Health sovereignty: How to build a resilient European response to pandemics

Summary

- The coronavirus affected EU member states in different ways and to different extents, but almost all found that their public health relied, more than they understood, on goods or services from third countries. This reliance undermined Europe’s capacity to respond autonomously.

- The EU bodies coordinating the response and providing an early warning system were slow to act and requests for aid from EU member states went unheeded, creating feelings of abandonment among the worst-hit countries.

- Europe must improve its early warning systems, supply chain resilience, medical research and development, and cyber security and technology, to act decisively in future public health emergencies.

- Europe can build greater health security by creating common strategic stocks, diversifying and reshoring supply chains, strengthening investment protection in innovative companies, investing in R&D, and coordinating efforts in multilateral forums.

Introduction

“We consider this an act of modern piracy,” steamed Berlin’s interior minister, Andreas Geisel, in April 2020. “Even in times of global crisis, there should be no wild west methods.” Geisel had just learned that 200,000 protective masks intended for Berlin’s police force had effectively disappeared. They had not been stolen by brigands off the coast of Somalia but rather ‘diverted’ in Bangkok by corporate fiat. The US company that made them had been prohibited from exporting medical products by an emergency law invoked by President Donald Trump. Even as Geisel fumed that US actions did not comply with international rules, Trump put the matter rather starkly: “We need these items immediately for domestic use. We have to have them.”

Crises tell us a lot about ourselves and the world we live in. The coronavirus crisis has taught us that the health system is an element of security as much as the defence industry or telecoms infrastructure. The absence of health security threatens the ability of societies to function, economies to prosper, and nations to compete in geopolitical competition. Health emergencies can also erode democracy and human rights at home, perhaps permanently, as we have already seen during the current crisis.

Health security, like many other areas of international life, is both cooperative and competitive. We live in a world of interconnections – people, goods, information, and of course microbes flow across borders with ever-increasing speed and quantity. These flows create enormous benefits, but, as the pandemic demonstrates, they also create societal vulnerabilities and expose us to risk. States can limit these flows but only at enormous cost to their economies, their culture, and their people.

Populations expect their governments to protect the nation against the downsides of globalisation. They want, in other words, their governments to retain strategic sovereignty, to be able to retain their capacity to act, and to control their nation’s destiny. As recent events have shown, the ability to nurture and protect an effective health system – one that can withstand pandemics and other crises – is a key element of strategic sovereignty.

Achieving strategic sovereignty in the health area is no simple task. There is no option for ‘health autarky’ in the modern world. States clearly need effective international cooperation to tackle their health problems. To staff and equip their health systems, they need access to global labour markets and supply chains. To treat diseases, they need medicines and information from foreign sources and international organisations. To achieve progress in treatment and prevention, they need to work collaboratively in transnational research networks.

But states also compete in the health arena, sometimes quite viciously. They seek to capture key technologies and intellectual property, they try to attract key medical staff, and, particularly in times of emergency, they struggle over scarce resources such as vaccines and protective equipment. They also use health issues as wedges in larger geopolitical competitions, by, for example, using their control over supply chains to extract geopolitical concessions.

Managing cooperation amid geopolitical competition is a fundamental challenge for health security. For European Union member states, cooperation at the European level is a key part of the solution. If member states are to retain their ability to provide effective health security to their populations, they will need effective cooperation with their European partners, both through the EU and other mechanisms.

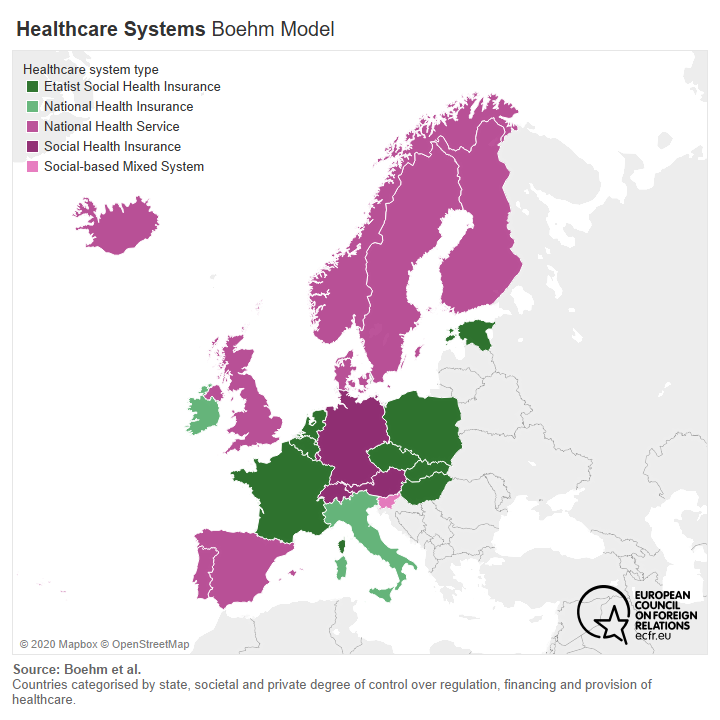

Of course, healthcare is and should remain largely a national competence. Healthcare systems across Europe vary dramatically, reflecting different historical experiences and cultural preferences. Some are centralised, some are federal, some are local, some are administered by social insurance companies, some countries have a private healthcare industry, others limit healthcare to the public sector. These often-fundamental differences make cooperation, and certainly convergence, in Europe difficult.

But, as in other areas, protecting European strategic sovereignty in health does not require a centralised solution. It just requires European-level efforts that can serve as a forum for cooperation and setting standards, act as a force multiplier for national efforts, and ensure much-needed European solidarity. European populations agree. According to a 2017 Eurobarometer Survey, 60 per cent of Europeans support greater EU engagement in health issues. ECFR surveys show that policy professionals in every member state overwhelmingly support a greater EU role on health policy, except in Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic.

This paper seeks to lay out a concept of European health sovereignty and to propose some European-level efforts that can increase the capacity of EU member states to protect their populations in the face of increased competition over health issues.

Towards this end, the first section maps out the key constituent elements of health sovereignty. The next two sections seek to understand the geopolitical and European context for health sovereignty, with a focus on what other powers are doing and how European states differ in their approaches. The final section of the paper makes recommendations for how, through the EU and other mechanisms, member states can work together to promote policies that better protect health sovereignty.

The political context for health sovereignty

Efforts to protect health sovereignty take place within an extremely competitive geopolitical context. The covid-19 crisis has highlighted and exacerbated existing fissures in global politics. In particular, the crisis arrived in the middle of an emerging great power competition between the United States and China and seems to have dramatically worsened their conflict. It has also caused one of the deepest recessions in a century. The international political and economic conditions make responding to the health crisis more difficult. On every issue, from developing a new medication that provides relief to covid-19 patients to the eventual distribution of a vaccine, the world can expect fierce fights over supplies and narratives as great powers seek geopolitical advantage.

The crisis has also painfully highlighted that, while China and the US are fighting over dominance, no one is really in charge. Europeans might have hoped that the world would unite in the face of the common challenge the coronavirus poses, pooling national resources and coordinating a global response to these pressing health and economic difficulties, which transcend the borders of any nation state. But this has not been the case. For decades, Europeans have based their policies on the assumption of a multilateral, rules-based order, the idea of free and fair trade – and multilateral crisis resolution, such as in 2008, when the G20 and other international institutions worked together to avoid the financial crisis mutating into a global depression.

This time everything seems different. As the US and China squabble, international cooperation has often ended up as collateral damage. In the US, Trump’s staunchly anti-Chinese economic adviser Peter Navarro made clear early on what he thought of international cooperation or even allies: “In crises like this, we have no allies”, he said at the end of February. A few weeks later, reports surfaced that the Trump administration had tried to acquire CureVac, a German biotech company, or to get exclusive access to a potential vaccine it was developing. As noted, the US reportedly tried to redirect deliveries at airports around the world to increase supplies at American hospitals.

China has been even worse. Beijing has often weaponised mask and PPE deliveries for geopolitical gain, and at the beginning of the crisis it exploited Europeans’ scramble for medical goods. Europeans were lacking such goods partly because they had exported a vast amount of protective gear to China a few weeks before, and yet China tried to establish a narrative of coming to the rescue when the EU was presented as leaving Italy, Spain, Serbia, and others behind. In France, the Chinese embassy took advantage of the situation to demonstrate the “dominance” of China’s model over the French one.

