Mapping the Yemen conflict (2015)

Yemen’s president recently returned to the country after nearly six months in exile, but the conflict appears far from reaching a tidy conclusion, growing, if anything, more complicated by the day.

President Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi was forced to flee the country by the Houthis – a Zaidi Shia-led rebel group targeted in six wars by the central government – and their new-found allies in the Yemeni Armed Forces, including many key backers of the country’s former leader, Ali Abdullah Saleh. This prompted an ongoing, Saudi-led military campaign aiming to restore Yemen’s internationally-recognised government to power, and now President Hadi and his Prime Minister and Vice President Khaled Bahah have returned to the port city of Aden.

Rather than being a single conflict, the unrest in Yemen is a mosaic of multifaceted regional, local and international power struggles, emanating from both recent and long-past events. The following maps aim to illustrate distinct facets of this conflict, and illuminate some rarely discussed aspects of Yemen’s ongoing civil war.

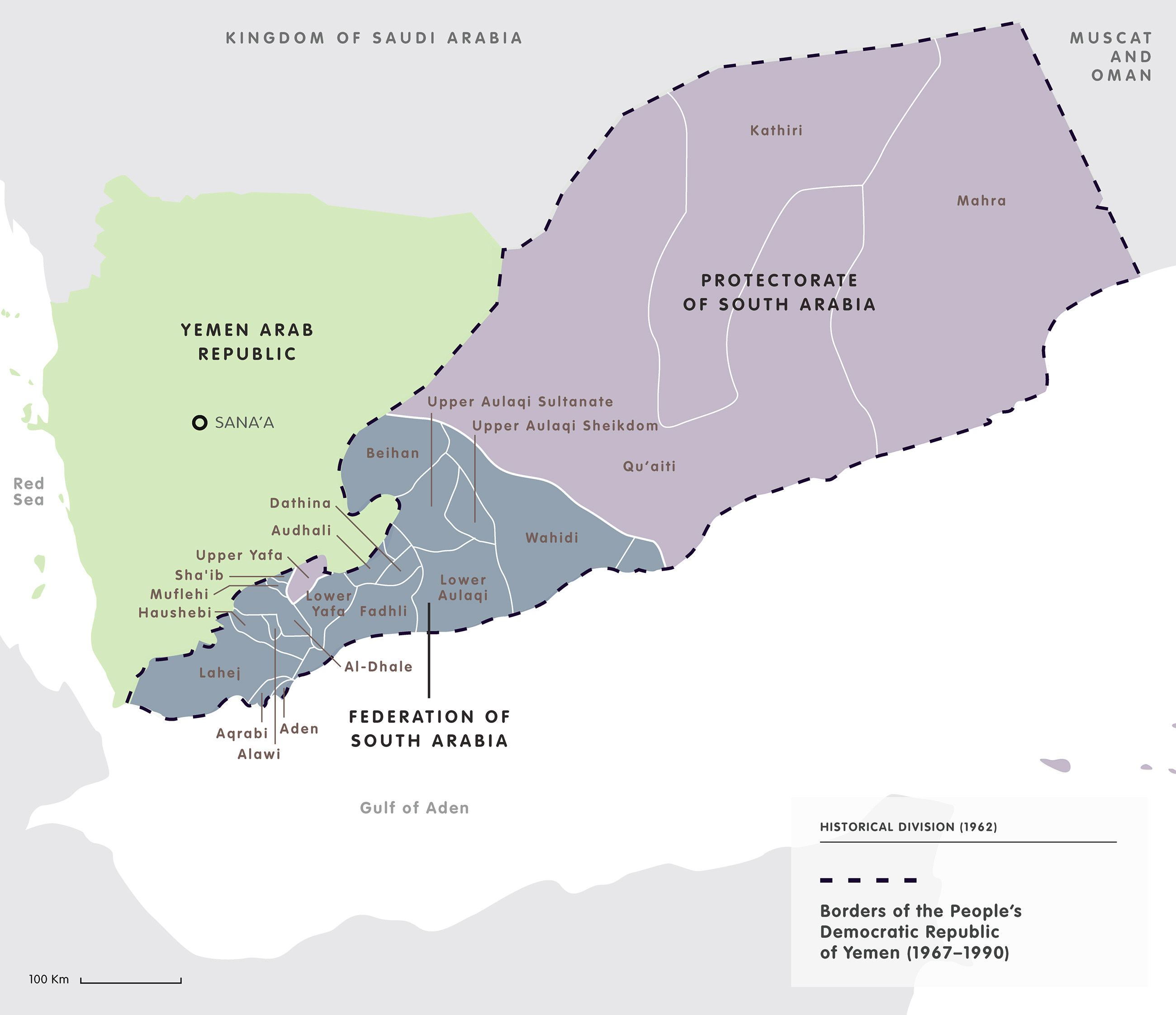

Historical division (1962)

