Portugal: A good European in search of friends

Portugal has at times punched above its weight in modern EU history. But it needs new friends if it is to do so again

Geography can be both blessing and curse: Portugal, located on the south-western edge of the European continent, looks out on the Atlantic Ocean and back to a history as one of Europe’s great naval powers – a 15th and 16th century story of global ambition and impact. In today’s European Union, however, Portugal has to work harder than other EU members to escape the downsides of being part of Europe’s geographic periphery.

Politically speaking, Portugal finds itself at the heart of European integration. With a good majority of Portuguese consistently supporting EU membership (the country became a member in 1986), Portugal joined the euro currency right from the start, and is also a member of the Schengen Area. Portugal has been instrumental in a number of ways in shaping EU politics over the past decades: Think of the moribund Lisbon Treaty that was rescued under the then Portuguese EU presidency in 2007, or the “Lisbon Strategy” of growth and competitiveness crafted as part of an earlier presidency in 2000 (under prime minister António Guterres, currently serving as United Nations Secretary General). Think of European Commissioner (and currently Director General of the International Organization for Migration) António Vitorino covering the justice and home affairs portfolio in the Prodi Commission (1999-2004), shaping the early years of this new EU policy. Think too of the two successive terms of José Manuel Barroso as president of the European Commission (2004-2009, 2010-2014). At EU level, Portugal has been a visible player over the years, and, while the country was hit hard by the financial crisis and was part of a bailout programme between 2010 and 2014, it has managed to turn a corner since.

Interestingly, Portugal is one of the countries where the past years of crisis have not led to political turmoil and a rise of populist forces. And the country itself is quite confident about its overall EU commitment. Quizzed about the willingness to embark on deeper EU integration (“more Europe”), Portuguese respondents to ECFR’s survey of the community of experts and policymakers rank their own country as one firmly committed to European integration; they only see France as more committed, and, interestingly, they rate Germany less well than France on this matter. Portuguese respondents also like to rank their own country’s overall influence in the EU, although no other group in the survey shared this assessment.

