Czechs and balances: can Berlin shake up the Visegrád group?

Having so far ignored the Czech Republic's interest in working with it, Berlin has a chance to help the country join new coalitions

European policymakers most often see the Czech Republic as part of the Visegrád group, an informal alliance with Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia that aims to protect the interests of central and eastern EU member states. Although Prague has discussed a broad range of policies with its neighbours for more than 25 years, the group has only really caught the attention of the wider European Union since the onset of the migration crisis in 2015. This new prominence stems from the alliance’s strong opposition to hosting refugees who have arrived in Europe in the last three years.

During this period, Berlin has come to see the Visegrád group as an obstacle to a policy that is key to German interests. As a result, German leaders have started to focus on the cohesion of the group, asking whether it is more than a single-issue alliance. In this, policymakers have largely concentrated on Poland’s and Hungary’s backsliding on democracy and the rule of law.

But what are the Czech Republic’s interests and preferences? ECFR’s latest EU28 Coalition Survey of EU policymakers and policy analysts reveals that the Czech Republic is deeply interested in linking up with Germany, but Berlin has largely ignored this.

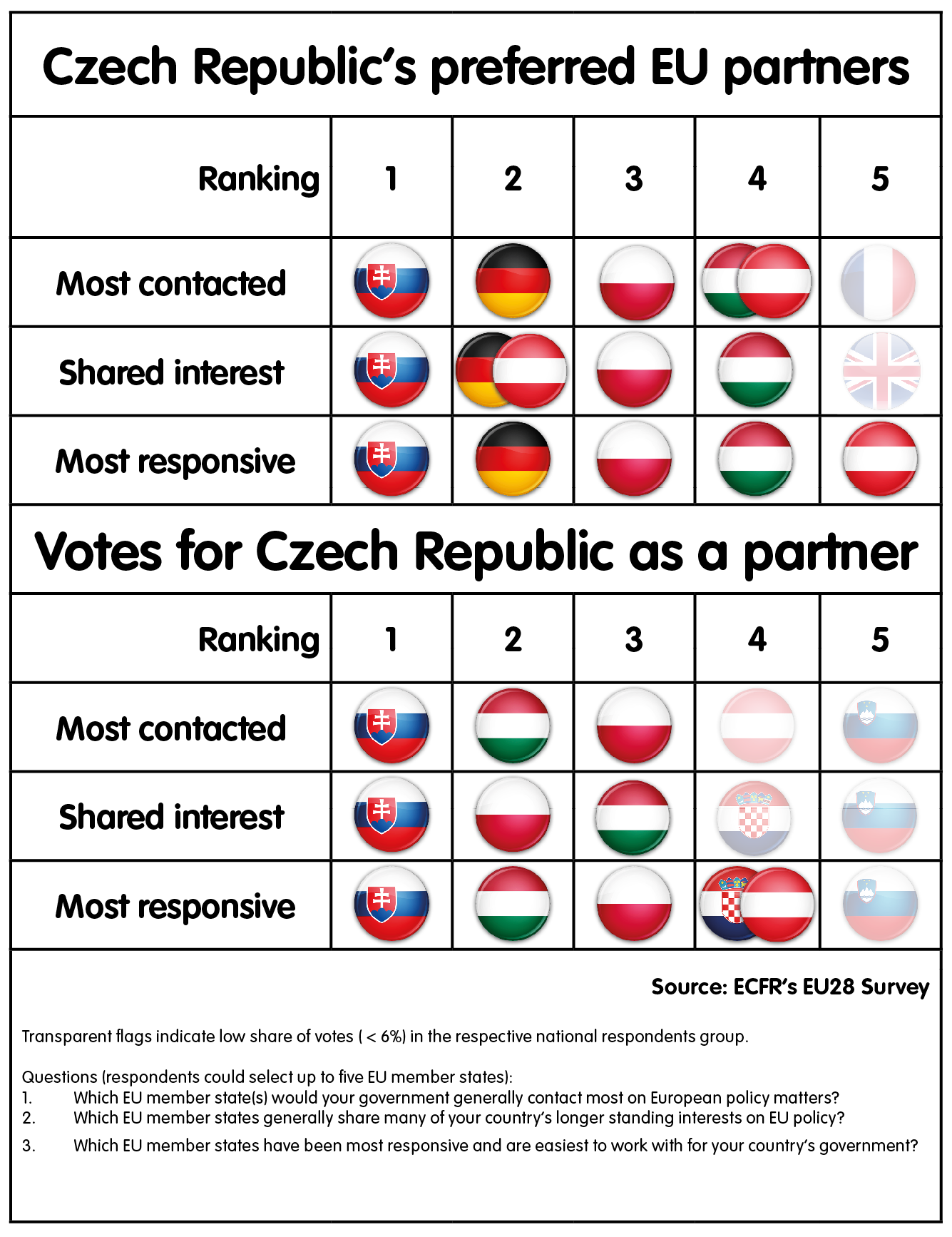

Unsurprisingly, the survey shows that Slovakia is the Czech Republic’s most important partner. Bratislava and Prague contact each other more than any other EU capital, making for a strong and balanced bilateral relationship. The Czech Republic views Germany as its second-most-important point of contact, but this is a one-sided affair: German respondents to the survey did not list Prague among the capitals they contacted most. Due to its unreciprocated enthusiasm, Prague is more disappointed in Germany than almost any other country aside from the United Kingdom.

