Gaza’s fragile calm: The search for lasting stability

Summary

This publication is also available in French here

- Intensive UN and Egyptian efforts to mediate between Israel and Hamas have staved off an immediate return to conflict in Gaza. This is a quick fix that buys badly needed time to find a longer-term solution.

- Gaza’s problems are fundamentally political, resulting from restrictions imposed by Israel, Egypt, and the Palestinian Authority, as well as internal Palestinian divisions.

- The EU should lead collective action to challenge the political obstacles to lasting stability, developing a more realistic political map that can guide its technical and financial support for Gaza.

- The EU needs to promote moderating policies that can shift Israel, the PA, and Hamas away from putting their rivalries with one another before all else.

- The EU should also see Gaza as a springboard for Palestinian reunification and sovereignty-building.

Introduction

War threatens to engulf Gaza’s fragile calm. In each of the three recent conflicts that have shaken the Gaza Strip, fighting between Palestinian factions and Israeli forces killed hundreds of Palestinian civilians, destroyed homes and infrastructure, and deepened the already acute socioeconomic and humanitarian crisis there. Another war in the Gaza Strip would not only endanger Gazans but would also threaten Israeli civilians as far away as Tel Aviv, who have been repeatedly exposed to rocket fire. As each cycle of escalation and de-escalation brings not a return to the status quo but greater suffering, the current period of relative calm – one of several in the last decade – appears to be unsustainable.

There are several imminent threats to stability. One is rising internal pressure on both the Israeli government and Hamas to achieve a political victory. As a start, Hamas wants meaningful economic and financial relief for Gazans, who experience growing hardship under the severe restrictions imposed by Israel and (to a lesser extent) Egypt on their movements and access to basic goods. Israel wants a return to hudna (calm) on its border. And there are hardline elements on both sides who advocate a tougher stance, limiting room for compromise. Unless they reach an agreement that meets their demands, Israel and Hamas – Gaza’s de facto rulers – may come to see renewed conflict as politically expedient: the only means of breaking the deadlock to improve their bargaining positions with each other. It is also possible that a series of miscalculations will drag the sides into war.

Another threat comes from a lack of reconciliation between Palestinian factions. This can be seen in Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas’s recent decision to tighten the stranglehold on Gaza. The decision has deepened the political, economic, and social divide between Gaza and the West Bank, and stoked Palestinian anger against the PA. Internal Palestinian feuding also has negative implications for the Palestinian national project, and for what is left of hopes for a two-state solution.

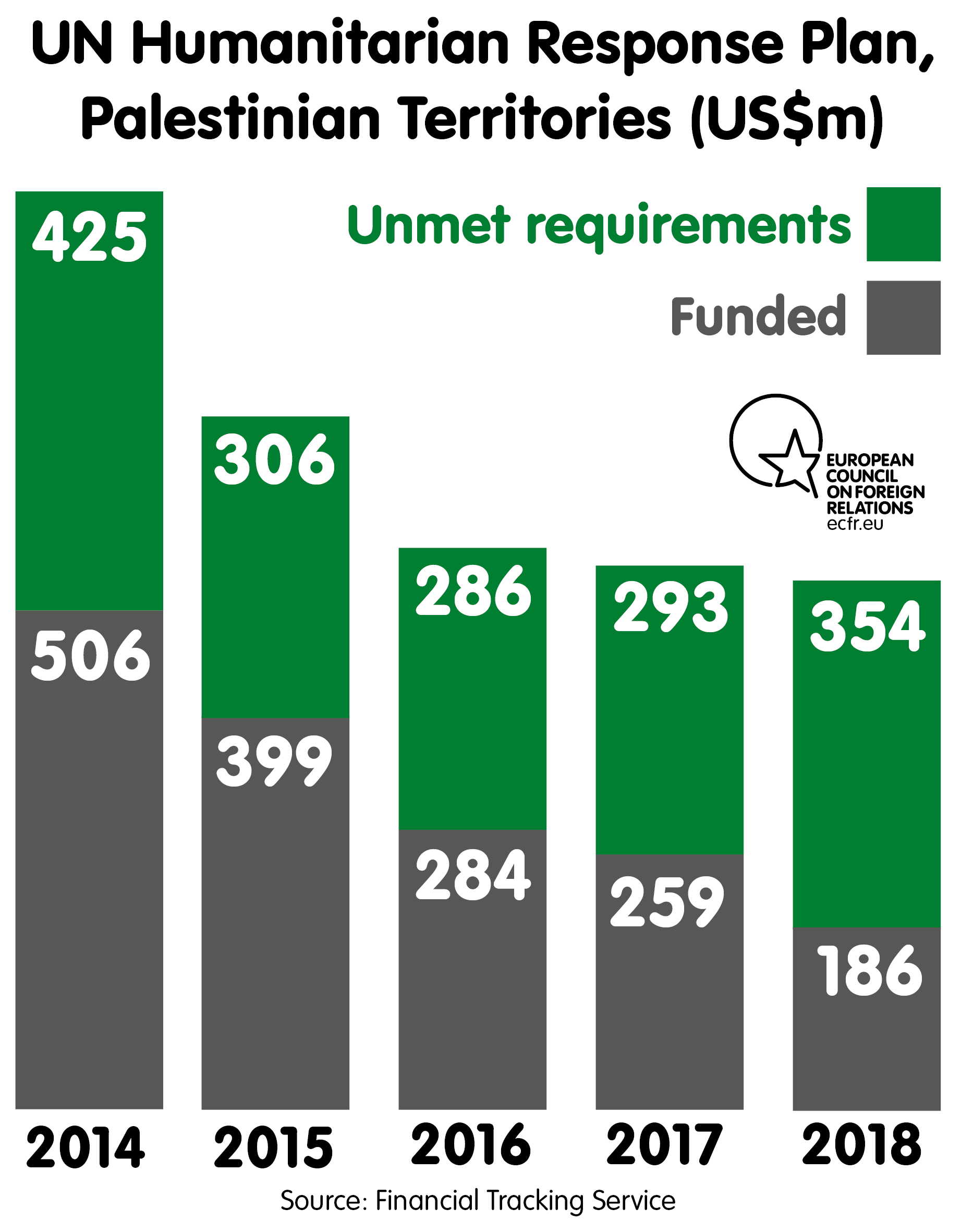

The US government’s recent actions pose an additional threat. The White House’s decision to reduce its financial support for United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) operations in Gaza has caused a further decline in living conditions there and threatened increased instability.

Intensive Egyptian and UN efforts to mediate between Israel and Hamas have staved off conflict for now, buying some badly needed time in the search for a sustainable political solution. That the sides have resisted the slide towards renewed conflict despite a series of severe flare-ups in violence shows that they still prefer negotiations. But it is unclear whether short-term progress in stabilising Gaza will translate into a longer-term agreement between them, and whether such a deal would develop into a significant political track for addressing the root causes of Gazans’ predicament.

The opportunity to achieve these aims should not be wasted. Although it remains committed to funding humanitarian and development projects in Gaza, the European Union has so far lacked the strategic vision and political engagement needed to gain real leverage over key actors in the area or make progress on the ground. But this could change. By adopting a more realistic policy on Hamas and taking on an enhanced political role that focuses on ending Israel’s and the PA’s punitive sanctions on Gaza, the EU could help prevent another war.

