Star tech enterprise: Emerging technologies in Russia’s war on Ukraine

Summary

- The use of new technology in Russia’s war against Ukraine has captured the imagination of governments and media alike.

- Many of the technological advances the world has made over the past decades have featured in the conflict, including in drones, software-defined warfare and AI, and space technology, as well as cyber warfare.

- If Europeans are serious about their defence capabilities, they need to look closely at the use of this technology on both sides.

- They will find that private companies have played a huge role in this war. This implies a different approach is necessary in the way states and private companies interact, and in how firms deal with technologies that could be used in warfare.

- Technology has also enabled and motivated the involvement of individuals in this conflict to a degree that would likely be replicated in a future war. States need to consider ways to channel this engagement.

- Finally, the war demonstrates that the quantity of weapons still matters, and that the old adage of military studies that the integration of new systems is at least as important as the technology itself remains true.

Introduction

“The courage of Ukrainians + technology = the key to Ukraine’s future victory.” Ukraine’s deputy prime minister, Mykhailo Fedorov, formulated this equation for Ukraine’s victory in April 2023. For him, the war between Russia, which invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022, and Ukraine, which has been defending its people and territory since then, is a “technology war”.

Analysts have already dubbed it the first commercial space war, the first full–scale drone war, and the first AI war. Ukrainian civilians inform their armed forces of Russian advances by logging sightings of military vehicles in apps. Drones populate the skies 24 hours a day, streaming back images of troop movements and attacks. According to Fedorov, cloud services “basically helped Ukraine survive as a state”.

This war is, of course, not all about “emerging or disruptive” new technologies – as NATO calls them: AI, apps, automated systems, and more. Some of Ukraine’s most urgent demands have been for tanks, artillery munitions, and fighter jets. Soviet-era air defences are playing crucial roles. “Dragon’s teeth” anti-tank obstacles – something most Europeans associate with the second world war – are making a reappearance, protecting the rows of trenches that scar the front lines. But the way both sides have put emerging technology to use in this context is revealing. The war in Ukraine employs, in one way or another, most of the technological advances the world has made over the last decades. If Europeans want to be serious about building up their defence capabilities, they need to pay close attention to and learn from Ukraine’s and Russia’s experiences so far.

This paper therefore examines the role of drones, cyber warfare, software-defined warfare and AI, and space technologies in the war in Ukraine. It reveals how the conflict has become a testing ground for new military systems. Innovation is happening at high speed. Never before have so many drones been deployed in a military confrontation. Cloud services and cyber defences have provided existential support. Software, often AI-enabled, is used to improve legacy systems. Without support from satellites, Ukraine would not be able to defend its territory.

Europeans should draw four distinct lessons from this. Firstly, it is difficult to overestimate the impact that private companies have had in this war. Big US tech companies, and smaller more specialised firms, have provided high technology and cyber support and allowed Ukraine to move its data to the cloud and digitise the battlefield. Commercial drones are playing a vital role. Secondly, new technologies have enabled and motivated the involvement of individuals in this war – from volunteer fighters and amateur open-source investigators, to drone crowdfunders and meme warriors. Finally, on the military side, scholars studying new technologies in warfare will not be surprised to hear that how the technology is used and integrated into the military organisation matters more than the technology itself. And, despite the ability of technology to help create more powerful systems that dominate older weapons, quantity still matters.

Drones

Few weapons systems have received as much media attention in the coverage of this conflict as drones. Only three months into the war, Alex Kingsbury writing in the New York Times had already decided: “All wars have their iconic weapons. … In Ukraine, it’s the drone.” Other commentators have characterised the conflict as the “first full–scale drone war”, and asserted that drones could usher in a “new era of warfare”.

The Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 initially captured most of the headlines, with some heralding it as a symbol of Ukrainian resistance. Ukrainian artist and soldier, Taras Borovok, penned a viral song about the unmanned system; supporters of Ukraine around the world crowdfunded to buy more of the drones for the country’s war effort. A few months later, however, another drone began to monopolise the front pages, as Russian forces deployed it to terrorise Ukrainian citizens and target critical infrastructure: the Iranian-made Shahed 136 loitering munition (aka “kamikaze drone”). Since then, other systems have attracted attention, most recently, naval drones for their role in striking Russian ships in the Black Sea, as well as Ukrainian systems used to attack Russian territory.

