Decade of patience: How China became a power in the Western Balkans

Summary

- China has become the most prominent third actor in the Western Balkans.

- The country’s activities are spread unevenly across the region, but they follow a common approach.

- This approach is marked by China’s wide-ranging efforts to establish itself in key economic areas and to gradually position itself as an indispensable actor.

- China is slowly transforming its interactions with Western Balkans countries in sectors such as culture, media, and politics into long-term and institutionalised relationships.

- As European and US ambivalence towards the Western Balkans persists, the region will be in increasing danger of falling into an endless spiral of competition between various foreign actors.

- Western policymakers should address the widening developmental gap between the region and the EU through initiatives such as targeted investment plans in energy and infrastructure, sectoral integration frameworks, and the frontloading of EU law in the accession process.

Introduction

China’s formalised, seemingly nonchalant, attitude towards the Western Balkans masks a surprising nimbleness and strategic intent. In the past decade, the country has become the most prominent third actor in this part of the European Union’s neighbourhood. There is growing evidence that Beijing is expanding and embedding its presence across the Western Balkans in a variety of sectors, while engaging with an increasing number of local actors. The process appears to be accelerating at a time when there is an emerging Western consensus on the challenges posed by Beijing’s forays into the region.

This newfound wariness of China runs somewhat counter to the country’s public image as a source of huge economic opportunities in an era of geopolitical change. Understandably, most analyses of China’s activities in the Western Balkans focus on economic cooperation with, and investment in, the region in the last decade. Yet Beijing’s wider political, social, and cultural initiatives there deserve a great deal of attention – which they are only now beginning to receive. China is moving onto a new stage of engagement with the Western Balkans, implementing a policy of heightened interaction with various parts of society in numerous policy areas.

This paper argues China is on the cusp of acquiring real leverage over policy choices, political attitudes, and narratives in some parts of the Western Balkans. While it has not defined this endeavour as following an explicit strategy, Beijing has implemented policies designed to establish a significant presence along key land and maritime routes that run deep into Europe.

The paper describes China’s expansive approach to the Western Balkans, which centres on the development of numerous relationships with individuals and institutions (many of them starting from a relatively low base). These relationships – which involve everything from infrastructure and energy to culture, the media, and party politics – are intended to promote Chinese narratives and interests. To this end, Beijing has exploited the geopolitical ambivalence of many Western capitals, grasping the opportunities to invest in strategically important sectors that arise from the persistent development gap between the Western Balkans and the EU, as well as the region’s lack of sustained political and economic convergence with the bloc.

Finally, the paper argues that Chinese leaders have capitalised on a political affinity with elites in captured states. Beijing is creating incentives for cooperation within these insider groups and beyond, with many citizens of Western Balkans countries adopting a transactional mindset as their dreams of European integration fade. This process is gradually leading to the emergence of an economic and political ecosystem in which China and Western Balkans countries have significant shared interests.

Key areas of cooperation

Beijing has long worked to build coalitions of convenience with ruling governments and dominant parties in the Western Balkans, often by signing direct agreements with them that are subject to little parliamentary scrutiny. Such governmental and party cooperation occurs at the bilateral and multilateral levels, mostly through frameworks of the 17+1 – a China-led cooperation format that includes a range of central and eastern European countries – such as the China-CEEC Political Parties’ Dialogue and the China-CEEC Young Political Leaders’ Forum. China also takes part in the World Political Parties’ Dialogue, as part of the Chinese Communist Party’s efforts to complement interstate cooperation with that based on ideological affinity.[1]

Yet the collapse of personalist Western Balkans regimes such as that in Montenegro has forced China to quickly diversify its party ties.[2] This process of diversification is also evident in states such as Bosnia and Herzegovina – where it is facilitated by the country’s constitutional structure, which ensures parity between the three constituent entities. Similarly, Beijing has reportedly made party cooperation a component of its relationship with the prime minister of North Macedonia, Zoran Zaev.[3]

China’s extension of these ties is part of a long-term trend. For instance, party-driven cooperation between the Montenegrin Democratic Party of Socialists and the Chinese Communist Party dates back to 2010. Serbia and China included a party cooperation dimension in the strategic partnership they concluded in 2009. And such interactions are increasing even in Kosovo: despite China’s non-recognition of the country as an independent state, the sides have maintained an informal relationship in Pristina and at the United Nations. As part of this, Kosovo appears to have implicitly refused to recognise Taiwan’s independence, likely in a bid to gain diplomatic capital with China.[4] And the head of China’s representative office in Pristina has gradually raised his public profile.[5] China has also attempted to increase its presence in Kosovo by bidding – unsuccessfully – to build a coal-fired power plant there and to sell Huawei equipment to the main Kosovo telecoms company.

There has also been an uptick in China’s administrative and institutional cooperation with Western Balkans countries in the past decade. Traditionally, while the EU has been intent on legal and institutional harmonisation with these countries in relation to the accession process, China has focused on practical cooperation with ministries, state agencies, and companies involved in infrastructure, energy, and finance.[6] Such Chinese engagement involves exchanges of state visits, signings of memorandums of understanding, study trips, and Chinese companies’ initiatives in the region. It involves the exploration of opportunities for joint projects and the creation of personal and institutional relationships rather than the synchronisation of policies, practices, or approaches. Yet China is now expanding its formal and informal cooperation with municipalities across the region, building on the 17+1 and the work of local Chinese embassies.[7]

Cultural power

Beijing has an increasingly expansive, structured approach to using culture as a diplomatic tool in the Western Balkans. While it has always had a role in Chinese diplomacy to some extent, culture long played second fiddle to economic power – but Beijing is working to change this. As a consequence, Chinese culture is gaining public prominence across the region. This is apparent in, for instance, celebrations of the Chinese new year, which have traditionally been held on embassy premises in rather exclusive gatherings for local elites.[8] In 2019 the Chinese embassy in the Albanian capital, Tirana, organised open-air celebrations in the city’s main square, with festivities and exhibitions lasting for two weeks. The Chinese ambassador used the occasion to declare that China would fund the construction of a new urban bus terminal in the city.