While the concept of Yemen as a territory predates Islam, it has rarely been under the rule of a single government. For much of the past century, the country was split into the northern Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) and the southern People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY), which were unified in 1990. The line separating north and south is the result of a division of spheres of influence by the British and the Ottomans. But the cultural differences between the two regions are real—and accentuated by their divergent histories. The northern regime was preceded by centuries of Zaidi theocratic rule – a branch of Shi’ism found almost exclusively in Yemen – under a series of Zaidi imams, who had held varying degrees of spiritual and temporal authority in the north since the ninth century. By contrast, the south was subject to a century of British influence. The strategic port of Aden was run directly as a colony and British influence was established in its hinterlands and other areas of the south through deals for financial and military aid with the heads of the various sultanates, sheikhdoms and emirates that constituted the Federation of South Arabia and the neighbouring Protectorate of South Arabia, whose component states had more autonomy. The differences between north and south only deepened after the withdrawal of the British in 1967 and the following decades of rule under the PDRY, which was the only Marxist state in the Arab world.

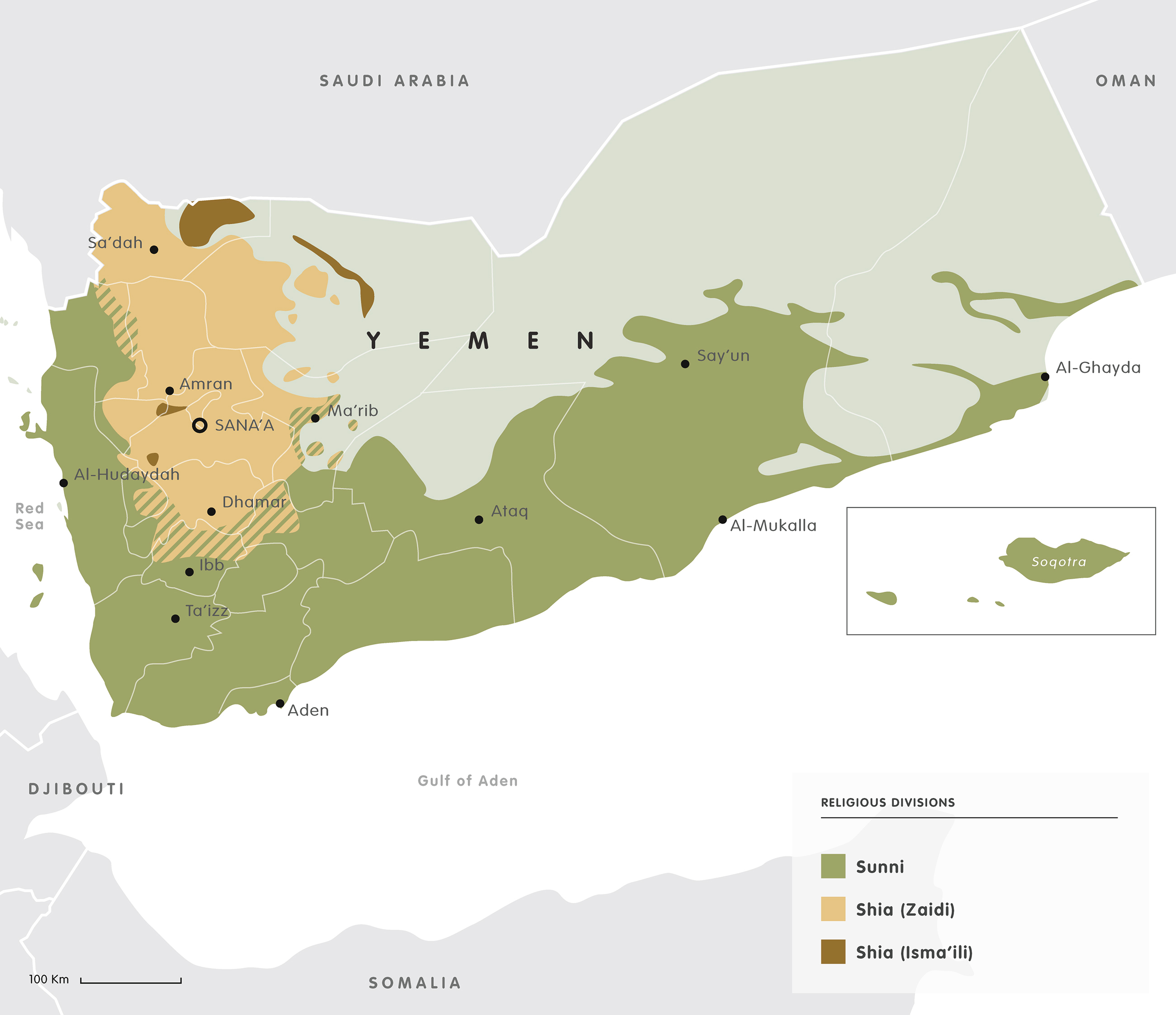

Religious divisions

Yemen’s religious divide largely falls along geographic lines, with followers of Shia Zaidism predominant in the northern highlands, along with a small Isma’illi minority, and Sunnis forming the majority elsewhere. Historically, sectarianism has been minimal: intermarriage between Sunnis, Shafeis (who have traditionally been overwhelmingly theologically moderate), and Zaidis is considered routine and, until recently, Yemenis of different sects prayed at the same mosques without a second thought. But the rise of political Islam—in terms of both Sunni streams, like the Islah party, which incorporates the bulk of the Yemeni Muslim Brotherhood, and Zaidi ones, like the Houthis—has raised tensions, as has the spread of Sunni ideologies in traditionally Zaidi areas, which was one of the key contributing factors to the emergence of the Houthi movement.

