Can Slovakia and the Czech Republic overcome Europe’s east-west divide?

Prague and Bratislava can jointly develop a more visible profile within the Visegrad 4 group and counter the overall dominance of Hungary and Poland

In an effort to address growing disagreement over the direction of the European Union, German Chancellor Angela Merkel travelled to Bratislava on February 7 to meet with the leaders of the Visegrád group (or V4, comprising the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia). The first such event since 2016, the meeting took place against the backdrop of rising tension over the development of democracy and the rule of law in Hungary and Poland, and controversy between Berlin and central and eastern European capitals over the EU’s migration and asylum policies.

The exchange between Merkel and the leaders of the V4 in Slovakia – which holds the presidency of the grouping in 2018-2019 – was highly important. Berlin has a vital interest in ensuring that they remain engaged with the European project despite their manifest differences on EU policy. The growing detachment between the mindset of western European governments and that of their counterparts in central and eastern Europe seems to be yet another sign that the EU is fragmenting. From a German standpoint, this fragmentation threatens to undermine the success story of European unification after 1989.

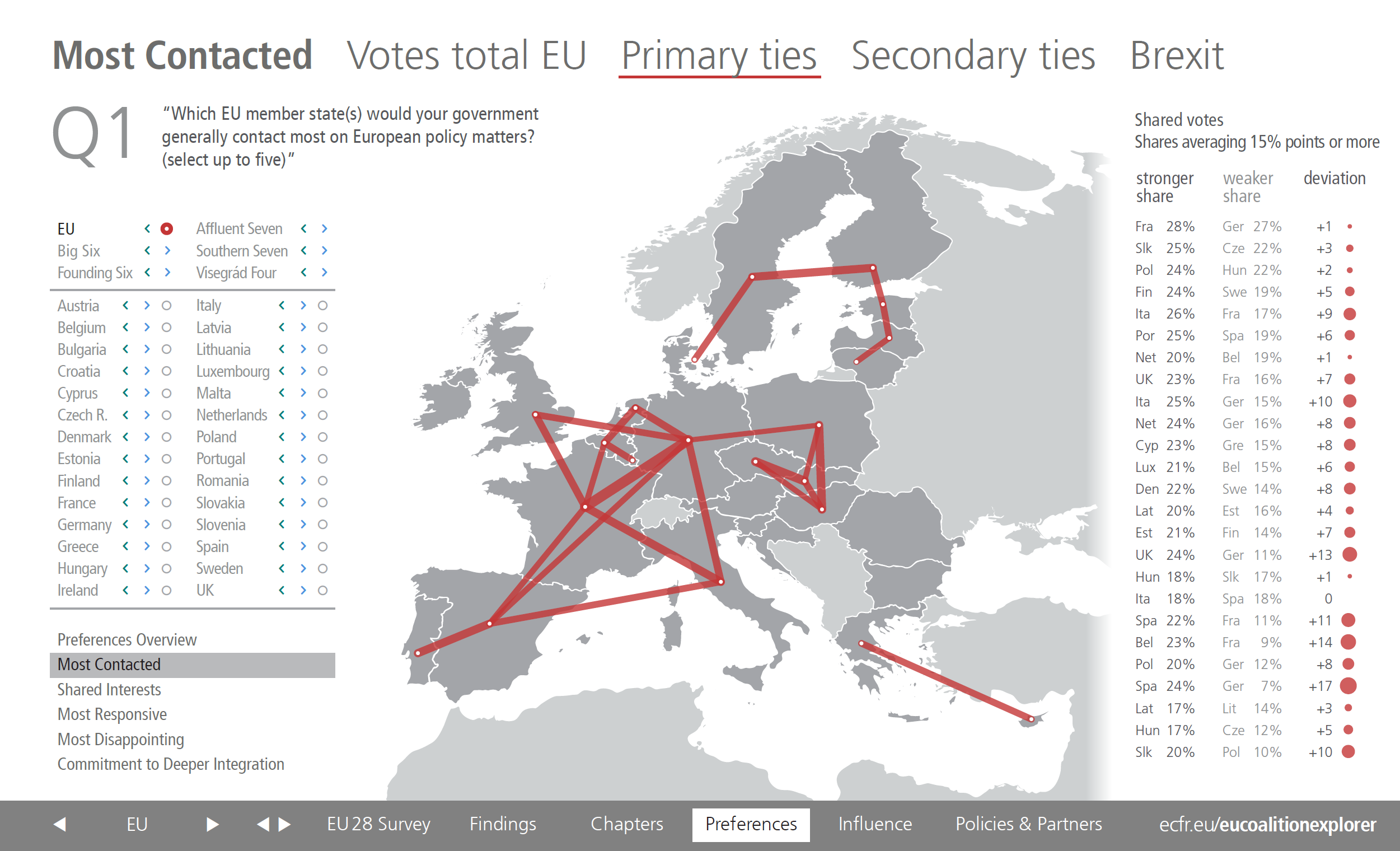

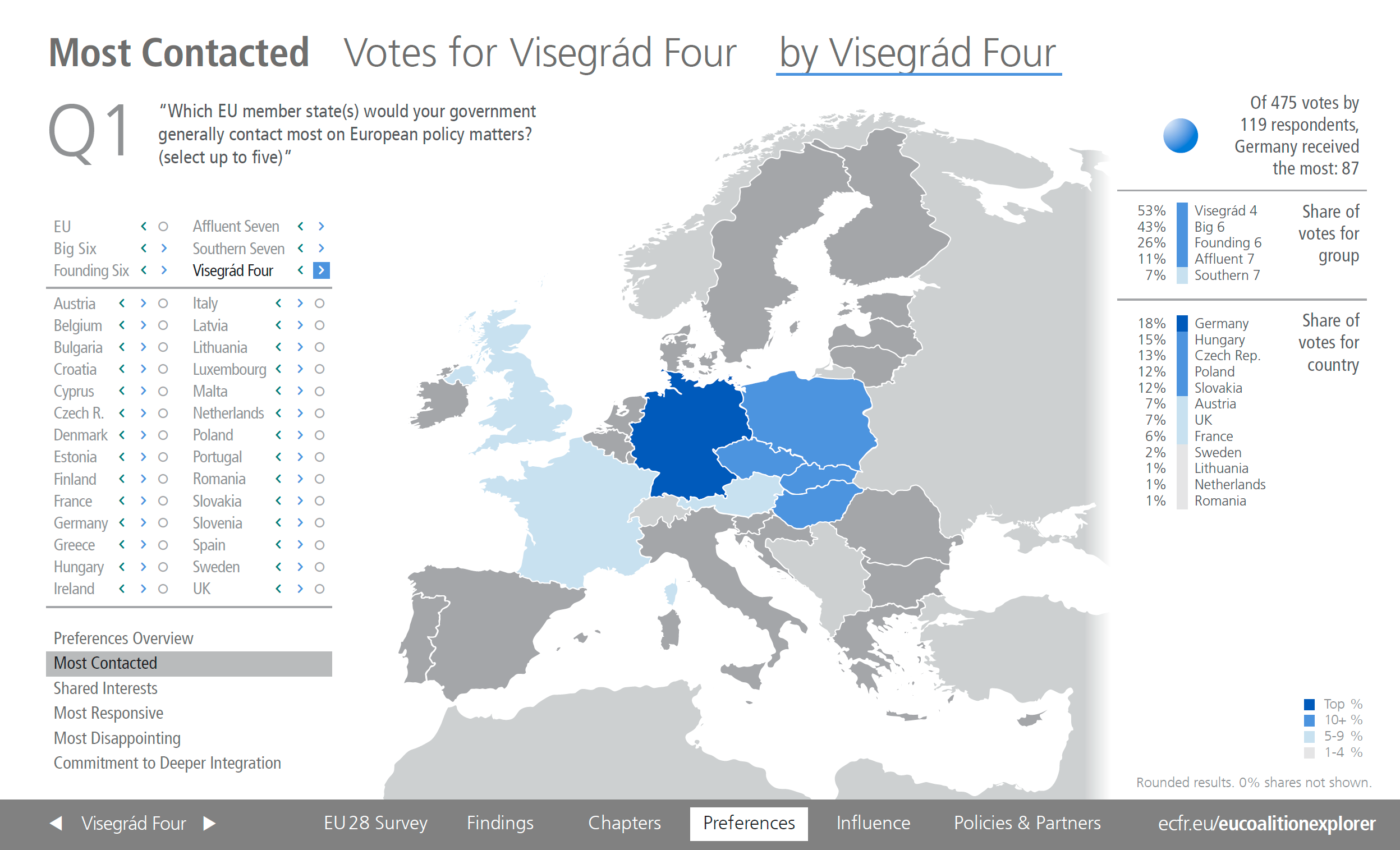

Berlin’s high-level engagement is particularly important to strengthening the feeble ties between eastern and western Europe. In ECFR’s latest EU Coalition Explorer, a pan-European survey of more than 800 policymakers and policy experts on cooperation preferences and patterns of interaction between national capitals, the links between east and west are so fragile as to hardly show up in the data – with the exception of those between Berlin and Warsaw. And, since the publication of the previous edition of the survey in 2016, even the ties between Poland and Germany have weakened.