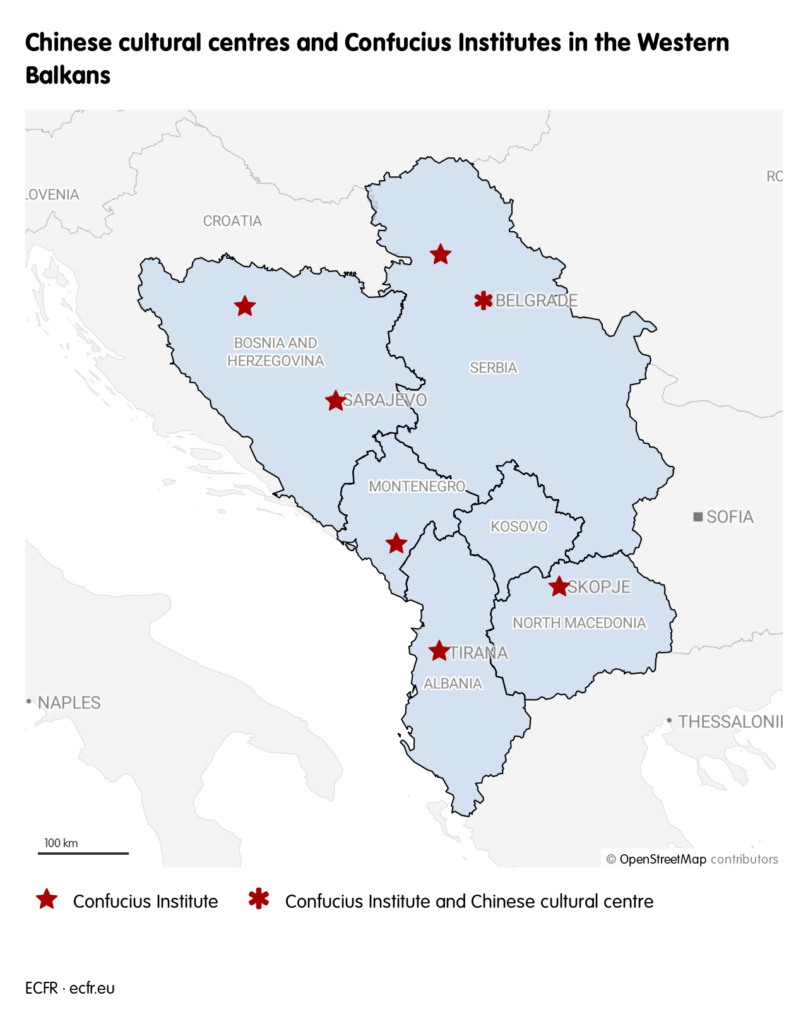

Meanwhile, Beijing is also diversifying its cultural diplomacy. It is doing so by complementing its traditionally language-focused Confucius Institutes – whose operations have been subject to rising criticism in many countries – with other institutions. This initiative centres on the establishment of Chinese cultural centres, which have a much wider portfolio of activities and focus on cultural interaction and cooperation – mainly focusing on the arts, including literature, photography, essay competitions, book readings, concerts, exhibitions, and even cookery classes. What is expected to be the largest such centre, in Belgrade, is on the verge of completion and scheduled to become fully functional this year. It is being built on the symbolically important site of the Chinese embassy that NATO bombed in 1999, killing three Chinese journalists. China plans to create a similar institution in Tirana in the coming years, having established others in south-eastern European capitals such as Sofia, Athens, and Bucharest.

Interestingly, culture also plays a growing role in Chinese tourism in the Western Balkans. For example, the 1972 film ‘Walter Defends Sarajevo’ is very popular with older audiences in China, as it was one of the very few shown during the Cultural Revolution. At present, the film is a major diplomatic reference point in bilateral relations and a magnet for Chinese tourists, drawing thousands each year (prior to the pandemic).

This has contributed to the marked increase in Chinese tourism in the Western Balkans in the few last years, which is quite evenly spread across the region. Such tourism is quickly becoming a key area of interaction in China’s bilateral relationships with countries in the region, as local economies seek to benefit from the spill-over effects of the rapid growth of the Chinese middle class. The process has been facilitated by Western Balkans governments’ removal of visa requirements for Chinese citizens.