From a European perspective, neither the American nor the Chinese model looks attractive. Both sides use the ever more brutal confrontation between them to distract from their respective failures in the crisis. Europe often ends up caught in the middle of the US and Chinese competition. Meanwhile, because of their struggle, the multilateral institutions that are so important from the point of view of European values and interests – from the G20 to the World Health Organization (WHO) – are invisible or even falling apart. Europeans clearly need to protect their own health sovereignty.

Europe together and apart on health policy

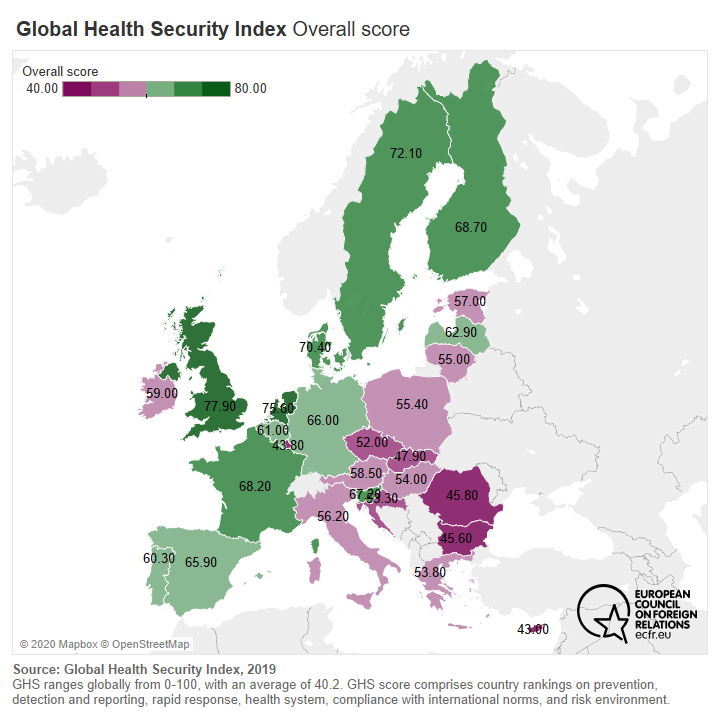

If the coronavirus has vastly changed the context for health sovereignty, it has not affected all member states the same way. This variation reflects both the differential impacts of the virus, the differences in healthcare systems, and the different approaches to containment across the member states. The appendix to this paper documents the distinct experience of six member states (Bulgaria, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Spain). The purpose of this section is to give a cross-section of responses to the coronavirus across Europe. By understanding the approaches and viewpoints of European capitals, policymakers may more clearly identify what a pan-European approach to health sovereignty might look like. While these capitals by no means represent the totality of the EU, they do demonstrate many of the key divides between member states in terms of capabilities, policy responses, and healthcare systems.

But their experiences do reveal that the coronavirus has not fundamentally altered the internal European debate on health sovereignty. The issue has now become a much greater priority across Europe and many countries find themselves considering measures that would not have been top of mind before. But there are significant differences of opinion among individual EU member states about how they should respond to the competitive geopolitical struggle to achieve health security, what support they expect from their European partners, and how they can best shape the multilateral environment to protect European health sovereignty. These differences reflect long-standing divides on the best approach to health security and on what the appropriate role is for the EU in this field. Member states have never agreed on what the EU’s role in health policy should be and, although coronavirus has changed the policy environment dramatically, there is still no consensus.

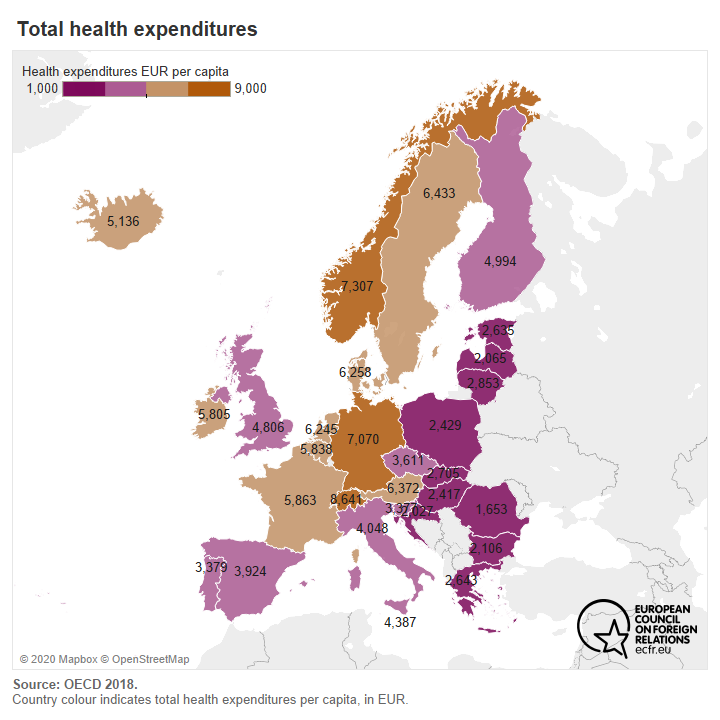

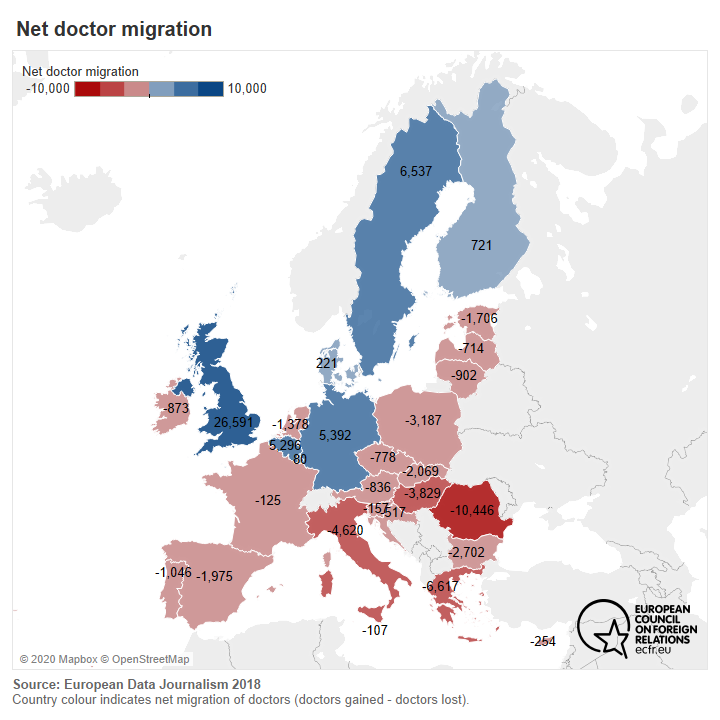

Some of these disagreements stem from the massive differences in national health systems and their unequal access to resources and capacity for treatment, between and within countries. From rural to urban or peri-urban areas, access to medical care and medical personnel varies widely. In capitals and bigger cities, citizens often have more choice between university, public, or private hospitals. In remote areas, care is often more difficult to access because it might be scattered across the country and there are usually fewer options.

Within this context, we can still divine a set of common problems and complaints that stem from the experience of the pandemic. All of the member states ECFR examined complained about their dependence on global supply chains and the vulnerability that this presents in a crisis. And all of them sense that both the EU and multilateral forums failed them in this crisis. All of them want more from both levels. They are also united in identifying a need for greater solidarity on the European level to help them overcome the shortcomings of their own national healthcare system. And all the countries examined (except Poland) joined the declaration of the Alliance for Multilateralism, which sent a strong signal of support to the United Nations and the WHO for their response to the pandemic. ECFR surveys also show that 75 per cent of EU policy professionals surveyed across all EU countries support greater EU coordination of health policy, including a majority in all countries except Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic.