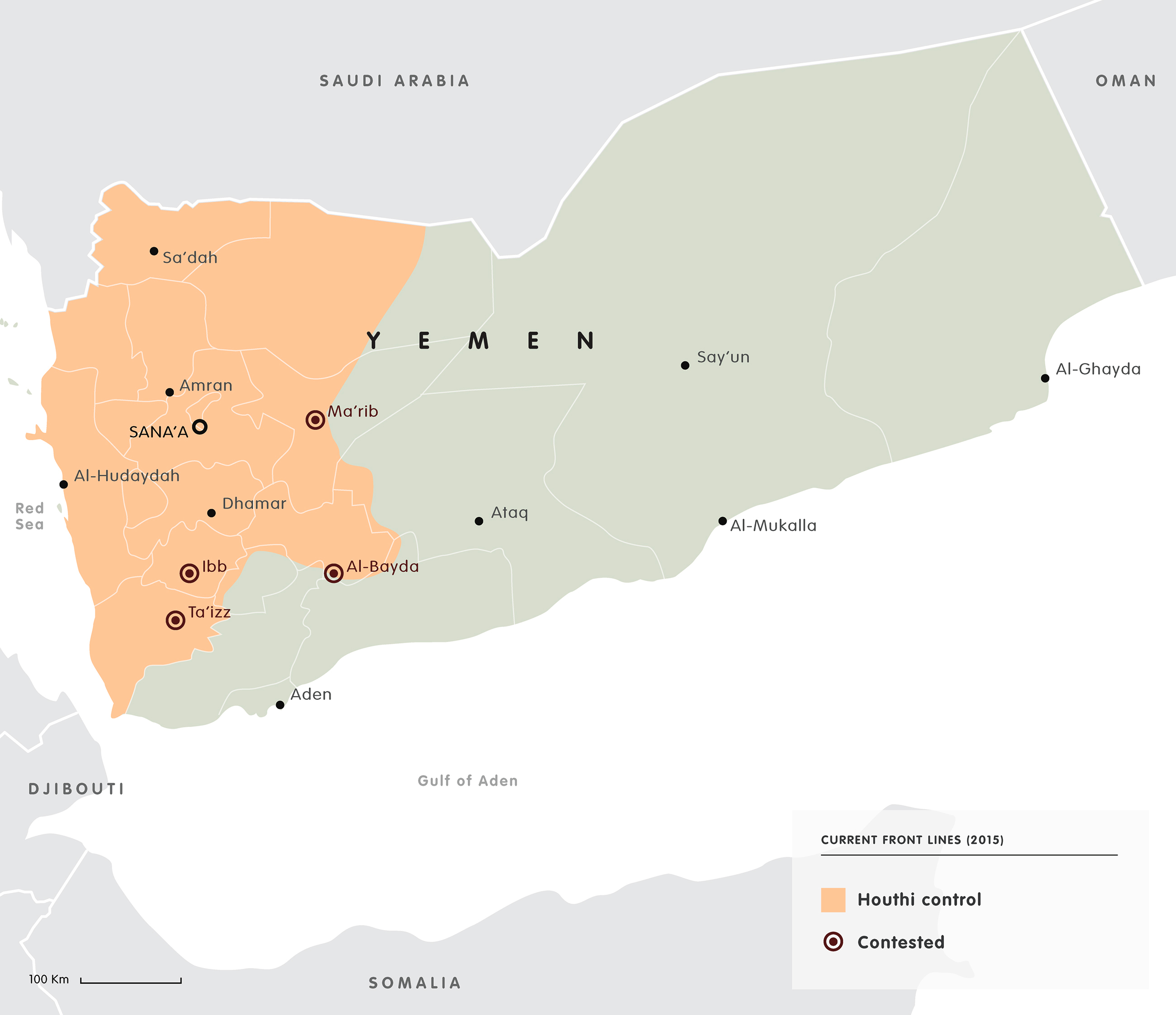

Current front lines

The Houthi rebels continue to fight fiercely against their adversaries, a mix of Saudi and Emirati-backed troops, pro-government military figures, Islamist militants and tribal fighters. But nearly six months after the flight into exile of President Hadi–and the start of a Saudi-led military operation aimed at pushing back against the rebels who toppled him–the state of play in Yemen remains fluid. In some sense, the Houthi rebels have been in retreat, forced out of the bulk of Yemen’s formerly independent south. But the Houthis’ ranks have failed to collapse and, despite continued pressure by resistance fighters, they have maintained a hold in key central provinces. While President Hadi and other officials have trickled back into Aden–and pro-Hadi military forces and scores of allied Gulf soldiers have re-entered Marib—the capital and its surroundings remain in the hands of the Houthis and their allies.