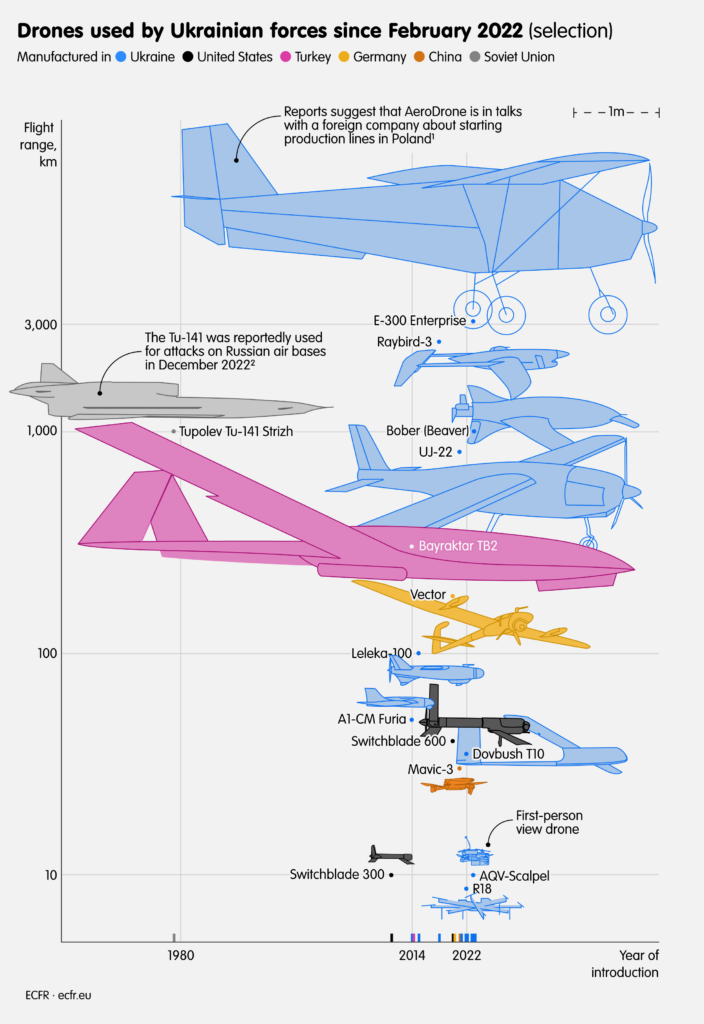

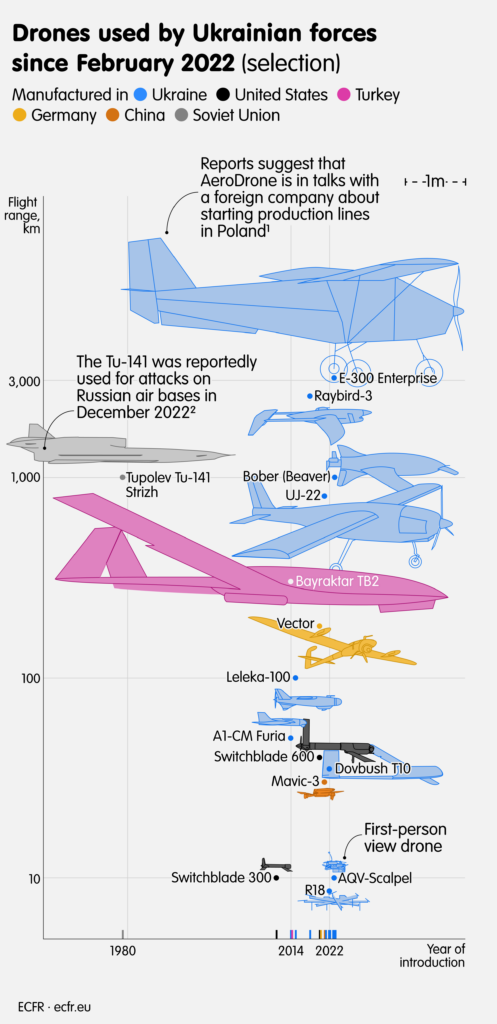

For both Ukraine and Russia, different unmanned systems – primarily, though not exclusively, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) – have proven decisive at different moments. But the way public attention has jumped from one system to the other, singling out one while disregarding others, suggests that the impact of ‘drones’ is not so easy to pin down. Hundreds of different drone systems are today in use over Ukraine, a hodgepodge of commercial, hobbyist, military, makeshift, and other systems – flown by soldiers, volunteers, and civilians.

“I knew … that Ukraine was going to stun the world with what it could do with small do-it-yourself and consumer drones, a skillset that their drone hobbyists and tech experts had been tirelessly expanding ever since Russia’s earlier invasion in 2014.”

Faine Greenwood, drone expert at the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, 2023

Greenwood’s observation describes two of the most striking aspects of this war: the extensive use of non-military drones by the Ukrainian forces and the impact of Ukrainian volunteer and hobbyist drone units, such as Aerorozvidka – whose members, she says, “have become some of the world’s premier experts on building, modifying, and using small, cheap drones in warfare”.

To some extent, Ukrainians are using these commercial, off-the-shelf drone systems simply because of their immediate availability and replaceability. But their use also reflects the impressive capabilities commercially available drones have acquired over recent years, including high-level sensors, easy-to-use controls, and seamless first-person views. Moreover, they offer these abilities at a much lower price than systems made for the military, meaning forces can accept losses – of which there are many, not least because they are not hardened with the same physical and electronic protection as military drones.

In addition to civilian systems, Ukrainian forces use a variety of military drones. Some of these drones were built specifically for this war, others have been in use for years, while a few have even been reintroduced into service after years of being mothballed. They range from small loitering munitions, such as the US-supplied Switchblade, a kamikaze drone – the smaller variant of which is a warhead of only a few kilogrammes – to systems weighing several thousand kilos that fly for hundreds of kilometres. An Australian company has provided cardboard drones. A British firm offered 3D-printed suicide drones. A German company delivered over 100 AI-supported surveillance drones. The smallest available military surveillance drones, Norwegian–produced Black Hornets, are also in use in Ukraine. In short, Ukraine has become a testing bed for new and new-ish systems, with producers in direct contact with troops, refining their products as the fighting drags on.

The Ukrainian government wants to build on this through its “army of drones” effort. This initiative aims to fundraise for and procure hundreds of commercial drones – from companies and individuals in Ukraine and abroad – to monitor the frontline, as well finance maintenance and training. Ten-thousand drone operators have already been trained under the programme. The government has also reportedly allocated $867m to create 60 “drone army” strike companies. Fedorov has specifically advertised the initiative as “a great opportunity for drone manufacturers to test their equipment in harsh conditions”. In August 2023, the head of Ukraine’s special communications service, Yurii Shchyhol, announced that “Ukraine plans to produce and purchase approximately 200,000 combat UAVs during the year.” (He was most likely referring to kamikaze drones, rather than combat drones in the broader sense.)

Through this initiative and others, Ukraine has become an important place for drone development and manufacturing. Ukrainian defence officials report that, a few weeks into the war, Ukrainian companies got in touch to offer their UAV manufacturing services. In many instances, joint projects eventually led to the development or repurposing of drones for military use. Ukraine already had a solid foundation for a robust military-industrial base, having been a

Soviet-era weapons producer. But the pressure of the war to innovate, the ingenuity of the Ukrainian people, and the opportunity to work closely with experts from many Western countries look likely to help establish the Ukrainian drone industry as a serious international player once the war ends, able to export systems that are combat-proven.

Broadly, Ukraine has used drones to conduct three primary tasks: surveillance and intelligence gathering; propaganda; and strikes and strike coordination.

Surveillance and reconnaissance are the most natural use of drones. All drones carry photo, video, or other data collection sensors. These allow forces to locate enemy bases, observe troop movements, and other such vital tasks. In the months-long fight for the town of Bakhmut, Ukraine’s armed forces were reportedly able to conduct continual aerial surveillance of Russian positions, switching one UAV system for another when its batteries ran low: as one battalion commander said, “it’s like watching a nature movie. We watch them eat. We watch them talk to one another.” One video shows a drone following a Russian soldier, who leads it straight to the rest of his unit.

Closely linked to surveillance is the ability of drones to provide material that can be used for propaganda purposes. Photographs and videos from drones bring an international audience right to the front lines. They have documented the destruction of cities by Russian forces and the flooding of Ukrainian territory following the break of the Kakhovka Dam, and captured footage of attacks against Russian ships and tanks, men, and materiel. Many readers will have seen grenades being dropped with pin-point accuracy into the open hatches of Russian tanks; or the grainy video captured by a naval drone during its attack on the Russian fleet in the Sevastopol harbour.

Drone videos are well-suited for propaganda as they suggest a closeness and immediacy, yet create a distance for the viewer from actual deaths and injuries. Ukraine aims its propaganda-by-drone both at an international audience and at the Russian invaders. The footage demonstrates Ukraine’s abilities and successes to an international public, helping to maintain optimism and thereby support; it sends Russians, especially mobilised recruits, the message that nowhere is safe. Furthermore, Ukraine’s ministry of defence and intelligence services have launched an information campaign urging Russian soldiers to desert by drone, by surrendering to Ukrainian UAVs which then lead them to the armed forces.

Finally, as the propaganda videos show, drones are used to help direct and to conduct strikes. Ukrainian forces used armed military drones such as the TB2 at the beginning of the invasion to target the 64km-long tank convoy headed for Kyiv. TB2s have also reportedly been used to lure Russian fighters into the weapon-engagement zone of ground-based missiles. A TB2 drone may have distracted the defences of Russian flagship Moskva while naval missiles attacked and ultimately sank it. These systems have also been deployed to act as spotters for Ukraine’s Neptune anti-ship missile, locating targets for the missile battery to attack.

In the first weeks of the war, the failure of Russia’s convoy to reach Kyiv was largely due to ambushes by roving Ukrainian drone operators who supported special forces. The drone operators were drawn from Aerorozvidka, which comprises “technically aware citizens” who help the Ukrainian military with cybersecurity, situational awareness, and UAVs. The group first began its air reconnaissance work after the 2014 invasion and now employs various drone types for its tasks, including a self-developed system: the R18 octocopter. Ukrainian forces have used these multirotor drones to drop modified, often Soviet-era, grenades onto Russian equipment.

