A problem shared: Russia and the transformation of Europe’s eastern neighbourhood

Summary

- The EU’s Eastern Partnership policy is set to receive an update rather than an upgrade consummate with current geopolitical pressures.

- The Eastern Partnership’s central flaw is its design, which allows local political elites to build ‘facade democracy’.

- Core to democratic transformation are genuine rule of law reform and strong security against external threats.

- Adopting a new ‘shared sovereignty’ model would allow the EU into Eastern Partnership states to push through reform, guarantee the rule of law, and expose evasive local elites.

- Failure to strengthen Eastern Partnership states in this way could strengthen Russia and allow authoritarianism to diffuse westward into the EU.

- The EU should make shared sovereignty the basis for future Eastern Partnership relations, building on the momentum of the new accession process secured by France.

Introduction

Mixed feelings accompanied the tenth anniversary of the European Union’s Eastern Partnership in Brussels last year. It ought to have been the moment to celebrate the EU’s soft power in its neighbourhood – but many of the hopes held for the Eastern Partnership at its launch back in 2009 remain unfulfilled. On issues of the rule of law, corruption, and state capture by plutocratic and corrupt interest groups, standards continue to fall far short in Eastern Partnership partner countries. And, just as within the EU itself, there are signs of democratic regression in these countries.

The reasons for this abound. One is the passive inertia that long ago took hold in post-Soviet regimes, which often lack proper institutions and capacities to effectively administer public resources. Local political elites’ active resistance to change has often been strong, as their interests are directly affected by the course of desired reforms. The rise oligarchy across all Eastern Partnership countries has resulted in the emergence of facade democracy and – crucially – in the failure of the reform of the rule of law, without which foundation no other true reform can succeed. On top of this, local resistance is augmented by a strong authoritarian push from Russia, which provides financial and political backing to favoured elites. This situation has endured since at least the turn of the century, but became more urgent in the last decade.

When, in 2009, the EU approached Eastern Partnership countries with a sense that its demands and requests would be generally good for them – and were reflective of European values – the idea that their success would be also good for the EU itself was not a consideration. But, in the intervening period, the strengthening of authoritarian regimes on Europe’s doorstep has created an ‘alternative model’ to which some governments in EU member states actively aspire. However, the EU does not – yet – identify the absence of thoroughgoing democratic change as a security issue that could also further weaken it. In the future, therefore, a stronger security dimension will be a necessary component for a successfully renewed Eastern Partnership.

In establishing the original Eastern Partnership, the EU adopted a halfway house that sought to avoid directly challenging Russia and thus omitted any offer of EU membership. It, however, equally failed to offer something that jolted these countries into real reform. The Eastern Partnership lacked a strategic imperative powerful enough to make its individual components a reality. It is unlikely that today’s EU will fully compensate for this either, once it completes its upcoming review of the Eastern Partnership. But the EU should as a matter of priority re-examine its approach to the status of Eastern Partnership countries. Its next step should be to adopt a model of ‘shared sovereignty’ in the region – an enhanced form of engagement with a participating state that includes important elements of direct supervision of reform by the EU. Only this will help dismantle the Potemkin village nature of much ‘reform’ under the Eastern Partnership, and only this will help convince voters in the Eastern Partnership region of the value of EU efforts.

Eastern Partnership states that have declared an ambition to join the EU should make good on the logic of this declaration by agreeing to join in the shared sovereignty model. And this model already exists in embryo with certain other projects in the region: Moldova, Ukraine, and Georgia have already shared their sovereignty in some form by inviting EU missions into their territories. Furthermore, by applying the shared sovereignty approach, the EU would organically align its Eastern Partnership strategy with an accession process recently reworked at France’s request.

The EU states that it seeks to be a geopolitical actor. Given this, it is becoming unthinkable for it to claim to be a player that can exert its will in its own backyard if it is unable to point to examples of where it has brought about real change, or where it can make a good claim for future success. To strengthen its reputation and its capacity to act, the EU should adopt shared sovereignty as a central plank of its reformed policy on its eastern neighbourhood.

The Eastern Partnership: More labyrinth than tunnel

The Eastern Partnership began in 2009 as an initiative between the EU and six countries to its east – Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine. From the beginning, the partnership has had a somewhat amorphous status. Some EU sources refer to it as a forum for policy exchange and cooperation, while others view it as a specific dimension of the European Neighbourhood Policy. Crucially, rather than resembling a tunnel with a clear, if distant, end point, the road map the EU provides its eastern neighbourhood partners looks more like a labyrinth – once in, there are multiple routes one can take, the destination is vague, and there is little reason not to simply stop moving forward.

