Gulf of difference: How Europe can get the Gulf monarchies to pursue peace with Iran

Summary

- The Gulf monarchies face a core dilemma: advancing their security interests through deterrence or through promoting a new diplomatic process.

- The arrival of the Biden administration in Washington, and the perception of US disengagement from the region, offers an opportunity for Europeans to help de-escalate tensions between GCC states and Iran.

- The European interest lies in supporting a return to the Iranian nuclear deal and a regional dialogue between the Gulf monarchies and Iran, an approach that is more likely to promote lasting stability.

- Europeans can support this process by strengthening their own regional security posture and confronting head-on the geopolitical tensions at the heart of regional rivalries.

Introduction

Over the last decade, the Middle East and North Africa region has been dramatically reshaped by tensions between the Gulf monarchies and Iran. These dynamics have had a direct effect on key European interests – the security of land and maritime routes, the unravelling of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and regional crises in Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and the Horn of Africa. They have pushed Europeans to support a much-needed regional security dialogue. But, if Europeans are to play a constructive role in easing tensions in the Gulf, it is imperative that they better understand and respond to the thinking of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, a regional bloc made up of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar. In the past, there has been a tendency in Europe to overlook the complexity of Gulf threat perceptions, which has resulted in the disruption of diplomatic efforts related to Iran, including those on the JCPOA.

This paper assesses the different perceptions and strategic objectives of the Gulf monarchies with regard to Iran. It describes how Europeans – both core groups of European countries and the European Union’s institutions – can use that knowledge to play a more meaningful role in helping the incoming Biden administration resurrect the JCPOA and advance a regional security dialogue.

While regional tensions may seem intractable, there may be an opening for diplomacy. Joe Biden’s stated desire for multilateral negotiations may provide an opportunity for a fresh approach. With Biden’s arrival in the White House, the US is widely expected to back away from confrontation with Iran, re-enter the JCPOA and actively encourage the Gulf monarchies to engage in a regional security dialogue. Over the past year, it has become increasingly clear that GCC hardliners – namely, Saudi Arabia and the UAE – have no interest in an escalation with Iran if they cannot count on the United States to provide meaningful military deterrence. This became evident in 2019, when the US failed to respond to attacks on tankers in Emirati territorial waters and oil infrastructure in Saudi Arabia – attacks that were widely believed to have been perpetrated by Iran. These episodes cemented the perception in the Gulf that the US is disengaging from the region and pushed GCC leaders to consider assuming greater responsibility for managing their own security interests. This included a willingness to consider some new diplomatic channels with Iran.

This paper argues that, given these shifting dynamics, key GCC states may be ready to recalibrate their maximalist approach to Iran, but that a sustainable diplomatic process can only be established if they can rely on international support to safeguard their red lines – namely, that Iran will not encroach on their core security interests. The paper argues that Europeans have the capability to help facilitate this process and that they should proactively work with the Biden administration to encourage the Gulf monarchies to engage in a regional security dialogue, one that will also be essential to reviving the JCPOA. This will have to be accompanied by engagement with, and pressure on, Iran to respond in a similar fashion. There are clearly immense obstacles to this, given deeply entrenched regional divisions, as well as the risk that Europe will be divided in its own approach. Donald Trump could also still exacerbate regional tensions ahead of his departure from office, a dynamic that may harden regional opposition to dialogue with Iran. However, Europeans must do everything they can to support the opportunity for diplomacy that could emerge under Biden. This paper lays out a series of measures that Europeans could now undertake in pursuit of this goal, including more pronounced diplomatic efforts between key regional states and on the Yemen conflict in particular; a reinforced security role; and a push to strengthen much-needed regional confidence-building tracks.

The fundamentals of GCC security perceptions

Watershed events in the region – including the Arab uprisings, the signing of JCPOA, and crises in 2014 and 2017 between Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain on the one side and Qatar on the other – have had a significant impact on the security perceptions of GCC leaders. Nonetheless, the underlying premise of how they assess their security has remained unchanged for decades.[1] Its defining feature is that regional decision-makers view national and regional security through the prism of regime security. In the face of any given challenge – economic, environmental, or societal – their approach is to prevent instability from spreading to the domestic political realm in a way that could challenge the ruling elites’ hold on power.

Accordingly, in the view of GCC leaders, regional and domestic risks and threats often overlap. Having transformed from borderless polities into independent, modern states less than a century ago, GCC countries have extremely strong links with one another. The Gulf monarchies view threats as both domestic and regional at the same time, with direct implications for their own security and stability. The “Iranian threat” is, for example, routinely described by Gulf leaders as both external and internal given Iran’s capacity to exploit sectarian fault-lines by working with the Shia populations of GCC states.

During the twentieth century, Britain and, later, the US provided protection from, and deterrence against, outside threats. This allowed GCC leaders to focus on growing their economies and enhancing security at home.[2] For this reason, the sense of US disengagement – which is more apparent in dwindling political leadership than in actual troop numbers – has changed the security calculus in GCC states.

The GCC monarchies are now struggling with a key dilemma: whether regional security should be underpinned by new deterrence mechanisms or by the establishment of a regional security dialogue based on trust and diplomatic agreements. Deterrence mechanisms are provisions that discourage a regional rival from undertaking hostile action by instilling doubt or fear of the consequences, including the threat of force. The views of the Gulf monarchies are ranged along a spectrum in terms of their attitudes to this dilemma. But their thinking is heavily influenced by the knowledge that there are no precedents in the Gulf of a successful diplomatic and trust-building process that has displaced the central role of deterrence in managing regional security concerns. The GCC, established in 1980 to close ranks against the twin threats then posed by Iraq and Iran, is itself an example of a deterrence mechanism – and its internal workings, which are meant to be underpinned by interconnection and mutual trust, collapsed spectacularly between 2014 and 2017, when Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the UAE initiated a political boycott of, and economic embargo on, Qatar.

The response to this fundamental dilemma differs across the GCC – with countries grouped as ‘Hawks’, ‘Hedgers’, and an ‘Odd One Out’ – and has chiefly been shaped by their respective views of Iran.

The ‘Hawks’

Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the UAE are together now essentially members of an informal sub-GCC alliance and may, at first, appear to share identical security perceptions, based on a strong animosity towards Iran and a common concern about the threat posed by political Islam. But, while there are significant areas of agreement, there are also important differences between them.

