Untapped potential: How new alliances can strengthen the EU

Summary

- Coalition-building is increasingly important within the European Union, helping anchor member states to one another at a time of severe political fragmentation.

- Brexit is changing the roles of, and relationships between, many member states as they actively seek new partnerships and coalitions.

- France and Germany remain essential to building majority voting coalitions but, finding it difficult to work with Italy, they need to improve their relationships with Spain and smaller, affluent member states.

- There is a persistent partnership gap between the EU’s east and west: the Baltic states are linked to the west only via Nordic countries, while the Visegrád group suffers from the weakness of the German-Polish relationship, and south-eastern European and Western Balkans member states have tenuous links to the rest of the EU.

- A new coalition between smaller, affluent countries – one that is open to others such as the Baltic states, Ireland, Portugal, and Slovenia – could become important to the new architecture of the EU.

- This new coalition could work with France and Germany, as well as pro-integration southern and eastern states, to strengthen the influence of its members.

Introduction

For the past decade, the predominant narrative on the European Union has been one of fragmentation rather than cooperation. The main issues that have divided European governments and societies have been reform of the eurozone in a way that fully addresses its structural flaws; the arrival of unprecedented numbers of refugees and migrants in Europe; the challenge to the “Brussels consensus” from increasingly popular sovereigntist parties; and the impending departure of one of the EU’s largest member states, the United Kingdom.

However, none of the gloomiest predictions for the EU in recent years – such as the collapse of the eurozone or even the union itself – have come to pass. In light of Brexit, European governments of all political stripes may now understand the value of EU membership more than ever before.

Nonetheless, there is a gap between EU governments’ declared willingness to stick together under the roof of the union and their capacity for collective action. This gap is alarming. If the EU is to fail in the coming years, it is unlikely to do so through an outright breakup. It is much more probable that the union will no longer be able to jointly respond, within a reasonable period of time, to a rapidly changing European and global environment. Hollowed out from within by institutions that are increasingly unable to produce results, such an EU would not necessarily cease to exist – but it would surely face irrelevance.

In 2016, against the backdrop of rising demand for collective action, the European Council on Foreign Relations set out to help shape strategies for improving cooperation between European capitals. This original, pan-European project on coalition-building draws on a survey of hundreds of policymakers and policy experts in governments and think-tanks across all 28 EU member states. ECFR has assessed and presented the results of the surveys in an interactive PDF entitled the EU Coalition Explorer: the first edition was published in 2016, and the second, based on a new round of research, in 2018. (The hyperlink also provides the survey’s raw data for both 2016 and 2018.)

The 2018 edition met with particularly strong interest in governments across the EU. Much of this interest has been driven by Brexit. Many governments assumed that the UK’s departure from the union would trigger a broad shift in intra-EU relations as it would have a significant effect on several member states. Widespread interest in the EU Coalition Explorer has also reflected a growing need to overcome the deadlock in an increasingly antagonistic EU, by working more frequently and effectively with like-minded partners.

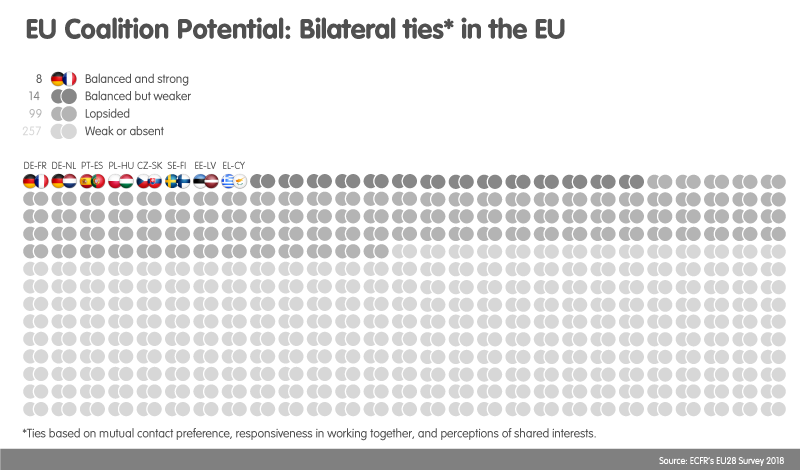

Why do coalitions matter? Simply put, cooperation between member states is key to a functioning EU. One might assume that, with European integration having progressed for more than 60 years, member states would have developed sophisticated strategies for cooperating with one another. Yet, as ECFR’s research reveals, they often struggle to build coalitions to achieve common goals: a map of all possible interactions between the EU28 shows that there are only eight strong and balanced bilateral relationships between member states. Fourteen others are balanced but weak; 99 are lopsided (involving a country that has a largely unreciprocated interest in another); and 257 are weak or bordering on non-existent.

An important reason for this is that, in a union that has become ever more integrated in the past three decades, EU governments have expected their bilateral relationships with one another to lose relevance – and to be increasingly replaced by their interactions through common institutions in Brussels. Another reason for the underperformance of these relationships is the significant geographical expansion of the EU since the early 1990s. The Maastricht Treaty was signed in 1992 by 12 member states. By 2007, the union had 27 members. And Croatia joined the EU in 2013. Navigating these states’ complex collection of interests requires considerable resources and strategic planning. Against this background, ECFR’s research helps identify areas in which European governments can reach out to one another and find common ground.

The EU Coalition Explorer analyses the cooperation patterns, policy priorities, and partnership preferences of all EU governments. By examining national preferences, assessing overall influence, and matching potential partners with policies of shared interest, the EU Coalition Explorer reveals the prospects for further engagement between capitals. The study can also be used as an interactive tool for locating the political centre – or centres – around which member states can build a more capable and cohesive union. To understand the EU Coalition Explorer’s findings, it is important to recognise that it does not explore the voting patterns of member states at the Council of the EU (an important analysis that other studies have covered for many years). Instead, ECFR’s research focuses on respondents from the Europe departments of relevant ministries and state chancelleries in national capitals.

Methodologoy

The EU Coalition Explorer is an interactive data explorer presenting the results of the EU28 Survey on coalition building in the EU. It illustrates the expert opinions of 877 respondents who work on European policy in governments and think-tanks. In conducting the EU28 Survey, ECFR used an anonymous online questionnaire in which every question was mandatory. The invitations were sent by email to foreign ministries, government and parliament offices, think-tanks, research institutions, journalists, and other organisations that work on European affairs. The 2018 Survey edition ran from 24 April to 12 June 2018 and included 20 standardised questions. The explorer and the complete data set can be accessed free of charge at www.ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer.

ECFR tested the practical relevance of its data from these sources in briefings and seminars with key decision-makers, as well as other members of the think-tank community in almost all EU capitals. This policy brief reflects more than 100 such debates, most of which took place between May 2017 and May 2019 across the EU. It aims to develop key lessons for all decision-makers in European capitals who are committed to keeping the union together, and to building coalitions that improve the health and vitality of EU institutions and member states.

