Humanitarian emergency in the Mediterranean: ECFR Scorecard briefing

This week, a number of ECFR’s Council members released a public statement, adding their voices to the dismay across Europe at the recent surge in migrant deaths of the coast of southern Europe. According to the United Nations High Commisisoner for Refugees (UNHCR), over 1,600 migrants have already died in 2015 while trying to make the crossing.

The public statement calls on EU heads of state and government to go beyond the ten-point plan issued on Tuesday in immediately restoring an expansive search and rescue operation in Mediterranean waters, and grant it with a mandate and level of funding that match the humanitarian emergency that confronts us. In addition, the statement called on the EU to adopt a range of measures in response to the crisis including:

- Setting up a system of relocation within the EU to reduce the weight of the burden falling on a handful of member states;

- Substantially increasing the UNHCR quota system, and to apply it on an equitable basis

- Promote and fund the temporary accommodation of refugees outside the EU through the construction of safe and decent facilities in third countries.

The annual ECFR European Foreign Policy Scorecard draws on data, research and interviews across the 28 member states of the EU on national contributions to a collective foreign policy. Scorecard 2015 looked in some detail at the immigration crisis in the Mediterranean, given that according to the International Organisation for Migration, over 200, 000 people tried to make the crossing to Europe by sea in 2014, and tragically over 3,400 lives were lost. This briefing note draws on the data collected on 2014.

Mare Nostrum

Mare Nostrum, the Italian government led search and rescue operation, was set up in October 2013 in response to the drowning of 366 migrants fleeing African countries when their boat capsized a mile from Sicily. The programme, led by the Italian navy, was estimated to cost the Italian government approximately €9 million per month; it received €1.8 million from the European Commission’s external borders fund. Other member states contributed on border management aspects indirectly via the Frontex-coordinated Hermes operation. UNHCR have estimated that while it ran, Mare Nostrum saved the lives of 5,000 migrants who would otherwise have died in sea crossings that year, and picked up 150,000 people in total.

In October 2014, in response to rising numbers of migrants crossing the Mediterranean by sea, the Italian government sought contributions from other member states in order to continue of the search and rescue operation. The UK led opposition to this request with public statements from Home and Foreign Office ministers who argue that the search and rescue operations created a “pull factor”, encouraging more migrants to cross to Europe by sea. Other states, including Germany, refused at the Council discussions to commit national resources to the operation.

It should be noted that other EU states with southern sea borders, including Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Malta and Spain, were also committing national coast guard resources to arrivals off their own shores.

Mare Nostrum was consequently replaced by Triton, a far more limited border patrol operation that only covers waters close to the European coast. Led by Frontex, the operation had an annual budget of €5 million at the outset. Responsibility for any vessels in trouble further out into the Mediterranean was explicitly being pushed back to the countries on the southern side of the sea.

The ECFR Scorecard awarded the EU’s response to the immigration crisis in the Mediterranean a D+ — the joint lowest score across all 65 policies that the Scorecard looked at in 2015 alongside regional security in the Middle East and North Africa region.

The full text and breakdown of scores for the Scorecard component is available here.

Unequal pressure on EU member states from refugee inflows

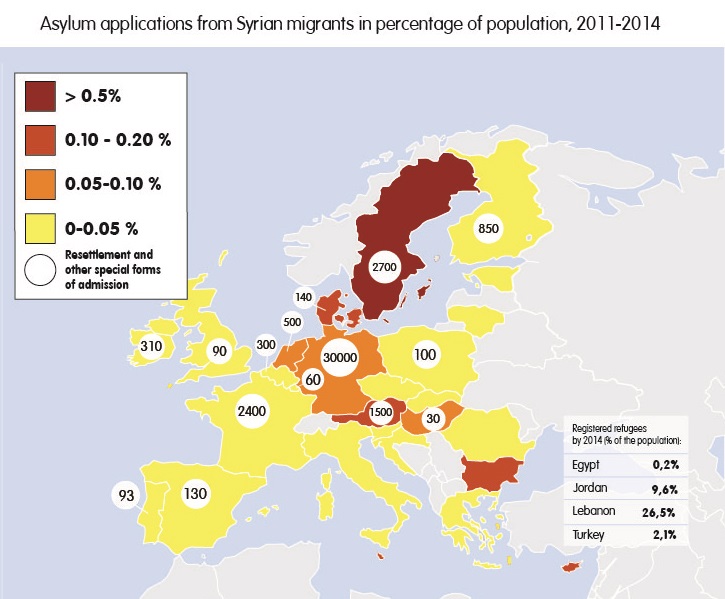

Based on UNHCR refugee data on inflows to EU member states and population data from the World Bank, we have mapped the current distribution of pressure on the EU from the refugee crisis emanating from Syria.

