The crisis of European security: What Europeans think about the war in Ukraine

Summary

- The war in Ukraine could mark a watershed for European security.

- There has been much talk that European governments are divided over the conflict, but European citizens seem remarkably united around three key ideas.

- Firstly, they believe it is likely that there will be another Russian invasion of Ukraine.

- Secondly, they see this as a problem not only for Ukraine but for European security generally.

- Thirdly, they want Europe to respond to the crisis, with majorities supporting a response from NATO and the EU in particular.

- Europeans disagree on which are the most pressing threats linked to the crisis and on the price their countries should pay to defend Ukraine: people in Poland, Romania, and Sweden are much more willing to make sacrifices than those in France and Germany.

- The crisis will likely test Europeans’ readiness to defend the European security order.

Introduction

The Russia-Ukraine crisis could dramatically change the way Europeans think about their security. There is widespread speculation about whether Russia will invade Ukraine again – and, if it does so, how Europeans will react.

Much of the public debate on the crisis has portrayed European governments as divided, weak, and absent. However, a pan-European poll conducted by the European Council on Foreign Relations in late January 2022 shows that there is a surprising consensus on the crisis among European voters. Europeans in the north, south, east, and west agree that Russia is likely to invade Ukraine in 2022, that European countries have a duty to defend Ukraine, and that this is a European problem.

The survey covers Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Romania, and Sweden – countries that together account for almost two-thirds of the European Union’s population. It shows that Russian President Vladimir Putin has succeeded in putting the question of the European security order on the table. To the surprise of many commentators – and likely Putin himself – this has prompted a geopolitical awakening among Europeans. The results of the survey point to four fundamental observations: that war in Europe is no longer unthinkable; that we should respond to Russian aggression; that Europeans’ biggest fears related to the crisis differ from country to country; and that European governments need to plan for various contingencies to ease the burden on ordinary citizens.

War in Europe is no longer unthinkable

At the beginning of the covid-19 pandemic, some European governments framed the fight against the virus as a war. Now, fear of a real war is stalking Europe. There is no longer much truth in the cliché that Europeans believe war is unthinkable and take peace for granted. As ECFR’s new poll reveals, they perceive their world as being in a pre-war rather than post-war state. In every surveyed country apart from Finland, most respondents believe it likely that Russia will invade Ukraine again in 2022.

It is clear that, unlike in 2014, Europeans view the conflict in Ukraine as a European crisis. Seventy-three per cent of respondents in Poland see an invasion as likely. The same is true of 64 per cent in Romania, 55 per cent in Sweden, 52 per cent in Germany, 51 per cent in France and Italy, and a plurality of 44 per cent in Finland. It seems that being neutral might take the fear out of military conflict.

In Poland, for reasons of history and geography, respondents see the prospect of a Russian invasion as an existential crisis. Poles in all age groups need to reckon with an escalation in the Russia-Ukraine war. In the other surveyed countries, there is an interesting generational divide. In France and Sweden, people over the age of 60 are more inclined to see an invasion as very likely. In Romania, Italy, Germany, and Finland, it is the youngest generation – people born after the end of the cold war – who are most worried.

Putin has succeeded in his attempt to grab Europe’s attention, but this has come at a cost. As ECFR’s new survey demonstrates, more than half of Europeans agree that Russia’s approach to Ukraine represents a security threat to Europe as a whole in a variety of domains.

Ukraine matters, but national responses are not enough by themselves

As shown by a poll ECFR conducted late last year, until recently, most Europeans thought that any future ‘cold war’ would be a confrontation between the United States and Russia or China. Europeans would be spectators rather than participants in this conflict. Indeed, when the Russian troop build-up on Ukraine’s border began, there was a lot of speculation in the media that Europeans would not really care about the crisis.

ECFR’s latest survey reveals that this assumption was wrong. It is probably true that more Europeans still view Ukraine as large and chaotic than as small and heroic. However, most of them agree that Ukraine should be defended. The question is: who should step up?

