The displacement dilemma: Should Europe help Syrian refugees return home?

Summary

- European governments must decide when and how to protect Syrian refugees who are voluntarily returning home

- They should do so using their remaining levers of influence in Syria, in line with European interests and UNHCR protection parameters.

- European engagement on voluntary refugee returns should be limited, cautious, and conditional.

- Europe must work with Middle Eastern host countries to prevent forced refugee returns.

- European governments must talk to all relevant stakeholders in the Syrian conflict, particularly Russia.

Introduction

After eight years of fighting and destruction resulting in the largest humanitarian and refugee crisis of our time, the government of Bashar al-Assad has all but won Syria’s brutal war. As his regime tightens its grip on Syrian territory and as conditions for refugees in their host countries become increasingly unbearable, European governments now face the challenge of when and how to protect those who fled the conflict and now wish to return home. With donor fatigue increasingly palpable,[1] many EU member states unwilling to expand their resettlement quotas, and states such as Lebanon and Jordan facing difficulties sustaining adequate conditions for their refugee populations, the European Union should adopt a more humanitarian-focused policy that seeks to improve the living conditions of voluntarily returning refugees.

In reality, some Syrian refugees in the region have already begun returning home – be it voluntarily or, in the case of Lebanon, under pressure from their hosts. And while Europe should clearly not actively encourage returns given that overall conditions are not yet safe for them to do so – and should work with regional host countries to prevent forced returns – this paper argues that the potential benefits of limited, cautious, and conditional European engagement on returns are worth the risks. From both a moral and a humanitarian perspective, this paper argues that European states and the EU should seek to proactively use their influence towards this much-needed end – or risk losing that influence.

Europeans rightly worry about granting the Assad regime political legitimacy by working with him to support voluntary returnees; this remains the key political lens through which most external actors on all sides of the conflict’s divide view the returns question. But working to help improve conditions for those refugees who fulfil their desire to return home is also in line with key EU interests in the region: upholding principles such as the universal right to a life of dignity and the right of safe returns for refugees; maintaining stability in host countries that neighbour Syria; and preventing the spread of extremism in and from the region.[2] European countries’ handling of the issue could also have significant implications for their domestic politics, given the growing popularity of xenophobic political parties that are pushing for refugees to return home.

The EU has many reasons not to work with the Assad regime on repatriation, particularly given that the latter’s continued and egregious human rights violations make it still unsafe for many refugees to return home. Yet, as this paper argues, it is worth testing cautious and conditional engagement on this issue, primarily with Russia, as the regime’s main backer that is also concerned with returns, but also with the Assad regime itself, if need be – conducted in coordination with the United Nations and host countries, and only in support of refugees who choose to return of their own accord. This does not need to mean an abandonment of wider political positioning but rather an acknowledgment of the humanitarian imperative of trying to provide an effective means of protecting refugees’ rights on the ground. The paper focuses on how Europe could seek to deploy its leverage to help refugees in Lebanon and Jordan who wish to return home do so in line with the “Comprehensive Protection and Solutions Strategy” devised by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The paper draws on multiple interviews with analysts and officials from the EU, host countries, UNHCR, and international non-governmental organisations.

A gradual rise in refugee returns

Since 2017, Syria has experienced a gradual improvement in its overall security environment – albeit with bouts of violence in some parts of the country. As a consequence, states such as Russia and Lebanon have made ever more frequent calls for Syrian refugees to return home, increasing pressure on them to do so.

According to UNHCR intention surveys, many Syrian refugees themselves want to make the journey. Nonetheless, most do not want to do so under current conditions, as refugees and nearly all external observers agree that Syria remains unsafe for most people who fled the conflict.

Refugees, even those not associated with the opposition, worry about indiscriminate regime retribution. Men who are eligible to serve in the military are particularly worried about the prospect of forced conscription into the Syrian Arab Army, which continues to engage in combat operations. They also express fear of punishment for desertion or draft evasion. Other barriers to return that refugees often cite include a lack of employment opportunities, a shortage of basic services, and the seizure of land and other property.