This complex maze of policy instruments and initiatives emerged as an attempt to address the problems prevalent in the six countries, whose post-1991 political systems were orientated more towards Russia than towards the West, and failed to establish effective control over ruling elites. These problems – and, consequently, the reforms recommended under the Eastern Partnership – are not unlike those that accession states work on by implementing the acquis communautaire. But the Eastern Partnership as originally designed was perhaps never really up to the challenge, and the various duplications and policy superficiality that characterise it after ten years are certainly not appropriate for the 2020s. This does not mean that the EU’s investment in the Eastern Partnership has been in vain: it is likely to have made a generally positive impact. However, it is also clear that the EU has to do, if not more, then better in its eastern neighbourhood in the coming years.

EU policymakers are aware of these challenges. In 2017 they sought to provide some focus to Eastern Partnership activity, holding a dedicated Eastern Partnership summit in Brussels that proposed “20 deliverables by 2020”. These updated goals reflected four key priority areas: stronger economy; stronger governance; stronger connectivity; and stronger society. But, despite overly triumphalist assessments of Eastern Partnership successes by EU officials (guided no doubt by diplomatic considerations), there has been either stagnation or regression on the 20 deliverables.

In 2019 the European Council instructed the new European Commission “to evaluate existing instruments and measures” with the aim of agreeing new long-term policy objectives. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen followed this up by requesting that the incoming neighbourhood and enlargement commissioner, Olivér Várhelyi, formulate the new objectives by the middle of this year. Von der Leyen indicated that the new policy should reflect both innovative and realistic frameworks of engagement. This does not sound an unreasonable balance to strike, but a subsequent Joint Communication on Eastern Partnership policy from the Commission and the high representative emphasised realism rather than innovation. The approach adopted in the structured consultation on the future of the Eastern Partnership working document contains further cause for disappointment, focusing as it does on activity similar to the 20 deliverables.

The signs are, therefore, that the much-anticipated rejuvenation of the Eastern Partnership after 2020 is likely to be an update rather than an upgrade. Unfortunately, this will send a strong signal that any refreshed Eastern Partnership policy will enter the same vicious circle as its predecessor. The bureaucratic process, the need for political consensus among EU member states, and the limited time made available will doubtless all go towards explaining the new policy’s suboptimal quality.

However, all this obscures the most important part of the story: the weakest element of the emerging Eastern Partnership policy framework is its design, which allows for, and even encourages, partners to make changes that at first glance may look like progress. In fact, these tend to be a collection of imitation reforms that, often purposely, fail to change the underlying corrupt culture and structures of powers present in all Eastern Partnership countries.

Not a total flop

It is worth reflecting on some of the successes of the Eastern Partnership. On the positive side of the ledger are the visa-free regimes established between the EU and Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova. These have boosted people-to-people contacts and business mobility and trade; made the countries more attractive to their own diasporas; and secured borders. The EU also has facilitation and readmission agreements in place with Armenia and Belarus, which opens up the prospect of visa-free regimes for these countries. And more than 80,000 young nationals are to benefit from the EU’s academic exchange programmes by the end of 2020, including Erasmus+.

On trade, the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTAs) the EU signed with some Eastern Partnership countries appear to have led to a rise in the bloc’s share of some of these countries’ exports: to 43 percent for Ukraine and to 63 percent for Moldova by 2018. Georgia’s share is stagnating but, even so, the EU remains the country’s main trade partner. The case of Moldova, in particular, shows that easing trade with the EU can mitigate Russian embargoes and reduce their effectiveness as mechanisms to pressure former Soviet states.

On democracy more broadly, there has been some progress. And, given the challenging regional context, some of the achievements are considerable. Ukraine succeeded in remaining democratic after its bloody revolution in 2014 and, most recently, freely elected another president – all while there was a war on its soil. Armenia, despite having no Association Agreement in place, made a strong stand for democracy and transformation in 2018 with its peaceful overthrow of the incumbent administration. Georgia, too, conducted a peaceful political transition in 2018, despite strong domestic political polarisation. Its opposition and civil society are still powerful, managing to somewhat contain recent attacks on the freedom of the press and resist government pressure on judicial independence. Finally, elections still matter in Moldova: despite oligarchic state capture, in 2019 the opposition took power, even if it then failed to protect these gains from a different plutocratic group.

Belarus remains a centralised and authoritarian state. It has shown openness to dialogue with the EU, but its president, Alyaksandr Lukashenka, is a master of drift: the fact that Belarus is exhibiting such openness is likely due to the difficulties of his relationship with Russia. Similarly, triggered by its search for foreign policy diversification and its own complex relations with Russia, Azerbaijan has also been looking to upgrade its relations with the EU. In July 2018, Azerbaijan and the EU agreed on new partnership priorities, which include areas such as strengthening institutions and good governance – similar to countries that have made more progress within the Eastern Partnership. The EU has never had grand ambitions for these two countries but, adjusted for authoritarian conditions, Eastern Partnership policies have at least helped prevent a deterioration in their publics’ and elites’ attitudes towards the bloc.

