The discreet charm of hypocrisy: An EU-Turkey Power Audit

Summary

- Among European elites, there is still substantial support for a strategic partnership with Turkey – albeit not for advancing the beleaguered accession process. Europe needs to find new channels through which to engage with Ankara.

- Since Turkey shows no immediate desire to restore the rule of law or a reform process, for the time being EU member states can, at best, strive to engage in transactional bilateral relations with Turkey, as an effective partnership with the country is critical to their interests.

- Ankara and the Council of Europe should work together to address issues such as human rights, the rule of law, and political freedoms in Turkey – outside of the EU accession process but in line with the Copenhagen Criteria.

- The EU should update its customs union with Turkey, not least because trade between the two sidess has generally benefited pro-European Turkish businesses and civil society groups.

- The EU and Turkey should establish a framework for addressing disputes that involve the Turkish diaspora in Europe, while coordinating their policies on conflicts in the Middle East.

Introduction

Addressing a press conference in Paris in January 2018, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan complained that years of waiting for membership of the European Union was “seriously exhausting us and seriously exhausting our nation. Maybe this [situation] will force us to take a decision.” French President Emmanuel Macron replied, “for relations with the European Union, it is clear that recent developments and choices allow no progress.” He continued, “We must get out of a hypocrisy that consists in thinking that a natural progression towards opening new chapters is possible. It’s not true.”

Journalists and officials have quietly used the word “hypocrisy” to describe Turkey’s planned accession to the EU since 2010, when the process came to a halt with the sides having opened only 16 chapters of negotiations. But it is rare for a European leader to use such language in an official setting. When asked about Macron’s comments on his way back from Paris, Erdoğan said, “I didn’t want to understand what he said exactly. I focused on getting them to understand us. I thought he should understand what I am saying. I focused on explaining that as good [sic] as possible.” Taken together, Macron’s remarks and Erdoğan’s reaction are a microcosm of Turkey’s relationship with the EU.

Today, 12 years after the start of the accession negotiations, 30 years after Turkey’s application for accession to the EU, and more than half a century after an association agreement with the European Economic Community, this relationship is in a parlous state. At best, it is an exercise in hypocrisy that works for both sides. At worst, it is a dialogue of the deaf that will lead to a slow divorce.

Of course, things did not have to go this way. Turkey’s membership bid was once hailed as a major strategic opportunity for both sides. Now, many chapters of the accession negotiations are blocked and several European leaders have announced that there is little prospect of EU enlargement. The Turkey–EU relationship suffers from periodic political crises involving, and diplomatic spats between, Ankara and various European governments. Initial enthusiasm has given way to rancour on both sides.

So, what can be preserved and achieved in the relationship? Should the sides keep the moribund accession process on the books or start discussing a new framework? How will Turkey and the EU manage overwhelmingly negative public perceptions of each other while elites struggle to prolong the status quo? In short, is there value in hypocrisy when it comes to Turkey’s relations with Europe?

A peculiar status quo

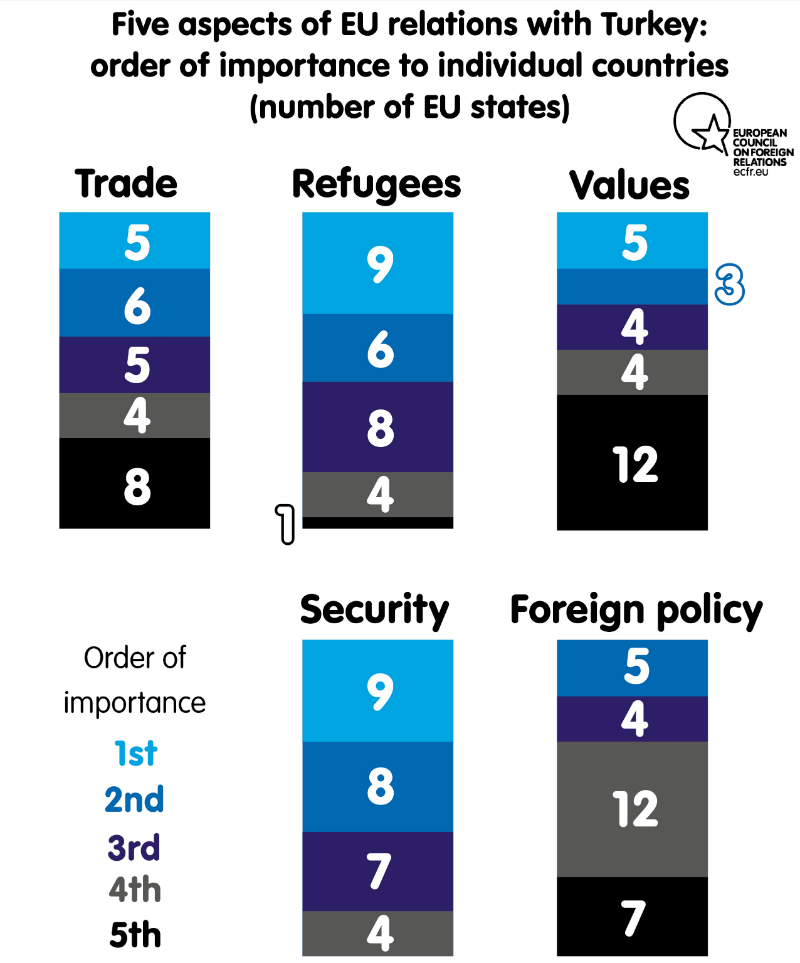

The European Council on Foreign Relations’ new survey of on perceptions of Turkey within 28 EU member states reveals the extent to which hypocrisy has become a fundamental and almost functional aspect of the EU-Turkey relationship. Despite the problems facing the accession process and strong public opposition to Turkey’s membership across Europe, nearly all European governments believe – for widely varying reasons – that they should maintain, but not advance, the accession process in its current state.

All member states recognise that Turkey’s public image in Europe has deteriorated in recent years, and that EU citizens generally oppose Turkish accession. But, at the same time, EU countries see Turkey as a major strategic ally, an important (or potentially important) trading partner, and a power that should be kept close.

