War and pieces: Political divides in southern Yemen

Summary

- Since the 2010s, a wide range of separatist movements have represented the main political demands in southern Yemen.

- These groups are motivated by their geographical and historical origins, backed by various foreign powers, and divided by their demands for independence or autonomy.

- The Southern Transitional Council, the most prominent separatist group, claims to represent the south as a whole but it has limited control over parts of western governorates.

- The 2019 clash between the council and the internationally recognised government poses the most serious threat to the anti-Houthi coalition since the start of the Yemen conflict.

- The implementation of the Riyadh Agreement is far behind schedule and it is unclear whether Saudi Arabia will be able to enforce the deal, given the UAE’s withdrawal from Yemen.

- The European Union should continue to support development and state-building in Yemen, increase its efforts to mediate between Yemenis, and develop institutional and democratic platforms on which southerners can achieve self-determination.

Introduction

On 5 November 2019, the internationally recognised government of Yemen (IRG) signed the Riyadh Agreement with the Southern Transitional Council (STC) separatist group, aiming to settle an armed conflict between the sides that had reignited three months earlier, when the STC expelled the IRG from its temporary capital of Aden. This outbreak of violence forced the international community to focus on the southern question, after it had side-lined the issue to deal with the crisis resulting from the Houthi takeover of Sana’a and most of the country’s highlands in 2014. Foreign powers involved in the broader war in Yemen have paid limited attention to southern separatism, partly because they all want the country to remain unified. Yet their approach is unsustainable: the war puts the country at risk of disintegration. Only by addressing the diverse, complex challenges that have arisen in southern Yemen can the European Union succeed in its efforts to create neutral, constructive avenues for mediation and development across the country.

This paper focuses on the origins, development, and prospects of political challenges in southern Yemen. It begins with an analysis of historical divisions in the south, outlining key issues within specific governorates – including the political fragmentation that has occurred since 2015, when the war in Yemen first gained an international dimension. The paper concludes by examining the significance of the Riyadh Agreement, as well as the implications for the south of current attempts to end the war. It argues that EU policymakers need to address the diverse, complex problems facing southern Yemen if they are to create a sustainable solution to the conflict – and makes several recommendations for how they could achieve this. The EU should continue to support development and state-building in Yemen, and should increase its efforts to mediate between southerners, as well as between southerners and northerners. This would promote cooperation and coexistence, encouraging the development of institutional and democratic platforms upon which southerners can achieve self-determination.

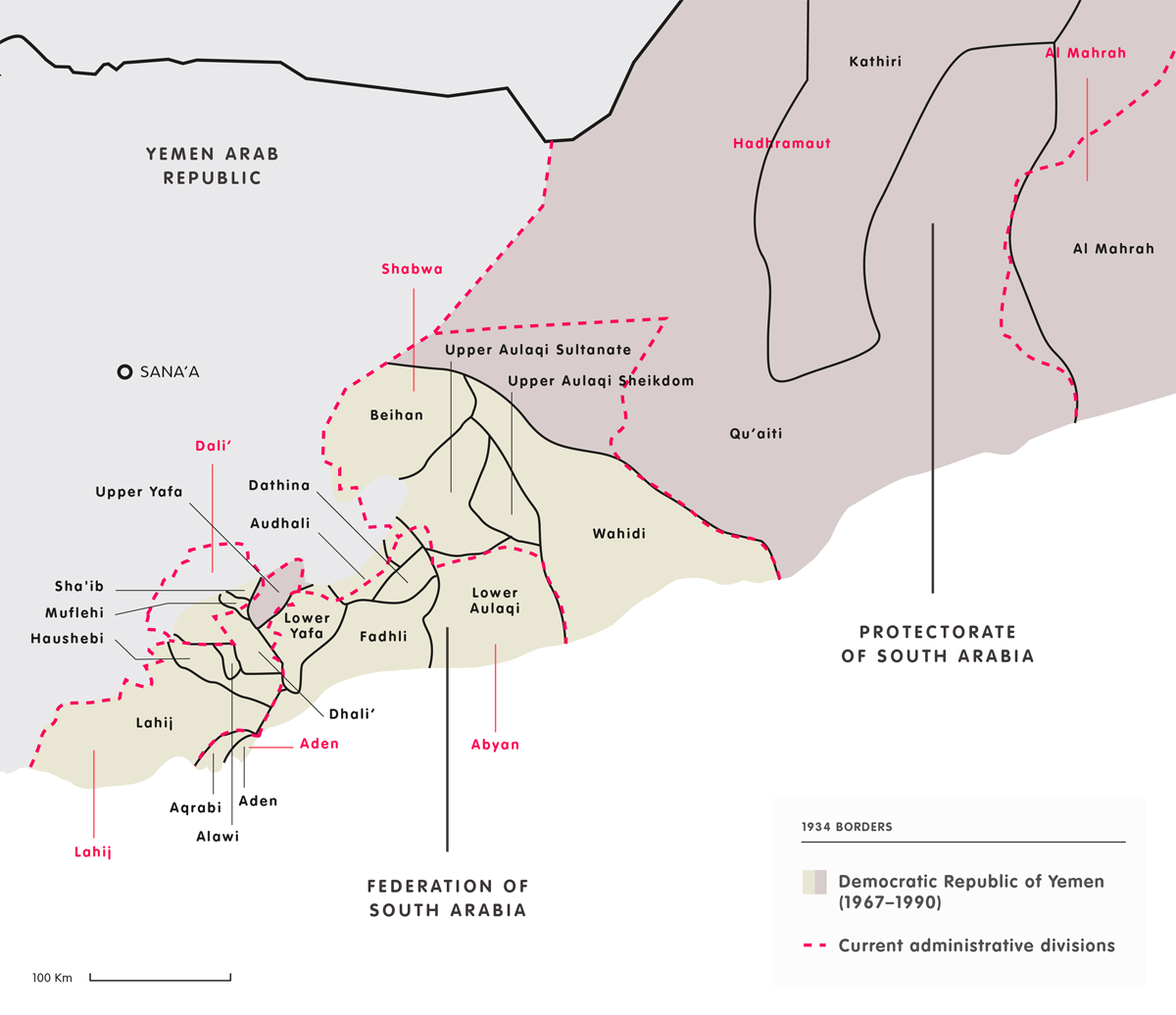

Two decades of the Republic of Yemen

The Republic of Yemen was formed in 1990 by the merger of the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR), centred on the capital of Sana’a, and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) – which, with its capital in Aden, was the successor to the British Colony of Aden and the Protectorates. President Ali Abdullah Saleh rose to power in the YAR in 1978. He became president of the Republic of Yemen at its establishment, holding this position until the Arab uprisings forced him to resign in 2012. He was replaced by his vice-president, Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi, in a single-candidate election under the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Agreement. The process received support from not only GCC states but also other major world powers that have an interest in Yemen. Southern separatist movements do not perceive Hadi as an ally, because he is a southerner who migrated to Sana’a following the defeat of his faction in an intra-PDRY struggle in 1986.

The two-year transition process under the GCC Agreement also included a National Dialogue Conference designed to bring together all the country’s political forces and create a consensus solution to the country’s myriad political, economic, and social problems. While a majority of its members were southerners, the conference was unable to bring some separatist factions to the table, as they refused to be part of any discussion that treated the south as part of Yemen and demanded that it be recognised as an independent entity based on the pre-1990 border. The southern question was one of the many issues that the transition and the National Dialogue Conference failed to resolve, largely due to the obstinacy of, and divisions within, southern movements.