China is paying greater attention to culture in the media content it generates and promotes in the region, such as the various supplements it publishes in newspapers in countries such as Serbia, Bulgaria, and Croatia.[9] A similar trend is apparent in the social media presence and the online activities of China Radio International, which covers the arts, lifestyle, and cuisine.[10]

Beijing promotes Chinese culture within the 17+1, often through a centre in Skopje. While China and Western Balkans countries still engage in relatively few cultural exchanges and joint events, the 17+1’s activities in this area have expanded – primarily due to the work of numerous Chinese institutions, making this a lop-sided form of cooperation.[11]

Control of the media narrative

The last few years have seen a marked rise in China’s media presence across the Western Balkans. The country features in a growing number of news stories and other programmes in the region. For instance, between 2016 and 2019, the number of stories related to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) published in Albania jumped from 42 to 194. These stories mostly consist of information that is factual, neutral in tone, and orientated towards economic issues, but they generally lack critical evaluations of China’s activities.[12] Moreover, they present China as a friendly economic power that is open to cooperation and capable of providing financial and other opportunities. Importantly, governments in the region appear to act as allies of Beijing in this information policy, often amplifying such messages or even informally seeking to control published content.[13]

The various agreements that the Chinese government signs with its counterparts in the Western Balkans rarely receive negative coverage in regional media outlets. And these outlets often appear to avoid references to information about questionable conditions attached to Chinese projects. The imperative of economic development in countries with limited media freedom allows governments in the region to control the flow of content on China and bilateral relations with the country.

Meanwhile, Beijing is gradually increasing its direct involvement in content generation via various cooperation agreements with state news agencies and individual outlets.[14] The Chinese authorities supply information and content to a growing number of publications and media sites, often as supplements or news sections.[15] Chinese state cooperation with local journalists is now a well-established mechanism of interaction, one that particularly focuses on pro-Beijing reporters and authors. Following study visits to China, such journalists routinely receive approaches from the Chinese authorities to write positive stories about their experiences.[16] Some freelance for local Chinese embassies and participate in various projects sponsored by Beijing.

Chinese ambassadors are also gradually increasing their engagement with journalists in the region.[17] In some south-eastern European countries such as Croatia, there have even been attempts to directly acquire a major media group and numerous radio stations.[18] Beijing is developing media formats in which it can cooperate with its local partners to generate and place content, increasingly that on lifestyle, culture, and cuisine. One example of this is the Belt and Road News Network, part of the BRI.

In line with developments in other parts of the world, Chinese diplomats and media outlets are rapidly increasing their presence in Western Balkans social media networks, with ambassadors setting up Facebook and Twitter accounts to disseminate official messages. In countries such as North Macedonia, individual Chinese diplomats have taken the even more ambitious approach of creating their own webpages and accounts to promote content that is very critical of the West.[19] While this is not quite as forceful as the “wolf warrior” Chinese diplomacy that has irritated many Western governments during the pandemic, it is a forceful method of public positioning nonetheless.

Beijing is not yet capable of consistently and coherently disseminating its own narratives in the Western Balkans. But there is little doubt that it is rapidly taking up positions in the media landscape that help it cast its actions in a favourable light.

Academic and interpersonal relations

Academic and interpersonal links between China and the Western Balkans countries are also growing. This is typified by the increasing range and intensity of interaction between national academies of sciences, which build on a legacy of cooperation from previous decades. For instance, the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts recently signed an extensive agreement with its Chinese counterpart. Platforms such as Confucius Institutes and Sinology departments in state universities are gradually complementing their activities – sometimes through quite innovative practices.[20] For instance, the Confucius Institute at the University of Banja Luka in Bosnia is expanding into research and teaching (including degree courses) on China-related subjects. The managers of the institute regularly visit secondary schools to spark an interest in Sinology among students.[21]

Chinese academics are taking up long-term assignments in Bosnia and seeking to launch research projects there. More broadly, private universities in south-eastern Europe are starting to develop significant institutional relationships with their Chinese counterparts. One example of this is the University of Donja Gorica in Montenegro, which hosts numerous lecturers from China, runs MA courses on subjects related to the country, and even has a Chinese-language version of its website. The founders of the university are reportedly close to the president, Milo Dukanovic, who is widely known for his friendly approach to China.

A similar type of cooperation is in the works in Croatia, where the Zagreb School of Business is starting various cooperation projects with China.[22] And the Chinese authorities are inviting a growing number of citizens of Western Balkans countries who studied in China to develop their ties to Chinese academia after completing their courses. Some of these students have retained teaching positions in China, while others have participated in various projects as consultants – mostly on issues such as regional history and politics, and project development. A few of them have developed new programmes and research projects in universities in the region.

In the last couple of years, Chinese universities and research centres have rapidly developed their expertise on countries in south-eastern and central Europe. There are now 23 such university departments and other structures in China, while the country has set up 30 other centres focused on particular states in the region in the last decade or so. The Beijing-supported China-CEE Institute, based in Budapest, is becoming an increasingly important hub for research and analysis. The institute helps integrate pro-Beijing experts into the academic, research, and analytical communities.

Infrastructure ambitions

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, China gained a degree of influence over the maritime infrastructure of south-eastern Europe by taking control of the Greek port of Piraeus. The resulting public discourse on the land corridor running from the port to central and western Europe has tended to overshadow Beijing’s activities in the Balkans. Yet Chinese efforts to gain control of ports in the region and create adjacent industrial zones date back to the late 2000s. For instance, in Albania, this initiative initially centred on the port of Durres.[23] Since then, China has focused on Vlore – despite facing various political setbacks, most of them created by Albania’s accession to NATO.