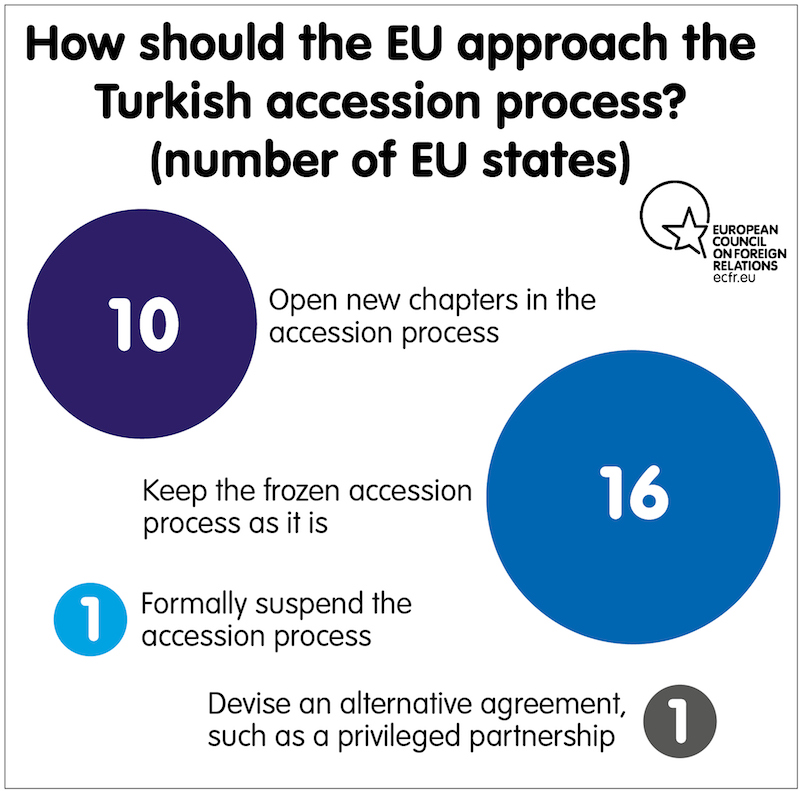

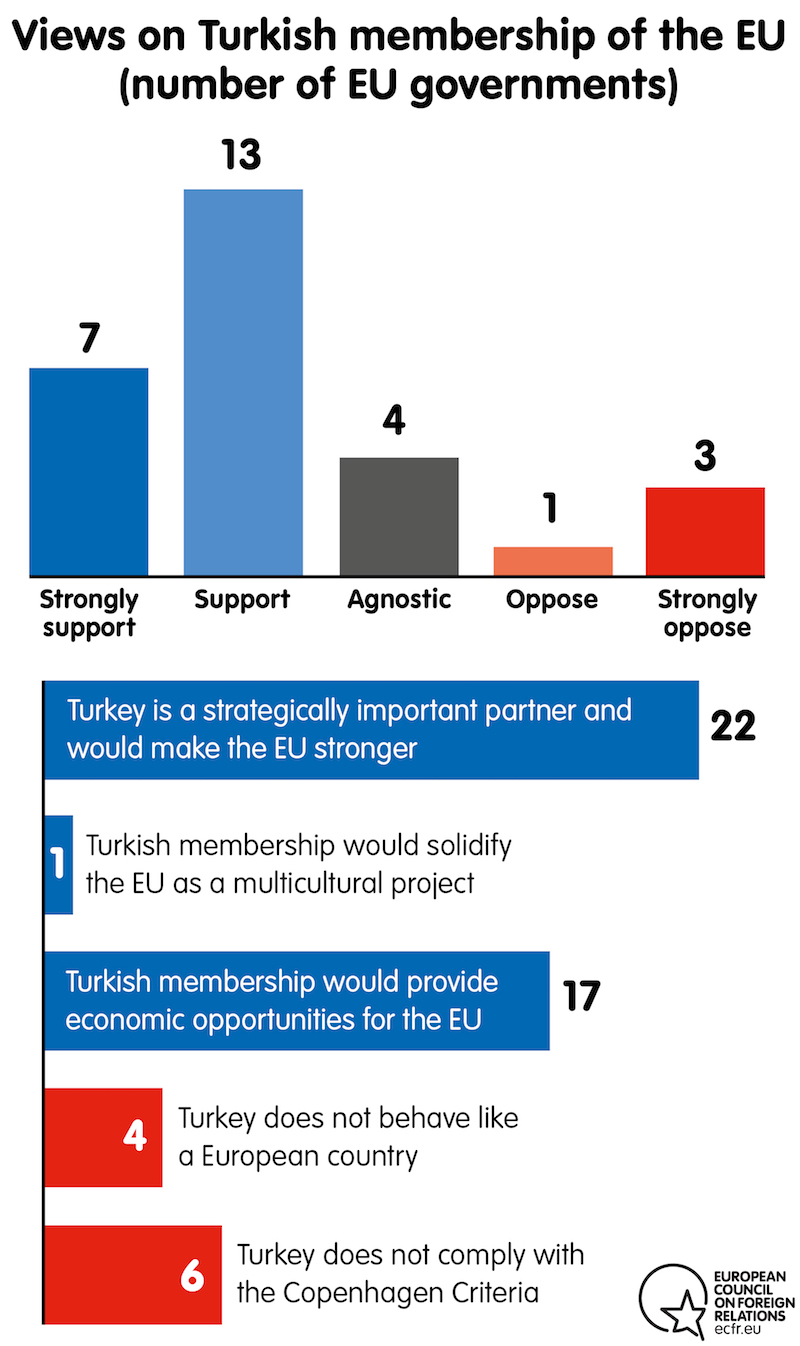

Although EU member states and European decision-makers have little desire to revive the accession process, many view Turkey as a crucial partner. In the new ECFR survey, 46 percent of EU decision-makers who responded to the questionnaire stated that their government “supports Turkey becoming a member of the EU,” while another 25 percent said that there is “strong support” for Turkish membership within their governments. Only one EU member state officially wants to suspend Turkey’s accession bid. Sixteen out of the 28 “want to keep frozen accession process as it is.”

Paradoxically, dysfunction and hypocrisy help maintain the accession process. This is because countries that might quietly have questions about full Turkish membership of the EU, such as Poland and Cyprus, can claim to support the process safe in the knowledge that it will remain stalled. Meanwhile, Turkey can use the power of hypocrisy to build a model for cooperation with the EU, preserving the status quo in the accession process with the support of around 70 percent of EU decision-makers.

This is a considerable majority. Although Turkey has long focused on its disputes with the European Commission and EU politicians, the most dedicated pro-Turkey advocates remain EU elites – officials, diplomats, and decision-makers. Meanwhile, EU citizens are far less tolerant of Turkey’s current direction and its divergence from European norms and values.

In wanting to keep Turkey close, EU member states have varying reasons but are primarily motivated by either fear or greed. Those that strongly advocate maintaining the accession process do so out of either a sense of vulnerability, a strategic need, or the belief that Turkey is economically important to Europe. For example, Greece, Cyprus, and Bulgaria believe that Turkey’s engagement with the accession process reduces the threat it poses to their national security, and that it provides them with some leverage over Turkey. Despite the strong anti-Muslim sentiment in parts of Polish society, Poland fears a strong Germany and would like to have another big player on the scene – hence its support for the accession process continuing as it is. Britain sees the possibility of a loose union in general – and favours enlarging the EU over deepening relations between its member states. Rome, Madrid, and Paris are deeply interested in a realpolitik approach based on economic relations with Turkey given the country’s potential for growth. Small EU countries such as Malta, Estonia, and Slovenia support Turkey’s bid either because they want to have good relations with Ankara, have growing ties with the Turkish economy, or welcome another state that would balance the influence of the EU’s major players. Some member states’ attachment to the dysfunctional status quo comes from fear of being engulfed in a large, strong Europe. Some believe that there is a strategic case for Turkey joining the EU in the future – but not necessarily now.

The need to downplay accession talks

Most European countries would like Turkey to remain in the limbo between being an insider and an outsider. It may well be that, despite the hypocrisy and dysfunction, the status quo is Ankara’s most significant asset in preserving its relationship with Europe during a turbulent era. Turkey has become increasingly inward-looking and ever less democratic in the past few years, especially since the failed coup attempt in July 2016. Despite this, EU-Turkey relations have remained intact. The European Commission and the European Council have dismissed calls from the European Parliament to suspend the accession talks. It is important to preserve Turkey’s European membership bid for future generations.

These trends suggest that if Turkey reverses its drift towards authoritarianism, it may have a chance to revive its accession bid. Yet the status quo has created a kind of institutionalised hypocrisy, allows for no genuine movement towards integration, and marginalises the need for Turkey to adopt the EU’s values as part of its accession bid. As a consequence, the accession process has lost all credibility. Turkish bureaucrats who work on the EU accession process often emphasise the fact that this state of limbo is not what Ankara wants but this is what it gets. The only movement in the accession process in recent years involved a brief opening in EU-Turkey relations with the migration deal the sides reached in December 2016. At the moment, the Turkish government shows no apparent desire to return to a governance system centred on the rule of law and displays little regard for the Copenhagen Criteria. And the EU shows no indication of either reviving the accession process or pushing Turkey out.

Here are more examples of hypocrisy. Despite the widespread belief that Turkey is important to the EU, only 36 percent of EU decision-makers would like to open new chapters in the accession negotiations, while 57 percent of them would prefer to keep the process “frozen” in its current state. There is a general acceptance that Turkey’s public image has deteriorated overall across member states in the last few years, with some countries complaining about high-profile human rights cases involving their citizens – as seen with the Turkish authorities’ arrest of Die Welt reporter Deniz Yücel on terrorism charges, which caused an outcry in Germany. Nonetheless, 24 member states believe that the EU “should not be any more outspoken on human rights and democracy” – only four member states make a case for greater emphasis on human rights in Turkish-EU ties.

Here are more examples of hypocrisy. Despite the widespread belief that Turkey is important to the EU, only 36 percent of EU decision-makers would like to open new chapters in the accession negotiations, while 57 percent of them would prefer to keep the process “frozen” in its current state. There is a general acceptance that Turkey’s public image has deteriorated overall across member states in the last few years, with some countries complaining about high-profile human rights cases involving their citizens – as seen with the Turkish authorities’ arrest of Die Welt reporter Deniz Yücel on terrorism charges, which caused an outcry in Germany. Nonetheless, 24 member states believe that the EU “should not be any more outspoken on human rights and democracy” – only four member states make a case for greater emphasis on human rights in Turkish-EU ties.

European elites like the idea of Turkey, as opposed to the reality; and they like the notion of a strategic alliance with the country, but not necessarily as a member of the club. Officials in 22 member states assert that their governments believe Turkey to be “a strategically important partner and would make the EU stronger”.

European elites like the idea of Turkey, as opposed to the reality; and they like the notion of a strategic alliance with the country, but not necessarily as a member of the club. Officials in 22 member states assert that their governments believe Turkey to be “a strategically important partner and would make the EU stronger”.

Only one member state wants to formally end the accession process and only one government officially holds the view that the EU-Turkey relationship should be recast as a “privileged partnership”. Yet, in reality, the interrupted and dysfunctional process closely resembles the privileged partnership Turks have been rejecting all along due to its connotations of second-tier status.

A new language and a new framework are needed to reconcile these apparent contradictions. Where they aim to develop the Turkey-EU relationship while suspending (but not ending) the accession process, Turks and Europeans need to speak not of “Turkish membership of the EU” but rather of “Turkey and Europe” as two historic, neighbouring powers. When the focus moves away from the accession process, it becomes relatively easy for EU member states and citizens to recognise that an effective partnership with Turkey is critical to their interests. “Turkey-Europe” highlights a strategic need; “Turkey-EU” is all about Turkey’s shortcomings. A new conceptual framing needs to mention Turkey’s historical and strategic ties to the continent and de-emphasise its shortcomings in the accession process. In the meantime, bilateral ties are the likely model for Turkey’s future engagement with member states.

Elites versus the public

Another important reminder from ECFR’s new Power Audit is that the relationship with Turkey is an elite game. Turkish leaders in Ankara should understand that the only real advocates for the relationship are those that represent the establishment in Europe – that is, the collective of bureaucrats and politicians Turkish officials often fume at.

As this study confirms, the support of European elites sustains the EU’s relationship with Turkey. Leaders in Ankara should recognise this fact even as they launch verbal attacks on EU bureaucrats and politicians.

Despite the apparent downturn in relations, the arguments in support of Turkey’s membership bid within the establishment do not seem to have changed much in the past decade. According to ECFR’s new survey, 79 percent of EU respondents (most of them officials) believe that their country sees Turkey as a strategically important partner that can make the EU stronger. That figure accounts for 22 of 28 member states. Another 61 percent believe that Turkey’s accession to the EU would provide their country with new economic opportunities. Coming at the lowest point in EU-Turkey relations in recent times, these findings should hearten Ankara.