Overall, the Eastern Partnership has helped maintain the presence of the EU in these countries, both as a role model and as a strategic destination. The Eastern Partnership produced an impetus for policy progress in some areas and may have averted greater backsliding.

The construction of facade democracy

To understand where and how the EU has fallen short with its eastern neighbours, it is important to first examine the essential components of a healthy and functioning democratic state. Are regular elections an effective indicator or determinant of genuine democratic transformation? Not necessarily. Regular elections in Eastern Partnership states’ plutocratic and corrupt political systems play the role of agreed and informally regulated duels between competing oligarchic groups. Parties frequently play the role of political avatars for these groups, legitimising their takeover of political power. There is little true party competition. Populations tend not to identify ideologically with any party, with the exception of nationalist groups, and people vote for individuals they believe will benefit them financially, or whose rent-seeking networks they are connected to.[1] All Eastern Partnership countries exhibit diminishing returns-shaped dynamics in the areas of the rule of law, corruption perceptions, political rights, and civil liberties. Some even display slight negative returns.

Fundamentally, true democratic transformation is revealed by the presence of genuine rule of law in a country – and it is to this that EU policymakers should pay the closest attention as they revise the Eastern Partnership policy. In a properly democratic state, fair and equitable justice is a public good – everyone has access to it, and it cannot be depleted. But this is absent in all Eastern Partnership countries: justice has acquired the traits of a private good, where the ruling elites control who receives it and even the type of justice that is available. The value of controlling the judicial system is enormous – it exponentially increases the rents that corrupt elites can remunerate their supporters with, increasing their chances of staying in power.[2] Even the legal systems in Moldova and Ukraine – to name two of the three traditional Eastern Partnership ‘frontrunners’ – are prone to selective justice, corruption, and political control. Georgia is a surprising exception, as it fares much better on the rule of law than the other two. But it, too, is struggling.

Why and how did this happen in Eastern Partnership countries, which were supposed to make progress within the framework of the Eastern Partnership? After all, the EU offered them an attractive framework for cooperation, including visa-free travel, free trade agreements, and reform assistance programmes. Paradoxically – but crucially – even genuinely positive reforms such as these can be exploited by political elites if they strengthen the grip of ruling groups. Any increase in financial flows coming from the EU, either through assistance or trade preferences, can help elites buy support and obscure the gravity and magnitude of ruling elites’ predatory activities. Eastern Partnership measures can, then, ultimately reduce social pressure on plutocratic rulers as the most entrepreneurial and politically active citizens take advantage of visa-free regimes to avoid interaction with corrupt elites rather than engage with them through political opposition.

Over many years, incumbent governments have grown skilled at devising a tale of progress, directing funding to superficial objectives with the end result of building ‘facade democracy’. For example, in response to EU requests, governments may introduce laws and regulations, or create anti-corruption and integrity bodies. But the proverbial empty vessels make the loudest sound. For instance, under Petro Poroshenko, Ukraine created a Public Integrity Council (PIC), a judicial watchdog that included civil society representatives and whose job it was to help the High Qualification Commission of Judges (HQCJ) assess judges. However, the HQCJ ignored the recommendations of the PIC, leaving in position some 80 percent of judges. It is thus possible to deaden the intended impact of reforms by not implementing inconvenient laws and regulations, implementing them selectively, or only pretending to implement them. Or, when reform does happen, incumbents set up informal mechanisms instead: even where, for example, judges are appointed independently, the wider weakness of the rule of law means that ruling elites are able to put pressure on judges through law enforcement agencies and other methods.

To justify this stagnation to development partners, elites invoke lack of resources, expert capabilities, or play the geopolitical card. Governments make use of Western lobbying groups (particularly those based in the United States) and deploy patriotic and national security narratives to compensate for shortcomings in anti-corruption and legal reform policies. For instance, Moldova’s government under Pavel Filip, in office during 2016-2019, used the genuine threat from Russia to seek American support, despite a sharp deterioration in the quality of the country’s democratic reforms. After a couple of years, the US finally withdrew its support for the Filip government – which, although it lamented the Russian threat, continued to do business with Russia, making security and political concessions on the Transnistria conflict and the Russian military presence in Moldova, and allowing Russian propaganda in local media outlets. Similarly, the Poroshenko government sometimes exploited the war in Donbas to excuse a lack of progress on anti-corruption reforms.

