The instinctive multilateralist: Portugal and the politics of cooperation

Summary

- The Portuguese people believe that their country’s fate is inextricably tied to that of the European Union.

- A survey carried out ahead of the Portuguese national election suggests that the Portuguese bounced back quickly from a surge in Euroscepticism linked to the strict conditions of Portugal’s 2011 bailout package.

- Portugal values the economic benefits of EU membership primarily, but its people believe in the EU as more than just an economic project.

- The Portuguese are instinctive multilateralists, and hope that the bloc can help them tackle the challenges of globalisation: from climate change to cooperation on the impact of freedom of movement on Europe.

Introduction

Portugal’s politics is out of step with much of the European Union. The United Kingdom is imploding over Brexit; a fragile Italian government has unified around the goal of preventing an election at a time when far-right, anti-EU parties are rising in the polls; Marine Le Pen’s nativist Rassemblement National holds more French seats in the European Parliament than any of its rivals; and Poland’s upcoming election promises a tough fight between a liberal, internationalist vision of the country and a traditional, nationalist one. Portugal’s political environment, by comparison, remains unusually stable.

Since applying to join the European Economic Community in 1977, Portugal has been consistently pro-European. Following 40 years of dictatorship, Portuguese citizens saw the appeal of the extra layer of protection provided by the European acquis. The creation of the single market in 1993 has greatly benefited a country so reliant on international commerce: other EU member states now account for more than 70 percent of Portuguese trade. And, as a multilateralist and globally engaged nation, Portugal strongly identifies with the vision of the Common Foreign and Security Policy the EU laid out in the 2007 Lisbon Treaty.

These characteristics do not set Portugal apart from the many of the EU countries that have experienced strong growth in nationalist, populist, and anti-European parties in the past decade. Moreover, having suffered under the strict conditions of a financial bailout package the EU and the International Monetary Fund provided in 2011, Portugal had begun to show some signs of EU fatigue in recent years. Yet the country appears to buck the general trend in Europe towards parties that question whether the EU has overreached, whether it should be reconceptualised as a Europe of sovereign nations, and whether a nation-first approach is more appropriate in a highly competitive international environment.

As Portuguese citizens prepare for a national election on 6 October, they are largely debating issues such as climate change, economic development, and political stability. In many other EU member states, the last two of these issues have often formed the basis for discussions of a country’s relationship with the EU. Not so in Portugal. The election campaign has seen the emergence of a string of new pro-EU parties, ranging from PAN (the People, Animals, and Nature party) to Iniciativa Liberal and the centre-right Aliança. The only exception is the right-wing, Eurosceptic Chega (Enough), which is widely expected to have no significant impact on the vote (or, at least, not on the same scale as its Spanish equivalent, Vox).

To understand why Portugal is different, and whether there are lessons for the rest of the EU in how the country handles the debate on its future, ECFR commissioned YouGov to carry out a survey of 1,000 people in Portugal in the first week of September 2019. This paper analyses the findings of this survey, and unpacks what the results imply about Portugal’s views on the EU and the world.

A sense of optimism

The results of the survey suggest that the Portuguese have a relatively bright outlook on the future, and that their fear of the future has steadily diminished since Portugal’s last national election, held in 2015. Like their counterparts in Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Spain, and Sweden, most people in Portugal described their predominant feeling about life as being “optimistic”. However, the second to fifth most common answers they gave to ECFR’s survey – “devalued”, “stressed”, “pessimistic”, and “sad” – suggest that their feelings about the world involve a strong sense of saudade (the celebrated Portuguese word for a mixture of nostalgia and fate).

