Kingmakers of the mainstream: predictions for the European Parliament election

Summary

- The next European Parliament will be finely balanced between the left bloc of socialists and greens, the European People’s Party, and anti-European parties.

- Regardless of whether the UK participates in the May 2019 European Parliament election, anti-European parties look likely to become the second-largest group in the parliament, with up to 35 percent of seats.

- This puts a premium on cooperation between pro-European forces beyond the confines of traditional political groups.

- The centre group of ALDE and La République En Marche! will potentially have a lot of power as kingmakers.

Introduction

With the European Parliament election set to take place on 23-26 May, we are heading into a phase in which the polls should, in theory, become more reliable. Yet, ahead of this election, there are still so many moving pieces in European politics that its outcome remains very uncertain.

In many large member states, such as Spain – which will hold a national parliamentary election in late April – domestic political developments dominate the headlines, and citizens appear to have not yet turned their minds to the European vote. The outcome of national elections could still have a great impact on how they vote in the European Parliament election.

In Brussels and Strasbourg, the two seats of the European Parliament, there are ongoing developments within pan-European political families. Members of the centre bloc – the long-established Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) and newcomers La République En Marche! – are starting to agree on how they will work together. Yet there is still high tension within the European People’s Party (EPP) over the suspension of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz for an indefinite period beyond the European Parliament election.

Perhaps most surprisingly of all, with the two initial dates for the United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union now behind us, it seems almost certain that the country will participate in the European Parliament election. Indeed, the UK’s political parties have called for candidates to stand in the vote. Prime Minister Theresa May’s government remains determined to prevent the UK from participating if possible. But now that the UK’s deadline for leaving has been extended until October 2019, the only way not to avoid participating would be for its parliament to agree on an exit deal before 23 May. At the time of writing, this looks close to impossible.

The seat predictions in this paper, based on model estimates finalised in the third week of April 2019, are the first to take all these developments into account. Drawing on data from a survey – carried out by YouGov for the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) in March 2019 – on voting intentions for the European Parliament election, in addition to national and European public opinion polls, the paper explores likely outcomes with and without the UK’s participation.

Our results show that, in either scenario, the European Parliament will be significantly different after this election. The “grand coalition” of the EPP and the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats will no longer have a majority of MEPs in the European Parliament. Thus, these political families will need to work with other groups in the next European Parliament to drive the European project forward.

