Bordering on crisis: Europe, Africa, and a new approach to crisis management

Summary

• A humanitarian catastrophe is emerging to Europe’s south, just as the United States seems set to reduce its international engagement.

• Distracted by other conflicts and alarmed at migration flows, the main focus of European strategy for Africa appears to be ‘containment’. But adopting a “security belt” approach will not resolve emerging problems, let alone long-term underlying issues.

• Strengthening European civilian crisis management mechanisms and mediating recurrent conflicts can help manage the sources of disorder in west Africa, the Sahel, and the Horn of Africa.

• Supporting the African Union and United Nations will be critical to achieving this; particular effort and resource should go towards helping UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres fix what he has called a “broke and failing” system.

• Taking early steps to tackle humanitarian crises is a chance to show the EU has not entirely lost a sense of strategic purpose and that it is able to meet moral and political imperatives to address human suffering.

Policy recommendations

• Launching a ‘Fighting Fund’ and ‘Pioneer Group’ for Humanitarian Diplomacy in 2017

• Boost mediation and political resources in CSDP missions and along the African “security belt”

• Plan for ‘post-peacekeeping’ scenarios

• Open regional prevention centres

• Work with the UN to build up African civilian capacities

• Give Guterres flexible resources for prevention

Introduction

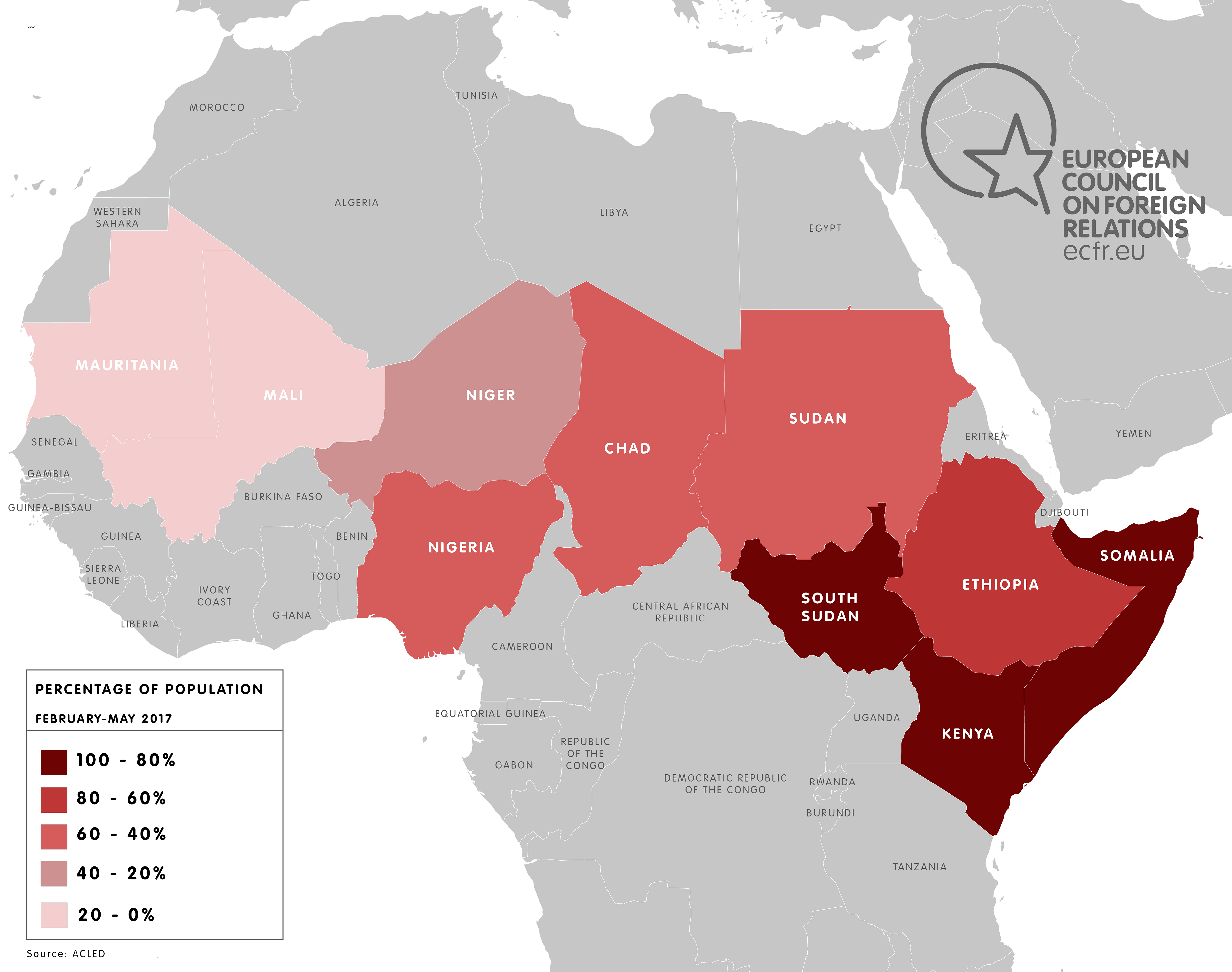

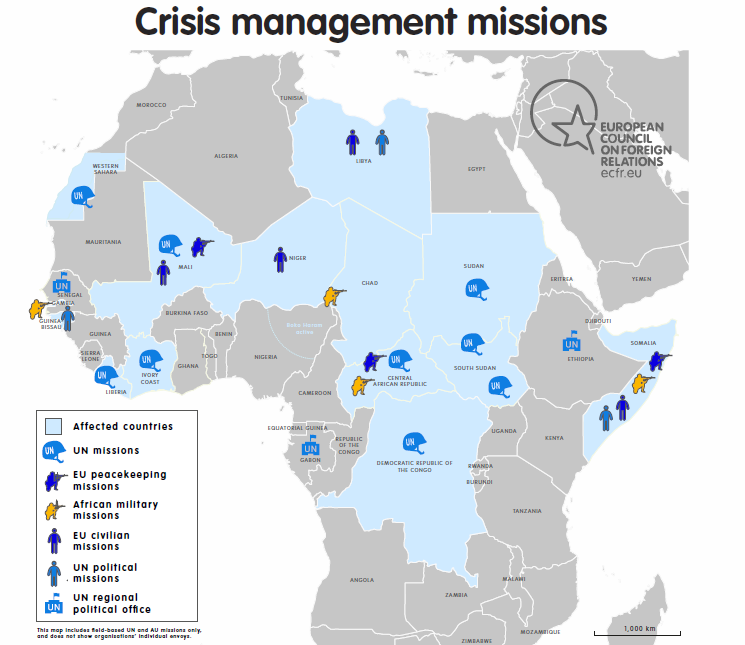

Fresh trouble is brewing on Europe’s southern flank. Surges in migration and the spread of jihadi groups such as Boko Haram and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb in recent years have made European strategists nervous about instability in the Sahel and Horn of Africa. Germany, the Netherlands, and Nordic countries have sent peacekeepers to Mali. French commandos are tracking down jihadis across the Sahel. British troops are serving with the United Nations in South Sudan. European Union missions are training Malian and Somali soldiers and Nigerien police officers, while EU-flagged ships patrol the Mediterranean and the coast around the Horn of Africa looking for human traffickers and pirates. European governments and institutions have ploughed funds into UN agencies and looked to cut deals with African governments to stem migratory flows across the Sahara. Yet serious violence persists from Nigeria to the Sudans, fuelling a humanitarian crisis that threatens to create more instability on Europe’s borders.