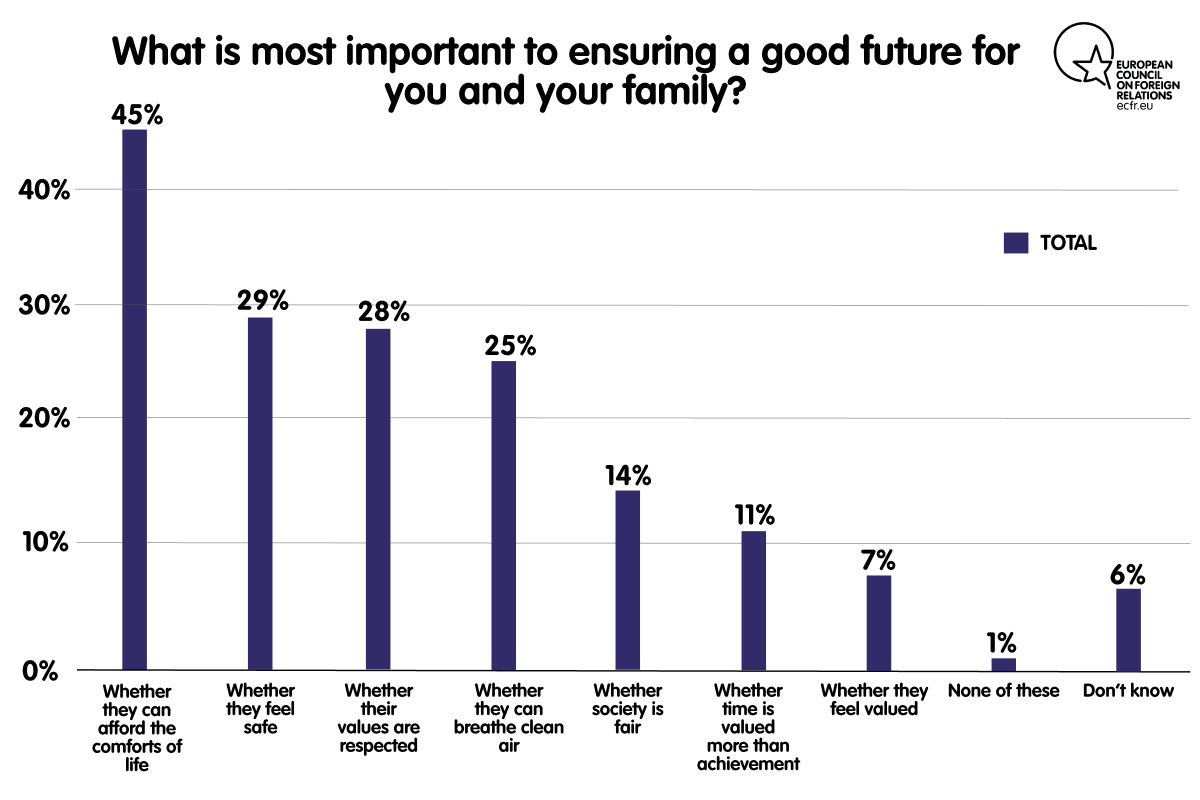

Portugal’s relationship with the EU is deeply rooted in the economic benefits of membership – as is clear from the most common answers to ECFR’s survey questions on the threats facing Europe, ranging from foreign policy priorities to the biggest losses from the bloc’s potential collapse. Forty-five percent of Portuguese respondents saw “being able to afford the comforts of life” as the most important factor in ensuring a good future. By comparison, just 29 percent saw “being able to feel safe” in this way. In no other country was there such an evident preference for economic success over the other options. However, Portugal is not immune to the phenomenon of Euro-pessimism that ECFR discussed in “What Europeans really feel”, a paper published earlier this year. While Portuguese citizens’ support for the European project remained strong, they were not necessarily sure that it would survive. Only 35 percent of respondents thought it unlikely that the EU would fall apart in the next 10- 20 years. Given the strong sense of the EU’s importance to their economic future, this perhaps goes some way to explaining the stress, pessimism, and sadness in their feelings about the world.

But there is also a clear belief in Portugal that, in the current global environment, the EU is more than just an economic project. The Portuguese hope that the bloc can help them tackle challenges in everything from the mitigation of climate change to cooperation on the impact of freedom of movement in Europe. After Portugal’s election, it will be down to the new government to push the EU to deliver on these areas – and to prove to the Portuguese that their faith in the union is not misplaced.

Corruption and European unity

Although the effects of the financial crisis and the resulting bailout have markedly diminished since 2015, economic issues continue to top the list of Portuguese voters’ concerns. They regarded another financial crisis and a trade war as the biggest potential threats the EU faced. Nonetheless, Portugal’s economy is performing relatively well: the OECD projects that the country will experience GDP growth of around 2 percent per year in 2019 and 2020. Similarly, the country’s annual exports have doubled in value since the turn of the century, while its tourism sector is booming like never before.

Yet, despite these causes for optimism, the Portuguese continued to see the economic horizon as partially clouded by uncertainty and risk. Their memories of the last crisis doubtlessly account for this to some extent. But, more importantly, the country’s economy has long been fragile, creating persistent anxiety about the future. A desire for economic development and the need to consolidate democracy were the main reasons why Portugal became a member of the European common market, in 1986. Thirty-three years on, the Portuguese still look to Europe for economic safety. They particularly value the euro.