Beijing has continued its efforts to strengthen its position along the Adriatic coast, both bilaterally and in the 17+1. In line with this, a Chinese consortium bid in 2020 to construct a new terminal at the Croatian port of Rijeka. Years earlier, Chinese firm Luxury Real Estate Company acquired a stake in the Croatian port of Zadar. China is currently constructing railway links that run through Croatia, other countries on the Adriatic, and central European states. This initiative is likely to accelerate as relations between Zagreb and Beijing improve in the coming years.[24]

These port projects are also linked to China’s other infrastructure investments in the Western Balkans, such as those in railways and roads in North Macedonia, and in industrial zones across the region.[25] Some Chinese companies are already purchasing land near the railway network in the expectation of future investment.[26] For instance, the previous VMRO-DPME government in North Macedonia had plans to establish special offshore zones with Chinese involvement – but they did not come to fruition.[27] Similarly, China has developed an interest in the Montenegrin town of Bar, in anticipation of the construction of the Bar-Boljare highway.[28]

If governments in the Western Balkans are unable to pay Chinese loans for such projects, they could be contractually obliged to transfer ownership of various ports and land assets to Beijing. This would provide China with some real leverage in the region.[29] For example, China could build on its cooperation with Montenegro at the port of Bar by capitalising on the growing financial difficulties of the facility’s owners, which could lead to a handover.

Chinese companies have even considered bidding for infrastructure projects in Kosovo, despite these bids’ very low chances of success.[30] Beijing’s highway projects in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and its long-standing interest in building railways, are another indication of the expansiveness of Chinese infrastructure ambitions in the region. For almost a decade, China has been working to gain a foothold along the Adriatic coast (even if these efforts have largely gone unnoticed). Some Western Balkans states’ NATO membership and strong ties to the United States complicate these ambitions, but China has shown an impressive focus on the task and may persist with it.

Investment, trade, and dependency

In all, China is gradually increasing its involvement in Western Balkans economies – albeit from a low baseline. Persistent development gaps between the region and the EU are bound to create further opportunities for Beijing in the coming decade. Nonetheless, China’s economic footprint in the Western Balkans remains relatively small, with the country accounting for roughly 6 per cent of regional trade. Yet China is slowly establishing a presence in key areas of national economies – energy, infrastructure, and finance.

While most Western Balkans states have manageable debts, China accounts for a rising share of these liabilities – roughly 15 per cent in Serbia and Bosnia, more than 20 per cent in North Macedonia, and more than 40 per cent in Montenegro. Indeed, Montenegro has already become a textbook example of debt-trap diplomacy, with its debts amounting to an excruciatingly high 80 per cent of GDP. The structural importance of Chinese loans in Montenegro will become evident later this year, when the country is due to make repayments on them. Beijing will be in a position to make pivotal decisions on the financial fate of the country due to the fiscal catastrophe resulting from the covid-19 epidemic.[31]

China could apply this newfound leverage in various ways, given that Montenegro may be contractually obliged to cede control of strategically important assets. And it could be in a similar position in other countries in the region. The Albanian government has partially renegotiated the monopoly on international flights held by the Chinese owner of Tirana airport but, in the process, extended the company’s concession contract while allowing it to have a role in shaping national air transport policy. In Bosnia, a consortium led by China Gezhouba Group Company has begun a major expansion of the country’s largest power plant, in Tuzla.

China is expanding its economic presence in Serbia in a range of areas, thereby creating new opportunities for leverage. This effort is becoming structurally important through Chinese involvement in sectors such as energy and infrastructure. Another such area is the labour market, as Chinese owners purchase or invest in large companies such as steel conglomerate Smederevo and Linglong tyre factory (which have around 5,000 and 2,000 employees respectively). Furthermore, Huawei has become an integral player in Serbia’s technology and innovation sector, particularly digital infrastructure and telecoms.

Crucially, China’s bid for influence in the Western Balkans is as much a function of collaboration with key economic players and networks in the region – most often via intergovernmental relations and opaque contracts – as it is of lending, investment, and trade. Together, these relationships can create dependencies through which China gains ad hoc and, increasingly, systemic influence. Some of the agreements at the centre of the relationships contain various jurisdictional and legal traps. For instance, the application of, and arbitrage under, Chinese law or compensation mechanisms can lead to the transfer of property and other assets to Beijing.

How China embeds its influence in the region

China has predominantly conducted its Western Balkans policy of entry and engagement at the intergovernmental level, focusing on the highest-ranking actors in national governance systems. In its economic endeavours, Beijing has focused on ambitious, large-scale projects aimed at the core of countries’ economies. Yet, there is growing evidence that China is also taking a much more nuanced, multi-level approach to the region.

One underappreciated element of China’s strategy in the region is its granularity, seen in Beijing’s attempts to weave its influence into the fabric of institutional and social life. Examples of this abound. In Tirana, the state film archive received a much-needed donation of temperature and moisture control equipment from the Chinese embassy, as part of a bilateral cooperation agreement with China’s national film archive. After a fire ravaged the Skopje offices of North Macedonia’s state news agency, MIA, the local Chinese ambassador called the organisation to offer substantial financial assistance for renovating and refurbishing the premises.[32] The children’s choir of the Chinese city of Wuxi donated 42,000 masks to Sarajevo after writing to the chairman of the presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Efforts of this kind help China create pro-Beijing media content, which it supplies to both high-level actors such as state news agencies and much smaller media outlets.[33]

There is evidence that China increasingly plays a mediating role in south-eastern Europe through structures such as the Chinese Southeast European Business Association, which has established somewhat opaque relationships with institutions in the region. Comparable organisations engage with media outlets across the Western Balkans, including by supplying content and pushing for coverage that casts China in a favourable light.[34] For example, the BRI centres spreading across the region – albeit unevenly – are gradually becoming hubs for research, academic cooperation, content generation, and publicity and media engagement. Their versatility allows them to operate at various levels of society, the economy, and politics, and to reach a range of audiences.