One way of doing this is to devote deeper thinking and greater capacity to strategies for active coalition-building. ECFR assessed the potential of new coalitions that, based on ECFR’s data, could be formed on a range of policy issues, and tested their capacity to shape the European agenda. In this, ECFR generates fresh ideas about coalitions that go well beyond established formats such as the Franco-German tandem or the Visegrád group (comprising the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia).

Europe’s changing coalition landscape

Coalition-building essentially serves four main purposes. Firstly, coalitions are a tool of governance in today’s largely intergovernmental EU. Secondly, they have become an instrument for creating majorities, reflecting consensus on various issues in an environment dominated by veto players. Thirdly, coalitions provide the flexibility to vary European integration, allowing groups of member states to deepen cooperation in areas of shared interest. Fourthly, coalitions focused on select policy issues can help build trust in the value of collective action, thereby promoting cooperation in an often antagonistic European environment.

But a trend towards fragmentation in the EU makes it increasingly difficult for member states to build coalitions. This fragmentation has involved the disappearance of traditional, long-standing coalitions such as those between the EU’s founding members (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands), the net contributors to the EU budget, and even the so-called “Club Med” centred on France, Italy, and Spain. Each of these alliances was once a force to be reckoned with.

Another source of fragmentation has been member states’ pursuit of short-term advantage, which is gradually erasing the benefits of the integration process. Fragmentation is also increasing due to growing nationalism in the political discourse of many member states, where far-right parties exploit widespread fear of globalisation and migration. While there is a lack of consensus between them on many issues, these parties have a shared interest in reversing European integration and returning sovereign rights to the national level. And the most obvious sign of fragmentation – Brexit – has had a significant impact on coalition-building. The prospect of the UK’s departure from the EU has led member states to reposition in ways that go well beyond the issue of the Irish border or the loss of one of the Netherlands’ key partners.

In this environment, the formation of coalitions requires a deep understanding of one’s own strengths and weaknesses. European policymaking, however, suffers from gaps in mutual understanding because, as ECFR’s data show, governments tend to overstate their own commitment to deeper European integration and overestimate their influence on policy outcomes – as measured against the views other governments hold of their level of commitment or influence. Such misperceptions of oneself and one another most likely result from a self-centred approach to EU policymaking and a decline in interaction and communication between governments. National leaders seem to talk to national audiences more than they listen to them, leading to overconfident governmental action that can create frustration or resentment at home when it fails to deliver to achieve its goals in Europe.

Put another way, such gaps in knowledge lead to action based on misleading assumptions. A case in point is the British government’s expectation that it would find allies for its negotiating position on the EU withdrawal agreement in traditional partners, such as Germany, the Netherlands, and the Scandinavian countries. The UK badly misread its standing among these countries and, as a consequence, its influence on them.

All these factors make it challenging to build coalitions that bring about innovation at the EU level. Nonetheless, as this paper discusses, the policymaking preferences of European governments tell us a great deal about areas in which they could work together.

Five broad lessons from national capitals

As ECFR’s discussions with policymakers and policy experts have revealed, each member state has something to learn about its networks of cooperation and influence within the EU (or lack thereof). Although it is important to examine ECFR’s data on a national basis, one can draw some broad lessons from the EU Coalition Explorer.

ECFR’s discussions of the study’s results in European capitals have produced five main lessons. Firstly, the theme of coalition-building often has a negative undertone, perceived as inherently designed to block policies. This point, raised in a strategy seminar in Brussels in November 2018, reflects the combative political environment in the EU’s capital. But it also shows that the concept of coalition-building as an enabler of pan-EU policy innovation has not yet developed.

Secondly, overall political orientation is not the primary concern of government bureaucracies when they reach out to one another. ECFR was often quizzed about the seemingly “apolitical” nature of its approach to coalitions. In today’s highly fragmented European political environment, so the argument goes, coalitions are no longer a product of statecraft between national capitals but are essentially driven by ideological and party political considerations – in other words, by politicians aiming to create majority-vote coalitions at the European level. Yet ECFR’s discussions of coalition preferences with decision-makers show that both these versions of “Europe” – the “diplomatic” and “political” ones – continue to co-exist. National interests often remain stable across electoral cycles, while factors such as good neighbourly relations and historical ties continue to play an important role in interactions between countries within the EU’s framework.

