Separation anxiety: European influence at the UN after Brexit

Summary

- Brexit comes at a bad time for Europe at the United Nations, as the United States, Russia, and China are challenging the liberal internationalism that the European Union promotes – and that some EU members question too.

- The United Kingdom has been an anchor of EU policy at the UN, providing expertise and diplomatic leadership even though British officials often complain about the constraints of European coordination.

- Brexit has the potential to upset Franco-British cooperation at the Security Council, and European coordination on development and human rights.

- Germany and France need to raise their game at the UN to compensate for Brexit, while the UK may ultimately find that it needs to work closely with the EU in New York and Geneva.

- There is no need for complex diplomatic mechanisms to manage UK-EU coordination at the UN after Brexit, but both sides need to commit personnel and resources to protecting a liberal United Nations.

Policy recommendations

- Greater French outreach to the EU on Security Council affairs.

- Deeper Franco-German integration at the UN.

- Create a “liberal caucus” inside the EU

Introduction

A mishandled Brexit could hasten the erosion of European power at the United Nations. Having adopted a benign attitude towards the UN in the Obama era, the United States is ostentatiously disdainful of the organisation under President Donald Trump. Emboldened by the success of its extended defence of the Syrian regime at the Security Council, Russia is intensifying its confrontation with the West at the organisation. Less often noticed but perhaps most consequential of all, China has suspended its generally cautious approach to the UN by pushing to reshape the organisation’s debates on human rights and international development on its terms, threatening the liberal norms the European Union tries to embed in international institutions.

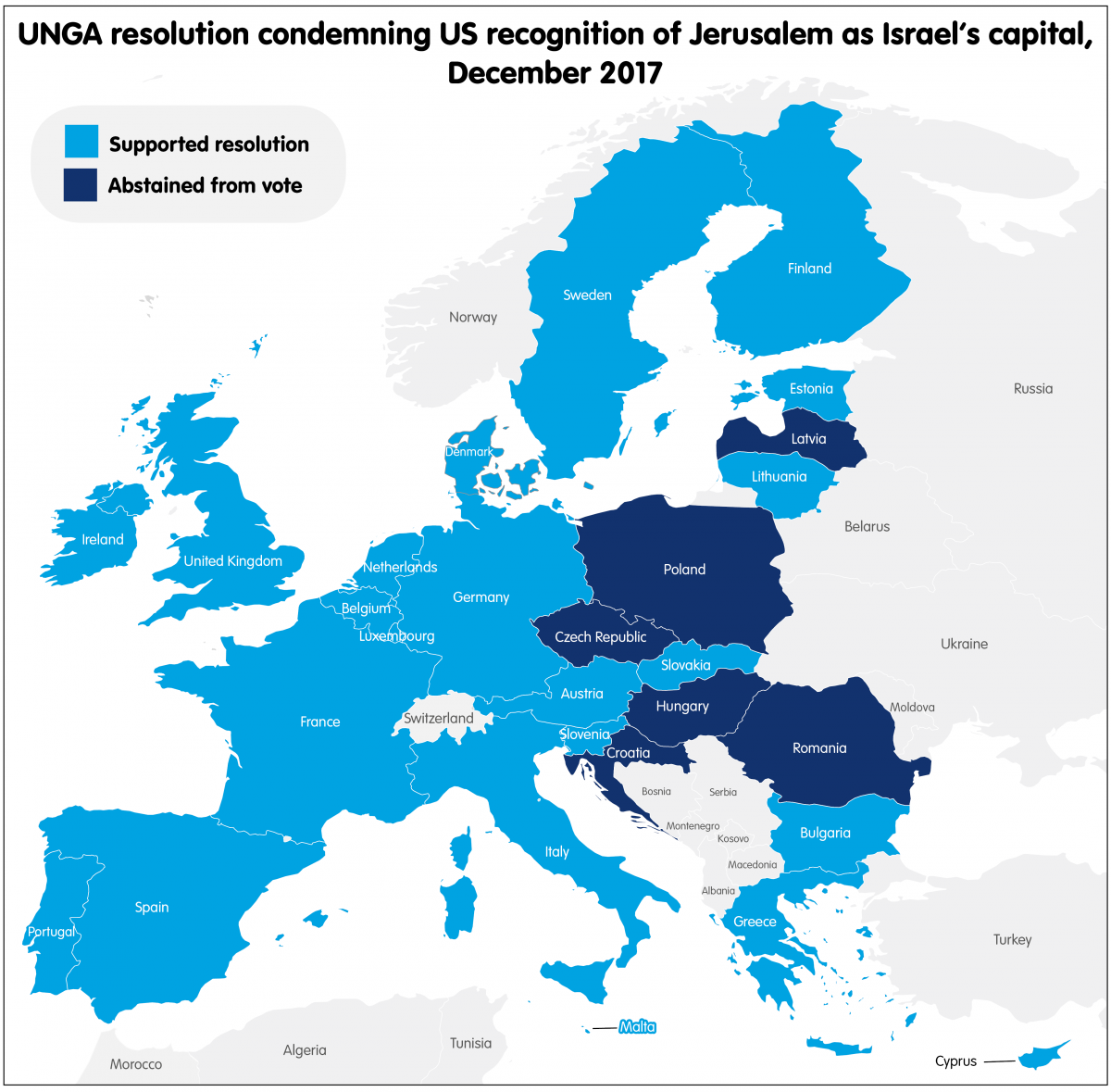

The EU’s overall response to these challenges oscillates between defiance and division. The bloc stood up to the US over its decision to withdraw from the 21st Conference of Parties (COP21) agreement on climate change, and persuaded Washington to water down its threats to make major cuts to the UN budget. But the Union split in the symbolically important December 2017 General Assembly vote on the Trump administration’s decision to move its embassy in Israel to Jerusalem. Meanwhile, China has begun to chip away at its unity on human rights. Hungary’s ruling Fidesz party made opposition to an upcoming UN compact on migration a plank of its campaign for the March 2017 general election. The EU is united on most UN votes, but there is no guarantee of its ability to defend (or even agree on) a liberal vision of the UN.

The United Kingdom’s June 2016 vote to leave the EU increased that vulnerability. The UK has long been one of the main anchors of the strong EU presence in the UN system. This is ironic given that British officials are often sceptical of the value of a European approach to UN affairs, grumbling that the strictures of intra-Union coordination limit their room for manoeuvre. The UK’s default approach to many UN debates is still to stay as close as feasible to the US position – a tendency that has been especially evident since the Brexit vote. But British diplomats and aid officials have played an outsized role in shaping the EU’s multilateral policies. They have even stepped up their efforts to strengthen the Union at the UN since June 2016.

This partially reflects the fact that, while British officials insist that they will play a consistent or enhanced role in the UN system after Brexit, they will also be newly vulnerable in New York and Geneva. Since mid-2017, the UK has endured sobering defeats at the UN on issues ranging from the status of the Chagos Islands to the election of judges to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). It is simplistic to blame all these setbacks entirely on Brexit: They reflect a broader shift in the balance of power at the UN towards non-Western powers, which arises from deeper changes in global influence. They have nonetheless shown how difficult it could be for the British to maintain a strong position in the UN system while outside the EU. Brexit will also test British officials’ capacity for hard work, as they will either have to devote time to many diplomatic debates and processes that other members of the EU once covered on their behalf through the bloc’s burden-sharing arrangements – or, alternatively, disengage from UN processes that they deem insufficiently significant.