The healthcare systems of individual EU member states showed enormous variation in their preparedness and responses to the virus. Some of this variation stems from specific policy decisions or mistakes in particular countries. But some of it is also structural and highlights that healthcare inequality persists across the EU. Richer and larger states have better-funded healthcare systems and are better able to provide for themselves in times of crisis. They attract doctors and other medical personnel from other EU states, they can maintain greater stocks of vital equipment, and they can negotiate from a stronger position with neighbours in Europe and beyond. Wealthier member states want and need less support on the European level. Indeed, some of them fear that allowing the EU a greater say in healthcare may reduce their preparedness. Smaller and poorer states, particularly those that are losing medical personnel to wealthier countries, feel a greater need for European solidarity and pan-European coordination of international negotiations and resource allocation, particularly in times of crisis. This state of inequality affected the capacity of authorities to be decisive about lockdown measures, to make testing available, and to ensure the most exposed population – the elderly and those with underlying health conditions – had prime access to care and will eventually have priority access to vaccinations.

Everyone wants European solidarity. But they want it more to solve their own problems than those of others, just like in other policy areas. Still, the commonly recognised need to achieve greater self-sufficiency during crises, and especially when there is harsh geopolitical competition, provides a clear basis for greater European action to protect health sovereignty. Even the largest and most capable member states cannot maintain their sovereignty in a healthcare crisis without greater solidarity and coordination from the EU. If the EU wants to develop an effective response to the growing geopolitical competition in health sovereignty it will need to forge a coherent position that represents a compromise between the various views. While compromise is the basis of EU-level decision-making, the question remains what that response needs to do. In the next section we turn to this question and ask what steps are needed to protect health sovereignty.

Components of health sovereignty

If the EU is going to protect health sovereignty, we first need to define what it is. This section looks at the four capabilities necessary to safeguard Europe’s capacity to act in the event of health emergencies. These include early warning systems, supply chain resilience, medical research and development, and cyber security and technology. We will assess European capacities in these areas.

Early warning systems

In the EU, early warning of crises falls to the national level. This means that each EU member state is responsible for carrying out their own activities in this space. The EU is mostly involved in coordinating cross-border health threats. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) is an EU agency set up for this purpose. It hosts 290 employees whose role is to cooperate with national institutes. Together with the European Commission and public health authorities in EU countries, it launched a web-based platform: the Early Warning and Response System (EWRS) in 1998, “to control serious cross-border threats to health, including communicable diseases”. The platform’s purpose is to pool information from all member states’ – on a voluntary basis – in order to make information on risk assessment and risk management possible and to build better coordinated health policies and actions. The system works as a shuttle. This means that it provides member states with the measures required to protect public health while counting on them to relay information back to the centre and notify them of any type of alerts or issues in their country.

Twenty years later, in April 2018, the European Innovation Council (EIC) coincidentally launched a bid for a prize to develop an early-warning system to help prevent outbreaks of infectious diseases and reduce their impact should they occur. The result of the bid will be announced in the first quarter of 2021. The system is expected to produce “a reliable, cost-effective and scalable early warning system prototype to forecast and monitor vector-borne diseases, which should encompass innovative technological solutions integrating big data derived from different sources (e.g. space-borne, airborne, in-situ and citizen observations) in the Earth observation domain.” The EIC also announced at the end of April 2020 that in the wake of the covid-19 crisis it is putting forward €150m, in addition to the €164m already announced in March 2020, to fund breakthrough ideas specifically tackling the covid-19 pandemic. These additional sources of funding, on top of Horizon 2020 funding for health research and innovation, appear to confirm that the current early warning system and the ECDC proved deficient at the beginning of 2020 in alerting member states to the dangers posed by covid-19, while the virus had spread from China, to Thailand, South Korea, Japan, and Australia.

For weeks, the ECDC maintained its stance that “European countries have the necessary capacities to prevent and control an outbreak as soon as cases are detected”. As such, it failed in its primary mission: to sound the alarm and reinforce Europe’s capacity to face such health crises. Perhaps one of the weaknesses of the ECDC in these cases is that it relies heavily on the provision of external information to formulate recommendations.

The EU also has access to other monitoring and early warning systems operated by the WHO, individual governments and NGOs or research platforms, such as the Global Public Health Intelligence Network. But relevant information was not provided early enough to contain the virus. Despite these initial failures, the EWRS grew increasingly important as the virus spread, becoming the main coordinating platform for EU efforts. Confirmation of its growing importance can be seen in Britain’s desire to rejoin the EWRS despite its withdrawal from the EU.

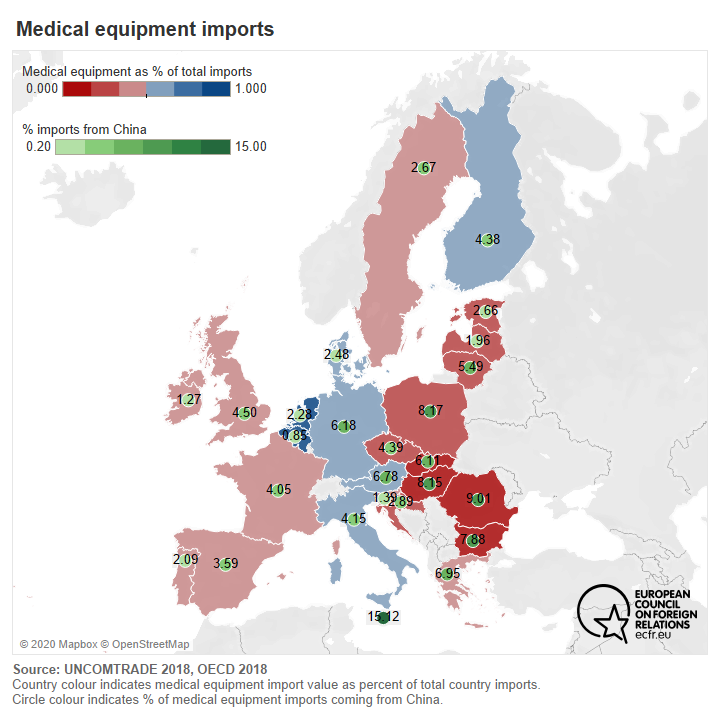

Supply chain resilience

Ensuring supply chain resilience has been an EU priority during the crisis. The covid-19 pandemic has exposed Europe’s – and the world’s – dependence on India and China for certain key medicines. Recognition of this reliance has sparked fears and anxieties among European citizens, to the extent that it has prompted some to request these supply chains be resourced within Europe. The outsourcing of production of active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) and generics by the pharmaceutical industry to Asia occurred in the 1990s. In doing so, outsourcers allowed a number of companies to depart from the strict environmental norms manufacturers had to comply with in Europe and the US.

According to the Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance, a federation of 10,000 companies, it provides 20 per cent of worldwide sales of generics, 60 per cent of worldwide sales of vaccines, and 60 per cent of antiretroviral drugs for HIV/AIDS treatments, confirming the country’s status as the “world’s pharmacy” – the main reason being that nowhere else in the world offers cheaper production conditions.

When the virus broke out in China at the end of 2019, the subsequent lockdown of the country meant that exports and production chains came to a halt. India started limiting its exports of APIs “because India’s manufacturers rely heavily on imports of their APIs from China.”

Supply chain resilience is part of the four working groups of the covid-19 taskforce of the European Medicines Agency (EMA), alongside the therapeutic response, business continuity and impact, and human resources. The taskforce’s supply chain role is to coordinate efforts to manage the risk of supply shortages of centrally authorised medicines, liaise with industry trade associations on risk assessments on the resilience of supply chains and mitigating actions, and share information with international partners and the WHO on covid-19-related medicine shortages.

A major difficulty posed by the fragmentation of medical supply chains is retaining the capacity to trace a given product from its source. It has always been difficult to implement quality control when the production base is extremely far away in a country with different health standards and sometimes a different political and value system. But that process becomes even more complicated when the supply chain experiences disruption.

The crisis has also demonstrated some serious deficiencies in access to medical equipment, particularly in the availability of tests and masks, at the European level. Most EU member states had to import such items from China. It fell upon each individual member state to identify what their capacities were, exposing their failure over many years to provide the ECDC surveillance system with adequate data – highlighting the now strategic dimension of health.

Germany was better prepared than a number of other member states in its capacity for testing. It was therefore able to implement its lockdown policy later than most other countries and with less stringent measures. In France, the population’s disenchantment with how the government has handled the crisis stems partly from the lack of medical equipment available, including masks and items needed for testing.

