Will Poland be an enfant terrible of the post-Brexit EU?

A Polish-Italian alliance may counteract the Franco-German driving force for European integration.

There is every chance that 2019 will be the most important year for Poland since the fall of communism in 1989. If the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party wins the country’s parliamentary elections in autumn, Poland is likely to follow Hungary’s path towards a semi-democratic regime. A second term for the PiS government would also reinforce Poland’s image among its European partners as one of the most disappointing members of the European Union.

The 2015 parliamentary elections resulted in the first democratically elected one-party government in Poland’s history. The victorious PiS – a nationalist and populist party that supports EU membership but rejects Poland’s accession to the eurozone and wishes to decisively reverse European integration (pushing for a return to voting by unanimity at the European Council) – quickly launched a series of policies under the banner of “Good Change”. Through these policies, the government badly undermined the foundations of the rule of law in Poland. Indeed, as Freedom House concluded, the measures “resulted in a dramatic decline in the quality of Polish democracy”. The organisation estimates that, if the PiS maintains the current pace of its illiberal reforms for another two years, Poland will slip into the category of “partly free” countries – a category that, earlier this year, Hungary became the first EU member state to enter.

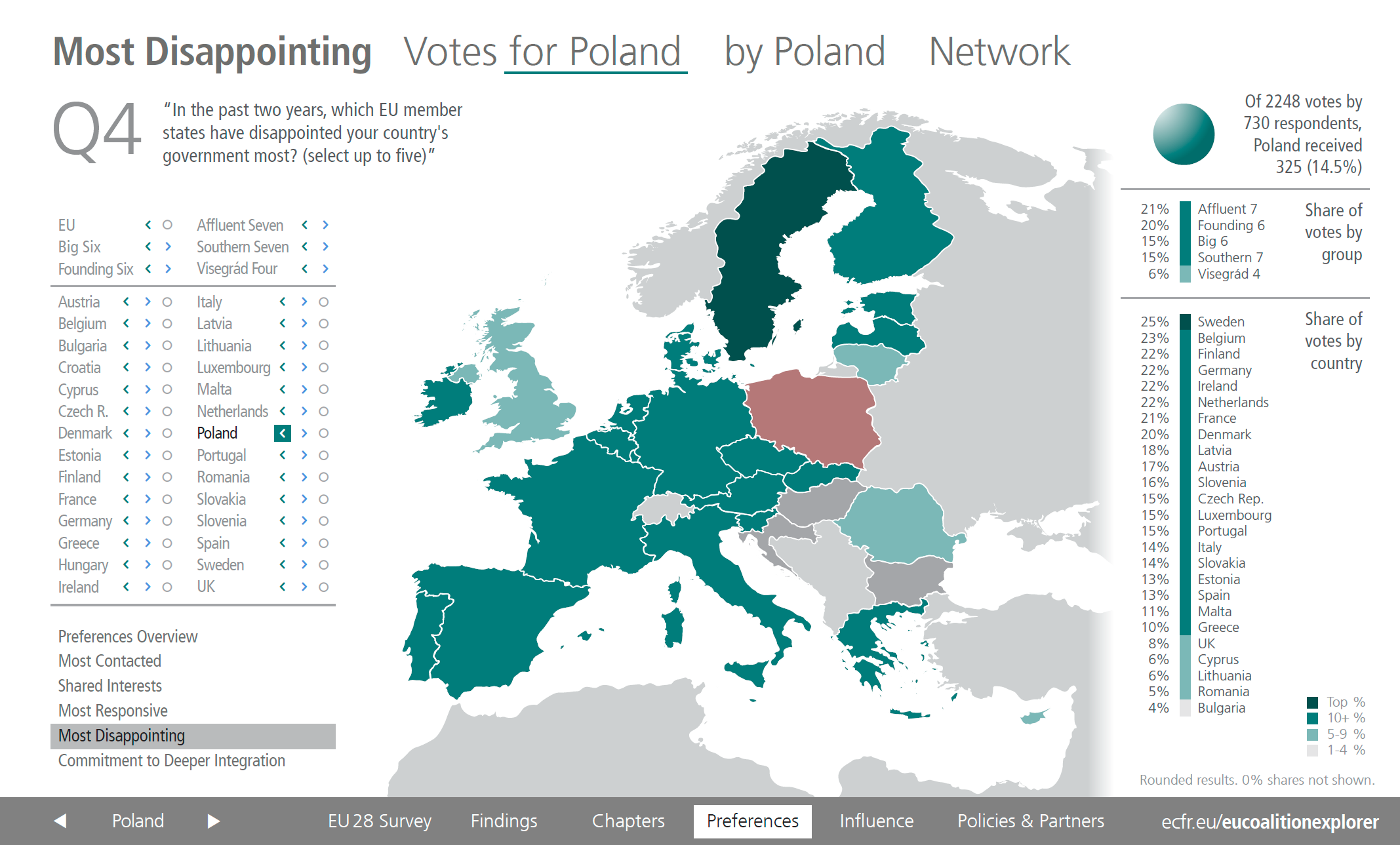

