The lonely leader: The origins of France’s strategy for EU foreign policy

Many EU member states argue that President Emmanuel Macron does not consistently follow his own advice on the need for European defence cooperation. France should respond by taking the lead while involving its close partners

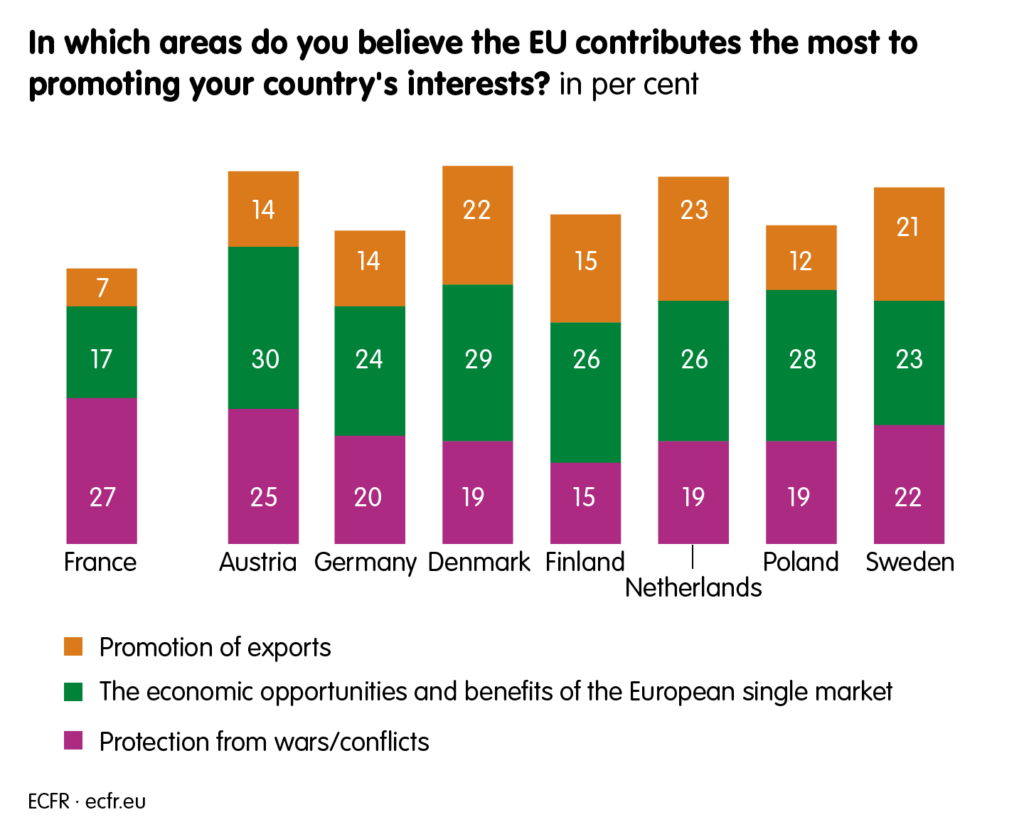

2020 was hard on European unity. The pandemic has forced EU member states to engage in an even more intense dialogue on the direction they want the bloc to take. From the Franco-German proposal for a recovery fund in May to the subsequent opposition to aspects of the EU budget from the so-called ‘frugal four’ (Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden), member states have debated the European Union’s raison d’être at length. And, as recent polling by the European Council on Foreign Relations shows, France perceives the EU’s greatest benefits differently from other member states.

Indeed, 27 per cent of French respondents to ECFR’s survey view protection from war and conflict as the area in which the EU provides the greatest benefits – a larger share than in any other national grouping. And just 17 per cent of them view the economic advantages of EU membership, including access to the single market, in this way – a smaller share than in any other surveyed country. This is consistent with earlier research by ECFR that identified France as the member state most appreciative of the geopolitical role of the EU. These differences seem to signal a gap between France and its European partners in their vision of the EU’s role and purpose.

