Fragmentation nation: How Europeans can help end the conflict in Yemen

Summary

-

- For eight years, Yemen has suffered a civil war, whose conduct has been exacerbated by outside powers, principally Saudi Arabia and the UAE on one side, while Iran has supported the other.

-

- Yemen is a politically, socially, geographically, and religiously fragmented country, including within the two broad areas controlled by the internationally recognised government and the Houthis respectively.

-

- Saudi Arabia and the UAE may soon decrease their military interference in Yemen – but their exit could expose divisions in both government and Houthi areas.

-

- Yemen was poor before the conflict, but a corrupt war economy has now taken hold, strengthening an array of local power holders, while the Yemeni people slip into ever-deeper destitution.

-

- Short-term measures introduced with the support of the international community have failed to stabilise the situation.

-

- Europeans should take a longer-term approach to Yemen. They should promote the country’s cause in their diplomacy with Gulf Arab states and make a commitment to economic support, a values-based approach, and an emphasis on human rights in Yemen.

Introduction

Yemen is becoming an ever more fragmented country – to such an extent that it may soon be impossible ever to piece it back together again. A combination of internal dynamics exacerbated by the actions of neighbouring states has brought Yemen to this pass. For the international community, and the European Union and European states, addressing this will be difficult – but they can do so by providing long-term help, rather than lurching between short-term fixes.

The notion, and reality, of Yemen as a divided nation is not new. The Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) each existed as separate states before their unification in 1990. Divisions between north and south remain strongly relevant today, and for the past eight years Yemen has experienced civil war between the Houthis and the internationally recognised government (IRG). Numerous factors and historical legacies risk splitting Yemen irreparably. These include the ‘divide and rule’ approach of the country’s former president, Ali Abdullah Saleh; the funding and encouragement of centrifugal tendencies within the country by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates; and rising sectarianism across Yemen. All this has resulted in the country breaking down into a multiplicity of areas under the control of a range of militias and local leaders.

International policymakers looking to understand Yemen and restore peace – and perhaps one day even help a single government return to run the whole country – will need to take account of this increasing fragmentation and tailor their policies accordingly. They will need to take a long-term approach to address structural problems; doing so will help them to establish internationally supported political peace processes. The recent truce gave some respite to Yemenis during 2022, and its expiry only re-emphasises the need to take on this formidable task. In particular, Europeans can help Yemen transition away from its war economy and improve basic public services. Better economic prospects will help ease some of the wider tensions across the country.

Europeans can also offer support to bring Yemen’s divided communities together and help foster a sense of nationhood, which has been damaged by the experience of recent decades. The truce brought some momentum with it; and, crucially, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are looking to scale back their involvement in the country. Yet, even as their retreat carries the potential to alleviate Yemen’s problems – which Riyadh and Abu Dhabi each spent a decade stoking in their own interest – it could also expose old fault lines, especially in Houthi-controlled areas, where the Houthis have relied on opposition to external interference to consolidate support.

This paper argues that, rather than narrowly focusing on quickly drawing up a new political process – though this remains a worthy goal – Europeans need to adopt a wider, longer-term lens when revising their Yemen policy, addressing the country’s fundamental structural weaknesses. Regardless of whether a new truce is agreed, they should undertake efforts to slow and reverse fragmentation trends and economic collapse. This paper lays out specific ideas for how Europeans can achieve this.

The truce – and prospects to end international military intervention

Yemen has endured eight years of civil war, during which neighbouring Saudi Arabia and the UAE have intervened militarily as part of a coalition that includes other states in the region. Together, these states drastically exacerbated an already-fraught internal situation. They have not acted in a uniform way, however. Saudi Arabia opposes separatist movements within Yemen, and its policy has been to work towards a unified state. The UAE, meanwhile, has aimed to weaken certain Islamist forces within Yemen and support groups that effectively contribute to the country’s fragmentation.

In April 2022, the IRG and the Houthis agreed to a UN-mediated truce. This ran out in October, but by the time it expired it had delivered the most significant decrease in violence since the war began in 2014. The end of the truce was a major disappointment for Yemenis and all others concerned with their fate. But it highlighted the fact that Saudi Arabia is now focused on ending its involvement in the conflict, and in particular is looking for a way to stop Houthi cross-border attacks into its territory. For their part, the Houthis retain their long-term demands of holding direct negotiations with Saudi Arabia; indeed, previously secret negotiations between them are now complemented by talks that the two sides publicly acknowledge. These may be the prelude to a partial but very problematic solution.

The fact that the international direct participants to the war are searching for an exit will alter the conflict dynamics in Yemen once more, exposing both historical and more recent divisions. The next phase could therefore see an intensification in the long-running internal fight for control of the country. It is vital for those concerned with the future and stability of Yemen to understand the new dynamics that could now come to the fore, how these could influence the pursuit of a sustainable political solution, and what wider economic and humanitarian support international actors such as the EU and European states should provide.