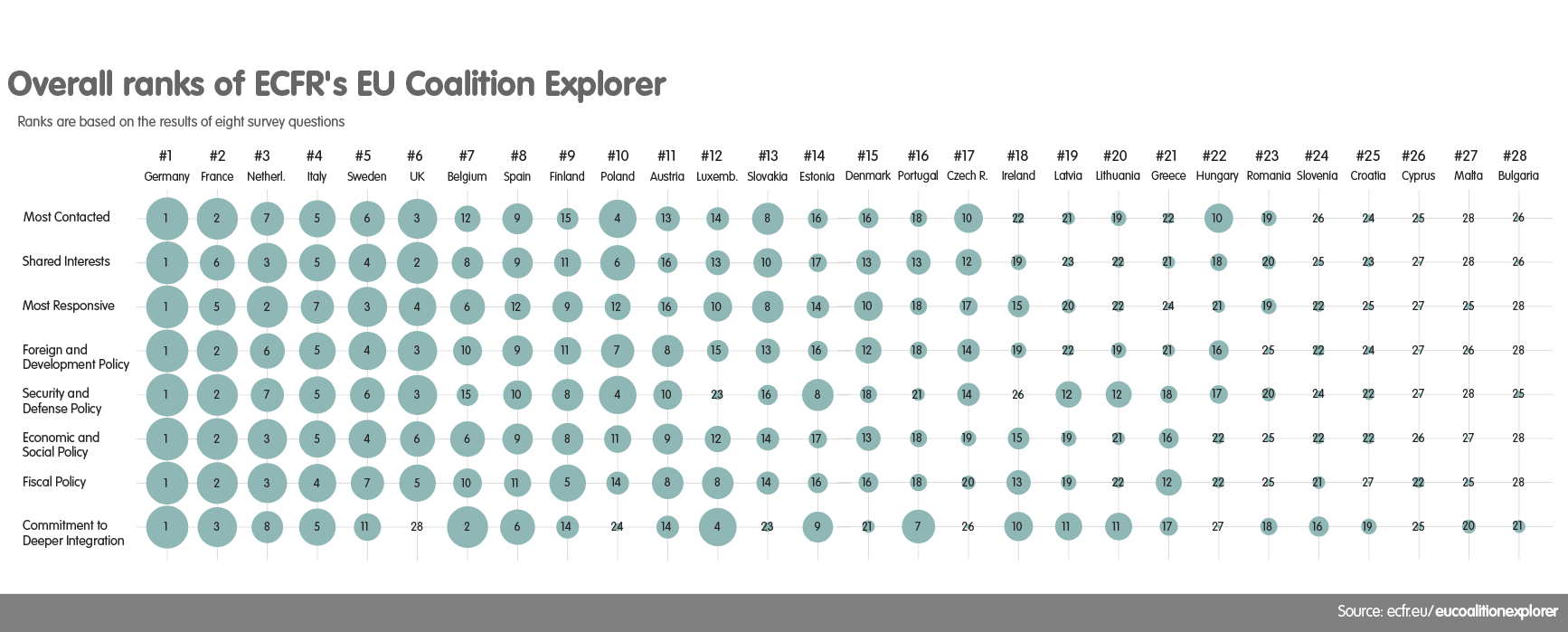

Thirdly, it is not only the biggest member states that can exert influence within the EU. And size is no guarantee of success. Policymakers and policy experts in European capitals often asked ECFR about the importance of a member state’s size and resources. While it does not provide easy answers for countries that aim to build strong coalitions using limited resources, the EU Coalition Explorer demonstrates that any country with ambition can develop its identity as a partner for others within the EU system. It is true that France and Germany are the best-connected EU member states, while Italy, Spain, and Poland are among the seven best-connected. Yet the Netherlands and Sweden rank in fourth place and sixth place respectively in this measure. This may be surprising given that Sweden is outside the eurozone (while lacking the influence of a large country such as Poland), and arguably has few ties to the union’s political core. Moreover, the country only joined the EU in 1995, meaning that it has not been part of a long-standing coalition such as that between the founding members. Thus, as this policy brief shows, there are many policy niches member states can fill.

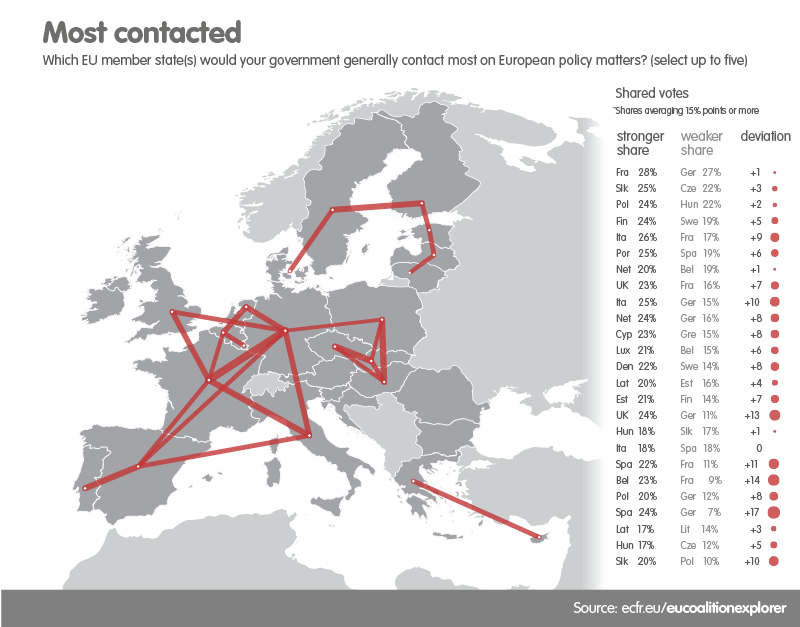

Fourthly, member states cannot rely on their relationships with France and Germany alone. These relationships are hugely important: overall, member states contact Germany more than any other country. And, under President Emmanuel Macron, France has started to catch up in this measure in central and eastern Europe, as well as in Europe’s north. ECFR’s data often reflect other EU countries’ belief that they do not receive the attention they deserve from France and Germany. Yet there are other ways for member states to draw their attention. For example, they can invest in other coalitions. ECFR’s discussions in Prague and Bratislava revealed that the Czech Republic and Slovakia have gained the attention of Germany and France partly due to their membership of the Visegrád group. The two other members of the group, Poland and Hungary, are of particular concern to the rest of the EU due to their governments’ attitudes towards democratic norms and the power of EU institutions. The Netherlands has invested in a range of coalitions. Its role as a key player in a fiscally conservative coalition nicknamed the “New Hanseatic League” has arguably only strengthened not only its resilient alliance with Germany. This is partly because the new grouping has raised interest – and, at times, eyebrows – in Berlin. At the same time, the Netherlands has put a great deal of thought into advancing its relationship with France.

Fifthly, member states can address geographical challenges through intelligent strategy. Countries on the periphery of the EU often struggle to develop their influence in ways that others do not. Finland and its neighbours have discovered that engagement with issues involving the Baltic region can act as a powerful amplifier of their voice at the European level. Struggling to redefine itself as more than an island beyond an island in light of Brexit, Ireland could learn from the Dutch experience with the New Hanseatic League. Equally, Portugal might be well advised to build coalitions outside its traditionally strong and reciprocal alliance with Spain. See the full page in the EU Coalition Explorer (PDF 75.1 MB)

See the full page in the EU Coalition Explorer (PDF 75.1 MB)

Connectivity: the backbone of coalition-building

Along with common political goals and priorities, a long record of cooperation and mutual understanding appears to be key to coalition-building. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the EU Coalition Explorer shows that large member states are in a relatively strong position in these areas. They attract a lot of attention – as is most clearly reflected in ECFR’s measures of the frequency of contact between governments. However, there are major gaps between the six large member states. Four of the six – the UK, Poland, Italy, and Spain – each draw significant attention from only three of the 27 other member states,[1] whereas France is a major point of contact for 13 others, and Germany for 25 of them.

However, much depends on perspective: in the contact preferences of the seven smaller, affluent EU countries (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Sweden), respondents mention France as often as the Netherlands. Meanwhile, the Visegrád countries contact France only as often as they contact Austria, indicating that, for them, France is as relevant as Austria. In both cases, the Affluent Seven and the Visegrád countries contact France significantly less often than Germany. Countries across the EU contact Poland less than any of the other six largest member states, while Spain – the other relatively weak link in this group – benefits from fairly regular contact with France and Italy. As it is set to leave the union, the UK has maintained an unbalanced trilateral relationship with France and Germany, with London contacting Paris and Berlin more often than either reciprocates. And, in contrast to the strong bilateral relationship between France and Germany, the trilateral relationship between the two countries and Poland – the so-called “Weimar Triangle” – exists only in rhetoric.

