Poland’s presidential election: Political chaos and divides on Europe

Polish voters are strongly divided on European issues. An unfair election could intensify these disagreements, threatening to turn Poland into an increasingly problematic partner for other EU member states.

On 6 May, Poles learned that a presidential election scheduled to take place in just four days would not go ahead. The two leaders of the ruling coalition, which is dominated by Law and Justice (PiS), decided not to organise the election, to let the Supreme Court declare it invalid, and to organise a new vote – possibly in July. This was despite the fact that, officially, Polish politicians cannot rely on a formally independent court to make such a decision. In any case, the episode brought to a close the first chapter of the presidential election saga.

The saga has been unfolding for months. In a nutshell, PiS has been determined to hold the presidential election as quickly as possible, to ensure victory for the incumbent president, Andrzej Duda. As things stand, he could win in the vote in the first round. But Duda’s popularity is widely expected to decline due to the economic downturn that will inevitably hit Poland in the coming months, as a result of the covid-19 crisis.

However, the pandemic also has other implications. The electoral campaign has been on hold for weeks, as public gatherings are forbidden. Duda has maintained a high profile sheerly through his official tasks and the favourable treatment he receives from state media outlets. This is not true for other candidates: Malgorzata Kidawa-Blonska (the main opposition party, Civic Platform); Wladyslaw Kosiniak-Kamysz (the pro-European, conservative Peasants’ Party); Robert Biedron (the left-leaning Spring); Szymon Holownia (an independent); and Krzysztof Bosak (the far-right Confederation).

As such, there has been a lack of the fair competition that is a prerequisite of a democratic election. Health concerns related to the preparation and organisation of a vote amid the pandemic – which has just reached its peak in Poland – provided a good reason to postpone the vote. And there was a simple, constitutional way to do so: the government could have declared a state of emergency (natural disaster). Such a decision would have been legitimate in the circumstances – and was supported by the opposition.

But the government did not want to take this course of action, as it would have meant postponing the election until Autumn. Instead, PiS did whatever it could to hold the election in May: it manipulated the electoral code a few weeks before the vote was scheduled to take place, tried to introduce universal voting in the course of just a few days, and offered incentives for members of parliament to support its plan. Ultimately, that plan failed. Even some members of the government’s political camp refused engage in this adventure. In a final attempt to restore unity among them, the leaders of the ruling coalition reached a deal: the government would not carry out the election on 10 May, but would not formally postpone it either. Accordingly, the election would take place at the earliest possible date thereafter.

