The Swede spot: Why Stockholm needs flexible coalitions

Sweden needs to stay flexible – and avoid getting stuck in one coalition – if it wants to use its power in the EU to the fullest.

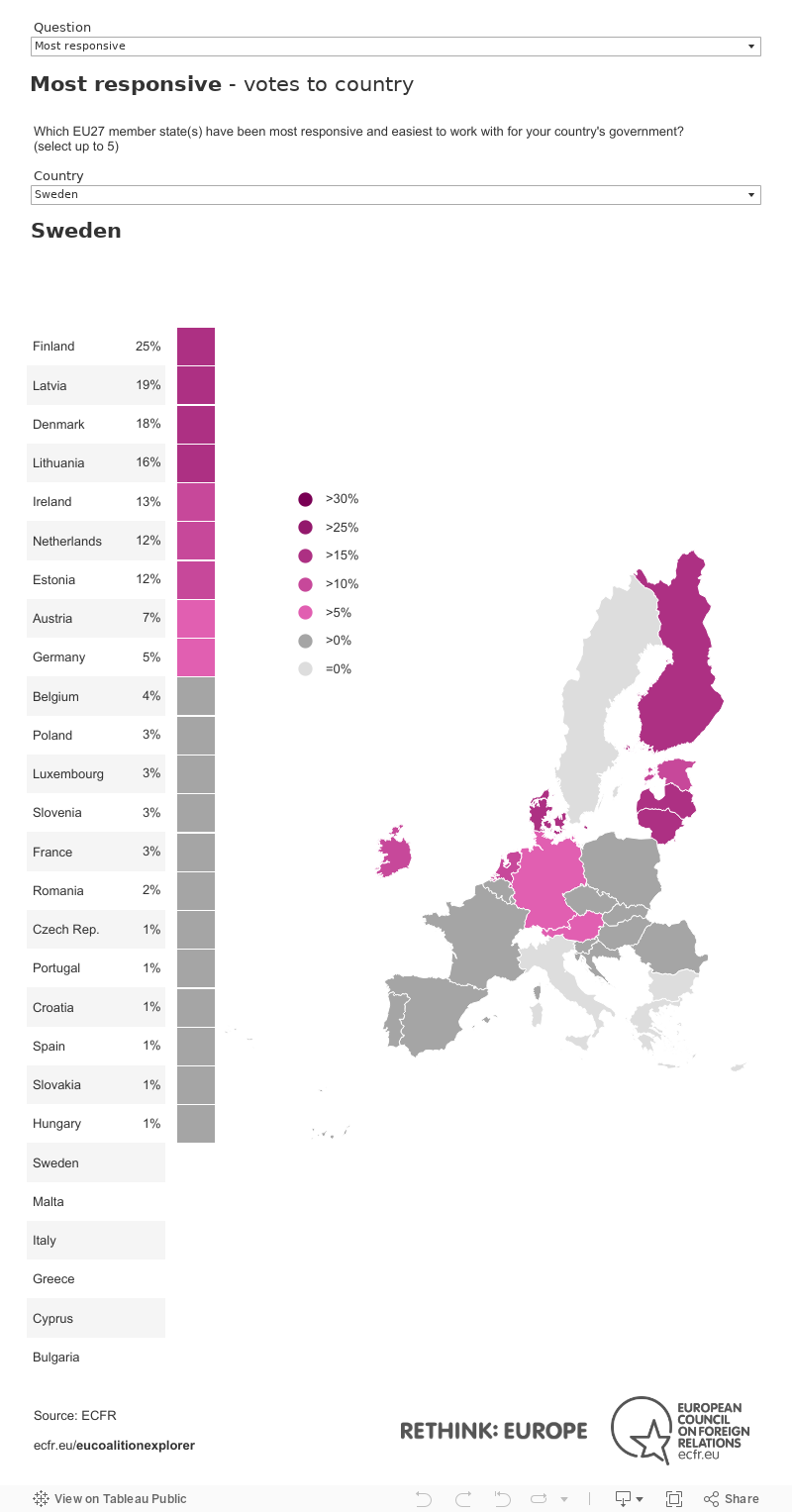

Sweden is the European Union’s master of the art of punching above one’s weight. According to the latest edition of the European Council on Foreign Relations’ EU Coalition Explorer, Sweden is EU27’s fourth most influential state overall – behind Germany, France, and the Netherlands; on a par with Poland; and ahead of countries with larger economies, such as Italy and Spain. Accordingly, it is the most influential Nordic country. Member states in all regions of Europe (except for the south) view Sweden as being very responsive and as having shared interests with them. And they often contact the country.