See the full page in the EU Coalition Explorer (PDF 75.1 MB)

See the full page in the EU Coalition Explorer (PDF 75.1 MB)

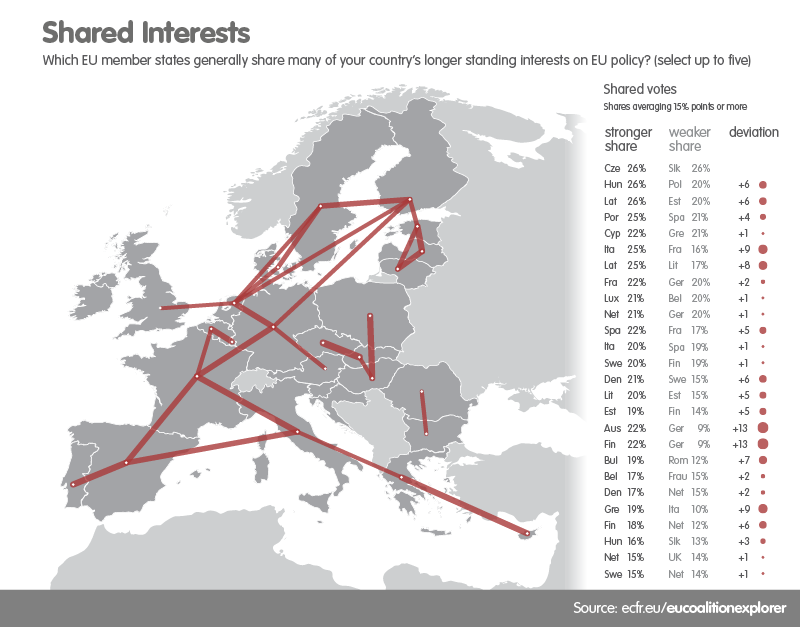

ECFR’s findings on the strength and reciprocity of statements about shared interests reveals further divisions and links. In this, there is a disconnect between central and south-eastern Europe and the west. The weakening of German-Polish shared interests has cut the one link that showed up in the earlier edition of the EU Coalition Explorer, based on ECFR’s 2016 data. Germany and Poland are now disappointed with each other.

The strongest connections in this regard run between east and west, notably between the Visegrád countries and the founding members, except Italy. The Baltic states’ only link to the rest of the EU runs via Scandinavia, the UK’s sole link runs via the Netherlands, and Ireland has no such link at all – which, given Brexit, is a tough reality for the country. Germany is connected to the north of Europe and to France, which is the key link in the map of shared interests due to Paris’s role in the southern triangle with Rome and Madrid, and its outreach to Berlin.

See the full page in the EU Coalition Explorer (PDF 75.1 MB)

See the full page in the EU Coalition Explorer (PDF 75.1 MB)

As discussed above, gaps between states’ perceptions of themselves and the ways others perceive them could easily complicate coalition-building. For example, four of the best-connected member states – Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden – significantly overestimate their influence on EU policymaking. Yet while most EU policymakers and policy experts agree that the Netherlands and Sweden have a relatively weak commitment to deeper European integration, Italian and Spanish policy professionals are among the few to see Italy and Spain as strongly committed to such integration. Thus, overconfidence may prompt Rome and Madrid to take the initiative, or may lead them into frustrating political failures.

Priorities and partners

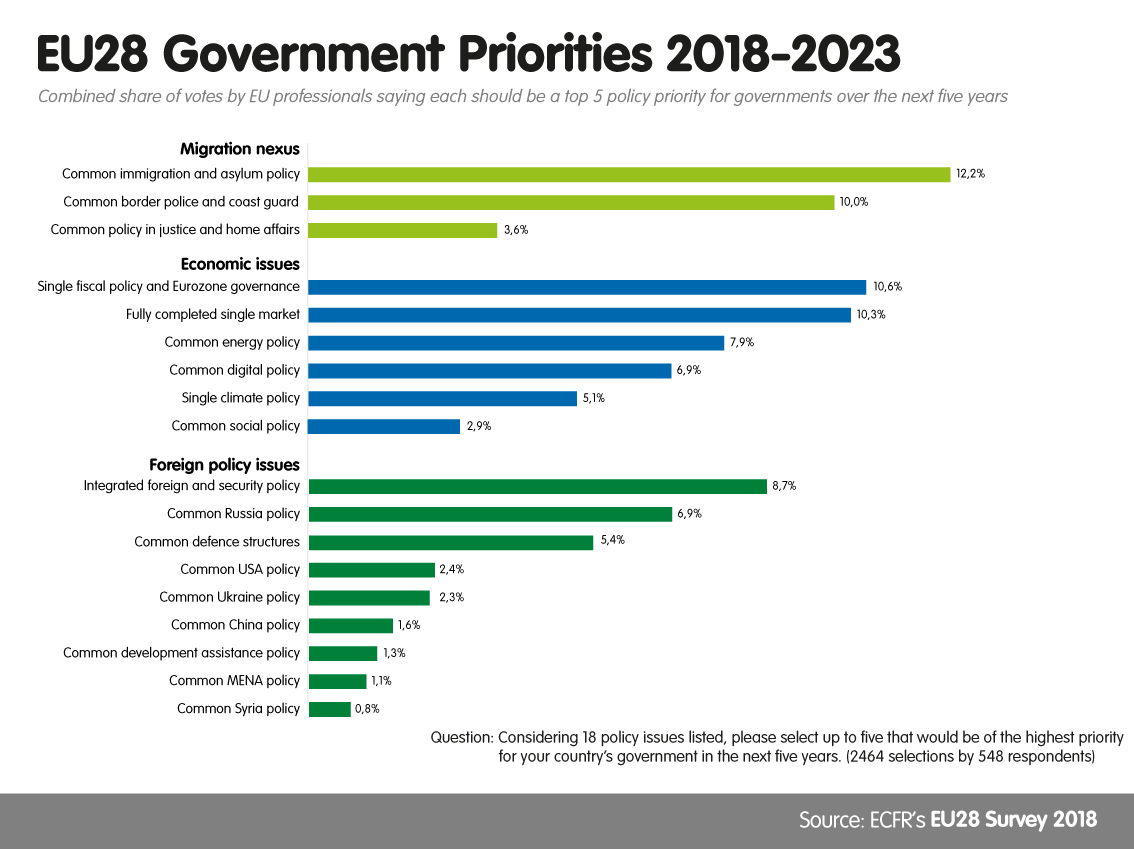

For the first time, ECFR has analysed the policy integration agenda of all 28 member states, with the aim of identifying areas in which they have shared interests. The data show that various groups of member states have a handful of shared interests, including migration, fiscal matters, the single market, and security.