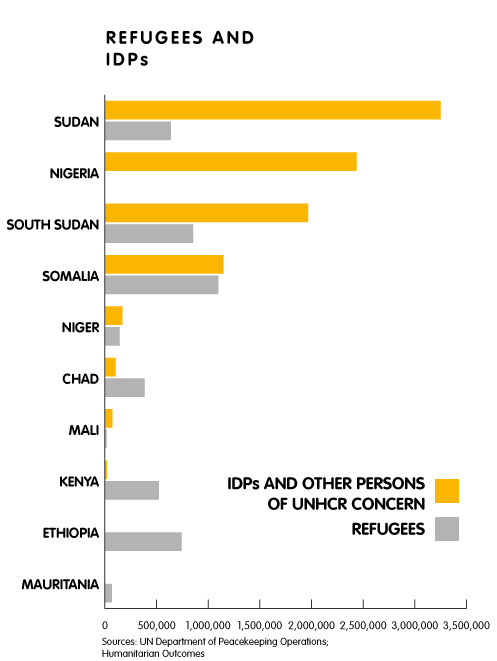

UN officials have warned that northern Nigeria, South Sudan, and Somalia are all on the brink of famine.[1] A combined total of 25 million people need help in these three countries and the UN estimates that it requires $4.4 billion to deal with these immediate challenges and the parallel threat of famine in Yemen. The citizens of these countries are being displaced in numbers comparable to the mass flight from Syria, with two million internally displaced persons in northern Nigeria and over three million in South Sudan. Two million Somalis are either displaced inside the country or living in neighbouring countries.

If the humanitarian situation in one or more of these countries deteriorates in the short or medium term, the chances of large numbers of new refugees and migrants looking for ways to Europe will be high. The odds that recent EU efforts to bolster regional mechanisms will be able to handle the flow are uncertain. Even if human flows can be controlled, international donors will need to dig deep to find additional cash to address these four crises. As of mid-April, the UN had received only one-fifth of the funds it needs to manage them.[2]

The UN, already overstretched by the crisis in Syria, has been asking for record sums of around $20 billion a year to cover humanitarian needs.[3] Before he became secretary-general in late 2016, Antonio Guterres described the organisation’s relief efforts as “broke and failing”.[4] The UN’s latest calls for more money have, however, coincided with a series of threats from the new American administration to cut its contributions to multilateral activities by half or more. While this proposal has to be approved by Congress, it would create vast funding gaps for some of the biggest UN agencies that rely most heavily on aid from the United States. Washington gave a combined total of nearly $3.5 billion to the World Food Programme (WFP) and UN refugee agency (UNHCR) in 2016, representing about a third of the total budget. The EU institutions and Germany, the biggest individual European donor, gave about $1.2 billion each to the two institutions combined. Although EU members could fill the funding gap in theory, doing so would create financial and political strains for them at home. The EU’s high representative, Federica Mogherini, has warned that if the projected US cuts go through “certain regions of the world would get completely destabilised.”[5]

In sum, Europe faces a humanitarian catastrophe to its south, and just as its major ally is distancing itself from some of the multilateral organisations that are meant to mitigate such problems. Even if Congress does not enforce all the possible US cuts, it remains prudent to assume that the Trump administration will do as much as it can to avoid new humanitarian commitments in future. This is not only a test of Europe’s financial resources and humanitarian instincts. It is also a serious challenge to European crisis managers on the frontline.

The current humanitarian crises to Europe’s south mainly stem from political instability and recurrent conflicts. Despite the flurry of European efforts to boost security across the region, instability is likely to remain endemic for the foreseeable future. Large-scale UN-led and African-led peace operations have struggled to build order from Mali to Somalia. The decade-old blue helmet mission in Darfur, once the darling of humanitarian campaigners, appears to be especially vulnerable. UN aid workers, crisis managers, and even the secretary-general argue that it is no longer possible to mitigate the region’s conflicts and manage its fragility through reactive humanitarian deployments and stabilisation missions.

This report argues that European governments and the EU as a whole need to invest in more proactive efforts to manage the sources of disorder in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. This means strengthening European civilian crisis management mechanisms and missions (defined in more detail below) and concentrating on mediating recurrent conflicts rather than simply trying to help African governments manage migrant flows better. In some cases, European crisis managers should lead these political efforts – and this is a field in which the United Kingdom and EU can continue to cooperate despite Brexit – but in others, UN officials and African diplomats are better placed take the lead. Even so, EU members can still provide resources and diplomatic support to help them tackle complex crises. European support to the UN and African Union will be even more important if the Trump administration insists on cutting back existing peacekeeping missions across the Sahel. There is both a moral and political imperative to ease the suffering to the south – and taking early steps to tackle these humanitarian crises is an opportunity to show that the EU has not entirely lost a sense of strategic purpose.

While addressing the challenges to Europe’s south requires a range of policy tools – ranging from basic food aid to military action – this report focuses on civilian crisis management as an essential part of the equation. ‘Civilian crisis management’ is a fairly expansive term: recent EU civilian missions have done everything from monitoring ceasefire lines in Georgia to helping boost security arrangements at South Sudan’s international airport. This report notes that, when it comes to the Sahel, the EU increasingly equates civilian crisis response with programmes to improve border management and policing mechanisms to minimise migration flows. But, while this sort of capacity-building may be useful, the report argues that it is also necessary to invest in politically focused crisis management, including: firstly, mediating in major conflicts and situations of lower-level violence; secondly, using political leverage and persuasion to get governments and rebel groups to allow aid into areas hit by humanitarian crises; and, thirdly, coordinating closely with other players, like the UN and the AU, to create strong diplomatic frameworks to stop existing conflicts spreading and potential crises spinning out of control.

Politically focused civilian crisis management is hard to deliver, and success is even harder to guarantee. But, as this report argues, it is crucial to mitigating the cycles of violence affecting the Sahel and Horn of Africa – without it, more technocratic assistance will be in vain.

Europe’s African “security belt”

Although some natural factors, such as low rainfall in Somalia, have created the current famine conditions, the crises in Nigeria, South Sudan, and Somalia are all rooted in conflicts.[6] In Nigeria and its neighbourhood, Boko Haram and regional security forces are trapped in a conflict in which all sides have committed serious abuses against civilians. In South Sudan, three years of civil war have brought the country to a point at which ethnic genocide is an immediate danger. In Somalia, the al-Shabaab jihadi group continues to wage war against European-funded AU forces.

Even if these crises somehow prove manageable, longer-term trends point to continuing instability. Climate change, desertification and demographic factors are all putting the Sahel and neighbouring regions under pressure. Poor governance, transnational criminal enterprises, and long-standing local conflicts drive cycles of violence that past international interventions and development projects have failed to halt.