Fragmentation and the disintegration of the nation

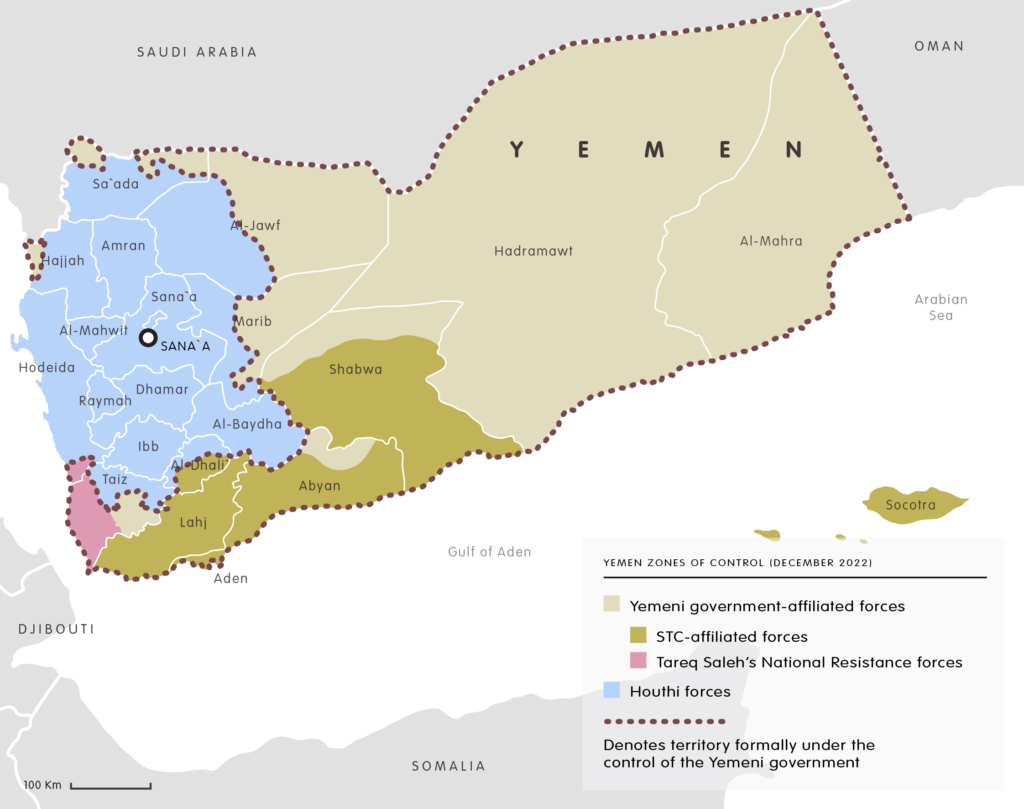

Yemen today is a deeply fragmentated nation. The map below displays the territory held by the IRG and the territory held by the Houthi rebels, who took over Yemen’s capital, Sana’a, in 2014. This broad split is central to the present conflict, but other divisions also exist within and across these areas.

The former regime of President Saleh is responsible for some of this. Following Saleh’s leadership of the YAR from 1978 onwards, he then ruled the Republic of Yemen from its unification in 1990 until he was overthrown in 2012. He enacted a ‘divide and rule’ policy that exacerbated tensions within the country and obliterated the enthusiasm felt by the overwhelming majority of Yemenis at the unified republic’s foundation. To prevent the emergence of any coherent opposition to his rule, Saleh and his security agents encouraged community-level conflicts within and between tribes, or other social groups.

This reversed the unifying trends of the twentieth century, in which migration between the YAR and the PDRY was commonplace, and intermarriages between individuals from both states was frequent. Such factors strengthened perceptions of a shared Yemeni national identity at a time when nationalism was the dominant ideology throughout the Middle East. As nationalism declined in influence across the region from the 1970s onwards, Islamism rose in its place. This took different sectarian and political forms, including some specific to Yemen. Alongside this, other factors in the past two decades have undermined national cohesion and produced social and political fragmentation driven in large part by a turn towards a local version of identity politics. This helped the country along the path to its civil war. The most visible forms this took in Yemen were the rise of the Houthi movement in the far north of the country, and that of southern separatism in the south and east. The war has, in turn, further exacerbated these divisions.

Internationally recognised government territory

Two structural types of fragmentation in the territory controlled by the IRG are important to understand. The first occurs within the territory of the former PDRY – this is often termed “southern separatism”. The second is found elsewhere in the IRG-controlled areas, which are geographically disconnected and politically diverse, including both the coastal Tihama region and the northern Marib governorate.

Political fragmentation is most visible and particularly intense in the southern governorates. Here, since 2017, the struggle is between the IRG and the Southern Transitional Council (STC), which was established in May 2017 in opposition to the IRG with the aim of re-establishing an independent state in the area of the former PDRY. But there are other southern separatist organisations, as well as significant numbers of southerners who support unity. Southern separatists argue that they have a national identity distinct from that of other Yemenis. The UAE has given support to the STC by providing massive financial, diplomatic, and, most importantly, direct military assistance. This enabled the STC to emerge as a dominant force among a larger group of southern separatist factions. Yet the IRG remains committed to restoring its authority over the entire republic and its differences with the STC have involved military action.

On 7 April 2022, the IRG’s president, Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, and his vice-president were removed from power, in a move orchestrated by Saudi Arabia and the UAE under the umbrella of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). They were replaced by a Presidential Leadership Council (PLC) composed of eight men. The creation of the PLC suggested a meeting of minds between Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, and was intended to create a united leadership between the different factions confronting the Houthis and bring the war to an end. Previously, Saudi Arabia’s and the UAE’s support for rival groups had worsened the divisions within the anti-Houthi forces facing the apparently unified strength of the Houthi movement. The international community now treats the PLC as the recognised executive authority of Yemen, despite its lack of constitutional status.