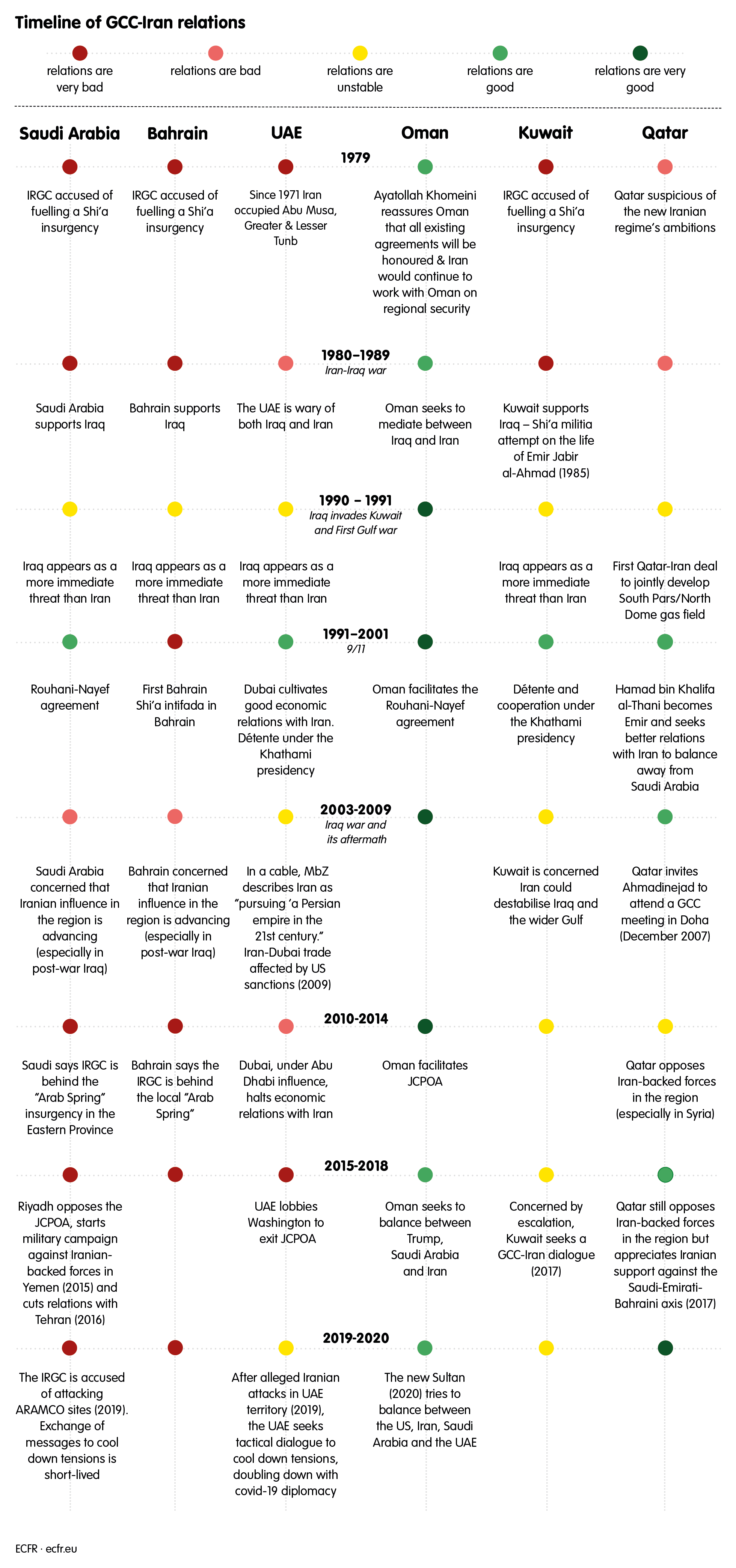

Saudi Arabia and Bahrain are most closely aligned in their hawkish stance on Iran, viewing the country’s policies as both a regional and internal threat. Since 1979, Saudi and Bahraini leaders have described Iran as both a military and ideological threat, accusing Tehran of using its sectarian links to incite unrest in the GCC. This led Saudi Arabia and Bahrain to adopt a confrontational approach to Iran, including by providing support to Saddam Hussein during the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s. There have been only brief interludes from the continuing tensions between Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain.[3] In the mid-1990s, for instance, Hassan Rouhani – Iran’s head of intelligence at the time – signed a security agreement with Saudi Arabia’s then-interior minister, Prince Nayef bin Abdulaziz Saud. Under the terms of the agreement, Iran’s government pledged not to interfere in the domestic affairs of GCC countries, handed over some Saudis accused of terrorism, and suspended its support for foreign groups hostile to GCC leaders. This Rouhani-Nayef “non-interference” agreement, which was renewed in 2001, led to a significant détente between the two countries under Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani while he was president of Iran. This period also saw a reduction in tensions between the Saudi leadership and the Saudi Shia community, which represents around 10 per cent of the kingdom’s overall population but forms a majority in the oil-rich Eastern Province. Indeed, in the late 1990s, Saudi Shia clerics largely led the community away from the occasionally violent confrontations that had occurred in the previous decade and towards non-violent activism, hoping that critical engagement would improve their status as a marginalised group.

However, the Rouhani-Nayef agreement started to unravel as Saudi Arabia grew increasingly concerned about Iranian expansionism in Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein. It finally collapsed after clashes broke out between the Saudi authorities and its Shia community in 2009. Riyadh was convinced that Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) had provided political and financial assistance, as well as logistical and media support, to the protesters. Two years later, Riyadh accused the IRGC of using a radical Shia organisation, Hezbollah al-Hejaz, to turn local Arab uprisings protests into an insurgency. In this sense, for Saudi Arabia, Iran represents the ultimate hybrid threat, both internal and external at the same time.

Since the rise to prominence of Prince Muhammad bin Salman – who has embraced an ultra-hawkish approach to Tehran partly in a bid to rally domestic support around his leadership – tensions have worsened. In 2016 Saudi Arabia executed Saudi Shia cleric and protest leader Nimr al-Nimr and then severed relations with Iran, which it accused of failing to control violence against Saudi diplomatic offices in Iran following the execution. The Saudi leadership also renewed its accusations that Iran was meddling in internal GCC affairs and seeking to incite Shia minorities.

The same dynamics have overshadowed relations between Iran and Bahrain. Between 2008 and 2010, when relations between Bahrain and its local Shia majority population were relatively stable, the two countries began negotiations on border issues and the terms of a potential gas trade agreement. In 2010, Sheikh Khalid bin Ahmad al-Khalifa, Bahrain’s foreign minister and a member of the Sunni ruling family, went so far as to declare that “accusing Tehran of seeking to expand its power and influence in the region” in no way “mirrors … our keenness on the development of bilateral relations” and that his government “totally reject[ed]” the underlying anti-Iranian sentiment. But less than a year later – with the Bahraini regime on the verge of collapse due to a popular uprising led by the country’s Shia majority – officials in Manama accused the IRGC of using local organisations, such as the al-Ashtar Brigades, to destabilise Bahrain and extend Iran’s influence as it had done in Lebanon, Iraq, and Yemen. This shows that Bahrain-Iran relations are a function of those between the regime and the Shia majority in the country. Indeed, the November 2020 appointment of reformist Crown Prince Salman bin Hamad as Bahrain’s prime minister, following the death of anti-Shia hawk Khalifa bin Salman, creates a potential opening in Manama to work on the Shia question both locally and regionally.

