How to govern a fragmented EU: What Europeans said at the ballot box

Summary

- The results of the European Parliament election confront EU leaders with a considerable challenge: navigating a new, more fragmented, and polarised political environment.

- This was a ‘split screen’ election: electors rarely used their vote to endorse the status quo, but they requested different things. Some want to take on climate change and nationalism; others want to regain national sovereignty and tackle Islamic radicalism.

- This need not mean a ‘split screen’ Europe: the desire for change is real across the board, and the new EU institutions will need to provide answers for voters on these issues.

- To meet this challenge, the larger political families should prepare to work with parties beyond the mainstream, some of which became stronger on the domestic political scene thanks to the election results. They must do this while preserving red lines on European values.

- The high turnout in the election gives the EU a mandate to prove it can respond to voters’ concerns. But this mandate is not open-ended – volatility in the electorate could benefit anti-system parties much more the next time Europe goes to the polls.

Introduction

As prime ministers and presidents head to Brussels for European Council meetings in the post-2019 European Parliament election era, they will find that they have to navigate a new, more political Europe. Pro-Europeans have claimed victory in the May vote: turnout leaped to 51 percent, and two-thirds of voters supported pro-European parties, which topped the polls in 23 out of 28 member states. But many voters also supported anti-European or Eurosceptic parties, whether of the left or right. These parties secured almost one-third of seats in the new European Parliament. The European Union that is emerging is, therefore, more fragmented and more polarised than ever before.

The two main political groups have lost their majority for the first time in the history of the Parliament; they have also lost their majority in the European Council. Appointments to the new European Commission will reflect this new political make-up. In many ways, this was a split screen election: some voters showed up to vote because they feared a possible collapse of the EU, or because they wanted to send a message to political leaders to find solutions to climate change and rising nationalism. But other voters wanted to regain national sovereignty and deal with Islamic radicalism and migration.

This split screen election need not mean a split screen Europe, however. The election showed that Europe’s biggest feature is its volatility, rather than settled tribal divisions. In this new Europe, we can expect a permanent campaign: parties and Parliamentary groups will now have to assemble shifting majorities if big decisions are to pass.

To understand what politics will look like in the coming years, the European Council on Foreign Relations, in collaboration with YouGov, carried out a ‘day after’ survey in the six largest EU member states. In addition, researchers in ECFR’s network across all 28 member states have analysed the manifestos and campaign promises of all the political parties that won seats in this election. This report studies five ‘maps’ which should guide the formation of these new, shifting majorities; the next generation of EU institution leaders should also study these maps carefully to help them identify where best to focus their energy and attention.

Firstly, the post-political family map. One of the paradoxes of the present moment is that voters are becoming less committed to particular parties at the same time as party groupings in Brussels are themselves become ever more tribal and extreme in their support of candidates for the leadership of the EU institutions. Tolerance among voters of different potential coalitions is relatively high, setting aside scenarios in which their preferred parties were to attempt ally with the extreme left or the far right – where more of them would withdraw their support.

Secondly, the new political geography. The shape of all of Europe’s political groups has changed in terms of regional make-up. This will have important implications for European parties’ ability to develop coalitions in a more political way.

Thirdly, the new policy map. Whereas migration, austerity, and Russia were the key files that divided Europe over the past ten years, the new political geography of Europe means one should expect climate change and the rule of law to become key battlegrounds over the next five years. To avoid geography becoming the determining factor on these files, political groups should look more closely at the policy mandate that voters have given them on these issues.

Fourthly, the new generational map. The divide by age group is radically different in each of the big member states – and within the big party groupings.

Fifthly, the new emotional map. Voters were motivated by stress and fear, but optimism too. They have given Europe a chance to prove that it can speak to their concerns about the world. But this offer may be time-limited, putting pressure on political actors to start work on reaching across the divide now.

The post-political family map

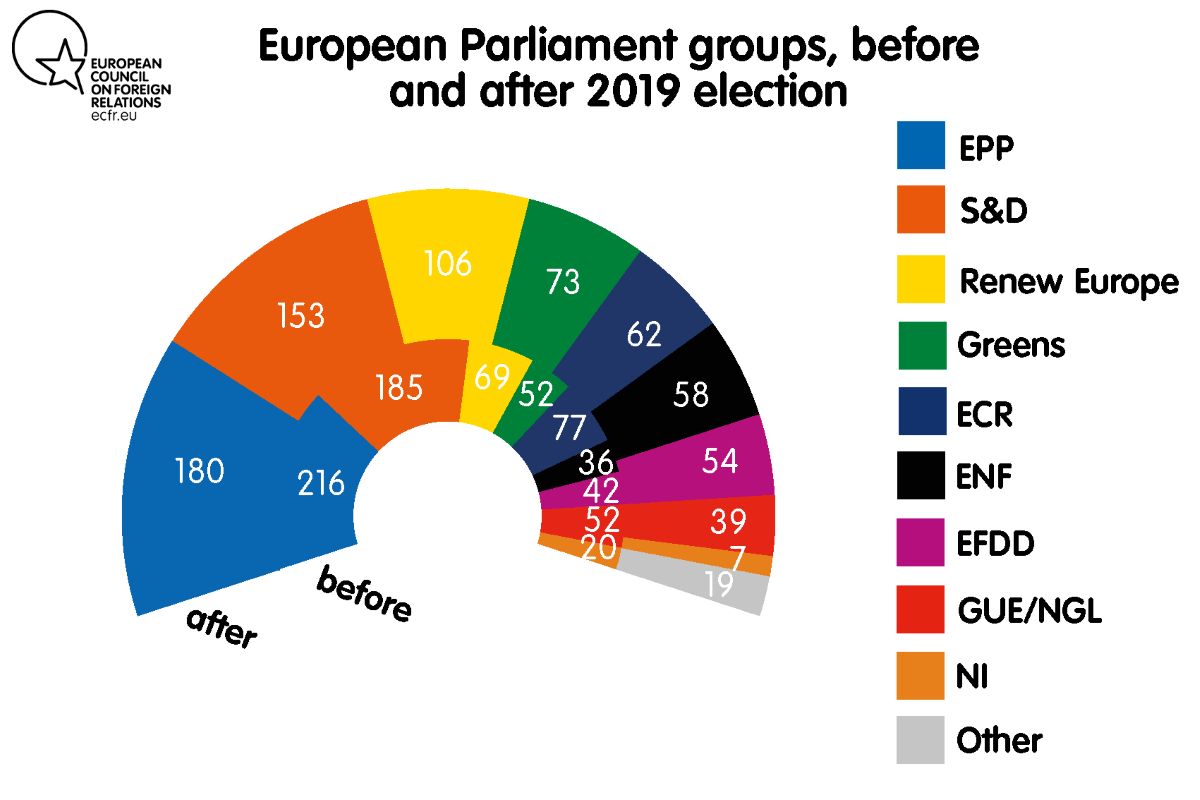

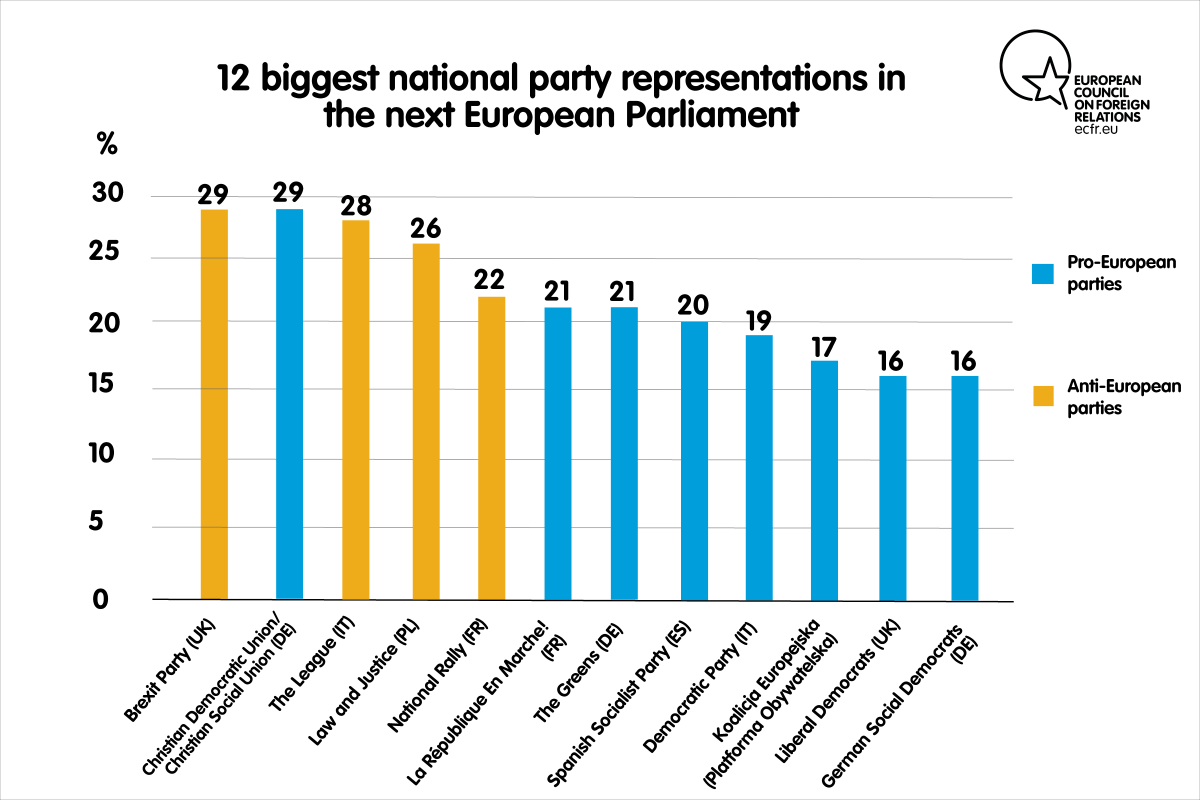

The European electorate is fragmented and volatile. Consequently, so is the new European Parliament. The 751 seats of the European Parliament will be held by over 180 different national parties. For the first time in the Parliament’s history, the Grand Coalition of Christian Democrats and Social Democrats no longer has a majority. Some of these parties’ voices will be louder than others: just 12 national parties will send more than 15 MEPs to Brussels.

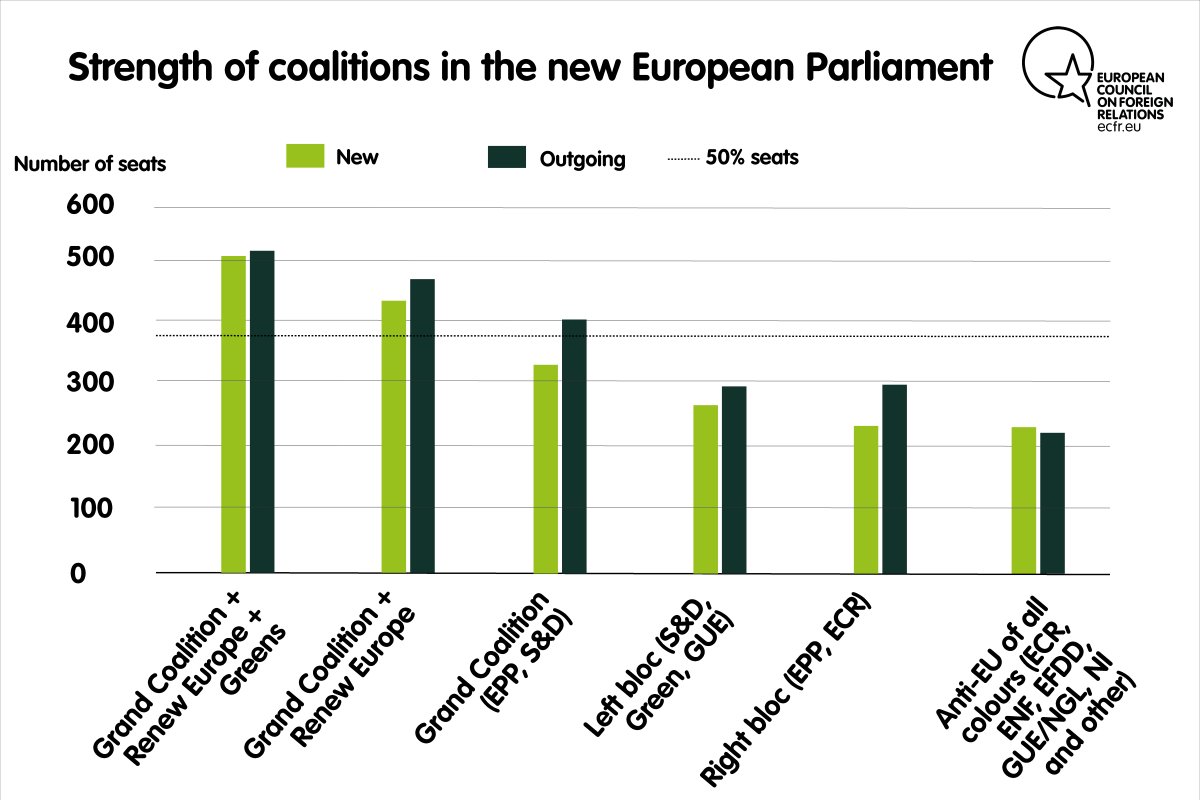

To fulfil their campaign promises, parties will have to build coalitions. In the new European Parliament, a minimum of 376 seats is needed for a majority. So, even if liberal bloc Renew Europe were to join its 106 seats with either the left or right bloc, this would not be enough (the left or right bloc each being larger than the Socialists and Democrats, or the S&D; or the European People’s Party, or EPP). Predictions are doing the rounds in Brussels and Strasbourg of a possible extra-Grand Coalition of the EPP, the S&D, and Renew Europe – or even a super-sized coalition of these three groups plus the Greens. If it requires a certain leap of imagination to envisage agreement among such a broad group working together at the outset of the European Parliament, it seems even more unlikely to expect that such an unwieldy alliance would hold together on a lasting basis.

Given both the strong desire among the electorate for change and the fragmented nature of the new Parliament, political parties will increasingly have to form short-term alliances around issues, swapping partners when the need for consensus demands it. In the interests of delivering results, they should be ready to look for this consensus beyond the constraints of political groups, and should seek out support beyond the depleted mainstream when there is a convergence of views on a topic.