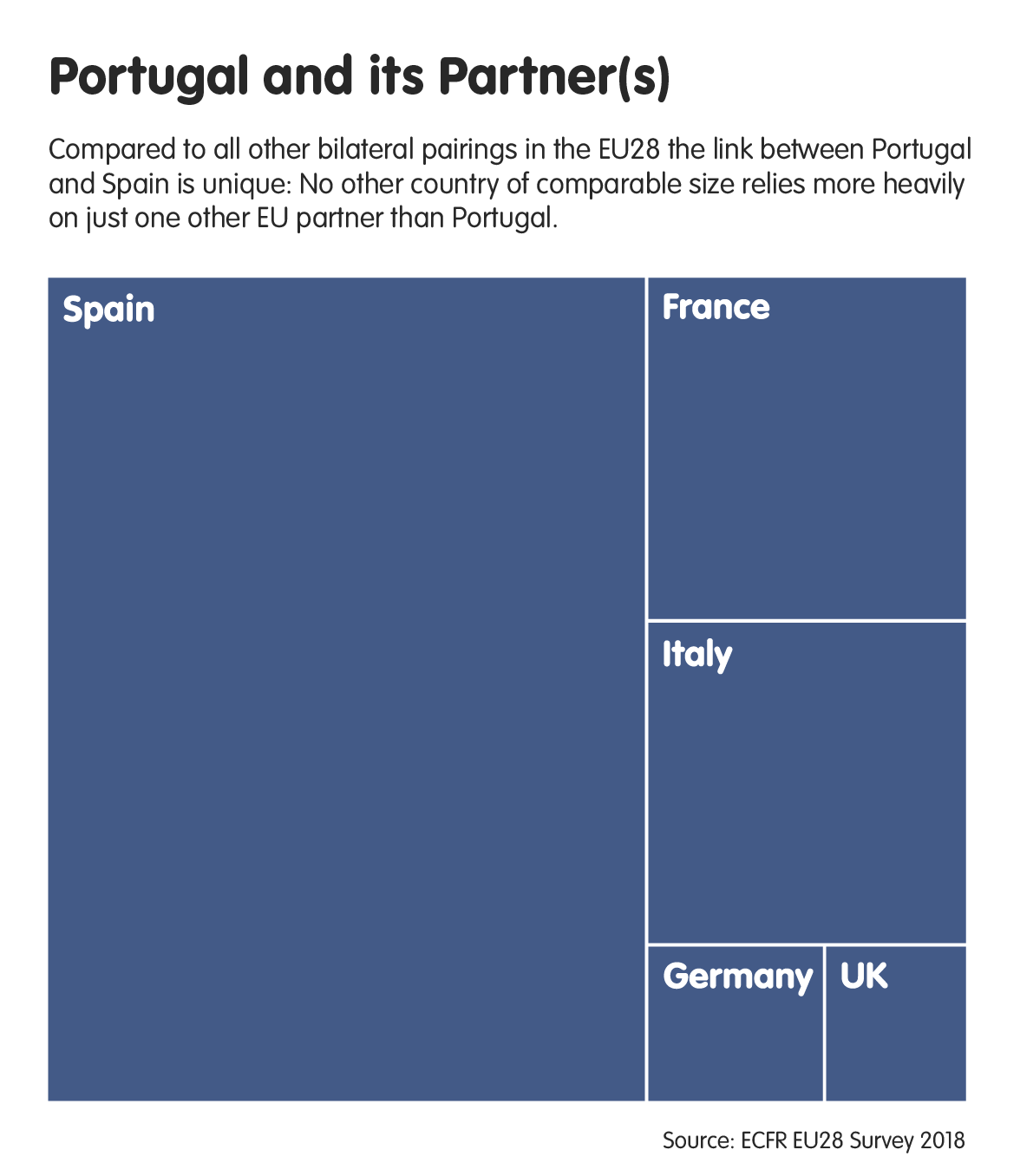

Despite this confidence that it is making its voice heard in the EU, and its good record in Brussels, ECFR’s new EU28 Survey finds that Portugal has only limited choices when it comes to which other member states it can working closely with and form ‘coalitions’ with. In the highly intergovernmental environment of EU politics right now, this clearly is something to work on. The latest edition of this survey shows that, for Lisbon, there really only is one key partner – Spain – to play ball with at EU level. This is clearly a result of its geography, and not enough to be among the movers and shakers of EU politics. If Madrid was a key player at EU level with a clout similar to France, Germany or the Netherlands, this would be a smart strategy. At current stage, however, this is not the case, as Spain is punching below its weight. Still, for Lisbon, Madrid is the most important interlocutor among the other 27 EU members; survey responses to questions around frequency of contacts, responsiveness, and shared interests demonstrate. The relationship with Spain is reciprocal: Madrid also believes Portugal to be an important partner, and sees Portugal as the most responsive EU member state.

Portugal also holds France and Italy to be important partners. Lisbon overall engages more with Paris than with Berlin, but this is a rather one-sided relationship. French respondents’ view reveals that Paris indeed is responsive to Lisbon to a certain extent, but it has other priorities among EU capitals. Italy is another EU member state that emerges on Portugal’s radar of close contacts and shared interests. But, again, Italian responses show that this is a rather one-sided relationship.

Interestingly, there seems to be a new development in relations between Lisbon and London. Compared to the 2016 edition of ECFR’s EU28 survey our latest findings show a growing interest in the United Kingdom. This is clearly related to Portuguese interests affected by Brexit, which Portuguese scholar Lívia Franco in a 2015 ECFR commentary called “really bad news for Portugal”. The fifth biggest foreign working community in Britain is Portuguese, and, from a more strategic perspective, Franco points out that “for more than eight centuries and regardless of the country’s political regime, close political and economic cooperation with Great Britain has been a central feature of Portugal’s foreign policy”. These ties go back to a treaty signed as early as 1386.

Portugal has also traditionally been a staunch supporter of NATO, being located at its southern flank. Because of this it was initially hesitant to join the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) initiative of EU member states in 2017. Security is perhaps another area in which interests between Lisbon and London converge, and these areas explain why in this time of great uncertainty over the UK’s departure from the EU, Lisbon is increasingly reaching out to London. After Spain, France, and Germany, the UK is the fourth most contacted country for Portugal (though numbers are overall significantly lower). Portuguese respondents also see a level of shared interests with the UK that matches their responses about shared interests with Berlin. However, this interest from Lisbon in things British is not reciprocal. Portugal sees the UK to a certain degree as responsive to its outreach, but ECFR’s data suggests that, from Lisbon’s perspective, London could be a more dynamic partner.

When it comes to Portuguese priorities regarding EU policies in the next five years, respondents from Portugal give highest priority to ‘Eurozone governance and a single fiscal policy’. Again, there is a great deal of convergence with respondents from Spain, and both countries see each other as important partners in this area. Respondents from France, Germany, and Italy also view eurozone governance as very important. However, when it comes to finding partners to advance a joint agenda with, Portugal is not a top choice for these countries. Size certainly matters here, but Portugal could be more ambitious in playing a bigger role among the “big four” eurozone members, in particular since three of them (except Germany) generally have it on their radar screen.

Portugal could, for example, build on its past legacy of sorting out fundamental issues of European integration and help advance a eurozone reform file. Lisbon will, perhaps, find it easier to trigger interest in Paris than in Berlin. For this reason, Portugal should seek to increase its clout in Germany, the other key country when it comes to shaping the eurozone reform agenda. There is an opportunity to strengthen ties with Berlin is very practical terms, as Portugal will be taking over the EU Presidency from Germany in the first half of 2021. Preparations in Berlin for the 2020 presidency are already under way.

Portugal could build on its past legacy and help advance a eurozone reform file

The changing transatlantic context further suggests that stronger engagement with Berlin on European security might be a way to capture its interest. At the moment, there is an interest in Berlin in both strengthening the European pillar within NATO and getting PESCO in the EU framework off the ground. Portugal was initially rather hesitant to endorse PESCO, precisely because of its strong NATO affiliation, but eventually decided to join in to avoid falling behind in an important future area of EU cooperation. The country would certainly be well advised to stay within the hard core of European integration to counter its peripheral geography.

There is another angle to Portuguese foreign policy that might interest Berlin: Lisbon’s ties to London. Portugal could present itself as a country bridging the widening gap between the UK and the EU once Brexit becomes a reality, in particular on issues of European security.

The EU28 Survey

The EU28 Survey is a bi-annual expert poll conducted by ECFR in the 28 member states of the European Union. The study surveys the cooperation preferences and attitudes of European policy professionals working in governments, politics, think tanks, academia, and the media to explore the potential for coalitions among EU member states. The 2018 edition of the EU28 Survey ran from 24 April to 12 June 2018. 730 respondents completed the questions discussed in this piece. The full results of the survey were published in October 2018 in the EU Coalition Explorer. This interactive data tool helps to understand the interactions, perceptions and chemistry between the 28 EU member states, and is available at https://ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer. The project is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe initiative on cohesion and cooperation in the EU, funded by Stiftung Mercator.

This article is part of the Rethink: Europe project, an initiative of ECFR, supported by Stiftung Mercator, offering spaces to think through and discuss Europe’s strategic challenges. For more information on the EU28 Survey and the EU Coalition Explorer, the tool presenting the survey results, go to www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.