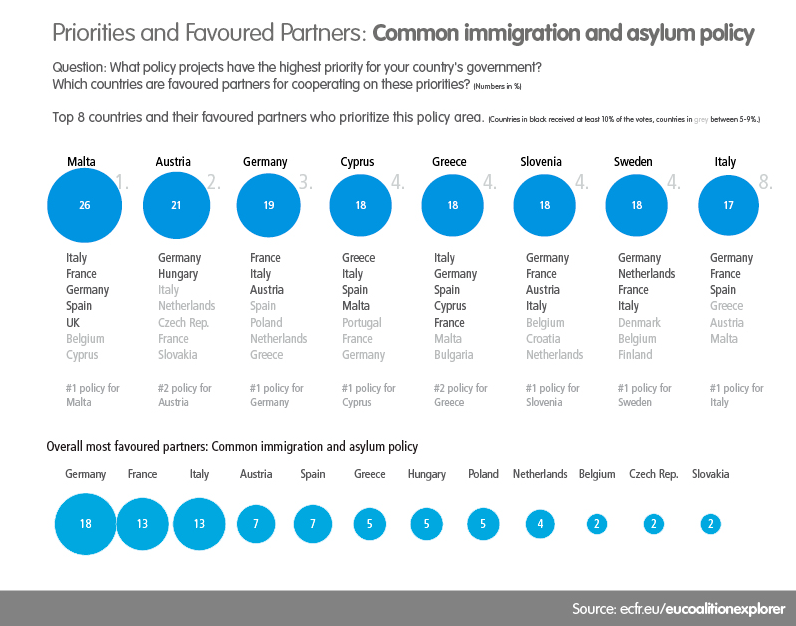

The migration complex

Migration-related issues easily top EU member states’ agendas for the coming years. Of the 18 issues ECFR asked policymakers and policy experts to rank in order of importance, common immigration and asylum policy came first and a common border police and coast guard came fourth. Both areas have a great deal of traction in EU countries on the union’s external border, especially those located on the major migration routes to Europe. According to the EU Coalition Explorer, the core group of member states most concerned about migration comprises France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. These countries are not only highly interested in migration but also most often name one another as key partners in the area.

Austria, Greece, and Hungary also stand out in this context, as member states list them as important partners in migration policy more often than most, albeit in different contexts. The policy debate in Brussels demonstrates that – unlike France, Germany, Italy, and Spain – Austria, Greece, and Hungary have significantly different preferences on migration policy, despite their common ground on the issue. Only France and Germany, with support from Spain, have called for member states to share responsibility for the EU’s migration policy; other large member states either prefer different modes of cooperation or an entirely different approach to the topic.

See the full page in the EU Coalition Explorer (PDF 75.1 MB)

See the full page in the EU Coalition Explorer (PDF 75.1 MB)

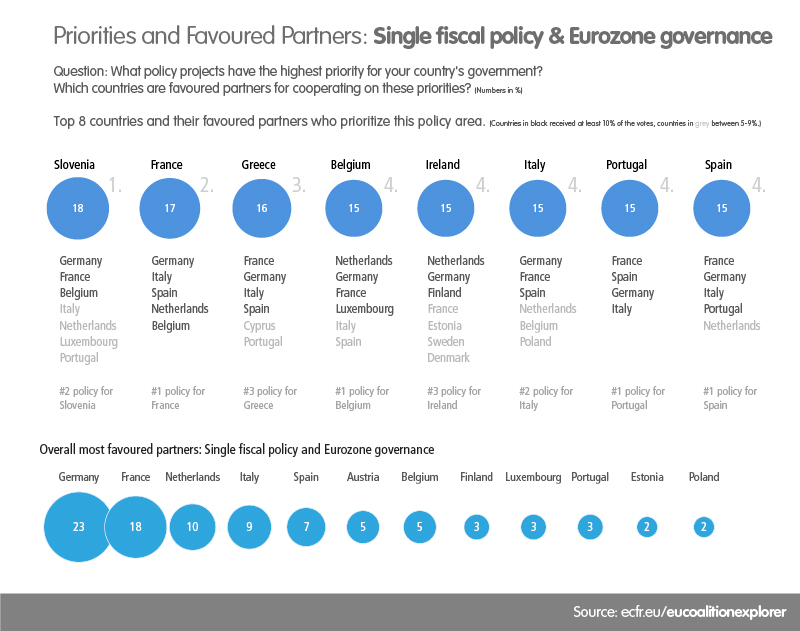

The fiscal cluster: eurozone governance and a common fiscal policy

A common fiscal policy and eurozone governance also rank high on the agenda of policymakers and policy experts across EU member states. Overall, they name this as a priority more often than all but one other issue. The strongest interest in a common fiscal policy and eurozone governance comes primarily from states in western, central, and southern Europe, including Greece, Ireland, and Portugal – all of which received assistance from the EU and the International Monetary Fund during the euro crisis. The preferred partners for states in this cluster are France and Germany, followed by the Netherlands. Many of the countries most focused on a single fiscal policy and eurozone governance often list Italy and Spain among their top four preferred partners. Smaller countries most focused on this area often list Austria, Belgium, Finland, and the Netherlands as their preferred partners. See the full page in the EU Coalition Explorer (PDF 75.1 MB)

See the full page in the EU Coalition Explorer (PDF 75.1 MB)

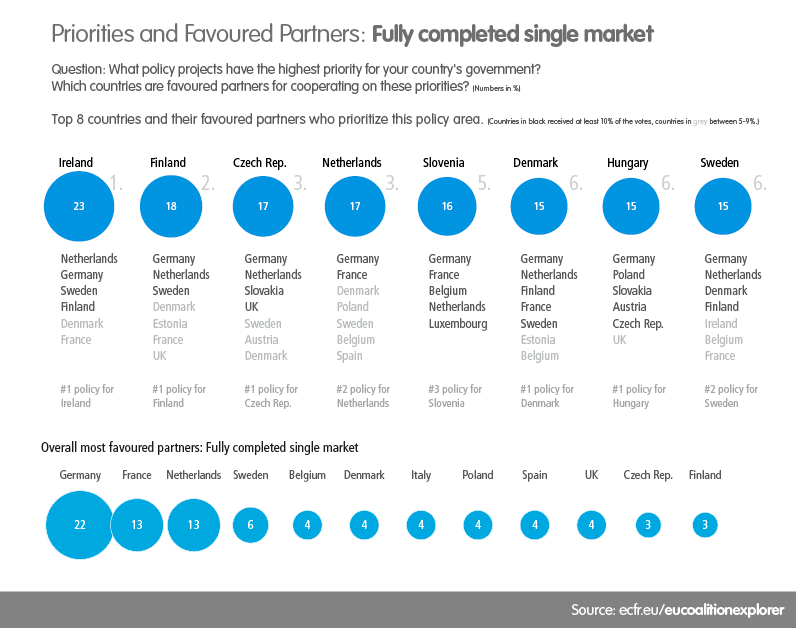

The market cluster: the single market and a common digital policy

Overall, respondents to ECFR’s survey named the completion of the single market as a priority more often than all but two other policy areas. In combination with the issue of a common digital policy (which ranked in seventh place among their priorities), the topic of the single market could create the basis for a coalition primarily composed of north-eastern European countries. The completion of the single market is at the top of the agenda for the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, and Ireland; and it is the second-highest priority for Luxembourg, Portugal, the Netherlands, Slovakia, and Sweden. All these countries also emphasise the importance of a common digital policy. Aside from one another, they most often list Germany and France as preferred partners on these two issues (Portugal and Belgium frequently see other southern EU member states in this role). Only Czech and Polish respondents mention the UK, one of the long-standing advocates of single market policy, as a preferred partner. This reflects the broader, post-Brexit turn away from traditional partnerships with the UK, particularly in northern Europe.