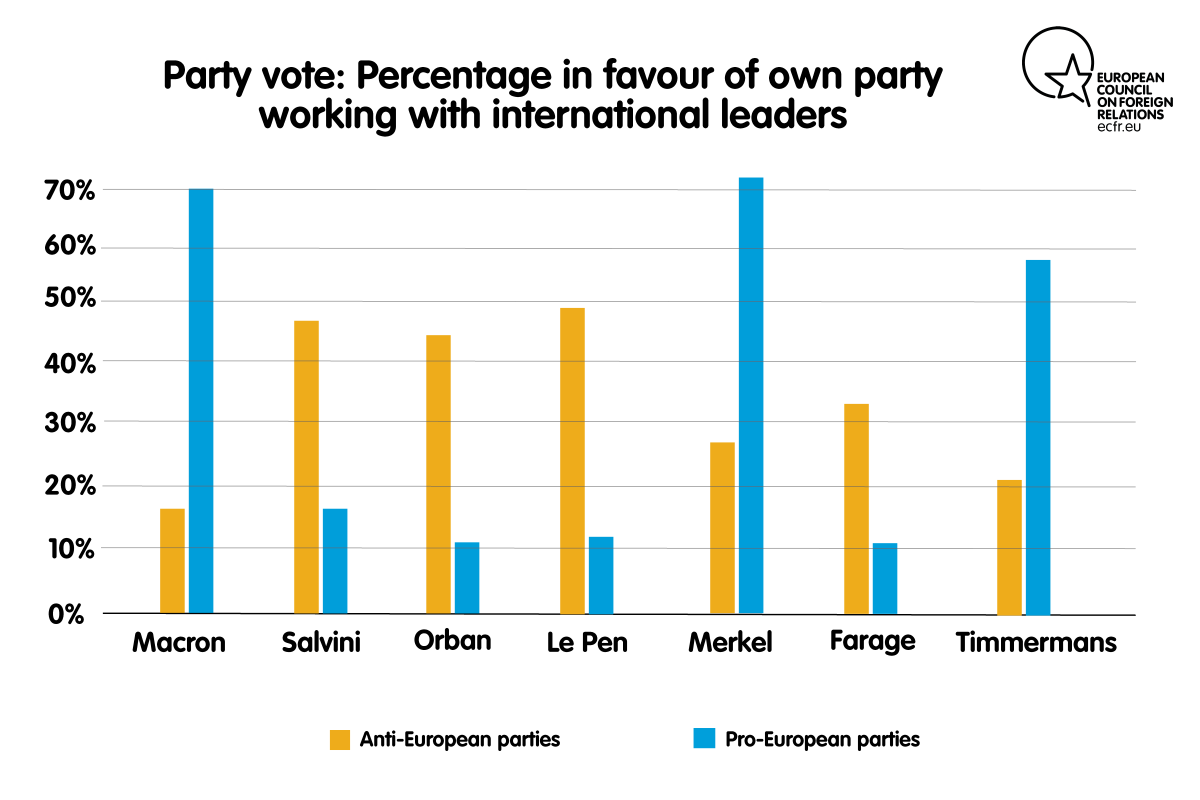

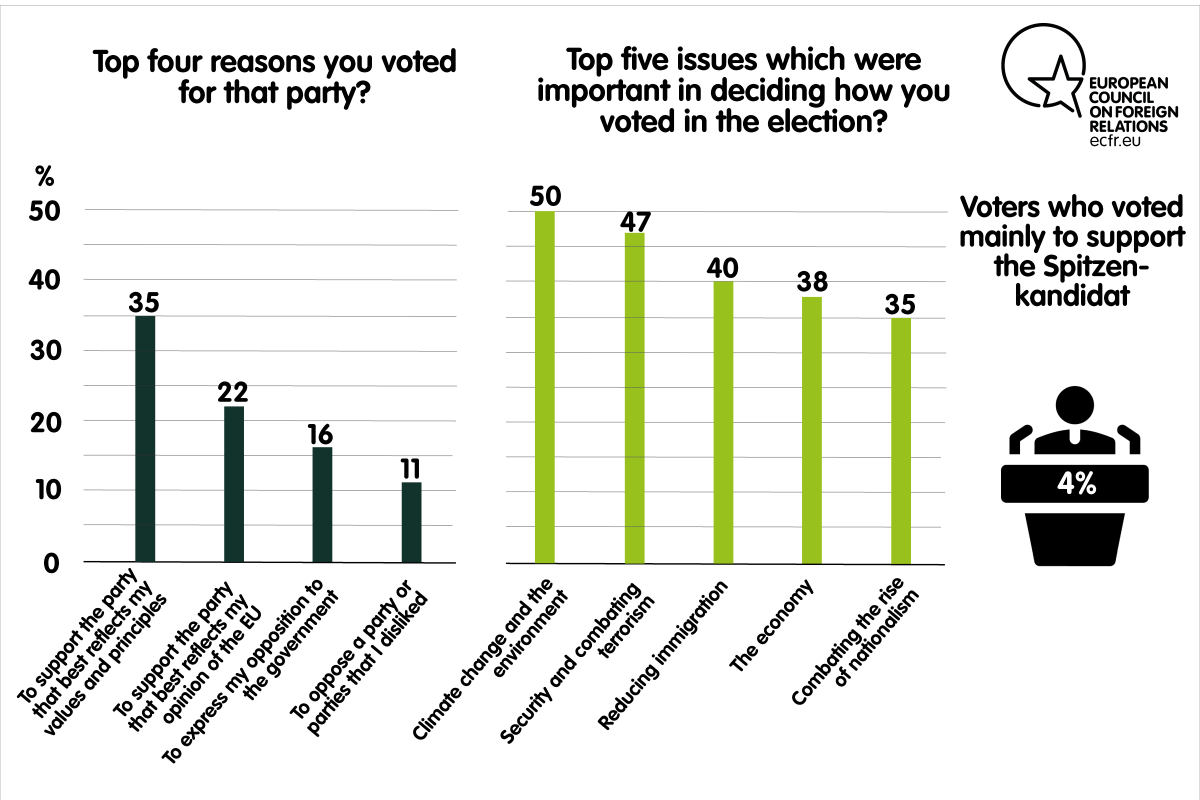

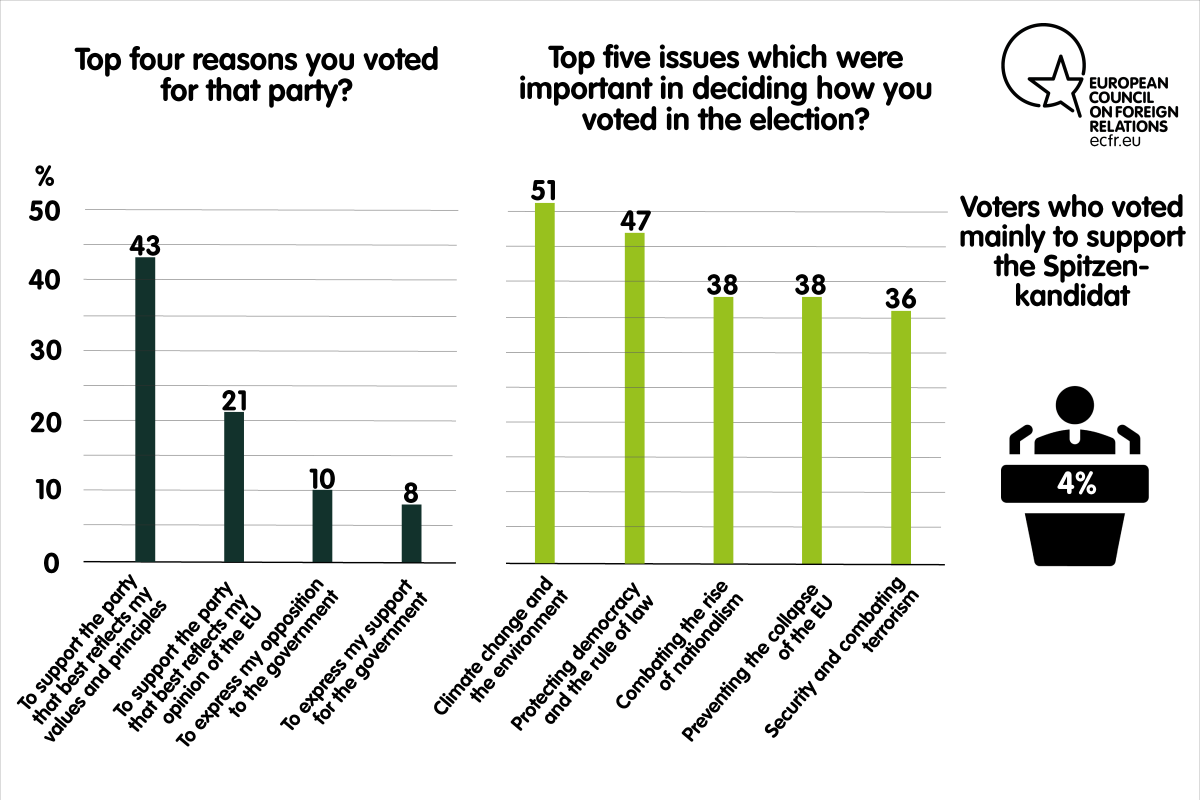

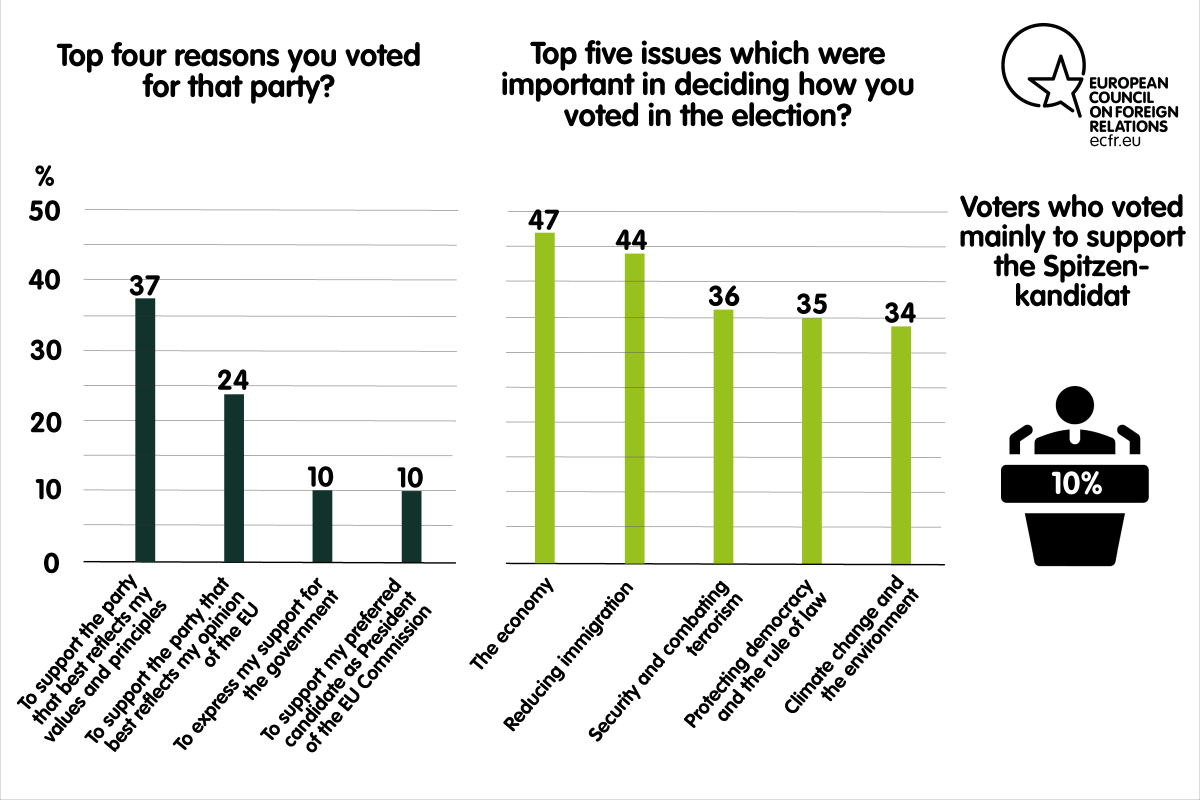

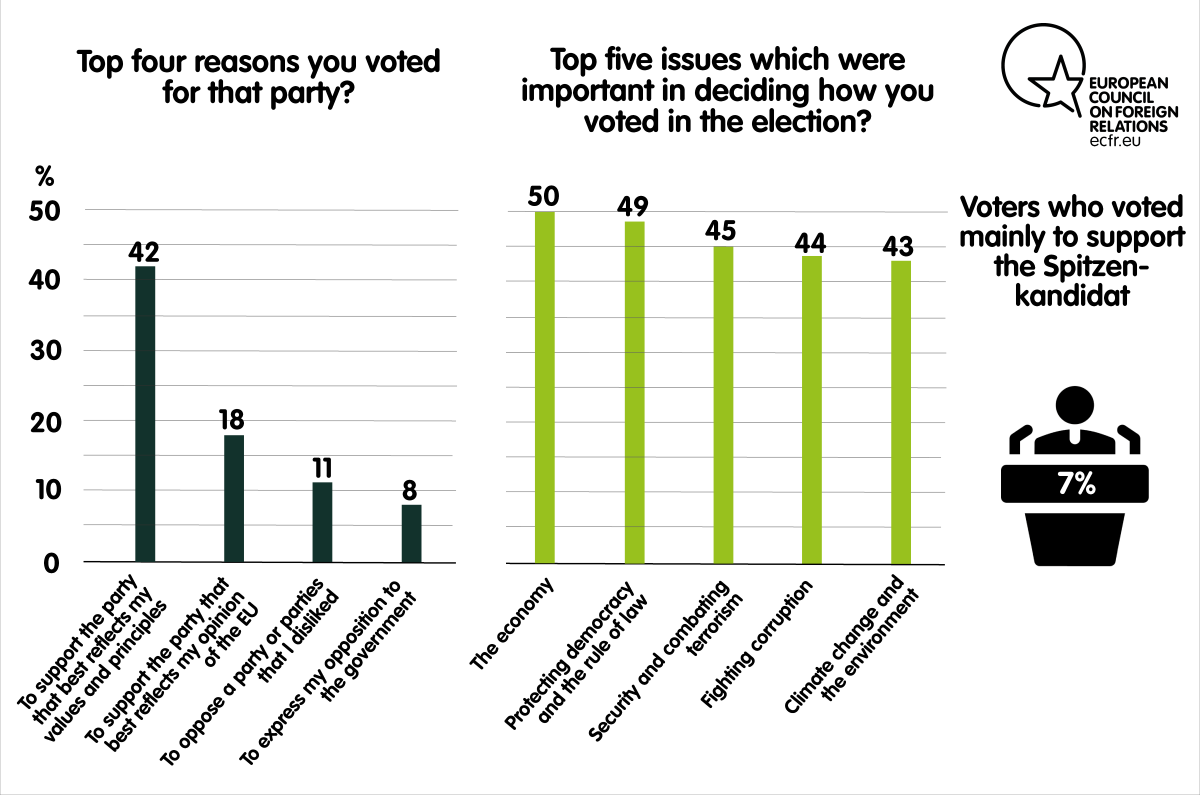

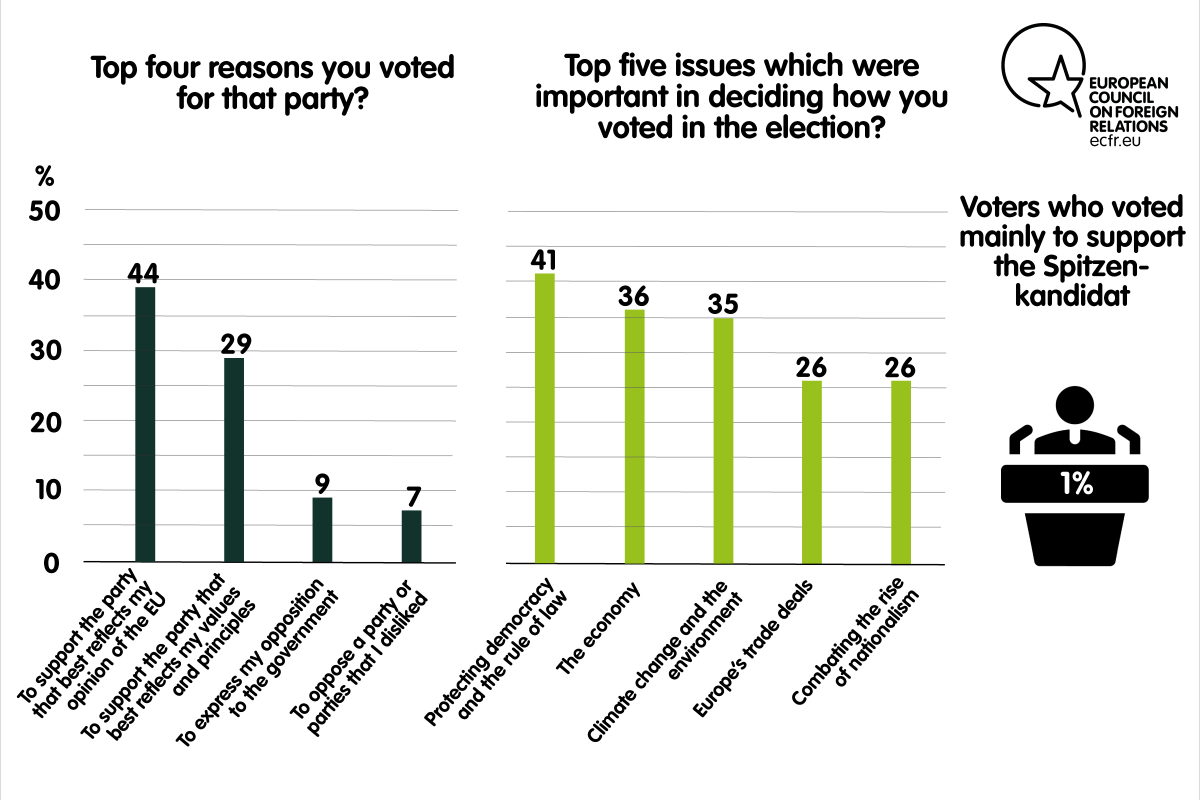

To what extent do ECFR’s survey results suggest that voters would tolerate more flexible coalitions? While the main political parties are still operating by party family logic, battling it out over the Spitzenkandidat process, only 4 percent of voters in Germany and France said they were voting mainly for the Spitzenkandidaten. In terms of the leaders that voters find acceptable within coalitions their parties join, it is unsurprising that pro-Europeans favour pro-European leaders and vice versa. But, interestingly, among anti-European voters, Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage – with his overtly EU-destructive agenda – is only slightly more palatable than Angela Merkel. On the other hand, at 27 percent versus 16 percent, Merkel is significantly more popular among anti-Europeans than Emmanuel Macron, perhaps because her agenda on the future of Europe has been less overt. All in all, more than 207 million Europeans (52 percent of the electorate) would be in favour of their party working with Merkel – while 190 million (48 percent of all voters) would feel comfortable working with Macron. No more than one-quarter of the European electorate would be in favour of their party working with Italian deputy prime minister Matteo Salvini, Rassemblement National leader Marine Le Pen, or Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orban.

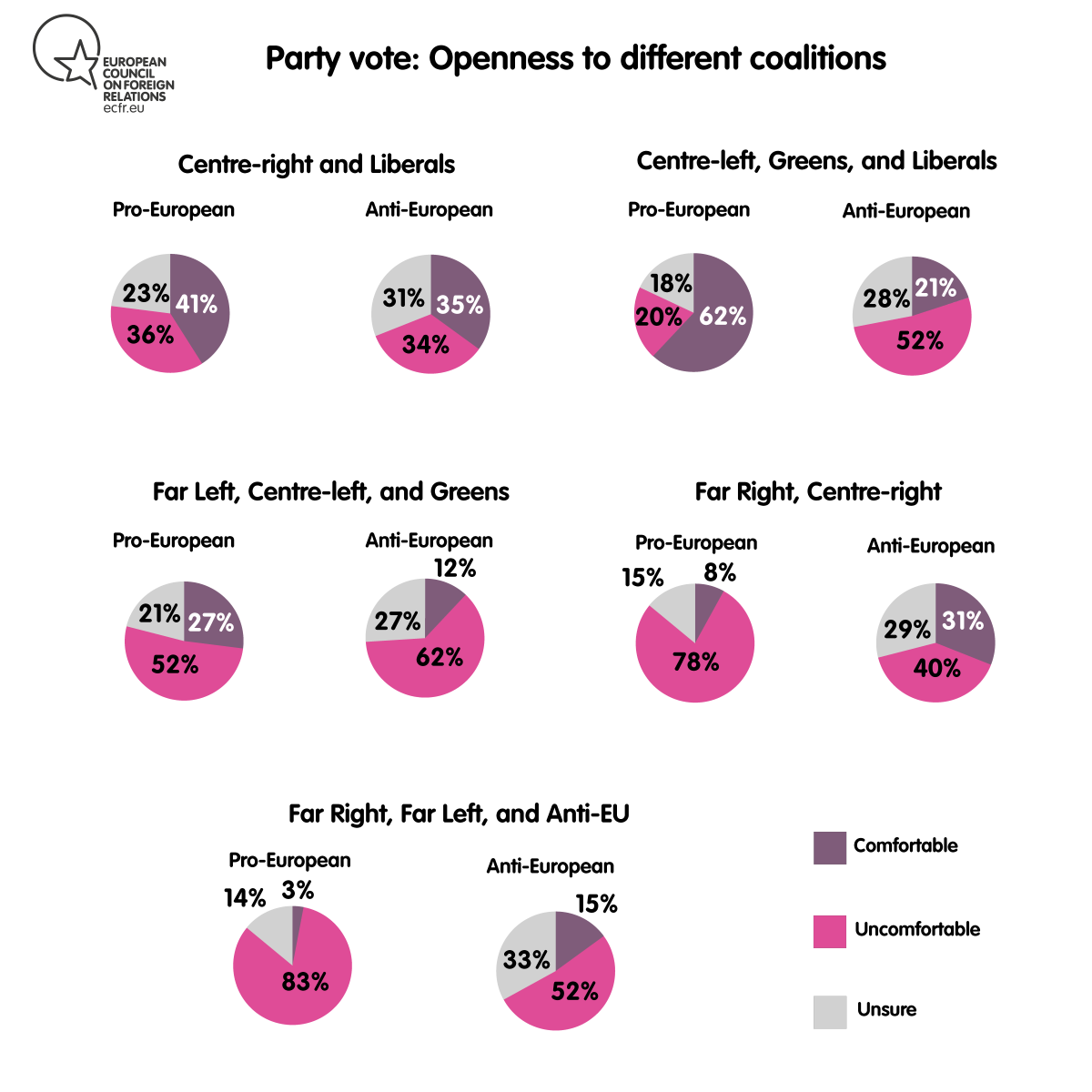

In terms of the parties that European voters say they are open to, a majority of pro-Europeans (62 percent) would support an alliance between the Liberals, the S&D, and the Greens; but 52 percent would be uncomfortable with involving the far left instead of the Liberals in this alliance. Younger voters are more tolerant of the latter idea. Forty percent of pro-Europeans would be uncomfortable with a centre-right–far-right alliance but, on the other hand, only 41 percent would be at ease with the idea of a Liberal–centre-right alliance. On balance, pro-Europeans feel comfortable with coalitions dominated either by the centre-right or the centre-left. But they feel less comfortable with working beyond the mainstream, exhibiting very little support for either side aligning with the radical left or right.

Anti-European voters are most open to a centre-right–liberal coalition (35 percent), followed by a far-right–centre-right coalition (31 percent). Only 15 percent would feel comfortable with a formal far-right and far-left anti-European coalition. This low figure suggests that other issues, rather than anti-Europeanism per se, are more significant drivers for these types of voters.

Overall, the most popular coalition among Europeans would be one comprising the centre-left, the Greens, and the Liberals: this is favoured by more than 180 million voters (46 percent of the entire electorate). A total of 148 million Europeans (37 percent of all voters) would feel comfortable if their party joined a coalition with the centre-right and the Liberals. This is the second most popular option.

But the picture gets more complicated when looking at preferences expressed by supporters of individual national parties. Interestingly, supporters of far-right parties are more ideologically committed to party identity than other voters are. Forty-two per cent of Brexit Party supporters do not want to see their party sit with Le Pen. Meanwhile, 46 percent of Law and Justice (PiS) supporters would feel uncomfortable with their party joining a coalition with far-right or far-left anti-EU parties. Supporters of the Brexit Party are only open to coalitions with the far right or the far left. It appears that what matters for these voters is not left-right divisions but rather whether the coalition is anti-EU. In turn, most of those who voted for the League, Alternative for Germany, Rassemblement National, and PiS would feel uncomfortable about their party joining a far-right–far-left alliance. They are also unclear about where they would like to seek allies: with the far right and the centre-right (a preferred option of PiS and Le Pen supporters) or with the centre-right and liberals (a preferred option of League, Alternative für Deutschland, and Vox supporters). Five Star Movement voters are so divided that there is no possible coalition that more than one-third of them would be happy to see their party joining.

Overall, this picture suggests that the jury is out among voters as to what partnerships would be acceptable, and within what limits. Views on leaders, with a preference for Merkel over Macron, may indicate that they have a higher tolerance for coalitions built around a ‘delivery Europe’ than around ‘more Europe’. This puts pressure on political parties to work out who their partners should be on the mandate their voters have asked them to deliver.

The new political geography

Some important shifts took place during the 2019 election, with the centre of gravity of all the major parties moving. This has created a potentially rocky early period of learning to work together, even within political families. Initial efforts have shown the extent to which tensions between politics and geography may well be difficult to manage – such as the failed attempt by the French government to encourage the 79 French MEPs to meet and think as a French unit, which resulted in only La République En Marche! members turning up to the arranged meeting.