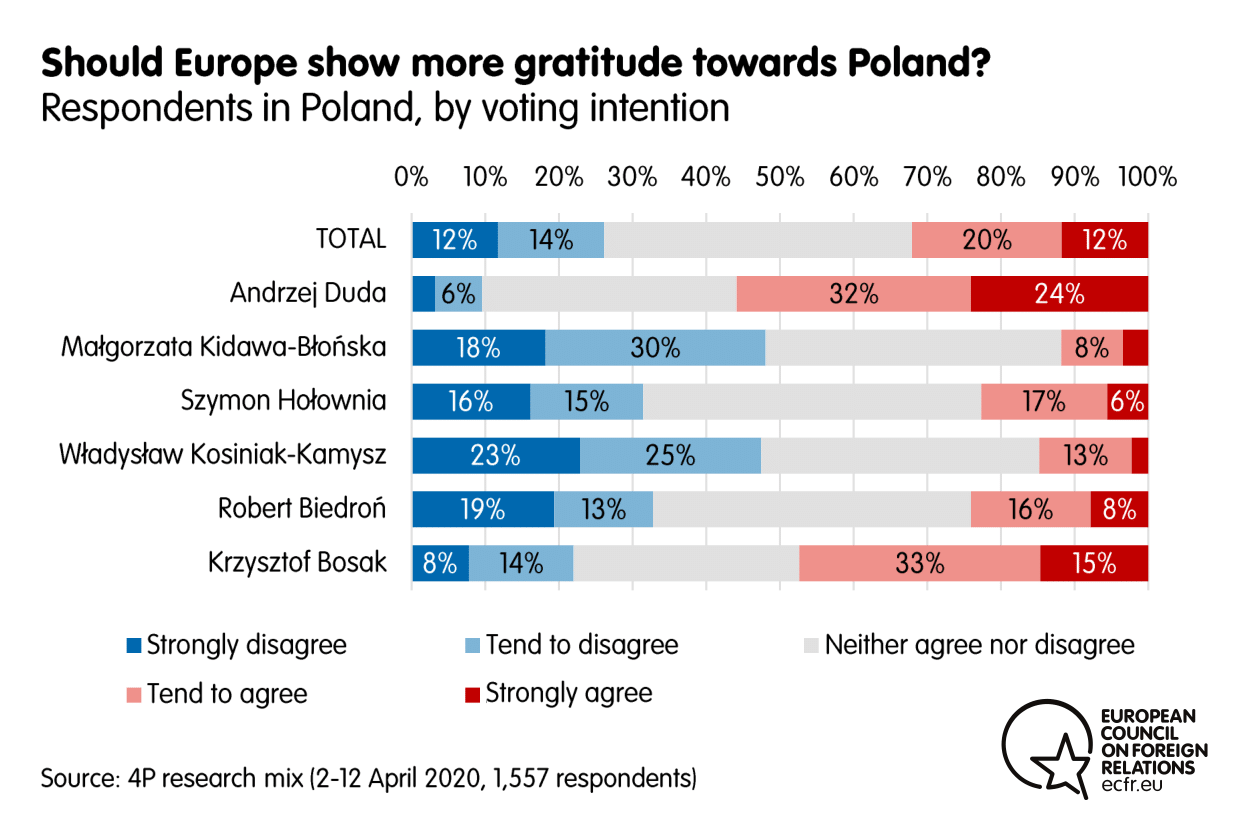

Half of Duda’s supporters feel underappreciated – believing that other Europeans should show more gratitude towards Poland.

Thus, the dubious circumstances surrounding the election, and Poland’s deep political polarisation, will matter a great deal for Europe – not least because Poles are increasingly divided on European issues. This might seem surprising, given that Polish support for membership of the EU is among the highest in the bloc. However, on close examination, the picture is much more nuanced.

The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) conducted a public opinion poll in April to understand how Poles see Europe – in the context of both the presidential election and of the pandemic. The first lesson from the study is that, if there ever was a consensus on European issues in Poland, it’s over now.

Although they have rarely come up during this year’s peculiar presidential campaign, European issues divide the competing political tribes more than any other topic, including the economy and security threats. What explains this? The European Union has been a key actor and a subject of political conflict in the country since 2015. In the years to come, it looks as though the EU will divide the country no less than it did before – and probably even more so.

