Mapping African regional cooperation: How to navigate Africa’s institutional landscape

Summary

- Regional organisations have proliferated in Africa in recent decades, with many organisations attempting to address similar issues in similar parts of the continent.

- International donors have helped create this situation by funding new and existing African regional organisations without questioning the downsides of doing so.

- In recent years, African regional organisations have increasingly sought to concentrate on security issues, contributing to a rise in the use of ‘hard security’ solutions at the expense of ‘people-centred’ approaches.

- This proliferation comes with further costs, such as wasted resources, and ‘forum shopping’ by state leaders.

- Europeans and other international donors should take stock of the situation they have helped create. As a first step, they should agree a tacit ‘non-proliferation agreement’ before considering other options.

Mapping African regional cooperation

This project maps African regional initiatives in west and central Africa and provides a data-based and a geographical overview of the ‘à la carte’ nature of African regional cooperation

Introduction

Long before African countries gained independence, they pursued closer integration and cooperation among themselves through the creation of multiple African regional organisations. In the aftermath of war trauma in Somalia, Liberia and Sierra Leone, and the 1994 Rwanda genocide, many African regional organisations expanded their agenda to incorporate prevention and conflict management. At the same time, there has been intense international engagement in Africa in the fields of diplomacy, security, development, and humanitarian assistance since the 1990s. In 2002 the creation of the African Union and the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) accelerated the development of security policies.

For most African regional organisations, playing a role in peace and security provides their members with more international visibility, and makes it easier for them to receive financial support and to benefit from institutional capacity building programmes led by external partners such as France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union. In recent times, these international players have been especially preoccupied with security matters and their potential knock-on effects for other parts of Africa and Europe. But, while some African regional organisations are crucial political and operational actors and receive significant support from international donors, those that have expanded their mandate in peace and security still lack sufficient human, logistical, and financial capacities to prevent the outbreak of armed conflict and deal with spillover effects.

There has long been a gap between donors’ expectations, African regional organisations’ objectives, and the latter’s capacity to deal with regional security challenges. This gap is still difficult to bridge, mainly because there has been only inconsistent international support for African responses to tackling volatile conflict situations. Such support lacks coordination, to the point that it may well be undermining both the effectiveness of African mechanisms and donors’ efforts to achieve their policy goals.

This paper traces the recent history of African regional organisations, including the growth in the number of security-orientated regional organisations, focusing on west and central Africa. The paper identifies problems in the African institutional landscape, including the costs of the overlap between African regional organisations (where a state is a member of more than one African regional arrangement at the same time; and where these arrangements share similar agendas on peace and security), and of ‘forum shopping’ by African states and their leaders. The situation does not ultimately address the long-term development problems that exist in many states.

The first main problem is that external support from European states and other international actors will not be as effective as it could be without national and regional coherence. In the context of the proliferation of African regional organisations, these actors should, therefore, develop a clear view of the costs and benefits of multiple and overlapping memberships.[1] When they do have a view on the matter, bilateral and international partners tend to agree that African states should address the issue of overlap among African regional organisations – but they never really take into account their own responsibilities for producing such a situation.[2]

The second main problem results from tension between the official promotion of shared objectives, their translation into long-standing regional policies, and the more informal practice of ‘à la carte’ cooperation – of leaders opting in and out of African regional organisations as they please. The lack of coordination between African regional organisations reflects the competitiveness of the political-institutional environment. In direct relation to the lack of coherent strategies, the opportunistic behaviour of African political leaders and the proliferation of African regional organisations are both the cause and the consequence of this forum shopping. Far from being a new practice, forum shopping is regarded by political elites as a way to invest in flexibility, including by adapting to the changing security context; defending national interests; cooperating with states they border (which are sometimes rivals); and developing relationships with external actors. In the long term, forum shopping has significant human, financial, and material costs for African and European stakeholders.

A complex regional landscape

Over the last 20 years, states in west and central Africa have signed a growing number of regional agreements. The organisations created by these agreements have both proliferated in number and, at the same time either expanded their mandates into peace and security matters (in the case of longer-standing entities) or developed into new bodies focusing on peace and security. Thus, there has been an increase in the number of organisations, the scope of their mandates, and the number of activities they collectively pursue.

A brief history of African regional organisations: The recurring proliferation battle

The African institutional scene has a long and complex history. The scene has often been characterised by a battle between the need and desire for forms of pan-African and regional economic and political integration on the one hand, and efforts to contain the mushrooming of organisations that this need and desire generate on the other.

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU) was founded in 1963, during an era in which African countries were becoming independent. This was effectively the predecessor to today’s AU. Most of present-day Africa’s economic groupings came into existence before the establishment of the OAU. For instance, the Conseil de l’Entente, a west African-led initiative to promote closer and more dynamic political and cultural integration, was established in 1959.

In response to this proliferation of African regional organisations, a first phase of rationalisation took place in the 1980s and the early 1990s – starting with the Lagos Plan of Action and the Final Act of Lagos in 1980. This phase was marked by several attempts to limit institutional overlap, duplication, and quarrels over legitimacy between regional institutions. The Lagos plan and act set the objective of establishing one economic grouping per geographical region, as defined in an OUA decision in 1976 to divide the continent into five regions (west, central, north, south, and east). But this failed to produce the desired results.

A second phase of rationalisation occurred during 1995-2002, drawing on lessons from the first one by attempting to focus efforts on areas of obvious overlap. Africa’s regional integration was based on the coordination, harmonisation, and progressive integration of Regional Economic Communities (RECs), which are effectively the building blocks of the African Economic Community (AEC), established by the 1991 Abuja Treaty. This treaty established a framework for economic integration across Africa. For a time, there were 14 RECs. However, the OAU made only limited progress in economic development and conflict management. And African states regularly resorted to using ad hoc mechanisms. The institutional landscape that emerged was unable to prevent conflict or to enable coherent regional or pan-African action.