A deepening socioeconomic crisis

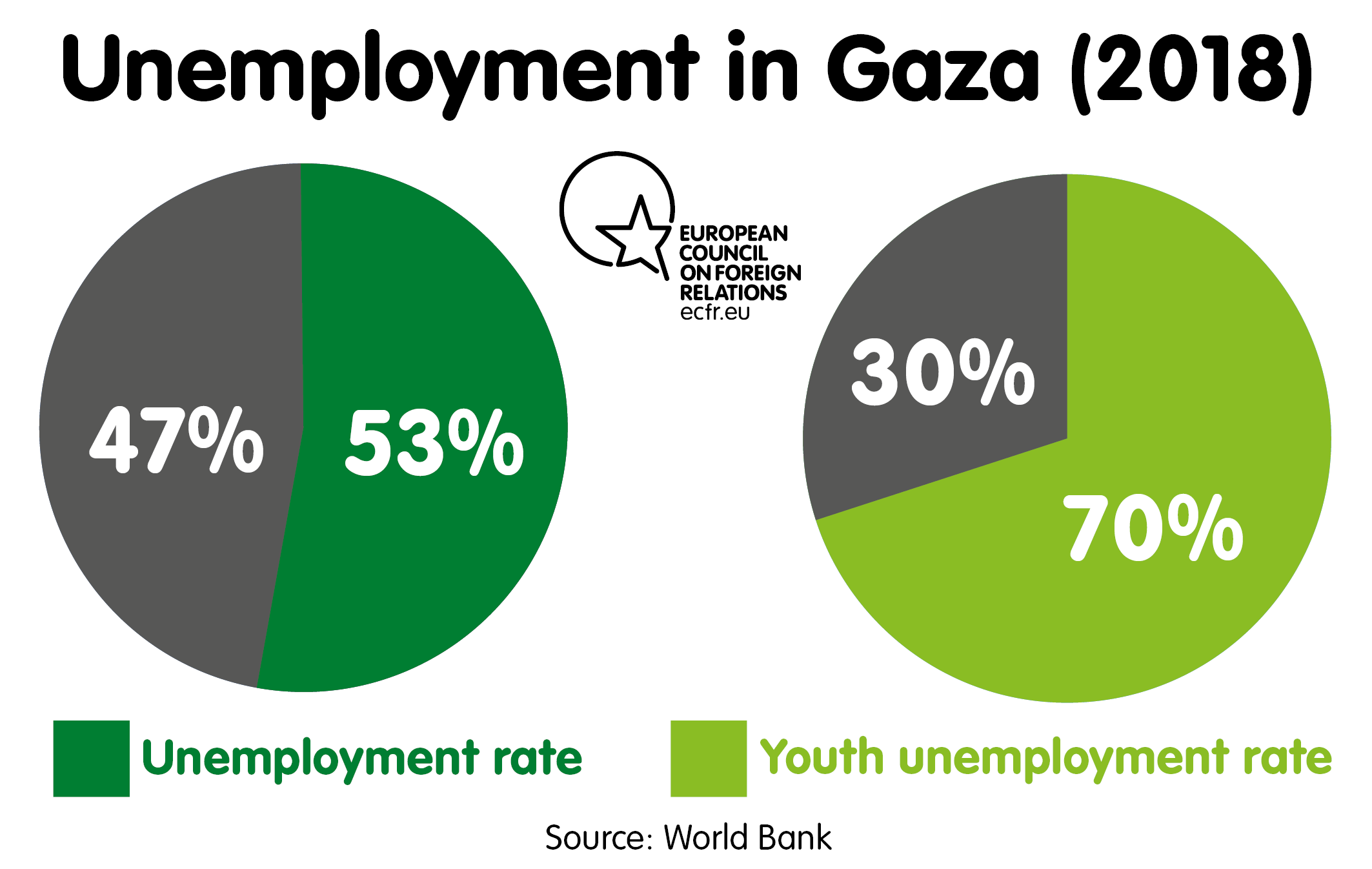

The UN estimates that Gaza, one of the most densely populated areas on earth, will be uninhabitable by 2020 – meaning that its infrastructure, food security, and urban environment will have degraded to the point that Gazans are forced to endure unbearable living conditions. Arguably, it already is. After more than a decade of sanctions and conflict, its society and once-prosperous economy are collapsing. The area has an unemployment rate of 53 percent (more than 70 percent among young people), while 53 percent of the population live in poverty. In addition, a large number of Gazans suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, and 300,000 children there are in need of psycho-social support. Suicide rates have also increased.

Perhaps the most pressing issue facing Gaza’s 1.9m inhabitants – and, by extension, Hamas – is a serious deficiency in electricity services. Due to fuel shortages, the Gaza Power Plant produces only between eight and eleven hours of electricity per day. Although this is an increase from the previous low of four hours per day thanks to UN efforts, a severe lack of electricity still affects daily life for the majority of Palestinians in Gaza who are unable to afford private generators or solar panels. A lack of electricity has also made it difficult to operate lifesaving equipment in Gaza’s hospitals and compromised water treatment facilities. As a result, 97 percent of the Gaza Strip’s water is contaminated.

According to a recent World Bank report, the United States’ decision to withhold around €260m in funding from the UNRWA has led to job losses and the curtailment of construction projects in Gaza. Coupled with its termination of US Agency for International Development (USAID) projects worth approximately $45 million , this has increased pressure on residents – 79 percent of whom depend on foreign aid – and provoked local protests and threats against the UNRWA.

While the PA cut the salaries of its civil servants in Gaza, Washington has further reduced Gazans’ income and employment opportunities. Through its funding cuts, the US has also limited international non-governmental organisations’ capacity to deliver food and financial assistance to the most impoverished Gazan households.

Uncertain future

The last six months have seen the greatest instability and violence in Gaza since the 2014 war. Although Hamas continues to prioritise mediation and mass mobilisation, the group’s leader in Gaza, Yahia Sinwar, has made clear that this could change: “what we do not get through negotiations, we will take by force and confrontations.” There is a degree of posturing and signalling towards Israel in this statement, but one should take his words seriously nonetheless.

Meanwhile, the Israeli government is under increasing political pressure to achieve calm in Gaza one way or another. This pressure will only increase in the run-up to anticipated elections by early 2019.

Even if neither side chooses to return to war, Israel’s militarised response to popular mobilisations along Gaza’s border has increased the likelihood of accidental conflict. “Spoilers” in Gaza – including hardline Salafi jihadists – could also drag both sides into a new cycle of violence. So could rocket attacks intended to improve Hamas’s bargaining position.

Repeated exchanges of fire between Palestinian groups and Israeli forces in recent months have shown how quickly and easily escalation can occur – as well as the importance of UN and Egyptian mediation and deconfliction efforts. But if war is not the answer, what is the solution?

Israel’s periodic attempts to weaken Palestinian militant groups and collectively punish Gazans (a practice it calls “mowing the lawn”) have not, and will not, create durable calm. Israel does not want to reassert the kind of direct military control over Gaza that it exercised before its 2005 withdrawal – nor to remove Hamas from the area, given the lack of a viable alternative to the group. Indeed, the current equilibrium of belligerence – whereby both sides use force to negotiate short-term gains and avoid making political or ideological concessions – has served Israel well.

Should another conflict break out, the “least worst” scenario for Israel would be a short, sharp confrontation similar to the 2012 war, in which the Israeli military mostly restricted its operations to aerial bombardments. Regardless of the level of violence, once the smoke cleared, the sides would find themselves again searching for an uneasy truce. This has been the pattern in each war – but it is not sustainable given the deterioration of living conditions in Gaza.

The depth of Gaza’s crisis means that another conflict will have especially severe socioeconomic consequences. However, there are many unanswered questions about how Hamas would respond following another punishing war. Would it continue administering and providing security in return for what have until now proven to be mostly empty promises of loosened restrictions on development assistance? Or might it decide to go underground or even chart a more radical course? In such scenarios, Israel might have to reassert direct military control over almost 2m Gazans or bring back the PA.