As part of its multilayered approach, China has partially refocused on central government structures. It targets subnational governance and administrative institutions, seeking to utilise bilateral and multilateral formats, mostly 17+1 cooperation. For instance, Tirana and Beijing have been twinned since 2016, with five other cities in Albania developing such ties. Another example is the burgeoning relationship between Sarajevo and Shanghai, evidenced by the latter’s donation of medical supplies to the former during the early stages of the pandemic. Notably, such cooperation extends beyond what some might call ‘gesture politics’ to investment projects. There is clear complementarity between China’s steps to develop relations with central and local governments, and with high-level institutions and much smaller social, cultural, and media entities. This versatile engagement could create allegiances and networks across the entire range of state institutions and non-state societal and economic actors.

Networks of influence

The networks of personal and institutional relations that embed Chinese influence in the Western Balkans do not yet appear to form a fully integrated whole. But, as discussed, the country is using this multidirectional approach to sustain its interactions with various communities and institutions. One part of the network is the numerous lines of contact running through Chinese structures and local academic and research communities. This involves China’s cooperation agreements with local institutions; the creation of new academic programmes; regular exchanges of personnel; joint research projects; the commissioning of analyses on areas such as economics and politics at the individual and institutional levels; the establishment of new teaching positions; and other initiatives.

Another network runs from Chinese academic and research institutions to various media outlets, providing a way to legitimise information and present it to a wide audience. For example, in Bosnia, a China-supported organisation headed by former journalists places BRI content in local media outlets.[35]

Yet the overwhelming majority of China-Western Balkans cooperation involves state institutions. This can be seen in their synchronised production of content on various projects and activities, which they present as mutually beneficial. Such content is characterised by positive representations of China and often incomplete information on the initiatives in question. As part of this, governments in the Western Balkans have reportedly intervened in media organisations to prevent the disclosure of problematic information to the public.[36] Such practices help explain widespread public misperceptions of the merits of Chinese loans and investments.

Meanwhile, the link between Chinese content generators and local media organisations is becoming stronger through various mechanisms. One is the extensive agreements between entities such as Xinhua and local state news agencies, which supply China-related content to clients across the region. Another is the content that Chinese embassies and pro-Beijing intermediaries, such as BRI centres, produce to promote projects and relay to the public via a range of outlets. Another still is the content agreements between China Radio International and major media organisations in the Western Balkans.[37]

Such networks, which have varying functions across the region, are growing in number. In Bosnia, for instance, there is already a significant degree of coordination between various China-related actors – a local Confucius Institute, a BRI centre, academics, and journalists.[38] This illustrates the flexibility of these arrangements and the dynamics created by the numerous bilateral and multilateral frameworks that China appears to have spent several years carefully creating. As the country’s efforts in these areas generate various types of incentives for local actors, they are gaining momentum in what may prove to be a self-sustaining manner.

An ecosystem of shared interests

China’s interactions with individuals and institutions in the Western Balkans seem to be designed to create an ecosystem of shared interests. Importantly, this type of engagement goes far beyond ad hoc encounters, has clear long-term aims, and is becoming an established feature of the region’s public discourse and political environment.

The ecosystem has three main parts. The first consists of legacy contacts and relationships, many of which date back to the cold war. In some cases, these networks are explicitly linked to fading memories of European communism. In others, China simply has a desire to cooperate with, broadly speaking, centre-left local actors. Such interactions could seem to imply a degree of ideological affinity between the parties, but this affinity functions as a convenient opening rather than a requirement.

The second part of the ecosystem comprises institutional partnerships and alliances spread across a multitude of state structures. This engagement involves a wide range of bilateral and multilateral cooperation formats, activities, and projects. As these initiatives develop, an increasing number of actors are engaging with them. This capacity to draw in a range of actors explains why China’s administrative and institutional cooperation efforts focus on ministries, agencies, regional and local governments, and state-owned companies, particularly those involved in infrastructure, energy, and economics. Such engagement is predominantly transactional and often results from official arrangements such as trade and investment deals, but it can spill over into regular, expansive commitments and actions – as seen in China’s continued cooperation with high-ranking officials and politicians after they have left office.[39] For instance, former Serbian president Tomislav Nikolic has been appointed as honorary president of the China-Serbia Economy Association.

The third part of the ecosystem has the potential to grow significantly in the coming years. It is a somewhat fluid network of new actors who have an increasing interest in engagement with China. They include students who have returned to the Western Balkans from China and are beginning their careers; freelancers; members of the Chinese diaspora; owners and managers of private media outlets; and entrepreneurs seeking business opportunities in the country. These actors are often self-organised but, at times, receive support from Chinese institutions. Such engagement with China is largely unaffected by changes in interstate interactions of the kind that could result from, for instance, EU accession negotiations.

As discussed, China’s involvement in the Western Balkans increasingly seems to have a self-reinforcing dynamic. Local actors’ engagement with the country is now maturing based on a clear structure of varying, wide-ranging incentives linked to status, career opportunities, and material gains. These incentives partially stem from direct interactions with Chinese institutions, organisations, and firms. Yet many are more diffuse and abstract, based on perceptions about how China’s development creates opportunities for cooperation and growth. For example, such motivations are quite prevalent among small and medium-sized Western Balkans companies, which flock to trade fairs for this purpose.

