Poland under Duda: A divided country, dividing Europe

The Law and Justice party has consolidated its power inside Poland by retaining the presidency – but battles with Brussels and a victory for Biden could cause it trouble.

This presidential election has left Poland deeply divided: old versus young; urban versus rural; east versus west; working people versus those receiving social benefits. Attitudes to Europe – beyond mere support for EU membership, which is almost universal – also define one of those key dividing lines. Not only is the Law and Justice (PiS) government actively opposed by half of Polish society; the brutal campaign of its candidate, Andrzej Duda, against his liberal opponent Rafal Trzaskowski intentionally deepened this divide.

A third presidential term is not possible under the Polish constitution, so in his second term Duda will not be eying up another re-election. In theory, this could mean he tries to expand his room of manoeuvre and dissociate himself from his own party. He made some gestures of reconciliation on election night in this respect. However, Duda’s words are unlikely to herald any major shift in policy. In particular, his victory may encourage PiS to clamp down on local authorities, which are often strongholds of the opposition; to purge the judiciary of judges who oppose violations of its independence; and to pick up a fight with independent media. Duda is likely to sign off on such steps.

Furthermore, the ruling party’s dominance will now remain virtually unrestricted for even longer. Since 2015, PiS has not only controlled the president’s office and enjoyed an absolute majority in parliament, it has also effectively seized most of the formally independent institutions of the judiciary, the public media, and state-owned companies. Duda has been elected to serve until 2025 – beyond the next parliamentary election, scheduled for in 2023. This will give PiS at least another three undisturbed years in power until then, while handing the president the power of veto over any possible future government formed by other parties.

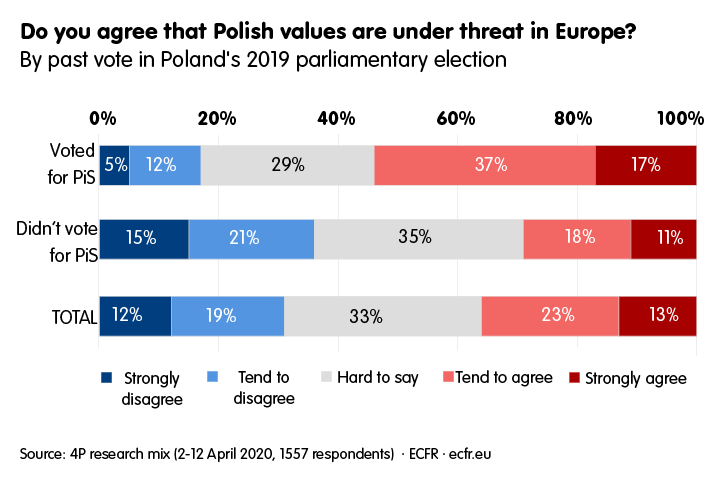

It will be very difficult for the PiS government and Duda to close the divisions within society that they themselves forced apart for electoral purposes. It will also be hard to convince the rest of Europe that the rights of minorities can be respected in Poland, or that Warsaw is a trustworthy partner. Indeed, the ruling party may also choose to instrumentalise European issues (which already strongly divide society, as ECFR earlier commented) to further divide and rule at home. According to a public opinion poll that ECFR conducted in April this year, PiS voters are distrustful of the European Commission – and therefore might actually believe Duda’s and the government’s strained relations with Brussels to be a sign of strength rather than weakness.

The president does not formally play any role in the formulation of Poland’s policy on the European Union but Duda’s re-election has more than a symbolic meaning. His nationalist, anti-LGBT, anti-German, and Eurosceptic rhetoric in the campaign not only helped mobilise his core electorate but also did not go unnoticed throughout Europe. At the upcoming European Council meeting, the negotiations for the EU’s next multiannual budget, as well as the recovery fund, will enter a decisive stage, and will place Poland’s government under international scrutiny.

These talks resemble a multi-level game of chess in which decisions on climate, the rule of law, and the recovery fund, as well as several other points on the agenda, are interlinked, as ECFR explains elsewhere using data from our new Coalition Explorer. There is strong pressure on the EU’s net payers, such as Germany, Austria, and the Nordic states, to urgently help the countries of the south, which have been hit hardest by covid-19 in both health and economic terms.

But governments of the north have also been flagging their uneasiness with the prospect of Poland and Hungary receiving significant levels of funding – which would be the case if the formula recently proposed by the European Commission is eventually agreed. After all, these two countries suffered much less during this crisis than their southern counterparts while also being the most notorious offenders on rule of law, democracy, and minority rights.