Part of the reason Eastern Partnership governments have managed to avoid enacting true reform is the design of the Eastern Partnership itself. For example, one key practice for judging a country’s progress is to count the number of laws it has passed. But this amounts to little more than a box-ticking exercise. However, if the box-ticking approach suits incumbents, it falls short of public expectations in Eastern Partnership countries. Voters want reforms, and their leaders know this – otherwise, they would not include ‘moving closer to Europe’ statement in their political rhetoric, as they so regularly do. It is the frustration of voters with the pace of reform that allowed in outsiders such as Volodymyr Zelensky in Ukraine and Maia Sandu – who had few resources with which to match the incumbent president, Igor Dodon – to take power in Ukraine and Moldova respectively. Over the last five years, an average of more than 70 percent of citizens in Moldova revealed their dissatisfaction with existing policies. Ukraine displayed the same trend.

Moldovans and Ukrainians are particularly frustrated with corruption levels – from petty corruption to that involving oligarchic control, bank fraud, and the misappropriation of public funds. If it can find a way to truly implement mechanisms that expose and discourage such reform-imitation, the EU will likely find favour among the population at large in Eastern Partnership countries – although, in the short and medium term, there is relatively little possibility of this in Belarus and Azerbaijan. In fact, by failing to expose reform-imitation, the EU risks appearing to aid the consolidation of plutocratic rule. For instance, when civil society organisations criticised judicial reform in Moldova, the authorities retorted that the changes were conducted on the basis of the EU’s technical advice. In Ukraine, despite extensive financial and expert assistance for judicial and anti-corruption reforms, the population does not yet seem satisfied with progress, and justifiably so. A 2016 European Court of Auditors assessment found the EU’s assistance to Ukraine, including in the area of anti-corruption, to be only “partially effective”.

The rule of law – and security

The current state of affairs is even more dismaying for reform-minded citizens because the Eastern Partnership does not adequately take into account the ‘double resistance’ present in many partnership countries. This comprises resistance by local political elites that is, in turn, buttressed by resistance from Russia, whereby the Kremlin targets Eastern Partnership countries with indirect aggression technologies to weaken their social fabric, create conflicts on their territory, and discredit reformist politicians.[3] For example, the frozen conflicts that Russia incited and sustains through financial and political means present a convenient way for the country to fuel inter-ethnic insecurities and anti-Western sentiment. Kremlin-run websites promote disinformation campaigns, pushing out false information such as claims that 80-90 percent of Moldova’s exports go to Russia, that US ambassador to Moldova demanded a “Russian anti-propaganda law”, or that the European Commission seeks the disintegration of Ukraine. Russian activity cultivates fear and insecurity among segments of the population, with the aim of elevating its local proxies to positions of power.

Importantly, Eastern Partnership schemes currently invest too little in security-related assistance to concretely help countries address such non-conventional security threats. The bulk of EU security assistance goes towards public security, such as national police forces, with only modest contributions to cyber security and NGO-led anti-propaganda work. This means that Eastern Partnership states are not as well protected as they should be against Russian influence operations and other security threats. Moldova, Georgia, and Ukraine are in particularly great need of strengthened military capabilities and resilience against hybrid threats.

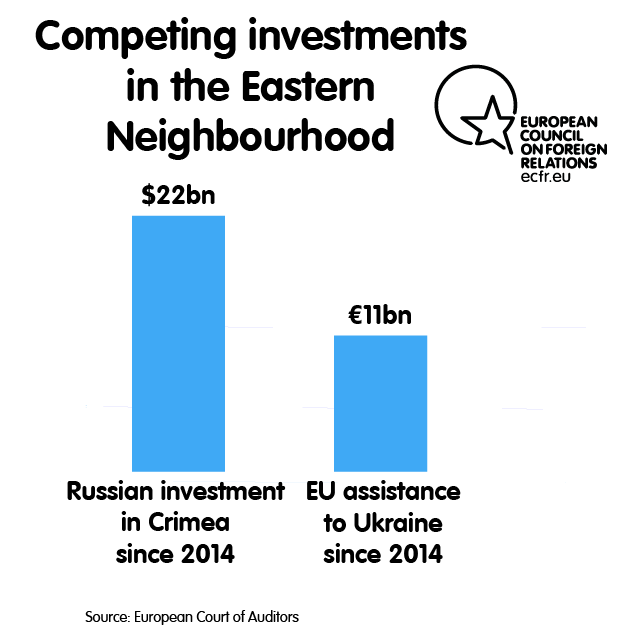

In contrast, Russia has poured more than $22 billion into Crimea alone since its annexation: this dwarfs the assistance that the EU has offered to Ukraine since 2014 (more than €11 billion). Georgia and Ukraine receive some military assistance from the US, but both countries still need comprehensive support to strengthen their deterrence capabilities and build up their resilience against hybrid threats. US security support for Moldova is limited; the country needs serious knowledge transfers and institutional transformation to build up even a minimal resistance to hybrid security threats. The development of these military and hybrid resilience capabilities in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine is critically important because it raises the political and reputational cost of aggression for Russia, partly by increasing the chances that such activity will become public knowledge.

