The big engine that might: How France and Germany can build a geopolitical Europe

Summary

- The covid-19 crisis and the resulting economic recession have made many foreign policy challenges more acute, even as policymakers on the EU level devote much of their attention to internal issues.

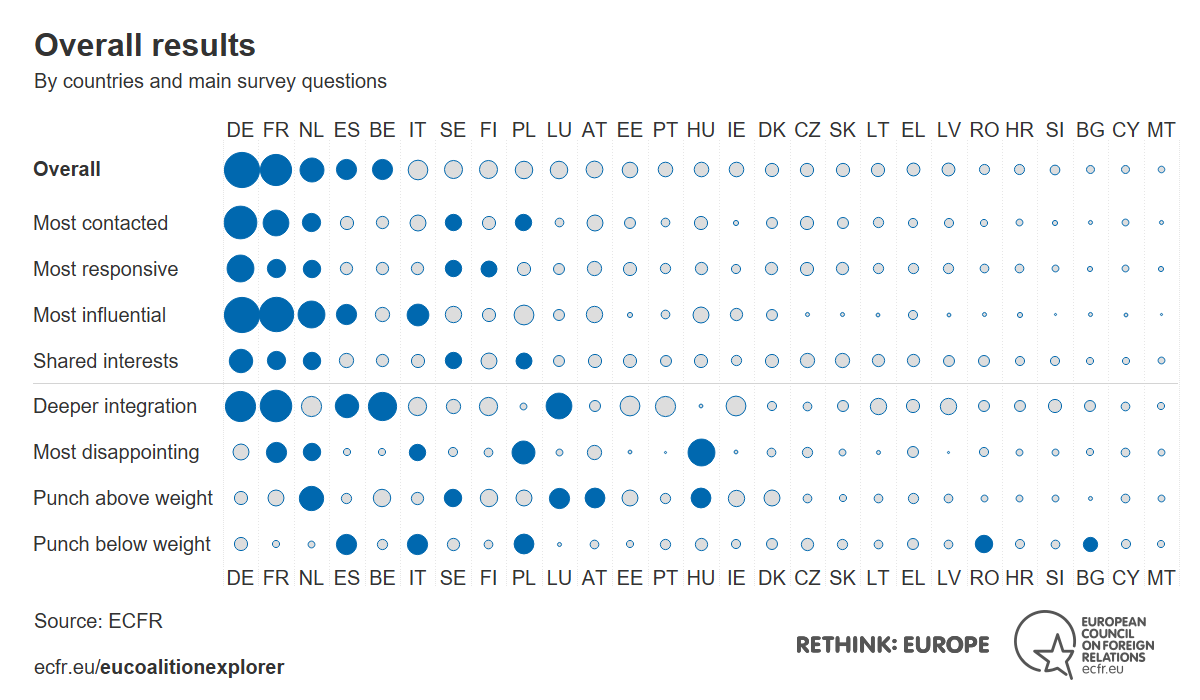

- ECFR’s Coalition Explorer survey of European policymakers and experts reveals the importance of Germany and France within the EU, and the impact they can have when they cooperate with each other.

- The survey shows that EU member states are still geopolitical navel-gazers that must change their mindset if they are to establish a strong common foreign policy.

- France and Germany should use the momentum they created through their agreement on the recovery fund to give the EU a stronger geopolitical voice.

- Together, they have all they need: connections to the south and the east, as well as ambition and pragmatism.

- Paris should try more actively and sensitively to work with its partners who are critical of French foreign policy initiatives.

- Berlin should be more open and flexible in formulating foreign and security policy with smaller groups of member states.

Introduction

When French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel announced they would support a €500 billion EU bond to help with Europe’s economic recovery, it was not quite François Mitterrand and Helmut Kohl holding hands in Verdun. Due to the covid-19 pandemic, the two leaders could not meet in person. Pictures of their matter-of-fact video press conference are unlikely to be found in history books of the future. But the Franco-German agreement they reached on 19 May 2020 was nothing short of historic, as Germany abandoned its categorical refusal to accept EU-wide borrowing. The joint Macron-Merkel statement, as mundane as it may have first looked, was a bold initiative. It served as a reminder of how – when they work together and put themselves at the centre of Europe – France and Germany can shift the debate and, potentially, catalyse agreement between other EU member states.

After several years during which the Franco-German engine was running on empty, this initiative on an internal EU matter was celebrated by many. And it raised an important question: could France and Germany take an equally ambitious and forward-looking lead on foreign policy?

While, on the EU level, policymakers are currently devoting much of their attention to internal issues – especially the recovery fund and the Multiannual Financial Framework – the covid-19 crisis and the resulting economic recession have made many foreign policy challenges more acute. In Europe, China has been extremely active in its mask diplomacy and somewhat maladroit in its attempts at disinformation. The Trump administration’s Europe policy is concerning and divisive. European advances on common defence are stalling. If the European Union wants to be a player, not a plaything, on the international stage, it needs to step up on foreign policy.

On 1 July, Germany took on the presidency of the Council of the EU. Some observers have labelled it as the most important presidency in the EU’s history, a make-or-break moment. The internal policy challenges are clear, but it remains to be seen to what extent foreign policy will find a place on a crowded agenda. This policy brief draws on the results of the third edition of the European Council on Foreign Relations’ Coalition Explorer – a survey of policy experts and government officials across the EU27 – to analyse the Franco-German engine’s potential to cooperate and lead the EU on foreign policy. The first part of the paper discusses Germany’s and France’s respective roles in the EU – covering the extent to which other member states see them as leaders, as well as the state of the Franco-German working relationship. The second part focuses on the EU foreign policy ambitions revealed by the survey. It explores whether Germany and France can use their individual and combined clout to bring greater cohesion to EU foreign and security policy. And it maps member states’ views on the United States, China, Russia, and defence, while discussing areas in which there is a need for a common EU position, and in which small coalitions of states could work together. The final section of the paper analyses the coalitions that might be best suited to dealing with various aspects of foreign policy, and shows how Germany – together with France – can use the German Council presidency to build such coalitions.

The Coalition Explorer’s data

The Coalition Explorer is ECFR’s flagship survey of European foreign policy experts and policymakers. It analyses the results of the biannual survey ECFR conducts in the EU27. The latest edition of the survey, conducted between 11 March and 28 April 2020, used an anonymous online questionnaire in which every question was mandatory. ECFR sent invitations to complete the questionnaire by email to foreign ministries, government and parliament offices, think-tanks, research institutions, journalists, and other organisations that work on European affairs. The 2020 edition is based on the expert opinions of 845 respondents. For each EU member state, between 15 and 51 respondents answered the questions.

For the first time, the Coalition Explorer includes a map of the policy intentions of all EU27 governments in key policy areas. ECFR carried out this process in collaboration with 27 associate researchers in individual member states. The Coalition Explorer and its complete data set can be accessed online at https://ecfr.eu/eucoalitionexplorer

Two indispensable countries: Why the Franco-German engine matters

While cooperation between France and Germany cannot shape EU policy by itself, the absence of a good working relationship between the two has a particularly negative impact on the EU’s ability to move forward. The EU27 survey reveals the importance of both actors; how they are viewed by each other and by their EU partners; and the potential they have to shape EU policy.