In almost all surveyed countries, most respondents see NATO as the organisation best positioned to defend Ukraine. Remarkably, the exception is Poland, where slightly more people see the EU in this role.

It may be unsurprising that the threat of Russian invasion has revived the West of the cold war era. But, intriguingly, it has also challenged the popular perception that, when it comes to security, eastern Europeans are ready to dismiss the EU because they view the US as their only reliable partner. In fact, in all surveyed countries except Germany, most people believe that both NATO and the EU should respond to Russian aggression.

It is true that Europeans differ on whom they trust to protect their interests in the event of another Russian invasion of Ukraine. Respondents in Poland, Germany, Romania, and Italy primarily trust NATO to do so, whereas those in France, Sweden, and Finland mostly trust the EU. Sweden and Finland are the only surveyed countries outside NATO but, as ECFR’s poll shows, in neither state is there a public consensus on whether to join the alliance. In Sweden, 30 per cent of respondents are glad that their country is not a member of NATO and 33 per cent say it is a bad thing; in Finland, these figures are 35 per cent and 25 per cent per cent respectively.

But the EU is not really divided in the Manichean way that many assume – between those who trust NATO and those who trust the EU. More than 60 per cent of Poles, Romanians, and Italians trust the EU to protect EU citizens’ interests if Russia invades Ukraine. Similarly, most Swedes and Finns trust NATO on that front, not just the EU.

At the same time, French and German respondents have the least trust of all national groupings in the EU’s capacity to protect its citizens.

While most Europeans believe that Ukraine should be defended, there are major differences between them about how to do it. While 65 per cent of Poles believe Poland should come to Ukraine’s defence, the prevailing view among respondents in Finland, Italy, and Germany is that their own countries should not do so.

But, even in Poland, more respondents see the main defenders of Ukraine as being the EU (80 per cent) and NATO (79 per cent) than see their own country in this way. This could indicate that, for most Europeans, defending Ukraine means defending the post-cold war European security order rather than simply taking a side in the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Therefore, they expect both NATO and the EU to act.

The poll also makes clear that, while most Europeans still trust NATO to defend Europe, “NATO” is no longer just another name for “the United States”. Europeans trust NATO to protect their interests more than they trust the US to do so. This may reflect the fact that they increasingly view the US as only a part-time European power, as these authors observed in a previous ECFR paper. In all surveyed countries aside from Poland and Romania, more respondents believe that Germany is in a better position than the US to protect EU citizens’ interests if Russia invades Ukraine again.

ECFR’s survey also proves that Brexit means Brexit. London’s much-publicised show of solidarity with Kyiv notwithstanding, very few citizens anywhere in Europe see much of a role for the United Kingdom. Only in Poland (66 per cent) and Sweden (52 per cent) do most respondents think that the UK should come to Ukraine’s defence.

The political differences within surveyed countries may be even more striking than those between them.

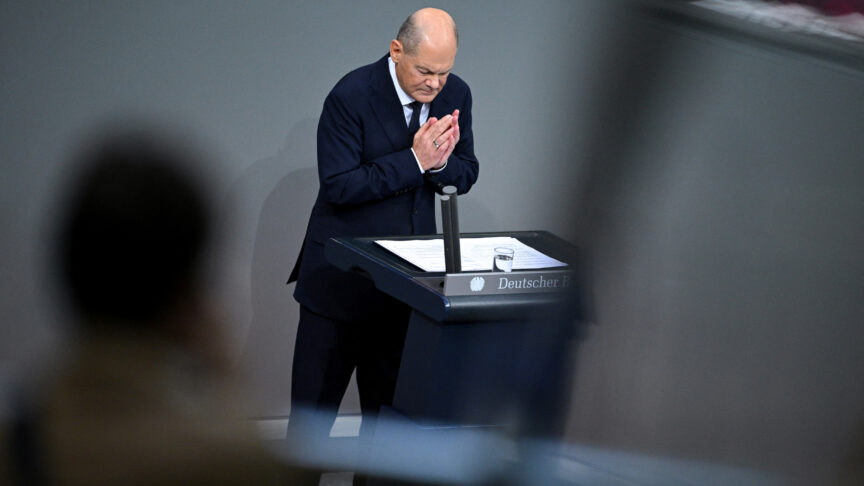

In Germany, contrary to stereotypes, it is supporters of the centre-left parties in government rather than the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) who express the most willingness to defend Ukraine. Most current supporters of the greens and a plurality of Social Democratic Party voters want Germany to defend Ukraine. Among those who vote for the CDU, marginally more respondents do not want Germany to defend Ukraine than want it to do so.