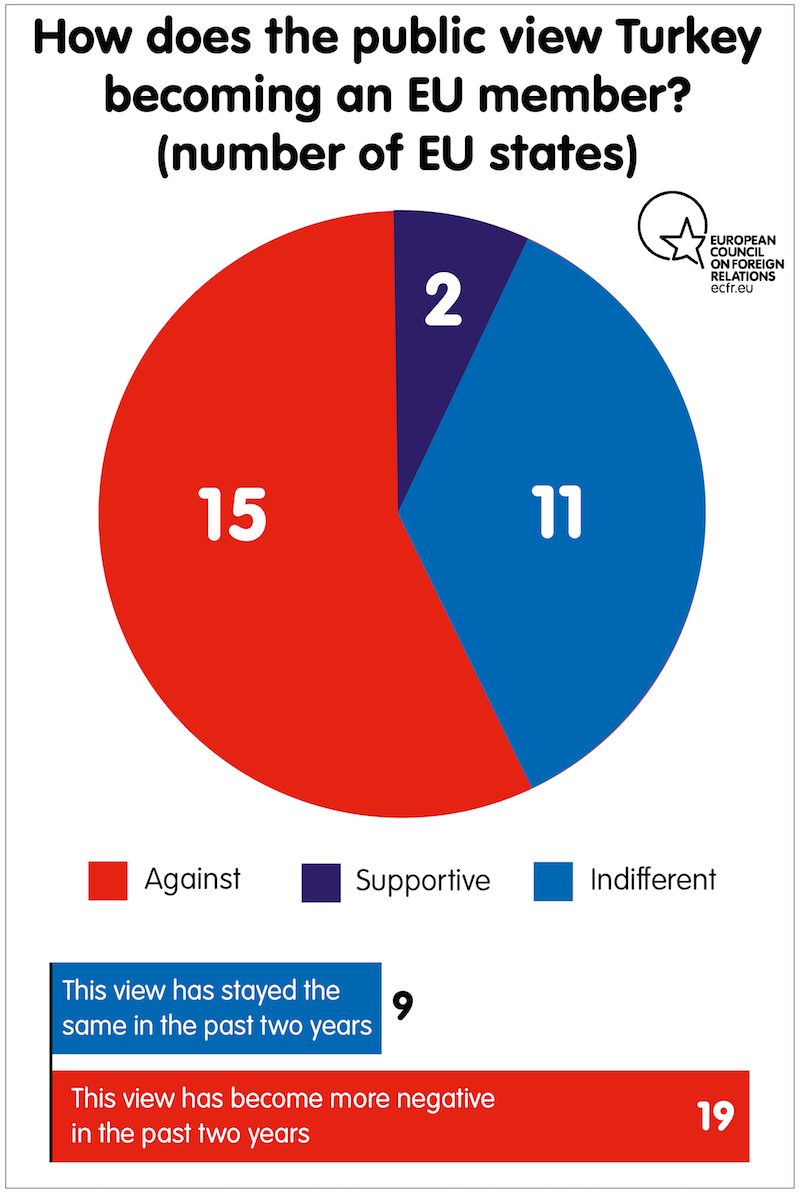

Of course, public opinion is a different matter. Public sentiment about Turkey sharply diverges from the views of the establishment. According to one survey taken in 2017, 84 percent of Germans oppose Turkey’s membership of the EU.[1] In ECFR’s new survey, only 7 percent of respondents said that the public in their countries supports Turkey’s accession bid, 39 percent viewed the public as indifferent to the issue, and the remaining majority admitted that the public opposed Turkish membership of the EU. Almost 70 percent of respondents noted that Turkey’s public image has deteriorated in the past two years, producing greater popular opposition to Turkish accession.

Of course, public opinion is a different matter. Public sentiment about Turkey sharply diverges from the views of the establishment. According to one survey taken in 2017, 84 percent of Germans oppose Turkey’s membership of the EU.[1] In ECFR’s new survey, only 7 percent of respondents said that the public in their countries supports Turkey’s accession bid, 39 percent viewed the public as indifferent to the issue, and the remaining majority admitted that the public opposed Turkish membership of the EU. Almost 70 percent of respondents noted that Turkey’s public image has deteriorated in the past two years, producing greater popular opposition to Turkish accession.

These findings indicate that the EU’s debate on Turkey will continue to be a matter of elites versus “the people” – or the establishment versus public opinion. European elites want a close relationship with Ankara – and in many member states focus on Turkey’s long-term strategic and economic value. But the public remains unconvinced. It is no coincidence that spikes in Turkish-European tension almost always coincide with elections in Europe or Turkey. Turkey’s membership bid was a major topic during the Brexit referendum, as well as in the recent Dutch, Austrian, and German elections. European leaders show relatively little willingness to accommodate Ankara during an election, the time at which they are most under pressure to cater to public opinion.

The importance of bilateral relations

In navigating this difficult territory, particularly the widening gap between elite views and public opinion, Turkish and EU leaders require an approach more nuanced than simple repetitions of support for the status quo. The results of ECFR’s new survey underline the need to develop a new language to describe the importance of EU-Turkey relations outside the scope of the accession process. Both sides need to start framing the debate as “Turkey and Europe” – as opposed to “Turkey and the EU” – and to avoid language that focuses on the fatigued enlargement process.

There is reason to downplay accession on both sides. Discussions on Turkey’s accession to the EU generally emphasise the country’s weak points – its democratic deficit, the Cyprus issue, and its indifference to the rule of law. The Turkish government resents what it regards as the “hierarchical” tone of the accession process, while Europeans feel that Turkey’s progress is too slow. However, when the relationship is more transactional and the discussion is “Turkey and Europe”, as two partners, there is an inherent equality in the discourse that the Turkish government has wanted all along. Instead of framing every advance or setback in the relationship as part of the accession process, the sides can work together as strategic partners and establish the tone the Turkish government has asked for all along.

Such a transactional relationship, with a focus on bilateral ties, is perhaps the only realistic way to maintain EU–Turkey ties for the moment. Moving away from the accession focus would likely reduce tensions with the European Commission and help European leaders accommodate public opinion, while allowing for deeper bilateral engagement with Turkey on business deals, foreign policy, and counter-terrorism. Indeed, by placing a strong emphasis on trade and counter-terrorism, Macron presented such a model during Erdoğan’s visit to Paris in January 2018. (French officials argue that bilateral engagement also allows them to raise individual human rights issues with their Turkish interlocutors – albeit with mixed success.)

When it comes to bilateral ties, most European nations seem happy to engage in some type of a give and take with Ankara, even though their citizens sometimes criticise this exchange. For example, following the Brexit vote, Britain was eager to increase trade with Turkey and came to see Ankara as an essential partner in stabilising Syria and Iraq. Similarly, the French value their partnership with Turkey on counter-terrorism. During Erdoğan’s visit to Paris in January 2018, French companies signed a few billion euros’ worth of investments with leading Turkish firms. It is easier to make a case for bilateralism than for accession. For Bulgaria, economic relations with Turkey are important, as are attempts to keep Ankara out of Moscow’s orbit. For Greece, efforts to maintain the EU-Turkey refugee deal and good relations with Erdoğan are paramount to domestic stability. For Germany, the presence of a large Turkish diaspora creates a human bridge between the two nations that no politician can ignore. For Belgium, counter-terrorism cooperation with Turkey is important in containing returning jihadists. The list of examples is long. When tension around the accession process is set aside, engagement with Turkey appeals to all member states.

This is not to suggest that either side terminate the accession process. But since it is frozen and Ankara shows no real commitment to the Copenhagen Criteria (for the moment), Europe and Turkey should shift their focus to maintaining a functional relationship. Rather than be trapped by the existential question of whether to keep or terminate the accession process, European and Turkish leaders should direct their energy at cooperation in areas of mutual interest – at least for the next few years. In this context, bilateral relations with member states – with an emphasis on foreign policy, counter-terrorism, and economic partnership – should form the new framework for cooperation.

Such a shift may already be happening. After a year of rising tension with the EU, Ankara’s recent efforts to reset relations with France and Germany revolve around a new, bilateral agenda – which is divorced from the accession process.[2] Similarly, when Erdoğan travelled to Paris in January 2018, his first official visit to a western European capital for some time, it was not to advance Turkey’s EU accession bid but to strengthen bilateral economic ties. Equally, although Macron raised various human rights issues during talks with the Turkish leader, his main goal seemed to be maintaining open channels of communication with a powerful regional partner rather than to push Turkey towards accession.

Toxic public feuds

During the last two years, public exchanges between Turkish and European leaders have often descended into vitriol and resentment. Turkey’s April 2017 referendum, as well as the Dutch and German election that year, led to a new low in the public discourse on EU-Turkey relations. Turkey’s strongman has called both German and Dutch officials “Nazi remnants” on separate occasions.[3] In 2016, Britain’s Spectator magazine ran a competition featuring a £1,000 prize for rude poetry about Erdoğan – a prize that went to soon-to-be foreign minister Boris Johnson. Both the opposition and the governing coalition in Germany have questioned whether Turkey under Erdoğan was fit for EU membership in the run-up to the German election. The German authorities have prevented Erdoğan and other Justice and Development Party (AKP) leaders from holding mass election rallies in Germany for the Turkish diaspora there.[4] In turn, Erdoğan made anti-German and anti-European rhetoric the cornerstone of his April 2017 referendum campaign to expand presidential powers. These mutual recriminations have further eroded public support for Turkey’s accession to the EU. As noted above, elections in Turkey and EU countries often coincide with an escalation in hostile rhetoric that, as the latter recognise, causes significant damage to Turkey’s brand in the EU.

This verbal war of attrition must stop. Fortunately, there are signs that it will: in January 2018, Turkish foreign minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu and Sigmar Gabriel, then German foreign minister, agreed to resuscitate dialogue between their countries on the condition that, among other things, the sides observe a ceasefire in public feuding. Of course, Turkey and Europe will continue to criticise each other, but unless this criticism remains within the scope of civilised debate, there will be a further decline in public support for their relationship.