Based on off-the-record interviews at the UN, this policy brief argues that the UK and the EU will need to maintain close relations if they want to preserve the UN as a liberal internationalist institution. The relationship should not be monogamous. There are good arguments for all European countries – regardless of their club membership – to engage in more active diplomacy with partners from other regions. Brexit may create opportunities not only for the UK to interact with other powers more intensively, but also for EU states to update their approach to UN diplomacy. France will have to balance the privilege and burdens of being the sole EU member with a permanent seat on the Security Council. Germany, which has usually deferred to the Franco-British duo in New York, will need to take a clearer leadership role in UN affairs. Other European states and the European External Action Service (EEAS) will also need to become more active to fill the gap Brexit creates – potentially leading to an increase in European diplomatic activism at the UN.

This will require focus and dedication at a time when both the UK and the EU are under external and internal pressure from many sources. Brexit’s impact at the UN has not been a subject of much speculation outside specialist circles. But, facing a struggle for power at the UN that will stretch far beyond the Brexit transition period, Europeans can either cede the field to China and Russia or fight to protect a system they have done much to build.

Brexit and the new battle for influence at the UN

European diplomats tend to describe the potential impact of Brexit on the UN firstly in terms of process and policy. British representatives are set to leave EU coordination meetings in New York and Geneva, in which they have generally played a prominent role, once the UK is out of the bloc. Under the terms of the draft agreement on the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, British officials could theoretically play a supporting role in the Union’s diplomacy at the UN until at least the end of 2020 – but European diplomats insist that London cannot expect to shape EU policy. They will miss British officials’ first-class drafting skills (no small boon given the vast quantity of resolutions and other paperwork the UN system generates), pragmatic approach to negotiations, and in-house knowledge of multilateral affairs. But the primary impact of Brexit on the UN will be political: Britain’s departure from the EU will shake up power relations with other major UN players in a period of increasing diplomatic competition.

Europe’s challengers: The US, Russia, and China

Ten years ago, ECFR warned that the EU faced a “slow-motion crisis at the UN” as non-Western states increasingly challenged the bloc’s norms in New York and Geneva. This crisis has accelerated. On issues ranging from migration to the management of peacekeeping operations, developing countries are increasingly forthright in their criticism of European positions. While they are ready to work with the EU on crises such as that in Mali, African states have become markedly more willing to stand up to Western pressure. But the EU’s three primary challengers at the UN are the US, Russia, and China.

Of these, the challenge from America is the most immediately unsettling, if not necessarily the most significant in the long term. The EU’s members largely got along well with the US on multilateral matters in the Obama era, despite occasional hiccups over crises such as the Libyan conflict. President Trump has thrown this cooperation into doubt, albeit not quite as catastrophically as it initially seemed he would.

Trump entered office promising to slash UN budgets, but his pragmatic envoy to the UN in New York, Nikki Haley, has mitigated the damage. Nonetheless, Trump and Haley have pulled the US out of a series of UN agreements and bodies, including the COP21 accord and UNESCO – in the latter case, citing the organisation’s pro-Palestinian tendencies. It is highly likely that the Trump administration will eventually cut itself off from the Human Rights Council due to the council’s frequent criticism of Israel. Even before Britain leaves the EU, Trump is liable to force a major crisis at the Security Council by attempting to kill the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action on Iran’s nuclear programme. Given the twists and inconsistencies of the administration, it is hard to predict the other indignities it will visit on the UN. It is possible that Trump’s advisers will eventually lower US pressure on the UN, or that an internationalist will win the 2020 US election and reverse his policies. But it is prudent to assume that the US will be a disruptive force in international cooperation until at least 2021.

Trump’s erratic approach to the UN has created political space for Russia and China. Moscow’s response has been crude. Having gained the whip hand over the Syrian war in the final phase of the Obama administration, Moscow has been open in its distaste for UN process on the conflict. It has attempted to sideline UN mediators in Geneva and has vetoed a series of resolutions on the Syrian government’s use of chemical weapons. In a less widely noted move, the Russians have opposed UN Secretary-General António Guterres’ efforts to modernise the UN’s sprawling development system, complicating European and US attempts to assist him in this.

If Russia’s actions at the UN are largely displays of blocking power, China is playing a game that will have implications for the UN’s broad political complexion long after Brexit. Once very cautious at the organisation, Beijing still uses its veto as a member of the Security Council sparingly to protect its interests. As a result, some diplomats who focus solely on the council continue to dismiss China as weak. But those who see its representatives at work in UN forums on development and human rights agree that there has been a sea change in its behaviour in recent years. In development debates, Chinese diplomats push hard for the UN to praise its Belt and Road Initiative. In the February-March 2018 session of the Human Rights Council, China and a group of non-Western allies tabled a new resolution on what they called “win-win cooperation”, which amounted to a sweeping call for state sovereignty over individual rights. Western diplomats persuaded the Chinese to water down the text, but human rights experts still saw “deep geopolitical symbolism” in China’s decision to lay out its agenda so clearly in a UN resolution for the first time – and the fact that non-Western states voted it through despite continuous US and EU objections.

