After ISIS: How to Win the Peace in Iraq and Libya

Summary

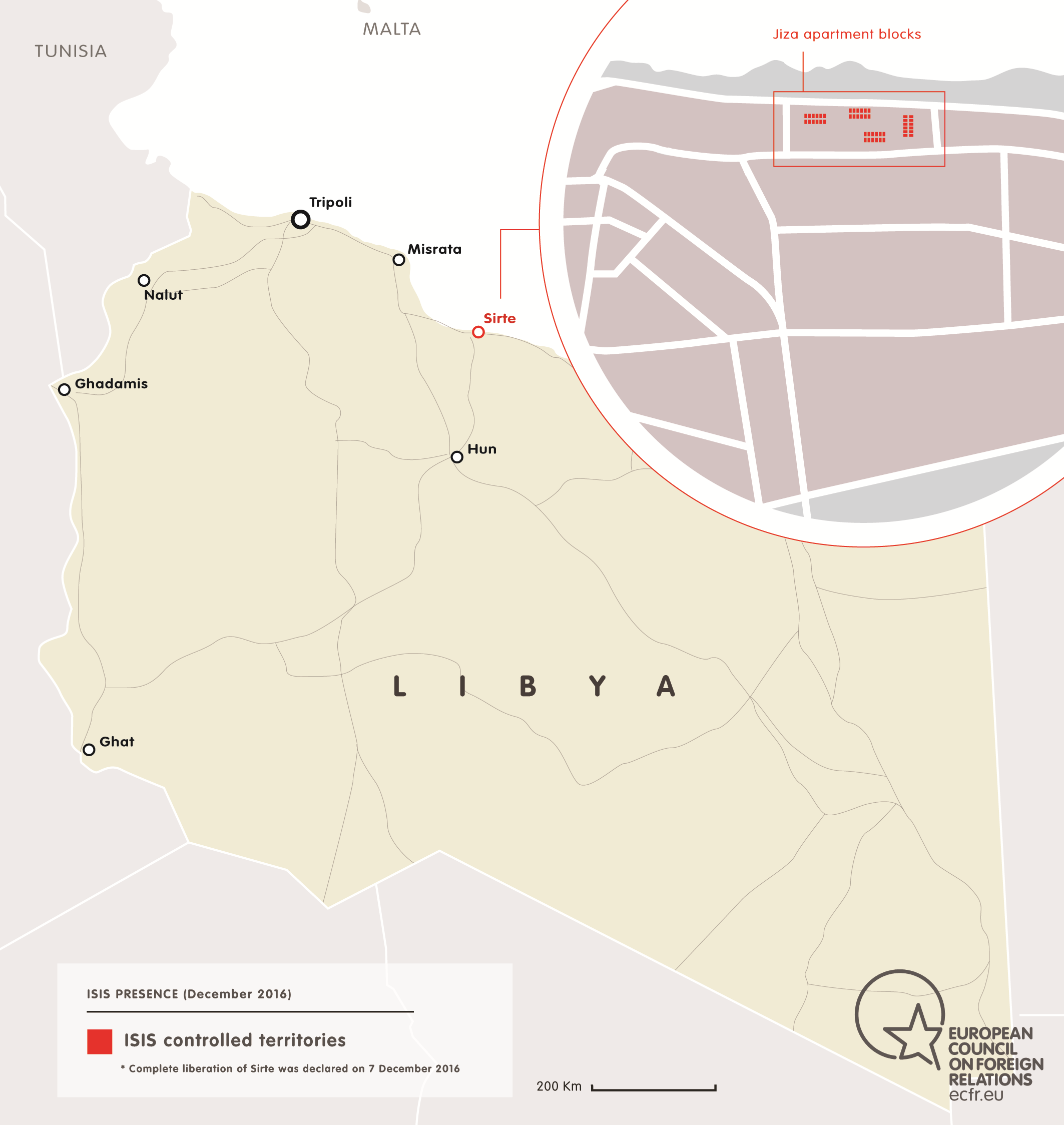

- ISIS has suffered significant setbacks in both Iraq and Libya with the battles for Mosul and Sirte representing potential turning-points.

- Without a clear political strategy to guide post-ISIS efforts, these military gains could quickly be lost. Both countries could again become breeding grounds for conflict and extremism, exacerbating European security and migration challenges. This risk is especially high for Iraq given the conflict in neighbouring Syria.

- The new US administration is likely to invest less energy than its predecessors in strengthening political orders which provide stability. European states must step up their own efforts.

- Iraq will need increased efforts on representative power-sharing, including deeper decentralisation, locally directed reconstruction, and security sector reform.

- In Libya, Europeans should focus on broadening the local and international coalition supporting the UN-backed political agreement, in part through economic tools. They should also focus increased economic recovery efforts on the reconstruction of Sirte and Benghazi.

Policy recommendations

In Iraq:

- Refocus from humanitarian aid to economic development: the EU and its member states should agree on a timeline to gradually shift existing economic stabilisation funds for Iraq towards development programmes that aim to promote job creation and long-term investment in the country.

- Support decentralisation efforts led by Baghdad: European actors should support the Iraqi central government in its efforts to roll out a process of decentralisation.

- Push for political progress within the KRG: European states should, for example, press for greater transparency in government spending and oil exports.

- Reform the security sector: European member states should work together with the central government through increased financial aid and training to bolster and professionalise the Iraqi security and intelligence apparatus.

- Fill potential gaps in US-Iran channels: European member states such as the UK, France and Germany will become important players in defusing areas of tensions between Tehran and Washington that could provoke over-reactions against one another’s military positions in Iraq.

In Libya:

- Strengthen the political coalition behind Tripoli’s government: the EU and its member states, through bilateral and multilateral mediation and engagement with Libyan political actors, could work to expand the coalition-backing unity efforts.

- Help Libyans build a decentralised state: the EU should help to (1) unlock funds from the central government for municipalities; (2) encourage coordination and provide advice and recommendations on best practice; (3) promote capacity-building through ‘on the job training’ in Europe for Libyan civil servants.

- Support deep reconciliation efforts: EU member states should provide logistical support or ‘adopt’ tracks of dialogue similar to those pursued in the past by countries undergoing democratic transition, like Spain or Bulgaria.

- Pursue military de-escalation: the EU and its member states should support efforts to reach a military deal between different actors in western and southern Libya.

- Conclude an economic deal to keep the country united: the EU and its member states must give concrete support to a deal that saves the country from economic collapse while addressing the legitimate concerns of eastern Libya about marginalisation within a unified Libya.

- Do not forget Sirte (and Benghazi): de-mining, humanitarian relief, and building the conditions for the safe return of IDPs are priorities not just for Sirte’s residents but also for the stability of the rest of western Libya.

- Deal with regional powers and Russia through the UNSC, and set up an EU member state ‘contact group’: its main policy should be to preserve the ‘architecture’ of resolutions and agreements negotiated by the UN and approved by the UNSC over the past two years with the support of the US, Egypt and Russia.