More important than these strikes by drone, however, is often the way drones can help to target artillery strikes, and thus help to minimise the number of artillery shells used. This is also a financial consideration: small commercial drone systems, such as those made by Chinese company DJI generally cost up to around €2,000, while a single artillery shell can cost more than double that amount – and might be more difficult to replace due to recent resupply problems. So, even if a drone is lost when used to increase precision for artillery strikes, it still makes logistical and financial sense to use it. In recent months, a growing number of first–person view racing drones have been used as kamikaze drones, piloted by specially trained soldiers via VR headsets.

Drones are also being used with increasing frequency (by operators unknown) to attack targets inside Russia, including Moscow’s city centre. In early December 2022, Russian airbases in Ryazan and Engels, about 480km from the Ukrainian border were struck by Ukrainian drones, possibly Tu-142. On 27 December, drones hit the Engels base again. Ukraine had previously used remote-controlled boat drones packed with explosives to attack Russia’s fleet off the coast of Sevastopol, and, in August, to target an amphibious Russian landing ship (although no official confirmation has come to light that the Ukrainian military conducted these operations). In August 2023, there were multiple drone attacks on Moscow.

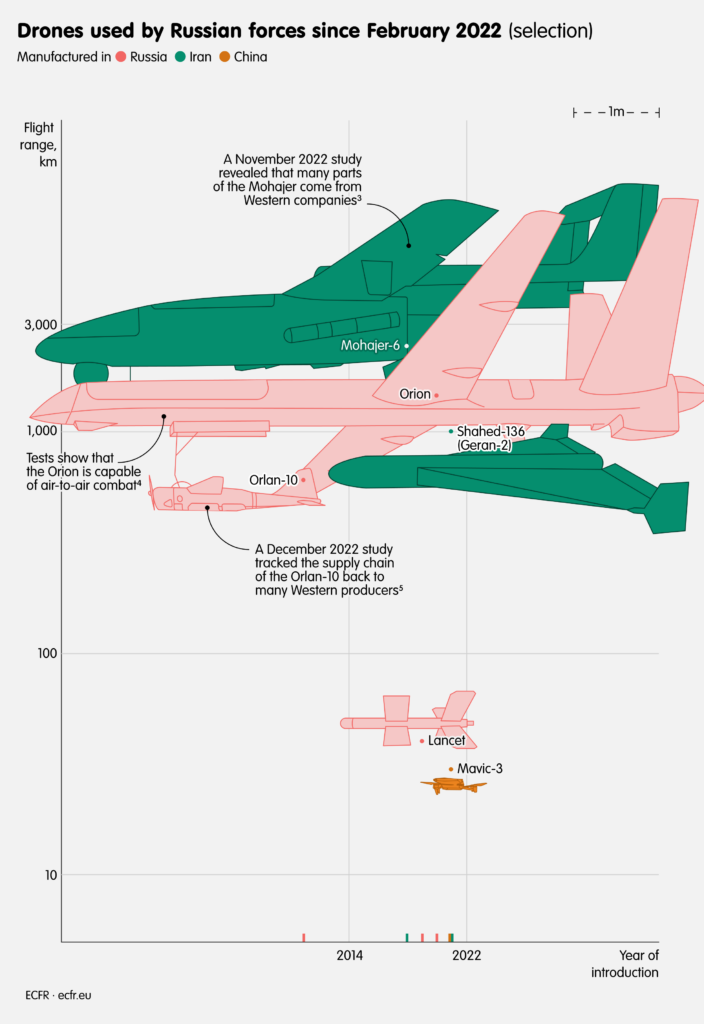

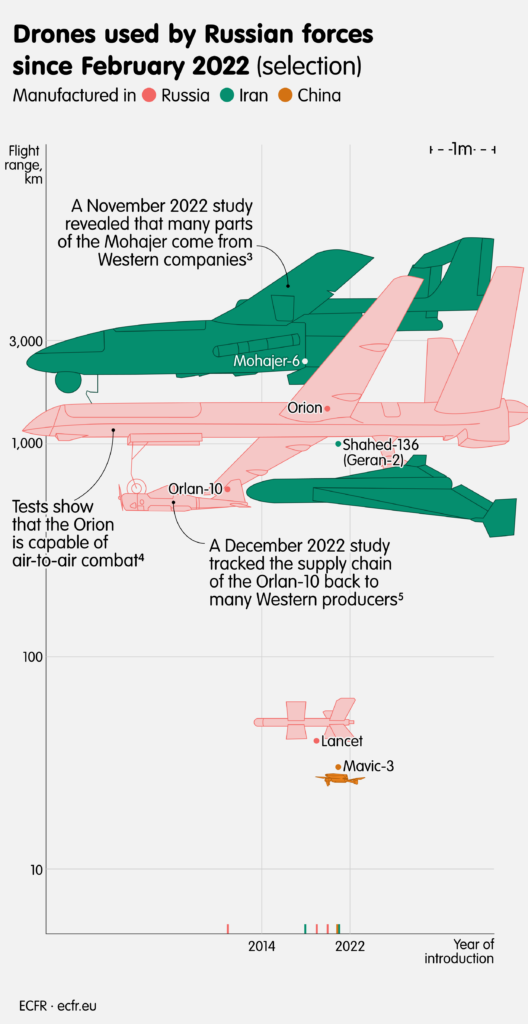

Russia has also used drones in its invasion, albeit less extensively and with less success than Ukraine. This is perhaps surprising, given the Russian command’s proclaimed UAV capabilities and plans, as well as its forces’ experience with drone warfare in, for example, the 2014 invasion of Ukraine.As recently as 2017, the chief of the Russian military’s general staff, Valery Gerasimov, had argued that combat was now “unthinkable without drones – they are used by gunners, scouts, pilots – everyone”.

“It is certain that Russia has all but missed the boat when it comes to cashing in on the worldwide drone revolution.”

Stijn Mitzer and Joost Oliemans, Oryx open-source intelligence, 2002

As of 2023, Russia allegedly has over 100 types of unmanned systems at different stages of research, development, testing, and implementation. But one extensive study of the Russian air war published in November 2022 did not find a great deal to report on drone use. Technology and defence expert, Sam Bendett, estimates that Russia began the war with some 2000 drones, but quickly had to top up with deliveries from Iran. Open-source intelligence platform Oryx, which has traced Ukrainian and Russian losses since the start of the war, noted that Russia’s attempts to catch up in this field may represent “too little, too late”.

Russian forces are using indigenous UAVs such as the Orlan-10 or Orion. The Orlan-10 system is Russia’s most frequently used surveillance drone, although it appears less often nowadays. This is probably due to Russia not having enough of the system to endure a longer conflict that it did not anticipate. It is also possible that this model was more vulnerable to Ukrainian air defences. The Orion is a more sophisticated combat UAV, recently developed by Russian manufacturer Kronshtadt, which has also been used for strikes in Syria. So far, Kronshtadt has only produced the drone in the low double-digits, limiting its impact on the battlefield.