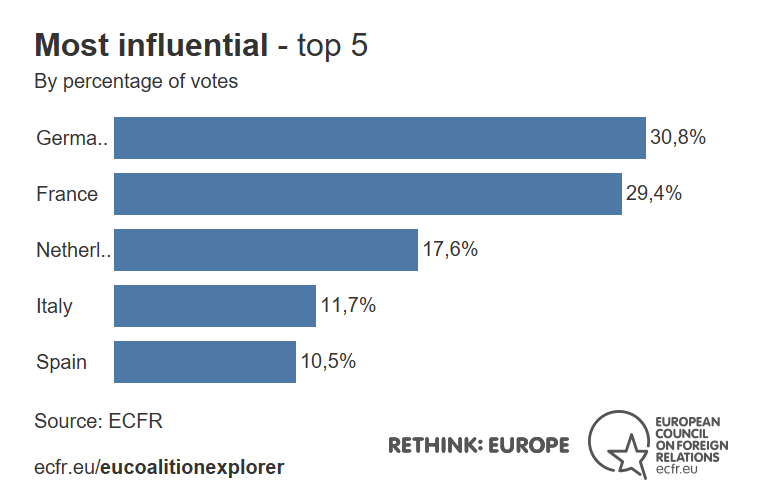

Germany’s special role

Since the publication of the first edition of the Coalition Explorer, in 2016, the overall picture has largely remained the same: Germany is the EU’s centre of gravity – its most influential country. This time, a whopping 97 per cent of respondents to the survey held this view. Germany is firmly embedded at the centre of a web of connections, relationships, and alliances that stretches across the EU. In 2020 Germany is once again not only the most-contacted country (82 per cent), receiving votes from every EU member state, but is also perceived as the most responsive and the easiest to work with (55 per cent). It ranks in first place on the question of shared interests in EU policy – albeit with only 44 per cent of the vote. If there was a beauty contest for EU coalition-building, Germany would be its winner.

The results of ECFR’s survey are in line with the ideas that German policymakers usually express about their country’s role in the EU. They like to see Berlin as an honest broker who handles competing claims and interests, not as a hegemon who makes the rules for Europe and imposes them on others. The survey shows that, in almost all policy areas, German respondents have a strong preference for making decisions based on a consensus between all member states and are reluctant to embrace differentiated integration – to work with only some EU members – as they fear that this could divide the union. German respondents expressed little desire to cooperate outside the EU framework in any of the policy areas covered by the survey. In the past, the German government has often emphasised the need to find a consensus with its European partners rather than force them into agreements. Berlin often claims to have an existential interest in preserving the European project, seeing Germany as the one country whose core task is to keep the club together.

However, Germany’s obvious coalition potential and its “self-perception as the EU’s master pupil” stand in stark contrast to its Europe policy and other member states’ perceptions of that policy. The EU27 survey shows that Germany’s relations with other states are not evenly balanced – everybody contacts Berlin, but Berlin is not equally responsive. Germany reaches out to France more often than any other EU country, followed – albeit at a distance – by the Netherlands and Austria. Spain, Poland, and Italy (in descending order) are also on the list of those contacted regularly by Germany. All other member states received few or no votes in the survey.

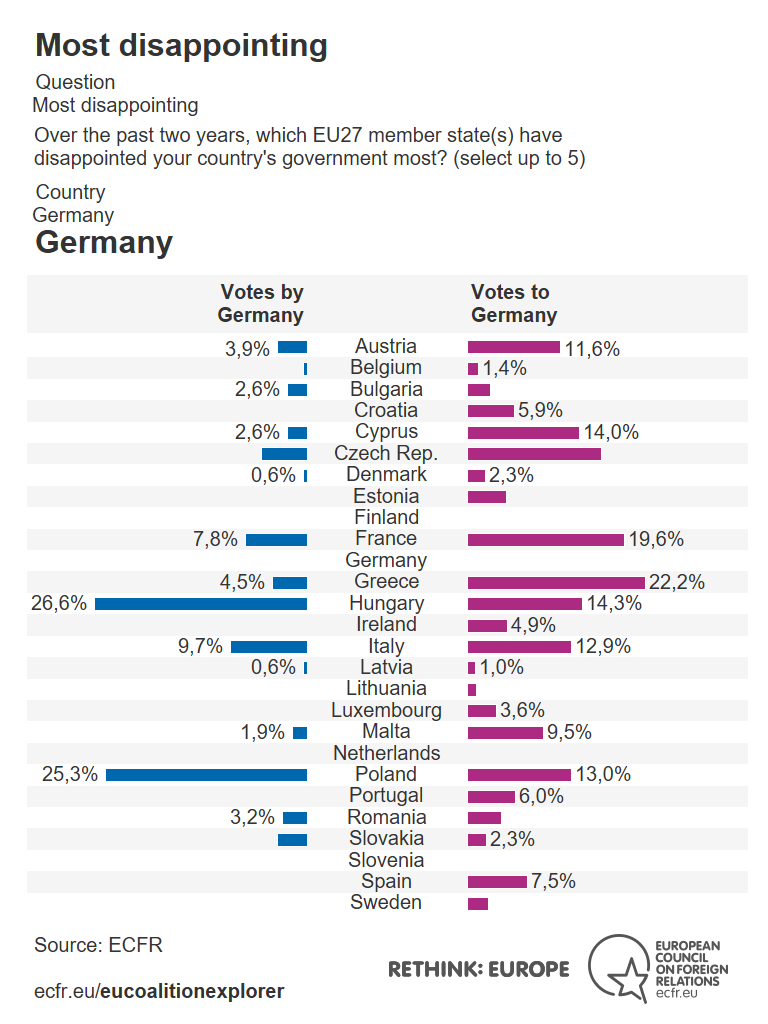

Moreover, many EU member states view German dominance as part of the problem. This was especially apparent during the eurozone and refugee crises, in which several southern and eastern European countries saw Germany as anything but a white knight. The repercussions of these crises can be found in ECFR’s latest survey. Greece leads the ranking of countries that express disappointment with Germany. Sixteen out of 28 Greek respondents chose the German government as the one that has disappointed their country most in the past two years. This might have been motivated by the belief that the austerity imposed on Greece – blamed primarily on Germany –weakened the country’s ability to deal with the covid-19 pandemic. In any case, when they followed the poisonous disagreements over “coronabonds” that took place in April 2020, many Greeks will have been reminded of the “Grexit” debate during the euro crisis. German leaders’ firm opposition to what they called a “transfer union” – which was still on full display when ECFR conducted the EU27 survey – likely helps explain why 18 of 41 respondents from Italy expressed frustration with Germany.

There is significant disappointment with Berlin among respondents from countries within the Visegrad group (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia). This is especially true of Hungarians (17 of 34 respondents) and, to a lesser extent, Czechs and Poles – perhaps still due to the fallout from the migration crisis of 2015, as well as Germany’s leading role in the debate over the rule of law in the EU. Still, many respondents from the Czech Republic and Slovakia – and, to a lesser extent, Poland – say that Germany shares many interests with their respective governments. The trend is particularly apparent among Slovakians, who express almost no disappointment with Berlin. Slovakia is the only Visegrad country that has taken in small groups of refugees. It is also the only Visegrad country in the eurozone, and it wants to become part of a “core Europe”. As ECFR’s Policy Intentions Mapping shows, Slovakia has diverged from the three other Visegrad countries in several areas, ranging from eurozone governance to the rule of law.

