. We have 159 casualties at the hands of Daesh: sheikhs and officers and policemen and civil servants. What about the crimes that the Yazidis committed against Imteywits?”

Sheikh Salah, representing the Imteywits, has offered to meet Yazidi leaders to negotiate a resolution, a gesture that has not been reciprocated. “We are ready and serious to sit at the negotiating table to give everyone their rights,” he said, but “the Yazidis are not one voice, one head. There are big disagreements among them, and until the state controls Sinjar, there is no stability.”

The Jahaysh tribe claims that armed Yazidis abducted 38 of its members, killing at least 21 of them. Conducted on 25 January 2015, the attack forcibly displaced the residents of 12 Jahaysh villages. Six of the villages are sandwiched between Yazidi hamlets Guhbal and Borak, and the lands of the Shammar tribe in Rabia.

The Jahaysh say that, as ISIS rampaged through the area in summer 2014, they helped hundreds of fleeing Yazidis reach the Shammars along the Syrian border. “How did they get to the Shammar when our lands are between them and the Shammar?,” a displaced Jahaysh resident from one of the six villages said. “They didn’t fly over us. If we are all Daesh, like they say, why did we help them?”

The villages are poor, comprising widely spaced mud-brick homes. In five of the villages the author visited in late August 2018, every dwelling, with the sole exception of mosques, had been destroyed using bulldozers and other heavy machinery. The Jahaysh blame armed Yazidi militias for looting and wrecking their homes, and the abduction and killing of their kinsmen. They blame one Yazidi in particular: Qassem Shesho. The Jahaysh fear that the destruction of their homes is intended to permanently displace them and ensure Kurdish dominance of the area.

In Chiri, one of the 12 Jahaysh villages, only one local that armed Yazidis abducted returned home alive. The 55-year-old, who speaks Kurdish, says he heard Qassem Shesho order his fighters not to kill Arabs, and saw Shesho’s men use jerry cans of fuel to set homes ablaze. After Shesho left, fighters took several Arab men from Chiri to a neighbouring Yazidi hamlet and killed them there. The man says he only survived because one of the armed Yazidis recognised him as someone who had helped his family cross into Syria. “I was saved by a Yazidi whose family I saved. He drove me back home; I got my wife and family, and we fled.” The survivor has not returned to the ruins of his village – although some Jahaysh did so earlier this summer, after the Iraqi army moved closer to the area, to man a border post at Rabia.

Like the Imteywits, the Jahaysh have also cast out ISIS members and submitted their names to the Iraqi authorities (they claim that there were only 35 such people in their tribe). The Jahaysh say that the accusation they all supported ISIS endangers them in other ways, too. They fear that the state is rushing trials of alleged ISIS members, using the testimony of secret informers against the accused, obtaining confessions under torture, and hurriedly handing down death sentences.

Sheikh Falah Jahaysh, the tribe leader’s younger brother, bristles at the Yazidis’ generalisations about his people. “We want one of them to say, ‘yes, you harmed this Yazidi and that Yazidi.’ We need proof. We have proof we helped; they must provide proof we harmed,” he says. “Who destroyed our homes? It wasn’t all the Yazidis – it was some of them, but we don’t blame all of them. They shouldn’t blame us all for Daesh.”

The demolished Jahaysh villages are near five Shammar villages whose residents Peshmerga forces displaced. The Peshmerga erected an earthen berm around land they confiscated in the Shammar villages, de facto annexing the territory to Iraqi Kurdistan despite the fact that it is in Ninewa province rather than the KRG. The Shammar say the KRG has prevented them from returning home. (Iraqis who are not from Kurdistan require a residency card to enter the three provinces that comprise the KRG.)

Qassem Shesho does not deny that he was in the Jahaysh villages in January 2015, but is inconsistent about whether his men participated in killings and destruction of property there. “I swear if I had been there and done what they said I did, I would have killed thousands of them. I wouldn't have left any of them. I personally have 42 lawsuits against me in Baghdad [filed by Arab tribes] – let them become 142. We didn’t kill any of them, except [for] a few dogs.”

He blames other Kurdish and Yazidi forces but says that, in any case, “90 percent” of local Arab tribes are ISIS members or sympathisers, and are collectively lying about the whereabouts of missing Yazidis. “I only burned three homes with my own hand – only three,” Qassem Shesho said, claiming that the Jahaysh properties belonged to ISIS members. “I burned them so that they wouldn’t return, but I didn’t harm any Arab person, not one … If somebody [else] had lost family members and did something, well …”

Shesho is the main Yazidi interlocutor in Sheikh Abdel-Karim’s mediation initiative involving Arab tribes. The Jahaysh distrust him due to his views, and reject the mediation role of the Shammars because they have “old issues” with them. Sheikh Abdel-Karim acknowledges that some Yazidis committed crimes against the Imteywits and the Jahaysh. And he understands their fear of returning: “revenge can’t be eliminated as a threat until there is reconciliation,” he said. “It’s very complicated and complex.”