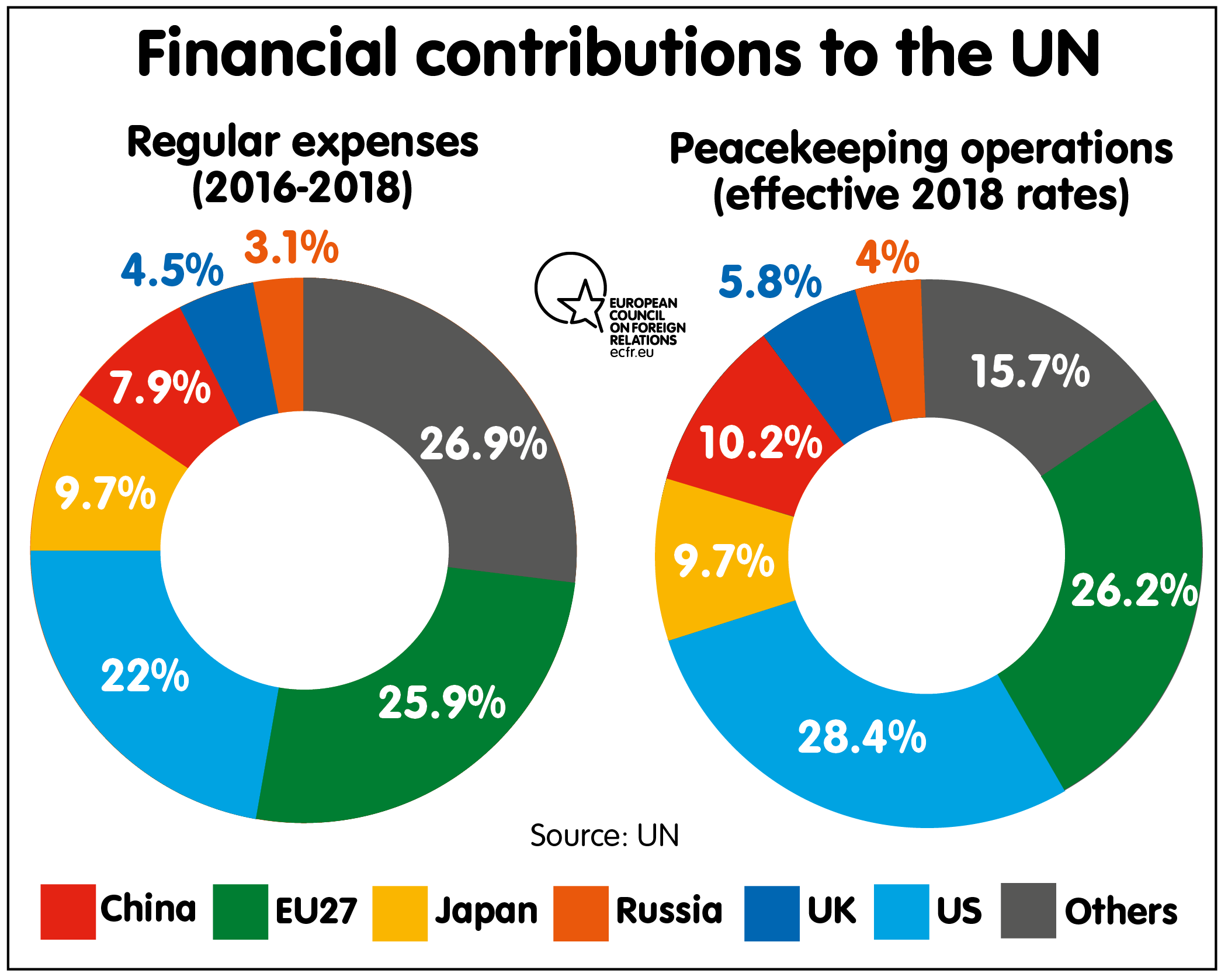

In more practical terms, Beijing has campaigned to cut posts for human rights officials in UN peace operations and at the UN headquarters in New York. Having become the second-largest contributor to the $7 billion UN peacekeeping budget after the US (surpassing Japan in 2016), China has become notably firmer in budget talks. European diplomats claim that China regularly lines up diplomats from other developing nations to repeat its positions, demonstrating its strengthening political grip on these partners.

China still has a long way to go before it surpasses the US in its formal influence at the UN. And the Europeans can still outflank Beijing. In 2016, China signalled some interest in trying to place one of its officials at the head of the organisation’s influential Department of Peacekeeping Operations, a post that France has filled as a matter of right since the mid-1990s. It soon dropped this initiative in the face of French opposition. Nonetheless, Chinese diplomats are likely to become even more active and ambitious. The combination of US disruptiveness, Russian obstructionism, and China’s long game have frequently put Europeans on the defensive.

Divisions within the EU?

While they are worried about Russia and conscious of China’s increasing assertiveness, European diplomats have primarily focused on the American challenge. They have succeeded in limiting or delaying some of the Americans’ plans to weaken the UN. When the US cut funding to the UN Population Fund, a long-time target of Republican administrations because of its work on family planning, the Netherlands led a push to make up the shortfall. France has battled the US to protect UN peacekeeping forces in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Lebanon from American criticism and cuts. The EU as a bloc – with the UK still very much on board – also successfully coordinated pushback against US plans to cut the UN peacekeeping budget by $1 billion in mid-2017. After Haley warned that America might walk away from the Human Rights Council, the Netherlands and the UK set up a working group with Latvia and Rwanda to table reform proposals for the council that could potentially keep Washington on board.

Nonetheless, the US has managed to exploit cracks within the EU to its advantage. It did so most successfully in December 2017, when it persuaded six EU member states (Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, and Romania) to abstain from a highly charged General Assembly vote on rejecting the US embassy in Israel’s proposed move. Although the resolution still sailed through, and no EU member voted against it, European diplomats report that it prompted a barrage of American and Israeli lobbying. Some states, including then EU president Estonia, were reportedly wavering until the roll call began. One participant said that more EU countries might have abstained if the vote had come a few minutes later.

The US is not the only power to scent divisions within the EU. China persuaded Greece to block an EU statement criticising its human rights record at the Human Rights Council in 2017. The fact that Chinese companies own a controlling stake in the Port of Piraeus is allegedly the decisive factor in this move. European officials fret that Beijing’s growing investments in Europe will increase its ability to undermine EU positions in future. But the Union also faces increasingly active internal dissenters. As part of its broader campaign against migrants and refugees, Hungary has attempted to derail UN talks on the new Global Compact on Migration, which aims to prevent the kind of crises involving the large-scale movement of people currently seen in the Mediterranean and Sahel. By threatening to block common EU positions or walk out of talks on the initiative, Budapest has pushed the rest of the bloc to harden its line on migration control. There is speculation that the US – which pulled out of the compact process in late 2017, calling it an attack on American sovereignty – has encouraged the Hungarians. In truth, quite a few ostensibly liberal EU members are glad to have an excuse to avoid hard decisions about liberalising migration rules. But the controversy has heightened perceptions of European disunity at the UN.

Britain under pressure

The UK has long had a paradoxical position in European diplomacy at the UN. While British diplomats are willing to hold up EU consensus positions to protect their interests, they also often act as conciliators inside the bloc. For example, on sensitive issues such as sexual and reproductive rights, they have found common ground between liberal and socially conservative EU members. Yet the UK cannot entirely shake off memories of its role in splitting the EU over the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. A few years later, the British opposed efforts to give the EEAS a stronger profile at the UN after the Lisbon Treaty.

After the Brexit vote, many diplomats and UN officials assumed that the UK would simply default to fealty to the US in multilateral affairs – not least to secure a free trade deal with Washington. In the last months of the Obama administration, the UK mission in New York worked with the US to orchestrate a Security Council resolution criticising Israeli settlements in the Occupied Territories. Having received a dressing down from the Trump transition team, London distanced itself from the January 2018 conference on the Middle East peace process in Paris, denying the EU a common position on the issue at the Security Council. At the time, European officials worried that the UK had already deserted the EU.

The reality is more complicated. The British have remained close to the US on many issues, but have also signalled a continuing desire to work with the EU. British diplomats have made a point of engaging fulsomely with European coordination meetings, even sharing information on Security Council matters more openly. In response to the Trump administration’s threats to torpedo the Iran deal, London has taken a softer approach to Washington than have the French. But the UK has also made it clear that it stands with France and Germany in defence of the agreement. Paris and Berlin were relieved when the UK came out in opposition to Trump’s Jerusalem decision at both the Security Council and the General Assembly, reducing their resentment of British behaviour in January 2017.

While Anglo-American ties remain strong – leading American diplomats to quip about the unfortunately acronymed “USUK coalition” – the British have signalled that they will not follow Trump’s dictates blindly after Brexit. Yet the UK has faced pressure from another source, as non-Western countries have inflicted a series of defeats on the British in UN votes that London did not necessarily see coming. In May 2017, the UK failed to make one of its nationals director-general of the WHO, losing by a large margin to an Ethiopian candidate. The following July, Mauritius persuaded the General Assembly to refer the status of the Chagos Islands – UK territory that incudes Diego Garcia, home of a US military base – to the ICJ over American and British objections. The UK has lost General Assembly votes on decolonisation before, but received a genuine shock in November 2017, when an Indian candidate defeated a British incumbent to win a seat on the ICJ, with the result that there was no Briton on the court for the first time since its creation. After each setback, British commentators leapt to claim that the incident was evidence of Brexit-induced decline. The House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee felt moved to launch an inquiry into the state of British influence at the UN.