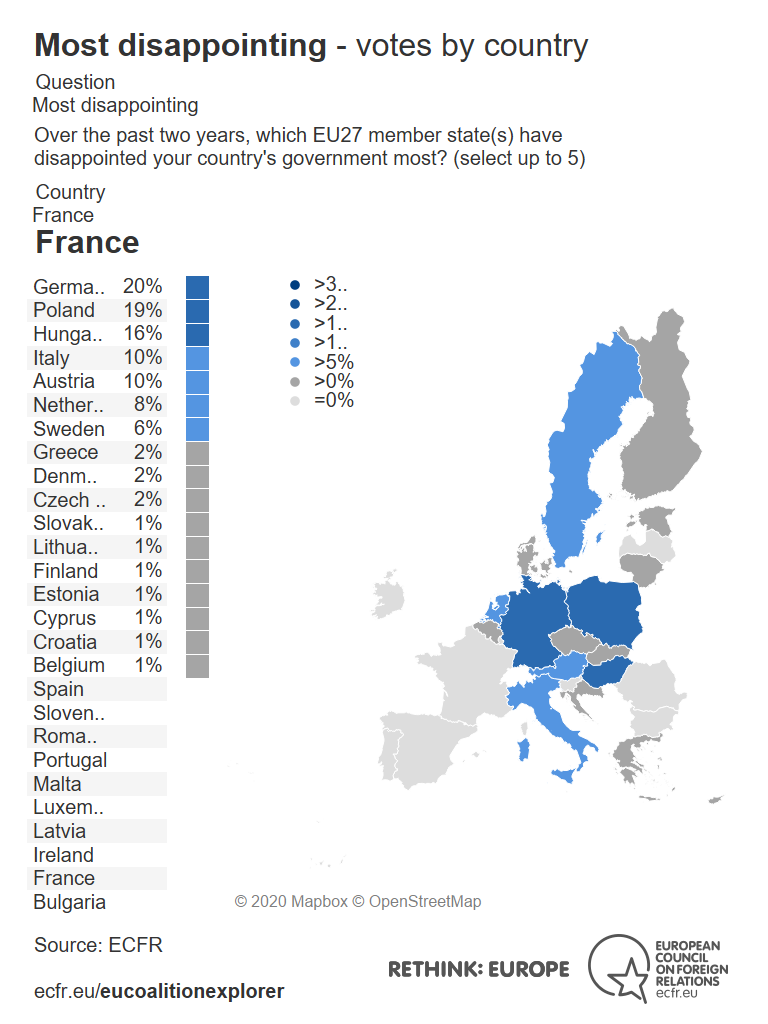

However, the most remarkable insight one can draw from the results above concerns the Franco-German couple: 20 of 36 French respondents view Germany as one of their top five most disappointing countries. This makes Germany the EU member state that the French are most disappointed with – ahead of Poland and Hungary. At the same time, France is clearly Germany’s closest ally in the EU. All German respondents chose France as their country’s most-contacted partner. When asked about their preferred partners in individual policy areas, Germans almost always named their colleagues in Paris first. Thus, it is not due to a lack of attention that Berlin’s closest partner feels so disappointed. The roots of the problem probably lie in Germany’s perceived lack of ambitious EU initiatives or a clear vision for the union’s future. Macron – who, after his election victory, placed all his bets on the German government to jointly reform the EU – appeared to feel that Germany had left him standing in the rain, waiting for Berlin to respond to the flurry of ideas he presented.

Yet, from a German perspective, the status quo is a thoroughly pleasant state of affairs. As such, Berlin’s unwillingness to change is understandable. As it has weathered the crises of the past decade far better than most member states, Germany feels no sense of urgency to make radical changes to the EU’s institutional set-up. Even during the covid-19 crisis, Germany has done remarkably well so far. For Macron, German sluggishness was too hard a nut to crack. Before the covid-19 crisis hit the EU, he appeared to have given up on Germany and to be looking for new European alliances.

The Macron effect: France in Europe

Ever since Macron became French president, he has been vocal on European policy and reform. Macron ran on a European platform: during his campaign, his supporters seemed to wave the EU flag as much as the national one – a rare sight even in the most pro-EU countries. He celebrated his electoral victory to the sound of the EU anthem, Ode to Joy. Macron has laid out his strategic vision for Europe in several speeches – most notably, one at the Sorbonne university in September 2017 – and in a series of widely discussed newspaper interviews. That Macron has a strategic vision for the future of Europe sets him apart from previous French presidents. And it differentiates him from German chancellors in general – particularly Merkel, whose approach to policy is widely described as pragmatic rather than visionary.

Given his ideas, drive, and, some might argue, personal charm, Macron should be able to use his position as the leader of Europe’s second-largest country to make a considerable mark on European politics. However, in a union of 27 countries, a vision is not enough in itself. A European leader also needs to be able to work with others. But will other Europeans accept the leading role that Macron envisions for France in Europe?

The data present a mixed picture. Europeans clearly see France under Macron as powerful: 93 per cent of the respondents consider the country to be one of the most influential countries on EU policy. That is almost on a par with Germany (97 per cent), and well ahead of the Netherlands in third place (55 per cent). France is also the second-most-contacted country, after Germany. Yet, here, the difference between the two is more pronounced, as more than 80 per cent of respondents say their governments contact Germany, while only half of them say the same about France.

On closer inspection, fissures emerge. France performs considerably worse than Germany in perceptions of being “most responsive and easiest to work with”. Although France takes second place in this measure, it does so mainly due to the generally low numbers for other countries: 27 per cent of respondents consider France to be responsive, just ahead of the Netherlands at 24 per cent.

This second-place status is a recurring theme of France’s role in Europe. Experts and policymakers around Europe see France as influential and important, but always after Germany. The German juggernaut, it seems, cannot be overtaken – charming presidents notwithstanding. While France sometimes comes close to rivalling Germany, the United Kingdom’s departure from the EU has ensured that there is no competition for second place. The Netherlands’ position in third place on most questions is quite remarkable, given the country’s size. It is an achievement that deserves its own analysis, especially since respondents agree that no one does more to punch above their weight than the Dutch.

Most European experts and policymakers think that France deserves to be in second place. Yet it is French respondents who seem most impressed by the country’s position under Macron, as support for the statement that “France punches above its weight” is highest in the country itself. While German respondents are more convinced than any other national group that their country punches below its weight, the situation in France is the exact opposite. Moreover, only French respondents say that France has as much influence as Germany. It appears that one of Macron’s achievements is to give his country’s political class the self-confidence of a prime actor in Europe.