Results

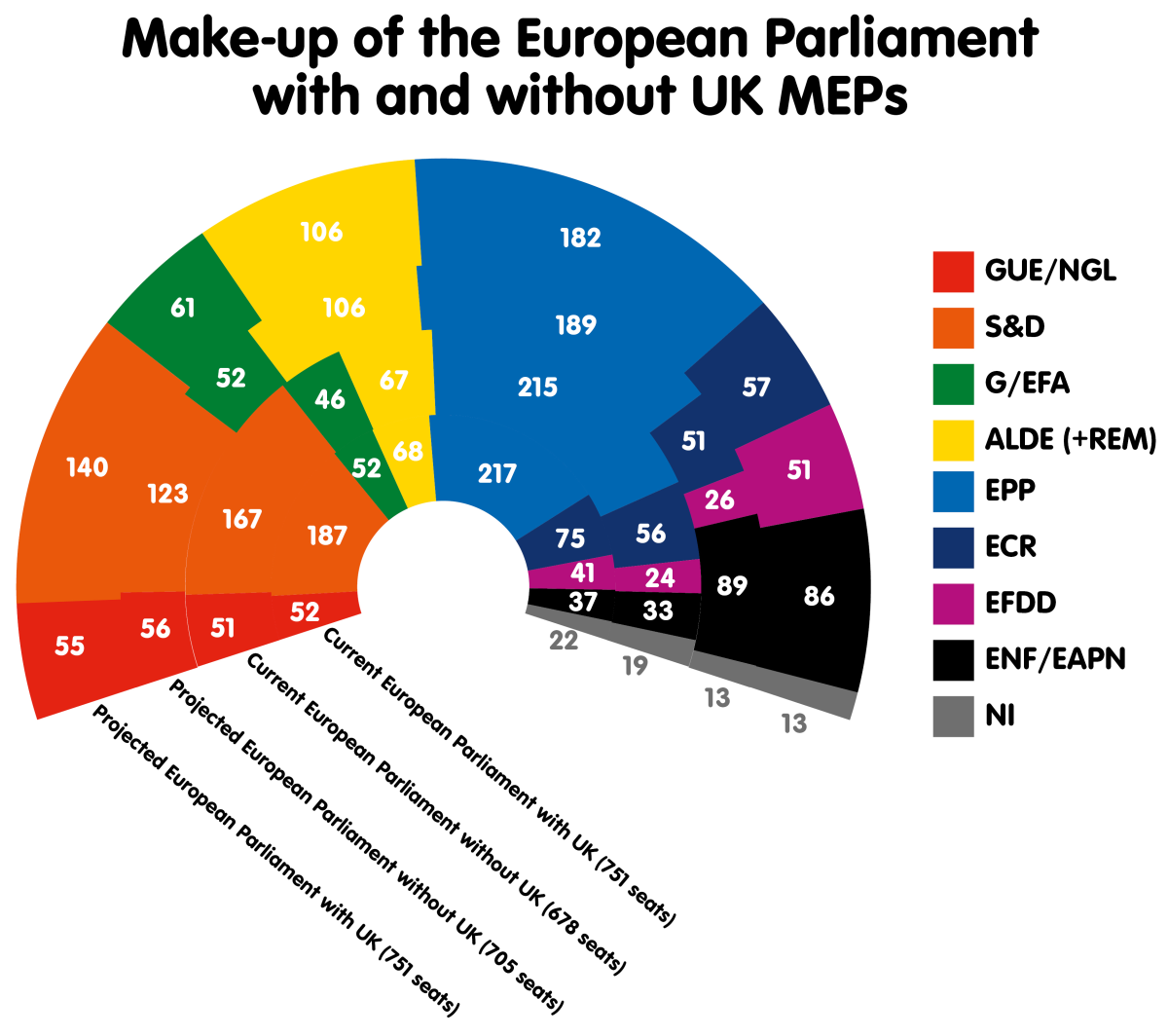

The following graphic shows:

- current seats – the number of seats each political group currently has in the European Parliament; and

- projected seats – the number of seats each political group would win if a European Parliament election were held today and each national party performed as predicted by our statistical model (which adjusts for national election opinion polls using the methodology described above).

The results show the make-up of the European Parliament, currently and after the May 2019 vote, both with and without the 73 UK MEPs. We calculate that the coalitions that would be formed in these two scenarios are:

