So far from god, so close to Russia: Belarus and the Zapad military exercise

Summary

- Fears that Russia may use Zapad 2017 as cover to carry out a hybrid operation in Belarus are overblown. Moscow has other levers with which it can coerce Minsk, and it neither needs nor is interested in another military adventure at the moment.

- President Lukashenka realises that relying solely on Moscow is dangerous and wants instead to diversify his strategic options by inching closer to Europe. But there are limits to how much Lukashenka can, or even wants to, approach the West. His survival depends fundamentally on maintaining an economic lifeline to Moscow. He knows that taking significant amounts of Western money comes with requirements of structural reforms that would undermine the basis for his rule.

- The European Union should support the gradual strengthening of Belarusian sovereignty, build further links, and step up engagement. This will bring Belarus closer to the West, as well as create more opportunities to influence Minsk on human rights and democracy. A policy of isolation would only push Belarus further into Russia’s tight embrace.

Belarus, Sometime in the Near Future –

A roadside bomb explodes in the swampland of southern Belarus. A score of Russian soldiers taking part in the Zapad 2017 exercise are killed, prompting a sharp and immediate reaction in Moscow. The Kremlin declares the attack an act of aggression and a provocation against Russia. The Russian General Staff calls a halt to the exercise and sends several platoons of Spetsnaz – which were conveniently already in Belarus – into the swampland to track down the terrorists. A dozen extreme right-wing Belarusian nationalists are eventually killed and a handful captured. Interrogations by the GRU, the Russian military intelligence agency, supposedly reveal a larger plot to overthrow the Belarusian president, Alyaksandr Lukashenka. State-run Russian television says that the coup-makers were planning to install a fascist junta with the support of an unnamed neighbouring country. Russia immediately sends troops to Minsk to provide security and reassurance for the people of Belarus.

After a few weeks, the Russian troops eventually withdraw from the capital to occupy the long-mooted air base at Babruisk. A fleet of Su-34 fighter jets is deployed to the base as a signal to the unnamed neighbour that Russia will punish any further attempts to destabilise Belarus. Lukashenka has hardly been seen in public since the terrorist attack, having been immediately provided by Moscow with a team of Russian military and political advisers to ‘help’ him manage the crisis.

In the wake of the attack, Russia decides to make permanent the forward deployment of 75,000 troops to its borders with the Baltic States, Belarus, and Ukraine. It justifies this move as a stabilising measure to deter any further attempts to overthrow regimes allied to it.