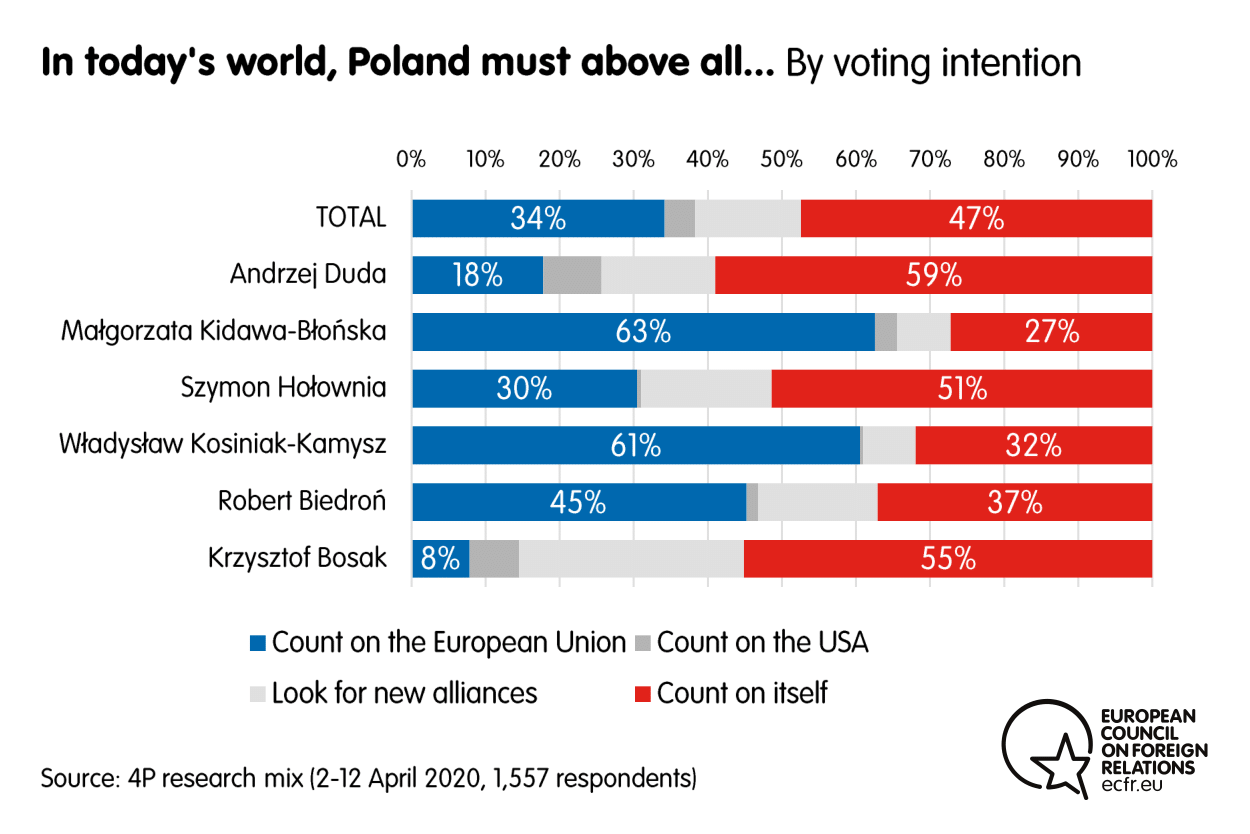

Fifty-nine percent of Duda’s supporters believe that, in today’s world, Poland must rely primarily on itself – rather than the EU, the United States, or other allies. Meanwhile, as many as two-thirds of supporters of Kidawa-Blonska and Kosiniak-Kamysz want Poland to rely on the EU. Overall, one-third of Poles place their hopes in the EU, while almost 50 percent favour national self-reliance.

