America’s trade-off: Israel, Ukraine, and the inescapable China question

The US too often falls for its own superpower myth and fails to prioritise among its foreign policy commitments – including its present China challenge, which has not gone away

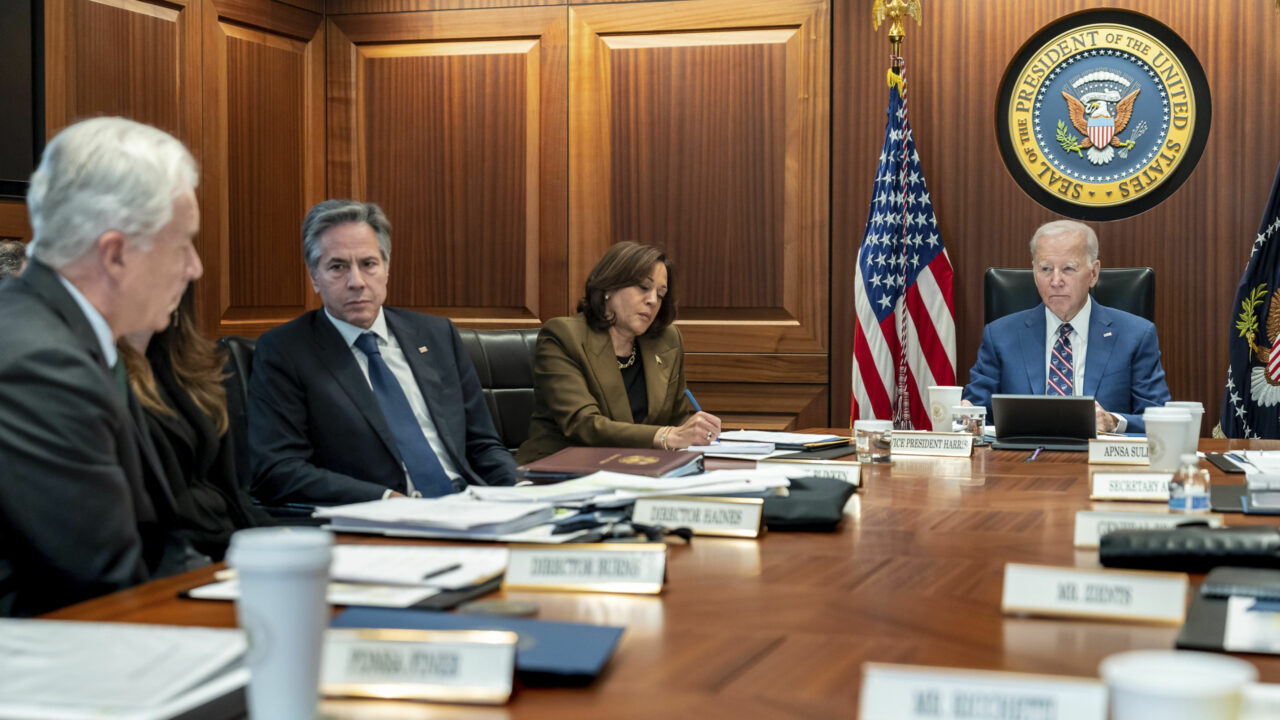

Rule number one in American governance is: never admit to trade-offs. “We are the United States of America, for God’s sake,” US president Joe Biden defiantly told 60 Minutes when confronted with the idea of a trade-off between Ukraine and Israel. “The most powerful nation in the world, in the history of the world. We can take care of both of these [wars].”

Biden’s confidence reflects a long-held view in Washington that the only factor limiting the American arsenal of democracy is political will. The United States is the superpower, the country that invented baseball, online dating, and unwise wars of choice – it can do whatever it sets its mind to. But behind the bravado and national myths, even the very rich and powerful face limits to their power.