Introduction

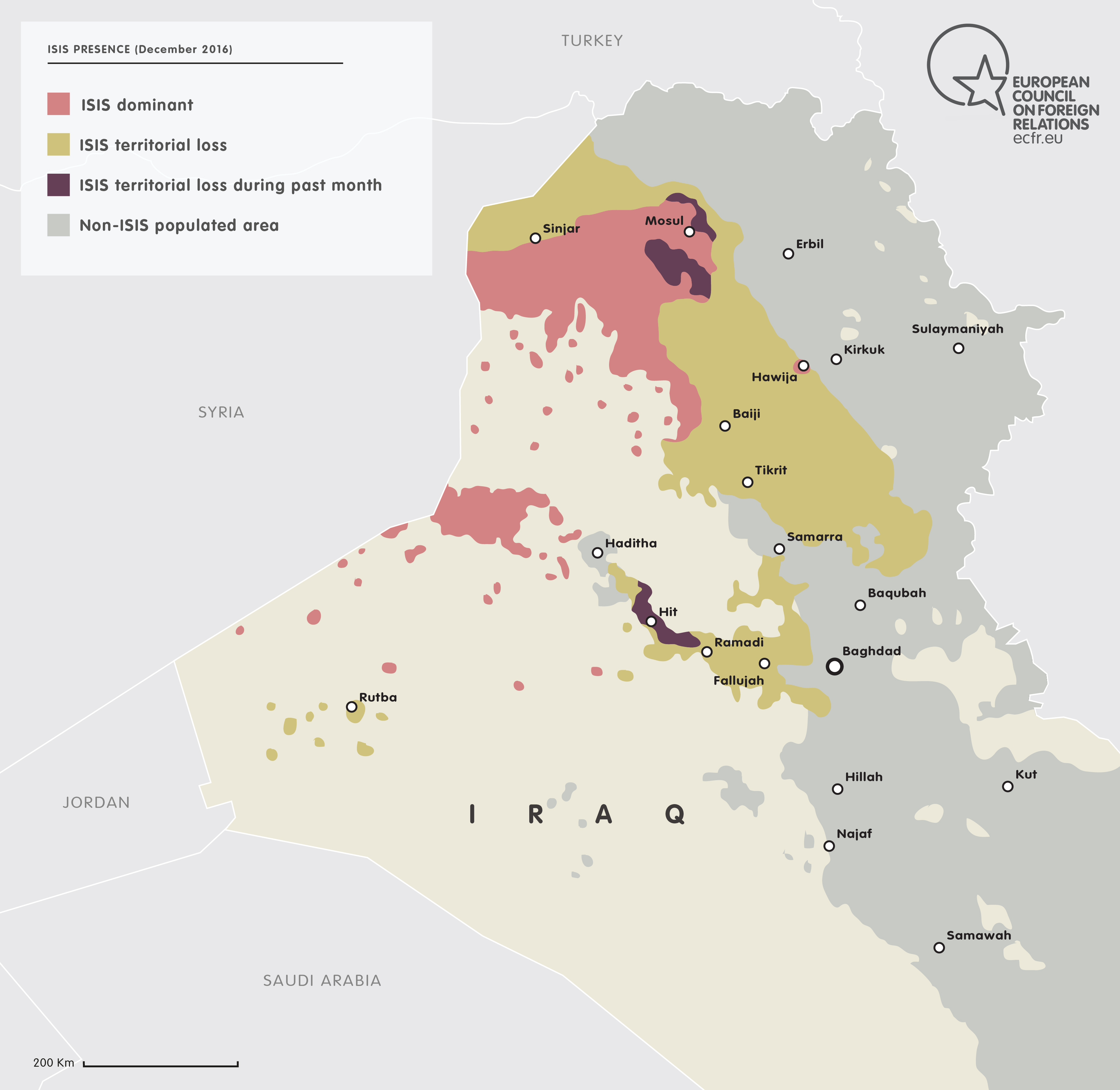

2016 was not a good year for the Islamic State group (ISIS). Under a military onslaught from the United States-led Global Coalition against ISIS and its local allies, ISIS lost vast territory and thousands of fighters in Iraq, Libya and Syria. This is welcome news, but, as ISIS’s grip on territory loosens, the perhaps more difficult task of establishing a new political order begins. In recent years we have learned to our cost that counter-terrorism without stabilisation simply does not work. Without a sustained international effort to address the political and economic grievances that gave rise to ISIS a new wave of extremism and conflict will surely follow.

This problem presents itself most immediately in Iraq and Libya, both of which may soon be free of all ISIS territorial control. The potential for renewed conflict in these countries is increased by power rivalries between competing armed political and militia factions. Many of these factions find support from regional powers, which, having fought hard to counter ISIS, now want to retain a degree of influence in the liberated areas.

In such circumstances, it is simply not enough to establish a new government, call it ‘inclusive’, hold some elections and then leave the country to stew in economic, political, sectarian and security problems. Greater instability in Iraq and Libya is possible if the post-ISIS transition does not deal with the core drivers of extremist forces, or if regional rivalries provoke further conflict among the forces that defeated ISIS.

The incoming administration of Donald Trump in the United States has evinced little interest in investing in the political stabilisation that the region and – by extension – Europe needs. In that case, the need for a strong European role and intensified political engagement will become more urgent and critical. While the US has the luxury of distance, European countries cannot ignore such a toxic mix of geopolitical rivalry, extremism, and human suffering on their borders. Some European Union member states recognise the importance and urgency of committing to a stabilisation effort; others are still too complacent.

In Iraq, neither the EU nor any of its member states will be the leading external players. There are, nevertheless, openings to bolster Iraqi security forces and provide willing political actors with expertise on capacity-building and on decentralising power. Member states that have supported the anti-ISIS coalition can now shift their efforts into immediate and longer-term stabilisation efforts.

In Libya, there is more space for Europe to play a lead role by using existing United Nations Security Council resolutions and UN-backed agreements. Economic stabilisation and mediation, two issues on which the EU has some leverage in Libya, could play a key role in avoiding a new escalation between the forces that support the government in Tripoli and Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA).

As crucial military operations against ISIS in Mosul and Sirte near their end, this paper looks at where the EU and its member states can play a meaningful role in dealing with the coming challenges. In the case of both Iraq and Libya, the paper proposes recommendations for how the EU and its member states can develop an effective stabilisation policy. It concludes with four over-arching principles for European actors to follow throughout the post-ISIS space in the Middle East and North Africa, including in Syria.

Iraq: The post-Mosul conundrum

The ‘Battle for Mosul’ will likely mark the end of ISIS’s territorial control in Iraq. How its aftermath is managed will be a turning-point for Iraq: as one senior official in the Iraqi prime minister’s office said, the country will either “start a new chapter of political discourse and improvement, or it will implode into a new state of civil conflict”.[1] This risks giving new space to extremist groups like ISIS.

Since the rise of ISIS, issues of terrorism and migration have stayed at the top of the agenda throughout Europe. Stabilising Iraq has therefore become critical for political stability in Europe itself. Europeans have focused their efforts on two areas. First, EU member states (notably the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Germany, Spain and the Netherlands) have supported the US-led Global Coalition against ISIS through military assistance, weapons transfers to Peshmerga forces, training for Iraqi security forces, on-the-ground military advisers, and de-mining efforts.

Second, the EU and its member states have provided considerable financial aid to the UN’s stabilisation and humanitarian programmes to facilitate the return of internally displaced persons (IDPs) to newly liberated areas.[2] European member states make up half the donors to the United Nations Development Programme in Iraq and together are the biggest donor.[3]

Despite international financial support, the struggle against ISIS and the fall in the oil price have drained Iraqi resources.[4] Persistent corruption and economic mismanagement have added to those woes and led to a grave economic crisis. Continued economic downturn will further strain the ability of the Iraqi central government to deal with post-ISIS security and political challenges and to meet the demands of the country’s growing youth population.

The military defeat of ISIS in Iraq will provide an opportunity for European countries, particularly those in the Global Coalition against ISIS, to assist in reversing or at least containing the trend of crisis engulfing the country, to build a more inclusive and sustainable political order, and to shape the conditions to make it difficult for ISIS to return.

The rise and fall of ISIS

Among the many factors that allowed ISIS to occupy around one-third of Iraq in June 2014, two stand out.[5] First, the growing marginalisation of Iraq’s Sunni communities, particularly under former prime minister Nuri al-Maliki’s heavy-handed securitisation of the country’s political life. Second, the systemic corruption within the Iraqi security services and state institutions that enabled ISIS to capitalise on the Sunni sense of disenfranchisement.[6] The worsening civil war next door in Syria provided further fuel for ISIS to establish its self-proclaimed caliphate across both Iraq and Syria.

The fall of Mosul, and the ISIS threat to Baghdad in 2014, exposed the fragilities of the Iraqi security forces (ISF). The delayed military response from the US to the growing threat posed by extremist groups in the lead-up to the ISIS offensive toward Mosul also created security vacuums. The US had wanted to see movement on political reforms from Maliki before providing him with military support. But Iranian influence grew in ways that combined to allow ISIS to exploit the fears of Iraqi Sunnis and step in as an actor to fill the vacuum of security and provide basic state services to local communities.

Two years on, the situation of the Sunni communities in Iraq is dramatically different. Senior Sunni figures today acknowledge that ISIS was initially viewed by some communities and politicians as a welcome ‘liberation’. There was an initial marriage of convenience between Islamist jihadists and Baathist insurgents that led to the capture of Mosul. But soon, “ISIS had the Baathists for lunch in Mosul.”[7] The ISIS-Baathist split, along with ISIS’s brutal rule and the displacement of millions of Sunnis from their homes, left these communities in Iraq – along with many other minority groups – devastated.[8] The social fabric that initially supported ISIS has frayed, with many Sunnis now taking up arms to join the fight against the group.[9]

Factions in Iraq that had long competed against each other responded to ISIS’s advance by working together against a common enemy. The military cooperation between various Iraqi forces, most recently in Mosul among Iraq’s federal forces, Kurdish fighters and various Shia, Sunni and other paramilitary groups, is unprecedented. In November, Iraq’s Hashd al-Shabi, known as Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF), closed off all available land routes between Mosul, ISIS’s last stronghold in Iraq, and Raqqa, the group’s de facto capital in Syria. The PMF also teamed up with the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) Peshmerga to encircle Mosul and prevent access to ISIS-held territories in Syria.[10]

These forces have benefited from strong US and Iranian military backing and de-confliction. The military success of US-backed and Iranian-backed Iraqi forces has, in turn, given confidence to more Iraqis that ISIS can be defeated. The current optimistic mood in Iraq – on the military front at least – stands in stark contrast to the fear that gripped the nation in the summer of 2014.

These are all encouraging developments but it remains to be seen if this cooperation can continue into the political sphere once ISIS is defeated. Cooperation between external, local fighting groups and the ISF will also be needed in the security realm if ISIS doubles down on its large-scale terrorist attacks and adopts more guerrilla warfare tactics once it has lost its territorial control.

There is, however, some room to be optimistic. As one senior Western official explained, “Sunni communities, for example those in Anbar, have become very practical and now acknowledge they have to accommodate the central government who liberated them from ISIS.”[11] Fundamentally, Sunnis, Shias and every other ethnic or religious faction in Iraq have similar demands from their leaders: security, services, dignity and a state based on equal citizenship.[12] In parallel to a political roadmap along these lines, it will be crucial to ensure that IDPs are resettled, destroyed cities are rebuilt, and reconciliation efforts are made in order to prevent retaliatory attacks and revenge killings.

A post-ISIS race for control?