European governments may have invested increased money, troops, and political capital in handling conflicts in the Sahel and Horn of Africa in recent years, but there is still a major mismatch between the scale of violence affecting these regions and Europe’s response. For harried European officials, already trying to divide their attention between Moscow and the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, events in northern Nigeria or the Sudans are still ultimately second- or third-order priorities.

Many governments were slow to recognise the scale of the security challenges emerging on their southern flank before refugees and migrants began to cross the Mediterranean in large numbers in 2013 and 2014. African security was seen as the preserve of former colonial powers like France and inveterate advocates of the UN like Sweden and Ireland. While the EU deployed a series of small military missions to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Chad in the mid-2000s, these tailed off as the financial crisis and Afghanistan campaign took their toll on European defence establishments. The low point came in late 2008, when the UN asked the EU to send a battle group to back up beleaguered blue helmets in the DRC – and the European Council was so uncertain and embarrassed that it never formally replied.[7]

The migration crisis, coupled with the increasing virulence of Islamist groups such as Boko Haram and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, spurred European powers and the EU institutions to focus much harder on the Sahel, west Africa, and the Horn of Africa (central and southern Africa remain largely off European strategists’ radars, except when violence spikes especially badly as it did in the Central African Republic (CAR)). One European diplomat calls the countries of the region the “security belt” given their growing relevance to European interests.[8] EU members have differed over exactly how to prioritise threats in this belt: There is an open-ended debate over whether to focus on Somalia (London’s priority) or Mali and its neighbours (top of concerns in Paris). As Brexit approaches, these differences may intensify. Nonetheless, Franco-British conceptions of African security are still much closer than they were – the UK sent drones and military trainers to Mali, for example – and EU leaders that previously had no interest in African security affairs whatsoever are now seized of the matter. The most remarkable convert is Angela Merkel, who was wont to argue five years ago that the best way to assist Africa was through arms sales to build up local militaries, but has now committed Bundeswehr troops and helicopters to Mali and herself visited earlier this year.[9] Eastern EU members may still not be convinced, but even Estonia sent soldiers to CAR.

But, rather than conflict resolution, the main focus of European strategy across Africa appears to be containment. The EU used to emphasise its credentials as a peacemaker; today its members often appear more concerned with suppressing terrorists, strengthening borders, and limiting migration than with addressing the political sources of the conflicts that underpin these problems. While the European External Action Service (EEAS) and some member states have boosted their capacities for mediation and civilian crisis management, they have left the political work of peacemaking in African conflicts to the UN and African powers themselves. Other ambitious players, including Russia, China, and the Gulf countries, are increasingly involved in the region, with the potential to marginalise European engagement.

Although EU member states’ initiatives have remained haphazard, over time an overarching European strategy towards instability in Africa has evolved. It is a containment strategy that involves: firstly, limited military operations targeting terrorist groups; secondly, overt and covert cooperation with governments in the region to stem migrant flows, strengthen local security structures, and keep weak states afloat; and, thirdly, turning to the UN and African regional organisations to run major stabilisation missions and deliver large-scale humanitarian assistance.

These parallel efforts could be portrayed as a de facto ‘first line of defence’ for Europe against mass migration (and, some might add, terrorist infiltration, although this overlooks the domestic origins of many terrorist attacks). The second line of defence consists of EU naval operations in the Mediterranean, while the third involves border controls and law enforcement in Europe itself. In fairness, not all European responses to migration flows have been defensive. The European Commission and EEAS have encouraged affected African countries to integrate their economies, and expanded their development efforts to create alternatives to trafficking. But the EU’s political and security response lags behind these economic efforts. Crucially, current military and civilian crisis management operations appear to focus largely on scoring easily quantifiable short-term results rather than addressing the complex political factors which are often overlooked by European policymakers but which both favour migrant traffickers and terrorists and also drive a far wider range of humanitarian crises and conflicts.

ECFR has pressed this point in a series of recent studies. In terms of counter-terrorism, as Anthony Dworkin has argued, the French-led Operation Barkhane in the Sahel has succeeded in disrupting jihadi networks in northern Mali, but “attempts to establish a new political settlement continue to struggle amid a complex array of shifting economic, political, and security relationships.”[10] Meanwhile, as Andrew Lebovich has argued, EU members have developed closer security ties with countries such as Algeria and Niger which aim to stem human smuggling and migrant flows but which risk “worsening the state of human rights, even as [they] may help ameliorate short-term security threats.”[11] Other observers raised similar concerns about Western support to Nigeria and the countries of the Lake Chad Basin in the battle against Boko Haram. For example, the International Crisis Group has warned that regional military operations “possibly make people more susceptible to recruitment by Boko Haram or other militant groups. The militarization of the area previously under Boko Haram’s influence risks generating a cycle of alienation and exclusion.”[12]

EU institutions and states have aimed to recast existing civilian crisis management tools as counter-terrorist and counter-migration mechanisms. Operation Sophia, the naval mission deployed against migrant smugglers in the Mediterranean, is only the most obvious example. The EU’s security capacity-building mission in Niger (EUCAP Sahel Niger), now entering its fifth year, has reorientated itself to focus on border security and other mechanisms for slowing migration.[13] Although the EU Border Assistance Mission in Libya currently has to operate from Tunis with a skeleton staff due to security considerations, it is also looking for ways to help the fragmented Libyan authorities close down migrant routes. It is possible that the EU’s frontier agency, Frontex, may launch a new generation of technical assistance missions in the Sahel, west Africa more generally, and other regions close to Europe that would have even more limited mandates to control human flows, prioritising technical solutions over engaging with local political problems.[14]

Similar concerns hang over the EU’s main military missions in Africa (leaving aside its naval operation off the Somali coast) which are focused on training up armies in CAR, Mali, and Somalia. While the mission in Mali provides recruits with ten weeks of training, for example, this is relatively basic and EU personnel are not allowed to accompany their trainees out on operations (although efforts are under way to rectify this). It is therefore difficult to say whether the Malian troops are really putting their training to good use or respecting human rights while battling armed groups in the north.[15]

European officials often seem willing to take a political back seat in crisis situations more generally.[16] This is true for both EU officials and national diplomats. Less than a quarter of EU civilian crisis management operations have mediation or political confidence-building specifically in their mandates (twice as many are directed to deal with border management).[17] The EEAS has a mediation support unit, which has experience in both Mali and South Sudan, and works closely with a number of non-governmental mediation experts to support its own delegations on political issues.[18] Nonetheless, in most big conflict resolution efforts in north Africa, and indeed the Middle East, European officials and diplomats are generally to be found backing up other mediators. Algeria has been the primary peacemaker for northern Mali that the UN, EU and other regional actors support.[19] A consortium of east African leaders has overseen periodic efforts to rein in the South Sudanese civil war, although they have often moved slowly and at times been directly involved in fuelling the conflict. In so doing they have supplanted not only the UN (which still has over 10,000 peacekeepers in country) but also the Troika – the US, Norway, and the UK – which previously played a central political role in Sudanese affairs.[20] An EU special representative continues to cover the conflict, but most observers agree that only African actors and possibly Chinese diplomats have any real influence in Juba.[21]