For the US, the inexorable trade-offs between the wars in Gaza and Ukraine exist principally on three levels. The most obvious and consequential in the short term is on the very material level of resources. But in the longer term, two more political trade-offs – political capital and domestic endurance – may matter more

Resources

The war in Ukraine has deeply stressed US and Western stocks of certain critical types of ammunition and weapons. The Pentagon has been scrambling, for example, to source artillery shells and to ramp up production in the US and among its allies. So far, it has met with limited success – the US has had to delay weapons deliveries to Taiwan, while the Ukrainian military has rationed shells on the battlefield. The Biden administration decided to ship morally questionable cluster munitions to Ukraine, largely because it lacked sufficient supplies of other types of artillery shell.

Of course, the wars in Gaza and Ukraine are quite different types of conflict and the resupply needs of the Israeli and Ukrainian armies are distinct. “There will be little overlap,” Michael J Morell, former deputy director of the CIA, told the New York Times, “between what we’re going to be giving Israel and what we give to Ukraine.” It turns out, however, that the small overlap includes some of the supplies that have been most scarce in Ukraine – artillery ammunition, precision-guided bombs, and Stinger missiles.

This is mostly a short-term problem – the US and its allies have the capacity over time to increase production and to dip into readiness stocks in an emergency. If the crisis of the moment becomes more severe, they will be more willing to invest in long-term production and to take risks with readiness for other contingencies. But particularly in the short term, the trade-offs in this area remain quite acute and cannot be wished away by fond memories of the second world war.

Political capital

A more important question of long-term trade-offs comes in the form of political capital, both in domestic politics and with allies. The Ukrainian government, according to the Financial Times, is “now wondering if the world has the attention span and courage to focus on two major wars.” But the US government is very well staffed and really can focus on more than one issue at a time – indeed, getting something out of the glare of press coverage can often improve the ability of US policymakers to focus on the key elements of the matter.

The political capital trade-off is more subtle than that. Creating the political will for a war involves not just leaders’ time and attention, but also the need to spend political capital to bring various partners and Congressional constituencies along. When the US asks for help in Ukraine or anywhere else, its allies very often want something in return – be it access to high-tech US weapons or increased deployments of American troops. These can be costly efforts.

Similarly, when the US president asks Congress for funding for foreign wars, factions within Congress will often use the urgency of the request to link it to other issues, such as reductions in overall government social spending. Before Hamas attacked Israel, funding for the Ukraine war was hung up on just that issue. The Biden administration has cleverly decided to use the outrage at events in Gaza to its political advantage and linked the Congressional requests for funding for Ukraine to those for Israel. But, over time, sustaining both will require investments of political capital that is limited.

Endurance

But in the long term, the most difficult trade-off will come on the level of societal endurance. The US tends to tire of its wars. If and when a war bogs down into an indecisive slog, presidents often struggle to sustain enthusiasm in American society for the war they started. Polls show US public support for the Ukrainian war is already softening, though it remains broadly popular.

The two foreign wars together may quickly wear down America’s capacity to endure

If in the coming months, Israel’s war in Gaza proves similarly indecisive and unending, the two foreign wars together may quickly wear down America’s capacity to endure. Biden could soon face the choice of many presidents before him of either admitting defeat or sustaining multiple wars in the face of growing public frustration. As George W Bush and Barack Obama could tell him, this is not an enviable position to be in.

The virtues of prioritisation

All of these inescapable trade-offs imply that, even for a superpower, prioritisation should be, well, a top priority. The Biden administration entered office with this lesson firmly in mind and with a strong sense that it needed to place the struggle with China above US interests elsewhere. It now nonetheless finds itself deeply involved in wars in both Europe and the Middle East, while the China problem continues to fester and grow behind the headlines.

Administration officials would doubtless argue that events have given them no choice but to respond forcefully. The problem is that they prioritised China in the first place because it was a more important problem. Real trade-offs between US foreign policy priorities continue to exist – events cannot change that essential fact. Effective prioritisation requires the courage to not respond as strongly as you might want to in the moment because you need to husband your supplies, your political capital, and your endurance for a bigger fight. That strong notion of prioritisation does not come naturally to a superpower like the United States of America and so its leaders continue to deny the trade-offs. Alas, reality will eventually intervene.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.