The international community – including EU countries and the members of the GCC that form the Saudi-led military coalition intervening in Yemen – officially recognises the Republic of Yemen as representative of all Yemen, including the south. It has supported the IRG since 2015, when Hadi relocated its capital to Aden.

Origins of southern movements

Before independence

The territory of interest to southern separatist movements remained under effective British control until independence. The area experienced active political opposition to Britain’s colonial project from the 1950s onwards. It was home to a lively trade union movement with links to its UK counterparts and, to a lesser extent, the British Labour Party. In the 1960s, following the overthrow of the imamate in Sana’a and the establishment of the YAR, the anti-colonial movement intensified in the south. It was divided into two rival groups – the first of which was the Nasserite People’s Socialist Party, a group led by Abdullah al-Asnag that gradually morphed into the Egyptian-backed Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen (FLOSY). The second movement was the National Liberation Front, which originated within the Movement of Arab Nationalists – an organisation that had a tense, complex relationship with Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser.

These two movements fought against Britain while remaining rivals. In 1967 the National Liberation Front emerged victorious from serious fighting with the FLOSY. The National Liberation Front’s takeover of most of the Protectorates’ territory persuaded Britain to negotiate independence with it in summer 1967, before handing control of the country to it the following November. The PDRY would go on to become the only Arab state that openly aligned with the Soviet bloc throughout the remaining two decades of the cold war.

The People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen

The PDRY regime, which implemented welfare-focused social policies and attempted to create a socialist-orientated mixed economy with a strong role for the public and cooperative sectors, was characterised by destructive factional infighting. (It is debatable to what extent these conflicts within the Yemeni Socialist Party resulted from ideological differences or more traditional regional or tribal rivalries.)

During the 23 years of the PDRY’s existence, the regime implemented anti-tribal policies and rejected regional allegiances by, for example, initially numbering rather than naming governorates. When the leadership eventually chose names for the governorates, it selected ones that referred to geographical or ancient historical entities rather than contemporary social or tribal allegiances. The regime also encouraged Yemenis to use their fathers’ and grandfathers’ first names rather than family or tribal names. At the political level, it also tried to ensure that people from all parts of the country, as well as all social groups, were represented in senior positions, aiming to include the sada (direct descendants of the Prophet Muhammad), tribal groups, and those of low status. These initiatives, however, failed to prevent the emergence of bitter internal conflicts that led to the unconstitutional removal of top leaders in 1969, 1978, and (most prominently) 1986.

The 1986 conflict was the longest and bloodiest of the three. Initially a power struggle within the political bureau of the Yemeni Socialist Party, the fighting spilled into the streets and developed into a regional conflict. Individuals were detained or killed on the assumption that the location of their birth determined their allegiance to a particular side. As such, many observers have described the 1986 conflict as a return to tribalism. There is little doubt that an official policy of promoting national rather than regional allegiances cannot change a centuries-old culture in just two decades. This is particularly true of regional divisions and rivalries as intense as those in the west of the PDRY.

These developments are highly relevant to the situation in Yemen in early 2020, as the signatories to the Riyadh Agreement are largely divided into the same two factions that fought each other in the 1986 conflict. Today, the STC is the successor to the group that went on to rule the PDRY for the remaining four years of its existence (but whose main leaders were killed in the process), mostly originating from the governorates of Lahij and Dhali’. On the other side, Hadi and many of his ministers have roots in the defeated faction whose members originated mainly from Abyan and Shabwa governorates – and who took refuge in Sana’a after their defeat in 1986.

Unification and the rise of southern grievances

Of all the official political slogans in the PDRY, “Yemeni unity” was the most popular. The socialist regime did not attempt to create a southern Yemeni national identity but supported the popular concept of the Yemeni nation, as did the leadership in the YAR. When unification came in 1990, it was welcomed throughout the country. Yemenis everywhere looked forward to free movement and a prosperous economy, hoping that the positive elements of the political, social, and economic policies of the two previous regimes would prevail across the unified country.

Southerners, however, were soon bitterly disappointed. The official three-year transition period was marked by a rapid decline in living standards in the south, with subsidies on basic food commodities coming to an end and prices rising as, in practice, the riyal immediately replaced the dinar. The city of Aden was neglected by officials and others who moved to Sana’a, to be closer to the centre of power. Poor, remote rural areas suffered as the government reversed its agrarian reforms: more than 20,000 smallholders lost their usufruct rights and were reduced to working as sharecroppers or casual labourers. Meanwhile, the pre-independence elite regained their privileges, as did other close associates of the Saleh regime. Among the beneficiaries of the new order were families who had become wealthy after migrating to Saudi Arabia and were willing to invest in the Yemeni communities from which they originated.

The deterioration of relations between the Saleh regime and the Yemeni Socialist Party – which shared power with him during the transition period – was reflected in the assassination or attempted assassination of more than 150 of the party’s leaders, as well as the increasing recriminations between the two leaderships. The 1993 parliamentary election marginalised the Yemeni Socialist Party, which was replaced in the new government by the Islamist Islah Party. Relations between the southern and northern leaderships deteriorated further, leading to the 1994 civil war between Saleh supporters of unification and factions of the Yemeni Socialist Party that called for the return of the pre-1990 border. Saleh won this war decisively thanks to the support of exiles from previous conflicts within the south (including former members of the military, such as Hadi). His victory led to the ransacking of Aden and other towns by Islamist fundamentalists, including members of former southern regimes, fighters who had returned from the jihad in Afghanistan, and northerners who regarded the south as a hotbed of atheism and communism.

In the years that followed, southerners saw their economic situation deteriorate and their social lives increasingly fall under the influence of conservative religious norms, which particularly affected women. With political life in the south dominated by Islah and Saleh’s party, the General People’s Congress, there was a growing gap between the poor majority and a small minority of wealthy individuals – most of them Saleh’s associates (from both the north and the south). In this way, many people become convinced that the regime was discriminating against the south.

The development of the southern separatist movement, 2007-2017

In 2006 Yemeni military and security personnel who had been forced into retirement after 1994 started a movement that initially demanded payment of their pensions, seeking the means to achieve a reasonable living standard. The Saleh regime’s brutal suppression of the movement caused it to expand beyond Dhali’ and Lahij, taking hold in the city of Aden and areas such as the eastern governorate of Hadhramaut. Following the outbreak of the Arab uprisings in 2011, thousands of Yemeni supporters of the movements began calling for political, social, and economic reforms to improve people’s living conditions and reduce inequality. Southerners joined forces with other Yemenis for a short period but, after the GCC Agreement was signed, the separatists grew stronger and other elements of the reform movement weakened.

With the collapse of the GCC Agreement’s transition in 2014 and the Houthi takeover of Sana’a, Hadi’s IRG attempted to re-establish itself in Aden. The separatists opposed the IRG presence in the city, partly because there were many northerners in his government. This reflected an increasingly violent strain of anti-northern prejudice in the south, which resulted in the ill-treatment of many people of northern origin and their expulsion from Aden and neighbouring governorates.

Since the 2010s, the main political demands throughout the south have been expressed by a wide range of separatist movements whose only ideological difference concerns whether they demand complete independence or autonomy. These movements have undergone significant fragmentation. Some are led by former rival leaders of the PDRY or their sons – as is the case of Ali Salem Al Beedh and Hassan Ba’um, both of whom are from Hadhramaut and draw most of their support from that governorate but claim to represent the entire south. The movements, a mixture of allies and rivals, are organised under the Supreme Council for the Peaceful Struggle to Liberate and Restore the South (which has taken on slightly different names in the past decade). Some of the movements, such as those led by the al-Jifri family, originated in the colonial period, while others have emerged in recent years, contributing to the political fragmentation that has characterised Yemen since 2015. Ali Nasser Mohammed, former president of the PDRY and one of many southerners who fled to the north after 1986, has also been active throughout the period, holding meetings in various locations – although he has supported the establishment of a federal system rather than secession.

