What Europeans really feel: The battle for the political system

Summary

- Politics today is about emotions as much as ideas – but few people have tried to uncover what Europeans really feel.

- Levels of support for membership of the European Union are currently high, but so too is pessimism about the future of the European project.

- In every member state except Spain, most voters believe it is possible that the EU will fall apart in the next 10-20 years.

- Shockingly large proportions of Europeans in every member state believe that war between EU countries is possible – with young people the most convinced of this.

- An emotional map of Europe shows splits between people who feel optimistic, appreciated, and safe, and those who feel stressed and afraid.

- There is a long-running conflict centred on the way Europeans feel about democracy, the economy, geopolitics, and the climate.

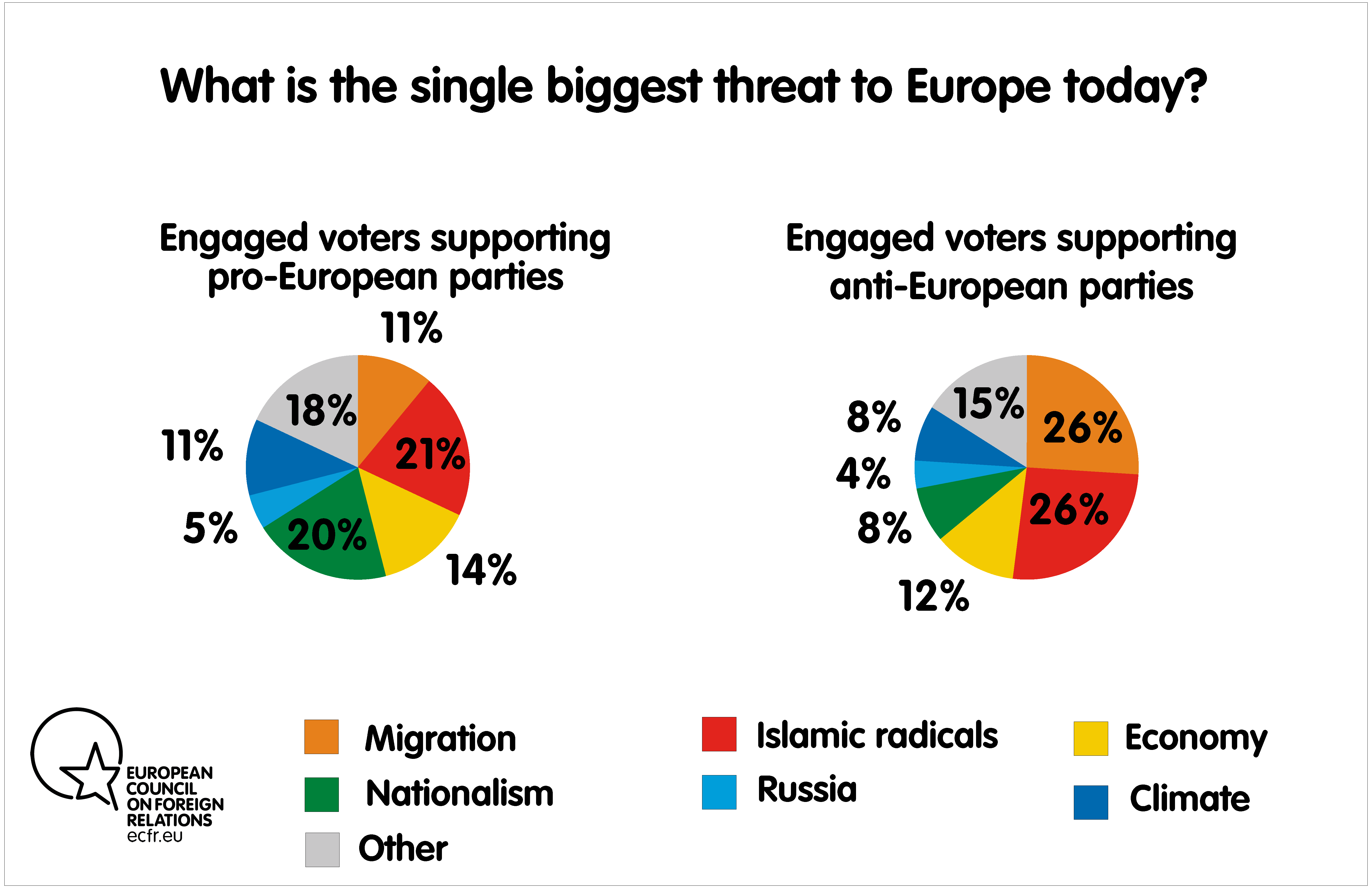

- All European elections have become split-screen events, dividing optimistic voters who seek cooperation from pessimistic voters who live in a world of competition.