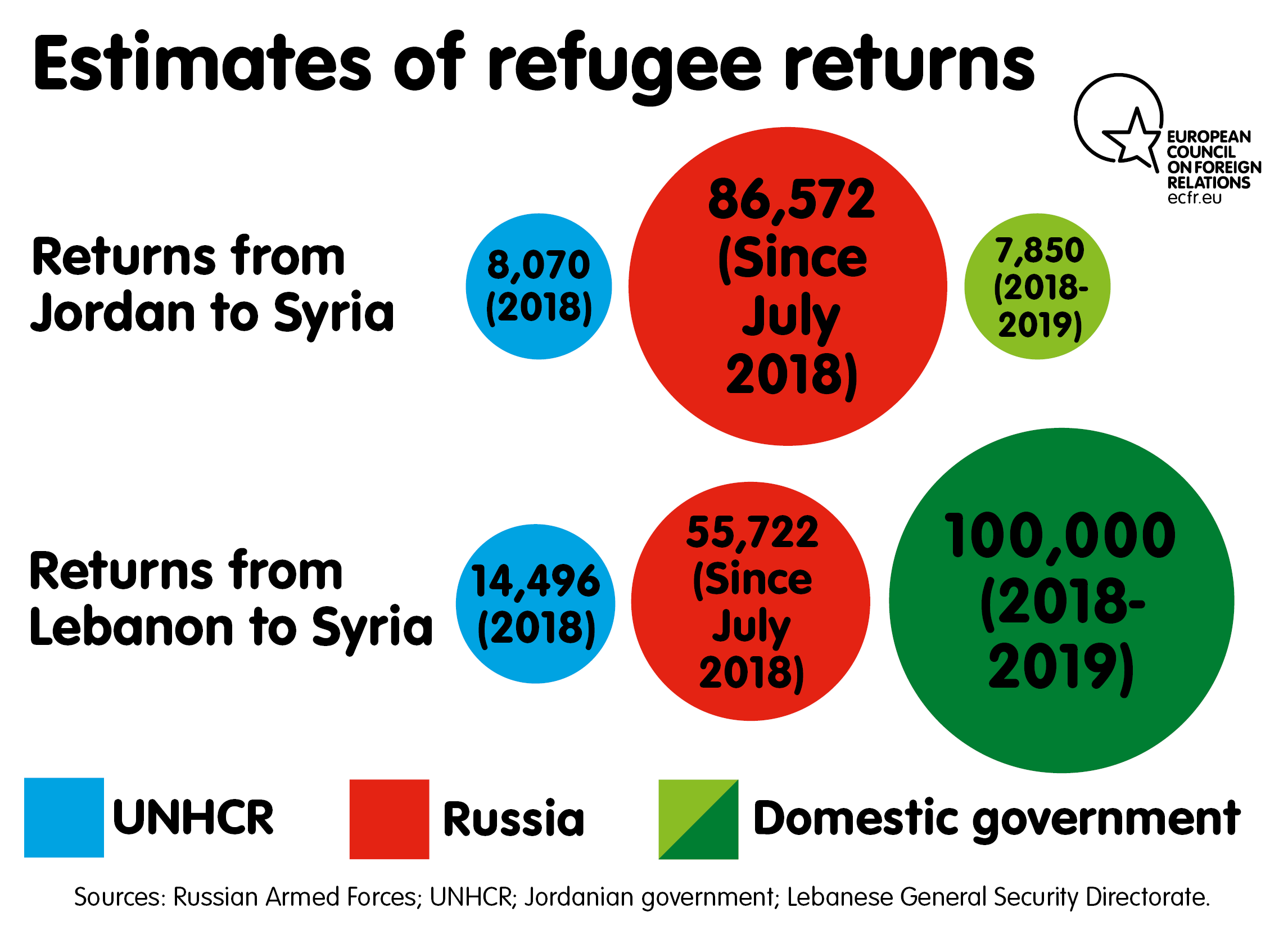

Yet, despite these impediments, refugees have been slowly returning to Syria, either individually or in groups – and, sometimes, aided by their host government or local coordination committees. Reporting on the number of returnees remains uneven, however, with UNHCR and the Jordanian government putting the figure in the tens of thousands,[3] and Russia and the Lebanese General Security Directorate stating that it is more than 100,000. As this paper highlights, returns estimates vary so widely partly because of the conflicting political motivations of actors such as Russia, Lebanon, and Jordan.

While UNHCR remains opposed to encouraging or facilitating large-scale returns because of a lack of appropriate conditions, some returnees have made the journey with the assistance of their host countries in crossing the Syrian border. For example, Lebanon’s General Security Directorate has provided buses to take refugees back to Syria, while the Jordanian government has cooperated with UNHCR in bringing others to the border (albeit only in the very few cases in which the organisation could confirm that refugees were making the journey voluntarily).[4] Non-state actors such as Hezbollah and local Jordanian and Lebanese committees are also participating in small-scale returns of refugees.

It remains difficult to solicit feedback from refugees who have made the journey. Humanitarian organisations in Syria are unable to access many parts of the country, making it nearly impossible to verify conditions on the ground or to maintain contact with returnees. This is part of the reason why UNHCR has been unable to update its overall assessment of refugee returns. As a result, it is hard to predict how the number of refugee returns will change in the coming years – although it seems likely to rise as outbreaks of violent conflict in Syria become less common. Much will depend on conditions on the ground in Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, as well as on the extent of the international community’s engagement with the Syrian regime and provision of assistance to these countries.

Politicisation of the refugee issue

Due to foreign powers’ conflicting objectives in dealing with the Syrian regime, the issue of refugee returns has become highly politicised. Some countries appear to employ relatively high estimates to demonstrate that the war is over and it is safe for refugees to return, while others cite relatively low ones to underscore that the fact that conditions on the ground continue to endanger civilians.

Lebanon’s fine balance

Lebanon’s treatment of displaced Syrians reflects its long and traumatic history with Palestinian refugees during the 1975-1990 Lebanese civil war, as well as Syria’s longstanding dominant political influence over the country. The deal that provided the basis for ending the war – the Taif Agreement, officially known as the Document of National Accord – emphasises the importance of sectarian compromise, allotting specific governments posts to various Lebanese religious communities with the aim of creating a balance of power between them. This fragile equilibrium rests on maintaining the relative sizes of the Sunni, Shia, and Christian communities in Lebanon. Therefore, Lebanon’s Christian and Shia politicians perceive the influx of millions of predominantly Sunni refugees as a potential threat to their authority. The post-war order has simultaneously rested on Syrian dominance and – for those parties that are allied with Damascus and, in some ways, dependent on its support to maintain their political positions – the desire to initiate refugee returns reflects a wider desire to see Lebanon normalise ties with Assad.