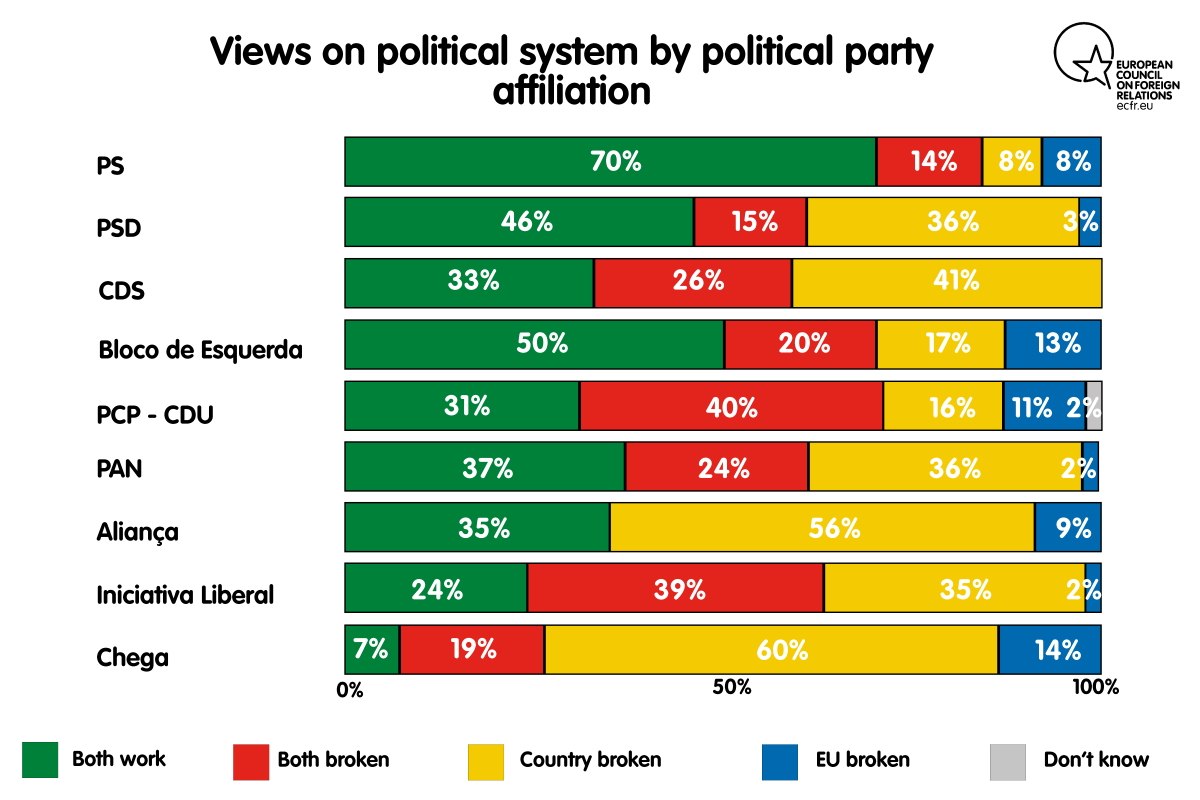

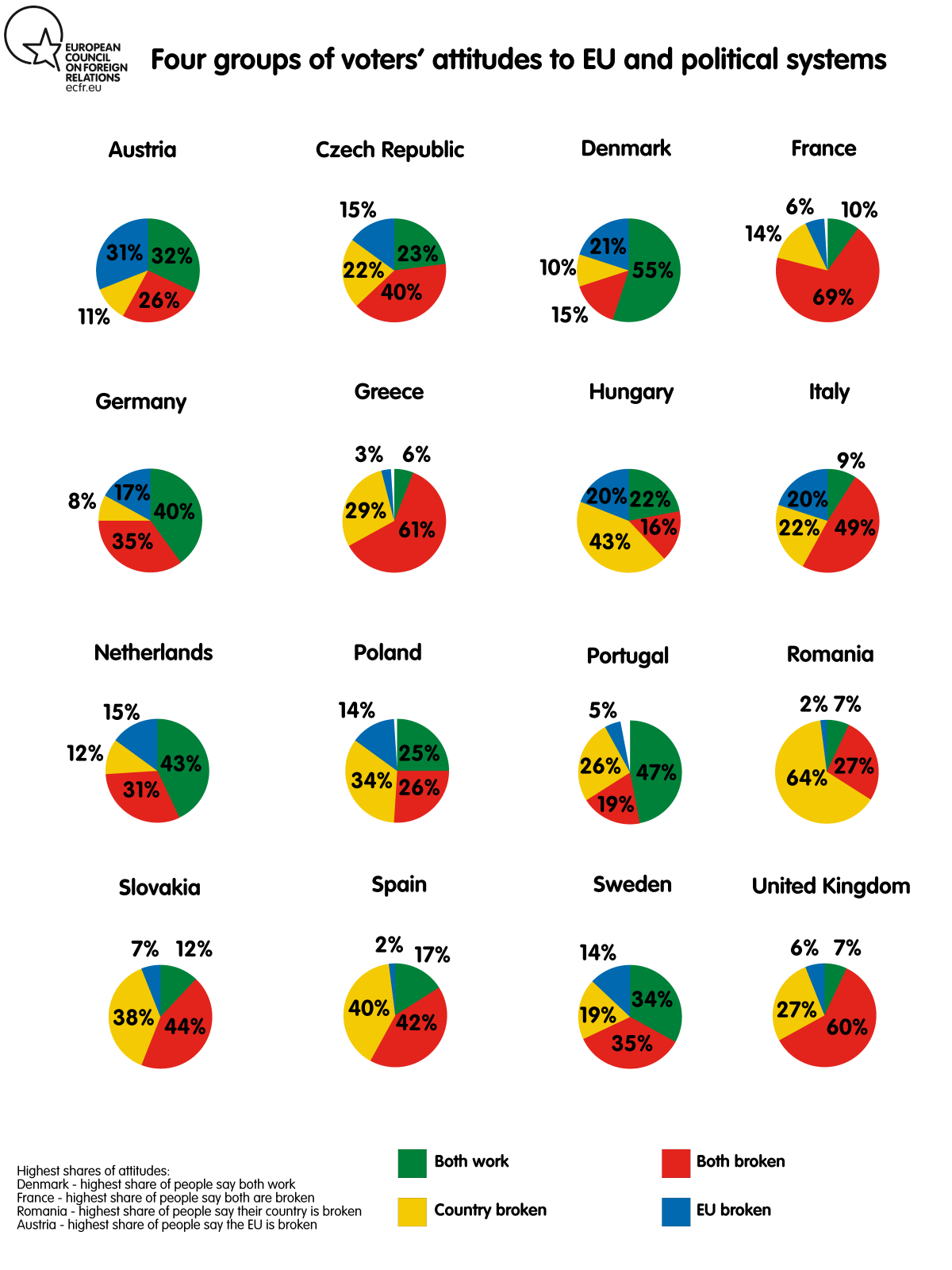

During the crisis years, there was a strong consensus among the Portuguese that Brussels was as responsible for the decline in their living conditions as Lisbon – or perhaps even more so. This is because they directly associated EU institutions with the financial bailout. Yet, in the past few years, there has been a fundamental change in public perceptions of the EU’s political system. According to ECFR’s survey, 58 percent of Portuguese felt that the EU system worked somewhat well, while 44 percent of them believed that the national political system was broken. This seems to confirm that, while the EU’s reputation has made a swift comeback, there has been no such recovery at the national level.