Berlin has also recently joined Paris in devoting more time to directly engaging with Bratislava and Prague, which form the “small” bilateral partnership in the V4 – in contrast to the “large” one between Hungary and Poland. The former partnership is usually more pragmatic and constructive on EU issues but receives less attention than the increasingly confrontational Budapest-Warsaw alliance, which is more driven by a nationalist conservative ideology.

Bratislava and Prague are also seeking alternative partners in the EU. While the V4 is, in some ways, a convenient format for amplifying central and eastern European voices in the wider EU, Slovakia and the Czech Republic recognise that membership of the grouping comes with costs. Poland and Hungary, which other member states increasingly perceive as spoilers, dominate the V4. More importantly, as ECFR’s Josef Janning has argued, Warsaw and Budapest set off with high ambition to reform the EU but, for the time being, have failed to make substantive progress in this.

Traditionally, both Prague and Bratislava frequently look to Berlin, as ECFR’s Coalition Explorer data demonstrates. However, they are often frustrated with Berlin’s unwillingness to reciprocate. Although the German Foreign Office has established a structured dialogue with both governments, German leaders generally take the Czech and Slovakian governments for granted, perceiving them as relatively amenable partners in the region. However, there are now signs of German re-engagement with them – as illustrated by Merkel’s meeting in Bratislava and the bilateral programme with her hosts she has established.

Under President Emmanuel Macron, France has recently come to seem a viable alternative partner for the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Traditionally, Paris has had less interest than Berlin in countries in central and eastern Europe. Yet Macron has started to reach out to the region (and to Nordic countries) more than his predecessor. This reflects the broader Élysée strategy of developing new partnerships among the EU27. By acquiring new allies in the east, Macron hopes to gain support for several parts of his EU agenda – not least deeper EU integration – and to diplomatically isolate Poland and Hungary. In contrast to the cautious German chancellor, he has taken naturally to the role of opposing Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. But Paris also knows that, by continuously pushing the V4 into a corner at the EU level, western European countries risk driving the grouping closer together.