Russia turned to imports to compensate for its limited numbers of indigenous UAVs (and successful Ukrainian countermeasures). In July 2022, US national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, warned that Iran was planning to send drones to Russia. By mid-September, the first attacks with Iranian Shahed-136 and Mohajer-6 UAVs had been recorded in Odesa. The Shahed-136 is a relatively simple and cheap weapon that Russian forces have deployed in large numbers alongside cruise missiles. US media reports that Russia aims to domestically build 6,000 Shaheds by summer 2025. Russian forces have also used Chinese-made drones, most notably DJI products, meaning the company’s drones feature on both sides of the conflict.

Russia has used drones in similar ways to Ukraine – for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, to find and attack targets, and, though less extensively than Ukraine, for propaganda purposes. Mostly, Russian forces use the Orlan-10 as part of an intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance complex: the drones locate Ukrainian troops and relay their positions for targeting by other means, such as artillery, thereby reducing response times to as little as three minutes from target detection. Russian units have also used Orlan-10s as decoys to unmask Ukrainian surface-to-air missiles, before suppressing them via electronic warfare to then destroy them with their own missiles or air strikes. Moreover, Russian sources suggest that the Orlan-10 has been used to send text messages to Ukrainian soldiers urging them to surrender.

But, differently from Ukraine, Russia has used drones with the specific goal of terrorising the Ukrainian population and destroying civilian infrastructure. In particular, it has used – and continues to use – barrages of Shahed drones combined with missile strikes to attack cities across the country. These attacks burden and deplete Ukrainian air defences, with the aim of ultimately retaking Ukrainian skies. Ukraine is now facing “the Somme in the sky” – a stalemate in which neither side has air dominance or even seriously attempts to penetrate deep into the other’s airspace. This is due to Ukraine’s air defence capabilities, which have turned the sky over Ukraine into an aerial no man’s land. The situation could change if Russia continues to deploy masses of cheap kamikaze drones and missiles, thereby eventually depleting Ukrainian stocks of anti-aircraft weapons.

Cyber warfare

In the hours ahead of its all-out invasion, Russia knocked out Viasat satellite networks, cutting off internet access for tens of thousands of Ukrainian citizens. The cyberattack also affected the communications of both the government and military. This fuelled predictions that the conflict could become the world’s first “true cyberwar”, not least because cyber assaults had been part of Russia’s hybrid warfare against Ukraine since at least the illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014. However, cyber operations in this war, although frequent, seem to have had only limited material impact on the battlefield.

“This is not a war just between Russia and Ukraine. It is a war between Russia and Ukraine that involves an alliance of countries that are supporting Ukraine, and an alliance of tech companies”

Brad Smith, president and vice chair of Microsoft, 2022

Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine increased the urgency of the country’s efforts to build up its cyber defences, in which it works closely with partners such as the United States and the United Kingdom, as well as the EU and NATO. Throughout 2021, US cybersecurity experts and nonprofit CRDF Global worked with Ukraine’s government to draft its national cybersecurity strategy. These partners have continued supporting Ukrainian cyber defence during the war, for example by helping to detect attacks and supplying equipment and software.

In the week before the all-out invasion, Ukrainian government agencies, with the support of some of the world’s leading tech companies, began moving their data and information into the cloud to ensure it was stored outside the country. Amazon supplied Ukraine with “snowball” devices – suitcase–sized computer storage units – to help store and transfer data, including the country’s land registries. By December 2022, it had helped move some 10 petabytes of data to the cloud – equivalent to several hundred thousand feature films.

Since then, technology giants have continued to assist Ukrainian cyber defence, providing software to protect against intrusion as well as sharing information about detected attacks. Google, for instance, expanded access to its free Project Shield software, contributing to an effective “cyber umbrella” that protects Ukraine’s websites from attacks. Microsoft alone has estimated its support to Ukraine in 2022-23 to be worth $400 million. Moreover, CRDF Global became a platform for the Cyber Defence Assistance Collaborative, an extensive network of US companies and organisations, which helped coordinate many of these efforts in cooperation with the Ukrainian government and critical infrastructure entities.

Finally, volunteer hacktivist groups inside and outside Ukraine, including Anonymousand the IT Army of Ukraine, have been targeting, for example, Russian government and media with cyberattacks in support of Ukraine, cheered on by Fedorov.

“[The quantity of Russian cyberattacks] is not decreasing, but their quality is … The Russians used up everything they had prepared at the beginning of the invasion: They didn’t expect this strong a defence.”

Brigadier General Yurii Shchyhol head of the state special communications service of Ukraine, 2023

Cyber operations have been a frequent feature of the war, with cyberattacks against Ukraine amounting to at least 470 documented cases over the past year. Their impact on the trajectory of the war itself, however, seems to have been limited. This is of course in big part thanks to the Ukrainian defence, but some factors on the Russian side could also help explain this.

Russian cyberattacks on Ukrainian government servers, critical infrastructure, and media have been intense. Examples have included defacement attacks, in which the attackers modify the visual appearance or content of a website, as well as denial-of-service attacks and the use of malware for wiping computer hard drives. But, despite their numbers, they largely seem to have failed or had no lasting impact on Ukraine’s military capability or the functioning of its society. Hacktivists with assumed links to the Russian government appear to have conducted some of these attacks.

Analysts have found little evidence that Russia has used cyberattacks for strategic military objectives. Examples of effective Russian use of cyber warfare in coordination with kinetic operations are few and far between. The one – and close to only – case, seems to have been the cyberattack on the Viasat satellite networks on 24 February. But its military impact remains unclear. For example, Victor Zhora, one of Ukraine’s top cyber officials, has claimed that military communications did not rely only on the Viasat networks for communication.

Other cases of seemingly coordinated cyber and kinetic operations include Russia’s targeting of the networks of Ukraine’s state nuclear power company, Energoatom, before the occupation of the Zaporizhzhia power plant that the company operates, as well as kinetic strikes and cyberattacks against Ukrainian power company DTEK in July 2022. However, some observers have suggested that the kinetic and cyber components of these attacks were neither coordinated nor served the same objective, rather just correlated in their timing.

The limited success of Russian cyber operations could be due to a lack of capacity, or perhaps willingness, among Russian forces to use them in pursuit of strategic goals. This is likely because the same goals can often be achieved more easily and cheaply through kinetic means: the numerous Russian air strikes on Ukraine’s critical infrastructure have caused far greater damage than their cyber operations. As Shchyhol set out, Russia also seems to have been unprepared to repeat sophisticated cyber operations in a long war scenario. It could, however, also be saving its capabilities for high-value targets outside the direct context of the fighting in Ukraine, such as infrastructure that affects the US or other NATO countries. It is also likely that Russia is simply benefitting more from using its capabilities for intelligence purposes than for offensive cyber operations.

Indeed, Russia seems to have used cyber operations primarily to attempt to influence public opinion, in Ukraine and abroad, and to gather information. It has also directed these towards Ukraine’s allies in the West. This is in line with Russian doctrine, which emphasises using cyber operations for exactly these objectives.

Software-defined warfare: AI, data, and apps

Software-defined warfare is ubiquitous in Russia’s war on Ukraine. It is, however, difficult to pin down: rather than the one attention-grabbing, headline-producing system, AI is helping to improve existing systems in myriad ways, in which applications programmed specifically for this war improve the capabilities of the armed forces on both sides.

“AI-enhanced weapons and systems are markedly different from conventional ones: the longer they are deployed, the more data can be collected to improve them directly.”