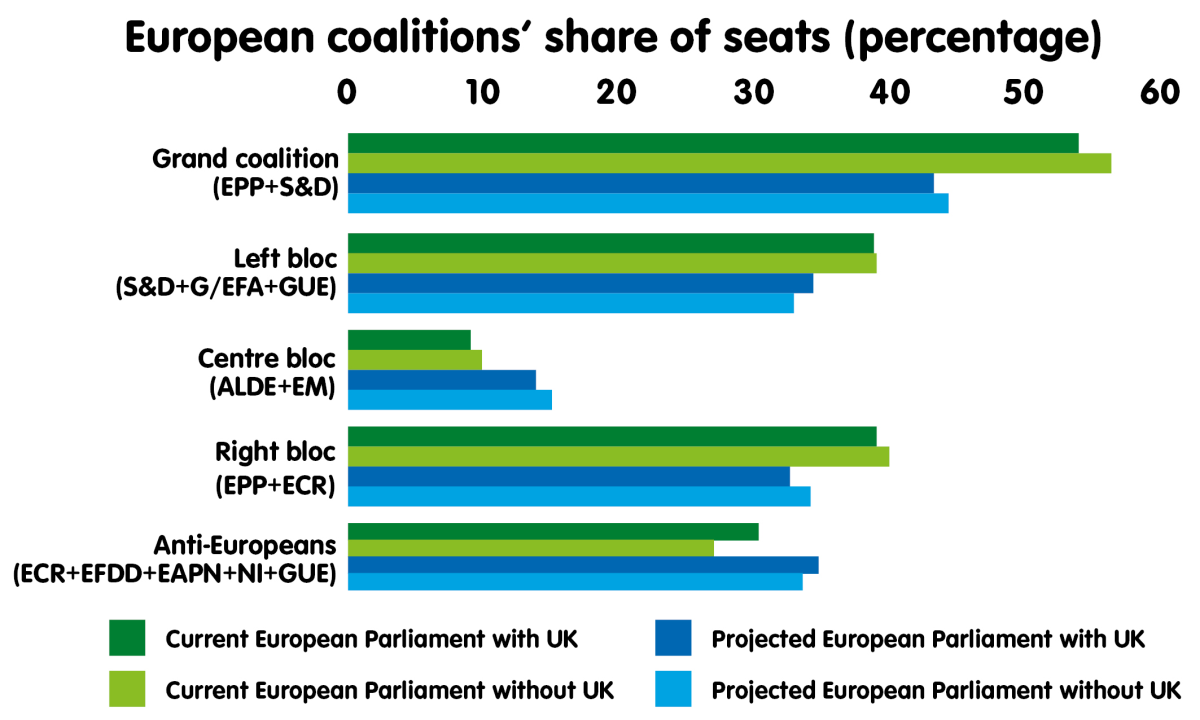

This suggests that, with or without UK participation, there is a strong possibility that anti-European parties could form the second-largest coalition in the European Parliament after the May 2019 election. Aside from the grand coalition, there are three overlapping blocs in the European Parliament: the left bloc, the right bloc, and the anti-European bloc. Regardless of whether the UK participates in the election, the three blocs will each constitute roughly one-third of the parliament. The next European Parliament will be finely balanced between competing groups, as the left bloc will be on 34 percent while the right bloc – comprising the EPP and the European Conservatives and Reformists – will be on 32 percent. The anti-European Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy will account for 20 percent when combined with non-attached parties. Added to the European Conservatives and Reformists and the Nordic Green Left, this figure rises to 35 percent. Meanwhile, the grand coalition could combine with ALDE to make up 57 percent, or with the Greens to make up 51 percent.

If the UK participates in the election, it is likely that the left bloc – comprising social democrats, the European United Left–Nordic Green Left to their left, and the Greens – will be marginally larger than the right bloc. If the UK does not participate, the right bloc will remain the largest group in the European Parliament, followed by anti-European parties. However, in the event of a strong performance by far-right anti-immigration parties in the election, Orbán may decide to take Fidesz out of the EPP to work with anti-European forces. This could prompt the parties furthest to the right in the EPP to also splinter off from the group, having decided that it is no longer their natural home.

In either scenario, the centre bloc looks set to be the smallest – but also a significant – force, making important gains from its current position as La République En Marche! participates in the election for the first time. How and with whom the bloc chooses to work in the next European Parliament will, therefore, be critical in edging either the left bloc or the EPP significantly ahead of anti-European parties in the election.

Thus, in the campaign phase, it is important for all pro-European parties to think about issues that mobilise pro-Europeans across party boundaries. Messages that resonate beyond parties’ bases will be important in building a platform on which to work together after the election. ECFR’s research with YouGov indicates that climate issues could form part of this platform: in the 14 countries in which we asked whether climate change should be tackled as a priority even at the risk of curbing economic growth, only a minority of people responded in the negative. In our surveys, respondents cited cooperation on climate change as one of the biggest losses that would result from the EU’s collapse. And voters concerned about green issues do not only vote for Green parties – those who worry about having access to clean air include significant numbers of Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union supporters in Germany and Law and Justice party voters in Poland. In Italy, such voters are evenly spread between the Democratic Party, the Five Star Movement, and the League.

Methodology

Our methodology is based on the historical relationship between the outcomes of European elections and public opinion polls. Our estimates for each country are based on the following three sources of information.

Firstly, for 16 countries, we used at least one poll on how respondents will vote in the European Parliament election.1 This poll was weighted on past votes and demographics. We adjusted our analysis of the poll data according to the likelihood that respondents will vote and whether they voted in the 2014 European Parliament election. The impact of this turnout adjustment varies by country, according to historical patterns. For example, between 2009 and 2014, turnout in the European Parliament election averaged just 16.3 percent in Slovakia, but 90 percent in Belgium (where voting is compulsory). In Slovakia, therefore, the adjustment was more significant. It revealed that, for instance, supporters of the country’s most popular party, Direction – Social Democracy (SMER), are less likely to turn out than most other citizens – which reduced the party’s vote share in our results. The approach reflects evidence from the 2014 election, in which SMER won a far smaller share of the vote than opinion polls suggested it would.

The second source of the estimates is publicly available national opinion polls. We use a model based on the historical relationship between opinion polls at the national level and outcomes at the European Parliament election. The second-order model of electoral behaviour at European elections has been refined by taking into account the way in which the relationship between national opinion polls, general election results, and the results of the 2014 European Parliament election varies according to the timing of the electoral cycle. We use the median vote share figure for the three most recent polls (the oldest of them taken in January 2019) and apply the model accordingly.

The final source includes additional polls specific to the European election in some countries, to identify any additional country-specific features: for example, the relative popularity of some parties in European elections, the emergence of European election coalitions (such as the Amsterdam Coalition in Croatia), and other arrangements between political parties specific to this European Parliament election (such as Denmark’s Red-Green Alliance and People’s Movement Against the EU).

We allocate seats using the electoral rules for converting votes into seats in each country. (For seat predictions by country, see the annex to this paper.)