Macron’s strategy has been, therefore, to engage with V4 countries on policy issues. Both the Czech Republic and Slovakia played along with Macron in a compromise deal on the posted workers directive (while Poland and Hungary took a different view), helping him achieve an early victory on his EU agenda. And, in autumn 2018, Slovakia used its Visegrád presidency to help persuade all members of the V4 to support an EU digital tax. In October 2018, Macron returned the favour by taking part in celebrations to mark the 100th anniversary of the founding of Czechoslovakia, visiting Prague and Bratislava to deliver a speech and engage in a “citizen’s consultation” with Slovakians. Overall, due to Slovakia’s membership of the eurozone, Paris perhaps sees the country as a more valuable partner than the Czech Republic. Indeed, the French and Slovakian finance ministers maintain a close working relationship.

To increase its relevance to other member states, the Czech Republic should come up with a more open approach to eurozone membership

While Austria once appeared to be a natural target of Czech and Slovak diplomacy, this has come to an end under the chancellorship of Sebastian Kurz. Unlike his predecessor from the Austrian Social Democratic Party, Kurz shows little interest in strengthening bilateral relations with Prague and Bratislava. The so-called Slavkov or Austerlitz trilateral format (comprising Austria, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia) that seemed to be forming in 2016-2017 now looks to have been a social-democratic love affair that burned out with a change of governments in Vienna and Prague. Kurz portrays Austria as a western European bridge to the V4 but, in reality, Orbán is the only one of his counterparts he has really engaged with on the regional level – and, even then, just occasionally. Kurz’s signals that his real interests lie elsewhere – in the European People’s Party, Germany, and other parts of western Europe – have prompted both the Czech Republic and Slovakia to look for other EU allies.