Robin Fontes and Jorrit Kamminga, defence and AI experts, 2023

Ukraine has embraced the digital battlefield. Data collection, fusion, and analysis has been a crucial element of Ukraine’s successful defence in the first year of the war. New software and AI help upgrade the existing functions of legacy systems. AI is being used in drone operations to automate processes such as take-off and landing. Automated processes are also used in target acquisition, after which humans are notified to confirm the selected targets and the information automatically sent to the Ukrainian battle management system. Through this process, the sensor-to-shooter loop – the time from detection of a target to its destruction – has been reduced to just over 30 seconds. According to Palantir CEO, Alex Karp, the US data analytics firm is highly involved in improving the targeting functions, from tanks to artillery, and is “responsible for most of the targeting in Ukraine”.

Data analysis is another crucial type of AI-enabled system. Firms such as US data analysis specialists Primer are using natural language processing technology to capture, transcribe, translate, and analyse Russian communication. European military AI-developer Helsing is working with Ukrainian armed forces on the analysis of satellite images, vastly accelerating processing times. Similarly, US firm Scale AI uses machine learning to analyse imagery of Ukraine. This helps Ukrainian forces understand where attacks are happening and assess damage more quickly and accurately than human reporting would allow. German startup transversals is analysing publicly available data, such as from social media, from close to the Ukrainian front line. AI provides translation, combines data with metadata, geo- and time-locate information and more. Ukraine has thus significantly increased its battlespace awareness. Moreover, software-defined warfare has made the use of strategic assets, such as satellites, or high-flying drones, so straightforward, that they have become tactical in their nature.

Facial recognition is also in use. US firm Clearview has worked with the Ukrainian defence ministry, which uses the company’s technology to identify deceased Russian personnel through their social media profiles in order to notify relatives of their deaths and transfer their bodies to the families.

“Now it is necessary to ensure the introduction of artificial intelligence [AI] technologies in weapons that determine the future appearance of the Armed Forces.”

Sergei Shoigu, Russian minister of defence, 2021

The Russian leadership was enthusiastic about AI in the years leading up to the all-out invasion. Yet, its capacities may not match its ambition due to a combination of technological lag, brain drain, Western sanctions, and international isolation. Only limited information is available on Russian use of AI-enabled software, but so far, there seems to be no clear evidence of much – if any – advanced Russian AI in decision-making among forces in Ukraine.

In June 2023, Russian-language Telegram channels reported that AI-enabled capabilities were used on Lancet-3 loitering munition to analyse imagery and video data, but such claims are difficult to verify. Bendett notes that there is a gap between what the Russian military leadership claims regarding its AI capabilities, and the actual practical results in Ukraine. Moreover, fears that Russia may use deep fakes – AI-altered or generated videos – to sow confusion, have also not materialised: one fake video purported to show the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, surrendering to Russia, but was quickly debunked.

Space

Space has become more accessible over the past decades, particularly with the emergence of the private space industry, or the “new space”. Commentators, in turn, have described Russia’s war on Ukraine as the first “commercial space war” – the Gulf war in 1991 being the first “space war” – with the world able to follow the conflict almost in real time via commercial satellite imagery. It is also the first war in which both parties have used space capabilities. Russia seems not to have used the full potential of its space-based assets, but the space dimension has proven to be more important for Ukraine.

“Starlink today is the backbone of Ukraine’s military communications.”

Elon Musk, SpaceX CEO, 2023

Space has been crucial to Ukrainian communications, mainly due to the Starlink-satellites of American company SpaceX, which provide access to high-speed internet. “Starlink is indeed the blood of our entire communication infrastructure now,” Fedorov said in one interview. Over 30,000 Starlink terminals were delivered to Ukraine in the first 15 months of the war, providing secure communications to the military as well as the government and the public. Starlink has proven to be relatively resilient and has resisted or countered cyberattacks and jamming. Shchyhol has acknowledged it as the most useful digital assistance the country has received. Beyond the immediate military use, the fact that Ukraine has not been cut off from the world thanks to satellite communications has had a great strategic impact. Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky has held virtual meetings with world leaders, stayed very active on social media, and Ukraine has been able to counter the Russian information campaign.

War of the memes

Internet connectivity has not just been important to Ukraine’s leaders and for the military efforts of its armed forces. Information warfare has always mattered, but the immediacy of social media has created a new environment. One of the more unexpected ways supporters of Ukraine outside the country are showing their support is through NAFO, the “North Atlantic Fella Organisation”. The group, whose name is play of words on NATO, uses social media and meme culture to bring together supporters of Ukraine from all over the world to take on Russia’s propaganda machine, primarily on Twitter. NAFO fellas use as their avatars customised images of “doge”, the Shiba Inu that became an internet meme. Fellas take on Russian disinformation accounts, challenging the often-absurd claims of Russian officials with humour and ‘shitposting’. They have flooded Twitter with memes making fun of Vladimir Putin.

The organisation is deeply embedded in internet culture, and many of its references may be opaque to outsiders. But NAFO’s efforts have contributed to creating an information environment in the West that is favourable to Ukraine. The group also has more serious facets, such as supporting crowdfunding efforts, with a customised cartoon doge often involved in donating to Ukrainian organisations. NAFO includes journalists and politicians; the chief of Ukraine’s army has been spotted wearing a NAFO patch. UNITED24, a fundraising initiative by the Ukrainian president, in March 2023 called for donations to buy first person view attack drones, the “Flyin’Fellas SquaDrone”. Without the use of space assets, the considerable morale boosting and fundraising efforts of NAFO may not have taken off nor reached people inside Ukraine.

The Ukrainian military has also made extensive use of space-based assets for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. Ukraine has been relying on space-based positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) technology to conduct precision strikes on key targets, and early warning radar has been able to track the launch of ballistic missiles. To a large degree, Ukraine has been relying on the assets of private (mostly American) tech companies. Ukraine has again been using Starlink satellites to guide drone strikes. Companies such as HawkEye 360, which specialises in radio frequency monitoring, have been able to track Russian GPS jammers. Satellite imagery from Maxar’s synthetic aperture radar (SAR), which provides images at night or in poor visibility, not only informs the government and military, but was also shared by the company with media outlets, with the images featuring frequently in their reporting.

Moreover, non-US space-assets used by Ukraine include the Argentinian earth observation company Satellogic, which provides high-resolution imagery, and Finnish ICEYE’s SAR satellite. The Ukrainian military has reported significant success in using ICEYE, claiming that the damage caused to the Russian military in the first couple of days of the use of its data had already exceeded the cost of the purchase.

Ukrainians have also used commercial satellite imagery to shape public opinion and for other strategic communication purposes. It has been fundamental in countering disinformation. For instance, just before the onset of the war, when Russian troops were building-up along the Ukrainian border, people around the world could see what was going on, despite Putin’s denials.

Satellite imagery has also been used to document potential Russian war crimes, such as in the Ukrainian city of Bucha, and to identify mass graves. This is the first major conflict in which the media has had widespread access to information that was previously only available to military intelligence services. This has also made those services more open to sharing their own material, as much of the information is already publicly available.

“Despite the long history of Soviet and Russian spaceflight, it is not obvious that the Russian military has benefited more from space than the Ukrainian side.”