As reflected in another ECFR survey, Sweden’s image as a responsible partner has been somewhat tarnished by its unorthodox response to the covid-19 crisis. But this does not seem to have significantly weakened the country’s influence in the EU, judging by this year’s negotiations on the EU budget.

There are several explanations for Sweden’s diplomatic success. To some extent, it stems from Stockholm’s investment in a high-quality diplomatic service – something that governments in other countries often fail to make. As a mid-sized country, Sweden needs to build coalitions to make its voice heard and defend its interests. This, in turn, makes it an easier partner to work with compared to more bossy member states.

At the same time, the stability of Sweden’s foreign policy allows it to adopt high-profile positions on issues such as Russia and the EU’s eastern neighbourhood. This has helped Stockholm gain a reputation for leadership in these areas.

Paradoxically, Sweden has gained recognition as one of the EU’s most influential member states at a time when the bloc risks becoming less ‘Swedish’.

Finally, one should not underestimate the value of Sweden’s unique mixture of policy priorities – many of which relate its geographical location. Its priorities quite naturally include issues that are dear to member states in northern Europe (such as climate, the rule of law, and migration) and those in the east (Russia and the single market). And, on all these topics, Stockholm is closely aligned with the respective region. This rare position allows Sweden to be a pioneer in forming flexible coalitions.

Two problems complicate this otherwise rosy picture. The first concerns Sweden’s indispensability to building a more cohesive EU. Other member states rarely see the country as speaking for its region – as France, the Netherlands, and Poland often do (for southern, northern, and eastern Europe respectively). Having such a role would make Sweden not just a popular member state but also an essential player in building compromises within the EU.