In light of these historical and sectarian considerations, it is unsurprising that some Lebanese politicians have found it politically expedient to take a hard line on Syrian refugees, aiming to garner public support. This is especially true given that many Lebanese citizens are looking for a scapegoat for their myriad social and, more importantly, economic problems: Lebanon’s growth rate fell from 8 percent in 2010 to 0.6 percent in 2017, while economic confidence in the country is extremely low. The prospect of an economic collapse has resulted in increased tension between Syrian refugees and their Lebanese hosts.

The desire of some members of the Lebanese government to return a large number of refugees to Syria and to begin the process of normalising relations with Damascus was on full display during the Arab Economic and Social Development Summit held in Beirut in January 2019. In his address to the conference, Lebanese President Michel Aoun – an ally of Hezbollah, which has helped the Assad regime largely defeat Syria’s armed opposition – encouraged the “safe return of displaced Syrians” but maintained that the process should not be linked to a political solution in the war-torn country.

Both Aoun and Hezbollah are pushing for rapprochement with the Syrian regime as a means to enhance their standing and political power in Lebanon. They represent the pro-Assad March 8 Alliance, which recently emerged victorious from a struggle with the March 14 coalition – an organisation that includes Sunni Prime Minister Saad Hariri – over the formation of a new Lebanese government. Foreign Minister Gebran Bassil, the president’s son-in-law and a vocal advocate of normalising Lebanon’s relations with Syria, fought successfully to remove the word “voluntary” from the final summit communiqué – thereby underscoring the need to restore Beirut’s ties with Damascus. Long critical of refugees remaining in Lebanon, Bassil likely feared that the inclusion of the word would provide foreign donors with an excuse to focus their efforts on his country rather than on working with the Assad regime.

In contrast, Hariri – whose father, Rafiq Hariri, resigned as prime minister in 2004 in protest against a Syrian-backed constitutional amendment, only to be assassinated the following year in an attack that many believe was perpetrated by Hezbollah with Syrian backing – is less inclined to normalise relations with the regime or to send refugees back prematurely. He maintains that, while the refugees should eventually return, now is not the right time. However, it remains unclear how long he can withstand pressure from others in his government – not to mention Damascus and Moscow – to change his stance on refugee returns.[5]

In that vein, Hariri accepted Bassil’s demands that pro-March 8 Sunni politician Saleh Gharib serve as minister of the displaced, reflecting a growing sense that Hariri may eventually have to make good with Damascus if he wants to chart a stable path forward for Lebanon. Gharib’s first order of business upon assuming the post was to travel to Damascus to discuss refugee returns. Following his meetings there, Gharib said that Lebanon would work to “secure the return” of refugees to Syria, emphasising that the process must be “safe” without specifying whether it would be voluntary. This was a significant shift in government rhetoric: the previous minister for the displaced, an anti-Assad ally of Hariri’s, demanded that the refugees return voluntarily only when conditions in Syria were safe enough for them to do so en masse. It remains to be seen whether this rhetorical shift will translate into action, given the massive pressures the Lebanese government would face from the international community, particularly European countries, if it attempted to force refugees to make the journey.

A safe haven in Jordan

Jordan has always had a very different approach to Syrian refugees, in that Amman appears to view their presence in its territory through the lens of long-term sustainability. Whereas Syrian refugees in Lebanon have struggled to find jobs and have been forced to live in informal settlements or host communities, those in Jordan have benefited from the construction of government-run camps; relatively organised and equitable employment rights, such as the right to work outside camps and to move between sectors; and, at least for a time, access to services such as subsidised healthcare.

Free of the kind of sectarian and political divides related to Syrians that are apparent in Lebanon, Jordan has not placed refugees under the same type of pressure to return home. This means that the factors pushing refugees to return mainly relate to Jordan’s overall economic conditions, as opposed to public sentiment or government policy. As one Jordanian official stated, “we will never force any refugee to go back. [They must go] only when they feel it is safe.”[6] This is not to say that there is no social pressure at all on Syrian refugees to return or that many Jordanians do not want them to return. Rather, while most Jordanians hope that there will be large-scale repatriation of refugees at some point, they understand that Syrians deserve a safe haven.

Similarly, Jordan’s lack of long-standing historical antagonism with Syria means that there is no widespread resentment of refugees in the country. While two-thirds of Jordanians believe that the refugees’ presence in Jordan has had a negative effect on life in the country, 78 percent of refugees see Jordan as the country that treats refugees best. Furthermore, 88 percent of Syrian refugees believed they had received better treatment in Jordan than they would have in Lebanon or Turkey.