Both the Saudi and Bahraini authorities often overstate the extent of external meddling and underestimate the root causes of what are primarily domestic political and economic grievances. Nonetheless, the perception that Iran has tried to exploit those grievances in pursuit of its own agenda is ubiquitous. For Riyadh, meanwhile, there are also crucial regional factors at play. It believes that Tehran threatens its regional sphere of influence and is attempting to encircle the kingdom on two sides: via its Iraqi proxies, such as the Hashd al-Shaabi (Shia-dominated militias also known as the Popular Mobilisation Units), and its Yemeni clients, the Houthis.

For its part, the UAE shares Saudi Arabia’s and Bahrain’s deep concerns over Iran’s regional objectives, but, over the past ten years, it has adopted a variety of tactics on Iran.[4] Having been relatively unscathed by the Arab uprisings, Abu Dhabi developed ambitions to occupy the emerging power vacuums in the region before its rivals could do so. Both grave concerns about Iranian expansionism on the Arabian Peninsula and a desire to expand its own influence prompted the UAE to participate in the Saudi-led war in Yemen after 2015. However, in the UAE worldview, the rivalry with Iran has long sat alongside a simultaneous conflict with an Islamist axis led by Qatar and Turkey. As Abu Dhabi saw Iran weakened by the covid-19 pandemic and international sanctions, the Islamist axis – and Turkey, as its leading actor – emerged as the more important regional threat. Moreover, unlike Riyadh and Manama, Abu Dhabi does not see Tehran as an internal threat – as, historically, there has not been major dissent among the Emirati Shia population, including during the Arab uprisings. Abu Dhabi views Tehran primarily as an external threat, including through the alleged Iranian occupation of the strategically important islands of Abu Musa and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs. These factors have led the UAE to adopt various positions on Iran at different times. While Abu Dhabi’s crown prince, Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan, called for US strikes on Iranian targets as early as 2005 – joining Saudi officials who called for Washington to “cut off the head of the snake” – the UAE has also maintained on-off relations with Iran. Dubai has acted as an important economic conduit for Tehran under the US sanctions regime and its ruler, the UAE prime minister, Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum, made headlines when he took a different position from Abu Dhabi on the JCPOA, publicly welcoming it and declaring: “Iran is our neighbour and we don’t want any problem. Lift their sanctions and everybody will benefit.” However, trade relations between Dubai and Iran were also almost entirely scaled back after 2009, when, having bailed it out from the deep impact of the global financial crisis, Abu Dhabi gained influence over Dubai.

Indeed, geopolitical power in the UAE has since come to rest almost entirely in Abu Dhabi, which, alongside Riyadh and Manama, was strongly opposed to the JCPOA. All three viewed the nuclear deal as likely to grant Tehran financial resources for regional expansion and open a path towards stronger ties between Iran and the West, which they feared would come at their expense. Moreover, all three believed that it was naive to imagine that the JCPOA could become a first step towards encouraging Tehran to engage in further talks on its regional behaviour and ballistic missile programme. As a consequence, they engaged in a powerful lobbying exercise against the deal in Washington between 2015 and 2018. Yousef al-Otaiba – the UAE’s ambassador to the US and one of the best-connected diplomats in town – was a key player in these efforts, which were simultaneously directed at both Democrats and Republicans. This fed Trump’s hostility towards the deal, from which the president withdrew the US in May 2018.

Riyadh, Manama, and Abu Dhabi have long acknowledged that regional talks will eventually be needed to manage relations with Tehran, but they remain opposed to starting negotiations from a perceived position of weakness.[5] For this reason, all three states initially strongly supported Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign, convinced that it could force a weakened Iran to the negotiating table. But they had not factored in the president’s unreliability, which was evident in his failure to back up maximum pressure with effective deterrence for his Gulf allies. The 2019 attacks on oil tankers in Emirati territorial waters and two Saudi Aramco oil installations, and the subsequent lack of a US response, told them that Washington was not willing to shield these states from Iranian aggression. In the absence of such US deterrence, the Hawks swiftly realised the high price they could be forced to pay if a wider military escalation ensued.

In a significant climbdown, Abu Dhabi and, to a lesser extent, Riyadh have subsequently sought a temporary and tactical easing of tensions with Tehran, aimed at ensuring that it does not attack them again. The covid-19 pandemic, combined with the consequences of renewed US economic sanctions on Iran, has also led Abu Dhabi to view the country as weakened and less threatening. This provided an opportunity to expand low-level talks between the UAE and Iran, including sporadic high-level talks. And the UAE also sent medical aid to Iran in response to covid-19. Although more cautious, following the two attacks on the Aramco facilities, Saudi Arabia also reopened some discreet security channels with Iran in order to prevent a wider escalation. At the same time, Riyadh continues to firmly state the need to pressure Tehran to make meaningful compromises on its regional and ballistic missile activities.[6]

These steps remain limited and tactical, and it is clear that they could quickly falter. Despite this, put together, the changing balance of regional security – not least the shifting US role under a Biden administration – could provide a brief opportunity for diplomacy. But, given the perceived threats these three key countries face, specific red lines will need to be guaranteed if the current tactical opening is to be transformed into a more strategic regional shift towards dialogue.

For the Hawks, the principal aim of any regional security talks would be to tackle the perceived Iranian encirclement of the Arabian Peninsula and the threat to the stability of their own regimes – including via its incitement of local Shia populations. Saudi and Bahraini perceptions would significantly change if Iran were to disown Hezbollah al-Hejaz and the al-Ashtar Brigades, and publicly cease its previous (rhetorical) claims of sovereignty over Bahrain. Moreover, while Iran is likely to maintain its influence in Iraq, these states view ending Iran’s encroachment into Yemen as non-negotiable.