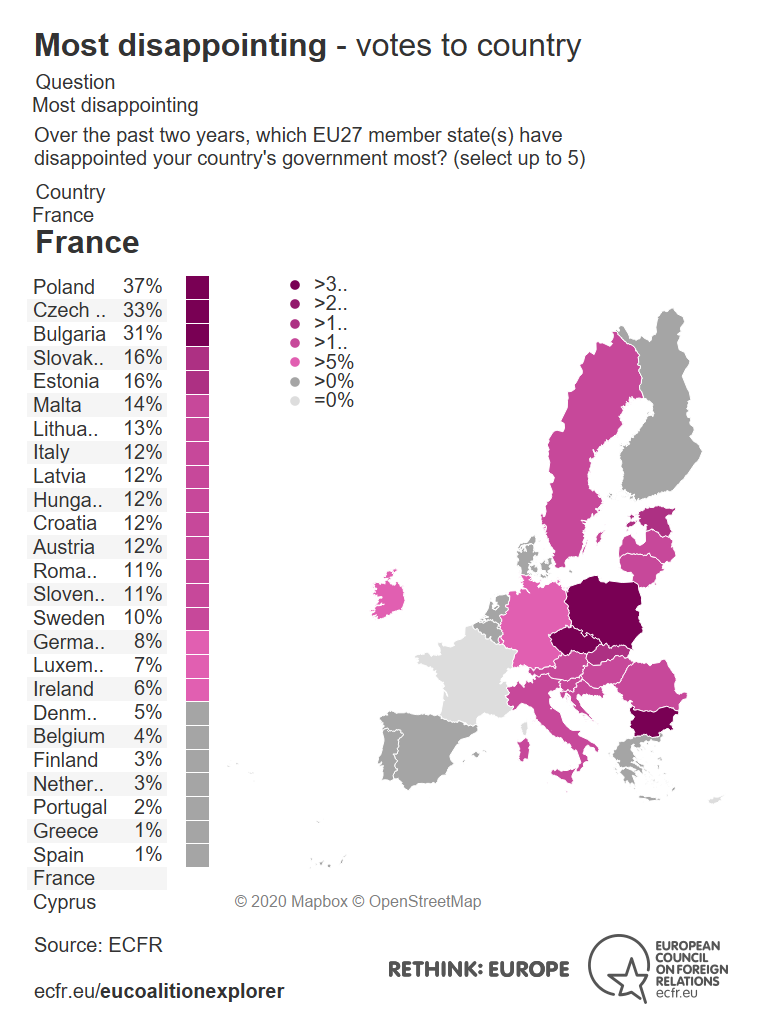

But, despite general agreement that France deserves its influential second place, there is also a lot of disappointment with the country in Europe. In fact, taken together, the EU27 see France as the third-most disappointing country – after Hungary and Poland, against whose governments the European Commission initiated Article 7 procedures for a clear risk of a serious breach of EU values. Many Europeans are unhappy with Macron’s initiatives. And eastern Europeans are the most unhappy with them of all. The states that express the most disappointment with France are Poland, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Slovakia, and Estonia. The states that say they work the least with France are Lithuania, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Latvia, and Estonia. The countries that say that France is unresponsive and difficult to work with are Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary. On all questions, it is eastern European member states that show the highest levels of disappointment with France.

Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Bulgarians, and Slovakians are nowhere near as disappointed with Berlin as they are with Paris. The figures for Germany from Poland and the Czech Republic are also better for Germany than for France; Hungary is the only eastern European country that is more disappointed with Germany than with France.

The explanation for eastern Europe’s disappointment with France may lie in diverging interests. Member states in the region make up nine of the ten countries that rank France in last place on the question “which EU27 member states generally share many of your country’s longer-standing interests on EU policy?” (the other is Sweden). This may come as no surprise given some of Macron’s recent policy ideas, particularly those on foreign affairs. He was widely criticised in the east for his efforts to reach out to Russia, and his assertion that the country would need to play a role in Europe’s security architecture. Equally, Macron’s comments on NATO’s “brain death” were badly received in eastern member states, which are especially reliant on the alliance’s security guarantees and are wary of any comment that might undermine its cohesion. French respondents also perceive a lack of shared interests with eastern European states, acknowledging that France primarily works with the governments of Germany, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium.

France’s position is stronger among southern European respondents, who report that they often contact the country and work well with it. In Greece, Cyprus, Portugal, and Spain, at least 80 per cent of respondents view France as easy to work with. This suggests that France can build bridges between northern and southern Europe: all southern European respondents list France among the countries they contact most; and Italy, Greece, and Cyprus even view France as their most important interlocutor.

While an outspoken French president has created some movement – and polarisation – in Europe, France remains the second power in Europe. No matter how strong and full of ideas a French leader might be, France will always come second to Germany – at least while Merkel is chancellor. Recent compromises on EU bonds suggest that one of the biggest roles that France can play is in influencing Germany. This is also reflected in language – initially, German elites were no fans of the “European sovereignty” line used by their French partners. Now, even the German foreign minister cites this term as a primary goal for the German EU presidency. And, as France builds bridges to the south, Germany can do so to the east.

Prospects for a geopolitical Europe

While Europeans are busy dealing with the internal consequences of the covid-19 crisis, the world is in the midst of dramatic and disruptive change. Europeans find themselves surrounded by great power rivalry and zero-sum thinking, with a rising and ever more vigorous China, a revisionist Russia, and a US whose president is sceptical of, and often openly hostile to, the EU. The pandemic only accelerates these trends, deepening pre-existing fault-lines such as those between Washington and Beijing, while further eroding multilateralism. In light of these developments, Macron and Merkel – as well as European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen – have called for a bigger European footprint in the world. They are united in their goal of creating a stronger and more independent Europe that shapes the world, instead of being shaped by others. In this environment, Germany and France should work to empower the EU through joint foreign policy initiatives, just as they are trying to do internally with the recovery fund.

Not all recent experiences in this area have been positive. Macron’s idea of a rapprochement with Russia, his comments about NATO’s alleged brain death, and his initial veto on EU accession talks with North Macedonia and Albania were not well received in Berlin. The German government has little time for Macron’s confrontational political style. At the same time, the French president has been visibly annoyed by Berlin’s lack of a sense of urgency.

Franco-German divergence

The EU27 survey provides insights into why France and Germany find it so difficult to work together on foreign and security policy, despite the fact that each sees the other as its most important partner – and as having the same position on the substance of most key policy areas. Among the 20 issues that ECFR asks policymakers and policy experts in all EU capitals to rank in order of priority, nine directly relate to foreign policy: common defence structures, a common foreign policy, and a common development policy, as well as common policies vis-à-vis Russia, China, the US, Africa, Libya, and Iran. German and French respondents clearly have diverging priorities on these topics.

Geopolitical issues seem to be much more important for French respondents than they are for their German counterparts. Five of French respondents’ top ten priorities are foreign policy issues, compared to just three for Germans. France’s top priority – defence policy – does not appear in the German top ten. There are three foreign policy topics (defence, China, and European foreign policy) in French respondents’ top five, while just one (China) in Germans’.

Measures of alignment with overall EU priorities expose an even more striking difference between Paris and Berlin. Here, France’s external focus seems detached from the rest of the EU. Put bluntly, French respondents do not care about the same things that concern most other Europeans. Germany shares four of its top five priorities – fiscal policy, migration, climate, markets, and digital issues – with those of the EU27 overall. France, in contrast, shares only two: climate and fiscal issues.

Despite France’s aforementioned good connection with southern European countries, there is little alignment between them – especially with regard to the importance of foreign policy. Unlike France, southern European countries do not generally prioritise foreign policy. The top concerns of this group are immigration and border security. Accordingly, fiscal policy is the only top five priority that France shares with southern countries (and the top overall priority of the EU27).

Of course, a shared sense of an issue’s importance does not necessarily translate into an agreement on policy. But significant differences on which topics deserve the most attention bodes ill for cooperation and coalition-building.