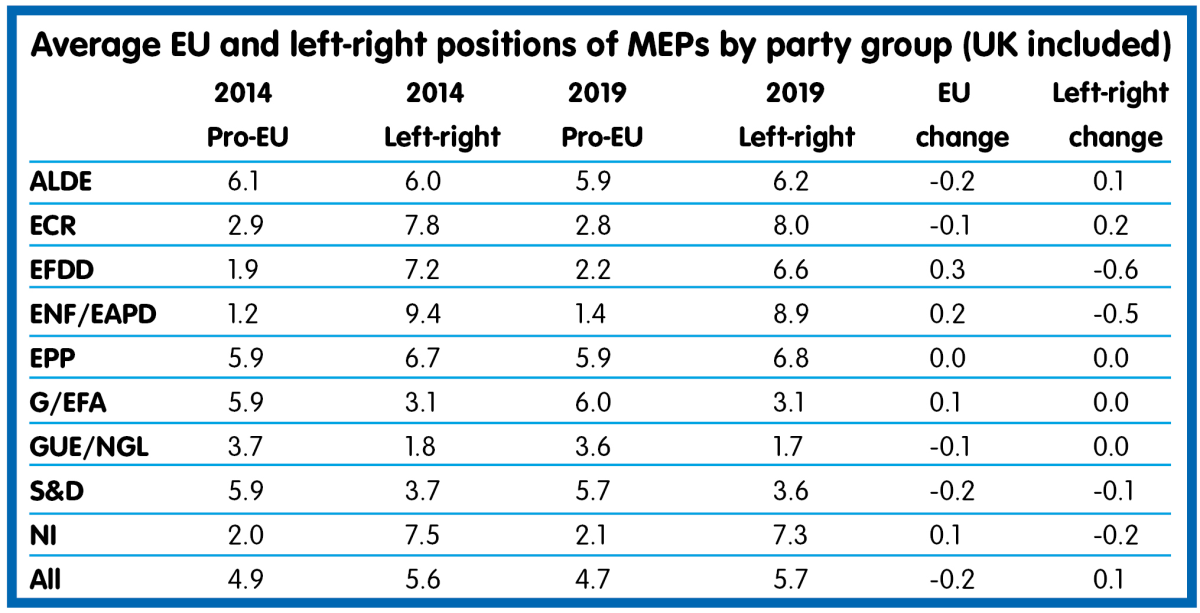

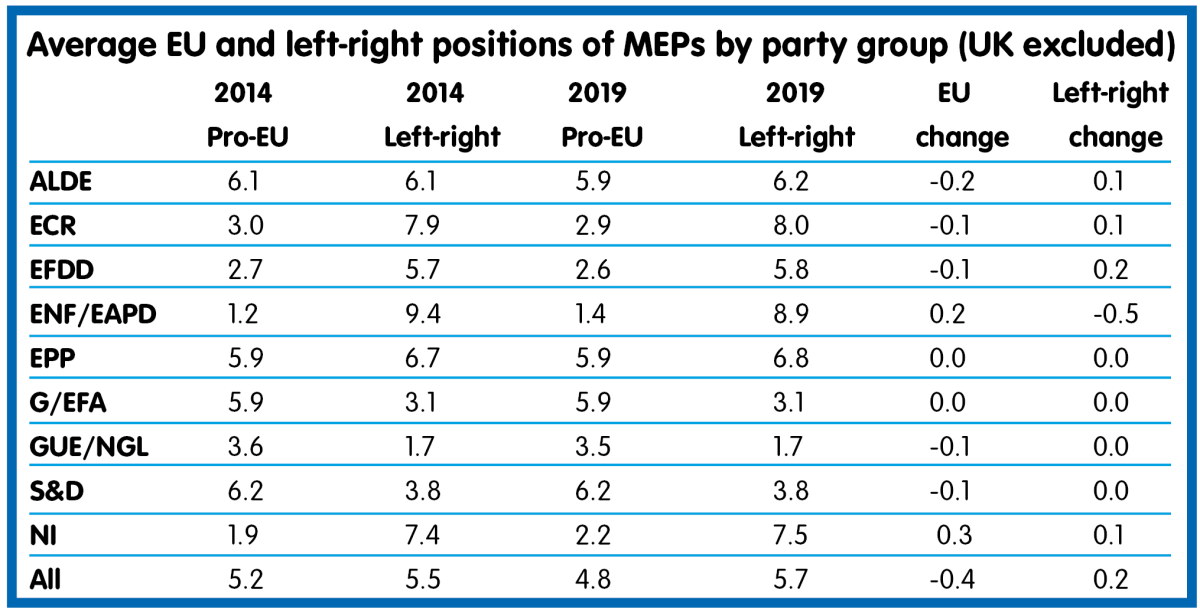

The rise of Euroscepticism within parties

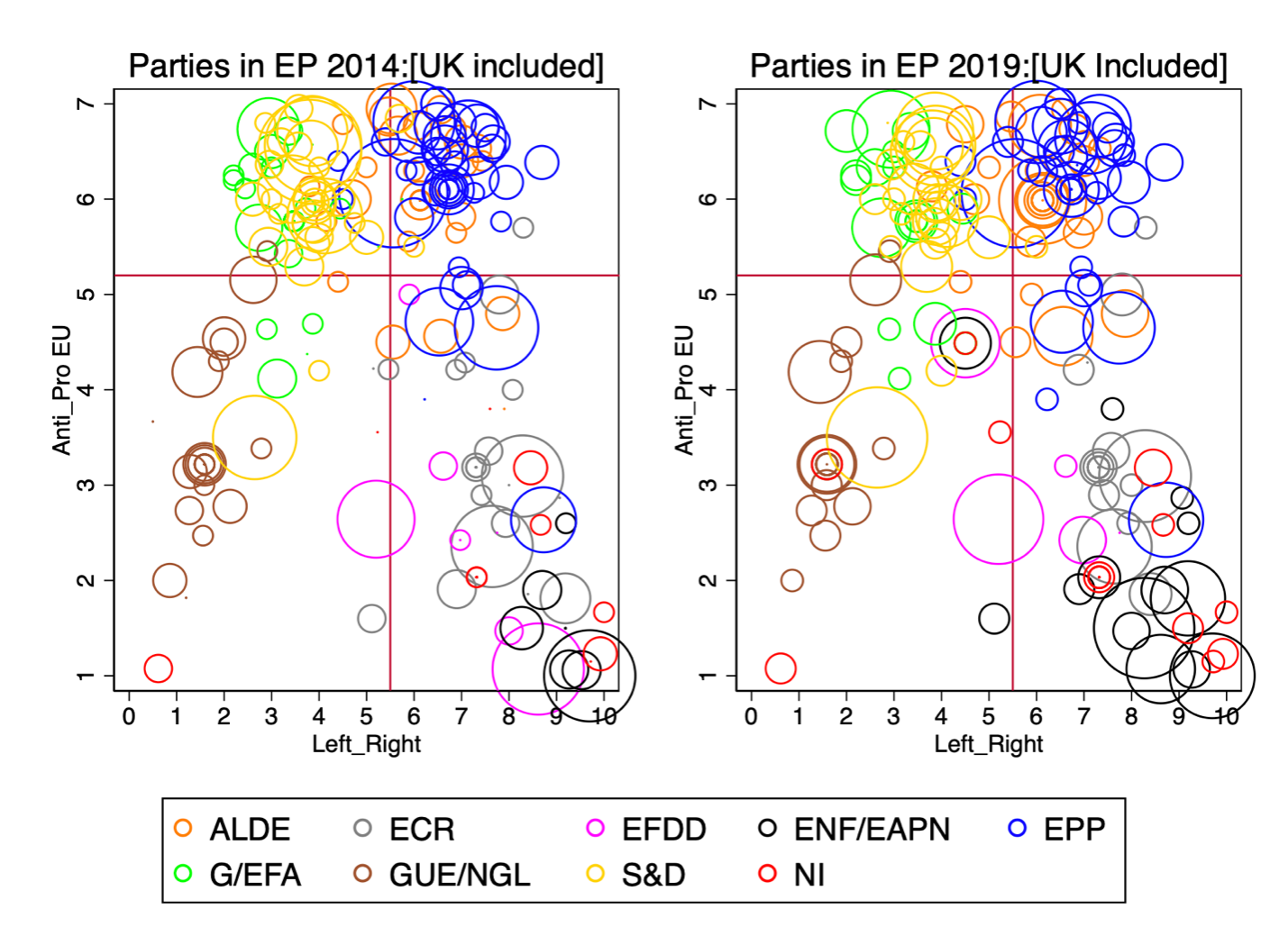

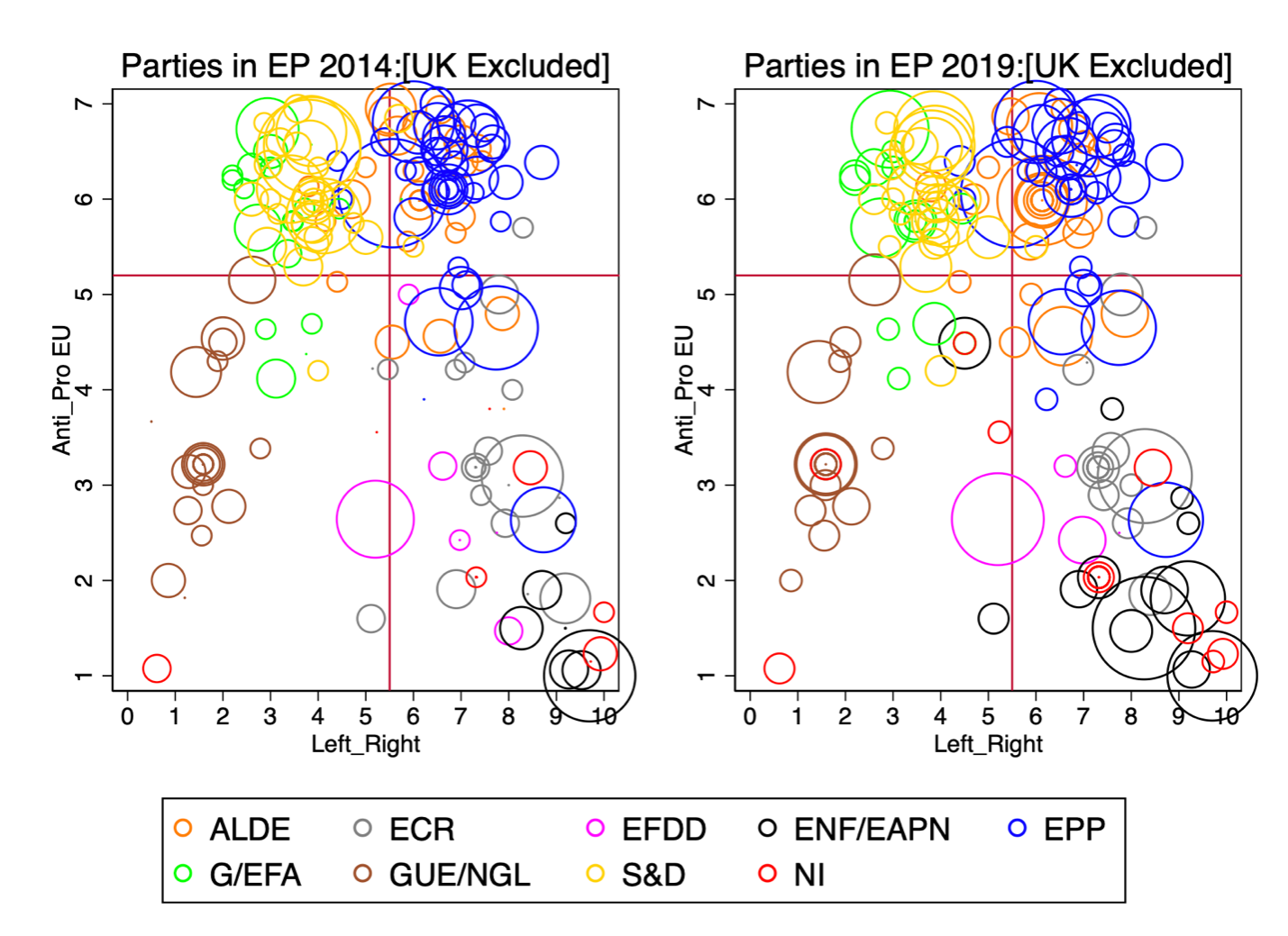

In addition to looking at the likely group composition of the European Parliament following the election, we also explore the likely positions of MEPs within party groups. In this, we make use of a data set compiled by researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who have surveyed expert panels of political scientists to locate parties’ positions on many issues in recent years. We make use of two recent surveys, one from 2014 and the other from 2017 – the latter of which was limited to just some countries. We look at parties’ positions on issues in two dimensions. The first is a general measure of EU support, on a scale of 1 (strongly oppose) to 7 (strongly favour); the second is a general measure of position on the political spectrum, on a scale of 0 (extreme left) to 10 (extreme right). We assume that individual MEPs’ positions will be equal to their parties’. Where data is missing for a party, we place it at the mean of the parties in its group. For 2017 data, we interpolate data only for parties missing even 2014 data and calculate the mean using a mixture of 2014 and 2017 data.

Table 1 shows the difference between the 2014 and projected 2019 parliaments, using the latest available judgments of expert panels. On average, following the May 2019 European Parliament election, MEPs will be marginally more right-wing and marginally less positive about the EU. Table 2 shows the differences with the UK excluded, suggesting that the European Parliament will have a slightly more Eurosceptic slant after Brexit, with no group becoming more pro-European than it was in the previous parliament.

The following charts show national parties’ positions on the political spectrum and their attitudes towards the EU. The size of each coloured circle reflects relative party size. Although the 2019 parliament will be significantly more critical of Europe than the current one, changes in the overall composition of the parliament will be moderate in comparison to dramatic elections at the national level.