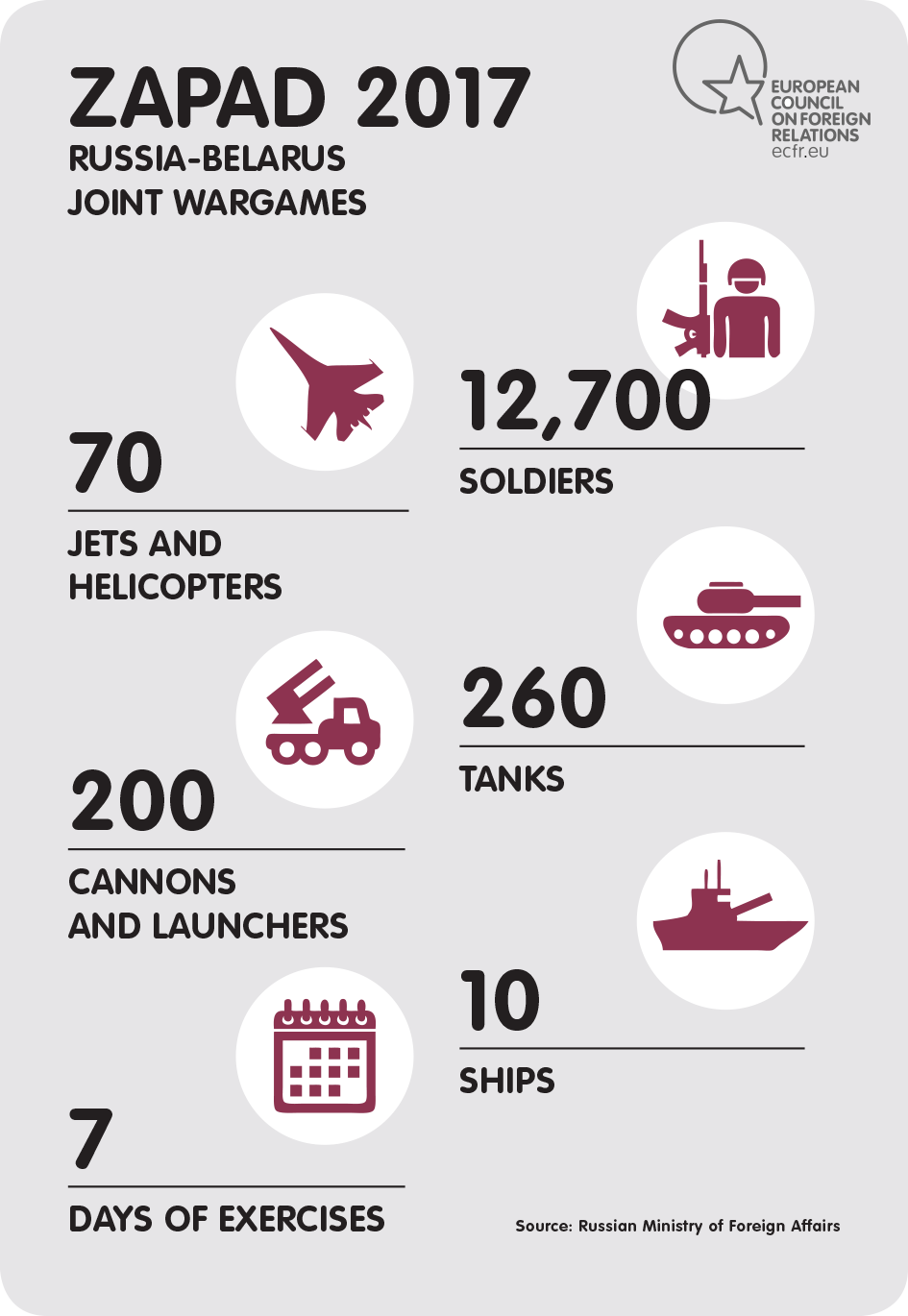

Russia’s Zapad 2017 military exercises have unnerved many countries, both in the neighbourhood and further afield. The fear that Russia could use the exercises to force Minsk to accept a military presence in Belarus was further fuelled by indications that Russia was planning to use 4,000 train cars to transport men and equipment directly into the country for the exercise.[1] This figure suggested Russia was sending many times the declared number of 3,000 troops to Belarus. Lieutenant General Ben Hodges, commander of the US army forces in Europe, has expressed his fear that the exercises will be a “Trojan Horse” designed to leave Russian forces behind in Belarus.[2] Both Russia’s war with Georgia in 2008 and the annexation of Crimea in 2014 were preceded by Russian military exercises. Could Zapad 2017 be a maskirovka – a deceptive campaign – for making Russia’s longstanding demand of an air base in Belarus a reality?

Or will Zapad 2017 be used to increase the pressure on Ukraine? In June, Ukrainian defence minister Stepan Poltorak claimed that it could “be used to launch aggression not only against Ukraine, but against any country in Europe that has a common border with Russia.”[3] And at least one neighbour has called the drill a “simulated attack” on NATO in the Baltic region.[4] Nearby countries fear that Russia will simply use the exercise to reinforce its military presence along its borders with Ukraine and NATO.

Belarus is central to this drama. Minsk has been testing the limits of how far it can distance itself from Moscow and rebuild relations with the West, which were frozen between 2010 and 2016. Belarus has released its political prisoners and sought to engage with the European Union, while rejecting Russian demands for an airbase and staying neutral in the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. However, Lukashenka and Vladimir Putin seemed to patch up most of their differences at a summit in St Petersburg in April 2017. So how much has really changed between Belarus and Russia? How real have the tensions been? How far is Lukashenka able to turn to the West, and is he really interested in doing so? The key to answering all of these questions is to understand that Lukashenka is still a dictator and his priority is his own survival.

The Zapad story

The alarmist scenarios for Zapad 2017 show the significance of, and difficulties produced by, the broader context of Belarusian foreign policy. Regardless of the outcome, they reveal both the constraints on Belarus’s freedom of manoeuvre, and its desire to maintain that freedom – and the limits to Belarus’s ‘strategic hedging’ between Russia and the West.