David T Burbach, professor of national security affairs, 2023

Russia has access to all the functions that could make it a great space power – including a wide range of satellites for communication, PNT, ISR, and early warning. However, its use and the impact of these capabilities in this war have so far been modest. Even if Russia has been using space-based PNT for precision strikes, for example, its air-launched cruise missiles seem to be missing their targets. This implies that Russian forces are unable to use PNT effectively for targeting with precision. Moreover, media reports suggest that Russian forces’ communication systems do not function well, meaning that the Russian military has relied on unsecured communication devices such as radio and mobile phones instead of encrypted military satellite communications.

Some observers expected the Russian military to interfere with GPS in Ukraine to a far greater extent than it has so far, and are now discussing whether this is a capability issue or a tactical choice: some Russian troops rely on GPS, rather than the Russian equivalent GLONASS, so there is perhaps little benefit in disrupting it. Moreover, the Soviet-era equipment Ukraine has been using is not dependent on GPS, so would not be affected anyway.

Neither has Russia used its kinetic anti-satellite weapons, one of which it successfully tested against its own satellite (to widespread condemnation) in 2021. To the authors’ knowledge, there have also been no verified instances of Russia using its Peresvet anti-satellite system, which could use lasers to blind or destroy reconnaissance satellites. One explanation might be that the numbers of satellites are simply too great for kinetic attacks to be worth conducting. Instead, Russia has stuck to cyberattacks and jamming attempts, which have the advantages of both being difficult to attribute and operating in the grey zone of what constitutes an act of war.

Some analysts have also made the case that the limited use of space is in line with Russian doctrine, which assumes that space-based assets will be jammed or spoofed during war, and Russian forces thereby plan for the use of other capabilities. Some experts, such as the US Space Force’s Major General Leah G Lauderback, posit that Russia is very capable in using its space assets, but that it is simply less dependent on space for fighting a war than, for example, the more technologically advanced US. There are, however, also well-known structural issues in the Russian military, negatively affecting both equipment and training, which have a big impact on its ability to use complex space-based systems.

Lessons for Europe and beyond

It would be unwise to make definite assertions based on the information of an ongoing conflict. Information regarding the war in Ukraine remains incomplete, and, as in any war, it has idiosyncrasies that are unlikely to be repeated exactly in future conflicts. It is primarily a land war; at the time of writing, manned aerial systems have largely been neutralised due to air defences. It is a materialschlacht – a fight in which enormous numbers of Soviet-built tanks, artillery, and ammunition are being thrown into combat.

Equally, the material support that Western allies are providing for Ukraine – as well as the fact that both warring parties have a hinterland (the Russian territory in the case of Russia; some parts of Ukraine as well as neighbouring partners in the case of Ukraine) that they can use to safely transfer materiel, base key infrastructure, or manufacture and service equipment – are not circumstances that can be assumed to be present in a future military confrontation in which Europeans might find themselves.

Nevertheless, Europeans can draw some lessons from this conflict. Our analysis shows that several emerging technologies are playing a crucial role in the war. They are changing the context of the fighting, its speed, and they involve new actors. Europeans should take the following four observations into account as they draw on the experiences of the war so far.

Lesson 1. Private technology companies are playing an ever more important role in warfare

Private – and mostly civilian – technology companies have provided crucial systems and services to Ukrainians and their armed forces throughout the war. The most visible roles for these companies have been in internet connectivity, and in the cloud computing and cyber field. Other companies have provided hardware, such as drones, or software to improve legacy systems.

From the outset of the full-scale invasion – and in some cases before – Western companies took the decision to side with Ukraine. They suspended (some of) their operations in Russia (also to comply with sanctions), and actively helped Ukraine in its fight – often without charging the Ukrainian government for the equipment and services. A representative from one company noted that supporting Ukraine was part of their vision and mission.[1] But, operations in Ukraine are also a way for companies to showcase their products and capabilities to future customers. Details, however, tend to be scarce as companies do not want to endanger the ongoing war effort by disclosing too much information as to the exact nature of their operations.

The Ukrainian government appears to have been particularly successful in dealing with private companies, creating relationships that they have been able to rely on during the war effort. Representatives from several companies have noted how easy it has been to work with the Ukrainian government and how responsive officials were.[2] In April 2023, Ukraine launched the “Brave1” portal to further facilitate public–private innovation.

Private companies’ operations in Ukraine are thus underlining the potential for governments of working outside an exclusive military procurement. The rapid deployment of Starlink terminals, for example, highlighted the advantages of commercial systems compared to military systems: they are relatively cheap compared to military or government satellites and are quicker to produce and deploy. They also often already exist in large numbers off-the-shelf. This has been especially the case for civilian drones, which are being used in the tens of thousands. They can easily be bought, including by individual supporters, and straight away be put to use. Amazon was able to rely on existing logistics chains to help transport the snowball devices for its cloud

operations. In consumer-facing areas, private capacities are superior to those of states; as one executive put it in a private discussion: “We have a cybersecurity team working at any moment of any day. States just cannot offer that.”[3] Equally, it is unclear whether any state could even have provided the same level of internet connectivity as Starlink.

The EU and some European institutions have already taken some lessons from the war in this regard. At the meeting of the European space agency (ESA) in November 2022, officials highlighted the importance of Europe’s independent access to space, including for secure communications and rapid and resilient responses to crises. Member states approved a €16.9 billion investment in support of this by 2026. ESA officials have also emphasised the need to invest in commercial growth areas, including European start-ups, as well as to reform the agency into one that buys services instead of developing systems, in line with the market-led design that resulted in SpaceX. In addition, the European Commission and the European Investment Fund are making available €1 billion over five years for space entrepreneurship through the CASSINI initiative.

But working with commercial providers also creates vulnerabilities. Earlier this year, SpaceX reported that it had taken measures to limit Ukrainian military use of Starlink, arguing that the intention had never been for the service to be used for offensive military purposes. The New York Times revealed in July that, at times, the Ukrainian armed forces changed their operations because of Musk’s decisions on when and where internet connectivity via Starlink was available.

In October 2022, Musk demanded financial compensation from the Pentagon for the costs of the terminals and connection service. Both Ukrainian and US officials questioned this demand – not least because a large proportion of Starlink’s activities in the country were already financed by Ukraine’s allies, as well as through crowdfunding and private donations. According to numbers shared by SpaceX with Pentagon, around 85 per cent of the terminals and 30 per cent of the connectivity costs were paid for by allied countries, notably Poland and the US. Musk later withdrew the request for funding.

These episodes were stark reminders that commercial actors operate within a market logic and that their bottom line could have a significant impact on the trajectories of wars. Moreover, some media speculated that Musk’s actions were a direct consequence of his alleged ties to Moscow. Whatever the validity of this assertion, it highlights another dimension of complexity related to dependence on decisions made by individuals outside democratic control and accountability.

At the same time, private companies cannot necessarily control who uses their products and for what purposes. The Chinese drone manufacturer DJI suspended operations in both Russia and Ukraine early into the war. But the company’s drones remain common civilian systems on the battlefield. Openly available software, such as Clearview’s facial recognition tool, can be used by all and for purposes that the firm might not condone (for instance, targeting) without the company being able to restrict its use.

Recommendations

European governments need to recognise the important role private companies will likely play in future conflicts. They should enhance public-private partnerships on crucial technology services and establish regular exchanges with companies.