Yazidis’ demands

Established in Dohuk province in November 2014, the Sharya camp for the displaced is home to more than 16,000 Yazidis from Sinjar and surrounding areas. There are three key reasons why some residents say they cannot go home: insecurity, given the multitude of armed factions there; a lack of services, and of compensation for destroyed homes; and anger at, and fear of, their Arab neighbours. Many express a desire to emigrate, and for Arab tribes to remain exiled from Sinjar. “If we return, we fear that in a few years the same thing will happen again. If you live surrounded by enemies, it’s difficult,” a Yazidi man in his forties said. “When the government is weak, we will be attacked again.”

Khider Domle – a Yazidi member of the peacebuilding centre at the University of Dohuk, and of NGO Sanad for Peacebuilding – says that many Yazidis consider it premature to talk about reconciliation and return while some of their persecutors are at large and the fate of thousands of kidnapped Yazidis remains unknown. He thinks that, in focusing on reconstruction and restoring services, the Iraqi government has its priorities backwards: “for people, what does that mean, ‘rebuilding’? That I will rebuild your house, but that Arab guy who participated in killing your father, killing your brothers, raping your sister – he’s 500 metres away and has returned and is living as if nothing has happened? Would you go back? Justice first.”

For Yazidis, the sorest spot is the issue of kidnapped and still-missing women and children. The Office of the Kidnapped in Dohuk is one of several organisations trying to rescue female captives of ISIS, sometimes paying ransoms for their release. For those who have been freed, the Dohuk Survivors’ Centre, in collaboration with the Dohuk Health Ministry, provides free physical and psychological support – but community leaders say more is needed.

For its part, the Ninewa governorate distributed a one-off cash payment of 560,000 Iraqi dinars ($468) to each of 1,710 female survivors. It has also approved plans to establish a centre for survivors – to provide psychological and social support – but the facility has not been assigned a budget. “What is the point of having approval for projects on paper and nothing tangible on the ground?,” said Daoud, the Ninewa governor’s adviser on Yazidi affairs. He wants the authorities to grant survivors access to the social security network, “like widows, the divorced – or to consider them like former political prisoners. In Iraq, former political prisoners get a pension and other preferential services.”

Aside from their humanitarian and moral importance, efforts to find enslaved Yazidi women and children, and to help freed Yazidis heal and reintegrate into society, have an impact on reconciliation. Many Yazidis say that these women must consent to any initiatives involving local Muslims, arguing that survivors should be the main stakeholders in any reconciliation because of the suffering they have endured. However, the survivors are not part of a single organisation or group.

Some female survivors say that, if nothing else, the least the Iraqi authorities could do is acknowledge the difficulty of their predicament and relax paperwork rules that require a male relative’s signature. As it stands, Yazidi children born in captivity (as well as Arab children whose fathers are missing) cannot be officially registered and issued identification papers unless their fathers submit the paperwork. As one female Yazidi survivor said of attempts to register her little brother, “we tell [bureaucrats] the child’s father was kidnapped, that he can’t fill out the paperwork. They insist the father be present. I wish he were present more than they do, but he’s not. What can we do? They don’t help with anything.”

Like some other Yazidi rape survivors, the 19-year-old says she is also “very tired” of NGOs that “open my wounds every time they talk to me … They say we will help you. Where is their help? I swear there have been many NGOs and none of them helped.” She has not received psychological support and fears leaving her home in Sinjar in case she sees “any man with a beard. They scare me. I don’t want to see anyone who looks like Daesh.”

Her fears hint at the deep emotional and physical wounds Yazidi survivors live with. Like many Middle Eastern communities, Yazidi society attaches a powerful stigma to rape victims – albeit one that Yazidi spiritual leader Baba Sheikh has significantly mitigated using a doctrinal amendment. The amendment stipulates that freed female captives should be welcomed back into a religion that previously cast out anyone who had sexual relations – forcibly or willingly – with someone outside the faith.

Baba Sheikh’s younger brother and the manager of his office, Hadi Baba Sheikh, says that he prioritises reducing Yazidis’ pain, followed by securing justice and then combating perceptions of collective Arab (and Kurdish Muslim) guilt for what befell his people. He seeks wider recognition of the fact that many Muslims risked their lives to save Yazidis.

While he demands justice for his people, he fears that the Iraqi state’s approach to punishing ISIS members will only perpetuate the cycle of violence in Sinjar and elsewhere: “I am for reform and reconciliation. If I am a terrorist and you reform me, it’s possible my children will be reformed, but if you kill me, hand me a death sentence and confiscate my property and possessions, what have you taught my children and what will they become? They will become terrorists, and this is why terrorism persists in Iraq.”

He believes that Sinjar’s social mosaic can be pieced back together if the Iraqi state imposes its authority in the area – and that state weakness helped enable the rise of ISIS: “there isn’t a state in Iraq; Iraq isn’t a state with rule of law, and strong authority. If it were, this would not have happened.”