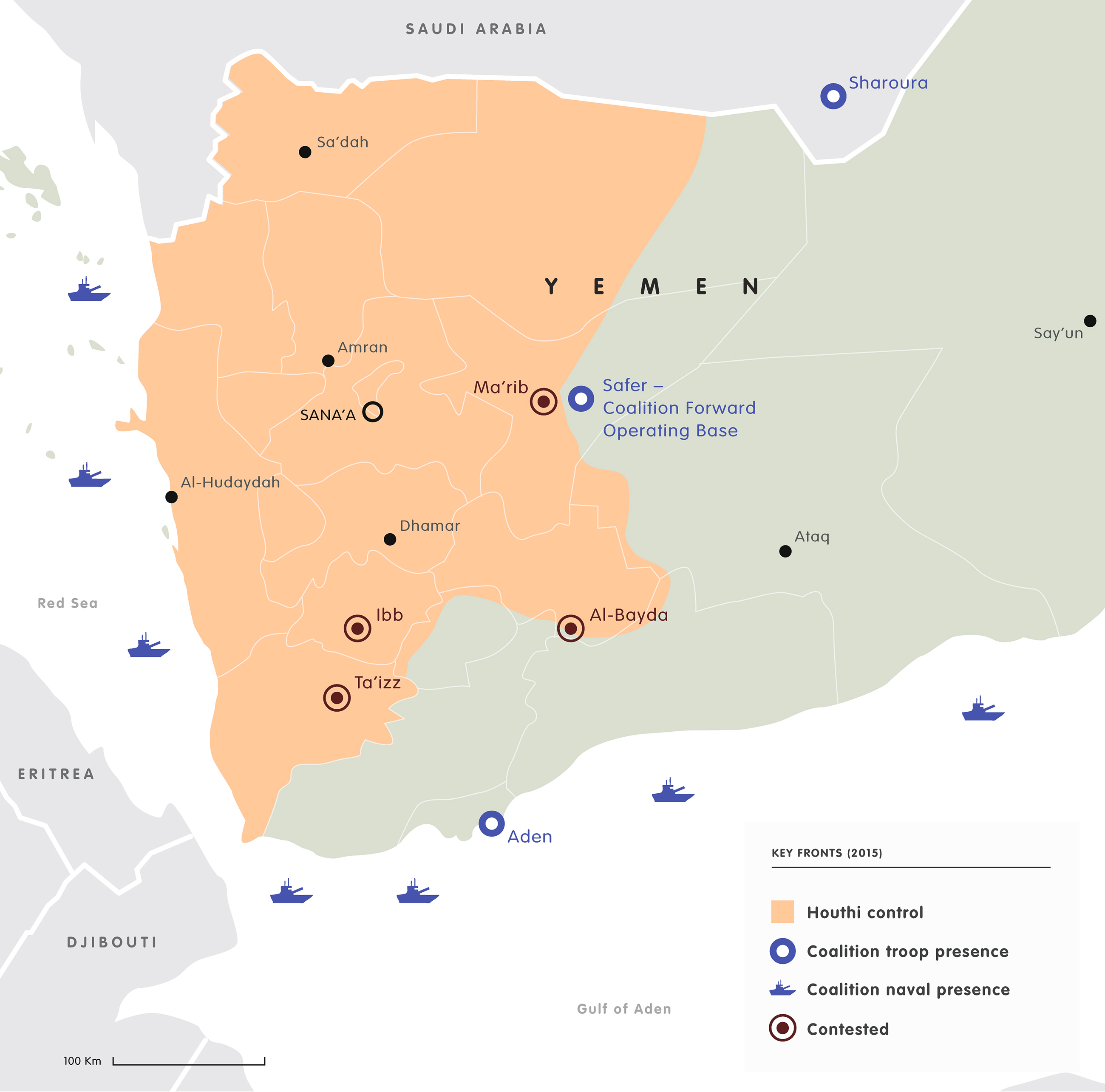

Key fronts

While the Houthis and their allies in the Yemeni military have largely been forced out of Yemen’s formerly independent south, they continue to hold their ground elsewhere despite continuing airstrikes, a naval blockade by the coalition, and the efforts of anti-Houthi militias on the ground. Despite gains by local anti-Houthi resistance fighters in Ta’izz, Yemen’s third largest city, the battle continues, fuelling a deepening humanitarian crisis. The province of Ibb, its neighbour to the north, has witnessed a continuing back-and-forth as Houthis clash with their opponents, as has the strategic province of Al Bayda, where the Houthis and their allies have recently managed to reverse some losses.

The Saudi-led coalition has set its sights on the desert province of Marib. Yemeni fighters trained in a Saudi military post in Sharoura, just north of the border, have descended into the province, joining increasing numbers of coalition troops, tribal fighters and military hardware in a forward operating base in the centre of the province. But while coalition forecasts of the coming expulsion of the Houthis from Marib may very well be accurate, claims that Sanaa will fall shortly after are less likely to come to fruition–something underlined by the miles of rugged mountains separating the province from the capital.