The AU was formed to update and consolidate a collective security system that, in time, became better known as APSA (see box). The latter provided another opportunity to put in place a “clear blueprint and neatly assembled structures, norms, capacities, and procedures”, as one former secretary-general of the OAU put it. RECs remain formally independent of the AU, but they all maintain a close relationship with it and are the only African regional organisations to become pillars of APSA. In 2006, following an expert report that identified more than 200 intergovernmental organisations in Africa, the AU decided to reduce the number of RECs to eight.[3] Despite efforts since then, however, the number of African regional organisations has not fallen.

What is APSA?

Established in 2002, the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) consists of a variety of structures and norms, all of which sit under the AU. APSA’s role is to prevent and manage conflict, and to engage in peacebuilding efforts across the continent. Its component parts include the Peace and Security Council (PSC), a political body modelled on the UN Security Council; the African Standby Force (ASF), which has five pre-positioned regional forces; the Continental Early Warning System (CEWS), designed for data collection and analysis; the Panel of the Wise (PoW), which has a preventative and mediatory role; the Military Staff Committee (MSC), which advises the PSC on military issues; and the Peace Fund. By creating APSA, African states aimed to assume primary responsibility for peace and security on the continent, and to establish a structure to assemble the necessary financial, political, and military means to do so. APSA receives capacity building support from organisations such as the United Nations and the European Union, and from its national partners. Some of these partners – such as France, the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States – have a long tradition of cooperation with Africa. Others are non-Western countries with a growing peace and security role in Africa, such as China.

Types of African regional organisation

The term ‘African regional organisation’ covers a diversity of groupings with different institutional forms. They vary in the types of activity they engage in, from some that are just political forums used for discussion to others that carry out military deployments. For the purposes of this paper, an African regional organisation is as an institutionalised cooperation format involving three or more countries in west or central Africa, or both areas (as in the case of Nigeria). Using this definition, it is possible to identify five categories of African regional organisation by looking at their relationships with the AU.

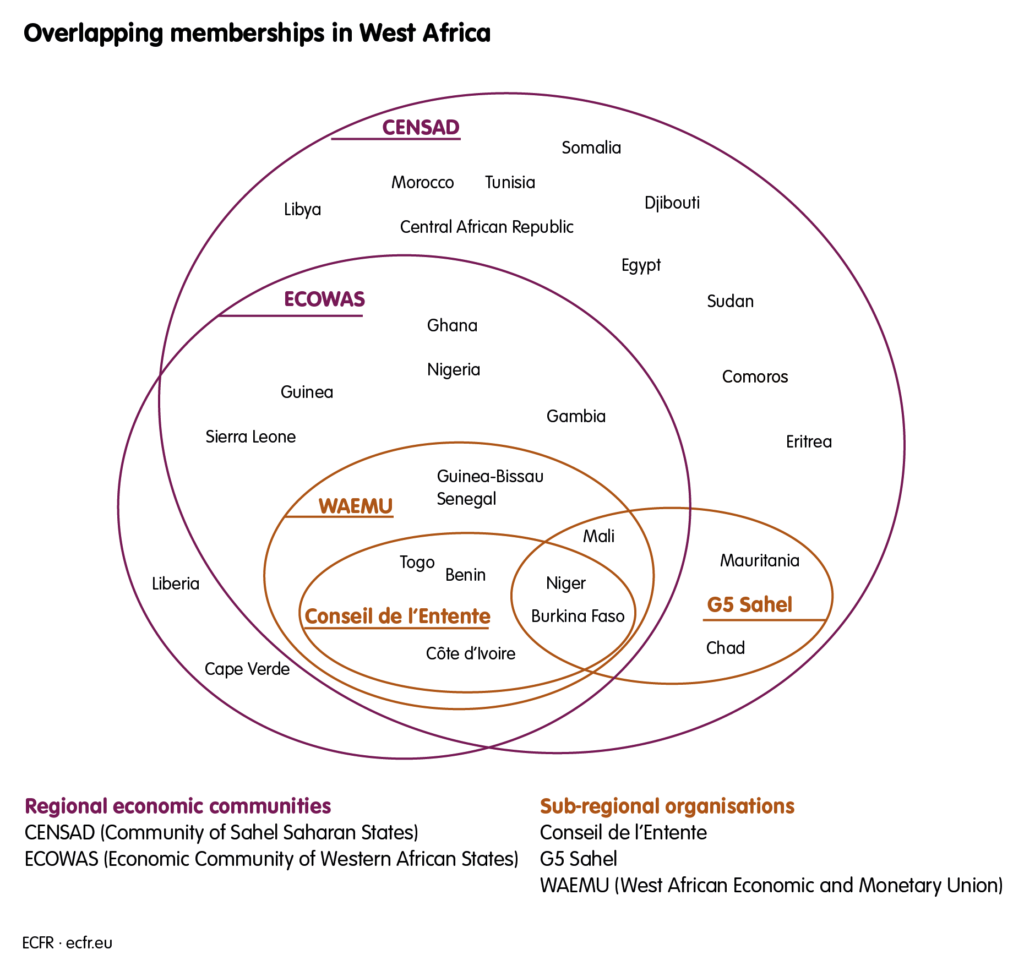

- Post-independence organisations focused on regional integration: Examples of this type of African regional organisation include the Conseil de l’Entente, the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC), and the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU; UEMOA in French). Unlike the Conseil de l’Entente, which is an African-led initiative and was established a year before independence, CEMAC and WAEMU are continuations of colonial arrangements in west and central Africa after decolonisation, in the form of the CFA franc zone. WAEMU and CEMAC were considered to be sub-RECs until 2006, as subsets of a broader REC. WAEMU has had observer status at the UN General Assembly since 2011.