In the early stages of the Syrian conflict, Amman retracted its demand for the Assad regime to cede power, opting instead for a more moderate call for an end to hostilities – albeit while supporting opposition forces in southern Syria in a bid to maintain security on its immediate border. Now that the regime seems sure to survive the war, Jordan appears increasingly willing to repair its relationship with the Syrian regime. The primary motive for this – beyond an acceptance of the facts on the ground – is economic. The Jordanian economy is flagging badly, with an unemployment rate of more than 18 percent. New trade and reconstruction opportunities involving Syria could have enormous benefits for Jordan, which could serve as a source of labour and as a service and a logistical hub. Delegations of Jordanian business groups have already travelled to Damascus to meet with potential reconstruction partners.

Ultimately, Jordanians will gain nothing by keeping their distance from Syria once the war is over and reconstruction has begun. It is likely that these economic incentives will slowly but surely shift the kingdom’s stance on the Syrian regime, leading to the restoration of their diplomatic ties. However, rapprochement with the regime is less likely to increase pressure on Syrian refugees in Jordan than it is in Lebanon – for the reasons discussed above.

Outsized Russian influence

In the crowded field that is the Syrian conflict, Moscow has emerged with greater influence on the future of the country – both internally and within the region – than any other foreign actor. The effects of Russian power are evident in the dialogue over Syrian refugees and their fate: Moscow has drafted a plan to return almost two million of them from host countries in the Middle East and Europe. The plan details the number of air and sea trips necessary to transport returnees, 76 resettlement locations, and even the tonnage of cement required to build housing for them.

On the surface, it may seem that the Russian government has tried to play a constructive role in resolving Syrian refugees’ predicament, with both it and the Assad regime arguing that the conflict is under control and conditions are right for them to return. But the Russian plan has met with deep European scepticism about its intentions and feasibility. So far, European officials have neither substantively engaged with the plan nor presented the Russians with an alternative approach more aligned with European goals and values. This is partly because, while the Russians have made their case for why it is in the interest of European or regional countries to assist in the return of refugees to Syria, most external actors believe that Russia is trying to exploit the question of refugee returns for wider political purposes and do not accept the premise that conditions are safe for refugees. Russia has yet to outline how it would: manage and monitor returns; convince the Assad regime to accept those who want to return; or guarantee refugees’ safety in Syria.

Rather than focusing on the situation on the ground, Russia primarily appears to see refugee returns as a means of forcing international actors to accept that Assad has definitively won the war.[7] It is an inherent political objective. Europeans are unwilling to take this step and do not want to legitimise the behaviour of Moscow and Damascus in the conflict by engaging with them on refugee returns. They are also wary of the fact that Russia appears to be deliberately playing to Middle Eastern and European political divisions by suggesting that conditions are safe to return, in full knowledge that this will exacerbate domestic polarisation. Europe’s reluctance to work with Russia to facilitate refugee returns to Syria has led Moscow to place greater emphasis on persuading Syria’s neighbouring states, particularly Lebanon, to accept Assad’s victory and move to support returns. This, Moscow likely hopes, will compel Europeans to follow suit.

The Assad regime’s double game

At the September 2018 UN General Assembly, Syrian Foreign Minister Walid Muallem publicly invited refugees to return to Syria, while reminding them that they would have to abide by the laws of the Assad regime. Yet the reality is far less welcoming. Fundamentally, despite the fact that its core external backer, Russia, is encouraging returns, Damascus does not appear to want most refugees to return. Regime officials have denied requests to return on unclear or seemingly arbitrary grounds; Syrian officials continue to make threatening statements on refugees that could deter them from making the journey; and there is both practical and anecdotal evidence of Syrians being disappeared, killed, or forcibly conscripted upon their return.