On the one hand, the number of front-line Russian troops on Belarusian soil during the exercise, at least according to official Russian figures, will be limited to about 3,000.[5] As one commentator has pointed out, “This is not enough to occupy the country.”[6] And, in defiance of Russia, Belarus has made a point of inviting international observers, even though it is not required to do so by the Vienna Document. This seems to be Belarus’s attempt to show that it does things differently from Russia. On the other hand, the Zapad 2017 exercise inside Russia may involve up to 150,000 Russian troops, once reservists and the National Guard are included. According to one Belarusian analyst, this is on “a scale comparable to the biggest exercise in Soviet days, in 1981”,[7] which was used to intimidate Polish leader Wojciech Jaruzelski into introducing martial law and suppressing Solidarity, the independent trade union and opposition group.

Russia’s neighbours fear that it might manufacture an excuse for its troops to stay in Belarus. Protests or provocations might lead to a ‘request’ from the Belarusian authorities to help ‘maintain order’. Short of that, Belarus may be forced into concessions that could complicate Ukrainian defence strategy, such as a reconnoitre of Belarusian-Ukrainian border crossings, or be forced into the kind of full-scale military cooperation which would kill off its future ‘hedging’ possibilities. According to officials at the Ukrainian National Security Council, “Lukashenka has always promised he would not allow Belarusian territory to be used for an attack on Ukraine, but we do not think he could refuse a direct request.”[8] Unsurprisingly, the Ukrainian authorities are monitoring the situation closely. Russian deputy defence minister Alexander Fomin, meanwhile, told Western military attachés in Moscow that the West had nothing to fear.“Some people are even going as far as to say that the Zapad-2017 exercises will be used as a springboard to invade and occupy Lithuania, Poland or Ukraine,” he claimed. “Not a single one of these paradoxical versions has anything to do with reality.”[9]

Zapad 2017 is not the start of the third world war. Russia is not currently looking for new foreign adventures, since its wars in Ukraine and Syria are already draining resources and lack a clear end game. Zapad 2017 is rather a case of Russian ‘heavy metal diplomacy’.[10] The purpose of the exercises is to signal Russia’s military might to NATO and to keep its immediate neighbours on edge. Europe should stay calm and not overreact to the exercise, but it should still demand transparency and make clear that any overt threats or simulated nuclear attacks on neighbours – such as those carried out on Sweden – will have consequences.[11]

There remains little evidence to suggest that Russia will use Zapad 2017 as a cover to establish a de facto military presence in Belarus, or to replace Lukashenka. For Moscow, an airbase in Belarus is a nice-to-have rather than a must-have in strategic terms. Russia is also not willing to pay the political price of military action against another neighbour at the moment. The tactical advantage that Russia might gain from Zapad 2017 is also doubtful. As one analyst put it, “it doesn’t make sense for Moscow to organise anything during these exercises. Too many observers. Too many eyes”.[12]

At the end of the day, Moscow does not need to intervene militarily to keep Lukashenka in line. He may be a difficult ally for Moscow, but he is also a highly dependent one. As long as Lukashenka stays in control and operates within set parameters, Moscow does not need to depose him or destabilise Belarus unnecessarily. It has other levers, notably economic ones, at its disposal.

The security story

Russia’s assault on Ukrainian sovereignty since 2014 has led to speculation that Belarus might be next.[13] It has also increased the risks for Minsk of too slavishly aligning with Russia. After Lukashenka’s controversial crackdown on protestors following the disputed 2010 elections, the West isolated Belarus, imposed sanctions, and kept it at arm’s length because of its poor human rights record. It was nominally a member of the EU’s Eastern Partnership, but kept its participation to a minimum. Belarus was deep in Russia’s orbit at the very moment when Moscow launched its key regional initiatives: the Customs Union in 2010, the Single Economic Space in 2012, and the Eurasian Economic Union in 2015. Belarus therefore allowed itself to be dragged in further than it otherwise might have.

Minsk’s initial attempts to shift its strategic orientation by decreasing its dependence on Russia began after the war in Georgia in 2008. Despite enormous pressure from Russia, it refused to recognise the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. This led to a Russian propaganda war against Lukashenka and an abortive, but desperate, opening up of Belarus to the West. The domestic political concessions which some Western actors tried to extract by providing aid were dubbed a “price tag on democracy”.[14] But, facing violent protests in the wake of the 2010 presidential election and staring economic collapse in the face, Lukashenka was forced into a rapprochement with Russia.