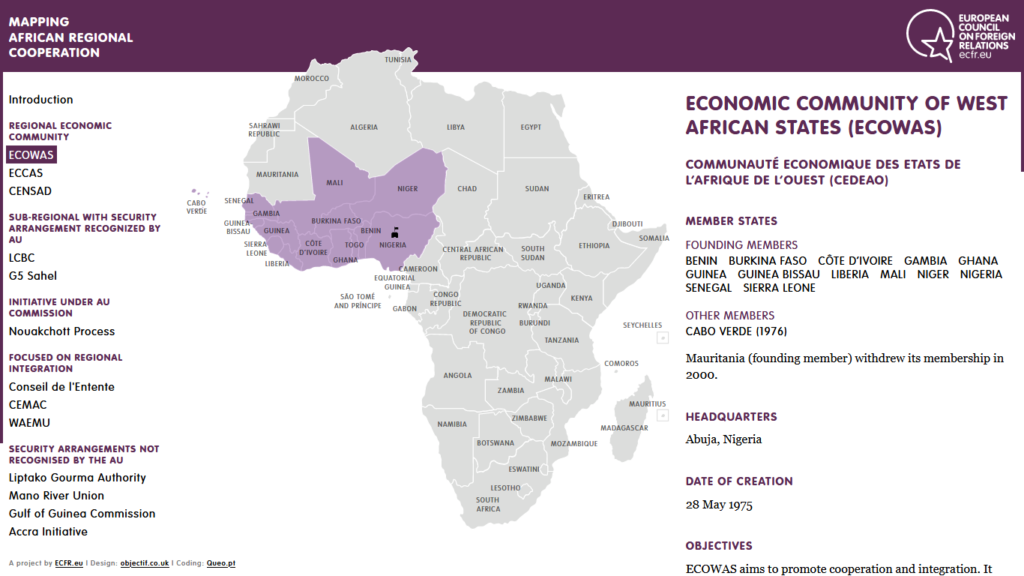

- Regional economic communities: RECs are the building blocks of the AEC. The Abuja Treaty established a framework for economic integration across Africa. Examples of RECs in west and central Africa include the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), and the Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD). Two of these cooperation frameworks – ECOWAS and ECCAS – were favoured by state leaders: CENSAD became a REC in 2000 on the initiative of Muammar Qaddafi, as Libya was one of five African countries contributing to the AU budget. The role of the RECs and of Regional Mechanisms on peace is officially recognised in Article 16 of the AU PSC Protocol. And their relationship with the AU was established in a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in 2008. While they are formally independent, RECs/Regional Mechanisms seek a high level of cooperation with the AU. And the functioning of several components of APSA, such the ASF and the CEWS (see APSA box), depends on regional structures.

- Sub-regional organisations with security arrangements recognised by the AU: Examples of this type of African regional organisation include the G5 Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC), the latter of which was originally created in 1964 to regulate and control the use of water and other natural resources. Although these African regional organisations are not part of APSA, the AU authorised the deployment of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), which is led by the LCBC, and the Joint Force of the G5 Sahel.

- An initiative under the auspices of the AU: The Nouakchott process is the principal example of this type of African regional organisation. The process was created to enhance security cooperation and operationalise APSA in the Sahel-Saharan region. It provides a framework for discussion and exchanges of information. It is overseen by the AU Commission, which is the AU’s permanent secretariat. In addition to adopting numerous texts and decisions on terrorism, arms trafficking, and even border cooperation, the AU has since the 2000s set up mechanisms and tools for Africa as a whole (such as the African Centre for the Study and Research on Terrorism and the Committee of Intelligence and Security Services of Africa) and for the Sahel-Saharan zone (such as the Chiefs of Staff of the Joint Operational Army Staffs Committee and the Fusion and Liaison Unit). Algeria has played a key role in supporting the AU in this effort.

- Security arrangements not recognised by the AU: Examples of this type of African regional organisation include the Accra Initiative, the Gulf of Guinea Commission, the Liptako-Gourma Authority (LGA), and the Mano River Union. The category includes African regional organisations and regional arrangements established over a longer period of time, from the LGA, which was created in 1970, to the Accra Initiative, which launched in 2017. A feature they share is their goal of enhancing security cooperation, among other activities, by focusing on local cross-border dynamics. That said, the Gulf of Guinea Commission concerns itself with inter-regional (between west and central Africa) rather than local cooperation, and it focuses on maritime security. Although these organisations have no AU or UN endorsement, they generally benefit from the financial or political support of international actors, particularly that to develop national capacities or to implement their regional projects and activities.