The European Commission provided guidelines to member states about testing methodologies, focusing on “state of the art” testing kits for the two types of test that exist: those that detect the virus and those that detect antibodies proving that patients have built up an immunity. Scientists recommended using the tests in accordance with WHO protocols.

In addition to scaling production of tests, the situation highlights even more the need to pool resources to validate tests at an EU level and to centralise all results at the EU and international level. A month after the crisis first hit European shores, the European Commission advised the establishment of a common approach to testing. This would help to increase information sharing on the situation in different countries; establish a network of coronavirus reference laboratories across the EU; improve the availability of tools to assess the performance of tests; fight counterfeit devices via reinforced European and international cooperation; coordinate supply and demand via existing institutions and joint procurement; and foster solidarity between member states by “ensuring a fair distribution of available stocks and laboratory equipment focussing on where they are most needed.”

At the beginning of June 2020, Denmark initiated a letter that was signed by France, Germany, Spain, Belgium, and Poland, raising questions about Europe’s preparedness for the pandemic. Importantly, it raised the need to adopt a common European approach to prepare for the next crisis. The letter points to the initial failures of the bloc in mapping the available medical equipment and supplies to member states that needed them most in order to mitigate the pandemic. It also calls on the EU to coordinate the development of a coronavirus vaccine, possibly with EU funds.

Medical research and development

The ability to ramp up research and development to create new treatments and vaccines has proven to be a critical element of health security in the crisis. In normal times, it takes a decade to develop a vaccine. The covid-19 emergency has led scientists around the world to fix an 18-month limit now. It will take at least that long to undertake the stage of pre-clinical development in laboratories and then test it to determine the optimal dose of medicine to efficiently produce immunity and protect patients from risks of toxicity. Once this first stage is passed, clinical trials on humans can begin. Only when trials determine that a vaccine has been found can its patent be issued, and mass production of the vaccine begin. Currently, over 500 projects are undergoing the clinical trial phase, but there is no guarantee that a vaccine will be found.

The European Discovery clinical trial, which started in April 2020, will compare four antiviral treatments on serious covid-19 cases: Sanofi’s hydroxychloroquine; AbbVie’s Kaletra with or without Merck’s beta interferon; and Gilead’s Remdesivir. Results will be compared to those obtained with the standard care available in hospitals.

To ensure the validity of Discovery and other trials, the EMA published at the end of April 2020 a guide to the validity of clinical trials. But in the global race to find a vaccine, the US and China are far ahead of the EU. They are the two largest patent producers in the world, and the first to issue a patent for a vaccine against covid-19 will, of course, benefit from those windfalls. The economic incentive of developing a workable vaccine naturally contributes to current China-US tensions.

But the race is not over yet. Europeans can still compete. A study by the German think-tank DGAP highlighted that “The European pharmaceutical industry alone has a market value of more than 200 billion euros, and invests more than 35 billion euros annually in research and development.” Its industrial base is strong and innovation is a key topic for industry giants, as scientific discoveries are protected by a patent for 20 years, meaning that the laboratory responsible for that discovery finds itself with a monopoly situation and very high profits.

But having a strong pharmaceutical industrial base in your region does not guarantee control of its products. In May 2020, the head of the French firm Sanofi, one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, declared that it would initially reserve its vaccine supplies for the US, because it had put more money into developing it than Europe. It did not take long for the French government to react and brand this “unacceptable”. Since then the head of Sanofi’s French branch has attempted to offer reassurance to the EU and its citizens on this question, stating that the vaccine, if found, would be made available to everyone.

The EU has been at the forefront of a fight to give multilateral impetus to finding a vaccine that would be “available, accessible and affordable to all”, notably by organising a global pledge on 4 May to which international institutions and state leaders were invited. The pledge managed to raise €7.4 billion. While most countries and institutions sent their highest-level representative, the US did not participate, and China sent its ambassador to the EU – a much lower-level official.

France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands recently announced the creation of the “Inclusive Vaccine Alliance”, whose aim is to ensure that a coronavirus vaccine is made available and affordable for all Europeans. The countries declared that they are already working with the European Commission and pharmaceutical companies to fulfil the ambition of supplying up to 400 million vaccines. In addition, the German economy minister, Peter Altmeier, announced that the government was buying a 23 per cent stake in CureVac for €300m, as a means to double down on efforts to find a coronavirus vaccine

Cyber security and technology

The pandemic has demonstrated that building and maintaining secure data networks is a critical element of modern health security. While the virus was spreading in Asia, the hardest-hit countries in the region developed tracing apps to keep track of infected patients and to trace the spread of the virus. They did so with different tracking options and with a varying degree of intrusion on privacy. One argument in favour of these apps is that our smartphones are already monitoring our movements and public health authorities and researchers could use this information to better track the spread of the virus and mitigate the lockdowns – that we might not be able to replicate to such an extent again – with targeted messaging and targeted care.

Debates within Europe have shown that data protection and privacy are paramount for European citizens, who, for now at least, have made clear they would only accept tracking apps if their effectiveness were confirmed. In the longer term, the new awareness of pandemics certainly poses difficult questions for Europeans about their willingness to sacrifice some liberties in exchange for greater security. To that end, European member states are currently reviewing solutions that trace contacts with minimal data collection and privacy invasions. But Europeans have not reached a consensus on the issue yet. Norway and Lithuania both withdrew their tracing apps due to privacy concerns, while France, Germany, and Italy rolled out their apps in the first days of June 2020.

The pandemic has also normalised the use of telemedicine services to limit the movement of possibly infected patients while providing them with consultations. This has been effective for patients and doctors. Artificial intelligence (AI) is also being used to detect symptoms and “provide advice”. The deployment of AI in the field of medicine could help in cross-confirming recommendations based on medical histories, travel, and exposure. As a US epidemiologist explained, “in aggregate, this data has the potential to surface patterns of symptoms and diagnoses that might illuminate unusual clusters of illness.” Unfortunately, the elderly and most economically vulnerable people may lack access to the internet for a doctor’s consultation or an AI chatbot, which risks worsening an already deep divide in access to healthcare.

How to build European health sovereignty

The need to knit together these capabilities into a coherent plan for health sovereignty is a daunting task. But as Jean Monnet predicted in 1976, “Europe will be forged in crisis.” The EU’s leaders have often drawn consolation and even inspiration from Monnet’s optimism. But if history has frequently proven Monnet right, his predictions do not deliver results automatically. Crises only forge Europe if they increase European solidarity – if they bring Europeans together rather them push them apart. Ensuring that greater solidarity emerges from crises requires purposeful action and wise leadership.

Recent crises have not always forged Europe as well as Monnet might have liked. The 2009 financial crisis added a host of policy instruments at the European level, including the European Stability Mechanism, and vastly increased the role and visibility of the European Central Bank. But it also opened a deep and often bitter rift between wealthier, northern member states and more indebted, southern member states. It is a rift that persists and often poisons European debates to this day.

The 2015 migration crisis also exposed the fundamental weakness of executing European-level solutions. When the EU attempted to impose a European solution to the crisis, some member states effectively rebelled and the actions of specific national governments ended up dominating the response. The crisis also damaged European solidarity – front-line states in the south felt abandoned by their European partners, eastern European states resented edicts from Brussels that did not align with core national interests, and western European states lost faith in the EU’s ability to manage a crisis.

The crisis management lesson was a stark one but is important to recall in the context of the coronavirus pandemic. The EU can only lead if its member states want to follow. It does not have the coercive mechanisms of a more powerful federal state. To encourage solidarity, it needs to provide resources and solutions to its member states, not challenge their authority to protect their own citizens in a crisis.

In 2019, when Turkey unleashed a new wave of refugees in frustration over Europe’s policy on Syria, the EU and most member states took the approach of reinforcing the Greek and Bulgarian governments’ hard-line approach, even though it was controversial. The impact on the migration issue is debatable, but the solidarity effect was clear. At that moment, Greece and Bulgaria needed their European partners and received important assistance. “[Turkey’s] threats did not succeed,” the Greek prime minister exulted. “They crashed into the readiness of the Greek people and our European solidarity.”