European states should regularly include commercial systems, equipment, and even actors in their military exercises. They need to learn from Ukraine how new, off-the-shelf systems can be integrated into the military with minimal bureaucracy and immediate impact, which is not the

case in European military procurement today. Private actors that we spoke to for this research emphasised the speed and ease of communication with their Ukrainian counterparts: “We did things in six weeks which would have taken months or years elsewhere”, one company representative said.[4] Peacetime procurement can – and should – never try to match the procedures of the extreme situation of an existential war. Still, Europeans should rethink their procurement processes to ensure they can quickly reach wartime levels if so required. This also means establishing relationships and communication with companies that do not exist today but that can be relied upon in a time of need. An official platform like Brave1 might be an option for Europeans too.

However, European governments need to give careful thought to how to regulate cooperation with commercial actors. They should consider how to define the requirements and procedures for the military use of commercial products. It will be crucial to ensure that they design public-private cooperation to protect national security and defence interests, and that they are not vulnerable to the whims of CEOs or boards, or to the market logic of commercial actors. US policymakers are already working to enhance partnerships with commercial companies on space-assets. They are also examining how to design agreements to ensure their full availability in times of conflict under a new Commercial Augmentation Space Reserves initiative. Although the US is a great space power with very different capabilities from European countries, the EU and its member states should study their most promising ideas and designs.

European governments equally need to support the development of European commercial solutions, especially in light of efforts to increase European sovereignty. Although the US is a close partner to Europeans, they should not assume that in any future conflict US companies would as a matter of course work with them. One promising development in the space sector is the proposed joint venture between French satellite company Eutelsat and British OneWeb, which would create a stronger European competitor to SpaceX’s Starlink and Amazon’s Kuiper. The EU, ESA, and European institutions should continue to support initiatives such as this within the market-led design model. On commercial drones, European, as well as American providers, are hopelessly behind Chinese companies. If Europeans do not want to be dependent on China in this area, it may be necessary to financially support nascent drone companies or limit the import of cheap Chinese systems.

Governments also need to consider the extent of the responsibility they should assume in protecting commercial systems and their producers. For example, governments providing indemnification to private actors has been discussed as a prerequisite when signing contracts with commercial companies.

Private companies should also take lessons from the war. Firms should already be preparing for the possibility that their products, if relevant, may be used in a future conflict. Russia’s aggression and gross violation of international law left little need for debate as to which side to support. But, in future confrontations, things may not be so clear cut – especially if there are commercial interests on both sides. Therefore, companies need to define procedures on how they will take such decisions.

Furthermore, private companies need to prepare for their products, and potentially even their staff, becoming targets in future conflicts. The above-mentioned cyberattack on Viasat is a case in point. Russia has already declared that it considers private satellites to be legitimate targets for retaliation in wartime. This means that private actors might think twice before they agree to provide their services to governments and the military. Others have little control of how their

products are used: both sides in the war in Ukraine reportedly jailbroke the DJI operating system to change the location data it broadcasts.

Finally, companies providing services for military purposes will need to boost their security systems to withstand, for example, cyberattacks. Commercial systems have so far not been subject to the same level of cybersecurity requirements as those of the military and are – by definition – not built to sustain that level of attack. At the European level, measures are already being taken in this direction, with EU regulation already in place to strengthen security requirements for a broad range of commercial products. Moreover, the EU’s secure connectivity programme, “Infrastructure for Resilience, Interconnectivity and Security by Satellite (IRIS2)”, will take military needs and requirements into consideration.

Lesson 2. New technologies can enable and motivate individuals’ participation in warfare

Among the most novel aspects of the war in Ukraine related to new technologies is how they have enabled and motivated the involvement of individuals. Military experts Jahara Matisek, William Reno, and Sam Rosenberg, have termed this phenomenon “informal security assistance”.

Of course, the involvement of ‘the people’ in war has been a topic for discussion for hundreds of years. Prussian war theoretician Carl von Clausewitz, for example, famously wrote about the trinity of the government, the military, and the people. European governments issued war bonds during both world wars, asking their populations to contribute financially to the war efforts. But, with the hyperconnectivity of social media, this dimension appears to have reached a new level – and there is no reason to assume this will not also be a topic for future confrontations.

Ukraine has taken a “full-nation” approach to the war. Ukrainian civilians had little choice as to their involvement since their houses are being bombed and their critical infrastructure destroyed. Still, even before the 2022 invasion, Ukrainian civil society and individuals were already actively involved in the country’s defence. For example, Aerorozvidka relies on public donations via its website and social media accounts. Ukrainians also send tips to the military regarding advances of Russian forces and incoming Russian missiles through apps or Telegram chatbots. The Ukrainian government has created a website and app where people can testify on Russian war crimes.

It is not only civilians in Ukraine who have been involved in the war efforts. New technologies have also made it possible for individuals abroad to get involved. Ukraine’s resistance has attracted thousands of foreign fighters from around the world. Independently of their location, people were able to appreciate the situation in Ukraine – also thanks to myriad drone videos and satellite imagery posted on social media.

Moreover, technology has allowed those who cannot or would not go to Ukraine to support the war effort from afar. A multitude of international crowdfunding efforts support Ukraine’s troops, often with the backing of celebrities. They are organised via social networks, allowing money to be sent via platforms such as Paypal, or use bitcoin – and have collected funds to buy equipment such as drones and Starlink terminals. Collections have come from countries as close as Lithuaniaor Poland, and from those that are oceans away, such as Canada. Baykar, the Turkish manufacturer of the TB2, which many of the crowdfunding efforts aimed to buy, responded to these efforts more than once by providing Ukraine the drones for free and suggesting donating the collected money to humanitarian aid organisations. Ukrainian soldiers told researchers that the collective effort to buy TB2s at one point was so extensive that it created supply-side issues. Russian troops reportedly also fundraise money for drones, especially smaller quadcopters, over Telegram and other social media channels.

Cyber vigilantes have conducted cyber operations in support of the war – on both sides – more or less encouraged by state actors. Amateur investigators use open-source intelligence tools such as facial recognition, geolocalisation tools, and more to help the side they support. As Matisek, Reno, and Rosenberg note, commanders or prisoners of war once appeared as anonymous faces in news reports, recognisable only to those close to them or to intelligence services. But anyone anywhere can now attempt to track them down.

Recommendations

Europeans should begin to consider how to deal with an engaged citizenry in the context of a war. This will be an important challenge, especially in European democracies, with a free and open internet and where public opinion matters. Involved citizens are an overall positive development, but can add to polarisation, be instrumentalised by opponents, or lead to pressures that could hamper international diplomacy.

European states should be proactive and establish mechanisms to coordinate and make use of civilian volunteers who can boost capacities. One promising example is to cultivate individuals’ involvement in cyber defence (as opposed to attack), to engage individuals who might otherwise conduct cyber vigilantism with little positive impact on military strategic goals. The idea of using civilians as an intelligence resource, through chatbots or other means of sending in information, might also be an option for Europeans.

Europeans should also take lessons from Ukraine in how to win over individuals and direct their engagement in a positive way. The Ukrainian leadership has been impressive in adopting the light, sarcastic tone of the internet in its own communications on social media platforms, all the while never losing sight of the severity and tragedy of the situation. The government has succeeded in using these efforts to their advantage – without ‘officialising’ them too much and thus destroying the elements that make them ‘cool’. The ability of Western governments, or the EU, to behave similarly is open to question.