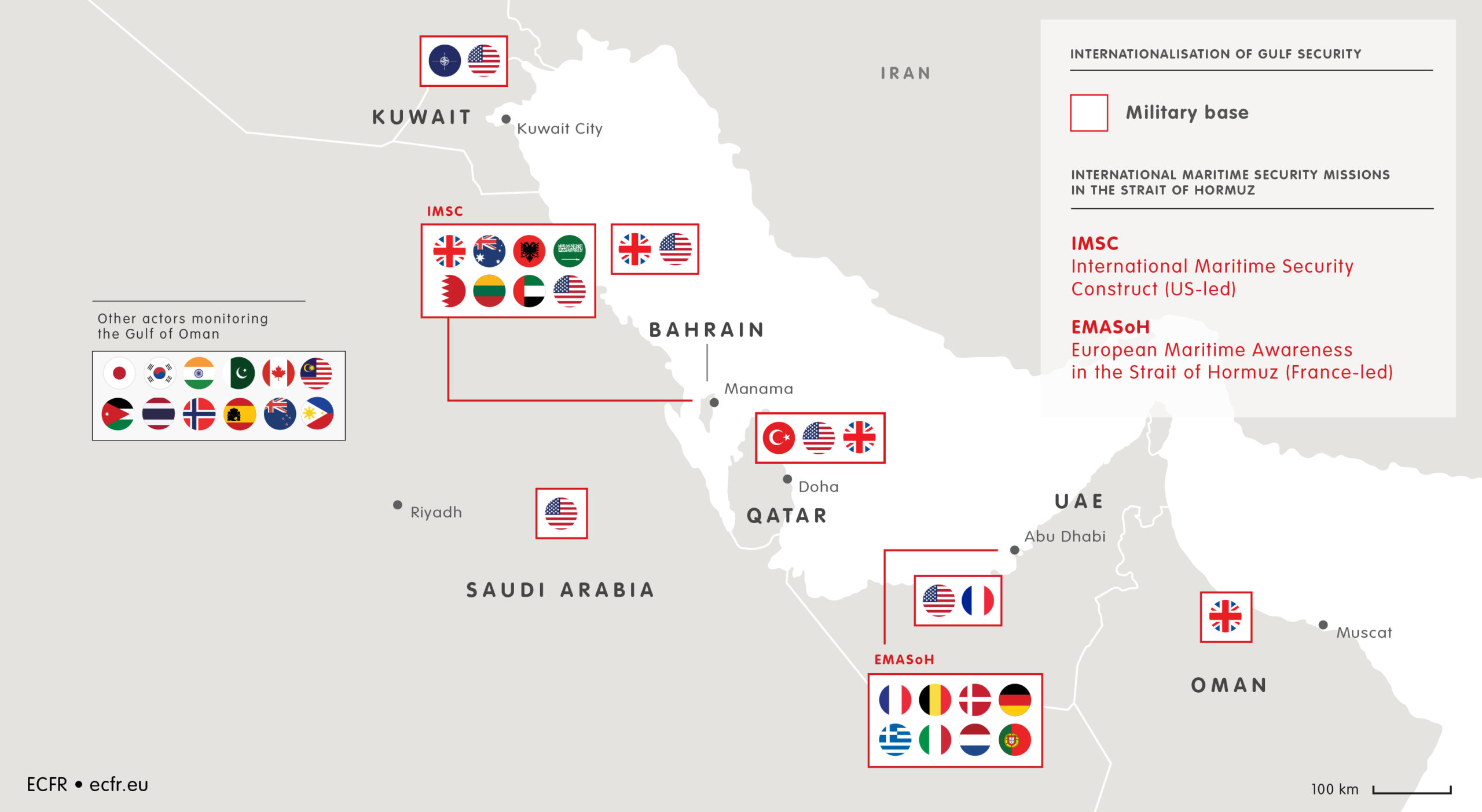

Finally, to feel secure enough to engage with Tehran, the Hawks want reliable security guarantees, which they believe should be provided by global powers. To this end – and given the weakening US commitment to the region – these Gulf states are now seeking to further internationalise their security. Rather than seeking to replace the US, they are looking to create a security mosaic, whereby different international players defend specific areas of Gulf interest, thereby providing the deterrence the monarchies seek. This has meant strengthening security and defence relations with players such as Russia, China, Japan, and South Korea, which each have a stake in Gulf security given their own energy, economic, and infrastructural interests. The Abraham Accords, the recent agreements signed by the UAE and Bahrain to normalise relations with Israel, provide a further option. The deal also aims to signal to Iran (and Turkey) that Gulf states can establish a new regional deterrence axis.

By and large, the Hawks do not regard European countries as active regional security providers, with the partial exception of the United Kingdom and France, which also leads to the maritime security mission European Maritime Awareness in the Strait of Hormuz (EMASoH). However, both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi agree that, at the appropriate time and in the right context, European involvement could have a positive impact on talks with Iran to ease regional tensions, not least because they believe that Europeans have some leverage over Tehran. [7]

The ‘Hedgers’

Kuwait and Oman, the Hedgers, have consistently defined regional de-escalation and depolarisation as strategic priorities to protect their national security. Both countries have diverse social, political, and ethno-sectarian make-ups. And, over the decades, they have developed more inclusive political strategies to preserve regime stability. Both calculate that the best strategy to maintain domestic stability is to hedge between Gulf rivals, diluting the risks they face by balancing engagement with competing regional actors. Both view Iran pragmatically, as a manageable risk rather than an existential threat. However, they have had to adjust this approach due to pressure to scale back their ties with Iran coming from the Hawks and the Trump administration, all of which are critical to their strategic and economic interests.

Part of the reason why the Hedgers view Iran differently is that they do not see domestic Shia communities as posing a direct threat to their internal stability. The sizeable Shia communities in Kuwait – which constitute around 30 per cent of the population and are predominantly found in the merchant class – have traditionally supported the royal family, including during Arab uprisings. There are a few notable exceptions – in 2015, the authorities uncovered a network of Shia militiamen storing weapons in a farm. However, insurgent groups such as this one have always existed on the fringes, alienated by mainstream and elite Shi’ites. Nonetheless, a spate of terrorist attacks in Kuwait in the early 1980s, including a Shia extremist group’s attempt to assassinate Emir Jaber al-Sabah in 1985; the targeting of Kuwaiti shipping during the Iran-Iraq war; and Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 all had a major impact on Kuwaiti security thinking. Together, they cemented the idea that regional tensions could easily spill over into the country, with devastating consequences. Kuwait, therefore, sees regional stability as a key ingredient to its own stability. [8]

The founder of modern Oman, the late Sultan Qaboos bin Said al-Said, similarly developed a political strategy to hold together a socially and politically diverse country. He also benefited from the support of both Iran under the shah and the UK in quelling rival power centres such as the Imamate – in the country’s interior – and the Dhofar Liberation Movement, across the border with Yemen. Iran’s friendly relations with Oman have outlasted the shah, with the sultanate facilitating Iranian-US talks and even the Rouhani-Nayef agreement. Muscat has long believed that building cooperative relations with larger and more powerful neighbours is vital to prevent political polarisation from transferring into Oman itself. [9]

Over the past decade, Kuwait and Oman have seen preventing regional escalation, especially in neighbouring Iraq and Yemen, as a key priority. In this sense, they acknowledge the need to place checks on Iran’s regional behaviour – but also, to a certain extent, on Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Since 2017, both Kuwait and Oman have also developed fears that they would be given the “Qatar treatment” – a political boycott and an economic embargo – if they did not align with the Saudi-Emirati front.