The psychological strain of another war on Gazan society should not be dismissed. What happens when Gazans’ remaining hope evaporates? And, in the long term, what happens when a new generation of Gazans – many of whom have lived through three wars and have never known life outside a Gaza that has no electricity for most of the day – assumes power? These issues will be amplified if Gaza’s population doubles to almost 4m by 2050, as projected.

Israel’s policy of closure and separation

Gaza’s problems are primarily the product of Israeli restrictions and closures, and its policy of separating Gaza from the West Bank. Israel has reneged on its commitments to allow for Gaza’s partial opening under the 2014 ceasefire arrangement that ended the last war. This was supposed to provide “calm for calm”: an end to violence in return for easing humanitarian and economic conditions by increasing the movement of people and goods across Gaza’s borders, and for expanding the area’s fishing zone to between 6 and 12 nautical miles from the coast. Several infrastructure projects were also mooted.

Israel’s policies of closure and separation date back to the mid-1990s. But the severity of the policies has grown since Hamas’s victory in the 2006 legislative elections and its ouster of rival Fatah forces in June 2007. Since then, Israel has periodically eased (but never fully removed) restrictions, usually under ceasefire deals that followed various rounds of fighting. According to a classified US diplomatic cable from 2008 that Wikileaks obtained, these measures aim to “keep the Gazan economy on the brink of collapse without quite pushing it over the edge”.

Today, Israel continues to place severe limitations on Gazan imports and exports, constrain the passage of people through the Erez Crossing, restrict Gaza fishing zones, and limit the area’s imports of fuel and construction material. As part of this, Israel has introduced a highly arbitrary, confusing, and changeable list of prohibited “dual use” items. The temporary Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism established in 2014 has allowed some previously prohibited items to enter the area, but new constraints on imports have reduced its effectiveness.

Israel’s measures violate its commitments under the 1995 Oslo II Accords to ensure free and safe passage between Gaza and the West Bank. And they contravene the country’s duty to ensure the well-being of Gazans under international humanitarian law, as it is the occupying power in Gaza. These are all issues that Fatou Bensouda, the International Criminal Court’s chief prosecutor, is considering in her preliminary examination of the situation there.

Israel’s uneasy relationship with Hamas

Israel has three main aims for the Gaza Strip. The first is to separate Gaza from the West Bank, thereby undermining the Palestinian national project. The second is to contain and weaken Hamas, but not to the extent that the group can no longer – as Israel sees it – police ceasefires and provide a degree of stability between rounds of fighting. The third is to maintain calm by collectively punishing or rewarding Gazans according to the security situation (by tightening or loosening restrictions on them). As Israeli Defence Minister Avigdor Lieberman recently admitted, Gaza’s residents have something to gain when Israeli citizens enjoy calm and security, and something to lose when this calm is broken. These last two, complementary objectives are part of Israel’s formula for achieving “calm for calm”.

Devoid of any real ideological or strategic value for Israel (unlike the West Bank), Gaza has long been a policy headache for Israeli leaders. Politicians such as Lieberman regularly speak of their desire for regime change in Gaza – whether through direct military action or the instigation of a popular uprising.

But, despite all this, and despite fighting several wars there, the absence of a strong ideological drive towards Gaza has, at times, opened limited space for a more pragmatic Israeli approach. Israel generally sees a Hamas-controlled Gaza as the best realistic scenario because it believes the PA cannot replace the group (and, from a political and security perspective, may not want it to do so). This also provides an “address” Israel can hold responsible for the security situation in the Strip.

In practice, Israel has developed an uneasy working relationship with Hamas. Israeli officials have demonstrated increasing willingness to reach understandings and arrangements with the group, albeit it through mediation. Israeli officials readily state that Hamas has policed ceasefires effectively, stopped rocket fire into Israel, and reined in more hardline factions – when it chooses to do so.[1]

Israeli officials also acknowledge that Hamas’s ability and willingness to preserve calm is directly linked to socioeconomic conditions in Gaza.[2] However, Israel’s political leaders have not always shared this view. And, indeed, in a report on military and political decision-making during the 2014 war, Israel’s state comptroller criticised the government for failing to deal with the reality that the humanitarian crisis in Gaza destabilises the area.

Egypt's Sinai problem

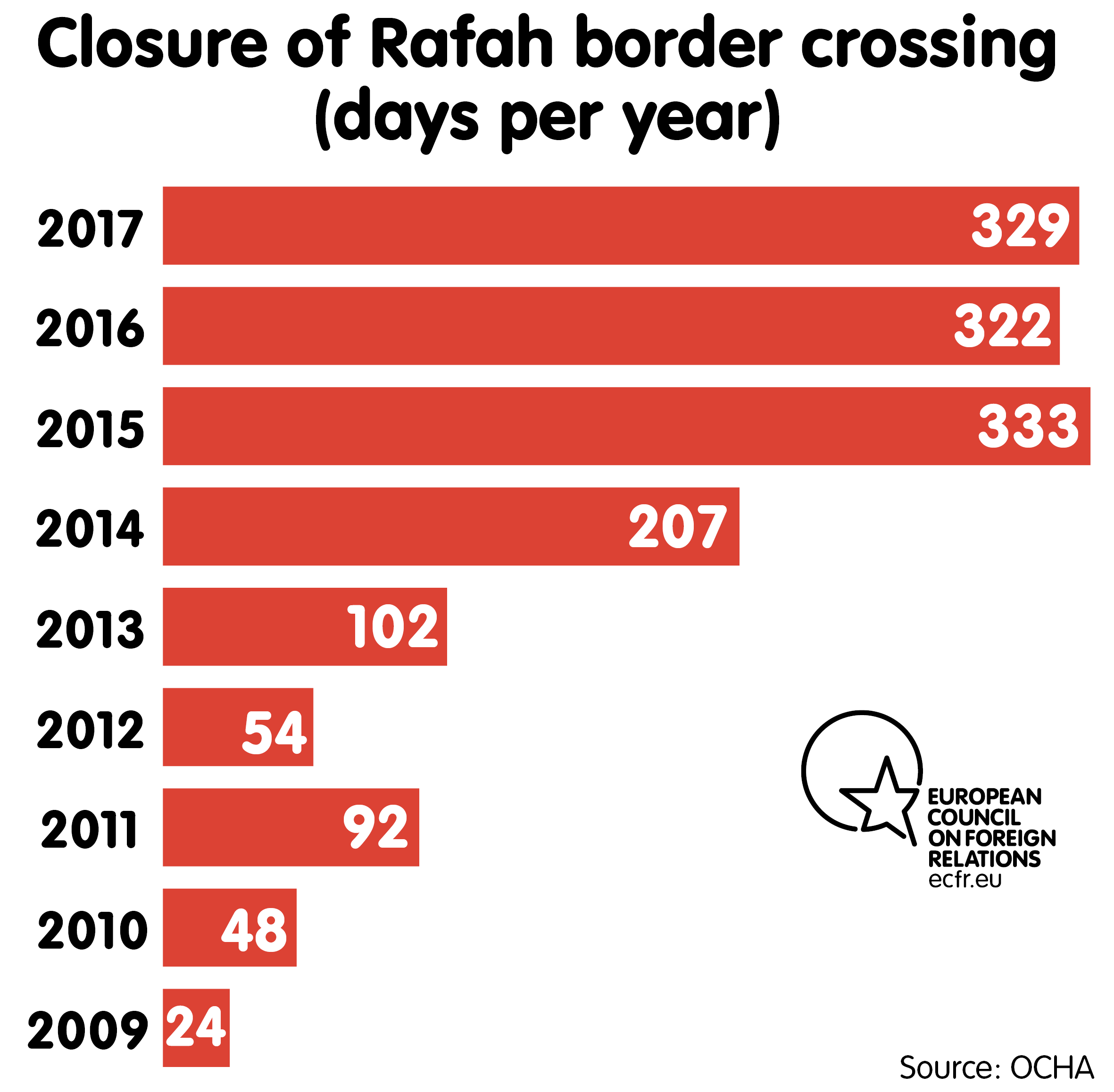

Egypt bears at least some responsibility for the current situation in Gaza. During the past decade, Egypt has opened its Rafah border crossing intermittently – often only to address humanitarian emergencies. Cairo relaxed its restrictions somewhat in the aftermath of the 2009 war and during the 2012-2013 presidency of Mohammed Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood – Hamas’s parent organisation. However, the rise to power of his successor, General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, in 2013 occasioned a more hardline approach towards Hamas and the Gaza border.