The Czech Republic may not align with the rest of the Visegrád group across the board, but it has had few chances to join alternative alliances.

Interestingly, Prague is equally disappointed in Poland, the member state it contacts more than any other aside from Slovakia and Germany. Although the Czech Republic’s communicative relationship with Poland is not as intense as that with Slovakia, it is still moderately strong and balanced. In contrast, the Czech Republic’s relationship with Hungary is asymmetric, with Budapest more interested in Prague than vice versa.

Czech respondents to the survey listed Slovakia, Poland, and Hungary among the four countries that are easiest to work with, indicating that members of the Visegrád group maintain healthy working relationships. However – and this is an important finding – they do not always share the same interests.

Although they perceived Prague’s and Bratislava’s interests as being closely aligned, Czech respondents to the survey stated that they had greater shared interests with Austria – a country they also saw as easy to work with overall – and Germany than with Poland and Hungary. (Nonetheless, neither Austrian nor German respondents viewed the Czech Republic this way.)

Although they perceived Prague’s and Bratislava’s interests as being closely aligned, Czech respondents to the survey stated that they had greater shared interests with Austria – a country they also saw as easy to work with overall – and Germany than with Poland and Hungary. (Nonetheless, neither Austrian nor German respondents viewed the Czech Republic this way.)

While Prague has a strong interest in working with Germany, its very weak ties to Paris stand out. Czech respondents had some unreciprocated interest in reaching out to France, but both they and French respondents viewed their countries as having few shared interests. Given that France is, alongside Germany, one of the two most influential EU member states (as Czech respondents recognised), this indicates that Prague’s strategy for shaping European cooperation beyond the Visegrád group focuses almost exclusively on Berlin – which is not playing ball.

According to ECFR’s data, there are some options for alternative coalition-building that Prague may want to test and that might serve its wider interests better. Czech respondents to the survey listed the completion of the single market, the establishment of a common border police and coastguard, and the creation of a common immigration and asylum policy as its top three priorities for EU policy in the next five years. Prague looks primarily to Berlin on the single market, but German respondents did not regard the issue as a priority. The Czech Republic would like to work with the Netherlands – which also prioritises the single-market issue – more than any other country aside from Germany, but Dutch respondents did not see Prague as a preferred partner. Sweden and Denmark also share this priority, but do not look to the Czech Republic to address it. Meanwhile, Vienna is relatively interested in working with Prague, but does not prioritise the single market.

In establishing a common border police and coastguard, the Czech Republic views both Slovakia and Poland as key partners. They reciprocate in general, yet do not prioritise this issue. Germany, Italy, and France also share the priority, but do not look to Prague to address it. Thus, Czech respondents saw Austria and particularly Hungary as more important partners on the issue, as the countries do prioritise it.

On establishing a common immigration and asylum policy, there is most interaction between the Czech Republic and Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and Austria. Yet, among these countries, only Hungary and Austria also prioritise the issue. Again, Prague would like to engage with Germany and Italy as partners, but the countries are not responsive in this area, which they all prioritise.

Finally, the survey shows that the Czech Republic is the member of the Visegrád group most committed to involving all member states in the creation of EU policies. Unexpectedly, given the heated public debate over European cooperation in recent years, ECFR’s latest survey shows that most Czech citizens seem to also support this approach.

Therefore, the Czech Republic may not align with the rest of the Visegrád group across the board, but it has had few chances to join alternative alliances. In this context, Prague’s intense but unreciprocated focus on Germany stands out. To build a coalition with other western or southern European countries, Prague would need to pursue a bold new strategy. As the antagonism between eastern and western member states continues to grow, the Czech Republic may feel that it has little choice but to increasingly take up the Visegrád group’s narrative on migration and other important issues in the coming months.

Germany should not just let this happen. If it is willing to put in the effort, Berlin could help Prague – perhaps alongside the latter’s key partner, Bratislava – amplify its voice with countries such as Austria, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark. It could also help Prague explore alternative partners for cooperation in areas of shared interest.

The EU28 Survey

The EU28 Survey is a bi-annual expert poll conducted by ECFR in the 28 member states of the European Union. The study surveys the cooperation preferences and attitudes of European policy professionals working in governments, politics, think tanks, academia, and the media to provide insights into the potential for coalitions among EU member states. The 2018 edition of the EU28 Survey ran from 24 April to 12 June 2018. 548 respondents completed the question discussed in this piece. The full results of the survey, including the data and its interactive visualization, will be published on 30 October 2018. Findings of the previous edition, held in 2016, are available at https://ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer. The project is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe initiative on cohesion and cooperation in the EU, funded by Stiftung Mercator.

This article is part of the Rethink: Europe project, an initiative of ECFR, supported by Stiftung Mercator, offering spaces to think through and discuss Europe’s strategic challenges. For more information on the EU28 Survey and the EU Coalition Explorer, the tool presenting the results of the expert survey go to www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.