Poland’s Good Change policies put it on a collision course with EU institutions and most member states. Many of Warsaw’s proposed changes, especially those in the judicial system, were incompatible with the European acquis communautaire. This severely tarnished Poland’s image within the EU. According to ECFR’s EU Coalition Explorer, in 2015, few EU members perceived Poland as the most disappointing country in the union. Yet, by 2018, Poland had joined the United Kingdom and Hungary as one of the most disappointing EU members. Each of them received a very similar score of around 15 percent of negative votes from the European experts, diplomats, and decisionmakers who took part in the poll.

This deterioration in relations weakened Poland diplomatically. According to ECFR’s surveys, Poland went from being considerably more influential than Spain, for instance, to significantly less so in just three years. Moreover, while in 2015 German policy experts and policymakers saw Poland as the second most responsive partner among the six largest EU members, they did not even mention whether it was responsive in 2018.

Eastern European countries do not form a homogenous group that unequivocally supports Poland

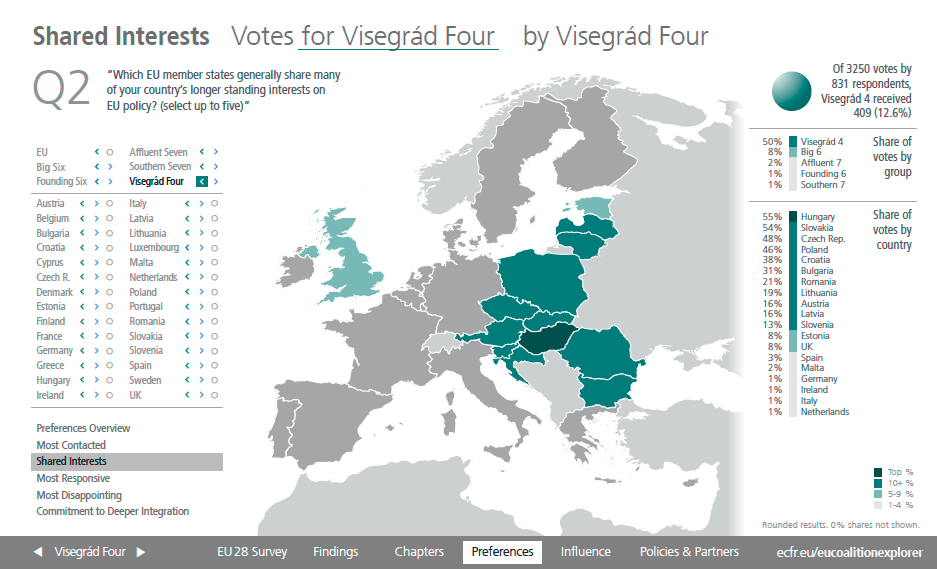

The EU Coalition Explorer shows that, since 2015, Poland and Hungary have established a very close partnership with each other. As ECFR Senior Fellow Josef Janning rightly notes, “in measures of intensity of contact, shared interests, and responsiveness, Polish and Hungarian policymakers and experts listed each other more often than anyone else.” Clearly, despite some serious differences in their relationships with Moscow, Warsaw and Budapest need each other to defend their common positions on the future of Europe and to resist what they see as the EU’s interference in their internal affairs.