Germany |

EU27 |

France |

|---|---|---|

| Fiscal and eurozone policy | Fiscal and eurozone policy | Defence structures |

| Climate policy | Immigration and asylum policy | Climate policy |

| Immigration and asylum policy | Climate policy | Fiscal and eurozone policy |

| Digital policy | Single market | China policy |

| China policy | Digital policy | Foreign policy |

| US policy | Energy policy | Industrial policy |

| Border and coast guard policy | Western Balkans enlargement | Immigration and asylum policy |

| Foreign policy | Russia policy | Russia policy |

| Rule of law | Border and coast guard policy | Digital policy |

As discussed above, France is much more willing than Germany to work with small groups of EU member states, as the latter prefers to include all EU member states in its initiatives. This difference is particularly apparent in the areas of European defence and European foreign policy, which have often led to discontent and other problems. As recent French-led efforts such as a naval mission in the Strait of Hormuz, Operation Tacouba in the Sahel, and the European Intervention Initiative show, France often prefers to conduct operations completely outside the EU framework. This creates legal problems for, and political resistance from, the German government. France often perceives Germany as not only failing to share its most important political priority but also as blocking progress in the area.

In sum, while the German chancellor and the French president agree that the world as we know it has gone off the rails, they differ significantly in the lessons they draw from the situation. This explains why French officials often privately complain that the Germans fail to confront geopolitical reality, lack a sense of urgency, and move sluggishly. Meanwhile, many in Berlin accuse the French of being needlessly divisive, and of putting forward half-baked proposals.

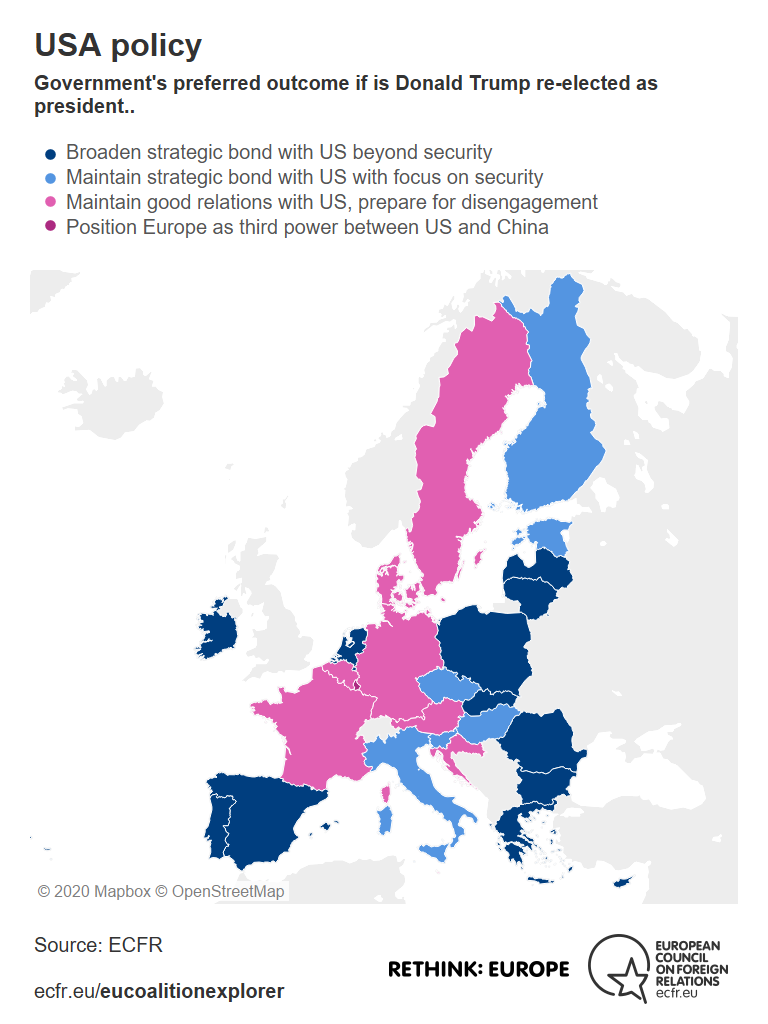

Relations with great powers

One French diplomat seemed to speak for many of his compatriots when, at a recent ECFR foreign policy roundtable, he called Donald Trump’s election as president of the US a “divine surprise”. Many decision-makers who shape French foreign policy see the Trump presidency as an opportunity to become more independent from the US and vigorously push for greater European sovereignty. Three years into the Trump presidency, the Germans also recognise that transatlantic relations are in bad shape. The American president’s recent announcement that the US would cut its troop presence in Germany by more than 25 per cent – purportedly because the country was spending too little on defence – is just the tip of the iceberg. Time and again, Trump has singled out the German government and made it the focal point of his critiques. Although it still holds on to its ties with the US more strongly than France does and emphasises the unchanged relevance of NATO, Germany is increasingly aware of the changing nature of American engagement with Europe.

The EU27 survey reveals the significant differences between Europeans’ priorities in their policies on the US. French respondents rank their country’s approach to the US as the tenth-most important of 20 policy areas. Meanwhile, German respondents rank it in sixth place. In Lithuania, Poland, Estonia, and Romania, policymakers and experts include US policy among their governments’ top five priorities. But, in 17 other EU countries, policy on the US did not make it into the top ten. It seems that most European countries no longer expect anything from the Trump administration, which has regularly opted for “America First” policies rather than cooperation with them. They appear to simply hope that things will not get any worse and shift their attention to other matters. A slow decoupling between the US and parts of Europe may be on its way, as ECFR’s Policy Intentions Mapping shows. Some member states, especially those in the east, want to strengthen their strategic bond with the US. Yet others, including Germany and France, say that it might become necessary to prepare for disengagement.

The transatlantic relationship could become an even more divisive topic if Trump wins re-election in November and continues to give European countries the impression that the US security guarantee is only for allies he believes deserve protection. Some member states, particularly those on NATO’s eastern flank, see the United States’ presence in Europe as life insurance – and are potentially much less ready to join team Europe when interests on either side of the Atlantic collide. Accordingly, Macron may want to take a less divisive approach to uniting Europeans and making them more capable of asserting international influence without the US – especially in relation to NATO. The EU27 survey shows that the EU’s eastern capitals see Berlin as a better partner than Paris in dealings with Washington. It also demonstrates that a majority of respondents in almost all EU member states favour a pan-European approach to the US. The exceptions are Hungary and Poland, which prefer to deal with the US on a bilateral basis.

In this year’s edition of the survey (as in previous years’), the highest-ranking foreign policy issue for member states overall is Russia, ahead of the rise of China and the precarious transatlantic relationship. Russia appears among the top ten priorities of 13 EU countries. In Poland, it is the highest priority; in the Baltic states, it comes in second place; and, in Sweden, it comes in third place. Surprisingly, Germany does not see Russia as one of its top ten foreign policy priorities.

In Macron’s eyes, Europeans need to reopen a strategic dialogue with Moscow. He contends that alienating Russia and pushing it further into China’s arms only weakens Europe’s position internationally. Europe, so the argument goes, needs to create a new order of “trust and security” that includes Russia if it is to assert itself in relation to both China and the US.

ECFR’s survey shows that these ideas have won him little sympathy in the EU, with most member states regarding France as a less important partner than Germany on Russia issues. The Baltic states and Poland clearly prefer to cooperate with Germany and, even more so, with each other in this area.