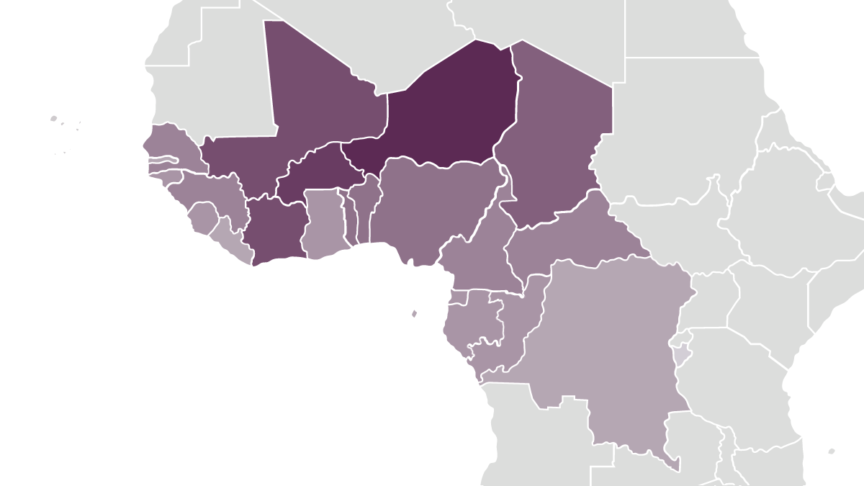

With few exceptions, the research for this project reveals that countries in west and central Africa belong to an average of four African regional organisations each. Among the 13 organisations and initiatives covered in the project, some countries – such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gambia, and Liberia – belong to only two African regional organisations each, while Burkina Faso belongs to no fewer than eight, and Niger to nine. In terms of membership, African regional organisations in west and central Africa overlap in two different ways. Firstly, subsets of larger organisations form when a small number of member states creates a new group because they are dissatisfied with the existing one. For example, all central African states belong to ECCAS; six of these countries also belong to CEMAC, the central African CFA franc zone. Such overlap is more common between countries in central and east Africa, such as Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Rwanda.

Memberships by numbers

Countries in west and central Africa belong to an average of four African regional organisations. (Cape Verde and Burundi are only members of ECOWAS and ECCAS respectively.) There are substantial differences between these countries in the number of African regional organisations they have joined: the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gambia, Liberia, and Sao Tomé belong to two; Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, and Sierra Leone belong to three; the Central African Republic and Senegal belong to four; Benin, Nigeria, and Togo belong to five; Chad belongs to six; Cote d’Ivoire and Mali belong to seven; Burkina Faso belongs to eight; and Niger belongs to nine.

Memberships also overlap where a smaller group of states sets up new regional cooperation mechanisms that are independent of existing ones. This was apparent in west Africa even before the outbreak of the Mali crisis in 2012. For example, among the 15 members of ECOWAS, 13 are also members of CENSAD, and eight of WAEMU. Five of these eight countries make up the Conseil de l’Entente.

How insecurity drives proliferation

The rise of insecurity in the last couple of decades is an important part of the recent history of the African institutional landscape. Significant security problems and their transregional dimension have generated a rise in the number of African regional organisations, with various actors seeking to respond to issues as they emerge, and external donors agreeing to fund them. Furthermore, the security agenda is, in principle, meant to go hand in hand with development measures, according to African regional organisations’ own mandates. But security has come to dominate over other considerations. The resulting focus on military solutions is also inconsistent with African regional organisations’ rhetoric, which usually emphasises the human security approach, centred on people’s political, economic, social, agricultural, health, and environmental vulnerabilities. Many states in west and central Africa face great challenges of human security, such as extreme poverty, an absence of wealth redistribution, institutional weaknesses, limited or no governance, youth unemployment, and a lack of women’s empowerment. These problems are aggravated by long-standing – and, in some cases, intensifying – transnational challenges such as rapid population growth, food crises, climate change, irregular migration, organised crime, and jihadism. And, despite the significant support African regional organisations have received from their international partners over the decades, there remains a risk of spillover effects from violent conflict in areas such as the Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin – where the root causes of conflict are national.

African regional organisations vary considerably in the extent to which they engage with security matters. They range from forums where states can discuss the security agenda and exchange information, such as the Nouakchott process, to those that have also developed capacities for joint military exercises or to coordinate peace operations, such as ECOWAS and ECCAS. In the last two decades, many African regional organisations in west and central Africa have significantly expanded the scope of their security activities. WAEMU, the Conseil de l’Entente, LCBC, and the LGA have all gone down this path. Countries in the region have also established new African regional organisations whose main or sole focus is on security, such as the G5 Sahel and the Accra Initiative.

The growth in overlapping mandates takes place as different organisations take on different responsibilities. Many African political leaders have long seen political cooperation and economic integration between countries and regions as indispensable to development. The creation of mechanisms for conflict prevention and management was designed, at least in part, to generate mutual trust between states. Among the 13 African regional organisations featured in the mapping project that accompanies this paper, all those created between the 1960s and the 1970s have, since the early 2000s, revised their constitutive treaties to expand their competences into peace and security. This demonstrates a clear shift this century from a developmental and economic focus to one that incorporates security.

When did regional organisations adopt new legal framework to expand their competences into peace and security?

ECOWAS (1999), Mano River Union (2000), ECCAS (2000), CENSAD (2000), CEMAC (2004), Conseil de l’Entente (2011), LCBC (2012), WAEMU (2013), LGA (2017).

For instance, ECOWAS made this change as early as 1999, when it adopted the Protocol Relating to the Mechanism for Conflict Prevention, Management, Resolution, Peace-Keeping and Security. It did so to try to institutionalise the progress on security made in the 1990s during its interventions in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea-Bissau. By adopting the mechanism, ECOWAS confirmed that it had abandoned its principle of non-interference, which had been the subject of much debate at the time of its intervention in Liberia. The Lake Chad Basin Commission made a similar change in 2012, when it took a formal decision to reactivate the MNJTF – which had been in existence since 1998 but had not been used.

Focus on: ECOWAS

This securitisation trend has manifested itself in various ways. Firstly, some African regional organisations took on security activities before only later formally acquiring a regional mandate to do so. For example, the conflict in Mano River Union countries forced ECOWAS to intervene before later broadening its mandate in 1999. In contrast, ECCAS established a security mandate in 2003 but took five years to translate it into action, with a military deployment in the Central African Republic. And some African regional organisations, such as the G5 Sahel, effectively came into existence as completely new bodies.

The Sahel

The instability in the Sahel in the last eight years provides a good example of how this proliferation can take place. The crisis there has prompted the proliferation of regional arrangements that seek to deal with its spillover effects.