See the full page in the EU Coalition Explorer (PDF 75.1 MB)

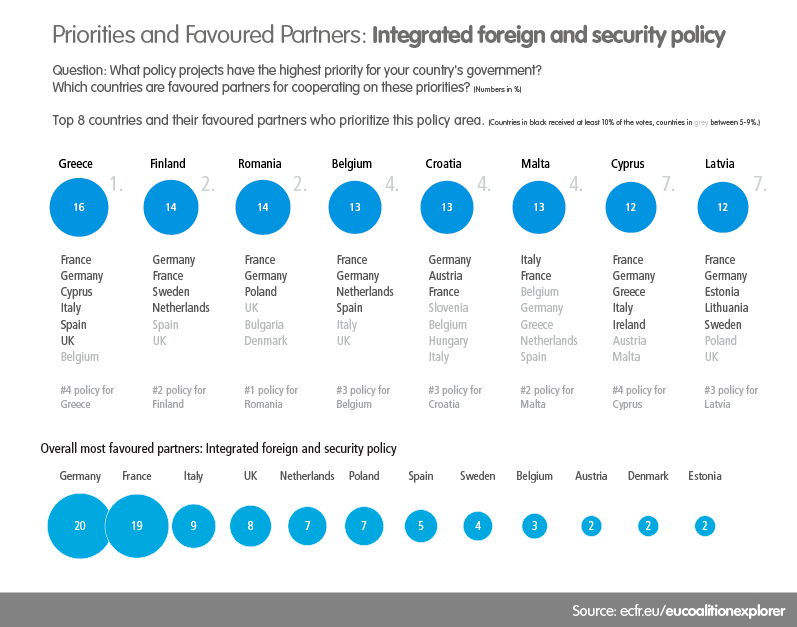

The security cluster: Russia, common defence structures, and an integrated foreign and security policy

Among the 18 policy issues ECFR asked policymakers and policy experts in all EU capitals to rank in order of priority, eight directly involved foreign policy: an integrated foreign and security policy, common defence structures, a common development assistance policy, and common policies vis-à-vis China, Russia, Ukraine, Syria, and the Middle East and North Africa. Member states included only three of these eight areas in their top three priorities. The lowest priority among those that made it into the top three was the issue of common defence structures, which ranked in third place on the priority lists of Romania and Hungary (while appearing lower down on those of all other member states). An integrated foreign and security policy is a shared priority of significantly more countries, although it came in first place only in Romania, and in second place only in Spain, Finland, and Malta. As just Belgium, Croatia, Latvia, and Lithuania listed it in third place, there is little basis for a coherent foreign and security policy coalition.

Russia was the highest-ranking foreign policy issue overall on member states’ priority lists. Among the seven countries that clearly prioritised Russia, five put it on top of their list and the others put it in second place. As such, the Russia issue largely defines the security cluster. The EU countries most concerned about the issue are the Baltic states, Denmark, Poland, Romania, and the UK. Interestingly, most countries that focus on Russia do not also prioritise an integrated foreign and security policy, nor common defence structures. Only Romania lists all three as its highest-priority issues, while only Latvia and Lithuania list just Russia and an integrated foreign and security policy as two of their three highest-priority issues.

The preferred partners of countries within the security cluster are one another – aside from Romania, which none of the others see in this way – as well as France and Germany. This is despite the fact that France and Germany rank the Russia issue in tenth place and fifth place on their priority lists respectively. Also, countries in the cluster have some interest in partnering with Sweden, Finland, and the Netherlands. Finland and Germany see Italy in this way. See the full page in the EU Coalition Explorer (PDF 75.1 MB)

See the full page in the EU Coalition Explorer (PDF 75.1 MB)

Across all issues and capitals, EU policymakers and policy experts tend to list Germany and France as their preferred partners, with Germany the leading preferred partner on two of three issues, and France taking this role on defence, relations with great powers, and regions troubled by conflict. This raises an interesting question: following the UK’s departure from the union, which member state will come third on a list of preferred partners?

In the survey ECFR conducted in spring 2018, the UK remained the third-ranked preferred partner on two issues: a common US policy and a common Syria policy (neither of which the UK prioritised in its relations with the EU). Today, member states generally favour partnerships with Italy, the Netherlands, and Poland over those with the UK. Poland is the third-ranked preferred partner (close behind France) on energy policy and on Russia, and the second-ranked preferred partner (behind Germany) on Ukraine. The Netherlands and France are the second-ranked preferred partners (behind Germany) on the completion of the single market, and the third-ranked preferred partners (behind Germany and France) on fiscal policy and the eurozone, as well as on climate policy.

However, Italy appears to have the greatest potential to establish itself as the third-ranked preferred partner overall. Member states rank Italy in second place among their preferred partners on three issues – a common border police and coast guard, immigration and asylum (tied with France), and the Middle East and North Africa (tied with Germany) – and in third place on social policy, justice and home affairs, an integrated foreign and security policy, common defence structures, and China. However, where Italy ranks in third, there is a gap of 7-11 percentage points between it and the country in second place. Thus, while it appears to be the best-placed potential successor to the UK, Italy still relatively faces some competition in this. The unstable coalition that governs Italy may further weaken the country’s position, even with Brexit.

Strategies for coalition-building in the EU27

Many EU member states build coalitions with a view to vetoing specific policies. Of course, even smaller, isolated countries can unilaterally veto EU policies that require unanimous support. But they require coalitions to do so on policies subject to the majority voting the EU has long used. Implementing a policy with the “double majority” established in the Lisbon Treaty requires the support of at least 16 member states, representing at least 65 percent of the EU’s population. In certain areas, the bar for a qualified majority is even higher: at least 72 percent of member states, representing 65 percent of the population. For procedural matters that must be decided by a majority, the EU only requires more than 50 percent of member states. With the UK’s departure from the EU, these thresholds will need adjustment. The number of member states required to win a majority will be reduced by one, and the population threshold will descend from around 331,750,000 to around 288,255,000.