Figure 1 source: UNHCR Syria Regional Refugee Response

Clearly, people fleeing the Syrian conflict are not the only ones attempting to reach Europe by sea. The wave of migration from North African shores is far more complex than that: it is fuelled by turmoil and conflict across the Middle East and parts of Africa, and amplified by the breakdown of state authority in Libya. Indeed in the early months of 2015, people coming from Sub Saharan Africa, including Eritrea, Ghana and Mali, are among some of the largest groups. Still, it serves to illustrate that, if properly managed and resourced, there is significant potential for both increasing EU participation as a whole in the UNHCR quota system, and for greater burden sharing across the EU.

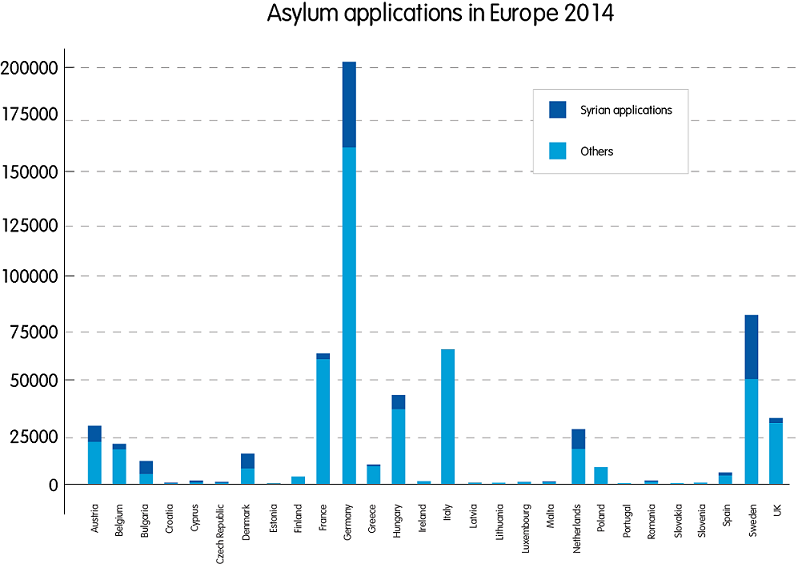

Total figures for asylum applications and resettlement across the EU are broken down here, distinguishing between those fleeing the Syrian conflict and those coming from elsewhere:

Figure 2 Source: Eurostat asylum statistics

Tackling the problems at the source: support to refugee source countries and their neighbours

In addition to measures to ensure that Europe fulfils its humanitarian responsibilities towards those who try to reach our shores, the ECFR Council members’ statement called for EU heads of state and government to promote and fund the temporary accommodation of refugees outside the EU through the construction of safe and decent facilities in third countries.

Scorecard 2015 looked at the different levels of support that member states offered to partners in the region that are dealing with the fallout of the conflict in Syria. A few states stood out as leaders in 2014 either for total aid given, or aid relative to their size and economic strength, or for finding creative political solutions:

- Belgium contributed a total of € 20 million in humanitarian aid to the region, which is substantial given its size. Additionally, it has sent a military plane with 13 tons of humanitarian aid to Northern Iraq.

- Germany is amongst the largest donors of humanitarian aid for Syria, giving €290 million in 2014 alone.

- Ireland is one of the highest per capita contributors in the EU to humanitarian relief, with over € 28 million since the beginning of the Syrian conflict.

- Apart from a very high per capita contribution, Luxembourg was very active as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Councilinitiating resolutions on humanitarian aid and working towards lifting border controls for humanitarian aid transports.

- The Netherlands also gave a significant contribution for a small country, having contributed €123 million in total since the conflict began and €53 million in 2014.

- The United Kingdom gave its largest ever response to a humanitarian crisis, with over £600 million committed to aid for Syria in January 2014.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.