Fundamentally, these defeats stem more from developing countries’ desire to have a greater say at the UN than dynamics specific to Brexit. The UK has invested too little in relationships at the General Assembly in recent years, leaving it exposed to concerted campaigns by powers such as India. Nonetheless, the three defeats brought home the dangers associated with exiting the EU: For instance, the majority of other EU members, including France, abstained on the Chagos Islands resolution. These episodes also complicated Brexiteers’ claims that the UK could swap the EU for the Commonwealth as a natural multilateral partner because, in two of the votes, London directly competed with a member of the Commonwealth.

Therefore, the UK approaches Brexit with three questions hanging over it at the UN. Firstly: How will it relate to the EU? Secondly: How will it relate to the US? And, thirdly: Can it rebuild a friendly constituency among non-Western countries to offset the ructions in its Western alliances? Yet, while these are pressing diplomatic questions, the truly decisive factor in Britain’s position at the UN will be the outcome of the Brexit wars in Westminster.

In the last two decades, UK policy at the UN has been broadly static. Successive governments have emphasised the importance of multilateral cooperation and reinforced this position by spending 0.7 percent of gross national income on international development. Not all prime ministers have given the UN equal weight: David Cameron was notably less passionate in his multilateralism than Gordon Brown before him. Even so, Cameron saw the political advantages of maintaining a good profile in New York.

Theresa May has stuck with this tradition, reaffirming the 0.7 percent pledge. Yet some of the current pretenders to her crown threaten to upset the norms of UK-UN cooperation. Brexiteer Jacob Rees-Mogg has argued against the 0.7 percent pledge (as have media outlets that supported Brexit, including the Daily Mail and the Sun). A post-May government could remove one of the planks of recent British policy at the UN. In contrast, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn appears to be a passionate believer in the UN and has criticised the government for launching a military strike in Syria without Security Council approval. The Brexit process could conceivably lead to either a UK government that questions British contributions to the UN or one that treats the organisation with greater respect.

Thus, while UK diplomats have probably managed the period since the 2016 referendum as well as could be reasonably expected, political currents at home could change their position at short notice.

Waiting for Brexit

What do other European diplomats at the UN expect of Brexit? The simple answer is that they are not sure. After a flurry of speculation and cables to capitals shortly after the referendum, most European missions left the topic on hold until 2018. This was partly out of respect for the UK-European Commission negotiations in Brussels, and partly because Trump’s election presented a more immediate threat to the UN. Although Brexit’s approach has started to focus diplomatic minds on the issue, there is no consensus on what Britain’s departure will mean politically.

For France, Brexit presents both an opportunity and a dilemma. As the only EU member with the same depth of UN expertise as the UK, France appears well placed to assert itself as the bloc’s leader in New York and Geneva. Yet Paris often struggles to persuade other EU members to take seriously its main priorities at the UN, such as peacekeeping in Francophone Africa. Some European diplomats argue that, if France is to become the de facto standard-bearer for the EU at the UN, especially at the Security Council, it will have to listen to the rest of the bloc’s members more closely, reducing its freedom of diplomatic manoeuvre. Behind such talk lurks the long-standing (though still rather unlikely) possibility that the French seat on the council might one day morph into an EU one. This is not a popular concept in Paris. President Emmanuel Macron, an ardent promoter of EU cooperation, emphasised a national rather than European approach to the UN when he addressed the General Assembly for the first time, in September 2017.

Brexit also creates openings and headaches for Germany at the UN. Berlin has long been a conservative player in the multilateral system, deferring to France and the UK. It shifted gears during Chancellor Angela Merkel’s previous administration, investing more financial and diplomatic resources in the UN to help manage disorder and large-scale migration in Africa and the Middle East. The arrival of Merkel’s former foreign policy adviser, Christoph Heusgen, as ambassador in New York in late 2017 confirmed this trend. As a leading European donor to many UN funds and agencies, the Germans should be able to wield great influence on the organisation. Nonetheless, it remains cautious, conscious of its lack of a permanent seat on the Security Council and wary of upsetting other EU members by overreaching. The German foreign service has yet to acquire the instinctive knowledge of the UN that its British and French counterparts enjoy, and it has other pressing priorities – such as dealing with Russia – to juggle.

Many countries that do have a strong tradition of UN diplomacy – such as the Netherlands and Nordic states – are among those most concerned about the effects of Brexit. Generally, these countries have seen the UK as a natural point of reference in UN affairs on issues ranging from aid efficiency to the promotion of human rights. This is also true of the EEAS. Although the UK attempted to place restrictions on EU officials’ UN activities in the early years of the Lisbon Treaty era, there has since been a notable convergence between London and Brussels on multilateral matters. During the financial and euro crises, European institutions and the UK played major roles in propping up international aid and humanitarian assistance while other donors cut funding. Their views on many UN policy issues – such as aid efficiency, budget control, and conflict prevention – now overlap to a significant degree, with British nationals having held senior posts within EU delegations in New York and Geneva. Brexit distances the EEAS from one of its closest allies on multilateral issues among the EU members – an unexpected twist, given their rocky start a decade ago.

Therefore, at a time when American, Chinese, and Russian activities are creating uncomfortable questions about the future of the UN system, Brexit introduces another source of uncertainty for both the UK and the EU27. In light of this, it is inadvisable to make firm predictions about how the process will play out. But it is almost inevitable that Britain’s departure from the EU will have a considerable impact on security, development, and human rights diplomacy across the UN system.

UN diplomacy after Brexit

Brexit will have varied effects on the UN system, as the rules of diplomacy differ across forums and policy areas. For example, at the Security Council, the UK’s influence as a veto-wielding power is baked into the UN Charter. In contrast, at the General Assembly and the Human Rights Council, numbers matter as all members have equal voting rights. While the UK and other EU members have always enjoyed considerable clout as major funders of the UN, China’s increasing financial significance is starting to shake up negotiations in a range of areas.

The Security Council and crisis management

In the aftermath of the Brexit referendum, commentators mischievously asked if the UK might lose its seat on the Security Council. The answer is “no”. (Even if Scotland became independent, the UK could hold onto its seat just as Russia did following the collapse of the Soviet Union.) Some diplomats doubt that Brexit will have much impact on Security Council diplomacy, as Britain and France have never deferred to the EU as a bloc in this arena. Nonetheless, Britain’s decoupling from the EU will inevitably affect its working relations with other council members, particularly France and the US. Known collectively as the P3, the countries dominate large swathes of council diplomacy, drafting and pre-negotiating resolutions while often handling sensitive business involving China and Russia without referring to elected council members.