The responsibilities of power

The expansion of China’s networks in the Western Balkans is gradually affecting policies, practices, and developments in societies across the region. The country is becoming involved in the domestic affairs of some states, as its initiatives there begin to bear fruit. As will become clear in the coming years, Western Balkans countries will inevitably have to engage with China in a growing range of areas. This is nothing new for China, which has created a similar dynamic in regions such as south-east Asia, south Asia, and Africa.

Still, Western Balkans states could be among the first European countries to encounter the dilemmas of deep dependency on China. One such dilemma involves Montenegro’s repayments of a Chinese loan for the construction of the first section of the Bar-Boljare motorway, which are widely expected to have begun by summer 2021. This coincides with a period of intense financial difficulty for a country that is under pressure from both a slump in tourism and the broader economic decline precipitated by the pandemic. Montenegro’s position of weakness provides China with real leverage over it – leverage that could have enormous political, economic, social, and developmental consequences in the long term.

Similar examples of such dependency on China, albeit of a lesser order, are emerging across the region. One such case relates to the persistent and ever more visible protests in the Serbian cities of Smederevo and Bor, which were sparked by environmental problems linked to Chinese companies. So far, the impact of the demonstrations has been offset by a mixture of official interventions to reduce media coverage, some remedial action by the companies’ owners, and state institutions’ efforts to nudge the firms to make improvements.[40]

In this new reality, Beijing has various ways to manage these entanglements and make use of its leverage over Western Balkans countries. One is to adopt an accommodating posture, as it has when various other states have had difficulty repaying loans. In doing so, Beijing can make a range of political, policy, and financial requests behind closed doors. A second option is to use its cooperative networks to minimise negative responses to its activities. A third is to make tactical retreats that allow it to maintain the speed, timing, and scope of its plans for penetrating a country’s economy (as discussed, there is some evidence that China has taken this approach in Serbia). Another alternative is to adopt a more aggressive posture, in an effort to corner governments and raise the stakes of cooperation.

All these approaches are made easier by China’s growing influence in the region’s media outlets, which helps the country receive greater – and often more friendly – coverage. In all, there is increasing pressure on China to manage problems caused by its growing economic and political weight in the Western Balkans. The days in which the country can remain inconspicuous are coming to an end.

An increasingly high-profile actor

China’s entry into the Western Balkans has involved a seemingly contradictory mixture of spectacular, high-profile economic projects and inconspicuous diplomacy. The country attempts to cultivate an image of itself as a humble, helpful, and benign global power that acts with subtlety for cultural reasons, not out of ill intent. Governments in the region have accommodated Beijing in this – becoming accustomed to its opaque schemes, eager to benefit politically from its large-scale projects, and cooperative in its effort to conceal the significant financial and legal problems created by such initiatives. The Western Balkans’ state-dominated media outlets have often promoted an image of frictionless cooperation, trade, and investment between the sides, downplaying any problems and uncertainties in their countries’ bilateral relationships with China.

Yet this dynamic is slowly changing, due to a variety of factors. One is the increase in international scrutiny of the Western Balkans created by intensifying geopolitical competition and the region’s gradual integration with the EU and NATO. The Western Balkans is quickly becoming the ‘near abroad’ that the EU can no longer ignore or take for granted. Given the growing instability to the bloc’s south and east, and Turkey’s apparent lack of interest in integration with the West, the region could be uncomfortably close to becoming a kind of permanent buffer zone.

Secondly, the tensions and apparent inconsistencies in EU policy on issues such as 5G, environmental standards, and economic governance are affecting China’s role in the Western Balkans. Such inconsistencies often result from the EU’s geopolitical ambivalence, as states in the region navigate global powers’ divergent sets of standards, laws, and practices, seeking to strike a balance in cooperating with all of them.

Thirdly, despite Western Balkans governments’ efforts to shield Chinese companies and projects from public scrutiny, the activities of these firms are becoming a source of public discontent. As discussed, this can be seen in relation to environmental concerns in Serbia and highway construction in Montenegro. In the latter case, the public reaction could become increasingly negative if the new government in Podgorica fulfils its promise to publish the contract for the project, whose legal and financial parameters may favour China.

Fourthly, as China expands its influence in the Western Balkans, Chinese actors will be forced to face various consequences and contain crises resulting from their initiatives there. Beijing may not be nimble and responsive enough to continue to strengthen its position and preserve its inconspicuous role. So far, its record is rather mixed. For instance, the Chinese owner of the Smederevo plant has resolved only some of the environmental issues, apparently relying on Serbian state institutions for cover.[41] A similar dynamic is evident in Bosnia in relation to the Tuzla power plant.[42] If Chinese actors persist with such an approach, this will only lead to greater scrutiny and exposure of their activities.

Fifthly, EU policy is affecting China’s role in the Western Balkans. For instance, as the bloc gradually changes its approach to accession negotiations, efforts to identify and address problematic Chinese practices in the region will gradually enter the public domain.

A strategy in all but name

In the past decade or so, there have been many reasons to believe that the expansion of Chinese activity in the Western Balkans is not part of a coherent strategy but a side-effect of European and US ambivalence towards the region. Western European countries have been relatively reluctant to interact with key Western Balkans states, and have tended to view even the 17+1 cooperation framework as a mere diplomatic, political, and administrative convenience. Yet there is much to suggest that China’s actions form part of a greater structure – one that is coherent and that moves in a specific direction.

