Why voters support both stricter borders and respect for human rights

Europeans are largely supportive of stricter border controls – but this may be more down to the huge impact of the pandemic than to the influence of populist parties.

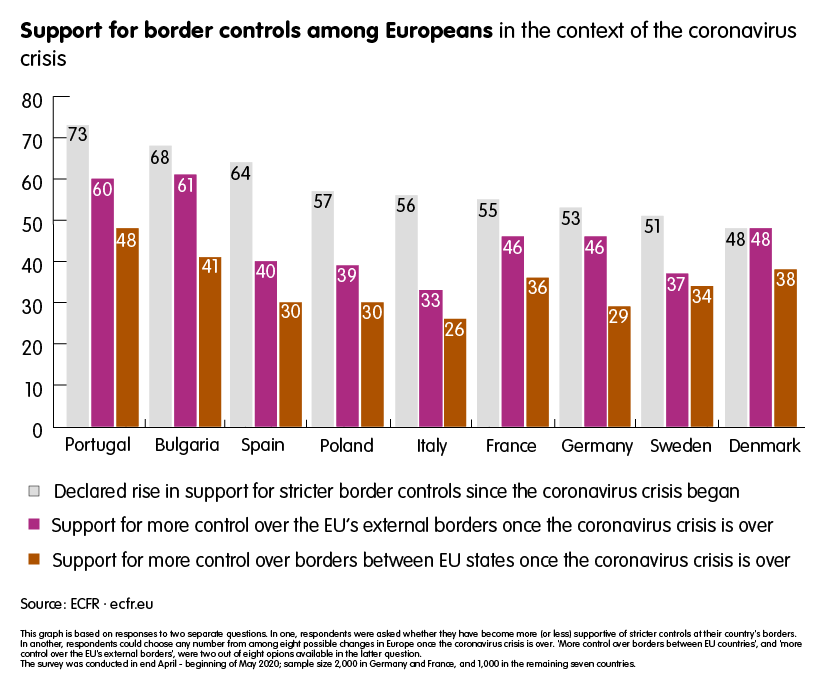

At the end of April, at the height of covid-19 in Europe, ECFR conducted a public opinion poll in nine EU member states. One of its most unequivocal results was a widespread belief that, over the long term, borders needed to be controlled more. Ranging from 48 per cent in Denmark to 73 per cent in Portugal, a substantial share of the population reported strong support for stricter border controls.

At first glance, this finding could be read as a warning that free movement – a cornerstone of European integration – was under serious threat, and that covid-19 could provoke a nationalist turn among European voters. Luckily, that has not happened – and is unlikely to. There are at least five good reasons to believe that this was more a symptom of many people feeling vulnerable – rather than a demonstration of a rising opposition against the Schengen Zone.

To start with, a distinction should be made between support for national borders and Europe’s external borders. When asked about the changes that people would like to see in Europe once the coronavirus crisis is over, only a minority of people called for the European Union to receive more control over borders between member states: from 26 per cent in Italy to 48 per cent in Portugal. At the same time, support for increased control of the EU’s external borders was, in every country, stronger – or much stronger – than that for intra-EU border controls. This may suggest that, if any drawbridge were indeed to be pulled up, people would prefer this to be directed at countries outside Europe rather than the neighbouring member states. It is more about l’Europe qui protège than about a retreat from European integration towards national fortresses.

Secondly, it actually matters a great deal whether people say that they have become “much more supportive” of tighter border controls, or just “a little more supportive”. Voters for populist parties like the Sweden Democrats, Law and Justice, Rassemblement National, Danish People’s Party, Vox, and Alternative for Germany are heavily represented in the former group. Meanwhile, the latter is dominated by supporters of the political mainstream whose overall views are more – or much more – moderate. It is thus likely that the border issue is, for many of the latter, a less salient feature of their political outlook. At the same time, when those who voted for populist parties in previous elections say that they have become “much more supportive” of border control, there are reasons to believe that many of them are simply reaffirming their convictions. After all, firmer border control has always been a core part of the policy agenda of the parties they voted for.

Faith in borders does not equate to an increased desire to restrict migration into voters’ countries or the EU

Thirdly, the reality of the coronavirus crisis is that, in fact, borders went up everywhere within countries over the past few months. The 100 km radius within which one could move in lockdown relaxation in France is one example; another is the restriction on movement placed between federal states in Germany, towns in Spain, and other places. It is therefore possible that with the crisis came a new contract between authorities and individuals who accept that limits on movement is a necessary part of dealing with a health crisis like this. This is another reason why a call for tighter borders should no longer be read as a marker of nationalism per se – since Europeans have now also been living with greatly increased restrictions on movement within countries.

Fourthly, the border issue often seems to be just a sign of a wider sense of vulnerability, also because it is usually accompanied by an apparent rise in sensitivity to other issues. In every country, the share of those saying that, since the coronavirus crisis began, they have become more supportive of respect the rule of law, human rights, and democracy is much greater than the number of those reporting decreased sympathy with such a proposition. Surprisingly, though, that declared rise in support is particularly strong among those who are also saying they became more in favour of tighter border controls. The same goes for people’s support for Europe’s climate change commitments: most Europeans declare increased support for this proposition, but at the same time this is particularly strong among those who favour stricter control of borders.

Finally, it is also worth underlining that strong support for tighter borders has not provoked a shift in support away from European values. According to the poll, a large share of respondents in each country reported increased support for respect for the rule of law, human rights, and democracy. Apart from Bulgaria (38 per cent), the idea of returning more powers from the EU to the national level nowhere receives support of more than one-third of the total population (and just 18 per cent in Spain and 20 per cent in Germany); even if proponents of tighter border controls favour it more than the rest of the population. And in other polls or elections, support for nationalist or populist parties has not risen either. The Law and Justice candidate for this year’s presidential election in Poland, Andrzej Duda, almost lost in July; while support for Lega, Vox, Sweden Democrats, Marine Le Pen, and the two populist parties in the Netherlands (PVV and FvD) has actually weakened since the outbreak of the pandemic.

All in all, widespread support for tighter border controls is largely a sign that people want to regain more control in the broadest sense of the word. The increased importance of borders to voters may serve as a proxy for them to express their current sense of fragility.

This is a warning that policymakers should not jump to conclusions about what lies behind this preference. Faith in borders does not equate to an increased desire to restrict migration into their country or the EU. Rather it seems to indicate a desire for authorities to have the necessary power to control the situation when the next crisis hits, and if, as in this crisis, restricting freedom of movement is part of this response, then effective border control must be part of the toolkit.

Counterintuitively, this finding may also pave the way for a calmer debate on migration in Europe, as this crisis has not simply confirmed existing biases. If internationalists now accept the need for stronger border controls, this could make nationalist voters feel more comfortable that their voice is being heard on the need for control on migration.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.