Individually, both the Czech Republic and Slovakia find it difficult to punch above their weight when dealing with powerful EU member states such as Germany and France. Both Prague and Bratislava have a size disadvantage in gaining and keeping the attention of Berlin and Paris. Yet they have a strong and balanced bilateral partnership, and – so far, at least – a less complicated relationship with the EU than Poland or Hungary.

Slovakia’s membership of the eurozone is also significant: the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the EU has significantly weakened the grouping of member states that do use the euro, shifting the centre of gravity within the union even more towards the eurozone. But part of the reason why Prague and Bratislava matter more to Berlin and Paris than they once did is that they belong to the V4 – and, therefore, could encourage the group to play a more constructive role in the EU.

Slovak and Czech diplomats have been eager to develop a consensus within Germany and France on policy issues other than migration precisely because they are concerned about becoming increasingly marginalised at the EU level. Slovaks have been more successful in this because of their seat in the Eurogroup and their competent handling of their EU presidency in 2016 following the Brexit vote – which included the “Bratislava process” that shaped the common agenda of the EU27. To increase its relevance to other member states, the Czech Republic should come up with a more open approach to eurozone membership.

The main difference between members of the V4 group is strategic: both parts of the former Czechoslovakia (whose political elites and diplomats still socialise and work closely with one another) see themselves as small states that are politically anchored in Europe. Thus, they are not interested in establishing a regional alliance as a permanent counterweight to Germany or all of western Europe. They have less of a sovereigntist and nationalist outlook on Europe than leaders Poland and Hungary – which is why all recent joint V4 declarations on the future of Europe have been watered-down slogans that lack substance. In other words, they would lose out in the “Europe of the nations” that their Polish and Hungarian partners seek to create.

ECFR’s Coalition Explorer shows the V4 to be an introspective alliance with few visible external ties and little influence. One way that its members could reach out to the rest of the EU is through bilateral projects among themselves – as Slovakia and the Czech Republic have the asset of enjoying the attention of Berlin and Paris at this point in time.

So what should Prague and Bratislava do? This is an opportunity to jointly develop a more distinct, independent, and visible profile within the V4, and to counter the overall dominance of Hungary and Poland without having to engage in open confrontation. The other side of the coin is developing closer links with both Germany and France, and showing a greater willingness to take responsibility for European integration.

Berlin and Paris should follow developments in Prague and Bratislava more closely than they do now. In both Slovakia and the Czech Republic, domestic politics has continued to drift into turmoil in recent months. One cannot take for granted that Prague and Bratislava will maintain their pragmatic approach to important EU issues.

In their ongoing quest to form majorities on EU policies, Berlin and Paris have an interest in keeping the Czech and Slovak governments in their camp – and in preventing the V4 from becoming a more cohesive opposition bloc at the heart of the EU.

By demonstrating that they have the attention of other key EU members, Slovakia and the Czech Republic can gain influence within the V4 and act as key links between western and central and eastern Europe.

The EU28 Survey

The EU28 Survey is a bi-annual expert poll conducted by ECFR in the 28 member states of the European Union. The study surveys the cooperation preferences and attitudes of European policy professionals working in governments, politics, think tanks, academia, and the media to explore the potential for coalitions among EU member states. The 2018 edition of the EU28 Survey ran from 24 April to 12 June 2018. Several hundred respondents completed the questions discussed in this piece. The full results of the survey, including the data and its interactive visualisation, the EU Coalition Explorer, are available online at www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer. The project is part of ECFR’s Rethink: Europe initiative on cohesion and cooperation in the EU that is funded by Stiftung Mercator.

Almut Möller is head of the Berlin office and a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR).

Milan Nič is senior fellow in the Robert Bosch Center for Central and Eastern Europe, Russia, and Central Asia at the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP).

An earlier version of this article appeared on Visegrad Insight on 6 February 2019.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.