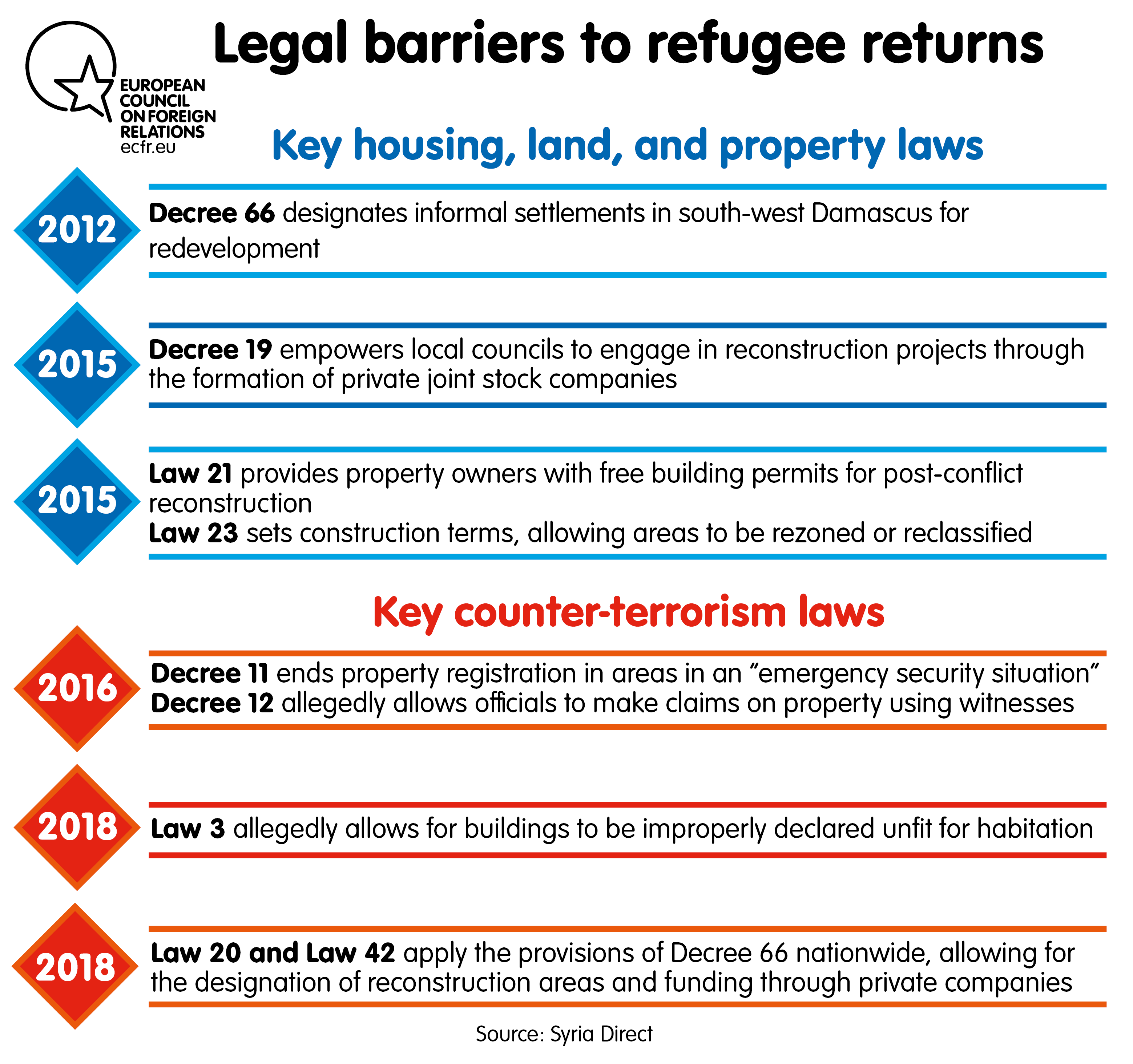

In other words, through a combination of repressive security measures, as well as housing, land, property, and counter-terrorism laws, the Syrian regime has made it impossible for many refugees to return.

The Syrian regime has used several tools at its disposal to disincentivise the return of refugees. They are: international negotiations such as those in Astana and Sochi, where the regime has not engaged with formal attempts to promote refugee returns; legal measures such as those on property rights; economic disincentives, such as the destruction and redistricting of communities around Damascus to exclude potential returnees; and fear and defamation, such as that from propaganda in Syria designed to vilify those who fled and mark them as cowards.

The regime likely fears that returnees will be more sympathetic to the opposition and could become a source of domestic dissent. As such, by ensuring that regime-controlled areas are inhabited only by his supporters, Assad is creating a de facto buffer zone against future conflict and decreasing the need to address the root causes that led to the uprising in 2011. This is likely accompanied by a simple economic rationale that has important political ramifications: fewer returnees mean less pressure on a broken and overstretched government to meet the needs of the population.

In examining these realities, it becomes quite clear that the Assad regime is playing a double game. It is doing a minimal amount to maintain the illusion that all refugees are welcome back and demonstrating that the war is over through an emphasis on improved conditions and a nominal openness to returns, in the hope that this will encourage diplomatic normalisation and reconstruction. At the same time, however, it is actively blocking returns in a manner that is likely driven by concerns over how they will have an impact on the regime’s delicate power balance. Europeans should continue to forcefully call out this double game in conversations on returns with Russia or the regime.

The EU’s dilemma

Europe’s approach to dealing with Syrian refugees should have several objectives:

- Protecting the human rights and dignity of displaced persons. This includes providing a safe environment for returnees, who can help create an inclusive governance system and political climate.

- Promoting regional stability by continuing to support refugees in their host communities and mitigating hostility towards them, particularly in Lebanon.

- Ensuring that the benefits of stabilisation and humanitarian assistance in Syria extend to those who need it.

- Preventing Russia and Iran from becoming the only relevant players in the region, now that the United States appears to be drastically reducing its military and diplomatic role in Syria.

EU High Representative Federica Mogherini has underscored the union’s commitment to not prematurely encouraging refugee returns and creating “the conditions for a safe and dignified return of all Syrians to their land”.[8] Given the risks related to regime positioning towards returns outlined above, the EU insists that this has not been achieved. The EU and its member states look to UNHCR to determine when such conditions have been established, based on progress on the 22 protection thresholds and parameters the body deems necessary to facilitate large-scale refugee returns. The agency determines these thresholds to be necessary for a sustainable returns process. They include:

- A significant and durable reduction in hostilities.

- Full acceptance by the regime of all forms of identification, certification, and other legal documents obtained by Syrians before, during, and after the conflict (including birth certificates, school diplomas, marriage documentation, and housing deeds).

- Regime guarantees of protection against discrimination, harassment, persecution, and detention for returning refugees.

- The freedom to return to the place of origin.

- Full amnesty for refugees, including those who evaded military service.

- Unrestricted access for UNHCR in Syria, to allow the agency to monitor returns and verify regime compliance with its protection thresholds.