But it was Russia’s annexation of Crimea and military intervention in eastern Ukraine in 2014 that constituted a watershed moment for Minsk. It brought home the extent to which Russia was willing to go to maintain a sphere of influence over the neighbourhood. It also brought home the dangers of hosting a Russian military base on one’s territory, as a potential spring-board and rationale for military intervention and annexation. For this reason, Lukashenka has been holding off Russian demands to establish an airbase in Belarus since 2015.[15]

While the events of 2014 greatly complicated Belarus’s regional security environment, it also injected new life into Lukashenka’s social contract with the population. The previous model of generous benefits and subsidies in return for limits on political freedom was replaced by the offer of stability instead of freedom, as neighbouring Ukraine descended into chaos. Belarusians came to appreciate the stability that the state offered, despite the repression they faced in their everyday lives.[16]

The West began paying greater attention to Belarus’s predicament after the war in Ukraine began. The fact that the 2015 presidential election was less controversial than in 2010 also eased the way for greater dialogue between the EU and Belarus, even if it was no more democratic. There was a ‘truce’ between the government and opposition, and political prisoners were released in August 2015. Most EU sanctions were lifted in February 2016 and Brussels adopted a policy of “critical engagement”.[17]

Since then, Belarus has been active on several diplomatic fronts in an effort to extend its options as an independent country. For example, in a deliberate attempt to deflect Russian pressure to align with it against Ukraine, Lukashenka offered to host talks between the parties in a bid to end hostilities. The ‘Minsk process’ was born, leading to two peace agreements in September 2014 and February 2015, as well as fortnightly meetings in Minsk between the parties of the conflict. In private, Belarus began sharing security information with Ukraine in 2014, even on Russian troop movements, and has continued to do so.[18] Lukashenka and foreign minister Vladimir Makei have launched a grandiose proposal for a ‘Helsinki 2.0’ agreement to replace the Helsinki Accords.[19]

Beyond hard security concerns, Belarus took the chair of the Central European Initiative, a regional intergovernmental forum on European integration, in 2017 – the first time in its history it has chaired an organisation outside of the post-Soviet space – and succeeded in muting most criticisms of Belarusian autocracy. Belarus also hosted the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly in July 2017. And, in just two days in July, no fewer than four separate EU delegations visited Minsk.

Meanwhile, among its immediate neighbours, Belarus has improved relations with Poland and Latvia, as well as Ukraine. Relations with Lithuania remain poor, however, given Belarus’s construction of a nuclear power station just over the border from Vilnius. This spat has, to some extent, hijacked internal EU discussions on Belarus.

But what exactly is Belarus trying to achieve? There are many options open to small states caught between big power blocs. But Belarus’s game of balance is not about equidistance. According to analyst Yauheni Preiherman, “strategic hedging is about having a full menu of choices, and using whatever works best at any given moment.”[20] It is structurally dependent on Russia in the fields of the economy, energy supply, and security, so its primary relationship will continue thus. But Belarus tries to “resist everything that compromises its sovereignty, or its ability to hedge.”[21] Belarus also takes certain decisions in order to show that it has the sovereign power to make such decisions.

How does Russia react to this strategy? Although not currently dominant in the Kremlin, proponents of Eurasianism in Russia oppose Belarus’s moves to protect its sovereignty, as they do not think the country deserves it.[22] They have taken to attacking Makei as the leader of a “Europeanist” fifth column manoeuvring to succeed Lukashenka and turn Belarus into a “second Ukraine”.[23][24] A second group considers Lukashenka to be leveraging Moscow for little return. Former minister of finance Alexey Kudrin used to represent this group. Now it is led by the prime minister, Dmitry Medvedev. Putin is in the middle, but, like the second group, he sees the benefit for Russia largely in security terms.[25] What unites all opinion in Russia is the view that Belarus has not been behaving like an ally since the Ukraine crisis in 2014, or even since the war in Georgia in 2008.