European countries and other foreign powers have, unsuccessfully, attempted to encourage various separatist movements to reorganise into a manageable number of organisations with clear aims. This has involved a series of meetings in Abu Dhabi, Amman, Beirut, Cairo, and various European capitals, attended by varying combinations of separatist leaders and their followers (the latest of these took place in Brussels in December 2019). At best, these leaders have committed to attend follow-up meetings. But they have been consistently unable to agree on even short-term programmes or objectives. While all of them call for either the autonomy of the south within a unified Yemen or the outright return to an independent southern state along the pre-1990 border, any high-profile announcement of a formal grouping of separatist organisations has promptly led to denials by some of the signatories. This disarray results from their lack of fundamental policies: none of them has advanced any social, economic, or other programme beyond the call for separation. It also results from their narrow-minded, self-serving objectives – which disregard the needs of the wider population, including their supporters, all of whom are suffering from instability and deep economic problems.

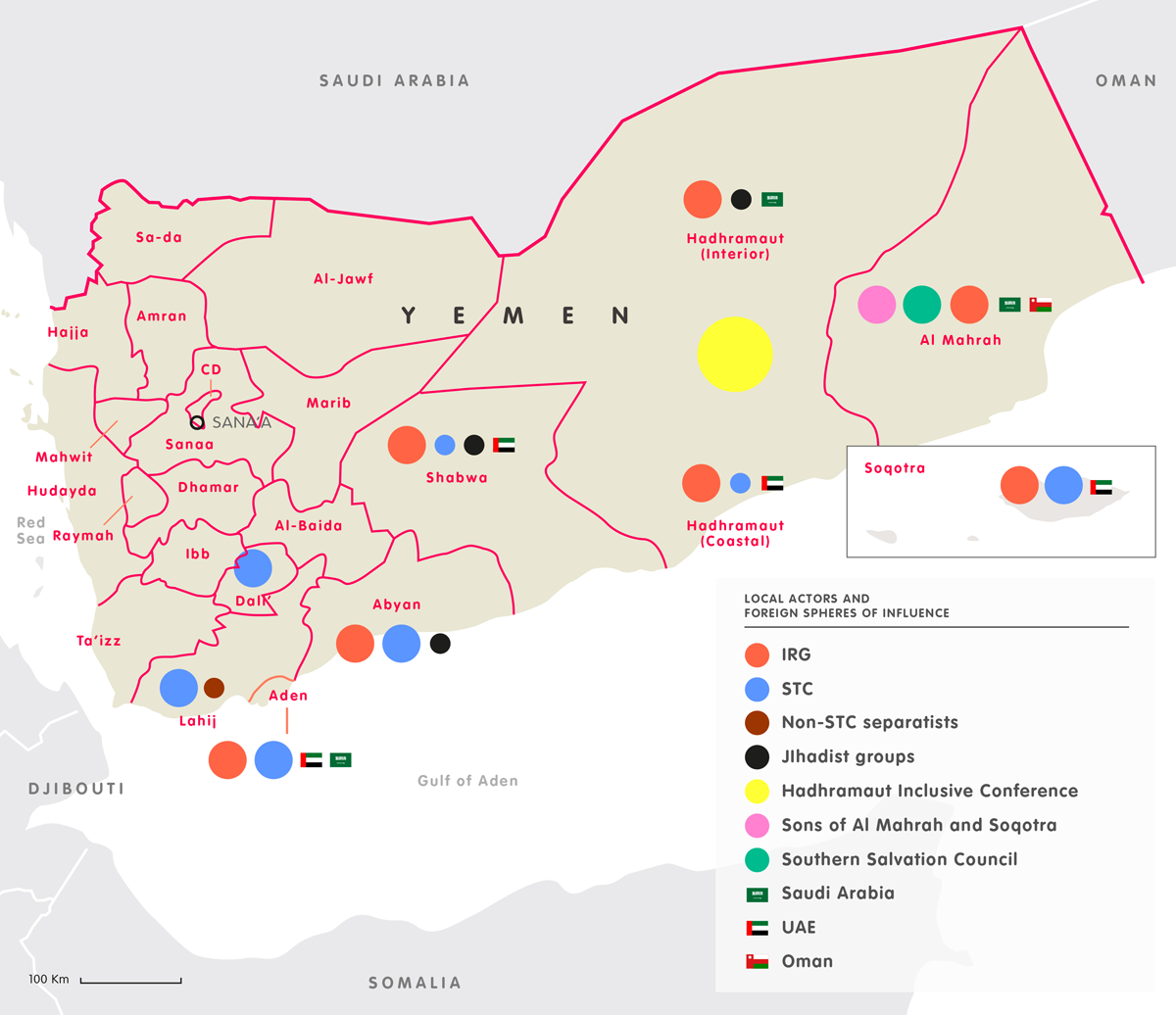

However, since 2017, one faction has come to dominate the national and international discourse on southern separatism: the STC, an organisation established in April that year by former governor of Aden Aydaroos al-Zubaydi, and his close allies Hani bin Breik, a former minister without portfolio in Hadi’s government, and Shalal Shaye. Hadi had been under pressure from the Saudi-led coalition – particularly the United Arab Emirates, which represented it in Aden – to give Zubaydi and his allies government positions (despite their support for separatism and their opposition to Hadi’s faction in the 1986 conflict). Hadi did so, but rising tensions within the government eventually led him to fire Zubaydi and bin Breik, prompting them to form the STC.

Geopolitical alignments

It is misleading to delineate rival southern groups strictly by governorate. Each of Yemen’s governorates, which were defined by the PDRY regime and only slightly modified after unification, contains numerous political entities that formed prior to independence, particularly in what are now Abyan, Dhali’, Lahij, and Shabwa. Political rivalries from the pre-independence and PDRY days will continue to be a source of instability for years to come. And other rivalries have emerged in the three decades since unification. Moreover, support for unification is common among many in the south – including not only those from families with mixed backgrounds but also Yemenis who work, travel, and maintain relationships across the country.

Yet, as far as much of the outside world is concerned, southern separatist movements are now synonymous with the STC. This oversimplification of the situation could lead to dangerous policy choices. The STC has achieved its international prominence thanks to the UAE’s strategy in the Yemeni crisis. One of the two states most responsible for internationalising the civil war in Yemen, the UAE has concentrated its interventions in the country’s south. After deploying troops to Aden in July 2015 and playing a major role in expelling Houthi-Saleh forces from the city, the UAE led coalition operations in southern governorates. Prior to the Riyadh Agreement, Saudi Arabia only participated in these activities as a mediator between UAE-backed forces and the IRG.

The UAE established several organisations designed to provide security in southern governorates: “Security Belts” in Abyan, Aden, Dhali’, Lahij, and Soqotra; and “Elite Forces” in Hadhramaut and Shabwa. These groups are led by Salafists (fundamentalist Sunnis), have been trained and deployed with Emirati assistance, and are paid directly by the UAE. Although they formally work for the IRG, they do not answer to Yemen’s Ministry of Defence or Ministry of the Interior. In addition to implementing the UAE’s strategy to undermine Islah – a party it perceives as linked to the Muslim Brotherhood – in Aden and beyond, these forces are associated with the STC in western governorates. Thus, the STC can enforce its will through the Security Belts.