This means Ankara must avoid describing EU leaders as “Nazis” or using other deeply offensive terms. In the run-up to the April 2017 referendum, attacks on the EU became common in Turkish public discourse as the governing AKP worked to secure the nationalist vote. Pro-government media outlets followed AKP officials’ lead in not only directing harsh criticism at “Europe” in general terms but also depicting an alleged pan-European effort to weaken Turkey and its leadership. These tactics both poisoned EU-Turkey relations and alienated the sizeable portion of Turkish society that still harbours pro-European sentiment.

Turkish leaders also need to move away from sweeping statements about a “civilisational clash” with the West – common parlance since the 2016 coup attempt. Although Turkey’s Islamist government has a great interest in playing a leadership role in the Middle East, the country remains part of the Western alliance as a member of NATO and the Council of Europe. Turkish policymakers should also be careful not to equate EU criticism of Turkey’s human rights record with support for “terrorism”. Such blanket accusations erode the Turkish public’s trust in the EU and desire for a shared future with Europe. They also perpetuate a dynamic in which an inward-looking Turkey sees its Western allies as potential enemies eager to “carve up” the country.

Turkey has its own concerns too. As far as AKP officials are concerned, the most significant cause of tension between Turkey and Europe is the latter’s single-minded focus on Erdoğan. Ankara feels compelled to officially react to criticism of Erdoğan more than anything else – even if half of Turkish society applauds such criticism. Importantly, the Turkish government tends not to distinguish between condemnation of Erdoğan from European officials and leaders, and that from civil society and media outlets. There is an increasing tendency within the Turkish bureaucracy and the AKP elite to see media outlets and civil society groups, including human rights organisations, as the secret arm of Western governments. In answering a parliamentary question tabled by the opposition, Hakan Çavuşoğlu, Turkey’s deputy prime minister, said in December 2017, “Media freedom indices are Western-centric and the concept of media freedom is Western-centric, not taking into account the conditions of the country.”[5] Erdoğan has warned that Turks who study in the West and work for Western companies or institutions willingly become spies for the West.[6] In various speeches, he has accused Yücel and Turkish philanthropist Osman Kavala – whose imprisonment has also caused controversy in Europe – of supporting terrorism.

Following the July 2016 coup attempt, the Turkish government’s suspicions about the West became a daily talking point. Ankara is drifting towards a Russian-style divergence from the EU in the debate on values, seeing the promotion of human rights, free speech, and vibrant civil society as an effort to undercut its sovereignty. In the current climate, the EU can do little to bridge this divide with the ruling AKP. Therefore, European leaders should stick to their principles but not personalise disputes with Turkey by focusing on Erdoğan. Doing otherwise would produce a considerable backlash from the government of Turkey. Similarly, European leaders and EU officials should try to explain to their Turkish counterparts, particularly AKP leaders, that Europe’s civil society and media have a life of their own and are unlikely to defer to the government’s preferences.

As hard to accept as it may be, the gap in values is a reality for the moment. But Turks and Europeans can still find common ground, especially in transactional arrangements. For example, with the recent thaw in their relationship, Ankara and Berlin have made a noticeable effort to refrain from public criticism of each other – with the latter avoiding comments on Turkey’s human rights record. In turn, Turkish leaders have curbed comments that are deeply offensive to Germans. The Germany-bashing in Turkey’s pro-government media has ceased completely – the focus having shifted to tensions with the United States, particularly Washington’s support for Syrian Kurds, whom Ankara considers to be terrorists.

Deep-rooted misperceptions

Understanding Turkey – and Erdoğan’s “New Turkey” – requires a little more labour from Europe. It is more conservative, nationalist, and, at times, emotional. Turks and Europeans often talk past one another. For example, Europeans fail to understand the trauma Turkey suffered in the July 2016 coup attempt and the existential fears of the country’s leaders – both for the territorial integrity of Turkey and their own survival. Turks, in turn, misconstrue every EU criticism of Turkey’s human rights record as a sinister effort to weaken the country or its leadership. As supporters of the Turkish president like to remind the public, the coup attempt led to the birth of a “New Turkey”. This incarnation of the country is deeply nationalistic and conservative, as well as strongly suspicious of Western designs on it.

In private, most Turkish officials express the belief that the US was behind the coup attempt and that the EU wanted the plotters to succeed. These officials also resent what they see as American or European support for the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – via Syrian Kurds – and followers of US-based cleric Fethullah Gülen. As one senior Turkish official put it, “Turkey is in a hybrid war with a number of global players”.[7] This statement reflects the siege mentality prevalent in Ankara. From the Turkish government’s perspective, Turkey is fighting a conflict on all fronts – sometimes openly, sometimes in secret – to preserve its territorial integrity.

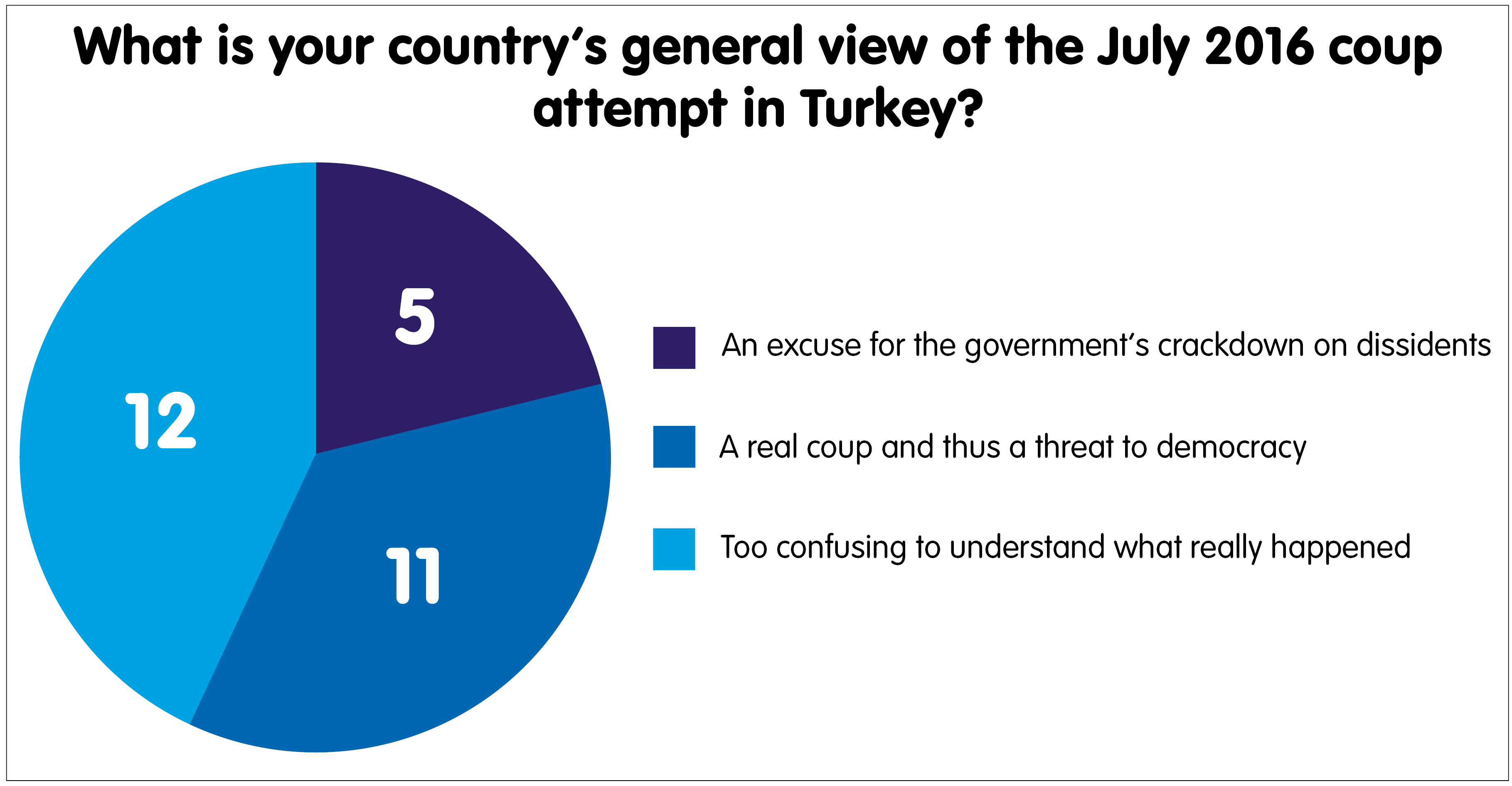

Europe, much like the US, never quite grasped the impact of the coup attempt on Erdoğan’s sense of strategic loneliness – not least his suspicions about the West. Ankara’s disregard for human rights in the post-coup crackdown and its clumsy propaganda efforts complicated the EU’s collective response to the incident. Along the way, they failed to detect the deep sense of insecurity about the future in Ankara and wider Turkish society. While Turkey’s post-coup crackdown undoubtedly introduced draconian measures and violated the rule of law, the coup attempt itself was a real threat to its stability and democracy.

ECFR’s new survey addressed this dichotomy using a symbolic question about the coup attempt, which reveals the extent to which Turks could not explain, and Europeans could not understand, what happened on 15 July 2016. Only 39 percent of EU respondents agreed that the events of 15 July constituted “a real coup and a threat to democracy”. Forty-three percent of European elites, including diplomats and decision-makers, believe the coup is “too confusing to understand what really happened”. Another 18 percent subscribed to the view that the coup attempt was “an excuse for the government’s crackdown on dissidents”.