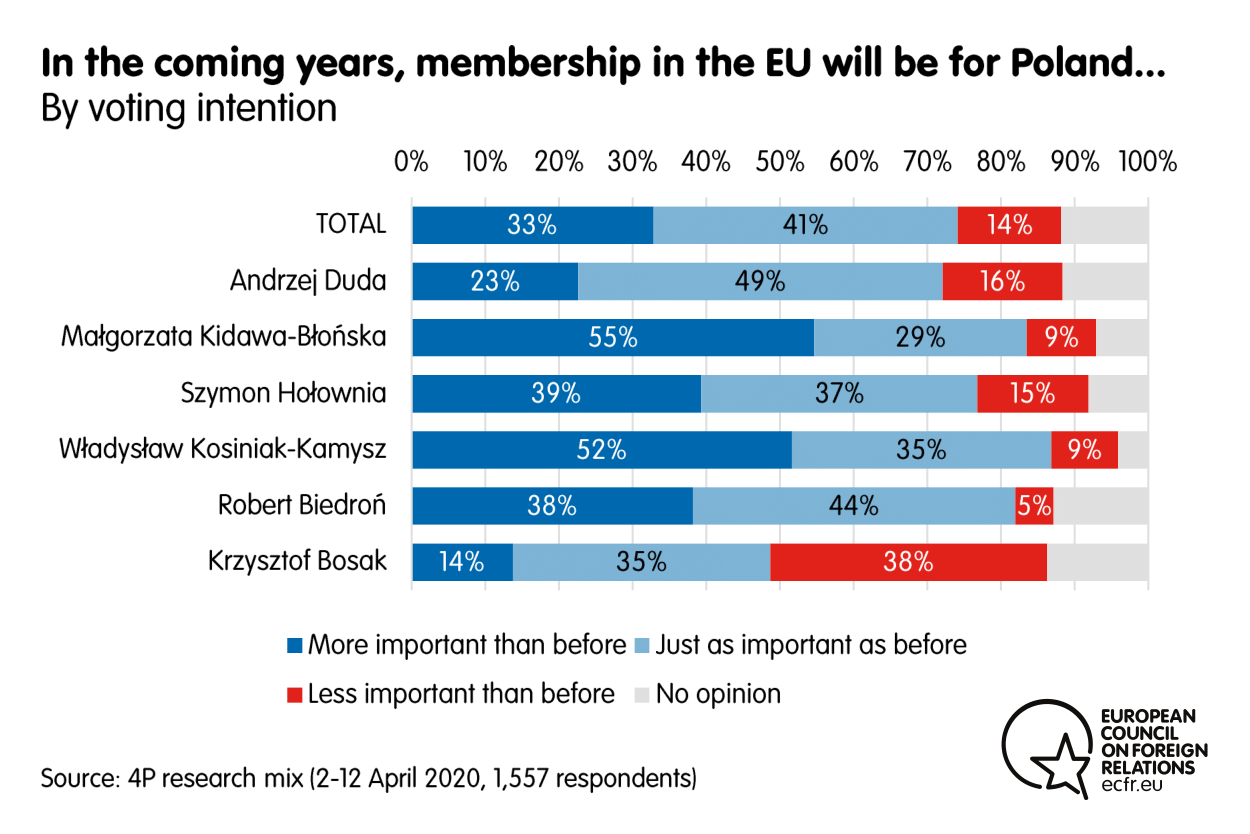

Anticipating the aftermath of the coronavirus crisis, more than half of Kidawa-Blonska’s and Kosiniak-Kamysz’s supporters believe that Poland’s EU membership will be more important in the coming years than it was in the past. But only one in four supporters of Duda share this opinion. Most Poles take a middle view in which EU membership will be as important as it was before.

Europe has also entered into citizens’ emotional sphere. Half of Duda’s supporters feel underappreciated – believing that other Europeans should show more gratitude towards Poland. Among supporters of opposition candidates, this view is much less common.