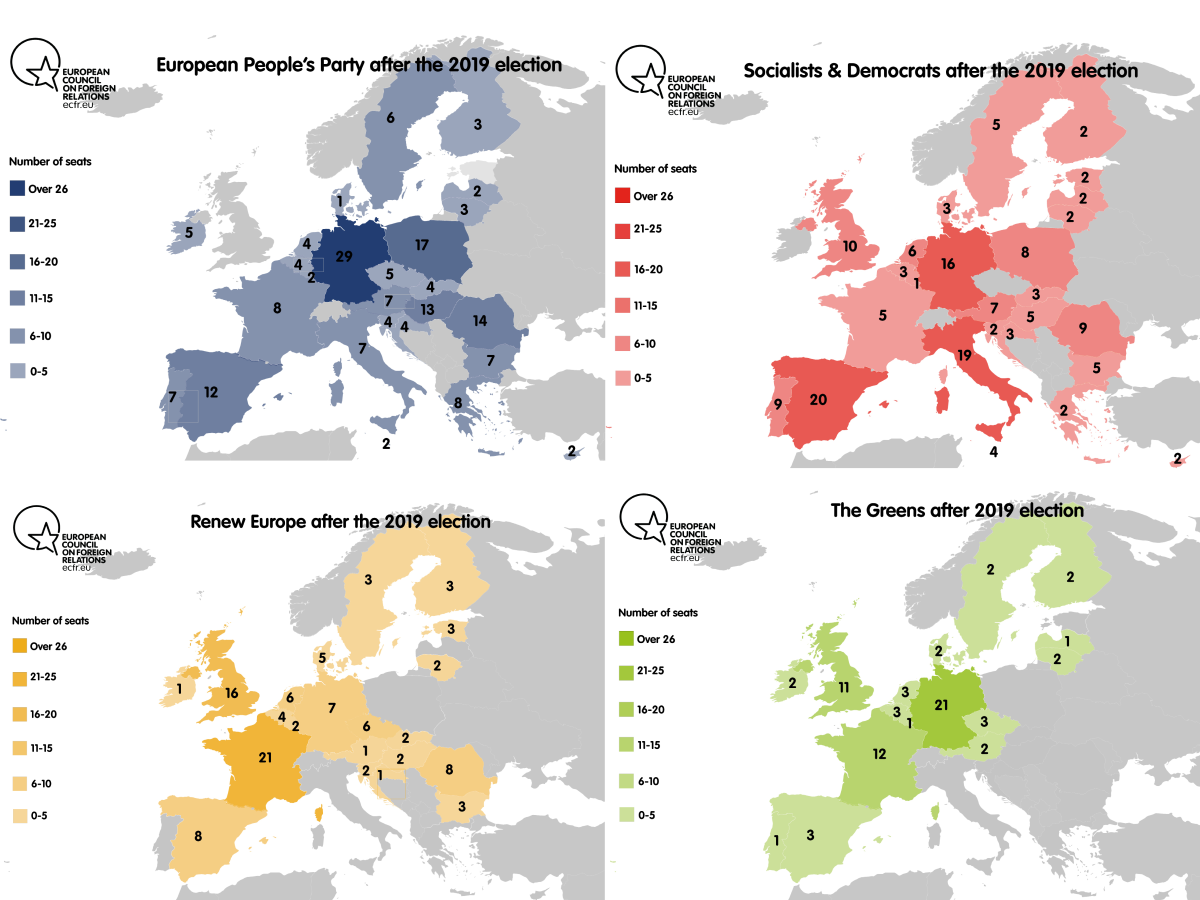

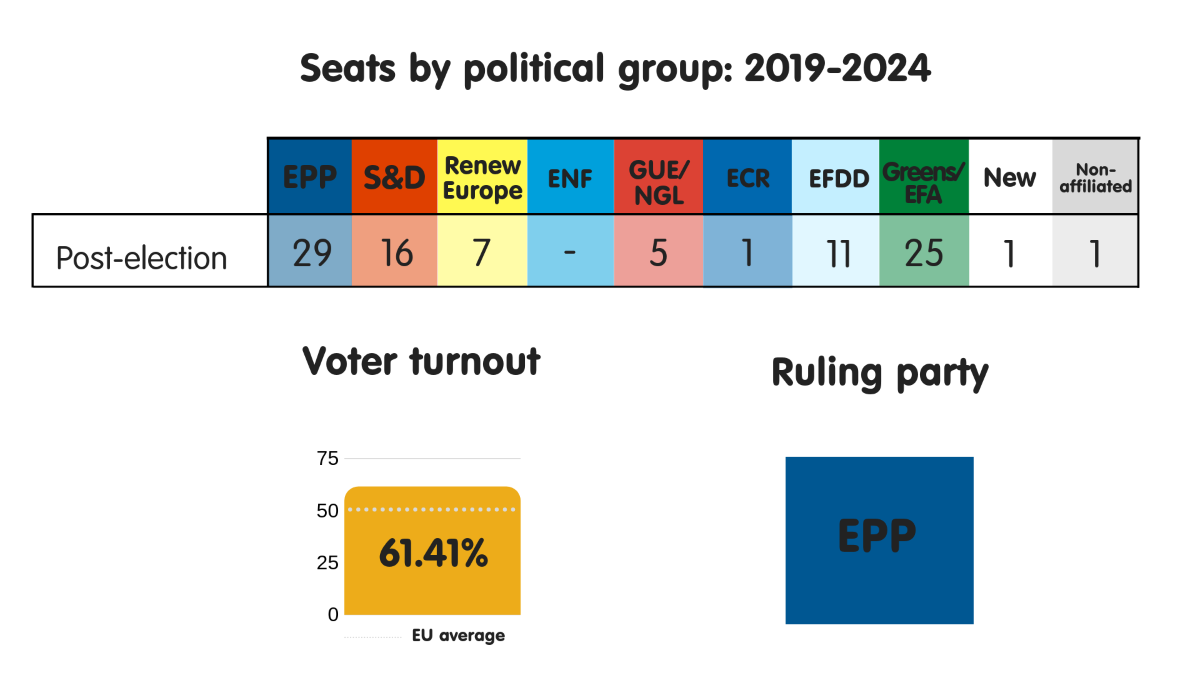

The EPP power base has moved slightly towards central and eastern Europe. While its tally of seats has fallen overall, from 218 to 176, these losses were concentrated in France and Italy, followed by Poland, Spain, Slovakia, and Germany. However, the EPP gained seats in Romania, Hungary, Greece, Sweden, Austria, Ireland, and Lithuania. It is highly possible that Orban’s Fidesz will leave the EPP in the coming weeks, depending on how other coalition discussions develop.

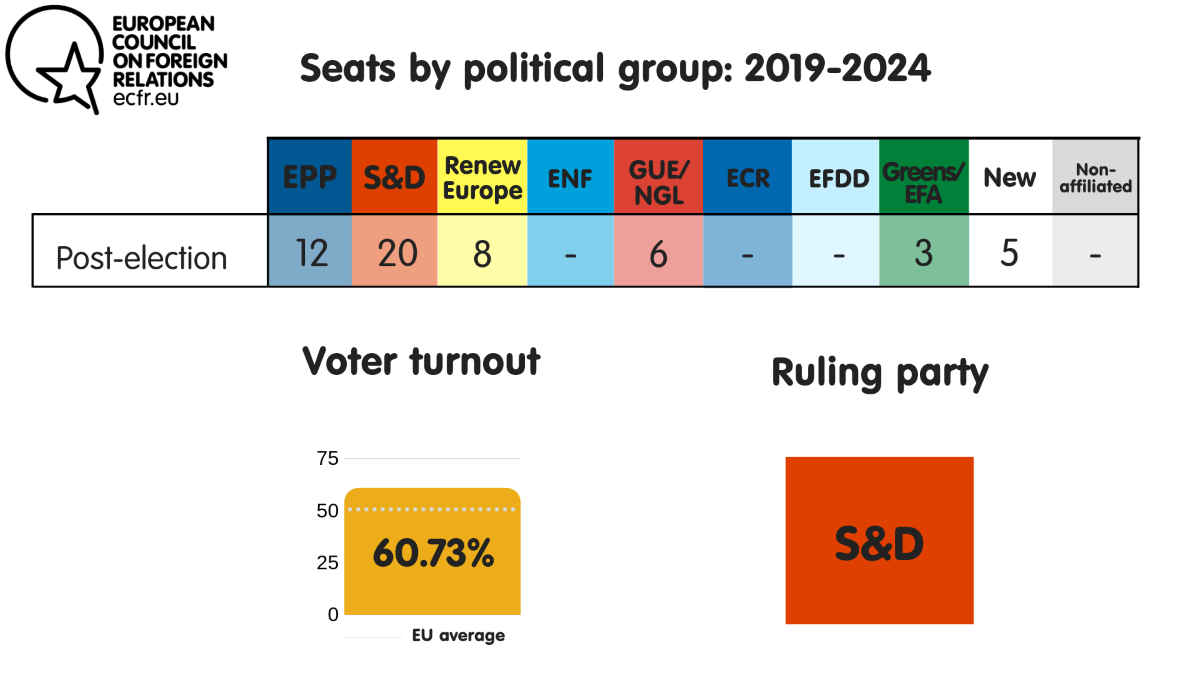

The S&D has shifted southward, with gains in Spain, Portugal, Bulgaria, and Malta, as well as in Poland, the Netherlands, Hungary, Latvia, Slovenia, and Estonia. Overall, the S&D now has a seat count of 153, down from 185 before the election. This is mostly as a result of losses in Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom, followed by France and Romania.

Renew Europe, the Liberal group, will, as the recent battle over changing its name indicates, be under French dominance – even more so after Brexit. The group made particularly big gains in France and the UK, and more limited gains in Germany, Denmark, and Luxembourg. But the Liberals also improved their position in Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, Croatia, Slovenia, and the Czech Republic. This will ensure that they continue to have a strong anchor in central and eastern Europe.

The much-discussed Green wave in this election saw the Greens increase their tally of MEPs from 52 to more than 70. They were particularly successful in Germany, France, and the UK. In addition, they also made more moderate gains in the Netherlands, Belgium, Portugal, Denmark, Finland, and Ireland. Some commentators have warned against overstating the importance of this success, partly in light of the specific geographical focus of this development in north-western Europe. Indeed, support for the Greens in central and eastern European states is more limited. Lithuania, Latvia, and the Czech Republic are the only countries from this region that now send Green MEPs to Brussels.

Finally, parties to the right of the EPP will have MEPs in every central and eastern European country (except for Slovenia) and in Scandinavia. They continue to be rare in southern Europe (except for Italy and Greece).

Geography matters because it will play a role in policy debates. For example, if the EPP has become more central European, it will be harder for this group to take a tough line on the protection of democracy and the rule of law. A more southern-dominated S&D will put up a stronger resistance to austerity. And if the Greens, who lack significant representation from central Europe, form part of a pro-European coalition in the new European Parliament, it may be easy for governments and citizens in central Europe to question the ‘green’ elements in the agenda of such a coalition (not just on climate change and the environment but also on the rule of law or liberal values), declaring such elements to be purely western European.

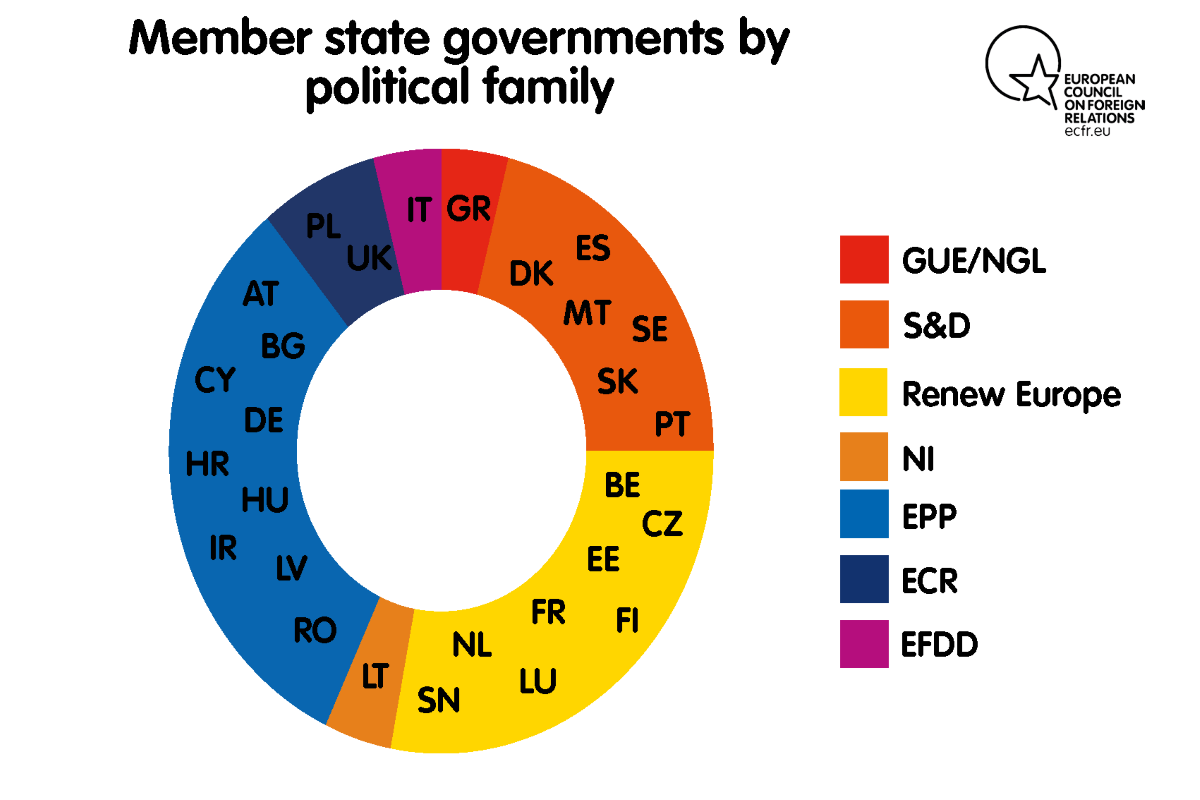

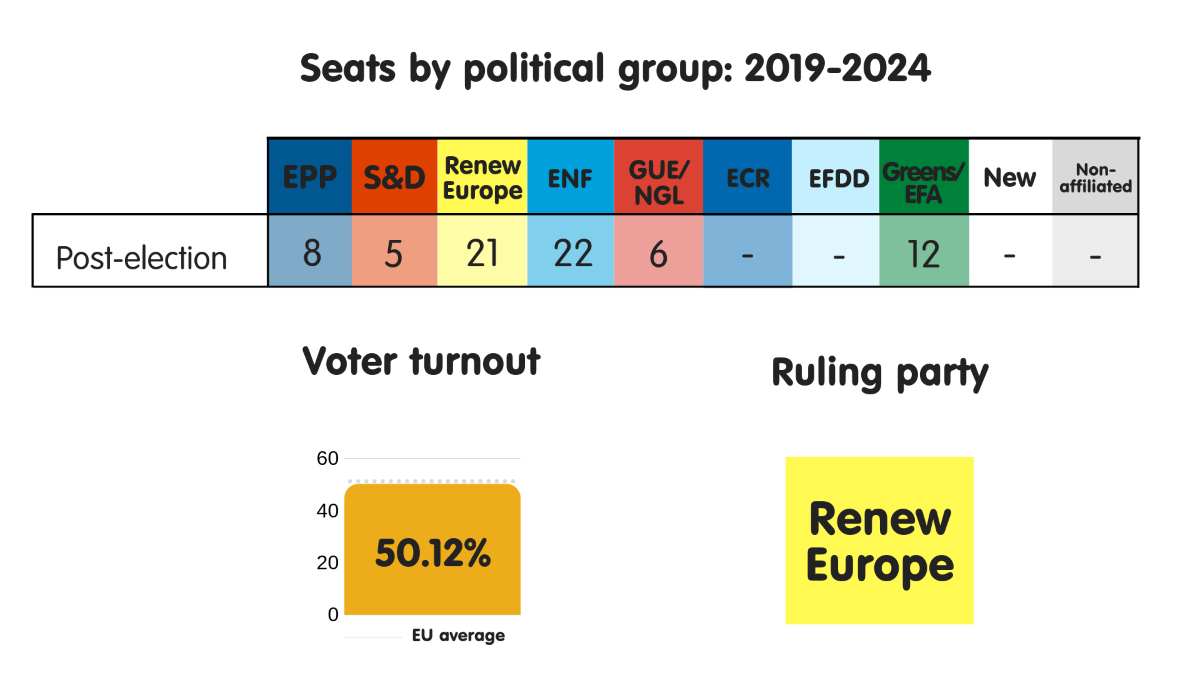

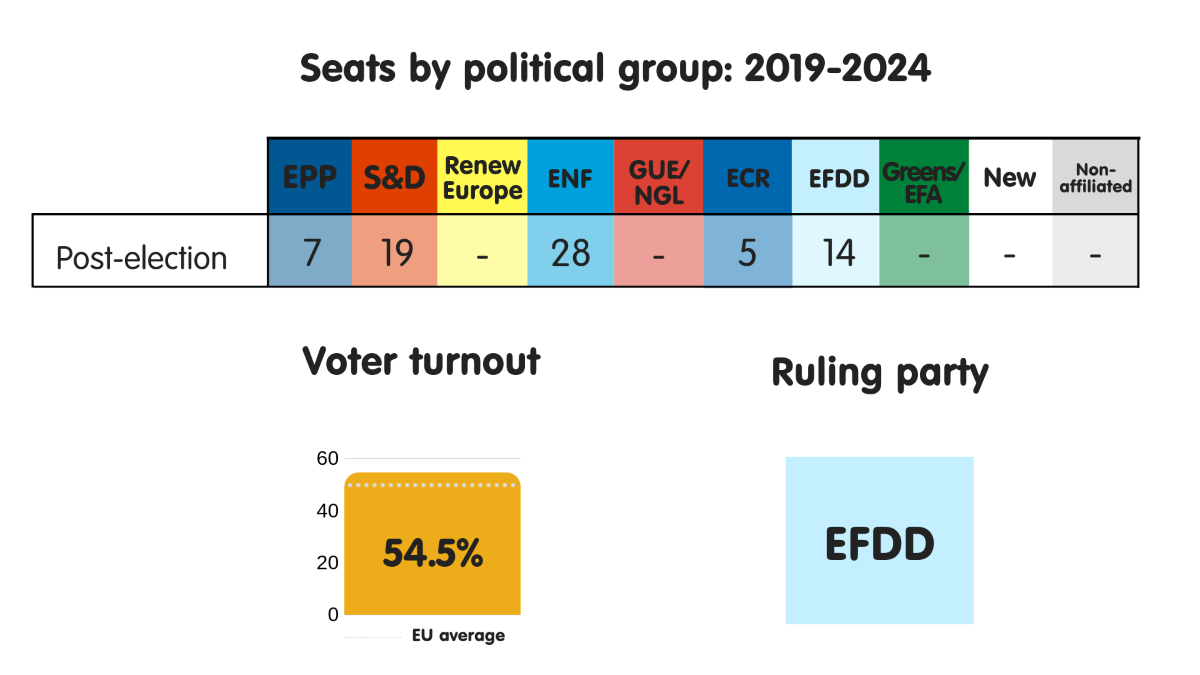

These shifts in political geography also feed through into the Council of the EU, which will have even more power on some of the key files over the coming years. As ECFR’s Coalition Explorer has set out, the Council has both a political dimension and a diplomatic dimension in the way that member states form alliances. The political dimension is directly informed by which political groups national governments belong to. Five years ago, EPP and S&D members led governments in 11 countries each. But the position of the Liberals, and non-mainstream parties, has since improved. After this election, there are now nine governments around the Council table led by parties from the EPP; eight from the Renew Europe group; six from the S&D; two from the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR); one from the Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD); one from European United Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL); and one Independent.

The European Parliament election results, and the debate that preceded the vote, have had an impact on the national political dynamic in many countries. They have strengthened the hand of the opposition where parties outside government have done well (for example, the Labour Party in the Netherlands), destabilised coalitions (as seen with the resignation of Andrea Nahles, the German Social Democrat leader, in response to her party’s dismal showing in polls after the election), and, in some cases, paved the way for new elections (in countries such as Greece and Austria).

Central and eastern European governments are already weakly represented in the main political groups in the European Parliament – and may become even more so if Czech party ANO is expelled from Renew Europe, Fidesz from the EPP, and Romania’s Social Democrats from S&D. Given the already weak political position of central and eastern Europe in the Council, there is a separate risk that the sensitivities of the region will not be properly reflected in the EU’s list of priorities in the next five years. This, in turn, may give ground to even deeper frustrations and resentments in that part of the continent. One way to address this problem would be to involve figures from the region in the selection of the leaders of the EU’s institutions.

The new policy map

In “What Europeans really feel: the battle for the political system”, ECFR argued that this was a split screen election in which groups of voters operated in separate realities – realities determined by their feelings about the political system and their beliefs about how the world works. They accessed different information, which informed their decisions about how to vote.