No wonder, then, that when Ankara sought the EU’s support on the grounds of its national security concerns, it received mostly criticism of its human rights record. Many members of the EU elite do not grasp the fact that Turkish society perceives the coup attempt as an existential threat. Such misunderstanding almost certainly runs even deeper among EU citizens generally.

This is something more than a case of miscommunication. The Turkish government’s concerns stem from the perception that the West is behind the coup and, more immediately, that the rising influence of Kurds across the region threatens to empower Kurdish separatism in Turkey. There is an overall sentiment that the West indirectly tried – and failed – to unseat Erdoğan by way of the coup, and is now trying to support Kurdish separatism. These concerns threaten to dismantle Turkey’s traditional alliances. The profound, self-perpetuating misunderstandings between Turkey and the EU harm their relationship on many levels – marginalising the long history of EU-Turkey engagement, as well as the large segment of Turkish society that is still committed to the EU’s values and the accession process.

One of the reasons Ankara and Moscow have become closer over the last few years is their shared perception that the West is trying to undermine their regimes using human rights concerns and civil society groups. This has long been Russia’s take on liberal democracy, but is a relatively new way of thinking for Turks – at least for the AKP elite that rose to prominence over a decade ago by promoting EU-led democratic reforms in Turkey. Although Turkish officials profess a commitment to democracy in general, in practice there seems to be a huge divergence between Turkey and the EU on the question of values. Turkish officialdom currently believes that protecting the state’s interests and national borders is more important than promoting individual rights. It is impossible to develop a functional relationship with Turkey’s current leaders without understanding their suspicion of the West and their perceptions of the coup attempt. Moreover, the highly paranoid, security-focused climate in Turkey likely prevents the country from returning to the EU reform process.

There are lessons here for both sides. Turks should recognise that human rights violations have pushed European concerns about the coup attempt into the background – that the international community has failed to adequately sympathise with Turkey over the incident due to the severity of the resulting crackdown. The EU should recognise that much of Turkish society (including many Turks who dislike the AKP) opposed the coup attempt and blames the Gülen network for it.

Western countries’ sluggish response to the incident contributed to the sharp deterioration of their relationships with Turkey. Europe should tread lightly on the topic of the coup, and with empathy. Statements that are dismissive of the coup attempt or its alleged perpetrators exacerbate Turkish suspicion that the West would have preferred a different outcome. To preserve their strategic relationship, the EU and Turkey must maintain a minimum level of public trust – or at least the shared belief that neither side is plotting the other’s downfall.

Relations with the EU are important but no longer a priority for Ankara. The stagnation in the EU accession negotiations is perfectly acceptable to the Turkish government – if not to the Turkish bureaucrats and diplomats who have toiled for decades to advance the process. Erdoğan sees no upside in advancing the accession process at the moment because that would involve ending the state of emergency and expanding freedoms. For him, it is far more important to sustain his alliance with the ultranationalist Nationalist Action Party (MHP) than to embark upon reforms that could revive the accession process. In the run-up to the 2019 presidential election, Turkey will continue to be inward-looking and polarised – making the suspension of accession talks or the continuation of the status quo equally irrelevant to the public debate. The EU has no means to alter Turkey’s position on the issue, but it should do what it can to avoid being vilified in Turkish public discourse once again. In particular, EU leaders should avoid polemic on Turkey’s mercurial president.

Meanwhile, Turkey is no longer a priority for Europe either. Since the migration deal of 2016, relations have been on the back burner, with much of Europe’s focus on its own future and immediate challenges. Reforming European institutions, the fallout from Brexit, and the surge of anti-European parties across the continent seem far more significant than the question of what to do about accession talks with Turkey. With the exception of those in Germany (where Turkey is part of the domestic debate due to its large Turkish diaspora community), European elections throughout 2016 and 2017 largely focused on the existential threat to pan-European ideals. In this atmosphere of urgency, Turkey was, at best, a sideshow.

Cooperation through the Council of Europe

As Turkey’s EU accession process is making no progress, the EU needs to find other channels through which to communicate and otherwise engage with Ankara. Following Turkey’s controversial April 2017 referendum on establishing an executive presidency, Erdoğan travelled to Brussels to meet with Donald Tusk and Jean-Claude Juncker, the presidents of the European Council and the European Commission respectively, as part of an effort to improve relations with the EU. After months of recriminations between the sides, Erdoğan’s trip generated some mutual optimism about the future of the relationship. However, there has been no apparent effort to create the road map for improving Turkish-EU relations reportedly discussed at the summit. The failure of talks on reunifying Cyprus in July 2017 caused further damage to Turkey’s relationship with the EU, which appeared to take on the volatility of the news cycle.

To help stabilise the relationship, Ankara and the Council of Europe should work together to address difficult issues such as human rights, the rule of law, and political freedoms in Turkey. They should do so outside the accession process, but in a way that helps Turkey meet the Copenhagen Criteria.

The Council of Europe rarely visits Ankara, despite Turkey’s status as a founding member of the organisation and the rapport Erdoğan has established with its secretary general, Thorbjørn Jagland. In spring 2017, the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly initiated a monitoring procedure to address its serious concerns about human rights and democracy in Turkey. Turkish leaders should view the process not as an aggressive act to be rebuffed, but as a tool for maintaining Turkey’s ties with European institutions. Indeed, the organisation values Turkey’s cooperation as a founding member. By working with the Council of Europe on a road map for addressing the organisation’s concerns, Ankara can demonstrate to Turkish and EU citizens the Council’s capacity to have a positive – even transformative – impact on Turkish democracy.

There is a particularly important role for the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in this regard. Turkish citizens have long held the institution in high esteem, while its verdicts are binding for Ankara as a member of the Council of Europe. The court has been careful and judicious in its approach to human rights cases and settlement demands since the coup attempt of 2016, despite criticism from Turkish human rights advocates over its long deliberations. Moreover, it has shown reluctance to take up cases before internal judicial proceedings have been exhausted. At the request of Council of Europe and ECHR, the Turkish government has established an independent body to evaluate complaints from nearly 120,000 purged government employees since the coup – though with mixed results.

In January 2018, Turkey’s constitutional court ordered the release of two prominent Turkish journalists who were among the dozens arrested since the coup. However, in a move that outraged rights activists around the world, the lower court has refused to implement the constitutional court’s verdict. The ECHR will ultimately take up the matter.

This is a delicate issue that Europeans need to handle carefully. The Turkish president does not want to see a challenge to his rule in the run-up to the 2019 election. However, it is extremely important for EU leaders Donald Tusk and Jean-Claude Juncker, who are scheduled to meet with Erdoğan in the Bulgarian city of Varna on 26 March, to persuade the Turkish leader of the importance of observing the constitutional court’s decision – and hence prevent the collapse of the rule of law in Turkey. At a time when there is talk of Russia leaving the ECHR, Europeans are reluctant to push Ankara too far about its outstanding human rights cases before the court. However, during their conversations with Erdogan, EU leaders should not compromise on the need to observe court rulings – as this case is directly linked to the credibility of Europe’s institutions.

The need to modernise the customs union

Part of Turkey’s charm for Europe has always been its economic potential. Turkey has the world’s 17th–largest economy and a population exceeding 80 million – a huge potential market for Europe. Thus, in 2010, the Economist described Turkey as the “China of Europe” – a metaphor that still applies today, albeit in a less positive fashion.[8] Turkey retains the potential to provide a significant boost to EU economies, but has adopted much of the indifference to democracy and human rights that Western countries often associate with China.

ECFR’s new survey confirms that Turkey’s economic potential remains critical to maintaining support for the accession talks among member states, with 61 percent of respondents believing that Turkish membership would provide economic opportunities for the EU. But the survey also reveals an awareness that this is untapped potential. Reflecting EU member states’ widely varying economic relationships with Turkey, only 11 percent of respondents saw it as being among their country’s “top five trading partners” – that is, those in just three member states: neighbouring Bulgaria, Greece, and Romania. The remainder described Turkey as a “minor trading partner”.

Clearly, part of Turkey’s appeal for the EU is its economic promise. In light of this, in 2017 Turkish and European policymakers proposed an initiative to upgrade the customs union agreement between Turkey and the EU. The same year, the European Parliament mandated the European Commission to explore the matter, while various Turkish institutions and think-tanks began to analyse the modernisation of the existing customs union deal as a means to deepen relations in a time of crisis.

However, following the bitter spat between Ankara and Berlin in summer 2017, the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, withdrew support for the idea, effectively shelving the proposal. “I do not see a mandate to expand the customs union in the current circumstances”, she said in August. Gabriel had already declared a new, harsher policy on Turkey: “Time and again, we have been patient, have held back and not retaliated in kind. Time and again, we have trusted that reason will prevail again and that we will find our way back to thriving relations. Time and again, we have been disappointed.”[9] Shortly after he warned that Turkey’s actions would have consequences, Berlin curtailed export guarantees, delayed defence deals, and issued travel warnings for the country. Germany’s new stance also made it difficult for European investment banks to underwrite Turkey’s ambitious infrastructure projects.[10] German policymakers quietly maintained the belief that the withdrawal of economic support was the best way to affect Turkish behaviour[11] – a sentiment that led EU leaders to slash pre-accession aid to Turkey.[12]

But the cold war between Turkey and Germany was short-lived. The veiled threat of economic sanctions brought about a thaw in Turkish-German relations. Ankara reached out to Berlin in late November 2017 with the aim of mending relations; after talks between Çavuşoğlu and Gabriel, the initiative appeared to be succeeding. The Turkish government ended its criticism of European leaders – the Nazi comments and allegations of European support for terrorism – and opened direct channels of communication with Berlin, Paris, and several other capitals. This was not about drawing closer to the accession process but about fixing bilateral ties with major European powers to maintain Turkish economic growth, especially at a time when Turkey was having difficulty attracting investment and its economy was starting to show signs of vulnerability. Today, Ankara regards a customs union upgrade as a way to shore up the economy.