But Belarus was still not disloyal enough to require Putin’s consideration. In order to get Moscow’s attention, Lukashenka had to make an unprecedented seven-hour speech in February 2017, in which he blasted Russia for using its control of the energy supply to force his country into submission. He was finally granted a meeting with Putin in St Petersburg in April. But, according to one Belarusian analyst, “this won’t change the core fact that the relationship is deadlocked. Any attempt by Moscow to convert Russia’s long-term investments in Belarus into expanded influence on Minsk will be met with opposition. Just as Belarus itself has become used to independence, its permanent president has become unable to share power with anyone [else]. Attempts by Minsk to return to the previous model [of Russian subsidies and support], which Belarusians called ‘gas for kisses’, will also be fruitless; the Kremlin isn’t interested in this kind of relationship any more”.

The economic story

The April 2017 St Petersburg deal was not as generous as it first seemed. It appears mainly to have been agreed for geopolitical reasons. Russia wanted to rein in Belarus’s hedging strategy. Belarus wanted enough money to keep its domestic political system and sovereignty intact. The apparently generous subsidies agreed for Belarus will therefore be pulled apart at both ends. Economically, Belarus remains trapped in several ways.

A grinding recession has reduced many of the economic gains that characterised Lukashenka’s early years from 1994 onwards. Belarus needs to keep Russian subsidies flowing, although the pressure of the recession forces it to rationalise the relationship where it can and reduce its demands on Russia. The ‘strategic hedging’ model also pushes it away from overdependence; the economic side of this is trade diversification. In 2016, Belarus announced a ‘30-30-30’ strategy, aiming for 30 percent of exports to go to Russia (instead of 39 percent in 2016, and 55 percent of imports coming from Russia), 30 percent to the EU, and 30 percent to the rest of the world.[26] Further complicating matters is the social contract that has been the basis of Lukashenka’s regime for 20 years. Even after the 2015 election Lukashenka promised not to abandon its basic guarantees.

But Belarus has had no fewer than three economic crises since 2008. The first came with the shockwaves of global recession in 2009. The second came after an unsustainable spending surge to get Lukashenka through the 2010 election, temporarily overcome after a loan agreement with Russia in November 2011. The third and much deeper recession came with Russian (and Ukrainian) economic collapse in 2014, compounded by the fall in the oil price, and by aggressive devaluation in Russia to mitigate the impact of sanctions (Belarus was not consulted). GDP fell by 3-9 percent in 2015 and

2.7 percent in 2016. Russian subsidies used to provide up to 15-20 percent of GDP, mainly from cheap oil and gas. The revenue from oil exports was the key discretionary fund keeping going the economic and political system. But this has fallen sharply from a peak of $16.4 billion in 2012, to $6.1 billion in 2016.[27]

A putative $3.5 billion deal with the International Monetary Fund is unlikely, so long as Lukashenka is not willing to accept deeper structural reform. The reforms to state-owned enterprises required by the IMF would cause unemployment, risk social unrest, and ultimately put Lukashenka’s power at risk.

In short, Belarus needs money, but lives hand to mouth via the subsidies and deals that it earns from ‘strategic hedging’. Some populist policies have been cut back, such as regular, nationwide wage increases and state-directed lending. Short-term visits to Belarus are now visa-free for passengers flying into the international airport in Minsk in order to encourage revenue from tourism. Microeconomic reforms have seen the country rise from 82nd in the World Bank Doing Business Index in 2014 to 37th in 2016.[28]

Inflation is at a record low. But Belarus has also been forced to float its currency and keep interest rates high. Refinancing rates were as high as 45 percent in 2011, and although they have come down, were still at 12 percent in the summer of 2017. Belarus is searching for revenues wherever it can.

The St Petersburg deal raises as many questions as it does answers. An additional loan of $1 billion was promised.[29] But gas prices were only discounted through to the end of 2019 (with Belarus due to pay $129 per 1,000 cubic metres in 2018 and $127 in 2019). Even that would cost Belarus an estimated $500m to $600m. Belarus also acknowledged arrears of $726m in gas payments that would strain its finances.

The one unequivocal piece of good news for Belarus was the Russian promise to restore the supply of crude oil to 24 million tons per annum from 18 million in 2016, allowing Belarus to increase its exports of refined oil, albeit at lower global prices. But in August Putin seemed to undermine even that promise by suggesting that Belarusian oil exports should be re-routed from traditional ports in Latvia and Lithuania to Russian ports near St Petersburg.[30]

Lukashenka has always exaggerated his popularity at the ballot box. But the foundation of his support was always his social contract and the generous subsidies that maintained the economy until 2010. During the ‘golden years’ before 2010, Belarus avoided the extremes of oligarchy or poverty seen in Russia or Ukraine. But now, anaemic growth is already creating ‘two Belaruses’, and will do little to affect the new reality, outside the capital, of low wages, hidden unemployment, and part-time work. The St Petersburg meeting was just the latest example of the regime’s chronic short-termism.