Officials from both Kuwait and Oman define reducing the ability of neighbouring states to exploit their vulnerabilities as a non-negotiable security interest. In the case of Oman, that vulnerability is now magnified by the state’s deep financial crisis, with Muscat worried that major loans from regional players will come with political strings attached. Kuwait’s concerns are linked to the uncertain outlook of its increasingly contentious domestic politics, with the country’s parliament vulnerable to political interference by other regional players. Both countries are navigating these challenges with new leaders who are struggling to fill the shoes of their hugely respected predecessors.

Both countries have indicated that they want to maintain their hedging strategies, and would ideally like to lock regional neighbours into an institutional security framework based on dialogue rather than deterrence. Oman and Kuwait view the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) as a model that could apply to the Gulf, underpinned by a non-aggression pact between its members. While both countries have discreetly explored this option in the past – in 2017, Kuwait sent a letter to Tehran asking for a GCC-Iran dialogue – they have been wary of pushing for it since the Qatar crisis, out of fear of alienating Saudi Arabia and the UAE. They now favour confidence-building measures in non-political areas such as the economy, environmentalism, the fight against covid-19, and youth and education issues.

Both Kuwait and, especially, Oman supported the JCPOA and would back a US return to the original agreement. Their key demands are for the process to be sustainable and for them to avoid repercussions for their stance. In this sense, the backlash Oman suffered for facilitating the original JCPOA provides a cautionary tale for both. Oman was not only unable to benefit as a re-export hub for goods coming from, and going to, Iran under the JCPOA, but it also found itself cornered by its hawkish neighbours and the Trump administration. Kuwait and Oman do not want to repeat this experience. They will want enhanced international support if they are to back US re-entry into the deal.

In this context, the Hedgers would welcome the involvement of external players as facilitators and guarantors. They would, however, want to ensure that any such involvement did not bring with it the baggage of various geopolitical rivalries, which could inadvertently heighten, rather than ease, tensions.

The ‘Odd One Out’

Among GCC members, Qatar is the Odd One Out.[10] Like Oman and Kuwait, Qatar long pursued hedging between powerful neighbours as its main strategy. However, it was unprepared for the hostile stance that Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, and Manama adopted towards it in 2017 – and it was further shocked that the US initially appeared to support this approach. This provoked a Qatari strategic turn. Turkey emerged as an essential partner, and it now deploys thousands of troops to Doha. Iran also became a more important partner, allowing the use of its territory to enable Qatar to continue to import and export goods. For Qatar, the most salient threat now comes from the Saudi-Emirati axis.

The Qataris’ immediate concern in 2017 was that Saudi and UAE hostility – including the threat of military intervention and attempts to engineer an internal coup – would turn the population against the young, recently enthroned Emir, Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani. But the fact that this did not happen confirmed to Qatar’s rulers what they had sensed during the Arab uprisings, when local dissent was almost non-existent: that threats to their regime could only come from the outside.

Doha has long viewed regional security in terms of the existence of a balance of power with no single hegemonic force. Qatar has long believed it could find sufficient space to hedge between the key players to maintain an autonomous domestic and regional policy and protect its prosperity. In this context, and thanks to the absence of internal dissent threatening the regime, Qatar sees Iran as a manageable risk, not an existential threat. Relations between the two are most often described as “pragmatic” and “a temporary marriage of convenience”.[11] Qatar regarded the JCPOA positively and would welcome a JCPOA 2.0 or a US return to the agreement and a follow-on regional security dialogue.

Given the continuing toxicity of relations with its neighbours, Doha sees the presence of Turkish and Western military bases on its soil as a necessary deterrent and, therefore, a non-negotiable security interest. But Qatar has also drawn the lesson from the 2017 crisis that strengthening its international relations, and cultivating its image as a responsible diplomatic actor that abides by the norms of a rules-based international order, are both essential if it is to retain the favour of reliable global partners. While Qatar was disappointed that Europeans’ support did not lead to a de-escalation of the crisis, it appreciated their refusal to join the Saudi-Emirati camp in 2017. Doha has also invested a great deal of energy in enhancing its relations with the US in general and the Democratic Party in particular.

In this context, Qatar now sees supporting a regional security dialogue under a European and US umbrella as both strategically valuable and politically convenient. The bottom line in maintaining Doha’s support will be to establish a framework that is transparent and does not turn into an anti-Turkey front, given Ankara’s role as a key strategic ally. Qatar is most likely to oppose a GCC-Iran dialogue if it sees this as a route towards building an anti-Turkish alliance.

How Europe can promote a GCC-backed regional security dialogue

Guiding principles

Drawing on this analysis, an effective European strategy to win Gulf buy-in for diplomacy with Iran will require pragmatically navigating intra-GCC differences and engaging head-on with the hard security issues driving their respective positions.

Qatar, Kuwait, and Oman are supportive of a regional dialogue with Iran, albeit while acknowledging the need for Iran to halt its disruptive regional activities. Among the Hawks, the UAE is showing new flexibility given its sense of a US retrenchment and the risks that any escalation could pose to the Emirates. Bahrain, for its part, sits within the Saudi-Emirati orbit and can be expected to follow their lead. It is Saudi Arabia, more than any other GCC state, that still has the most significant reservations about a regional security process involving Iran. Recent comments by King Salman underline the Saudis’ degree of concern and their unwillingness to accept outreach that does not involve Iran pre-emptively addressing its regional activities and ballistic missile programme. Suggestions that the Saudi crown prince and the Israeli prime minister recently met to discuss Iran may be a sign that the kingdom is still considering options to disrupt a new attempt at outreach to Iran.

Neither the US nor Europe can ignore Saudi concerns if they are to revive the JCPOA in a sustainable fashion and achieve meaningful regional stability. As such, and knowing that any dialogue is likely doomed without Riyadh’s buy-in, Europeans must now step up their efforts to encourage it to more seriously consider this regional security process. Such outreach will need to stress that, together with a reinvigorated JCPOA, this is the best way to address the kingdom’s security needs, given that the maximum pressure campaign has only resulted in a more aggressive Iranian stance and direct targeting of Saudi interests over the past four years. This will require Europeans to both acknowledge Saudi concerns and suggest concrete steps to help mitigate the risks of Iranian regional expansionism.

But Europeans should also frame this as a means for Riyadh to begin to recover from its currently precarious political position in the West. Following a series of aggressive moves – including the war in Yemen, the alleged kidnapping of the Lebanese prime minister, Saad Hariri, and the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi – Prince Muhammad bin Salman has become something of an international pariah. Both the US and European countries have pulled back from their embrace of the kingdom. And, given the wider unease with Saudi policies within the Democratic Party, Biden’s victory is likely to accelerate this trend. Europeans should use this to actively press the kingdom to engage constructively on a regional security process, if Iran can be persuaded to adopt the same approach.