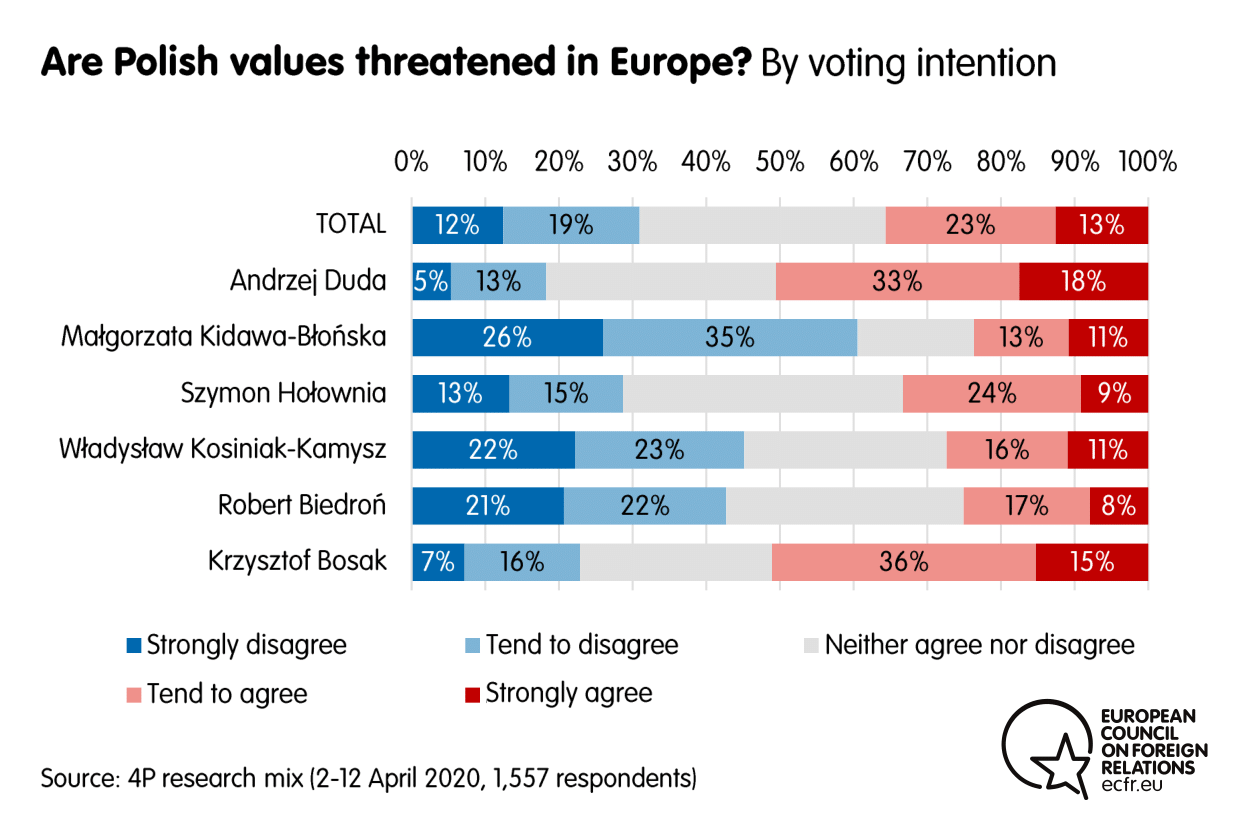

Meanwhile, half of Duda’s supporters (and 37 percent of all Poles) are of the opinion that Polish values are under threat in the EU. Among opposition voters, this is a minority view. Interestingly, supporters of Holownia are between the two poles on this issue – as they are on many others.

While divides over the EU are nothing new in member states, there has been a widespread tendency to see Poland as an exception to the rule. This is because, as Eurobarometer surveys indicated, the EU seemed for a long time to be at least as popular as Catholicism in the country. But ECFR’s study shows that Poles are now not only strongly divided on European issues, but also not quite as enthusiastic about the EU in general as one might believe they would be.

Perhaps the covid-19 crisis has revealed a decline in the country’s zeal for Europe in recent years. Or maybe this enthusiasm never ran very deep in the first place. Whatever the truth, one should not take such enthusiasm for granted – as demonstrated by, among other things, the Poles’ approach the rule of law, migration, the climate, and economic cooperation. All these topics are closely linked to current debates in Europe about the meaning of solidarity.