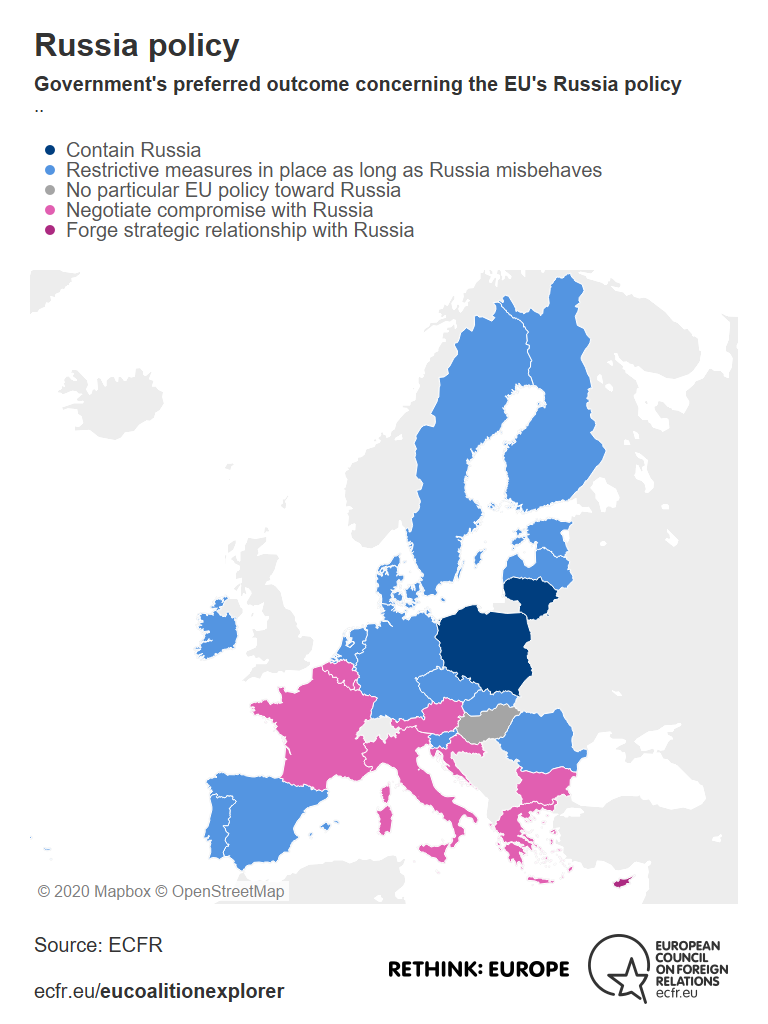

Nevertheless, the EU27 survey shows that there is the potential for a common European approach to Russia, with a majority of respondents in most member states preferring this option. But ECFR’s Policy Intentions Mapping shows that it will be difficult to overcome the substantive divides between them. Even the German government, which always emphasises the need for dialogue with Moscow, has not bought into Macron’s push for rapprochement with Russia. Only Italy, Austria, Belgium, Greece, Croatia, and Bulgaria favour such rapprochement – whereas most of the rest either want to sustain restrictive measures on Russia for so long as it misbehaves, or (in the case of Poland and Lithuania) want to implement a containment policy on the country.

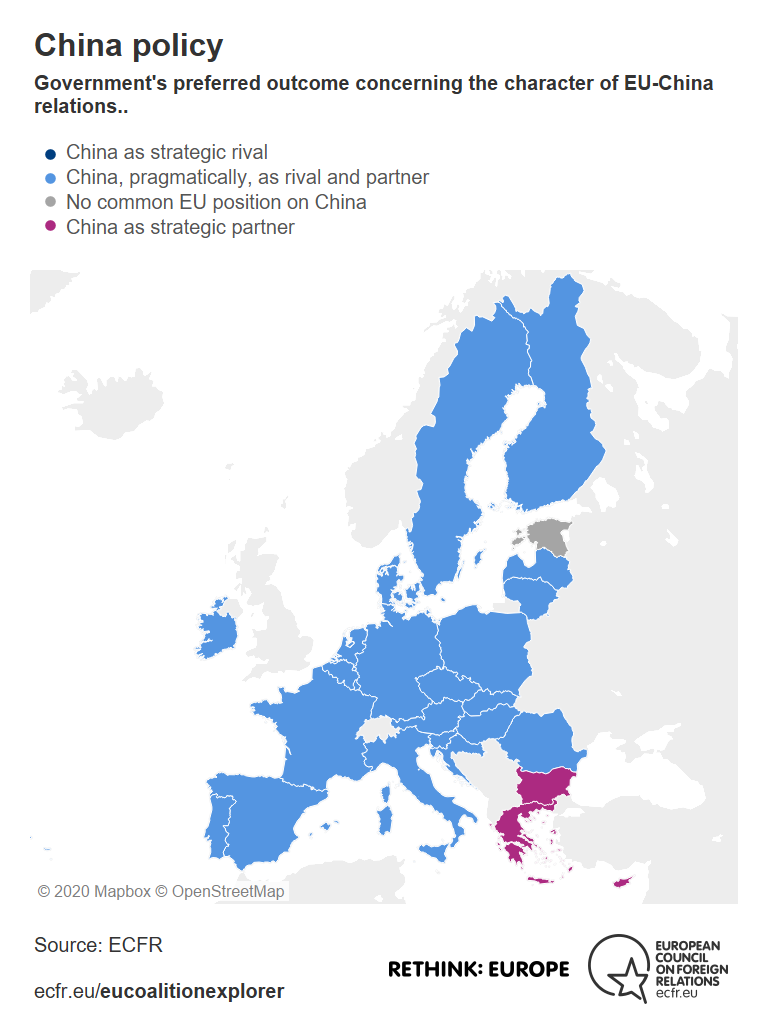

Judging by ECFR’s EU27 survey and Policy Intentions Mapping, the greatest point of agreement between Paris and Berlin is to be found in their assessment of China policy. Both are convinced that all EU member states need a common approach to Beijing. Seventy-one per cent of French respondents and 74 per cent of German respondents hold this view. China policy also has a similarly high status in France and Germany, ranking in fourth and fifth place in their policy priority lists respectively. Here, there has been an enormous change in awareness in the last two years. In the 2018 edition of ECFR’s expert survey, China ranked in eleventh place on Germany’s priority list and in twelfth place on France’s. Today, all EU members aside from Greece, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Estonia agree that the EU should approach China pragmatically, as both a rival and a partner.

However, only respondents in Hungary, France, and Portugal attach a high priority to China issues. The rest of the EU does not yet seem to have fully recognised the challenge that Beijing poses. China policy only ranks in twelfth place on the overall priority list of the EU.

More member states see France as an important partner on China policy than on Russia or US policy – even though Germany has greater partnership potential than France. But member states are still a long way from forging a unified China policy; even Paris and Berlin often plough their own furrows in this area. In the bilateral context, member states often show little willingness to put Europe’s strategic interests first, mostly competing for China’s favour and seeking good economic relations with the country.

This lack of awareness of, or concern for, the strategic implications of China’s rise seems to be the biggest obstacle to a more geopolitical Europe. Given that Russia is the EU27’s leading foreign policy priority overall (in eighth place), it is clear that member states are still geopolitical navel-gazers. Regardless of who wins the US presidential election in November, the rivalry between the US and China is likely to become more intense in the years to come. Both countries will increasingly see relations with Europe through the prism of this rivalry, emphasising bilateral relations rather than the EU’s multilateral structures. Germany and France need to jointly lead an effort to prevent the US and China from pitting EU member states against one another.