Finally, the presence of democratically underdeveloped states situated around the EU has implications for the security of Europe’s own democratic ideals and practices too. Modern, non-kinetic security challenges cross borders when left to gestate in a conducive environment. And all Eastern Partnership countries currently find themselves in this turbulent context. Regardless of how it may frame it, the EU should develop a bold security element in its Eastern Partnership policies – at least for the sake of its own security and the protection of its Eastern Partnership-related investments. Otherwise, there is a risk that the maturing political technologies of popular manipulation and control could diffuse into the EU. They represent tempting alternative forms of political engagement for populist politicians, who can easily exploit them to exploit tension between EU member states and Brussels. Supporting Eastern Partnership countries’ security would, therefore, also allow the EU to closely study the hybrid conflict technologies employed by Russia beyond its borders.

The EU has revised its approach to the eastern neighbourhood in recent years, as shown by its latest effort in formulating 20 goals for 2020. However, its current direction of travel is to merely update the Eastern Partnership. This will likely fail to take account of the weaknesses of the policy’s current design, and of the changed geopolitical context in the neighbourhood. Fundamentally, if there was genuine political will to conduct effective reforms in Eastern Partnership states, they would have already implemented these reforms. Clientelist governments lack incentives to conduct real reforms, and are subject to increased, if indirect, political pressure and influence from Russia that further obstructs such progress. The EU must, therefore, revisit its underlying strategy on Eastern Partnership countries, and fashion a new policy accordingly. The first and the most critical candidate for such a strategy is ensuring genuine rule of law reform and shoring up Eastern Partnership countries’ security for the 2020s.

Refining the democratic transformation mechanism

In seeking to improve the Eastern Partnership, the EU needs first and foremost to refine its understanding of the democratic transformation mechanism. One illustrative pattern emerges: such progress as there has been takes place mostly on the ‘periphery’ of democratic development – reflected in facade reforms that only imitate the process. This leaves the substance of the political system unchanged without affecting the elements necessary to bring about a true democratic transformation. The most significant element of this is genuine rule of law reform. The rule of law consists of ‘rule bound to legal norms’ – a definition that is unrelated to human rights or democracy, which, as noted, can appear to be fulfilled without establishing true democracy.[4]

True rule of law reform curbs selective justice, creates political and economic stability, and, most importantly, has the potential to constrain political elites and minimise corruption. In transitional political systems such as those of Armenia, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, this would lend citizens more effective control over ruling elites, increasing these elites’ accountability. It would also reduce predation – decreasing losses of public money through misappropriation and corruption – and would encourage entrepreneurs to leave the grey economy, thereby increasing the tax base. These advances would allow for an increase in public sector salaries and otherwise improve the distribution of state resources and decrease clientelism.

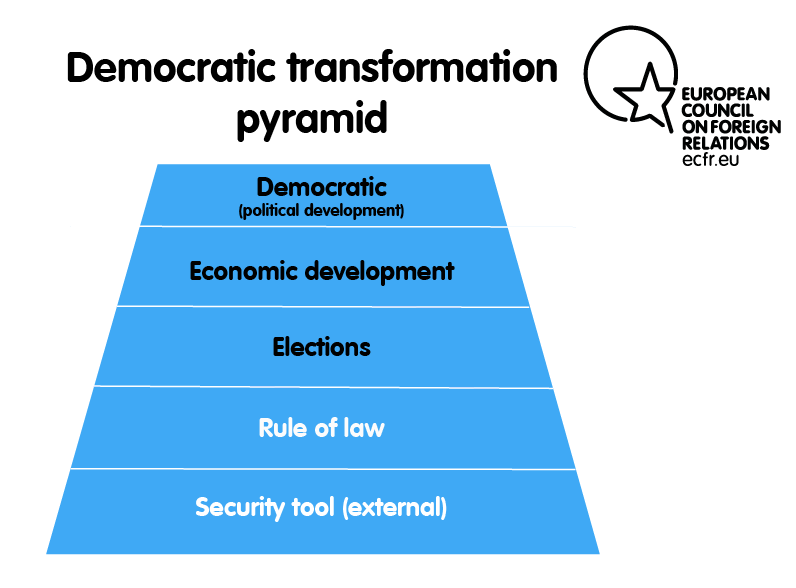

The following ‘democratisation pyramid’ illustrates the stages of true democratic transformation.