In its long-term response to the current pandemic crisis, the EU should consider following a similar approach. Health remains not just a national competence but a core area of national life. As the outbreak of the virus has demonstrated, the EU’s current competencies in the sector of health policy are extremely limited. But there are many ways that the EU can, and indeed already does, follow a solidarity-driven approach.

According to Art. 168 TFEU, the bloc is supposed to limit its public health efforts to a coordinating role. The organisation of national health systems remains the prerogative of each individual member state. As such, EU health policy and interventions must complement rather than challenge national responses. They should aim to “protect and improve the health of EU citizens, support the modernisation of health infrastructure and improve the efficiency of Europe’s health systems”.

In addition to a senior-level working group on public health, where national authorities and the European Commission discuss strategic health issues, the Commission’s DG SANTE (Directorate for Health and Food Safety) is tasked with supporting the EU’s efforts to reach the aforementioned goals, by proposing legislation and providing financial support, through Horizon 2020, the EU’s cohesion policy, and the European Fund for Strategic Investments. As of now, the EU has advanced legislation on patients’ rights in cross-border healthcare, pharmaceuticals, and medical devices (pharmacovigilance, falsified medicines, clinical trials) as well as serious cross-border health threats, among others.

However, these limited competencies were detrimental to the EU’s initial management of the crisis. In the end, because of inequalities between health systems and differing positions between member states on the need to Europeanise health policy, it took the European Commission some time to endorse the coordination role that individual member states so needed. A fundamental issue that arose in the debate was whether stakeholders need and want more or less Europe when it comes to health. Is there a need to add health to the legal competencies of the EU? Is the EU capable of acting while conforming to its principle of subsidiarity?

The beginning of the crisis demonstrated how intricate European relations can be at the local, national, and continental level. It also demonstrated that the EU has the necessary tools – material and financial – at its disposal, not only to weather the crisis but to build a long-term strategy to prepare for pandemics. However, these tools need to be streamlined into a wider strategy for the future. As we shape the future of European health policy in a post-coronavirus era, reinforcing the EU’s internal and external responsibilities will be paramount. This section looks at how the EU might do that.

Protecting the single market during crises

The single market is arguably the EU’s greatest achievement, and the need to protect it is understood by all EU member states. The pandemic dramatically affected the capacity of the single market to function. Member states closed their borders, cut off tourism and travel within the single market, and commerce slowed down. Most of these activities will be, or already have been, resumed, but the lack of a coordinated response and the sudden and uncoordinated appearance of borders within the single market has damaged confidence that it will continue to function in future crises.

The situation was hardly optimal for the member states either. The manner of the lockdown exacerbated the economic cost of doing business and the lack of coordination between EU member states reduced their ability to get even available financial or healthcare assistance from their European partners.

The EU could help avoid such issues in future through a few preparation and crisis management efforts. These efforts could allow greater protection of the single market and greater assistance from European partners during future health emergencies or other types of crises. These recommendations include:

- Strengthen and expand the EU civil protection mechanism: The EU has a civil protection mechanism to coordinate aid to member states for natural and man-made disasters. But a request to the mechanism from Italy in late February 2020 went unheeded. Overall, the mechanism lacked the material capacity to respond effectively to the covid-19 pandemic. The increasing frequency of disasters of all types should convince decision-makers to increase the capacity of this mechanism. In the context of a pandemic, the civil protection mechanism could develop a European border management scheme to guide states in emergency border closures and lockdowns, inform and coordinate such closures with neighbours, and ensure minimum damage to commerce and the single market. The EU has already published a roadmap to coordinate European efforts to lift restrictions and ensure that the security and safety of European citizens and the single market are protected. Contact tracing could also be harmonised and coordinated to reduce the need to close national borders.

- Create common strategic stocks: Greater common stockpiles of emergency health equipment managed at the European level could introduce efficiencies in spending, mitigate intra-EU competition during crises, and provide an automatic mechanism for demonstrating solidarity. The EU created such a stockpile during the pandemic but it will need to be expanded to prepare for future contingencies.

- Map European healthcare infrastructure and dependencies: By including healthcare in the European Programme for Critical Infrastructure Protection, national and EU authorities could identify the infrastructure critical to pandemic responses and the key dependencies between member states in this area. Such a mapping exercise would allow the authorities to identify vulnerabilities, target funding, and respond to future emergencies more effectively.

- Invest in scenario planning and forecasting: A 2003 WHO resolution requires each country to draft pandemic plans, which is particularly important for the EU given that its principle of free movement exposes it to the “rapid spread of infectious diseases”. For this reason, at least in part, the European Commission created the Health Security Committee after the 2001 anthrax attacks in the US. The ECDC itself was part of the response to SARS in 2003. And when the ebola crisis in 2014-2015 revealed the need for a rapid response team, the European Medical Corps was created. The EU now needs to devise a disease-forecasting instrument – in coordination with the global health system and individual countries, its member states, and third-party countries – making use of the current digitisation of the medical environment.

Promoting standards for healthcare systems

EU health policy aims to support the modernisation of healthcare infrastructure in Europe and improve the efficiency of its health systems. But the stark reality behind this objective is the sheer array of differences between European health systems: whether member states are more centralised or federal, whether these systems are run mostly with state funding or with private sector funding, and finally whether they host potent pharmaceutical and medical device industries. This makes developing a coherent approach to modernising healthcare infrastructure all the more difficult.

The differences in how national health systems function partly explains why and how the covid-19 crisis was handled so differently in the various member states. But they do not explain everything. Indeed, France supposedly has a good healthcare system and a vibrant medical device industry but still found itself in great difficulty when it needed to provide its population with masks, tests, and ventilators. In contrast, Greece, whose health system is considerably weakened by a decade of financial crisis and budgetary restrictions, implemented drastic measures early on in the outbreak – cancelling public events and gatherings and closing school; making rapid investments in ventilators; and recruiting emergency medical personnel. With fewer resources, it managed the problem more effectively.

The EU should seize the current opportunity to support an expanded role in health policy. This will help to strengthen cohesion and socio-economic convergence in the bloc, especially as a few smaller and medium-sized member states are not able to provide a sufficient standard of healthcare. Prior to the covid-19 crisis, states like Croatia, Estonia, Greece, the Republic of Ireland, and others, were already proponents of a wider convergence on health policy. The thinking behind this convergence is that deeper cooperation would enable positive scaling effects in Europe, especially “when it comes to accreditation processes, the benefit assessment of medical devices, the availability of expertise and research, early warning mechanisms, personnel allocation, and price negotiations”.

Now that healthcare is at the top of the global and European agenda, the EU needs to fight against inequalities and for greater socio-economic convergence on the continent. Putting citizens first, it could make patient mobility and healthcare personnel mobility more systematic, to mitigate discrepancies and compensate for shortages, demonstrating its capacity to act. To do so, it will need to map healthcare personnel resources across the bloc with the assistance of individual member states. It will also need to make sure this mapping exercise is renewed regularly and is available to decision-makers. An additional way forward would be to move towards e-health and digitisation, with the data security and privacy caveats mentioned earlier. All of this would also help in countering Russian or Chinese efforts to build soft power in times of acute health crises, because there would be reliable European mechanisms to provide relief.

One of the EU’s strengths is its multiannual financial framework and the role it plays in developing research and innovation. The negotiations for the next framework are currently under way but a great number of research projects have seen the light of day under Horizon 2020. Investment in research and development remains an important tool at the EU’s disposal. Most of the current funding opportunities are concentrated with DG SANTE. However, health projects pertaining to information and communication technology, e-health, and healthcare infrastructure could be funded by other agencies, such as the European Investment Bank or the European Social Fund. Additional sources of funding would lead to more cooperation within the EU, and ultimately more convergence in health systems and standards.

Finally, the nexus between the EU’s internal and external responsibilities on health is growing by the day. It is not sufficient for the EU to defend health standards for its citizens; it also needs to endorse a more important role on the international stage, especially as US withdrawal becomes starker and China increasingly presents the world with a model and standards that differ from ours. It is clear that the EU has a responsibility to coordinate with global health institutions and develop a vision for global health governance. It should pursue a values-based strategy and use its economic might to enshrine higher health standards in multilateral trade and environmental agreements.