Thus, qualified majority voting coalitions will remain difficult to build after Brexit, as they will require the support of at least 15 member states, representing more than 288m citizens. Evidently, the remaining five largest EU countries will not constitute a majority, despite being home to nearly 66 percent of the EU27’s population. However, due to their large share of the population, no majority could work against them if they remained united.

Conversely, even a coalition of all post-communist and post-Yugoslav EU members – let alone the oft-discussed Visegrád group by itself – could block a qualified majority vote. However, a coalition of all EU members that are relatively resistant to deeper integration could block majority decisions (based on both majority requirements). With its eight members representing less than ten percent of the population, the New Hanseatic League would not have veto power. But its members could veto a policy if they cooperated with other net contributors to the EU budget, which account for nearly 60 percent of the EU27’s population. Two other high-profile groupings would also be unable to form a majority but could create a blocking minority: the six founding members and the Southern Seven, which account for 53 percent and 44 percent of the EU27’s population respectively.

Therefore, while several groupings could conceivably block decisions if they cooperated with one another, none of them would constitute a qualified majority by itself. Majority-vote coalitions will always need to bridge some gaps in the interests and preferences of member states. Rather than representing a single stable coalition, majority groups will likely be a combination of alliances between member states, bringing together various groups of actors.

The Franco-German tandem: indispensable, but insufficient by itself

As the EU Coalition Explorer shows, Germany remains at the centre of the web of relationships and perceptions that stretches across the EU. It is hard to overestimate Berlin’s influence in almost every other EU capital. Paris is nearly as influential but has less considerably less influence than Berlin in the north and east of the EU (despite a recent series of initiatives to address the problem). Together, France and Germany are essential to the formation of almost any majority vote coalition. The essence of their relationship – their shared will to come to an agreement to ensure the EU continues to make progress – is unique in the union. Without the support of the Franco-German tandem, a project has little chance. For instance, in cooperation with even a smaller member state such as Belgium, France and Germany could prevent the other 24 EU countries from forming an effective qualified majority coalition. However, in a 27-member EU, an initiative led by France and Germany would need the support of at least 13 other countries, representing at least 32 percent of the EU’s population, to win a qualified majority vote. Conversely, not even the support of the “Affluent Seven” (Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and the Nordic countries) and a few more like-minded countries, including a large member state such as Spain, would be sufficient to achieve this by itself.

At a time when (despite their differences) they are on the same side of the key arguments that divide the EU, Berlin and Paris need to form rather broad and, therefore, heterogeneous coalitions to push the EU forward. As they share an interest in winning support from different sources, they must reach out to countries other than their like-minded allies. For Germany, this means maintaining or strengthening its partnerships in the south-west and the east. For France, it means re-engaging with the one strong trilateral relationship the EU Coalition Explorer identifies – that between France, Italy, and Spain. At the same time, Paris needs to continue to improve its standing in the east and north of the EU.

The Affluent Seven: an underestimated coalition

At first glance, there may seem to be little prospect that the Affluent Seven will operate as an effective coalition. Among them, only Luxembourg and Belgium are enthusiastic about deeper European integration. And their approach to membership is shaped far more by cost/benefit calculations than by a commitment to shared sovereignty, while their policies are responsive to relatively strong domestic support for Eurosceptic and nationalist parties. Nonetheless, all these countries have highly developed economies with strong service sectors, as well as a significant interest in preserving the single market and stabilising the EU’s finances and currency, as well as its global trading role. True to their collective name, all of them enjoy a high level of prosperity. They all maintain extensive social security systems. And they have a huge stake in European and international affairs but their voices are rarely heard.

Individually, these countries lack size and influence. Combined, they have a GDP equivalent to that of France, and a population equivalent to that of Italy. And they contribute more to the EU budget than either of these two countries. They are at the geo-economic core of the EU27: together with Germany, France, northern Italy, and north-eastern Spain, they are key to the union’s industrial, technological, and research efforts.

Thus, if they acted together, the Affluent Seven could gain the attention of the Franco-German tandem or any other grouping of member states. Yet, if they are to do so, they will be unable to simply rely on the like-mindedness of the Nordic countries and the Netherlands. They will also have to bridge the differences between member states as different as Belgium and Austria. Equally, they will have to overcome their reluctance to take the initiative, declare their preferences, and seek compromises with states other than their established allies.

If they can achieve all this, the Affluent Seven can shape outcomes within the EU – and can become indispensable to building majority coalitions. Historically, they appear to have had little incentive to work together so long as their interests were sufficiently represented by Germany (either by itself or in cooperation with France and other member states), and so long as the UK was there to resist moves towards deeper integration. Today, with the UK leaving and the EU fragmenting, members of the Affluent Seven should engage in closer cooperation with one another.

If these countries do come together, they should build coalitions that are open to other member states. For instance, they could benefit from working with the Baltic states, Ireland, Portugal, and Slovenia. This would strengthen their legitimacy but would require greater flexibility in finding a compromise.

The New Hanseatic League shows the challenges and potential benefits of such efforts. The eight members of the group primarily work together to veto changes to fiscal policy – an undertaking that, so far, has attracted attention but failed to shape outcomes. Yet there are indications that the Affluent Seven could have more success: several participants in the discussions ECFR conducted across EU capitals expressed a desire to understand how the grouping could help build new coalitions.

The Southern Seven: a renewed focus on coalitions?

In essence, southern EU countries face the same dilemma as the groupings discussed above. They have veto power if they act together, but they lack the numbers to form a majority coalition. Worse, in recent years, the unity of these countries has substantially declined, while some of them have abandoned their traditional advocacy of deeper European integration. At the peak of their influence – in the years of European Free Trade Association enlargement, the transition to monetary union, and the EU’s eastward expansion – the Southern Seven relied on more than just unity to protect their interests. France, Italy, and Spain also played a critical role in this era due to their close bilateral relationships with Germany.

Today, this triangle stands out for the strength of its members’ relationships with one another. But their political goals and strategies have drifted apart – as is particularly evident with France and Italy. Moreover, the close partnership between then-West Germany and Italy on EU integration policy has long since disappeared. The foreign policies of southern EU countries – aside from France – largely focus on the Middle East and North Africa. Southern EU countries primarily maintain their connection to the rest of the EU through their relationships with France and Germany. As a result, when these relationships break down, southern member states can become isolated within the union.

These considerations have prompted countries such as Greece, Portugal, and Spain to seek coalitions beyond the southerners. For Madrid, the primary goal is to strengthen its link with Berlin, which was badly damaged by the fallout of the 2007-2008 financial crisis. Before the current Polish government came to power, Spain also sought to improve its relationship with Poland – not least to control possible competition between them as two of the six largest member states. Similarly, Portugal seems eager to create new ties with north-western EU countries, having long been heavily reliant on its relationships with France and, most importantly, Spain. Meanwhile, Greece has worked to regain credibility in Brussels and western and central European member states rather than relying, as it seemed to do until 2015, on other members of the Southern Seven.