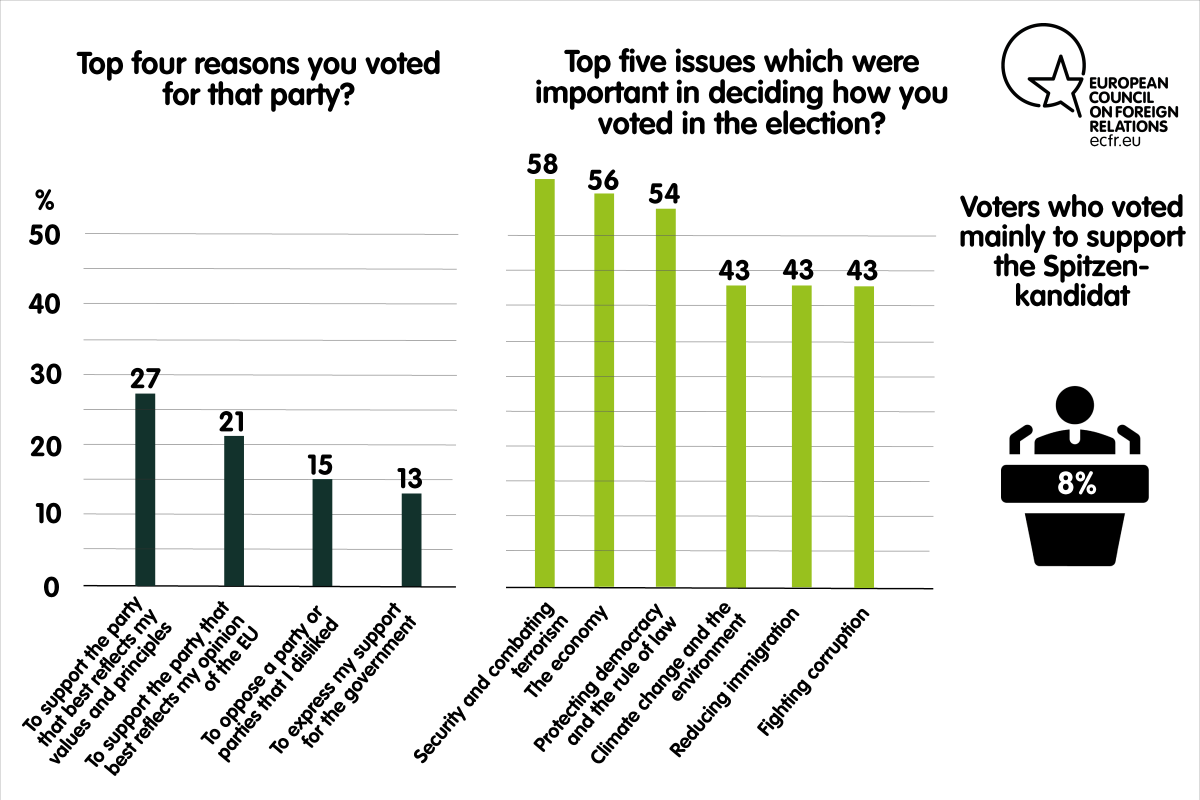

ECFR’s analysis of its ‘day after’ survey in the EU’s six largest member states shows that this reality appears to have driven these voters to support types of parties with different priorities, on the basis of what they felt were the key threats facing Europe. In its pre-election surveys, ECFR identified six major themes that voters were particularly concerned about: climate change; nationalism as a threat to the EU; migration; Islamic radicalism; Russia/international relations; and the economy.

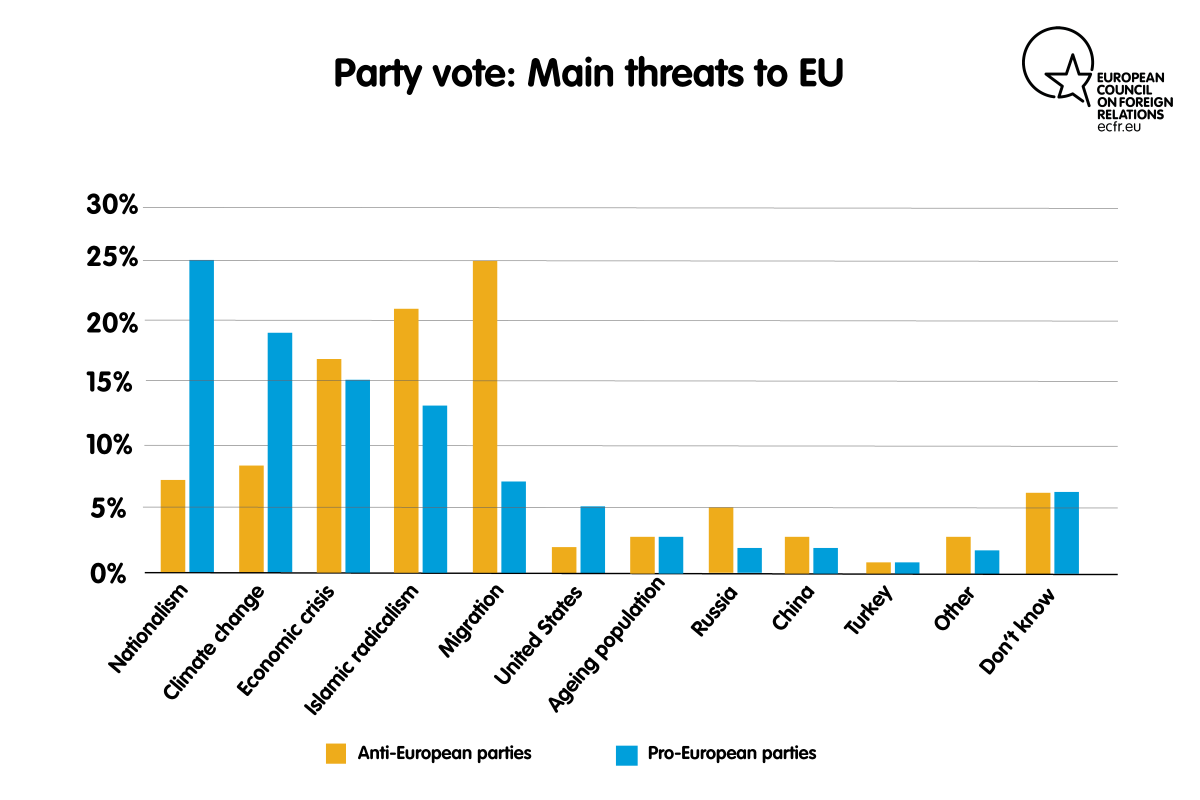

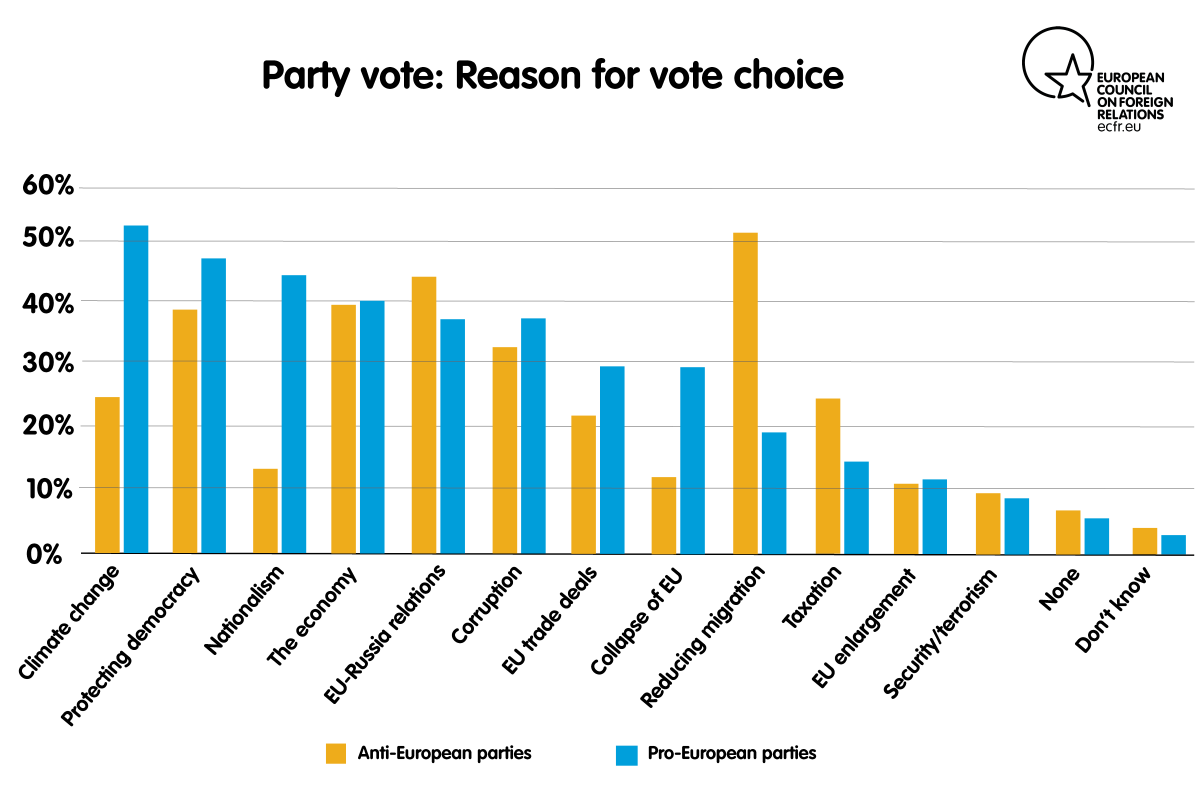

This was confirmed by ECFR’s post-election poll. For more than 170 million voters (43 percent of the European electorate), climate change and the environment were among the most important issues in deciding how they voted in the European Parliament election. An identical share of voters pointed to the protection of democracy and the rule of law as an issue that motivated their decision, while migration was important for 120 million voters (30 percent). But motivations differed between voters who supported pro-European parties and those who backed anti-European ones. The former were mostly influenced by issues of climate change (53 percent), democracy and the rule of law (47 percent), and nationalism (44 percent). Meanwhile, the latter voted for parties that promised to reduce immigration (52 percent) or ensure security and fight terrorism (44 percent).

Pro-European and anti-European voters also differ in their perception of Europe’s main threats. Voters who supported pro-European parties point to the rise of nationalism (25 percent), climate change (19 percent), and the economic crisis (15 percent) as Europe’s single greatest threats. In contrast, those who supported anti-European parties consider migration (25 percent) or Islamic radicalism (21 percent) to be the single most important things to be feared.

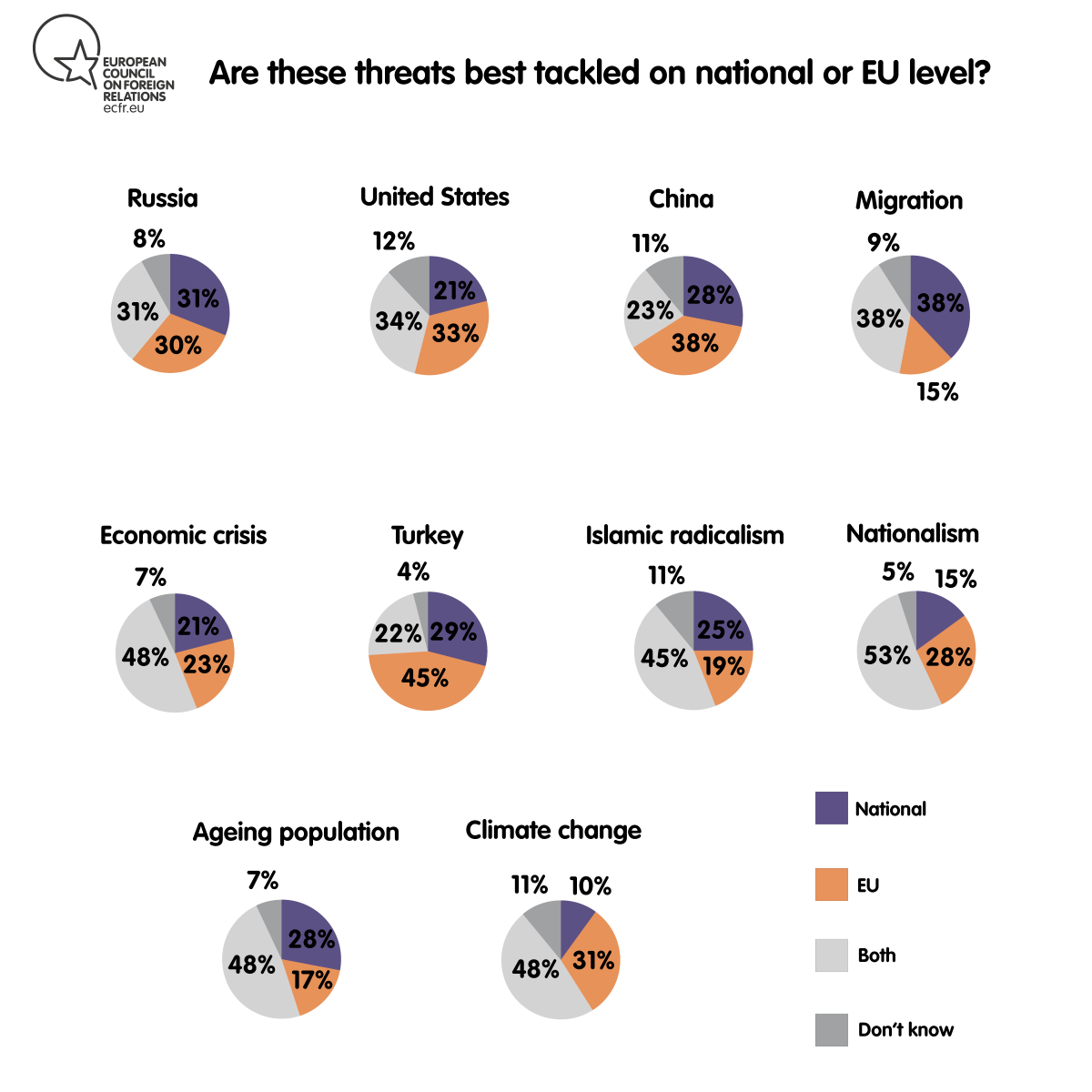

There is a certain weight of expectation on the EU institutions to create a “Europe qui protège”. Forty-five percent of voters think that the threats they care about should be addressed at “both national and European level”. In comparison, 24 percent believe that it is best to tackle these threats at the EU level alone, and 22 percent at the national level alone.

However, this varies significantly by issue. Voters view migration as either a national issue or an issue that is shared with the EU (each scores 38 percent). The least common answer for migration – by far – was for EU cooperation alone to address this matter, at just 15 percent. This probably reflects the fact that migration is seen as a bigger threat among anti-European voters. This is not the case for Islamic radicalism, which is more of a preoccupation among pro-European voters. The largest share of voters (45 percent) believe that Islamic radicalism should be tackled at both the national and EU levels. There is also a strong preference for addressing the following issues at both the national and EU levels: climate change; the ageing population; nationalism; Islamic radicalism; global powers such as the United States, China, and Turkey; and the economic crisis. This suggests that visible EU action in these areas could be important to strengthening the perceived legitimacy and popularity of the EU, even among those who are relatively unconvinced about the EU project.

But the split screen election should not necessarily lead to a split screen Parliament. The campaigns for the European Parliament election showed the extent to which the landscape has become more complicated. With many nationalist parties arguing for a Europe of nation states or a “common sense” Europe rather than for an end to the European project, the jury seems to be out as to what role the EU can play in ushering in the future that voters want to see. There may be scope to build a case for the EU simply through delivering on the threats that voters prioritise.

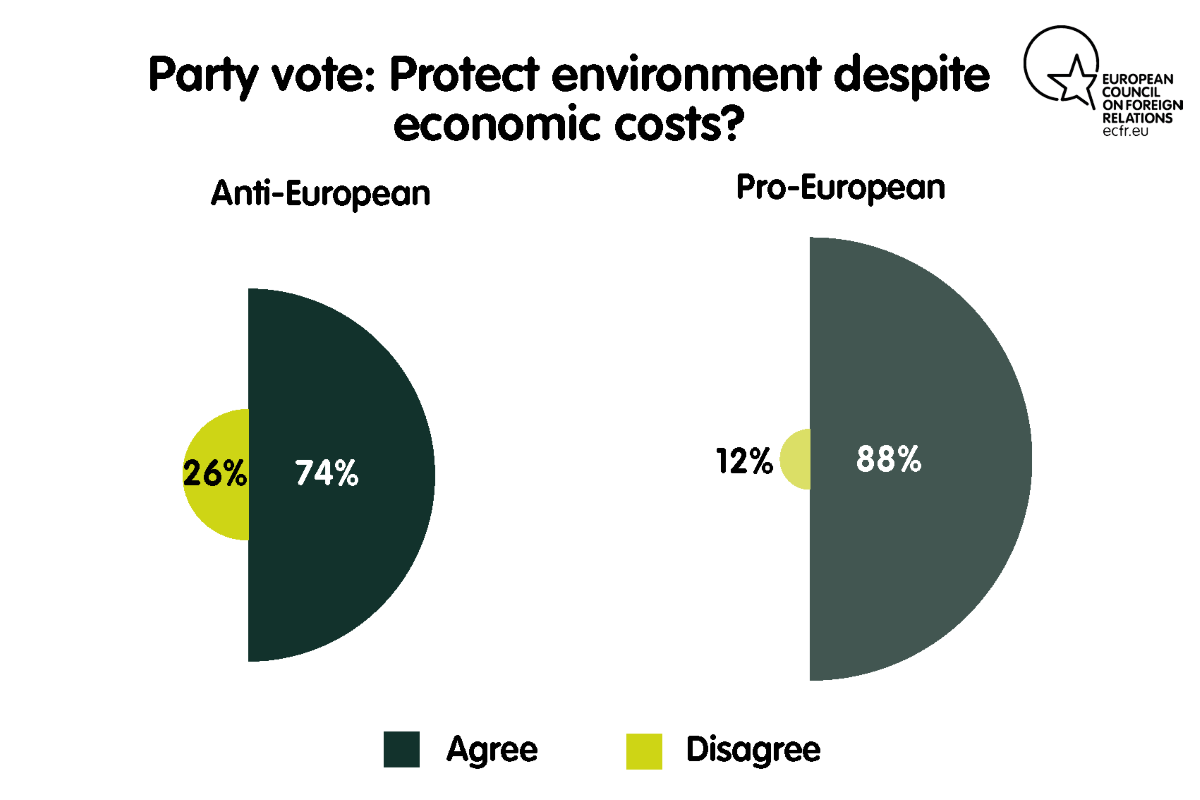

One approach is to work on the issues that matter for voters across the political spectrum. ECFR’s survey suggests that climate change is an issue of great importance to all types of voters – not just those who supported Green parties. ECFR asked specifically whether more should be done on climate change despite the economic cost of this. Here, in all age categories and for both pro-and anti-Europeans, there were very strong majorities in favour of doing more.