As the graphic above shows, it is only possible to make true progress at each stage if one has completed the stage below, by crossing a minimum effective threshold. These stages relate directly to the context of Eastern Partnership countries in the following ways.

Firstly, it is difficult to meet the conditions of the upper four domains if one has not provided security against external threats. This is a historical trend most obvious in states affected by armed conflict. It is less obvious when the security deficit is due to indirect aggression, such as proxy wars or the use of hybrid technologies in inter-state conflict, which are a notable feature of the post-Soviet region. Secondly, the rule of law is a prerequisite for the proper functioning of elections, democratic reform, and economic development. Without this, elites will fail to enforce property rights except to their own benefit, will rig elections, and will retain control of the political process.

The EU should upgrade the Eastern Partnership in line with this approach. But, to do so, the EU will have to make changes to its conditionality instruments and how it applies them. In its current form, conditionality allows little scope for distinguishing genuine transformations from imitation reform. The EU should build dedicated evaluation capabilities, integrating them into its official structures as part of a unit that specifically addresses Eastern Partnership development. Such evaluation will require a good understanding of Eastern Partnership countries’ domestic processes, actors, and dynamics, in addition to technical evaluation skills across the areas of democratisation suggested above. Currently, EU practice is to task Eastern Partnership states with implementing a version of the acquis communautaire. But this is suboptimal: it tries to build a house on an uneven surface. As discussed, most Eastern Partnership countries lack the institutional foundations that would allow them to implement elements of the acquis. The EU effectively skips over the basic building blocks of security and the rule of law, addressing their form rather than their substance, and focusing on elections, democratic reform, and economic development – none of which can really operate fairly without security guarantees and the rule of law.

On the basis of this insight, the EU can adopt a policy approach that: is both realistic and ambitious, as per the recent request of the president of the European Commission; draws and expands on current EU advice and technical missions; will increase the chances of true reform, addressing the concerns of citizens of Eastern Partnership countries about the seriousness of EU efforts to help them; and insulates partner countries from external influence.

The shared sovereignty strategy

The solution lies in the EU and Eastern Partnership countries jointly adopting a shared sovereignty model. This model will give the EU a stronger chance of success in embedding change in its neighbourhood, enabling it to directly test the sincerity of local elites’ desire to conduct reforms. It creates an opportunity to expose them to domestic political pressure if it becomes clear that they prefer to imitate change rather than truly enact it.

Shared sovereignty takes the form of supervised engagement, by the EU, with the participating Eastern Partnership country. It is an on-the-ground and nearly real-time audit of reforms by the EU experts. Currently, the EU funds democratic reform projects and provides individual Eastern Partnership countries with non-mandatory advice. The shared sovereignty model of EU-Eastern Partnership interaction would also involve – for the more ambitious and advanced Eastern Partnership states, at least – a hands-on EU monitoring role in the technical phase of implementation.

A vital part of such a strengthened partnership would be a stronger and more effective conditionality tool. The EU’s funding for Eastern Partnership governments would be conditioned on positive reports from its reform monitors. Monitors’ stronger presence and greater room for manoeuvre would enable them to immediately detect if a reform element was failing, identify the obstacles it faced, and engage with the host government in a prompt manner to fix the issues. This constitutes direct technical supervision of the quality of the reform framework. Instead of funding technical resources, the EU could, in many cases, delegate its own experts to ensure that its money was being spent as intended. Because normal democratic supervisory mechanisms in Eastern Partnership states have been eroded, undermined, or removed, this is the only way to ensure the effective use of EU funding.

Besides more powerful monitoring and problem-identification mechanisms, the enlargement of the sanctions toolbox would also be key. The EU could target a country that is failing to advance along the path of reform it has signed up to with sanctions on individuals, proxies, and oligarchic businesses, and freezes of illegally acquired assets. Targeted sanctions against plutocrats who undermine Eastern Partnership projects would become a necessary measure that would increase the effectiveness of this new, stronger EU role.

There is a further benefit to greater direct engagement with Eastern Partnership states that have Association Agreements with the EU and are thus further down the path of cooperation: regulation of the speed of reforms, which is a critical condition for success. Comparative research indicates that rapid changes are much more likely to produce positive results than gradual adjustments. Moldova’s Western partners had made clear that they preferred the gradual introduction of reforms as pursued by the Sandu government – but this gave corrupt and anti-democratic interests groups time to mobilise and, eventually, topple the government.