- Pro-European parties now need an inclusive, compelling story about the future – one based on a more emotional understanding of citizens – to “connect with” rather than “convince” disenchanted voters.

Introduction

See coverage in ![]() The Guardian,

The Guardian, ![]() La Stampa,

La Stampa, ![]() Süddeutsche Zeitung,

Süddeutsche Zeitung, ![]() Le Monde,

Le Monde, ![]() Gazeta Wyborcza

Gazeta Wyborcza

In the year of the European Parliament election, the biggest challenge for the European Union is not Euroscepticism and anti-Europeanism but Euro-pessimism.

This may sound melodramatic – but it points to a fundamental paradox. Eurobarometer reported last month that two-thirds of EU voters believe that “EU membership has been positive for my country”, the highest proportion since 1983. Yet, despite this surge in support, most EU voters believe the European project could collapse within the next 10-20 years. Even more shockingly for the EU – the world’s best-known peacebuilding initiative – 28 percent of EU voters now see a war between EU member states as a realistic possibility (a share that, in many countries, rises to more than 50 percent among young voters).

Rather than a simple split between pro-Europeans and nationalists, there is a much longer-running, much deeper conflict under way – one centred on the way Europeans feel about the democratic system. And this battle is as much about people’s emotions as their ideologies or their attitudes towards facts.

To understand the reasons for this, the European Council on Foreign Relations commissioned YouGov to carry out a survey of over 60,000 voters’ feelings about their communities, agency, and future, as well as the world around them. Using large sample sizes, the survey took place in late March and early April 2019 in 14 countries: Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, and Sweden. ECFR also organised focus groups in France, Germany, Italy, and Poland that included representatives of various groups (selected according to their beliefs about whether the national and European political systems were broken). This paper lays out the findings of the survey and the implications for the future of the European project.

Conflicted Europe

By reputation, pro-Europeans are meant to believe in consensus, reason, logic, and mutually beneficial cooperation. Established facts and shared knowledge are central to their decision-making process. In their world, the study of data is a peacebuilding exercise in and of itself – as its purpose is to show that there is a common truth.[1]

But data from ECFR’s recent poll shows that, in present-day Europe, there is no common truth. Firstly, there is a sharp difference between people’s lived reality and their views on the future of the European project. A European identity remains very important to EU voters. Indeed, ECFR’s survey found that, in every member state, only a minority of voters felt that this identity was less important than national identity.

The survey also revealed why EU citizens value membership of the union, by asking them to identify what would be the biggest loss if the union were to disintegrate. The most common response concerned the benefits of the single market – the ability to live, work, and travel in other EU member states – and, to a lesser extent, the euro. The second most common response concerned the EU’s capacity as a global actor in a world dominated by continent-sized powers – which facilitates cooperation on security and defence. Respondents also regarded multilateral cooperation on tackling climate change as an important function of the EU.

But, interestingly, their choices focused on not only what the EU provides but also what it stands for. The third most common response concerned a commitment to European values: the protection of democracy and the rule of law.

And yet, as noted above, most Europeans think that the EU could collapse. In every member state except Spain, most respondents thought it likely that the union in its current form would fall apart in the next 10-20 years. In no EU country is the share of voters who hold this belief less than 40 percent.

The EU was founded in the aftermath of the second world war to bind European countries together so closely that conflict between them would become impossible. However, as mentioned above, the argument for the EU as a peace project has lost much of its capacity to generate support for EU membership. It certainly did little for the remain campaign in the lead-up to the United Kingdom’s 2016 referendum on whether to leave the EU. As ECFR’s survey showed, peace in Europe has become so normal that most people simply no longer believe that the EU serves this purpose.