At this stage, it will be essential to lessen the reliance on those deterrence-based Gulf security models that are currently under consideration in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi. GCC leaders routinely define Gulf security as an international problem and are actively inviting global powers to pitch in to protect critical maritime routes and infrastructure. This approach has been hastened by the sense of American disengagement from the region. However, internationalising the military balance in the Gulf will be detrimental to European interests. On the one hand, Gulf states do not consider Europeans to be primary security providers. Internationalisation would, therefore, further marginalise European states, to the benefit of Russia and China. Moreover, the willingness of these external players to invest in Gulf security measures remains overstated – not least because Russia and China both maintain good ties with Iran and are unlikely to support a Saudi-led axis regional against it. Ultimately, this path is likely to lead to continued uncertainty and insecurity, and to risk exacerbating regional tensions. While Europeans should seek to demonstrate that they can provide some measure of security guarantees, they should also make the case that the deterrence-based model is no longer viable and that it is in the interests of the Gulf monarchies to rethink their attitude towards a regional security dialogue with Iran.

To enhance their prospects of success, Europeans will also need to recognise that GCC-Iranian relations are only half of the regional security picture. Europeans will need to understand and navigate internal GCC differences over the role of political Islam and Turkey if they are to make progress with Iran. On the one hand, growing Emirati concerns about Turkey’s assertive regional policies – including those in Libya, Syria, and the Horn of Africa – have created the space for the UAE to adopt a more pragmatic approach to Iran, which it now views as a less of a threat. On the other hand, deepening ties between Turkey and both Qatar and Iran could increase hostility towards this axis and make it even more difficult to address tensions between Iran and GCC states. Europeans will need to carefully factor these dynamics into their outreach. This could involve supporting the partial involvement of Turkey in less politicised multilateral discussions on, for instance, soft security topics such as economic and environmental issues. An inclusive approach to Turkey could, at the appropriate time, prevent it from attempting to sabotage these efforts. It could also assuage Qatar’s concerns about a GCC-Iran dialogue being used to isolate its Turkish ally. This limited Turkish participation could also help address Emirati concerns about potential Turkish-Iranian alignment and discourage Saudi Arabia from tactically seeking engagement with Turkey and Qatar against Iran. This may be the dynamic at play in the small bilateral breakthrough reached by Saudi Arabia and Qatar in December 2020, when the countries agreed to a provisional framework and a trial period that could lead to a bilateral detente.

Meanwhile, Europeans should not forget the value of like-minded countries, such as Oman and Kuwait. The Hedgers share many perspectives with the Europeans but fear that Europe does not have sufficient leverage with the UAE, Saudi Arabia, or Iran to begin a credible and sustainable process.[12] Oman and Kuwait are reluctant to lead any diplomatic initiatives, fearing that global powers will not defend them from the resulting regional repercussions. If Europe could give both countries more reliable guarantees related to their main socio-economic and political weaknesses – thereby making them less vulnerable to pressure from their immediate neighbours – they could emerge as more engaged facilitators. Both countries have wider networks inside Iran, Iraq, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE that they could use to assist the process of de-escalation. Crucially, Kuwait has a proven track record of influencing Saudi decision-makers, with the late Emir Sabah having a direct connection to King Salman. Prince Muhammad bin Salman has shown an interest in cultivating a similar relationship with the new Kuwaiti leadership, especially the influential Crown Prince Mishaal al-Ahmad al-Sabah. Oman, meanwhile, remains the only GCC player trusted by Iran despite some adjustments under the new leader, Sultan Haitham bin Tariq, such as the retirement of former foreign minister Yusuf bin Alawi, who was particularly close to his Iranian counterparts.

Any attempt at a new process will, of course, face a multitude of potential obstacles and spoilers. Domestic politics in Saudi Arabia and Iran will inevitably have an impact on their willingness to engage. It will be inconceivable, for instance, for Prince Muhammad bin Salman to enter into negotiations with Iran should the economic crisis fuelled by covid-19 and the collapse in oil prices trigger a new period of hostility between the Saudi leadership and Saudi Shi’ites in the Eastern Province. Iran’s willingness to make concessions to the Saudis as part of a regional dialogue will also depend on its wider relations with the US under the new administration. At the same time, broader regional tensions related to Turkey, as well as the rivalry between Iran and Israel, could easily intrude on any attempted regional dialogue, even one that has US and European support. Europeans need to be aware of the immense challenges such a process would face – which explain the deeply entrenched nature of the conflict – but they should see shifting regional conditions and the US election as creating an opening to advance the kind of a Gulf security process that is needed to stabilise the region.

Operationalising a European strategy

A regional security process in the Gulf is the only sustainable way forward to defuse the entrenched tensions that have, over the past ten years, damaged vital European interests. These interests include: the security of critical land and maritime routes; the stability of the global energy market; the implementation of the JCPOA; and the resolution of several regional crises in Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and the Horn of Africa.

Europeans come to the table with some baggage. At times, GCC leaders perceive the EU and key member states as being biased in favour of Iran, due to their efforts to save the JCPOA. GCC leaders also see Europeans as disunited and lacking a meaningful regional security role. But Europeans are in a better place to play a meaningful role than other global players – such as Russia or China, which are still widely mistrusted. Diplomatic gravity and the ability to play the honest broker will be essential in attempting to ease Gulf tensions. On this basis, Europe should now seek to leverage Gulf monarchies’ concerns about the regional security situation and the diminishing US role to secure their support for renewed diplomacy with Iran. Europe’s engagement will primarily be diplomatic, but it should include an enhanced security role. This focus could involve increased engagement on maritime security by expanding the EMASoH mission. Alongside this, Europeans should embrace their support for regional confidence-building measures, in a bid to clear the way to multilateral talks on soft security issues. Together, these measures should aim to support a process that could lead to a Gulf-wide Rouhani-Nayef agreement – one that, ultimately, regional players themselves would need to own. This process would be based on shared principles governing interstate relations, such as non-interference (either directly or by a local proxy); respect for each state’s territorial integrity; and a commitment to solving disputes without the use of force. It will be a difficult, complicated process but, to pursue this approach, Europeans should take the following steps.

Use the momentum of Biden’s victory

Biden’s election could create new diplomatic momentum given his stated desire to revive the JCPOA and his emphasis on a robust dialogue to help reduce regional tensions. Europeans should quickly forge a shared understanding with the Biden administration to achieve this goal, knowing that Biden is nonetheless likely to be more immediately focused on domestic challenges.