Despite promising signs on the anti-ISIS military track, one of the biggest threats facing Iraqi security is the likelihood that new internal conflict among, and within, Iraq’s power factions will emerge the day after the guns stop pointing at ISIS. This is a fear shared by both Iraqi and Western officials in Iraq.[13] As one Western official based in Baghdad suggested, the test case for how these competing agendas are balanced, and how the shattered community is pieced back together, will be in Ninewa, Iraq’s most ethnically diverse province and home to Mosul itself.[14]

The military actors involved in Mosul’s liberation – Iraqi federal forces, Kurdish Peshmerga, state-sponsored paramilitaries led by Shia forces and those aligned to local Sunni and minority groups – each come with different political visions for how the province should be governed after ISIS is defeated. According to one senior Sunni politician, while an agreed military plan exists, every group involved in the military campaign has “its own plan B” for what comes next.[15]

With respect to Ninewa, senior officials interviewed for this paper in Baghdad outlined that the central government seeks to have Ninewa retain its current provincial boundaries but with greater devolved powers.[16] In contrast, Mosul’s former governor, Athil al-Nujaifi, an influential figure who commands a Turkish-trained paramilitary force, wishes to transform Ninewa into a separate semi-autonomous region, which would give it more influence and power vis-à-vis the central government.[17] The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) would prefer to see Ninewa province broken down into three smaller provinces – which would create more amenable and manageable neighbours.[18]

The role and ambition of local Sunnis in Mosul, and elsewhere in Iraq, is not fully understood by politicians in Baghdad or by Western governments. There is a handful of local Sunni tribal leaders, fairly unknown beyond their neighbourhoods, who are now seen as the legitimate representatives within those communities.[19] Both Sunni leaders and Western officials agree that these local leaders, who emerged during the period of ISIS rule, are, along with more traditional Sunni tribal leaders, likely to have a critical role in working towards peace and reconciliation efforts at the local level.[20]

Besides competing political visions, there is growing concern among Iraqi and Western officials that various military groups will seek – in competition with each other – to impose a new local order through the barrel of a gun, and one that may not be favourable to local Sunni interests. These fears extend particularly to some forces that currently fall under the PMF umbrella, which in other cities have been accused of pursuing a sectarian agenda.[21]

After the fall of Mosul in 2014, the PMF was viewed by the Iraqi central government and authorities in Najaf as a necessity during a time of crisis to supplement the conventional armed forces. While the PMF is dominated by Shia forces, it also comprises fighting units from Iraq’s Sunni, Kurdish and minority communities.[22] The total number in the PMF is now estimated to range from 45,000 to 120,000, though a large number of these are “ghost warriors” who are paid but are not actively engaged in countering ISIS.[23]

In 2014, Grand Ayatollah Sistani, the highest Shia authority in Iraq, called on Iraqis to take up arms and help the security forces defeat ISIS. Now he is expected to issue a follow-up fatwa after the battle for Mosul calling for the PMF to be demobilised.[24] The Iraqi prime minister’s office is also making efforts to more formally integrate the PMF into the official security forces. Nevertheless, some of these fighters may refuse to integrate in this way or resist demobilisation.

Some strands within the PMF, particularly those loyal to Maliki and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), may resist attempts, especially those backed by Western powers, to curtail their role. The Iraqi parliament passed legislation in November that effectively transformed the PMF into a legal entity. This is a positive step in folding the PMF into state command structures.[25] But it also risks establishing a permanent security architecture under the heavy influence of several competing powers outside the central government. They are likely to clash with one another at local level and challenge the state’s monopoly on the use of violence.[26]

Further complicating the future political and security landscape in Iraq will be the position taken by regional actors such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. These countries will undoubtedly continue to seize opportunities to secure their regional interests by playing local actors off against one another. As one senior Iraqi politician described it, “Iraq is not an actor but a stake” for regional powers.[27]

Iraqi officials generally accept, albeit begrudgingly, that Iran and the US will retain a high degree of influence over the future of Iraq. But they are split on the role of Turkey. The central authority in Baghdad broadly views Ankara’s moves as foreign intervention, with the ambition to “gain benefits over Iraqi oil reserves and resources” in Mosul.[28] Other officials, however, acknowledge that Turkey needs to shore up its own border security given the increased presence in Iraq of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Both Turkey and the US consider the PKK a terrorist organisation. Some Iraqi and Western officials also see Turkey as a necessary balancing force to the Iranian presence in the country.

The city of Tel Afar provides an example of how many of these regional and internal rivalries might come together to produce potential post-ISIS conflicts. Tel Afar lies in strategic terrain between Mosul and the border with Syria, effectively connecting the two sides of the ISIS caliphate. Its Shia inhabitants, who either fled or were killed by ISIS, are now looking to return under the protection of Shia-led paramilitary groups. Meanwhile, Turkey has declared itself as the external protector for Tel Afar’s Turkmen population, which led to harsh rhetorical exchanges between the Turkish president and the Iraqi prime minister, Haider al-Abadi.[29]

Iraqi Sunni communities and some Gulf Cooperation Council states fear that the presence of these Shia groups with links to the IRGC means that Iran is seeking to gain control over Tel Afar as a means of securing a new land corridor into Syria.[30]

Intra-factional divides

Besides local-level politics, there are also deepening tensions at the national level over who controls Iraq’s central state institutions. Iraq’s factions managed to bridge ethno-sectarian divides and work together to defeat ISIS, but intra-ethnic and intra-sectarian rivalries nonetheless deepened during the struggle.

Within the Shia camp, competition between the different political blocs has intensified between those remaining loyal to the Dawa party formerly led by Maliki (and now by Abadi) and those backing Muqtada Sadr, who has fiercely opposed Maliki’s influence in Iraqi politics. But an even greater danger facing the Shia camp is the rivalry within the Dawa party itself between Maliki and Abadi. The current prime minister’s political weight in Baghdad is weak relative to Maliki’s, who is often described in Iraq’s Shia political circles as the “king-maker”.[31]

Iraqi Kurds, long seen in the West as the most reliable and stable political bloc, are also facing internal divisions, between the KDP and the rival Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). The KDP and the PUK form a coalition government in the regional capital of Erbil, but they have increasingly diverged on the question of Kurdish independence. The KDP generally supports separation from Iraq, while the PUK has generally been more closely aligned with Baghdad. The KDP has a positive relationship with Turkey, which has also made it much more wary of the presence of the PKK, while the PUK Peshmerga openly fight alongside the PKK. Given these dynamics, the growing presence of both Turkey and the PKK in Iraqi Kurdistan has greatly complicated intra-Kurdish divides.

There is also political deadlock currently. The regional parliament in Erbil has not convened in over a year. The PUK increasingly questions the legitimacy of Masoud Barzani, who has been president since 1992 and whose already-extended mandate expired in August 2015.[32] There is a growing perception among PUK members that Barzani and the KDP are receiving arms and funds from the West while turning a blind eye to worsening economic and political conditions.[33] One senior European official working closely with the KRG described intra-Kurdish frictions as “higher than witnessed in the past two decades” and “an invitation for outside forces to mobilise”.[34]

But, despite the intra-Kurdish and intra-Shia divides, it is the Sunni community in Iraq that suffers from the greatest leadership crisis. Divisions among Iraq’s Sunni communities have grown over the past decade, since the collapse of the Baathist regime in 2003. They have been exacerbated by the lack of a powerful religious Sunni authoritative figure such as the Shia have in Grand Ayatollah Sistani.

An Iraqi Sunni representative explained that after the experience of ISIS, the “fabric of Sunni society is even more divided, there is no political leadership and no strong religious authority to act as unifying reference, let alone to represent the community in Baghdad. Sunnis do not have the same experience of political organisation as Kurds and Shias. The Kurds and Shias have mediators from US and Iran, but no one is reconciling the Sunnis.”[35]

Senior Sunni politicians also speak of a growing disconnect between Sunni political elites who live outside the country and the local communities that they claim to represent.[36] Exiled politicians do retain a degree of influence through their extensive financial networks and economic influence with some Iraqi Sunni factions and Western governments, but the disconnect is increasing as Sunni local actors on the ground in Iraq risk their lives in the fight against ISIS.

The decentralisation imperative

Despite these divides, there is one issue around which there is increasing consensus within Iraqi political blocs and which should become a focal element of any post-ISIS political plan: decentralisation of power away from Baghdad. According to Abadi’s close aides, the prime minister believes, unlike his predecessor, that “decentralisation would strengthen the country and not weaken it”.[37] As witnessed with the past year of civil protests across Iraq, sit-ins at Baghdad’s Green Zone and the takeover of the Iraqi parliament in April, local communities – both Sunnis in the western and northern regions as well as Shias in the south – are demanding more accountability and empowerment. Such efforts are also being supported by the US, which has begun to step away from large-scale reconciliation at a national level to focus on devolution of power to provincial authorities.[38]

However, there is also opposition from Maliki and his allies in Baghdad to the decentralisation agenda. It will be important to learn from previous attempts in this regard since 2003. These were largely unsuccessful because of resistance in Baghdad, particularly under Maliki who believed in strong central government structures. When decentralisation was attempted, Baghdad devolved administrative duties without financial support or providing adequate security in those provinces, leaving many local institutions bankrupt and unable to provide basic services.[39]

Steps towards decentralisation can be pursued along existing provincial boundaries in Ninewa, Diyala, Basra and Salahaddin, instead of falling into the trap of pushing for the creation of regional strongholds in Iraq along ethno-sectarian lines. Attempts to pursue decentralisation in any of these areas will need to be closely coordinated between local leaders and the Iraqi central government to identify the partners and mechanisms to devise and implement devolved powers. International partners must also work on building capacity on the ground at a local level to make sure provinces and departments can effectively run their administrations so that decentralisation is not promoted for its own sake.