However, P3 relations have frayed since Trump’s inauguration, primarily due to friction between France and the US. While Franco-American relations have generally been warm in the Trump-Macron era, they have often been chillier at the UN. The Trump administration angered Paris in mid-2017 by threatening, on the grounds of cost, to veto plans for the UN to support a regional counter-terrorism force in the Sahel. A few months later, Washington again threatened to use its veto on an issue Paris cares about, claiming that the UN peacekeeping force in Lebanon – which includes French troops – turns a blind eye to Hezbollah. These run-ins, combined with tension related to the expense of peacekeeping in Francophone Africa and the Jerusalem issue, badly upset P3 coordination. The British attempted to maintain a balanced position in these disputes – neither of which directly impinge on core UK interests – but generally seemed closer to the US. As noted above, the Jerusalem episode partly reset Franco-British relations. Moreover, the members of the P3 have recently pulled together hard over chemical weapons attacks in Douma and Salisbury. Nonetheless, council members continue to speculate that the UK and the US could form an even tighter unit after Brexit, complicating France’s pursuit of its interests through the Security Council.

This could have a direct impact on the way that the UN engages in major crises. In recent years, for instance, France and the UK have sustained a delicate balance in both EU and UN debates over whether to prioritise security threats in Somalia or the Sahel. London and Paris take both crises seriously but disagree over their relative importance. The net result has been to split the difference in distributing EU and UN funds to cover both trouble spots as best as possible. UN officials and African security analysts worry that, after Brexit, this understanding will break down and France will push the EU to focus more on the Sahel while the members of the P3 disagree about how to address insecurity in Somalia.

Such bleak scenarios overlook the fact that, despite their differences of emphasis, British and French officials have developed a good understanding of one another’s needs. The UK has pointedly offered new, albeit limited, military support to France in the Sahel. At the UN, given the Trump administration’s erratic course, it is probable that the UK will choose whether to align with the Americans or the French on a case-by-case basis. In situations where it disagrees with Germany or other EU members, France could deliberately turn to the UK as an alternative partner – rather as London and Paris pushed for intervention in Libya in 2011, in the face of scepticism from Berlin. At a technical level, French officials appreciate their UK counterparts’ knowledge of the practical workings of issues such as peacekeeping and mediation, as well as sanctions. This expertise is not necessarily unique inside the EU: Finland has led UN work on mediation, Ireland is a veteran peacekeeper and so on. But the UK's range of knowledge is unusually wide. The British have a long-standing habit of taking responsibility at the council for handling issues in which they have no direct stake, such as the peace deal between the Colombian government and FARC. After Brexit, the UK may intensify this sort of work to show its commitment to multilateralism.

France, meanwhile, will nonetheless need to court other council members to insure against future friction with the US and the UK. This could involve efforts to build closer relations with China – which has signalled its discomfort at being lumped in with Russia in so many UN debates – and to cultivate the three African countries on the council. Paris will also have a keen interest in keeping other EU members close.

This will be especially true in the immediate aftermath of Brexit, when Germany, Belgium, and Poland are all likely to be council members. The Franco-German relationship will be particularly significant, as Paris and Berlin will have an opportunity to signal how they plan to cooperate in multilateral affairs in future. There are reports (queried by some diplomatic sources) that France has considered including German officials in its delegation during this period as a sign of amity – although it is unclear if this experiment would continue after Germany’s term ends.

The possibility of closer Franco-German cooperation in New York raises a further question about the impact of Brexit: What will happen to the ad hoc E3 grouping of Britain, France, and Germany that helped negotiate the Iranian nuclear deal and has occasionally weighed in on other matters, such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict? The E3 faces a severe test before Brexit, as the Trump administration attacks the Iran deal. If the trio splinters in its response to this challenge, EU-UK relations after Brexit are likely to be bleak. If it holds together, the E3 could be a very useful clearing house for its members as they work to resolve tricky multilateral problems after Brexit. But other EU members would presumably question the legitimacy of Paris and Berlin maintaining a privileged channel to the UK of this type.

The EU presence at the Security Council is likely to fluctuate: due to a quirk of UN election cycles, France could be the only EU country there in 2021. But Brexit arguably increases the importance of all elected European members, not just Germany. These countries will have to work harder to communicate EU priorities rather than leave most of the heavy lifting to Britain and France. Recent European members of the council have generally done a decent job in this, especially on crises that divide the P3 from China and Russia. For example, Luxembourg, Spain, and Sweden have all been actively trying to ease the humanitarian crisis in Syria. Stockholm has been especially active on Syria during its current term on the council, desperately trying to find common ground with Russia and impressing outside observers – while sometimes irritating the P3 – with its independent approach. Future elected members will need to perform at a higher level, not least because perceptions of European weakness in the wake of Brexit will likely prompt China and Russia to put them under significant pressure.

Indeed, Chinese, Russian, and US actions could shape the overall fate of Britain’s relations with other European members more than any other factor. Moscow, and to a lesser extent Beijing, have become increasingly adept at peeling non-Western states away from the P3. After Brexit, they may primarily focus on splitting the P3 – most obviously by driving wedges between France and the Anglo-American duo – and weakening European unity to complicate French initiatives. Russia has already exploited Brexit for rhetorical effect in debates with the UK over the Salisbury poisoning incident, claiming that London manufactured the entire episode to distract from its domestic woes.

Moscow’s aggression, especially in targeting the UK, has undermined its own strategy as France and other EU members have lined up behind London. But non-Western powers will continue to look for ways to divide the EU and the post-Brexit UK across the UN, not only at the Security Council.

Development and human rights

Despite the prominence of the Security Council, some of the most sensitive post-Brexit UN diplomacy will take place at the Human Rights Council, the General Assembly, and across the development system. Many of the most important advances in international cooperation since the end of the cold war will be at stake (even if the processes involved can be opaque to outsiders). During the last three decades, European countries, the US, and other liberal states have placed human rights at the centre of UN diplomacy. They have also pushed the UN development machinery to modernise and adapt to cover not only traditional aid but also gender issues, climate change, and conflict prevention.

The UK has been pivotal in both processes. At the Human Rights Council in Geneva, British diplomats have far deeper networks with non-European countries than most of their EU peers. Their counterparts in New York speak on behalf of the Union in roughly half of the human rights cases in which the bloc has a common position. The UK typically argues for a strong emphasis on individual and political rights rather than softer formulations on socio-economic rights, but is a little more flexible on this than some northern EU members. London’s influence on development policy is even greater. It is not only one of the top donors to UN agencies, but also a leading source of ideas. British research organisations such as the Overseas Development Institute play a crucial role in informing not only British policy but also EU and US debates.

In New York, the UK and other major European donors align to promote aid effectiveness. This does not necessarily make them popular inside or outside the EU. The British can take a tough approach to aid negotiations, keeping a constant eye on costs, whereas other EU members are often willing to be a little more political, offering non-Western countries sweeteners for the sake of a deal.

Even if many EU members think the British can be too rigid in aid debates, they also admit that it is nice to have them around to protect the bloc’s budgets. It is unclear who, after Brexit, will pick up the slack in human rights debates in New York and Geneva, and whether the EU can remain robust in development negotiations without British support. Equally, there is little certainty that the UK will be able to pursue its policy lines as firmly outside the EU as it has done inside the bloc.

While the British usually urge the EU to be firm at the UN, they also benefit from the cover the Union provides them on tough issues. At the General Assembly and the Human Rights Council, EU members coordinate their efforts on some of the human rights issues likeliest to offend China, Myanmar, and North Korea. This prevents Beijing from singling out an EU member to penalise.