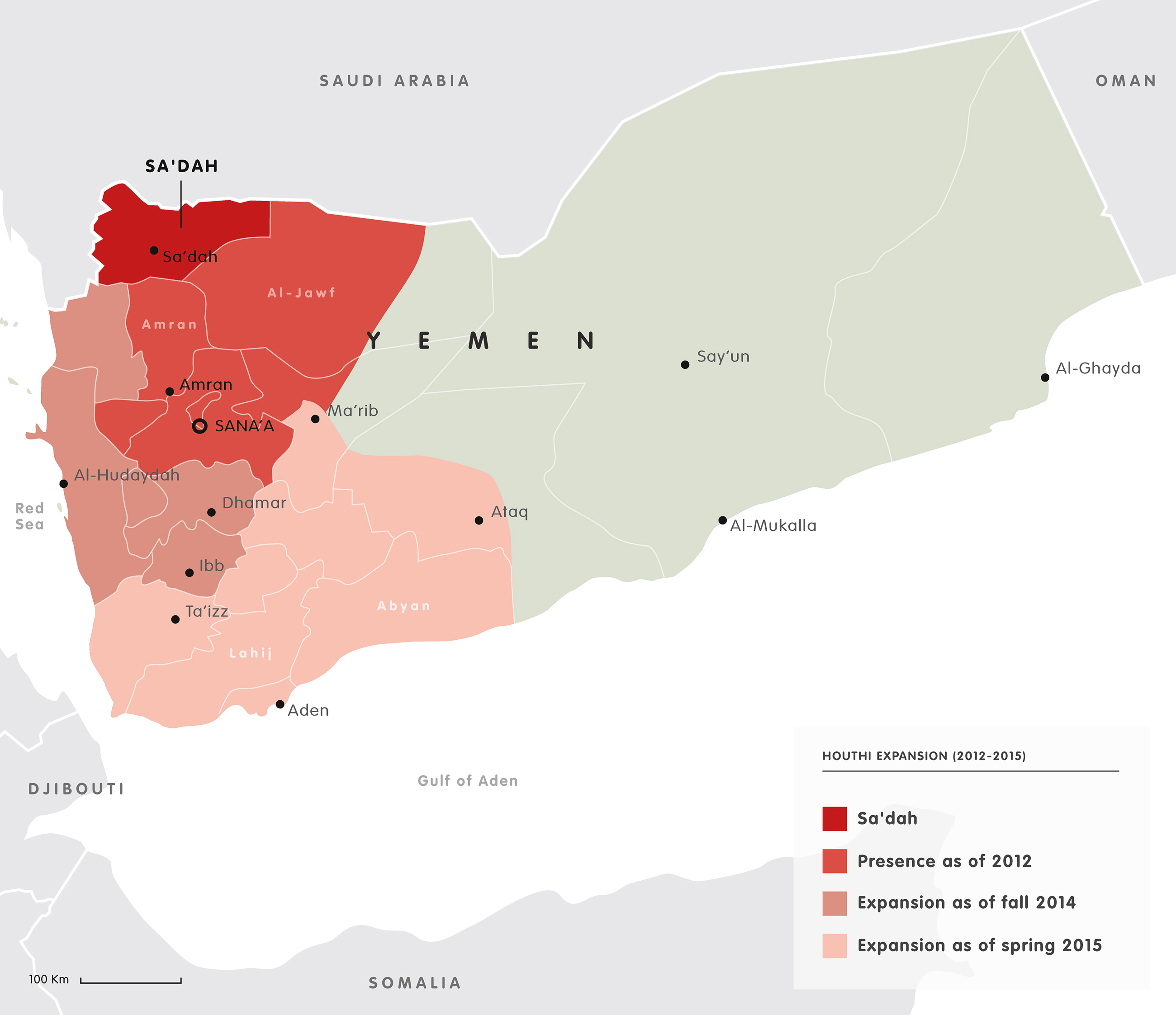

Houthi expansion (2012-2015)

The Houthis emerged out of Yemen’s mountainous far north in 2004 from “Believing Youth,” a revivalist movement founded to shore up Zaidism, which local religious and social leaders feared was under threat from the encroachment of Sunni ideologies. While initial fighting was largely limited to the Houthi family’s strongholds in mountainous areas in Sa’da, it soon expanded to other parts of the province, spreading to northern areas of Amran and western areas of Al Jawf in subsequent rounds of conflict. The Houthis managed to gain control of Saada province amid Yemen’s 2011 uprising, gradually inching closer to the national capital, Sanaa, before taking control on 21 September 2014. In the following weeks they expanded their control south to Ibb province and west to Al Hudaydah.

The rebels forced President Hadi to resign in January 2015 and seized control of areas as far south as Abyan, Aden, and Lahj, before being pushed back in July and August 2015 by resistance fighters supported by a Saudi-led anti-Houthi coalition.