The STC has established offices in some western capitals and gained access to the services of public relations companies, while its commanders travel to meet world leaders and promote its cause. This has enabled it to achieve international stature at the expense of the numerous other southern separatist organisations, which it has marginalised. In the past two years, the rivalry between the STC and the IRG has intensified, culminating in the IRG’s expulsion from Aden in August 2019. The event coincided with the UAE’s formal withdrawal from Aden, which left Saudi Arabia to reconcile the STC with the IRG.

As discussed above, due to their fragmentation, southern separatist groups have so far been unable to develop common positions or create lasting alliances, thus preventing the international community from finding interlocutors among them. If international policymakers are to change this, they need to understand the various strands of separatism that run through the south in relation to Yemen’s pre-1990 borders.

Aden

As the former capital of the PDRY, Aden was officially named the economic capital of Yemen when the country was unified – although this was largely a formality as, prior to 2015, the government only made brief visits to the city in winter, when the weather there is agreeable (and is cold in Sana’a). In the fighting of 2015, local resistance forces comprised fighters with a wide range of ideologies and alliances, some of whom received considerable support from the UAE.

Given Aden’s position as the interim capital, all factions believe it is essential to maintain a public presence there. This is particularly relevant for the IRG: without its Aden base, it is no more than a government in exile. Hence Saudi Arabia’s efforts to forge what has become the Riyadh Agreement. Since 2015, Aden has struggled to become the true capital of the IRG. This is because Hadi and most of his ministers use Riyadh as their main base and, as such, are rarely in Aden, where most remaining embassies to Yemen are located. International organisations have their main Yemeni offices in Sana’a and sometimes operate from Amman and Djibouti, maintaining only a minimal presence in Aden.

Moreover, the relationship between Hadi’s government and various southern separatist groups in Aden has been tense from the beginning. Few members of local resistance forces recognise Hadi’s legitimacy as president, as most are aligned with the separatists. The uneasy alliance between the sides lasted until 2017, when Hadi dismissed Zubaydi as governor of Aden. An indicator of the balance of power in the city is the position of Shaye, who retained his post after Zubaydi’s dismissal, nominally answering to the IRG until 12 August 2019 – when his allies in the STC expelled the Hadi government from Aden. He was eventually dismissed in mid-August 2019 after the STC had taken over Aden, but in early 2020 appears to remain actively involved.

In addition to being the main site of conflict between the IRG and the STC, Aden also suffers from considerable insecurity caused by struggles between various forces. In particular, the Security Belt and other STC-linked Salafist forces have – in line with the wishes of their Emirati sponsors – frequently launched attacks on individuals associated with rival political groups, mainly Islah. The UAE and the STC publicly describe these attacks as “anti-jihadist”, thereby conflating Islah followers with members of al-Qaeda or the Islamic State group (ISIS). With the help of these local forces, the UAE has allegedly maintained secret prisons throughout the region in which it has tortured detainees and held them without trial for lengthy periods. Moreover, the UAE has allegedly hired foreign mercenary groups to assassinate Islah members and other perceived enemies.

The confusing political situation in Aden reflects the city’s complex history, particularly its role as a focal point for migration in the last century. In addition to being a destination for rural Yemenis seeking job opportunities, Aden has also been the main port from which Yemenis migrated. People came to Aden from the Protectorates, the imamate, and the YAR, creating the basis for a very mixed society – one that it is far more liberal than other parts of Yemen – as well as an intellectual and political centre. These factors make the xenophobic attacks against northerners in Aden all the more jarring.

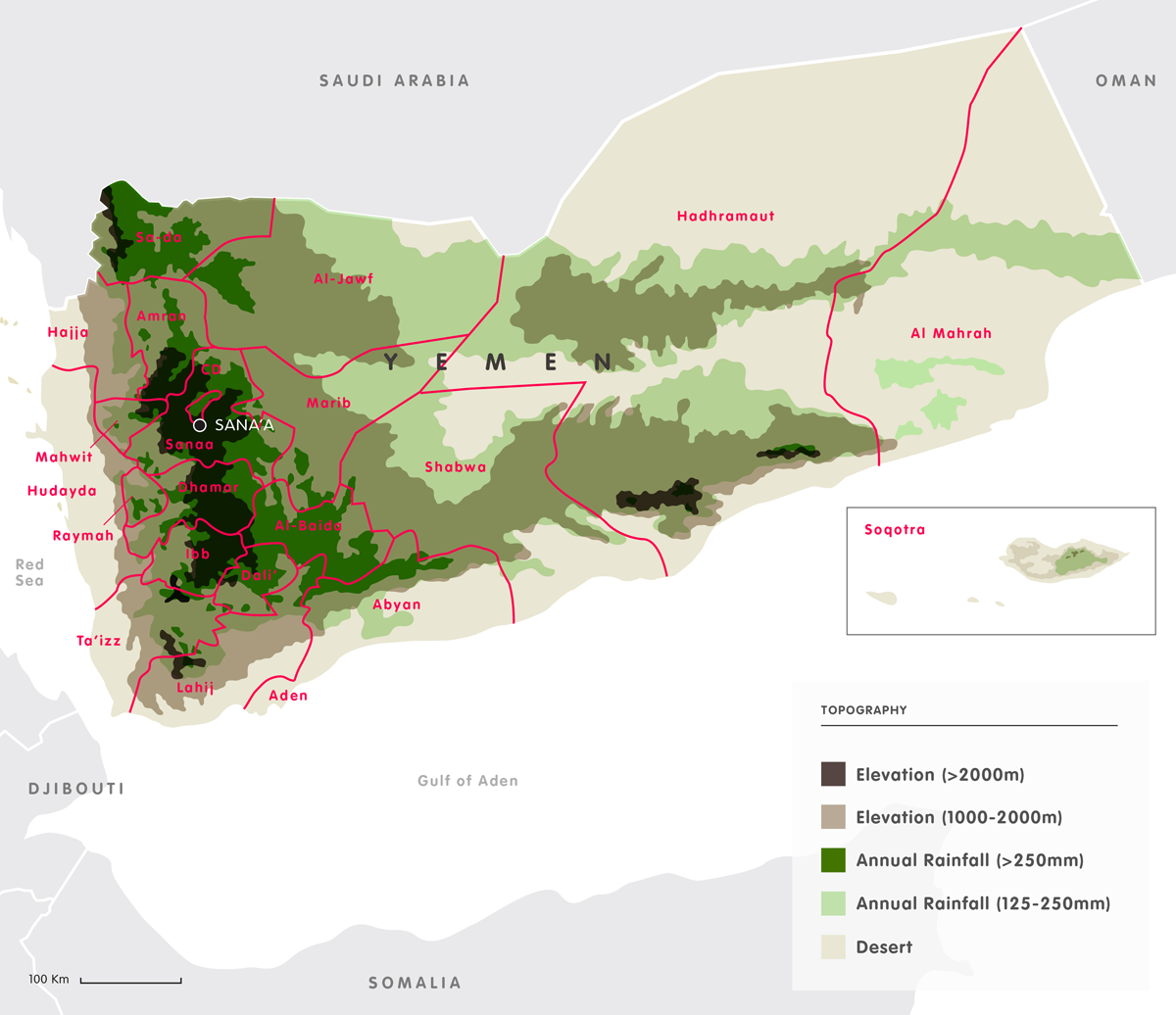

Shabwa and Abyan

During the PDRY’s internal conflicts, groupings in Shabwa and Abyan often fought alongside against those in Lahij, but also competed with one another. For example, the 1978 conflict pitted factions from lowland, coastal Abyan against those of the midland jol (plateau). Shabwa’s Marib-Balhaf gas pipeline and small oil fields aside, both governorates are economically dependent on agriculture and artisanal fisheries. The governorates are mostly inhabited by tribal people, and include significant numbers of farmers from low-status groups.