There are often very good reasons for European officials, and the EU as an institution, to hold back from leading conflict prevention and mediation efforts in Africa. Regional political actors, such as the AU and ECOWAS in west Africa, have both greater legitimacy and a much greater political stake in taking a diplomatic lead. AU officials have not forgiven NATO for undercutting its attempts to mediate a peace deal with Colonel Gaddafi in Libya in 2011. In many cases, a light-touch diplomatic approach in support of local peacemakers is the best option for Europeans to pursue: UK diplomats, for example, appear to have done significant work behind the scenes to ensure that potentially explosive elections in Nigeria in 2015 went off smoothly.[22] But the current mix of European security and civilian crisis management efforts risks pushing EU members to take a simplistic approach to security in west Africa, the Sahel, and the Horn of Africa, with a strong focus on halting migration and extirpating terrorism but with less attention on the political dynamics driving these phenomena. African officials frequently complain about the instrumental approach of their European counterparts, although this does not stop them requesting military assistance and financial support to fight insurgent groups and manage refugee flows.[23]

The case for civilian crisis management

What could a new emphasis on politically focused civilian crisis management mean in practice on Europe’s southern flank? Very few observers would argue that European governments and the EU institutions could or should try to solve Africa’s conflicts on their own. But closer civilian crisis management is an area where European diplomats and officials may be able to innovate, potentially narrowing some of the divisions that presently afflict the EU.

ECFR has advocated civilian crisis management in the past. In 2009, Daniel Korski and this author argued that EU members and institutions should prepare to deploy more civilian experts to volatile situations with “speed, security and self-sufficiency” (by “self-sufficiency” was meant that officials on the ground should have a high degree of political independence).[24] Yet European civilian crisis management has drifted in the years since, with Brussels largely prioritising military operations. Relatively few governments have made boosting civilian capabilities a priority either: the same report classified Germany, the Nordic countries, the Netherlands, and the UK as civilian crisis management ‘professionals’, with other EU members either trying to catch up or not giving the issue attention.[25] Strikingly, a study published last year by authors unrelated to ECFR concluded that there was no need to update this “extensive naming-and-shaming exercise” as “some member states have made improvements since the publication of this report, but the overall ranking still stands.”[26]

Nonetheless, the growing disorder in the Middle East and north Africa led to a renewed interest in civilian crisis management options. There are a number of potential arguments about which European actors can and should lead in the crisis management field. One is that this is an area in which the EEAS, elements of the European Commission, and EU agencies such as Frontex provide a strong basic framework for common action.[27] Although sometimes lagging behind other multilateral organisations such as the UN, the EU institutions now have considerable experience in deploying Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) missions. EU delegations provide important potential bases for early preventive diplomacy in regions such as the Sahel where many EU members lack a strong presence, and European development funds offer the necessary resources to back diplomatic initiatives. The EEAS recently created a new directorate, PRISM, focused on prevention, mediation and related topics to consolidate its approach.

Conversely, the fact that a relatively small number of European governments have invested in civilian crisis management may suggest that this is actually a field in which a small ‘pioneer group’ of member states could achieve more. An ECFR survey of options for a “flexible union” (i.e. one in which certain subsets of EU member states deepen cooperation on specific areas rather than work through the bloc as a whole) has found that “crisis management” and “humanitarian missions” are the foreign and security areas where progress is most likely.[28] A cluster of nations with a mix of regional knowledge of African trouble-spots (like France) and thematic expertise on crisis management (such as Germany, the Netherlands, and the Nordic countries) could work more closely in this area in future. Institutional precedents exist, including the European Gendarmerie Force (which is committed to strengthening CSDP, but involves only seven EU member states) and the European Institute of Peace (which is based in Brussels, but is an initiative of nine states).[29] Similar subgroups could well invest in flexible cooperation on crisis management and mediating complex crises – in Brussels terms, this could be a case for Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), a device that allows a core group of EU member states to make binding commitments on security policy above and beyond their general EU obligations.[30]

Equally, civilian crisis management could be one area where a post-Brexit UK and the EU 27 could continue to cooperate, as all sides will maintain a shared interest in limiting disorder to Europe’s south, and London has expertise in this area. It has championed EU engagement in Somalia, and recently made a push for the UN Security Council to take greater notice of the crises affecting the Sahel and northern Nigeria. Diplomats from other nations with an interest in multilateral crisis management are blunt about the fact that they will miss British inputs in this field after Brexit. It should not be too hard to find ways to bring the UK back into flexible groupings focused on crisis issues as a “third country”.[31]

Does the future of European civilian crisis management lie with the EEAS and the EU as a whole, therefore, or more flexible multinational structures? There is no neat answer. When, as in the Sahel and Horn of Africa, crisis management involves what have been dubbed “plug-and-play” coalitions – multiple disparate actors like the UN, African organisations and coalitions and so forth – European governments and institutions are likely to engage in different modes and formats.[32] While the new EU Global Strategy insists on the importance of an “integrated approach” to crisis management, most international crisis response is much messier.[33] European officials and diplomats should presume that they will keep on working through multiple frameworks in future – often involving non-European actors – and in some cases it will make sense for flexible coalitions of states to run the show. But there will also be cases in which the EEAS can streamline this messy cooperation by coordinating European efforts.

This does not mean that the EEAS would take over all European efforts to handle a crisis in such situations. Instead, it has the capacity to act as a convener or hub for other actors – including EU institutions like Frontex and member states – in framing a strategic response to a conflict, sharing information and conflict analyses on developing threats, and identifying opportunities for diplomats and aid agencies to engage in crisis areas. EEAS officials could also take the lead in liaising with other actors, such as the UN and AU, on crisis response on behalf of other European actors. Such liaison work will often be time-consuming but crucial, because, as the next section of this report emphasises, these actors have become severely overstretched.

The AU and the UN take the strain

Although limited numbers of European soldiers have been involved in small wars in Africa, they have also left the bulk of stabilisation operations to non-Western UN peacekeepers and African forces. In many cases, these troops have both European money and training behind them: the European Commission can take a large part of the credit for turning the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) into a half-decent fighting force, for example.

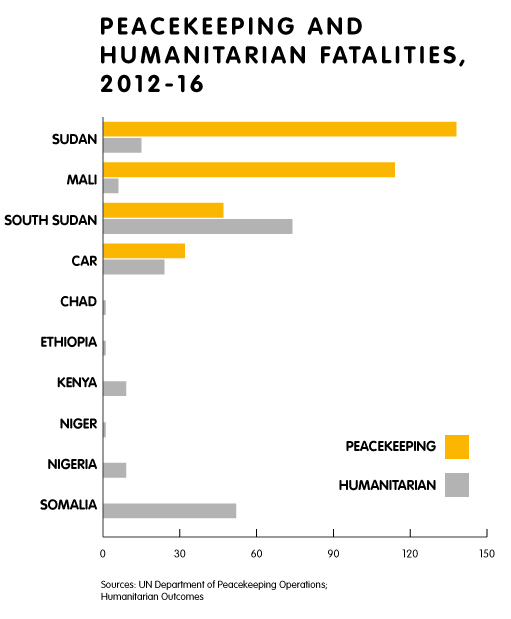

But the UN and AU are feeling the strain of these military operations. Islamist insurgents have killed scores of peacekeepers in Mali, and al-Shabaab has claimed many more lives in Somalia.[34] Since the civil war began in South Sudan in 2013, many UN peacekeepers have effectively refused to venture beyond their bases. Government troops raped aid workers within a few hundred yards of Chinese and Ethiopian peacekeepers in the capital, Juba, last July but the blue helmets refused to respond. It is hard to see how such poorly motivated forces can prevent the crises that create the humanitarian disasters that could drive more refugees towards Europe.