In the last decade, African and European countries have grown increasingly worried about the deteriorating security situation in the Sahel, where the spread of armed groups, transnational organised crime, and insecurity and poverty has increased migration to Europe. International organisations that have adopted Sahel strategies or initiatives include the World Bank (2013), the EU (2011), and the UN (2013).[4]

After the political-security crisis arose in Mali in 2012, west African states explored several options for the deployment of a military force in the country: the ECOWAS Standby Force, the ECOWAS mission in Mali, the African-led International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA), and the Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). Multiple changes in the format of the force – from ECOWAS to the AU to the UN force – were symptomatic of a chaotic decision-making process within ECOWAS, blockages resulting from internal policies on the Malian side, a lack of coordination with the AU, a glaring lack of financial means on the part of ECOWAS, and the inability of the organisation’s Committee of Chiefs of Defence Staff to quickly develop a concept of operations or a plan for an operation of the magnitude required to respond to the scale of the crisis. The situation in the Sahel had revived a long-standing institutional rivalry between the AU and ECOWAS, the latter of which had sought to become the main regional security actor in west Africa.

In 2013, having learned from Africa’s lack of rapid deployment capacity in the Mali crisis, the AU created the African Capacity for Immediate Response to Crisis (ACIRC). This was initially designed to be a voluntary framework for rapid intervention in crises across the continent, pending the operationalisation of the African Standby Force (ASF). Yet, over the last seven years, it has, like the ASF, never been deployed. Policymakers are now considering whether to harmonise the flexible elements of the ACIRC within the ASF to avoid duplication. Ultimately, this slow-moving and ineffectual response by the AU meant it failed to provide leadership in the Sahel. The Mali crisis became internationalised, as shown by the transformation of AFISMA into the United Nations’ MINUSMA in 2013. This paved the way for the launch of the G5 Sahel Joint Force, which seeks to fight terrorism in particular.

The G5 Sahel Joint Force, announced in November 2015 by these five African states, institutionalises the practice of regional, cross-border military cooperation. The force aims to fill the gap left by the operationalisation of the ECOWAS Standby Force and its rivalry with the AU over political control of the military intervention in the Sahel. The creation of the G5 Sahel Joint Force and the AU’s clear and formal demand for the force to have a UN mandate have been key components in the development of closer ties between the G5 Sahel and the AU.

In March 2017, the AU PSC endorsed the G5 Sahel Joint Force’s concept of operations, authorised the deployment of the force, and then transmitted this concept to the UN Security Council. In January 2017, the election of the new president of the AU Commission, Chadian leader Moussa Faki Mahamat, who has an excellent knowledge of Sahel, strongly favoured a shift in the AU’s policy on the G5 Sahel. Although the G5 Sahel has the political support of the AU, the AU is not providing any additional support to the G5 Sahel – in contrast to MINUSMA providing logistical support to the G5 Sahel Joint Force within the framework of its mandate. The G5 Sahel has not received resources from the AU as the former organisation is funded only by bilateral grants. Following the adage, ‘he who pays the piper calls the tune’, states that make the greatest financial contribution to the G5 Sahel may have sought to influence its agenda. While the difficulties of deploying the ACIRC and the ASF justified the creation of new regional coalitions, the G5 Sahel Joint Force has encountered the same type of challenges: the structural weaknesses of national armies – from both an operational and logistical point of view – the failure of internal governance and democratic control of these forces, and their exactions on the populations are identical whether they are deployed as part of an ECOWAS force, the AU, the G5, or the LCBC.

A competitive environment: Institutionalisation, cooperation, and coordination

The proliferation of African regional organisations has created a complex set of challenges. These include a tug of war over whether to formalise ad hoc arrangements; fitful efforts at cooperation between African regional organisations that cover different regions; and similarly sporadic attempts to coordinate activity when two or more African regional organisations attempt to solve the same security problem in the same country or region.

Institutionalisation

The history of the AU, like that of the RECs, shows that institutionalisation is no guarantee of long-term effectiveness. Instead, it accentuates centralised decision-making mechanisms, bureaucracy, and dependence on international funders. In the case of the G5 Sahel, the many projects that have been placed under its supervision mean that its permanent secretariat now appears too small to fulfil its function. This situation is not unique to the G5 Sahel; most African regional organisations suffer from insufficient staffing for activities that require technical skills and specialised personnel.

The institutionalisation of the G5 Sahel has heightened competition between African regional organisations. This serves as a reminder that these organisations still do not view cooperation and coordination with one another as imperative.

Cooperation

As well as the pressure to institutionalise, another problem with the current institutional cacophony is a distinct lack of cooperation between African regional organisations. Nonetheless, there are instances of cooperation between organisations that maximise their impact by working together to tackle similar issues in neighbouring geographical areas. One example of this is the joint work between ECCAS and ECOWAS, which decided to develop interregional cooperation on maritime insecurity. They adopted a common declaration with the Gulf of Guinea Commission after a joint summit in 2013 in Yaoundé, Cameroon.

This is a long-standing issue. The 2008 “Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation in the Area of Peace and Security Between the African Union, the Regional Economic Communities and the Coordinating Mechanisms of the Regional Standby Brigades of Eastern Africa and Northern Africa” refers to the principles of subsidiarity, comparative advantage, and complementarity. Despite a plethora of texts that define and set out the cooperation between RECs and the AU, there is no agreed joint definition of the three principles. This gives different parties a great deal of discretion in their interpretation of the principles. Applying the principle of subsidiarity between the AU and the RECs/Regional Mechanisms does not always produce a clear division of labour. The AU and the RECs more often rely on the notions of comparative advantage and complementarity, as well as – importantly – a willingness to work together. The situation is the same in interactions between African regional organisations: the signing of regional agreements is often an obstacle course, but the process can accelerate when there are close relationships between these organisations’ executive secretaries.[5]