After Aden, Shabwa and Abyan are the main focus of conflict between the STC and the government – one of the many indicators that the STC is dominated by leaders, and receives most of its support, from Lahij and Dhali’. Shabwa is strategically important because it is adjacent to Al Bayda and Marib, and is a key access point for eastern governorates such as Hadhramaut and Al Mahrah. The STC and the IRG blame each other for attempting to take control of Shabwa’s hydrocarbons. Shabwa’s Elite Force, a group trained by the UAE with the ostensible goal of protecting the governorate from jihadist groups, remained active until September 2019, when the IRG drove its 6,000 fighters out of most of the governorate. By early 2020, the IRG controlled most, if not all, of Shabwa – partly with the help of the most influential figures there, including Mohamed Saleh bin ‘Adyu, governor of Shabwa, and General Ali bin Rashid al-Harthi, whom the US accuses of being a member of al-Qaeda. In 2017 Shabwa experienced more US raids against al-Qaeda than any other governorate.

Abyan was home to one of the first strongholds al-Qaeda established in Yemen, as well as of some of the first jihadist organisations established in Yemen, such as the Aden-Abyan Islamic Army. In 2012 extremist militants took over two districts in Abyan (Ja’ar and Zinjibar), prompting the government to launch a military campaign to retake the areas. In 2015 some of coastal Abyan temporarily came under jihadist influence once again – but most of the governorate is now under STC control. Abd al-Latif al-Sayed, leader of the Abyan Security Belt and allegedly a former member of al-Qaeda, has survived four assassination attempts since he defected to the STC in 2017. His men control much of Ja’ar, Zinjibar, and parts of Ahwar. The fact that Sayed received medical treatment paid for by the UAE after one assassination attempt indicates his value to the Saudi-led coalition – although that value has fallen since then, due to a conflict in Abyan between his forces and those led by the UAE. Minister of Interior Ahmed al-Maisari asked Sayed to join the IRG after the last round of fighting between the IRG and the STC in August 2019 but, so far, he has remained loyal to his Gulf patrons.

In contrast to Shabwa, Abyan has only a small Islah presence. Abu Bakr Hussein Salem – who was appointed governor of Abyan in 2017 – is one of the few Islah-backed IRG figures who has retained a degree of influence there since the STC’s partial takeover of the governorate.

Lahij and Dhali’

Dhali’ governorate was established in 1998, when the government merged a small section of Lahij with parts of Ibb, Taiz, and Al Bayda. Dhali’ and Lahij formerly included numerous micro-states. They are economically dependent on small-scale agriculture, artisanal fisheries, and emigration (through remittances and investment). Their inhabitants, who are mainly tribal, formed the bulk of the military and security forces of the PDRY. The “Hirak”, the umbrella name for southern separatist groups, was established in Dhali’ in 2006 as the Association of Retired Military, Security, and Civilian Personnel. The association was led by General Nasser al-Nobah, Abdu al-Maatari, and Salah al-Shanfari until 2017, when Nobah began to lead it from Aden. He maintained this role until the STC captured the city. Nobah sided with Hadi during the STC takeover, while Maatari and Shanfari both started their own separatist movements in Dhali’ – where they continue to compete with the group (with little success).

The western part of Lahij is home to Sheikh Hamdi Shukry al-Subaihy, leader of the Subaiha Resistance against the Houthis and of his own separatist grouping, which is made up of Salafist fighters. He is one of the commanders of the Giants Brigade (a force the UAE created and has extensively supported). Although a separatist, he opposes the STC and is popular among Salafists. His influence extends across Al Subaiha.

Lahij and Dhali’ are now the heartlands of the STC, despite the fact that, on paper at least, its leadership includes individuals from all governorates. This is partly because most of the group’s top commanders come from Dhali’. Yet, even within the two governorates, there are a significant number of fighters who are not part of the STC or its Security Belts. The STC only has full control of the district of Dhali’, central and southern parts of Lahij, and areas of western Abyan near the coast. In 2019 other areas of Dhali’ (which were formerly part of the YAR) became a front in the conflict between the IRG and the Houthis. The STC has no interest in northern Dhali’, but the Houthis, while fighting along the 1967 borders, hope to control all of Yemen.

Hadhramaut

Until the establishment of the PDRY, Hadhramaut was divided between the Kathiri and Qu’ayti sultanates. It is Yemen’s largest governorate and has a diverse population. The sada have played a major economic and political role there – in contrast to other governorates. Tribal groups in Hadhramaut are based mainly on the jol and coastal plains. Although the sada and tribal groups own the governorate’s agricultural land, members of low-status groups do most of the farming there. People in the governorate have long-standing ties to Saudi Arabia and south-east Asia thanks to migration in the last century and the nineteenth century respectively. Some members of the diaspora have become very wealthy and, since unification, invested in the governorate. The governorate’s oil income has in the past not directly benefited Hadhramis, causing some resentment.

Hadhramaut effectively has three different sub-areas. The first of these is the coastal region centring on the capital of Mukalla, which al-Qaeda took over in 2015 and the government recaptured a year later. (While the UAE claimed this as a major victory for its fighters and the Hadhrami Elite Force, the transfer of control was a negotiated event in which al-Qaeda fighters withdrew with the weapons and other loot they had acquired.) The second sub-area is the remote, sparsely populated and inaccessible jol across which jihadist groups are dispersed – and from which they launch occasional attacks.

The third sub-area is the agriculturally wealthy wadi (dry water course), whose capital is Seiyun. Politically, this area is currently aligned with the IRG. There are few separatist forces in the wadi, where Islah is powerful and controls a considerable number of seats in the Yemeni Parliament – largely thanks to support among the low-status agricultural community and the work of its charitable institutions. Some of its one-time supporters have moved on to a more extreme form of Islamism; in recent years, al-Qaeda and ISIS have carried out assassinations in Qatn, Shibam, and Seiyun, usually targeting Yemen Army and coalition figures. Most of these attacks occur in broad daylight, thereby brazenly undermining the authority of the state. In northern Hadhramaut, the IRG’s military forces – including those in Al Abr Military Base, Al Khasha, and Bin Ayfan (which is 40km west of Al Qatn) – are under the command of Vice-President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar. The presence of Islah and jihadists in remote areas has generated some speculation among locals and some terrorism experts that they may cooperate with one another. The most influential Islahi figure in the wadi is Salah Batais, who currently resides in Turkey along with many Islahi figures. Other powerful leaders there include Sheikh Abdullah Saleh al-Kathiri – a member of the former ruling family, and currently an adviser to Hadi – and Sheikh Awadh bin Salem bin Munif al-Jabri, a tribal leader widely respected in both the wadi and the jol. All of them oppose the separatists – although they are likely more committed to Hadhramaut than to the Yemeni state as a whole.

There is a real possibility of increased tension between supporters of Sufi traditions and recently established Salafist movements, Islah, and jihadist groups. Sufis have a particularly important presence in Tarim – home to Dar al-Mustafa, a famous Sufi establishment that attracts many foreign students. This emergence of extremist Salafist groups in the area poses an existential threat to Tarim’s diverse social fabric, rich cultural identity, and prominent families. It has the potential to exacerbate sectarianism in Hadhramaut and further erode religious tolerance throughout the country. Meanwhile, supporters of former sultanates are one of several groups that have made attempts to restore their influence in the governorate, reviving a range of old rivalries.