Although the intra-sectarian and intra-ethnic divisions outlined in this paper are a cause for concern, one senior Shia politician suggested that the new dynamic could actually open up an interesting period of political experimentation with various actors “forming cross-sectarian alliances with others based on policy and not race or sect.”[40] Such developments could create a healthier political process and may be even pave the way for a majoritarian government and strong opposition in parliament

Recommendations: Iraq

The fall of ISIS in Iraq is imminent, but the country will remain fragile and dangerous. The EU and its member states have a distinct interest in ensuring stability in Iraq. To protect this interest, they should seek to assist Iraqi leaders with devising an inclusive political roadmap. This should address local and national issues, including averting new conflicts that might arise between local groups and regional actors competing for influence in the post-ISIS space. It should understand the tensions between and within Iraq’s main communities, and should seek to be a comprehensive and long-lasting framework covering politics, the economy and security.

Refocus from humanitarian aid to economic development

The EU and its member states should agree on a timeline to gradually shift existing economic stabilisation funds for Iraq away from an immediate focus on provision of humanitarian aid and services towards development programmes that aim to promote job creation and long-term investment in the country. These efforts should be led in close coordination with the United Nations and the International Monetary Fund, which have both had experience identifying the most effective organs within the central government in Iraq as well as local actors to implement economic projects across the country.

Development projects should target Iraq’s youth population in the provinces most devastated by the conflict with ISIS (notably in Ninewa, Diyala, Salahudin and Anbar) and those areas that have long been neglected by the Iraqi government (including the Shia-dominant Basra province). This would help the Iraqi central government and local provincial leaders to address the grievances of both Sunni and Shia communities and help reduce the cycle of radicalisation within the youth population. In this effort, EU member states should coordinate and reach consensus on clear targets for the Iraqi government in tackling mismanagement and corruption as preconditions for releasing economic aid.

It is critical to identify the right local leaders for implementing such efforts in coordination with Baghdad. Doing so will provide a way for Europe to dampen local tensions, build local capacity to manage economic development, and promote participation of competing parties.

Support decentralisation efforts led by Baghdad

In a bid to prevent a post-ISIS battle for power, European actors should support the Iraqi central government in its efforts to roll out a process of decentralisation. As a first priority, this support should aim to encourage local actors to constructively manage a political roadmap that can help stabilise Mosul, encourage the return of IDPs and set a positive precedent for rest of the country.

Given their own experience of decentralisation, many European countries can deploy their know-how and technical expertise to support the Iraqi central government, particularly the office of the prime minister, which wishes to develop models for devolution of power to give greater resources, powers and responsibilities to local provincial actors. There will undoubtedly be a degree of trial and error in this, and Europeans can assist local leaders to devise tailor-made systems based on the administrative, political, fiscal and security context of each province.

EU member states should be very careful in how they approach the sensitivities surrounding decentralisation and avoid giving the impression that they seek to create divisions in the country. The best means of doing so is to begin serious and frank discussions about the decentralisation model with the central government of Iraq.

At a later stage, as decentralisation efforts proceed with the central government, it will be necessary to enhance the capacity of local administrations to govern effectively and to cater for the economic and security needs of the local communities. This is where EU member states can play a pivotal role in building governance and infrastructure at the local level, which would better prepare communities to exercise and wield power once it is devolved from Baghdad.

Push for political progress within the KRG

There is a risk that European military assistance to the KRG will become increasingly monopolised by the KDP – and, in any case, there is a widespread perception within the PUK that this has already happened.[41] European states should be attentive to these risks and encourage improvements in the political conditions within the KRG. They should, for example, press for greater transparency in government spending and oil exports and for the resolution of the deadlock that has obstructed the convening of parliament for over a year. This should include public and private discussion with the KRG on conditionality and benchmarks that will be placed on economic and military assistance provided to it by EU member states.

Reform the security sector

The continued terrorism threats in Iraq will remain a high priority for Baghdad and Europe. After Mosul, the effort will shift from conventional military conflict against ISIS towards counter-terrorism operations and policing.[42] Although the public now has more confidence in the Iraqi security sector following the successful ISF-led liberation of Ramadi, Tikrit and Fallujah, major challenges remain for the ISF – not least how to integrate the PMF and how to address endemic corruption.

In the realm of security, European member states should work together with the central government through increased financial aid and training to bolster and professionalise the Iraqi security and intelligence apparatus. The immediate focus of these efforts should be to build public confidence in the security forces by deterring large-scale terrorist attacks in Iraq and filling security vacuums that could allow ISIS or other extremist groups to gain a territorial foothold in the country.

Fill potential gaps in US-Iran channels

President-elect Trump’s trajectory on Iraq remains unclear, but there is a likelihood of a precipitous downturn in the US-Iran channels of communication that were developed in the course of the nuclear negotiations. In this instance, European member states such as the UK, France and Germany will become important players in promoting continued US-Iranian de-confliction in Iraq, in particular defusing areas of tensions between Tehran and Washington that could provoke over-reactions against one another’s military positions in Iraq.

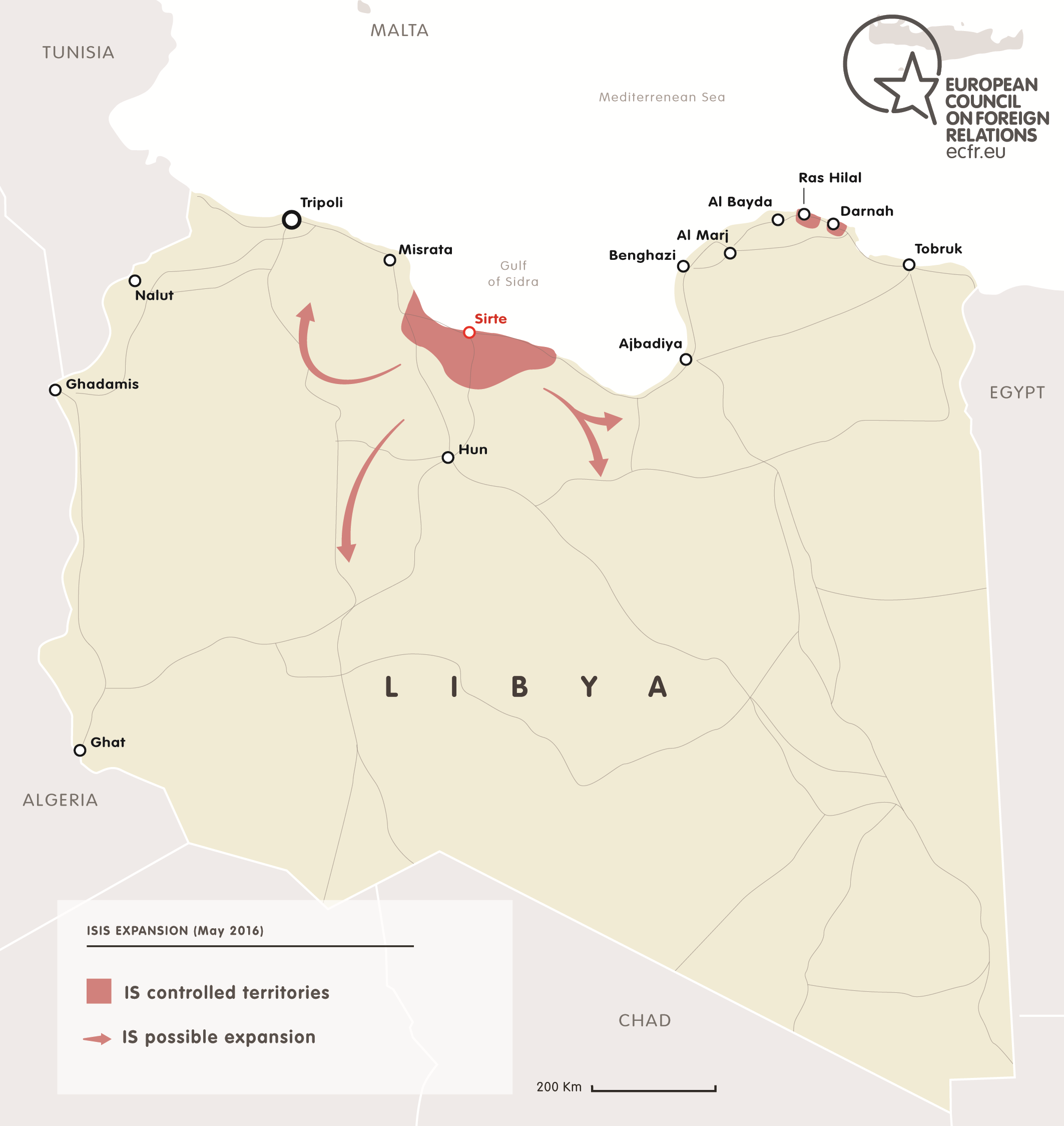

Libya: Some opportunities, many challenges

The establishment of an ISIS ‘emirate’ in the central Libyan city of Sirte, stretching for 200km along the country’s Mediterranean coast, was a major reason for concern in Europe and the US from early 2015. Just 250km from the EU, Libya is important for Europe mostly as a conduit for migrants and as a potential safe haven for terrorists.[43]

The battle to liberate Sirte from ISIS started in May 2016. On 7 December 2016 the Libyan Presidential Council declared that Sirte had been liberated. But, as in Iraq, the end of ISIS territorial control is only the beginning. European policymakers need to maintain a strong focus on stabilisation or risk recreating the conditions that allowed ISIS to emerge in Libya in the first place. At stake is the future balance of power in the country, the continued existence of the Presidential Council in Tripoli, and the possibility of the emergence of new jihadist organisations; in short, the very survival of a political order which can provide stability.