Strengthening investment protection for pharmaceuticals, medical equipment, and other key industries

Early on in the covid-19 crisis, Europeans recognised the importance of investment protection instruments, not least for the health sector. The pandemic revealed companies involved in this to be of national health and security concern. It was before the full outbreak of the virus that Trump reportedly tried to acquire CureVac or to secure privileged access to any vaccines it might develop. Europeans reacted to the threat of hostile takeovers with clear guidance from the European Commission on implementing the EU Investment Screening regulation, national investment prohibitions, and adaptations to national investment protection laws. Some countries are now well prepared. But even they can take additional steps to improve protection – and others should quickly adopt the same standards.

The crisis underscored the importance of swiftly implementing the EU investment screening regulation in all member states, but Europeans should also now amend the framework so that it covers more areas. In some countries, the healthcare sector is not clearly covered by investment protection law. It is only mentioned in the margins.

The coronavirus crisis shows that supply chains and the innovation potential of the health sector are of strategic importance. Europeans could add more parts of the health sector to their investment screening procedure, going beyond biotech. At the same time, they must be careful not to infringe excessively on private property rights. Foreign investment is often critical for innovation.

The solution could be to identify more parts of the healthcare sector in which foreign takeovers have to be notified to European governments for their review, while avoiding any over-broadening of prohibition criteria. Currently, because healthcare is barely mentioned, it is not clear whether the notification requirement even applies to non-biotech health companies in many EU countries.

The EU and its member states should also make their investment screening activities more effective. They could do this by imposing tougher penalties on companies for failing to comply with the notification requirement. Only hefty fines for failing to notify the government early on about a possible takeover might ensure that governments can act before it is too late.

Currently, some foreign takeovers can go ahead even though the government is reviewing the case. By the time it intervenes, it is often too late to prevent the transfer of know-how and data. Europeans need to close this important loophole.

Having said all this, governments cannot rely solely on these actions. Geo-economic countermeasures are also important. To effectively protect strategic sectors of European economies, the EU and its member states will need more than just regulatory obstacles to foreign investment. They will also need to demonstrate to other great powers, including China and the US, that geo-economically motivated takeovers will come at a cost – in negotiations with Europe and, where necessary, in the shape of reciprocal punitive measures.

Mapping and protecting supply chains

After the frightening first months of covid-19 supply chain insecurities, the crisis now provides European governments and private sector actors with an opportunity to review and adjust their value chains for greater health sovereignty. In fact, increasing supply security of critical health goods could go hand in hand with a general review of supply chains that aims to increase protection from economic coercion more broadly.

Supply chain reviews are highly complex tasks, and the concrete recommendations emerging from them vary from sector to sector and company to company. Europe also has a general interest in remaining open for trade; and complete independence, even just in the health sector, is unrealistic and undesirable. It is Europe’s openness that assures its innovation capacity and determines whether Europeans will still produce the leading pharmaceuticals of the future. Europe’s review of supply chains should group products according to how critical they could be in a health crisis and how vulnerable they are to economic coercion. The EU could perform this analysis by bracketing products according to four key actions:

- Reshoring: For products where the EU finds full (or quasi-full) supply chain reshoring necessary for health sovereignty.

- Nearshoring: For products whose supply chains should operate in the European periphery such as the Balkans or North Africa.

- Diversification: For products whose (critical) components must have a certain minimum number of diverse suppliers, potentially excluding certain countries or making supply conditional from countries based on certain guarantees.

- Chokepoint vulnerabilities: For products where supply chains either rely on single suppliers (because it is a highly trusted third country) or where they must (because components cannot be found elsewhere).

Procedurally, the supply chain review should start with the status quo ante and analyse the original production calculation of a certain product that determined its supply chain. It should then proceed to re-evaluate the commercial calculation by integrating the risk factors that covid-19 has exposed.

Europeans will also have to distinguish between the tools they want to use for increasing supply chain resilience; whether regulation, incentives, or private sector action (possibly encouraged through dialogue). Wherever possible, it should be private sector actors taking the decisions, because in principle the open market makes Europe an extraordinarily attractive place for investments and assures Europeans’ innovativeness – a key component of European strategic sovereignty. If the EU or European governments feel like they need to review certain supply chains for sovereignty reasons, their first instinct should be to simply keep track of supply chain vulnerabilities, potentially hint at them publicly. Only if these measures are deemed insufficient should the EU consider more drastic interventions in market processes.

The European pharmaceutical industry should take this opportunity to expand to new markets. For example, shifting manufacturing to additional countries and diversifying to limit disruptions and shortages. One option already discussed by experts is for health companies to be “obliged through a kind of quota to include suppliers in their tenders who obtain their active ingredients from the EU instead of from abroad.”

This could provide a solution to the problem of “traceability”. It has proven complex to implement quality control when your production base is extremely far away, in a country with different health standards and sometimes a different political and value system.

In 2018, the EMA and the US Food and Drug Administration warned of the dangers posed to the global pharmaceutical supply chain by China’s pharmaceutical industry. A big difference with India, which has also known its fair share of scandals, is the limited oversight that is accorded to external observers in China. India is already a major partner for Europe in supplying medicine but also developing research. India has joined Europe in the fight for multilateralism and this could expand European engagement in the Indo-Pacific. In light of increasing China-US tensions, Europe and like-minded Asian countries could find a common path forward together.

Finally, none of these measures on supply chain resilience can replace well-equipped strategic stockpiles within the EU that are able to satisfy needs in times of acute crisis.

Promoting and funding medical research and development

The CureVac and Sanofi cases discussed above both point to insufficient funding for research and development. The EU’s Horizon 2020 programme is already impressive in this regard and national governments have also added significant amounts of funding, but it may not be enough. In April, Chancellor Angela Merkel and President Emmanuel Macron launched an $8 billion fundraising initiative for a vaccine with equal access for everyone. But the US and China managed to outpower the EU’s emergency funding drive. Europeans should consider putting in place a mechanism that, upon quick approval, unlocks great amounts of risk investment funds for health R&D similar to the Chinese and American equivalents for times of acute crisis.

Coordinating European efforts in multilateral institutions

The year 2021 could be Europe’s moment to initiate some important reforms in the multilateral system, particularly in healthcare policy. The EU’s successful May 2020 resolution at the World Health Assembly, calling for access to safe testing, treatment, and palliative care for covid-19 patients – particularly elderly people – was ultimately supported by 144 states. This shows that Europeans, when united and strategic, can catalyse international action and bridge geopolitical divides. In 2021, the United Kingdom and Italy will take over the presidencies of the G7 and G20 respectively. Working with the UK, the EU can profit from those positions to promote multilateralism on three levels:

- Convene global initiatives: Europeans can promote ad hoc global initiatives, such as the Access to Covid-19 Tools pledge conference organised by the European Commission in May 2020 and positioning itself as the convening platform for state and non-state actors, such as the WHO, the G7, G20, foundations, and the pharmaceutical industry. In the future, one communication channel could take the form of a taskforce composed of the European External Action Service and diplomatic advisers to EU heads of state and governments. In addition to this convening platform, the ECDC’s role and responsibilities should be expanded for it to become the arena where EU and non-EU countries communicate regularly and organise simulation exercises.

- Unblock multilateral institutions: In existing multilateral institutions, the EU needs to avoid getting dragged into the China-US confrontation as much as possible. The EU needs to encourage constructive participation in the WHO, with the appropriate financial conditions and coordination support to bolster international health governance despite the US withdrawal. The current investigation into the origins of the virus is vital and should result in a ‘lessons learned’ process that can help prepare for the next pandemic. The EU could also use this opportunity to demonstrate that it represents a third way beyond a US increasingly withdrawn from global health and development policy, and an increasingly assertive China.

- Reform the global system for responding to health emergencies: The EU should push for reforms and reinforcements for the current global health system. It should insist on the implementation of verification mechanisms and improvements to early warning and response capabilities. It should bolster coordination with funders from international financial institutions, multilateral funds, and member states. It should also become the rallying point for cooperation on research and development, as it is best placed to cover the wide range of actors in the field of global health.

A daunting agenda

This long litany of measures certainly sets a daunting agenda for EU institutions and national governments. But it also sets a clear roadmap for how the EU and its member states, working together, have the capacity to protect European health sovereignty, despite the difficult geopolitical context. And they need to do so because the richly diverse lives of Europeans across the continent are stuck on hold. Building effective health sovereignty will boost resilience and get the European economy and society firing on all cylinders once again.