The most recent examples of cooperation among African regional organisations is the signing in 2013 of an “Agreement Establishing the Framework for Consultation, Cooperation and Partnership between West African Inter-governmental Organisations”. The measure was supported by seven west African regional organisations, including ECOWAS, the Conseil de l’Entente, the LGA, and WAEMU. Bilateral memorandums of understanding have also been signed: for instance, those between the Conseil de l’Entente and ECOWAS in 2016 and 2019; the LGA and WAEMU in 2011; the LGA and ECOWAS in 2013; and the LGA and the G5 Sahel in 2018. The implementation of such agreements is often hampered by a lack of meetings, which hardly facilitates monitoring of the cooperation process. While they are supposed to meet twice a year in the framework of the agreement they signed, the seven west African regional organisations have not done so in the last four years.[6]

Generally, African regional organisations stress that they want to avoid the duplication of efforts and cooperate. ECOWAS and the G5 Sahel signed in July 2018 a memorandum of understanding in which they agreed to cooperate in various areas. However, aside from the Declaration of Intent signed in July 2018, it remains unclear what political backing G5-Sahel will receive from ECOWAS. Some members of ECOWAS still have considerable reservations about the new organisation, as they were not involved in its creation.

Cooperation is strongly dependent on the nature of leadership, personal agendas, and interests at both the national and regional levels. This explains why the recommendation of a 2006 UN Economic Commission for Africa report on “rationalisation” largely failed, despite some efforts to adopt mechanisms to coordinate their activities. In the absence of a clear long-term vision, cooperation develops at the technical level, as it has with the LGA acting as an operating agency to implement WAEMU projects.

Coordination

While poor levels of cooperation are an issue, the more pressing problem is that of coordination: essentially, the way in which organisations covering the same geographic area separately pledge to tackle the same issues. This problem has a long history.

The 2002 AU Constitutive Act underlines the need to coordinate and harmonise policies between existing and future RECs. Following the 2006 UN Economic Commission for Africa report and the 2008 memorandum of understanding discussed above, African regional organisations began to make some efforts to adopt mechanisms to coordinate their activities. In its communiqué of June 2018, the AU reaffirms “the need to further strengthen the coordination of the security effort within the framework of the APSA and to do everything to this end, so that the initiatives of the G5-Sahel Joint Force and the MNJTF, while preserving the flexibility and adaptability that underpin their effectiveness, fit better into the Architecture, in conformity with the relevant PSC decisions”. Setting out the main domains of cooperation, the AU does not specify either a functional or geographic division of labour between the institutions.

The situation ought to prompt African states to, at least, establish coordination mechanisms in the first instance – to understand who is doing what and, in time, agree on a more efficient division of labour based on an assessment of different African regional organisations’ comparative advantage. The absence of clear lines of communication or a hierarchical structure among African regional organisations not only complicates their increasing willingness to take a more proactive role in regional security but also risks confusion, duplication of effort, and the dissipation of energy and resources. The question of coordination is not limited to relationships between African regional organisations’ commissions and secretariats; it also applies to their relationships with external partners. Indeed, as the proliferation of donors’ strategies in the Sahel shows, the lack of internationally accepted definition of the region and the multiplicity of international actors with various agendas complicates coordination between stakeholders at both the European and African levels. In practice, the lack of coordination reveals a lack of a clear agreement on a joint long-term strategy.

The costs of overlapping memberships and mandates

The proliferation of African regional organisations and the expansion of their mandates in peace and security have resulted in overlapping competencies and memberships. This has political, financial, and social costs.

Firstly, many organisations now effectively compete with one another, all of them claiming legitimacy in addressing regional conflicts. For example, ECOWAS, the LGA, the G5 Sahel, and the Conseil de l’Entente cover similar cross-border issues in an overlapping geographical area. Such overlapping mandates and expanding competencies have created duplication of activities in peace and security. This can hamper collective efforts to achieve African regional organisations’ goals. It also adds to the burdens of member states, as a country belonging to two or more organisations not only faces multiple financial obligations, but must cope with different meetings, policy decisions, instruments, procedures, and schedules. The ECCAS treaty states that the Conference of Heads of State should take place every year but, in reality, leaders’ commitments are such that this only occurs once every two or three years. In the intervening periods, important decisions around peace and security issues are delayed. This can also hamper coordination: a joint ECOWAS-ECCAS summit on a common strategy to counter Boko Haram, initially scheduled for October 2015, only happened in July 2018.

Secondly, African regional organisations’ peace and security activities have long faced major financing challenges. With the exception of ECOWAS and WAEMU, which have autonomous financing mechanisms via a community levy, African regional organisations lack financial autonomy. This makes them dependent on donor funding for their operating costs and activities. Large parts of the ECCAS budget are financed by Western donors – led by the EU – as well as by the African Development Bank, which plays a decisive role in setting up and monitoring the activities of the African regional organisation.

None of the G5 is able to raise its own funds to finance the G5 Sahel Joint Force – as Nigeria did for the MNJFT, which benefited from both Nigerian financial contributions and external funding, especially that from the EU. Beyond institutional partnership, the problem for the G5 Sahel Joint Force and the AU is that the latter cannot exercise political control over an operation to which it does not contribute financially. Before 2017, there were several largely failed efforts to reduce the AU’s dependency on foreign funding by increasing yearly contributions from its member states. Such underfunding remains a problem for the organisation. The AU’s inability to restore confidence in its leadership role through financial means is compounded by a pre-existing lack of faith in its capacity. In contrast, the MNJTF is successful partly because it receives political backing from the AU, which channels financial support from the EU to the organisation. Due to shortfalls in funds and other resources, the AU needs to consider how best it can support and contribute resources to these forces, including in planning capacity, human resources, and facilitation.