But Europe is changing on this front too. Shockingly, just 30 years after the Berlin wall fell, significant proportions of Europeans in all member states now believe that war between EU member states is a realistic possibility once more.

There is a greater tendency to hold this belief among supporters of far-right parties, particularly Rassemblement National in France, the Freedom Party of Austria, the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands, Jobbik in Hungary, and Golden Dawn in Greece. Most of those who abstain from voting or are undecided about whether to vote share this belief. However, pessimism on the issue is also relatively high among supporters of mainstream parties – with the notable exceptions of La République En Marche! in France, the Labour Party in the Netherlands, and the Greens in Germany.

Most surprisingly, young voters are more likely than their older counterparts to believe that there is a real possibility of war between EU member states. The shares of those aged 18-24 and the general voting population that hold this belief are, respectively, 51 percent and 38 percent in the Netherlands, 46 percent and 35 percent in France, and 51 percent and 31 percent in Romania.

For those who believe that war between EU member states is now a realistic possibility, the reality of contemporary Europe is one of competition and conflict rather than cooperation. It is not that they think that war will break out tomorrow, but that they perceive a logic of combat, competition, and conflict in European society.

This changes the dynamics of the clash of discourses that occurs during an election. People who perceive a threat of war think – and, crucially, feel – differently about themselves, their aims, and their priorities than those who do not. Their desired outcome in any interaction is total victory rather than cooperative resolution.

In this world of feelings, facts and knowledge matter less than excitement, mobilisation, and commitment. As recent European elections and the Brexit referendum have shown, political appeals based on shared experiences – particularly those of loss, exclusion, and rejection – are especially effective in unifying and mobilising groups of people. Debate can be replaced with rhetoric, and facts with passion, in an environment in which speedy initiatives and reactions take priority over the time-consuming evaluation of alternatives and careful, cautious responses.

In this context, ECFR’s survey data is best understood as “market intelligence” – volatile, highly responsive to recent events, and useful for a limited time only. It is best “felt” like a temperature rather than “evaluated” like a report.

ECFR’s survey was designed to discover Europeans’ feelings about their lives. As the chart below shows, many of them are now fearful and stressed. Nevertheless, there are countries in which optimism predominates.

A comparison of the feelings of respondents in Germany and France – the EU’s largest and most powerful member states – shows the extent to which people’s emotions cannot be understood as a simple response to facts.

French people are more than twice as likely as Germans to describe themselves as afraid; conversely, Germans are more than twice as likely as the French to describe themselves as relaxed. This feeds into other significant differences: Germans are far more likely than French people to describe themselves as “optimistic”, and the French far more likely than Germans to describe themselves as “pessimistic”.

In Spain and Italy – southern European countries that have suffered the effects of the eurozone crisis in the past decade and, more recently, have experienced rises in migrant arrivals – two of respondents’ top three descriptions of themselves were “stressed” and “optimistic”. But there were radical differences in the other one of these top three descriptions: “happy” in Spain and “pessimistic” in Italy. Spaniards were more than twice as likely as Italians to describe themselves happy, while Italians were more than twice as likely as Spaniards to describe themselves as angry.

Poland and Hungary also demonstrate how emotional responses can differ between member states despite common experiences. Both are powerful central and eastern European countries that have a strong influence on the EU, independently and as part of the Visegrád group (which also includes the Czech Republic and Slovakia). Optimism is high in both countries, but Poles are much more likely than Hungarians to be afraid, while Hungarians are much more likely than Poles to be stressed.

Of course, national perspectives are far from being the only thing that matters here. Across Europe, female voters are more stressed, and often less optimistic or relaxed, than their male counterparts. And, contrary to stereotypes, young Europeans have relatively little hope. Strikingly, ECFR’s data suggests that stress declines with age: 36 percent of those aged 18-24 describe themselves as stressed, whereas only 17 percent of those aged 55 and over do so. In all 14 countries the survey covered, those in the 18-24 age group were most likely to identify safety as their biggest concern for the future. In many states, people in this group were more likely than the average voter to see a war between EU states in the next ten years as a realistic possibility – 51 percent compared to 38 percent in the Netherlands; 46 percent compared to 35 percent in France; and 51 percent compared to 31 percent in Romania.