The PLC includes a number of significant military leaders and is led by Rashad al Alimi, a former minister of the interior from Taiz region. The remaining members are all tribal leaders: three from northern governorates, and four southerners. But the reality is that their only shared characteristic is opposition to the Houthis. Predictably enough, long-standing internal rivalries, even enmities, between its members have already emerged. Throughout the war, and since April this year, military confrontations have increased between units under the authority of different members of the PLC. For example, in July STC-aligned forces expelled their rivals from Shabwa governorate, accusing them of being Islahis. This was despite the fact that the Islah political party is a major component of the IRG and part of the government army, and that two members of the PLC are Islahis. (The party remains politically influential throughout the country, however.) Islah is connected to the Muslim Brotherhood, which is why the UAE actively opposes the party in Yemen.

Meanwhile, in August the STC attempted to co-opt one of its main rival separatist factions, the Southern Hirak Revolutionary Council, which has a strong following in Hadramawt governorate. But part of this movement rejected its own leader’s agreement on this, leading to a series of rival popular demonstrations in towns in Hadramawt and Mahra in September and October 2022. These demonstrations may be a prelude to military efforts by the STC to oust the army from these governorates, branding them ‘northern.’ The picture is clearly complex, if not fractured.

The use of the administrative term ‘governorates’ to describe areas of socio-political conflicts is misleading. To illustrate: elsewhere in the remaining parts of the area of the former PDRY, there is little solidarity between, for example, the neighbouring Yafi’is (an important southern tribe divided between Lahj and Abyan governorates) and the denizens of the northern hinterland of Aden in Lahej and parts of current Dhali’ governorate, let alone between the alliances of leaders of these two areas with Awlaqis from Shabwa. Beyond their historical military conflict in 1986 in the PDRY, this rivalry was a major component of the struggle between the STC and the Hadi government in the past decade. Another case in point is the competition between the different southern forces aligned with the UAE: the Amaliqa and the Security Belts in Lahej and Abyan further cut across these areas. This reflects power struggles over control of minimal local resources, rather than any meaningful distinct political, social, or cultural characteristics.

Other key locations in the IRG area include the Red Sea coastal plain of the Tihama, and the eastern, sahelian Marib. The first is the current stronghold of Tareq Saleh, a military leader and nephew of former president Saleh, while the latter is dominated by the tribal leader Sultan al Arada. The Tihami economy is based on agriculture and fisheries dominated by large landholders and boat owners, while Marib controls Yemen’s gas resources and much of its oil, with a tribal social structure. Overall, these examples demonstrate the lack of unity and the potential for rivalries and competition within what is supposed to be a united front.

This struggle within the IRG-controlled area is likely to continue, harming prospects for a united front and common purpose within the PLC. In late September, all its members were summoned to Riyadh for a dressing-down by the Saudis following earlier infighting, but at the time of writing, the Saudis’ admonition had produced no noticeable outcome. Without genuine consolidation and unity within the PLC it will be difficult for a genuine intra-Yemen political process to get off the ground – and thus difficult to achieve meaningful peace and economic reconstruction in the country.

Houthi territory

There are also significant – though currently suppressed – competing political factions and identities within Houthi-controlled areas. These have been less visible since the Houthis took full control in their part of the country following the killing of Saleh in December 2017. The efficiently repressive and authoritarian Houthi regime may have driven political fragmentation underground, but underlying tensions remain which could re-emerge when circumstances alter.

For many years, opposing the “foreign aggressor” – Saudi Arabia – has been the main rallying point uniting people around the Houthi movement. The end of the internationalised element of the war, in the form of Saudi Arabia and the UAE effectively terminating their deep involvement in Yemen, could animate fragmentation processes in Houthi-controlled parts of the country.

Numerous issues divide society under Houthi rule. A regional-cultural element clearly marks differences between, for example, Tihamis and highlanders. In addition to having its own ‘separatist’ movement, the Tihama has a history of dissent against rule from Sana’a, from which the Houthis now govern. The Houthis are Zaydis, a branch of Shia Islam, while the Tihama is populated by Shafi’is, who are Sunni. The people of the areas in the southern highland part of Houthi-controlled areas (such as Ibb, Taiz, and Baydha are also Shafi’is and have a culture that is significantly more liberal than that of the Zaydi Houthi rulers.

In the Zaydi heartland – the central and northern highlands – there are two main sources of potential dissent and fragmentation: tribalism and different interpretations of Zaydi norms and culture. With respect to the tribes and their alliance with the Houthis, one of the main factors binding them together is a shared opposition to foreign intervention. The possible end of the Saudi-Emirati intervention means that tribal leaders are likely to review their allegiances according to their own interests and wider changes in the overall balance of power. Tribes and the Houthis also share opposition to the power of the al Ahmar family, which used to dominate the Hashed tribal confederation. However, the official head of the family, Shaykh Sadeq bin Abdullah al Ahmar, has remained in Sana’a throughout the conflict, and he retains some authority – something that he is likely to try and revive when the opportunity arises.

Sectarianism

On top of regional and political divisions, rising sectarianism is another facet of the fragmentation of Yemen. Until the end of the twentieth century, sectarianism was insignificant as a socially divisive factor in Yemen, largely due to the very few theological and ritual differences between the two main sects, Shia Zaydism and Sunni Shafi’ism. Zaydism is the Yemeni, ‘fiver’ form of Shiism. Shafi’ism is the school followed by Yemeni Sunnis, while Salafis are extremist Sunnis,

The rise of sectarianism was encouraged, even sponsored, by Saleh during his long rule. But it also had its own genuine separate momentum, which arose directly from the divisive actions of political parties – in particular, Ansar Allah (the Houthis) and Islah (officially the Yemeni Congregation for Reform). Each has used religious language and rituals to proselytise and gain adherents to its version of fundamentalist Islamism at the expense of political forces which have not used such rhetoric.