How certain are we?

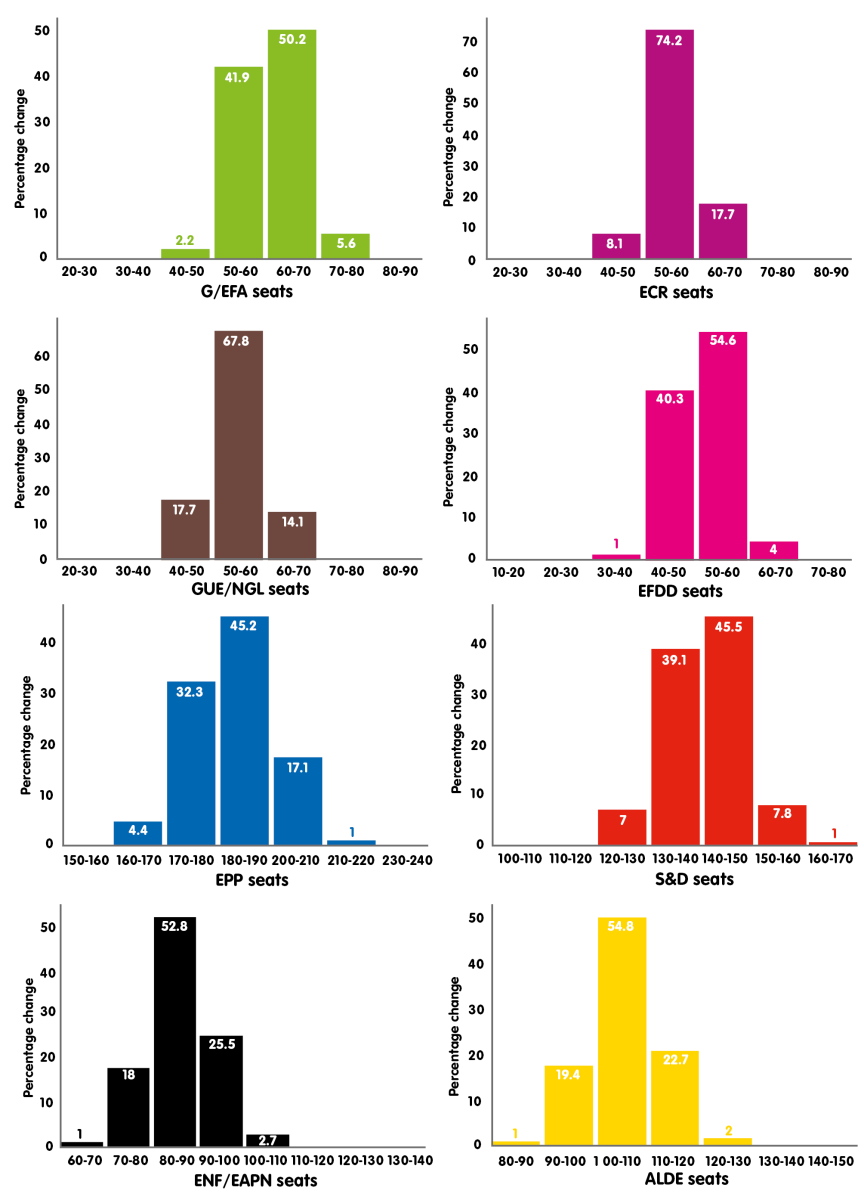

All our estimates come with some degree of uncertainty. To estimate the magnitude of that uncertainty, we looked at the extent to which predicted vote shares for each national party one month before the 2014 election differed from the actual vote share for that party. Using this information, we simulated 10,000 results for the 2019 European Parliament election.

Based on our assumption that the UK will take part in the European Parliament election, there is a 45 percent chance that the EPP will win between 180 and 190 seats and a 95% chance that the group will win between 170 and 200 seats. We list the details for each party group in the charts below. For the largest groups in the European Parliament, there is an approximate 50 percent chance that our top-line estimates will be within 5 seats of the result and a 95 percent chance that they will be within 15 seats of the result. (There is a slimmer margin of error for smaller party groups.)

There are limitations to these estimates of uncertainty. Our model is a simple estimate of the state of play at this juncture. There are three known uncertainties beyond those our model can approximate. Firstly, our model does not account for the possibility of pan-European attitudinal changes, such as a drift towards or away from the anti-EU populist right between now and polling day. Secondly, our model does not account for any changes to the baseline projected composition of turnout. If voters with pro- or anti-European attitudes, or younger voters, turn out more or less than in previous elections, this could also affect the accuracy of our estimates. We cannot predict how the campaign will develop. Finally, our model cannot anticipate changes in the composition of party groups, as determined by national parties’ movement from one of the groups to another. This is particularly relevant for the emergence of the new European Alliance of Peoples and Nations group.