UN watchers differ over whether Brexit will increase or reduce the UK’s influence on aid and human rights issues. The optimistic interpretation (for London) is that, freed from EU coordination duties, the British will be able to speak more freely and combine with non-European states to advance their agenda.[1] The UK has a good track record of building coalitions with non-Western countries on human rights issues, suggesting that it has an effective strategy it can follow in future. The pessimistic interpretation is that, once outside the EU, Britain will have to curtail its ambitions to avoid being singled out for criticism. For example, it is difficult to imagine that London would take a lead role on resolutions that could offend China if it was conducting trade talks with the country.

The UK will in any case play a somewhat less prominent role on human rights after 2019, when its current term on the Human Rights Council ends. It will be three years before the British can rejoin the council.

London will retain numerous channels through which to influence both UN policy and the EU after Brexit (even without some form of EU-UK coordination) as an influential member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, as well as the boards of UN agencies such as the Development Programme. But if its policy influence is reasonably secure for now, its ability to shape the overall direction of the political debate on aid and human rights is uncertain. China’s current drive to embed its state-centric principles and language in UN resolutions is probably only the first stage in a drawn-out effort to reshape the organisation’s standards. Although Chinese officials currently remain willing to compromise in negotiations, close observers suspect that they are setting out an ideological stall to show other states how they aim to reshape the UN during the next decade.

If the UK will have to tread carefully, other EU members will simply need to work out how to fill the gap it leaves in EU coordination mechanisms after Brexit. At the most basic level, they will have to divvy up negotiating and speaking duties on those issues which the UK has led on for the EU, chewing up time and resources. (By the same token, the UK will also need to invest more diplomatic effort in debates it previously left to other EU members to handle). The number of European countries able to substitute for the UK effectively is limited. Marc Limon, director of the Universal Rights Group (which monitors the Human Rights Council), argues that even France and Germany lack diplomatic networks comparable to Britain’s. He estimates that the next best-connected EU member is Portugal, which has a good ear for non-Western positions, while the Netherlands is strong on the rules and norms of the Security Council (one of the reasons that it has partnered with the UK to keep the US engaged). More conservative EU members – including Hungary, Malta, and Poland – may take the opening provided by Brexit to rein in what they see as the egregiously progressive norms on issues such as gender and sexuality pushed by more liberal members, sowing more dissension in the bloc. At a minimum, these conservatives have the potential to stop the EU establishing new progressive positions at the UN as a bloc – at a time when other Western UN members, such as Canada and Norway, are loudly promoting liberal positions.

Nordic countries and the Netherlands have more influence on development policy than Germany, despite the fact that Berlin’s spending should make it a superpower in this area. Even so, mid-sized and small European donors tend to focus on specific UN agencies and priorities rather than the development system in its entirety (a tendency suited to the UN’s sprawling Sustainable Development Goals, which set out 169 targets for states to adopt). Finland, for example, focuses on women’s rights, while Slovakia prioritises security sector reform. This strategy is sensible in the sense that it maximises a country’s influence on specific policy areas, but it appears to have prevented many states from gaining an overview of the UN’s activities. One notable exception is Ireland, which often manages complex General Assembly aid negotiations because it is can speak convincingly to both EU and developing states.

There is a risk that, as the UK adjusts its diplomatic posture after Brexit and EU members get up to speed on processes that the British formerly led on their behalf, China and other non-Western powers will intensify their efforts to reframe political debates on development and human rights. Some UN officials believe that the battle to defend a liberal vision of human rights at the UN has already been lost. The disruption arising from Brexit will, at a minimum, hamper Europe’s ability to protect its principles.

Global issues: Humanitarian aid, migration, disarmament, and climate change

Brexit’s effect on other UN endeavours may not be so marked. The UK is likely to retain a high degree of influence on humanitarian (as distinct from development) aid. This is another field in which London has shaped the UN agenda since the 1990s. Britons have headed the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs since 2007. The EEAS and major humanitarian donors such as Nordic countries tend to trust the UN’s operational guidance, while China has invested much less financially and politically in emergency response than broader aid issues.

EU-UN relations on humanitarian assistance are likely to be rocky for reasons other than Brexit. The migration crisis has fundamentally shaken many European governments’ faith in UN agencies’ capacity to manage mass movements of people. It has also led EU members to strike deals with states that have poor human rights records, such as Sudan, to control migration flows. As aid agencies within the UN and elsewhere have emphasised, these deals can facilitate human rights abuses and exacerbate humanitarian crises near Europe’s periphery. EU policy has complicated UN efforts to agree on a Global Compact on Migration to ease the crisis. The EU has alienated many developing countries, especially those in Africa, by maintaining a restrictive approach to migration. If the movement of large numbers of people continues to lead to human tragedies in the Sahel, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East, the UN humanitarian system will struggle to cope, and the EU will face further accusations that it has abandoned its basic principles. But if this is a disaster waiting to happen, Brexit is unlikely to be a contributory factor.

Brexit may complicate the UN’s work on nuclear disarmament, although the change will not be dramatic: France and the UK have always separated their nuclear status from their EU obligations, a stance that most NATO members support. In 2017, the bulk of EU members did not engage with an Austrian-led UN process to prohibit the use of nuclear weapons (the Netherlands was the only NATO country to do so at all). This split has made it more difficult for the EU to intervene as a group in UN non-proliferation debates. London and Paris will continue to hold the line against such nuclear restrictions – an area in which they can also expect to receive American, Chinese, and Russian backing – in much the same way that they would have if Brexit had never been an issue.

Brexit’s impact on climate change diplomacy is less certain. France has taken the political lead on climate matters since the signing of the COP21 agreement, and is working on a new environmental pact in New York in response to the US threat of withdrawal from the existing deal. Nonetheless, French diplomats freely admit that their British counterparts have been crucial in providing both political and technical support on global warming, often shaping debates within the bloc. To date, no EU member has threatened to follow the US out of COP21, although some, including Poland, were reluctant signatories in the first place. But if and when the US abandons the accord (currently slated to take place in 2020), some EU members might consider their positions. The UK does not currently seem likely to renege on its environmental commitments, despite the fact some prominent Brexit advocates are climate change sceptics. But, once it is outside the EU, the UK may struggle to influence environmental policy in the Union.

Money, institutions, and elections

Behind all these conceptual and policy debates, Brexit will affect the UK’s and the EU’s capacity to shape nuts-and-bolts issues at the UN through budget negotiations and bureaucratic reforms. Having always prided itself on its close ties to the UN secretariat, the UK has been (as noted above) a leading backer of Secretary-General Guterres’ recent push to streamline the institution and its management rules. As a robust negotiator in budget debates, it takes a harder line than most other EU members on cost controls. While the French resemble the British in their tough approach to UN budgetary talks, one former non-European UN budget negotiator questions whether they can hold the line on their own after Brexit.

London has ways to influence UN budget discussions that do not involve the EU. The UK can use its membership of the Geneva Group, comprising major donors such as the EEAS, to promote common strategies on spending – even though this group is not a negotiating bloc. Nonetheless, Brexit will inevitably reduce Britain’s financial leverage. As a highly influential member of the EU, it has shaped how the bloc’s members allocate roughly 30 percent of the organisation’s regular and peacekeeping budgets. On its own, it contributes roughly 5 percent to these budgets – around half of China’s contribution. As Beijing’s contribution to UN budgets is only like to rise, both the UK and the EU will have to contend with increasingly assertive Chinese financial officers in the years ahead. As noted above, Beijing is already trying to use its financial power to place practical limits on UN human rights work, by cutting funding for staff working on rights issues.