Appendix: Views from the capitals

This appendix looks at the perspective on health sovereignty and the expectations of the European and multilateral levels from six key EU capitals (Berlin, Madrid, Paris, Rome, Sofia, and Warsaw).

Berlin (Jana Puglierin)

Compared with other European countries, Germany has so far weathered the coronavirus crisis well. Contrary to initial concerns, the German healthcare system was never overwhelmed. The number of intensive care beds and ventilators proved sufficient. An existing decentralised and widespread network of nearly 200 private and public laboratories allowed Germany to access extensive, rapid, and early testing. This is mainly because the German health system is not centrally organised but run by municipality and rural district administrations.

Germany was also lucky, because the average age of those who were infected early was lower than in many other countries; this kept hospitalisation and death rates low. Because of this, Germany gained time and used it to roll out preventative measures, expand intensive care capacities, and flatten the curve of new infections. Even though there was never a complete lockdown, people observed the government’s social distancing guidelines. There was a large consensus in Germany in support of the measures of the federal government, which were supported by almost all parties except the Alternative for Germany.

Despite good crisis management, the effects of the pandemic have highlighted previously identified vulnerabilities in the German healthcare system. The dependence on global supply chains for medicines and medical equipment, especially from China and India, has reignited domestic debates about the necessity of bringing production back to the EU or building up bigger storage facilities in Europe so future supply shortages can be avoided. The unavailability and lack of data sharing for research purposes in the health sector are other key vulnerabilities.

For many years, Germany has been a very reluctant actor in European health policy, often citing the legal barrier imposed by Art. 168(7) of the TFEU. The complex structure of Germany’s self-governance in healthcare, as well as the diverse interests of its national medical associations, health insurers, businesses, and other stakeholders, make it difficult for the country to engage in discussions about EU-level health policy or adopt a unified position. In addition, Germany fears a decline in its own national quality standards through further Europeanisation.

However, even before the coronavirus crisis the country had opened up to more health policy questions on a European level, concentrating on cross-border issues such as infectious diseases, patient mobility, and the supply of medicines. Earlier this year, health minister Jens Spahn announced his intention to discuss concrete measures on how to prevent supply shortages for drugs in the EU, secure supply chains, and avoid dependencies in drug manufacturing, during the German presidency of the European Council. It has become a German priority to strengthen the global competitiveness of the European pharmaceutical sector and to secure access to innovative drugs for European citizens. Another priority is digitisation, big data, and AI in the health sector, to ensure the EU’s competitiveness, but also so that European citizens can remain in control of their own health data.

The pandemic has further strengthened this shift toward more active engagement. A joint covid-19 recovery proposal put forward by President Emmanuel Macron and Chancellor Angela Merkel on 18 May 2020 called for a new European approach to health crises. To obtain greater European health sovereignty, the proposal argues for a strategically positioned European healthcare industry to take back control of medicine and vaccine production in Europe and to reduce the EU’s dependency on foreign actors.

On the multilateral level, Germany has become a very committed actor in global health by increasing its political voice through its G7 and G20 presidencies and through enhanced support for multilateral and bilateral partnerships. The country sees itself as a strong supporter of multilateral responses to the covid-19 pandemic in a wide range of UN and other political bodies, such as the Alliance for Multilateralism, and as a strong supporter of the WHO. This is also reflected in the fact that Germany is currently the fourth largest contributor to the WHO in terms of assessed contributions.

Germany has advocated a bigger role for the EU in global health – one that would match the EU’s major financial contributions. It sees the EU as crucial actor in reforming the global health security landscape. From a German perspective the EU too often falls short of its capabilities because of structural weaknesses in intra-European coordination. It maintains that there is a distinct need to better coordinate and streamline European voices in international organisations like the WHO.

Madrid (Jose Ignacio Torreblanca)

The Spanish government’s Centre for the Coordination of Health Emergencies failed to heed the signals coming from the WHO, China, the EU Health Emergency Centre, and Italy. This exposed significant weaknesses in Spain’s health security apparatus. Like many other European countries, Spain had not been affected by SARS or MERS and so had not incorporated any ‘lessons learned’ from either experience. Therefore, it was too slow to stop international flights, adopt border restrictions, or impose social distancing and, where necessary, confinement.

Worse yet, in mid-February, instead of preparing its health system and care homes for the pandemic, it sent protective gear to China. All of this meant that its health system was dramatically unprepared to cope with the peak of the virus. Not only were there insufficient emergency rooms, intensive care units, or ventilators available, but the authorities were markedly late in protecting health workers with adequate PPE.

The consequences of this lack of foresight and preparedness have been felt across a large number of areas. Spain has suffered:

- one of the world’s highest death rates per capita, including in care homes, which were not prepared or quarantined in time;

- one of the largest health worker infection rates in the world, with almost one in every four workers infected; and,

- one of the most intensive and extensive lockdowns in the world, with some of the most severe economic and social repercussions anticipated in Europe in terms of GDP and job losses.

An additional element aggravating the crisis has been the decentralised nature of the Spanish health system. With health competencies fully in the hands of regional governments, the central government’s attempts to establish a single crisis and command centre were plagued by difficulties. These difficulties were both political, with regional governments resisting Madrid’s power grab, but also practical, because the National Health Ministry was far too weak and inexperienced in health management to cope with the crisis effectively. Huge difficulties were encountered producing unified statistics, buying protective material, distributing hospital beds or doctors and nurses across regions, coordinating testing, and agreeing on confinement and de-confinement measures. This resulted in the acquisition of defective material from unscrupulous providers and intermediaries in China and elsewhere, and a lag in acquiring PPE for health workers.

To make matters worse, political polarisation, which was already marked due to the anti-establishment agenda of Podemos, Vox, and the Catalan secessionists, has increased. The government is weak and divided. Regional governments criticise it for not listening and for marginalising them, emergency decrees are increasingly questioned in parliament, and citizens in Madrid and elsewhere have resorted to protesting in the streets against the confinement measures.

Among the positive reactions to the crisis is the setting up of a series of government expert groups to look at the consequences of the crisis and extract ‘lessons learned’ to better prepare for the next one. Two elements of this process stand out. Firstly, the discussion on strategic sovereignty has received new impetus. Concepts such as reshoring, nearshoring, and health sovereignty are all on the table for discussion. The understanding is that Spain needs to build strategic capacity for crisis situations which includes not only better foresight and prevention, but a new approach to strategic reserves, stockpiling, value chains, transport and distribution, research, statistics and data, and private-public partnerships.

There is a very important European dimension to this reflective exercise. The Spanish idea is to exploit interdependencies within the EU to increase resilience, avoiding autarky and isolation. So, the reflection is about strengthening Spain’s capacities but in a European context and in a coordinated way.

The second element is the multilateral dimension. Spain’s foreign minister, Arancha González Laya, is quite actively promoting a strengthening of the multilateral health institutions and capacities, both in terms of beefing up WHO contributions and financing vaccine research. But she is also working to pre-emptively ensure vaccines are globally available once they are finalised.

Spanish policymakers also harbour some fears worth mentioning. One is the fear that the suspension of state aid rules will end up damaging the Spanish economy because it is less able than Germany to subsidise sectors in crisis, including in automotive, tourism, airline, and pharmaceutical industries. Another important matter is the need to avoid hard macro-economic conditionality when accessing support from the European Stability Mechanism or EU budget to assist the health sector, but not so much over long-term restructuring programmes. Spain does not seem to be as worried as other countries about China’s assertiveness. Even if the government is in favour of reshoring and taking a deep look at the vulnerability of supply chains, it wants to avoid antagonising China. For other issues, such as the development of health apps, Spain would welcome a greater EU role.

Paris (Tara Varma)

In France, public health is considered to be the state’s responsibility and is a highly politicised topic where the left-right divide is strong. The public deeply values the French healthcare system, but also fears losing it. In a 2016 poll, an overwhelming 84 per cent of respondents indicated that they thought sécurité sociale was good and better than in other countries, while 79 per cent think that it is in great danger.