Conclusion

We predict that anti-European parties will perform strongly in the European Parliament election. There is a distinct possibility that they could form the second-largest political group in the parliament. With UK participation, they could be second only to the left bloc. If the UK somehow avoids participating in the vote, they are still likely to be the second-largest group, albeit with the EPP the largest. In either scenario, the European Parliament will be finely balanced between the three largest groups, meaning that the centre coalition will have a potential kingmaker role in forming deals between the groups.

There will not necessarily be major changes to the EU the day after either outcome in the European Parliament election. Anti-European parties constitute a multifarious group, coming from the far right and the far left with policies and priorities that are most often grounded in their national politics. Their ability to work together as a group is far from proven.

However, our estimates suggest that pro-European parties – in the EPP, the left bloc, and the centre bloc – can no longer delay their attempts to think beyond traditional political families in the way they battle for seats in the European Parliament. Everything will depend on the coalitions that these mainstream parties form between one another, and on how they work to disrupt the formation of anti-European coalitions in the next parliament.

Although the UK’s participation or lack thereof should only determine which mainstream bloc the anti-European parties will be in second place behind, the country’s role will be critical to the battle of ideas in this election campaign. The UK’s participation would risk convincing anti-European parties that the EU is irreformable: they will make the argument that the UK wanted to leave the club and was not allowed to do so.

This argument is potentially powerful given that three-quarters of Europeans believe that either their national system or the European system – or both – is broken. And two-thirds of them believe that their children’s lives will be worse than their own.2 It is, therefore, crucial that mainstream parties think about how to position themselves as symbols of change, in an environment in which anti-European parties will portray them as defenders of the status quo in Europe.

Both sides can play this game. Pro-European parties should try to characterise Italian Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini’s drive for a “Europe of Common Sense” as a status quo debate.3 They should argue that the EU has been stuck for too long in a discussion about what it should be – now, the challenge is to change it. Pro-European parties should focus their message on the issues they want Europe to deal with after the election, not on EU institutions. These issues will vary from country to country, but many European voters prioritise affordable housing, inclusive economic growth, social integration and cohesion, the fight against corruption, and action to mitigate climate change. Pro-European parties must disseminate their messages in the next month and, immediately after the European Parliament election, begin to deliver on their promises.

About the authors

Simon Hix is Pro-Director for Research and the Harold Laski Professor of Political Science at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He is a Visiting Fellow at ECFR. He has written over 150 books, academic articles, policy papers and research-related blogs on European and comparative politics. In 2008 he won the Fenno Prize from the American Political Science Association (APSA) for his book (with Abdul Noury and Gerard Roland) Democratic Politics in the European Parliament (Cambridge, 2007). In 2005 he won APSA’s Longley Prize for the best article in 2004 on representation and electoral systems. In 2004 he won a Fulbright Distinguished Scholar Award, and in 2011 became a Fellow of the British Academy. Simon is also (pro bono) chairman of VoteWatch.

Michael Marsh is Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Trinity College Dublin and a member of the Royal Irish Academy. He has written and edited a number of books, including The Irish Voter (Manchester University Press, 2008), which won the Political Studies Association of Ireland’s best book of 2008 prize, How Ireland Voted 2016: The Election that Nobody Won (Palgrave, 2016), A Conservative Revolution?: Electoral Change in Twenty-First Century Ireland (Oxford University Press, 2017) and The Post-Crisis Irish voter: Voting Behaviour in the Irish 2016 General Election (Manchester University Press, 2018). In addition, he has published more than 100 professional articles and book chapters on parties and elections. He has served as a principal investigator for the Irish election study, and was part of a team running pan-EU surveys in European Parliament elections between 1991 and 2009.

Kevin Cunningham is a lecturer in Political Science at TU Dublin. A political strategist and former Targeting and Analysis Manager for the British Labour Party, Kevin has worked as a consultant for the British Labour Party, the Irish Labour Party, the Australian Labor Party, and Social Democratic and Labour Party in Northern Ireland. He also specialises in the politicisation of immigration and worked for three years as a researcher on a European Commission-funded project to understand the politicisation of immigration. His work on the predictive capacity of odds in elections has been published in the Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties. His latest work focuses on campaign effects.

1 This survey took place in February 2019 in Belgium and Finland, and in March 2019 in Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, and Sweden.

2 Drawn from data from a survey of 14 member states carried out by YouGov for ECFR in February 2019.

3 Launched at a conference of anti-European parties from across the EU on 8 April 2019 in Milan.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.