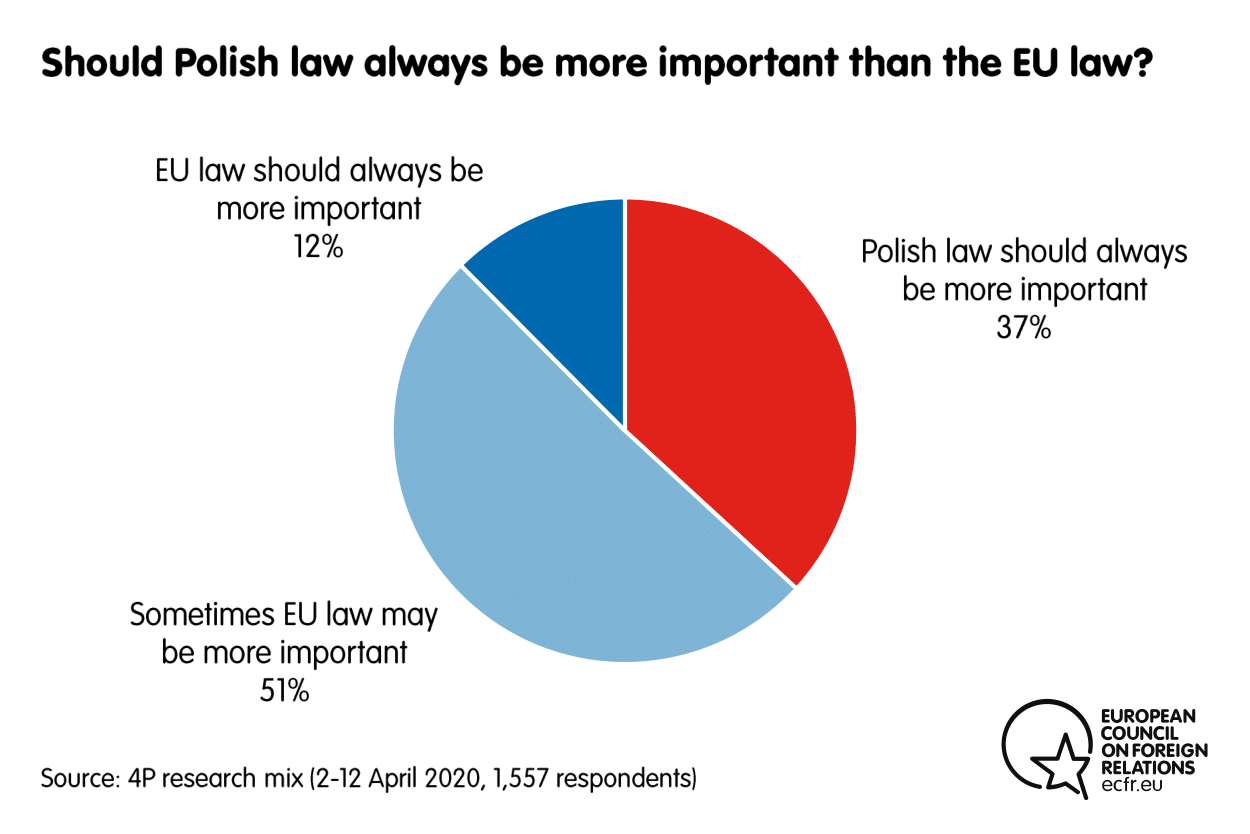

To start with, there are clear divisions between supporters of the ruling party and those of the opposition in the ways that they conceive of sovereignty. Two-thirds of voters who back Duda believe that Polish law should always take precedence over European law. Just 7 percent of Kidawa-Blonska’s supporters share this opinion. More important, however, is the fact that as much as 37 percent of voters believe that Polish law should always be more important than EU law. That’s not what Poland signed up for when it joined the bloc, in 2004.

On migration and climate policy, it is not so much about what Poles have committed to but what they would be ready to accept. Here, there is a great deal of uncertainty about their willingness to engage in key European initiatives.

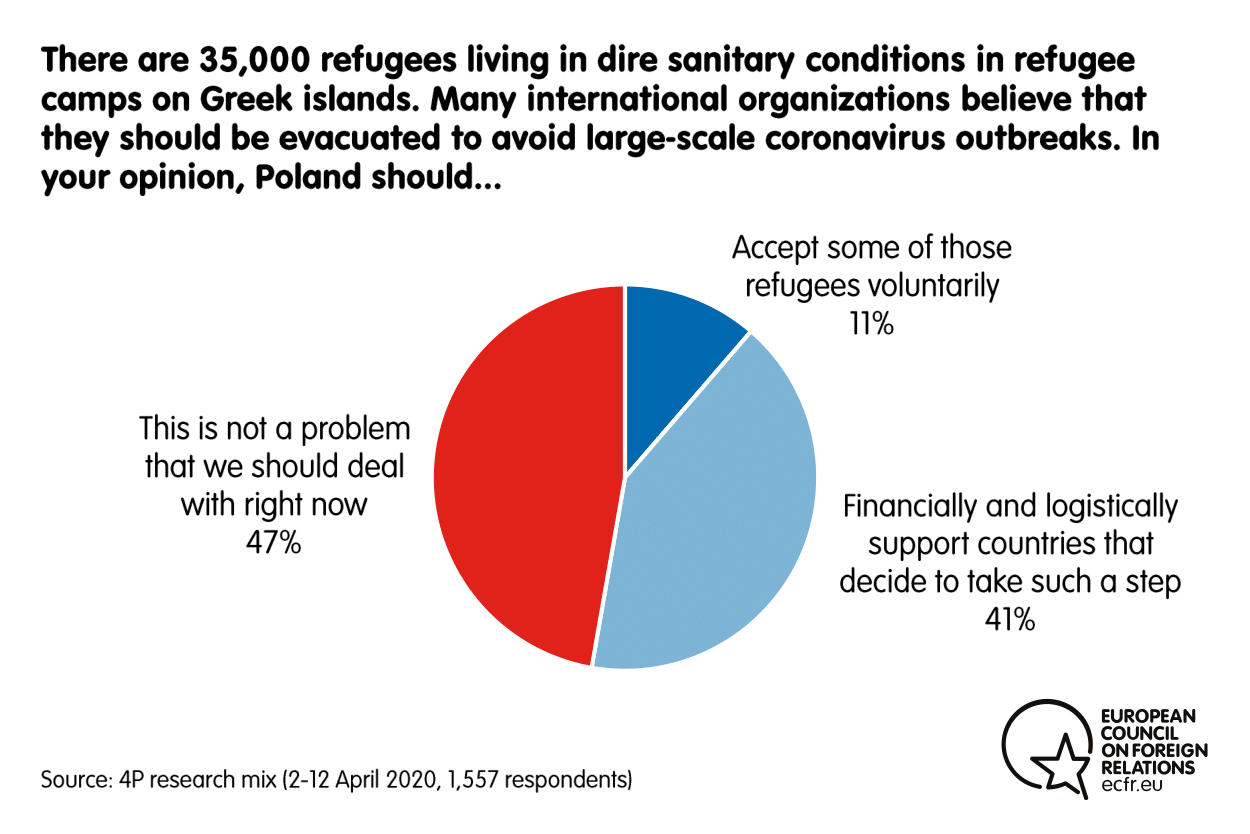

Predictably, supporters of Kidawa-Blonska, Kosiniak-Kamysz, and Biedron are much more likely than Duda’s backers to favour the relocation of some refugees to Poland from crowded camps in Greece. However, half of all voters think that the plight of these refugees is not their problem. They don’t seem to feel a need to show solidarity with member states that have been most affected by the issue.