Luxembourg’s prime minister, Xavier Bettel, has gone so far as to say: “Using public money for countries where our values are not respected is something which is very difficult to explain”. As unanimity is required to agree the final deal, some sort of a compromise may be inevitable. The president of the Council, Charles Michel, wants Poland to subscribe to the EU’s 2050 carbon neutrality goals as a precondition. And several of the net payers are insisting on rule of law conditionality.

At the end of the day, Poland will have to choose one of two options. It can accept some concessions on rule of law and climate to ensure a generous round of EU funding. Or it can go along with receiving less EU funding to avoid any concessions – thus also putting the pro-Europeanism of the Polish population to the test. In the meantime, it could be tempted to use its veto power to block the EU’s agreement, for which the south is waiting impatiently. But it will be aware that this could be the last and only time it could hit the nuclear option.

Meanwhile, Poland’s partners in the EU face a trilemma. Ideally, many of them would like to achieve three goals: put the pressure on the Polish government on rule of law issues; ensure that Polish citizens do not feel abandoned by the EU; and avoid spending too much political capital on exhausting debates about the rule of law and democracy. However, it might be impossible to achieve all three goals at once.

It will be very difficult for the PiS government and Duda to close the divisions within society they themselves forced apart for electoral purposes.

Some European governments and institutions (such as the Nordic states, or much of the European Parliament) might believe that the first two goals are crucial, and that the budget negotiations provide the perfect opportunity to defend the rule of law within their own ranks by using money as an incentive. But they need to be cautious. If they insist too much on some concessions on the part of Poland (be it on carbon neutrality, membership of the European Public Prosecutor’s Office, or judicial reforms at home), the PiS government might conclude that it prefers weaker links to the EU to any sort of conditionality that would force change.

At the same time, several key governments and figures (such as Germany, or the President of the Commission, Ursula von der Leyen) might actually be interested in keeping the temperature of the conflict with Poland low. In doing so they would dispel hopes that, over the next couple of years, the EU could play a major role in correcting the country’s rule of law wrongdoing. Instead, they be would buying into Poland’s apparent promise to sit quiet and not jeopardise the EU’s attempts to deal with more important issues, from the economic recovery, to climate change, to China.

In this way the EU would tacitly accept that Poland is closely integrated with the rest of Europe in the economic sense – but not in the area of basic values. And PiS would get a free hand to pursue its agenda, even when it involves criticising Europe. After all, PiS and Duda voters appear to want a state that defends and supports traditional values, and believe that ‘Polish’ values are under threat in Europe.

And then comes the transatlantic context. While EU policy is an exclusive domain of the government, the Polish president plays an important role in security policy. Duda, who received open support from Donald Trump during his visit to Washington a few days ahead of the first round of the election, will continue to focus on strengthening Poland’s bilateral partnership with the United States.

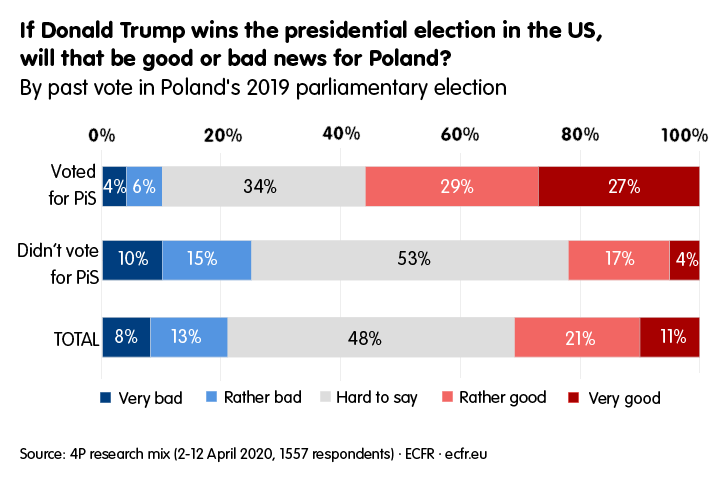

But if Joe Biden wins the election, Duda and PiS will find themselves in a much less comfortable position. Biden may join in with the EU’s pressure to protect the rule of law and minority rights in Poland. The ECFR poll cited earlier showed that PiS voters see Trump’s re-election as good news for Poland, while other voters are not so sure. But then again, Biden’s actual position towards Warsaw remains an open question. Just as with Poland’s European partners, he may also choose pragmatism over a hard attachment to principle. And just as in the European case, such a choice risks writing Poland off for years to come.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.