Sweden’s climate carol: From Ebenezer Scrooge to Greta Thunberg

The Swedish government has more room than it thinks to champion the EU recovery fund – and thereby nurture pro-Europeanism, rather than Euroscepticism, among Swedish voters

Decades of high taxation were what Sweden’s finance minister, Magdalena Andersson, pointed to when pressed earlier this year about her country’s “frugal” stance on funding the European Union’s post-pandemic recovery. She referred to decades of high taxation to pay off public debt as an explanation as to why Swedish taxpayers would be less than understanding if they were asked used to bail out countries that had not saved for a rainy day. However, the European Council on Foreign Relations has carried out polling to find out what Europeans’ attitudes really are about spending and the recovery; and it reveals that Swedish citizens, like their counterparts in other “frugal” countries, are not actually that parsimonious when it comes to what Europe should do to get out of the slump. When asked about the recovery fund the EU agreed earlier this year, only one in five Swedes said they thought the fund meant the EU was spending too much money.

Swedish voters appear to be more worried about being sidelined within the EU – 43 per cent believe their country has lost influence, compared to one-quarter who say it has increased. This could be partly due to the loss of a major ally through Brexit, but the recovery deal’s impact on public perception cannot be ruled out either. International media often referred to the deal as “historic”, but the national audience likely saw Swedish leaders fiercely opposing it but backing down in the end.

As Susi Dennison and Pawel Zerka recently argued, member state governments that focus on narrowly defined economic interests run the risk of leading voters in “frugal” states to think their countries are no longer influential and that EU membership may no longer be worth the price. To head this off, these states should reposition themselves and focus on how the recovery funds are spent, thereby contributing to shaping an EU that voters want to see.

The time is ripe for Sweden to come forth as a leader on climate within the EU

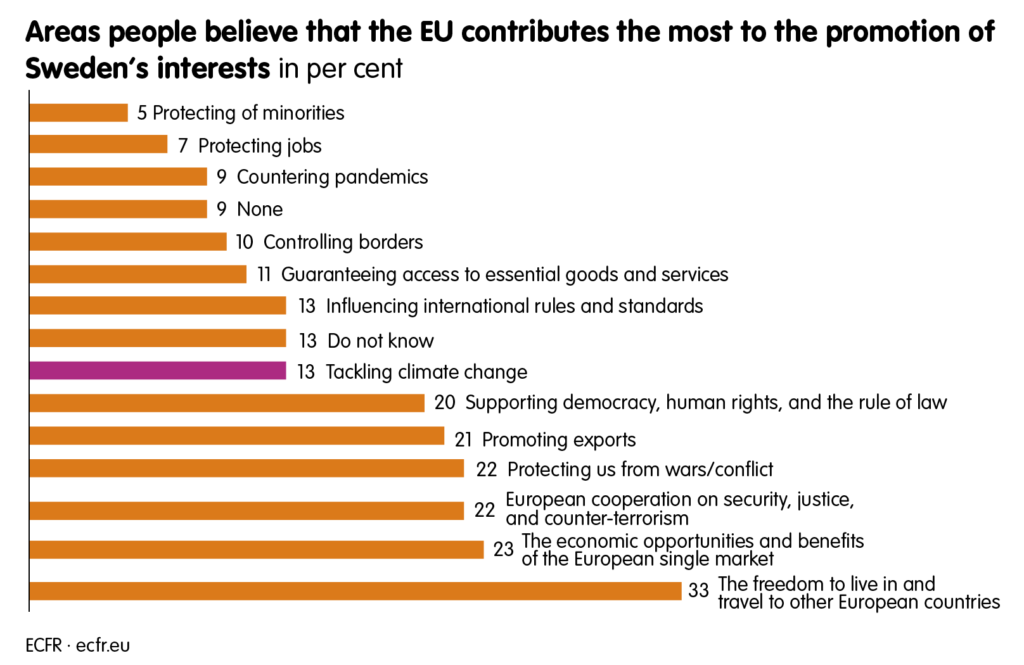

Instead of putting the emphasis on keeping the EU budget as small as possible, Sweden should find a positive agenda to push in the EU context – not only to sustain support for the EU domestically, but also to rebuild political capital and reclaim its position as a dynamic and progressive power that contributes to the union. With this in mind, there is potential for Sweden to lead on tackling climate change. Barely one in ten Swedes identify this area as one where the EU is currently contributing to furthering Swedish interests. In contrast, 51 per cent of Swedes think that the EU should do more to reduce carbon emissions and become climate neutral by 2050, according to the latest Eurobarometer. This is higher than in other “frugal” and “climate friendly” states – in Finland only 39 per cent want the EU to act on this and in the Netherlands it is only 37 per cent. A Eurobarometer special on attitudes towards the environment in March 2020 showed that Swedes view climate change as a bigger problem in the EU (83 per cent) than in their own country (72 per cent). And nearly three-quarters believe that decisions on protecting the environment should be taken jointly by the EU.

The EU is arguably better placed to tackle climate challenges than Sweden is on its own, and the country obviously has a stronger voice if channelling its environment ambitions through the EU – including in multilateral negotiations. For Sweden, with its high profile on climate issues and good standing internationally on green transformation, it would make sense to draw the public’s attention to the European Green Deal and the Next Generation EU recovery fund and to associate the EU with these key initiatives.

The European Commission is set to put forward concrete proposals for the European Green Deal and Next Generation EU by summer 2021. And, with COP26 coming up in November next year, the time is ripe for Sweden to come forth as a leader on climate within the EU. Nationally, the Swedish government should shape the narrative around recovery funding to focus on the opportunities for a green transition and the role of the EU as a global leader on climate issues. A first such opportunity is offered by the United Nations Climate Ambition Summit on 12 December.

And, to add another layer to the discussion, for Sweden there could also be a geopolitical interest in shaping the EU’s environment agenda. The green transition will decrease the EU’s dependence on Russian gas, thereby possibly furthering Swedish fundamental security interests. If Russia’s response to this is to green its own economy, this would not only contribute to a better environment in the Baltic sea region, but could also open up new avenues for the EU’s “selective engagement” with the country, in an area where Sweden itself has maintained relations with Russia. Sixty-nine per cent of Swedish respondents in the Eurobarometer in March 2020 thought that the EU should do more to assist non-EU countries to improve their environmental standards, while across the EU only 43 per cent thought so. Why not start with the EU’s, and Sweden’s, large neighbour to the east?

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.