In 2015 the Egyptian military stepped up its efforts to destroy the 1,000 or so smuggling tunnels dotted along its Sinai border at Rafah. Aside from providing a source of tax revenue for Hamas, these tunnels were an important economic lifeline for Gazans, who depended on them to obtain goods such as milk, cement, stationery, clothes, fuel, and even cars.

Cairo primarily views Gaza (and, by extension, Hamas) through the prism of Egyptian internal security concerns. These worries stem from its fight against the Muslim Brotherhood, as well as Egyptian Salafi jihadist groups that threaten stability in Sinai. Some of these organisations have ties to Palestinian Salafi jihadists in Gaza or have worked with Hamas to smuggle weapons across the border. In addition, Cairo strongly resists any measure that could increase Gaza’s dependence on Egypt and thereby relieve Israel of its responsibilities in the area.

Abbas’s punitive policies

Since March 2017, Gaza’s socioeconomic and humanitarian predicament has become increasingly parlous, partly due to the punitive sanctions of Abbas and the PA. These measures have reduced PA contributions to Gaza from €92m to €83m per month, affecting fuel imports, healthcare, electricity, and civil servants’ salaries. However, during this time, the PA has continued to collect more than €100m per month in taxes on Gazan imports. The leadership in Ramallah has threatened to introduce further “national, legal, and financial measures”, such as severing all financial connections with Gaza, formally renouncing all PA responsibilities in the area, and declaring Gaza “rebel territory”.

Besides reducing Hamas’s ability to collect taxes, Abbas’s decision to cut the salaries of PA civil servants in Gaza by 50 percent – and to dock them a month’s wages in April 2018 – has sucked badly needed money out of the local economy. Meanwhile, the PA’s decision to cut fuel payments to the Israel Electric Corporation shortened the daily availability of electricity by at least 45 minutes. The PA is also reportedly delaying Gazans’ medical referrals to Israel or the West Bank, and restricting remittance payments.

Abbas has dismissed the international community’s concern about his approach. As justification, he has cited the PA’s lack of control over Gaza and his desire to force Hamas into reconciliation. But PA sanctions have had far more of an impact on ordinary Palestinians in Gaza, including those who were previously supportive of Fatah and Abbas.

Abbas’s actions have stoked widespread popular anger and made it more difficult for the PA to one day reassert control over Gaza. Furthermore, they are undermining the PA’s legitimacy in the West Bank, as seen in the large civil society-led protests in solidarity with Gaza in June 2018. In response, PA security forces and activists loyal to Abbas – popularly referred to as zu’ran (thugs) – conducted an unprecedented crackdown on demonstrators.

Elusive Palestinian reunification

The conflict between Hamas and Fatah that erupted into the open following the 2006 legislative elections culminated in the PA’s institutional and political ejection from Gaza, and the emergence of two parallel systems of law and order within Palestinian society. PA measures against Hamas will widen these internal divisions, further alienating Gaza from the West Bank.

Such rifts have damaged Palestine’s democratic institutions and prevented new presidential and legislative elections. Within Fatah, political manoeuvring ahead of Abbas’s departure has given rise to efforts to sideline (and eventually replace) the Hamas-controlled Palestinian Legislative Council with the Fatah-dominated Palestinian Central Council, part of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO). Meanwhile, strict limits on Gaza-West Bank trade have weakened the Palestinian economy. Failure to address these challenges complicates international efforts to help Gaza, undermining the foundations of Palestinian statehood and the notion of a two-state solution.

Hamas’s overture to Egypt

As Gaza’s plight worsens, there is increasing pressure on Hamas to find a solution or, failing that, to deflect popular anger towards Israel or the PA. The group has made several attempts to break the stranglehold on the Strip.

In May 2017, Hamas presented its new Political Document, which updates its official views on several issues. Although it still contains strong language toward Israel and does not officially repeal the group’s anti-Semitic (1988) founding charter, the paper reflects several significant shifts in position. It distances Hamas from the Muslim Brotherhood and opens the door for (non-violent) popular mobilisation as a legitimate form of resistance. It also goes some way towards accepting a two-state solution based on Israel’s 1967 border (even as the Israeli government has moved away from this position).

The Document speaks to an ongoing political debate within the group that began several years ago. It also reflects the pragmatic language found in the May 2006 Prisoners’ Document agreed by members of Hamas, Fatah, and other Palestinian factions in Israeli jails. Hamas timed the release of the Political Document partly as an overture to Egypt, reflecting Sinwar’s desire to improve relations with Cairo and thereby ease conditions in Gaza.

Return to Cairo?

Despite the restrictions it has placed on Gaza, Egypt is as much a part of the solution as it is part of the problem. It has for several years played an important role in mediation and deconfliction between Hamas and Israel, and in sponsoring intra-Palestinian reconciliation talks. For example, Egyptian mediation resulted in the April 2014 Shati Agreement, which led to the formation of a short-lived government of national consensus.

In 2017 Hamas discussed a potential deal with Egypt and Mohammed Dahlan, Abbas’s arch-rival in Fatah. Cairo pushed for the agreement partly out of concern that the deteriorating situation in Gaza would provoke a new conflict with Israel and further destabilise Sinai. The deal would have relaxed Egyptian restrictions in exchange for Hamas severing ties with Salafi jihadist groups in Sinai and allowing Dahlan to return as a political force in Gaza. This would have been quite the turnaround given that Hamas vilified Dahlan for commanding Fatah and PA forces in Gaza, and later ousted him as the PA’s enforcer there during intra-Palestinian fighting in 2007.

Egypt and Hamas ultimately abandoned the proposed deal in favour of renewed efforts to promote intra-Palestinian reconciliation, and to transfer governance of Gaza back to the PA. These efforts produced a new reconciliation agreement, which senior Fatah leader Azzam al-Ahmad and Saleh al-Arouri, deputy chairman of Hamas’s Politburo, signed in Cairo on 12 October 2017.

Despite the failure of previous reconciliation attempts, the talks renewed Gazans’ hopes that national reunification and an end to PA sanctions were on the horizon, raising the prospect of meaningful improvements in their daily lives and even an end to Israel’s siege. The negotiations made some early progress. The most symbolically important steps were the removal of Hamas’s “4-4 checkpoint” – which left the PA as the sole authority on the Palestinian side of the Erez Crossing – and the arrival of ministerial delegations from Ramallah to coordinate the return of Gazan ministries to the PA.

However, the momentum quickly dissipated. The reconciliation process entered a deep freeze on 13 March 2018, when unknown assailants attempted to assassinate PA Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah and the head of the Palestinian General Intelligence Service, General Majed Faraj. In the days that followed, the sides once again accused each other of acting in bad faith.