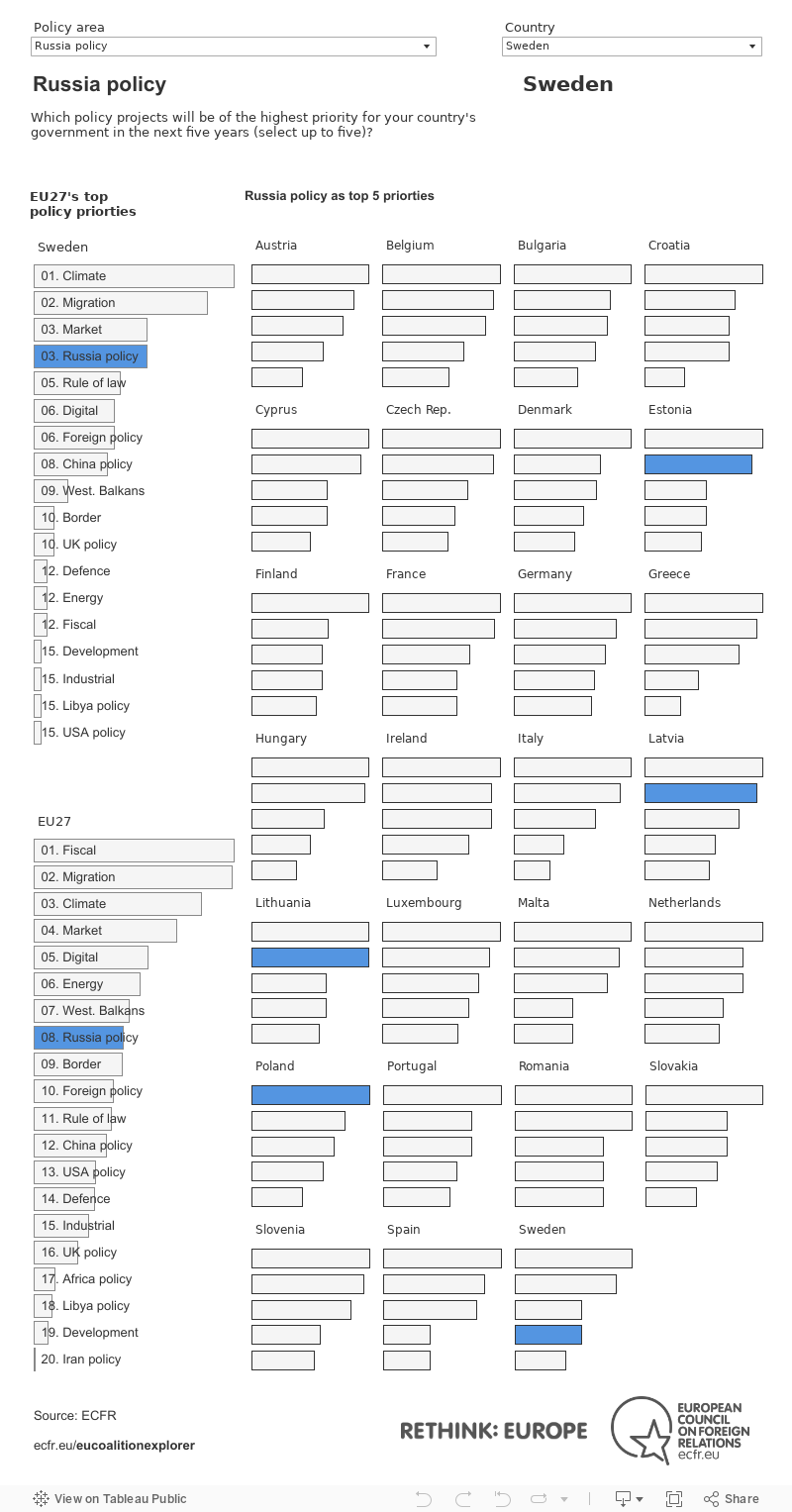

In this, the most straightforward approach would be for Sweden to regain its historical role as a bridge between the north and the east. The country had a long tradition of adhering to this idea, as evidenced by its strong support for the EU’s eastern expansion in the 2000s. Today, however, there appears to be little traffic on the bridge. Russia is the only policy area that Sweden has prioritised in coordination with Poland and the Baltic states – and on which all these countries recognise one another as key partners. The five of them are the only EU member states that include Russia in their top five policy priorities.

Apart from Russia – and, to a lesser extent, the EU’s foreign policy more broadly – there is no area in which Stockholm regards Warsaw as a key ally. All three Baltic states view Sweden as a partner on the single market and energy policy. Estonia and Latvia see Sweden as a close ally on fiscal and digital policy. And, on Russia and single market policy, Estonia is more focused on working with Sweden than with Finland, a closer country both culturally and geographically.

Still – Russia policy aside – Sweden pays much less attention to the Baltic states than to northern and western EU countries. This raises another question: will Sweden become less diplomatically comfortable in the EU in the years to come, by succumbing to the Frugal blues? Paradoxically, Sweden has gained recognition as one of the EU’s most influential member states at a time when the bloc risks becoming less ‘Swedish’: with the United Kingdom’s departure from the bloc, it is becoming harder to defend free trade outside and inside the EU; to promote transatlanticism and an assertive approach to Russia; and to argue that the single market – rather than the eurozone – should be the focal point of European integration.

On most of these issues, Sweden would normally liaise with not just other Nordic countries but also those in central Europe. However, given the rule of law problems in Hungary and Poland, Stockholm prefers to avoid cooperating with Budapest and Warsaw. And it has not yet built strong links with other possible partners in that part of Europe, such as Prague.

In negotiations on the EU’s recovery fund earlier this year, Sweden firmly positioned itself as part of the frugal bloc, alongside the Netherlands, Denmark, Austria, and (on a looser basis) Finland. The prevailing view is that this coalition has been successful: it obtained rebates, reduced the size of grants (as opposed to loans), and pressed hard for conditionality in member states’ access to the fund.

However, this success could cement Sweden’s position within the frugal coalition – a coalition that might lack clout in negotiations on policy areas other than the budget. As a consequence, Sweden may not regain its flexible way of working within the EU, while the frugal states may fail to grow into a wider and more inclusive platform. If this is the case, Stockholm’s influence within the EU could diminish – further undermining Swedes’ happiness with membership of the bloc.

This commentary would not come into existence without conversations with two of my colleagues – Jenny Söderström and Marlene Riedel – who regularly remind me what ‘lagom’ means in practice.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.