Complacency on European defence

Defence issues received no airtime within the EU for decades, but have recently become an area of intense activity. The stars – or, perhaps, storm clouds – aligned for European defence when, in quick succession, Russia annexed Crimea, the UK decided to leave the EU, and Trump was elected as president of the US. These events served as wake-up calls for many Europeans, making cooperation between them on a notoriously divisive topic all the more urgent – and, in the case of the UK’s departure – easier. In a short time, the EU reached important milestones, devising initiatives such as the European Defence Fund and Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) to build up “European strategic autonomy” or “European sovereignty”. Under Macron, France took a particular interest in the topic, arguing that – given that the US was likely to pivot to Asia or drift into isolationism – Europe would need to build up credible defences of its own.

But European defence also became the subject of a Franco-German quarrel. On PESCO, Germany argued for an “inclusive” approach that included as many EU member states as possible, while France envisioned a vanguard of European states that were willing and able to do more. Germany’s vision won out. France, in contrast, allegedly pressured Germany not to buy American F-35s – warning quite forcefully that such procurement would threaten the Future Combat Air System (FCAS), a joint Franco-German fighter jet project. Complaints about an unfair division of labour, disagreements over leadership, and concerns about the future development of the FCAS programme also created bad feeling on both sides. Equally, 2019 saw a long Franco-German dispute over arms exports, in which Germany wanted to implement more stringent restrictions on them, and France resisted the move by emphasising their importance to maintaining European capabilities. They eventually found an uneasy compromise, but the issue lingers.

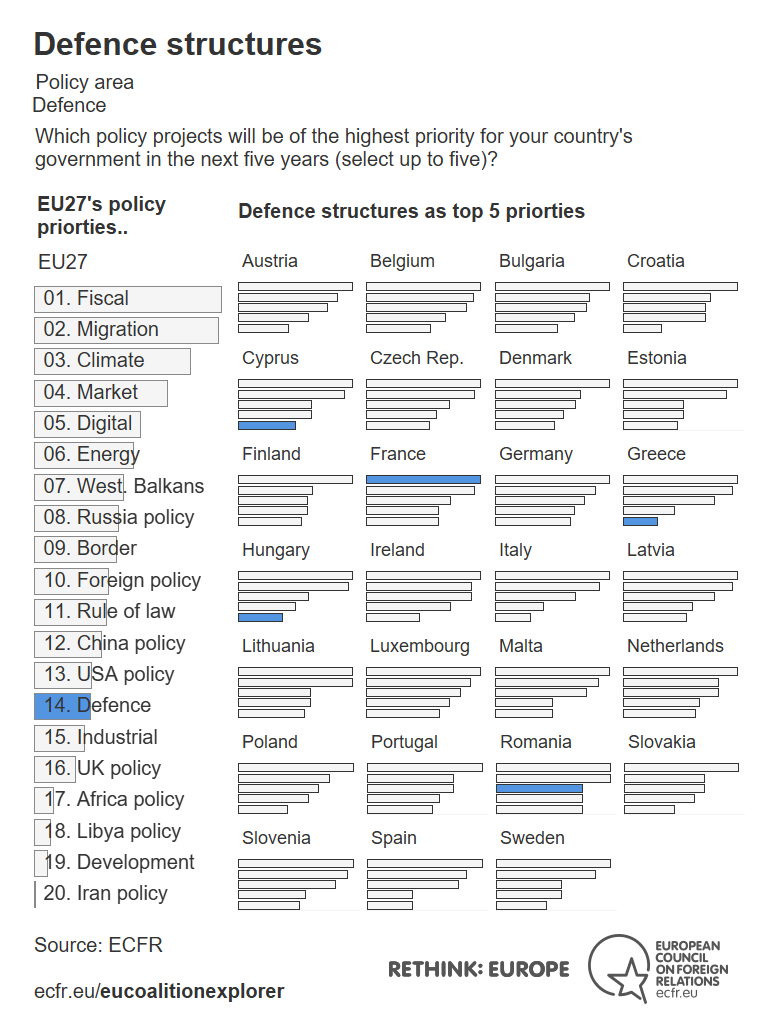

As ECFR’s EU27 survey underlines, defence remains a difficult topic for Europe, as well as a source of Franco-German discontent. Defence cooperation ranks in fourteenth place among the policy priorities of the EU27 – far below fiscal policy, migration, and the reform of the single market. In fact, 17 European states do not have defence in their top ten priorities. The issue is in the top five only for France, Cyprus, Greece, Hungary, and Romania.

As noted above, the divergence is starkest with the Franco-German couple: Germany – in line with the EU average – ranks defence in fourteenth place (out of 20 priorities). For France, however, defence is number one. Europe’s ability to defend itself is clearly on the mind of Macron, who disrupted European harmony by harshly criticising NATO in an Economist interview.

Defence, more than any other issue, is a difficult topic for EU cooperation, as there is the lowest level of agreement on the need for an EU-wide policy in the area. Across the EU27, only 37 per cent of respondents say that defence policy is an issue for the EU, while 29 per cent see it as a topic for sub-groups of member states, and 18 per cent view it as a matter for cooperation outside the bloc’s structures. Again, there is Franco-German disagreement: Germany prefers to do as much as possible on the EU level – and, when it comes to military operations, to some extent, is legally required to do so – while France is much more interested in cooperating only with countries that are willing and able to take part. Interestingly, most respondents consider it equally important to work with France and Germany on defence – despite the countries’ diverging approaches. Only Hungary and Poland see Germany as a more important interlocutor than France on the topic.

There are two possible explanations for these European divergences on defence, particularly in relation to the German approach. The first is mission-accomplished syndrome; the second is Macron-appeasement policy.

It can, at times, be striking to see the world from the perspective of the government in Berlin, where a self-congratulatory mood suffuses discussions about Germany’s role in European security and defence. The country, it seems, feels like it has done its part on European defence. Yet celebrations of progress on common EU structures might have been counterproductive, as they suggested that the problem of European defence had been solved. German policymakers might have taken this as a declaration of victory – and moved on.

The alternative explanation for Germany’s (as well as other Europeans’) de-prioritisation of European defence might lie in a desire to avoid widening divisions within the EU. It is possible that, in the last year, Germany has realised that Europeans’ views on common defence diverge quite dramatically – and, therefore, decided not to dwell on the issue. This could be part of an effort to placate Macron and avoid undermining Franco-German cohesion. Germany and France have different ambitions when it comes to European defence. For most German decision-makers, including those in the defence ministry and the Bundeswehr, NATO under US leadership remains key to German defence. They see any efforts to build up European defence as a way to strengthen the European pillar of NATO. France traditionally has a more sceptical view of NATO and, under Macron, has been more seriously entertaining the notion that the alliance might fail, forcing Europeans to guarantee their own security. Given their consensus-focused approach to policymaking, Germans often deprioritise areas in which they see a possibility for conflict. Thus, Germany’s position on defence could be seen as an acknowledgement that, given how much its views differ from France’s, placing the issue on the backburner is preferable to risking disagreement. Furthermore, disagreements on defence between members of Germany’s ruling coalition make them relatively reluctant to work on the topic at the European level.