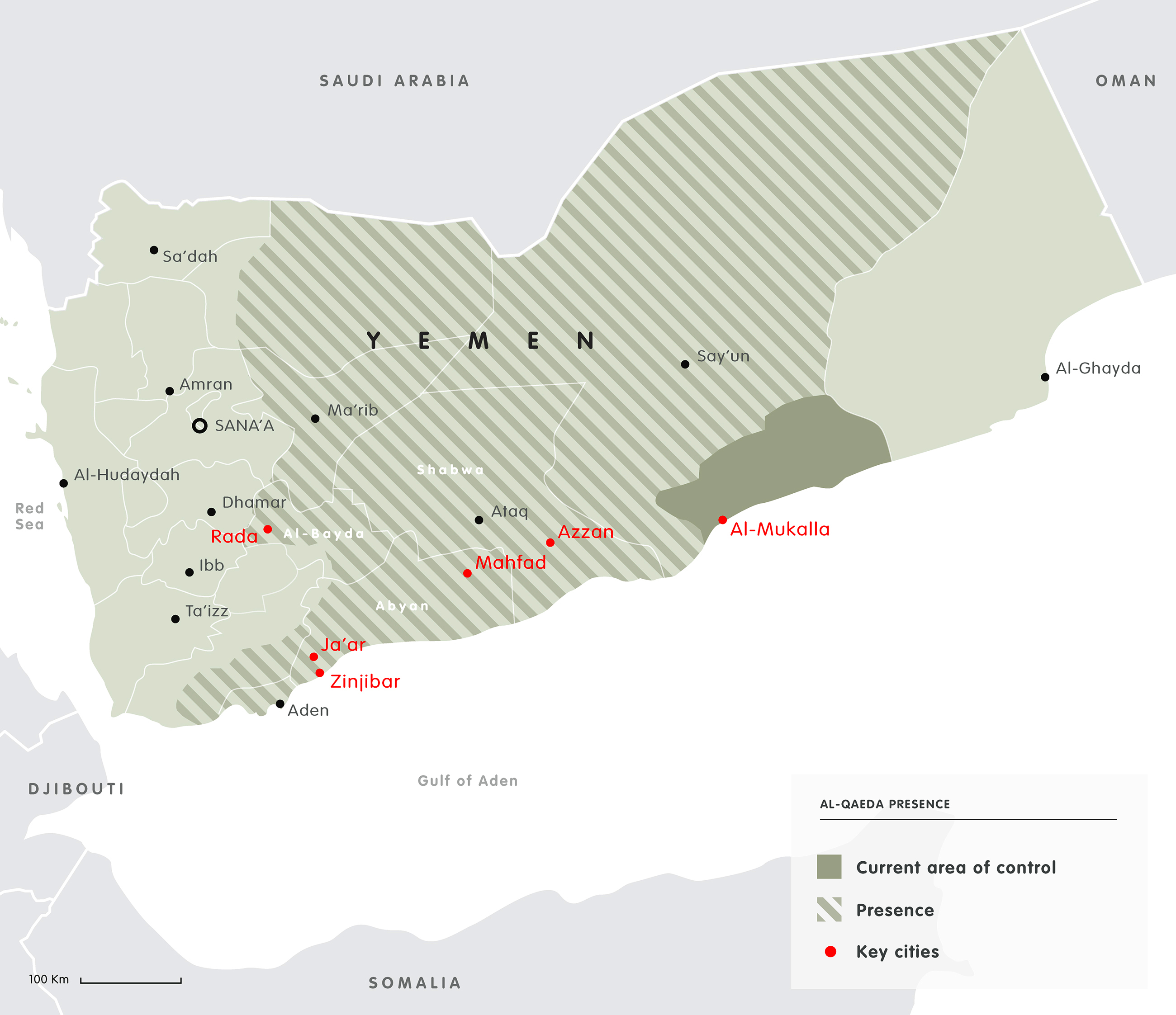

Al-Qaeda presence

Jihadist fighters returning to Yemen after fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq have for many years continued the fight in the country’s unevenly-governed deserts and mountains. A Yemen-based group, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), is considered one of al-Qaeda’s most effective franchises; the United States has waged an ongoing drone campaign against AQAP in response to the group’s attempts to strike US targets in the US itself and abroad. In the wake of Yemen’s 2011 uprising, al-Qaeda-affiliated militants—fighting under the banner of Ansar Al Sharia, or The Supporters of Islamic Law—seized control of swathes of the southern Abyan province, establishing Islamic emirates in the towns of Ja’ar and Zinjibar and eventually seizing the town of Rada, in Al Bayda, in early 2012. While they were pushed out of Abyan in a US-backed Yemeni

military offensive the following spring, they re-established themselves in the mountains of Mahfad and Azzan, before being pushed out again in 2014. In the tumult unleashed by the Houthi takeover of Sanaa and subsequent Saudi-led coalition airstrikes, al-Qaeda-linked fighters have gained renewed operating space, taking control of Al Mukalla, Yemen’s fifth largest port, backed by allied local forces. Simultaneously, AQAP defectors loyal to the Islamic State militant group have increased their profile, operating training camps in some areas of the south and taking credit for attacks on Houthi-linked targets.

The Southern Movement

Yemen’s south, which had been a separate country until 1990, attempted to secede in 1994, but was prevented as pro-unity forces consolidated their control over the country. Under the surface, however, tensions began to build. The 2007 emergence of the Southern Movement, an umbrella of factions and figures calling for a return to autonomy in the south, provided a forum for grievances; in its initial stages, it was most active in the mountainous areas of Yafa, Al Dhale and Radfan. As the government in Sanaa largely ignored its demands, the Southern Movement built up further support—even as it remained divided in terms of organisation, strategy, leadership, and ultimate aims. Benefitting from Gulf support to anti-Houthi factions, Southern Movement-allied fighters are now the dominant force in much of the south. But the international community remains committed to Yemen’s continued unity and, despite significant popular support for a split, secessionists have largely been playing it carefully—for now. And while the Saudi-led coalition may have empowered many secessionist leaders, both Saudi and Emirati leaders have repeatedly asserted their commitment to a united Yemen.