The EU – and the structures that preceded it after the second world war – has been built on the idea of preserving peace through economic interdependence. Countries such as France and Germany tend to emphasise the first part of this; those such as Poland and Denmark tend to emphasis the second. The resulting disparity explains much about the current disagreements between member states, as shown by their tough recent negotiations on the EU’s Multiannual Financial Framework, disputes over strategic autonomy, and debates over what should be the next focal point of European political integration.

French people are proud to be among the founders of the organisations that preceded the EU, as well as of having opposed some of the bloc’s integration efforts.

Therefore, France’s insistence on the importance of preserving peace, as well as its initiatives that other member states sometimes perceive as unilateral, seem to reflect its aim to be a leader in shaping European foreign policy. And this could also explain its isolation in efforts to exercise the EU’s power on the global stage. Strategic autonomy, which is mentioned in the 2016 EU Global Strategy, is a policy area in which France and Germany are converging. But some member states still need to be convinced of the need for such autonomy, displaying a reluctance that French decision-makers sometimes have a hard time understanding.

Historically, French people are proud to be among the founders of the organisations that preceded the EU, as well as of having opposed some of the bloc’s integration efforts – notably, by voting ‘no’ in the 2005 referendum on a European constitution. Given that France has a significant influence on its partners in the union, the country can set the course of a European project that has a huge impact on its citizens’ lives.

The French state and French citizens are sincere in their call for the EU to become a sovereign actor. Accordingly, they have created initiatives and put forward proposals for a more integrated European foreign, defence, and security policy. But, at the same time, they are attached to the independence of the French military. Indeed, Defence Minister Florence Parly recently announced an increase of nearly €2 billion for the defence budget in 2021. They are also committed to the country’s status as a nuclear power – France plans to begin building a new nuclear-powered aircraft carrier soon.

The contrast between France’s focus on national sovereignty in defence and the European defence initiatives it proposes often puzzles its European partners. To understand this, EU member states need to look at the narrative built around the European project in France. French schools teach pupils that the EU has always been a project of reconciliation between France and Germany – one that ensured that there would be peace between the two countries in the second half of the twentieth century and beyond. French schoolbooks often refer to the EU using images of handshakes between French presidents and German chancellors; couple franco-allemand (the Franco-German engine) is a phrase that French students hear throughout their time at school. In France, European political integration was always meant to stem from economic integration – all French pupils have learnt about the successive plans put forward by French officials in this area, as well as their failures – and the EU is widely regarded as a vehicle to promote values (such as democracy, the rule of law, human rights, and equality) and a vision on the global stage.

President Emmanuel Macron frequently refers to the importance of building a Europe de la défense (a Europe that would protect). He has insisted on the creation of the European Intervention Initiative and mentioned European strategic autonomy every time he has had a chance to do so. But, according to many member states, Macron does not consistently follow his own advice on the need for European defence cooperation – a discrepancy that French decision-makers should be aware of and seek to offset, by conferring with their European partners before acting. When France launched a renewed dialogue with Russia in 2019, other member states recognised that this could only succeed if other EU member states sat at the table. However, Paris did not initially provide them with the opportunity to do so. By publicly referring to NATO’s “brain death” the same year, Macron called for the reinforcement of the European pillar in the alliance – but he did so by acting on his own. Rather than taking what is perceived as unilateral action by its allies, France should work on coalition building even more than it already does, taking the lead while involving its close partners.

In the context of the opening of the Conference on the Future of Europe and the prospect of the French presidency of the European Council in 2022, France could use this approach to work towards a redefinition of common values that would help the EU and its member states integrate their foreign policies and project power on the global stage. France should acknowledge that its geopolitical vision of the EU is not the only valid one and reach out to its partners to build coalitions, thereby leading the EU to rethink its international role in an increasingly multipolar world. France truly believes that the EU is a peace project. Such a project might have only been achievable through economic interdependence in the 1950s, but France can remind other member states that, in 2021, peace is at the intersection of several policy areas in which European cooperation is vital. The EU’s changing relationships with countries in its neighbourhood, Russia, China, and the United States all make the bloc’s role as a peace project more important than ever.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.