The EU remains staunchly focused on these protection thresholds and parameters. In this context, the EU has refused to condone or work towards implementing the proposed Russian plan on refugee returns, which provides no guarantees for any of these protections.

Meanwhile, although European sanctions relief and reconstruction support are clearly tied to progress on a political process to end the Syrian conflict, the return of refugees is not.[9] The EU rejects the concept of trading reconstruction funds or the normalisation of relations with the Assad regime for refugee returns. This would not only violate European principles but would also fail to acknowledge that the reality on the ground prevents the safe and dignified return of refugees that the Syrian regime has deemed undesirable.

But this now begs the question: if the EU lacks a plan to counter that of the Russians, as well as the willingness to engage in direct negotiations with the Assad regime on UNHCR’s protection thresholds and parameters, can and should it play a role in helping improve conditions for refugees who are now voluntarily returning home?

Here, there are several reasons to think that the EU’s position is too rigid. Firstly, Assad’s military ascendancy is increasingly difficult to ignore, and it is clear that he will be the key stakeholder in Syria’s future; indeed, several Arab states, led by the United Arab Emirates (which recently reopened its embassy in Damascus) are now looking to normalise their relations with his regime, partly as a way to counter Iranian and Turkish regional influence. Secondly, a growing number of refugees will risk returning to Syria as conditions in host countries deteriorate, or simply because their original reasons for leaving – such as regime attacks or the presence of the Islamic State group (ISIS) – no longer apply.[10] This is the unfolding reality on the ground. Europeans need to ask themselves if there is not now both a moral and humanitarian imperative to do everything possible to improve the conditions awaiting these refugees as they return home. Finally, some members of the EU, such as Poland and Italy, already appear to be willing to re-engage with Assad to achieve self-interested national or party-political goals (such as moving refugees elsewhere or winning reconstruction contracts). There is a significant risk that a failure to get ahead of this shift in a principled fashion will result in the complete collapse of European consensus on this issue.[11]

European leverage in Syria

Multiple interviews with experts and officials from the EU, host countries, UNHCR, and non-governmental organisations suggest that there is space for Europe to – as one EU official put it – “fine-tune” its strategy to reflect current realities, cautiously engaging in a way that helps shape the future of three critical states: Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria. Most analysts and officials interviewed for this paper supported a shift in the EU’s thinking on refugee returns and suggested that Europeans should make use of their leverage before it disappears. “We cannot pretend that we can have strategic patience, keep Syria isolated, and that it won’t have a negative impact on Jordan and Lebanon,” stated one EU official.

The dilemma the EU currently faces is how to avoid sacrificing its values of human rights and dignity while achieving the important objective of improving the conditions that await refugees upon their return to Syria. Given current conditions, it seems inevitable that this will now necessitate some degree of re-engagement with the Assad regime, even if the prime focus of European efforts will continue to be Russia. While there is no doubt that even limited engagement will provide Assad with a degree of political legitimacy, building a common strategic approach that ties any European shift to core, defined conditions may now represent the best means of protecting refugees. Failure to explore a different approach at a time when refugees are facing more pressure than ever does them a great disservice. It also risks minimising the EU’s potential role in improving conditions on the ground and mitigating future conflict in the region. For instance, Europe could be excluded from bilateral agreements between regional states in a fashion that marginalises its ability to secure guarantees.

The EU’s core choice, then, is between sitting tight in defence of European values and principles or actively using what leverage it has to at least try and set the terms of its involvement in voluntary returns.

As part of this proposed approach, it is critical to recognise the EU’s levers of influence over the Syrian regime and, by extension, Russia. While limited and certainly not sufficient to induce the transformational political change Europeans have long desired, these levers might still, if carefully calibrated, play a role in improving the conditions within the emerging post-war Assad order, particularly for returning refugees. They are:

- Financial assistance, including reconstruction funds.

- Diplomatic recognition of the Assad regime, including the reopening and staffing of embassies in Damascus.

- The power to levy additional sanctions against the regime.

Russia has long called on Europeans to deploy all of these cards in the regime’s favour in its long pursuit of European legitimisation of Assad’s victory, highlighting the fact that these levers do provide influence. Likewise, Assad has recently demonstrated his desire for international recognition – calling for European embassies to reopen in Damascus – and appears increasingly driven by his aim to acquire international legitimacy, in the hope that it might result in sanctions relief, given that the measures are imposing a heavy financial price on his regime.

A new approach to refugee returns

The EU, speaking with one voice, should now think about how to utilise its political position and its levers of influence vis-à-vis the Syrian regime and its backers, namely Russia, to protect refugees who voluntarily return. This approach should remain tied to UNHCR’s protection thresholds and parameters, and the fact that the agency’s decision to move to a phase where it can facilitate large-scale returns may not be uniform across Syria. As such, to test whether Assad does enough to justify wider engagement, this approach could be limited to a specific geographic zone.

To begin with, the EU should continue to clearly reiterate that conditions in Syria remain unfavourable for refugees and, as such, it will not do anything to actively encourage them to return. The EU should maintain both public and private pressure on the Assad regime and its international backers to implement UNHCR’s 22 protection thresholds and parameters. Any shift in this position should be contingent on clear and demonstrable improvements in the situation on the ground that allow for safe and sustainable refugee returns.