The survey suggests that the explanation relates to corruption. Although the Portuguese acknowledge that corruption is an important issue in various parts of Europe, only 41 percent of them see it as a major issue in central and eastern Europe while 64 percent view it as a significant problem for Portugal. Their concern likely stems from the ongoing trial of José Sócrates, Portugal’s prime minister between 2005 and 2011, on charges of corruption and money laundering. The case is based on a wide-ranging investigation that has drawn in other high-profile Portuguese figures, including the former heads of the Espírito Santo banking empire and Portugal Telecom. Both these entities, once widely viewed as examples of Portugal’s modern-day success, have since collapsed, inflicting huge losses on investors and taxpayers. More recently, smaller corruption cases (involving politicians, local administrators, and businesses) have also garnered a great deal of public attention following investigations by the media and the police.

Although the government has made a sustained effort to foster integrity and strengthen anti-corruption measures in the public and private sectors, the Portuguese believe that both the executive and the judiciary remain reluctant to fight high-level corruption. Indeed, 50 percent of all respondents to ECFR’s survey said that there were no political leaders they personally trusted. As such, it should be no surprise that Portugal received a mark of 64 out of 100 in the 2018 edition of Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (on which lower numbers indicate higher perceived corruption). This is a moderately poor result for an EU member state, placing Portugal in a group largely made up of the countries that joined the bloc in the 2000s (Spain is also in this group).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, supporters of the Socialist Party – which has been in government since 2015 with parliamentary support from the Communist Party and Bloco de Esquerda – were much more optimistic than the average voter: 70 percent of them thought that both the national and the European political systems worked fairly well. The most pessimistic group comprises Portuguese aged between 35 and 44 years old, only 33 percent of whom believed that both systems worked. Strikingly, 50 percent of Bloco de Esquerda voters believed that both systems worked, while only 20 percent thought that both were broken. This finding is peculiar because these voters blamed the fallout from the financial crisis on the EU and Portuguese political systems. The new trend may indicate that, having emerged at the turn of the century as a protest movement very much like Syriza in Greece or Podemos in Spain, Bloco de Esquerda has now become a part of mainstream politics.

The views of respondents from the other political parties are more mixed. Yet 53 percent of Portuguese were convinced that EU membership often protected Europeans against the excesses or failures of national governments. Thus, the EU continues to have a strong reputation in Portugal.