Yet, even though young people are more stressed, they are also happier. This may suggest that stress has become normal in modern Europeans’ lives. Indeed, 33 percent of those aged 18-24 described themselves as happy, while only 21 percent of those aged 55 or over did so. This relationship between happiness and age is particularly pronounced in Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Romania, and Slovakia.

Young Europeans seemingly do not believe that the political system can resolve the problems that cause their stress. In every member state, the percentage of young people who plan to vote is lower than that of the population as a whole – in many cases, significantly so.

One interesting, complex emotional group comprises dissonant voters who identify themselves as both stressed and optimistic. They account for 18 percent of all Europeans (calculated on the basis of their presence in the five largest member states), and as much as 26 percent of the German voting population. Dissonant voters seem to characterise Europeans’ emotional state, seeing the current situation as challenging but remaining hopeful about the future.

The key question, then, concerns what Europeans’ views of their emotional state indicate about their engagement with the political system.

Europeans of war, Europeans of peace

There are currently two emotional Europes – an optimistic Europe of peace and a more pessimistic Europe of war. Although they represent two separate realities for EU citizens, they are not geographically distinct. People’s sense of belonging to one part of Europe or the other is not the result of predictable, rational demographic or social indicators but rather of how they feel and how they believe the world works. And there is a profound difference between feeling that Europe is “at peace” or “at war”.

Around half of EU voters – 187 million people – still live within the European peace project. Believing in the power of facts and cooperation, these “peaceniks” vote for pro-European parties. The other half live in a Europe of war. This is not war in the traditional sense of two armies facing each in the field, but of a modern form of conflict in which the line between combatants and civilians is blurred, and the key battle is for hearts and minds more than territory. For this half of the population, the dynamics of peacebuilding and reconciliation that characterised the EU in its early years have been replaced by those of continuous conflict.

People who live in a Europe of war divide into two distinct groups. There are those who are comfortable with the situation: 48 million “happy warriors”, who vote for anti-European parties. But there are also 33 million “reluctant warriors”, who are still connected to the European political system and vote for pro-European parties, believing that they must advance a progressive agenda within a dynamic of continuous conflict.[2]

Although it is important that they mobilise both peaceniks and reluctant warriors as part of a pro-European majority, mainstream parties must communicate with these groups in different ways. Reluctant warriors regard a rational, policy-based narrative on shared European values and a common future as irrelevant and out of touch. Equally, the urgent, passionate message of crisis that reluctant warriors believe is needed to address the challenges of today – ranging from nationalism to climate change – will seem hot-headed, empty, and transitory to peaceniks. Therefore, if mainstream parties appeal only to peaceniks, reluctant warriors may decide they have more in common with, or are given more respect by, happy warriors.

The emotions of Europe

Regardless of whether they live in a Europe of war or a Europe of peace, EU citizens face an uncertain future. In What Europeans really want: Five myths debunked, ECFR showed that two-thirds of voters believe that their children’s lives will be worse than their own. Such anxiety about the future manifests in several areas.

Firstly, it has a significant economic dimension. In every country ECFR surveyed, the ability to afford the comforts of life was one of the top two factors respondents saw as ensuring a good future for them and their families. This perception was particularly evident in Austria, France, Greece, Hungary, and Poland. Denmark was the only country in which most people said they sometimes have money left over at the end of the month to treat their families. Across the EU, only a minority of voters believe that young people have more economic opportunities than members of their parents’ generation.

But even more important to their insecurity is the fact that many people feel they are doing less well than those in other EU member states. This shows how, by changing EU citizens’ frame of reference and giving them continent-wide aspirations, the EU is in danger of becoming an inadvertent factory of insecurity and envy. This is similar to a phenomenon evident on social media: Facebook users often compare themselves to the idealised image of their most successful friends rather than reflecting on how their own lives are improving. In the same way, many European citizens now compare themselves to the richest and happiest people in other European countries rather than their parents, their neighbours, or even their younger selves.