Internecine rivalry

Egypt has since resumed its efforts to advance reconciliation talks. Even if these make some further progress, the fundamental obstacles to Palestinian reunification remain. There is no lack of technical solutions but rather the absence of both the political will to compromise and the correct mixture of incentives and disincentives for doing so. Unless the sides abandon their internecine rivalry, full political reconciliation and national reunification will remain elusive.

Hamas appears to have been more receptive to Egypt’s overtures than Fatah, because of its domestic needs. Yet the group has refused to cede full security control of Gaza to the PA and to disarm. The PA has gone through the usual motions too, continuing to demand full control of Gaza – in line with the credo “one gun, one authority” under PA control – and refusing to roll back its sanctions. Cairo’s proposal for the establishment of a joint Hamas-PA security committee for Gaza under its supervision could have squared this circle, but it ran into opposition from Abbas.

Besides his personal animosity towards Hamas (and, reportedly, towards Gaza), Abbas sees little political value in making a deal in the current global, regional, and domestic environment. And it is unclear whether Abbas genuinely wants to return the PA to Gaza, given the dire state of the area and the difficulties of managing its security situation. Moreover, he and other Fatah leaders fear that Palestinian reunification would allow Hamas to dominate the PLO.

Just as importantly, Abbas and his advisers strongly believe that PA sanctions on Gaza are working. This is a somewhat dubious position. The measures may have indeed played a part in bringing Hamas to the negotiating table in October 2017. But there is little reason to believe they will succeed in forcing the group to its knees when a decade of international and Israeli sanctions have failed to do so. If anything, Abbas’s attempts to punish Hamas, and his refusal to lift the sanctions once discussions on reconciliation began, have pushed the group into bilateral talks with Israel – and could push it into another war should these talks fail.

The international roadblock to reconciliation

The policies of outside actors create significant obstacles to Palestinian reconciliation. The EU listed Hamas as a terrorist organisation in 2003. Following Hamas’s victory in free and fair Palestinian legislative elections in 2006, the EU and its partners in the Middle East Quartet (comprising the EU, Russia, the UN, and the US) paved the way for international efforts to sanction and isolate the Hamas-led PA government. This came amid Hamas’s refusal to sign up to the Quartet’s conditions: recognising Israel, renouncing violence, and abiding by the previous Israel-PLO agreements. Such terms echo parts of the PLO’s Charter. These conditions were originally aimed at Hamas members of the Palestinian government rather than at Hamas itself (as is the case today).

Under pressure from the George W Bush administration, the EU also adopted a no-contact policy on Hamas in 2007 – a policy that is both vague in its scope and has not received the formal approval of EU member states at the European Council. A decade later, the EU and the US are the only members of the Quartet to follow this policy.

In addition to stoking to intra-Palestinian divisions, this has blunted European diplomacy, limiting the EU’s ability to support both development in Gaza and reconciliation between Palestinian factions.

Brussels has effectively tied the hands of EU and member state diplomats, forcing them to rely on the UN and non-EU countries (particularly Norway and Switzerland) to engage with Hamas on a political and working level. This approach prevents dialogue with more pragmatic members of the group.

Equally damaging has been the EU’s threat to cut aid to the PA if it strikes a unity deal with Hamas that does not meet the Quartet’s 2006 conditions. The EU’s intransigence on this issue has contributed to the failure of past Palestinian reconciliation efforts such as the 2007 Mecca Agreement (which Saudi Arabia brokered).

This differs markedly from how the EU has approached other militant groups. Despite listing Hizbullah’s military wing as a terrorist entity, European diplomats engage with the group’s political wing and the Hizbullah-dominated Lebanese government. And, while several European states continue to fight against the Taliban as part of the US-led coalition in Afghanistan, the group does not appear on the EU’s list of terrorist organisations. American officials also continue to meet with Taliban members as part of Afghan peace talks. Elsewhere, the EU suspended its sanctions against FARC rebels after they signed a reconciliation agreement with the Colombian government in 2016.

The March of Return protests

Facing an impasse in reconciliation talks, Hamas has sought to deal with Israel bilaterally. In this, it has received a political boost from weekly “March of Return” protests along the border with Israel, which regularly attract thousands of participants. Hamas leaders have credited these demonstrations with placing Gaza back on the international diplomatic agenda while forcing Israel to treat Gaza as a political issue that requires negotiations with the group. These tactics have provided an important alternative to sporadic rocket attacks or full-blown war.

Civil society activism and popular anger over conditions in Gaza continue to be the primary drivers of protests. However, Hamas and other militant groups, including Palestinian Islamic Jihad, have co-opted the demonstrations to an extent. Hamas has proven particularly adept at adjusting their intensity according to its needs in talks with Israel.

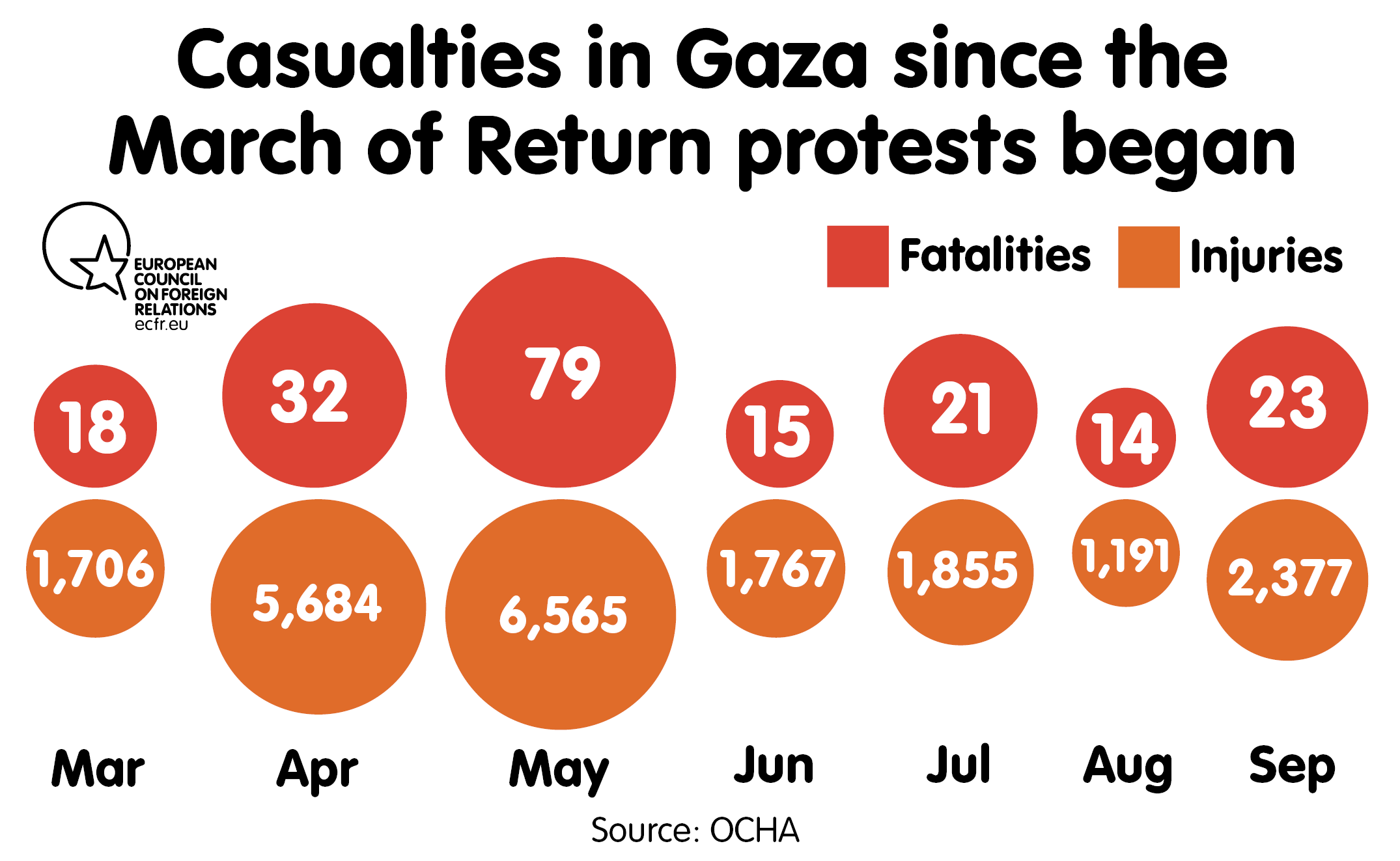

This has come at a high cost. Since the first such protest on 30 March 2018, more than 180 Gazans have been killed and 19,000 wounded. Although a small number of militants have been hurt, the vast majority of the victims were unarmed civilians. The high casualty rate partly stems from a relaxation of the Israel Defense Forces’ (IDF) rules of engagement, and the adoption of a “zero-tolerance policy” toward protests.