Beijing’s attentiveness to coastal infrastructure in the Western Balkans is clearly an extension of its global strategy, as shown by Chinese projects in parts of the world such as Gwadar in Pakistan and Hambantota in Sri Lanka. While its initiatives in the Western Balkans are not quite ‘a string of pearls’, they reflect a clear intent to establish a strategic foothold in coastal areas.

By joining NATO, states in the region have complicated rather than blocked China’s execution of its plans. The prospect that some of these countries will join the EU only gives China further reasons to gain leverage over them. This is particularly true in an environment in which the political and legal fluidity of the EU accession process creates numerous openings for Chinese actors. China might not be hostile to EU accession as a matter of declared policy, but it is certainly making the most of the continuous delays to the process – as reflected in its attitude towards environmental and labour standards, as well as economic governance.

Beijing’s approach to the region is partly shaped by its positioning within multilateral organisations. In a way, China is playing a political numbers game in Western Balkans countries, aiming to secure their backing in these institutions. This approach has helped China expand its foreign policy cooperation with Western Balkans countries at the United Nations, and on topics such as Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and the South China Sea.

The timeline of Chinese activities in the region also indicates strategic intent. As discussed, in little more than a decade of engagement with the Western Balkans, China has established a presence in a variety of sectors and positioned itself to do so in many others; expanded its embassies and given them a more prominent role; developed and made use of its expertise on local affairs; engaged in cooperation with a range of actors other than legacy contacts, politicians, and officials; and disseminated its narratives in an increasingly systematic fashion.

Arguably, these activities centre on what one might call ‘the rule of mandates’. In this approach, Beijing initially defines a policy goal that incentivises various Chinese entities to act. It then generates a framework of action without necessarily detailing the range of initiatives that this could include. In a sense, China may have no explicit strategy on the Western Balkans, but there is ever less doubt that it is pursuing the same approach across region – treating it as a single space of strategic intent in a manner that aligns with its global policy goals.

Obstacles to cooperation with China

China may have made significant progress in expanding its role in the Western Balkans, but it will continue to face a number of challenges of varying intensity and predictability. One is the growing international scrutiny of the region created by intensifying geopolitical competition and the rising cost of inaction for the EU and the US. This is reflected in not only research and analysis on the region but also the political dialogue between Western Balkans governments and their European and US counterparts – a trend that is certain to persist in the coming years.

Secondly, there are major cultural and behavioural differences between Chinese actors and their contacts in the Western Balkans. These differences may prevent deep and sustained interaction between the sides, ensuring that they largely cooperate with one another in a transactional manner.[43] This is less of an issue in interstate cooperation – such as that on commerce and trade – but it could play a role in other areas.

Thirdly, Western Balkans countries’ integration into Euro-Atlantic organisations could reshape the terrain on which they engage in bilateral cooperation with China. NATO accession is particularly relevant in this sense, as it has restricted China’s opportunities to cooperate with these countries in areas such as strategic infrastructure, security and defence, and digital communications. This can be seen in developments around the introduction of 5G in Albania, Montenegro, and even Serbia to some extent. If anything, Western pressure on these states to avoid Chinese technology will increase in the coming years.

Negotiations on EU accession will also increasingly affect relations with China. If the EU frontloads its legal provisions in the process of harmonisation with candidate countries, this has the potential to seriously affect their ties with China in areas such as labour, environmental, technological, and other standards; economic governance; and fiscal sustainability and transparency. The accession process could also energise civil society organisations – many of which are quite involved in it – to push back against Beijing. And some EU member states are likely to insist that the accession process take account of China’s role in the region.

Meanwhile, as discussed, many citizens of Western Balkans states are becoming increasingly resistant to interaction with China. The resulting protests against Chinese actors remain local, and are subject to intense pressure from nervous governments. Yet they combine with rather diffuse public frustration with China, whose economic projects in the region have not involved greenfield investments in new factories. In the eyes of many citizens, cooperation with China remains an elite affair that has only limited benefits for society as a whole.[44]

The covid-19 pandemic may have also had a negative impact on Western Balkans citizens’ perceptions of China. The country has focused on projecting an image of itself as a rising global power, a land of economic opportunity, and a proponent of mutually beneficial cooperation, both bilaterally and across the globe. Yet, in its response to the pandemic, Beijing may have inadvertently created a counter-narrative that emphasises Chinese exceptionalism, spurred by widespread theories about the emergence of the coronavirus and its Orwellian techniques for containing the crisis.

A new phase of engagement

The initial phase of China’s entry into the Western Balkans has come to an end: the country is now becoming ever more structurally important to the region. In several cases, Beijing is on the cusp of establishing real leverage over Western Balkans states. Crucially, China has expanded its presence in the region subtly but at an impressive speed. As discussed, while it may not have an explicit strategy on the Western Balkans, China has developed a consistent approach to engaging with countries there. Admittedly, this display of strategic intent does not produce uniform outcomes – due to historical and geographical issues, as well as the attitudes of local elites – but it has a clear direction of travel. In all, China’s presence in the Western Balkans is no longer a novelty but a source of real influence.