Secondly, anxiety about the future has a geopolitical dimension. Europeans are concerned about the volatile international environment, particularly uncertainty around the EU’s relationships with the United States, China, and Russia. Few Europeans believe that their economic interests vis-à-vis China are well-protected. When asked about their future, many respondents seemed strongly preoccupied with safety.

Finally, Europeans’ concern about the future stems from an awareness of the threat nationalism poses to the EU. For example, respondents in Austria, Germany, and Greece – all countries with a relatively high per capita intake of migrants since 2015 – generally perceived nationalism as a bigger threat than immigration.

The way Europeans feel about their lives also affects the long-term issues they care about. In all EU countries aside from France, Greece, Poland, and Romania, respondents saw a feeling of safety as the most important factor in ensuring a good future for them and their families.

In most countries, respondents also tended to see access to clean air as a major future concern – and generally viewed it as more important than feeling valued or having their values respected. Finally, respondents – particularly those in the Czech Republic, Greece, Poland, Romania, and Sweden – stated that they valued fairness a great deal.

A grammar of conflict, a logic of peace

The battle for Europe centres on ownership of the narrative on the future – whose story will prevail, the role the political system will play in this story, and the terms of engagement. In this context, the upcoming European Parliament election will be decisive.

Pro-European parties know well how to mobilise peaceniks. Yet, in this election, they must connect with other groups of voters by showing an understanding of, and respect for, the feelings of those they are trying to reach. The parties need to engage with reluctant warriors, and to convince this group that they are not too naïve and weak to meet the challenges of a dangerous world. The parties need to display urgency, bellicosity, solidarity, and belief, while putting forward progressive messages framed in emotional terms. In other words, if they want to advance the logic of peace, they will need to show that they can use the grammar of war.

Connecting is more important than convincing.

Myth-busting and the deployment of facts will not change people’s beliefs. As cartoonist Scott Adams has argued about current divisions in the US (over, for example, whether the Mueller Report vindicates President Donald Trump), there are currently “two movies playing on one screen”. Reluctant warriors will not be convinced about the value of a vote – or, indeed, of voting for a pro-European party – by new evidence or by reasoned argument based on data. What matters is emotional resonance, a quality that is prized in times of conflict. If pro-European parties try to dismiss the logic of warfare, they risk alienating voters that believe in progressive policy but are disillusioned with current leaders and parties that have not understood the conflict dynamics in the EU.

For inspiration in reaching these voters, pro-Europeans need to look beyond the party system. For instance, both environmental movement Extinction Rebellion and the gilets jaunes (yellow vests) in France have used the logic of conflict to communicate a different vision of the future. In the focus groups ECFR organised in France, Germany, Italy, and Poland, there was palpable excitement about images of the gilets jaunes and Extinction Rebellion. Participants in the groups were respectful of the movements and those that engaged with them.

In contrast, the energy in the room dissipated when participants were confronted with images of discussions in the European Parliament, which they saw as time-consuming, tedious, and unproductive. Extinction Rebellion uses direct action to gain attention, before setting out its manifesto and expressing a willingness to engage with politicians. In this way, the movement tries to connect the traditional political system with the anti-system world.

In the current political environment, storytelling is crucial to persuading voters to engage in the democratic process, and to creating a safer, fairer, and more comfortable future. And effective storytelling always requires emotional engagement.

French President Emmanuel Macron is one of only a few leaders at the centre of European politics who have made this case for a reformed, more determined Europe that protects. But, in this delicate moment, his reform project has met with a lukewarm response from his counterparts in other capitals, not least Berlin – who have proven unable to think beyond the confines of traditional party politics. Green parties across the EU have also tried to make the case for internationalism. Yet, although – as ECFR’s survey shows – voters are increasingly interested in environmental issues, these parties have failed to create enough drama and urgency around their agenda to significantly boost their support. They may be trapped in the peacetime dynamics of argument and a need for data as proof. In contrast, environmental activist Greta Thunberg and her followers start from the assumption that the argument is over and the facts are there for all to see; for them, the real issue is unity, commitment, action, and mobilisation.

How does it feel?