Secondly, the EU should maintain its strong political and financial support for the governments of Lebanon and Jordan, as well as for UNHCR. It should work to prevent donor fatigue, which could result in decreased financial assistance to these actors and, as a result, force refugees to return. This should include a commitment to filling the funding gap in the international crisis response plans for Lebanon and Jordan. As one UNHCR official stated, “what I would hope for from the EU is that they understand the refugee return question will last for decades in this region. Support to host countries will have to continue or you take a risk that onward migration will continue or rise.”[12] In other words, Europeans must step up their efforts to prevent these countries from forcibly returning Syrians to an unsafe environment. Such efforts are also critical to ensuring that neither Lebanon nor Jordan suffers from further instability due to a lack of sufficient resources.

Thirdly, Europeans should now cautiously engage with Russia and, to a lesser extent, the Assad regime on the refugee issue. The EU must acknowledge the emerging reality on the ground by talking to all relevant stakeholders in the Syrian conflict – in line with what one EU official referred to as the “principles of humanitarian engagement”.[13] As distasteful as it is, Assad has more power than any other actor to meet UNHCR’s 22 protection thresholds and parameters. Therefore, he needs to be convinced, or coerced, to play a constructive role.

So far, Assad has been unwilling to partner with Europe and has indicated that he does not want many Syrian refugees to return. But, with millions of refugees stuck in increasingly unliveable conditions, it is incumbent upon the EU and its member states to test – out of both their principled obligations to refugees and in pursuit of their domestic interests – ways to cooperate with Russia and the Assad regime. While many Europeans may shudder at the prospect of entanglement with the Assad regime, the possibility that this will improve conditions on the ground for refugees makes it a course of action worth considering.

Nonetheless, as the Assad regime currently remains unlikely to engage with it in good faith – and given Europeans’ understandable desire to maintain their distance from Damascus – the union should primarily focus on Moscow. The EU should take advantage of the Kremlin’s desire for European engagement on refugee returns – which stems from its quest for international legitimisation of Russian gains in Syria, as well as for a degree of external support in managing post-conflict reconstruction.

To increase the likelihood that Russia will participate in good faith, the EU should take the Russian refugee returns plan as the starting point for a conversation with Moscow on the issue. This does not mean fully accepting the Russian proposal but taking it into account and responding with a viable counter-proposal that covers all necessary stakeholders, including the governments of Lebanon and Jordan, while laying out the core conditions needed to secure any form of European involvement. Several analysts and officials interviewed for this paper expressed regret that the EU has not given more attention to the Russian plan. “We should have sat down and engaged with the Russian proposal,” stated one EU official in February 2019. While it does not address barriers to refugee returns nor explain how Russia would hold the regime to account, the plan could serve as a starting point for negotiations between either the EU and Russia, or between the EU, refugee host countries, Russia, and Syria.

Towards this end, the EU and its member states should clearly outline to Moscow a proposal for supporting voluntary refugee returns that centres on the tangible implementation of UNCHR’s 22 protection thresholds and parameters, recognising that thresholds directly related to the regime’s survival may be hard to implement in the short term; key among these provisions should be the security of returning refugees. The provisions must also include unhindered access to Syrian territory for UNHCR and international non-governmental organisations, which would enable them to effectively monitor returns and receive feedback from refugees, as well as to ensure the regime upholds its commitments not to arbitrarily detain or otherwise persecute returnees. If Russia truly wants to secure any European participation in facilitating refugee returns it will need to demonstrate a far greater commitment and ability to deploy its own levers of influence over the regime to meet these conditions. Moscow will also need to play the key guarantor role in this process, given its relationship with the regime and its presence on the ground.

The substantial variations in conditions across Syria would have a significant effect on progress in implementing the UNHCR thresholds and parameters in the country. And there is a risk that the Assad regime will abandon its commitments once the initial implementation phase had passed. Therefore, the EU could take a more piecemeal approach based on UNHCR’s acknowledgement that Phase Two (in which conditions are ripe for facilitating large-scale returns) can be reached in some areas, while others are stuck in Phase One (the current phase, in which there are no large-scale facilitated refugee returns). The EU’s plan could focus on the following steps:

- In consultation with UNHCR and the governments of Lebanon and Jordan, the EU agrees with Russia on a mechanism to identify a specific area in Syria in which to test the regime’s willingness to make progress on the 22 protection thresholds and parameters, thereby providing those who wish to return with an opportunity to do so.

- Working in conjunction with host countries, UNHCR identifies refugees from the chosen area who have already indicated an intention to voluntarily return, or who have already returned. As part of this, there must be no incentivisation of non-voluntary returns.

- Under an agreement between the EU, Russia, Syria, and host countries, UNHCR accesses the selected area to create and implement a plan for ensuring that protection thresholds and parameters are met.

- A monitoring body comprising EU and Russian representatives assesses the situation over a set period, determining whether sufficient progress has been made. UNHCR would be the technical arbiter of this process, to ensure that it remains free of political bias and concentrates on improving conditions for returnees.