Lesson 3. Quantity still matters

The war in Ukraine has been a reminder that, while modern technology can bring advantages over older systems – think of the debate around Western tanks and aircraft – quantity still matters. As former Estonian president Kersti Kaljulaid succinctly put it: “there is no point in having one fancy weapon if the enemy has 10,000 non-fancy ones.”

Mass has been an important characteristic of this war, which has in part been a sheer materialschlacht. As the successor of the Soviet Union, Russia has been able to field unheard of numbers of systems, most notably thousands of tanks. Ukraine, thanks to the support of Western allies, has equally thrown impressive numbers of weapons and ammunition into the fight. The war has called into question Western military-industrial capacities, with Ukraine at times using more artillery rounds in a month than all European manufacturers can produce in an entire year.

But new technologies have also appeared in mass: Russia has used hundreds of kamikaze drones to saturate and overwhelm Ukrainian air defences. One recent study estimated that Ukraine loses up to 10,000 drones per month – most of them non-hardened civilian systems. With Ukraine planning to manufacture 200,000 drones over the next year, and Russia aiming to build 6,000, it appears that even “fancy” weapons now need to be procured in high numbers.

Another area where the effect of using commercial systems is evident is their contribution to resilience – both in offering a diversity of systems and, in the case of drones or satellites, in their sheer number (hundreds or even thousands). This means an attacker would have to disrupt several different systems and a large number of targets to have a significant effect – as opposed to hitting a small number of high-value military targets which might be harder to replace.

Also, in the cyber domain, lessons from Ukraine suggest that the cyber threat Europe would face in a war may not necessarily comprise sophisticated attacks targeting high-value military installations, but rather one of cruder yet relentless attacks on civilian infrastructure, such as governments and critical infrastructure, mainly for intelligence and influence purposes.

For Western armed forces, the insight that mass still matters is particularly relevant. Over the past decades, these forces have begun to focus on technologically advanced systems that are becoming so expensive only a small number of them can be bought. We may not quite yet have reached the stage of the 1983 prediction by the former CEO of Lockheed Martin, Norm Augustine, who joked that, given rising costs for fighter planes, by 2054 the entire US defence budget would only be able to buy one jet – and the army, air force, and navy would have to share it between them. (The marines would get it for a day in leap years.) But Augustine’s hyperbole was not that far off.

The US F-35 aircraft programme is the world’s most expensive weapons programme, costing the US some $400 billion. Europeans are currently building a future drone system which, depending on how one calculates, will come at an eye-watering price of €200m per aircraft.

Recommendations

Europeans would be well advised to consider the acquisition of higher numbers of more expendable systems. Here, again, working with the private sector could be beneficial. Governments should devise plans to ramp up production, possibly relying on commercial abilities. The ease of replacing systems or parts needs to become a higher priority.

This is in particular a topic for drone procurement. As discussed, Ukraine is reportedly losing up to 10,000 drones a month and has dozens if not hundreds of different systems in use. To compare, the German Bundeswehr has six different drone systems in use, several of which it only owns in single digits. There is no drone system of which the German armed forces have 100 units or more. All European armies will need to procure higher number of drone systems in the future, and develop drones that are cheap enough that they can be lost and easily replaced.

This is also a topic for the cyber realm, where physical mass plays less of a role. Military cyber commands should not narrowly focus on defence against attacks targeting high-value military installations. It is equally important for them to develop coordinated military and civilian cyber defence that can sustain a longer war of attrition and fend off high-volume attacks against multiple targets.

This should enable states to defend against attacks on government services and civilian critical infrastructure, and protect their intelligence operations. European cyber defence actors – military and civilian – should therefore ensure resilience in maintaining a high level of defence for a prolonged period of time.

One way for European countries to enhance their cyber resilience is to boost their national reserve capacities for cyber defence. Indeed, some existing models could prove useful. In Estonia, the Estonian Defence League’s Cyber Unit is a voluntary organisation aimed at protecting information infrastructure and the broader objectives of national defence. Similarly, France has a cyber reserve force, and in Sweden the Total Defence system entails that people with key functions in society (including cyber security) are obliged to fulfil their duties also in times of war.

Lesson 4. It’s not (just) the technology, it’s how you use – and integrate – it

The war in Ukraine provides yet more evidence for that old adage of military studies: what matters for new technologies’ success is the integration of the system into the military organisation. “Combined arms warfare” is a term that 18 months into the war has almost broken into the mainstream. It describes the “deadly ballet” that is the interaction between different weapon systems and the way they are directed by command and control.

The Ukrainian military has shown to be a rather good ballet choreographer. It has proven itself able to integrate new systems and technologies into its operations and exploit their potential as much as possible. For example, Ukrainian forces used modern HIMARS rockets to strike Russian command-and-control nodes and radar systems. This created gaps in Russian air and missile defence umbrellas, which Ukrainian drone operators could then exploit using TB2s. New technologies also helped to make this coordination possible. Starlink terminals held up connectivity, which allowed intelligence from drones and spotters to be shared and analysed in real-time.

As one technology specialist in the Ukrainian military said, “It’s called connected war, and the Ukrainian army will be the most advanced ever because of life experience.”

Recommendations

The insight that weapons integration is crucial should not surprise European military commanders. Nevertheless, the war is an important reminder that European militaries need to consider weapons integration from the very beginning of the development of any new system.

Conclusion

The war in Ukraine has not ended,and, at the time of writing, the Ukrainian counteroffensive is under way. This paper therefore provides just a first overview of how emerging technologies have been used in this war so far. Countermeasures could change the relevance and impact of certain weapon systems (such as drones), and new uses of technologies might be developed.

Even so, this paper shows that there is still plenty for Europeans to learn amid the uncertainty. They need to draw on the outsized influence of private companies in this war – from US tech giants to smaller firms, and the coordination and collaboration between them and the Ukrainian state. Without that, Ukraine’s data would never have made it to the cloud, its battlefield could have remained largely analogue, and its high technology and cyber defences considerably more limited. Starlink internet terminals ensured connectivity for Ukraine’s armed forces, government, and population, which has been exploited to great effect by all. States need to respond to this increased power for private firms and their changing relationship with them. For their part, private companies need to rise to the challenge of their likely greater role in future geopolitical confrontations.

Yet, despite all this, European militaries need to remember the basics: mass matters, and all the shiny tech in the world cannot compensate for a lack of integration and choreography. Finally, governments need to prepare for the enabling nature of new technologies in informal security assistance, and acknowledge that controlling and channelling the engagement of individuals will be a key challenge in future conflicts.

In Ukraine, the most impactful new technologies so far have been drones and space assets, as well as cyber and software-defined systems. It is likely that these will also play a role in future conflicts – but, especially in the AI-enabled field, many more developments are likely. The broad lessons of this paper, however, should stand for both future conflicts and future technologies.

[1] Comments from tech company representative, debate held off the record, online, June 2023.

[2] Authors’ interviews with tech company representatives, held off the record or under Chatham House Rule, Stockholm and online, June-July 2023.

[3] Authors’ discussion with tech company executive, held off the record, Stockholm, June 2023.

[4] Comment by tech company representative, discussion held off the record, online, June 2023.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.