The transition period will be particularly sensitive, given that Iran hawks in Trump’s inner circle could still increase regional tensions to constrain Biden’s diplomatic options. The November visits to the region by US secretary of state Mike Pompeo, as well as special representative for Iran Elliott Abrams, suggest the Trump administration is seeking to gain regional support from key partners – Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE – to take further coercive measures against Iran before it leaves office. The November assassination of Iranian nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, has also been linked to the sense of ongoing escalation by the departing Trump administration.

While both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi want to avoid all-out escalation, they may be tempted to use this period to strengthen their position, in preparation for future negotiations. Here, there is a real risk that they could miscalculate about Iran’s willingness to respond. Against this backdrop, Europeans should urgently increase diplomatic efforts in a bid to prevent escalation that could seriously compromise a future diplomatic process. Europeans could partly use the momentum generated by international discussions about a post-pandemic economic recovery, which has been the main focus of the Saudi-chaired G20 throughout this year, to emphasise that a regional conflagration would seriously threaten the Gulf’s prospects for future growth and prosperity.

Given the JCPOA’s importance in allaying international proliferation concerns, Europeans will understandably prioritise stabilising the nuclear deal once Biden takes office. Clearly, however, this approach should be accompanied by a strong US and European effort to secure agreement from the Hawks – especially Saudi Arabia – so as not to run the risk that they will act as spoilers. In part, this will be about having a degree of transparency and consultation with these actors in real time, as the US and Europe attempt to stabilise the nuclear agreement. However, it will also be absolutely necessary to make sustained diplomatic efforts on accompanying issues of concern to Gulf monarchies. The E3+1 (Germany, France, the UK, and the EU) need to make a persuasive case that, as soon as all parties have returned to their commitments under the JCPOA, there will be a transatlantic push for Iran to address GCC states’ core concerns on regional security.[13] To this end, Europeans should prepare the ground to bring Iran and GCC countries to the negotiating table. They should avoid cross-vetoes between the regional and future follow-up nuclear talks with Iran going beyond the JCPOA, but the two tracks could have interlinking elements as part of an expanding set of negotiations. This would provide important reassurance to GCC states.

Show European leadership on regional dialogue efforts

This dimension will require an enhanced European effort and a willingness to engage in questions of regional hard security and geopolitics, in relation to not just Gulf monarchies but also Iran, with which key European states maintain open channels of communication. Working closely with the US but taking leadership of the initiative, a European core group – including individual states, as well as the EU – should now engage in increased diplomatic efforts. This could potentially be linked to efforts by the United Nations secretary-general, who can use the mandate given to him by UN Security Council Resolution 598, which ended the Iran-Iraq war, to pursue a regional security dialogue.

In the currently polarised context, crowded multilateral talks would likely be chaotic and ineffective, simply deepening existing fault lines. To overcome these hurdles, including those created by intra-GCC tensions, Europeans will have to steer carefully between various actors. They should first work on a bilateral basis, then facilitate and mediate talks between subgroups of regional countries, and finally move to a wider multilateral process, which could include the GCC as an organisation.

As part of these efforts, Europeans will need to demonstrate to the GCC a clear commitment to pressing Iran to meaningfully engage on these issues. This will be dependent on Tehran seeing a European effort to encourage GCC states to support the JCPOA. But Europeans are well positioned here given their unique dialogue with all key states. They must be willing to use this influence constructively, and should seek to take advantage of the conflict fatigue shared by both Iran and GCC states.

For the GCC, the initial areas of focus in any dialogue with Iran, for the GCC side, would be addressing Gulf states’ fears of Iranian expansionism, especially across the Arabian Peninsula. These concerns would be greatly reduced if Iran were to disown and disenfranchise Hezbollah al-Hejaz and the al-Ashtar Brigades, and to publicly renounce and denounce its previous claims of sovereignty over Bahrain. This should be a focus of European outreach to Iran.

But the war in Yemen, which is a crucial issue for Saudi Arabia, may emerge as a particularly promising area on which to make initial progress. Key regional players are already signalling that they want a solution to the conflict, while Biden has also committed to ending US support for the Saudi war effort. This is an arena in which intensified European diplomatic efforts might be particularly useful, and in which progress could unlock the door to a wider security dialogue. A European core group should seek to use their channels with Iran, possibly in coordination with Oman, to press it to stop supplying weapons to the Houthis and to push the group towards meaningful negotiations. They should accompany this with clear outreach to Saudi Arabia, stressing the need for an inclusive settlement.

Provide more security support to GCC countries

The role of external powers as essential guarantors of Gulf security is embedded in the strategic thinking of the Gulf’s ruling families. With the US commitment increasingly in question, Europeans should look to enhance their own roles. This should not be about replacing the US: this is both impossible, given the constraints on European resources and political willpower, and also undesirable. At the heart of a possible new security architecture is the need for a more pragmatic GCC attitude – one that moves beyond the reliance on a military framework that has fundamentally failed to address their security concerns. The Europeans should encourage the GCC monarchies to start seeing political arrangements as a more effective means to guarantee their security and wider regional stability.

But, for now, it remains unthinkable for Europeans to be credible security interlocutors without increasing their security efforts in the Gulf. Europeans need to demonstrate an enhanced commitment to GCC concerns and a willingness to play a more active role in supporting an emerging security architecture. This effort will clearly need to be led by the UK and France, given their military presence across the region, but other European states could contribute.

As part of this, Europeans should maintain a focus on maritime security. This is an area in which their capabilities are appreciated by GCC countries and is also important to Europe’s commercial and energy interests. The EMASoH mission launched in 2019 offers a template to expand on; it is supported by Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, and Portugal. Uniquely, the EMASoH mission diplomatically engages with countries on both sides of the Gulf, a dynamic that could allow Europeans to advance their diplomatic ambitions. Most GCC monarchies view EMASoH in a positive light. Abu Dhabi and Riyadh believe the presence of European military assets acts as a deterrent to the IRGC, which is wary of provoking escalation with European states. Europeans should consider expanding naval deployments beyond the current two frigates, as well as enhancing capabilities in the field of aerial surveillance, given that drone attacks are a major GCC concern. A strengthened EMASoH would increase the Europeans’ convening power to launch serious maritime security talks between GCC countries and Iran as part of the mission’s diplomatic track. Establishing mutually agreed rules of engagement in the waters of the Gulf would represent an important step towards more complex political negotiations. The dialogue could also evolve to tackle the right of navigation in the territorial waters of contested spaces, such as the islands of Abu Musa and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs.

Beyond maritime issues, Gulf monarchies are also deeply concerned by Iran’s ability to carry out direct attacks on them. This is why they focus on curtailing Iran’s ballistic missiles programme – a very difficult issue to tackle given Iran’s unwillingness to relinquish its missile capabilities in the face of the overwhelmingly superior, Western-supplied military capabilities of its GCC neighbours. Rather than pump more weapons into the region, Europeans should look at non-military means of addressing the GCC’s concerns. They could, for instance, assist GCC countries in upgrading their cyber defence capabilities against missile and drone attacks.