Another reason for Ankara’s effort to mend fences with Europe has to do with the deterioration of its relations with Washington. With the US and Turkey increasingly at odds over issues such as the former’s support for Syrian Kurds and the latter’s purchase of S-400 missiles from Russia, and with talk of impending sanctions on Turkey from the US Congress, Ankara felt compelled to bolster its ties with European countries.

Regardless of what happens on the larger strategic chessboard, it is still a good idea for the EU to revisit the idea of modernising its customs union with Turkey – but after the 2019 presidential election, to avoid criticism from European and Turkish citizens, particularly Erdoğan’s opponents in Turkey, that this is a gift to him from Europe. The Turkish and EU economies are deeply integrated, with the bulk of Turkish exports going to Europe. By modernising its customs union with Turkey, the EU could increase that interdependency in a way that could moderate their political disputes. This would also boost a Turkish economy which is showing signs of vulnerability due to its huge current account deficit and problems with high inflation. The process of negotiating a customs union would give the EU some leverage on issues such as labour laws, human rights, and dispute settlement. It would be an exaggeration to say that modernising the customs union would indirectly cause Turkey to return to a governance model based on the rule of law. But doing so would introduce a new dynamism to the relationship and allow more Turkish-European interaction to discuss the rule of law, as well as labour and human rights issues, in Turkey.

Turkey’s trade with the EU has benefited the country’s business community and civil society organisations – both pro-Western and largely supportive of a strategic alliance with Europe – more than anything else. Despite the ups and downs of the accession process, that economic anchor to Turkish society ought to be preserved through deeper economic integration.

Regardless of what happens in Turkey’s accession process, the existing customs union agreement, signed in 1995, is outdated and needs to be revised. Having lost lucrative trade with Middle East economies and suffering from an investment deficit due, in part, to the state of emergency and domestic instability, Ankara is eager to update the customs union with the EU. For Turkey’s current leadership, it is now a higher priority than rebooting the accession process – partly because attempts to push the accession process forward seem unrealistic. For Turkey, while the dormant state of accession talks is acceptable, losing trade with the EU is not. While Erdoğan may not see EU membership as a realistic goal, he would like to maintain European investment in Turkey. The Turkish president has publicly praised Brexit and repeatedly suggested that Britain’s future relationship with the EU might be a model for Turkey.[13] Ankara is increasingly inclined to compartmentalise political and economic integration with Europe. Although their government has little patience with the Copenhagen Criteria, Turkish officials have a zeal for European investment and often emphasise their belief that the size of Turkey’s market prevents Europeans from abandoning the country.

The new ECFR survey reveals that there appears to be a similar appetite in Europe as well, given that most respondents said that their country’s trade with Turkey was limited but that economic relations with the country provided an important reason for maintaining the alliance. Most EU officials admit that if Germany were willing to give a green light on modernisation negotiations, the European Commission would be able to move forward. But timing is important here. The EU should be sensitive to Turkey’s electoral calendar to avoid criticism that the announcement of these negotiations is intended to give Erdoğan an electoral boost.

Poorly funded Turkish civil society

Following an EU Council summit in October 2017, Tusk admitted that “the scepticism when it comes to the Turkish accession process was yesterday very, very visible”, and that EU leaders had asked the European Commission “to reflect on whether to cut and re-orient” Turkey’s pre-accession aid, or Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA) funds. Yet this is a bad time to deprive Turkish society of much-needed external support. Instead of slashing accession funds, European leaders should redirect these resources towards Turkish civil society, media, academia, municipalities, minorities, and non-governmental organisations that promote democracy, pluralism, and free speech. Of the roughly €800m in EU funding Turkey receives annually, only €30m goes to civil society. EU officials explain this imbalance by complaining that Turkish civil society organisations do not have enough capacity to absorb more funding. But this is hardly true. Turkey has a wide range of civic initiatives, non-governmental organisations, municipal initiatives, and citizens’ initiatives that are untouched by the EU’s largesse. Brussels should reach beyond Turkey’s human rights- and EU-themed organisations to the dynamic segments of society that make up the diverse and pluralist political culture of modern Turkey, particularly those in Anatolia.

So far, the EU’s distribution of IPA funds has failed to make a noticeable difference to Turkish society or boost pro-European sentiment across the country, despite the fact that it has made €4 billion available through the scheme during the past decade. There is little knowledge in Turkish society of how to gain access to European funds, and even less of an effort by the Turkish government to highlight Turkey’s European orientation. The bulk of Turkey’s EU-funded projects are those that are carried out in cooperation with the government – and for which the EU gets little credit.

This is precisely where EU institutions can do most to support Turkish society – particularly pockets of society that lack capacity and are unaffected by the accession process, including Kurdish initiatives, non-Muslim minority schools, Syrian refugees, academic and arts organisations, and municipal initiatives across the Anatolian heartland. Funding for civil society and municipalities should highlight the EU’s importance to, and help protect pluralism in, Turkish society. These do not have to be political initiatives, as Ankara might view such collaboration as interference in its domestic politics. But since Turkey is already receiving substantial funding, and since it is still in accession negotiations, the imbalance between official and unofficial projects needs to be addressed.

The EU should also consider starting a separate programme to provide resources for struggling independent media outlets in Turkey. Although Turkey’s imprisonment of journalists is a major topic in Europe, little has been done to support existing independent Turkish media outlets, most of which are struggling under the government’s encroachment on free speech, public criticism, and economic difficulties.

The EU could also consider establishing educational programmes and even a university in the country.

The politics of the Turkish diaspora

Another important reason for Europe to establish a special relationship with Turkey while the accession process remains dormant relates to the Turkish diaspora in many leading EU countries. Once viewed as the glue between Turkey and Europe, the diaspora and its politics have become a source of tension over the past two years as Ankara has continued to drift away from European norms and values.

Like Turkey’s domestic population, the Turkish diaspora in Europe is divided. The diaspora includes people involved in various waves of migration, including the “gastarbeiters”, who were invited to Germany to work as labourers in the 1960s; the Kurds, Alevis, and leftists who sought political asylum following Turkey’s military coup of 1980; and those who fled the purge that began following the July 2016 coup attempt. This heterogenous diaspora includes people of different ethnicities, religions, hometowns, and political leanings – all factors that contribute to how they define their roles and identities in Britain, Germany, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, and elsewhere, as well as how they relate to the government of Turkey itself.

With the rise of the AKP, Turkey sought to improve its ties with the diaspora in many countries – most notably Germany, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands – and to this end invested in consular services, communications, and grassroots organisations. Turkey also provided religious services and imams through its Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) in these EU states – which were content for their Turkish-Muslim communities to gravitate towards Turkey’s moderate, state-sanctioned interpretation of Islam rather than that of Salafist or other radical groups. The AKP government established a key role for Diyanet in Sunni communities that form part of the diaspora.

This began to create problems as Turkey drifted away from the EU accession process and the AKP started relying on overseas ballots to tip the scale in national elections. Following the July 2016 coup attempt, Ankara started to see EU criticism of its human rights record as a threat, while the EU increasingly regarded Turkey’s growing authoritarianism as incompatible with EU membership. The AKP government also started to rely on dual citizens from conservative segments of the diaspora for votes at home and to rally support in Europe. In Germany, where there are more than 3 million people with origins in Turkey, questions about a ‘fifth column’ entered the public debate, not least due to growing anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant sentiment among far-right populists.[14]

Meanwhile, EU governments grew ever more concerned that they would import Turkey’s bitter polarisation between supporters and opponents of Erdoğan. The crisis came to a head in April 2017, when Germany and the Netherlands forbade the Turkish president from campaigning for the referendum on the executive presidency in their territory. This led to one of the most damaging chapters in Turkey’s relations with EU, an episode that adversely affected the Turkish diaspora in Germany. Around 1.4 million members of the German-Turkish community have dual citizenship and have been allowed to vote in Turkish elections since 2014. The majority of them have voted for Erdoğan.

ECFR’s new survey reflects the contradictions in EU attitudes towards the links between Turkey and the diaspora. Countries including Belgium, France, Denmark, and Germany came to view Turkey’s religious influence through Diyanet as a blessing and a curse. The blessing was the moderate nature of Turkey’s official interpretation of Islam; the curse the worry that the Turkish government was spying on its diaspora using imams.[15] ECFR research reveals this to be a persistent theme in bilateral relations in countries where there is a sizeable Turkish-Sunni community. For example, Denmark is concerned that pro-AKP Turkish imams employed by Diyanet are reporting on suspected Gülenists within the Danish-Turkish community. The Danish ministry of foreign affairs summoned the Turkish ambassador to discuss the issue twice in 2017.

There is similar debate in Germany about Turkish-financed mosques and the influence of the Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (DITIB). DITIB is a federation of around 900 Turkish-Islamic mosque associations located throughout Germany and falls within Diyanet’s jurisdiction – in line with agreements between Ankara and Berlin. In February 2017, Germany accused six Turkish imams of espionage, alleging that they were gathering information on suspected Gülenists in the German-Turkish community.[16] The dispute foreshadowed the greater crises during the Turkish referendum and the German election later that year.