The Islah party

Islah was established in 1990 under the leadership of Shaikh Abdullah bin Hussein al Ahmar, the leader of the Hashed confederation. Its membership is formed of Islamists throughout the country and of tribespeople in the far north of the country. It was in alliance with Saleh’s General People’s Congress (GPC) until 1997. The party’s ideology is Islamist, including positions associated with the Muslim Brotherhood, despite the fact that its northern members are followers of Zaydi rites. To increase support, Islah used the ‘Scientific Institutes’, which were educational establishments that competed with state schools until 2001, when they were integrated in the Ministry of Education’s structures. As compensation for their closure, the Saleh regime strengthened the religious component of the state syllabus.

In the past two decades, Islah suffered from the rivalry of more extreme Sunni Salafi movements, in particular followers of the Dar al Hadith, established by scholar al Wadi’i in Saada in the early 1980s. Its prominence increased as other branches were opened in different parts of the country after his death in 2001. This has been particularly important in recent years, as the UAE has supported and sponsored more extreme Salafis to rival Islah and reduce its influence, in addition to sponsoring direct attacks on Islahis, particularly in and around Aden.

In recent years Islah’s relationship with Riyadh has deteriorated, and it has remained under pressure from the UAE’s virulent opposition to its presence in government (which the STC also opposes). Despite this, in terms of popular support, Islah remains probably the most effective and best organised political party throughout the country. This is partly due to the fact that, unlike the GPC, it has a distinct ideological and programmatic position. In this regard, the ambiguous attitude of the Saudi leadership is a further factor in the weakness of the PLC as, on the one hand, the Saudi regime supports the tribal element of Islah while, on the other, it opposes its Islamist element. As a result, the Saudis are not providing resolute support to the anti-STC factions within the PLC, despite the fact that Riyadh opposes separatism in Yemen.

Zaydism and the Houthis

The Houthis have actively transformed Zaydism, introducing, encouraging, and even imposing rituals and other markers imported from Iranian ‘twelver’ Shiism. Houthi efforts to differentiate their Zaydism from ‘traditional’ Zaydism have expanded exponentially since they took political control of the capital and the most populated areas of the country in 2014-15. This is connected to the prosecution of the war: changes to school syllabi and the introduction of educational ‘summer camps,’ ostensibly for religious educational purposes, are the main mechanism used by the Houthis to recruit volunteers for their armed forces, including many aged under 18.

With respect to Zaydism, the traditional religious authorities based in Sana’a have different interpretations of its main prescriptions from those of Ansar Allah. But their position has been weakening over the years, particularly following the assassination of some prominent Zaydi personalities during the National Dialogue Conference period in 2013-14. These differences between traditional Zaydism and Iran-influenced Houthis are potentially important ideological challenges to the current Houthi leadership.

The deepening of these sectarian and regional divisions weakens national cohesion and thereby represents a fundamental threat to the future of Yemen as a unified and effective state. The re-establishment of peace requires the commitment and support of the population at large for a shared vision of the Yemeni nation. Combined with reduced intra-country contact due to the war and hostile propaganda among rival political factions, the divisions discussed above harden perceptions of difference and mutual suspicion, facilitating the recruitment of soldiers and increasing antagonism between the different groups within the country. This enables the leaders of the rival factions to ensure the populations under their control are, at least, acquiescent when it comes to the war, even if they are not enthusiastically supportive. These dynamics have been heavily reinforced by the war economy that has emerged over the past decade, which worsens fragmentation and increasingly acts as an incentive to continue conflict rather than pursue peace.

Economic problems

The Yemeni economy is in freefall. Since the war started, GDP has shrunk by more than 50 per cent and by 2021 its per capita GDP had dropped from a pre-war level of $1,600 to $630.[1] However debatable the quality of this indicator, it demonstrates a dramatic deterioration of living standards for the population. Reduced funding by contributing states to the UN Humanitarian Response Plan, one of the largest in the world, is now worsening living conditions for the population at a time when jobs are scarce, incomes low, and prices rising dramatically. Without progress on the economy, improving basic living conditions for people on the ground, and curtailing the space for the profiteers who prosper from the continuation of the war economy, there will be little to no chance of establishing meaningful peace.

The economic war

Alongside the military conflict, an economic war is taking place between the IRG and the Houthis, in two sectors primarily. The first is financial: there are now two separate and rival central banks, a situation that has led to widely differing exchange rates. This deeply impacts on citizens’ lives, especially with respect to the cost of imported basic staples, a particularly relevant factor in a country which imports the vast majority of its staples. The second is the Saudi-led coalition’s blockade of the Red Sea ports, which affects the import of food and fuel for the more than two-thirds of the population living under Houthi rule. European and other international efforts to address these problems have so far amounted to little. A longer-term political and economic development process must be part of addressing these issues.