This is a point that UN officials have been making loudly in recent years. Humanitarian aid and peace operations experts alike have been underlining the limits of what they can do, and pleaded with the Security Council and aid donors to put them under less pressure. The watchword across the UN today is “prevention”.[35] Officials insist that the only way to break the cycle of violence and humanitarian shocks that have affected the Sahel and east Africa is to invest in greater political, primarily civilian, efforts to avert or resolve conflicts.[36] New secretary-general Antonio Guterres has put the theme at the heart of his political messaging since taking up his post in January.[37] This theme also runs through recent EU policy documents, including its Global Strategy, and has new traction in European capitals, including Berlin.

If the current crises in Africa threaten to create new headaches for Europe, it is already testing the strategic capacities of the AU and UN. The two organisations are responsible for five major peace operations in the Sahel and Horn of Africa, including the UN missions in Mali and South Sudan (MINUSMA and UNMISS), a joint UN-AU force in Darfur (UNAMID), AMISOM, and a Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNJTF) targeting Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin. Just as the EU and NATO are shifting away from large nation-building operations, these missions are struggling to hold down violence over large areas with appalling infrastructure. They are crucial parts of international efforts to maintain Africa’s “security belt”, but are also arguably some of the weakest links in the security chain.

The UN-AU hybrid mission in Darfur, launched in 2007, is the weakest link of all. Despite its high profile and mandate to facilitate humanitarian aid, it has always been under-equipped and easily manipulated by the Sudanese government. Differences between the UN and AU over how to deal with Khartoum have made its work harder. Humanitarian officials and peacekeeping experts alike believe that the operation should be allowed to die a gentle and honorable death, not least because it is very expensive.[38] By contrast, few believe that it will be possible to kill off UNMISS in South Sudan any time soon, although it increasingly looks worryingly like UNAMID in many ways. A few courageous exceptions, such as a widely praised Mongolian contingent that has been willing to take risks, have not saved the operation’s reputation. But overall, UN investigators commenting on UNMISS found “a lack of leadership on the part of key senior mission personnel culminated in a chaotic and ineffective response to the violence.”[39]

Meanwhile, the operations in Somalia and Mali are both tackling the threat of jihadism with far fewer resources than Western militaries mustered in Afghanistan and Iraq. AMISOM has enjoyed some success in rolling back al-Shabaab in Somalia with UN support, although it has taken serious but unreported casualties along the way. Over the last year, however, al-Shabaab has regrouped and struck back, and a number of force contributors including Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda have started to back away from the mission. AU officials insist that it must begin withdrawing in 2018. This is a dilemma for the European Commission, which has covered the bulk of AMISOM’s costs through its African Peace Facility, and the EU as a whole. The commission has been worried about spiralling costs, and cut the amount it pays per soldier last year, while France has pushed for a shift in EU funds to crises in Francophone Africa. It will still be an embarrassment if AMISOM withdraws with its mission unaccomplished.[40] In Mali, meanwhile, MINUSMA faces hard choices over how far it is willing to go to battle with al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and other insurgents in the north of the country. To date, it has largely left active counter-terrorism operations to the parallel Operation Barkhane, and regional powers have said that they are willing to launch an additional counter-terrorist force of their own (if, that is, Europe is willing to pay).[41] But terrorist groups frequently attack MINUSMA, and it is not clear that the peacekeepers can avoid turning into a counter-insurgency force indefinitely.[42]

MINUSMA’s dilemma is exacerbated by the fact that the force is split between a highly capable minority of NATO countries – with Germany, as noted earlier, taking a major role – and a majority of under-resourced African and Asian troops. Since the mission initially deployed in 2013, European contingents (at first led by the Netherlands) have offered the UN assets, such as a NATO-style intelligence unit and Apache helicopters that the organisation can rarely field elsewhere.[43] But African contingents, sometimes bringing less than half of the basic kit that the UN says they need, do a lot of the frontline patrolling and security work that keeps the operation going.[44] They are also the most frequent targets for terrorists.

The AU-backed MNJTF fighting Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin is something of an enigma, although, like AMISOM, it has received EU financial support. Its increased activity, along with the Sahel states’ offer to stand up a new counter-terror force, suggest that African governments are still keen to intervene forcefully in local crises. This January, Senegal deployed troops into Gambia to enforce the results of national elections when the incumbent president refused to stand down. An initial review of the operation suggests that this could stand as “a new model of African coercion”, but the circumstances were propitious: Gambia is tiny enclave within Senegal and the recalcitrant president had little military or popular support.[45] It is hard to scale up this sort of success. Looking at cases like Mali and the Sudans, a growing number of UN officials in particular have begun to argue that such heavy stabilisation missions are no longer sustainable. There is particular concern in the UN that the institution could be drawn into more counter-terror missions in cases like Mali. There is also frustration among UN officials that, even where international military forces are present, attacks on aid workers are common. Forty-two humanitarians were killed, wounded, or kidnapped in South Sudan in 2015 (the last year for which consolidated figures are available) according to Humanitarian Outcomes, an NGO that tracks aid worker security.[46] Twenty-six suffered similar fates in Somalia. Only Afghanistan saw more attacks for aid workers – remarkably, Syria and Yemen both witnessed marginally fewer incidents than Somalia.

A high-level panel report on the future of UN operations in 2015 recommended that these should shift towards conflict prevention and emphasise the “primacy of politics” in future efforts rather than stick with existing peacekeeping structures.[47] The secretary-general appears to take this idea to heart.

Since taking office, Guterres has called for a “surge in diplomacy for peace”, and promised new UN initiatives on both prevention and mediation.[48] He seems keen to shift his organisation away from large-scale peacekeeping operations towards lighter diplomatic efforts to avert and manage crises. There are a few good models for achieving this. Since 2000, a UN conflict prevention office for west Africa based in Senegal has been keeping potential trouble-spots such as Guinea and Burkina Faso out of the headlines through intensive regional diplomacy to manage political flare-ups.[49] The UN has also embedded experts on prevention in many of its development teams in weak states and built up a standby team of mediation experts to deploy at short notice to help envoys in escalating crises. The EU and other multilateral organisations have often copied some of these innovations. But, as Guterres recognises, crises in regions like the Sahel still outstrip the UN’s abilities to prevent them.