The protest story

The other key event in Belarus in 2017 was the unprecedented – and unexpected – five weeks of protests in February and March. These were triggered by the imposition of what the government itself dubbed the ‘social parasite’ tax, but their root cause was the substantial worsening of the socioeconomic situation over the previous three years. Lukashenka’s tax was an ill-judged attempt to reduce the costs of state support for the ‘second Belarus’. But it resulted in 450,000 of the economically ‘inactive’ (in a work force of 4.5 million) receiving demands for steep payments (about $250), including young mothers and those caring for the infirm. Unlike previous protests, average Lukashenka supporters rather than just the urban elites now took to the streets, and turned out in large numbers in usually quiet regional towns. The average salary nationally has dropped to around $450; in the regions it can be as low as $150.

Lukashenka was caught out by the protests, because he lacked the funds to buy the protesters off. Belarus’s economy is stagnating, its problems are structural, and there is no obvious solution. Investment in Belarus has collapsed, as has the construction sector in particular – which provides a vital means of absorbing labour. Without adequate foreign exchange reserves, the government has been forced into adopting a deflationary policy in which there are high interest rates and a floating exchange rate. Seasonal labour in Russia, which used to act as a safety valve for regional unemployment, has also fallen sharply. Prices are now higher than in supposedly unstable Ukraine.

The protests should not be seen as the beginning of a ‘Belarusian Maidan’, because the scenario in Belarus is entirely different to that in Ukraine. The protests in Belarus were not about its geopolitical orientation or national identity, despite the opposition’s best efforts to frame it as such, but about economics. After a shaky start, the government’s response combined sticks and carrots, but seemed to threaten a return to the tactics of old. The government suspended the ‘social parasite’ decree for a year, but hundreds were detained in two waves of arrests. The authorities made much of the arrest of two dozen members of a nationalist ‘White Legion’ group, on the grounds of preparing armed riots, in a bogus case to justify the crackdown. The authorities have long used the ‘Ukrainian scenario’ and the spectre of violent revolt as a means of scaring the public and as an asset when negotiating with Russia (seemingly successfully), by posing as a bulwark against the spread of revolution. Lukashenka was extremely lucky that his crackdown at home coincided with a sudden wave of anti-corruption demonstrations in Russia – increasing the force of this argument to the Kremlin.

But on closer inspection, all sides behaved differently compared to 2010. The authorities trod a line, in which they used enough force to end the protests, but not enough to threaten the country’s rapprochement with the West, or to give Russia an excuse to intervene. Most protestors were released the same day; two-thirds of the remainder received only administrative fines. The members of the ‘White Legion’ were released by the summer, although the cases against them were not closed.

The authorities’ intimidation tactics, and the economic sliver of hope from the St Petersburg agreement, seem to have been largely effective in deterring further mass protests. But another trigger could easily start them up again. Lukashenka has said that he will amend but not withdraw the ‘social parasite’ decree, which is due to be presented again in modified form just after the beginning of Zapad 2017.

Conclusion

So where does this leave Europe? There is a modest opportunity for Europe to bring Belarus closer, both in terms of strategic alignment and in pushing for democratisation. Europe should embrace Belarus’s efforts to strengthen its external sovereignty and to pursue a policy of ‘strategic hedging’ and avoid steps that would increase its dependence on Russia. There are constituencies within the administration that see the advantages of moving towards the West, but which also recognise the realities of how far Belarus can go.

European states should accept Minsk’s invitation to send military observers to Belarus for Zapad 2017. The invitation provides a degree of transparency but is also a manifestation of Belarus’s sovereignty (given Moscow’s displeasure with this move). An overall deepening of military ties, through military-to-military cooperation and exchange programmes, would also be beneficial.

The EU should also further support Lukashenka’s balancing act of maintaining a neutral stance with regard to Russia’s conflicts with its neighbours. The hosting of talks in Minsk has proven useful for the West as well as an effective insurance policy for Belarus. It has allowed Belarus to deflect pressure by Russia and not follow it on crucial foreign policy issues. The net effect of this neutrality has been greater alignment with the EU.