In France, supporters of President Emmanuel Macron and his centre-right challenger, Valérie Pécresse, want France to defend Ukraine. But – unlike in Germany, where most people who vote for the largest far-right party (Alternative for Germany) do not want their country to do so – supporters of nationalist leaders Marine Le Pen and Eric Zemmour are divided on this issue.

This is also the case for supporters of all the major parties in Italy – which is widely perceived as one of the EU member states most sympathetic to Russia. Those who vote for the Democratic Party are the most eager (55 per cent) to see their country come to Ukraine’s defence – but 40 per cent of the party’s supporters have the opposite opinion. Similarly, while 54 per cent of those who vote for the far-right Brothers of Italy say that their country should not defend Ukraine, 37 per cent say that it should. Interestingly, supporters of Matteo Salvini’s far-right League are similarly split on this issue.

In Poland, a large majority of supporters of all parties want Poland to defend Ukraine. However, when asked whom they trust to protect the interests of EU citizens in the event of a Russian invasion of Ukraine, supporters of the ruling Law and Justice party are the only grouping in which most people trust the Polish government to do so – in a reflection of the country’s political polarisation.

Same conflict, different fears

“Remember what the Kremlin did to you last time” is the phrase that best sums up Europeans’ fears about a conflict between the West and Russia. This holds true for their biggest security concerns about the prospect of another Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Respondents in Poland are most worried not just about Russian military action against their own country but, equally, about the ways in which the conflict could cause Ukrainians to flee Ukraine – a concern likely heightened by the migration crisis on the border between Poland and Belarus. Germans, Finns, Romanians, and Italians primarily fear that Russia will cut off their energy supply. (For Romanians, an equally important threat concerns an economic downturn, probably reflecting the country’s historically unstable economic situation.) Meanwhile, French and Swedish citizens are most worried about cyber-attacks – probably due to Moscow’s recent attempts to interfere in their elections.

So, there are national differences on these key issues. But, overall, Europeans see energy dependency as their most significant shared challenge in dealing with Russia: majorities in all surveyed countries apart from Sweden (47 per cent) say that this poses a major threat.

What price will Europeans pay to defend Ukraine?

Europeans now know war in Europe is possible, but are they prepared for this kind of war? Today, geopolitical strength is determined not just by military and economic power but also by the capacity to endure pain. Unlike during the cold war, the opponent is not someone behind an iron curtain but someone from whom you buy gas and to whom you export high-tech goods. This makes them not just potentially open to the EU’s values and messages, but also vulnerable to European economic pressure. While these connections are pathways for European soft power, they could also test the EU’s resilience.

The West’s strategy for deterring Russia from launching another invasion of Ukraine is to make such an intervention more costly for the Russians. This involves a mixture of military deterrence in eastern Europe, arms shipments intended to bolster the Ukrainian military, and planning for a series of sanctions in various domains. The success of any strategy centred on sanctions will depend on Europeans’ willingness to make economic sacrifices.

However, Poland, Sweden, and Romania are the only surveyed countries in which respondents who are willing to bear all the main burdens of defending Ukraine (including the threat of Russian military action) outnumber those who are not. Most worryingly, French and German citizens are among the least willing to bear these burdens, suggesting that they believe the risks of doing so outweigh the rewards.