However, both mission-accomplished syndrome and Macron-appeasement policy are based on misguided assumptions. Firstly, it should be obvious that it is too early to declare “mission accomplished” on European defence. Merkel may have made no speech on an aircraft carrier to that effect but, in spirit, the assumption that Germany can afford to rest on its laurels is about as correct as George W Bush’s infamous assessment of the 2003 Iraq war. Recent quarrels over the size of the European Defence Fund – which, at times, has looked as though it will receive no funding whatsoever – serve as a reminder that victory is far from certain.

Equally, Franco-German disagreements on defence may have been exaggerated by the commentariat. But it achieves little to hide from such disagreements. Thus, neither approach is helpful for building European defence capabilities. If Germany deprioritises EU-level defence, this will likely delay efforts and, therefore, progress in the area. Could Germany, in working to keep the peace with France, in fact be endangering peace in Europe?

The politics of flexible unity

As ECFR’s EU27 survey shows, Germany and France have far greater influence within the EU than any other member state. There is no third country that even comes close. Brexit has only made this more obvious. Due to their prominent positions and the fact that they are almost on a par in their importance and connections with other European countries, Germany and France will be unable to achieve much within the EU while they take different paths. The years since Macron took office have shown this. While he wanted to vigorously disrupt the status quo, Merkel embraced it. While Macron wanted to aggressively push through his ambitious ideas for reform, she wanted only to make cosmetic changes. As a result, they have made little progress at the European level – a fact that, in France, has led to deep frustration and disappointment with Germany.

Eventually, Macron adopted a different strategy and started to act separately from Germany in European affairs, looking to forge new alliances. However, as Coalition Explorer data demonstrate, he could not persuade other member states to go along with him. Even southern EU countries share fewer interests with Paris than one might assume. Many of Macron’s foreign policy ideas have been highly polarising, and have prevented him from improving France’s relationship with central and eastern European states. This is why, as discussed above, the EU27 see France as the third-most disappointing country overall – after Hungary and Poland.

Germany, meanwhile, is viewed more favourably by its EU partners. The country is a sought-after ally in all policy areas, is widely perceived as responsive, and has established a reputation as an actor with which many member states have shared interests. However, Berlin has not used its enormous potential to further develop the European project in recent years. Instead, the Merkel government has maintained what Josef Janning once called its “ultra-pragmatic, status quo-minded course of non-action”.

The covid-19 crisis appears to have brought about a turnaround in the situation, as the need for a European reconstruction fund has forced Berlin to break out of its EU paralysis – with France’s help. Europeans must use the momentum created by the Franco-German agreement on the fund to give the EU a stronger voice in foreign and security policy. Given that summits in Brussels now focus predominantly on internal EU policy, France and Germany should lose no time in pushing other member states towards greater cohesion on foreign policy. Together, France and Germany have all that they need: the south and the east, the ambition and the pragmatism, and the coalition potential.

For the EU to establish a strong common foreign policy, its member states will first need to change their mindset. They can no longer afford the luxury of attributing foreign policy issues as little priority as they do in the EU27 survey. Their failure to recognise the importance of escalating great power rivalry for all EU internal policy areas is the biggest obstacle to a more geopolitical Europe. In the last two years, Macron has worked hard to get this message across. However, due to his confrontational style and his lack of regard for sensitivities about the US and Russia, the flaws of the messenger have often overshadowed the message. Here, Germany – which hardly has a reputation as an alarmist – can help to convey that message.

Paris should not be so bold and divisive. Instead, it should try more actively and sensitively to work with its partners who are critical of French foreign policy initiatives, particularly Warsaw and Baltic capitals. They are the key players in establishing a common European policy on Russia and the US. Because they see close ties with the US as the only credible defence against an aggressive Russia, the EU will be unable to achieve greater cohesion on its Russia policy unless it addresses transatlantic relations at the same time. In concrete terms, this means that Macron should take central and eastern European countries’ security concerns seriously, even if he does not share their threat perceptions. If France does not do so, this will alienate not only states on NATO’s eastern flank but also Germany, which traditionally sees itself the EU’s main advocate of these countries.

In the past, there was a widespread assumption that a compromise between Germany and France would receive the support of many other member states. This is because the two countries hold such contradictory positions on many issues that a compromise would inevitably find the EU’s lowest common denominator. Yet, on Russia policy and the transatlantic relationship, the antipodes are more likely to be France and Poland. If these two countries agreed to a common line on either issue, this would form the basis for a consensus.

If it wants to support greater cooperation on defence, Germany will need to reprioritise the topic. It is fine to leave leadership on the issue to France but, without Germany’s commitment, French efforts will never produce the pan-European defence capabilities that are so urgently needed. Most importantly, on the domestic level, Germany needs to take on the question of to what extent the country can participate in smaller “coalition of the willing” operations that would take place outside the EU framework. Not only is this a French preference; given foreign policy disagreements among the EU27, such coalitions are likely to be needed in the future.

Sino-European relations will probably be the major foreign policy topic of the German presidency of the Council of the EU (even if the EU-China summit in Leipzig has been postponed). Here lies the greatest current opportunity to bring most EU member states together in a joint approach. ECFR’s analysis has shown that European officials and analysts have become more aligned in their views on China. And all European countries aside from Hungary, Greece, and Italy have a clear preference for EU27 action on China.

The EU must try to speak to the US, Russia, and China with one voice – as far as is possible. Nevertheless, there may be occasions when member states cannot achieve such unity. After all, foreign policy challenges cannot wait until the EU has sorted out all its internal disputes, especially if only one or two member states block the wishes of all the others. In the coming years, European states might have to choose what is more important to them even more often: EU unity or Europe’s ability to act. Accordingly, Germany should be more open and flexible in formulating foreign and security policy with relatively small groups of member states. Such coalitions of the willing do not necessarily undermine the cohesion of the EU or negatively affect EU measures on a specific issue. Rather, they can help the union achieve its objectives and increase its credibility as a global actor.

About the authors

Jana Puglierin is a senior policy fellow at ECFR and head of its Berlin office. She has published widely on European affairs, foreign and security policy, and Germany‘s role in the EU, and is a frequent commentator in the German and international media. She is a member of the extended board of Women in International Security (WIIS.de).

Ulrike Franke is a policy fellow at ECFR. She writes on German and European security and defence, the future of warfare, and the impact of new technologies such as drones and artificial intelligence, and regularly appears as a commentator in the media on these topics. She co-hosts Sicherheitshalber, a German-language podcast on security and defence. Franke is a member of the leadership committee of WIIS UK.

Acknowledgements

The authors are particularly grateful to Josef Janning and Almut Möller for developing the EU Coalition Explorer. We were able to build on their years of experience, insights, methods, design, and network. All this has made it easy for us to further develop this great tool. Without the experts and policy professionals who participated in the EU27 survey and shared their expertise and insights on European affairs, this work would not have been possible. We thank them for taking the time to support this research.

The EU Coalition Explorer is yet again the result of exceptional teamwork from the Rethink: Europe project team. Special thanks go to Chris Raggett for patiently supporting the editing process, to Marlene Riedel for helping with visualisations, and to Tara Varma, Jeremy Shapiro, Rafael Loss, and Pawel Zerka for their comments and ideas. Thanks also go to Christoph Klavehn for visualising the data in a compelling and accessible fashion. We are deeply grateful to Stiftung Mercator as the partner and funder of the Rethink: Europe project for the excellent cooperation and the trust placed in us.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.