Still, his personal experience also highlights the difficulties of forming a united Yazidi front to address the community’s shared concerns. Hadi Baba Sheikh, who is widely perceived as being close to the PUK, says it is essential to deal with the Iraqi government, while his nephew, Baba Sheikh’s son, will not talk to Baghdad. “He deals with Kurdistan, I am concerned with Iraq,” Hadi Baba Sheikh says. “Our family is divided.”

Troubled reconciliation

The brutal reign of ISIS in Sinjar exposed rifts old and new. The disputed status of the district, caught between the competing interests of Baghdad and Erbil, has politicised reconstruction and the return of the displaced. People need homes and basic services to return to, but the question of compensation and reparations – and who will pay for them – is key. So too is establishing proof of private ownership.

Homes must be cleared of mines and other physical threats. Civilians must feel secure enough to return, confident that the various security forces there will not harm them or come to blows with one another. The fear of revenge attacks is great, especially among Arab tribes.

Reconciliation remains a distant thought relative to more immediate, painful concerns, such as determining the fate of missing Yazidis and Arabs, and securing justice for victims. The hurt and suspicion – on all sides – runs deep. Dialogue and trust are lacking, both between communities and within them. There are several levels of post-ISIS conflict – not just between Arabs and Yazidis and Kurds but also between their local, national, and international backers or foes.

The question of legitimate representation is crucial. Although several of the Arab and Yazidi stakeholders working with Yasir Ali’s NGO (such as Hadi Baba Sheikh) were invited to the National Reconciliation Committee’s September conference, they did not attend. Neither of the two qaimaqams were present. Only one Arab sheikh, an Imteywit who does not have the authority to speak on behalf of the tribe, was there. The Yazidis accepted his presence because his brother and other relatives were killed resisting ISIS. Alomere says he intends to establish a separate council of tribal elders from Sinjar.

Hadi Baba Sheikh refused to attend the meeting on the grounds that it lacked influential participants: “you can’t go and look for a weak sheikh in the Imteywit just for a photo op, to broadcast on television and claim that this person represents the tribe and is willing to engage in reconciliation efforts. And they do the same thing with the Yazidis. They bring young women – with all due respect to women – but they bring ones who cannot impose decisions on others in the community. You need people with influence.”

Of the five women invited to the September conference, only one participated – a young dental student. “They choose women who are silent, whose presence will fill a quota,” said Hanadi Attieh, gender director of the National Reconciliation Committee. She says there are many qualified, outspoken women, but that her colleagues suggested they form a parallel women’s committee – a move she rejects. “Sinjar is a women’s issue; women were particularly victimised and targeted, kidnapped … They should also be represented [in a meaningful way], raising their questions and their voice. Women should be informed about all the issues and involved.”

The National Reconciliation Committee is prepared to add more members to its Sinjar council of elders, and has called for suggestions in doing so. Its September meeting prioritised (in no particular order): opening offices in camps for the displaced to coordinate safe returns with the security forces; resolving the duplicated administrative issues to more effectively restore services, including through a vote for a new qaimaqam; restoring security, partly through increased de-mining efforts, the formation of a joint operations room representing all armed groups in Sinjar, and measures to allow locals to volunteer for the security forces; and pursuing justice through the return of kidnap victims, compensation, the establishment of a special court for Sinjar, and the identification and formal burial of victims found in mass graves.

The committee intends to hold monthly meetings to evaluate its progress. Several experienced Iraqi mediation experts, as well as stakeholders in Sinjar, have cautioned that the problems in the district are too important to allow the usual Iraqi and foreign attempts to measure progress. They describe these efforts as photo opportunities and empty exchanges of praise in hotel conference rooms. “Foreign states seem to stress how much money they spend on something: ‘we put X amount towards this project without real concern for the impact of that project, the real impact’. The main thing is that the paperwork has been done but, as for the impact, who cares?,” one Iraqi mediation expert says. “Or when NGOs bring a Christian who may have nothing to do with Daesh – not even be its victim – and Sunnis from an area, they take a few photos and everyone goes home. But what was really achieved? Was anything actually solved? No, but they ticked the boxes.”

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Iraqi Center for Negotiation Skills and Conflict Management and Iraq’s National Reconciliation Committee for their time and expertise, as well as all those interviewed for this report in Sinjar, Mosul, Dohuk, Baghdad and various places in between.

About the author

Rania Abouzeid is a Beirut-based journalist and the author of No Turning Back: Life, Loss, And Hope in Wartime Syria. She has covered the Middle East and south Asia for well over 15 years, and is the recipient of numerous prizes for international journalism, including the Michael Kelly Award and the George Polk Award for Foreign Reporting.

FOOTNOTES

[1] The organisation did not respond to the author’s enquiries about how much territory it has cleared and the areas it intends to work in.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.