The EU Coalition Explorer also confirmed that the Visegrád group (comprising Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic) and EU member states located between the Adriatic, Baltic, and Black seas have become the main point of reference for Poland’s European policy. However, despite the international media’s fascination with the east-west divide, eastern European countries do not form a homogenous group that unequivocally supports Poland. Indeed, the EU Coalition Explorer lists Latvia, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Estonia as more disappointed with Poland than some Spain, Greece, and Cyprus are.

Driven by a fear of aggressive Russian policies and a desire to gain leverage within the EU, Poland has established a very close, albeit asymmetric, relationship with the Trump administration. The rationale behind the large bet PiS has placed on this alliance derives partly from the fact that the administration defines Poland as a “bastion of freedom”. Poland’s overdependence on the United States will most likely grow throughout 2019. For the EU, this means that, on any issue of contention between Brussels and Washington, Warsaw will most likely side with the Trump administration. The recent Warsaw conference on the Middle East, which largely focused on Iran, might be an example of this.

For the PiS leadership, the alliance with the Trump administration is also based on solid ideological foundation. The government in Warsaw’s emphasis on the role of ideology in international relations indicates that it will continue to strengthen its ties with nationalist populists elsewhere in Europe – particularly in the context of the Brexit, which will end party’s alliance with the UK’s Conservatives, and of the May 2019 European Parliament elections.

Thus, Matteo Salvini, Italy’s deputy prime minister and head of the populist League, met with Jaroslaw Kaczynski, Poland’s de facto leader, in Warsaw in January 2019. The League and the PiS were members of the same group in the European Parliament in 2004-2009 and parts of 2011-2014 (a faction of the PiS that split from the party for three years), while PiS currently cooperates with the Brothers of Italy, a smaller version of the League. Moreover, several PiS politicians have already expressed an interest in re-establishing a coalition with the League.

ECFR analysts Susan Dennison and Pawel Zerka stress that while “Kaczynski and Salvini may all agree that migration is the EU’s major problem, they seek radically different solutions […] Salvini and Kaczynski also hold irreconcilable views of the EU’s policy towards Russia.” However, they also have similar policy positions on, for example, the use of force to stop the flow of refugees and illegal migrants across the Mediterranean Sea to Europe. And both leaders support illiberal asylum and immigration laws. This is why the relocation of refugees Dennison and Zerka identify as the main bone of contention between Salvini and Kaczynski may not prevent them from strengthening their relationship. Moreover, the relationship may well benefit from a decline in migration to Italy. In the first ten weeks of 2019, only slightly less than 340 asylum seekers and illegal immigrants arrived in the country – almost 20 times fewer than the number of asylum seekers who reached Spain in this period. Radical differences on Russia do not necessarily preclude an alliance between the PiS and the Legue within the EU. Indeed, the PiS has established a very close alliance with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, one of the most pro-Moscow politicians in Europe.

A coalition between the PiS and the League in the European Parliament could translate into closer cooperation between Poland and Italy in the Council, particularly if domestic support for the League continues to dramatically increase and the PiS wins the Polish parliamentary election. In such a scenario, a Polish-Italian tandem may become the main challenger to the Franco-German alliance promoting further European integration, the rule of law, and liberal democracy.

The EU28 Survey

The EU28 Survey is a bi-annual expert poll conducted by ECFR in the 28 member states of the European Union. The study surveys the cooperation preferences and attitudes of European policy professionals working in governments, politics, think tanks, academia, and the media to explore the potential for coalitions among EU member states. The 2018 edition of the EU28 Survey ran from 24 April to 12 June 2018. Several hundred respondents completed the questions discussed in this piece. The full results of the survey, including the data and its interactive visualisation, the EU Coalition Explorer, are available online at www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer. The project is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe initiative on cohesion and cooperation in the EU that is funded by Stiftung Mercator.

Adam Balcer is the head of foreign policy projects at WiseEuropa and an ECFR associate researcher.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.