As Belarus tries to diversify its strategic options and decrease its dependence on Russia, the EU needs to be realistic in its ambitions for how the country might change in the medium and long term. Belarus will not become a democracy any time soon. It is not about to break with Russia either. But it is in the EU’s interests to support Belarus’s ‘strategic hedging’ policy, since it keeps the door open for greater Belarusian alignment with the EU. It is also in the EU’s interests to support some of its consequences, such as economic diversification. The EU should dangle the prospect of a new contractual arrangement (to replace the outdated and unratified Partnership and Cooperation Agreement from 1995) in case Minsk shows willingness to move towards improving the human rights situation. A new agreement would provide greater leverage for the EU and more opportunities to push Belarus on reform.

At the same time, Europe needs to be clearer about its red lines and the steps it wants Belarus to take on human rights and democratisation. Minsk knows, for instance, that a return to the era of political prisoners would end any opening with the West, but there is less clarity in other areas. This does not have to stand in contradiction to engagement. Europe should present clearly targeted and signalled responses to acts of repression against the population. The authorities are restrained by the risk of deteriorating relations with the West but will test the limits of what they can get away with if there is no clarity on red lines.

Ultimately, influence will come through greater engagement with Belarus’s authorities. This engagement should aim to give a stake in the relationship to constituencies at all levels in Belarus’s administration. There are moderate, pro-Western constituencies in different ministries which can make the case for further rapprochement with Europe. And Europe can strengthen these constituencies by helping them show that engagement brings benefits, such as access to EU funding.

It may be counterintuitive, but the right response to the authorities’ crackdown is more, rather than less, engagement with Belarus. The authorities’ relatively restrained approach – by Belarusian standards – to the protests shows that Minsk is still interested in a rapprochement with Europe and that European engagement actually has a positive impact. Any decision by Europe to revert to an isolationist policy or impose new sanctions would be counterproductive, as it would give Minsk less reason to listen to Europe and only push Belarus further into the Russian camp. Even with major military exercises in the offing, there is no need to panic. Zapad 2017 will bring Russian troops to Belarus, but they will leave. Russia’s (and the West’s) Belarus dilemma, however, will continue.

[1] “Minabarony Rasii prakamentavala zamovu 4000 vahonau u Belarus’”, Nasha Niva, 5 February 2017, available at http://nn.by/?c=ar&i=184897.

[2] “Russia’s biggest war game in Europe since the cold war alarms NATO”, The Economist, 10 August 2017, available at https://www.economist.com/news/europe/21726075-some-fear-zapad-2017-could-be-cover-skullduggery-russias-biggest-war-game-europe.

[3] “Ukrainian defense minister calls Russian-Belarus West-2017 drills a threat, to which Kyiv will respond accordingly”, Interfax Ukraine, 30 June 2017, available at http://en.interfax.com.ua/news/general/432823.html.

[4] Damien Sharkov, “Mike Pence’s Baltic visit prompts hope that NATO will double jet deployment during Russia war game”, Newsweek, 31 July 2017, available at http://www.newsweek.com/after-pence-baltic-visit-lithuania-hopes-nato-will-nearly-double-jets-during-644352.

[5] Comment by the Information and Press Department on compliance with transparency measures during preparation for West 2017 drills, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 25 August 2017, available at http://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/-/asset_publisher/cKNonkJE02Bw/content/id/2845944.

[6] ECFR interview with Artyom Shraibman, 21 August 2017.

[7] ECFR interview with Arseni Sivitski, 21 August 2017.

[8] ECFR interview at the Ukrainian National Security Council, 23 August 2017.

[9] Andrew Osborn and Maria Tsvetkova, “Russia seeks to reassure over war games, denies invasion plans”, Reuters, 29 August 2017, available at https://ca.reuters.com/article/topNews/idCAKCN1B90ZS-OCATP.

[10] Mark Galeotti, “Heavy Metal Diplomacy: Russia’s Political Use of its Military in Europe since 2014”, ECFR, 19 December 2016, available at www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/heavy_metal_diplomacy_russias_political_use_of_its_military_in_europe_since.