African regional organisations’ heavy financial dependence on donors could indicate that, at a minimum, their programmes are not really a budgetary priority for their member states – or, more clearly, that there is a lack of sufficient strategic thought as to the financial and political implications of this situation. Meanwhile, European partners want to support regional cooperation but have become increasingly reluctant to do so because they do not want to be dragged into political contests between states within African regional organisations.[7] Europeans avoid giving support directly to African regional organisations as institutions, and instead have engaged in a striking level of external investment in funding regional projects.[8]

Thirdly, African regional organisations’ agendas are mostly driven by the defence of national interests and state sovereignty – largely because political leaders seek control over a given situation. This has costs linked to the fact that African regional organisations evolve in a similar fashion to states and, therefore, share their overriding concern for national security. However, when shaped in this way, security actions tend to focus on ‘hard security’ – quick fixes rather than longer-term thinking. From the populations’ point of view, states use violence and other forms of coercion – including against them – when they should be formulating and implementing peaceful and constructive policies that meet their daily needs. The development of hard security initiatives has not been systematically coordinated with ‘soft security’ measures, such as those for early warning, mediation, and other forms of conflict prevention.

For all these reasons, it is difficult for African regional organisations to gain local credibility: when these organisations deploy troops, they do so essentially to deal with conflicts rooted in African state fragility, in which governments and their challengers principally fight over access to state power. This is all the more problematic given that organisations such as ECOWAS have stated that they want to become “people-centred”, as opposed to “state-centred”. But, rather than eliminating threats, states have treated African regional organisations as mediums for the use of force. This risks contributing to the gradual erosion of the legitimacy of the local state, creating fertile ground for non-state governance and the proliferation of jihadist, criminal, and various other militias. Far from the capital, peripheral zones in many countries in west and central Africa suffer from a lack of public services and have become places harbouring growing frustration, tension, and cross-border conflicts. An increase in the number of African regional organisations has not resulted in fewer instances of violence, as they have not convinced their member states to tackle the root causes of instability.

Forum shopping

The proliferation of African regional organisations also enables forum shopping, whereby political leaders select from overlapping African regional organisations, engaging in ad hoc regional cooperation according to different factors at different times. Political leaders in Africa forum shop to make sure that they can select the best option among overlapping African regional organisations.

For example, ECOWAS previously preferred to cooperate with ECCAS on counter-terrorism. But, under pressure from Nigeria, ECOWAS has gradually changed its position and supported the LCBC. The LCBC has filled the gap by brokering cooperation. The organisation serves as a forum in which its four founding member states (Cameroon, Niger, Nigeria, and Chad) and Benin discuss security and military cooperation

There is a certain ambiguity to this sort of practice, as states embark on cooperating with their neighbours while often not fully trusting each other, especially where different states are involved in the same conflict. Events in the Mano River region in the 1990s showed how the use of armed groups as proxies leads to distrust between governing elites in neighbouring states. These elites’ strategies for cooperation and their apparent lack of confidence in one another may appear to be somewhat contradictory. African regional organisations such as the Accra Initiative take the first step to address such distrust by facilitating regional cooperation via exchanges and discussion between leaders in a region.[9]

Yet rivalry dynamics push some member states to use African regional organisations in which their preferences or status are unchallenged. During the 1990s, serious political problems between ECCAS members undermined their willingness and capacity to pursue regional integration: Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, Burundi, and Rwanda all fought civil wars, while Chad and the Central African Republic were shaken by political crises. Even after the signing of peace agreements, the conflicts between the governments of neighbouring states left behind them a legacy of deep distrust between elites and peoples, hindering the development of strong political and economic ties. As a consequence, ECCAS effectively lay dormant between 1992 and 1998. Since its revival, ECCAS has faced the distrust of many central African leaders, who hesitated to delegate part of their sovereign powers to the organisation. The structure, activities, and character of ECCAS have, therefore, been determined by the wishes and habits of member states – and, in particular, by their presidents – rather than by a truly independent capacity to act on transnational issues. In order to relaunch the regional integration process, the members of ECCAS revised the organisation’s treaty and appointed new members to its commission in July 2020.

Meanwhile, leaders generally try to promote African regional organisations that do not include their cultural, political, or economic rivals.[10] For example, in west and central Africa, there is persistent tension between anglophone and francophone countries. In 2002 CEMAC’s Multinational Force of Central Africa (which is known by its French acronym, FOMAC) was created largely because of its French-speaking dimension and because its member states knew France would provide support for its rollout. The same is true in west Africa, where Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso extricated themselves from the ECOWAS framework by setting up the G5 Sahel. Traditionally, there is high political and bureaucratic tension between anglophone and francophone countries within this framework. And the formation of the G5 Sahel made it easier for francophone countries to benefit from French support.

Distrust and resentment between member states do not necessarily prevent African regional organisations from remaining operative and conducting joint peace operations or mediation. Rivals might still share an interest in stabilising their region and hence engage in multilateral cooperation to attract donors. The G5 Sahel shows that proactive choices made by states to work through a given African regional organisation makes it possible to cooperate according to the particularities of the moment rather than choosing African regional organisations where the members are only linked by a past history. The influence of charismatic regional leaders, leading their country or the African regional organisation, is also important for leveraging African regional organisations, where personalities and interpersonal relations continue to play a critical role.

For now, multiple memberships offer African states the opportunity to pick and choose the organisation that best suits their interests. Overlapping mandates and memberships, while creating the costs examined earlier, also enable forum shopping and make it an attractive option for many leaders. Forum shopping explains why member states retain an interest in maintaining African regional organisations rather than winding them up, as they see them as advantageous. Ultimately, forum shopping is a further aspect of the proliferation of organisations and mandates that should cause international actors to stop and think before they take any action that could further complicate this picture.