Support confidence-building measures

Europeans could bolster progress on the political and security tracks through an enhanced focus on softer confidence-building measures, an area in which they have significant experience. Confidence-building measures are no substitute for tackling the knotty geopolitical and security issues at the heart of tensions in the Gulf that, if unresolved, block any other form of dialogue. However, confidence-building measures can be a useful complement and are viewed as such in the region. In particular, a structured dialogue guided by specific principles could be an important way to build mutual understanding – a shared analysis, functioning communication channels, and, finally, a consensus – among regional stakeholders on key secondary issues, one that will be necessary to ensuring that any security architecture or system is sustainable.

Responding to the priorities of Kuwait and Oman, Europeans should offer to host regional forums modelled on those held by the OSCE to discuss issues of common concern for Iran and GCC states, including: water security; economic development; drug and human trafficking; piracy; health sector cooperation in light of covid-19; and the environment. These forums could draw on historical precedents such as the Kuwait Regional Convention for Cooperation on the Protection of the Marine Environment from Pollution. This UN-mediated conference – based on a 1978 protocol that operated until 1993 – brought the GCC, Iraq, and Iran together to explore ways to preserve their shared marine ecosystem. European know-how and technical capacity-building in these areas is well regarded in the region and could enhance cooperation. GCC players already work with private and public European entities in related projects, as is evident in the activities of the EU-GCC Clean Energy Network and the EU-GCC Dialogue on Economic Diversification. There are several UN agencies that could support these talks.

Given that they deal with less sensitive topics, these discussions could begin in a wider multilateral framework that involves the likes of Egypt, Iraq, Turkey – and, in the future, Yemen – depending on the issue under discussion. Iraq’s inclusion could help facilitate better relations between the country and the GCC, something that is of great interest to the monarchies.

A special strand of talks would be religious diplomacy. While Europeans should certainly refrain from entering intra-Muslim questions, they could encourage Europe-based religious institutions to expand interfaith dialogues. In this area, both the Vatican and the Church of England – which have functioning communication channels with Iran and the GCC respectively – have a legitimising capacity and a tangible convening power. Pope Francis demonstrated a keen interest in interfaith dialogue when he signed the UAE-mediated Document on Human Fraternity with Sheikh Ahmed el-Tayeb, Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, in Abu Dhabi last year. Interfaith dialogues in general have become much more appealing for Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Oman, and Bahrain, which are competing to demonstrate their disposition towards religious inclusiveness. A Vatican-Canterbury forum would provide a prestigious multilateral setting for Saudi and Iranian clerics to publicly engage and provide mutual recognition. This would build on existing bilateral Hajj channels between them, which have been resilient even at times of formidable political tensions. Such a step would help cool the sectarian discourse that underpins much of the animosity in the Gulf.

Across all these issues, Europeans should continue to support Track 1.5 and Track 2 dialogues – talks among semi-officials and civil society representatives – between Iran and GCC countries, many of them run out of European-based institutions. These conversations will not deliver high-level breakthroughs but can help strengthen important cross-conflict ties and initiatives.

Conclusion

While the last months of the Trump administration may be bumpy, an opening to advance much-needed regional security in the Middle East may emerge once Biden is inaugurated as president. The opening has been created by the realisation in key GCC capitals that continuing US regional disengagement requires new thinking on security issues. If positively channelled, this shift could lead to some overdue pragmatism that helped create a new dialogue with Iran. Europeans should seize this opportunity. Taking advantage of shifting conditions, their own political and security channels, and their access to Tehran, Europeans should look to play a leading role in facilitating a new security dialogue in the Gulf.

About the author

Cinzia Bianco is a visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, where she works on political, security, and economic developments in the Gulf, as well as the region’s relations with Europe. She holds an MA in Middle Eastern Studies from King’s College London and a PhD in Gulf Studies from the University of Exeter. Between 2013 and 2014, Bianco was a research fellow on Sharaka, a European Commission project on EU-GCC relations. Her former publications for ECFR include “A Gulf apart: How Europe can gain influence with the Gulf Cooperation Council.”

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Julien Barnes-Dacey and Ellie Geranmayeh for their intellectual contributions to the paper, Kristian Ulrichsen, and Robert Philpot for his editing. The ideas of many of those who write about de-escalation in the Gulf provided great inspiration, including Christian Koch and Adnan Tabatabai, Tarja Cronberg, and the “Fostering a New Security Architecture in the Middle East” papers. Numerous lengthy exchanges with officials and thinkers in Europe and the Gulf monarchies were crucial in guiding my analysis and policy proposals – I thank you all for your time.

Annex: Timeline

[1] Gregory Gause, “Threats and Threat Perceptions in the Persian Gulf Region”, Middle East Policy 14.2 (2007): 119-124.

[2] Jonathan Fulton and Li-Chen Sim (eds), External Powers and the Gulf Monarchies (London: Routledge, 2018).

[3] Gawdat Bahgat, Anoushiravan Ehteshami, and Neil Quilliam, Security and Bilateral Issues between Iran and its Arab Neighbours (Cambridge: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

[4] Gawdat Bahgat, Anoushiravan Ehteshami, and Neil Quilliam, Security and Bilateral Issues between Iran and its Arab Neighbours (Cambridge: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

[5] Author’s interview with a Saudi strategist focused on Iran, Riyadh, 28 October 2019. Author’s interview with an Emirati official from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, phone interview, 24 August 2020. Author’s interview with a member of the Bahraini Shura Council, London, 24 January 2020.

[6] ECFR in-person interview with senior Saudi official, January 2020.

[7] Author’s interview with a senior Emirati official, Zoom, 14 September 2020.

[8] Author’s in-person interview with a Kuwait government official, Kuwait City, 11 December 2018; author’s interview with a Kuwaiti diplomat, Webex, 28 September 2020.

[9] Author’s telephone interview with an Omani government official and member of the royal family, 31 January 2020; author’s interview with a senior adviser at Oman’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Zoom, 1 September 2020.

[10] David Roberts, Qatar: Securing the Global Ambitions of a City-state (London: Hurst, 2017).

[11] These expressions were often used by several experts participating in the conference “Toward a New Gulf Security Regime: Abandoning Zero-Sum Approaches,” organised by the Gulf Studies Center at Qatar University and Al Jazeera Center for Studies, which took place in Doha on 19 and 20 January 2020.

[12] Author’s telephone interview with a Kuwaiti official at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 24 September 2020; author’s interview with an Omani diplomat posted in Europe, Zoom, 23 September 2020.

[13] Comments by a senior Emirati official during an ECFR event, October 2020.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.