Whatever happens, European nations will have to maintain a working relationship with Ankara on issues related to the diaspora and citizens’ rights. Due to the presence of roughly 1.5 million dual nationals in Germany alone, there are a wide range of issues that require bilateral cooperation – from consular services to voting booths to Turkish-language education. It is not possible to fully prevent Turkey’s domestic polarisation from spilling into the European debate – especially in countries where there is a sizeable Turkish-Kurdish community. But it is possible to limit tensions around election time. Dual nationals cannot be prevented from taking part in Turkish elections – but the EU should take a decision that lays out the ground rules for Turkish leaders’ campaigns in EU states. Can Turkish ministers hold campaign rallies in German cities? Can the opposition raise funds there? Similarly, are Kurds allowed to hold rallies in support of the PKK or Syrian Kurdish groups – both of which Turkey considers to be terrorists? What is the role of the local government and the federal authorities in obtaining these permits? These thorny questions need to be sorted out before Turkey’s 2019 election.

Cooperation on Syria and Iraq

In recent years, Turkish foreign policy has largely focused on the Middle East, particularly Syria and Iraq. Although it has long abandoned its dreams of leading the region in a new Pax Ottomanica, Ankara remains preoccupied with events in its neighbourhood. The growing Kurdish influence across the region and the contortions of the Syrian civil war remain priorities on Turkey’s foreign policy agenda.

Despite these preoccupations, Turks and Europeans do not work together on foreign policy issues. Even though migration is one of the main concerns for Brussels and politicians across Europe, there is a remarkable lack of European interest and involvement in Middle East conflicts, particularly those in Iraq and Syria. The 2016 EU-Turkey migration deal has curbed the flow of refugees and other migrants into Europe for now, but Europe’s migration concerns will persist at least until Syria and Iraq – two of the main sources of refugees fleeing to Europe – attain some degree of stability. Turkey and the EU have broadly similar goals on the stabilisation of Syria and Iraq, but the sides rarely work on these issues together.

It is important for European institutions and policymakers to develop a closer working relationship with Turkey on the stabilisation of the region. Almost 70 percent of respondents to ECFR’s new survey said that their country’s policy on the Syrian war aligns with Turkey’s.

Like Turkey, European countries have largely opposed the establishment of new borders or divisions in the Levant, the Kurdistan Regional Government’s 2017 independence referendum in Iraq, and US President Donald Trump’s decision to recognise Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. But, while European and Turkish intelligence officials often engage in bilateral cooperation, work to stabilise the Middle East between their counterparts in defence and foreign ministries is more limited.

There is a simple bureaucratic reason for this: as most European foreign ministries view Turkey through the lens of EU enlargement, officials who work on the country tend to have expertise on enlargement, eastern Europe, and the Balkans but not necessarily the Middle East. Similarly, defence cooperation between Turks and Europeans often takes place through the NATO framework and is less focused on Middle East conflicts. Meanwhile, European officials who work on Syria or Iraq may focus on Turkey’s role in these countries but lack detailed knowledge of, or insights into, the domestic politics that often shape Ankara’s foreign policy.

But Turkey is both a European and Middle Eastern country. European governments could work more closely and effectively with Ankara on Middle East issues by developing a better understanding of their shared interests in the region, particularly in the stabilisation and reconstruction of war-torn regions of Syria and Iraq, and in curbing jihadist influence in these countries. Turkey has an interest in stabilising countries on its southern border and has emerged as a key participant in the Russian-led Astana process on the Syrian conflict. Ankara is also interested in bolstering its role as a leader of Sunni Muslims in the region. Despite criticising Ankara’s treatment of Turkish Kurds, the EU largely shares its opposition to the establishment of an independent Kurdish state in Syria or Iraq. The sides also have a common interest in containing jihadists in the Middle East. To address these concerns, the EU needs to develop a working relationship with the Turkish government on the stabilisation and reconstruction of northern Syria, Iraqi Kurdistan, and the disputed territories of Iraq, including the oil-rich town of Kirkuk. Such cooperation is also important in developing representative governance structures in Sunni Arab towns in northern Syria and Iraq that the Islamic State group once occupied – such as those between the Syrian towns of Jarablus and Azaz, which Turkish forces gained control of during Operation Euphrates Shield. This would help the EU achieve its energy security and foreign policy aims, because Turkey’s security and stability are closely intertwined with developments in Europe’s southern neighbourhood.

This does not mean ignoring Turkey’s deteriorating domestic political culture and human rights record, nor agreeing with its crackdown on legitimate Kurdish representatives in the country. But it does mean developing a more comprehensive approach to Turkey, especially within EU and member state institutions that cover Middle East issues, bilateral ties with Turkey, and the accession process.

Turkey’s participation in the Astana process is also important for Europe, especially in stabilising Idlib and other areas that have become a hotbed for al-Qaeda affiliates. Within the Astana framework, Ankara continues to support the United Nations-led Geneva initiative and share Europe’s ultimate aim for a peaceful political transition in Syria. Finally, the EU should support Turkey’s attempts to create a habitable safe zone for refugees in the swathe of territory between Jarablus and Azaz that Turkish forces captured during Operation Euphrates Shield in 2016.

Conclusion

It is not all over for Turkey and Europe, despite the trench warfare that took place during 2016 and 2017 between Ankara and various European capitals. As ECFR’s new survey reveals, among European elites there is still strong support for deeper relations and the idea of “Turkey and Europe” – albeit little demand to move Turkey’s beleaguered accession process forward. This leaves only one option for the EU and Turkey: downgrade the accession process, focus on bilateral relations, and build a new lexicon around the concept of “Turkey and Europe”, as opposed to “Turkey and the EU”.

Within that new framework, there is a lot that can be done to build momentum in Turkey’s relations with Europe. Modernising the existing customs union with the EU, deepening counter-terrorism and energy ties, developing human rights dialogue through the Council of Europe, and stabilising the Middle East are a few obvious areas of cooperation. Economic cooperation through transactional bilateral arrangements is another. The EU can still maintain ties to Ankara and Turkish civil society through existing enlargement channels. But enlargement cannot be the defining principle of Turkey’s relations with Europe at a time when Ankara has deviated from Copenhagen Criteria and an inward-looking Europe has little appetite for enlargement.

Within that new framework, there is a lot that can be done to build momentum in Turkey’s relations with Europe. Modernising the existing customs union with the EU, deepening counter-terrorism and energy ties, developing human rights dialogue through the Council of Europe, and stabilising the Middle East are a few obvious areas of cooperation. Economic cooperation through transactional bilateral arrangements is another. The EU can still maintain ties to Ankara and Turkish civil society through existing enlargement channels. But enlargement cannot be the defining principle of Turkey’s relations with Europe at a time when Ankara has deviated from Copenhagen Criteria and an inward-looking Europe has little appetite for enlargement.

Austria

Relations with Turkey are most important in: Refugees

Austria has always been one of the European Union’s most vocal critics of Turkey. Austrians generally regard Turkey as separate to Europe, believing that the 250,000 members of Austria’s Turkish community have failed to integrate with the rest of the country. In 2016, around 85 percent of this community perceived a rise in Islamophobia in Austria, while around 43 percent wanted to leave the country. According to another poll conducted the same year, approximately 80 percent of Austrians opposed Turkey’s bid for EU membership. Since then, Ankara’s response to the July 2016 coup attempt in Turkey – along with its efforts to block Austria’s participation in NATO partnership programmes – have only reinforced this scepticism.

Austria has asked its EU partners to formally suspend Turkey’s accession talks, and continues to press for a European border control system that would supersede the 2016 EU-Turkey refugee deal. No high-ranking Austrian politicians have officially visited Ankara since 2012. Taking its lead from Germany and the Netherlands, Austria forbade entry to the Turkish economy minister while he was campaigning for the April 2017 Turkish constitutional referendum.

Vienna partly blames President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan for the perceived erosion of Turkish democracy, not least due to his role in the referendum. Austrian leaders have stated privately and publicly that he is transforming Turkey into an authoritarian country that has little respect for European values.

Both the Austrian government and the public are strongly against Turkey’s EU membership.

Austria thinks Turkey’s EU process should be kept frozen as it is.

1.07 percent of our total exports is with Turkey

Turkey is a minor trading partner

Quotes from the survey:

“There has been no change in public opinion or government policy on Turkey in the last two years”

“The 2016 coup attempt was an excuse for the government’s crackdown on dissidents”

“The EU should be more outspoken on human rights and democracy in Turkey”

Belgium

Relations with Turkey are most important in: Security/Counter-terrorism

Belgium regards its relationship with Turkey as a pragmatic partnership. While Belgium’s right-wing parties overemphasise Ankara’s role in combating terrorism and managing the refugee crisis, its left-wing parties tend to focus human rights issues in Turkey. Despite these differences, Belgian parties across the spectrum have voiced concern about the concentration of power in the Turkish executive, particularly following Turkey’s 2016 coup attempt. They argue that the country now fails to meet the European Union’s Copenhagen Criteria. The Belgian public has also developed an increasingly negative view of Turkey since 2014, when 68 percent of Belgians opposed Turkish accession to the EU.

Formalised by the 2008 trilateral platform, the Turkey-Belgium relationship focuses on terrorism, asylum, and migration issues. Belgian officials view Turkey as key in monitoring the movements of foreign fighters who have joined terrorist groups in the Middle East. Yet they are also concerned about the Turkish authorities’ treatment of Kurds, particularly as the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and the Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front are active in Belgium. An ongoing Belgian legal case involving the PKK has the potential to exacerbate tensions between Brussels and Ankara, as do the applications for Belgian citizenship made by several members of the Turkish opposition who fled to Belgium following the coup attempt.