Policy recommendations

Western policymakers’ first response to these challenges should be to map them out and to try to anticipate how China will develop its activities in the Western Balkans. The EU and NATO could go some way towards addressing this through regular, well-structured, and comprehensive monitoring and analysis of Chinese activity in the region.

Mind the developmental gap

The development gap between the Western Balkans and the EU is not an abstract concern but a genuine problem. So is Western policymakers’ ambivalence towards the region. While this gap emerged largely due to local deficiencies in governance, repeated delays to the accession process and the lack of a realistic road map for convergence between the region and the EU will continue to create openings for third actors. And these shortfalls will encourage Western Balkans governments to adopt a purely transactional approach to foreign policy, in which they grasp every economic opportunity regardless of how it affects the integration into the EU of the region’s economies and societies.

From this perspective, Western policy has left these governments in a kind of limbo. The EU, NATO, and their member states should identify the key areas in which they can provide support and otherwise intervene to narrow this gap. Furthermore, they should work to understand this persistent gap, and to integrate it into political action in the region.

Close the development gap

While Western policymakers are beginning to pay more attention to the Western Balkans, they have not yet settled on a clear and firm course of geopolitical action in the region. They are seemingly blasé about the issue, still convinced that time is on their side. They seem to be considering whether to muster the will and stamina required to integrate the Western Balkans into the Euro-Atlantic alliance or to turn the region into a new buffer zone. Yet the latter course of action might not be enough to reverse the region’s political accomplishments or change its cultural identity.

Western inaction, at times verging on nonchalance, will continue to create openings for strategically minded external actors. The Western world is no longer entirely the master of its own destiny – in the sense that these actors increasingly influence other players, institutions, and strategies. To help close the development gap in the Western Balkans, the EU will need to implement targeted investment plans in core areas such as infrastructure and energy; deeply integrate the region’s economies into the EU’s; frontload EU law in accession talks; and design sectoral integration networks such as the energy community.

Gain public support

In a century in which the balance of geopolitical power is shifting eastwards, Western policymakers’ ambivalence towards the Balkans is prompting states in the region to look for alternatives to their European and US partners. Cooperation with outside actors such as China seems to offer these countries a bright future in which they are no longer caught in limbo. In response, the EU should attempt to gain public support in the Western Balkans by establishing a common sense of belonging. They can do so through initiatives such as those to reinvigorate and deepen academic and research cooperation, cultural assistance, diplomacy, and media support programmes with countries in the region.

About the author

Vladimir Shopov is a visiting policy fellow at ECFR. He has a wide range of experience as a policy adviser to Bulgarian ministers and institutions, and as a diplomat during the country’s EU accession negotiations. Shopov has provided consultancy and research services to numerous Western companies in a range of fields. He has been a guest lecturer at European and Asian policy institutes and universities, and is currently an adjunct professor at Sofia University. Shopov has engaged in project work with various policy institutes in areas of Asian affairs, EU studies, soft security, and EU conditionality.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the more than 90 experts, analysts, and politicians from the Balkans who were kind enough to take the time to share their views and opinions on China’s footprint there.

[1] Conversations in Tirana and Belgrade, September and October 2020.

[2] Conversations in Podgorica, September 2020.

[3] Conversations in Skopje, September 2020.

[4] Conversations in Pristina, February 2020.

[5] Conversations in Pristina, November 2020.

[6] Conversations in Belgrade, Podgorica, and Sarajevo, September and October 2020.

[7] Conversations in Tirana and Sarajevo, September and October 2020.

[8] Conversations in Sarajevo, October 2020.

[9] Conversations in Belgrade, Sofia, and Zagreb, October and November 2020.

[10] Conversations in Skopje and Sofia, September and November 2020.

[11] Conversations in Skopje, September 2020.

[12] Conversations in Belgrade, October 2020.

[13] Conversations in Skopje and Belgrade, September and October 2020.

[14] Conversations in Belgrade, October 2020.

[15] Conversations in Sarajevo, October 2020.

[16] Conversations in Tirana and Podgorica, September 2020.

[17] Conversations in Sarajevo and Podgorica, September and October 2020.

[18] Conversations in Zagreb, October 2020.

[19] Conversations in Skopje, September 2020.

[20] Conversations in Belgrade and Sarajevo, October 2020.

[21] Conversations in Sarajevo, October 2020.

[22] Conversations in Zagreb, October 2020.

[23] Conversations in Tirana, September 2020.

[24] Conversations in Zagreb, October 2020.

[25] Conversations in Skopje, February and September 2020.

[26] Conversations in Skopje, September 2020.

[27] Conversations in Skopje, February and September 2020.

[28] Conversations in Podgorica, September 2020.

[29] Conversations in Podgorica, March and September 2020.

[30] Conversations in Pristina, February and November 2020.

[31] Conversations in Podgorica, September 2020.

[32] Conversations in Skopje, September 2020.

[33] Conversations in Belgrade, October 2020.

[34] Conversations in Zagreb, October 2020.

[35] Conversations in Sarajevo, October 2020.

[36] Conversations in Belgrade, October 2020.

[37] Conversations in Sarajevo, Zagreb, and Sofia, October and November 2020.

[38] Conversations in Sarajevo, October 2020.

[39] Conversations in Belgrade, October 2020.

[40] Conversations in Belgrade, October 2020.

[41] Conversations in Belgrade, October 2020.

[42] Conversations in Sarajevo, October 2020.

[43] Conversations in Skopje, September 2020.

[44] Conversations in Skopje, February and September 2020.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.