The roots of ISIS’s defeat (and of its possible comeback)

ISIS in Libya was never able to extend its territorial control beyond Sirte and the city’s mostly uninhabited surroundings. It was perceived as a foreign occupying force, as many of its fighters came either from ISIS-held territory in Iraq and Syria or were foreign fighters from other parts of North Africa. It did not win hearts and minds and therefore lacked both the fighters and the functionaries (to build and run a state) to expand beyond Sirte. Gaddafi loyalists, unlike Baathists in Iraq, did not side en masse with ISIS. But this only adds to the current challenge, as the integration of former Gaddafi loyalists into Libya’s politics and security is even more important in order to ensure they do not change their minds about the course they chose to take.

From a counter-terrorism perspective, the most important challenge in Libya now is twofold. First, containing the ripple effects in Libya and in the region caused by the ‘dispersion’ of ISIS fighters. In response to losses in Sirte, many of them have travelled in different directions within and beyond Libya: some of them south towards Sebha; some towards Sudan and south-eastern Libya; a third component towards Sabratha and the border with Tunisia. While Tunisia and Algeria are coordinating to deal with this threat, there is no equivalent with Libya’s other neighbours, particularly Egypt, Chad and Niger. This will require Western and regional intelligence and security cooperation for which the EU and its member states most involved in the Sahel (France, Spain, Germany) should push.

Second, the collapse of ISIS is unlikely to mark the end of jihadism in Libya, which has existed for decades.[44] Different groups may try to take advantage of ISIS’s difficulties, and the organisation itself could try to mount a comeback as a purely terrorist group or an insurgency. The shortage of fighters and funding could change if Libya’s legal economy collapses during 2017. This would mean a ‘free for all’ for the services of the many militiamen currently paid by the government. Such a situation would lead to a steep rise in the informal sector, usually a fertile breeding ground for jihadism in North Africa and in the Sahel where the line between jihadism, smuggling and organised crime is ever more blurred.

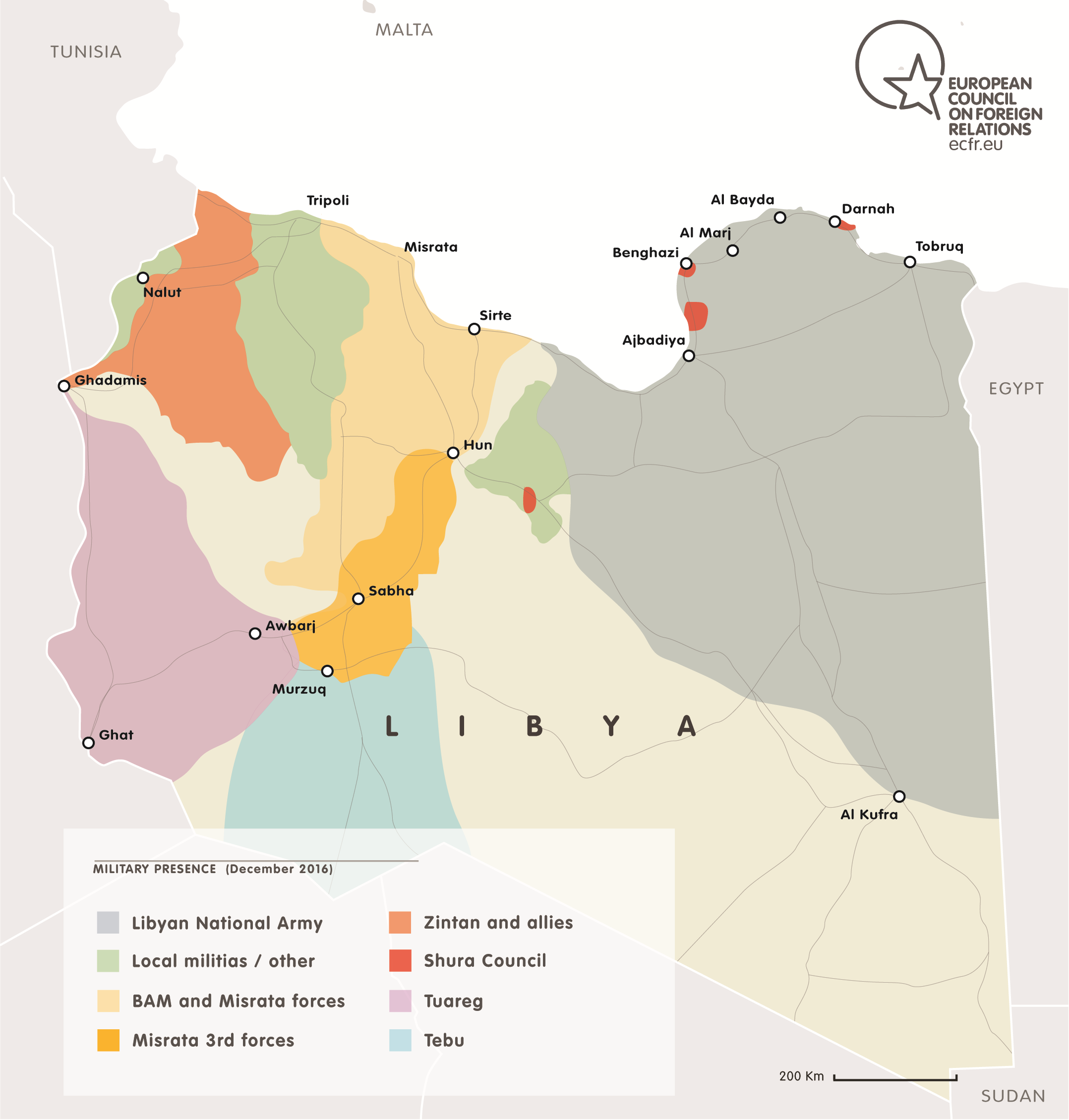

The rival forces which fought ISIS

Another threat for Libya and Europe is the possible clash between the forces that fought ISIS in Sirte and those that fought it in Benghazi. The former nominally side with the UN-backed Presidential Council headed by Faiez Serraj while the latter fight under the banner of the LNA of anti-Islamist, Egypt-backed Haftar and the rival institutions based in the eastern cities of Beyda and Tobruk. Both governments, in Tripoli and in the east of Libya, used the battle against ISIS to build up their credentials with the outside world: Serraj has received US, UK and Italian backing while Haftar has backing from Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, and, increasingly, from Russia.

This Egyptian-UAE-Russian support for Haftar has strengthened his military position and also diminished the incentive for him to join a power-sharing agreement. Haftar, who from the start never accepted the Libyan Political Agreement, now enjoys such a position of relative strength in eastern and central Libya that he can one day consider attempting to conquer Tripoli without needing to strike an agreement with the forces that back Serraj. External support for his endeavours was never conditioned on his acceptance of the Libyan Political Agreement. This ultimately undermined the agreement.[45]

The battle in Sirte was fought under the umbrella of the Bunyan al-Marsous (BAM) operation, which is composed mostly of militias and fighters from the city of Misrata along with other groups. In the initial stages the Petroleum Facilities Guards conducted the offensive from the east; some Salafists joined BAM, although they never merged into its command structure; small groups from militias of other western Libyan cities also participated in the operation.[46]

BAM received substantial support from Western countries: the US conducted more than 300 air strikes supporting it since August last year; British special forces were reported to be advising Misratan forces; and Italy established a field hospital in October 2016 for Misratan fighters, protected by a hundred Italian paratroopers.

The goal of these external supporters of the BAM operation was not just to fight ISIS but also to respond to specific requests coming either from Serraj, the prime minister, or directly from the city of Misrata. Yet, while the intention of these supporters was to strengthen the government created by the UN-backed Libyan Political Agreement, the operations in Sirte showed how little this government was actually able to deliver to the forces on the ground in terms of weapons, money or political support – all things the Serraj administration is severely short of. In the end, armed groups from Misrata did most of the heavy-lifting, with some help from foreign forces.

The battle in Benghazi was a different story. ISIS emerged out of a messy local and national civil war that originated with targeted assassinations in 2013 and then evolved into open fighting with the beginning of Haftar’s Operation Dignity in mid-May 2014. The rogue general, who in the meantime had been appointed head of the armed forces of the government sitting in Tobruk, received increasing support from the UAE and Egypt. In January 2016 this was supplemented by the strategic assistance of a limited number of French special forces which helped the LNA to push back its opponents (including ISIS) from many of Benghazi’s neighbourhoods. More recently, Russia has built up its political support for Haftar through several official meetings while its military support is still unofficial.[47]

While the UN-backed political agreement was meant to merge Haftar’s Tobruk government into the Presidential Council in Tripoli, one of the reasons this never happened was because Haftar resisted attempts to establish any civilian oversight over his activities. External support, especially from France, may have been intended as a purely counter-terrorism element against ISIS.[48] But its political consequences included strengthening Haftar’s hand with both his ‘domestic’ opponents and rivals in eastern Libya and vis-à-vis the government in Tripoli. (See ECFR’s ‘Quick Guide to Libya’s Main Players for more on the situation in Libya[49]).