In coastal areas, where the state had been largely absent since 2011, the Hadhrami Elite Force was welcomed by locals and the governor as providers of security and stability. There were obvious incentives for locals to join this force, as it pays higher salaries than the Yemen Army. Comprising an estimated 11,000 fighters, the force provides the STC with a presence in coastal Hadhramaut. The area is currently under the authority of Governor Faraj Suleiman al-Bahsani, who was appointed in 2017. Although he was recommended by the Saudis, Bahsani has a reputation that has encouraged locals to accept Hadi’s authority. Bahsani and his deputy are primarily loyal to Hadhramaut rather than the IRG or the UAE-backed STC, but he has maintained good diplomatic ties with both Abu Dhabi and Riyadh.

Since 2017, Hadhrami politicians in Yemen and the diaspora have planned a Hadhramaut Inclusive Conference on the future of their governorate, a gesture of unity that has brought influential figures of various backgrounds together. They held a series of preparatory meetings, but the conference itself was prematurely abandoned shortly after the first day’s meeting. Nonetheless, the organisation has grown in strength, actively promoting concerns specific to Hadhramaut under the leadership of Amr bin Habrish, chief sheikh of the militarily important Hamum tribe, and, since 2019, deputy governor. The conference’s secretary-general is Tarek al-Akrabi, who officially represents it in Riyadh. Ahmed Ba Mu’alim, a representative of Beedh’s separatist faction and a close ally of the STC, has joined the conference while maintaining good relationships with other Hadhrami figures. The positive nature of this relationship has generated speculation that the Saudis and the Emiratis may now support the conference’s efforts to maintain peace in the governorate. The organisation remains engaged with public life in Hadhramaut, funding economic and environmental projects such as initiatives for children. It also has offices in both the wadi and on the coast. The conference has gained popular support due to its ability to unite a diverse set of Hadhrami figures within the governorate and beyond.

Although there are differences between the Hadhramaut Inclusive Conference and Bahsani over the future of the governorate, he has also strengthened his ties with Hadhramis by advocating for popular initiatives. For instance, he has called for Hadhramaut to retain 20 percent of its oil revenues, threatening to halt oil production if the government rejects this demand. In this way, both the governor and the conference are attempting to protect Hadhrami interests while maintaining good relations with the leaders of the Saudi-led coalition. In Mukalla, the STC and Bahsani endeavour to remain on good terms with each other, as the city hosts the largest and most active STC presence in the governorate. Notable STC figures in Hadhramaut include General Ahmed bin Breik – a former governor of Hadhramaut and a former member of the General People’s Congress (but no relation to STC Vice-President Hani bin Breik) – and Aqil al-Attas, a member of the STC’s presidential council and a former Islah supporter.

Many influential figures in Hadhramaut seek to remain neutral in the current war as they advocate for local Hadhrami concerns. However, for Hadhramis, neutrality can be dangerous. Hakam Saleh bin Ali Thabet al-Nahdi, a former supporter of the General People’s Congress, may have suffered a personal cost for his neutrality in 2018, when his son was killed. Many Hadhramis feel that the killing was meant to warn neutral leaders to pick a side.

Al Mahrah

Al Mahrah is the second-largest but least populated Yemeni governorate, with barely 120,000 inhabitants. It is also the most remote one, as a result of which its population has historically maintained stronger relationships with Abu Dhabi, Muscat, and Riyadh than with Sana’a. Its population is composed mainly of tribespeople and low-status farming and fishing communities of various origins. Those living in the eastern part of the governorate have close ties to Oman’s Dhofar governorate. Its culture, including its Himyari language, was significantly different from that of the rest of the country, but it has largely become ‘Yemenised’ in the past five decades.

The Saudi-led coalition has accused the Houthis of smuggling weapons through Al Mahrah, which has long served as a hub for trafficking. More broadly, the coalition claims that its intervention in Yemen focuses on preventing Iran from smuggling weapons to the Houthis via Oman – despite the fact that most of this activity centres on direct sea routes to the eastern regions of Yemen and lacks any connection to Oman. This justification for Saudi and Emirati intervention in Al Mahrah’s affairs has drawn the relatively peaceful governorate into the international discourse on Yemen’s war.

The current situation in Al Mahrah is shaped by the same factors that prevail elsewhere in the south, including political and tribal rivalries, as well as foreign powers’ ambitions to capitalise on the fragmentation of the Yemeni state. Since the beginning of the war, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have vied for control of Al Mahrah. In 2018 Saudi Arabia took the lead in the governorate, where it is widely believed to be planning to build an oil pipeline that would free it from dependence on the Strait of Hormuz. The Saudi authorities have taken over the port of Nishtun, whose capacity they are increasing.

The war has also increased the importance of trade routes that cross Yemen’s land borders. Indeed, Shehen border post has developed into a flourishing town and an important link to the country. Customs and other duties collected there generate a significant income for the governorate. However, in August 2018, the Saudi authorities compelled the Mahri administration to raise customs duties by 70 percent and to reject customs documents issued in the Oman Free Trade Zone – measures intended to undermine trade between Oman and the governorate.

Oman views these moves as having brought the war closer to its border. The country wishes to maintain its strong ties to, and its influence in, Al Mahrah due to the close tribal relations between Dhofaris and Mahris. Muscat is also concerned that the Saudi presence there may foment extremism on Oman’s border, particularly after the recent opening of a Salafist school in Sayhut, in the west of the governorate. Competition between states neighbouring Yemen and the funding they provide to their respective supporters has created tension among Mahris. Islah has a presence in Al Mahrah and, as in other governorates, this is strongest among low-status social groups.

Saudi Arabia successfully pressured the Yemeni authorities to appoint its ally, strongman Rajeh Bakrit, as governor of Al Mahrah in November 2017. So far, he has tried to accommodate all powers within the governorate and the wider region. He replaced Mohammed bin Kuddoh, who was closer to both Oman and the UAE (despite the rivalry between these two states). The most popular political entity in the governorate is the General Council of the Sons of Al Mahrah and Soqotra, headed by Sultan Abdullah bin Isa Al Afrar – a member of the family that ruled the Sultanate of Mahrah and Qishn until its abolition in 1967. Since its inception in 2012, the council’s main goal has been to create a federal region within the borders of the former sultanate. The council seeks to restore the sultanate’s linguistic, cultural, social, geographical, and historical independence and homogeneity – as well as to increase its own role in political decision-making in Al Mahrah, after its historical exclusion and political marginalisation.

In October 2019, as tensions between the STC and the IRG grew, the Southern Salvation Council formed by drawing together the anti-coalition group the Youth of Al Mahrah, led by Sheikh Ali Salem al-Hurayzi, and elements of the southern Hirak, including Ba’um. Hurayzi has strong tribal connections in both the north and the south, while Ba’um has been a leader of the separatist movement since it first emerged. Although Ba’um later withdrew from the Southern Salvation Council, the organisation remains popular as it opposes Saudi Arabia’s policy of controlling the governorate indirectly through development and relief projects, as well as its military presence. The council also opposes Emirati involvement in the governorate and, unlike most southern movements, supports Yemeni unity. While the Southern Salvation Council and the General Council fundamentally disagree about the future of Al Mahrah, they are united in their opposition to foreign intervention. Like Hadhramaut, Al Mahrah has been relatively successful in avoiding violent conflict due to the formation of tribal and technocratic alliances based on notions of a shared apolitical identity.

Soqotra

Soqotra is a world heritage site occupying a strategically important position between the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea. Yet there are no naval bases in Soqotra, as the islands are essentially inaccessible for around four months a year during the monsoon season. Mainly thanks to international interest in its unique ecology, as well as decades of migration to the UAE, the islands’ 60,000 inhabitants are increasingly connected to the outside world. Soqotri migration to the UAE in the past century has been an important factor – with most migrants going to Ajman, where they have become very wealthy relative to the situation at home. These close connections have enhanced Emirati influence on the islands.