Perhaps most crucially of all, if an Eastern Partnership country refuses to accept this enhanced framework, this would be a clear signal that the ruling elites felt endangered by the reforms and did not intend to carry them out. The EU would then have given itself the powerful option of disengaging from these countries and downgrading them into the Belarus-Azerbaijan category of “unambitious Eastern Partnership members”. This would allow the EU to save valuable resources. More importantly, funding Potemkin villages rather than real structural change is detrimental to the democratic development of Eastern Partnership countries. The option of downgrading countries that refuse to engage in true reform would also allow the EU to signal to Eastern Partnership countries’ leaderships and citizens that it was no longer turning a blind eye to the obstruction of reform. This will particularly strengthen its reputation in the eyes of a public tired of facade democracy and political actors genuinely committed to reform. Governments in Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia have previously asked for EU accession. And joining the EU would require them to share sovereignty. So, what better way for Eastern Partnership states to signal that they really want EU integration than to begin to share sovereignty in this way?

Shared sovereignty is, in fact, not an entirely new phenomenon in the region. For instance, Albania – a candidate for EU accession – also faced severe challenges in maintaining the rule of law, due to a lack of an independent judiciary, the population’s distrust in the justice system, and corruption. In 2002 it agreed with the EU to initiate a technical assistance project that addressed these issues, which gradually evolved into the “Consolidation of the Justice System in Albania” project. The EU is currently helping Albania improve related capacities, since it has already built the foundation for the effective implementation of this type of assistance. The Eastern Partnership states are yet to achieve this type of progress.

The EU has had a monitoring mission in place in Georgia since 2008, when the Georgian government asked for assistance. This is a classic example of shared sovereignty, in which a country invites the EU to monitor its territory – in this case, the areas along the demarcation lines with its two breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Other examples of this type of shared sovereignty include the EU Border Assistance Mission to Moldova, monitoring the flow of goods and people on the Transnistrian segment of the Moldova-Ukraine border, and helping both Moldova and Ukraine harmonise border control, customs, and trade standards with those of EU member states.

Not all Eastern Partnership countries are currently at the same stage of development, to say the least. The EU should take account of this by tailoring its approach to the shared sovereignty model. To this end, the EU could divide a ‘next generation’ Eastern Partnership programme into three packages: the more ambitious ‘AA club package’ would encompass strategically targeted assistance for the implementation of Association Agreements and DCFTAs, under rigid and specific conditionalities for each country and with fixed targets; an intermediate version – perhaps most suited to Armenia (the new hope of the Eastern Partnership) – that would provide baseline assistance in the rule of law, institutional reform, and economic modernisation to keep up the momentum gained by the current government; and a minimal engagement package, suitable for Azerbaijan and Belarus, that helps these countries expand their economic cooperation with the EU, which could then push for more concessions on human rights and the rule of law. The economic approach would pose less of a threat to these regimes than demands around the rule of law and elections. This would, therefore, be relatively likely to succeed, and would greatly improve the living conditions of the population.

Besides the detail and structure of the policy itself, the EU should consider where the shared sovereignty strategy should sit within its own institutional setup. One promising option would be to make the Eastern Partnership the responsibility of the high representative for foreign and security policy. Such a move would be firmly based in the insight provided by the democratic transformation mechanism, which is that failings on external security preclude the genuine development of the rule of law. And foreign interference exploits weaknesses in the rule of law to acquire control over Eastern Partnership countries’ economic and democratic institutions. If an Eastern Partnership country is unable to truly preserve its sovereignty, it will be unable to cooperate with the EU via shared sovereignty. Any EU democratic development package for Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova must, therefore, contain a strong security assistance element.

With the shared sovereignty model in place, the EU will be in a good position to ramp up its strategic communications with an eye on geopolitics, and to provide more funding than Russia does. Such an approach would strengthen domestic actors who are attempting to implement more prodigious reform programmes, and would likely increase popular pressure on elites to be selective in accepting Russian funding. Importantly, among voters, moving closer to Europe remains popular in a way that moving closer to Russia does not. But current policy and structures do not allow the EU to capitalise on this advantage in a direct way.

There is another key element of the shared sovereignty model. A membership perspective would provide a new and compelling incentive to carry out political and economic reform. This may sound unattractive to some EU leaders and voters. But, given the tremendous challenge posed by genuine rule of law reform, the long time such reform would take, and the extensive political transformation it would bring about in Eastern Partnership states, there is little risk in merely raising the possibility of future membership. This membership perspective could take many forms. For instance, true rule of law reform should be the threshold at which the EU invites an Eastern Partnership state into formal accession talks. Such an invitation would encourage reformers at home and provide them with political capital. At the same time, the EU could control the duration of the accession process. The bloc would condition this on the achievement of genuine reforms, which it will objectively assess through the new shared sovereignty framework. Such a strategy would allow the EU to play an elevated and increasingly influential role in Eastern Partnership states’ development and modernisation – one that could transform the prospects for reform in these countries. Importantly, the strategy would finally turn the Eastern Partnership labyrinth into a tunnel whose endpoint is distant but identifiable.