Tradition and progress

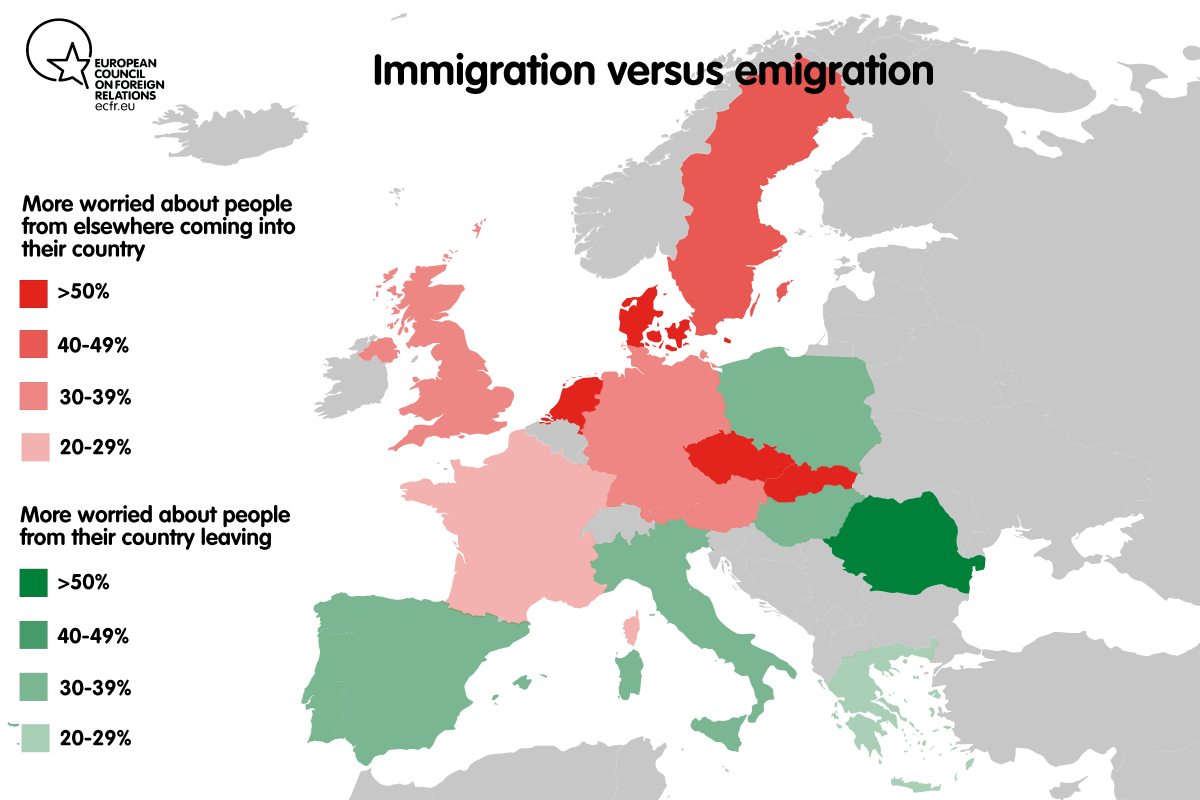

Despite the positive trends discussed above, there may be a dark cloud looming over Portugal’s relationship with the EU: the challenge of managing the tension between economic development and the domestic impact of freedom of movement within the union. A pan-European survey ECFR carried out in the run-up to the May 2019 European Parliament election shows that, while freedom of movement remains popular across the EU, the challenges of living with its effects are becoming increasingly apparent. In countries such as Greece, Italy, Poland, and Spain, Europeans are more worried about nationals leaving their country than new arrivals coming in. Portugal appears to be no exception to this trend.

Overall, Portuguese citizens are less preoccupied with migration than many of their counterparts in other EU countries. Although they regard migration as the fourth-biggest threat the EU faces, the Portuguese view the freedom to live and work in other countries as the second-biggest loss from the EU’s potential collapse. Indeed, while Portugal has a centuries-long tradition of emigration to the Americas, Africa, and elsewhere, most Portuguese emigrants have moved to other parts of the EU in recent years. According to estimates by the United Nations, in 2017, around 22 percent of people born in Portugal lived outside the country, two-thirds of them in another European nation.

However, a close inspection of the data suggests that the Portuguese may be more anxious about this situation than the headline figures indicate. While 41 percent of respondents were equally concerned about immigration and emigration, 30 percent were more worried about emigration and just 15 percent about immigration.

Given their strong preoccupation with economics and demographic challenges (an ageing population registered as the third-biggest threat, likely because Portugal had the fourth-lowest birth rate in the EU), the Portuguese may be largely concerned about emigration due to brain drain and the loss of the working-age population. But there may also be a cultural component to this, in a country where family and personal networks are hugely important. Interestingly, Portuguese who saw themselves as better off than their parents outnumbered those who saw themselves as worse off (45 percent compared to 28 percent). This contrasted with other EU countries, where 42 percent of people felt that they were worse off. Distance from loved ones facilitated by freedom of movement may have contributed to this sentiment.

Unless European leaders carefully manage the tension between the economic benefits and social concerns created by freedom of movement, this could increasingly damage Portuguese attitudes towards the EU. While Portuguese aged 18-34 cited freedom of movement as the biggest loss from the EU’s potential collapse, they may be less inclined to take advantage of it than previous generations were. This is because they were the age group most likely to believe that they had a higher quality of life than people in other EU countries. They were also more likely to believe that the EU would collapse in 10-20 years than any group aside from those aged 35-44. Thus, freedom of movement may have something to prove among young Portuguese – unless their tendency to believe that they have a higher quality of life in their own country discourages them from emigrating, thereby easing tension over the issue.

Portuguese citizens’ focus on family and community does not appear to have detracted from their concerns about major international issues. They view climate change as the second-biggest threat Europe faces (19 percent of them regard this as the biggest threat, just shy of the 20 percent who viewed the financial crisis in this way). According to the survey ECFR carried out following the last European Parliament election, only citizens of Germany and the UK paid this much attention to climate change. Although European politics experienced a “Green wave” in the election, the Portuguese have long been concerned about the issue. Indeed, judging by a survey of European policymakers ECFR carried out in 2010 for the report “European security: The spectre of a multipolar Europe”, climate change has been one of Portugal’s top three concerns for at least a decade.

In June and October 2017, huge forest wildfires linked to global warming claimed the lives of 115 people in Portugal, elevating the importance of this topic on the Portuguese political agenda. Yet ECFR’s data suggest that Portuguese environmental concerns go far beyond the direct impact of climate change at home. The Portuguese saw access to clean air as the fourth most important factor in a good future, after the ability to afford the comforts of life, safety, and respect for their values. They appeared to view climate change as a threat that required a response at the European level, underlining their strong multilateralist instincts.