The financial conflict

The IRG has been more effective on the financial front than in its military campaigns – although this relative success has had negative consequences for the population residing in its area. In September 2016, the IRG formally ‘transferred’ the headquarters of the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) from Sana’a to Aden, hoping this would paralyse Houthi finances. Although the move has made financial transactions more difficult for them, the Houthis financial structure has not collapsed. The Sana’a central bank has retained control over the operations of the country’s main businesses and banks, which have their headquarters in the city and are therefore compelled to comply with Houthi demands. This is despite the fact that the Aden central bank controls access to the SWIFT system and the country’s relationship with the IMF and World Bank.

The IRG’s response to the loss of income since the war began, mainly because of reduced hydrocarbon exports, has been to print billions of Yemeni riyals. Two currencies are now effectively in circulation. The fact that the new notes are different from the old ones has enabled the Houthis to make their use illegal in the area under its control, a prohibition they have strictly enforced since December 2019. As a result, the rate of depreciation of the riyal has diverged considerably between the two areas. It dropped to $1 = YR 600 early on in the Houthi-controlled areas, where it has remained relatively steady. In IRG territory, depreciation has been rapid, dramatic, and volatile, fluctuating according to the expectation of financial support from the partners in the coalition, mainly Saudi Arabia. It sank to $1 = YR 1,700 at its worst; since the establishment of the PLC, it has hovered around $1 = YR 1,100. This has forced up the basic cost of living for people in IRG-controlled areas. The greatest impact is on the majority of people who have no access to hard currency from remittances (mostly from Saudi Arabia in Saudi riyals) or relatives paid in US dollars working for the international organisations present in the country.

The issue of salaries for the 1.2 million people who make up the government staff in Yemen has been at the forefront of the struggle for control of the CBY. Since September 2016, they have been paid intermittently, which has harmed the household incomes of up to 7 million people. The Houthis have sought to increase their income through increased customs duties and other fees, including those paid into the Hodeida branch of the central bank. The demand by the Houthis that their military and security staff be included in the list of beneficiaries of income from oil revenues was the final nail in the coffin of the renewal of the truce in October 2022; unsurprisingly, this was unacceptable for the IRG and its supporters. The ending of the truce was promptly followed by the Houthis threatening to attack ships exporting oil from Yemen, leading to a series of ‘warning’ attacks on ships intending to load from the southern oil export ports. Oil companies have stopped operating in Yemen as a result – meaning the Houthis achieved the aim of their attacks. Meanwhile, there is no resolution in sight to ensure regular payment of government staff, nor to end the problem of competing currencies and wider impacts on the cost of survival for ordinary Yemenis.

The blockade

The Saudi blockade of Hodeida and other Red Sea ports is the second main element of the economic struggle between the two formal sides of the war. The Saudi-led coalition established the blockade at the beginning of the conflict, officially claiming its purpose was to prevent the Houthis receiving weapons and support from Iran. In practice, it has been an arm of the economic struggle, with coalition and IRG actions preventing the docking of fuel and food shipments at Hodeida, even once cleared by the UN Verification and Inspection Mechanism for Yemen (UNVIM). Their aim was to increase shortages within Houthi territory in the hope of encouraging domestic dissent and concessions to the IRG.

The variation in shipments allowed to enter Hodeida largely reflects the ups and downs of the war: average monthly deliveries of fuel ranged from 140,000 tonnes in 2016, climbing to a high of 188,000 in 2019, before then dropping to a low of 45,000 tonnes in 2021. The significant increase in deliveries discussed by UN special envoy Hans Grundberg in his October 2022 briefing to the UN Security Council was a major achievement of the six-month truce, during which time, he reported: “over 1.4 million metric tonnes of fuel product [were] delivered to Hudaydah ports, more than three times the amount of fuel products entering in 2021” – equivalent to about four months’ need for the Houthi-controlled area.

War profiteers

War profiteers in Yemen include IRG military leaders who list ‘ghost soldiers’ on their payrolls. Others are fuel traders in both IRG and Houthi territory who use the constraints of the blockade to their advantage, in the latter case operating under Ansar Allah control. They make their money from the various impositions on commercial and humanitarian imports. In Houthi-controlled areas, an additional source of profits comes from coalition limitations on the docking of fuel ships at Red Sea ports, leading to shortages which enable Houthi-supported traders to increase prices at the pump.

The war economy also includes a growing network of checkpoints throughout the country that enable local power holders to raise funds. In some cases, this income is used to make up for unpaid government salaries, but the main impact has been – in addition to reinforcing fragmentation – to push up the prices of basic necessities for Yemen’s increasingly destitute population. The checkpoints meanthat goods travel along ever-longer, diverted routes, which increases fuel costs and their ultimate price – while also further encouraging the creation of additional checkpoints. Despite improvements in the arrival of fuel while the truce was in place, the situation is still problematic. Discriminatory behaviour by those who man checkpoints is an additional problem for citizens needing to travel. The entrenchment of a war economy with its innumerable new local beneficiaries will prove an additional obstacle to the creation of a viable peace process that brings all relevant parties together.

Fundamental problems of the economy

The economic consequences of the conflict for ordinary people are stark. The vast majority of Yemenis have experienced a massive deterioration in their living conditions. This is most visible in the cost of the minimum survival basket, which has risen by more than 150 per cent since 2015 when the war started.[2] Meanwhile, incomes have plummeted. During 2022, the situation worsened as a result of a number of factors: the drop in contributions to the UN’s Humanitarian Response Plan, which as of 2 December stood at 55 per cent of requirement, with a dramatic fall in contributions from Saudi Arabia (which has funded nearly 10 per cent of the overall amount) and the UAE (nearly 1 per cent of the overall amount). This has left the United States and European states as the main financers. The war in Ukraine has increased the cost of wheat imports and fuel. The six-month truce did too little to alleviate the humanitarian situation, meaning millions of Yemenis have remained more focused on their immediate economic and survival problems, putting the peace process on the back burner of their concerns.