Although the Turkish diaspora constitutes around 2 percent of the Belgian population and forms an important historical and cultural component of the bilateral relationship, Turkey appears to have little impact on Belgium’s domestic politics.

The Belgian government is agnostic towards Turkey’s EU membership while the public is against it.

Belgium thinks Turkey’s EU process should be kept frozen as it is.

Turkey is our 14th trading partner

Turkey is a minor trading partner

Quotes from the survey:

“There has been a change in public opinion and government policy on Turkey in the last two years”

“The 2016 coup attempt was too confusing to understand what really happened”

“The EU should be more outspoken on human rights and democracy in Turkey”

Bulgaria

Relations with Turkey are most important in: Refugees

Bulgaria has relatively good ties with Turkey, but underneath their neighbourly relations lies an understanding that a Turkey within the EU accession process is less of a threat than one with regional ambitions and resurgent Turkish nationalism. There is a live debate in Bulgaria about the Ottoman legacy and the extent to which AKP policies are mimicking this. Still, Bulgaria consistently regards Turkey as a key neighbour and a strategically important NATO ally, as well as one of its five most important trade partners, a major investor, and a leading destination for Bulgarian tourists. Sofia is reluctant to jeopardise its relationship with Ankara because it values Turkish cooperation in controlling the flow of refugees and other migrants into Europe.

Yet President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s reaction to Turkey’s July 2016 coup has caused further damage to the country’s image among Bulgarians, many of whom believe he used the incident to advance his Islamist agenda. They perceived Turkey as having directly interfered in the domestic affairs of the Netherlands and Germany, primarily through the Turkish diaspora. For brief periods in 2015-2016 and early 2017, Bulgarians viewed Turkey as meddling in their country’s domestic affairs, leading Bulgaria to expel Turkish diplomats and forbid entry to other Turkish citizens.

The Bulgarian government is agnostic towards Turkey’s EU membership while the public is against it.

Bulgaria thinks Turkey’s EU process should be kept frozen as it is.

Turkey is our 5th import and 4th export partner

Turkey is in our top 5 trading partners

Quotes from the survey:

“There has been a change in public opinion on Turkey in the last two years, while government policy has remained the same”

“The 2016 coup attempt was an excuse for the government’s crackdown on dissidents”

“The EU should not be too outspoken on human rights and democracy in Turkey because it could jeopardise other interests”

Croatia

Relations with Turkey are most important in: Refugees

Regarding itself as a friend of Ankara, Zagreb has traditionally expressed strong support for Turkish accession to the European Union. Yet, since the July 2016 coup attempt in Turkey, Croatia seems to have to kept to the margins of the accession negotiations. This may be because, for the Croatian public, domestic media coverage of Ankara’s crackdown on the opposition during the period has caused considerable damage to Turkey’s image as a modern and democratic state.

Prime minister Andrej Plenković has stated that cooperation with Turkey can only proceed if the country adheres to fundamental democratic norms. However, Croatian officials maintain a cautious approach to Ankara, combining any criticism of Turkey with an effort to emphasise the country’s importance in addressing the refugee crisis. Moreover, Croatia supports all EU endeavours designed to promote security cooperation with Turkey, not least those involving the war in Syria. In this, the countries have shared intelligence related to money-laundering and terrorist financing.

Zagreb regards Croatia-Turkey economic ties as relatively unimportant. Although popular Turkish TV series and writers present an image of modern Turkey to the Croatian public, Ankara has little, if any, influence on Croatia’s domestic politics and wider society.

The Croatian government strongly supports Turkey’s EU membership while the public is indifferent or has no view towards it.

Croatia thinks Turkey’s EU process should be kept frozen as it is.

Turkey is our 18th most notable foreign investor

Turkey is a minor trading partner

Quotes from the survey:

“There has been a change in public opinion on Turkey in the last two years, while government policy has remained the same”

“The 2016 coup attempt was a real coup and thus a threat to democracy”

“The EU should be as outspoken on human rights and democracy in Turkey as it is now”

Cyprus

Relations with Turkey are most important in: Values

Cyprus is the only member of the European Union that Turkey does not recognise diplomatically. The Cypriot government officially regards Turkey as an occupying foreign power, as the country maintains a deployment of around 40,000 soldiers in northern Cyprus, protecting a de facto state that only Turkey recognises diplomatically. In July 2017, talks on reunifying the island failed after the Greek-Cypriot side rejected a Turkish-Cypriot proposal to grant Turkey and two other guarantor states the right to intervene in Cyprus. The Greek-Cypriot public perceives Turkey as an aggressive nation.

Cyprus believes that the sides will have the opportunity to cooperate with Turkey, particularly on trade and transport, once they have restored their diplomatic relationship. Cyprus continues to insist that Turkey recognise all EU member states in line with a 2005 EU declaration, to no avail. Given this tension, it is possible that Cyprus would impede any negotiations on upgrading the EU-Turkey customs union. Nicosia appreciates the 2016 EU-Turkey refugee deal for having relieved pressure on Greece’s institutions by reducing the flow of people into the country, but it nonetheless maintains a veto over five chapters of Turkey’s EU accession negotiations.

Turkey’s imposition of increasingly conservative Islamic practices on Turkish-Cypriots causes some concern among Greek-Cypriots. There was a drastic decrease in the number of Cypriot tourists visiting Turkey in 2016, likely due to a series of terrorist attacks and the failed coup there. Many Cypriot politicians worry that Turkey’s perceived drift towards authoritarianism will harden its position on the Cyprus conflict.

The Cypriot government supports Turkey’s EU membership while the public is against it.

Cyprus thinks Turkey’s EU process should be kept frozen as it is.

Around €520,000 worth of exports and €112,000 worth of imports come from Turkey

Turkey is a minor trading partner

Quotes from the survey:

“There has been no change in public opinion or government policy on Turkey in the last two years”

“The 2016 coup attempt was an excuse for the government’s crackdown on dissidents”

“The EU should be more outspoken on human rights and democracy in Turkey”

Czech Republic

Relations with Turkey are most important in: Refugees

The Czech Republic regards Turkey as a partner, albeit a difficult one. In recent years, there has been a substantial decline in support for Turkey among Czech citizens, partly due to growing Islamophobia. Although Prague’s official position on Turkey has not changed in this period, its view of the country is becoming more negative due to the perceived increase in Ankara’s authoritarianism. The Czech government regards the Turkish authorities’ response to the July 2016 coup attempt as an effort to undermine democracy and human rights. Prague views the rapid changes in Turkey’s interactions with Russia and Israel as evidence that relationships with Ankara are inherently unstable.

Prague officially supports Turkey’s fight against terrorism, the 2016 European Union-Turkey refugee deal, and Turkish membership of the EU (assuming Ankara meets the accession criteria). According to a poll conducted in December 2016, only 2 percent of Czech citizens trust President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan – the lowest score for any foreign political leader. The same poll shows that most Czech citizens do not recognise him, indicating Turkey’s lack of influence on, and involvement in, Czech domestic politics.

The Czech-Turkish bilateral agenda centres on, inter alia, pressure from the Turkish government to extradite, or otherwise limit the activities of, supporters of US-based cleric Fethullah Gülen. This pressure has created economic losses for the Czech Republic. Much to Prague’s surprise, Turkey reacted relatively calmly to the Czech chamber of deputies’ April 2017 resolution condemning the Armenian genocide.

The Czech government supports Turkey’s EU membership while the public is against it.

The Czech Republic thinks the EU should open new chapters with Turkey.

Turkey is our 19th trading partner

Turkey is a minor trading partner

Quotes from the survey:

“There has been a change in public opinion on Turkey in the last two years, while government policy has remained the same”

“The 2016 coup attempt was a real coup and thus a threat to democracy”

“The EU should be as outspoken on human rights and democracy in Turkey as it is now”

Denmark

Relations with Turkey are most important in: Refugees

Danish policy on Turkey has changed significantly in recent years, particularly since the July 2016 failed coup attempt in the country. This is largely due to Danish leaders’ and civil society groups’ perception of the Turkish government as increasingly authoritarian. Media coverage of Turkey has risen sharply in Denmark since the finalisation of the EU-Turkey refugee deal in 2016. The Turkish government’s widely reported efforts to finance imams in Denmark – and Turkish diplomats’ alleged attempts to spy on supporters of influential cleric Fethullah Gülen in several European countries – have outraged Danish leaders and members of the public. Danes generally agree that there is a lack of evidence Gülen was involved in the coup attempt.

The Danish government has a pragmatic approach to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, recognising his sometimes controversial style and rhetoric as primarily directed at a domestic audience. In its dealings with Turkey, Denmark has increasingly moved away from values-based politics and towards transactional diplomacy, with trade and immigration the focal points of the relationship. Partly due to its high-profile anti-immigration policy, the Danish government benefits from the 2016 EU-Turkey refugee deal, a popular topic in Danish public discourse.

Denmark aims to block Turkey’s accession to the EU while maintaining the refugee deal. Indeed, the foreign minister, Anders Samuelsen, has stated that the accession negotiations should come to a “full stop” if the current political situation in Turkey continues. This attitude hardened in June 2017, when the Turkish police detained a Danish LGBT activist at the Istanbul gay pride parade.

The Danish government strongly supports Turkey’s EU membership while the public is indifferent or has no view towards it.

Denmark thinks the EU should devise an alternative agreement with Turkey, such as privileged partnership.

Turkey is our 23rd largest export market

Turkey is a minor trading partner

Quotes from the survey:

“There has been a change in public opinion and government policy on Turkey in the last two years”

“The 2016 coup attempt was too confusing to understand what really happened”

“The EU should be as outspoken on human rights and democracy in Turkey as it is now”

Estonia

Relations with Turkey are most important in: Values