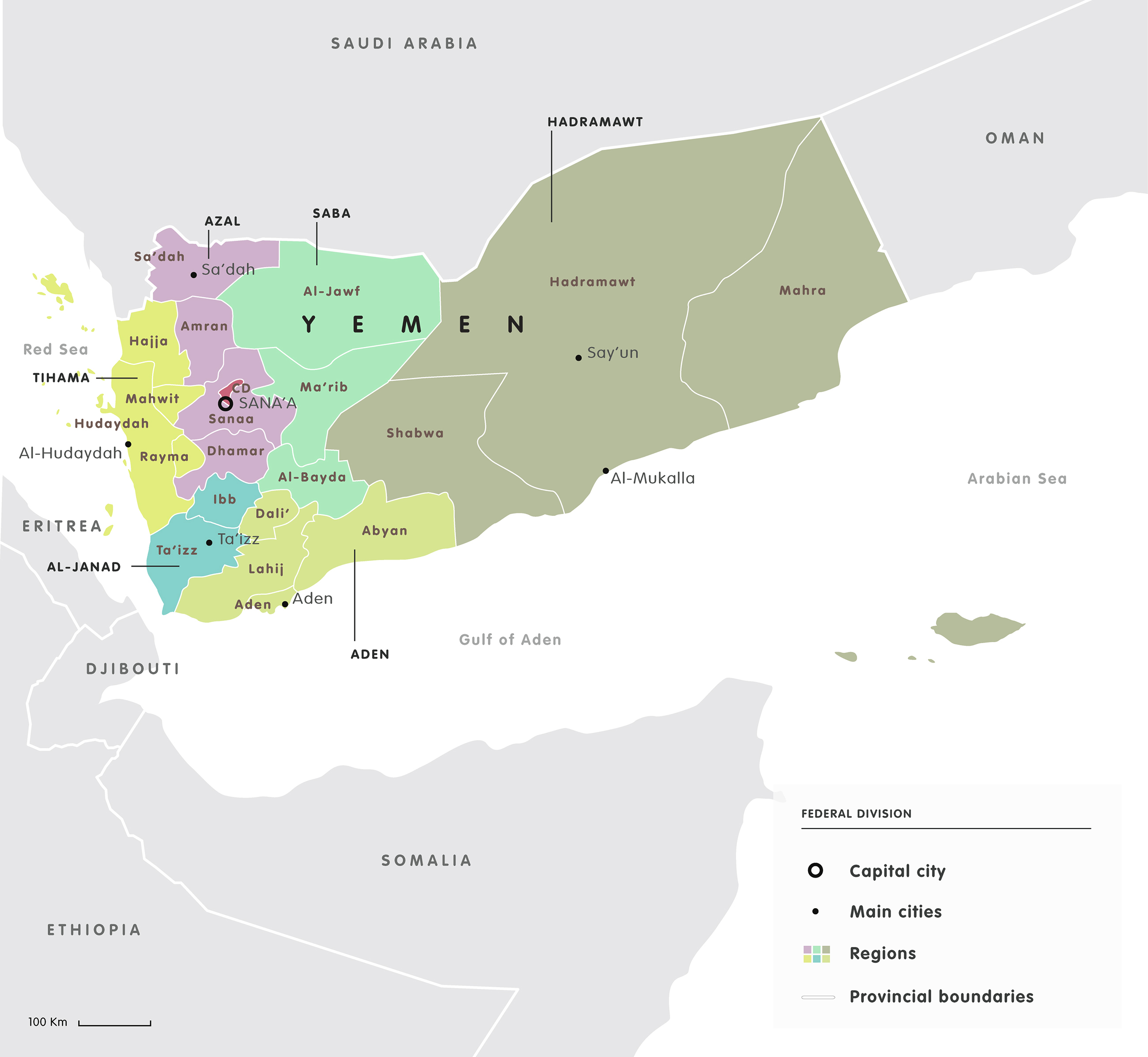

Federal division

Proposals for a federal system of governance in Yemen have long been in circulation, both in the aftermath of unification and following Yemen’s 1994 civil war. They picked up considerable steam following the 2007 emergence of the Southern Movement, as many southern leaders called for greater autonomy. A federal division of Yemen was finally agreed in February 2014 by a subcommittee in Yemen’s National Dialogue Conference, an ambitious summit that aimed to pave the way for the drafting of a new constitution. The proposal was accepted by the bulk of the country’s political players, with the exception of the Houthis, who expressed reservations about the final divisions, and some factions of the Southern Movement, who opposed the split of the former PDRY into two federal regions. While the precise nature of devolution of powers remains unclear, the federal division splits Yemen into six regions: Hadramawt, encompassing the Hadramawt, Mahra and Shabwa provinces; Aden, encompassing Abyan, Lahj, Al-Dhale and Aden, Al-Janad, encompassing Ibb and Ta’iiz, Saba, encompassing Marib, Al-Jawf and Al-Bayda, Tihama, encompassing Al-Hudayda, Rayma,

Mahwit and Hajja, and Azal, encompassing Dhamar, Sanaa, Amran and Sa’da. In recent statements, Hadi has continued to cast the federal division as sacrosanct—even if a diverse array of analysts, diplomats and politicians continue to advocate for amendments to be made.

Author: Adam Baron; Maps: Marco Ugolini; Web: Lorenzo Marini; Audio: Katharina Botel-Azzinnaro; Project coordinator: Matteo Mencarelli.

Audio credits: Freesound.org/juskiddink – bass drone; Freesound.org/boog33 – deep bass noise; Freesound.org/CGEffex – heavy machine gun

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.