In the summer of 2016, Haftar studiously avoided any direct confrontation with ISIS in Sirte while building up his forces around the oil terminals east of the city. He eventually managed to take them over, mostly through tribal alliances and without extensive fighting, handing their management over to the National Oil Company in Tripoli in September. Meanwhile, Misratan forces were exhausted by the anti-ISIS fight in Sirte and had little appetite for a direct confrontation with him. This gave many Libyans the impression that military and political momentum was on the side of the general, although Haftar probably never had the military strength to conquer western Libya

The potential for a new escalation

ISIS’s demise in Libya will likely bring the situation back to where it was before its rise in 2014 – namely, a struggle between forces in the west of Libya gathering around the militias from Misrata (now backing the government in Tripoli) and the mostly eastern forces fighting under the LNA. The latter have gained momentum since September while the former are exhausted by the fight against ISIS in Sirte. This lack of balance in forces and momentum could lead Haftar to move westwards, clashing with both Islamist and less Islamist forces that view him as an existential threat.

Recent clashes between the LNA and Misrata’s 3rd force around Sebha further demonstrate the dangers of escalation in Libya’s south. Eastern Libya could also be a potential flashpoint as different forces in Benghazi, Ajdabiya and Derna react against Haftar’s hegemony: the Benghazi Defence Brigade, the Benghazi Shura Council, its equivalent in Ajdabiya, the Mujahedin Shura Council in Derna to name but the most important ones.

But Haftar’s strategy is not purely military. He is using a replica of the strategy that brought him victory in the oil fields: local political alliances that allow him to avoid direct armed confrontations. Tripoli is part of Haftar’s plans, too. The capital is unlikely to be the subject of significant fighting but would more likely “collapse from within” because of increasing divisions between militias siding with Haftar and diehard anti-Haftar groups.[50]

This would leave the LNA in a position to seize the mantle of being the only reliable institution left in Libya. Any attempt by it to claim to be truly ‘national’ is questioned by many both inside and outside of the country, including members of the military in the west and south of Libya who are not supportive of Haftar. Ultimately, Haftar’s strongman approach and the reaction it might create both in western and eastern Libya could contribute to a military escalation, rising anarchy or both.

The threat to Europe from this ‘escalation and/or anarchy’ scenario is obvious: with violence rising in the capital and in western Libya, it would become impossible to establish embassies and any presence on the ground, while the UN-backed Presidential Council would become an increasingly unreliable partner. Ultimately, this government would still be an interlocutor for the EU, but its capacity would exist solely on paper, especially on migration management.

Should this scenario materialise, it would likely represent an environment conducive to the rise of jihadist groups, whether ISIS or another group.

Recommendations: Libya

The EU and the member states actively engaged in Libya should not aim for the unattainable goal of a fully functioning Libya. A more innovative strategy would focus on freezing the current conflict while pursuing an economic deal that would help avert a humanitarian crisis and a collapse of Libyan institutions. Avoiding widening conflict and possible state implosion is the key component needed to cement recent gains against ISIS and prevent it and other jihadist groups from returning.

The EU, and member states engaged in Libya, should be aware of their limits, but also of their potential. Some of the things that have to be done in post-ISIS Libya are in their toolbox: managing a post-conflict, divided polity; mediating an economic agreement; and mediating security arrangements.

Strengthen the political coalition behind Tripoli’s government

Tripoli’s Presidential Council is split between a majority of members that side with Serraj and other members, including Haftar’s representative Ali Gatrani, who are boycotting the meetings. However, the Presidential Council majority is struggling and lacks a real coalition of political and armed groups backing it besides the moderate elements in Misrata, which have increasing reservations about the government. The EU and its member states, through bilateral and multilateral mediation and engagement with Libyan political actors, could work to expand the coalition-backing unity efforts. This should include prominent politicians from all sides, including those normally associated with the anti-Islamist camp who now fear marginalisation if Haftar (and leaders of military groups more generally) gain the upper hand.

Even though, for the sake of simplicity, media and experts often refer to the Government of National Accord (GNA) as if it already exists, there is no such thing in place. Two different lists of ministers submitted by the Presidential Council majority were rejected in 2016 by the House of Representatives. On 7 December 2016 the UNSC urged the Presidential Council to submit a new list. This could be a new opportunity to give Libya a government and broaden the coalition supporting the Libyan Political Agreement.

This broadening would imply two things to be managed and approved by the Libyan Political Dialogue, which groups together all the different Libyan delegations that are party to the talks. First, a new annex to the Agreement, which would clarify the tasks of the GNA, focusing on the management of public services and the economy while drawing a clearer distinction between the government and the Presidential Council. Second, prominent politicians from all sides should join the GNA together with some technocrats – and Libya has some good technocrats, especially on the economy. This strategy would be based on ‘what works’, and it could be more effective than rewriting a completely new agreement, which could take months if not years.

Libya needs a more inclusive political compact and European actors can strengthen efforts in this direction. Political mediation in coordination with UNSMIL is crucial in this sense, including offering increased access and recognition to those politicians who play a more constructive role.[51]

Help Libyans build a decentralised state

Libyan local authorities are struggling but they are important in preventing conflicts, delivering public services and maintaining a minimum of state authority and presence. Particularly in areas that are nominally under the control of Presidential Council-aligned forces, municipalities are the only elected and fully legitimate institution. Some municipalities have played an important role in mediating ceasefires or even, in the case of Misrata, sanctioning a change of policy in favour of negotiations within the UN framework. Service delivery, which is one of the top priorities for ordinary Libyans, can only happen by involving municipalities in such a big and sparsely populated country.

The EU should help to:

a) unlock funds from the central government for municipalities, both through the economic dialogue meetings between the Central Bank, the Audit Bureau and the Presidency Council, and by more funding for the UNDP Stabilisation Facility;

b) encourage coordination, through bilateral contacts with Libyan authorities, and provide advice and recommendations on best practice;

c) promote capacity-building through ‘on the job training’ in Europe for Libyan civil servants. The European Committee of the Regions and national associations of local authorities, could be helpful in this regard.

The EU should also reject all attempts to replace elected mayors with appointed military governors – Libya needs more elected and accountable officials, not fewer.

Finally, the EU should consider whether it is worth revamping the ‘municipalities track’ of the UN-coordinated Libyan Political Dialogue, which the EU had previously taken care of and which brings together Libyan mayors to discuss the main issues facing the country.

Support deep reconciliation efforts

Even more than before, post-ISIS Libya will need concrete efforts on reconciliation, not just to heal the wounds of the past but to avoid future escalations. This is something that UNSMIL is already working on. EU member states should support its efforts with the provision of logistical support or ‘adopting’ tracks of dialogue similar to those pursued in the past by countries undergoing democratic transition, like Spain or Bulgaria. This could initially focus on confidence-building measures like the release of prisoners or the reopening of vital infrastructure and communications.

Pursue military de-escalation

The EU and its member states should support efforts to reach a military deal between different actors in western and southern Libya, focusing on de-conflicting mechanisms, military federalism between the different regions, and a joint effort to build accountable security services. Part of this deal would acknowledge Haftar’s position in the east while establishing different military regions elsewhere under the leadership of other commanders. One of the effects would be to contain any potential desire by Haftar to move westwards by showing that western and southern Libya are under the effective control of other leaders committed to building a national army and not an empty territory to be conquered. There are increasing signs of a convergence of interests between different armed groups in western and southern Libya. The EU could make it clear that once a military deal is reached within the framework of the unity government it would provide the same or even more support than previously given to the fight against ISIS.

Efforts to build a strong ‘security track’ led by UNSMIL have so far faltered because of the growing rift between the forces of Haftar and the other, less organised, forces that formally support the government in Tripoli. To avoid anarchy and prevent conflict if Haftar does move west, EU and member states should work in tandem with UNSMIL to encourage efforts to build de-conflicting mechanisms and strengthen the security arrangements in Tripoli and other key cities, such as Sebha in the south. This will include efforts to promote accountable police and security forces in the western and southern parts of Libya that are nominally under the control of Tripoli.

This would have the dual benefit of not prejudicing a settlement with Haftar’s forces in the east while also not holding the process hostage to any rejection of civilian oversight by Haftar. To this end, UNSMIL’s Security and Defence Department together with the EU’s Planning Unit should promote a dialogue between army officers from all over Libya in which they can discuss the future of Libya and of the military.

But, ultimately, European policymakers should stop claiming that Haftar needs to be part of the Libyan Political Agreement for it to move forward. It is now abundantly clear that he has no interest, given his momentum, in striking any deal. Instead, Europeans should engage more seriously with other actors to see how they can help stabilise and de-escalate the fighting in the parts of the country where they are present.

Conclude an economic deal to keep the country united

The release of LYD 37 billion as “Temporary Financial Arrangements” for the Presidential Council is good news but it is unclear if the government will be able to spend it across the whole country. The EU and its member states must give concrete support to a deal that saves the country from economic collapse while addressing the legitimate concerns of eastern Libya about marginalisation within a unified Libya. This would involve a bigger role for bipartisan technocrats, a shared budget and a working relationship between the different political and economic institutions. In order to build an ‘inclusive’ budget at times of great political polarisation, government expenditure should be built on common criteria: per capita funding (a big difference from the Gaddafi era), and provision of basic rights such as healthcare, education, water and electricity to all Libyan citizens regardless of whether they live in areas under its control or under the control of Haftar’s forces.