Pro-European parties now need an inclusive, compelling story about the future – one based on a more emotional understanding of voters. Only this can reconnect disenchanted Europeans with the political system and an appealing vision of a future. The story needs to move beyond appeals to policies and demands to do what is right. It must actively acknowledge voters’ sense of stress, speak to their fears, and then capitalise on their resilient optimism. The European Parliament election campaign provides too short a period for the story to fully unfold, but there may be no better time to start telling it.

Methodology

The second round of polls was conducted by YouGov in March 2019, with 1,000 samples for each of 14 countries, except Sweden where it was 2,000, and Denmark 1,400, and Greece and Slovakia 500.

The full list of 14 countries includes: Austria, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, and Sweden.

See coverage in:

The Guardian: “Majority of Europeans ‘expect end of EU within 20 years’”

The Guardian: “Majority of Europeans ‘expect end of EU within 20 years’” La Stampa: “Italia e Francia dominate dalla paura: “In dieci anni l’Unione può dissolversi””

La Stampa: “Italia e Francia dominate dalla paura: “In dieci anni l’Unione può dissolversi”” Süddeutsche Zeitung: “Einfach machen”

Süddeutsche Zeitung: “Einfach machen” Le Monde: “Deux électeurs sur trois redoutent le démantèlement de l’Union européenne”

Le Monde: “Deux électeurs sur trois redoutent le démantèlement de l’Union européenne” Gazeta Wyborcza: “Badani w 14 krajach UE: Unia chyli się ku upadkowi, a pomiędzy krajami Wspólnoty wybuchnie wojna”

Gazeta Wyborcza: “Badani w 14 krajach UE: Unia chyli się ku upadkowi, a pomiędzy krajami Wspólnoty wybuchnie wojna”

Acknowledgements

The authors of this report are hugely grateful to colleagues across the ECFR network for all their input into the research and production of this report. In particular, they would like to thank Pawel Zerka, Philipp Dreyer, Vessela Tcherneva, Susanne Baumann, Swantje Green, Ana Ramic, Sunder Katwala, Simon Hix, Jose Ignacio Torreblanca, and Jeremy Shapiro for their advice, insights, and hard work on framing the research and analysis; William Davies for his insights from both his published work and in conversation about this project; Katharina Botel-Azzinarro for her work on the graphics; and Chris Raggett for his amazing editing. We would also like to thank the team at YouGov for their patient collaboration with us in developing and analysing the data set. Despite all these many and varied forms of input, any errors in the report remain the authors’ own.

About the authors

Susi Dennison is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations and the director of ECFR’s European Power programme. In this role, she explores issues relating to the strategy, cohesion, and politics of achieving a collective EU foreign and security policy. She led ECFR’s European Foreign Policy Scorecard project for five years, and since the beginning of this year has led the research for ECFR’s Unlock project.

Mark Leonard is co-founder and director of ECFR. He writes a syndicated column on global affairs for Project Syndicate and his essays have appeared in numerous other publications. Leonard is the author of Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century and What Does China Think?, and the editor of Connectivity Wars. He presents ECFR’s weekly World in 30 Minutes podcast and is a former chair of the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Geo-economics.

Adam Lury is a founding member of ECFR and CEO of Menemsha Ltd – an organisation that specialises in working with CEOs on corporate purpose. He has held several non-executive directorships in both the private sector and non-governmental organisations. In 1987 he co-founded UK-based advertising agency Howell Henry Chaldecott Lury, which was Campaign’s ‘Agency of the Decade’ in 1999. He is the co-author of three novels – two of which feature a data detective – and a short novella for the Foreign Policy Centre.

The Unlock project

The ‘Unlock Europe’s Majority’ project aims to push back against the rise of anti-Europeanism that threatens to weaken Europe and its influence in the world. Drawing on polling and focus group data in 14 European Union member states (with representative sample sizes), ECFR’s analysis will unlock the shifting coalitions in Europe that favour a more internationally engaged European Union. The project will show how different parties and movements can – rather than competing in the nationalist or populist debate – give the pro-European, internationally engaged majority in Europe a new voice. ECFR will use this research to engage with pro-European parties, civil society allies, and media outlets on how to frame nationally relevant issues in a way that will reach across constituencies – and that will reach the ears of voters who oppose an inward-looking, nationalist, and illiberal version of Europe

Footnotes

[1] The authors are grateful to Will Davies’s Nervous States for the ideas this section is built on.