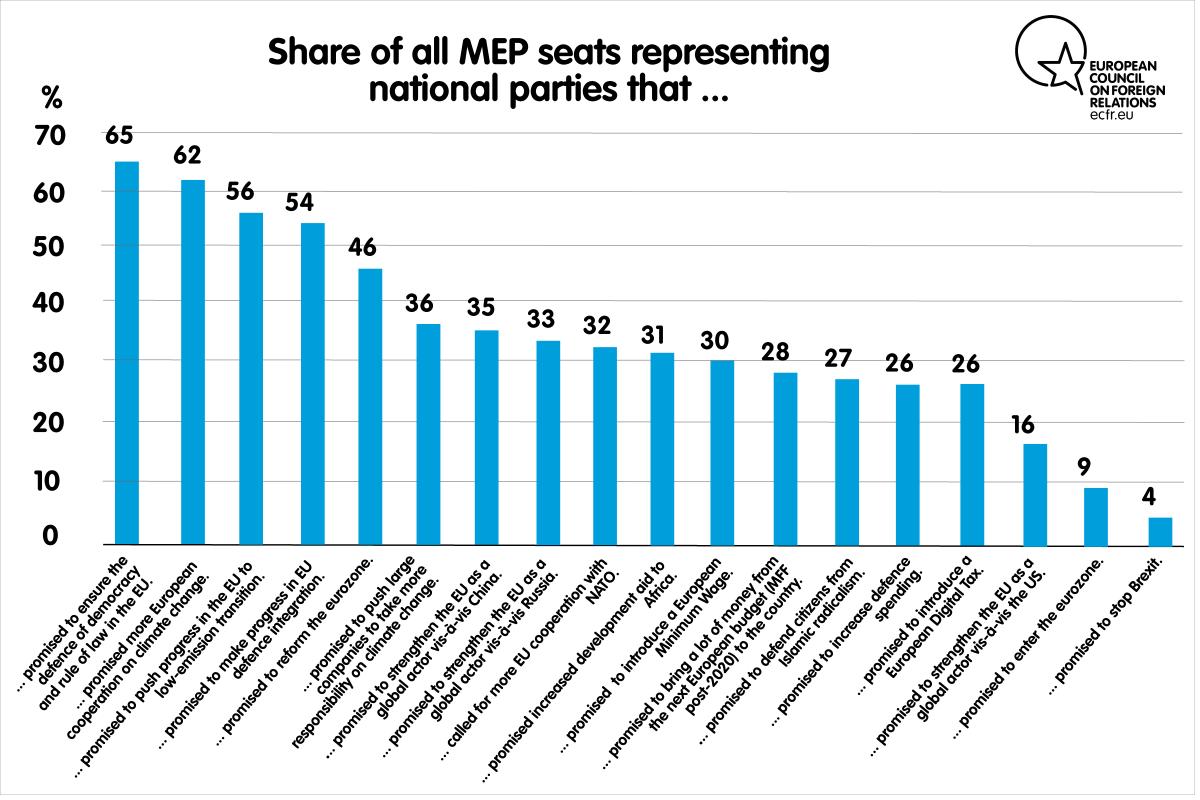

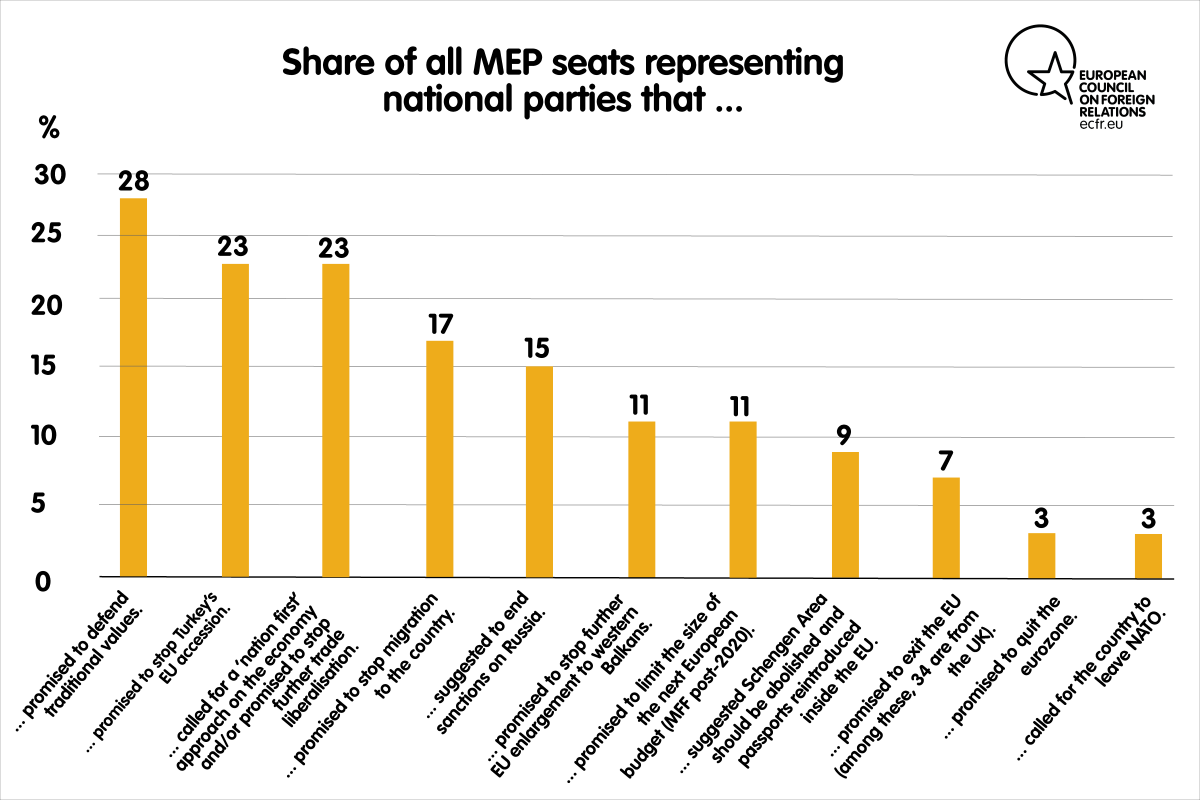

ECFR’s analysis of the campaign promises of the parties represented in the new European Parliament underlines this picture, showing that there are now a majority of MEPs who support EU-level action on three of the six main issues on voters’ minds:

- the defence of democracy in the EU;

- closer cooperation on climate change and progress on the low emission transition; and

- further progress on EU defence integration.

A strong minority also support strengthening the EU’s global role vis-à-vis other powers and greater cooperation with NATO, as well as increases in defence spending.

However, there is also the potential for division between the political families on these questions. For example, further defence integration was an explicit campaign promise for three-quarters of parties belonging to the EPP, the S&D, and Renew Europe. But it has very little support among the Greens, and none at all among other groups.

In terms of campaign promises, support for more EU cooperation on climate change is particularly concentrated among the Greens, the Liberals, the S&D, and the far left. The EPP is split in half on this question, while there is almost no support for such cooperation among parties further to the right.

The question of protecting democracy within the EU is a point of division even within political families. Again, based on ECFR’s analysis of campaign manifestos, support for protecting democracy is particularly strong among the Greens and the Liberals; and three-quarters of EPP and S&D MEPs come from parties that have campaigned in support of this issue. But the issue of whether the currently suspended Fidesz remains part of the EPP could renew tensions around this question: several EPP parties see this as an area of EU overreach. The question also causes division among anti-Europeans: both the League and the Five Star Movement made campaign promises on this. But other anti-European parties, such as PiS, are likely to be highly uncomfortable with this agenda.

There is also significant support for protection against Islamic radicalism, and for a range of EU-level actions associated with the economy including:

- reform of the eurozone;

- a push to ensure large companies pay their fair share of tax (26 percent of new MEPs represent parties that advocated in favour of introducing a European digital tax); and

- the introduction of a European minimum wage.

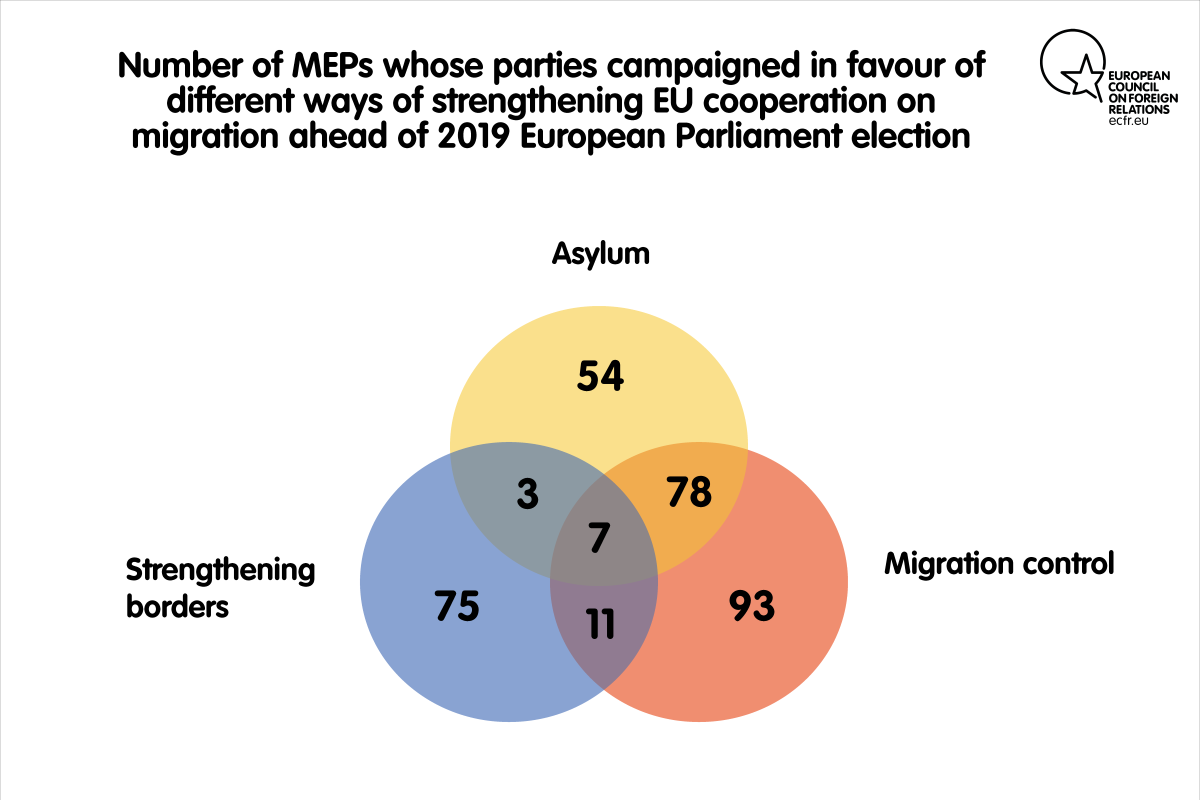

It is hard to see a common way forward on migration, as it remains a significant source of division. Forty-three percent of MEPs belong to parties that campaigned for more EU cooperation on migration, whereas only 11 percent represent parties that called for a devolution of EU powers on migration: the Brexit Party, Alternative for Germany, Forum for Democracy, and Vox. But, among those who are in favour of more cooperation, opinions on preferred policy options vary. Twenty-five percent would back more cooperation on controlling migration (this is particularly the case for S&D parties); 19 percent would favour more European cooperation on asylum (especially the Greens, the Liberals, and S&D parties); and 13 percent would support action to strengthen the EU’s external borders (this is particularly strong among ECR parties). Overall, just 17percent of MEPs represent parties that campaigned on a promise to stop migration altogether.

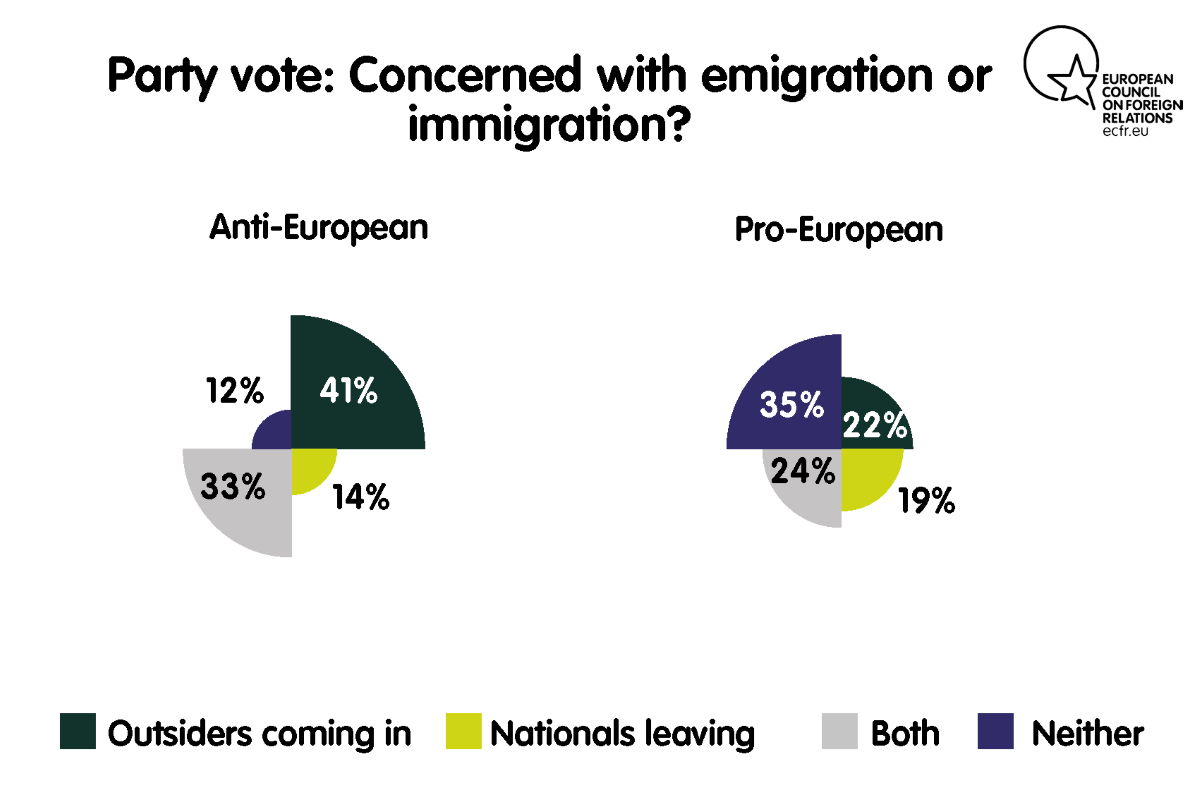

To some extent, these differences mirror the major variations between voters, highlighted in ECFR’s pre-election research, on how they think about migration as a threat – whether their concern is about overall numbers, immigration or emigration, integration, or the impact on public services and housing.

The challenge for the new European Parliament – as well as for the EU’s new leadership in general – will now be to find the right balance between these issues. To foster cooperation, they may need to find ways to agree to trade-offs between the issues that voters care about most and those that cause division.

The new generational map

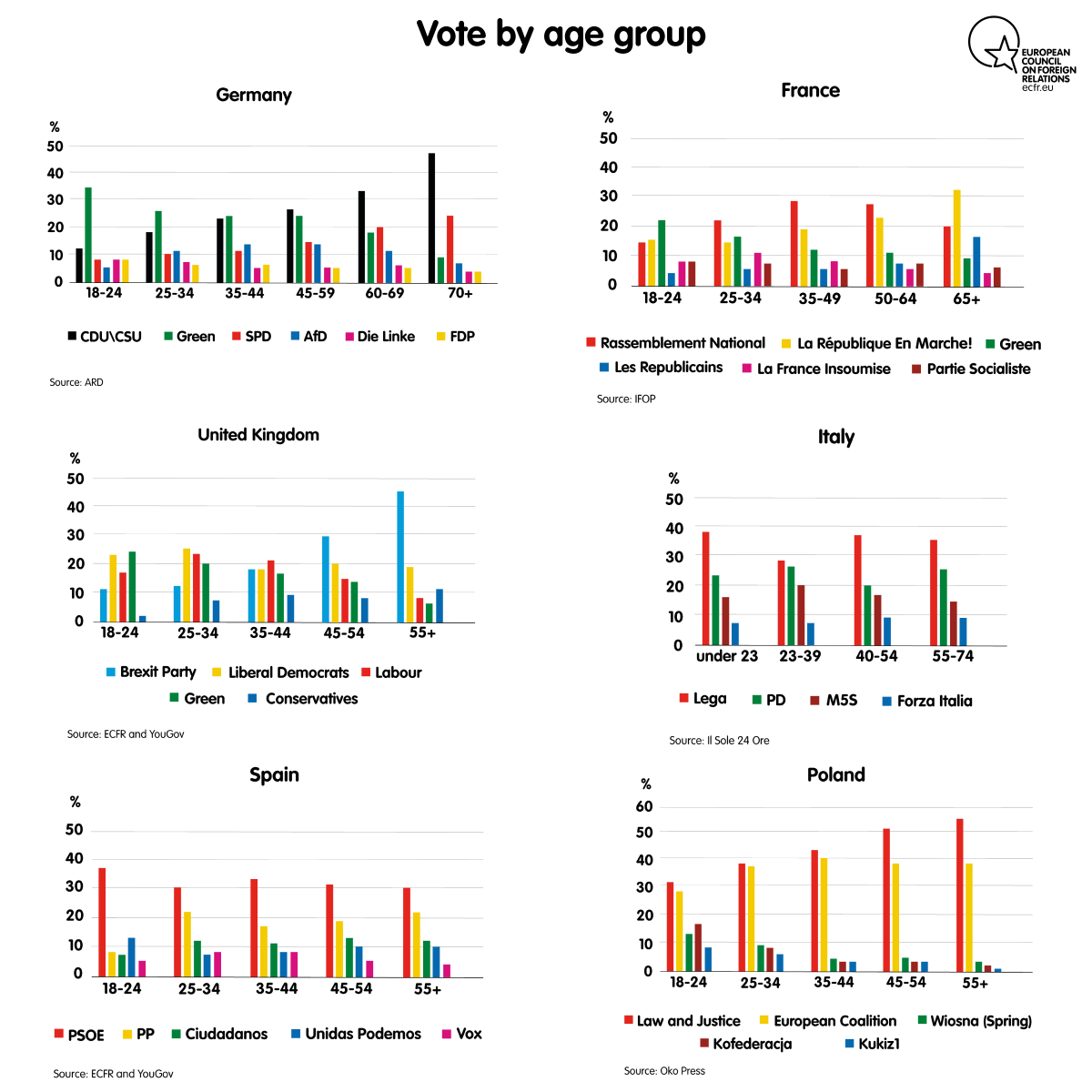

One of the unwritten rules of European political campaigns has been that you should never bet on young voters. But this election showed that young voters should not be ignored either. Across Europe, they are far from homogeneous in their political allegiances. Young voters were among the key contributors to the success of the Greens in Germany, the UK, France, and the French-speaking part of Belgium. In other places, they were also very likely to vote for nationalist or far-right parties. For example, in Poland, support for the far-right, racist, and anti-EU Konfederacja party was, out of all age groups, highest among young voters. In Slovakia, young voters largely supported either the pro-European Progresivne Spolu coalition or the nationalist, far-right, and anti-establishment Kotleba. And the young provided significant support to Vlaams Belang in the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium.

The generational divide is radically different in each of the EU’s largest member states. In Germany, as many people under the age of 30 voted Green as they did for the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU), the SPD, and the Free Democrats combined. In France, the very young (under the age of 25) voted Green while the old (over the age of 55) voted for Macron’s party; Le Pen’s party won among voters aged 25-55. In Poland, PiS won in all age groups, but its support was the weakest among the young. Poles under 30 were most likely to vote for smaller parties, but these included both Konfederacja and the pro-European Wiosna. In Spain, strong support from voters across all age groups (including the young) proved critical for the Socialist Party’s victory. This disproved pre-election analysis, which forecast that the two established parties – the Socialists and the Partido Popular – should expect a much lower level of support among young voters, to the benefit of Ciudadanos and Podemos. In the end, the Socialist Party and Podemos both did well among the young, while Ciudadanos lost ground among them. In the UK, the young largely voted for the Greens, although the party struggled among voters over 55. The Liberal Democrats also had stronger support among the young than other age groups, while the Brexit Party won the election largely thanks to voters aged over 55. Italy is an exception to the rule: in all age groups, the League beat the Democratic Party, and the Five Star Movement fell to a distant third place.

This generational variance has differing effects on the big party groupings in the European Parliament. If only under-35s had voted in this election, the vote share for the EPP and the S&D would have been 40 percent rather than the 44 percent it eventually totalled. With 20 percent of the vote each, the EPP and the S&D would have maintained their positions as the two major political groups but would have had the Liberals and Greens – which would have won around 14 percent each – in hot pursuit. The EPP, the S&D, and the Liberals would still be able to form a three-party coalition if only the young voted. But, more importantly, the S&D, the Liberals, and the Greens might together have been able to do so without EPP. In this scenario, such an alliance could be further strengthened if it received the support of the more constructive and pro-European far-left parties. The geographical composition of the EPP would also change significantly: the CDU/CSU would lose its clear domination of the group, Les Républicains would fail to even meet the 5 percent threshold in France, whereas Fidesz would likely hold steady. Apart from the centre-right, the ECR group would be badly affected if only the youngest voters were able to vote. The Greens and the far left would be among the key beneficiaries.

There is also an important policy aspect to this. ECFR’s post-election analysis in the EU’s six largest member states reveals significant differences between age groups in their analysis of threats. Twenty percent of voters over the age of 55 – and just 9 percent of those under the age of 25 – saw Islamic radicalism as Europe’s single most important threat. Older people are also twice as concerned about migration as the young. In turn, 29 percent of voters under the age of 25 see climate change as the biggest threat, against just 15 percent in the population at large. Support for parties who talk ‘green’ should, therefore, grow in the coming years.

The new emotional map

In one key respect, the recent European Parliament election has seen the EU come of age. One can now begin to talk about a European electorate that took part in a pan-European debate. This is true from the impact of the climate discussion across most member states, to the sight of nationalist parties working together in an international alliance. The politicisation of EU policymaking has been a growing trend in recent decades but, despite the enduring importance of national issues in each of the 28 member states, one can begin to see some common characteristics in the way that voters approached these elections.