France was extremely slow to react to the threat of the coronavirus. It found itself, according to the New York Times, “nearly defenceless”, even though experts had long been warning that a pandemic was possible. Following recommendations by scientists and experts at the beginning of the 2000s, France invested massively in PPE and vaccine development. In 2006, according to the WHO, France had stockpiled 600 million masks – half of the world’s annual production – making it one of the best prepared countries in the world to face a pandemic. But the fallout of overzealous H1N1 crisis management in 2009, in which the government was accused of overreacting by acquiring 94 million vaccines, led to a loss of government credibility. Being overly cautious became more damaging to decision-makers than not being prepared enough, especially during a time of budget orthodoxy.

The subsequent change in doctrine led the government to devolve authority to local authorities, hospitals, and regional health agencies, with the government responsible only for assembling strategic stocks. The vast majority of the five-year-valid FFP2 masks had become obsolete and state stocks depleted. The cost of being prepared for a hypothetical pandemic was simply too high. France therefore found itself extremely vulnerable in its time of need. With their backs to the wall, the French population – tougher on its decision-makers than most Europeans – was horrified to learn the extent to which France was dependent on the global supply chain to ensure its citizens’ health, particularly on China for masks and India for medicines.

The comparison with Germany – where there seemed to be no shortage of tests and ventilators – certainly contributed to citizens’ negative views of the French response. A poll from April 2020 revealed that 62 per cent of respondents were “unsatisfied” with their government’s actions.

True to form, Macron was relentless in his push for more European strategic sovereignty and European strategic autonomy. In a speech on 13 April, the president announced that the end of the lockdown in France – new developments notwithstanding – would occur on 11 May. He also declared that the only long-term option for Europeans was to ensure their health – and thus strategic – autonomy in terms of medical equipment and personnel. Strategic autonomy regarding health supplies will require better European coordination to ensure improved control and decision-making in resourcing within Europe and beyond Asia. Macron has also been among those attempting to ensure maximum European financial support is provided to the hardest-hit member states.

The French president is also pursuing efforts to champion the multilateral system. With American leadership absent, Macron put the same level of effort into organising a pledging conference under the aegis of the EU and the WHO where €7.4 billion was collected for research to find a vaccine for covid-19. France itself pledged €500m. He has also pushed for the vaccine to be considered a common global good, meaning that access to it should be made available to all.

Rome (Arturo Varvelli)

By the end of February, covid-19 had hit Italy. It was the first European country to detect cases of the coronavirus on its territory. Although the Italian government declared a state of emergency fairly early on, at the end of January, its national health service still found itself unprepared for the huge number of patients with confirmed cases.

The Italian government was not only the first to be hit by the virus, but also the first to order a lockdown. At the beginning of the outbreak, the Italian Health Ministry recommended that all patients with coronavirus-like symptoms should be tested. But, in the event, tests were given to patients that evidently required hospitalisation, while thousands of people with less serious symptoms were not tested. Italy simply did not have enough tests for everyone. This was acknowledged in a directive from the Health Ministry that claimed that a new strategy was needed due to “limited test availability”.

The lack of tests obscured the actual number of infected people, aggravating the spread of the disease. Since regional governments are responsible for healthcare in Italy, political wrangling between the central government in Rome and local authorities began over which entity exactly is responsible for health supplies. Only a few regions, such as the eastern region of Veneto, were able to obtain much-needed healthcare supplies because they happened to already have them in storage. The controversies between Rome and some northern regions, such as Lombardy, which is governed by Lega Nord, have been fierce.

Italy does not produce various key items, such as masks and ventilation systems, in its own territory. This caused a supply vulnerability. The lack of PPE caused more medical staff to become infected and end up quarantined. The knock-on effect of this was a chronic shortage of healthcare workers, just when they were needed most.

Italy asked other EU countries to help supply face masks in February and received no response for weeks. At the end of May, the commissioner for the covid emergency, Domenico Arcuri, in an appearance before the Social Affairs Committee in parliament, declared that by September there will be only ‘Italian’ surgical masks on the market.

The help that Russia and China sent gained attention because of the slow reaction by EU partners, creating the perception that the EU had abandoned Italy. EU aid did eventually arrive, but the lack of a coordinated policy and an effective and comprehensive communications strategy represented another shortcoming in Europe’s response. Chinese messaging, by contrast, has been relentless, and this caused great misperceptions among the public. According to a poll released in April, for example, over 50 per cent of Italians consider China a friend, even though European aid was more substantial.

Both the prime minister, Giuseppe Conte, and the foreign minister, Luigi Di Maio, engaged in a race to obtain medical materials from abroad, sometimes underestimating the political implications of receiving support from some countries in the long term. The Five Star Movement has continued to look to China for help in this sector, while the Democratic Party has remained more focused on European solutions. Even though the EU decided to use the European Stability Mechanism as a health rescue fund, Rome does not want to draw on it. Many Italians still fear that borrowing from the EU would come with tough conditions attached.

Sofia (Vessela Tcherneva)

The Bulgarian health system is underfunded and understaffed. It is underfunded because the system remains very inefficient and understaffed, and because many doctors and nurses emigrate to western Europe.

Throughout the initial two months of the covid-19 crisis, however, there were no shortages of medicine. Masks and protective gear were unavailable in the first couple of weeks, but local production lines were quickly readjusted. Currently Bulgaria is exporting protective gear to other member states. There were not enough ventilators in Bulgaria to meet needs, but the reason the country opted for early and stringent measures, including a (partial) lockdown, was due to worries that the lack of qualified medical help would be exposed and cause the whole system to collapse. Bulgaria now has the third lowest number of deaths from covid-19 in the EU, after Latvia and Slovakia.

Society largely rallied behind the government, with 70 per cent endorsing the steps taken. The popularity rating for the prime minister, Boyko Borissov, increased from 30 per cent in December to 40 per cent in May. A small group protesting against the lockdown has become more vocal lately, but they remain marginal and focused on conspiracy theories, repeating many of the tropes of Russian anti-Western propaganda, evangelical pro-Trump narratives, and fears of globalisation. Illustrative claims include stories that the virus has been made up in order to impose 5G on the population, distract from an American military plot in the Balkans, and increase the ratings of the government, the last of which has, incidentally, come true.

On the larger question of the system’s vulnerabilities, however, there is a clear divide regarding the financing and reform of the health sector. The question is whether the additional money for health should come through the national budget or via private insurance companies. This effort could be part of a reform that would entail closing down some of the small-town hospitals that are untenable and proved of little use during the covid-19 crisis.

Although the need for health sector reform has been clear since the late 1990s, not much has happened on this front because of the high social and political price associated with it. Should there be a set of EU standards for the healthcare sector, the appetite for reforms would increase. This would raise the level of healthcare and keep more Bulgarian doctors and nurses in the system.

European healthcare standards need to be imposed carefully, to account for the national context in Bulgaria, and to include the financing of education, establishing the necessary number of hospitals and doctors per capita by specialisation. On the other hand, if a coordinated European level of health standards became a part of the European acquis, it would bring real change to the life of citizens. This would matter more to Bulgarians than talk of trillion-euro recovery funds.

The coronavirus crisis has demonstrated an EU-wide lack of common protocols for closing and opening borders in the case of pandemic and lack of standards for critical stocks. In such areas, the Bulgarian government will ask the European Commission for better legislative infrastructure. It will also look for ways of ensuring that any vaccine is produced in Europe. Sharing information on health risks, reducing the price of medicines, and sharing stocks of critical goods such as drugs and masks will also be on the government’s wish list.

Warsaw (Piotr Buras)

Poland’s response to the crisis was swift. The first case in Poland was diagnosed at the beginning of March, and the country went into full lockdown in the second half of the month. Learning from the mistakes of European countries that experienced the virus earlier, the Polish government promptly implemented strict measures.

This reaction was necessary to prevent hospitals from being overwhelmed, and prompted a debate concerning healthcare expenditure. According to Eurostat, Poland spends only 6.5 per cent of its GDP on healthcare, while the average expenditure in the EU is around 10 per cent. This problem was formerly a cause for numerous protests and strikes organised by Polish medical personnel who criticised the government for launching expensive social programmes while failing to invest in public health. However, the protests did not result in any major reforms. Now, with the presidential election around the corner, the problem of insufficient spending on public health is a key issue in Polish politics.