Conclusion

The six countries of the Eastern Partnership are some of the EU’s closest neighbours and, as such, pose a challenge to an organisation that has stated its ambition to act geopolitically and display its sovereignty on the world stage. This ambition demands that the EU demonstrate its influence and capacity to act in its immediate neighbourhood. Moreover, unlike in 2009, the question of whether to create a more powerful Eastern Partnership is no longer a regionally containable matter, as shown by the emergence of the risk of democratic backsliding diffusing westward. This is due to Russia’s increased activism in Eastern Partnership countries, as well as challenges to the democratic model and even to the sanctity of borders in Europe.

The EU leadership’s current approach to the Eastern Partnership problem is not encouraging, with it appearing to settle for ‘realistic’ goals rather than ones that are ambitious and transformational. It would be a mistake to drift down this path. Aside from the EU’s geopolitical proclamations, ordinary citizens in the Eastern Partnership region rely on the bloc to take a giant leap towards them and their ambitions. They have spent many years observing a regular drip of EU funding and the occasional dollop of political attention, but with little result other than facade democracy. So far, the EU’s efforts have failed to lay down the fundamental planks of reform, which are the rule of law and genuine external security in Eastern Partnership countries. Together, these planks would enable the states to make choices about sovereignty in a fair, transparent, and democratic way. Without advancing successfully through these stages of reform, it is impossible for them to achieve true democratic practice and associated freedoms. At best, the Eastern Partnership may have slowed a further deterioration in the region since 2009. But it has failed to recognise that local elites plead poverty of resources when, in fact, the problem is their poverty of ambition.

This is an opportune moment to fundamentally redesign the Eastern Partnership. The shared sovereignty model fits organically with the new accession methodology that France recently initiated, and that the European Commission has adopted. This creates a natural impetus for the Commission to adjust its Eastern Partnership approach accordingly.

The EU has a powerful policy instrument available to seize if it wishes. The bloc has experience of sharing sovereignty with neighbouring countries, and can build on this to wrap its geopolitical demands into an implicit challenge to Eastern Partnership governments. In doing so, the EU would be engaging in a showdown both with itself – as member states test the level of their ambition for their neighbours – and with Eastern Partnership governments. Carrying on with reform for the eastern neighbourhood that is tepid, specious, or both, should not be an option that EU leaders countenance any longer.

About the authors

Dumitru Minzarari is an independent policy researcher and a non-resident associate expert with the Chisinau-based Institute for European Policy and Reforms. He received his PhD in political science from the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, and his MA in International Affairs from Columbia University in New York. Minzarari’s research interests focus on international and national security, military strategy, modern warfare and conflict technologies, the diffusion of authoritarianism, and Russia’s foreign and security policies. Previously, he worked as the secretary of state (for defence policy and international cooperation) at the Moldovan Ministry of Defence; held expert positions in Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s field missions in Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan; and worked with a number of think-tanks in eastern Europe.

Vadim Pistrinciuc is a former Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung visiting fellow based in ECFR’s Berlin office. He was a member of parliament in Moldova from 2014 to 2019. He served as deputy minister of labour and social protection between 2009 and 2011, and was a senior political adviser to the prime minister between 2011 and 2013. He advised the prime minister on public administration reforms, political programmes, and political strategies. Prior to that, Pistrinciuc served an expert, project manager, and consultant to projects within international organisations (United Nations Development Programme, UNICEF, and the International Organisation for Migration) in the areas of human rights, public administration reforms, anti-corruption, and social development. He holds a PhD in sociology from Moldova State University.

[1] Dumitru Minzarari, “East or West –Moldova Weavers Between the EU and Russia,” Jane’s Intelligence Review, October 2014.

[2] Dumitru Minzarari, “Disarming Public Protests in Russia: Transforming Public Goods into Private Goods,” in Bálint Magyar (ed.), Stubborn Structures: Reconceptualizing Post-Communist Regimes (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2019).

[3] Yevhen Mahda, The Hybrid Aggression of Russia: Lessons for Europe, 2017, Kyiv: Kalamar Publishing House.

[4] Amy C Alexander and Christian Welzel. 2011. “Measuring Effective Democracy: A Human Empowerment Approach.” Comparative Politics 43 (3), p.274

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.