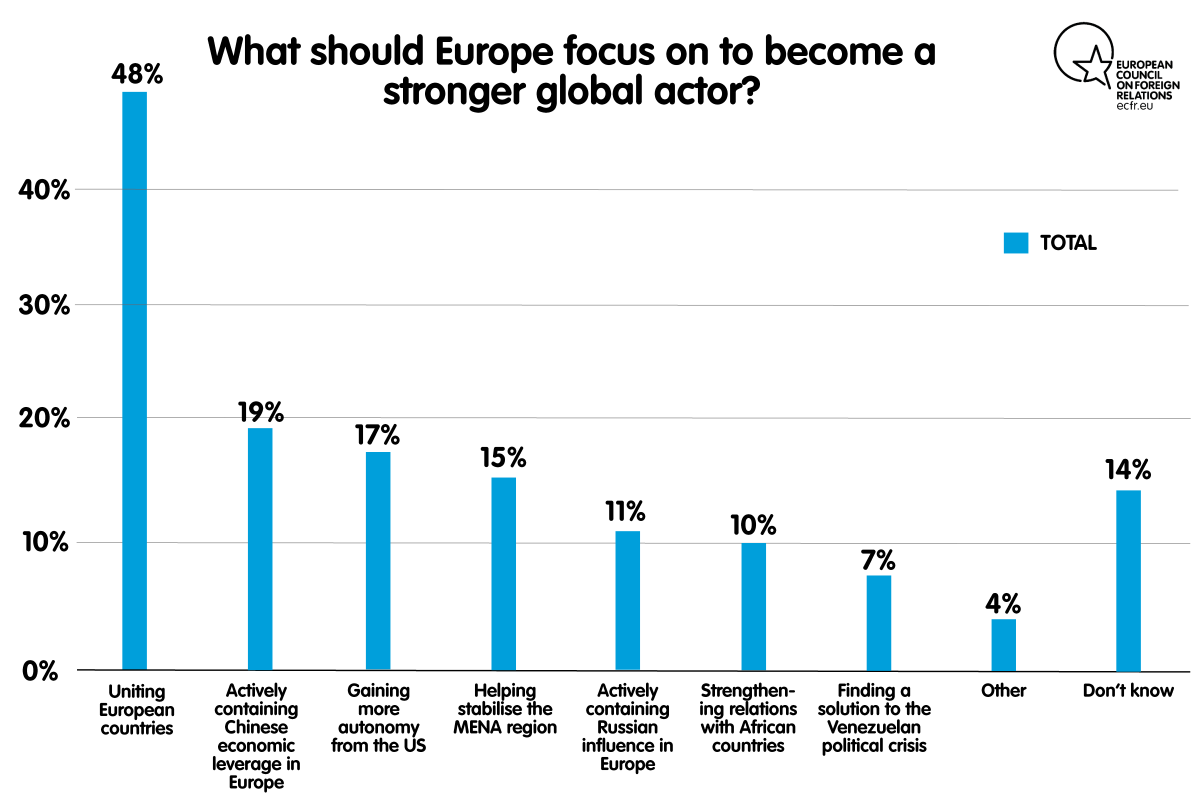

As a relatively small, outward-looking country, Portugal sets great store by cooperation within the international system to maximise its influence. This approach has allowed it to punch well above its weight in some senses, with José Manuel Barroso holding the presidency of the European Commission during 2004-2014, António Vitorino serving as the current director-general of the International Organization for Migration, Mário Centeno as the president of the Eurogroup since 2018, and António Guterres as UN secretary-general since 2017. The Portuguese are highly critical of unilateralism and non-cooperative behaviour: in ECFR’s survey, 48 percent of them believed that strengthening European unity was the most important factor in improving the EU’s position as a global actor. Therefore, if the European Parliament confirms Elisa Ferreira as the EU’s new commissioner for cohesion and reform, her work over the next five years should closely align with the interests of other Portuguese people. This is likely why the Portuguese government invested significant political capital in attempts to secure this role for her. If vice-president designate Frans Timmermans helps European states create a Green New Deal, this would reinforce Portuguese faith in EU institutions even further.

The importance of geopolitics

Foreign policy has never been an influential topic in Portugal’s electoral campaigns. During European Parliament elections, which the Portuguese have always seen as second-order national elections, even European topics become nationalised. This is because there is a consensus among the political parties that have formed a government (the Socialist Party, the Social Democratic Party, and the Christian Democrat Party) on a foreign policy based on three priorities: the north Atlantic alliance, Europe, and the Portuguese-speaking Commonwealth. From one election to the next, these parties usually maintain the same stances on the European project and EU foreign policy. This continues to be the case, albeit with some slight variations.

For more than eight centuries, close political and economic cooperation with England was the central feature of Portugal’s foreign policy. The countries first established a formal alliance in 1386 – one that, still relevant today, constitutes perhaps the oldest of its kind in the world. Sharing a clear Atlanticist perspective, both Portugal and Britain viewed international politics in much the same way during the twentieth century, including – until fairly recently – all European matters. In 1949 Portugal was invited to become a founding member of NATO largely due to British diplomatic pressure (and the strategically important position of the Azores). During the 1950s and the 1960s, the countries stood together at the margins of European integration, founding the European Free Trade Association with several other nations. The UK finally entered the European Economic Community in 1973, and was followed by Portugal in 1986. Yet, in recent times, although the countries’ geopolitical perspectives have not profoundly changed, their positions in the world and in European affairs have evolved differently.

Portugal is a member of the eurozone and the Schengen Area, while the UK is not. Portugal sees its participation in the EU as central to its democracy, while the UK – having opted to leave the bloc – does not. Portugal closely associates its economic modernisation and prosperity with the single market, while the UK no longer does. Since becoming an EU member, Portugal has never fundamentally questioned the European integration process. Indeed, it supports deeper integration in some areas.