Conclusion

In a context in which African regional organisations are rooted in different geographical, historical, economic, and political environments, African states exploit their memberships in order to maximise their interests. As highly dynamic and constantly evolving security challenges do not always fit existing African regional organisations’ geographical scope, the nature of regional cooperation has changed during the last few decades. Many African leaders behave in opportunistic ways, creating new regional arrangements or engaging in security operations through institutions that have no previous record in this area. Not only does the proliferation of African regional organisations show a lack of clear perspective within Africa of the costs and benefits of multiple memberships, it is also at least partly the result of the choices made by the long-standing European donors that fund African regional organisations, or projects under African regional organisations’ aegis.

Ultimately, most European partners remain pragmatic about the proliferation of African regional organisations essentially because these bodies – as multilateral or collective groupings – provide additional channels for enhancing bilateral cooperation with African states. Donors increasingly support the 13 African regional organisations mapped as part of this project on a case-by-case basis only.

External actors play a role in developing and shaping African regional organisations’ geographical scope of action, as well as in political-institutional competition in Africa. They currently have no clear and comprehensive strategy for developing long-term partnerships with, or among, the array of African regional organisations. An important example of this is the G5 Sahel, which the international community has mostly supported in an ad hoc way – without questioning the root causes of national and regional incapacities, or while considering coordination mechanisms only after creating new structures. In this, of course, donors are following African states’ own wishes and choices. But the problems this approach has created should give international donors pause.

This does not mean that there are no success stories among African regional organisations. ECOWAS, now in its forty-first year, has a formidable record in its efforts to enhance regional economic integration, its initial mandate, and its promotion of peace in a particularly turbulent region – as seen in the way it managed the Gambia crisis in 2017. Although it has its critics, the regional level of African governance, including as a layer in the continent’s security architecture, has obvious advantages, such as geographical proximity and good knowledge of local cross-border culture and traditions. But the current way of doing things has two main risks. Firstly, by failing to take account of different organisations’ comparative advantages or to draw on their complementary strengths, African regional organisations and international donors can inadvertently facilitate rent-seeking by African stakeholders. Unless they start to address this failure, they will never bridge the gap between expectations and capacity, regardless of how much external support these organisations receive. And the solutions they seek, in a complex array of institutional assemblages, will become increasingly disconnected from the actual problem: meeting populations’ expectations by reforming governance at the regional level.

To this end, international donors, whether countries or institutions, should pursue a number of recommendations.

- In the first instance, international donors should simply take stock of this proliferation of African regional organisations, which they have helped to create. They should examine the current institutional cacophony and assess whether it has really helped to bring about positive change from their own perspective, from the perspective of states (the supposed benefits of forum shopping should not count on the positive side of the ledger), or from the perspective of populations, whose security should be the prime concern.

- International partners should work to freeze, and then reduce, the number of African regional organisations. A tacit ‘non-proliferation agreement’ among major donors would be a good start, at which point they could begin to reduce or redefine existing regional bodies. Naturally, donors should do so in close cooperation with African partners, while clearly expressing their concerns and taking the opportunity to start a conversation about African regional organisations’ existence, structure, and purpose.

- In this, donors should examine the possibility of fostering greater cooperation between African regional organisations based on their areas of specialisation. In west and central Africa, these organisations could identify priority focus areas. This would allow donors to support African regional organisations according to their competencies and resources instead of the geographical area they cover. Specialised regional institutions in, for example, health or agriculture could lead to a more targeted use of resources. Accordingly, existing African regional organisations that have a security focus could acquire a mandate to specialise in other things, so as to not allow for even more proliferation.

- Finally, international partners and African states should make a distinction between multi-country cooperation and support for regional organisations that have a long-term strategy and are keen to effectively implement regional coordination mechanisms. For African leaders, this means regular joint monitoring and assessment of the coordination mechanism their states have joined, and providing donors with a better understanding of different African regional organisations’ comparative advantages. For donors, this means not simply opting for ad hoc options over more established bodies because the former gives them greater control. In the relatively short term, this should mean that some African regional organisations cease some activities, focusing on the comparative advantages they have identified and allowing other organisations to concentrate on what they do best.

About the author

Amandine Gnanguênon is a visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. She is a political analyst who has held several positions in the French government, think-tanks and advised international organizations. She has formerly worked as a senior adviser consultant for the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung on African collective security mechanisms and for the French Development Agency (AFD) on early-warning systems.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all reviewers for their comments on the paper (Antonin Tisseron, Frank Mattheis, Dimpho Deleglise Motsamai, and Jean-René Cuzon) and the ECFR Africa programme team for their insights (Theo Murphy and Andrew Lebovich). The author is very grateful to Juan Ruitiña and Marlene Riedel for their work on the graphics. Adam Harrison’s editorial work improved the writing greatly, but any errors remain the author’s own.

[1] Stephanie C Hoffman, Overlapping Institutions in the Realm of International Security: The Case of NATO and ESDP 2009, Perspectives on Politics 7, 1: p.46, Hofmann, Stephanie C, 2011. “Why Institutional Overlap Matters: CSDP in the European Security Architecture.” Journal of Common Market Studies 49, 1, p.103.

[2] Interview with donors, June 2020.

[3] Meeting of experts on the rationalisation of regional economic communities (RECs), Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso), 27–31 March 2006, Consultative Meeting of Accra and Lusaka: Consolidated Report; AU Ministerial Meeting on Rationalisation of RECs, Ouagadougou, 27-31 March 2006 – First Conference of African Ministers of Economic Integration (COMAI).

[5] Interview with African diplomat in Brussels, July 2020.

[6] Interview with African regional organisation representative, July 2020.

[7] Interview with donor representative, July 2020.

[8] Interview with a researcher, June 2020.

[9] Interview with researcher, June 2020.

[10] Haftel, Yoram Z. and Hofmann, Stephanie C. 2019, Rivalry and Overlap: Why Regional Economic Organizations Encroach on Security Organizations, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63:9, 2180-2206.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.