[11] “Russia ‘simulates’ nuclear attack on Poland”, the Daily Telegraph, 1 November 2009, available at http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/poland/6480227/Russia-simulates-nuclear-attack-on-Poland.html; “Russia ‘simulated a nuclear strike’ on Sweden, NATO admits”, the Daily Telegraph, 4 February 2016, available at http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/russia/12139943/Russia-simulated-a-nuclear-strike-against-Sweden-Nato-admits.html.

[12] ECFR interview with analyst Dzianis Melyantsou, 21 August 2017.

[13] Pavel Baev, “Where will Putin strike next? Ukraine? Georgia? Belarus?”, Newsweek, 16 March 2017, available at http://www.newsweek.com/where-will-putin-strike-next-ukraine-georgia-belarus-568444.

[14] Andrew Rettman, “Poland puts €3 billion price tag on democracy in Belarus”, EU Observer, 4 November 2010, available at https://euobserver.com/foreign/31203.

[15] Interviews with Belarusian officials, Minsk, April and August 2017.

[16] In 2014, 70 percent of Belarusians said they would not like “events similar to Ukraine to happen in Belarus”. See: Andrew Wilson, “Belarus: From a Social Contract to a Security Contract?”, Journal of Belarusian Studies, vol. 8. no. 1, 2016, available at http://belarusjournal.com/article/belarus-social-contract-security-contract-274.

[17] EU-Belarus relations, fact sheet, European External Action Service, 15 February 2016, available at https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/4014/eu-belarus-relations_en.

[18] ECFR interview ith Ukrainian security, official, Kyiv, 23 August 2017.

[19] Igar Gubarevich, “Saving Europe’s Security Architecture – Belarus Foreign Policy Digest”, Belarus Digest, 16 January 2017, available at https://belarusdigest.com/story/saving-europes-security-architecture-belarus-foreign-policy-digest/; “Lukashenko suggests launching discussion on new Helsinki process in OSCE”, Belarus.by, 5 July 2017, available at http://www.belarus.by/en/press-center/speeches-and-interviews/lukashenko-suggests-launching-discussion-on-new-helsinki-process-in-osce_i_0000060225.html.

[20] ECFR interview with Yauheni Preiherman, 14 August 2017.

[21] ECFR interview with Yauheni Preiherman, 14 August 2017.

[22] Artyom Shraibman, “The Far-Reaching Consequences of Belarus’s Conflict with Russia”, Moscow Carnegie Centre, 8 February 2017, available at http://carnegie.ru/commentary/67939. (Hereafter, Shraibman, “The Far-Reaching Consequences of Belarus’s Conflict with Russia”).

[23] Yuriy Baranchik, “Gruppirovka Makeya nachal kampaniyu po zapugivaniyu Lukashenko”, Regnum.ru, 15 March 2017, available at https://regnum.ru/news/2249458.html.

[24] Vladimir Lepekhin, “Poluchitsya li u Bryusselya i Varshavy zakhvatit’ Minsk”, RIA Novosti, 4 July 2017, available at https://ria.ru/analytics/20170704/1497812827.html. See also: “EU’s ‘Eastern Partnership’ Threatens to Turn Belarus Into a ‘Second Ukraine’”, Sputnik, 9 July 2017, available at https://sputniknews.com/politics/201707091055387514-belarus-eu-russia-independence/.

[25] Shraibman, “The Far-Reaching Consequences of Belarus’s Conflict with Russia”.

[26] “Belarus invites Belgium to partake in Great Stone projects”, Belarus News, 1 March 2016, available at http://eng.belta.by/economics/view/belarus-invites-belgium-to-partake-in-great-stone-projects-89344-2016/.

[27] Vadzim Smok, “Does Belarus stand a chance in a new oil war with Russia?”, Belarus Digest, 13 January 2017, available at http://belarusdigest.com/story/does-belarus-stand-a-chance-in-a-new-oil-war-with-russia/.

[28] Doing Business: Measuring Business Regulations, The World Bank, 2016, available at http://www.doingbusiness.org/rankings.

[29] “Belarus says Russia promises new loans of over $1 billion”, Reuters, 10 April 2017, available at http://www.reuters.com/article/us-belarus-russia-loans/belarus-says-russia-promises-new-loans-of-over-1-billion-idUSKBN17C0KY.

[30] Siarhei Bohdan, “Putin expects Belarus to boycott ports of Baltic States”, Belarus Digest, 24 August 2017, available at https://belarusdigest.com/story/putin-wants-belarus-to-boycott-baltic-states-ports/.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.