Only in Poland are most respondents willing to accept the risks of an economic downturn, higher energy prices, cyber-attacks, a refugee crisis, and Russian military aggression to defend Ukraine. In Germany, France, Italy, and Finland, pluralities of respondents think that it is not worth doing so if this would risk an economic downturn. They mainly seem to support sanctions that will hurt Russia but will not hurt them.

The survey data also reveal a generational divide. There are interesting differences in the perceptions of the oldest and the youngest generations in eastern and western EU member states.

The results of the survey in Finland appear to reinforce stereotypes about ‘generation snowflake’. Although young Finns are relatively likely to believe that a war is looming, they are less willing than those over the age of 60 for their country to defend Ukraine if this would risk an economic downturn, higher energy prices, a refugee crisis, cyber-attacks, or Russian military action.

Similar trends are evident in Poland. There, although older people are as likely as the young (73 per cent) to think that the threat of Russian military action against Ukraine is real, they are more likely to believe that it is worth taking all these risks to defend Ukraine.

Yet the generational divide is very different in other surveyed countries, especially France and Germany – where younger people are more willing to make sacrifices than older ones in all areas. Surprisingly, in France, young respondents are much more willing than their older counterparts to endure the risk of Russian military action to defend Ukraine.

Conclusion

If Putin threatened Ukraine to force Europeans to think about the viability of the European security order, he has succeeded. But, judging by the results of ECFR’s newest poll, the Russian president might be surprised that most Europeans seem ready to defend Ukraine.

These authors’ interpretation of the survey results is that Europeans would see another Russian invasion of Ukraine as an attack not just on a neighbouring country but on the European security order itself. And it is striking that so many respondents – in the north, south, east, and west – think this order should be protected.

What will probably not surprise the Russian president is that, while Europeans are ready to stand behind Ukraine, they are less enthusiastic about paying the financial costs of deterring Russia.

The next few weeks will test whether Europeans can make the transition from a world shaped by soft power to one shaped by resilience. The way in which they deal with this test will be pivotal to the future of European security.

Methodology

This report is based on a public opinion poll that Datapraxis, AnalitiQs, and Dynata carried out for the European Council on Foreign Relations in Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Romania, and Sweden. The survey was conducted in the last ten days of January 2022, with an overall sample of 5,529 respondents.

This was an online survey in Finland (n = 500), France (n = 1,000), Germany (n = 1,000), Italy (n = 1,014), Poland (n = 1,015), Romania (n = 500) and Sweden (n = 500). The results are nationally representative of basic demographics and past votes in each country. The general margin of error is ±3 per cent for a sample of 1,000 and ±4 per cent for a sample of 500.

The exact dates of polling were: Finland (21-29 January), France (21-28 January), Germany (21-30 January), Italy (21-28 January), Poland (21-28 January), Romania (21-28 January), and Sweden (21-28 January).

Acknowledgments

The authors would especially like to thank Lucie Haupenthal once again for her inspirational support in the writing and research of this policy brief under extreme time pressure. They would also like to thank Pawel Zerka and Gosia Piaskowska, who spotted some of the most interesting trends and carried out painstaking work on the data that underpin this report, as well as Marlene Riedel and Chris Eichberger, who worked on visualising the data. Susi Dennison made sensitive and useful suggestions on the substance. Chris Raggett has been an admirable editor. Andreas Bock led on strategic media outreach, actively supported by Katharina Egle, and Juan Ruitiña supported us in launching this report so quickly after we received the data. The authors would also like to thank Paul Hilder and his team at Datapraxis for their patient collaboration with us in developing and analysing the polling referred to in the report. Despite these many and varied contributions, any mistakes remain the authors’ own.

About the authors

Ivan Krastev is chair of the Centre for Liberal Strategies, Sofia, and a permanent fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna. He is author of Is It Tomorrow Yet?: Paradoxes of the Pandemic, among many other publications.

Mark Leonard is co-founder and director of the European Council on Foreign Relations. He is the author of Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century and What Does China Think?. His new book, The Age of Unpeace: How Connectivity Causes Conflict, was published on 2 September 2021. He also presents ECFR’s weekly ‘World in 30 Minutes’ podcast.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.