It is not clear how concrete his thinking is, or how far Guterres will be able to change the UN. His predecessor, Ban Ki-moon, also liked to talk about prevention. But all UN officials agree that Guterres, as a former Portuguese prime minister and head of UNHCR, is a much more impressive operator than Ban. His message about lighter conflict management is also timely, and quite probably inevitable, given the Trump administration’s demands for cuts to the UN’s budget: In addition to threatening to curb humanitarian spending, the new administration has explicitly stated that it wants to rein in spending on peacekeeping, possibly by up to $1 billion.[50] The US has prompted other members of the Security Council to “review missions and identify areas where mandates no longer match political realities.”[51] The US ambassador to the UN, Nikki Haley, has implied that UNMISS is a case where cuts may be appropriate.[52] While such talk has provoked howls of outrage from American advocates of the UN, Haley is arguably on to something: given their record, many UN missions need to be overhauled, shrunk, or both. What is not clear is whether the US will approach this in a rational fashion, or pursue big cuts with no strategic logic.

Guterres may be able to sell some of his ideas about prevention to Washington as cost-cutting measures that will allow the administration to say it has disciplined the UN. But Guterres’s emphasis on political factors should resonate with European policymakers too. As noted earlier, European military and civilian crisis management measures in the southern “security belt” in recent years have often seemed curiously apolitical, emphasising short-term successes over long-term social dynamics. Equally importantly, the humanitarian crises that have blown up in Africa in recent months can be traced to unresolved political tensions. The 2016 EU Global Strategy underlines the need for more preventive diplomacy in terms similar to those of Guterres. If the UN is willing to grapple with how to do prevention and mediation better, European governments and institutions should listen to its suggestions very closely – and consider how they may contribute to and shape this shift.

Conclusion

Simply saying that Europe and the UN should invest more in prevention and less in reacting to conflicts is necessary but not nearly sufficient. It is certainly true that they should double down on preventive efforts in countries where violence is a threat but not yet a reality. But looking across the African “security belt”, let alone the Middle East, it is patently too late for gradual efforts to ward off war. Violence and humanitarian catastrophes are already in progress, and Europe has already felt their indirect effects.

Overall, it appears probable that west Africa, the Sahel, and the Horn of Africa will remain unstable for the foreseeable future. The level of violence is liable to fluctuate unpredictably, reflecting a complex mix of environmental, political, and transnational factors. Political crises and humanitarian challenges such as famine are likely to fuel one another. Jihadi groups and other political predators will take advantage of these conflicts to seize territory. A mix of financial, political, and operational factors will mean that the Security Council is unlikely to reach for large-scale blue helmet operations to respond to crises in the region in future. The UN may well cut back the peacekeeping operations it already has there, with unpredictable security implications. In some cases the AU and other regional organisations may deploy alternative military forces. But these will not necessarily be well planned or disciplined operations. In sum, there is a high risk of ongoing, fluctuating instability across these regions – and European powers and the EU will face humanitarian and political pressure to manage these threats.

What will this new generation of conflict management look like? Five broad points seem clear. This paper concludes by proposing a number of ways these five points can be addressed.

The first is that there is an urgent requirement for reinforced humanitarian diplomacy in order to ensure that food and aid reaches the suffering in Nigeria, Somalia, and South Sudan to avert an immediate humanitarian disaster.

Second, European governments and the EU need to rethink their containment strategies for tackling migration and terrorist threats across west Africa, the Sahel, and the Horn of Africa. While limited military and civilian actions may help address short-term challenges, European policymakers will need to engage more deeply in local, cross-border, and regional political challenges if they are to stand any chance of limiting these threats. The EEAS has already set up PRISM to bring together its preventive and mediation work in Brussels. While this is a work in progress, it may be the basis for more effective action in Africa.

Third, while it may make sense for Europeans to play second fiddle to African leaders, the UN and others in mediation processes in the Sahel and beyond, EU members should be able to collectively or individually deploy greater mediation assets at short notice to facilitate political processes, even if only in a supporting role. Anticipating and engaging early in looming conflict crises, establishing political ties to key players, is essential to mitigating the risks of future humanitarian crises before they arise.[53]

Fourth, European planners need to prepare for an era in which hefty UN-led peace operations play a diminishing role in African security. In the short term, this means addressing how the UN can unwind its deployments in cases such as Darfur without unreasonably increasing the risks of new violence. In the longer term, it will mean asking how the EU can mount light-weight civilian or military missions without having the UN as partner, as it has in Mali or (looking beyond the Sahel), CAR, and the DRC. It also means thinking through how the EU can provide long-term support to AU peacemaking and stabilisation efforts more fully.[54] AU officials have, for example, long complained that the EU and UN were willing to support its military presence in Somalia but not fund African political staff to work alongside the troops. The UN is now helping the AU roll out civilian advisers across Somalia, but there is still far more work to do.

Fifth and finally, Guterres needs strong European support on advancing his prevention/political agenda if he is going to have much chance of guiding the UN as a whole through the early phase of the Trump administration. The last two UN secretaries-general, Kofi Annan and Ban Ki-moon, both took office with the advantage that they enjoyed very positive relations with Washington. To succeed in this endeavour, Guterres needs to have strong substantive and financial support from Europe as well as goodwill.

Guterres needs to lay out some of his more specific plans about prevention and mediation before European officials can work out how best to support him. UN insiders and analysts expect him to emphasise the need to build up more local mediation capacities in weak states, and to look for ways to tie long-term development programming to averting future conflicts. These are laudable goals, and in line with current European thinking on helping fragile states. But, given the extremely urgent nature of the humanitarian and political crises emerging on Europe’s southern flank, there is a need for short-term and medium-term actions too, involving both direct European initiatives and support to the AU and UN.

There are a number of steps that EU institutions and member states could take which would fulfil the five strategic imperatives outlined above, and which would also assist Guterres in his efforts at the UN. These are as follows.

Launching a ‘Fighting Fund’ and ‘Pioneer Group’ for Humanitarian Diplomacy in 2017

Given the strong political dynamics behind the looming famine conditions in the Sahel and Somalia (in addition to Yemen) European governments and institutions should not only, firstly, find extra cash to meet the operational needs of aid agencies; but, secondly, set up a small but flexible trust fund specifically to support political initiatives to facilitate aid deliveries in these countries in 2017. These could include UN, AU, or NGO initiatives, and cover the costs for efforts at local mediation, reconciliation programmes, and attempts to back cessation of hostilities. In addition – in a small experiment with ‘flexible cooperation’ – concerned EU members should create a ‘pioneer group’ of European diplomatic (or military) experts who could be seconded at short notice to give expert support to these humanitarian efforts.[55] (These could also act as trial runs for proposals for the creation of a more formal ‘core group’ of EU members focused on crisis management under PESCO.)

Boost mediation and political resources in CSDP missions and along the African “security belt”

Recognising the political dimensions of building security forces, boosting the rule of law, and addressing migration in Europe’s southern peripheries, the EU should increase the number of mediation experts and political analysts in the region attached to civilian and military CSDP missions to improve their situational awareness and capacity to exploit openings for political engagement.[56]

Plan for ‘post-peacekeeping’ scenarios

Recognising the likelihood that the existing ‘framework’ for deploying CSDP missions in the Sahel involving large-scale UN missions may not be sustainable, the EEAS and/or concerned European states should, firstly, conduct a medium-term planning exercise to address how future CSDP civilian crisis management missions could deploy to volatile states in the Sahel and neighbouring regions without large-scale UN operations as cover; and, secondly, liaise closely with Guterres and the UN on how joint European-UN civilian crisis management efforts could work in these cases. Concerned EU members – such as those that have sent troops to Mali and other UN missions in recent years – should fund triangular EU-UN-AU discussions of future ‘post-peacekeeping’ options for conflict management.