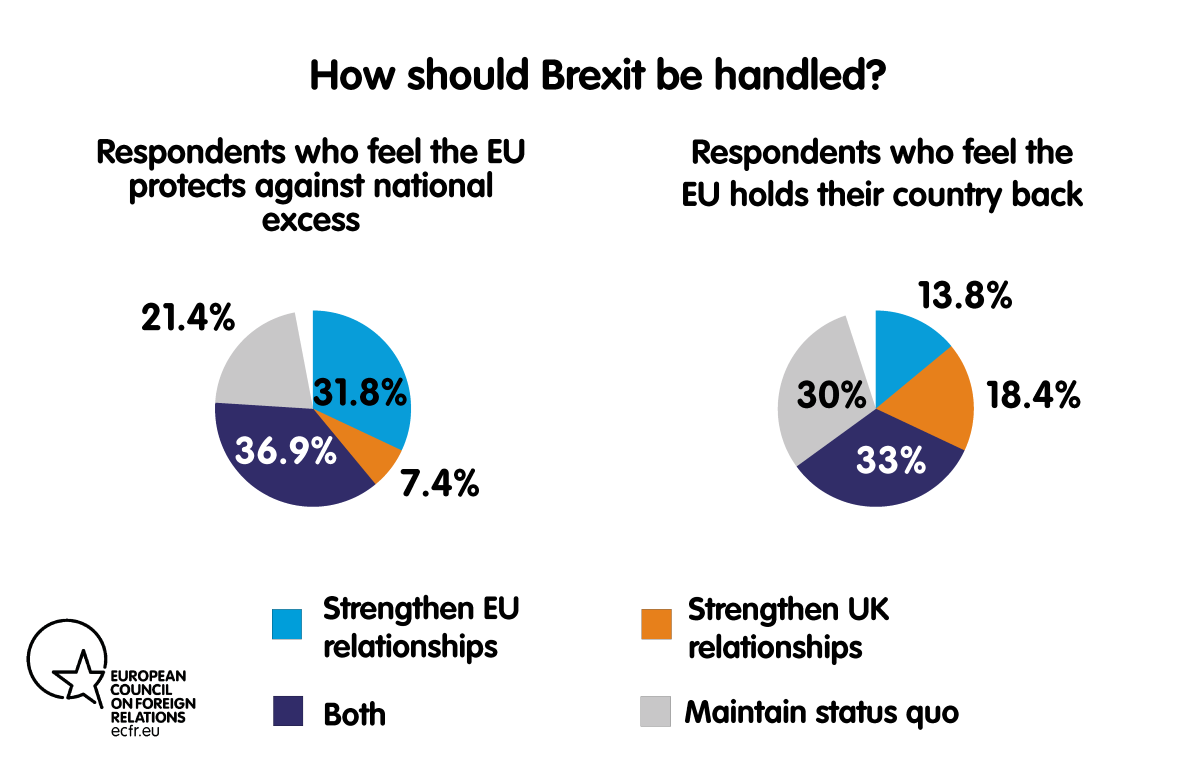

Portugal has extensive economic ties to the UK, where there is a large Portuguese diaspora. This helps explains why 30 percent of Portuguese respondents to ECFR’s survey believed that their country should respond to Brexit by strengthening its relationship with both the UK and the EU. Yet another 25 percent of them felt it should strengthen its ties with the EU alone, and just 7 percent with the UK alone. Seventy-four percent of those who emphasised that Portugal should strengthen its relationship with the EU and the UK saw the bloc as providing protection from the failures of national governments. This indicates that Brexit may have acted as a vaccination against Euroscepticism – which might help explain why the anti-EU tone has been much lower in Portugal’s current electoral campaign.

ECFR’s survey also revealed a shift in the Portuguese position on the United States. Since the end of the second world war, Lisbon has been a strategic ally of Washington – both bilaterally (as symbolised by the US Air Force detachment at Lajes Field) and through NATO. Following the democratisation of Portugal, the relationship grew closer and expanded to other areas. Portugal was a firm supporter of the US during the cold war, the Iraq crisis, the so-called war on terror, and the (now abandoned) negotiations over the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. But something appears to have changed in the way the Portuguese perceive US politics: 70 percent of respondents wanted their country to remain neutral in a conflict between the US and China, while just 14 percent preferred it to back the US.

To be sure, Portugal continues to be a committed member of the transatlantic alliance – as Portuguese leaders never tire of confirming. But the country now seems to place greater emphasis than ever on autonomy from the US. For example, it overcame its initial suspicion of Permanent Structured Cooperation to commit to the project. This is not to say that Portugal questions the importance of its strategic relationship with the US, but rather that it is wary of the White House’s current approach to foreign policy. The Portuguese authorities – particularly the government and the president – have been openly critical of unilateralism and protectionism. Portugal’s basic stance is that, in an increasingly globalised world, it needs to be open to other countries and to cooperate with them. For Lisbon, it is not an option to go it alone, either at the European level or on the world stage.

This philosophy may lie behind Portugal’s receptiveness to Chinese diplomacy and investment. In 2011, experiencing a deep economic and social crisis, Portugal quickly moved to strengthen its ties with China in several areas (under a government comprising the Social Democratic Party and the People’s Party). Since then, Portugal and China have developed new links in trade, tourism, agriculture, education, and technology. China even acquired a controlling stake in Portugal’s national power grid, largest electricity company, and biggest insurer, as well as Portuguese banks, healthcare firms, communications companies, and ports. In 2015 Portugal became one of the founding members of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank; in 2019 it became the first eurozone country to sell renminbi-denominated “Panda” bonds. In the past four years, the government has tried to establish Portugal as the main gateway for Chinese investment in Europe.