The EU’s east: divisa in partes tres

The EU’s eastern member states are – to apply the famous opening line of Julius Caesar’s commentary on the Gallic wars – a whole divided into three parts. Countries in the region share much of the heritage and burdens of a communist past, and they have encountered similar challenges in the transition to democracy and a market economy. Yet, 15 years after the first big wave of EU enlargement to the east, countries in the region fall into distinct groups. The three Baltic states connect with the rest of the EU via Scandinavia, particularly Finland and Sweden. The ties between the Baltic states, and between them and Scandinavia, are stronger than those between them and the Visegrád group.

The members of the Visegrád group stand out in the EU Coalition Explorer due to their unusually intense focus on one another – which is partly the result of the very strong and balanced relationships between Hungary and Poland, and between the Czech Republic and Slovakia. These four countries show little interest in working with the Baltic states or south-eastern European countries. By 2018, most of their external links involved Germany or, to a lesser extent, the UK or Austria. But, as the EU Coalition Explorer shows, these few links to the west were very unbalanced. According to ECFR’s data, the Polish-German relationship – seemingly the most influential link between eastern and western Europe – weakened considerably on both sides between 2016 and 2018.

The Czech Republic and Slovakia are disappointed with Hungary and Poland, and vice versa, but the strength of the Visegrád group lies in their willingness to find common ground on EU matters. Nonetheless, although they are unified in their reluctance to engage in further European integration – most visibly, on migration policy – Budapest’s and Warsaw’s emphasis on national sovereignty stretches the limits of their capacity to cooperate with one another. As a veto coalition, the Visegrád group is well suited to maintaining an inward focus and a preference for the status quo. Hungary and Poland will find it difficult to reverse European integration without the emergence of more powerful partners – which seems unlikely. Therefore, the Visegrád group currently seems unable to develop beyond its obstructive role to shape broader coalitions on EU policy.

This leaves four countries, which are among the least connected and networked EU member states, at the margins. While Romania and Bulgaria maintain a moderately close bilateral relationship, Croatia and Slovenia are caught up in a territorial dispute with each other. None of the four receives much attention from other countries in the east of the EU or any other geographical or political grouping. These four countries often focus on Italy and France, but their relationships are asymmetric: Italy’s current positions irritate the two post-Yugoslav countries, while France is unresponsive to all four.

The coalition-building challenge

As this paper shows, there are many difficulties in creating majority coalitions in the EU. Agreement and cooperation between France and Germany are necessary for shaping EU policy, but they are insufficient by themselves. It is in both countries’ interests to encourage the emergence of other coalitions and to work with them, as this helps simplify the process of building majority vote coalitions among 27 countries.

A directorate comprising the six largest member states (which, after Brexit, would still need the support of ten other countries) can hardly provide an alternative to this, so long as Italy and Poland pursue an integration agenda very different to that of the others. The spectre of such a directorate was influential in many of the institutional reform debates that occurred before 2007, when the Lisbon Treaty was signed. Yet, in the current environment, the prospect of deep division between member states should be of much greater concern than the formation of such a directorate. The UK is leaving the EU; Poland and Italy seek to weaken Brussels (in somewhat different ways); Spain is struggling with domestic political fragmentation; and France and Germany produce amazingly high numbers of joint papers and declarations but can barely agree on specific initiatives – meaning that they never have to seriously consider which other EU member states to ally with on key policies.

Therefore, the main argument of the 2016 and 2018 editions of the EU Coalition Explorer remains valid: member states have a great deal of untapped potential for coalition-building. But there is no magic number or hidden majority that fulfil this potential alone. Rather, there are various potential alliances – some large and strong, some small and weak – that could facilitate joint action on EU policy. These alliances would require an internal consensus strong enough to provide some flexibility in dealing with other groupings or coalitions.

All this begs two crucial questions: what is the purpose of coalitions? And, if groups of member states engaged more successfully with one another on policy in the coming years, what kind of union would this create? The authors of this paper envision an EU that is built on the political system of the EU rather than a return to bilateral partnerships and alliances between national capitals – which have so often led Europeans into balance of power games and, ultimately, confrontation.

From a strategic perspective, the key issue is how to balance the benefits of forming coalitions with the overall aim of keeping the union together as a whole. One aspect of coalitions that helps preserve the health of the EU is, as discussed in ECFR’s many debates across European capitals, the need to better understand how policy thinking in national capitals translates into decisions in EU institutions. With this first phase of substantive research and analysis having come to an end, the next edition of the EU Coalition Explorer will shed light on this crucial issue.

About the authors

Josef Janning is senior policy fellow at ECFR and head of its Berlin office. He is an expert on European affairs, international relations, and foreign and security policy, with over 30 years of experience in academic institutions, foundations, and public policy think-tanks. He has published widely in books, journals, and magazines.

Almut Möller is senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations and head of its Berlin office. She has published widely on European affairs, foreign and security policy, and Germany‘s role in the EU, and is a frequent commentator in the German and international media. She is a member of the extended board of Women in International Security (WIIS.de) as well as a member of the Strategic Council of the European Policy Centre (EPC) in Brussels.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those within ECFR and beyond who have commented on the EU Coalition Explorer – its methodology and design – and who participated in the EU28 survey. We would also like to thank our colleagues in ECFR’s national offices, ECFR’s associate researchers and council members, and our colleagues in think-tanks across the EU who helped us set up so many opportunities to discuss our findings in European capitals over the past two years.

We are particularly grateful for the support and feedback from the Rethink: Europe project team, Christoph Klavehn and Wiebke Ewering. The EU Coalition Explorer is yet again the result of exceptional teamwork. Special thanks go to Chris Raggett and Adam Harrison for patiently supporting the editing process of this policy brief, as well as the commentaries drafted by ECFR associate researchers across the EU in recent months. We would like to thank them all for helping us to shed light on the variety of stories we can now tell from every corner of the EU.

Thanks also go to information architects and cartographers Dieter Dollacker and Dirk Waldik of Denkbuilder Berlin for their work on the graphic and concept design of the EU Coalition Explorer interactive PDF, which visualises cohesion data in a compelling and unique fashion.

We are deeply grateful to Stiftung Mercator as the partner and funder of the Rethink: Europe project. This partnership has allowed ECFR to dig deep into a key theme of today’s EU, and to deepen our understanding of what keeps Europe’s capitals interested in one another. To discover that EU members retain a strong willingness to engage with one another and find common ground is no small thing in the current environment of European integration.

[1] Contact intensity is measured in percent of the votes cast for a country in response to the question which other government one’s own government would generally contact most. A level of “significant attention” means that the vote share of a country exceeds 15 percent, which means that on average more than half of the respondents have listed this country among their top five contacts.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.