Open regional prevention centres

Going further, the EEAS should copy the successful UN model of the regional prevention office in Senegal noted above: It should consider creating two or three small mediation/prevention centres with regional conflict mandates in existing EEAS delegations in centres such as Dakar and Addis Ababa. These prevention offices could act as the ‘antennae’ of the EEAS mediation unit located in Brussels, but could also second officials to back up envoys from other organisations, like the UN and AU, as necessary.

Work with the UN to build up African civilian capacities

As the AMISOM case has shown, there is a need to expand the civilian crisis management capacities of the AU and other African organisations to match their military activities. Expanding African capacities would not only assist missions, like AMISOM, but also potentially help craft exit strategies for large-scale peace operations such as UNAMID by enabling lighter African follow-on missions. The AU has been gradually developing civilian training for over a decade, but it is still relatively limited. To manage this sort of training, the UN and EEAS and/or European states could set up a joint programme at the AU headquarters in Addis Ababa. (An alternative project deliverer could be the European Institute of Peace, a body founded by a consortium of European governments in Brussels to mirror the US Institute of Peace.)[57]

Give Guterres flexible resources for prevention

While European countries are already collectively the leading donors to UN preventive and mediating activities (in addition to humanitarian, peacekeeping, and development work) they should make some resources available to let the new secretary-general develop his headline policies on prevention and mediation over the year ahead. In straitened financial circumstances thanks to the US, Guterres is unlikely to have much free cash to invest in pilot prevention projects or new mediation techniques. If he has to work through existing UN budgets and process, he will get bogged down in the bureaucracy. European governments should pool some funds, with no strings attached, for Guterres to roll out experimental UN political projects in the next 12-24 months to give the secretary-general a chance to quickly make his stamp on the slow-moving UN.

These are all technical elements of what has to be a larger strategic effort by European governments and institutions to halt the deterioration of conflict situations in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. This effort will be complicated by the fact that European planners also have to look, and will almost inevitably pay more attention, to the Middle East and Russia. European attempts to chart a way forward in the multilateral domain in particular are also liable to be blown off course at regular intervals by the Trump administration’s endless capacity to create surprises. The more that European powers are willing to show leadership in this field, the more they may Trump-proof their plans. And, of course, the more they act, done in the right way the more they are likely to bring about real improvements to their south. Moving beyond a “security belt” conception of the Sahel and Horn of Africa, European member states and EU institutions will be able to not only alleviate the pressures on themselves, they will also take steps towards finding more enduring solutions to the problems currently afflicting many African countries.

About the author

Richard Gowan is an associate fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, specialising in the United Nations and conflict management. He also teaches at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and writes a weekly column (‘Diplomatic Fallout’) for World Politics Review. He was previously research director at NYU’s Center on International Cooperation, and has recently worked as a consultant with the International Crisis Group, the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, and the UN Department of Political Affairs.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Dina Pardijs at the European Council on Foreign Relations for guiding this project and Adam Harrison for editing the final text. Arjan Uilenreef and Charlotte Talens at the Embassy of the Netherlands in London have been generous and thoughtful sponsors. At ECFR, Susi Dennison, Alexander Harding, Manuel Lafont Rapnouil, Andrew Lebovich, and Mattia Toaldo also gave very helpful advice. A number of national and international officials also read earlier drafts and provided very useful feedback. All views and errors are the author’s own.

ECFR would like to thank the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in London for its support for this project.

[1] The data in this paragraph is based on comments by Stephen O’Brien, UN under-secretary-general for humanitarian affairs to the Security Council on 10 March 2017, available at http://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/usgerc-stephen-o-brien-statement-security-council-missions-yemen-south-sudan-somalia.

[2] Tom Murphy, “UN Re-ups Historic Famine Warning as Funding Stagnates”, Humanosphere, 14 April 2017.

[3] “UN appeals for Record $22.2 Billion in Global Humanitarian Aid”, Deutsche Welle, 5 December 2016.

[4] Harriet Grant, “UN Agencies ‘Broke and Failing’ in Face of Ever-Growing Refugee Crisis”, The Guardian, 6 September 2015.

[5] Remarks by Federica Mogherini at the 2017 Carnegie Nuclear Policy Conference, 20 March 2017, available at https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/23056/high-representativevice-president-federica-mogherini-2017-carnegie-nuclear-policy-conference_en.

[6] For a brief overview of these factors see David Pilling, “As Democracy Retreats, Famine Makes a Comeback”, Financial Times, 22 March 2017.

[7] See Richard Gowan, “From Rapid Reaction to Delayed Inaction? Congo, the UN and the EU”, International Peacekeeping, Vol. 18, No. 5 (2011).

[8] Discussion with European diplomat, 15 March 2017.

[9] Dagmar Engel, “Merkel’s Migration Mission to Mali,” Deutsche Welle, 10 October 2016.

[10] Anthony Dworkin, “Europe’s New Counter-Terror Wars”, ECFR, October 2016, p. 16., available at https://ecfr.eu/publications/summary/europes_new_counter_terror_wars7155.

[11] Andrew Lebovich, “Beyond Securitisation in the Sahel”, ECFR, 3 March 2016, available at https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_beyond_securitisation_in_the_sahel.

[12] “Lake Chad Basin: Controlling the Cost of Counter-Insurgency”, International Crisis Group, 24 February 2017, available at https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/lake-chad-basin-controlling-cost-counter-insurgency.

[13] Thierry Tardy, “The New Forms of Civilian Crisis Management”, in Recasting EU Civilian Crisis Management, European Union Institute for Security Studies, March 2017, p. 28., available at http://www.iss.europa.eu/publications/detail/article/recasting-eu-civilian-crisis-management-1/.

[14] Roderick Parkes, “Frontex as Crisis Manager”, in Thierry Tardy, ed., Recasting EU Civilian Crisis Management, pp. 49-57. See also Roderick Parkes, “Out of (and Inside) Africa: Migration Routes and Their Impacts”, European Union Institute for Security Studies, April 2017, available at http://www.iss.europa.eu/publications/detail/article/out-of-and-inside-africa-migration-routes-and-their-impacts/.

[15] The author thanks Andrew Lebovich, who is currently preparing a more detailed study of Mali for ECFR, for these observations.

[16] One recent analysis concludes that “the EEAS (and the EU more generally) is still too little engaged in preventive diplomacy, which limits the EU’s ability to prevent conflict.” See Laura Davis, Nabila Habbida, and Anna Penfrat, Report on the EU’s Capabilities for Conflict Prevention, EU-CIVCAP, EPLO, January 2017, p. 18., available at https://eucivcap.files.wordpress.com/2017/02/eus_capabilities_conflict_prevention.pdf.

[17] Hylke Djikstra, Petar Petrov, and Ewa Mahr, Preventing and Responding to Conflict: Civilian Capabilities in the EU, UN and OSCE, EU CIVCAP Project, Maastricht University, November 2016, p. 19.