Most Yemenis receive their meagre income from either government salaries, the rural economy (where about 70 per cent of the country’s population reside), or small-scale industrial and commercial activities. In 2014, before the fighting started, the poverty rate stood at 49 per cent. The income people make through agriculture has diminished because of a combination of factors including fighting, the worsening impact of climate change, increased cost and supply constraints for inputs, and insufficient water and fuel supplies. Moreover, decreased local purchasing power has resulted in decreased local demand.

Indeed, Yemen’s fundamental problems include the issue of limited natural resources and, in particular, water scarcity, which affects society and the economy and threatens the very existence of Yemen as a habitable country. Yemenis have been using one-third more water annually than is replenished: 3.5 billion cubic metres used and 2.1 billion cubic metres replenished.[3] As supplies are exhausted, forced migration out of some areas has already taken place, causing additional pressure on all resources in the places people leave for; the best-known cases are Baydha and Taiz governorates. About 90 per cent of Yemen’s water is used in agriculture and much of the water drawn from fossil aquifers has been used in irrigated agriculture producing export-orientated crops. This follows inappropriate development policies promoted by dominant world agencies, which both impoverished small holders and worsened the overall economic situation.

Hydrocarbons are also limited: prior to the war, average oil production was in the range of 150,000-200,000 barrels a day. This dropped to about 55,000 barrels a day by 2021, which represented a slight increase on 2020 but is far from sufficient to solve the government’s budget constraints. Even Yemen’s income from gas exploitation, which only started in 2009, was interrupted in March 2015 when Yemen LNG, the only natural gas liquefaction project in the country, ceased operations due to force majeure. When re-established, gas exports are unlikely to be sufficient to finance the country’s budgetary needs, even if the price agreement with the foreign shareholders of Yemen LNG is improved and the funds are used with maximum efficiency for the benefit of the population as a whole.

A sustainable peace requires significant changes in the basic living conditions of the population. In the medium and long term, to ensure peace Yemen needs a renewed focus supporting socio-economic development, including help to bring the war economy to an end. People benefiting from reasonable living standards and access to basic services will be more committed to avoiding conflict. Tangible progress on the economic front is an area where Europeans could offer meaningful support. All Yemenis would welcome this.

What Europe can do

A resolution to the conflict in Yemen ought to be a priority for European states. The importance – in both directions – of relations between European states and GCC states has increased in the wake of Russia’s war in Ukraine and volatile energy prices. This context offers an opportunity to prioritise the resolution of the Yemen crisis. The failure to renew the truce gives additional urgency to addressing the country’s long-term structural problems.

Yemen is important for Europe in its own right: its strategic position controlling the Bab al Mandab and, consequently, access to the Suez Canal, presents a potential security threat to this crucial world maritime route. With a population of more than 30 million people, Yemen is an important potential economic partner for European states. And the grave humanitarian crisis in Yemen which, until recently, was systematically described as ‘the worst in the world,’ also ought to encourage Europeans to put into practice their claim to uphold universal humanitarian values, in places such as Yemen as well as in Ukraine.

European states and the EU together possess assets that should enable them to engage more profoundly in Yemen. One of these is the multi-dimensional tool box they can collectively access, which includes political dialogue, humanitarian support, and development investment. Another asset is the fact that the EU, its institutions, its member states, and other European states are able to operate either separately or in synergy. This multiplies options and types of involvement, ranging from diplomatic interventions to social and economic support. A third asset is the values-based approach which, although not universal, given the role of some European states in the arms trade, presents a more sympathetic image to most Yemenis, including the Houthis. These strengths mean that Europeans can, and should, play a more active role in helping bring the Yemen conflict to a conclusion. They can do so through the following measures.

Increase diplomatic engagement with all parties

The immediate political priority for Europeans is to restore dialogue between the Yemeni parties and prevent the resumption of full-scale fighting. Despite the clear challenges, the fact that the recent truce held for six months points to the possibility of a further cessation of violence. European states should therefore now urgently press all parties – including those within Yemen as well as neighbouring states – to recommit to an extended UN-brokered agreement. The EU, its member states, and other European states can all engage in high-level inter- and intra-state discussions in ways not available to the UN special envoy, whose mandate restricts him from doing so.

GCC states

Europeans may be able to put some pressure on Saudi Arabia and the UAE to desist from supporting particular factions within the country, thus allowing a genuinely intra-Yemeni process to proceed without external interference. As noted, both Saudi Arabia and the UAE are now concerned with ending their direct military activity in Yemen, and probably also want to reduce their political and financial involvement. Therefore, in outreach with GCC states, European states should encourage them to press the IRG to recommit to the truce and to accept the necessity of mutual compromises. The soon-to-be-appointed EU special representative to the Gulf can engage with these states to encourage long-term policies focused on the advantages of a regional security and economic architecture that includes an effective Yemeni state. To address the massive discrepancy in wealth between the GCC and Yemen, Europeans should also recommend that GCC states pursue closer relations with Yemen, with an emphasis on facilitating economic cooperation, including Yemeni labour migration to GCC states.