And, while the demonstrators are predominantly peaceful, some have become increasingly violent (and nihilistic) in response to Israel’s use of live fire. Militants have also used the protests as cover for planting improvised explosive devices, sniping at Israeli troops, and launching incendiary kites and balloons at Israeli communities. Although these attacks do not pose a significant threat to Israel, they have killed an Israeli soldier (who was the first to die in combat since the 2014 war) and have caused more than €1.7m worth of damage to Israeli crops.

International stabilisation efforts

Because Hamas, Israel, and many foreign actors want to prevent Gaza from imploding, they have a renewed interest in international stabilisation measures. This interest has focused almost entirely on economic development and technical assistance, based on the assumption that there will be less violence if the economy improves.

Israel’s policy dilemma

The situation in Gaza has created a dilemma for Israel. As one Israeli military officer acknowledged: “you can’t start a war over some balloons, but you can’t do nothing either.” Senior members of the Israeli security establishment, such as IDF Chief of Staff Gadi Eizenkot and National Security Adviser Meir Ben-Shabbat, have urged restraint.

Even as the IDF intensifies its use of force against protesters, Israeli security officials have voiced support for restoring calm in Gaza through limited and controlled efforts to loosen restrictions on the area. They believe that easing the humanitarian crisis and providing economic stimulus there could ease pressure on Hamas, making the group less likely to see confrontation as the only way out of its predicament. However, the steps Israel has considered taking would fall far short of fully lifting Israeli restrictions, and could be easily rolled back.

During the past year, Israeli officials – especially those within the military and the Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT) – have promoted a Marshall Plan for Gaza. At the emergency meeting of the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee (AHLC) in Brussels in January 2018, Israeli representatives sought $1 billion in international funding for an infrastructure plan that involved a series of energy, water, and economic projects, including desalination plants, electricity lines, and a gas pipeline, as well as an initiative to upgrade the Erez industrial park, on the Israeli-Gazan border. This effort does not involve any significant relaxation of Israel’s closure policy nor direct Israeli financing.

The Israeli security establishment’s thinking contrasts with the hard line of Israeli cabinet members, who have called for a more forceful response and tightened restrictions. The main proponents of this approach are Defence Minister Avigdor Lieberman and Minister of Education Naftali Bennett, who compete against each other to be toughest on Gaza. They aim to signal to Hamas that Israel is ready for war, reassure Israeli border communities caught up in the violence, and position themselves politically in anticipation of elections by early 2019.

Crucially, Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu remains averse to risk and, for now, opposed to a large-scale military offensive in Gaza. Nonetheless, domestic political considerations are also pushing him towards stronger action to restore order there.

The competing beliefs within Israel’s political-military system make for incoherent policy. The prime minister’s office and COGAT have supported UN stabilisation initiatives in Gaza, particularly new shipments of fuel. Meanwhile, Lieberman has pushed the military to use greater force against protesters and to tighten restrictions on Gaza, at times delaying these same shipments.

A Trumpian vision for Gaza?

The Trump administration has shown an interest in Gaza. While the details of a potential US peace plan for Israel-Palestine remain unclear, the White House has floated a very narrowly focused economic (business-orientated) approach towards Gaza that is purposely divorced from the political context.

In March 2018, the US hosted a brainstorming session with officials from Europe, the Middle East, and Israel to support an economic solution to Gaza’s crisis. The PA boycotted the meeting, viewing it as a ploy to establish a Palestinian mini-state in Gaza and undermine Abbas’s rule. Participants in the session were presented with a PowerPoint document containing a range of potential projects that they could fund to ease Gazans’ suffering.

The US plan included short-, medium-, and long-term initiatives. American officials proposed that, in the short term, international funding should help repair power lines linking Gaza to Egypt, increase exports from Gaza, install small solar farms there, and open a crossing for commercial traffic at Rafah. The session’s attendees were also presented with more ambitious, medium-term projects that would involve supplying the Gaza Power Plant with natural gas, creating a 4G mobile-communications network, and constructing a desalination plant. The long-term (aspirational) initiatives the White House suggested covered the development of the Gaza Marine gas field, a West Bank-Gaza transport network, a Gaza-Egypt-Israel industrial zone, and a tourism corridor running from northern Sinai through Gaza to Aleppo.

During subsequent meetings of the AHLC, the US tried to attract international funding for its economic package – albeit without success. On the face of it, the short- and medium-term projects proposed at the brainstorming session reflect other international donors’ efforts. However, the US has promoted and developed its economic initiative as an alternative to these efforts, having engaged in little consultation with them.

The US approach to Gaza suffers from striking contradictions. Firstly, while the White House has taken an extremely hostile position on the PA and Abbas, it simultaneously set their return to Gaza as a precondition for economic development. Secondly, although it is discussing stabilisation initiatives in the area, the Trump administration’s decision to eliminate US funding for UNRWA and USAID projects has contributed to greater instability there. Finally, despite rarely consulting its international partners on its plans for Gaza, the US remains reliant on them for funding.

After its economic plan failed to gain traction and ran into resistance from the PA, the Trump administration concluded that international donors should not spend any more money on Gaza because doing so has failed to move the Israelis and the Palestinians closer to a peace agreement. In contrast, Israeli officials from COGAT are still actively fundraising to stabilise Gaza.

EU funding and technical assistance

The EU is regularly typecast as a “payer” in Gaza – not without reason – and it continues to come under pressure from its international partners to fund development projects there. Partly because this is a role it feels relatively comfortable with, the EU has committed €146m to Gaza’s development. The EU has pledged an additional €63m to the planned Gaza Central Desalination Plant, and more than €82m per year in support of UNRWA activities there.

A non-paper the European External Action Service and the European Commission drafted in September 2018 calls for accelerating additional “short-term projects in the fields of job creation, energy, water, and health.” It also proposes advancing other projects for “long-term sustainable development in energy (Gas for Gaza), water […] and private sector development.” But, as with the proposals the US and Israel developed, the EU has largely avoided practical efforts to address core political issues.

Moreover, the EU maintains two important Common Security and Defence Policy missions in Palestine: the EU Police and Rule of Law Mission for the Palestinian Territories (EUPOL COPPS) and the mostly dormant EU Border Assistance Mission for the Rafah Crossing Point (EUBAM Rafah). The EU could expand these missions to support the resumption of PA governance functions and border controls in Gaza.

The missing politics of stabilisation

There is an urgent need for projects that can quickly help stabilise Gaza. Yet any international effort there that focuses only on humanitarian, financial, or economic issues while neglecting political factors will prove unsustainable in the long term.