A final concern for the UK – presaged in the 2017 vote on the ICJ – is that it will find it increasingly hard to secure European support for its candidates in elections to UN bodies after Brexit. UN electioneering is a murky business, involving lots of junkets and free gifts for the diplomats who vote on influential jobs. Britain has not had to work quite as hard as other EU members on these campaigns, thanks to an unwritten convention that the permanent members of the Security Council deserve to fill slots in other bodies. But the ICJ and WHO elections casts doubt on this tradition, as non-Western nations assert themselves at the UN. British diplomats will have to up their game, trading promises of support with members of the EU in a bluntly transactional fashion. The UK will, for example, have to campaign to return to the Human Rights Council three years after its current term ends. Some non-Western powers might well like to prevent its return.

Beyond Brexit: Staying friends

What strategic options do the UK and the EU have to protect their respective positions at the UN after Brexit? For Britain, the primary challenge is to avoid sticking so close to the US that other powers and blocs at the UN no longer regard it as an independent actor. This would leave it in a similar position to Japan, which is a leading contributor to the UN budget but rarely strays far from US positions in New York. A more appealing model for Britain can be described as “super Norway”. While outside the EU (and so limited in debates and votes in which numbers are decisive), the Norwegians punch above their weight in New York, liaising closely with non-European states, maintaining close relations with the secretariat, and frequently shaping debates on issues such as UN reform and peacekeeping. Norway also maintains strong ties with the US without remaining subservient to it.

A post-Brexit UK could implement much of this model on a larger scale – even though the model may not be completely transferable. As a mid-sized power, Norway can keep a safe distance from clashes between major powers at the Security Council, boosting its reputation as an honest broker with non-Western states. As a permanent member of the council and a frequent target for Chinese and Russian criticism, the UK will always face a higher level of political scrutiny.

The UK will have to decide what, if any, clubs of states it wants to join after leaving the EU. It could become a member of JUSCANZ, a consultation group of Western countries outside the EU – ranging from Andorra to the US – that discuss policy issues at the General Assembly and the Human Rights Council. But this is a very loose group, and too diverse to be a serious vehicle for British influence. Some diplomats speculate that the UK could aim to join the smaller CANZ group – comprising Canada, Australia, and New Zealand – which cooperate more closely, and frequently speak as a bloc in UN debates. But it is unclear whether this would be advantageous for either CANZ or the British. As Western Anglosphere countries already coordinate closely with one another, formalising the arrangement would do little to significantly improve the UK’s capacity to promote its interests. This could even put the existing members of the trio at a disadvantage, as other states would suspect them of forming a mere front for British positions.

Advocates of Brexit have set out a more ambitious agenda involving closer British coordination with the entire Commonwealth – although London’s handling of the recent Windrush scandal raises questions about their seriousness. This approach is exceedingly unlikely to work anyway, at least in the UN context. Many of the most influential Commonwealth members, such as India and Pakistan, are strong critics of Western positions on human rights and development. (India has a tradition of questioning British positions at the UN dating back to the Nehru era.) Former British colonies in Africa, such as Nigeria and South Africa, are far more invested in boosting the African Union and sub-regional bodies such as the Economic Community of West African States. Others, such as Sri Lanka, are more interested in courting China than their former metropole. The Commonwealth can, at best, be a useful sounding board for the UK. But on controversial questions about the future of the international system and liberal norms, members of the group are unlikely to unite behind British positions.

The UK is more likely to make a virtue of Brexit at the UN by building coalitions on a case-by-case basis than by locking itself into another bloc. On most issues, EU members – or the Union as a whole – will still be among London’s most viable partners. But what shape will they be in?

As Brexit forces the EU27 to revise their approach to UN diplomacy (if only to compensate for the lack of UK expertise inside the bloc), there is a risk that the Union’s members will further increase the huge amount of time they already spend on internal coordination. But it would be a mistake for them to become more introverted in renegotiating EU positions in New York and Geneva, as it would diminish their ability to get out and persuade other states and groups to defend liberal positions.

Without the UK alongside France to broker agreements within the bloc, there will be an increasing risk that member states drift from common positions or – like Hungary in the current UN debate on migration – use the threat of defection to hold the rest of the EU27 to ransom. While some observers think that the net result will be that EU positions will become increasingly weak for the sake of consensus – and it may actually be easier to negotiate some positions without the UK in the room – there is a long-term risk of increasing European fragmentation. Paradoxically, traditional advocates of multilateralism may be as likely as illiberal spoilers to break the EU consensus. If Nordic countries and other liberals see intra-EU diplomacy growing more complex and less effective after Brexit, they may sideline the Union and promote more progressive positions outside it.[2]

The EU will need some sort of strategic leadership in UN forums to navigate these risks and respond to external challengers such as China and Russia. Although France is the most obvious leader in this effort, it is unclear whether Paris wants to take up the burden alone. An alternative – foreshadowed in reports of plans for increased Franco-German cooperation at the Security Council – is for Paris and Berlin to share leadership duties. As ECFR argued prior to Brexit, Berlin’s growing aid spending and relatively good political ties to China and Russia leave it well-placed to intervene on UN issues, even if it lacks France’s and Britain’s formal privileges in the institution. France has started to work through Berlin on multilateral issues, with Paris asking Chancellor Merkel to talk with Russian President Vladimir Putin on topics including climate change and (less successfully) Syria. Merkel also sent peacekeepers to Mali in 2017, in a show of comradeship with the French. Even if Germany remains careful not to overstate its importance at the UN, there is clear potential for Paris and Berlin to play a joint role in managing multilateral diplomacy.

Nonetheless, a wider range of concerned members of the EU will need to step up to fill the gaps left by Brexit at the UN. As noted above, the Netherlands and Portugal have proven their effectiveness on human rights, while Sweden has made a mark at the Security Council since early 2017 by taking independent positions on the Syrian war. Southern EU members such as Italy have an especially large stake in aid agencies’ responses to migration. Other members of the bloc are pushing the UN to prepare itself for future challenges: Finland, for example, has advocated for stronger multilateral cooperation on data, cybersecurity and Artificial Intelligence (themes that Secretary-General Guterres has also highlighted). Addressing all these topics in parallel demands a good deal of diplomatic time and brainpower. If European governments want to navigate Brexit successfully, they will need to make collective efforts to increase their expertise and presence at the UN, as will the EEAS.

There is another inefficiency here. If EU members become more activist at the UN, they will often find themselves competing with the UK for access to non-Western nations – yet, in many cases, their messages will be very similar. While it is possible that the UK will become more cautious on sensitive UN issues for trade reasons, and/or its former EU partners will split over human rights questions, there is a reasonable chance that Britain and the EU27 will continue to campaign for a broadly similar set of liberal norms and values at the UN. Britain could even emerge as a sort of diplomatic outrider for the EU, using its international networks and newfound independence to back up European positions in parallel with the Union at one remove. But such fast-and-loose diplomatic coordination will require effort. What steps could the UK and the EU27 take to make it work?