Since the London summit on the Libyan economy in October 2016, UNSMIL, the US and several European countries (the UK, France and Italy) have started to cooperate with the Libyan government in Tripoli and the major economic institutions to chart a way out of the economic crisis. Building on this, the process should involve as many political, social, military and economic actors as possible in order to work on some priorities: building a shared budget for all Libyans; preserving the independence of financial institutions; and strengthening the capacity of the government on fiscal policy by helping to build an effective Ministry of Finance and strengthening the Ministry of Planning. The EU itself should offer a budget assistance programme or help build an advisory board aimed at providing expertise to Libyan institutions.

Do not forget Sirte (and Benghazi)

Even before ISIS’s fall in Sirte, a number of post-conflict problems were clear. De-mining, humanitarian relief, and building the conditions for the safe return of IDPs are priorities not just for Sirte’s residents but also for the stability of the rest of western Libya. The EU has acted on these issues in the past in Libya, while the Netherlands has taken the lead on de-mining.

These efforts will need coordination. Furthermore, the city will need a great deal of political mediation and reconciliation between the different constituencies. The social fabric was torn asunder by the rise of ISIS and the capacity of local authorities needs to be built back up. An EU task force working in coordination with UNSMIL should provide support for reconciliation and the rebuilding of public service capacity in Sirte. This task force would help in two ways: providing UNSMIL and Libyan authorities with a single focal point on the European side when seeking assistance; and coordinating efforts by member states, pooling resources and avoiding duplication. The work of the UNDP Stabilisation Facility in Sirte and previously ISIS-held areas could be boosted with EU support, as recent funding for Sirte’s main hospital demonstrates. This would enable the presence of consultants, humanitarian assistance and some supervision of the activities conducted with the Libyan authorities.

Benghazi, too, will need significant reconciliation and reconstruction. While this may prove more problematic than in Sirte because Benghazi now falls largely under the control of Haftar’s LNA, which is not party to the Libyan Political Agreement, the EU should nonetheless provide help with humanitarian assistance and de-mining. This would, incidentally, also help to strengthen the case that the international community is impartial in internal Libyan political struggles.

Deal with regional powers and Russia through the UNSC, and set up an EU member state ‘contact group’

Over the past two years, the US and some large EU member states have successfully coordinated on Libya. Issuing joint statements and agreeing common positions on matters such as the lifting of the arms embargo or the independence of oil institutions has helped to reduce the appetite for escalation and zero-sum games by regional powers and their Libyan proxies. This may be more difficult under the Trump administration, which seems less eager to confront Middle Eastern autocracies. Further complicating matters, Russia has become increasingly vocal on Libya: while nominally supporting the Libyan Political Agreement, it has made clear that it sees a convergence of interests with Haftar in the fight against terrorism. This support further diminishes the incentive for Haftar to strike a power-sharing agreement, within or outside of the Libyan Political Agreement.

In this potentially difficult environment in which neither the US nor Russia are likely to be particularly helpful, it is all the more important that Europeans coordinate. The four EU countries sitting on the UNSC from January 2017 (the UK, France, Sweden and Italy) should create a contact group. Its main policy should be to preserve the ‘architecture’ of resolutions and agreements negotiated by the UN and approved by the UNSC over the past two years with the support of the US, Egypt and Russia. All of these countries might now adopt, or already have adopted, an approach different to the Europeans’ and contrary to European interests. The individual sanctions and the arms embargo regimes should be defended along with the Libyan Political Agreement, which should be amended but not scrapped altogether. These may all be imperfect tools but the situation without them would be even worse.

There is no doubt that these actions will be difficult, both in light of the likely priorities of the Trump administration, and because of the domestic problems of some of Europe’s larger players on Libya: the UK is focused on Brexit, the presidential election is approaching in France, while Italy is experiencing a renewed period of political uncertainty in the wake of December’s referedum.

But this is Europe’s moment: the EU and its member states have to address the issues described above because no one will do it for them. And the EU and its member states, when working to support positive trends among Libyans, can make a real difference. Defeating ISIS in Libya runs the risk of complacency, of thinking ‘job done’. But the problems of migration flows and security, which are live issues across the EU, will not disappear once ISIS does. They will only be properly addressed if Europeans can help Libyans to avoid new conflicts, create more functional state institutions, and support the economy.

After the caliphate: What should Europe do?

As difficult as they have been, the military operations to take on ISIS may turn out to be the easier part of the struggle. The initial focus of the Global Coalition against ISIS has so far focused disproportionately on the military dimension. While in the past year Libya has seen parallel political efforts, these have made only limited progress. Now that ISIS is on the ropes, the political track should be moved to the heart of the struggle against the cycle of violent extremism that gave birth to groups such as al-Qaeda and ISIS.

If Europe neglects this political track, it is likely to find itself at risk of another wave of regional instability and power vacuums on its eastern and southern borders.

An important lesson learned from the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the 2011 Libya intervention is that the post-conflict political process must be locally owned. However, the ISIS takeover of Mosul, and the group’s subsequent spread to Libya, also showed that the West cannot give up on regional political engagement. In the future, the EU and member states can and should be doing more to encourage the post-ISIS political transition in a direction that resolves the underlying issues.

In Iraq, a clear political opening will present itself after the military operations against ISIS wind down in Mosul. EU member states should be prepared to act quickly in providing security and economic aid to the Iraqi government in return for progress on a political roadmap which adequately represents and balances local needs. Moreover, the EU and its member states should be open to actively assisting the central government and local actors at a time when they appear to be more receptive to serious political engagement than at any time since 2003.

In the case of Libya, Europeans, particularly if they do manage a degree of policy convergence with the US, enjoy a decent degree of leverage over the warring factions. Achieving stabilisation and economic power-sharing should remain their priorities. There is now an ‘architecture’ of UNSC resolutions that includes the Libyan Political Agreement, an individual sanctions system, an arms embargo, and resolutions protecting the independence of financial institutions and preventing any single faction seizing oil resources for itself. This ‘architecture’ was built with the approval of all the other relevant powers, including UNSC members Russia and Egypt, which are currently supporting Haftar, the main rival of the UN-backed government. Preserving this ‘architecture’ should be one of Europe’s priorities.

Aside from the aforementioned Iraq- and Libya-specific recommendations, European policymakers should develop longer-term strategies on the post-caliphate territories, following four over-arching recommendations.

Build social and political coalitions

In the immediate aftermath of regaining formerly ISIS-held territories, social and political coalitions are needed to support de-escalation of local conflicts and build effective, inclusive governance on the ground.

In the past year, Libya has avoided full escalation because of a de-escalatory strategy carried out by the US, the EU and its member states. In Mosul, as the counter-ISIS operations draw to a close, the Global Coalition against ISIS is looking to similarly come together with the UN, the Iraqi central government and the KRG to sustain a contact group that can agree on how best to formulate and implement the post-ISIS governance and stabilisation efforts.

There is now a window of opportunity for the EU and its member states to contribute to stability by assisting with the development of decentralisation models that EU member states (like Germany, the UK and Austria) have grappled with already. This should include: devolving power to peripheries while strengthening the ‘social contract’ around central governments; working on reconciliation and on the sharing of economic resources; and mediating between different political, military and ethnic groups.

A common European framework for this engagement becomes even more necessary at a time when the new US administration is likely to take a step back from leading on political engagement.

In this light, existing positions of strength should be examined. In preserving the UN ‘architecture’ on Libya, for instance, the four EU member states on the UNSC should coordinate closely. If one also looks at Iraq, Germany should be added to the list to ensure that positions are coordinated and, where possible, European leverage is increased. Despite its own new realities in the aftermath of the EU referendum, it is in the UK’s interest to lean towards a European framework that focuses on political tracks. Furthermore, this is something in which the UK has unique expertise.

Maintain military involvement

While recognising the need to place greater focus on the political roadmap after ISIS loses territorial control, Europeans will also need to continue ongoing military involvement and counter-terrorism efforts to boost local security. This will include support, assistance and training for local forces in order to maintain the defence lines against ISIS as well as against other extremist groups.

Commit to a decade-long framework for stabilisation

To bring lasting stability in countries that were formerly partly occupied by ISIS, the EU and its member states should commit their financial backing and diplomatic weight to a decade-long framework for stabilisation.

This long-term framework should entail economic support contingent on progress in governance and reconciliation efforts. It should be devised in close collaboration with central governments and local leaders to address unresolved problems such as endemic youth unemployment, the distribution of oil wealth, and post-conflict reconstruction. In the case of Libya, European economic ‘investment’ would be minor when compared to the size of the country’s economy as a whole. But if harnessed through sustained political and diplomatic efforts, it could turn Libya’s economic assets into a resource to promote development in North and sub-Saharan Africa (the assets of the Libyan sovereign wealth fund are estimated to be worth $67 billion).

Set out and defend European interests

In undertaking such actions, Europeans could find themselves at odds with their regional allies who, for different reasons, see the post-ISIS situation as an opportunity to further their zero-sum agendas rather than as the decisive moment to bring about stabilisation.

But Europe needs to draw a line in the sand regarding its own interests. The fact that the new US administration cannot be taken for granted in these efforts is one more reason to put a European strategy in place. No one will defend Europe’s interests except for Europe itself. This option becomes all the more realistic if it is combined with a convergence with the new US administration in all relevant forums.

Lessons for Syria

Finally, a positive political trajectory in the Iraqi and Libyan theatres is not only a necessary component for the stability of each country, but also for the wider success in the battle against ISIS elsewhere. This is pertinent in Syria where over the past year ISIS has also been squeezed by coalition forces, US-backed Syrian Defence Forces, Turkey, Russia and the Syrian Arab Army. Just as in Iraq and Libya, this has resulted in the loss of territory for ISIS and a land-grab between competing fighting forces in Syria.