As past failures and current frustrations show, several factors that are essentially political in nature will continue to stymie such initiatives. In promoting a package of exclusively economic and humanitarian projects that leave politics at the door, foreign donors risk forgetting the lessons of recent decades.

International donors’ reluctance to confront Israeli restrictions head on has limited successive economic initiatives. For instance, the 2004-2005 World Bank plan that US economist James Wolfensohn championed ran aground due to Israel’s unwillingness to lift its restrictions and implement the 2005 Agreement on Movement and Access (AMA). Similarly, within the West Bank economic and state-building model, an unwillingness to challenge Israeli restrictions has in the past two decades created an economy that is heavily dependent on aid and is now faltering.

Furthermore, international donors will remain reluctant to invest in expensive infrastructure projects that are almost certain to be destroyed in another war. Only a political solution can significantly reduce the likelihood of renewed conflict.

Finally, history shows that including Hamas – as the de facto authority in Gaza – in the planning and implementation of international projects is the sine qua non for progress. But the EU’s no-contact policy has precluded this approach and constrained international development agencies’ attempts to implement humanitarian programmes and provide development assistance.

The UN gambit

Following the recent flurry of donor proposals for development initiatives in Gaza, the UN has sought to enhance its coordination and implementation capacity there through the creation of a Project Management Unit. The unit aims to implement a complex package of UN humanitarian efforts. Accordingly, members of the AHLC – including Norway, the EU, the US, Israel, and the PA – signed off on a first package of projects in September 2018.

Since then, the UN has sought to work with the PA, Hamas, and Israel (with the support of external donors) to implement the agreed list of projects. These focus on improving electricity services, water supply, and healthcare in Gaza, as well as on resuming the full payment of civil servants’ salaries there.

While it centres on technical issues, the UN package has a political edge in that it provides a basis for de-escalation between Hamas and Israel. If fully implemented, the package would lead to tangible (albeit limited) improvements in Gazans’ economic situation and daily lives, while regularising access and movement. In exchange, Hamas would be expected to reduce weekly demonstrations along the border and prevent launches of rockets and improvised incendiaries into Israeli territory. This could potentially revivify the 2014 ceasefire arrangement between Hamas and Israel. However, the UN’s initiative stops short of directly challenging the logic of Israeli restrictions.

A three-step deal?

In response to an AHLC request, Qatar agreed to donate €52m for six months of fuel shipments to Gaza. Israel began these shipments on 9 October, briefly suspended them following large-scale protests on 14 October, and then resumed them. Currently, this has doubled the daily period in which electricity is available from less than four hours to between eight and ten hours.

In a second step, international and regional actors are exploring ways to use additional Qatari funding to cover wages and increase employment rates in Gaza. Such an injection of cash into Gaza would strengthen household purchasing power and stimulate basic economic activity. Qatar has reportedly agreed to transfer €79 million to Hamas over six months, partly to cover the salaries of the group’s civil servants (excluding its security forces). Qatar's representative in Gaza Ambassador Mohammed Al Emadi delivered the first instalment of €13 million in three suitcases through Israel's Erez crossing on 8 November. The country appears to have done so without the direct involvement of either the UN or the PA.

Separately, there has been media speculation that a prisoner swap may be in the works. This would require Hamas to hand over the remains of two fallen IDF soldiers, along with two captured Israeli civilians, in exchange for Palestinian prisoners Israel has detained – an arrangement that potentially resembles the 2011 Gilad Shalit deal.

These are important confidence-building measures that would improve the situation in Gaza and provide both sides with “wins”, thereby lowering the political temperature. Yet, with the possible exception of a prisoner exchange, none of these measures involves any real Israeli or Hamas concessions beyond enacting the 2014 ceasefire arrangement. And, although it has supported steps to stabilise Gaza, Israel has thus far shown no willingness to significantly rethink its restrictions on the area, let alone to make financial contributions to it. The fact that the Qatari payments seem to be a one-off raises questions about how Hamas, which is becoming dependent on Qatari funding, will react once the six-month financial instalments come to an end.

Stability versus governance

Squaring the need to shore up short-term stability with efforts to restore PA governance in Gaza has proven difficult. Although Hamdallah supported the UN initiative during AHLC discussions, Abbas has actively obstructed them as part of what he perceives to be a broader US scheme. In this way, the leadership in Ramallah continues to condition each initiative on what amounts to Hamas’s full surrender to its authority.

In light of Abbas’s refusal to cooperate, the UN had to circumvent the PA and broker a bilateral arrangement between Hamas and Israel. The urgent need to avert another conflict in Gaza and improve conditions in the area has driven the move. Yet there is a chance that the approach will provoke further retaliation from Abbas, who has threatened this since before the UN’s began its initiative.

His stance not only prevents the PA from becoming an active partner in the resolution of the crisis, but also damages Palestinian foreign relations and causes friction within the AHLC. The leadership in Ramallah has threatened UN staff and rejected UN Special Coordinator Nikolay Mladenov as an intermediary because he allegedly had a negative impact on the national security and unity of the Palestinian people.

For their part, members of the AHLC have given their full backing to the UN initiative and condemned Abbas’s actions. The organisation has even issued a demarche against the PA, expressing “deep concerns over recent attempts to delay and undermine a speedy implementation of the UN humanitarian package in Gaza”. President Sisi and EU heads of state have quietly reinforced this message in their meetings with Abbas.[3]

Can the EU build on the UN initiative?

Beyond the immediate need to ameliorate the situation in Gaza and prevent another war, the EU should treat the UN initiative as a springboard for an international push for Palestinian reunification and sovereignty-building. To do so, the EU will need to be clear-eyed about the challenges ahead, and promote moderating policies that can shift Israel, the PA, and Hamas away from putting their rivalries with one another before all else.

In September 2017, EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini announced a review of the EU’s modes of engagement with the Israel-Palestine conflict, aiming to better align the organisation’s activities and instruments with the pursuit of a two-state solution. This review is an opportunity to rethink some aspects of the EU’s engagement with Gaza.

At a time of declining donor support for Gaza, the EU’s financial commitment to the area is increasingly valuable. But funding limitations mean that the EU will have to be ever more strategic in the projects it supports. To make progress, the EU needs to develop a more realistic political map that can guide its technical and financial support for Gaza. This would not only help determine which projects the EU should prioritise, but would also help ensure that each initiative fits within a broader strategy for effecting change on the ground. All these steps require a genuine EU willingness to challenge the structural impediments to opening Gaza (a process that fits with what the non-paper refers to as “triangulation”).

As part of this, the EU could push for a new and more realistic AMA for Gaza that reflects the political realities that have emerged since the 2005 AMA, and that would be expanded to include the four parties: Israel, Egypt, the PA, and Hamas. Critically, a new AMA would have to include a strong supervision and enforcement mechanism to ensure the parties fully implemented it.

Challenging Israeli policy

Challenging Israeli policy

Ending Israel’s policy of closure and separation in Gaza must be at the forefront of the EU’s strategy. So long as it endures, this will prevent the full reconstruction and economic redevelopment of the area. Israel has legitimate security concerns about militant activity in Gaza. But its current closure regime, which is disproportionate to the threat it faces, amounts to collective punishment.

At a minimum, the EU should push Israel to tighten its rules of engagement and end all forms of collective punishment in Gaza. The EU should also firmly communicate its opposition to any Israeli attempt to prevent the swift implementation of the AHLC-approved development package for the area.