Protecting core values and interests

Even if British diplomats no longer participate in EU coordination meetings at the UN, they will not suddenly stop talking to other Europeans. The UN system is packed with so-called “groups of friends” that focus on specific countries in crisis, as well consultation mechanisms that involve the UK, other major EU powers, and the EEAS (such as the Geneva Group of major donors). UN diplomacy is also a highly personal business, with European ambassadors constantly interacting with one another at formal lunches and national-day receptions. There are even ambassadorial running and football clubs in New York. If the British want to have a quiet chat about UN affairs with EU members after Brexit, or vice versa, they will have multiple ways to do so. It is highly likely that they will also be able to get updates from friends in the EU on the state of the bloc’s coordination meetings, and possibly even insinuate ideas into EU talks through these intermediaries. Brexit will not mean a total UK-EU rift at the UN.

Nonetheless, the UK’s ability to directly shape EU positions will inevitably decline. If British officials try to influence the Union’s positions from the outside, they will find themselves in competition with China, Russia, the US, and other powers. The best way for the UK and the EU to approach post-Brexit cooperation is through mutually transparent mechanisms. These could take multiple forms:

- Regular information-sharing. The EU and the UK could benefit from week-to-week exchanges of views and news on UN affairs in New York, Geneva, and Brussels. This should be a light-touch process, potentially directed through EEAS and UK missions, to prevent the parties from becoming mired in unnecessary coordination processes and paperwork. The EEAS could ask Norway, Switzerland, and other natural friends along to avoid appearing to give the UK a privileged status.

- Strategic planning sessions. EU members and the UK could also prepare for major rounds of UN negotiations – such as the General Assembly every September, and regular meetings of the Human Rights Council – by holding strategic discussions on UN affairs that are less frequent but more in-depth than EU coordination talks. These would be opportunities to share long-term intelligence on potential challenges in UN forums and to work out how EU members and the UK could communicate shared messages to other states. Again, it would be important not to over-bureaucratise these exchanges – the EU already spends an inordinate amount of time producing banal lists of UN priorities – but these sessions would allow both London and EU capitals to agree on long-term modes of cooperation.

- Selective collaboration in UN forums. Where their positions align closely on sensitive issues, the EU and the UK should act together in UN forums, giving complementary statements and running joint lobbying campaigns. However, they should avoid fetishising this sort of cooperation. And they could agree to work independently on relatively uncontroversial topics to avoid wasting diplomats’ time. Close EU-UK coordination should thus send a clear signal that these issues are politically important to both of them.

- E3+EU political cooperation. The UK, France, and Germany should also aim to maintain the E3 as a loose discussion and action group designed to address high-level problems such as the crisis over the Iran deal. When dealing with major problems at the Security Council or the Human Rights Council, the E3 should whenever possible make joint statements – potentially also involving the EEAS and relevant EU states – to signal Britain’s continued engagement with the EU on political affairs involving major powers.

- Common policy initiatives and identification of challenges. The EU and the UK can also signal that they have established a common front at the UN by launching joint policy initiatives immediately before and after Brexit. These could include joint efforts to accelerate progress in fulfilling the Sustainable Development Goals or in strengthening UN peacekeeping (an issue that both Britain and France regularly emphasise). By taking the initiative, Europeans could challenge the growing narrative that China, Russia, and other non-Western powers are setting the agenda at the UN. Equally, British officials and their European counterparts should work to identify the most obvious challenges in their post-Brexit relationship – such as the Sahel/Somalia balancing act – and reach at least temporary agreements to prevent tension on these issues from escalating rapidly.

To make such coordination mechanisms work, both EU members and the UK will need to ensure that they invest sufficient diplomatic resources in the UN. After Brexit, the UK will need to expand its diplomatic footprint in New York and Geneva to handle policy and budgetary issues it currently outsources to the EU. British diplomats will also need to devote more time to UN elections than before, and simply spend more time cultivating relations across the UN membership to avoid embarrassments such as the ICJ vote. As a bloc, EU members will need to work out how to share the burden of roles Britain once played. This will not necessarily require large numbers of extra officials at their missions, but it will require them to gain new expertise in UN negotiation techniques.

The UK could play a significant capacity-building role for its European partners in this regard, by setting up bilateral or small-group training programmes for EU members (such as those starting two-year terms on the Security Council), aiming to boost their presence at the UN. Politically, EU states could take several individual or collective steps to shake up UN diplomacy:

- Greater French outreach to the EU on Security Council affairs. While it will not compromise on its privileged role at the Security Council or sacrifice its room for manoeuvre in top-level UN diplomacy, France could at least experiment with closer cooperation with other EU states in this field after Brexit. French and British officials already regularly brief their EU counterparts on council matters, but this is largely a pro forma exercise. Once the UK leaves the EU, France could test more substantial forms of communication – such as monthly strategy sessions on council affairs with groups of EU states, or discussions on Ukraine with eastern members of the bloc – to give its partners greater indirect input into council business (this is liable to be an incremental learning process).

- Deeper Franco-German integration at the UN. To reflect Germany’s growing clout in the UN system – and to create a new centre of gravity in the bloc after Brexit – France should work towards closer Franco-German cooperation in this field. Paris and Berlin have seconded officials to the UN department of each other’s foreign ministries for over a decade, and could build on this by embedding diplomats in each other’s missions in New York and Geneva, both during and after Germany’s likely membership of the Security Council in 2019-2020.

- Create a “liberal caucus” inside the EU. If some illiberal states inside the EU make a point of regularly blocking EU common positions on human rights and values, the majority that still support those values should call their bluff and continue to support such positions together – thereby highlighting their opponents’ relative isolation.

Coordination mechanisms – whether within the EU or between the UK and the EU – will not by themselves resolve the mounting political challenges Europe faces at the UN. China, Russia, and the US are liable to play a highly disruptive role across the UN system in the years ahead. Europeans, including the British, will often be on the defensive. China’s emerging campaign against Western norms at the UN poses an especially long-term challenge. Efforts at post-Brexit UK-EU coordination are only a small part of the response. But if Britain and the EU fail to cooperate at the UN after Brexit, they have little chance of protecting their core values and interests.

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by generous grants from the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland, the Federal Foreign Office of Germany, the United Nations Foundation, and the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in London. Thanks are due to many individuals who spoke with the author and commented on earlier drafts off the record, and to Fred Carver, Manuel Lafont Rapnouil, and Natalie Samarasinghe for their contributions. Marc Limon was an especially helpful guide to the Human Rights Council. Susi Dennison, Chris Raggett, and, above all, the indefatigable Pawel Zerka at ECFR saw the project through to completion. The views expressed in this report remain entirely the author’s own, as do any errors.

About the author

Richard Gowan has worked on UN affairs for ECFR since 2007. He teaches at Columbia University.

Footnotes

[1] On the UK’s work with non-EU states, see Megan and Karen E. Smith (2017) UK diplomacy at the UN after Brexit: challenges and opportunities. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19 (3). pp. 527-542.

[2] On the tendency of liberal European states to avoid the complete “Europeanization” of their positions, see Karen E. Smith, “EU member states at the UN: A case of Europeanisation arrested?”, Journal of Common Market Studies, volume 55, number 3, June 2017.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.