Similarly, Europeans can, in their frequent discussions with the GCC states and PLC members, encourage them to make the PLC what it was intended, namely a united front against the Houthis working towards the re-establishment of a functioning state in Yemen. For this to succeed, Saudi Arabia and the UAE need to make a commitment to promoting a united Yemeni state as well as to providing financial support for humanitarian and development needs. Without the long-overdue emergence of a credible alternative, it is hard to see the Houthis making compromises, however much pressure they are put under.

The Houthis and the IRG

Europeans also need to increase their engagement with the Houthis, who should not be allowed to duck responsibility for ending the truce and wider conflict by persisting with their maximalist demands, which include requests for millions of dollars in compensation as well as the demand for security personnel to be paid from oil revenues. The sense of isolation that Houthis feel contributes to their obduracy, as they believe the international community dedicates insufficient attention to their positions. Saudi Arabia already engages with the Houthis and within Yemen only the IRG opposes such dialogue. The EU might be particularly well suited to assume dialogue with the Houthis, and it should attempt to diversify contact away from the hard-line Houthi voices that dominate international engagement. European politicians involved with Yemen must include this topic in their negotiations with the IRG, making it understand that engagement does not mean legitimisation.

Iran

While Iranian influence over the Houthis is often overstated, it is a reality. Despite the likely collapse of the nuclear deal, and the curtailing of diplomatic engagement following the brutal crackdown on the women-led protest movement in Iran, as they engage with Iran Europeans should nonetheless make a concerted effort to protect Yemen from emerging as a theatre for renewed regional escalation. Tehran is seeking legitimisation of both its own role and that of the Houthis in Yemen, a step which has partly been secured through a bilateral Saudi-Iranian dialogue over the past years. Europeans should work to ensure that this dialogue does not collapse even if European disengagement with Iran takes place. The new European special representative to the Gulf should still be allowed to build a dialogue on Yemen.

If these steps help bring about a renewed truce, Europeans can then adopt a number of policies to try to secure it and make further gains. These could include: assistance to turn the military coordination meetings, which took place during the truce, into a lasting committee by providing its membership with technical support; ensuring regular and lasting funding for UNVIM, given its critical role in facilitating the increased delivery of fuel, food, and other essentials from the Red Sea ports; and rapidly implementing the rehabilitation of Sana’a airport to encourage Houthi cooperation, and to give confidence to the population for whom this is the main airport.

Focus on reducing state fragmentation

The most difficult issue to address is that of political and social fragmentation. As this paper has set out, this exists in a multiplicity of forms throughout the country. Yemenis themselves must lead efforts to close the fractures in their society. Nevertheless, Europeans can still support constructive progress on this issue. For example, they could facilitate intra-Yemeni dialogues over the future of the Yemeni state. In 2022, Sweden hosted the first Yemen International Forum, which gathered together representatives from across the country, and the Netherlands will host a follow-up meeting in 2023. This could be a useful venue for such discussions.

Fragmentation must also be addressed through media outreach and other cultural activities that reassert the characteristics shared by all Yemenis. Europeans can provide financial support for these activities, which can take place without undermining or suppressing regional and local cultural differences; indeed, these illustrate the diversity and wealth of Yemeni culture.

Finally, reducing, or even eliminating, checkpoints, and facilitating renewed interaction between Yemenis from all parts of the country, is important to help tie the country together again. This will allow Yemenis to experience greater cohesion, and thus actively combat the daily perception of discrimination that has become entrenched over the past decade. In view of the considerable exactions on the transport of goods at checkpoints, their reduction would have a significant impact on reducing prices and thus reducing economic constraints on the population.

Widen economic support

Perhaps the biggest direct difference Europeans can make to Yemen’s future is to provide economic support to address the structural factors that create division, conflict, and instability. There must be a focus on immediate humanitarian needs but this should not take place at the expense of medium- and long-term support to improve the economy. Economic deterioration is a consequence of, and an exacerbating factor in, the conflict, meaning that economic measures are essential to bring about a lasting peace. Improvements in livelihoods would contribute to creating a space to strengthen the peace-making process.

Although the $2 billion promised by the UAE and the Saudis to support the CBY are in the process of being partially transferred, the bank still needs additional technical support to enable it to operate at improved operational standards. This is a long-standing demand from the IMF as well as the funding states. Here Europeans can help by providing training needed by its middle and higher management levels.

Regardless of the renewal of the truce, Europeans should also consider how they can lead a surge of development support to advance sustainable peace on the ground. But while some European states have a good record in the development sector, the EU is constrained by two factors: its current three-year development project cycle is too short to implement significant initiatives and it is weighed down by complex bureaucracy. The EU should revise both to extend the first and reduce the second.

Specifically, a number of critical sectors deserve attention.

Infrastructure renewal

Physical infrastructure reconstruction in Yemen is essential and Europeans can continue to work with international funding agencies such as the World Bank to increase this assistance. Short-term immediate repairs of roads and bridges damaged by fighting or floods have taken place and should be expanded. Initiatives led by local communities in this respect are a promising approach deserving of support.

Water management and the agricultural sector

Europeans, particularly the Netherlands and Germany, have had a long involvement in Yemen’s water sector. They should help Yemenis introduce a more sustainable approach to water management, prioritising domestic use. This would involve limiting the use of irrigation in agriculture, as well as taking a differentiated regional approach according to the varying ground and surface water resources. European states can help develop high-value, rain-fed cash crops, and high-yielding, fast-maturing, and drought-resistant staple crops suitable for Yemen’s changing climate. This would be an essential element to retain agriculture as an important component of rural living conditions.