A post-ISIS Syria is a more distant prospect than in Iraq or Libya. But it will likely happen eventually, and, in the case where opposition forces and the Assad regime continue to escalate violence, Europe’s choices will be limited. While the principles outlined above will be very difficult to apply in the case of Syria, Europe can begin preparing a strategy to pursue for post-conflict stabilisation based on these broad principles, developing them in response to the changing facts on the ground in Syria.

In this endeavour, the EU and member states engaged in the International Syria Support Group should press for meaningful political discussions to be restarted. This should entail a focused effort to understand the stances of local actors in Syria – ranging from the regime in Damascus, to the Kurds and rebel groups – on the questions of stabilisation and devolution of power. This can be the starting point for serious political negotiations in the aftermath of the military phase of the conflict in Aleppo.

Iraq, Libya and Syria each need bespoke strategies. Yet there are clear overlaps in the types of challenge presented by their post-ISIS future, including actions that can be useful in preventing state breakdown and extremism in the region. If Europe is serious about playing a more effective and relevant role in a conflict-ridden region on its doorstep, it needs to step up its political and economic engagement with all relevant local leaders. This ought to be done with a sober acknowledgment that getting the politics right in the post-ISIS period requires long-term commitments.

Footnotes

[1] Interview with senior Iraqi official at prime minister’s office, Baghdad, October 2016.

[2] For more see, “The European Union Announces 194 million Euro to Support Iraq at Washington Pledging Conference”, 20 July 2016, available at http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-16-2564_en.htm.

[3] Comments made by senior EU official at private meeting, Baghdad, October 2016.

[4] Interview with senior Iraqi official at prime minister’s office, Baghdad, October 2016.

[5] See generally, Patrick Cockburn, The Rise of Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution, (Verso Books, 2015).

[6] As articulated by a range of Iraqi Sunni, Kurdish and Shia officials and political advisers interviewed for this paper in Najaf, Baghdad, and Erbil, October 2016.

[7] Interview with senior Iraqi politician extensively familiar with national security in 2014, Baghdad, October 2016.

[8] Interview with senior Iraqi Sunni parliamentarian, Baghdad, October 2016.

[9] Interview with senior Iraqi Sunni official, Baghdad, October 2016.

[10] See Isabel Coles et al, “Kurds, Shi’ite fighters to coordinate after sealing off Mosul”, Reuters, 24 November 2016, available at http://in.reuters.com/article/mideast-crisis-iraq-idINKBN13J0X1.

[11] Interview with senior Western official, Baghdad, October 2016.

[12] As articulated by a range of Iraqi Sunni, Kurdish and Shia officials and civil society actors interviewed for this paper in Najaf, Baghdad, and Erbil, October 2016.

[13] There was unanimous agreement about this among Iraqi political leaders and civil activists, in addition to Western officials interviewed for this paper.

[14] As stressed by Iraqi Kurd, Shia and Sunni leaders in addition to Western officials engaged in the country.

[15] Interview with senior official from Mosul, Erbil, October 2016.

[16] See also “Abadi promises Mosul leaders decentralized governance after liberation”, Rudaw, 26 July 2016, available at http://rudaw.net/english/middleeast/iraq/260720161.

[17] See Shonam Khoshnaw, “Athil al-Nujfai: we must create a region in Ninewa with its own constitution and self-administration”, Rudaw, 26 October 2016, available at http://rudaw.net/arabic/kurdistan/261020164.

[18] See Delshad Abdullah, “Barzani’s scenario for Mosul after ISIS: division into three provinces’, Al-Sharq al-Awsat, 7 September 2016, author’s translation.

[19] Interview with senior representative of Iraq’s Sunni community engaged in reconciliation efforts in territories liberated from ISIS, Baghdad, October 2016.

[20] Interview with senior representative of Iraq’s Sunni community engaged in reconciliation efforts in territories liberated from ISIS, Baghdad, October 2016. This point was also stressed by senior Western officials in Iraq during interviews in Baghdad, October 2016.

[21] Amnesty International, “Iraq: Punished for Daesh's Crimes Displaced Iraqis Abused by Militia and Government Forces”, October 2016, available at https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde14/4962/2016/en; see also Human Rights Watch, “Iraq: Ban Abusive Militias from Mosul Operations”, July 2016, available at https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/07/31/iraq-ban-abusive-militias-mosul-operation.

[22] Christian and Ezidi minorities were specifically targeted and devastated by the creation of the ISIS caliphate. In response, they have now deployed military units, some of which fall under the PMF, to protect their lands from future mass atrocity campaigns against them.

[23] There are no verifiable figures for the number of PMF fighters. The lowest number provided to the authors by one senior Iraqi politician was 45,000 fighters. However other senior Iraqi officials and a senior US official put the active number of fighters at 60-80,000, noting that, while many people have enrolled into the PMF to receive a payroll, a substantial number are not actively fighting.

[24] Interview with Hawza seminary clerics, Najaf, October 2016.

[25] See Ranj Alaaldin, “Legalising PMF in Iraq: why it’s not all bad news”, Al Jazeera, 1 December 2016, available at http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2016/11/legalising-pmf-iraq-bad-news-161129140729509.html.

[26] See Mamoon Alabbasi. “New Iraqi law legitimising militias sparks controversy”, The Arab Weekly, 4 December 2016, available at http://www.thearabweekly.com/Opinion/7214/New-Iraqi-law-legitimising-militias-sparks-controversy; and Michael Knights “The PMF in Iraq: Fight and then Demobilize”, Al Jazeera, 1 December 2016, available at http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2016/12/pmf-iraq-fight-demobilise-161201090942532.html.

[27] Interview with senior Iraqi politician, Baghdad, October 2016. This point was also highlighted by a number of European and UN senior officials during interviews in Baghdad, October 2016.

[28] Interview with senior security consultant familiar with the Mosul operations and Sunni parliamentarian, Baghdad, October 2016.

[29] See Mustafa Saadoun, “Iran, Turkey fight over Tal Afar”, 18 November 2016, Al Monitor, available at http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2016/11/tal-afar-iraq-turkman-turkey-pmu-syria.html. This position was reaffirmed by a senior Turkish official during comments made under the Chatham House Rule, December 2016.

[30] Interview with senior US and European officials, October 2016.

[31] Interview with former senior Shia Iraqi official, Baghdad, October 2016. This assessment was also provided by Kurdish and Western interlocutors interviewed for this paper.

[32] For more detail see Yaroslav Trofimov, “After Mosul, Iraq’s Kurds face internal crisis”, Wall Street Journal, 24 November 2016, available at http://www.wsj.com/articles/after-mosul-iraqs-kurds-face-internal-crisis-1479983400.

[33] Interview with senior PUK adviser and independent security analyst, October 2016.

[34] Interview with senior European official, Erbil, October 2016.

[35] Interview with senior Iraqi Sunni parliamentarian, Baghdad, October 2016.

[36] Interview with senior Iraqi Sunni tribal leader, Baghdad, October 2016.

[37] Interview with senior Iraqi official, Baghdad, October 2016.

[38] Interview with senior Western officials, Baghdad, October 2016.

[39] Interviews with Iraqi and Western officials engaged in decentralisation projects from 2005-2016.

[40] Interview with Iraqi Shia politician, Baghdad, October 2016.

[41] Interview with senior adviser to the PUK, October 2016.

[42] Interview with senior Western official extensively familiar with counter-ISIS operations, Baghdad, October 2016.

[43] This section, though reflecting entirely and solely the opinions of the author, is the result of the author’s confidential interviews and meetings with Libyan officials and experts and with Western and Middle Eastern diplomats in Tunis, Rome and Milan between 31 October and 24 November 2016.

[44] For more on this, see Mary Fitzgerald, “Finding their place – Libya’s Islamists during and after the 2011 uprising”, in Peter Cole and Brian McQuinn (eds), The Libyan Revolution and its Aftermath (Hurst Publishers, 2015).

[45] More on this point in Mattia Toaldo, “Is the sky falling on Libya?”, ECFR, 23 September 2016, available at https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_is_the_sky_falling_on_libya_7129.

[46] On the role of Salafists in Sirte, Tripoli and Benghazi, see Fred Wehrey, “Quiet no more”, 13 October 2016, Diwan, Carnegie Endowment, available at http://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/64846.

[47] On Russia’s increasing involvement in Libya, see Tarek Megerisi and Mattia Toaldo, “Russia in Libya: a driver for escalation?”, Sada Journal, 8 December 2016, available at http://carnegieendowment.org/sada/index.cfm?fa=66391.

[48] French special forces have been present in Benghazi since early 2016, fighting ISIS and other armed groups alongside Haftar. In July, the French government admitted three casualties in Benghazi among its forces. See Chris Stephen, “The French special forces soldiers die in Libya”, the Guardian, 20 July 2016, available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/20/three-french-special-forces-soldiers-die-in-libya-helicopter-crash.

[49] Mary Fitzgerald and Mattia Toaldo, A Quick Guide to Libya's Main Players, ECFR, December 2016, available at https://ecfr.eu/mena/mapping_libya_conflict.

[50] Author’s confidential interviews with Libyan experts and security officials, Tunis and London, October-November 2016.

[51] The United Nations Support Mission in Libya is currently tasked with implementation of the Libyan Political Agreement and with facilitating the Libyan Political Dialogue. UNSMIL also has the responsibility of coordinating humanitarian aid and promoting reconciliation.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.