[18] See a useful institutional factsheet on the Mediation Support Unit at http://www.eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/factsheets/docs/factsheet_eu-mediation-support-team_en.pdf.

[19] Algeria has played a mediating role in northern Mali since the 1960s.

[20] The Troika, EU, and other Western players have, however, participated in a broader grouping to support the Africans. See “South Sudan: Keeping Faith with the IGAD Peace Process”, International Crisis Group, July 2015.

[21] Abigaël Vasselier, “Chinese Foreign Policy in South Sudan: The View From the Ground”, China Brief, Vol. 16, Issue 13, 22 August 2016, available at https://jamestown.org/program/chinese-foreign-policy-in-south-sudan-the-view-from-the-ground/.

[22] Babatunde Afolabi and Sabina Avasiloae, Post-Election Assessment of Conflict Prevention and Resolution Mechanisms in Nigeria, Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, November 2015, p. 13.

[23] On African reactions to European concerns about terrorism, see Annelies Pauwels, Preventing Terrorism in the South, European Union Institute for Security Studies, March 2017.

[24] Daniel Korski and Richard Gowan, “Can the EU Rebuild Failing States? A Review of Europe’s Civilian Capacities”, ECFR, October 2009, p. 64.

[25] Ibid., p. 46.

[26] Djikstra et al, p. 41.

[27] For multiple useful perspectives on this issue see Thierry Tardy, ed., Recasting EU Civilian Crisis Management, European Union Institute for Security Studies, January 2017.

[28] Almut Möller and Dina Pardijs, “The Future Shape of Europe: How the EU Can Bend Without Breaking”, ECFR, March 2017, p. 4., available at https://ecfr.eu/specials/scorecard/the_future_shape_of_europe.

[29] The states involved in the European Gendarmerie Force are: France, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, and Spain. The founders of the European Institute of Peace were: Belgium, Finland, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland.

[30] See, for example, Möller and Pardijs, “The Future Shape of Europe: How the EU Can Bend Without Breaking”, p. 9.

[31] Turkey has worked with the European Gendarmerie Force, and the Swiss helped launch European Institute of Peace.

[32] Richard Gowan, “The Case for Cooperation in Crisis Management”, ECFR, June 2012, p. 6.

[33] See Thierry Tardy, The EU: From Comprehensive Vision to Integrated Action (European Union Institute for Security Studies ISS, February 2017).

[34] Kevin Sieff, “The World’s Most Dangerous UN Mission”, The Washington Post, 17 February 201

[35] See Megan M Roberts, “Prevention Could be Cure for a UN in Flux,” IPI Global Observatory, 3 March 2017.

[36] See, for example, speech to European Policy Centre by Filippo Grandi, high commissioner for refugees, 6 December 2016, available at http://www.europeanmigrationlaw.eu/en/articles/news/unhcr-filippo-grandi-speech-at-the-european-policy-centre.

[37] Michelle Nichols, “New UN Chief Urges Security Council to do More to Prevent War”, Reuters, 10 January 2017, available at http://www.reuters.com/article/us-un-guterres-idUSKBN14U23N.

[38] UNAMID’s budget is currently over $1 billion a year, while UNMISS costs slightly more and MINUSMA slightly less. See cost figures at http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/resources/statistics/factsheet.shtml.

[39] The UN has only released the executive summary of the report, which is available at http://www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/sudan/Public_Executive_Summary_on_the_Special_Investigation_Report_1_Nov_2016.pdf.

[40] See Paul D Williams, “Paying for AMISOM: Are Politics and Bureaucracy Undermining the AU’s Largest Peace Operation?” IPI Global Observatory, 11 January 2017.

[41] “African Leaders Agree to new Joint Counter-Terror Force”, France 24, 6 February 2017, available at http://www.france24.com/en/20170206-african-leaders-agree-new-joint-counter-terrorism-force.

[42] Kevin Sieff, “The World’s Most Dangerous UN Mission”, The Washington Post, 17 February 2017, available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/sf/world/2017/02/17/the-worlds-deadliest-u-n-peacekeeping-mission/?utm_term=.3e95a4ce29d8.

[43] See Adam C Smith and John Karlsrud, “Europe’s Return to Peacekeeping in Africa? Lessons from Mali”, International Peace Institute, July 2015, available at https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/IPI-E-pub-Europes-Return-to-Peacekeeping-Mali.pdf.

[44] Peter Albrecht and Signe Cohn-Ravnkilde, “African Soldiers Are in the Firing Line in Mali”, DIIS, December 2016, p. 4.

[45] Paul D Williams, “A New Model of African Coercion? Assessing the ECOWAS Mission in the Gambia”, IPI Global Observatory, 16 March 2017.

[46] See Aid Worker Security Report: Figures at a Glance, Humanitarian Outcomes, 2016. The NGO also compares the number of casualty/kidnapping incidents with the overall number of aid workers based in a country. On this basis, Somalia is actually slightly more dangerous than Afghanistan and considerably more dangerous than South Sudan.

[47] The High-Level Panel on Peace Operations, Uniting Our Strengths for Peace: Politics, Partnerships and People: Report of the High-Level panel on Peace Operations, United Nations, June 2015, pp. 11-12.

[48] Tom Miles, “Guterres Vows UN Reform and Diplomatic ‘Surge’”, Reuters, 18 January 2017, available at http://www.reuters.com/article/us-un-guterres-idUSKBN1521KH.

[49] See Richard Gowan, “Multilateral Political Missions and Preventive Diplomacy”, US Institute for Peace, 2011, p. 4.

[50] Colum Lynch, “Trump Administration Eyes $1 Billion Cuts to UN Peacekeeping”, Foreign Policy, 23 March 2017, available at http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/23/trump-administration-eyes-1-billion-in-cuts-to-u-n-peacekeeping/.

[51] Somini Sengupta, “UN Peacekeeping faces Overhaul as US Threatens to Cut Funding”, The New York Times, 24 March 2017, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/24/world/united-nations-peacekeeping-trump-administration.html.

[52] During her confirmation hearing, Haley noted: “If we look at South Sudan, it’s terrible, but you also have to look that we’re not getting cooperation from their own government.” See Barbara Crossette, “Nikki Haley Tells Congress: The UN Does Matter”, The World Post, 24 January 2017.

[53] On these issues, see “Seizing the Moment: From Early Warning to Early Action”, International Crisis Group, June 2016.

[54] For a range of perspectives on this issues, see Cedric de Coning, Linéa Gelot, and John Karlsrud, The Future of African Peace Operations: From the Janjaweed to Boko Haram, London, Zed Books, 2016.

[55] These experts would focus on providing light-weight support to existing field operations, and would act as independent advisers rather than reporting back to Brussels.

[56] It is crucial that officers deployed in this way should have sufficient local or regional expertise to add value – simply adding political generalists without local knowledge will not make much difference.

[57] Any such project should be coordinated with African actors, such as the think-tank/NGO ACCORD. Additionally, European governments should continue to advocate new mechanisms for funding AU missions – such as through more systematic UN financing – even though the Trump administration is likely to balk at any proposals that would cost it extra money.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.