Education

Yemen has the advantage of a very young population, but its youth are let down by a very weak education structure. Not only does the country have a high illiteracy level, which is likely still about 45 per cent, but the overwhelming majority of the 400,000 annual new entrants on the labour market have inappropriate and low-quality skills. Education is, in the long run, the most important sector to enable the growing Yemeni population (which is expected to reach 50 million by the middle of the century) to achieve reasonable livelihoods. Moreover, Yemen’s education system needs fundamental transformation, not simply expansion: Europeans need to place greater focus on providing the necessary technical advice, training, and financing to build an education system responsive to the needs of the coming decades.

Health care

The war has caused considerable physical damage to the country’s medical sector, both with respect to its infrastructure and staffing. Reconstruction of medical facilities is essential, as is retraining staff who have often given up working in the absence of salaries. There should be an appropriate balance between the provision of basic health care in community-level facilities, particularly in remote rural areas, and specialised facilities in urban areas. The international community has made major efforts in recent years to support preventative care and deal with outbreaks of disease and other major problems. Previous EU experience provides important lessons, such as mechanisms to prioritise delivering services in a decentralised way.

Europeans should work to ensure most development investments take place at grassroots level with local organisations, ranging from community-level civil society organisations, or groupings of such organisations to facilitate management and monitoring. Their role and importance have grown enormously during the war. Community leaders would be able to mobilise the most effective such organisations into larger coalitions or groups at whichever level seems most appropriate culturally and politically, according to combined criteria of social cohesion and existing administrative structures. This might range from districts to governorates or even the regions suggested in the 2015 draft constitution. Some issues such as water management, education, and agricultural research need to be designed and planned nationally, but with enough flexibility built in to allow the most suitable form of implementation on the ground.

Prioritise human rights and the rule of law

Europeans should not neglect issues of human rights, justice, and the rule of law, as they are vital elements in addressing the widespread frustration and anger caused by the impunity of perpetrators of abuse at all levels. Despite the best efforts of many European states, under pressure from GCC states, the UN’s Human Rights Council ended the work of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts in 2021. This left Yemen and its citizens without any internationally recognised independent monitoring of human rights abuses. Monitoring and information gathering are prerequisites to the search for justice. To fill this gap, the EU could establish its own Yemen monitoring committee. Such an initiative would confirm European commitment to the universal values it claims to uphold and ensure some degree of ongoing accountability needed to sustain a longer-term peace process.

Europeans could also work to ensure that the formal, intra-Yemeni political dialogue – if and when it begins – includes women and human rights, and transitional justice organisations. This is necessary to ensure wide representation in a political agreement, and would demonstrate European commitment to values-based politics. Here Europeans should also look to expand funding, training, and capacity support to civil society organisations, which play a meaningful – and under-appreciated – role at the local level, including in preventing violence. Groups such as the ‘Mothers of Abductees’ have succeeded in quietly securing the release of thousands of prisoners; they deserve more international support. The EU should specifically assist civil society groups to develop accountability mechanisms and expand locally owned training on humanitarian law, law enforcement, anti-money laundering, monitoring, and other security-related activities relevant to organisations engaged with armed actors.

Conclusion

The EU and European states can and should play a major role in helping bring the conflict in Yemen to an end. Indeed, 2023 provides a moment of opportunity for increased European involvement to address Yemen’s problems. Sweden will hold the presidency of the EU for the first half of the year; as a state, it has been increasingly and deeply committed to Yemen for many years, most prominently since the 2018 Stockholm agreement. Switzerland will join the UN Security Council, thus adding another committed voice. The United Kingdom remains the pen holder for Yemen at the UN Security Council.

All processes, whether political, social, or economic, must be led by Yemenis. But European actors have a unique role to play in encouraging the external states most closely involved in the crisis – namely, Saudi Arabia and the UAE – to change their approach. Europeans should seek to persuade Riyadh and Abu Dhabi to desist from attempting to influence political outcomes in Yemen, and to provide financial and diplomatic support to help Yemenis return their state to viability. Bringing Yemen closer to the GCC economically will assist in this.

Europeans and others can also contribute by providing mediation, information, technical knowledge, experience, and financial support. This should include far greater focus on the provision of basic services across Yemen, from education to water and energy supplies: the failures of these sectors are fundamental causes of Yemen’s long conflict. Any sustainable pathway out of the war will depend on a strategy that places as much, if not more, focus on addressing these long-term development issues as it does on reaching elite-level agreements.

About the author

Helen Lackner is a visiting fellow at the European Council for Foreign Relations. She has been involved with Yemen for five decades. She is the author of Yemen, Poverty and Conflict (Routledge) and the second edition of her Yemen in Crisis: Devastating Conflict, Fragile Hope (Saqi) will be published in early 2023. She is a regular contributor to Orient XXI, Open Democracy, Arab Digest, and Oxford Analytica, among other outlets. She has spoken on the Yemeni crisis in many public forums, including in the UK House of Commons.

[1] Helen Lackner, Yemen, Poverty, and Conflict, Routledge, 2023, p104.

[2] World Bank Country Engagement Note, (2022) p 31.

[3] Helen Lackner, Yemen, Poverty, and Conflict , Routledge, 2023, p 77.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.