There is little doubt that such investment helped drive Portugal’s economic recovery. Yet ECFR’s survey data show that Portuguese citizens are becoming concerned about the government’s policy on China. They believe that, to become a stronger global player, the EU should make the limitation of Chinese economic leverage over Europe its second-highest priority – after, as discussed above, efforts to strengthen European unity. (In contrast, the containment of Russian influence is only their fifth-highest priority.) Curiously, supporters of the Social Democratic Party – which, when in government, launched this new relationship with China – are more committed to containing China’s influence than any other voter group. They may now be beginning to recognise its dangers.

The Portuguese believe that, in its relationship with Africa, the EU should prioritise healthcare above all else, focusing on economic growth only after corruption and education. This suggests that they may believe Portuguese commercial investments in the continent have not been worthwhile.

Commitment to multilateralism

As it heads to the polls, Portugal remains an optimistic country, but one with a strong sense of its own fragility. It is fully aware of the extent to which its economic future, its global influence, and its capacity to handle the challenges of an increasingly interconnected world are fundamentally tied to the fate of the EU. It is, therefore, deeply affected by the Euro-pessimism – the belief that the EU may collapse in the next 10-20 years – that is tangible across today’s union. The Portuguese believe that, if the European project fails, their future will become far bleaker. They also feel that their national political system works better in tandem with the EU one.

This acute awareness of the importance of a continent-sized alliance to a relatively small country has seemingly turned the Portuguese away from the message of nationalist parties. Portugal’s historical and national identity may have also played a role in this: the country is fairly homogeneous in its ethno-religious make-up and its geographical borders have long remained stable. Furthermore, Portugal has long been more open to other cultures than most other European countries. And the recent influx of immigrants into Europe has had little impact on the country, because Portugal is neither a popular final destination for them nor an easy access point to the rest of the continent.

Since it became a democracy, Portugal has had no far-right or nationalist party with significant popular support or a large presence in parliament. As mentioned above, the Portuguese are unlikely to elect any members of Chega as MPs. Nonetheless, the party’s formation could reflect a change of mood in the electorate – as could that of two other centre-right parties, Aliança and Iniciativa Liberal. In contrast to events in other parts of southern Europe – where parties such as Syriza, Podemos, the League, and the Five Star Movement experienced exponential growth and profoundly changed their country’s politics – Portugal is not experiencing any radical change in its party system. All national polls, as well as ECFR’s survey, indicate that the Socialist Party and the Social Democratic Party will continue to dominate Portuguese politics. Nonetheless, these new parties will likely fragment the vote on the centre-right. This could help the Socialists win the October 2019 general election comfortably. With help from the seemingly fast-rising PAN, the party could form a parliamentary majority.

Regardless of the election results, the next Portuguese government will continue to prioritise multilateralism. This is Portugal’s first approach to tackling important issues in European and world affairs, ranging from climate change to corruption, to economic competition with other global powers. Multilateralism shapes Portuguese attitudes towards Brexit, the future of the transatlantic relationship, and even its sometimes contradictory relationship with China (which, as discussed, combines openness with wariness). As Portugal primarily views EU politics through the lens of international cooperation, other member states can rely on it to be an active partner in strengthening European strategic autonomy in the coming years – which will likely be a key priority for the incoming high representative for foreign and security policy. Portugal will almost certainly help the union pursue this goal when it assumes the presidency of the Council of the EU in the first half of 2021.

Above all, Portuguese voters want the new leaders of the EU’s institutions to prioritise European unity and cohesion in the coming years. As ECFR’s survey shows, this comes across in their attitudes towards foreign policy issues such as Portuguese ties with the EU after Brexit and the risks of the EU’s potential collapse. The Portuguese may have faced significant challenges within the EU – as the financial crisis and subsequent bailout showed – but they seem to believe that this is the price of achieving a bigger goal. They will applaud the European Commission led by Ursula Von der Leyen if it succeeds in holding the EU together and enhancing the bloc’s geopolitical power.

About the authors

Susi Dennison is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations and director of ECFR’s European Power programme. In this role, she explores issues relating to strategy, cohesion, and politics to achieve a collective EU foreign and security policy. She led ECFR’s European Foreign Policy Scorecard project for five years; since the beginning of this year, she has overseen research for ECFR’s Unlock project.

Lívia Franco is a professor and senior researcher at the Institute for Political Studies at the Catholic University of Portugal (IEP-UCP). Her areas of interest include contemporary international politics, security and defence issues, and democracy studies. Franco earned her PhD in political science at IEP-UCP and her MA in international relations from Leuven University. She was a PhD student at Boston College and a visiting scholar at Brown University, as well as the recipient of FCT, FLAD, and Fulbright Scholarships. Franco frequently provides commentary on international affairs in the Portuguese media. She has been ECFR’s associate researcher on Portugal since 2010.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to Philipp Dreyer for his analysis of survey data for this paper, to the YouGov team for their support in developing and carrying out the survey, and to Katharina Botel-Azzinnaro for her brilliant work on the graphics. Chris Raggett’s editorial work improved the writing greatly, but any errors remain the authors’ own.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.