True, around 40 percent of Poles would be ready to support these countries financially and logistically. However, it is unclear how serious a commitment to addressing the problem they would accept. It’s one thing to support symbolic assistance; it’s quite another to approve a significant re-evaluation of the EU’s budgetary priorities or distribution rules.

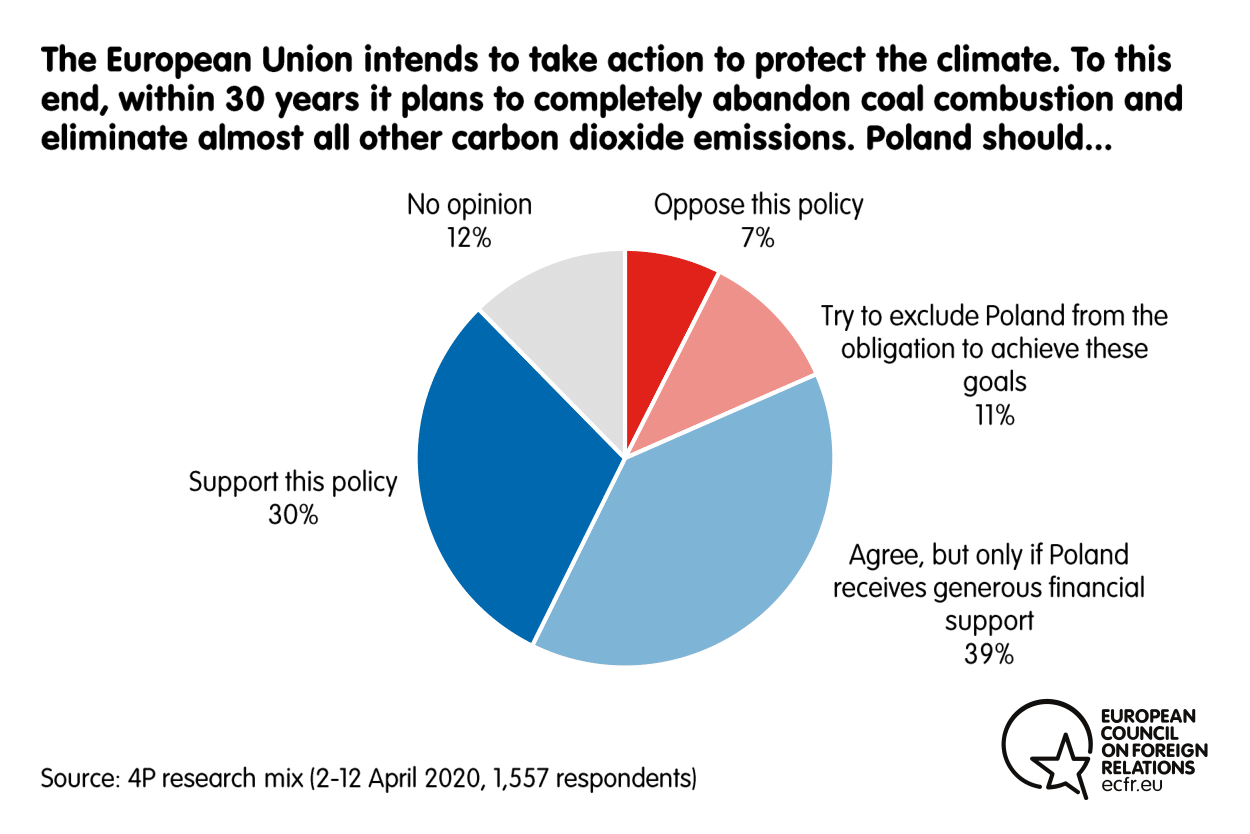

Unsurprisingly, more than half of supporters of Kidawa-Blonska, Biedron, and Kosiniak-Kamysz back the EU’s climate policy – while only 11 percent of Duda’s supporters do so. However, 39 percent of Poles favour a transactional approach in which Poland supported this policy only on the condition that it received generous financial support in return. This view prevails among supporters of Holownia – and is held by one-third of those of Kidawa-Blonska, Biedron, and Kosiniak-Komysz.