The conflict in Soqotra has become a microcosm of the broader war between the IRG and the UAE. Two administrations now compete for control of the islands: as the UAE has increased its military intervention and “development” projects there, Saudi Arabia has attempted to mediate the confrontation between Emirati and IRG forces, with some success. For example, in May 2018 – when then Yemeni prime minister Ahmed bin Dagher refused to leave Soqotra unless Emirati forces withdrew from the islands – Saudi mediation facilitated the departure of some UAE troops. (Abu Dhabi later strengthened its presence there by sending in STC fighters.)

In October 2019, Saudi Arabia began a new mediation effort after the STC refused to hand over the headquarters of the Security Department to the head of security in the governorate recently appointed by Hadi. Earlier in the year, the IRG accused the Emiratis of training scores of separatist fighters and sending them to Soqotra. The UAE’s control over the islands is reflected in the fact that it continues to issue tourist visas to those travelling on direct flights to Soqotra, an initiative that the Soqotri and IRG authorities oppose. The STC’s strongman in Soqotra is Yahya Mubarak Saeed, who coordinated the Emirati recruitment initiatives and attempted to establish a Soqotri Elite Forces akin to those in Hadhramaut and Shabwa. Saeed, with the help of Emirati officer Khalfan Mubarak Al-Mazrouei, continues to call for protests against IRG-backed governor Ramzy Mahrous. Issa Salem bin Yaqut, an Oman-based senior sheikh of Soqotra, continues to campaign ferociously against the UAE’s presence, condemning it in testimony before the US Congress in October 2019. In brief, in early 2020, all Yemeni political parties and tendencies now have supporters in Soqotra and loyalties on the islands are, therefore, divided between Yemeni factions, the UAE, and Soqotra itself.

The Riyadh Agreement

On 5 November 2019, the STC and the IRG signed the Riyadh Agreement in the presence of Hadi, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and Emirati Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed. The deal followed an outbreak of fighting in August 2019, when the Security Belts and other UAE-backed STC militias took control of Aden. There had also been several earlier clashes between STC forces and the Saudi-backed IRG, particularly in Aden in January 2018 and in Soqotra throughout 2018 and 2019. As in some of the cases discussed above, Saudi Arabia led the mediation efforts that culminated in the agreement. The deal formalises the transfer of the coalition’s military presence in southern Yemen from the UAE to Saudi Arabia – a process that, in practice, dates back to June 2019, when the UAE announced its withdrawal from the Yemen conflict, leaving only a few of its military personnel behind (in coastal Hadhramaut, Shabwa, and Soqotra, and in control of the Bab al Mandab).

In 2019, not only had Houthi control of the northern part of Yemen progressed, and their incursions and missile launches against Saudi Arabia increased, but the implementation of the UN-sponsored Stockholm Agreement (signed in December 2018) stalled, while tensions with Iran also significantly worsened. In this context, the IRG’s loss of Aden as its interim capital presented a serious threat to the legitimacy of the government and undermined the Saudi-led coalition. It was, therefore, imperative for Saudi Arabia to re-establish the IRG in the city. Khaled bin Salman, recently appointed as Saudi deputy minister of defence, undertook major mediation efforts designed to impose an agreement on the STC and the IRG. This initiative to legitimise the Hadi government required cooperation from Saudi Arabia’s Emirati allies – which, judging by events in the months that followed the signing of the agreement, has been only partially forthcoming.

The agreement calls for the formation of a new, Aden-based government made up of 12 southern and 12 northern ministers (the previous administration included a higher proportion of southerners and a larger total number of ministers). Both sides’ military and security personnel are to be withdrawn from Yemen’s cities, alongside their heavy military equipment. Emirati-backed militias are to be integrated into the Yemeni armed forces under the authority of the Ministry of Defence, while other security services are to operate under the Ministry of the Interior. The leadership of the two ministries is due to change. Meanwhile, the new government will “activate all state institutions in the various liberated provinces … and work on the payment of salaries and financial benefits to employees of all military sectors”.

Under the agreement, all state financial resources are to be managed through the Aden-based Central Bank of Yemen, and to be accountable to parliament. This clause is likely to be unpopular for two reasons: firstly, some governorates – Marib, Hadhramaut, and Shabwa – have taken control of part of their oil revenues and, secondly, separatists have prevented parliament from meeting in Aden. The implementation of the agreement will require an unprecedented level of cooperation and compromise between not only Saudi Arabia and the UAE but also between Yemeni factions. As recent history suggests, this may be beyond the capacity and will of the parties, which have thus far demonstrated no commitment to peace or the welfare of Yemeni civilians. There have already been significant delays in the process – and there are doubts that it will succeed in 2020 – as southern governorates appear to be more firmly divided than ever between areas under the control of the IRG and the STC respectively. An indication of problems to come, and a major threat to the Riyadh Agreement as a whole, emerged on 18 January, when a missile attack killed more than 100 members of the Presidential Guard Unit who were stationed at a military camp in Marib and due to be redeployed to Aden. While the IRG blamed the Houthis for the attack, tensions between the IRG and the STC may well be connected to the incident, particularly given statements Zubaydi made to Agence France-Presse only a few days earlier.

The agreement is to be implemented under the supervision of a committee established by the coalition – which, given the UAE withdrawal, is dominated by the Saudis. This raises concerns about the sovereignty of the Yemeni state and the IRG. The arrangement is reminiscent of the power given in 2011 to the GCC Agreement, which contributed to the disintegration of Yemen. The Riyadh Agreement also shares other characteristics with similar arrangements in Yemen: a combination of imprecise implementation mechanisms, unrealistic deadlines, and idealistic sequencing. However, should direct Saudi-Houthi negotiations succeed, the threat to Yemeni sovereignty may recede as the Houthis are highly unlikely to allow Yemen to become a Saudi protectorate. Moreover, the Riyadh Agreement is a distraction from the coalition’s long-term goal of restoring the IRG to power throughout Yemen and driving the Houthis out of their strongholds.

The lack of a meaningful US response to the September 2019 missile attack on Saudi Aramco’s facilities persuaded Riyadh that Washington would not retaliate against Tehran on its behalf. This prompted Saudi leaders to seek to negotiate a ceasefire and settlement with the Houthis, contributing to their efforts to push for the Riyadh Agreement. On 20 November 2019, at the annual GCC summit, King Salman of Saudi Arabia publicly voiced his hope that the Riyadh Agreement would pave the way for a larger settlement between domestic Yemeni actors, indicating that the Saudi government had shifted towards recognising that the Houthis’ presence in Yemeni politics would endure.

One obstacle to the implementation of the Riyadh Agreement is its inability to resolve the fundamental disagreement between the IRG and the STC: the former seeks to maintain Yemen’s unity while the latter’s existence is predicated on calls for the secession of the south. To be effective, the agreement – which is exclusively tailored to resolving the dispute between the IRG and the STC – must somehow elide the fact that it is based on recognition of a unified Yemen. Another problem with the deal is that it ignores all other separatist groups. Given the complex political, economic, and historical factors discussed above, the agreement does not provide a holistic, long-term solution to either the southern question or to the Yemeni crisis as a whole.