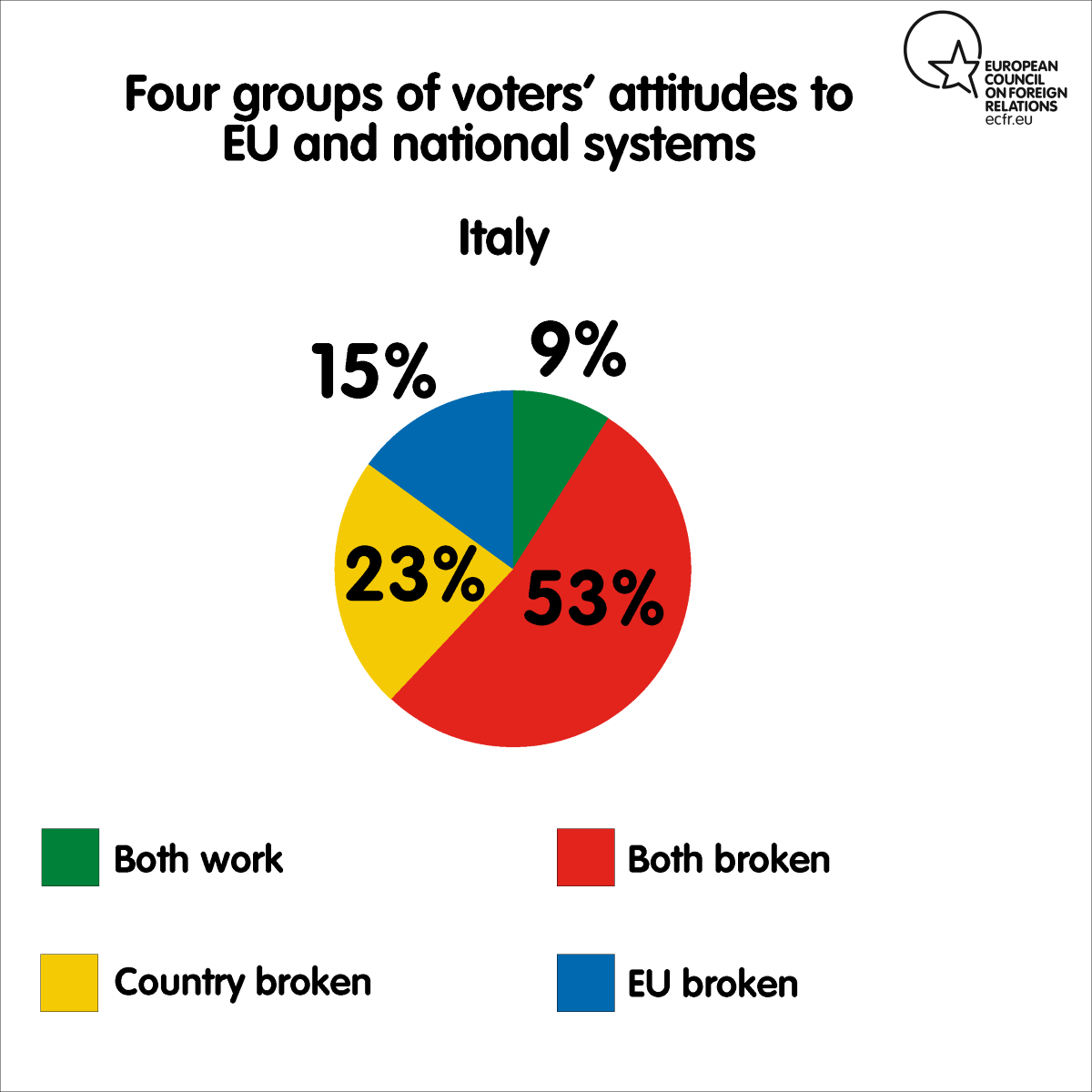

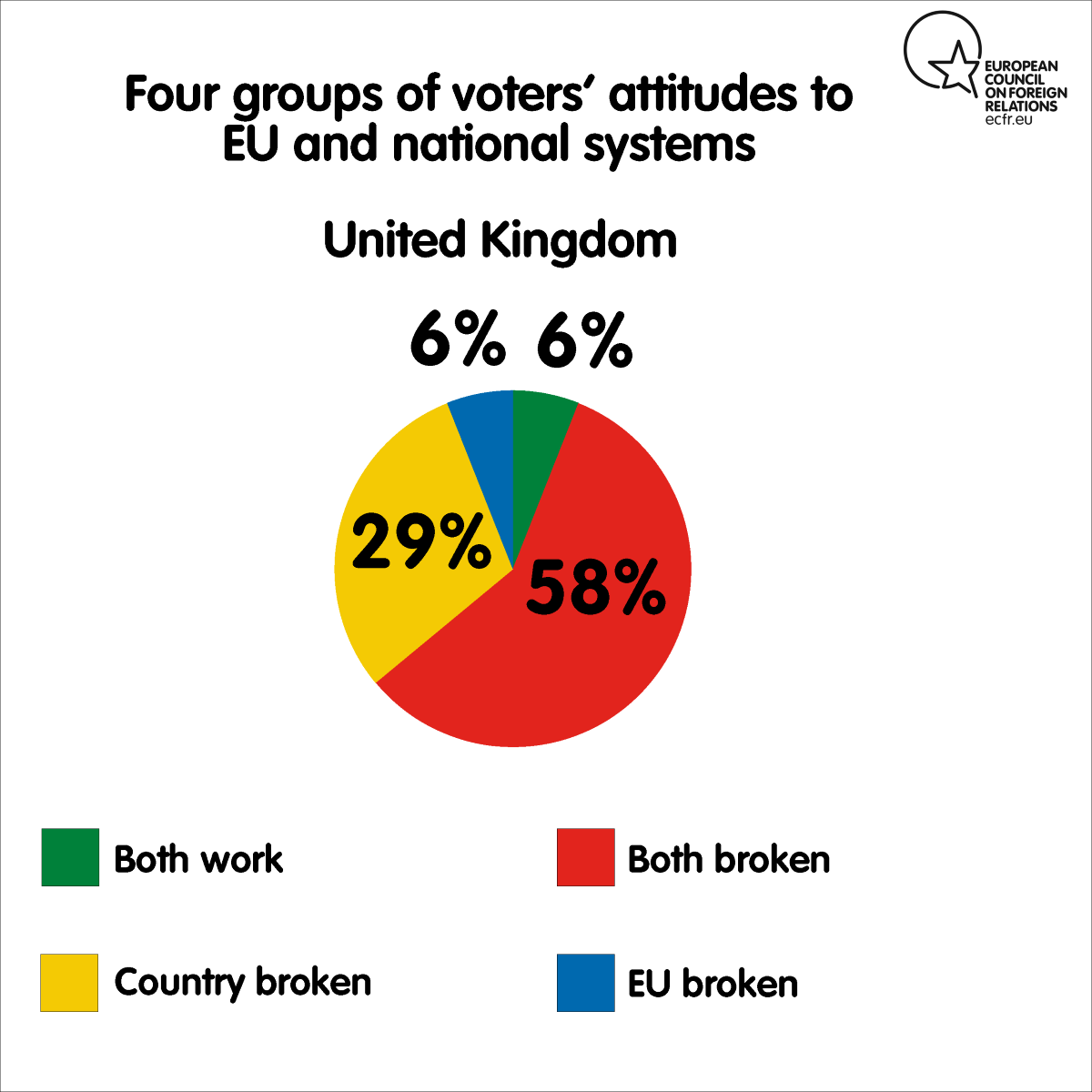

Firstly, European politics is change-driven. As ECFR’s pre-election research showed, more than three-quarters of voters believe that the political system is broken at either the national or EU level, or both. On a different question, two-thirds of voters were unsure that their children’s lives would be better than their own. Regardless of who voters supported in these elections, very few used their vote to endorse the status quo. In every national election battle, the parties that fared best were those that best encapsulated the argument that Europe can be different. This desire for change spurred the Green wave in Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Portugal. The promise of a different, fairer Europe brought big wins for socialist parties in the Netherlands, Spain, and Romania. But it was also the promise not, in the end, to destroy Europe but to change track to a “common sense” approach that assured victory for the League and Rassemblement National.

Secondly, European politics is now more emotional. The higher turnout in this election suggests that voters are giving the EU political system a chance to prove that things can be different, on the basis of the resilient optimism that ECFR’s emotional map of Europe identified in many parts of the electorate. But this may be a time-limited offer: the other key emotional characteristics that define the electorate are stress and fear. Safety in an uncertain world is also a key characteristic. Europeans believe that the risk of the EU collapsing is a distinct possibility. ECFR’s ‘day after’ survey indicates that 113 million people (28 percent of the electorate) went to the polls because they were concerned about the EU falling apart. And more than 125 million voters (32 percent of the electorate) took part because they were concerned about the risk of nationalism to the European project.

This emotional underpinning to the results shows that the EU institutions will need to find ways to reassure voters that their decision to turn out was worthwhile. If they fail to do this, there will be no way to bridge political divides. The EU will need to develop emotionally resonant policies, demonstrating to the electorate that the deal is not broken and that the political system can deliver on the issues that voters care about.

Conclusion

In the 2019 European Parliament election, both voters and leaders largely talked with like-minded people: in this split-screen election, they did not engage with the other side of the divide. But, now the election is over, this does not stop either side from drawing lessons about what the other was saying. Indeed, doing so may help each achieve their goals in Brussels. In a fragmented political environment, they will actually have little choice other than to engage.

The EU has become more political in recent years, particularly in relation to sensitive files such as migration. This election shows the extent to which Europeans now expect all EU institutions and many of the issues they handle to become scenes of greater political contestation in the coming months and years.

The next generation of leaders of the EU institutions may be appointed at the June European Council; they will quickly need to take account of these developments. Firstly, they, and the Strategic Agenda 2019 that they take forward, will need to look very different: status quo candidates for the institutions are unlikely to wash. The parties that did best in this election are those featuring the freshest faces: the new parties in the Liberal centre, from France and Spain to Romania and Slovakia; the Greens; the centre-right New Democracy in Greece; the Socialist Party in Spain; and anti-Europeans such as Salvini and France’s Jordan Bardella. The need for regeneration is clear. Support for the ‘older’ mainstream groups of EPP and S&D parties is much higher among older voters. Regeneration will, therefore, mean not only that parties should involve younger people higher up in their structures but also that they should engage with other parties beyond the mainstream.

In the European Parliament, the political groups as they are now will need to adapt to reflect voters’ wishes and desires for the future. If a majority coalition in the European Parliament requires all the largest political families to maintain agreement across all files, it is probably wrong to retain this majority approach to Europe’s current challenges in such a fragmented political environment. Coordinating such unwieldy alliances will take too much time and energy in the long term, and will suggest to voters that their message at the ballot box has not been heard.

On the policy agenda, the new EU institutions will need to provide answers to voters on climate change; security in an unstable world; and fairness – both economically and within the political system. Given the high priority that voters across parties assign to these issues, instead of spending too much time competing against each other for leadership roles on relevant committees, the European Parliament’s leaders should focus on common ground and push through policy initiatives where they have the power to do so. Where only the Commission or Council have the relevant powers, the European Parliament should press them to deliver on the mandate they have been given. And, to achieve results, political families should be prepared to work with parties beyond the mainstream, some of which have been strengthened nationally by this European Parliament election, whether as governments or as significant opposition forces. They must do this while ensuring that they preserve red lines on European values in the process. Voters gave a majority in the European Parliament to parties that campaigned for measures to protect democracy in the EU.

In this more political Europe, geography also poses a challenge. There has been a shift in the balance of representation of Europe’s regions within political groups, which will affect negotiations between them in both the European Parliament and the Council of the EU. ECFR’s Unlock pre-election research showed just how complex east-west and north-south divides really are. The appointment of the new leadership of the EU institutions over the coming weeks provides an important opportunity to send a signal that recognises the different ways in which Europeans think about the world.

As heads of state and government prepare to travel to the next European Council, scheduled for 20 June, they should acknowledge how the results of the European Parliament election reflect a changed, more political Europe – and how these results have changed Europe. With a more profound understanding of this new environment and the factors that shaped it, pro-Europeans must recognise that the most dangerous thing they could attempt in the coming years is simply to continue with more of the same.

Country analysis

France

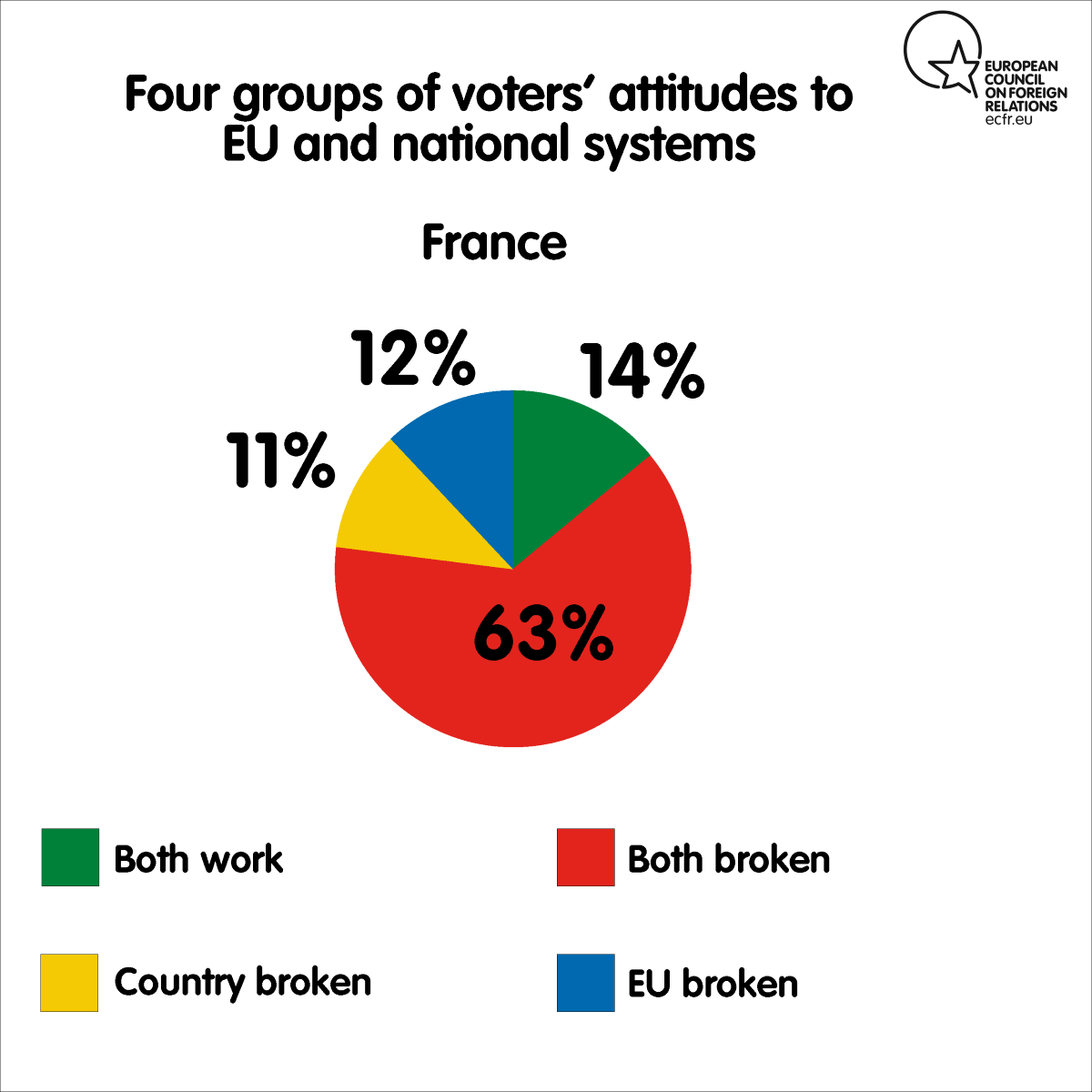

The meaning of the French results is complex and multilayered. On the one hand, the far right Rassemblement National came in first place, winning 23 percent of the vote. On the other hand, La République En Marche! (Renaissance) was less than 1 percentage point behind Le Pen’s party even after a very difficult year for the governing party, with huge political tension triggered by the gilets jaunes (yellow vests) movement.

On paper, France has been falling gradually out love with the EU in recent decades. Eurobarometer data about whether the French believe membership of the EU is a good thing show that France now tends to come in below the European average (61 percent in November 2018, compared to an EU average of 62 percent). ECFR/YouGov research from early 2019 showed that France was one of only four of 14 surveyed countries in which a majority of respondents stated that their European identity was less important than their national identity. ECFR’s Cohesion Monitor research shows France gradually moving away from the EU across a range of indicators. The ‘day after’ survey data further supports this analysis. When asked about the strong pro-EU stance that Macron has taken as president, a majority (52 percent) answered that he should concentrate more on domestic matters and spend less time working on EU issues. The only exception is La République En Marche! supporters, 78 percent of whom want Macron to push for EU reforms rather than to focus on a national agenda. There is also an age difference at play: 41 percent of young people believe Macron should focus on the national agenda, compared to 57 percent of the over-55s.

French voters were not necessarily using the ballot box to say they no longer want France at the heart of the EU. When asked who they would oppose their party entering a coalition with, they expressed the strongest feeling against nationalist leaders (after Macron, at 44 percent): Matteo Salvini (40 percent), Viktor Orban (37 percent), and Nigel Farage (28 percent). Rassemblement National supporters alone are, unsurprisingly, much more in favour of working with Salvini (66 percent), and Orban (44 percent), and slightly more with Farage (30 percent). Despite Rassemblement National’s election win, these figures do not suggest strong support among the French for a pan-European alliance that favours a Europe of nation states – for which these three leaders are poster boys. In fact, the strongest favourable answer was for Merkel, with 40 percent in favour of their party joining a coalition involving the German chancellor (88 percent among La République En Marche! supporters). The sister party to Merkel’s CDU in France is Les Républicains. But, in light of the French party’s dismal performance (8 percent of the vote), it may be that French voters are more attracted to the idea of the Franco-German tandem as a vehicle for maintaining strong French influence in the EU rather than to supporting the EPP itself.

ECFR’s ‘day after’ survey shows that many respondents claim to have been motivated to vote for their party because of climate change. More than 50 percent of respondents claimed this for La République En Marche!, Place Publique (the Socialists), and La France Insoumise, as well as the Greens. The strong improvement in the Greens’ performance – despite larger parties such as La République En Marche! campaigning hard on the climate too – points towards a certain purity of this issue in voters’ minds. The survey also revealed that worries about the rise of nationalism were also an important factor in getting voters to the polls. This was true among all pro-European party supporters (except for Les Républicains) – 67 percent for La République En Marche! and 58 percent for Place Publique. Security and immigration both played an important role among supporters of Les Républicains and of Rassemblement National. The economy was significant for the far left and the centre-left, with more than 50 percent of Communist, La République En Marche!, and La France Insoumise voters identifying this as an important issue. Only 31 percent of Rassemblement National supporters identified the economy as a key issue.

Interestingly, while the old care more about reducing immigration than the young do, they are also more worried about the EU potentially collapsing. But, equally, they are more worried about the possibility of EU enlargement. This suggests that, overall, older voters in France are looking to preserve the status quo.

In a further indication that the French and the EU are not yet going their separate ways, almost half of voters (48 percent) believe that decisions by the French government and the EU institutions are equally important in addressing the issues they are concerned about. French voters’ second most common answer, at 24 percent, is that the EU is the most important actor, with the national government alone the choice of only 16 percent. This is a more pronounced split in favour of the EU than pro-European Germany (on 26 percent for the EU level and 20 percent for the national level), and the opposite of the UK (17 percent for the EU level and 28 percent for the national level). Support for both the “EU and national levels of response” was particularly significant on some of the main driver issues for voters in this election: 58 percent believed that both the EU and the national government should take on the threat of nationalism; 52 percent believe this for migration; 46 percent for climate change; and 42 percent for the economy.