If there is sustained progress and Russia shows an ability to act as an impartial guarantor, Europeans must be in turn willing to provide some limited concessions to the Assad regime and Moscow. This could include re-establishing a low-level diplomatic presence in Damascus, which would provide a degree of international legitimacy to the regime and Moscow (and could help with oversight of verification and independent implementation mechanisms). Europeans should also commit to steps such as funding stabilisation support in the test area – a channel of assistance that should be distinct from broader reconstruction support, which should continue to be tied to a meaningful peace process. Even as Europeans engage on this track, they should make clear that it will remain limited and that broader Russian and regime goals of normalisation and economic support will remain firmly tied to developments in the UN-led political process.

Just as importantly, Europeans will need to show a firm willingness to walk away if Moscow and Damascus show any signs of reneging on agreed commitments or do not transparently implement the agreed conditions. At a time when Europeans’ policy of non-engagement with the regime appears to be fraying, this new approach – which lays out the terms for a more pragmatic turn, but also makes clear that it is dependent on non-negotiable conditions on the ground – could create unified European support for a sustainable plan that aims to meet the key concerns of all sides.

In parallel, the EU could work with UNHCR, the International Organization for Migration, and the governments of Lebanon and Jordan to assist refugees who want to return to Syria and can safely do so but are unable to make the journey for non-security reasons. This could involve funding refugees’ transport home, directly arranging a means of transport, and establishing a fund that refugees could access after they return (which would provide enough for, say, three months of rent and food). These measures would help refugees rebuild their lives. While being careful not to push Syrians to return prematurely, the EU should acknowledge that withholding assistance is, in a sense, depriving those who wish to return of their right to do so.

Caught up in a strategic competition

Refugee returns are only one component of the broad, complicated strategic competition playing out in and around Syria. To create a truly sustainable solution to refugees’ plight, all international actors involved in the country’s conflict will need to work together to address the underlying political reasons why refugees fled their homes.

At the same time, the EU should not tie any progress on the question of refugee returns to a still-distant equitable political settlement. The reality is that many refugees are under unbearable pressure in their host countries, while others are simply tired of living in a foreign land and wish to now go home – sometimes because, in their home regions, it is relatively safe to do so. Rather than remaining on the defensive, the EU should proactively use its leverage to try and improve conditions on the ground for returning Syrians who have already suffered too much. The Russian refugee returns plan provides a way to start a conversation about the steps the Assad regime and Moscow would need to take in exchange for any EU involvement. Testing confidence-building measures to help refugees returning voluntarily to a specific area of Syria could be a positive step in this effort.

The concerns voiced by many political analysts, human rights activists, and EU officials that working with the regime would simply help Assad claim victory – and provide him with leverage that he might not otherwise have – are valid and should continue to be debated. However, this does not mean that Europeans must wait for what one EU official called a “100 percent clean solution”[14] that might never materialise. In resolving its dilemma, the EU will need to set strict conditions for its involvement in voluntary returns, ensuring that any assistance it provides in Syria is in line with the implementation of the UNHCR protection thresholds and parameters necessary for these refugees to return. While the regime may never change certain forms of its behaviour, it may be willing to change some. And without European willingness to try a different, more targeted approach, far fewer refugees will have a chance at a better life.

About the author

Jasmine El-Gamal is a visiting fellow with the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations. During 2008-2015, El-Gamal served as a Middle East adviser at the United States Department of Defense, where she handled the Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria portfolios. During her tenure, she covered issues related to the Arab Spring, ISIS, and the Syrian conflict’s regional spillover, among others. She also served as the acting chief of staff for the deputy assistant secretary of defence for Middle East policy, and as the special assistant for national security affairs to three undersecretaries of defence for policy. El-Gamal received her MS in foreign service from Georgetown University in Washington, where she focused on international security and conflict management.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Julien-Barnes Dacey and Chloe Teevan from ECFR’s Middle East and North Africa programme, as well as Jeremy Shapiro, for their support and comments on drafts of the paper. The author would also like to extend thanks to Chris Ragett and Adam Harrison for editing the paper and creating the graphics, and to Leo Hochberg for his invaluable assistance with all aspects of the paper. Finally, the author is deeply grateful to all those who so generously volunteered their time and candid insights on such a difficult topic.

Footnotes

[1] Interviews with UNHCR and host government officials.

[2] This is not to imply that refugees are inherently at risk of radicalisation, but that conditions conducive to radicalisation – such as feelings of exclusion, lack of employment opportunities, and political grievances – are apparent in many countries that host refugees and asylum seekers (including European states in which right-wing, anti-refugee radicalisation is on the rise).

[3] Interview with a Jordanian official, January 2019.

[4] Interview with a UNHCR official, January 2019.

[5] Interview with a Lebanese head of a non-governmental organisation, February 2019.

[6] Interview with a Jordanian official, January 2019.

[7] Interview with a Russian official.

[8] Briefing from a senior EU official, February 2019.

[9] Interview with a German official, January 2019.

[10] Interview with a UNHCR official, who said in January 2019 that: “pressure is coming from refugees, actually. Refugees started to ask us when they can return again, just before Eid, at the end of August 2018. The desire to go back grew, and we even had sit-ins organised by refugees.”

[11] Interview with an EU official, January 2019

[12] Interview with a UNHCR official, January 2019.

[13] Interview with a European Commission Humanitarian Aid Office (ECHO) official, January 2019.

[14] Interview with an ECHO official.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.