The EU should stress the importance of Israel shouldering its responsibilities under the 2014 ceasefire arrangement, the Oslo II Accords, and international humanitarian law. Combined, these important de-escalation measures are necessary to establish and maintain calm between Israel and Hamas in the long term. With this in mind, the EU should push Israel to:

- Ensure the movement of goods and people (including students and medical patients) between Gaza and the West Bank, and allow Gaza to trade with the outside world, including by opening commercial crossings, providing for the speedy export of all agricultural products, and streamlining trade procedures.

- Extend Gaza’s fishing zone to 20 nautical miles from the coast as Oslo II stipulates; and allow Palestinians forcibly displaced from the Access Restricted Areas near the border to safely access their lands and receive compensation.

- Align Israel’s list of prohibited dual-use items with the international Wassenaar Arrangement.

- Increase the number of Israeli work and business permits available to Gazans to pre-2005 levels; and remove excessive restrictions on passengers at Erez Crossing, including on those carrying any electronic item besides a mobile phone.

- Allow the PA to exploit the Gaza Marine gas field without interference.

Strong words for Abbas

As discussed above, the future of Gaza – and of the Palestinian national project – depends on Palestinian reunification, the return of PA governance to Gaza, and the restoration of Palestinian institutions. Establishing a government of national unity that includes Hamas and reunifying Palestinian institutions is the best way to achieve these aims.

But fulfilling such steps should not be a condition for short-term initiatives to stabilise Gaza, nor should it be used to justify the PA’s efforts to derail the AHLC-approved development package and obstruct UN attempts to prevent another conflict.

While strongly speaking out against the PA’s actions, EU leaders should call on it to:

- Immediately end all sanctions on Gaza, including cuts to civil servants’ wages, and withdraw plans for further punitive measures.

- Constructively re-engage with the AHLC to help facilitate international efforts to improve Gaza’s collapsing energy, water, and healthcare infrastructure.

- Publicly commit to reactivating Palestinian democratic institutions such as the Palestinian Legislative Council, and to holding municipal, legislative, and presidential elections that include Gaza.

The EU and its member states should also make full use of their diplomatic and financial leverage to develop an additional package of incentives and disincentives for the PA. In doing so, they could:

- Offer financial support for unifying the civil service in Gaza under the auspices of the PA.

- Provide Abbas with diplomatic cover should a future US peace plan depart from the international consensus on the parameters underpinning a two-state solution.

- Offer to host more frequent EU-Palestine dialogues at both the political and working levels.

- Explore the extent to which Europe could condition its financial support for the PA on the organisation’s support for reconciliation and how constructive its role in Gaza is; and reassess support for EUPOL COPPS accordingly.

- Warn the PA that its punitive measures risk inhibiting Palestinian relations with key European partners at a time when Abbas is increasingly reliant on EU support and engagement; and that these measures could have a negative effect on member states’ future decisions on whether to recognise Palestine.

Engaging with and pressuring Hamas

The EU must accept its share of the blame for the crisis in Gaza and the area’s split from the West Bank. The EU’s current policy of containing and isolating Hamas has not worked. Nor has it stopped three destructive wars with Israel.

It is time for the EU to end this policy, which no longer reflects the reality on the ground. While the Israeli government can be expected to oppose such a move, its dealings with Gaza demonstrate the logic of engagement with Hamas. Without engagement with the group, it will be impossible to create a sustainable solution for Gaza. Moreover, Hamas cannot be simply ignored or wished away, as it is an undeniable facet of Palestinian politics and society – both in Gaza and the West Bank, where it dominates student politics.

In its non-paper, the EU raised the possibility that it would increasingly engage in diplomacy on the ground, practise “preventive diplomacy”, and mediate between the parties. But it is difficult to see how the EU can achieve any of this while holding fast to its position on Hamas. Ultimately, if the EU wants to exert influence on Hamas, and to help fix Gaza, it will need to talk with members of the group on some level.

Since Hamas wants to be seen as a legitimate political actor, the EU has some leverage over it. Therefore, the EU could push the group towards further moderation in return for a full repeal of the non-contact policy. This would require careful choreography between the sides, with the ultimate aim of political dialogue and the EU delisting Hamas’s political wing. In return, the group would fully commit to the political track and renounce violence against civilians.

As part of the process, the EU could (in sequence):

- Publicly welcome Hamas’s May 2017 Political Document as a step in the right direction.

- Commit to working with – and funding – any future government of national unity that supports a peaceful resolution of the conflict, regardless of its members’ party affiliations.

- Offer to abandon the no-contact policy with Hamas if it adopts the PLO’s Charter and/or commits to international humanitarian law prohibiting the use of armed force against civilians.

- Offer to remove Hamas’s political wing from the EU list of terrorist organisations if the group amends its Political Document to reflect the above conditions and to explicitly and institutionally separate its military and political wings.

Dealing with the Trump administration

In principle, the Trump administration’s apparent desire to improve conditions in Gaza should be welcomed. Indeed, there is considerable overlap between the Gazan development projects envisaged by the White House and those approved through the AHLC. But American efforts should not be an alternative, nor an impediment, to AHLC efforts. The Trump administration’s reported attempts to convince foreign donors to invest in its project at the expense of the AHLC-approved track are particularly worrying. Moreover, US plans must facilitate a two-state solution and allow for engagement with all parties on the ground.

In dealing with the White House on the issue, the EU should, therefore:

- Stress that the success of any US initiative for improving Gaza’s economic situation depends on good relations with Palestinian actors, the repeal of Israeli restrictions, and the resumption of funding for UNRWA and USAID projects.

- Make clear that any US development initiative should be channelled through the AHLC.

- State that the EU will not condition short-term stabilisation efforts in Gaza on the PA returning to the area or Hamas disarming.

- Act independently, including in engaging with Hamas.

- Link development efforts with a clear political track and the implementation of a two-state solution – in line with the international consensus on its parameters – while preserving the principles of humanitarian aid delivery.

Driving collective action

The situation in Gaza requires both economic and political solutions. As an important first step towards preventing further escalation, the UN initiative deserves the EU’s full support. It has provided an important starting point that can go some way to addressing Gaza’s economic challenges. At a minimum, this may provide Gazans with a glimmer of hope for their economic future, not least in the prospects of easing restrictions on the area and de-escalating the confrontation with Israel.

However, the potential gains from such an undertaking are both limited and heavily dependent on Israeli goodwill. They are also threatened by continued Palestinian in-fighting. By itself, the UN initiative cannot provide a holistic solution for Gaza, restore full calm along the border, or achieve Palestinian reunification.

It is now time for the international community to engage in collective action that can overcome the political obstacles to sustainable change. Thanks to its economic and (often underused) political power, the EU and its member states have an important role to play in leading such efforts. But this will require them to move out of their comfort zone, adjusting their policies towards actors on the ground and filling the political vacuum left by the Trump administration. As one UN official put it: “war in Gaza can happen regardless, but a sustainable solution can only come with the EU’s help.”[4]

Acknowledgements

As ever, I am most grateful to all those who have been so forthcoming with their wisdom and expertise on Gaza in recent years. Special mention goes to Hady Amr, Tareq Baconi, Martin Konečný, Donald Macintyre, Hani Masri, Omar Shaban, and Nathan Stock, along with several officials and diplomats, for being so generous with their time. Needless to say, all mistakes and omissions in the report are solely my own. I also owe a massive thanks to ECFR’s MENA director, Julien Barnes-Dacey, for battling his way through an early first draft of the report, as well as ECFR editor Chris Raggett for his valuable support and dedication.

About the author

Hugh Lovatt is a Policy Fellow with ECFR’s Middle East and North Africa Programme. In this role, he has focused extensively on EU policy towards the Middle East Peace Process and domestic Palestinian politics. He also co-developed an innovative online project Mapping Palestinian Politics.

Footnotes

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.