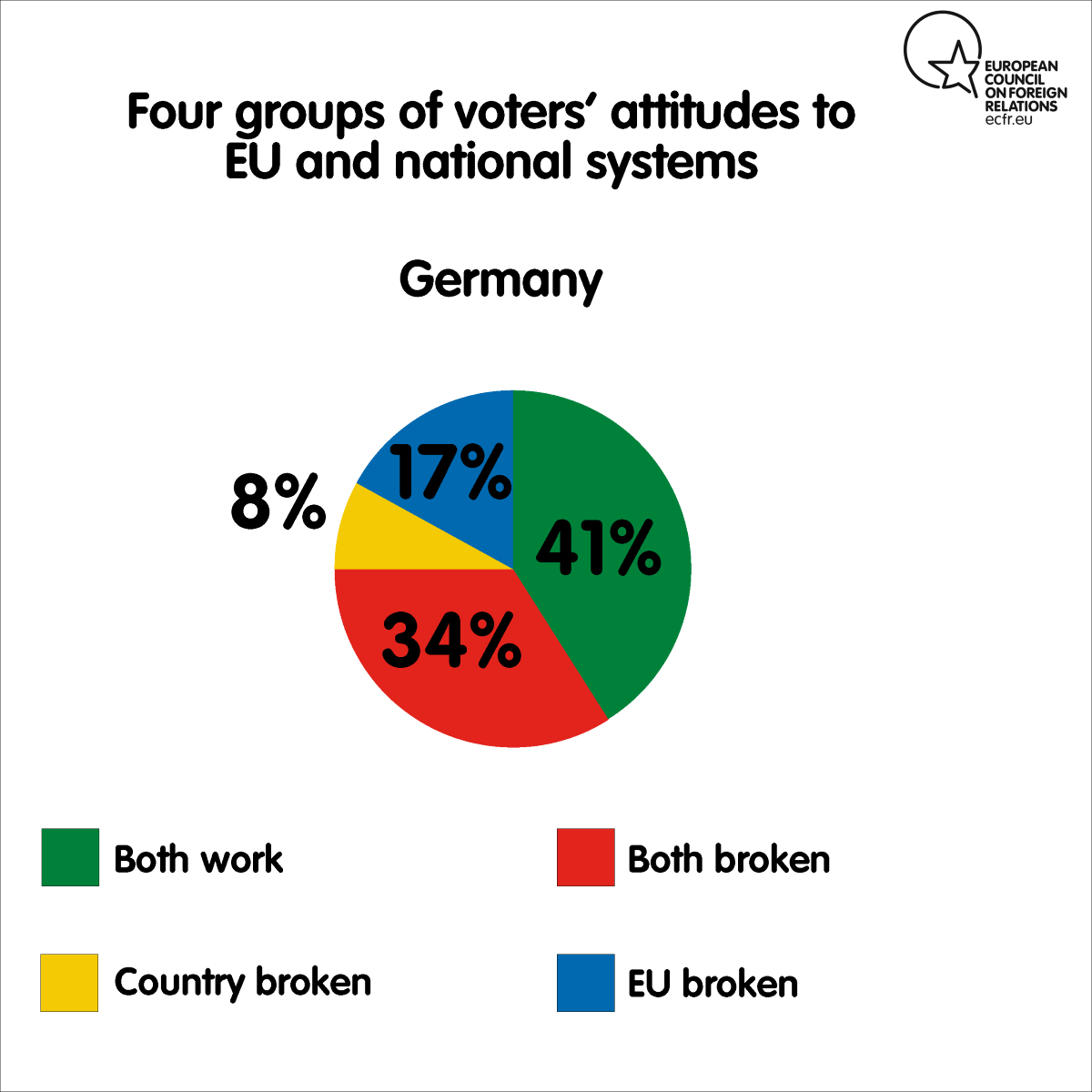

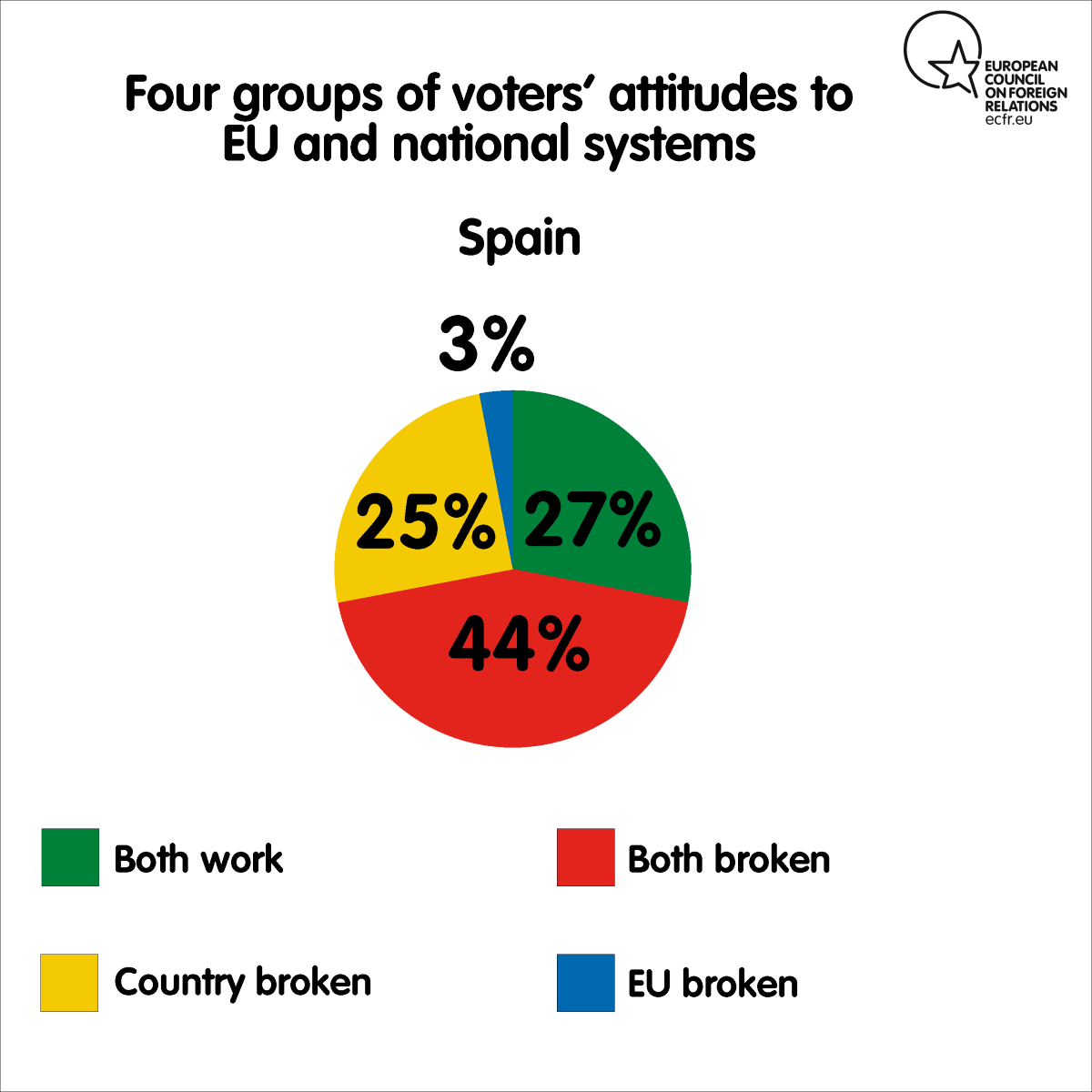

The results in France are the clearest illustration that this was the “system is broken” election that ECFR predicted in its pre-election analysis. In the January 2019 ECFR/YouGov survey, France was the country with the highest percentage of respondents – 69 percent – who believed that both the national and the political systems were broken. This broader context is important for understanding falling French confidence in the EU’s ability to deliver on the issues that matter. Voters in France remain just as unconvinced, if not more so, that their national political system can help them. In ECFR’s ‘day after’ survey, 70 percent of French respondents answered that they believed the EU system was broken, and 76 percent that the French national system was broken. Rassemblement National’s success in the European Parliament election drew on this oppositional status. Le Pen supporters proved remarkably loyal: 78 percent of those who voted for her in the 2017 presidential election supported the Rassemblement National list in 2019. But Le Pen also managed to secure support from those unimpressed by the performance of the parties they had previously supported, including Les Républicains and La France Insoumise. To the extent that Rassemblement National promised change, much of its success came from votes against the system rather than support for any part of it.

Germany

German voters sent two key messages in the European election. Neither is directly related to EU policymaking, but both have significance for the priorities and actions of German MEPs, and for the German government in the Council. The results confirm trends in public opinion visible before and after election day.

The first message is one of discontent with the current CDU/CSU–SPD governing coalition. Combined, these parties lost around 18 percentage points in comparison to their showing in the European election in 2014 – when such a Grand Coalition was also in government. Merkel’s CDU fell 7.5 percentage points, while its Bavarian sister party the CSU gained 1 percentage point. The SPD plummeted 11 percentage points to 15.8 percent – its worst ever result in a nationwide election – and party chair Andrea Nahles resigned as a consequence. The coalition partners’ joint vote share was 10 percentage points below what they achieved at the last general election, with losses divided almost equally between each side of the coalition.

Voters’ turn away from the traditional parties primarily benefited two very different groups: the Greens and the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). Compared to the 2014 European election, the Greens doubled their vote share, to 10.7 percent, and the AfD gained nearly 5 percentage points. More importantly, the Greens’ success was not down to their policy on Europe but because of their role in German politics. The Greens won votes from supporters of all other parties represented in the Bundestag, including the AfD. And their rise has continued since the election. The latest polls show that they would gain 26 percent of the vote if a national election were held now, compared to 27 percent for the CDU/CSU, 13 percent each for the SPD and AfD, and 7 percent each for Die Linke and the liberal Free Democrats.

The AfD’s advance did not replicate the progress it made at the last federal and state elections. Indeed, the rise of the anti-EU vote in Germany was weaker than was feared during the campaign. Turnout increased by 10 percentage points, which benefited the Greens more than the AfD. On the other hand, support for the AfD grew strongly in east German states. And, on taking up their seats in the European Parliament, AfD MEPs are unlikely to become a bridge to other political groups. Their voters show no overwhelming support for a unified far-right coalition and are sceptical about lining up with the leftist fringe. In contrast, ECFR/YouGov data show that supporters of the Christian Democrats and of the Greens are pragmatic about their parties joining a range of different coalitions between centre-left and centre-right.

The second message of the European Parliament election concerns the issues that face Europe. Opinion research in Germany shows that energy and climate have risen among German voters’ concerns, and now top the list. Sixty percent of Germans want to see greater efforts in the transition to renewable energy, and 40 percent believe that attempts to phase out power generation from coal should be accelerated. In Germany, the Greens are associated with the environmental agenda more than any other topic; it is the issue that has defined them since the founding of the party in the 1970s. It speaks to an increasing bifurcation of the public that the party most opposed to climate politics and the transition to renewable energy is the right-wing AfD. While the CDU/CSU and the SPD will now seek to strengthen their profile on environmental protection, the AfD is set to become yet more vocal in its opposition. In this regard, the strong shift of young voters towards the Greens is significant. As ECFR/YouGov data demonstrate, the Greens outperform the SPD in all age groups under 55, and they come out on top among those under 35.

With regard to the EU policy agenda, the rise of the strongly integrationist Greens means that the overall German contingent of MEPs remains firmly pro-EU. The CDU and the SPD lost six and 11 seats respectively, while the Greens gained 10 seats, the Free Democrats gained two, and the CSU gained one. ECFR’s ‘day after’ survey shows that Green MEPs bring with them a mandate to speak out for the defence of democracy and the rule of law in all EU states, for integration, and against nationalist regression in the EU – all of which the survey indicates were key drivers in raising turnout among Green voters. The Greens’ voice, in particular, will be heard in Brussels and Strasbourg, not least because their voter base was mobilised by the climate issue. This will give the traditional green pedigree of the party additional importance. And German Greens will have a particularly strong voice, as they now are the largest national contingent in their parliamentary group, holding 21 of 74 seats. While the German role in the EPP group should only be moderately affected by the loss of five seats, the 16 German SPD members have now fallen behind the delegation from Spain’s PSOE, which has 20 seats.

The influence of the German results on European policymaking is unlikely to be dramatic: despite the rather striking shift in the political landscape, a certain continuity remains. The rise of the pro-EU Greens compensates for the loss of the pro-EU SPD, while the AfD appears to have peaked before the European Parliament poll. There does remain one warning sign, however: the east-west dimension of the German results. Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, two-thirds of east Germans and 55 percent of west Germans now see more differences than commonalities between people living in each part of the country.

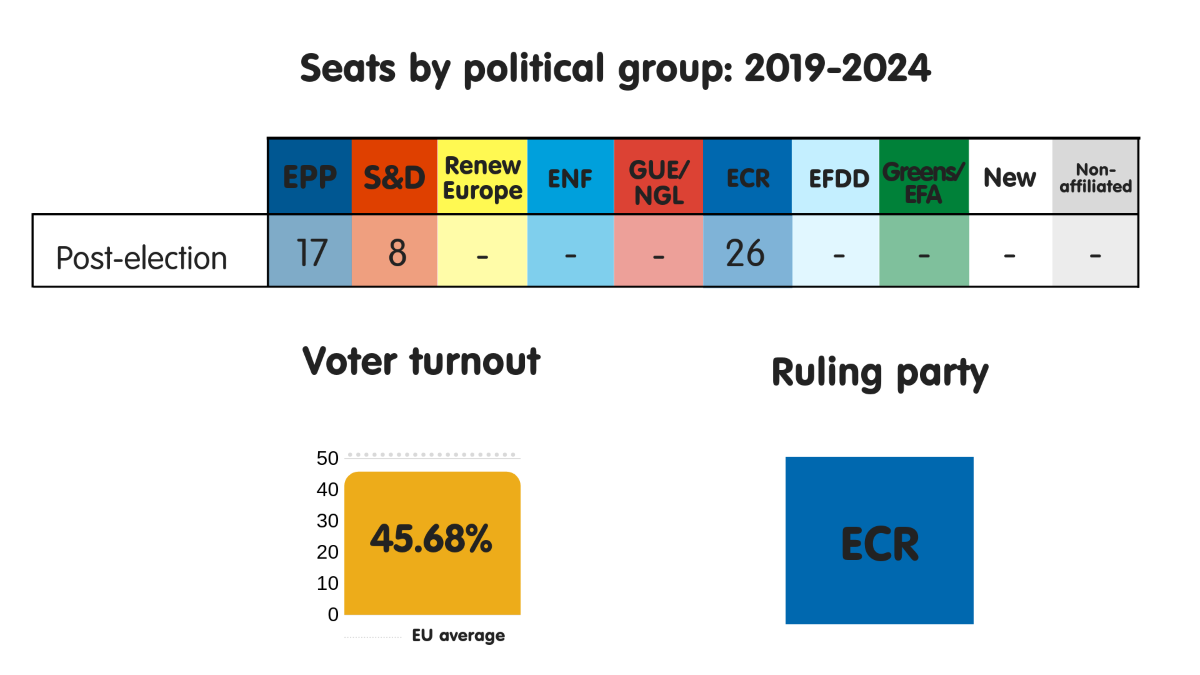

Italy

The 2019 European election results in Italy have added further complexity to an already-complicated political landscape, at least in the short term. Salvini and his League party were the clear winner, securing 34 percent of the vote, while Luigi Di Maio and his Five Star Movement were the big loser, coming it at just 17 percent. This is a remarkable switch of places: in the 2018 general election, the Five Star Movement won 32 percent of the vote and the League 17 percent.

Views of the EU were not the primary motive for turning up to vote: only 24 percent of Italians did so to support the party that best reflects their opinion of the EU, trailing those who said they chose the party that best reflects their values and principles, at 37 percent.

When asked what the biggest threat for Europe is today, Italian voters identify economic crisis and trade wars: each scores 32 percent, followed, at some distance, by nationalism on 13 percent, migration on 12 percent, and Islamic radicalism and climate change on 10 percent. Generally, all party groups agree on the economy as the biggest concern. If one looks at economic forecasts and results for 2019, it is clear why Italians feel this way: the European Commission predicts Italy’s growth rate for 2019 to be just 0.2 percent. The country’s unemployment rate in April of this year stood at 10.2 percent and, among Italians aged 15-24, is an estimated 31.44 percent. Foreign policy issues such as Russia, Turkey, and China do not attract Italians’ interest, with only 1 percent, 2 percent, and 3 percent of voters pointing to each as important respectively.

Views of the political system give a clearer picture of how Italians feel today: a majority of the electorate, spread across all political groupings (51 percent), believe that both the national and EU systems are broken, with this feeling more marked among voters over the age of 55. On migration, Italians are equally worried, with 36 percent more concerned about people coming into Italy, and 36 percent more concerned about Italians leaving. League voters are the group most worried about immigration, with 41 percent expressing concern about this. The highest levels of concern about emigration are found among Democratic Party supporters. These results show that the migration- and security-driven political campaigning that dominated Italian public debate in the last two years has not had a blanket effect on the Italian electorate, especially the young: 41 percent of people aged 18-25 are most concerned about their peers leaving Italy. Indeed, Italian voters aged 18-25 cite nationalism and climate change as the biggest threats.

On climate change, Green party Europa Verde gained only 2 percent of the vote, even though 39 percent of Italian voters in ECFR’s ‘day after’ survey agreed that climate change is a major threat. In the past, climate change was significant for Five Star Movement supporters, who were drawn to the party’s strong environmental focus. Both the Democratic Party and even Forza Italia have also lately voiced support for a greener and more sustainable Europe.

The upcoming weeks will be crucial for the role Italy assumes in Europe in the next five years. Salvini may have been the big winner in his home country – but in Europe he failed. Despite its success, the League will not belong to any of the largest political groupings in the European Parliament, which means it will enjoy only limited political leverage in Brussels. Italians’ views of which other European leaders could prove allies for the governing parties are quite varied: 30 percent of League voters favour an alliance with Orban, while 58 percent support one with Le Pen, with only 21 percent supporting Farage. But only 15 percent of Five Star Movement supporters would accept an alliance with Orban, while 27 percent could tolerate Le Pen and 24 percent Farage. Indeed, Five Star Movement voters are much more comfortable with the idea of a coalition with centre-left, Green, and Liberal parties – 31 percent back such a set-up. Joining forces with far-right and far-left anti-EU parties wins the support of only 9 percent of Five Star Movement voters. The constituencies of the two parties that make up Italy’s governing coalition are even further apart at the EU level than they are domestically.

Italy is a divided country – socially, economically, and politically. Salvini and Di Maio have made clear they plan keep the government in place, but the electorate is split on this: 47 percent believe the coalition should continue in office while 36 percent think it should resign. A majority of League and Five Star Movement (59 percent) supporters believe it should remain in place. Meanwhile, 53 percent of Democratic Party supporters and 65 percent of Forza Italia supporters believe the coalition should resign.

Domestic economic reforms and the current debate between Europe and Italy about fiscal rules will likely be the real battleground for the Italian government, in its relations with the EU and inside the EU institutions. Much will now depend on how Salvini decides to interact with Brussels and other European capitals. He will finally need to choose between the role of troublemaker and that of policymaker.