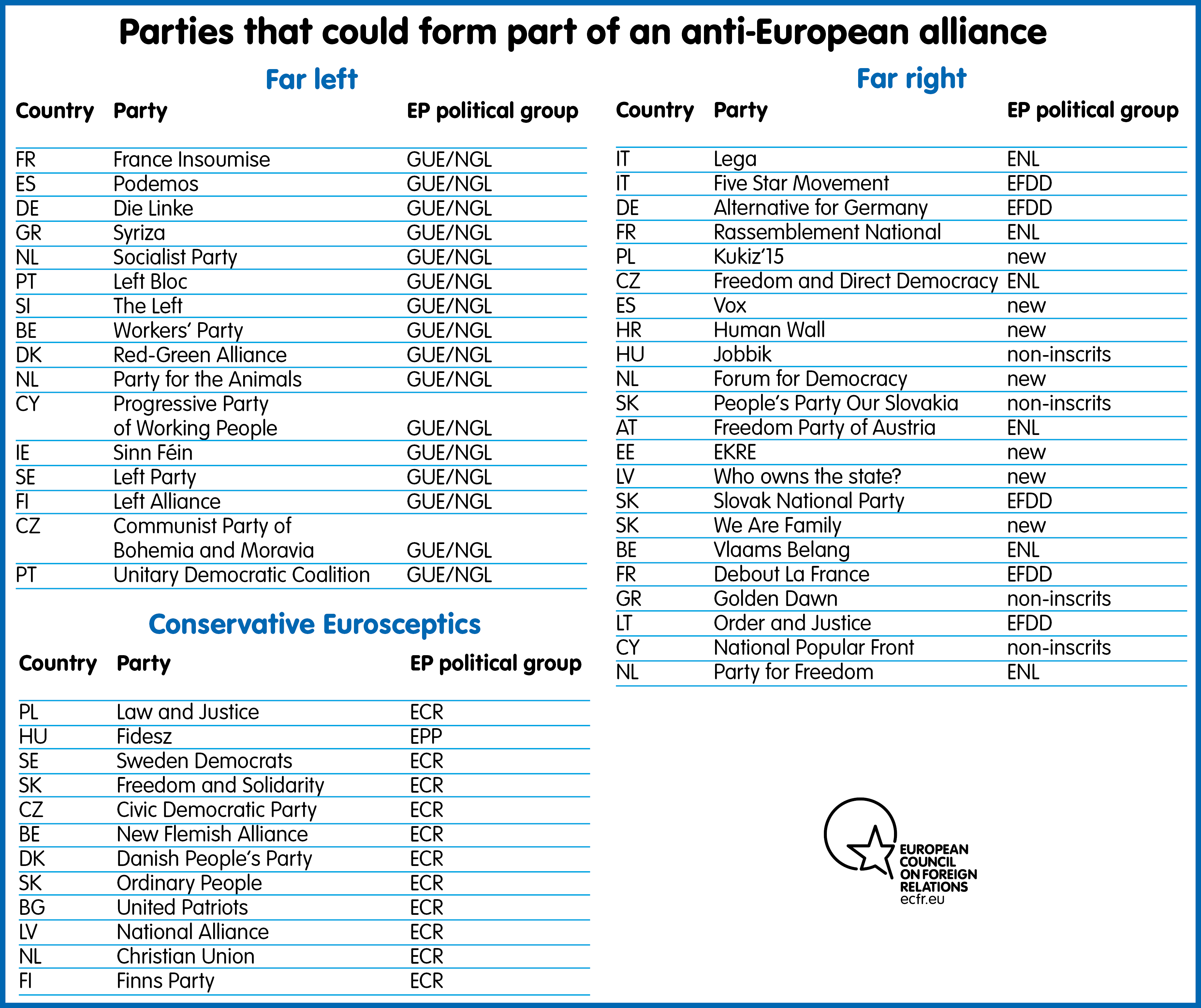

[2] European parties in the 14 member states in this research that could potentially form part of an anti-European alliance are listed in an annex to this report. The authors treat all other parties as pro-European.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.