The deal also depends on the UAE’s willingness to prioritise its relations with Saudi Arabia over its support for the STC. In recent months, there have been indications that the STC is weaker than it claims, as it has lost military control of all areas aside from those that are home to its main leaders. The organisation also refused to participate in the latest internationally sponsored meeting designed to help southerners reach a consensus (held in Brussels in December 2019). The STC even denounced Sheikh Saleh bin Farid al-Awlaqi – who was formerly their chief ally in Shabwa governorate, and who has shown considerable flexibility in his alignments in recent decades – for taking part in the meeting.

Thus, deep hostility between the STC and the Hadi government, and the exclusion of other southern political groups from the Riyadh Agreement, suggests that widespread praise for the deal may well be misplaced. The parties should learn from the Stockholm Agreement, which was signed more than a year ago to loud international praise but has been very partially implemented. The only real achievement of that deal has been to establish a patchy military ceasefire in Hudayda city – one that has not extended to other parts of the governorate.

Conclusion and recommendations

Within the south, there are numerous groups separated both by perceived identities and by competition over the region’s sparse natural resources. These groups are not defined by residence in the current governorates but by different factors: their allegiance is first to the memory of the “national” entities of Aden and the Protectorates and second to new political institutions and movements that emerged in the decades since unification. For example, in wadi Hadhramaut, there is now a political entity covering areas that were once part of both the Kathiri and Qu’ayti states but are unified thanks to a broad allegiance of low-status supporters of Islah. As a result, they form a significant part of the IRG’s military forces under the leadership of Vice-President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar. Further west, the alignments of the 1986 conflict largely overlap with the current rivalry between the IRG and the STC.

Strategically important, sparsely populated Al Mahrah is forced to deal with many external claims on its territory. Although Shabwa has some hydrocarbon resources and the Marib-Balhaf gas pipeline, these assets do not provide significant employment for its population. Further west, Abyan, Lahij, and Dhali’ – formerly part of the PDRY – have few natural resources and a largely poor population that has for centuries sustained itself through migration and raiding. The conflicts between the historical micro-states contained within these governorates are likely to re-emerge in a new form. Indeed, these governorates now provide most of the troops and leaders of Salafist forces the UAE has trained and deployed.

Meanwhile, the internationalisation of the Yemen conflict and the interests of the two main leaders of the coalition add another dimension to these rivalries. For instance, the situation in Al Mahrah has been shaped by Saudi Arabia’s determination to achieve one of its long-term strategic objectives: bypassing the constraints imposed by its reliance on the Strait of Hormuz, which threaten its access to the high seas for energy trade. Similarly, the UAE’s support for the STC in Aden and other ports is designed to develop Emirati maritime supremacy along the coasts of the Arabian Peninsula, as well as to exert influence over a rival to the IRG and thus to oppose Islah. Foreign military interventions in the past decade have deepened Yemen’s devastating humanitarian crisis and accelerated the administrative failures of both de facto and internationally recognised local authorities. These exogenous initiatives increase Yemeni dependency on external agencies while undermining the capacity of local actors and institutions to develop their own mechanisms for dealing with the situation.

The war has exacerbated the political fragmentation of the south and southern separatists have proven unable to overcome their factional rivalries or develop strategies that address the population’s social, economic, and political development problems. They offer no programme that generates support outside the region they represent and, therefore, are susceptible to foreign influence. While the south is torn between a multiplicity of diverging movements and separatist claims, the Houthis are running a tight ship in the areas they control, hoping to extend their governance model across the whole country. Although their ideology is widely abhorred, the Houthis offer the kind of strong, centralised control that some people long for. Just as many Yemenis opposed the socialist regime but respected it for imposing law and order – and for its broader organisational capabilities – they may see the benefits of Houthi rule, particularly given the chaos within the IRG. Fragmentation can be tempting: as the Tihami and other groups demonstrated in the National Dialogue Conference, allowing one political entity to claim special rights to a specific region only encourages others to follow suit.

In this complex and risky environment, European policymakers should be careful to avoid actions likely to further fragment Yemen and its south in particular. The country needs a strong but sensitive new government that the citizenry – who have come to see the force of arms as the authorities’ main form of control – view as just and legitimate. In designing and implementing interventions, foreign powers must take into consideration the historical, geopolitical, economic, and social nuances of southern Yemen. In the search of a settlement to end the war, the EU and other members of the international community should work to restore a sense of nationhood within Yemen. To this end, they should launch projects and other activities designed to reduce social tension between southerners and northerners. The EU should assist Yemeni parties in engaging in internal discussions on the future of the south within a united Yemen, providing them with a stronger and more durable opportunity for autonomy through a democratic process.

The policy of supporting Yemen as a unified state is important to prevent future strife, as the alternative is to allow the country to disintegrate into a multitude of mutually antagonistic, resource-poor micro-states – a phenomenon that would be particularly apparent in the south. There, the only area that has enough economic resources and political stability to operate independently is Hadhramaut – and Hadhramis have already made it abundantly clear that they would not accept being integrated into a southern state along the pre-1990 borders. The ambition of the STC and other southern separatist groups to re-establish a southern state is unrealistic for several reasons: given the considerable growth in population in recent decades, most of these entities would be economically unviable; Yemenis can only address their enormous problems, including those created by climate change and water scarcity, through cooperation within a national strategy. Moreover, such an attempt would exacerbate resentments originating in the numerous armed conflicts between the rival political entities discussed above, leading to further violence. Other tensions are also likely to emerge: in Hadhramaut the significant social tensions between tribes, the sada, and low-status agricultural workers are likely to increase in the face of rising sectarianism.

In contrast, a well-designed and carefully managed federal state could help heal these wounds without generating new grievances. Regional divisions within such a state should be based on social cohesion and equity of natural resources and economic potential rather than bureaucratic convenience. Dialogue between southern political entities, based on the social and economic situation of the areas they control, must continue. Yet, as demonstrated by the failures of the EU and others to promote this dialogue in the past decade, a new approach is necessary. Rather than bringing together existing factions and political parties, future dialogue should focus on social and economic development issues, seeking to identify programmes to solve the daily problems faced by the population. Here, the EU could sponsor a series of meetings and research initiatives covering various sectors.

Efforts to restructure Yemen administratively and politically should be based on a series of specific discussions of the country’s basic developmental problems in areas such as water, education, natural resources, agriculture, and social cohesion. Detailed analysis of, and proposals on, these sectoral issues could form the basis of further dialogue and, eventually, a framework for a federal structure that redraws the boundaries of each region. Ideally, this process should be led by technical experts rather than partisan actors, with the aim of devising solutions based on development potential rather than individual concerns. Such an approach would redefine southern regions based on their economic and political viability rather than factional interests and could contribute to restoring a sense of common identity and solidarity rather than the mutual hostility that is the characteristic of the current situation.

About the authors

Helen Lackner is a visiting fellow at the European Council for Foreign Relations and research associate at SOAS University of London. Her most recent book is Yemen in Crisis: Autocracy, Neo-Liberalism and the Disintegration of a State (published by Saqi Books in 2017; by Verso in 2019; and in Arabic in 2020). She is the editor of the Journal of the British-Yemeni Society and a regular contributor to Open Democracy, Arab Digest, and Oxford Analytica. She also speaks on the Yemen crisis at many public events, and has done so in the British House of Commons.

Raiman al-Hamdani is a researcher and consultant focusing on issues of security and development in the Middle East and north Africa. Born in Sana’a, he spent his formative years in Yemen, moving between the Netherlands, Sana’a, and New York. He has an MA in international security and conflict management from the American University in Cairo and an MSc in development studies from SOAS University of London as a Chevening scholar.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Saleh al Batati and two other people, who prefer to remain anonymous, for their assistance with data and analysis. The authors remain responsible for any errors in the text.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.