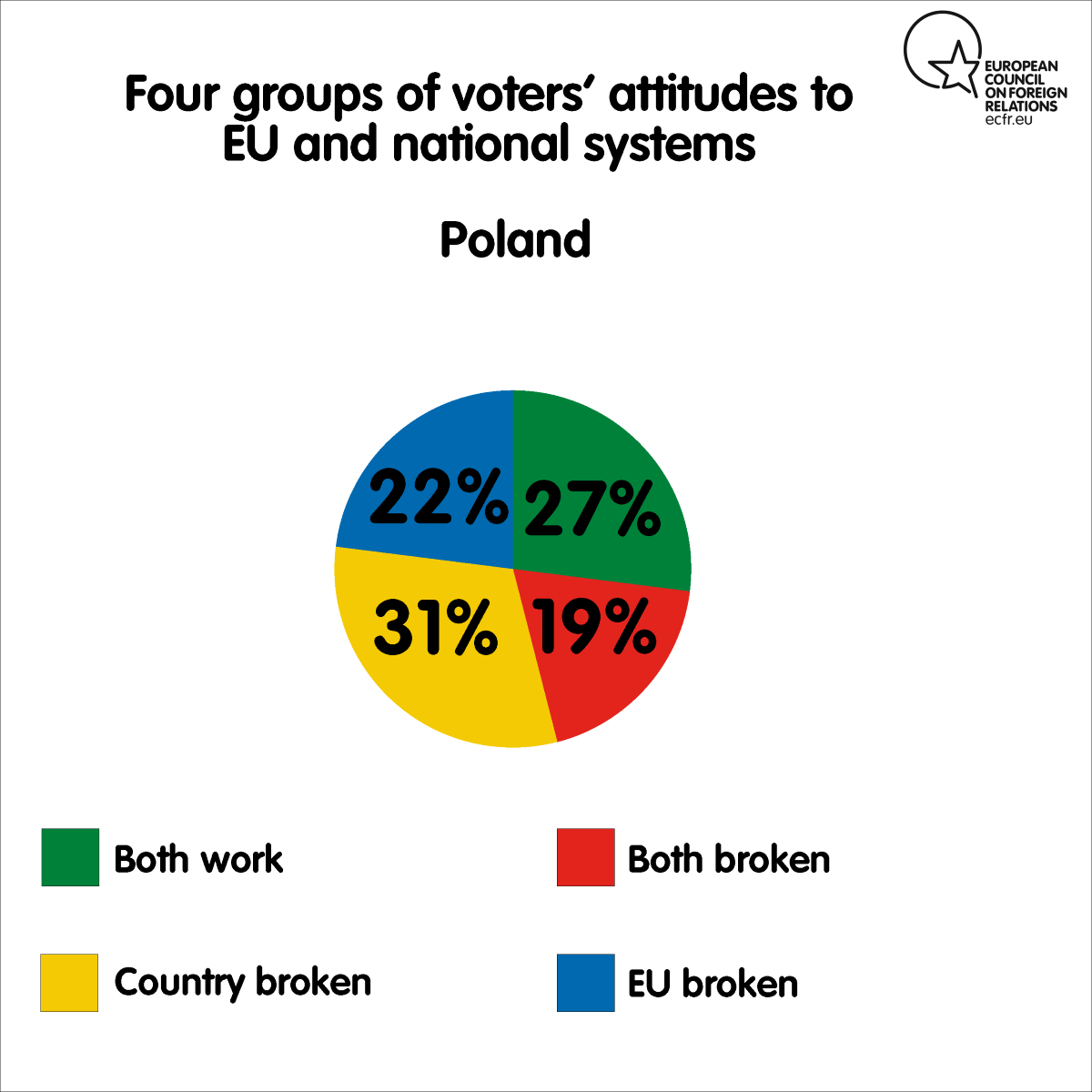

Poland

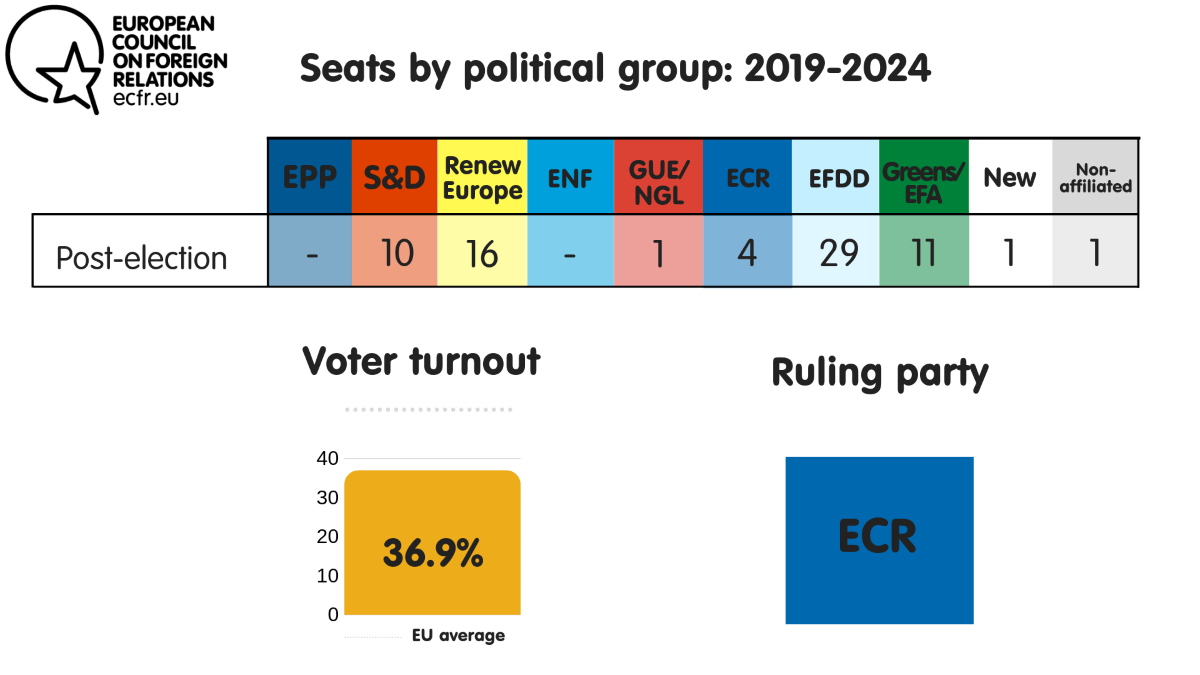

The European Parliament election was, to a large degree, a referendum on the governing Law and Justice (PiS) party. To the extent that European issues featured in the vote, it was very much within the frame of existing domestic political divisions. With stark polarisation in the country and little change in voters’ party loyalties, turnout was the name of the game – and PiS won. This victory, however, happened despite Polish voters’ continued support for the EU. It came about through a combination of the low salience of the EU in the campaign, deft political messaging from PiS, and the lack of a compelling European message from the opposition.

The election pitted PiS against the European Coalition (KE) – an alliance of pro-European parties of various ideological backgrounds. Political polarisation deprived other political forces of oxygen; only newly formed progressive party Wiosna crossed the electoral threshold, with 6 percent of the vote. EU issues did not even necessarily drive KE voters to the polls: ECFR’s ‘day after’ survey revealed that half of KE supporters voted either to oppose the government (26 percent) or to oppose another party (22 percent), a sentiment one can safely assume was directed at PiS. Supporters of PiS, on the other hand, cited their party’s values and principles (35 percent) as a reason for their vote, but also often cited their support for the government (27 percent) or opposition to another party (10 percent) as a reason for the choice. Further underscoring the low salience of EU politics in the election, a significant proportion (37-44 percent, depending on the question posed) of respondents did not have an opinion about which alliance their party should join. Of those that did, quite a few placed their parties well outside their actual European political groups.

While KE and Wiosna voters are of a single mind on the EU – seeing it as functioning well and the body most capable of tackling major threats – PiS voters are split in their appraisal. For PiS, its staunchest support comes from people who view the EU as broken but are satisfied with Poland’s political system. That said, many PiS voters have a favourable attitude towards both. Similarly, any potential alliance with the centre-right and the far-right is met with discomfort by a sizeable minority of PiS supporters, who also view the EU as a bulwark against their own government’s excesses. One can contrast this with pessimist, more unambiguously anti-European voters of Italy’s League or France’s Rassemblement National.

Furthermore, judging by comparisons with how people say they voted in the 2015 general election, the party’s base has moved noticeably towards pro-Europeanism. While the core of PiS voters (52 percent) believe both that the EU is broken and the national political system functions well, more than 35 percent believe both function effectively. This suggests that, in the recent European Parliament election, PiS formed a coalition between sovereigntist voters – satisfied with its national conservative, ‘Europe of the nations’ rhetoric – and mild, status quo-orientated pro-Europeans whose support is predicated on economic prosperity and welfare policies. The two groups differ significantly on the issues that motivated their votes and on what alliances their party should form on the European level. Furthermore, PiS voters are fairly evenly split on whether the EU protects them against the excesses or failures of the national government (35 percent) or whether it stops the government doing what is best for the country (40 percent). KE focused on mobilising its supporters and was unable to increase the salience of European policies. It thus failed to shine a light on the contradictions inherent in the PiS approach.

One popular current explanation for the PiS victory involves a heated debate about the Catholic Church, whose entanglement in alleged sex scandals led to a defensive mobilisation of conservative electors. But ECFR’s data do not bear this out. A significant majority (68 percent) of respondents – and a plurality of PiS voters (47 percent) – believe that the influence of the Catholic Church should decrease, while only a small fraction (5 percent overall, 9 percent of PiS voters) think it should increase. There are simply not enough aggrieved Catholics to explain the size of the PiS lead; indeed, the party gained a lot of votes in areas that are not particularly religious.

Overall, Polish voters identify Islamic radicalism (20 percent), economic crises and trade wars (14 percent), Russia (11 percent), migration (11 percent), and climate change (11 percent) and nationalism (11 percent) as the main threats the EU faces. But these perceptions are split along party lines. PiS supporters cite Islamic radicalism, migration, and Russia most often. Only 2 percent of PiS voters identify nationalism in Europe as a threat, a minuscule figure that stands in stark contrast to the 26 percent of KE voters and 27 percent of Wiosna voters who do so. Climate change is a peculiar case: there is a broad consensus that it is both taking place and that it should be a priority. The issue has some salience: 11 percent consider it to be the biggest threat. These numbers are more or less in line with other European countries, but what sets Poland apart is the near-total lack of climate policy discussion in the electoral campaign, aside from some of Wiosna’s messaging.

Although the election campaign was national in content, the results offer some insights into what role Poland may decide to play on the wider European stage. If PiS wins the parliamentary election in the autumn, it will be due to its ability to retain its moderate, pro-European voters. This, in turn, would provide a strong argument for a more constructive approach in the Council, as suggested in a Politico op-ed by the prime minister, Mateusz Morawiecki. Polish policy contributions to the EU Strategic Agenda, and rumours of the nomination of Jadwiga Emilewicz, a moderate, as the energy commissioner would further support this approach (although it is doubtful whether it would extend to domestic policies, such as the rule of law). Climate change, currently a latent issue, has the potential to become a political battleground if any group credibly focuses their messaging on it and seeks to effect a shift in the Polish stance on the issue.

Spain

ECFR/YouGov data gathered in the lead-up to and after the European Parliament election confirm that Spaniards are among the most ardent believers in European integration. The election campaign saw all the main Spanish parties agree on the need for Europe to deliver more on economic, social, and international politics. Even Vox, the new far-right party that has emerged in the last year, supports EU membership and does not make sovereignty or ‘regaining control’ from Brussels a key theme. In 2014 left-wing party Podemos won seats in the European Parliament on an anti-euro, anti-German, and anti-austerity platform. But even Podemos has toned down its criticism of the EU and stopped framing it in terms of the markets and the elite against the people.

Consistent with domestic polls, the main issue Spanish voters are worried about is the economic crisis and, more particularly, jobs (22 percent). This is followed by the rise of nationalism both at home and in Europe, which worries 17 percent of voters. Climate change (13 percent) is also an important preoccupation. As in other European countries, there is an interesting generational divide here: younger voters are three times as likely to care about climate change as older people (31 percent versus 12 percent). And, like elsewhere in Europe, voters are aware of the choices implied in meeting this challenge: most support protecting the environment despite the economic costs of doing so, with only Vox voters an outlier in this respect.

Corruption is also a dominant preoccupation: almost half of Spaniards (44 percent) believe that the political system is broken. This may fuel support for populist parties on both the right and the left. It could also help explain why Spanish voters have faith in the EU to address their main concerns. Overall, they think that most problems should be tackled on both the national and EU levels (51 percent). In contrast, only 18 percent believe that the issues that most concern them should be tackled on the national level alone.

Support for the EU in Spain stems not only from material concerns such as the benefits of integration. ECFR’s Unlock data shows that 46 percent of Spaniards agree that being European is as important to them as their own nationality. Less than 20 percent say their national identity is more important, a share significantly lower than that in Germany, Italy, and France. Despite austerity and the legacy of inequality and unemployment left by the 2008 financial crisis, Spaniards are deeply in favour of the euro. Indeed, they are much more supportive of it than their fellow Europeans are. With 42 percent of them worried about unemployment (second only to Italians in this) and 39 percent about corruption (second only to Romanians), Spaniards see in Europe more of a helping hand than a hindrance to addressing these two ills. A particularly positive finding is that Spaniards worry much that the EU will collapse than voters in other member states do.

Spaniards are more worried by the re-emergence of nationalism than they are about migration. In fact – like Poland, Hungary, and Romania – Spain is one of several EU countries in which people confess to being more worried about their own nationals emigrating than about others arriving. Spanish voters are concerned about emigration (34 percent) and both immigration and emigration together (37 percent). Partido Popular and Vox voters are more worried about immigration than about emigration, while the reverse is true among Socialist Party and Podemos voters. This implies that the split screen nature of the European Parliament election was particularly apparent in Spain.

Overall, voters in Spain think their government has managed the increase in migration fairly badly. This is the case for most voter groups, but Vox supporters think the government has handled it very badly. Still, the European Parliament election suggests that Vox has not succeeded in turning immigration into a national issue. Indeed, the party performed significantly worse than it did in the general election held on 28 April, just one month before the European election. Regardless of whether Spaniards worry about immigration, they do not seem to want to consider the kind of solutions on offer from Vox.

Despite their pro-European attitudes, Spanish voters are very ideological about coalition building. Reflecting the deep polarisation of current domestic politics, most Partido Popular voters would rather see their party strike coalition agreements with the far right represented by Vox than with the Socialists. A similar picture emerges for the Socialists, whose voters are as uncomfortable with leftist parties such as Podemos as they are with centre-right parties such as Ciudadanos and the Partido Popular. Equally, Podemos voters do not see themselves working with European leaders such as Merkel, Macron, or Frans Timmermans.

The results of the election have generated optimism about the possibilities for increasing Spain’s role in Europe, thanks to the strong electoral performance of its pro-European parties. This, combined with the leadership opportunities provided by Brexit and Italy’s anti-European turn, leads Spanish citizens to expect that their government and their political parties in Brussels will be key players in Europe in the next five years.

United Kingdom

Despite the UK’s odd position in the European Parliament election – with its membership of the EU likely to last only six months – British voters still took the opportunity to register their views on the EU. When ECFR asked what the main reason was for voting for the party they chose, the most common answer by far was to support the party that best reflected their opinion on the EU. The second most common answer was to support the party that best reflected their values and opinions.

This election has been widely viewed as a statement on the handling of Brexit by the UK’s major parties: the argument runs that the Conservative and Labour together won around 80 percent of the vote at the last general election in 2017, but at this election they saw their support collapse, with Labour coming third, on only 14 percent of the vote, and the governing Conservative Party in fifth place, on slightly less than 9 percent. But this interpretation does not reflect what voters actually thought as they went into polling stations. ECFR’s research reveals that only 9 percent said they were expressing opposition to the government, 7 percent said they were opposing a party or parties that they disliked, and only 4 percent that they were expressing support for the British government.

The big winner in the European Parliament election in the UK was, of course, the Brexit Party, which won 32 percent of the vote. It will now use its platform on the floor of the European Parliament to direct its megaphone more at London than the rest of Europe, but also to support any wrecking tactics from Salvini’s new alliance or an ECR that has become more Eurosceptic (due, for example, to Fidesz and PiS joining that group).

ECFR’s data show that, overall, the UK electorate has a more nuanced view on the future of the EU than the Brexit Party’s victory would first suggest. Asked whether national- or European-level cooperation was best suited to handling the threats they were most concerned about, voters’ most common answer was – as in most other EU states – to back both levels equally. Indeed, 42 percent of British voters gave this response, while 28 percent named the UK government alone and 17 percent the EU alone.

If Labour is treated as a pro-European party, the public was split cleanly between pro-European voters who cared most about climate change and the rise of nationalism and anti-European voters who cared most about migration and Islamic radicalism.

- Labour voters care most about climate change (35 percent) and the rise of nationalism (23 percent).

- Liberal Democrat voters care most about the rise of nationalism (42 percent) and climate change (20 percent).

- Green voters care most about climate change (46 percent) and the rise of nationalism (26 percent).

- Change UK voters care most about nationalism (35) and climate change (26 percent).

On the other hand, for anti-European party voters, the top issues were as follows:

- Brexit Party voters care most about migration (23 percent) and Islamic radicalism (27 percent).

- Conservative Party voters care most about Islamic radicalism (19 percent) and migration (12 percent). However, 15 percent also care about the rise of nationalism.

But the reasons voters said they chose different parties did not follow such clear lines; here, the economy and security had a greater importance. Conservatives said they voted for their party because of the economy (31 percent) and climate change (28 percent). Among Labour voters, 55 percent said that they voted the way that they did because of climate change, but after that the most common answer (38 percent) was also the economy. Liberal Democrat voters are motivated by climate change (50 percent), security (47 percent), nationalism (53 percent), and worries about the collapse of the EU (47 percent). Green voters are motivated firstly by security (83 percent) and climate change (32 percent), but other issues are also important to them. Respondents who voted for the Brexit Party said they did so due to the economy (56 percent) and immigration (50 percent).

Young voters said they chose their party because of climate change, the economy, and fear of the collapse of the EU. For older people (aged 55 and over), protecting democracy was a bigger motivation, although the economy, security, and EU trade deals also mattered.

Though climate change appears to have been a big mobiliser in the UK as elsewhere in this election, there are nevertheless important differences between supporters of different parties. The vast majority of British voters (83 percent) agree that more should be done to protect the environment, even at the potential cost of economic growth. But 35 percent of Brexit Party supporters and 24 percent of Conservative Party supporters disagree, compared to an overwhelming 94 percent of Labour voters and 90 percent of Liberal Democrat voters who agree. Older people were more likely to disagree (20 percent) with this stance, while younger people agreed almost universally, at 96 percent.

If ECFR’s survey shows that the reasons UK voters voted the way they did in this election were complex and multidimensional, it also shows that the picture on Brexit itself is much clearer. The UK remains deeply, perhaps irreconcilably, divided on how to handle Brexit. Those in favour of a second referendum make up 44 percent of the electorate – while another 44 percent oppose another vote. Only 12 percent said they did not know. When asked what they would do in such a referendum, 47 percent said they would vote to remain, 38 percent that they would vote to leave, 8 percent that they would not vote, and 7 percent did not know. No obvious lessons emerge from the European Parliament election on the way forward on Brexit.

Methodology

This report drew on two sources of data. Firstly, ECFR and YouGov carried out a ‘day after’ survey in the six largest EU member states: Germany (fieldwork: 27-31 May 2019; number of respondents: 2,000), France (27-29 May 2019; 1,000), UK (27-29 May 2019; 1,600), Italy (27 May – 3 June 2019; 1,000), Spain (27-30 May 2019; 1,000), Poland (27 May – 4 June 2019; 1,000). Secondly, in the last 10 days of the campaign (17-26 May 2019), ECFR’s 28 associate researchers used a standardised survey to analyse the manifestos and campaign promises of political parties in their respective countries.

About the authors

Susi Dennison is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations and the director of ECFR’s European Power programme. In this role, she explores issues relating to the strategy, cohesion, and politics of achieving a collective EU foreign and security policy. She led ECFR’s European Foreign Policy Scorecard project for five years, and since the beginning of this year has led the research for ECFR’s Unlock project.

Mark Leonard is co-founder and director of ECFR. He writes a syndicated column on global affairs for Project Syndicate and his essays have appeared in numerous other publications. Leonard is the author of Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century and What Does China Think?, and the editor of Connectivity Wars. He presents ECFR’s weekly World in 30 Minutes podcast and is a former chair of the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Geo-economics.

Pawel Zerka is policy fellow and programme coordinator with the European Power programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He is an economist and political scientist, with expertise in EU affairs and Latin American politics and economy. His latest publications include ‘The 2019 European election: How anti-Europeans plan to wreck Europe and what can be done to stop it’ (with Susi Dennison, ECFR Flash Scorecard, February 2019), and ‘Europe’s underestimated young voters’ (ECFR Commentary, May 2019).

Teresa Coratella is the programme manager at ECFR’s Rome office. She joined ECFR in 2011, and previously worked for the Warsaw-based Institute for Eastern Studies as partnership manager and analyst for southern Europe. She holds an MA in European Interdisciplinary Studies from the College of Europe, Natolin Campus, with a focus on the EU as a regional actor. A graduate in political science and international relations and native Polish-Italian, her main areas of interest are Polish and Italian foreign policy and the EU’s eastern neighbourhood.

Josef Janning is senior policy fellow at ECFR and head of its Berlin office. He is an expert on European affairs, international relations, and foreign and security policy, with over 30 years of experience in academic institutions, foundations, and public policy think-tanks. He has published widely in books, journals, and magazines.

Andrzej Mendel-Nykorowycz is the programme coordinator for ECFR’s Warsaw Office. He holds an MA in international politics from Aberystwyth University and a BA in international relations from the University of Warsaw.

José Ignacio Torreblanca is a senior policy fellow and head of ECFR’s Madrid office, a position he has held since the launch of ECFR across Europe in 2007. His topics of focus include populism and Euroscepticism in Europe, common foreign security and defence policy, and EU domestic politics and institutional reform.

The ‘Unlock’ project

The ‘Unlock Europe’s Majority’ project aims to push back against the rise of anti-Europeanism that threatens to weaken Europe and its influence in the world. Through polling and focus group data in 14 European Union member states with representative sample sizes, ECFR’s analysis will unlock the shifting coalitions in Europe that favour a more internationally engaged EU. This will show how different parties and movements can – rather than competing in the nationalist or populist debate – give the pro-European, internationally engaged majority in Europe a new voice. We will use this research to engage with pro-European parties, civil society allies, and media outlets on how to frame nationally relevant issues in a way that will reach across constituencies as well as the reach the ears of voters who oppose an inward-looking, nationalist, and illiberal version of Europe

Acknowledgements

As with the writing throughout the Unlock project, this report draws extensively on conversations with, and insights from, many individuals across the wider ECFR family. In particular we would like to thank Philipp Dreyer for his amazing analysis of the ‘day after’ survey and his advice on the draft. Susanne Baumann, Swantje Green, Simon Hix, Adam Lury, Ana Ramic, and Vessela Tcherneva have also provided comments and input which have greatly improved the report. The paper would not be half its current quality without the brilliance and patience of our editor, Adam Harrison. We would also like to thank Katharina Botel-Azzinnaro for her painstaking work on the graphics, and Pablo Fons d’Ocon and our network of national researchers for their fast and careful work in developing the manifesto data set. We would also like to thank the team at YouGov for their ongoing collaboration with us in developing and analysing the pan-European surveys. Despite all these many and varied forms of input, any errors in the report remain the authors’ own.

Associate researcher list

- Sofia Maria Satanakis, Austrian Institute for European and Security Policy (AIES)