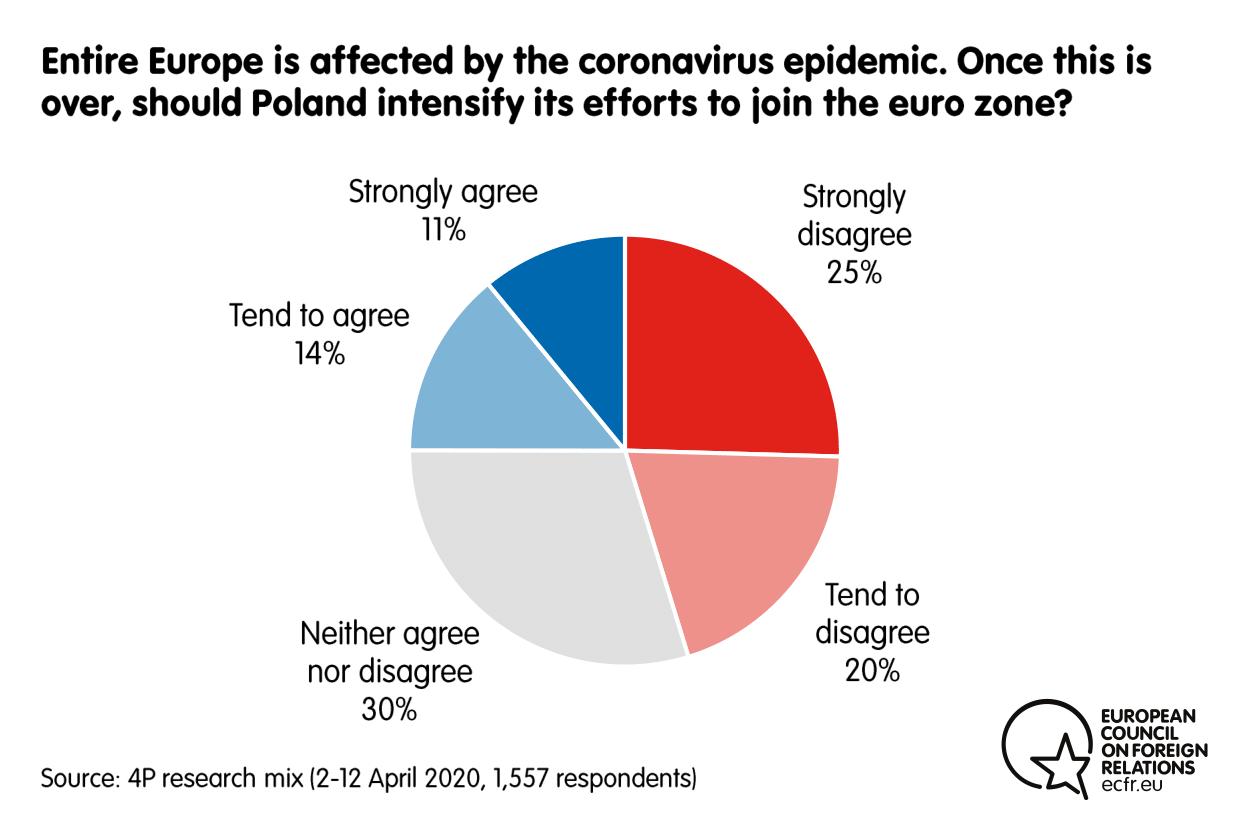

Finally, it’s hard to avoid the question of whether Poland should join the eurozone. For many years, only a minority of Poles have favoured the move. However, it looks as though support for this has sunk to a new low. According to ECFR’s survey, just one in four Polish voters favour strengthened efforts to join the euro area, while 45 percent oppose them. Sooner or later, Poland may need to confront this issue if it wants to stay in the mainstream of European integration.

In all, the upcoming presidential election may add another problem to Poland’s already complicated relations with the rest of Europe. Whoever becomes the next president will have to make difficult decisions about the country’s future in the EU.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.